Abstract

Quantifying the ocean’s ability to sequester atmospheric carbon is essential in a climate change context. Measurements of gravitational carbon export to the mesopelagic seldom balance the carbon demand or the oxygen consumption there, suggesting the potential presence of other mechanisms of carbon export. We deployed a biogeochemical Argo float in a cyclone in the Benguela upwelling system for five months, and estimated vertical carbon export and respiration in the eddy via particle imagery with an underwater vision profiler 6 in a quasi Lagrangian way. A sensitivity analysis shows that, under certain assumptions, oxygen consumption rates could match the carbon supply and carbon demand. We furthermore identified a mechanism of vertical particulate carbon export, the full eddy core submergence pump. Our analysis suggests that at 450 m depth, within this eddy, this pump exports about one fourth to half of the total carbon compared to the biological gravitational pump.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the main marine processes important for climate regulation is the so-called “biological carbon pump” (BCP,1). This comprises a suite of processes that starts with the uptake of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere via mixing and diffusion. In the sunlit surface layer of the ocean (generally referred to as epipelagic, ~0–200 m), CO2 is then converted into particulate organic carbon (POC) through primary productivity. A fraction of this organic carbon is eventually exported from the epipelagic to the deep sea2, where it sustains deep-sea life3,4. The passive sinking of particles (e.g., aggregates of decaying phytoplankton and feces), also known as the biological gravitational pump (BGP), is the major contributor to the BCP5. Also biologically or physically mediated processes (such as subduction), can contribute significantly to carbon export5. Understanding the different mechanisms driving the BCP is of crucial importance for global climate dynamics—as CO2 is a global heat regulator—as well as for ecosystem services6.

One of the main issues in the study of the BCP is that the estimated supply of organic carbon to the mesopelagic (~200–1000 m) is often found to be lower than the metabolic demand of mid-water life there7. Only a few studies were able to reconcile this mismatch, by considering the role of prokaryotes in carbon demand estimates8, or particle fragmentation in the carbon supply calculation9. In this context, aerobic respiration results in the consumption of organic carbon and oxygen. Hence, carbon supply, carbon demand, and oxygen consumption are fundamentally linked. However, oxygen consumption rate observations were seldom used to constrain the carbon budget. This is because they are difficult to measure in the mesopelagial, due to the long observational periods needed to measure the relatively small changes in oxygen concentrations there (~10 μmol/kg/yr10).

Another important difficulty to consider when studying the multi-faceted processes of the BCP is that, in the ocean, everything is constantly in motion, and a water parcel that hosts a process is transported by currents. Consequently, an observer has to move with the current in a so called Lagrangian framework, opposed to the fixed Eulerian point of view that is generally the reference framework adopted by most oceanographic studies.

In the ever-moving oceanic seascape, mesoscale eddies, with tens to hundreds of kilometers of diameter and lifetimes spanning from several weeks to months, play a pivotal role in ocean dynamics. The upwelling and downwelling movements of water masses associated with eddies11 create significant heterogeneity in biogeochemical properties (e.g., fostering or hampering primary productivity12,13,14). Their importance is such that the downward export of carbon particles due to circulation at the fronts of these structures15,16,17 has been identified as one of the main mechanisms being part of the BCP1,5. This process has been referred to as “eddy subduction pump”. On the other hand, subduction of entire eddies contributes to the downward transport of properties such as heat (e.g., refs. 18,19), but its impact on biogeochemical properties could not be assessed to date. Notably, eddies can isolate the waters they carry from the surrounding environment, which makes them ideal candidates to study a water parcel and its biogeochemical processes over long time periods in a Lagrangian fashion.

Satellite remote sensing has proved to be an efficient tool to track upper ocean eddies20,21,22 and to study their impact on biogeochemical processes23,24. Yet, remote sensing does not provide much information on the vertical structure of eddies, for which concomitant in situ observations are required. The Argo international program (https://argo.ucsd.edu) provides unprecedented in situ coverage through a global fleet of BGC Argo floats, which measure multiple biogeochemical properties along the water column25. This resulted in a detailed biogeochemical description of eddies (e.g., 26,27,28). The monitoring capacity of BGC Argo floats has been recently improved by the addition of the Underwater Vision Profiler 6 (UVP6,29). This camera system is designed to size and count particles (between 0.102–16.40 mm), and it can provide essential information to study the BCP (e.g., particle size distribution, estimates of carbon flux, or remineralisation rates30). To date, BGC Argo floats enabled detailed studies of multiple eddies (e.g., 26,27,28), but were not equipped with a UVP6, nor used to analyze a specific structure over long time periods in a Lagrangian way.

In the present work, we focused on the Southern Benguela upwelling system, well known for its strong eddy activity. Eddies, mainly stemming from the plateau31, trap nutrient-rich upwelled waters which impact the biogeochemical properties of the South Atlantic critically32,33. Furthermore, numerous subsurface-intensified eddies have been described in this region34,35.

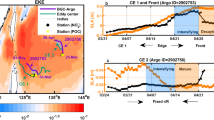

Therefore, in this work we deployed a BGC Argo/ UVP6 float in a cyclonic eddy in the Southern Benguela upwelling system (Fig. 1). We chose a profiling strategy that kept the float in the eddy for five months. The BGC Argo/ UVP6 float was equipped with temperature, salinity, pressure, chlorophyll a, dissolved oxygen, and particulate backscattering coefficient (bbp). Its observations were combined with several satellite data products. In the following we (i) provide a high-resolution Lagrangian description of the physical and biogeochemical dynamics of the eddy, including the carbon demand, carbon supply, and oxygen consumption within the eddy; and (ii) quantify carbon export associated with the full eddy submergence pump, a mechanism that should be considered in descriptions of the biological pump.

The gray-edged filled circles represent the trajectory of the cyclone (Eddy 1) in which the BGC Argo float was trapped. These are shown once every four days. This eddy merged with a cyclone (Eddy 2; trajectory indicated by gold-edged filled circles) between 1 and 11 August 2021. The merging region is indicated by a black dashed contour centered at ~7°E, 35°S. The color of each circle is proportional to the eddy chlorophyll a anomaly (blue and red scale at right). Four eddy contours are represented as solid lines for Eddy 1 and five for Eddy 2, colored proportionally to the mean chlorophyll a inside them (green scale at right). Each eddy contour is linked to its corresponding center by a solid gray line. The red crosses represent the BGC Argo profiles which were excluded from our analyses.

Results

Initial characterization and dynamics of the eddy derived from satellite fields

Eddy network of the sampled cyclone

The targeted eddy (hereafter Eddy 1) formed on 18 October 2020 at 33.4°S, 16.9°E, 120 km off Cape Columbine (South Africa; Fig. 1). It drifted westward at 4.8 ± 5.6 km/day (weekly average, Methods) as an isolated structure with an eddy radius of 62 ± 19 km and a tangential velocity (hereafter velocity, Methods) of 0.52 ± 0.15 m s−1.

A second eddy (hereafter Eddy 2; Fig. 1) was initially detected on 18 September 2020 at 32.6°S, 16.1°E. Once formed, it started a westward drift before veering south-eastward, traveling as an isolated structure for nearly 11 months at 5.3 ± 4.8 km/day, with stable radius and velocity (53 ± 11 km and 0.44 ± 0.06 m/s, respectively).

Eddies 1 and 2 merged between 1–11 August 2021 (Supplementary Note 1.1.3 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The resulting merged eddy (hereafter Eddy1+2) continued to move south-westward and disappeared from the altimetry fields on the 27 September 2021.

Compared to the average characteristics of the cyclones originating in the same region (radius: 63 ± 22 km; velocity: 0.30 ± 0.19 m s−1,35), Eddy 1, Eddy 2, and Eddy1+2 had similar sizes, but velocities at least 1.5-times higher, suggesting that these eddies were very intense (Rossby number larger than 0.15). Further, their velocity was about 10 times larger than their translation speed. These kinematic properties suggest that these structures were coherent and able to trap water masses and particles in their core(21,36; see also Supplementary Note 1.1.2).

