Abstract

Ocean alkalinity enhancement is a potential strategy for gigatonne-scale atmospheric carbon dioxide removal. It uses alkaline substances to convert seawater carbon dioxide into (bi)carbonate, enabling uptake of additional carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. A critical knowledge gap is how ocean alkalinity enhancement could influence marine plankton communities. Here we conducted 19 ship-based experiments in the Equatorial Pacific, examining three prevalent alkaline substances (sodium hydroxide, olivine, and steel slag) and their effects on natural phytoplankton populations under realistic and moderate alkalinity enhancements (16–29 μmol kg−1). Results demonstrate that sodium hydroxide had a negligible effect on phytoplankton while providing predictable alkalinity. Conversely, olivine disrupted plankton, especially cyanobacteria, heterotrophic bacteria, and picoeukaryotes while only providing 0.06 mmol alkalinity g−1 olivine. Steel slag moderately changed phytoplankton communities and fertilized growth while delivering 8 mmol alkalinity g−1 slag. Our study helps to determine which alkaline substance could be suitable for application in the Equatorial Pacific.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Keeping global warming within 1.5 to 2 °C requires a rapid reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and atmospheric carbon dioxide removal (CDR) between 100 and 1000 Gt carbon dioxide (CO2) before 21001. Gigatonne-scale CDR could be achieved with a portfolio of methods2,3,4. Ocean alkalinity enhancement (OAE) is an emerging marine CDR method. OAE requires alkaline materials which convert seawater CO2 into bicarbonate (HCO3-) and carbonate (CO32−), thereby enabling the uptake and storage of atmospheric CO2 for ~100,000 years5. The scaling potential of OAE is considered high due to the vastness of the ocean and its surface area where OAE could be implemented globally2,6,7.

There are different types of alkaline substances that can be used for OAE. These include natural alkaline rocks containing olivine (Mg2SiO4)8,9, alkaline by-products like steel slags containing CaO9,10, or alkaline liquids like sodium hydroxide (NaOH)11,12. Alkaline substances differ in how they are sourced and processed, how efficient they are in releasing alkalinity, and how they may impact the marine environment following application. Olivine and steel slag are solid materials sourced from land deposits and industrial applications and need to be pulverized before their application to accelerate dissolution and subsequent delivery of alkalinity. NaOH is sourced from seawater, and its production through electrochemistry requires substantial renewable energy and neutralization of acidic by-products7. Due to the different sources, delivery approaches to the ocean (as solid or as liquid) and the added alkalinity level, each of these materials has specific environmental effects. NaOH can affect marine organisms through abrupt changes in carbonate chemistry, while olivine and slag dissolve more slowly and not only modify carbonate chemistry but also liberate alkaline earth metals, silicic acid, phosphate, and a range of trace elements into the marine environment13,14.

Phytoplankton communities in the surface ocean are the base of almost the entire marine food web and are strongly regulated by seawater chemistry; therefore, the feasibility of OAE strongly depends on the effect it will have on these crucial organisms. All OAE feedstocks can affect phytoplankton by increasing dissolved inorganic carbon concentrations and pH. Some solid-phase OAE feedstocks may also release elements which are scarce in seawater, so their additions may preferentially enhance or inhibit the growth of some phytoplankton species more than others15,16. Furthermore, the addition of particles to seawater (e.g. rock dust) could affect light availability and the grazing of phytoplankton by zooplankton, both of which could affect phytoplankton productivity and community structure. Thus, it is important to identify winners and losers in marine ecosystems to OAE approaches to enable informed decisions on which OAE methods could lead to a net benefit for the climate and the environment.

The oceanic surface waters are a potentially feasible location for OAE and could overcome scalability limitations of the approach17, circumvent efficiency losses related to OAE in sediments18,19,20, and avoid adding further pressures to coastal ecosystems where stakeholder engagement is typically higher than in the open ocean21. Here, we present results from 19 shipboard incubation experiments where we investigated physiological and ecological effects of three OAE substances (NaOH, olivine, and steel slag) on phytoplankton communities from the Equatorial Pacific, a region where biological productivity is primarily limited by trace metal availability22. Our dataset covers a wide range of environmental conditions from eutrophic coastal and equatorial upwelling to oligotrophic conditions in the western Pacific. We aimed for comparable levels of OAE (around 23 µmol kg-1 alkalinity increase) between treatments to facilitate the comparability between the three approaches. Our results fill a critical knowledge gap on the effects of an emerging atmospheric CO2 removal method in the tropical ocean.

Results

Physiochemical environment of incubation experiment

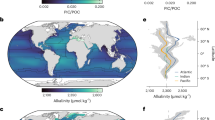

The experiments were conducted on R/V Sonne (SO298) during the GEOTRACES Equatorial Pacific Ocean transect from Ecuador to Australia (from 81.902°W to 161.732°E). The on-deck incubation experiments were carried out between 16th April 2023 and 27th May 2023. The cruise commenced in Guayaquil (Ecuador) and passed the Galapagos Islands steaming west along the equator (Fig. 1a). Coastal experiments were conducted close to Ecuador (experiments 1,2), where average nitrate and nitrite (NOx−), silicic acid (Si(OH)4), and phosphate (PO43−) concentrations were 0.4, 1.6, and 0.2 µmol L−1, respectively. The macronutrient concentrations (Supplementary Data 1) were highest west of Galapagos (experiment 3-5) and remained relatively high further west for experiments 6-18 (2.7–5.5 µmol L−1 NOx−, 1.6–2.4 µmol L−1 Si(OH)4, and 0.4–0.6 µmol L−1 PO43−, Fig. 1b). A strong linear relationship was found between the NOx− and PO43− concentrations (R2 = 0.97). Concentrations of macronutrients and chlorophyll a (Chl-a) decreased to lower levels at experiment 19 furthest west on the transect (1.5 µmol L−1 Si(OH)4, 0.2 µmol L−1 PO43− with NOx− below the detection limit), which was similar to experiments 1 and 2.

a Experimental location on the world map and the surface Chl-a data from MODIS-Aqua during the research voyage (averaged from 15 April 2023 to 2 June 2023)64. b Initial nitrate + nitrite (µmol L−1, orange dots) and phosphate (µmol L−1, grey dots), silicic acid (µmol L−1), and alkalinity concentrations (µmol kg−1) in the incubation experiments. The bars represent the standard error (n = 3). The numbers indicate locations where seawater for the respective incubation experiments was collected.

