Abstract

The growth of the Tibetan Plateau is traditionally attributed to the India-Asia collision and subsequent convergence. However, recent paleo-elevation reconstructions suggest that Gangdese arc in southern Tibetan Plateau reached >4.0 km before or alongside the collision. Here we reconstruct the crustal thickness evolution of the Gangdese arc during the Late Cretaceous-Cenozoic using a machine learning model and investigate the thermal evolution by analyzing the metamorphic temperature-pressure-age properties of crustal rocks. Isostatic calculations are performed to constrain the crustal density evolution. Our results show that crustal thickness decreased from ~60 to ~40 km between 80 and 55 Ma, with an increase in lithosphere geotherm and a drop in average crustal density (from ~2.97 to ~2.70 g/cm3). These results suggest the removal of a 20 km thick dense lower crust during that period. Combined with numerical modeling and geological evidence, we propose that lower crustal foundering drove the uplift of the Gangdese arc during the Paleocene, independent of the India-Asia collision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Tibetan Plateau, the world’s largest orogenic plateau, is distinguished by its high elevation (~5 km), low relief, and thick crust (≥70 km). Its formation shapes the global hydroclimate by creating orographic barriers1,2, dictates the flow of Asian rivers and the distribution of water resources3, drives the evolution of regional ecosystems and biodiversity4, and regulates carbon cycling through enhance weathering and organic carbon sequestration5. The growth of the Tibetan Plateau was traditionally attributed to the collision and ongoing convergence between the India and Asia plates. However, the timing and dynamic mechanisms of uplift in different regions of the Tibetan Plateau are still controversial due to its complex geological history and uncertainties in paleo-altimetry and tectonic interpretations6,7,8,9,10,11.

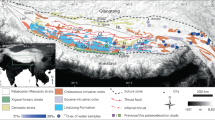

The east-west trending Gangdese magmatic arc (with a width of 100–150 km) in southern Tibet (Fig. 1) was formed during Neo-Tethyan subduction in the Mesozoic and subsequent India-Asia collision in the Cenozoic12,13,14. The initial timing of the India-Asia collision remains debated, with estimates ranging from ≥65 Ma to ~25 Ma inferred from various geological records such as stratigraphy, magmatism, metamorphism, and paleomagnetism6,15. Among these approaches, stratigraphy represents the one of the most robust and direct method for unraveling collision chronology15,16. The abrupt compositional change in sediment provenance within upper Paleocene-lower Eocene strata along the southern flank of the suture zone suggests that the initial collision most likely occurred at 59 ± 1 Ma6,15,16. Prior to or synchronous with the collision, the Gangdese arc had undergone substantial uplift17,18. Paleo-elevation reconstructions using oxygen and clumped isotope paleo-altimetry suggest that the Gangdese arc attained an elevation of 2.7 km (+0.5/−0.9 km) at 83–78 Ma18 and subsequently rose to >4.0 km by no later than 60–54 Ma17,18. Several models, including crustal thickening19, break-off of the Neo-Tethyan oceanic lithosphere6, and delamination of lithosphere mantle without the lower crust18,20, have been proposed to explain the uplift of the Gangdese to its near-present elevation.

Continental elevations are determined by a combination of crustal density and thickness, lithospheric thermal structure, and geodynamic forces21. However, the existing models, while providing valuable insights, have not fully addressed the temporal evolution of crustal thickness and density, geothermal gradient, and elevation. The lack of a comprehensive analysis of these factors limits their ability to resolve the ongoing debates surrounding the uplift history. This limitation stems from insufficient constraints on the lithospheric geotherm and the uncertainty of previous paleo-crustal thickness data. Proxies such as La/Yb and paired Sr/Y-La/Yb of magmatic rocks19,22 or Eu anomalies in detrital zircons23 have been employed to constrain crustal thickness evolution of the Gangdese. However, these proxies were calibrated using data from subduction arc settings, where magmatic processes are dominantly controlled by differentiation of mantle-derived melts. This raises questions about their reliability when applied to the Gangdese region, especially post the India-Asia collision, where magmatic processes may involve more complex evolutionary mechanisms, such as interactions between mantle and crustal sources, as well as extensive crustal reworking. This uncertainty stems from the fact that the correlations between Sr/Y and La/Yb ratios and crustal thickness in collisional belts are not accurately replicated by models developed for arc environments24.

Here, we reconstruct the evolution of crustal thickness of the Gangdese arc during the Late Cretaceous-Cenozoic using a newly developed machine learning model trained on large geochemical and geophysical datasets25. This machine learning model is applicable to both arc and orogenic belt settings25 and provides more robust estimates of crustal thickness than previous methods, as evidenced by its improved consistency with geophysical observations (Supplementary Fig. S1). Simultaneously, we investigate the evolution of geothermal gradient by analyzing the metamorphic pressure and temperature conditions, as well as the metamorphic age of rocks from the middle and lower crust. These geothermal gradients are then used to quantify the thermal effects on elevation changes. By integrating these results with elevation data and other geological evidence, we propose that lower crustal foundering (i.e., delamination of lithospheric mantle along with lower crust) was the primary mechanism driving the rapid uplift of the Gangdese arc in southern Tibet during the Paleocene, which is further supported by numerical modeling. Our study negates the necessity of invoking the India-Asia collision as the driving force for reaching a high elevation in southern Tibet.

Results

Crustal thickness evolution of the Gangdese arc

The machine learning model uses 10 major oxide (SiO2, TiO2, Al2O3, FeO, MnO, MgO, CaO, Na2O, K2O, P2O5) and 22 trace element (La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, Lu, Sr, Y, Rb, Ba, Hf, Nb, Ta, Th) compositions of intermediate to felsic rocks to calculate crustal thickness at the time of rock formation25. The compositions of magmatic rocks within the Gangdese arc used in this study are compiled from the literature. Data filtering criteria refer to Guo & Yang25 and include ages ≤100 Ma, loss on ignition absolute values ≤ 2 wt.%, SiO2 of 55–75 wt.%, and MgO ≤ 6 wt.%. Since the contents of fluid-mobile elements (such as Ba, Rb, Sr) show no correlation with the residuals (calculated crustal thickness minus true crustal thickness) (Supplementary Fig. S2), we chose not to filter the data by Rb/Sr ratios as proposed by Chapman et al.26. A total of 1435 intermediate to felsic rocks are selected for calculation, nearly three times the sample size of Guo and Yang25, which improves the accuracy of crustal thickness estimations. Detailed descriptions of these rocks are given in the Supplementary Data S1. Calculated crustal thicknesses of individual samples are shown in Fig. S3. The results calculated using the paired Sr/Y-La/Yb method proposed by Sundell et al.22 are also shown for comparison in Supplementary Fig. S3.