Float history

The BGC Argo float was deployed on 13 April 2021 close to the center of Eddy 1 at 33.07°S, 13.89°E. At this time, the eddy radius and velocity were 43 ± 2 km and 0.55 ± 0.03 m/s (results from satellite data, corroborated by ADCP data analysis, see Supplementary Fig. 2). ADCP data analysis indicates that the eddy structure extended from the surface down to 700 m depth. The parking depth of the float was hence kept at 300 m depth, and the profiling depth was first kept at 600 m depth and later extended to 1000 m depth (Methods). The float remained within a distance from the eddy center of Eddy 1 and Eddy1+2 of about half the eddy radius (~23.4 km; Fig. 2a).

a Time series of the eddy radius (blue solid line) and the distance of the float from the eddy center (black stars). b–d Conservative temperature (b), dissolved oxygen (c), and chlorophyll a (d) as a function of time and depth. e Time series of the average POC (calculated as the sum of the particulate backscattering bbp, MiP, and MaP POC) integrated between the surface and the mixed layer depth, shown as a red solid line. The average POC in the eddy core (comprised between the 1026.821027.24 kg/m3 isopycnals, white dashed lines in (b)) is shown as a magenta solid line. The latter is ten-fold magnified to improve visibility. Uncertainties (standard deviation) are reported as shadowed regions. f–h: bbp (f), MiP (g), and MaP (h) POC as a function of time and depth. The vertical dashed lines (colored in black in a and e, in white in b–d and f–h) indicate, respectively, the beginning and the end of the merging event between Eddy 1 and Eddy 2. The mixed layer and Sverdrup critical depths are shown as white solid lines in b and d, respectively. Note that in b, the temperature is reported down to 700 m to show the eddy core.

The float drifted away from the cyclone on the 23 September 2021. It likely recorded the end of the lifetime of Eddy1+2, as the eddy disappeared from satellite altimetry maps only 4 days later.

Detailed eddy analysis based on float data

Mixed layer depth, temperature, and oxygen

The mixed layer depth (MLD; “Methods”) was at about 65 m at the beginning of the float deployment. It then deepened during the Austral Winter to a maximum of about 181 m on the 13 August just after the merging of the two eddies (Fig. 2b). Subsequently, it shoaled to ~ 106 m when the float left the eddy.

Below the ML, anomalies of conservative temperature (hereafter temperature), salinity, and density, indicate that Eddy 1 may be a subsurface-intensified cyclone (Supplementary Fig. 3 and 4). For instance, the eddy core was associated with a strong temperature anomaly of -3.70° (ref. 35; Supplementary Note 1.1.2; Supplementary Fig. 4).

Interestingly, isopycnals below the ML deepened over time (Supplementary Fig. 5), as well as the salinity anomaly (Supplementary Fig. 3). The depth associated with the strongest negative anomaly of temperature (-5.42°) steadily decreased from ~ 290 to ~ 370 m between the 13 April and the 23 September 2021. These changes suggest that Eddy 1 submerged over time.(Supplementary Note 1.1.2).

Therefore, in order to follow the time evolution of water parcels sampled by the BGC Argo float, in the following we will analyze water layers comprised between two isopycnals rather than two isodepths. Hence, the eddy core is defined as the layer between the 1026.82–1027.24 kg/m3 isopycnals (corresponding to an average depth of ~ 200–600 m).

From 1 August 2021 onward, temperature and oxygen along the isodepths became relatively stable, the temperature-salinity profile changed (Fig. 2b, c, Supplementary Fig. 6, and Supplementary Note 1.1.3), and the isopycnals flattened (Supplementary Fig. 3 and 5). As this period corresponds to the merging of eddies 1 and 2, identified from the altimetry fields, these changes are most likely the result of this eddy-eddy interaction that significantly modified the eddy structure and its evolution.

Chlorophyll a and Sverdrup critical depth

The Sverdrup critical depth (Svcd) is the depth at which the integrated primary productivity and the algal respiration balance each other (ref. 37; “Satellite data”). Suitable conditions for phytoplankton growth exist when the critical depth is deeper than the mixed layer depth, and vice versa. In general, the Svcd followed the seasonal trend of surface irradiance, becoming shallower until July 2021 (austral Winter) and then deepening again (Fig. 2d). The Svcd was deeper than the ML from mid April to early May, then both were similar until early June, when the Svcd became shallower than the ML. Both depths were similar again in September 2021. Phytoplankton concentrations, as indicated by Chl a, were relatively high until mid May and then declined. This could be due to the shallowing of the Svcd and a dilution effect resulting from the deepening of the ML. Please note that the uncertainty of the Svcd is high, making it difficult to reject or confirm this hypothesis (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Particle stocks within the mixed layer and the eddy core

The average POC content is calculated using a particulate backscatter bbp to carbon38 and a UVP particle size to carbon relationship (Methods and ref. 39; UVP particle size considered: 0.102–16.40 mm equivalent spherical diameter). Hence, it is the sum of three components: bbp (with an assumed size between 0.001–0.025 mm40), micrometric particles (MiP, 0.102–0.5 mm), and macroscopic particles (MaP, 0.5–16.4 mm). During the float deployment, the POC was dominated by bbpPOC, both in the mixed layer (97.9% of the stock) and eddy core (86.9%), followed by MiP (1.8% and 12.2%, resp.) and MaP (0.3% and 0.9%, resp.; Supplementary Fig. 8). After the 1 August, the bbp POC in the mixed layer decreased, while the MiP POC increased in the eddy core (Fig. 2f, g, Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10), both changes likely results of the eddy merging event.

A layer of elevated MiP POC concentration was visible between 350–500 m from the float release until mid June (0.93 mgC/m3; Fig. 2g). The MiP POC concentration then gradually decreased to 0.31 mgC/m3 on the 26 June, and increased in August (prior, during, and after the eddy merging event) up to 0.77 mgC/m3.

Less than 20% of MaP particles were zooplankton (19 ± 13%,41). It is not possible to identify zooplankton for particles smaller than 0.5 mm. However, as the proportion of living organisms compared to the total number of particles was in other cases found to even be lower than 10%42, the contribution of zooplankton to the carbon budget must be rather negligible.

Carbon flux dynamics

POC flux is estimated by integrating the POC fluxes of each size class between 0.102–16.40 mm. The latter are obtained assuming the POC concentration and the sinking speed of each size class (Methods). The size–sinking speed and size–carbon relationships proposed by Kriest et al.39 (ref. 9 in their Table 2 and ref. 2a in their Table 1, respectively) are used as it was shown to be one of the most reliable when compared to in situ data43,44,45. bbp particles are considered as suspended, hence not contributing to the POC flux.

The presence of a layer of increased POC flux in the eddy core is visible when the float was released (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 10f, 11.40 mgC m−2 d−1), in correspondence with the pattern of high MiP POC concentrations (Subsec. “Detailed eddy analysis based on float data”). Then, the flux gradually decreased until 23 July (3.27 mgC m−2 d−1). During this period, the POC flux at the lower boundary of the eddy core was larger than the POC flux at the upper boundary (6.63 vs 3.82 mgC m−2 d−1, respectively; Fig. 3a). The situation reversed from the 26 to the 8 September, when a flux event reached the eddy core (average of 8.35 mgC m−2 d−1 at the upper boundary of the eddy core). This flux event may have been triggered by the shallowing of the Sverdrup layer (Supplementary Note 1.1.4). MiP mainly contributed to the POC flux both at the upper boundary of the eddy core (71% of the total POC flux) and at its lower boundary (87%).

a Time series of POC flux estimates along the mixed layer depth (magenta solid line) and along the upper and lower boundary of the eddy core (1026.82 and 1027.24 kg/m3 isopycnals) as red and blue solid lines, respectively. b POC flux estimate as a function of time and depth. In both panels, the vertical dashed lines indicate, respectively, the beginning and the end of the merging event between Eddy 1 and 2.

Notably, the flux values estimated in the present study are in the same order of magnitude of independent flux observations carried out in the same region and do not change substantially when using a different approach46 to calculate POC flux (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Mesopelagic carbon supply and oxygen demand prior to eddy merging

Here, we analyze the carbon and oxygen dynamics between the mixed layer depth down to the lower boundary of the eddy core. We only consider the time window prior to the eddy merging (13 April–31 July) when the water column was relatively well isolated. The Particle-Associated Respiration Rate (PARR) for a given size class was calculated by combining the particle size, the POC content, and a specific carbon remineralization rate (krem, ref. 47 and Methods). The total PARR was obtained by integrating over the 0.102–16.40 mm size classes and adding up the contribution of PARR associated with bbpPOC (Methods). Finally, PARR is converted to carbon remineralization rates assuming a respiratory quotient of 0.89 ± 0.36 molC/molO248,49.