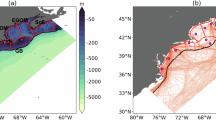

In each experiment, a control and three OAE treatments were conducted in triplicate. Alkalinity at the experimental sites ranged from 2215 to 2335 µmol kg−1, which represents alkalinity in the control and before treatment manipulation (Fig. 1b). OAE treatments with 300 µL L−1 0.1 M NaOH (NaOH-OAE), 0.4 g L−1 ground olivine powder (olivine-OAE) and 0.002 g L−1 of steel slag powder (slag-OAE) enhanced the alkalinity by 29 ± 2, 24 ± 2, and 16 ± 1 (mean ± standard error) µmol kg−1, respectively (Fig. 2a). This corresponded with increases in pHT from 7.950 ± 0.007 to 8.009 ± 0.006 (NaOH-OAE), 7.989 ± 0.005 (olivine-OAE), and 7.987 ± 0.005 (slag-OAE). Note that the pHT increase in slag-OAE is similar to olivine-OAE despite lower alkalinity enhancement because slag fertilized growth (Fig. 2c), leading to a pHT increase due to photosynthetic activity. Of the two tested solid OAE materials, slag released 8 mmol of alkalinity g−1 while olivine released 0.06 mmol g−1. Slag was therefore ~130 times more effective for OAE (per weight) within the 48 h of experiment. Slag and olivine also increased Si(OH)4 concentrations by 2.6 and ~10.5 µmol L−1 respectively, and the slag increased PO43− by 0.1 µmol L−1 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Slag-OAE resulted in 0.4 ± 0.1 µmol L−1 more NOX− drawdown than the control and other treatments over the course of the study.

a Alkalinity (µmol kg−1), b pHT, c Chl-a (µg L−1), and d Fv/Fm. The data from the 19 incubation experiments were included. Circles represent the mean values from three replicates in each experiment. Box limits show the central 50% of the data, with the median marked by a central line. Letters shown inside the boxes denote significant differences between treatments (p-value < 0.05) based on ANOVA and subsequent Tukey post-hoc tests (two-sided).

To determine the release of trace metals from alkaline materials we conducted a dissolution experiment using artificial seawater23 using the same experimental conditions as the incubation experiment (300 µL L−1 0.1 M NaOH, 0.4 g L-1 ground olivine powder and 0.002 g L−1 of steel slag powder, n = 3). We observed limited trace metal enrichment with NaOH but noticeable enrichment with olivine and slag (Supplementary Fig. 2). Both olivine and slag increased aluminium (Al) (olivine = 532 ± 37 (mean ± standard error) nmol L−1, slag = 42 ± 22 nmol L-1) and Mn (olivine = 39 ± 0.5 nmol L−1, slag = 48 ± 7 nmol L-1), while olivine also increased Co (2 ± 0.2 nmol L−1), Cu (5 ± 1 nmol L−1), and Ni (57 ± 7 nmol L−1) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Although the ∆Fe concentrations were similar in NaOH, olivine and the slag treatments (i.e., below the measurable blank limit; 2, and 7.8 nmol L−1 respectively), we hypothesize that the added minerals likely elevated bioavailable Fe concentrations because the steel slag applied herein contains 10–35% iron oxide24, which has been reported to be able to increase dissolved Fe25 and microalgal growth26. Furthermore, we suspect that the current measurement approach (direct analysis, no matrix removal) could not detect any associated small changes (likely sub-nanomole scale) in Fe due to limited detection capacity resulting from the presence of dominant sea water cations.

Response of phytoplankton communities to OAE

Net Chl-a accumulation, a proxy for net phytoplankton community growth, was on average (19 experiments) unaffected by NaOH-OAE, negatively affected by olivine-OAE, and positively affected by slag-OAE (Fig. 2c). However, there were outliers to these general trends within the 19 individual experiments (Supplementary Data 1). Based on the Tukey post-hoc test (two-sided; conducted for each experiment), NaOH-OAE increased Chl-a accumulation in 3 experiments (3, 4, and 9) and decreased Chl-a in experiment 8 (p-value < 0.05), while olivine-OAE did not negatively affect Chl-a accumulation in 5 experiments (1, 4, 6, 7, and 9). Likewise, slag-OAE had no substantial effect on Chl-a accumulation in 8 experiments (1, 2, 3, 6, 10, 12, 17, and 19). We used a multivariate linear model (Supplementary Data 4) on the relative change of Chl-a (∆r Chl-a) to explore potential reasons for the substantial deviations from the mean. The results indicate that deviations in Chl-a under NaOH-OAE occurred in areas with higher Si around the Galapagos Islands (p-value < 0.05). However, deviations could have also been caused by variability in seawater alkalinity, which happened to be high in these experiments as well (Supplementary Data 1). Significant correlation between ∆r Chl-a and ∆ alkalinity under olivine-OAE was detected, suggesting a potential dose-dependency of the Chl-a response (Supplementary Data 4). Under slag-OAE, the relative change of Chl-a was less pronounced in regions where the initial alkalinity level was higher.

