Abstract

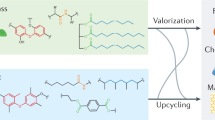

As the demand for single-use plastics rises, sustainable plastic management has become a pressing concern. Transforming plastic waste into value-added fuels is a promising waste-to-energy strategy that benefits environmental and energy security. In recent years, biochar-based catalysts (BBCs) have attracted increasing attention for their cost-effectiveness, well-developed pore structure, and effective surface functional groups in catalytic conversions of plastic waste into fuels. Many researchers have documented the successful utilization of biochar catalysts for efficient plastic waste valorization. However, a systematic review of biochar-based catalytic valorization of plastic waste into useful fuels is still missing. We assessed practical applications of biochar-based catalytic pyrolysis and advanced oxidation technologies, evaluating their performance from life-cycle and techno-economic perspectives. Machine learning was also introduced to design high-performance BBCs and optimize the plastic upcycling system. This eco-friendly innovation supports several UN SDGs and provides valuable insights for the UN Treaty on Plastic Pollution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scale and complexity of plastic waste worldwide

Plastics, or polymeric materials, possess good plasticity and excellent strength, along with low density, conductivity, high transparency, and stability, rendering them suitable for a wide range of day-to-day and industrial applications1. As the world population increases, global plastic consumption is rising at an average annual rate of 10%, resulting in a circa 1.5 million tons increase in plastic waste annually2. Estimates project that global plastic production will reach approximately 1.1 billion tons in 2050. However, less than 10% of the plastics are recycled, with the majority being incinerated, deposited in landfills, or dumped into the environment3 (Fig. 1a). Various natural mechanisms contribute to plastic degradation, including autoxidation, photodegradation, thermal degradation, biodegradation, and thermal oxidation, but these mechanisms are progressing at an exceedingly sluggish pace.

a Waste management techniques for plastic materials3, b sources, components, and applications of plastics waste, and c publication and citation trends of biochar catalysts for plastic to fuels based on Web of Science Core Data Collection (accessed on June 19th, 2024).

This surge in plastic waste has detrimental effects on the biodiversity of fresh and marine ecosystems. Plastics can persist in the ecosystem for an extended period, significantly impacting the survival of terrestrial and marine life and posing substantial challenges to the environment4,5,6. Additionally, microplastics (particle size <5 mm), are a family of plastics of particular concern. These components are generated through processes such as artificial fabric cleaning, tire abrasion, paint degradation, and the breakdown of microbeads from personal care products and plastic waste7. Nowadays, microplastics are not only present in soil, water sources, and air, but also in marine life, salt, beer, and most recently, in bottled drinking water worldwide8,9,10. Plastic waste is widely considered an environmental threat because it can be subconsciously consumed or ingested by living creatures11, leading to potential accumulation in human tissues and body parts12. This accumulation poses risks by altering the immune system or inflicting several clinical complications13,14,15. Hence, the sustainable management of plastic waste is recognized as a both challenging and pressing issue.

Sources and treatments of plastic waste

Based on typical classification (Fig. 1b), plastic waste is broadly categorized into low-density polyethylene (LDPE), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC)16. Considering the sources of generation, plastic waste is classified as municipal, commercial, industrial, agricultural, construction, and deconstruction waste, etc. For instance, beverage bottles and films (e.g., carryout bags and wrappers) make up the bulk of municipal waste, while agricultural, construction, and demolition wastes may include large plastic containers and PVC pipes. Compositionally, municipal wastes containing 10 wt.% plastic are not equivalent to the same amount of construction and demolition wastes, thus distinct sorting and disposal strategies are needed to handle various plastic-containing waste streams. Microplastic pollution could emerge as a secondary pollution of prevalent plastic waste disposal strategies (landfill, incineration, and recycling) since they are inept in removing microplastics17.

