Abstract

The world’s largest diversion-type hydropower system will be created on the Yarlung-Tsangpo Grand Canyon. The canyon, a critical region for hydropower development and ecological conservation, faces challenges under climate change. Here we evaluate the water-energy-ecosystem nexus in this hydropower system using the Water and Energy Transfer Processes in Large River Basins model and the Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm III model. Key findings reveal that reservoir operations with medium replenishment flow (1000 m³ s−1) during dry periods achieve an optimal balance among hydropower generation annually (2231 × 108 kWh), flood mitigation (peak clipping rate 22.8%), and minimal ecosystem impact (eco-index 0.45). Hydropower development stabilizes runoff regimes, enhances flood control capacity under climate scenarios (e.g., 29.2% peak reduction under Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 126), and mitigates downstream flood risks while supporting dry-season irrigation and navigation. Notably, under low-forcing climate change scenarios (Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 126), ecosystem stability is sustained primarily through the gradual and consistent replenishment of water resources from stabilized snowpack and glacial reserves. Transboundary cooperation is strengthened through adaptive reservoir management, ensuring energy security for China and flood protection for downstream nations. This integrated approach highlights the potential for harmonizing sustainable hydropower expansion with ecological and geopolitical resilience in international river basins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydropower is widely recognised as a clean energy source and plays a significant role in China’s energy landscape1,2,3,4. As of 2020, China’s remaining hydropower potential stands at 350 million kW5, with much of the development concentrated along the edges of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, notably in the Yarlung-Tsangpo (YT) River region. China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) includes significant hydropower development in the YT River6, aiming to create the world’s largest diversion-type hydropower system, and this project was officially approved in December 2024. However, this area is known for its delicate ecological balance, active geological and tectonic dynamics, and frequent natural disasters7,8,9,10, presenting both opportunities and challenges for hydropower expansion. Therefore, strategic planning for water infrastructure operations in the YT River Basin, including reservoir replenishment, becomes crucial for managing hydrological variability, enhancing resilience against risks, and ensuring water security.

Climate change, as a significant global geoscience issue, is a matter of great concern to scientists, engineers, and decision-makers. The YT River Basin is also experiencing profound influences from climate change. Studies have demonstrated that under future climate scenarios, temperatures will rise, precipitation will increase, snowmelt and ice melt will intensify, flood flows will increase, and flooding will become more frequent11,12,13,14. In light of the prolonged necessity for hydraulic construction in the YT Grand Canyon, it is imperative to assess the capacity of terraced hydraulic projects to respond to future climate change. Therefore, it is essential to quantify the impacts of hydraulic projects on Hydropower production, flood control performance, and ecosystem impacts in the YT River Basin under multiple climate-forcing scenarios.

The water-energy-ecosystem (WEE) nexus explores the interplay among hydropower, flood mitigation, and river ecosystems within the context of hydropower development15,16,17. A comprehensive understanding of the WEE nexus alongside a large-scale cascade hydropower system is essential in the YT Grand Canyon’s fragile ecology and dynamic geological settings. This understanding can reveal the “ecological constraints” and “geo-disaster constraints” that affect hydropower development, offering scientific insights for managing water resources on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau.

Various studies have investigated the impacts of reservoir operations on ecological goals18,19,20. In these studies, integrating ecological considerations with Integrated Habitat Assessment (IHA) parameters is widely utilized. The eco-index (EI), derived from IHA metrics, quantifies the extent of natural flow restoration and represents the distinctive features of runoff processes21,22. This index serves as a metric for assessing the response of the aquatic ecosystem in the YT Grand Canyon19.

Hydropower development plays a crucial role in flood control and mitigating river downcutting23. The river system in the YT Grand Canyon is a high-altitude, deep-valley river subject to substantial undercutting, geological activity, and disaster risks24. Fortunately, hydropower projects can efficiently convert water energy into electricity, while the dam’s energy-dissipation mechanisms effectively handle excess energy during floods. Additionally, upstream reservoirs’ water storage and sedimentation can raise erosional thresholds and reduce potential landslide energy along the mountain slopes25. Therefore, assessing the flood control capacity of cascade reservoirs remains paramount.

The study aims to investigate the WEE nexus within a large-scale cascade hydropower system under climate change in the YT Grand Canyon. It does so by simulating reservoir operations, examining hydropower generation, analysing hydrological changes, assessing aquatic ecosystem responses, and studying flood mitigation. This research is guided by three primary objectives: (1) identifying alterations in runoff volumes and processes caused by the large-scale cascade hydropower system, (2) establishing criteria for reservoir replenishment during non-flood seasons following the evaluation of trade-offs within the WEE nexus, and (3) elucidating the WEE nexus specifically for the hydropower system under climate change in the YT River Basin. The quantitative analysis of WEE nexus outcomes and the optimised reservoir operations in this international transboundary river hold promise for offering fresh perspectives and fostering opportunities for multilateral cooperation.

Study Area

Yarlung Tsangpo River Basin and Grand Canyon

The Yarlung Tsangpo-Brahmaputra River traverses China, India, and Bangladesh, with the Grand Canyon situated in China’s southeastern Himalayan region. The primary stretch earmarked for hydropower development spans from Milin to Pasighat (ML-BXK), covering approximately 623 km in length, with elevations ranging from 3076 m to 155 m. It has a natural headfall of 2921 m and an average riverbed aspect ratio of 3.85‰, within the drainage area of approximately 80,000 km2 (Fig. 1d).

The ML-BXK basin exhibits minimal inter-annual runoff variability but displays highly uneven intra-annual distribution, with 79.3% of the annual normal runoff occurring during the flood period (June-October) at Nuxia. Given its vast size and elongated shape, the flooding dynamics within the ML-BXK basin unfold gradually, spanning 23 to 68 days on average, characterised by gentle rise and fall rates, modest flood peaks, and substantial flood volumes.

As of January 2024, four run-of-the-river hydropower plants (P4, P5, P6, P7) with small storage capacity operating as daily regulating reservoirs have been established along the YT River and Niyang (Ny) River’s middle and lower reaches (Fig. 1b). These reservoirs exert negligible impact on the study area.

Cascade hydropower system with reservoir storage

The major hydraulic installations within the ML-BXK basin comprise “3 reservoirs and several hydroelectric power stations”, as depicted in Fig. 1c26. The first reservoir functions as a regulating reservoir with an annual capacity, enabling downstream runoff regulation of the Yarlung Tsangpo River and exerting a significant regulatory impact on the cascade hydropower system. The second reservoir serves as the counter-regulation reservoir for the first reservoir and acts as the primary intake reservoir for diversion-type power plants. The third reservoir functions as the ultimate counter-regulation reservoir, ensuring runoff process stability during reservoir storage periods.