The apparent maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv/Fm), an indicator of photo-physiological fitness, showed a response consistent with Chl-a under NaOH-OAE and slag-OAE but not under olivine-OAE. In olivine-OAE Fv/Fm increased while Chl-a decreased (Fig. 2d). We were initially suspicious of this result because the olivine treatment contained olivine particles that may have interfered with fluorescence measurements. However, an additional experiment to test the effect of olivine particles on Chl-a measurements (Supplementary Fig. 3a) as well as the red (i.e. Chl-a) fluorescence emission signal (692 nm) measured by flow cytometry (Supplementary Fig. 3b), confirmed that the result was robust. We attribute the divergent response between Chl-a and Fv/Fm to the profound shifts in the phytoplankton community composition observed after the olivine treatment. While nanoeukaryotes increased in abundance in the olivine treatments, all smaller phytoplankton (picoeukaryotes and picocyanobacteria) declined (Fig. 3a). Nanoeukaryotes have inherently higher Fv/Fm values than picoeukaryotes and picocyanobacteria27, so that the overall decline in Chl-a due to the decline in picophytoplankton was not reflected in Fv/Fm. This observation is important because Fv/Fm is a widely applied parameter and a potentially suitable monitoring tool to assess phytoplankton fitness over large ocean areas. The disconnect to Chl-a suggests that more challenging measurements of community composition, which are harder to scale (e.g. flow cytometry), are needed to monitor OAE impacts.

a Percentage of the changes in the abundance of each plankton group during the OAE experiments relative to the control (∆r). Circles represent the mean values from three replicates in each experiment. Box limits show the central 50% of the data, with the median marked by a central line. Letters shown inside the boxes denote significant differences between treatments (p-value < 0.05) based on ANOVA and subsequent Tukey post-hoc tests (two-sided). b Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of phytoplankton group abundance. Each dot is the average (n = 3) of OAE experiments at the 19 sites along the cruise transect.

The plankton community composition was determined with flow cytometry and divided into 6 groups: microeukaryotes, nanoeukaryotes, picoeukaryotes, Prochlorococcus, Synechococcus (both picocyanobacteria) and heterotrophic bacteria (Supplementary Fig. 4). Changes in their abundance in response to the treatments are shown for each experiment in Supplementary Data 2 and Fig. 3a. The initial phytoplankton composition was similar in experiments 1 and 2 (Supplementary Data 3), which had lower NOx− and were closer to shore (Fig. 1). Here, Synechococcus dominated the pico-cyanobacteria community by abundance ( >57%), while Prochlorococcus became numerically dominant further into the equatorial Pacific from experiment 3–19. In experiment 19 specifically, Prochlorococcus accounts for around 95% of the sampled cells. On average, NaOH-OAE did not significantly affect plankton community composition relative to the control. However, significant effects of NaOH-OAE were observed for some parameters in 3 of the 19 experiments (experiments 3, 4, and 9). The changes in abundance of Synechococcus, Prochlorococcus and nano eukaryotes under NaOH-OAE in these experiments coincided with similar changes observed under slag-OAE, suggesting that these communities were generally more sensitive to perturbation (Supplementary Data 2). In contrast, olivine-OAE strongly reduced the average abundances of picoeukaryotes (−52.7%), Prochlorococcus (−95.5%), Synechococcus (−75.0%), and heterotrophic bacteria (−72.9%) while it increased average nanoeukaryote abundance ( +49.9%). The pronounced average response of the phytoplankton community to olivine-OAE is reflected in the higher number of individual experiments where significant effects were observed. The change in community composition imposed by slag-OAE was more pronounced than under NaOH-OAE but less pronounced than under olivine-OAE. Slag-OAE increased the average abundance of microeukaryotes ( +94.4%) and nanoeukaryotes ( +83.7%) but decreased the abundance of Prochlorococcus (−21.2%) and heterotrophic bacteria (−23.6%). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Fig. 3b) revealed that the control and NaOH-OAE clusters were very similar, slag-OAE clustered slightly differently on Dimension 2 and olivine-OAE clustered very distinctly on both Dimensions 1 and 2. These insights through multivariate statistics support the conclusion that NaOH-OAE has limited, slag-OAE has moderate, and olivine-OAE has strong effect on the plankton communities.

To further investigate if the initial plankton community composition or the initial chemical conditions influenced treatment effects, we used multiple linear regression models. We analysed the relative changes in plankton abundance across all 19 experiments (Supplementary Data 4). The results indicate that the effect of NaOH-OAE on nano eukaryotes abundance was more pronounced in environments with higher ambient Si(OH)4 concentrations. In the case of olivine-OAE, effects on plankton abundance varied markedly by location. Specifically, its impact on Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus was stronger in regions with higher NOx− concentrations in the central Equatorial Pacific. Furthermore, the negative effects of olivine-OAE on heterotrophic bacteria and Prochlorococcus were more pronounced when ∆alkalinity was more pronounced, suggesting the negative effects scale with olivine dissolution. In the case of slag-OAE, effects on Synechococcus were weaker in regions with lower pHT, which were closer to the coast.