To calculate the bulk POC removal rate (“Methods”) we assume that we are following the same water parcel over time. The water parcel is defined as the layer between two isopycnals (hereafter isopycnal bin, Fig. 4a). The difference between the POC flux entering and the POC flux exiting this layer can be considered as the carbon flux supplied to the water parcel; the difference between the integrated POC at the beginning and at the end of the time period represents the carbon stock change in the layer. The bulk POC removal rate then is the difference between the carbon flux supply and the change in the carbon stock. We estimate, on average, a bulk POC removal rate of 0.048 ± 0.75 mgC m−3 d−1 for the eddy core between the 13 April and the 31 July (Table 1).

a box model illustrating the bulk POC removal rate calculation. Uncertainties of the parameter values used in this schema are provided in Table 1. b bulk POC removal rate (in red) calculated for different density bins between the 13 April and the 31 July 2021 (Methods). The mean depth of the isopycnal bin studied is indicated by the values within brackets on the y axis. The red shadowed area represents the uncertainty (standard deviation, Methods). The blue line shows the PARR calculated with krem = 0.013 d−1, while the blue area delimits the PARR values obtained with krem between 0.0030.031 d−147. The black line represents the oxygen consumption rate, and the shadowed gray area shows the associated uncertainty (standard deviation on the regression slope, Methods). The golden solid lines show the upper and lower limits of the eddy core, while the golden dotted line shows the mixed layer depth. c same as (b), with the difference that the bulk POC removal rate and the PARR metrics were calculated considering also extrapolated size classes between 0.0250.102 mm. According to the t test, all metrics are significantly different from 0, with the exception of the bulk POC removal rate in (c).

If the gravitational sinking was the only process occurring in the water parcel, the carbon flux supply should equal the carbon stock change. Hence, the bulk POC removal rate should be equal to zero. Here, our bulk POC removal rate differs from zero due to the respiration process which leads to the disappearance of particulate material. Thus, we can compare the bulk POC removal rates with estimates of PARR. We find that among published values, a krem of 0.013 d−1 47 yields the best match between the bulk POC removal rate (0.048 ± 0.075 mgC m−3 d−1) and PARR (0.077 ± 0.132 mgC m−3 d−1; Fig. 4b and Table 1; see also Supplementary Note 1.1.13). Both metrics are significantly different from zero (t-test). Notably, the bulk POC estimated in the present does not change substantially when using a different approach46 to calculate POC flux (Supplementary Fig. 12).

The bulk POC removal rate and the PARR can also be compared with the oxygen consumption rate, derived as the change of oxygen within an isopycnal bin. This can be converted to a carbon consumption rate using a respiratory quotient of 0.89 ± 0.36 molC/molO2 (Methods) and thereby serve as an independent metric to constrain our bulk POC removal rates and PARR (Fig. 4a). In general, bulk POC removal rate estimates and PARR were 5–7 times lower than the oxygen consumption rate (0.353 ± 0.195 mgC m−3 d−1 in the eddy core; significantly different from 0; t-test). The latter was similar to previous estimates in the mesopelagic (0.300 mgC m−3 d−110).

The bulk POC removal rate and the PARR were recalculated using in addition the particle abundance of the size classes between 0.025–0.102 mm. This was estimated by linear interpolation from the 0.102–16.4 mm particle size distribution (Methods; Supplementary Note 1.3). The use of this interpolation was confirmed by the fact that the POC extrapolated down to 0.025 mm agreed with the bbpPOC (considered as representative of particles between 0.001–0.025 mm, Supplementary Fig. 13), and as confirmed by previous studies50,51. We also stress that this extrapolation was conducted to provide a sensitivity analysis of our budget estimates with respect to the uncovered size gap, rather than to provide univocal estimates. The uncertainty of the extrapolation and associated rate estimates are high and are currently difficult to assess. Nevertheless, both metrics increased consistently (Fig. 4c and Table 1; bulk POC removal rate: 0.071 ± 0.413 mgC m−3 d−1; PARR: 0.201 ± 0.174 mgC m−3 d−1) and were not significantly different from oxygen consumption rates below 320 m (t-test, which showed also that the PARR is significantly different from 0; Supplementary Note 1.1.13). Using the extended size classes 0.025–16.40 mm, the POC flux agreement with independent flux observations also improved (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Carbon export—comparison of the gravitational and the full eddy core submergence pathway

By vertical carbon export we refer to the amount of POC which is transported below a given depth horizon in a given period of time. Some of this carbon may eventually be sequestered for long periods of time. We can estimate the mean integrated vertical carbon export of Eddy 1 (time-frame 4 April to 31 July 2021; extended size classes 0.025–16.40 mm) via biological gravitational pump (BGP) by multiplying the mean POC flux with an average eddy surface of 18928 km2 (Methods). For the eddy core we estimate a BGP of 247 ± 155 and 647 ± 377 tons C/d at 200 and 450 m depth, respectively (Fig. 5b). We can also obtain the amount of carbon exported due to the subduction of the entire Eddy 1, which we refer to as full eddy core submergence pump (FECSP, Fig. 5a, Methods). It needs to be stressed that this term stands in contrast to the eddy subduction pump, which in the literature describes the carbon export due to frontal submesoscale downwelling associated with eddy structures15. The average FECSP of the eddy core is obtained by considering Eddy 1 surface, its average subducting speed, and the POC content in the eddy. The average subduction speed of the eddy (1.1 ± 0.1 m/d) was obtained from the deepening of isopycnals with time (Methods), after verifying that the isopycnal depth did not correlate with the distance of the float to the eddy center (Supplementary Fig. 14). FECSP resulted in 109 ± 90 and 239 ± 156 tons C/d exported below 200 and 450 m, respectively (Fig. 5a, b). Both the BGP and the FECSP show local maxima at 400–500 m depth, likely due to the initial presence of the Intermediate Particle Maximum.

a Illustrative example of the full eddy core submergence pump (FECSP) process. A subducting water parcel (which can represent, e.g., Eddy 1) carries sinking POC while subducting. Hence, POC is exported below a given depth horizon due to the FECSP and the BGP. FECSP is the product of the mean POC content of the water parcel times the water parcel submergence speed. BGP can be estimated from the mean POC flux at the lower boundary of the water parcel. b Eddy POC export rate as a function of depth. POC export to depth due to FECSP (red line) is calculated from the POC content of a given isopycnal bin of 0.05 kg/m3 (defined as in Fig. 4) times its submergence speed and the mean Eddy 1 surface. POC export due to the biological carbon pump (BGP, blue line) was calculated from the POC flux estimate of particles between 0.02516.40 mm ESD (Methods, Supplementary Note 1.3) times the mean Eddy 1 surface. Shadowed regions indicate the associated uncertainties (standard deviation). The black dashed line shows the Martin curve, obtained from the BGP export at 100 m and assuming an exponent b = −0.8672. The horizontal solid golden lines indicate the limits of the eddy core, while the horizontal dashed golden line shows the mixed layer depth.

Discussion

Eddy submergence and merging

Eddy 1 underwent a progressive submergence during its westward propagation. This was particularly evident in the deepening of its core isopycnals, temperature anomaly, and oxygen profiles. While the uplifting of isopycnals is characteristic of cyclonic eddies due to their circulation patterns52, the observed deepening could alternatively be attributed to a weakening of the eddy’s circulation. However, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, the eddy did not weaken during the observation period, allowing us to reject this hypothesis. Furthermore, as the deepening of the isopycnals takes place well below the mixed layer, we exclude the possibility that this was driven by the seasonal cycle.

Eddy 1 formed in an upwelling region, thus carrying dense water. During its westward drift, it likely encountered lighter offshore waters (which is confirmed by the WOA climatological density of the region, which shows a decreasing seawater density along the eddy track when moving offshore; Supplementary Fig. 3). This is consistent with theoretical studies suggesting subduction under such conditions (e.g., 53). At the start of the float deployment, temperature, salinity, and density anomalies suggest that Eddy 1 was a subsurface cyclone. Conversely, ADCP observations indicate that Eddy 1 might have initially been a surface cyclone that subsequently subducted. Additional observations would be required to resolve this ambiguity. The submergence of both anticyclones and cyclones has been documented in previous studies18,34, including in the present region18,35,54. However, the global frequency of this process remains uncertain, despite the availability of regional-scale quantitative estimates35,54,55.