Individual crustal thickness estimates within the same locality may exhibit significant variations and deviate from the true values25,26,27,28. To derive meaningful estimates of paleo-crustal thickness, it is crucial to consider binned mean or median values of samples over length scales spanning several tens to few hundreds of kilometers after carefully assessing spatial heterogeneity. Our results suggest that the along-arc variations in crustal thickness of the Gangdese may exist but are not pronounced (Supplementary Fig. S4). The mean crustal thickness of the Gangdese arc increased from 44.4 ± 2.3 km to 59.3 ± 6.7 km between 100 and 80 Ma (Fig. 2). At ~70 Ma, the crustal thickness sharply thinned to 41.0 ± 3.9 km. This thin crustal configuration persisted until ~55 Ma. Subsequently, the crustal thickness increased slightly from 39.6 ± 5.0 km at ~55 Ma to 45.9 ± 9.3 km at ~45 Ma, followed by a sharp increase to 58.7 ± 6.5 km at ~40 Ma. Further hypothesis testing indicates that the crustal thickness at ~70 Ma was 15.7–20.9 km lower than at ~80 Ma, at ~45 Ma was 4.4-8.3 km higher than that at ~55 Ma, and at ~40 Ma was 10.2–15.4 km higher than at ~45 Ma (90% confidence level). The crustal thickening process continued until about 20 Ma, when the crust attained its near-present thickness of 72.0 ± 3.1 km.

The calculated crustal thicknesses for individual samples are available in the Supplementary Fig. S1. The red circles indicate the binned averages of crustal thicknesses for every 5 m.y., with error bars representing the standard deviation. The histograms show the number of samples in each bin. The black line represents the maximum likelihood of median values distribution from bootstrap iterations applied on a 10 m.y. rolling window at 1 m.y. steps. The orange areas represent 1σ and 2σ standard deviations around the median values line. The black squares represent elevations estimated by paleo-altimetry from the Linzhou and Namling basins. Elevation data and relevant errors are provided in Supplementary Data S3. The correlation between crustal thickness and elevation is established assuming crustal isostasy with crustal and mantle density of 2.87 g/cm3 and 3.35 g/cm3, respectively. The green rectangles denote peak metamorphic depths of rocks from the Gangdese arc root. More information is given in Supplementary Data S2. Regional geological events are shown in brown horizontal strips for comparison.

Peak metamorphic pressures at specific time intervals recorded by rocks from the arc root can provide minimum estimations of the crustal thickness. At 89–80 Ma, the protolith of garnet amphibolites and migmatites from the Gangdese arc root experienced granulite-facies metamorphism at a peak pressure of 1.5–1.7 GPa, corresponding to a formation depth of 50–56 km29,30,31. Similar granulite-facies metamorphism at arc root have also been identified at 77–68 Ma32 and 67–52 Ma33,34, with peak metamorphic pressures of 1.0–1.3 GPa (35-44 km) and 0.9–1.1 GPa (32–38 km), respectively. These metamorphic depths are consistent with our calculated crustal thicknesses (Fig. 2).

Thermal evolution and its effect on elevation

The lithospheric thermal conditions can lead to continental elevation variations of up to 2–3 km21,35,36 through changing rock density due to thermal expansion or contraction, known as thermal isostasy. Here we assess the influence of thermal buoyancy on the elevation changes of the Gangdese arc by examining the evolution of the geothermal gradient.

The metamorphic temperature, pressure, and age data of rocks from the middle and lower crust of the Gangdese arc (Supplementary Note S1 and Supplementary Data S2) are used to construct the geothermal gradients over time. The related rocks include granulite, metagabbro, amphibolite, migmatite, schist, gneiss, and metapelite. These rocks have experienced granulite or amphibolite facies metamorphism. By plotting the compiled metamorphic temperature-pressure data on the preferred geotherms developed by Hasterok and Chapman37, we estimate the best-fit heat flows for the time intervals of 89–80, 67–52, and 36–26 Ma to be 60 ± 2 mW/m2, 78 ± 2 mW/m2, and 62 ± 3 mW/m2, respectively (Fig. 3a). Additional constraints on the lithosphere geotherm come from the initial melting/equilibrium depth of mafic magmas, which serve as a paleoproxy for lithospheric thickness38. The mean melting/equilibrium pressures of the primary magma of the 57 Ma basalt is determined to be 2.0 ± 0.1 GPa (Supplementary Data S3), indicating a lithospheric thickness of 64.6 ± 3.0 km at that time. This result is consistent with the characteristics of a hot geotherm (Fig. 3a). The contributions of various thermal regimes to elevation changes are quantified using the methods of Hasterok and Chapman21, which define thermal isostasy as a function of heat flow. Based on the best-fitting continental heat flow-elevation model, the elevations due to thermal isostasy effect at 89–80, 67–52, and 36–26 Ma are 1.1 ± 0.3 km, 1.9 ± 0.2 km, and 1.2 ± 0.3 km, respectively (Fig. 3b). Although we utilize the preferred geotherms of Hasterok & Chapman in this analysis, opting for alternative geothermal models yields only negligible differences (<0.2 km) in the estimated thermal isostasy (Supplementary Fig. S5).