Post-hydropower development, the runoff pattern in the ML-BXK basin undergoes categorisation into three segments due to distinctive alterations in total runoff volume and processes (Fig. 1c): (1) Replenishment regime (RepR) spans from the first reservoir to the second reservoir, influenced by the storage and replenishment of the first reservoir. (2) Reduction regime (RR) encompasses the stretch from the second reservoir, influenced by water transfers. The RR further divides into upstream (RRU) and downstream (RRD) sections, with RRU situated immediately below the dam and RRD preceding the water transfer's return point. (3) Back regime (BR) serving as the segment that redirects water back to the natural river.

Results

Hydrological Model Calibration and Validation

The WEP-L distributed hydrological model for the Yarlung Tsangpo River basin effectively replicates the river’s total volume and runoff dynamics. Figure 2a and Table S1 illustrate the accurate simulation of natural water inflow processes at downstream hydrological stations (Yangcun, Nuxia, and Dexing) from 1985 to 2019, evaluated monthly. The Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient (NSE) for these stations consistently exceeded 0.7 in validation, with Percent Bias (PBIAS) values remaining under 5%. Notably, the model maintains high accuracy even after downscaling. Daily hydrological series simulations at Nuxia (2003-2019) and Dexing also exhibit NSE surpassing 0.7 and PBIAS values below 5% when compared against observed data (Fig. 2a and Table S1). In addition to discharge, the snow cover fraction obtained from the WEP-L model was validated using observed snow cover data, in which the Correlation Coefficient (CC) is 0.84 and Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) is 9.12% (Fig. 2b), and the glacier mass balance was validated using observed and reconstructed data from the Parlung NO.94 Glacier in which the CC is 0.67 and PBIAS is -14.2% (Fig. 2c). The validations of the other two glaciers, which reported good simulation results (CC = 0.95;0.97), are presented in Figure S1. Figure S2 shows the average temperatures in the YT river basin projected by the five global climate models (GCMs) under the shared socio-economic pathway (SSP) 126 and SSP585 scenarios. The high forcing scenario increases temperatures by approximately 5 °C over 70 years. In contrast, the low forcing scenario maintains the status quo with a non-significant temperature increase.

a Calibration and validation of the discharge from the model. The first three figures show the simulated and observed monthly discharge at Yangcun, Nuxia, and Dexing stations. The pink solid lines represent the simulation, and the blue solid lines represent the observation. The last two figures show the daily discharge at the Nuxia and the Dexing. The pink solid lines represent the simulation, while the blue dots show the observation. b Calibration and validation of the snow cover from the model. The simulated (pink solid lines) and observed (blue dots) daily data for the fraction of the snow cover in the YT river basin (proportion from 0 to 100%). c Validation of the glacier mass balance from the model. The simulated (pink-dotted dot solid lines), reconstructed (yellow squares) and observed (blue dots) annual data for the glacier mass balance in the PARLUNG NO.94 Glacier.

The WEE Nexus and runoff seasonality under Reservoir Replenishment

Considering the three objectives in a balanced manner, the study identifies the relatively favourable trade-offs within the WEE relationship when recharging the river with the medium flow (1000 m3 s−1) during the dry period (refer to Fig. 3a and Table S2). The mean values indicate a hydropower production of 2231 × 108 kWh, an EI of 0.45 for the entire river, and an Fp of 22.8%. Figure 3a, c illustrate that the hydropower production capacity continued to increase slightly from 2213 to 2263 × 108 kWh as the replenishment flow rates increased, while the flood control capacity first increased and then decreased, peaking at the replenishment discharge of 1200 m3 s−1 (Fp1200 = 24.2%). At the same time, disturbances to aquatic ecosystems continue to rise from 0.36 to 0.59. Note that the data described above are in the middle of the Pareto boundaries for the different reservoir replenishment flows.

a Three-dimensional Pareto-seeking optimal distributions of WEE nexus (HP/EI/Fp) for the ML-BXK river basin at the replenishment discharges from 600 to 1400 m3 s-1. Arrows are merit-seeking orientations, except the red arrow. b Three-dimensional Pareto-seeking optimal distribution at the discharge of 1000 m3 s-1. Figure (b1) plots the Pareto-optimal distributions and boundaries of the EI and Fp indices. Figure (b2) shows the distributions and boundaries of EI and HP indices. Figure (b3) represents the relationship between the Fp and HP indices. Note that the icons in the lower right corner of the 2D figures show the positions in the 3D figure. c Interannual variances of HP, EI, and Fp indices (each point represents a value of one year) in the ML-BXK river basin. The left figure represents the multi-year HP values at the discharges from 600 to 1400 m3 s-1. The middle figure shows the multi-year EI values in four runoff segments (RepR, RRU, RRD and BR) at the discharge of 1000 m3 s-1. The right figure explores the multi-year Fp values in the runoff segments at 1000 m3 s-1. Note that the selected points are in the middle of the Pareto bounds of the different reservoir replenishment flows, where all three indices are better. Error bars represent the 5%-95% range. d Distribution of multi-year EI (above) and Fp (below) values in the RepR, RRU, RRD and BR at the discharge from 600 to 1400 m3 s-1. Note that the selected points are in the middle of the Pareto bounds. The asterisks indicate the significant difference between the data (p < 0.05). Error bars represent the 5–95% range. e The monthly inflow hydrographs in the runoff segments (RepR, RRU, RRD and BR) at the replenishment discharge from 600 to 1400 m3 s-1 and natural conditions (grey lines).

To illustrate the Pareto-optimal distribution between the objectives, Fig. 3b shows the relationship between the three indices (HP, EI and Fp) under the 1000 m3 s−1 discharge replenishment. The ecosystem impact increases slowly with Fp and HP and then increases significantly after the critical thresholds (HP = 2231.38 × 108 kWh and Fp = 22.86%), as shown in Fig. 3b-1 and 3b-2. The flood control capacity decreases with increasing hydropower production capacity (Fig. 3b-3).

Significant variances were observed in the ecosystem impacts and flood control capacity among the RepR, RR, and BR at flow replenishment of 1000 m3 s−1 during the dry period (Fig. 3c). The ecosystem impact is highest in the RRU (EIRRU = 0.69) and lowest in the BR (EIBR = 0.27). Meanwhile, the disturbance is slightly higher in the RepR (EIRepR = 0.48) than in the RRD (EIRRD = 0.35), and its interannual variation is the most variable. The trend of flood control capacities followed the trend of ecosystem impacts, first increasing to a maximum in the RRU (FpRRU = 41.0%), followed by decreasing to a minimum in the BR (FpBR = 6.3%). However, the difference is that the flood control capacity in the RepR (FpRepR = 18.6%) is lower than in the RRD (FpRRD = 25.7%).