Satellite analyses of the eddy contour, combined with abrupt changes in the time series of biogeochemical parameters, indicated that Eddy 1 merged with a cyclone in August 2021. Merging occurs when two eddies with the same polarity are in close proximity56,57,58. While this process is relatively rare, it has been documented since the 1980s (e.g., 59,60). Our analysis demonstrates that both submergence and merging significantly influence the biogeochemical properties of the waters transported by eddies.

Carbon budget

In recent years, approaches have been developed to calculate PARR from UVP particle size distribution data61,62, based on laboratory measurements of individual particle respiration rates63. However, so far it was impossible to test the validity of these approaches in situ as it was not possible to measure bulk POC removal rates. We found a consistent agreement between PARR estimates and bulk POC removal rates between 110–640 m depth when using a remineralization rate of 0.013 d−1 established by47. These rates stem from measurements of individual particles collected at 36 to 500 m depth in the North Atlantic. As the authors note, this krem value is much lower than the values from63,64 or65. The ability to calculate bulk POC removal rates and PARR in the Lagrangian framework enables us to provide an independent constraint on krem for mid-water depth, as the bulk POC removal rate and PARR need to be equal when considering the same particle community in such a framework. Furthermore, larger krem values would result in a PARR greater than the oxygen consumption (Supplementary Fig. 12), which is an unlikely scenario (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 16). According to the t-test, the bulk POC removal rate is not significantly different from 0 when calculated using the extended size spectrum. However, we note that, when using a different approach to calculate POC flux46 the bulk POC removal rate does not change significantly from our estimate and, at the same time, it differs significantly from zero (Supplementary Fig. 12 and Table 1).

The mismatch of carbon supply and demand in the mesopelagic zone is a problem that has been observed for many years7, with only a few studies that were able to reconcile it8,9. For example, Giering et al.8 found agreement between POC flux and carbon demand at the PAP site. However, to our knowledge, no study was able to compare direct estimates of carbon supply and demand with estimates of in situ oxygen consumption rates, due to the difficulty to measure all processes concomitantly. The quasi-Lagrangian nature of our experiment allowed us to observe an oxygen decline over more than 3 months. Our results indicated that the oxygen consumption rate was 5–7 times larger than the bulk POC removal rate and the matching PARR. This indicates that the oxygen consumption could not be uniquely due to the respiration associated with POC particles in the size range 0.001–0.025 mm and 0.102–16.40 mm, in particular above 1027.17 kg/m3 (~500 m). When using the extrapolated 0.025–0.102 mm particle abundance to recalculate bulk POC removal rate and PARR, both metrics increased, as well as the associated uncertainties.

Zooplankton respiration and remineralisation of DOC should contribute to oxygen consumption at mesopelagic depth as well. However, recent estimates (0.01–0.03 mgC m−3 d−1 for zooplankton respiration from the tropical and subtropical Atlantic44,66; 0.04 mgC m−3 d−1 for DOC remineralisation in our study region67) indicate rather minor contributions of these processes to mid-water carbon and oxygen consumption. DOC remineralisation might still be an important contributor at shallower depth, where our extended PARR and oxygen consumption rates digress.

Our analyses showed that the Eddy 1 has strong retentive power, impeding the exchange of seawater with the exterior. It can be debated whether the horizontal transport of seawater within the eddy may have affected our estimates of the carbon budget. However, supplementary analyses show that the POC within the eddy, though displaying some intrinsic variability, is not correlated with the distance to the eddy center, nor does it show any spatial gradient (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Overall, our findings suggest that particles in the 0.025–0.102 mm size range represent a major component of the POC stock (10 times more than MiP and MaP POC together, and 1.4 times more than bbpPOC) and, at the same time, contribute consistently to explain the oxygen consumption, contrarily to what was previously assumed46. We would like to stress that we conducted the analyses of the extended size spectrum to highlight the sensitivity of our estimates to this observation gap. It can be debated if the size spectrum can be extended using a log-linear approach and the conversion of bbp to bbpPOC38 might add further uncertainty, as the bbp sensor may detect some particles larger than 0.025 mm68. This may explain the variability of POC abundance in the eddy core (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 8b). We suggest that dedicated observing systems and methodologies are pivotal to better characterize the impact of 0.025–0.102 mm particles on the biogeochemical cycles at both regional and global levels.

Carbon export via eddy submergence and the BGP

The agreement found between carbon demand, carbon supply, and oxygen consumption rates shows the robustness of our measurements and allows us to provide estimates of two different mechanisms of vertical carbon export. Large amounts of particulate carbon were exported below 450 m due to the biological gravitational pump (647 ± 377 tons C/d below 450 m) and the full eddy core submergence pump (239 ± 156 tons C/d). We note that our method allowed us to separate the contribution of these two mechanisms, thus avoiding double accounting effects which often affect biogeochemical estimates5. A sensitivity test shows that the contribution of the FECSP to the total carbon export ranges from 28 to 49% (Table 2). Whereas little is known about the frequency and speed at which entire eddies subduct, we suggest that this dynamics may represent an important mechanism for carbon sequestration still unaccounted for in global models. In this context, it would be interesting to estimate the net POC export considering the region surrounding the eddy via POC anomaly, which was not possible to measure in the present study. More generally, it would be important to compare these carbon export estimates with those of other eddies and, more generally, in the Benguela upwelling system. The relative contribution of eddy core submergence flux to gravitational flux is larger than previous estimates of submesoscale downwelling associated with eddies (also called eddy subduction in the literature) at global scales ( ~ 18%,5), and in our study region ( ~ 5%,15). The observed deepening of the isopycnals was not due to decay of the eddy. However, we suggest that the submergence of the core of cyclonic eddies due to their weakening also represents a FECSP mechanism.

It is interesting to note that the overall export rate of POC of Eddy 1 equals the daily carbon footprint of 8810 European people in 201969. Notably, the major amount of carbon subducted is found in the Intermediate Particle Maximum that was observed in the eddy core from April until July 2021 at ~ 400–500 m depth. The origin of this layer is unclear and could be due to past productivity events, diel vertical migration (which declines over time), or resuspension of material at the continental margin and consequent mesoscale offshore transport typical of upwelling systems (refs. 70,71, Supplementary Note 1.2). The advection and submergence of this layer creates an export profile that differs strongly from a Martin-curve profile72, obtained by assuming an exponential decay of carbon export with depth.

Summary

We here provide a unique Lagrangian time series of several biogeochemical variables from a cyclonic eddy observed in the Benguela region. This time series was obtained using a BGC Argo float equipped with the UVP6 sensor. Our analyses enable us to show that the submergence of an entire eddy core results in a substantial downward export of carbon. For the observed eddy, the “full eddy core submergence pump" (FECSP) accounts for about one fourth to half of the carbon export below 450 m, compared to the gravitational pump (239 ± 156 vs 647 ± 377 tons C/d, respectively).

Our estimates of the carbon budget, derived using the bulk POC removal rate, match the PARR, thereby supporting the latter approach. For the first time, we are able to constrain these metrics with an independent estimate of the remineralization rate, namely the oxygen consumption rate. We are able to reconcile these three quantities below 320 m depth when we extend the observed particle size distribution to cover the gap between UVP and bbp measurements (0.025–0.102 mm). Overall, the bulk POC removal rate and the PARR explain between 13–56% of the oxygen consumption rate in the eddy core.

Outlook

Our study focused on an exceptionally energetic eddy, raising questions about how representative the “full eddy core submergence pump" (FECSP) is at basin or global scales. Addressing this issue will require further observational and modeling efforts, as well as investigations into how much carbon is advected or subducted within intermediate particle maxima. Our results suggest that the (0.025–0.102 mm) particle size range may represent a large fraction of the carbon stock. Bridging this observational gap with a dedicated sensor system on Argo floats would provide critical insights and help reduce current uncertainties. Future studies deploying multiple autonomous assets (such as Argo floats or gliders) in the same eddy would help increase the description of its 3D structure and better characterize the role of horizontal transport in the carbon budget, even though our results suggest that these dynamics did not affect our results consistently. It would be important to extend these observations to further eddies, in particular towards less energetic ones, to investigate the frequency of the processes described in the present study. In addition, dedicated, interdisciplinary research cruises that aim to characterize the particle size distribution, size to carbon and size to sinking speed relationships, other particle characteristics (such as density), and zooplankton dynamics could yield further important new data to better constrain the FECSP and eddy dynamics in general. These would be further supported by in situ measurements of particle flux with sediment traps within cyclonic eddies in our investigation area.