Plastic persists in the environment for decades or even centuries due to its unique chemical structure. Most plastic waste is resistant to natural degradation, earning the title of non-biodegradable plastics. Plastic pollution mitigation has garnered global attention, and plastic waste treatment technologies comprising recycling and degradation strategies have also developed rapidly in recent years18. Recycling technologies are further classified into three categories: physical recycling, energy recovery, and resource recovery. Despite simple recycling methods such as thermal recycling reducing the accumulated plastic waste, they release microplastics into water and soil, thereby infiltrating the food chain and deteriorating human health. Additionally, these methods require significant investment in terms of money, energy, and labor19. Biodegradation and oxo-biodegradation represent two main methods commonly used in degradation technologies. Oxo-biodegradation includes abiotic and biotic processes, and abiotic processes could be driven by photodegradation, thermal degradation, and mechanochemical degradation20. Despite extensive research and development efforts on plastic waste treatment, achieving a circular economy remains challenging due to the low value of the products21,22. Given the urgent need for alternative energy sources, there is a pressing demand for developing promising treatment technologies, which are capable of catalyzing the conversion of plastic waste into high-quality energy23,24,25. Several techniques, such as gasification, pyrolysis26,27,28, pyrolysis/hydrotreatment, hydrothermal liquefaction, solvolysis, and catalytic hydroconversion29,30, have been developed in this regard.

Chemical upcycling reactions are performed using the catalysts, enabling the selective production of target products under complex conditions (e.g., mixtures of tainted plastics and plastic wastes) via the rational design of these catalysts, which has been actively studied recently. Thus, the present practical challenge hindering the industrial deployment of thermochemical processes for plastic waste management lies in developing and preparing catalysts that exhibit both high activity and stability31,32. Biomass-derived catalysts are applauded as green catalysts, typically being inexpensive, sustainable, reusable, and environmentally benign33,34. They are frequently employed in polymer cracking by virtue of their high specific surface area, abundant surface inorganic groups (i.e., K and Fe), and the presence of other functional groups that aid in adsorbing metal precursors35,36,37,38. Numerous studies have demonstrated that publication and citation trends of biochar catalysts for plastic to fuels are significantly increasing, especially over the last 5 years (Fig. 1c). Compared to other catalysts, the benefits of BBCs are facile synthesis, cost-effectiveness, reusability, and a substantial contribution to enhancing biofuel production. Therefore, the catalytic conversion of plastic waste into fuels using biochar as a catalyst is not only beneficial for increasing plastic fuel yields but also for mitigating environmental problems in the catalytic conversion process, such as the generation of microplastics. Thus, it contributes to the development of effective sustainable management strategies for plastic waste.

Recent progress in catalytic conversions of plastic waste into fuels

A variety of methods, such as mechanical, biological, thermal, and chemical recycling, are employed to address environmental pollution arising from excessive plastic waste. Simple heating or the incorporation of chemical additives is frequently preferred for converting plastic waste into value-added liquid fuels, considering its potential applications and economic feasibility. The catalytic conversions used in plastic waste management are heterogeneous catalysis, homogeneous catalysis, and biocatalysis. Homogeneous catalysts are difficult to separate and recover, which limits their practical use in industrial applications. Heterogeneous catalysis has many advantages, such as easy separation and reuse. Therefore, it has attracted much attention in the field of plastic catalytic conversion. At present, researchers are focusing on the development of efficient and stable heterogeneous catalysts to improve both the efficiency and selectivity of plastic catalytic conversion. In addition, biocatalysis has unique advantages in the breakdown of biodegradable plastics and bio-based plastics. However, the stability, activity, and production cost of biocatalysts still need to be further studied and improved.

Heterogeneous catalysis

Heterogeneous catalysis is widely used to promote the conversion of plastic waste into combustible gases or liquid fuels, such as pyrolysis, hydrocracking, dehydrochlorination, and gasification. The advantages of heterogeneous catalysis are summarized as follows: (1) catalysts are easily separated from liquid products due to they are in different phases, thus enabling catalyst recovery effectively and practically, (2) heterogeneous catalysts are usually highly adaptable to different reaction systems and feedstocks and are widely applied to a wide range of chemical reactions, and (3) most heterogeneous catalysts have good stability at high temperatures, high pressures, or long residence times, and are not prone to activity loss or degradation. However, heterogeneous catalysis also has some disadvantages: (1) small contact area and relatively slow reaction rate because the catalyst and reactants are not in the same phase, (2) the poor structural match between heterogeneous catalysts and reactants is not conducive to the formation or breaking of specific chemical bonds, and (3) some heterogeneous catalysts are more complex to prepare, resulting in higher costs.