Varying flow replenishment affects ecosystem impacts and flood control capacities differently in the runoff segments (RepR, RR and BR). Specifically, significant alterations were observed in ecosystem impacts within the RepR and BR (p < 0.05, p < 0.05), along with significant changes in flood control capacities in the RepR (p < 0.05), as depicted in Fig. 3d. The data revealed that as supply flow increased from 600 to 1400 m3 s−1, the ecosystem impacts in the RepR continued to rise significantly from 0.36 to 0.59, with minimal fluctuation (first fall and then rise) in the RR area. Similarly, disturbances in the BR increase significantly from 0.10 to 0.48 (p < 0.05) with increasing the discharge, while the disturbances do not change much at replenishment flows of 800 and 1000 m3 s−1 (EI800 = 0.25, EI1000 = 0.27). Furthermore, the flood control capacities in the RepR initially increased (Fp600 = 16.2%), followed by a slight decrease (Fp1400 = 21.67%), with a significant jump (Fp1000 = 18.5%, Fp1200 = 21.70%) at the supply flow from 1000 up to 1200 m3 s−1. The flood control performance trend in the RRU slightly declined from 42.6% to 39.7%. However, flood control capacities in the RRD and BR were largely unaffected by supply flow, with the weakest values observed in the BR, fluctuating between 5.8% and 7.7%.

The inflow hydrographs in the RepR exhibit the more dramatic fluctuations during the dry period with varying supply flow, while the hydrograph under the medium replenishment flow (1000 m3 s−1) aligns closely with the natural process (refer to Fig. 3e). While low replenishment flow (600 and 800 m3 s−1) maintains consistent incoming water flow from April to May, flood peaks appear one month earlier than in the natural process. High replenishment flow significantly impacts inflow (1400 m3 s−1) from April to May, leading to a notable reduction, followed by an increase from November to the subsequent February. In the case of the RR, supply flow affects inflow from July to August, with higher supply flow leading to lower incoming flow slightly. Finally, an increase in replenishment flow correlates with increased inflow during the dry period from December to May in the BR. Moreover, inflow from April to May decreases as replenishment flow increases.

The WEE Nexus under Hydropower Development and Climate Change

Climate change and hydropower development profoundly changed the WEE relationship in the ML-BXK basin, especially in the late phase under the high forcing scenario (Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 558-Late phase: SSP558-LP), where EI and HP are significantly larger than others (Fig. 4a). Zooming into each runoff segment, ecosystem impacts in SSP558-LP are strongly expressed (p < 0.05), as depicted in Fig. 4c.

a Three-dimensional Pareto-seeking optimal distributions of WEE nexus (HP/EI/Fp) for the ML-BXK river basin at the replenishment discharges of 1000 m3 s-1 in the historical period (historical; 1985-2019), as well as the early phase (EP; 2029-2063) and the late phase (LP; 2065-2099) under two climate forcing scenarios (SSP126-low forcing scenario &SSP585-high forcing scenario). The ‘Historical’ indicates the optimal distributed values in the historical period. The ‘SSP126-EP’ indicates the optimal distributed values in the early phase under the low forcing scenario. The ‘SSP126-LP’ shows the values in the late phase under the low forcing scenario. The ‘SSP558-EP’ shows the values in the early phase under the high forcing scenario. The ‘SSP558-LP’ shows the values in the late phase under the high forcing scenario. Arrows are merit-seeking orientations, except the red arrow. b Each specific distribution from the Fig. 4a is amplified and displayed. Figure b1 shows the ‘SSP126-EP’. Figure b2 shows the ‘SSP126-LP’. Figure b3 shows the ‘SSP558-EP’. Figure b4 shows the ‘SSP558-LP’. c Distribution of multi-year EI (above) and Fp (below) values in the RepR, RRU, RRD, and BR in the historical period, as well as the early and late phases under the climate forcing scenarios. The red stars represent the average values of multi-year EI (above) and Fp (below), only influenced by climate change (Only CC: the simulation that exclusively considers climatic variations while disregarding the impacts of water infrastructure operations). Note that the selected points are in the middle of the Pareto bounds. The asterisks indicate the significant difference between the data (p < 0.05). Error bars represent the 5–95% range. d The multi-year HP values in the historical period, as well as the early and late phases under the climate forcing scenarios. Note that the selected points are in the middle of the Pareto bounds. The asterisks indicate the significant difference between the data (p < 0.05). Error bars represent the 5%-95% range. e The monthly inflow hydrographs in the runoff segments (RepR, RRU, RRD and BR) in the early phase and the late phase under two climate forcing scenarios, as well as the natural conditions in the historical period (grey lines).

Under four climate forcing scenarios (Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 126-Early phase(SSP126-EP); SSP558-EP; SSP126-LP; SSP558-LP) in Fig. 4a and Table S3, ecosystem impacts under SSP126 remain steady (EImean-EP = 0.50; EImean-LP = 0.50), while enhancing under SSP558 (EImean-EP = 0.53; EImean-LP = 1.06), compared with the values in the historical period all increased (EImean = 0.45). Meanwhile, the tendency of the HPs is like the EIs, flatting under SSP126 (HPmean-EP = 2406.2 × 108kWh; HPmean-LP = 2413.1 × 108kWh), and notably improving under SSP558 (HPmean-EP = 2502.3 × 108kWh; HPmean-LP = 2736.3 × 108kWh, p < 0.05), with lower values in the historical period (HPmean=2231.4 × 108kWh), as shown in Fig. 4d. Furthermore, the flood control capacities continually diminished in all climate scenarios (Fpmean126-EP = 29.18%; Fpmean126-LP = 22.26%; Fpmean558-EP = 13.53%; Fpmean558-LP = 11.00%), and only the value under SSP126-EP is higher than that in the historical period (Fpmean = 22.82%). The specific distributions of the climate scenarios from Fig. 4a are amplified and displayed in Fig. 4b, and the results are distributed in the Pareto fronts nicely.

The ecosystem impacts and flood control capacities exhibited variations across four runoff segments (RepR, RRU, RRD and BR), influenced by hydropower development and climate change as depicted in Fig. 4c. The BR demonstrated the least ecosystem impacts, whereas the RRU showcased the highest Fp. The RepR saw the most dramatic fluctuation, including Fps and EIs. In all runoff segments, the ecosystem impacts under the SSP558-LP were indisputably the most significant, with obviously higher than the values only considering climate change (EIOnly CC = 0.47). It is worth noting that flood control capacities saw a notable reduction in the RepR from 27.91% to -4.98%, and a slight decrease in the RR and BR. In comparison to Only CC conditions, there was a slight increase in ecosystem impacts in the upstream section (RepR and RRU), which remained relatively unchanged in RRD. Conversely, there was a minor decrease in ecosystem impacts in the BR. Flood control capacities are most enhanced in the RRU, with the weakest variations observed in the BR.