Methods

Satellite data

Absolute dynamic topography (ADT) was downloaded from the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS, http://marine.copernicus.eu/). ADT is the sum of the sea level anomaly obtained from optimal interpolation of altimetric tracks and the mean dynamic topography. The daily ADT used in this study is the global DT-2018 version73,74 produced by the Data Unification and Altimeter Combination System (DUACS) using all tracks available at 0.25° spatial resolution75 as part of the CNES/SALP project and the CMEMS.

Estimations of chlorophyll a concentration in the region of interest were obtained from the Global Ocean Color product (OCEANCOLOUR_ GLO_CHL_L4_REP_OBSERVATIONS_009_082-TDS) produced by ACRI-ST. This was downloaded from CMEMS website. The spatial resolution of the product is 1/24° and the temporal resolution is one day.

Sverdrup critical depth Zc was calculated for each profile using the formulation of Kovač et al.76:

where K is the attenuation coefficient, W is the Lambert function, i.e. the solution of the generic equation xex = a, αB is the initial slope of the photosynthesis-irradiance function77, IT the total available light energy at the surface over one day, and \({L}_{T}^{B}\) the phytoplankton loss rate. As K, we used the Downwelling Diffuse Attenuation Coefficient Data at 490 nm downloaded from Nasa Ocean color website (https://oceandata.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov,78) at 8-day temporal resolution (to reduce missing data). For each profile, K was calculated as the mean attenuation coefficient in a circular neighborhood of radius 0.1°, centered on the profile location, to smooth errors79. As αB we used the mean of 25 measures obtained in our study region (0.118 ± 0.061 (mgC/mg Chl a/h)/(W/m2)77). To obtain IT we multiplied the day length at each profile location by the surface irradiance I0. The latter was the Daily Shortwave Solar Irradiance—MSG product, provided by Osi Saf consortium at 0.05° and daily temporal resolution, and downloaded from Eumetsat Data Center (https://archive.eumetsat.int). I0 was calculated for each profile location in a circular neighborhood of radius 0.1° in the same way as for K. As \({L}_{T}^{B}\), we used a value of 1.75 mgC/mg Chl a/h obtained by80.

Eddy detection

Mesoscale eddies were detected from ADT fields using the TOEddies algorithm20,22. This algorithm defines eddies as closed contours of daily ADT maps encompassing either a local maximum (anticyclones) or a local minimum (cyclones). Eddies are then tracked in time by determining overlapping contours between consecutive days22,34. By doing so, it is possible to record merging and splitting events of eddies along their trajectories, as well as the drifting velocity and the tangential velocity (the latter referred to as velocity). Subsequently, for each BGC Argo float profile, we calculated the distance between the surfacing position and the center of Eddy 1 or Eddy1+2 on the profiling day18,54.

Once the eddy centers and contours were identified, we defined the chlorophyll a anomaly as the difference between the mean chlorophyll a concentration inside the eddy and the region surrounding it. The former was extracted from the mean chlorophyll a concentration inside the eddy contour. The latter was extracted from the mean chlorophyll a concentration inside a circular neighborhood centered on the eddy center, with radius equal to ~368 km (4 times the mean radius of Eddy 1 or Eddy1+2, chosen to have a proper representation of the region in which the eddy was located), minus the region inside the eddy contour.

ADCP data

The R/V SONNE vessel, which released the BGC Argo float, was equipped with a 38 kHz Shipboard Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers. This was used to study the velocity structure of Eddy 1 when it was crossed before and after the launching of the BGC Argo (Supplementary Fig. 2). The vertical resolution was set to 32 m. We refer to the cruise report of the S0283 cruise for further details81.

ADCP analyses indicated that the eddy extended down to ~750 m as confirmed by the identification of the eddies using the method developed by ref. 82 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

BGC Argo data

The launch of the BGC Argo float into the selected cyclone was the result of an opportunity along the R/V SONNE route during the SO28 cruise81. Eddy detection, using TOEddies22, on the DT-2018 near-real-time products of ADT73 along the forecast route of the cruise was performed. Several eddies were identified as possible candidates, and the selected cyclonic eddy was chosen as it optimized the short distance of the forecast route, its interesting location in the Cape Basin, and its large signal on the altimetry fields.

To maintain the BGC Argo float within the eddy, the maximum sampling depth was alternated between 600 and 1000 m (one profile at a maximum depth of 1000 m every five profiles at a maximum depth of 600 m until July 2021; then one profile at a maximum depth of 600 m followed by one at 1000 m until September 2021). The profiling frequency was set to 4 days to provide more detailed observations, compared to traditional Argo profiling strategies (10 days). The average distance between two profiles was 34 km (ranging from 3 to 88 km). The vertical resolution increased with depth, ranging from 0.05 m at the surface to 5 m at 600 m depth (mean vertical resolution: 1.36 m).

Please note that, for the oxygen sensor, the possible presence of drift was checked by calculating the gain in the oxygen signal25. The latter was estimated by comparing the oxygen values observed by the float with the oxygen values provided by the World Ocean Atlas (WOA,83), and expressed as percentage. The gain was ≲1% for all the profiles analyzed, indicating the absence of drift in the oxygen signal.

An Underwater Vision Profiler 6 (UVP6) was mounted on the BGC Argo float. The UVP6 is a camera-based particle counter which measures particle abundance for several size classes between 0.102–16.40 mm of equivalent spherical diameter (further details in ref. 29).

Mixed layer depth was calculated as the depth at which the temperature decreased by 0.2° compared to the temperature at 10 m depth, following the definition of ref. 84.

For each Argo profile, a local climatological profile of reference temperature was created using data from the 2018 version of the WOA at monthly and 1/4° resolution. These were interpolated both in time and space at the surfacing position of each float profile, and then subtracted from the temperature measured by the float, obtaining the temperature anomaly.

Depth, mixed layer depth, conservative temperature, absolute salinity, and seawater density were calculated from the Gibbs SeaWater Oceanographic Toolbox of the Thermodynamic Equation of SeaWater85. For a given parameter, we applied, for each BGC Argo profile, a Savitzky–Golay filter (Python module scipy) to smooth the spikes while keeping signal consistency. Subsequently, we interpolated the filtered profiles in time and depth with a resolution of one day and 10 meters using the griddata function from the Python module scipy.

High-resolution full-depth particle size abundances (expressed as number of particles per liter; #/L) were obtained with the UVP629 (see above). POC concentration for a given size class was obtained by multiplying its particle abundance and the relative POC content. The latter was obtained from the empirical relationship between particle size and nitrogen content measured in ref. 39 (reference 2a in their Table 1) and assuming a carbon:nitrogen ratio of 106:16.

Micrometric particles (MiP) POC concentration was obtained by integrating the POC concentrations over all size classes between 0.102 and 0.5 mm. Macroscopic particle (MaP) POC concentration was calculated analogously using the size classes between 0.5 and 16 mm.

Particulate backscattering (bbp) was filtered in order to remove spikes likely due to large particles. To do so, we followed the methodology from9 by applying to each profile a 11-point running minimum filter followed by an 11-point running maximum filter. In this way, bbp signal was considered representative of particles between 0.001–0.025 mm40,86, and double accounting effects5 were avoided. Subsequently, bbp signal was converted to bbpPOC concentration using the relationship recently obtained by Koestner et al.38, which performs better than previous ones (e.g., ref. 87).

Average POC concentrations in the mixed layer and in the eddy core were obtained from the mean value of the sum of MiP, MaP, and bbpPOC concentrations in these layers.

POC flux for a given size class was estimated using its POC concentration and assuming the empirical relationship between particle size and sinking speed of Kriest et al.39 (ref. 9 in their Table 2). This relationship, which has been adopted in previous studies using UVP observations (e.g., ref. 88) best reproduced profiles of marine snow and particulate aggregates at the same time. In addition, it has been shown to be the best performing relationship between size and sinking speed and size and POC flux to reproduce in situ sediment trap observations in the North43 and Eastern Tropical Atlantic44. The POC flux of a given particle of equivalent spherical diameter (expressed in cm) was 1.4324 ESD 2.24 [mgC m d−1]. The POC flux of a given size class was obtained by multiplying the latter flux with the abundance of particles in that size class. Finally, the total POC flux estimate was obtained by integrating over the size classes between 0.102–16 mm. bbpPOC was considered as suspended, hence not contributing to the POC flux

POC flux, MiP, MaP, and bbpPOC were filtered and interpolated in depth and time following the same procedure described in the previous subsection for e.g. temperature or salinity.