Discussion

Previous OAE experiments with plankton have focused on more extreme OAE simulations, where alkalinity enhancement was generally ≥150 µmol kg−1 14,28,29,30. Our experiments explored more moderate and arguably more realistic perturbations (alkalinity increase of ~16–29 µmol kg−1, Fig. 2a), which is in the range of the sampled regions’ initial alkalinity variability. Testing relatively small OAE perturbations was guided by the rapid dilution with unperturbed seawater that can be expected in open ocean waters17. Under the perturbation levels tested here, we observed relatively few substantial effects of NaOH-OAE on the plankton groups in 19 experiments along the cruise track in the equatorial Pacific Ocean and, on average, none of the plankton groups were affected substantially (Fig. 3a; with the exceptions mentioned in the previous section). The limited effects observed here in the open ocean align with limited effects observed in experiments with coastal plankton communities where the NaOH-OAE perturbation was much more pronounced ( >150 µmol kg−1 increase in alkalinity28,31,32). Even for calcifying phytoplankton, the alkalinity changes tested here were unlikely to have a substantial impact, given that previous experiments with even higher alkalinity enhancements showed negligible effects on calcifying phytoplankton33,34. The limited environmental effects in either moderate or high NaOH-OAE scenarios suggest that NaOH-OAE of realistic and even more extreme magnitude has limited acute effects on phytoplankton communities. The climatic benefits of NaOH-OAE may therefore outweigh its associated environmental risks in the Equatorial Pacific Ocean.

Slag-OAE increased the net growth of nano- and microeukaryotes while causing a decline in Prochlorococcus. The fertilization of the larger phytoplankton species and the associated increase in Chl-a overcompensated for the loss of Prochlorococcus so that overall bulk Chl-a increased (Fig. 2c). The fertilization of the larger phytoplankton was likely caused by supply of bio-essential trace metals such as Fe and Mn14,35, consistent with findings from in situ nanomole-level Fe fertilization experiments in the Equatorial Pacific22,36,37,38. Indeed, larger phytoplankton usually has a higher demand for these trace metals due to their lower surface area to volume ratios, which causes a reduced trace metal uptake efficiency39,40. The reason for the decline in Prochlorococcus is less clear but was likely caused by elevated trace metal concentrations (e.g. Mn and Fe)41,42 or physical disturbance by particles rather than by carbonate chemistry changes since no substantial response was observed under NaOH-OAE. Overall, these results show that slag not only causes abiotic CDR through alkalinity enhancement (8 mmol alkalinity g−1 slag) but also induces biotic CDR through trace metal fertilization. While this may be regarded as an additional benefit, we caution that such fertilization could entail a suite of complex challenges20,43 such as accounting for macronutrient reallocation from downstream regions44,45,46, or potential ocean deoxygenation47. Thus, while our results reveal comparatively high abiotic CDR efficiencies of slag-OAE at moderate environmental impacts, its biological ramifications due to (un)intentional ocean fertilization warrant further attention.

Olivine was comparatively inefficient in enhancing alkalinity (0.06 mmol alkalinity g−1 olivine) while showing pronounced adverse effects on some phytoplankton, notably strongly reducing Prochlorococcus, Synechococcus, and picoeukaryote populations, especially in the open ocean region where Prochlorococcus was the dominant species by cell count. It is likely that the comparative inefficiency of olivine-OAE could be improved through application of smaller olivine grains. However, this would also have increased the release of other dissolution products and thus likely increased adverse effects on phytoplankton. The reason for the detrimental effects on picophytoplankton is unlikely from changes in carbonate chemistry because no such adverse effects were found in NaOH-OAE where the changes in carbonate chemistry were somewhat greater (Fig. 2a, b). Instead, olivine-OAE coincided with the release of potentially harmful trace metals (Supplementary Fig. 2). While previous experiments with a range of phytoplankton suggest limited harm by increasing dissolved Ni, Mn and Co concentrations, which were higher than in our study48,49,50,51,52,53, Cu can be toxic to picoeukaryotes and cyanobacteria even at <10 nmol L−140,54,55,56. Additionally, the abundance of olivine particles, which were considerably higher than in the slag treatment, may have caused physical disturbance to phytoplankton by potentially interacting with them. Indeed, olivine particles visually increased turbidity in the incubation bottles throughout the 48 h experimental incubations.

As for the other OAE approaches discussed above, the impact of olivine-OAE on the phytoplankton community must be compared to its theoretical CDR potential. Prochlorococcus, Synechococcus, and picoeukaryotes are important organisms in the marine food web in the tropical and subtropical ocean57,58,59. For example, in subtropical gyre regions Prochlorococcus, Synechococcus, and picoeukaryotes can be responsible for 50–90%, 6–12%, and >80% of the net primary production respectively59. The pronounced adverse effect of olivine on these critically important organisms and the associated shifts in the community may be considered a risk to (sub)tropical ecosystems that do not justify the relatively limited CDR achievable with open ocean olivine applications.

Conclusions

This study investigated environmental side-effects of three widely considered OAE sources across the Equatorial Pacific Ocean. While the experiments have limitations (48-hour duration of incubations, no consideration of higher trophic levels), they constitute a step forward in our ability to assess the sustainability of different OAE source materials. Most importantly, we observed pronounced differences in the efficiency and environmental side-effects of realistic additions of OAE (i.e., alkalinity increase 16–29 μmol kg−1). NaOH-OAE had the least environmental effect of the three substances tested despite the largest degree of alkalinity enhancement (Fig. 2), pointing towards its sustainability for applications in the Equatorial Pacific. However, the production of NaOH requires considerable renewable energy and forms equimolar amounts of strong acids so that its use is associated with other sustainability concerns that can affect other ecosystems12. When assuming a sequestration efficiency of 0.84 mol CO2 per mol alkalinity60, 1 mmol of NaOH enables 0.037 g CO2 removal potential. Slag-OAE and olivine-OAE delivered 8 and 0.06 mmol alkalinity g−1, respectively equivalent to 0.3 and 0.002 g CO2 removal potential g−1 60. Thus, slag-OAE had a 130 times higher CDR potential than olivine-OAE, while still being associated with lower impacts on plankton communities (Fig. 3b). This raises the question if olivine-OAE could become suitable for open ocean applications or if it is reasonable to shift focus towards the study of other alkaline materials in the pelagic realm. However, we only tested slag from Whyalla (Australia) and olivine from Mortlake (Australia) and olivine/slag from elsewhere could have different efficiencies and environmental effects.