The monthly normal flow from three regimes (Fig. 4e) shows that Climate Change increases inflow during the flood period and Hydropower Development flattens the inflow hydrograph. The inflow rates under SSP558 from June to October surpass those under SSP126. The largest increase in inflow rates occurred in the BR. However, inflow rates under climate change have always been lower than those under natural conditions in the historical period during the flood period, except for the inflows under SSP558-LP.

Discussion

Influences of Hydropower Development and Climate Change

Hydropower production, flood control performance, and ecosystem impacts all displayed relatively favourable outcomes under medium flow (1000 m3 s−1) replenishment during the dry period for hydropower development based on Pareto optimisation.

The variations of shared socio-economic pathways have played an important role in changing the WEE relationship in the ML-BXK basin. The aquatic ecosystems operated relatively stably under SSP126, with a slight raised disturbance compared to the historical period. Additionally, hydropower generation remained consistent, and flood control capacities showed some weakness. The ecosystem shifted considerably under SSP558. Its disturbance increased significantly, and flood control capacities notably dropped in the late phase. Conversely, there was a remarkable improvement in hydropower generation.

From an ecological perspective, the superimposed effects of climate change and hydropower development do not result in more drastic ecosystem impacts, except under SSP558. The disturbance is maintained to some extent, and even slightly suppressed in BR, compared to under Only CC conditions. There is a certain critical threshold for the intervention of hydropower development, and the ecosystem impact increases exponentially under SSP558-LP. Additionally, the inflow hydrograph (Fig. 4e) illustrates that the inflow rises significantly during the flood period, and the inflows in BR under SSP558-LP are higher than the natural inflows in the historical period. It is also worth noting that the ecosystem impacts remain relatively stable over an extended period in the low-forcing scenario. This indicates that the long-term stability of the climate system (precipitation, temperature, and snow cover, as illustrated in Fig. 5a) plays a role in maintaining the stability of aquatic ecosystems27. As elucidated in the correlation heatmap (Fig. 5b), the ecosystem impact is shaped by a complex interplay between climate change and hydropower development, with no single factor emerging as a significant correlation. However, the ecosystem impacts were found to be negatively correlated with the precipitation factor and positively correlated with the temperature and snow cover, indicating that increased precipitation and restoration of the snow cover contribute to the optimal functioning of aquatic ecosystems28. A closer examination of the runoff segments (Fig. 5b) reveals that the ecosystem impact in the RRU is predominantly shaped by dam construction and replenishment flow (p < 0.05). However, other runoff segments are significantly influenced by precipitation, temperature, and snow cover due to climate change (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the disturbance intensifications in runoff segments beyond the RRU are profoundly affected by the discharge increase in the RepR. In contrast, the flow restoration in the RR positively impacts the aquatic ecosystem, implying that the glacial meltwater in the Grand Canyon region contributes to the ecosystem restoration29.

a The multi-year average values of precipitation, temperature and snow cover in the historical period (historical; 1985-2019), as well as the early phase (EP; 2029-2063) and the late phase (LP; 2065-2099) under two climate forcing scenarios (SSP126-low forcing scenario &SSP585-high forcing scenario). The ‘Historical’ indicates the multi-year average value in the historical period. The ‘SSP126-EP’ indicates the average value in the early phase under the low forcing scenario. The ‘SSP126-LP’ shows the value in the late phase under the low forcing scenario. The ‘SSP558-EP’ shows the value in the early phase under the high forcing scenario. The ‘SSP558-LP’ shows the value in the late phase under high forcing scenario. b The Pearson correlation coefficients and Mantel test of the WEE nexus (HP-EI-Fp) with the relative factors, including the hydropower development (Dam Construction-Dam; Reservoir Replenishment-Rep FlowSize), the Climate Change (Climate Scenarios Setting-Climate Scenarios; Multi-year average precipitation-Precipitation; Multi-year average temperature-Temperature; Multi-year average snow cover-SonwCover), and the multi-year average EIs, Fps, flows in the runoff segments (RepR, RRU, RRD and BR). The asterisks indicate the significant correlations (p < 0.05). The colours of the lines represent the mantel’s significance (p), and the thicknesses represent the mantel’s correlation (r). The dashed lines indicate the negative influence, while another means the positive impact. The figure was drawn on a website (https://www.chiplot.online/). c The multi-year average discharges in the RepR, RRU, RRD and BR in the historical period, the early and late phases under the climate forcing scenarios without hydropower development.

Regarding hydropower production, Hydropower production does not increase significantly at replenishment flow change. However, the flows during the flood period rise due to climate change (Fig. 4e), leading to a steady growth in hydropower production, which becomes particularly significant under SSP558. Notably, the correlation between hydropower generation and both EI and Fp in the RRU is particularly strong (p < 0.05), and it also demonstrates a significant positive correlation with the discharge in the RR (p < 0.05). This suggests that the increased hydropower generation results in a more unstable aquatic ecosystem and a stronger flood control capacity30.

In terms of flood control performance, the RRU exhibits the highest flood control capacity, which decreases as water resources revert to the natural river (BR). Furthermore, drastic climate change has been observed to result in a reduction in the flood control capacities. This is primarily attributable to the rise in temperature, melting of ice and snow, and increase in natural flood volume, which have resulted in alterations to the flood control capacities (see Figs. 4e and 5c). The correlation analysis indicates a significant positive correlation between the Fps and the inflow in the RR. The Fps in RepR notably correlates negatively with climate change and positively with hydropower development. This implies that hydropower development can mitigate the flood disasters in the ML-BXK basin caused by climate change31.

Comparative Discussion with Existing WEF (Water-Energy-Food) Nexus Studies

Existing WEF studies in the YT River Basin (e.g., Lyu et al. 32) emphasize hydropower’s role in balancing energy, agriculture, and flood control, demonstrating enhanced dry-season flows for navigation (increase navigable to four months per year in Bangladesh) and irrigation assurance (be able to reach 100% in Bangladesh). While these findings align with our conclusions on reservoir-driven runoff stabilization (Section “Comparative Discussion with Existing WEF (Water-Energy-Food)Nexus Studies), prior work largely neglects climate-ecosystem dynamics. Our study advances this field by integrating climate scenarios (SSP126/585) and glacial/snowpack processes into a coupled WEE framework, explicitly quantifying ecosystem impacts via eco-index (EI) metrics-a critical gap in transboundary analyses. For instance, Lyu et al. 32 reported flood reduction of up to 32.6% in India and 14.8% in Bangladesh through reservoir storage but did not address climate-amplified flood risks or ecological trade-offs. Our results reveal that hydropower operations under SSP126 reduce flood peaks by 29.2% while maintaining EI < 0.45, achieving synergies unattainable in static WEF models. Furthermore, NSGA-III optimization identifies medium replenishment flows (1000 m³ s−1) as optimal for balancing energy output, ecological stability, and flood resilience nuanced resolution beyond conventional sectoral trade-off analyses. This dynamic, climate-integrated approach provides a more actionable foundation for transboundary cooperation, addressing both hydrological variability and ecosystem integrity in international river management.