a The metamorphic depth (pressure)-temperature-age properties of rocks from middle and lower crust (filled circles) are complied from the literature and given in Supplementary Data S2. The melting depths and temperatures of the 57 Ma basalts (unfilled circles) are calculated using the method of Lee et al.71 with data complied from the literature (Supplementary Data S3). The reference geotherms are from Hasterok and Chapman37. b The back line represents the best-fitting thermal isostatic curve with a reference zero-elevation heat flow of 46.6 mW/m2, constructed from 34 North American tectonic provinces (gray squares) by Hasterok and Chapman21. The orange area represents the uncertainty envelope for the best-fitting thermal isostatic curve with Root Mean Square (RME) < 0.8. The thermal elevations are defined as a function of heat flow. The present-day Gangdese arc has a heat flow of 42.5 ± 2.0 mW/m2 (derived from its lithospheric thickness of 190 ± 30 km46) and a thermal isostasy of −0.4 ± 0.5 km (calculated from crustal isostasy with a crustal thickness of 72.0 ± 3.5 km, crustal density of ~2.87 g/cm³, and an elevation of 4.9 ± 0.2).

Transition in crustal density during the Late Cretaceous-Cenozoic

We investigate the paleo-elevation of the Gangdese arc on three periods around 80, 55, and 30 Ma for which complete data on crustal thickness, elevation, and thermal gradient are available (Supplementary Note S2). The elevation data estimated from paleo-altimetry are compiled from the Linzhou and Namling (Oiyug) basins (Fig. 1) and are provided in Supplementary Data S4. Based on the mean and error analysis of multiple results, the estimated elevations at ~80 Ma, ~55 Ma, and ~30 Ma are 2.7 km (+0.5/−0.9 km)18, 4.4 km (+0.3/−0.4 km)17,18, and 4.2 km (+0.7/−0.9 km)39,40, respectively. By subtracting the thermal elevations from the estimated elevations, the non-thermal elevations at ~80, ~55, and ~30 Ma are determined to be 1.6 km (+0.6/−0.9 km), 2.5 km (+0.4/−0.4 km), and 3.0 km (+0.8/−0.9 km), respectively.

Factors such as flexural support41 and dynamic topography42,43 may influence elevation. However, there is no evidence of topographic loads on either side of the Gangdese arc during the Late Cretaceous-Eocene6, and our analysis suggests that the Tibetan Plateau is thermally weak, indicating that the contribution of flexural support to the elevation is expected to be negligible41. Global mantle convection models that assimilate plate reconstruction data within the past 200 million years44 predict that temporal variation in long-wavelength dynamic topography in the Gangdese region after 80 Ma is limited to just a few hundred meters. Present-day free-air gravity anomalies in most of the Lhasa terrane, derived from the high-resolution EGM2008 model45, are within ±50 mGal, suggesting near-isostatic equilibrium46 and negligible dynamic topography. Therefore, the non-thermal elevations were predominantly controlled by crustal isostasy, allowing us to use them to constrain the crustal density variation in these periods under the assumption of negligible contributions from flexural support and dynamic topography.

We calculate the evolution of the average crustal density using the isostatically compensated model. By plotting global continental elevation versus crustal thickness, the theoretical best-fit line represents crustal isostasy, with the slope of the line reflecting the density contrast between the crust and mantle. Assuming a mantle density (ρm) of 3.35 g/cm3[,21, the reference crustal density (ρc0) is estimated to be 2.87 g/cm3 based on the best-fit line47. Any point on the best-fit line can serve as a reference standard crustal column. Here, we select a reference standard crustal column with a mean crustal thickness (H0) of 70 km and an elevation (h0) of 5 km, which roughly corresponds to the present Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 4a). Using the isostatic equation h = h0 + H(1−ρc/ρm)−H0(1−ρc0/ρm), where h, H, and ρc represent non-thermal elevation, crustal thickness, and crustal density at special time snapshots and applying Monte Carlo analysis, we determine the crustal densities under standard thermal condition (defined here by a reference heat flow of 46.6 mW/m2 with zero thermal isostasy21). The results for ~80, ~55, and ~30 Ma are 2.97 ± 0.06 g/cm3, 2.70 ± 0.09 g/cm3, and 2.93 ± 0.06 g/cm3, respectively (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that the average crustal density of Gangdese arc decreased dramatically during the Paleocene and increased during the Eocene. These variations in the calculated crustal density primarily reflect compositional changes, which provide valuable insights into crustal evolution.

a Cartoon illustrating parameters used for the crustal isostatic calculation. The mantle density (ρm) is assumed to be 3.35 g/cm3[,21. The reference standard crustal column has a crustal thickness (H0) of 70 km, elevation (h0) of 5 km, and crustal density (ρc0) of 2.87 g/cm3[,47, roughly corresponds to the present Tibetan Plateau. After removing the effect of thermal isostasy, the non-thermal elevation is controlled by crustal isostasy, then h = h0 + H(1−ρc/ρm)−H0(1−ρc0/ρm), where h, H, and ρc represent non-thermal elevation, crustal thickness, and crustal density, respectively. b Non-thermal elevation versus crustal thickness at ~80, ~55 and ~30 Ma (filled circles). Error bars represent the propagated errors. The unfilled circles and related errors are plotted using the mean elevations derived from the mean processing and error analysis of multiple measurements. The light green lines represent the crustal density (g/cm3) formulated from the isostatic equation. Global continental elevation and crustal thickness at 1° resolution (gray and black dots) from the CRUST1.0 model78 are also shown for comparison. The dark green line represents the theoretical best-fit correlation line between global continental elevation and crustal thickness assuming crustal isostasy. The black dots represent the present Tibetan Plateau.

Discussion

Our analysis of the crustal thickness evolution suggests that the Gangdese arc crust experienced thinning of ~20 km during the latest Cretaceous and remained thin during the Paleocene. A similar thinning record has been observed from paired Sr/Y-La/Yb of magmatic rocks19,22 and Eu anomalies in detrital zircons23. These findings argue against the hypotheses that crustal thickening19 or delamination of the lithospheric mantle alone18,20 were the primary causes of the Gangdese uplift during the Paleocene. Sundell et al.22 proposed that the crustal thinning resulted from backarc extension associate with slab rollback, accompanied by the rift of the Xigaze arc from the southern Gangdese arc. Alternatively, the process of crustal thinning and lithospheric heating point towards the crustal foundering12. The evolution of average crustal density provide crucial constraints on these two distinct explanations.