Pyrolysis

In an inert atmosphere and at high temperatures (i.e. up to 900 °C), pyrolysis converts plastic waste into gas, liquid hydrocarbons, and biochar, which can be used as fuels for various applications or industrial raw materials39. This process has the advantages of minimizing investment costs and reducing waste production. However, it comes with the typical drawback of requiring relatively high operating temperatures (i.e., 550–900 °C)40,41,42. To efficiently reduce energy consumption and effectively mitigate the coke formation during pyrolysis of plastic waste needs to be further scrutinized, which would be beneficial to accelerating its commercial application.

Pyrolysis is often divided into thermal pyrolysis, catalytic pyrolysis, and co-pyrolysis. Compared to non-catalytic pyrolysis, the addition of catalysts generally reduces the operating temperature of plastic pyrolysis, shortens the degradation time, and narrows the product yield distribution of plastic waste. Both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts are widely used in plastic pyrolysis. As shown in Table 1, homogeneous catalysts are dissolved in reactants or solvents during the pyrolysis, such as AlCl3, FeCl3, and TiCl3. The heterogeneous catalysts are the most used because the liquid products can be easily separated from solid catalysts (i.e., nanocrystalline zeolites, conventional acid solids, mesostructured catalysts, metals, and metal oxides supported on carbon). During the pyrolysis of plastic waste, the kinetics and mechanisms of plastic waste degradation change with the catalyst loading variations. Sanchez et al.43 studied the differences between pyrolysis and catalytic pyrolysis of various plastic wastes and real mixtures using different catalysts (i.e., CaO, MgO, HY, HZSM-5) in a fixed-bed reactor, and concluded that the role of polymer type has a significant impact on the yields of gaseous, liquid, and solid products. The addition of a catalyst to the plastics pyrolysis process can affect the distribution and yield of the product, depending on the type of catalyst, the reaction conditions and the nature of the plastic44.

Cracking reaction rates typically increase due to the use of catalysts, resulting in high yields of gaseous products and low yields of liquid oil. As the catalysts further catalyze the decomposition of bulky compounds with long carbon chains, the carbon number distribution becomes narrower and the octane number increases. It is vital to probe the catalytic performances and mechanisms of plastic pyrolysis using different catalysts. Catalytic plastic pyrolysis greatly improves the recovery efficiencies from plastic waste, mitigates plastic pollution, and achieves a circular plastic economy. However, the use of catalysts increases the processing investment due to their inherent drawbacks, including shorter lifespan and poor stability caused by deactivation45. This is one of the critical issues that need to be addressed for efficient catalytic pyrolysis of plastic waste and its conversion into value-added liquid fuels.

Hydrocracking

Hydrocracking or hydrogenation breaks down long-chain hydrocarbons (i.e., gasoline and kerosene) into smaller molecules under high pressure using a catalyst in a hydrogen atmosphere29. Plastic hydrocracking proves to be efficient in the production of aromatic products while reducing heteroatom contents, thereby improving the quality of main products.

Cracking is a heat-absorbing reaction, while hydrogenation is exothermic, so the two reactions are complementary to each other. High hydrogen partial pressures are necessary to inhibit undesired coke formation or repolymerization reaction. Despite thermal hydrocracking could occur without catalysts, the catalysts facilitate the incorporation of hydrogen. Cracking and dehydrogenation functions are crucial for catalysts added to plastic waste hydrocracking processes. Hydrocracking catalysts should have metal-containing acidic carriers for cracking and isomerization reactions, and the metal supported on the carrier undergoes hydrogen dehydrogenation. The typical materials used as acidic carriers are amorphous oxides (i.e., silica-alumina), crystalline zeolite (i.e., HZSM-5), strong solid acid (i.e., sulfated zirconium oxide), or the combinations of these materials. The supporting metal may be a precious metal (palladium or platinum) or a non-noble metal in the periodic table group VI-B (molybdenum or tungsten) and VIII (cobalt or nickel)46. In addition, hydrogen stream is indispensable in the hydrocracking process, although it is more costly than other gases, such as nitrogen used for fluidization in pyrolysis. Hydrocracking is less mature than pyrolysis because high-pressure operating conditions make it more expensive47.