Potential for Transboundary Cooperation

The Chinese government has actively pursued a strategy to balance water resource development while mitigating alterations to runoff processes. First, the government has opted for a gradual filling approach during the flood season to minimise hydropower development’s disturbance on the aquatic ecosystem. Our study indicates that the reservoir storage volume constitutes only approximately 10% of the annual normal water volume at the Pasighat outlet. Additionally, the convergence of multiple tributaries downstream of Pasighat mitigates changes in runoff processes, exerting minimal influence on total runoff volume and processes in Bangladesh and India. This approach also aids in replenishing flow, supporting agricultural irrigation and ensuring navigation security downstream during dry periods32.

Regarding the Reduction regime, the Chinese government has meticulously evaluated the water transfer port selection process. The water transfer port from the RRU to the Palung Tsangpo confluence spans approximately 20 km of river section characterised by a deep valley, large riverbed aspect ratio (15.4‰ on average), and four waterfalls with drops exceeding 150 m. This river regime forms a significant natural geographical barrier to fish, resulting in relatively low fish species diversity and abundance. Water transfer from the second reservoir has a limited impact on the aquatic ecosystem. The confluence of Palung Tsangpo with other tributaries maintains relatively stable runoff in the RRD during both dry and flood seasons, with runoff consistently exceeding 90% of the annual normal flow. Consequently, hydropower development has a minor impact on fish spawning and breeding activities.

The advantages of hydropower development become more apparent in the context of climate change. Under the low forcing scenario, the disturbances to ecosystems resulting from hydropower development appear to maintain those caused by climate change. Moreover, there is evidence of a slight suppression of ecosystem impacts caused by climate change in the Pasighat outlet (Fig. 4c). Concurrently, hydropower development can yield electricity benefits in China while also considering the flood control function for the downstream region. Even under SSP558-LP, it has consistently provided a certain degree of flood control for the downstream region, thereby safeguarding the lives and properties of the downstream countries (Fig. 4c).

In conclusion, the Chinese government has been implementing scientifically grounded water resource development and management initiatives. These efforts have successfully minimised ecosystem impacts in the RR and BR while facilitating downstream agricultural irrigation and navigation through flow replenishment during dry seasons. Additionally, hydropower development provides flood protection downstream without increasing ecosystem impact under climate change. These endeavours have played a pivotal role in promoting mutual benefits among nations sharing cross-border rivers and fostering harmonious coexistence between humans and nature.

Limitations and Further Study

The total runoff and process simulation and WEE modelling framework for the Yarlung Tsangpo River is not perfect and has some limitations:

-

(1)

Only a limited number of studies have delved into modelling the runoff process from the Nuxia hydrological station to the Pasighat outlet, taking into account the dynamics of glacial snowmelt and snow cover. Most studies have primarily concentrated on simulating runoff above the Nuxia station.

The establishment of the Dexing hydrological station in 2015 has provided relatively short hydrological series data, predominantly focusing on the flood season. Consequently, there remains a lack of clarity regarding the simulation of hydrological processes during the dry season. Preliminary findings indicate a slight overall decrease in simulated discharge during the dry period (data not yet published).

The reservoirs constructed in the Yarlung Tsangpo River Basin are day-regulating reservoirs with small capacities and are situated far from the planned hydropower development areas. Consequently, their impact on the river runoff process and total water volume is minimal.

-

(2)

The boundaries defining the response level of indicators within the WEE nexus framework remain unclear. Although the ecosystem impacts and the flood control capacities were quantified, a definitive criterion value indicating significant ecosystem changes could not be determined. Nonetheless, referencing the ecosystem impacts of other rivers19, it appears that the degree of ecological impacts in the BR and RepR is generally low compared to those in other river systems. Further analysis is necessary to ascertain the specific effects of total runoff and process alterations on the ecosystem, aiming to establish a more robust physical interpretation for the EI. Additionally, the normalisation process for EI was based on only 17.9% of the initial IHA parameters characterizing the initial series, indicating a lack of comprehensive characterisation.

Regarding the flood control capacity, it was characterised using the average peak clipping rate of maximum incoming floods over one day, three days, and seven days, with no consideration for variations in incoming peak time and frequency. This approach was chosen due to the gradual storage operating procedure utilised in reservoir storage, which results in minimal variation in its impact on the runoff process. Consequently, the peak clipping rate suffices to characterise the flood control capacity effectively.

-

(3)

The operation rules employed in this study come from actual reservoir operation documents, and the impacts of different operation policies on the WEE nexus are not considered. Further research could be developed in this aspect.

-

(4)

The study indicates a notable intensification of ecosystem impacts in the late stage under the high forcing scenario. A threshold for steady-state conditions exists for hydropower development, whereby ecosystem impacts remain steady under climate change. Nevertheless, the precise value of this threshold remains uncertain, necessitating the examination of additional forcing scenarios to ascertain its accurate value.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the viability of balancing hydropower development, ecological conservation, and climate resilience in the Yarlung-Tsangpo Grand Canyon. Key takeaways include:

-

(1)

Optimal Reservoir Operations: Medium replenishment flow (1000 m³/s) during dry seasons optimizes the WEE nexus, yielding 2231 × 108 kWh of hydropower annually, 22.8% flood peak reduction, and moderate ecosystem impact (EI = 0.45). This strategy stabilizes runoff processes while sustaining downstream agricultural and navigational needs.

-

(2)

Climate Resilience: Hydropower systems enhance flood control under climate change, reducing peak flows by 29.2% under SSP126. Even under high-forcing scenarios (SSP585), reservoirs mitigate flood risks, safeguarding downstream regions despite rising temperatures.

-

(3)

Ecosystem Synergy: Low-forcing scenarios (SSP126) show aquatic ecosystems maintain stability through sustained snowpack and glacial meltwater supplies, where gradual replenishment rather than abrupt melting ensures consistent hydrological regimes. Hydropower operations suppress climate-induced disturbances in downstream segments (e.g., BR), highlighting the dual benefits of energy production and ecological preservation.

-

(4)

Transboundary Benefits: Strategic reservoir management minimizes cross-border impacts, as evidenced by the controlled initial impoundment volume constituting less than 10% of the annual inflow volume in the downstream country. Flood control and dry-season flow stabilization foster regional cooperation, aligning China’s energy goals with downstream flood security and irrigation needs.