At ~80 Ma, the Gangdese arc exhibited an average crustal density of 2.97 ± 0.06 g/cm3, exceeding the current crustal density (~2.87 g/cm3, estimated from a 3D crustal density model constrained by seismic velocity structure48). However, by ~55 Ma, the average crustal density of the Gangdese arc had decreased to 2.70 ± 0.09 g/cm3. This value was lower than the current crustal density but comparable to the average density of the middle and upper crust predominantly composed of intermediate to felsic rocks49. Combining the constrained variations in crustal thickness, paleo-elevation, lithosphere thermal state, and crustal density between 80 and 55 Ma, we propose that lower crustal foundering played a crucial role in driving the uplift of the Gangdese arc during the Paleocene.

The long-lived magmatic activity in the Gangdese arc since the Triassic, characterized by distinct phases of gabbro, diorite, granodiorite, monzogranite, hornblende gabbro, and tonalite emplacement, had led to the formation of a substantial layer of mafic/ultramafic cumulates in the lower crust by the late Cretaceous14,50. During the late Cretaceous, the Gangdese arc experienced gradual thickening, reaching a crustal thickness of 59.3 ± 6.7 km at ~80 Ma. This thickening process was attributed to the combined effects of magmatic inflation and contractional deformation, demonstrated by a magmatic flare-up occurring at 90–75 Ma14 and a north-south shortening between 90 and 70 Ma20. As a consequence of this thickening process, the cumulates in the lower crust beyond the depth of 40 km would transform into garnet-rich granulites or pyroxenites as observed in other subduction zones such as the Kohistan arc and Sierra Nevada49,51,52. These rocks were denser than the underlying upper mantle and gravitationally unstable. Assuming the dense lower layer, which was ~20 km thick at ~80 Ma, had an average density of ~3.45 g/cm347,53, a simple calculation suggests that the uppermost 40 km of the crust at ~80 Ma should have an average crustal density of 2.73 ± 0.09 g/cm3, similar with the average crustal density at ~55 Ma. These results, combined with the decrease of crustal thickness from 59.3 ± 6.7 to 39.6 ± 5.0 km between ~80 and ~55 Ma, suggest that a 20 km thick dense lower crust was removed during this period. The loss of dense lower crust drove the remaining crust toward a low average density. This crustal foundering most likely occurred between 75 and 70 Ma, as evidenced by the sharp crustal thinning at that time.

Our crustal foundering model offers a plausible explanation for several geological observations. Firstly, following a short period of magma lull between 75-70 Ma, magmatic activity resumed at ~69 Ma, marked by the early-stage (69–55 Ma) eruption of the Linzizong volcanism54,55,56. Notably, high-MgO (up to 14.35 wt.%) basalts erupted around ~57 Ma57 exhibit geochemical and isotopic characteristics (e.g., 87Sr/86Sr = 0.7043−0.7061; εNd(t) = 5.24−3.58; 206Pb/204Pb = 18.347−18.678) that are indicative of an asthenospheric mantle source influenced by variable crustal components58. While this early-stage volcanism has often been attributed to the rollback of the Neo-Tethyan slab and associated backarc extension54,55, slab rollback alone fails to account for the sharp reduction in average crustal density observed during this time. In contrast, crustal foundering provides a consistent explanation for both the magmatic resurgence and the density evolution. Secondly, an angular unconformity is evident between the strongly deformed Late Cretaceous Shexing Formation (82–78 Ma) and the overlying weakly deformed Linzizong succession throughout the Gangdese arc18,20. The deformation of the Shexing Formation has been attributed to north-south shortening. The upwelling of the asthenosphere after crustal foundering could lead to changes in the regional stress field, potentially contributing to surface uplift and the relief of overlying strata from deformation. Thirdly, the magmatic rocks from the Gangdese arc displayed a compositional shift at ~70 Ma with the increase in K2O/SiO2, K2O/Na2O, and Th/La ratios, suggesting the remelting of arc lower crust in a hotter regime14. Lastly, recent high-resolution seismic data suggests that the current Gangdese crust has low velocity (vp < 6.7 km/s) and is predominantly composed by felsic composition59, indicating the removal of massive mafic lower crustal rocks during crustal growth.

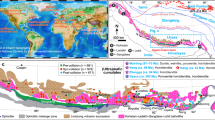

We conduct numerical modeling to investigate lower crustal foundering through density sorting and its impact on elevation change (Fig. 5). Our model encompasses a 200 km wide orogenic belt with an initial crustal thickness of 60 km, consisting of an upper crust of 35 km and a lower crust of 25 km (see “Methods”). During the modeling, the mafic lower crust undergoes eclogitization and experiences a density increase from 3.00 g/cm3 to 3.45 g/cm3 when the pressure and temperature meet metamorphism conditions. The ~20 km thick densified lower crust initiates foundering of the lower crust and mantle lithosphere, reducing the crustal thickness from 60 km to 40 km (Fig. 5a). In response to this foundering process, the hot asthenospheric mantle upwells and undergoes low degrees of partial melting (Fig. 5c). This contributes to the development of a hotter lithospheric geotherm within the orogenic belt (Fig. 5b) and results in a topography uplift of ~ 1.5 km (Fig. 5a). These modeling results align well with observations of the increase in heat flow and a rise in elevation from 2.7 km (+0.5/−0.9 km) to 4.4 km (+0.3/−0.4 km) between 80 and 55 Ma. The numerical modeling results thus support the feasibility of lower crustal foundering as a driving mechanism behind the uplift of Gangdese arc.

a Evolution of surface topography and crustal thickness. b Evolution of lithospheric geotherm. c Two snapshots before (0.27 Myr) and after (7.40 Myr) the crustal foundering. The white lines are isotherms between 150 °C and 1150 °C. Red contours represent 2–8% degrees of mantle partial melting. Arrows represent mantle motion velocity (arrow size is scaled to the velocity magnitude square root to reduce the plotted arrow size contrast).