Overall, our study demonstrated highly substrate-dependent environmental effects of OAE. Thus, a major challenge is the increasing number of OAE methods under consideration12, each with particularities that could uniquely influence their sustainability. The environmental assessment must therefore be informed by progress in OAE methodology to be able to focus the limited resources on methods with a plausible chance to succeed. As such, our study constitutes a step forward in our ability to clearly identify sustainable OAE methods for the application in the open equatorial ocean.

Methods

Incubation experiments setup

Nineteen incubation experiments were undertaken to assess the impacts of NaOH- olivine- and slag-OAE on phytoplankton growth and community composition. For each experiment, twelve acid-washed 500 mL polycarbonate bottles (Nalgene) were filled with surface seawater collected with a trace metal clean towed water sampling device (so called ‘tow-fish’) after sunset at ~2 m depth. The collection of seawater was conducted in a trace metal-clean plastic tent (the ‘bubble’) that was over-pressurised with HEPA-filtered air to minimize trace metal contamination. Three bottles were left unperturbed and sampled immediately to determine the initial conditions (see below). Three bottles were supplemented with 150 µL of 0.1 M NaOH (Analytical grade); three with 0.2 g of ground olivine powder; three with 0.001 g of slag powder; and three remained unperturbed as control. Both mineral powders are sieved to a size smaller than 44 µm before the cruise. These bottles were incubated for 48 h in an on-deck incubator flushed continuously with surface seawater and screened to receive ca. 35% of surface incident light61.

Sampling protocol

Initial seawater was stored in dark HDPE bottles before measurements. The pHT was measured using a pH metre (914 pH/Conductometer Metrohm, ±0.003 accuracy), following the procedural ref. 28. Eight mL of sample was filtered (0.2 µm) for macronutrient analysis using a QUAATRO39 (Seal Analytical) autoanalyzer directly after sampling. Alkalinity samples (60 mL) of the control and the NaOH treatment were fixed with 30 µL HgCl2 and stored for 3 months until analysis62. Alkalinity samples of the olivine and slag treatments were filtered after sampling (0.22 µm PES syringe filters) to remove remaining particles. In Experiments 3,8 and 9, certain replicate bottles from both the treatment and control groups exhibited lower alkalinity, which could be due to rainwater dilution effects that may have occurred in a patchy manner during seawater collection with the tow-fish. Therefore, we compared the high and low alkalinity samples in the treatment group with the corresponding high and low alkalinity samples in the control group to determine the ∆ alkalinity values in these specific experiments.

After 48 h, experimental bottles were removed from incubators, samples were transferred into dark bottles in the ‘bubble’. Like the initial samples, the following samples were subsampled from the dark bottles from each treatment: pHT, flow cytometry (2 mL for phytoplankton and 1 mL for bacteria samples), Chl-a (100 mL), FRRf (5 mL), and total alkalinity (60 mL). Nutrient concentrations of treatment bottles were analysed for six experiments throughout the voyage using a QUAATRO39 (Seal Analytical) autoanalyzer.

Flow cytometry

For phytoplankton flow cytometry samples, 2 mL of seawater was sampled with a pipette and fixed with paraformaldehyde to a final concentration of 1%. For heterotrophic bacteria, 1 mL of seawater was fixed with glutaraldehyde to a final concentration of 0.5%. Flow cytometry samples were mixed gently and kept at 4 °C in the dark for 15–25 min and then stored at −80 °C until analysis. Bacterial DNA was stained with SYBR Green I (diluted in dimethylsulphoxide) and added to samples in a final ratio of 1:10 000 (SYBR Green I: sample) prior to analysis. A Cytek Aurora flow cytometer (Cytek Biosciences) was used to quantify the abundance of phytoplankton and heterotrophic bacteria. Phytoplankton groups were distinguished based on their auto-fluorescence signal intensity of different laser excitation/emission wavelength combinations and forward scatter (FSC). The yellow-green laser (centre wavelength: 577 nm), in combination with FSC signal strength, was used to separate Synechococcus from other phytoplankton. The violet laser (centre wavelength: 692 nm) in combination with FSC was used to distinguish Prochlorococcus, picoeukaryotes, nanoeukaryotes, and microeukaryotes. The blue laser (centre wavelength: 525 nm) in combination with FSC was used to distinguish heterotrophic bacteria from other living (i.e., DNA-containing) particles (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Total chlorophyll a and Fv/Fm measurement

For Chl-a, 100 mL of seawater was filtered through glass fibre filters (Whatman GF/F, pore size 0.7 µm, diameter 25 mm) and then stored in 2 mL cryovials at −80 °C. The Chl-a was measured on a calibrated Turner Designs trilogy fluorometer. Samples for Fast Repetition Rate fluorometry (FRRf; FastOcean Sensor FRRf3, Chelsea Technologies) were dark-acclimated for more than 30 min and measured within 1.5 h. They were measured using 450 nm excitation light. Filtered (0.2 µm) natural seawater was used as a blank. Fluorescence transients were fit using FASTPro8 software (Chelsea Technologies) for determination of minimum and maximum fluorescence (Fo and Fm respectively). Blank fluorescence was subtracted from Fo and Fm before calculation of Fv/Fm = (Fm-Fo)/Fm.