By integrating hydrological modelling, multi-objective optimization, and climate scenario analysis, this work provides actionable insights for sustainable water-energy governance in fragile, geopolitically sensitive basins. Future efforts should focus on refining ecosystem impact thresholds and adaptive operational rules to further enhance resilience.

Methods

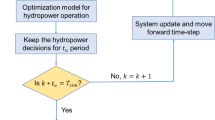

WEE Model Framework

The WEE nexus modelling framework relies on the WEP-L model33,34,35 and NSGA-III Optimization model36,37, integrated with the future climate scenarios and scheme analysis of operating rules for the cascade hydropower system (Fig. 6). Section 4.2 aims to establish criteria for reservoir replenishment during non-flood seasons following trade-offs within the WEE nexus. In Section 4.3, the hydropower system’s operations are examined under different climate scenarios to assess their impact on the WEE nexus within the ML-BXK basin.

Step 1: Topography and meteorological data are input into the WEP-L model to simulate the hydrological process of the YT river basin. The model parameters are then calibrated based on the observed discharge, glacier mass balance and snow cover data. Step 2: Meteorological data under future climate scenarios are input into the WEP-L model to simulate future hydrological processes in the basin. Step 3: Under the constraints of the cascade reservoir scheduling rules and the “Water-Energy-Ecosystem” objectives, the NSGA-III model runs to reveal the changes in the WEE nexus under different climate-forcing scenarios. Step 4: The performance and changing patterns of the three objectives under various scenarios are analyzed.

WEP-L Distributed Hydrological Model and Data

The WEP-L model was employed for simulations above Pasighat in the Yarlung Tsangpo River basin, covering a total area of 241,000 km². The basin was partitioned into 10234 sub-basins and 20345 computational units based on water patterns and terrain, with a simulation step of 84,600 s (daily). The snow and glacier processes are considered38, and the Correlation Coefficient (CC) and the Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) have been applied to verify the accuracy of the snow cover simulation (proportion from 0 to 100%)32,38. The accuracy of the discharge simulation is evaluated using the Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient (NSE) and Percent Bias (PBIAS)32.

In the hydrological model in this study, gauged daily meteorological data (precipitation, maximum and minimum temperature, relative humidity, wind speed and solar radiation) are obtained from the China Meteorological Administration. The daily and monthly discharge time series from 1985 to 2019 at Yangcun, Nuxia and Dexing (built in 2015) hydrological stations are obtained from the Tibet Bureau of Hydrology and Water Resources (Fig. 1b). The model is based on a digital elevation model (DEM) raster with a resolution of 1 km x 1 km, which was obtained by resampling a 90 m x 90 m raster downloaded from the Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn). The 1 km raster dataset of Chinese soil characteristics was provided by the Resource and Environment Cloud Platform of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). The Chinese Academy of Sciences has released land cover data for six periods: 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015. The glacier data were obtained from the First and Second Chinese Glacier Inventory39,40,41, and the validations toward the glacial freeze-thaw were the observed glacier mass balances of Parlung NO.94, GURENHEKOU and ZHONGXI Glaciers acquired from World Glacier Monitoring Service (https://wgms.ch/). The reconstructed glacier mass balance of the Parlung NO.94 glacier was also used to enhance model reliability42. Daily snow cover data are downloaded from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://doi.org/10.11888/Snow.tpdc.271381). More details of the input and output datasets are displayed in Table S4.

Future Climate Scenarios

According to the sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6), five global climate models (GCMs) are selected for the performance evaluation of the WEE nexus under climate change in the ML-BXK basin, namely GCM1 (GFDL-ESM4), GCM2 (HadGEM3-GC31-LL), GCM3 (IPSL-CM6A-LR), GCM4 (MIROC6), GCM5 (NorESM2-LM) (https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6). Daily climate data from 2029 to 2099 are derived from these GCMs. Moreover, two shared socio-economic pathways (SSPs) are considered, i.e., SSP126 is a reimagining of the optimistic scenario RCP2.6, designed to simulate a development path that is compatible with the 2 °C target. SSP585 is an update of the CMIP5 scenario RCP8.5, combined with socioeconomic considerations.

Objectives and Constraints

The operation process of the cascade hydropower system is a typical multi-variable, multi-objective, and complex scheduling problem. In this study, we employed the NSGA-III to generate the three-dimensional Pareto fronts for multi-objective optimization. The NSGA-III represents an enhanced iteration of the Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA-II). It incorporates a reference point mechanism, facilitating more effective global optimization and demonstrating strong robustness with the solving performance43. Moreover, the model aims at maximizing hydropower generation and flood mitigation, and minimizing ecosystem impacts. After the parameter optimization process, the population number, generation number, crossover coefficient and mutation coefficient were finally determined to be 100, 100, 0.9 and 0.1, respectively.

(1) Water-Energy-Ecosystem objectives

The term “Water-Energy-Ecosystem nexus” signifies the interplay between Hydropower generation (Energy), Ecosystem impact (Ecosystem), and Flood control capacity (Water). This nexus is characterised by three indicators: Hydropower Production (HP), Eco-Index (EI), and Flood peak clipping Rate (Fp).

a) Hydropower generation

The hydropower production (HP) is defined as

where HP denotes the annual electricity generation from hydropower plants (kWh); Ni denotes the actual output of the hydropower plants in ith day (kW); K is an efficiency parameter, K = 8.5; Hnet denotes the net water head; GQi denotes the guaranteed output in ith day (kW); ICi denotes the installed capacity (kW). Equations 1–3 represent those reservoirs’ (the first, third reservoirs and hydropower plants) annual and daily output. The HP value in the optimization objective is the multi-year average electricity generation.

b) Ecosystem impact

The eco-index (EI) is used to evaluate hydrological alternation and aquatic ecosystem impacts due to hydropower development and is defined below19.

where wp denotes the weight of the pth parameter, depending on the correct contribution rate of the pth principal components (PCs), as shown in Table S5; p denotes the total number of PCs chosen from the IHA; Ar,p denotes the value of the pth PC after reservoir operation (regulated); Au,p denotes the value of the pth PC under nature conditions (unregulated). The smaller the EI, the lower the hydropower development disturbances to the natural flow regime. The EI value in the optimization objective is multi-year averages.

c) Flood control capacity

The flood peak clipping rate (Fp) of the runoff regimes serves as an indicator for assessing the flood control operations performed by the cascade hydropower system, effectively representing the flood control capacity44. The definition is outlined as follows:

where Vr,k denotes the maximum flood volume after the reservoir operation in 1, 3, 7 days (m3); Vu,k denotes the maximum flood volume under natural conditions in 1, 3, 7 days (m3). The Fp uses the maximum flood peak to flood a day, three days and seven days of average peak clipping rate. The Fp value in the optimization objective is multi-year averages. flood control capacity