The foundering of the lower crust and underlying mantle lithosphere removed dense material beneath the Gangdese arc (Fig. 6b), creating space for renewed injections of mantle-derived melts. The cumulates began to re-form in the arc base due to a magmatic flare-up at ~55–45 Ma, likely triggered by the breakoff of the Neo-Tethys oceanic slab13,60,61 (Fig. 6c). The renewed magmatic inflation, coupled with underthrusting of forearc beneath the Gangdese arc as a result of the India-Asia collision62,63, contributed to crustal thickening between ~55 and ~20 Ma. Consequently, the average crustal density increased from 2.70 ± 0.09 g/cm3 at ~55 Ma to 2.93 ± 0.06 g/cm3 at ~30 Ma. However, the occurrence of widespread potassic adakitic magmatism64,65,66 and regional east-west extension67 suggest the possibility of foundering of thickened mantle lithosphere (with minor lower crust, Fig. 2) beneath the Gangdese arc during the middle Miocene68, which led to the increase in elevation from 4.2 km (+0.7/−0.9 km) to 5.1 km (+0.4/−0.3 km)39,69,70. We propose that episodic formation and removal of thickened lithosphere since the Late Cretaceous are crucial for the uplift of the Gangdese arc to its present high elevation. The paleo-crustal thickness evolution predicted by our machine learning model, along with other data, helps to resolve the debates about the mechanisms of paleo-elevation variation and plateau growth in southern Tibet and their relation to the India-Asia collision.

Methods

Crustal thickness calculation

We calculate the crustal thickness using the Extremely Randomized Trees algorithm-based machine learning model developed by Guo & Yang25. The model was trained using 10 major oxides and 22 trace element compositions of 1480 intermediate to felsic rocks and crustal thickness data obtained from geophysical surveys. The application of this model to testing data and to the Kohistan and Talkeetna arcs demonstrated its superiority in estimating crustal thickness compared to commonly used geochemical proxies such as Sr/Y and La/Yb ratios25. The prediction error of this machine learning model for individual samples is about 5 km, which is similar to the mean standard error of the geophysically detected crustal thickness. However, it is important to note that the variation in calculated crustal thickness among samples with similar ages may be significant (e.g., ranging from ~30 km to ~60 km at ~55 Ma) due to the prediction error and the unevenness of crustal thickness at local scales. To address this uncertainty, we process the initial results derived from the machine learning model using statistical methods of binned averaging and the maximum likelihood of the median value distribution. This allows us to obtain more robust and reliable estimates of crustal thickness at certain time snapshots, reducing the impact of potential variations and errors associated with individual samples. In these statistical analyses, the uncertainties of inferred crustal thickness are sensitive to the number of samples. Having a sufficient number of samples (≥10) for calculations is crucial to minimize uncertainties.

Geotherm and thermal isostasy

In a 1D, steady-state heat conduction model, the temperature (Tb) and heat flow (qb) at the bottom of a layer with thickness Δz, heat generation (A) and thermal conductivity (k) can be expressed in terms of the temperature (Tt) and heat flow (qt) at the top of the layer and the parameters A and k of the layer:

The reference geotherms37 in this study are constructed through the application of Eqs. (1) and (2) to successive layers, each with a depth of 0.1 km. At the beginning of each new layer, the values of Tt and qt at the top are reset using the values Tb and qb solved for the bottom of the previous layer. The thermal conductivity (k) is P-T-composition dependent and updated at each step in an iterative loop37. The heat production (A) is modeled using a three-layered approach, with a lower crustal A of 0.4 μW m−3, mantle lithosphere A of 0.02 μW m−3, and variable values for the upper crust. The upper crust has a thickness (HUC) of 16 km, and the lower crust has a thickness (HLC) of 23 km. The observed surface heat flow (qs) is partitioned into upper crustal radiogenic sources and deeper sources with a partition coefficient of F = 0.74. The A for the upper crust (AUC) is calculated as

The metamorphic temperature, pressure, and age data of crustal rocks used to construct the geothermal gradients of the Gangdese arc are complied from the literature (Supplementary Data S2). These metamorphic temperature and pressure data were determined through phase equilibrium modeling, while the metamorphic ages were dated by zircon U-Pb method (Supplementary Note S1). To determine the melting/equilibrium depth and temperature of basalt, we begin by filtering basalts with compositions closely resembling that of the primary magma. The selected basalts have high-MgO contents (8.16–14.35 wt.%), Mg# (0.63–0.74), low SiO2 contents (44.16–49.19 wt.%), and ℇNd(t) > 0 (Supplementary Data S3). These basalts have experienced only minor olivine fractional crystallization. Subsequently, we perform back calculation to account for olivine fractionation effects, assuming that Fe3+/FeT = 0.1, KD [(Fe2 + /Mg)ol/(Fe2 + /Mg)melt] = 0.32, and mantle olivine Fo = 0.971. We then employ the resulting reconstructed primary magma compositions, which are in equilibrium with upper mantle, to estimate the melting/equilibrium depths and temperatures following the method of Lee et al.71.

The thermal isostasy is the elevation resulting from lateral variations in temperature and associated thermal expansion or contraction, and can be formulated as:

where T(z) and Tref (z) are the lithospheric geotherms for the observed and reference geotherms integrated from the surface, z = 0, to the point at which the cooler geotherm reaches the mantle adiabat, zmax. The coefficient of thermal expansion, α, is P-T dependent and assumed to be 3.2 × 10−5 K−1 and 3.0 × 10−5 K−1 for the mantle lithosphere and crust, respectively21. By integrating ΔℇT from Eq. (4) across a family of geotherms parameterized by surface heat flow, it becomes possible to construct a thermal isostasy curve, representing the relationship between elevation and heat flow (as shown in Fig. 3b). Applying the thermal isostatic model to 33 tectonic provinces in North America, the best-fitting continental heat flow-elevation model suggests a reference heat flow of 46.6 mWm−2 at zero elevation21.