Trace metal measurement

Dissolution experiments were conducted on land to estimate the trace metals leached from added minerals. Twelve acid-washed 500 mL polycarbonate bottles were filled with filtered artificial seawater. The artificial seawater was made using the Aquil major salt recipe without adding any macro nutrients or trace metals, and the artificial seawater was passed through a Chelex column to further reduce potential trace metal concentrations. Three bottles received no amendment, and the remaining bottles were supplemented with NaOH, olivine powder, and slag powder in triplicate using the same concentrations as the incubation experiments. After 48 h, under room temperature, the seawater from each bottle was filtered (0.2 µm acid-washed PES syringe filters) using acid-washed silicone tubing and a peristaltic pump. Sixty mL of filtered seawater was stored in acid-washed LDPE bottles and acidified with ultrapure HCl acid (final concentration of 1%). Samples were diluted 20 times with ultrapure HNO3 (0.01 M) and analysed using sector field ICP-MS using increased spectral resolution, with quantification via comparison to external standards. The measured values from the treatments were compared with the control to compute the change in dissolved metal concentrations due to individual treatments (Supplementary Fig. 2), and values below the measurable blank levels were replaced with 0.

Data analysis

The net change (∆) of biological variables (Chl-a, Fv/Fm) or chemical variables (pHT, alkalinity, trace metal concentrations etc.) was calculated as:

where Value c represents the control level, and Value t represents the treatment level.

The relative change of each plankton group abundance as well as Fv/Fm and Chl-a were calculated using the equation:

where Value t represents the cell count (or Fv/Fm and Chl-a) of the plankton from the treatment, and Value c represents the cell count (or Fv/Fm and Chl-a) of the control. The data were used to analyse the relationship between plankton physiological performance change, ambient chemical environment and treatments. Multivariate linear regression models were used with the formula:

Here, TA refers to the initial alkalinity (µmol kg−1), TON and Si refers to the initial NOx− and Si(OH)4 concentrations (µmol L−1), and T and pH refers to the initial temperature (°C) and pHT (initial meaning values before perturbation); ∆TA is the change of alkalinity in each experiment between treatment and the control. The concentration of PO43− is not included in the model because PO43− has strong linear relationship with NOx-, which would affect linear model results due to redundant information. All independent variable data were ln-transformed before fitting into the model. If the p-value from an environmental variable is <0.05, it means that the predictor variable significantly affects the treatment effect. The coefficient represents the relationship between the predictor variable and response variable. Please note that if both response variable and the coefficient are negative then the response variable enhances the treatment’s negative effect. Data analysis was conducted in R studio (R version 4.3.3)63.

Data availability

The research data are stored at IMAS Data portal (doi:10.25959/BMV8-1K07). The supplementary data are stored at figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28578467.v1).

References

IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2022).

Burt, D. J., Fröb, F. & Ilyina, T. The sensitivity of the marine carbonate system to regional ocean alkalinity enhancement. Front. Clim. 3, 624075 (2021).

Nemet, G., Greene, J., Müller-Hansen, F. & Minx, J. C. Dataset on the adoption of historical technologies informs the scale-up of emerging carbon dioxide removal measures. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 397 (2023).

Nemet, G. F. et al. Negative emissions—Part 3: innovation and upscaling. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 063003 (2018).

Middelburg, J. J., Soetaert, K. & Hagens, M. Ocean alkalinity, buffering and biogeochemical processes. Rev. Geophys. 58, e2019RG000681 (2020).

Lenton, A., Matear, R. J., Keller, D. P., Scott, V. & Vaughan, N. E. Assessing carbon dioxide removal through global and regional ocean alkalinization under high and low emission pathways. Earth Syst. Dyn. 9, 339–357 (2018).

Renforth, P. & Henderson, G. Assessing ocean alkalinity for carbon sequestration. Rev. Geophys. 55, 636–674 (2017).

Montserrat, F. et al. Olivine dissolution in seawater: implications for CO2 sequestration through enhanced weathering in coastal environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 3960–3972 (2017).

Caserini, S., Storni, N. & Grosso, M. The availability of limestone and other raw materials for ocean alkalinity enhancement. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 36, e2021GB007246 (2022).

Renforth, P. The negative emission potential of alkaline materials. Nat. Commun. 10, 140 (2019).

House, K. Z., House, C. H., Schrag, D. P. & Aziz, M. J. Electrochemical acceleration of chemical weathering as an energetically feasible approach to mitigating anthropogenic climate change. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 8464–8470 (2007).

Eisaman, M. D. et al. Assessing the technical aspects of ocean-alkalinity-enhancement approaches. State Planet 2-oae2023, 1–29 (2023).

Bach, L. T. et al. The influence of plankton community structure on sinking velocity and remineralization rate of marine aggregates. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 33, 971–994 (2019).

Guo, J. A., Strzepek, R. F., Swadling, K. M., Townsend, A. T. & Bach, L. T. Influence of ocean alkalinity enhancement with olivine or steel slag on a coastal plankton community in Tasmania. Biogeosciences 21, 2335–2354 (2024).

Sunda W. G. Trace metal-phytoplankton interactions in aquatic systems. In: Environmental Microbe-Metal Interactions (ed. Lovley D. R.) (2000).

Sunda, W. G. Feedback interactions between trace metal nutrients and phytoplankton in the ocean. Front. Microbiol. 3, 1–22 (2012).

He, J. & Tyka, M. D. Limits and CO2 equilibration of near-coast alkalinity enhancement. Biogeosciences 20, 27–43 (2023).