(2) Operation Rules/Constraints

To explore the influence of the cascade reservoirs regulation within the ML-BXK basin, we adopted the Standard Operation Policy (SOP) model45 that includes the effects of environmental flow, flood discharge and others. The first reservoir is the controlling reservoir and has a significant impact on hydrological alternation. Its constraints include water balance, maximum storage, minimum storage, environmental flow, backfill process, and river replenishment. The back-fill process (flood season) is defined as

The river replenishment (dry&normal season) is defined as

where Qout,t denotes the outflow of the reservoir in the tth month (m3 s−1); Qre denotes the flood retention in the reservoir (m3 s−1); Qrp denotes the flow for river replenishment and is a constant (m3 s−1); Qe-flow denotes the discharge with the e-flow constraint (m3 s−1); Si-1 denote the volumes of ending water storage on day i-1 (m3); Sele denotes the minimum water storage for electricity generation (m3). Constraints (6&7) are exclusively applicable to the first reservoirs. All other constraints pertain to the supplementary information for further details.

In addition to the above constraints, an additional maximum storage constraint was added for the drainage of sand during the flood season in the second and third reservoirs

Flood season:

Dry&Normal season:

Where Sdead denotes the dead water storage (m3); Smax denotes the maximum water storage (m3) and Stotal denotes the reservoir storage capacity (m3). The storage processes of hydropower reservoirs were not considered due to the limited water storage capacity.

Scenario Setting and Analysis

This study employs the WEP-L distributed hydrological model to simulate daily variations in total runoff and associated processes from 1985 to 2019. Furthermore, based on future climate scenarios, the model predicts daily variations in total runoff and processes from 2029 to 2063 (Early Phase) and 2065 to 2099 (Late Phase) under hydropower development.

The scenario settings are divided into two parts: (1) Scenario As: Reservoirs replenish varying flow sizes to the river during dry periods to achieve consistent power generation. The selected flow sizes (Qrp) are 600, 800, 1000, 1200, and 1400 m3 s−1. (2) Scenario Bs: WEE nexus change in the early and late phases under two climate forcing scenarios (SSP126-low forcing scenario &SSP585-high forcing scenario). For elucidating the regulatory effects of hydropower development on river systems under climate change in Scenario Bs, the simulation that exclusively considers climatic variations while disregarding the impacts of water infrastructure operations is defined as the “Only considering Climate Change (Only CC)” mode, thereby isolating the individual impacts of climate change on the runoff processes. Other Scenario Bs all consider hydropower development.

The study employed ANOVA analysis to identify the intrinsic differences in the objective index. The relationship between the response of climate factors or reservoir scheduling parameters to the objective indices was revealed using the Pearson correlation and Mantel test. The Mantel test, a permutation-based nonparametric statistical method, shares a homologous algorithmic framework with Pearson correlation analysis, as both approaches quantify the strength of linear associations between variables for correlation assessment. Compared to conventional bivariate correlation analysis, the primary advantage of this methodology lies in its capability to handle multivariate data structures, specifically enabling the examination of associations between a multivariate explanatory matrix and a univariate response variable. When the explanatory matrix reduces to a single variable, the dimensionality-reduced form of its mathematical model becomes equivalent to Pearson correlation analysis, resulting in statistically indistinguishable outcomes in terms of hypothesis testing efficacy and inferential conclusions46. Given the distinct EI and Fp across different segments (RepR, RR and BR), the EI and Fp matrices, incorporated multi-year average values for the entire river basin and individual segments, are employed for the Mantel test to evaluate their correlations with other indicators. The significance of each correlation was evaluated using 10,000 permutations. The specific classifications for some important indicators are shown as follows. Dam Construction: 0-Without Dam, 1-Dam; Climate Scenarios Setting: 0-Historical, 1-SSP126, 2-SSP558; Period: 0-Historical, 1-Early Phase, 2-Late Phase.

Data availability

Due to existing data governance policies in China, the streamflow data are not publicly available. The data needed in Fig. 1 are explained in Section 6.2. Other data is available in the “SourceData.xlsx” file on GitHub (https://github.com/ZhangFengbo-cloud/Data-for-CEE). The data are divided into different sheets according to the different Figures. All observed and simulated data are included for the reader to use directly. For instance, the “Fig. 2b” sheet included the simulated and observed Sonwcover fraction.

Change history

01 July 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02512-w

Abbreviations

- BR:

-

back regime

- EI:

-

eco-index

- EP:

-

early phase

- Fp:

-

flood peak clipping rate

- IHA:

-

integrated habitat assessment

- LP:

-

late phase

- NSE:

-

Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency

- Only CC:

-

Only considering Climate Change

- PCA:

-

principal component analysis

- RE:

-

relative error

- RepR:

-

replenishment regime

- RR:

-

reduction regime

- RRD:

-

reduction regime downstream

- RRU:

-

reduction regime upstream

- SSPs:

-

Shared Socioeconomic Pathways

- WEE:

-

water-energy-ecosystem

References

Chang, X., Liu, X. & Zhou, W. Hydropower in China at present and its further development. Energy. 35, 4400–4406 (2010).

Li, X. et al. Hydropower development situation and prospects in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82, 232–239 (2018).

Shen, J. J. et al. Impacts, challenges and suggestions of the electricity market for hydro-dominated power systems in China. Renew. Energy. 187, 743–759 (2022).

Jiao, Y. Key R&D missions of China’s hydraulic-hydropower industry in view of the nation’s strategic needs. J. Intell. Constr. 2,1–4 (2024).

Yang, Y. & Zhang, C. Key aspects of the future hydropower development in China. Hydropower New Energy. 09, 1–7 (2021).

GOV.CN. The 14th five-year Plan and Outline of Vision 2035 for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/13/content_5592681.htm (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Evolution of eastern Tibetan river systems is driven by the indentation of India. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 256 (2021).

Favre, A. et al. The role of the uplift of the Qinghai‐Tibetan Plateau for the evolution of Tibetan biotas. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 90, 236–253 (2015).

Li, J. & Fang, X. Uplift of the Tibetan Plateau and environmental changes. Chin. Sci. Bull. 44, 2117–2124 (1999).

Zhang, Z. et al. Sedimentary provenance perspectives on the evolution of the major rivers draining the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Earth Sci. Rev. 232, 104151 (2022).

Ghosh, S. & Dutta, S. Impact of climate change on flood characteristics in Brahmaputra basin using a macro-scale distributed hydrological model. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 121, 637–657 (2012).

Lutz, A. F. et al. Consistent increase in High Asia’s runoff due to increasing glacier melt and precipitation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 587–592 (2014).

Liu, W. et al. Impacts of climate change on hydrological processes in the Tibetan Plateau: a case study in the Lhasa River basin. Stoch. Env. Res. Risk A. 29, 1809–1822 (2015).