Numerical modeling

We conduct 2D thermo-mechanical numerical simulations to investigate the process of lower crustal eclogitization and foundering in the orogen and its effects on surface topography, lithosphere temperature, crustal thickness, and mantle melting. Our model is 600 km wide and 300 km high, encompassing a 200 km orogen (Fig. 5). The orogenic crustal thickness is 60 km and gradually reduces to 40 km in the surrounding region. The initial upper crustal thickness is 35 km in the orogen and decreases to 25 km in the surrounding region. The lithosphere thickness tends to increase during the orogeny, similar to crustal thickening. On the other hand, the thickened lithosphere beneath the orogen may trigger Rayleigh-Taylor instability and reduce lithosphere thickness. For simplicity, we set the initial lithosphere thickness beneath both the orogen and the surrounding region to be 100 km (inferred lithosphere thickness at 80 Ma beneath the Gangdese arc, Fig. 3a). The heat production rates in the upper crust, lower crust, and mantle are 1.0, 0.4, and 0.02 μW/m3, respectively37. The initial temperature within the lithosphere is calculated assuming that the lithosphere temperature has reached a steady state. The asthenosphere temperature is set as 1350 °C. The intrinsic (density at 0 °C) densities of the upper and lower crust and mantle are 2.75, 3.00, and 3.35 g/cm3, respectively. The fully eclogitized mafic lower crust density is 3.45 g/cm3. The metamorphism from mafic lower crust to eclogite follows the following phase transition formula that depends on temperature and pressure:

Where Γ is the phase function (the proportion of the mafic rock that has been eclogitized) that varies from zero to one, ρr is the reference density for each depth, (d, T) are rock depth and temperature, (Pph, Tph) is a reference point on the phase boundary between mafic lower crust and eclogite, and γph is the slope of the phase transition boundary. Wph is the phase transition width and is set 10 km in this study. Our setup of mafic lower crust-eclogite metamorphism is similar to the setup of Krystopowicz and Currie72.

Visco-plastic rheology that depends on rock composition, temperature, pressure, strain rate, and deformation history is considered for the rock deformation, similar to our previous studies73,74. The rheological parameters refer to Pérez-Gussinyé et al.75. The top boundary is free-surface76. A 1 cm/year leftward velocity is applied to the lithosphere on the right boundary of the model to simulate the compressional tectonics before the proposed delamination event (Fig. 2). A corresponding outward flow is applied to the bottom boundary to compensate for the influx on the right boundary. The free-slip boundary condition is applied to the left boundary. The top and bottom boundaries are isothermal and have the fixed temperature of 0 and 1350 °C, respectively. The models are performed with the finite element mantle convection software Underworld277.

Data availability

Supplementary Data are available at Mendeley Data (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/6gtybjgj9s/2).

References

Wu, F. et al. Reorganization of Asian climate in relation to Tibetan Plateau uplift. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ.3, 684–700 (2022).

Jepson, G. et al. Climate as the great equalizer of continental-scale erosion. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL095008 (2021).

Clark, M. et al. Surface uplift, tectonics, and erosion of eastern Tibet from large-scale drainage patterns. Tectonics 23, TC1006 (2004).

Ding, W.-N., Ree, R. H., Spicer, R. A. & Xing, Y.-W. Ancient orogenic and monsoon-driven assembly of the world’s richest temperate alpine flora. Science 369, 578–581 (2020).

Gaillardet, J. & Galy, A. Himalaya-carbon sink or source?. Science 320, 1727–1728 (2008).

Ding, L. et al. Timing and mechanisms of Tibetan Plateau uplift. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 652–667 (2022).

Harrison, T. M., Copeland, P., Kidd, W. & Yin, A. Raising tibet. Science 255, 1663–1670 (1992).

Molnar, P., England, P. & Martinod, J. Mantle dynamics, uplift of the Tibetan Plateau, and the Indian monsoon. Rev. Geophys. 31, 357–396 (1993).

Spicer, R. A. et al. Why ‘the uplift of the Tibetan Plateau’ is a myth. Natl. Sci. Rev. 8, nwaa091 (2021).

Tapponnier, P. et al. Oblique stepwise rise and growth of the Tibet Plateau. Science 294, 1671–1677 (2001).

Wang, C. et al. Outward-growth of the Tibetan Plateau during the Cenozoic: a review. Tectonophysics 621, 1–43 (2014).

Ji, W.-Q., Wu, F.-Y., Chung, S.-L. & Liu, C.-Z. The Gangdese magmatic constraints on a latest Cretaceous lithospheric delamination of the Lhasa terrane, southern Tibet. Lithos 210, 168–180 (2014).

Zhu, D.-C., Wang, Q., Chung, S.-L., Cawood, P. A. & Zhao, Z.-D. Gangdese magmatism in southern Tibet and India–Asia convergence since 120 Ma. Geol. Soc. 483, 583-604 (2019).

Zhu, D.-C. et al. Continental crustal growth processes recorded in the Gangdese batholith, southern Tibet. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 51, 155–188 (2023).

Hu, X. et al. The timing of India-Asia collision onset—facts, theories, controversies. Earth Sci. Rev. 160, 264–299 (2016).

DeCelles, P., Kapp, P., Gehrels, G. & Ding, L. Paleocene-Eocene foreland basin evolution in the Himalaya of southern Tibet and Nepal: Implications for the age of initial India-Asia collision. Tectonics 33, 824–849 (2014).

Ding, L. et al. The Andean-type Gangdese mountains: paleoelevation record from the paleocene–eocene Linzhou Basin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 392, 250–264 (2014).

Xu, Q. et al. Late Cretaceous—early Paleogene rise of the Gangdese magmatic arc (south Tibet) from sea level to high mountains. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 135, 1939–1954 (2022).

Zhu, D. C., Wang, Q., Cawood, P. A., Zhao, Z. D. & Mo, X. X. Raising the Gangdese mountains in southern Tibet. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 122, 214–223 (2017).

Kapp, P. et al. The Gangdese retroarc thrust belt revealed. GSA Today 17, 4 (2007).