Moras, C. A., Bach, L. T., Cyronak, T., Joannes-Boyau, R. & Schulz, K. G. Ocean alkalinity enhancement—avoiding runaway CaCO3 precipitation during quick and hydrated lime dissolution. Biogeosciences 19, 3537–3557 (2022).

Fuhr, M. et al. Kinetics of olivine weathering in seawater: an experimental study. Front. Clim. 4, 831587 (2022).

Bach, L. T. The additionality problem of ocean alkalinity enhancement. Biogeosciences 21, 261–277 (2024).

Webb, R. & Steenkamp, R. C. Legal considerations relevant to research on ocean alkalinity enhancement. In: Guide to Best Practices in Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement Research (ed Oschlies A., et al). Copernicus Publications (2023).

Price, N. M., Ahner, B. A. & Morel, F. M. M. The equatorial Pacific Ocean: Grazer-controlled phytoplankton populations in an iron-limited ecosystem. Limnol. Oceanogr. 39, 520–534 (1994).

Price, N. M. et al. Preparation and chemistry of the artificial algal culture medium Aquil. Biol. Oceanogr. 6, 443–461 (1989).

Moras, C. A., Joannes-Boyau, R., Bach, L. T., Cyronak, T. & Schulz, K. G. Carbon dioxide removal efficiency of iron and steel slag in seawater via ocean alkalinity enhancement. Front. Clim. 6, 1396487 (2024).

Kadar, E. et al. The influence of engineered Fe2O3 nanoparticles and soluble (FeCl3) iron on the developmental toxicity caused by CO2-induced seawater acidification. Environ. Pollut. 158, 3490–3497 (2010).

Li, S. et al. Impact of the combined effect of seawater exposure with wastewater and Fe2O3 nanoparticles on Chlorella vulgaris microalgae growth, lipid content, biochar, and bio-oil production. Environ. Res. 232, 116300 (2023).

Suggett, D. J., Moore, C. M., Hickman, A. E. & Geider, R. J. Interpretation of fast repetition rate (FRR) fluorescence: signatures of phytoplankton community structure versus physiological state. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 376, 1–19 (2009).

Ferderer, A., Chase, Z., Kennedy, F., Schulz, K. G. & Bach, L. T. Assessing the influence of ocean alkalinity enhancement on a coastal phytoplankton community. Biogeosciences 19, 5375–5399 (2022).

Subhas, A. V. et al. Microbial ecosystem responses to alkalinity enhancement in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre. Front. Clim. 4, 784997 (2022).

Paul, A. J. et al. Ocean alkalinity enhancement in an open ocean ecosystem: Biogeochemical responses and carbon storage durability. Preprint at https://egusphere.copernicus.org/preprints/2024/egusphere-2024-417/ (2024).

Ferderer, A. et al. Investigating the effect of silicate- and calcium-based ocean alkalinity enhancement on diatom silicification. Biogeosciences 21, 2777–2794 (2024).

González-Santana, D. et al. Ocean alkalinity enhancement using sodium carbonate salts does not lead to measurable changes in Fe dynamics in a mesocosm experiment. Biogeosciences 21, 2705–2715 (2024).

Gately, J. A., Kim, S. M., Jin, B., Brzezinski, M. A. & Iglesias-Rodriguez, M. D. Coccolithophores and diatoms resilient to ocean alkalinity enhancement: A glimpse of hope? Sci. Adv. 9, eadg6066 (2023).

Faucher, G., Haunost, M., Paul, A. J., Tietz, A. U. C. & Riebesell, U. Growth response of Emiliania huxleyi to ocean alkalinity enhancement. Biogeosciences 22, 405–415 (2025).

Sunda, W. G. Trace metal interactions with marine phytoplankton. Biol. Oceanogr. 6, 411–442 (1989).

Kolber, Z. S. et al. Iron limitation of phytoplankton photosynthesis in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Nature 371, 145–149 (1994).

De Baar, H. J. et al. Synthesis of iron fertilization experiments: from the iron age in the age of enlightenment. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 110, (2005).

Browning, T. J. et al. Persistent equatorial Pacific iron limitation under ENSO forcing. Nature 621, 330–335 (2023).

Partensky, F., Hess, W. R. & Vaulot, D. Prochlorococcus, a marine photosynthetic prokaryote of global significance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63, 106–127 (1999).

Mann, E. L., Ahlgren, N., Moffett, J. W. & Chisholm, S. W. Copper toxicity and cyanobacteria ecology in the Sargasso Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47, 976–988 (2002).

Hawco, N. J. & Saito, M. A. Competitive inhibition of cobalt uptake by zinc and manganese in a pacific Prochlorococcus strain: Insights into metal homeostasis in a streamlined oligotrophic cyanobacterium. Limnol. Oceanogr. 63, 2229–2249 (2018).

Cavender-Bares, K. K., Mann, E. L., Chisholm, S. W., Ondrusek, M. E. & Bidigare, R. R. Differential response of equatorial Pacific phytoplankton to iron fertilization. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44, 237–246 (1999).

Bach, L. T., Vaughan, N. E., Law, C. S. & Williamson, P. Implementation of marine CO2 removal for climate mitigation: The challenges of additionality, predictability, and governability. Elem. Sci. Anth. 12, 00034 (2024).

Tagliabue, A. et al. Ocean iron fertilization may amplify climate change pressures on marine animal biomass for limited climate benefit. Glob. Chang. Biol. 29, 5250–5260 (2023).

Holzer, M. & Primeau, F. W. Global teleconnections in the oceanic phosphorus cycle: Patterns, paths, and timescales. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 118, 1775–1796 (2013).