Xuan, W. Hydrological responses to climate change in Yarlung Zangbo River basin, Southwest China. J. Hydrol. 597, 125761 (2021).

Kuriqi, A. et al. Water-energy-ecosystem nexus: Balancing competing interests at a run-of-river hydropower plant coupling a hydrologic–ecohydraulic approach. Energy Convers. Manag. 223, 113267 (2020).

Zhong, R., Zhao, T. & Chen, X. Evaluating the tradeoff between hydropower benefit and ecological interest under climate change: How will the water-energy-ecosystem nexus evolve in the upper Mekong Basin? Energy 237, 121518 (2021).

He, S. et al. A novel impoundment framework for a mega reservoir system in the upper Yangtze River basin. Appl. Energy 305, 117792 (2022a).

Jager, H. I. & Smith, B. T. Sustainable reservoir operation: Can we generate hydropower and preserve ecosystem values? River Res. Appl. 24, 340–352 (2008).

Li, D., Wan, W. & Zhao, J. Optimizing environmental flow operations based on explicit quantification of IHA parameters. J. Hydrol. 563, 510–522 (2018).

Qi, P. et al. Optimizing environmental flow based on a new optimization model in balancing objectives among river ecology, water supply and power generation in a high-latitude river. J. Environ. Manag. 342, 118261 (2023).

Olden, J. D. & Poff, N. L. Redundancy and the choice of hydrologic indices for characterizing streamflow regimes. River Res. Appl. 19, 101–121 (2003).

Gao, Y. et al. Development of representative indicators of hydrologic alteration. J. Hydrol. 374, 136–147 (2009).

Webb, R. H. & Leake, S. A. Ground-water surface-water interactions and long-term change in riverine riparian vegetation in the southwestern United States. J. Hydrol. 320, 302–323 (2006).

Gong, Y. et al. Classification and distribution of large-scale high-position landslides in southeastern edge of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 81, 311 (2022).

Wang, Z. & Zhang, C. Bedforms, energy dissipation and disaster mitigation mechanism in mountain rivers of Southwest China. J. Hydraul. Eng. 50, 124–134 (2019).

GOV.CN. Hydropower planning report on the lower reach of the Yarlung Zangbo River https://www.news.cn/20241225/5cc61d9f02ea453b8b8e553aa0663c07/c.html (2023).

Chang, C. et al. Long-term warming destabilizes aquatic ecosystems through weakening biodiversity-mediated causal networks. Glob. Chang. Bio. 26, 6413–6423 (2020).

Poff, N. L., Brinson, M. M. & Day, J. W. Aquatic ecosystems and global climate change. Pew Center Glob. Clim. Chang. Arlington, VA. 44, 1–36 (2002).

Milner, A. M., Brown, L. E. & Hannah, D. M. Hydroecological response of river systems to shrinking glaciers. Hydrol. Proce. Internat. J 23, 62–77 (2009).

Kuriqi, A. et al. Ecological impacts of run-of-river hydropower plants—Current status and future prospects on the brink of energy transition. Renew. Sustain. Energy Reviews, 142, 110833 (2021).

Yun, X. et al. Reducing climate change induced flood at the cost of hydropower in the lancing-mekong River Basin. Geophy. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094243 (2021).

Lyu, H. et al. Water-energy-food nexus in the Yarlung Tsangpo-Brahmaputra River Basin: Impact of mainstream hydropower development. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 45, 101293 (2023).

Jia, Y. et al. Development of WEP model and its application to an urban watershed. Hydrol. Proce. 15, 2175–94 (2001).

Wang, H. et al. Study on Interaction between Surface Water and Groundwater in Typical Reach of Xiaoqing River Based on WEP-L Model. Water 15, 492 (2023).

Wang, P. et al. Application of an improved distributed hydrological model based on the soil-gravel structure in the Niyang River basin, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Hydro. Earth Syst. Sci. 27, 2681–2701 (2023).

He, S. et al. Multi-objective operation of cascade reservoirs based on short-term ensemble streamflow prediction. J. Hydrol. 610, 127936 (2022b).

Ren, L., Li, Y., & Zhou, S. An Improved NSGA-III Algorithm for Scheduling Ships Arrival and Departure the Main Channel of Tianjin Port. (IEEE Access, 2024).

Sun, H. et al. Regional difference in runoff regimes and changes in the Yarlung Zangbo river basin. Hydro. Earth Syst. Sci. 1–53 (2023).

Liu, S., Guo, W. & Xu, J. The second glacier inventory dataset of China (version 1.0) (2006-2011). Nat. Tibet. Plat. Data Center. https://doi.org/10.3972/glacier.001.2013.db (2012).

Liu, S. et al. The contemporary glaciers in China based on the Second Chinese Glacier Inventory. Acta Geo. Sin 70, 3–16 (2015).

Liu S. et al. Research on the impact and risk of climate change on glaciers. (Sci. Press, 2017).

Mu, J. X. et al. Mass balance variation of continental glacier and temperate glacier and their response to climate change in western China: Taking Urumqi Glacier No. 1 and Parlung No. 94 Glacier as examples. Arid Land Geography 42, 20–28 (2019).

Ishibuchi, H. et al. Performance comparison of NSGA-II and NSGA-III on various many-objective test problems. (IEEE, 2016).

He, Y. et al. Reservoir flood control operation based on chaotic particle swarm optimization algorithm. Appl. Math. Mod. 38, 4480–4492 (2014).

Morris, G. L. & Fan, J. Reservoir sedimentation handbook: Design and management of dams, reservoirs, and watersheds for sustainable use. (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1998).

Goslee, S. C. & Urban, D. L. The ecodist package for dissimilarity-based analysis of ecological data. J. Stat. Software 22, 1–19 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Key Research Program of China (grant numbers 2022YFC3205000); the National Nature Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 52394233, U2240202) and the Independent Research Project of State Key Laboratory (grant number WR110146B0022024). Thanks to the anonymous reviewers for the very pertinent and sound advice!.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fengbo Zhao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing-original draft. Qin Yang, Peng Hu, Jianhua Wang: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing-review & editing. Qinhui Zeng, Long Yan, and Hua Liu: Data curation, Investigation, and Writing-review & editing. Baolong Zhao, Jiaxuan Tang and Kang Zhao: Methodology and Validation. Yining Zang: Validation and Writing-review & editing. Wei Liu: Data curation and Investigation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Benyou Jia and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Heike Langenberg and Aliénor Lavergne. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, F., Yang, Q., Wang, J. et al. Hydropower system in the Yarlung-Tsangpo Grand Canyon can mitigate flood disasters caused by climate change. Commun Earth Environ 6, 323 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02247-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02247-8