PARR for a given size class i (PARRi) was calculated using two different functions:

-

the first function62 combined the mass Mi of a particle in the size class i, the number of particles in that size class ni, and a specific carbon remineralization rate krem using ref. 47:

$$PAR{R}_{i}\,=\,\frac{{M}_{i}\,{k}_{rem}}{{2}^{\frac{10-T}{10}}}\,{n}_{i},$$(2)where we included the temperature (T) effect by assuming a Q10 of 2, therefore dividing by 2(10−T)/10. m is calculated by multiplying the coefficient for fractal particle mass aPOC (set to 1 μgC/mm3 89) for the particle volume elevated to bPOC, the fractal exponent for particle mass (set to 0.589):

$${M}_{i}\,=\,{a}_{POC}\,{\left[\frac{4}{3}\pi {\left(\frac{ESD}{2}\right)}^{3}\right]}^{{b}_{POC}}$$(3)We used krem = 0.013 d−1, which was measured empirically by ref. 47 on marine snow aggregates in the Atlantic Ocean. To calculate the associated uncertainty, we used the krem values of 0.003 and 0.031 d−1 provided by ref. 47. Finally, a krem value of 0.1 d−1 was used as well63.

-

the second function combined the size class ESD, the POC concentration, the temperature, and the oxygen concentration, and was obtained by Kalvelage et al.61. The PARR obtained in this way gave the same results than the PARR obtained with the function of ref. 63. This because ref. 61 was based on the function from ref. 63 plus a correction for low oxygen conditions, which however did not apply in our study region (Fig. 2e).

For the bbpPOC, the PARR was calculated assuming bbp as representative of particles between 0.001–0.025 mm40,86. The abundance of particles in the bbp size class was estimated by dividing the bbpPOC by the POC content of a 0.013 mm particle. Finally, the total PARR was obtained by integrating over the size classes between 0.102–16 mm and adding up the bbp contribution.

The oxygen consumption rate as a function of the depth was calculated as follows. First, we selected a given isopycnal bin (e.g., 1026.80–1026.85 kg/m3). Then, for a given profile, we calculated the oxygen in correspondence with the selected bin as the mean of all the oxygen values measured within the bin range. This was repeated for all the profiles between the 23 April and the 31 July 2021, resulting in 41 oxygen values. These were linearly interpolated using the lin regress function from the Python module scipy, providing the oxygen consumption rate (the slope of the linear fit) with the associated uncertainty (the slope standard deviation). This was repeated for all the isopycnal bins included between 1026.325 and 1027.40 kg/m3 (bin step size of 0.05 kg/m3), providing the oxygen consumption rate at different isopycnals. The depth associated with the isopycnal bin was calculated as the mean of all the depth values measured within the isopycnal bin during the period of time considered. The choice of calculating the oxygen variation along a given isopycnal bin was to follow the same water mass over time. The oxygen consumption rate was converted to carbon consumption rate using a respiratory quotient of 0.89 ± 0.36 molC/molO2, which was obtained for planktonic material48,49.

The bulk POC removal rate in the water column between 13 April and 31 July 2021 was calculated as follows (Fig. 4a). First, we selected an isopycnal bin (e.g., 1026.30–1026.35 kg/m3). The POC budget was obtained from the difference of two terms:

-

ΔFlux: the difference between the POC flux at the upper and lower boundary of the isopycnal bin. These two terms were obtained as follows. The POC flux was filtered and interpolated versus density and time (see previous Subsection), obtaining one interpolated profile per day. For each interpolated profile, the flux at the upper boundary of the bin was calculated as the mean of the flux values comprised between 1026.275–1026.325 kg/m3, i.e. using a density bin of 0.025 kg/m3 centered on 1026.30 kg/m3 isopycnal. This resulted in 109 values, one per each day between the 13 April and the 31 July 2021. The flux at the upper boundary of the bin was obtained from the mean of the 109 values, and its uncertainty from the standard deviation. The same procedure was applied for the lower boundary of the bin. Finally, their difference was divided by the mean thickness of the isopycnal bin (in meters).

-

ΔIntegrated POC: the difference between the integrated POC on the 31 July and that on the 13 April 2021. The integrated POC (which includes bbp POC, MiP POC, and MaP POC) has been filtered and interpolated against density and time. For each interpolated profile, we calculated the average integrated POC within the isopycnal bin, obtaining a time series of 109 values. These were linearly interpolated using the lin regress function from the Python module scipy. The integrated POC and on the 13 April and 31 July were obtained from the results of the linear regression, and their uncertainty from the errors associated with the slope and the intercept of the interpolation.

This was repeated starting from 1026.30–1026.35 kg/m3 isopycnal bin until reaching 1027.35–1027.40 kg/m3. Each bin was 46 m deep on average. Finally, we calculated the mean depth of each isopycnal bin, providing the bulk POC removal rate at different depths. The uncertainty on the bulk POC removal rate was obtained by propagating the uncertainties on ΔFlux and ΔIntegrated POC.

The POC flux and the integrated POC were also calculated including the 0.025–0.102 mm size classes (Supplementary Note 1.3). Please note that the width of the isopycnal bins does not affect our calculations.

We calculated the amount of carbon exported due to (i) BGP and (ii) FECSP. To this aim, we only considered waters from the mixed layer depth to the lower limit of the eddy core, as they identify an isolated water parcel which was subducting; second, we only considered the time period prior to the eddy merging (between the 4 April and the 31 July 2021) to follow the same water parcel. We calculated the mean eddy surface \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) using the mean eddy radius (18928 ± 6543 km2). We then selected a isopycnal bin (e.g., 1026.30–1026.35 kg/m3) and proceeded as follows (Fig. 5a):

-

BGP: We calculate the mean POC flux \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) within an isopycnal as the sum of the POC flux of 0.102–16.40 mm particles (observed by the UVP) and the POC flux from particles between 0.025–0.102 mm (extrapolated from the particle 0.102–16.40 mm size spectrum, Supplementary Note 1.3). Finally, we calculate the BGP relative to the mean bin depth by multiplying \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) and \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\). The uncertainty on BGP was calculated by propagating errors on \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) and \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\). As error on \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\), we propagated the uncertainty of the mean eddy radius. The error on \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) was the standard deviation of the POC flux values within the isopycnal bin.

-

FECSP: We calculated the average POC content \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}\) in the isopycnal bin by summing together the bbpPOC and the POC from particles between 0.102–16.40 mm (observed by the UVP6) and between 0.025–0.102 mm (extrapolated from the particle 0.102–16.40 mm size spectrum, Supplementary Note 13). We calculated the subduction velocity \({{{\mathcal{V}}}}\) of the bin from the slope of the linear interpolation of the mean bin depth time series. Finally, we calculated the FECSP relative to the mean bin depth by multiplying \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\), \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}\), and \({{{\mathcal{V}}}}\). \({{{\mathcal{V}}}}\) was calculated after verifying that there was no correlation between the depth of the isopycnal and the distance from the eddy center (Supplementary Fig. 14), and after verifying that the distance of the float to the eddy center did not change significantly over time (Pearson test, not significant). This allowed us to reject the hypothesis that changes in the isopycnal depth were simply due to the float observing at different distances from the eddy center. The uncertainty on FECSP was calculated by propagating error on \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\), \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}\), and \({{{\mathcal{V}}}}\). As error on \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}\), we propagated the uncertainty on the error on bbp, MiP, and MaP POC (using the standard deviation of their content within the isopycnal bin). As error on \({{{\mathcal{V}}}}\), we used the uncertainty on the slope of the linear interpolation of the mean bin depth time series.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All the data necessary to produce the figures of the Main Text are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8386573. ADT, chlorophyll, and the other satellite data used in the present study are available on the E.U. Copernicus Marine Environment Service Information website (CMEMS, http://marine.copernicus.eu/). BGC Argo data were collected and made freely available by the International Argo Program and the national programs that contribute to it (https://argo.ucsd.edu, https://www.ocean-ops.org90). Attenuation coefficient k data are freely available on the Nasa Ocean color website (https://oceandata.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov).

Code availability

All the code used to analyze the data and produce the results of the present paper is available at https://github.com/rkiko/AC_Agulhas_eddy_2021.

References

Claustre, H., Legendre, L., Boyd, P. W. & Levy, M. The oceans’ biological carbon pumps: framework for a research observational community approach. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 780052 (2021).