Fripiat, F. et al. Nitrogen isotopic constraints on nutrient transport to the upper ocean. Nat. Geosci. 14, 855–861 (2021).

Strong, A. L., Cullen, J. J. & Chisholm, S. W. Ocean fertilization science, policy, and commerce. Oceanography 22, 236–261 (2009).

Ou, R. et al. Ecotoxicology of polymetallic nodule seabed mining: The effects of cobalt and nickel on phytoplankton growth and pigment concentration. Toxics 11, 1005 (2023).

Hutchins, D. A. et al. Responses of globally important phytoplankton groups to olivine dissolution products and implications for carbon dioxide removal via ocean alkalinity enhancement. Biogeosciences 20, 4669–4682 (2023).

Guo, J. A., Strzepek, R., Willis, A., Ferderer, A. & Bach, L. T. Investigating the effect of nickel concentration on phytoplankton growth to assess potential side-effects of ocean alkalinity enhancement. Biogeosciences 19, 3683–3697 (2022).

Xin, X., Faucher, G. & Riebesell, U. Phytoplankton response to increased nickel in the context of ocean alkalinity enhancement. Biogeosciences 21, 761–772 (2024).

Stuart, R. K. et al. Copper toxicity response influences mesotrophic Synechococcus community structure. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 756–769 (2017).

Sunda, W. G. & Huntsman, S. A. Interactive effects of external manganese, the toxic metals copper and zinc, and light incontrolling cellular manganese and growth in a coastal diatom. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 1467–1475 (1998).

Stuart, R. K., Dupont, C. L., Johnson, D. A., Paulsen, I. T. & Palenik, B. Coastal strains of marine Synechococcus species exhibit increased tolerance to copper shock and a distinctive transcriptional response relative to those of open-ocean strains. Appl Environ. Microbiol 75, 5047–5057 (2009).

Paytan, A. et al. Toxicity of atmospheric aerosols on marine phytoplankton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 4601–4605 (2009).

Debelius, B., Forja, J. M., Delvalls, T. A. & Lubián, L. M. Toxicity of copper in natural marine picoplankton populations. Ecotoxicology 18, 1095–1103 (2009).

Visintini, N., Martiny, A. C. & Flombaum, P. Prochlorococcus, Synechococcus, and picoeukaryotic phytoplankton abundances in the global ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 6, 207–215 (2021).

Uitz, J., Claustre, H., Gentili, B. & Stramski, D. Phytoplankton class-specific primary production in the world’s oceans: Seasonal and interannual variability from satellite observations. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 24, GB3016 (2010).

Letscher, R. T., Moore, J. K., Martiny, A. C. & Lomas, M. W. Biodiversity and stoichiometric plasticity increase pico-phytoplankton contributions to marine net primary productivity and the biological pump. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 37, e2023GB007756 (2023).

Schulz, K. G., Bach, L. T. & Dickson, A. G. Seawater carbonate chemistry considerations for ocean alkalinity enhancement research: theory, measurements, and calculations. State Planet 2-oae2023, (2023).

Browning, T. J. et al. Nutrient co-limitation at the boundary of an oceanic gyre. Nature 551, 242–246 (2017).

Dickson, A. G., Sabine, C. L. & Christian, J. R. Guide to best practices for ocean CO2 measurements. (North Pacific Marine Science Organization, 2007).

R Core Team R. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (2013).

NASA GES DISC. Aqua MODIS Global Mapped Chlorophyll (CHL) Data, version R2022.0. Data centers: NASA/GSFC/SED/ESD/GCDC/OB.DAAC, Access date: 2024/3/7 https://doi.org/10.5067/AQUA/MODIS/L3M/CHL/2022 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. V. Orsouw from Moyne Shire Council, Victoria, Australia for providing olivine rocks and B. Mansell who provided the Basic Oxygen Slag from Liberty Primary Steel Whyalla Steelworks in Whyalla, South Australia, Australia. We also thank E. M. O’Sullivan and Z. Steiner for their support with element measurement and B. Robinson and Z. Chen for their general support on the cruise. We also thank NASA GES DISC for providing satellite-derived Chl-a data through the Giovanni online data system. This research has been supported by the Australian Research Council through a Future Fellowship project (FT200100846 to L. T. Bach), the Carbon to Sea Initiative (L. T. Bach), and by the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership (ASCI000002 to R. F. Strzepek, K. M. Swadling and J. A. Guo). Access to ICP-MS instrumentation was facilitated through Australian Research Council LIEF program (LE0989539). J. A. Guo thanks the Australian Research Training Program (RTP) for her scholarship. The research cruise was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; 03G0298A, ‘GEOTRACES GP11’). We thank the captain and crew of R/V Sonne for their excellent support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.T.B., T.J.B., R.F.S., and J.A.G. developed the idea and designed the experiments. J.A.G. conducted the experiments. L.T.B, T.J.B., R.F.S., K.M.S., Z.Y., T.J.B. and E.P.A. supervised the study. A.T.T. analysed the dissolved trace metal samples. J.A.G. conducted the statistical analysis and produced figures. All authors provided critical comments on previous versions of the manuscript and contributed to writing the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Librada Ramírez and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Dania Albini and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, J.A., Strzepek, R.F., Yuan, Z. et al. Effects of ocean alkalinity enhancement on plankton in the Equatorial Pacific. Commun Earth Environ 6, 270 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02248-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02248-7

This article is cited by

-

Alkalinity enhancement with sodium hydroxide in coastal ocean waters

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Three ways to cool Earth by pulling carbon from the sky

Nature (2025)

-

Increasing alkalinity to mitigate biogenic acidification and its negative effects during the North–south-relay transportation of abalone

Aquaculture International (2025)