Hasterok, D. & Chapman, D. S. Continental thermal isostasy: 2. Application to North America. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 112 B06415 (2007).

Sundell, K. E., Laskowski, A. K., Kapp, P., Ducea, M. & Chapman, J. Jurassic to Neogene quantitative crustal thickness estimates in southern Tibet. GSA Today 31, 4–10 (2021).

Tang, M., Ji, W. Q., Chu, X., Wu, A. B. & Chen, C. Reconstructing crustal thickness evolution from europium anomalies in detrital zircons. Geology 49, 76–80 (2021).

Hu, F. Y., Ducea, M. N., Liu, S. W. & Chapman, J. B. Quantifying crustal thickness in continental collisional belts: global perspective and a geologic application. Sci. Rep. 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07849-7 (2017).

Guo, P. & Yang, T. Quantifying continental crust thickness using the machine learning method. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 128, e2022JB025970 (2023).

Chapman, J. B., Ducea, M. N., DeCelles, P. G. & Profeta, L. Tracking changes in crustal thickness during orogenic evolution with Sr/Y: An example from the North American Cordillera. Geology 43, 919–922 (2015).

Luffi, P. & Ducea, M. Chemical mohometry: assessing crustal thickness of ancient orogens using geochemical and isotopic data. Rev. Geophys. 60, e2021RG000753 (2022).

Profeta, L. et al. Quantifying crustal thickness over time in magmatic arcs. Sci. Rep. 5, 17786 (2015).

Ding, H. et al. Late Cretaceous metamorphism and anatexis of the Gangdese magmatic arc, South Tibet: implications for thickening and differentiation of juvenile crust. J. Pet. 63, egac017 (2022).

Niu, Z. et al. Late Cretaceous magmatism and metamorphism records and its tectonic significance of garnet amphibolite from the eastern end of the Gangdese magmatic arc. Yanshi Xuebao 35, 376–386 (2019).

Qin, S.-K. et al. Tectonic burial of sedimentary rocks drives the building of juvenile crust of magmatic arc. Bulletin 134, 3064–3078 (2022).

Zhang, Z., Dong, X., Xiang, H., He, Z. & Liou, J. Metagabbros of the Gangdese arc root, south Tibet: Implications for the growth of continental crust. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 143, 268–284 (2014).

Jiang, Y.-Y., Zhang, Z.-M., Palin, R. M., Ding, H.-X. & Mo, X.-X. Early Cenozoic partial melting of meta-sedimentary rocks of the eastern Gangdese arc, southern Tibet, and its contribution to syn-collisional magmatism. GSA Bull. 134, 179–200 (2022).

Zhang, Z., Dong, X., Xiang, H., Liou, J. & Santosh, M. Building of the deep Gangdese arc, south Tibet: Paleocene plutonism and granulite-facies metamorphism. J. Pet. 54, 2547–2580 (2013).

Artemieva, I. M. Lithosphere structure in Europe from thermal isostasy. Earth Sci. Rev. 188, 454–468 (2019).

Hyndman, R. & Currie, C. Why is the North America Cordillera high? Hot backarcs, thermal isostasy, and mountain belts. Geology 39, 783–786 (2011).

Hasterok, D. & Chapman, D. Heat production and geotherms for the continental lithosphere. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 307, 59–70 (2011).

Elkins-Tanton, L. T. & Foulger, G. Continental magmatism caused by lithospheric delamination. Geol. Soc. Am. 388, 449 (2005).

Currie, B. S. et al. Multiproxy paleoaltimetry of the late Oligocene-Pliocene Oiyug basin, southern Tibet. Am. J. Sci. 316, 401–436 (2016).

Ingalls, M. et al. Paleocene to Pliocene low-latitude, high-elevation basins of southern Tibet: implications for tectonic models of India-Asia collision, Cenozoic climate, and geochemical weathering. GSA Bull. 130, 307–330 (2018).

Watts, A. B. Isostasy and Flexure of the Lithosphere (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Gvirtzman, Z., Faccenna, C. & Becker, T. W. Isostasy, flexure, and dynamic topography. Tectonophysics 683, 255–271 (2016).

Yang, T., Moresi, L., Müller, R. D. & Gurnis, M. Oceanic residual topography agrees with mantle flow predictions at long wavelengths. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 10,896–810,906 (2017).

Flament, N., Gurnis, M. & Müller, R. D. A review of observations and models of dynamic topography. Lithosphere 5, 189–210 (2013).

Pavlis, N. K., Holmes, S. A., Kenyon, S. C. & Factor, J. K. The development and evaluation of the Earth Gravitational Model 2008 (EGM2008). J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 117 (2012).

Xia, B., Artemieva, I., Thybo, H. & Klemperer, S. Strong variability in the thermal structure of Tibetan Lithosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 128, e2022JB026213 (2023).

Lee, C.-T. A., Thurner, S., Paterson, S. & Cao, W. The rise and fall of continental arcs: interplays between magmatism, uplift, weathering, and climate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 425, 105–119 (2015).

Bai, Z., Zhang, S. & Braitenberg, C. Crustal density structure from 3D gravity modeling beneath Himalaya and Lhasa blocks, Tibet. J. Asian Earth Sci. 78, 301–317 (2013).

Jagoutz, O. & Behn, M. D. Foundering of lower island-arc crust as an explanation for the origin of the continental Moho. Nature 504, 131–134 (2013).

Xu, W. et al. Constructing the early Mesozoic Gangdese crust in southern Tibet by hornblende-dominated magmatic differentiation. J. Pet. 60, 515–552 (2019).

Ducea, M. N. & Saleeby, J. B. Buoyancy sources for a large, unrooted mountain range, the Sierra Nevada, California: Evidence from xenolith thermobarometry. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 101, 8229–8244 (1996).

Lee, C.-T. A., Cheng, X. & Horodyskyj, U. The development and refinement of continental arcs by primary basaltic magmatism, garnet pyroxenite accumulation, basaltic recharge and delamination: insights from the Sierra Nevada, California. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 151, 222–242 (2006).