De La Rocha, C. & Passow, U. 8.4—the biological pump. In Holland, H. D. & Turekian, K. K. (eds.) Treatise on Geochemistry, 93–122 (Elsevier, Oxford, 2014), 2nd edn. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780080959757006045.

Berelson, W. et al. Biogenic budgets of particle rain, benthic remineralization and sediment accumulation in the equatorial Pacific. Deep-Sea Res. Part II-Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 44, 2251–2282 (1997).

Irigoien, X. et al. Large mesopelagic fishes biomass and trophic efficiency in the open ocean. Nat. Commun. 5, 3271 (2014).

Boyd, P. W., Claustre, H., Levy, M., Siegel, D. A. & Weber, T. Multi-faceted particle pumps drive carbon sequestration in the ocean. Nature 568, 327–335 (2019).

St. John, M. A. et al. A dark hole in our understanding of marine ecosystems and their services: perspectives from the mesopelagic community. Front. Mar. Sci. 3, 31 (2016).

Burd, A. B. et al. Assessing the apparent imbalance between geochemical and biochemical indicators of meso- and bathypelagic biological activity: What the @$#! is wrong with present calculations of carbon budgets? Deep-Sea Res. Part II-Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 57, 1557–1571 (2010).

Giering, S. L. C. et al. Reconciliation of the carbon budget in the ocean’s twilight zone. Nature 507, 480–483 (2014).

Briggs, N., Dall’Olmo, G. & Claustre, H. Major role of particle fragmentation in regulating biological sequestration of co2 by the oceans. Science 367, 791–793 (2020).

Karstensen, J., Stramma, L. & Visbeck, M. Oxygen minimum zones in the eastern tropical Atlantic and pacific oceans. Prog. Oceanogr. 77, 331–350 (2008).

McGillicuddy Jr, D. J. et al. Influence of mesoscale eddies on new production in the Sargasso Sea. Nature 394, 263 (1998).

Stammer, D. Global characteristics of ocean variability estimated from regional topex/poseidon altimeter measurements. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 27, 1743 – 1769 (1997).

Wunsch, C. & Stammer, D. The global frequency-wavenumber spectrum of oceanic variability estimated from TOPEX/POSEIDON altimetric measurements. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 100, 24895–24910 (1995).

Carton, X. Hydrodynamical modeling of oceanic vortices. Surv. Geophys. 22, 179–263 (2001).

Omand, M. M. et al. Eddy-driven subduction exports particulate organic carbon from the spring bloom. Science 348, 222–225 (2015).

Lévy, M. & Martin, A. P. The influence of mesoscale and submesoscale heterogeneity on ocean biogeochemical reactions. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 27, 1139–1150 (2013).

Stukel, M. R., Song, H., Goericke, R. & Miller, A. J. The role of subduction and gravitational sinking in particle export, carbon sequestration, and the remineralization length scale in the California current ecosystem. Limnol. Oceanogr. 63, 363–383 (2018).

Laxenaire, R., Speich, S. & Stegner, A. Evolution of the thermohaline structure of one agulhas ring reconstructed from satellite altimetry and Argo Floats. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 124, 8969–9003 (2019).

Jayne, S. R. & Marotzke, J. The oceanic eddy heat transport. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 32, 3328 – 3345 (2002).

Chaigneau, A., Gizolme, A. & Grados, C. Mesoscale eddies off peru in altimeter records: Identification algorithms and eddy spatio-temporal patterns. Prog. Oceanogr. 79, 106–119 (2008).

Chelton, D. B., Schlax, M. G. & Samelson, R. M. Global observations of nonlinear mesoscale eddies. Prog. Oceanogr. 91, 167–216 (2011).

Laxenaire, R. et al. Anticyclonic eddies connecting the Western boundaries of Indian and Atlantic Oceans. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 123, 7651–7677 (2018).

Siegel, D. A., Peterson, P., McGillicuddy Jr., D. J., Maritorena, S. & Nelson, N. B. Bio-optical footprints created by mesoscale eddies in the Sargasso sea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38 (2011).

Gaube, P., McGillicuddy Jr, D. J., Chelton, D. B., Behrenfeld, M. J. & Strutton, P. G. Regional variations in the influence of mesoscale eddies on near-surface chlorophyll. J. Geophys. Res. 119, 8195–8220 (2014).

Bittig, H. C. et al. A BGC-argo guide: planning, deployment, data handling and usage. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 502 (2019).

Su, J., Strutton, P. G. & Schallenberg, C. The subsurface biological structure of southern ocean eddies revealed by bgc-argo floats. J. Mar. Syst. 220, 103569 (2021).

Cornec, M., Laxenaire, R., Speich, S. & Claustre, H. Impact of mesoscale eddies on deep chlorophyll maxima. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093470 (2021).

Chen, S. et al. Episodic subduction patches in the western north pacific identified from bgc-argo float data. Biogeosciences 18, 5539–5554 (2021).

Picheral, M. et al. The Underwater Vision Profiler 6: an imaging sensor of particle size spectra and plankton, for autonomous and cabled platforms. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 20, 115–129 (2022).

Kiko, R. et al. A global marine particle size distribution dataset obtained with the underwater vision profiler 5. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 4315–4337 (2022).

Boebel, O. et al. The Cape Cauldron: a regime of turbulent inter-ocean exchange. Deep-Sea Res. Part II-Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 50, 57–86 (2003).

Schütte, F. et al. Characterization of “dead-zone” eddies in the eastern tropical north Atlantic. Biogeosciences 13, 5865–5881 (2016).

Karstensen, J. et al. Upwelling and isolation in oxygen-depleted anticyclonic modewater eddies and implications for nitrate cycling. Biogeosciences 14, 2167–2181 (2017).

Pegliasco, C., Chaigneau, A. & Morrow, R. Main eddy vertical structures observed in the four major eastern boundary upwelling systems. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 120, 6008–6033 (2015).

Ioannou, A., Speich, S. & Laxenaire, R. Characterizing mesoscale eddies of eastern upwelling origins in the Atlantic ocean and their role in offshore transport. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 835260 (2022).

Flierl, G. R. Particle motions in large-amplitude wave fields. Geophys. Astrophys. Fluid Dyn. 18, 39–74 (1981).

Sverdrup, H. U. On conditions for the vernal blooming of phytoplankton. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 18, 287–295 (1953).

Koestner, D., Stramski, D. & Reynolds, R. A. A multivariable empirical algorithm for estimating particulate organic carbon concentration in marine environments from optical backscattering and chlorophyll-a measurements. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 941950 (2022).

Kriest, I. Different parameterizations of marine snow in a 1D-model and their influence on representation of marine snow, nitrogen budget and sedimentation. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 49, 2133–2162 (2002).

Dall’Olmo, G., Westberry, T. K., Behrenfeld, M. J., Boss, E. & Slade, W. H. Significant contribution of large particles to optical backscattering in the open ocean. Biogeosciences 6, 947–967 (2009).

Accardo, A. et al. Intense and localized export of selected marine snow types at eddy edges in the South Atlantic Ocean. Biogeosciences 22, 1183–1201 (2025).

Stemmann, L. & Boss, E. Plankton and particle size and packaging: from determining optical properties to driving the biological pump. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 4, 263–290 (2012).

Drago, L. Analyse globale de la pompe à carbone biologique à partir de données en imagerie quantitative. Theses, Sorbonne Université https://theses.hal.science/tel-04483392 (2023).

Kiko, R. et al. Zooplankton-mediated fluxes in the Eastern Tropical North Atlantic. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 358 (2020).

Soviadan, Y. D. et al. Marine snow morphology drives sinking and attenuation in the ocean interior. EGUsphere 2024, 1–21 (2024).

Clements, D. J. et al. New estimate of organic carbon export from optical measurements reveals the role of particle size distribution and export horizon. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 37, e2022GB007633 (2023).

Belcher, A. et al. Depth-resolved particle-associated microbial respiration in the northeast Atlantic. Biogeosciences 13, 4927–4943 (2016).

del Giorgio, P. & Williams, P. (eds.) Respiration in aquatic ecosystems (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005). https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198527084.001.0001/acprof-9780198527084.

Robinson, C. Microbial respiration, the engine of ocean deoxygenation. Front. Mar. Sci. 5, 533 (2019).

Stemmann, L. et al. Volume distribution for particles between 3.5 to 2000 μm in the upper 200 m region of the south pacific gyre. Biogeosciences 5, 299–310 (2008).

Li, J., Antoine, D. & Huot, Y. Bio-optical variability of particulate matter in the southern ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1466037 (2024).

McGillicuddy, D. J. Mechanisms of physical-biological-biogeochemical interaction at the oceanic mesoscale. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 8, 125–159 (2016).

Herbette, S., Morel, Y. & Arhan, M. Subduction of a surface vortex under an outcropping front. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 34, 1610 – 1627 (2004).

Laxenaire, R., Speich, S. & Stegner, A. Agulhas ring heat content and transport in the south Atlantic estimated by combining satellite altimetry and argo profiling floats data. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 125, e2019JC015511 (2020).

Chen, Y., Speich, S. & Laxenaire, R. Formation and transport of the south Atlantic subtropical mode water in Eddy-permitting observations. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 127, e2021JC017767 (2022).

Melander, M. V., Zabusky, N. J. & Mcwilliams, J. C. Symmetric vortex merger in two dimensions: causes and conditions. J. Fluid Mech. 195, 303–340 (1988).

Yasuda, I. & Flierl, G. R. Two-dimensional asymmetric vortex merger: merger dynamics and critical merger distance. Dyn. Atmos. Oceans 26, 159–181 (1997).

Perrot, X. & Carton, X. 2D vortex interaction in a non-uniform flow. Theor. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 24, 95–100 (2010).

Cresswell, G. R. The coalescence of two east australian current warm-core eddies. Science 215, 161–164 (1982).

Rykova, T. & Oke, P. R. Stacking of EAC eddies observed from Argo. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 127, e2022JC018679 (2022).

Kalvelage, T. et al. Aerobic microbial respiration in oceanic oxygen minimum zones. PLoS One 10, 1–17 (2015).

Bianchi, D., Weber, T. S., Kiko, R. & Deutsch, C. Global niche of marine anaerobic metabolisms expanded by particle microenvironments. Nat. Geosci. 11, 263–268 (2018).

Iversen, M. H. & Ploug, H. Ballast minerals and the sinking carbon flux in the ocean: carbon-specific respiration rates and sinking velocity of marine snow aggregates. Biogeosciences 7, 2613–2624 (2010).

McDonnell, A. M. P., Boyd, P. W. & Buesseler, K. O. Effects of sinking velocities and microbial respiration rates on the attenuation of particulate carbon fluxes through the mesopelagic zone. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 175–193 (2015).

Collins, J. R. et al. The multiple fates of sinking particles in the north Atlantic ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 1471–1494 (2015).

Hernández-León, S. & Ikeda, T. A global assessment of mesozooplankton respiration in the ocean. J. Plankton Res. 27, 153–158 (2005).

Hansell, D. A. Recalcitrant dissolved organic carbon fractions. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 5, 421–445 (2013).

Briggs, N. et al. High-resolution observations of aggregate flux during a sub-polar North Atlantic spring bloom. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 58, 1031–1039 (2011).

Eurostat, M. Energy, transport and environment statistics, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-statistical-books/-/ks-dk-20-001 (2020).

Gruber, N. et al. Eddy-induced reduction of biological production in eastern boundary upwelling systems. Nat. Geosci. 4, 787–792 (2011).

Hernández-Carrasco, I., Rossi, V., Hernández-García, E., on, V. G. & López, C. The reduction of plankton biomass induced by mesoscale stirring: A modeling study in the benguela upwelling. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 83, 65–80 (2014).

Martin, J. H., Knauer, G. A., Karl, D. M. & Broenkow, W. W. Vertex: carbon cycling in the northeast pacific. Deep Sea Res. Part A. Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 34, 267–285 (1987).

Ballarotta, M. et al. On the resolutions of ocean altimetry maps. Ocean Sci. 15, 1091–1109 (2019).

Taburet, G. et al. DUACS DT2018: 25 years of reprocessed sea level altimetry products. Ocean Sci. 15, 1207–1224 (2019).

Pujol, M.-I. et al. DUACS DT2014: the new multi-mission altimeter data set reprocessed over 20 years. Ocean Sci. 12, 1067–1090 (2016).

Kovač, Ž., Platt, T. & Sathyendranath, S. Sverdrup meets Lambert: analytical solution for Sverdrup’s critical depth. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 78, 1398–1408 (2021).

Bouman, H. A. et al. Photosynthesis–irradiance parameters of marine phytoplankton: synthesis of a global data set. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 251–266 (2018).

Group, N. O. B. P. Modis-aqua level 3 mapped downwelling diffuse attenuation coefficient data version r2018.0 https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/10.5067/AQUA/MODIS/L3M/KD/2018 (2017).

Baudena, A. et al. Fine-scale structures as spots of increased fish concentration in the open ocean. Sci. Rep. 11, 15805 (2021).

Zhai, L. et al. Estimation of phytoplankton loss rate by remote sensing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2008GL035666. (2008).

Lahajnar, N. et al. Mooring Rescue, Cruise No. SO283, 19 March 2021—25 May 2021, Emden Germany—Emden Germany, SONNE-Berichte https://www.tib.eu/de/suchen/id/awi%3A4bb98aaa67f1ac9136cce7d6c2fc6ca1693a0b03 (2021).

Nencioli, F., Kuwahara, V. S., Dickey, T. D., Rii, Y. M. & Bidigare, R. R. Physical dynamics and biological implications of a mesoscale eddy in the lee of Hawai’i: Cyclone Opal observations during E-Flux III. Deep-Sea Res. Part II-Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 55, 1252–1274 (2008).

Garcia, H. et al. World ocean atlas 2018: product documentation. A. Mishonov, Tech. Editor. 1, 1–20 (2019).

de Boyer Montégut, C., Madec, G., Fischer, A. S., Lazar, A. & Iudicone, D. Mixed layer depth over the global ocean: an examination of profile data and a profile-based climatology. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 109 https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JC002378. (2004).

Roquet, F., Madec, G., McDougall, T. J. & Barker, P. M. Accurate polynomial expressions for the density and specific volume of seawater using the TEOS-10 standard. Ocean Model. 90, 29–43 (2015).

Stramski, D. et al. Relationships between the surface concentration of particulate organic carbon and optical properties in the eastern South Pacific and eastern Atlantic Oceans. Biogeosciences 5, 171–201 (2008).

Cetinić, I. et al. Particulate organic carbon and inherent optical properties during 2008 north Atlantic bloom experiment. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 117 (2012).

Kiko, R. et al. Biological and physical influences on marine snowfall at the equator. Nat. Geosci. 10, 852–858 (2017).

Alldredge, A. The carbon, nitrogen and mass content of marine snow as a function of aggregate size. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 45, 529–541 (1998).

Argo, G. Argo float data and metadata from Global Data Assembly Centre (Argo GDAC)—Snapshot of Argo GDAC of July 09st 2023. SEANOE. Seanoe (2020).

Acknowledgements

A.B., R.K., S.S., and L.S. received support from the European Union project TRIATLAS (European Union Horizon 2020 program, grant agreement 817578). R.K. and A.B. furthermore acknowledge support via a Make Our Planet Great Again grant from the French National Research Agency (ANR) within the Programme d’Investissements d’Avenir #ANR-19-MPGA-0012. A.B. received support from the European Union - NextGenerationEU and by the Ministry of University and Research (MUR), National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.5, project “RAISE - Robotics and AI for Socio-economic Empowerment” (ECS00000035). RK acknowledges funding from the Heisenberg Programme of the German Science Foundation #KI 1387/5-1. SS received support from the OCEAN:ICE project that is co-funded by the European Union, Horizon Europe Funding Programme for research and innovation under grant agreement Nr. 101060452 and by UK Research and Innovation and the ERC Syg grant WHIRLS under agreement Nr. 101118693. The authors thank Inés Jambou for her help in the design of Figs. 4a, and 5a, and Tables 1 and 2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B. and R.K. designed the research with assistance from R.L., S.S., and L.S. A.B. performed the analyses. R.L. run the TOEddies tool to track the eddies, with assistance from A.I. A.B. and R.K. wrote the paper, with assistance from R.L., S.S., and L.S. C.C., E.L., M.P., and A.P. provided the BGC Argo data. All authors provided feedback and helped in shaping the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Alice Drinkwater, and Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baudena, A., Laxenaire, R., Catalano, C. et al. A Lagrangian perspective reveals the carbon and oxygen budget of an oceanic eddy. Commun Earth Environ 6, 318 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02262-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02262-9