Jagoutz, O. & Schmidt, M. W. The composition of the foundered complement to the continental crust and a re-evaluation of fluxes in arcs. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 371, 177–190 (2013).

Liu, A.-L. et al. Temporal and spatial variations of enriched source components in Linzizong volcanic succession, Tibet, and implications for the India–Asia collision. J. Pet. 63, egab103 (2022).

Lee, H.-Y. et al. Geochemical and Sr–Nd isotopic constraints on the genesis of the Cenozoic Linzizong volcanic successions, southern Tibet. J. Asian Earth Sci. 53, 96–114 (2012).

Zhang, S.-H., Ji, W.-Q., Chen, H.-B., Kirstein, L. A. & Wu, F.-Y. Linking rapid eruption of the Linzizong volcanic rocks and Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (EECO): constraints from the Pana Formation in the Linzhou and Pangduo basins, southern Tibet. Lithos 446, 107159 (2023).

Huang, F., Rooney, T. O., Xu, J.-F. & Zeng, Y.-C. Magmatic record of continuous Neo-Tethyan subduction after initial India-Asia collision in the central part of southern Tibet. Bulletin 133, 1600–1612 (2021).

Gao, Y., Wei, R., Hou, Z., Tian, S. & Zhao, R. Eocene high-MgO volcanism in southern Tibet: new constraints for mantle source characteristics and deep processes. Lithos 105, 63–72 (2008).

Wang, G., Thybo, H. & Artemieva, I. M. No mafic layer in 80 km thick Tibetan crust. Nat. Commun. 12, 1069 (2021).

Ji, W.-Q. et al. Eocene Neo-Tethyan slab breakoff constrained by 45 Ma oceanic island basalt–type magmatism in southern Tibet. Geology 44, 283–286 (2016).

Zhu, D.-C. et al. Magmatic record of India-Asia collision. Sci. Rep.5, 14289 (2015).

Kapp, P. & DeCelles, P. G. Mesozoic–Cenozoic geological evolution of the Himalayan-Tibetan orogen and working tectonic hypotheses. Am. J. Sci. 319, 159–254 (2019).

Xu, W.-C., Zhang, H.-F., Harris, N., Guo, L. & Pan, F.-B. Rapid Eocene erosion, sedimentation and burial in the eastern Himalayan syntaxis and its geodynamic significance. Gondwana Res. 23, 715–725 (2013).

Chung, S.-L. et al. Adakites from continental collision zones: melting of thickened lower crust beneath southern Tibet. Geology 31, 1021–1024 (2003).

Hou, Z.-Q., Gao, Y.-F., Qu, X.-M., Rui, Z.-Y. & Mo, X.-X. Origin of adakitic intrusives generated during mid-Miocene east–west extension in southern Tibet. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 220, 139–155 (2004).

Ji, W.-Q. et al. Pervasive Miocene melting of thickened crust from the Lhasa terrane to Himalaya, southern Tibet and its constraint on generation of Himalayan leucogranite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 278, 137–156 (2020).

Williams, H., Turner, S., Kelley, S. & Harris, N. Age and composition of dikes in Southern Tibet: New constraints on the timing of east-west extension and its relationship to postcollisional volcanism. Geology 29, 339–342 (2001).

Chung, S.-L. et al. Tibetan tectonic evolution inferred from spatial and temporal variations in post-collisional magmatism. Earth Sci. Rev. 68, 173–196 (2005).

Currie, B. S., Rowley, D. B. & Tabor, N. J. Middle Miocene paleoaltimetry of southern Tibet: Implications for the role of mantle thickening and delamination in the Himalayan orogen. Geology 33, 181–184 (2005).

Xu, Q., Li, S. & Bai, Y. Modern-like elevation and climate in Tibet since the mid-Miocene (ca. 15 Ma). GSA Bull. 134, 2561–2575 (2022).

Lee, C.-T. A., Luffi, P., Plank, T., Dalton, H. & Leeman, W. P. Constraints on the depths and temperatures of basaltic magma generation on Earth and other terrestrial planets using new thermobarometers for mafic magmas. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 279, 20–33 (2009).

Krystopowicz, N. J. & Currie, C. A. Crustal eclogitization and lithosphere delamination in orogens. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 361, 195–207 (2013).

Yang, T., Liu, S., Guo, P., Leng, W. & Yang, A. Yanshanian orogeny during North China’s drifting away from the trench: implications of numerical models. Tectonics 39, e2020TC006350 (2020).

Zhao, J.-H., Yang, T. & Wang, W. Orogenic belt resulting from ocean-continent collision. Geology 50, 1266–1269 (2022).

Pérez-Gussinyé, M. et al. Lithospheric strength and rift migration controls on synrift stratigraphy and breakup unconformities at rifted margins: Examples from numerical models, the Atlantic and South China Sea margins. Tectonics 39, e2020TC006255 (2020).

Deng, L., Yang, T., Zhao, Z. & Zhou, M. Constraining subducting slab viscosity with topography and gravity fields in free-surface mantle convection models. Tectonophysics 871, 230195 (2024).

Mansour, J. A. et al. Underworld2: Python geodynamics modelling for desktop, HPC and cloud (2020).

Laske, G., Masters, G., Ma, Z. & Pasyanos, M. Update on CRUST1.0 — A 1‐degree global model of Earth’s crust. Geophys. Res. Abstr. 15, 2658 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This study exclusively uses rock sample data compiled from previously published literature. No specific permissions were required. We thank the editors David Hernández Uribe and Joe Aslin, Gilby Jepson, and one anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments and suggestions. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92355301, 42174105, 42350710792) and the Shenzhen Stable Support Plan Program for High Education Institutions (20220815130733001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.G.: writing—original draft, visualization, conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation. T.Y.: writing—review and editing, conceptualization, visualization, supervision, funding acquisition. W.L.X.: writing—review and editing. W.Q.J.: writing—review and editing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks John He and Gilby Jepson for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: David Hernández Uribe and Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, P., Yang, T., Xu, WL. et al. Lower crustal foundering drove the uplift of southern Tibet during the Paleocene. Commun Earth Environ 6, 343 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02269-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02269-2