Dehydrochlorination

The pyrolysis of mixed plastic waste (MPW), especially when containing PVC, produces organochlorine compounds. For example, during the pyrolysis of polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a substitution reaction occurs between chlorine and hydrogen atoms, resulting in the formation of conjugated double bonds in the liquid product. PVC releases polar HCl molecules, which subsequently attack the double-bonded compounds in PVC. This attack leads to the formation of organochlorine compounds that can pose critical issues when oil extracted from MPW is used to produce gasoline or used directly as fuel oil in catalytic cracking. These organic chlorine compounds not only possess strong corrosive properties, but severely erode and poison refining equipment and catalysts, thereby affecting their activity and service life, reducing the efficiency of the refining process, and increasing maintenance costs. Furthermore, these compounds can also affect the quality of final products, such as gasoline, causing them to produce corrosive substances like hydrogen chloride when burned, damaging components of automotive engines and even posing a threat to the safe operation of vehicles. In addition, the emission of organic chlorine compounds can cause severe environmental pollution. Their accumulation in the atmosphere may lead to environmental issues such as acid rain, causing long-term ecological damage to soil and water bodies48.

Therefore, the organochlorine compounds need to be removed from MPW-derived liquid oils before refining treatment. Compared with other methods (i.e., incineration), dechlorination using a catalyst is one of the preferred methods for removing dechlorinated compounds, as it does not form toxic compounds. Various dehydrogenation catalysts (i.e., iron oxide, iron oxide-carbon composite, ZnO, MgO, and red mud) are proven to be effective for the dehydrogenation of organochlorine compounds49.

In addition, ionic liquid (IL)-mediated dechlorination has been considered an effective and practical route, mainly due to its low operating temperature (<200 °C) and effective HCl removal (~90%)50,51. The different components of the composite material can be effectively separated, thus simplifying further processing in terms of recycling. The dechlorination of PVC also eases its further recycling. This suggests that the application of ILs to the recycling of MPW is an effective and practical route, especially for MPW mixed with PVC.

Gasification

Gasification, a typical process of thermochemical technology dating from the 1970s, focuses on the conversion of carbonaceous materials into high-quality syngas (i.e., CO and H2) at high operating temperatures (i.e., up to 1200 °C)52. To expand its applications in the thermochemical conversion of non-biodegradable plastic waste, it is imperative to overcome the problems of high-quality equipment requirements and large investments associated with high gasification temperatures. Compared to precious metals (i.e., Rh and Ru), Ni is more active and cost-effective in catalytic gasification. However, during the catalytic gasification, excess coke deposits formed on the catalyst surface along with the sintering, can block the active sites and reduce the catalytic activity. To ameliorate the catalytic performance of Ni-based catalysts, doping metal accelerators (i.e., Cr, Mo, and W) to form bimetallic catalysts is often conducive to the synthesis of high-stability catalyst, which not only enhances the metal-support interaction and coking resistance but also reduces the likelihood of poisoning53. This improvement is due to the synergistic effect between the two metals, which alters the electron density of the catalyst, affects adsorption or chemical reactions, or enhances the textural properties.

Homogeneous catalysis

Homogeneous catalysis is used to promote the breaking and restructuring of polymer chains in plastic waste to produce lower molecular weight hydrocarbons or other fuels. Glycolysis, methanolysis, and aminolysis represent the three main methods of homogeneous catalysis. The advantages of homogeneous catalysis are summarized as follows: (1) since the catalyst and reactants are in the same phase, they can be fully mixed and contacted, thus greatly accelerating the reaction rate, (2) homogeneous catalysts typically achieve higher conversions, thus enhancing the efficiency of chemical reactions and product yields, and (3) homogeneous catalysts and reactant are structurally compatible to favor formation or fracture of specific chemical bonds. However, homogeneous catalysis also has some disadvantages: (1) due to the catalyst and reactant being in the same phase, it is difficult to separate the product from the catalyst after the reaction, rendering it difficult to recover and reuse the catalyst, (2) homogeneous catalysts are often only suitable for specific reaction systems and raw materials, lacking adaptability to other systems and raw materials, and (3) some homogeneous catalysts have poor stability when subjected to high temperature, high pressure or long periods, and are prone to activity loss or degradation.

Glycolysis

Glycolysis is a method for depolymerizing polymers containing ethylene glycol (i.e., glycol and diethylene glycol) in the reaction, which has been recognized as a commercialized PET recovery method (e.g., DuPont, DOW) worldwide54. Glycolysis has received more attention because of its mild reaction conditions, low solvent volatility, and high feasibility of continuous production. Different from ILs, deep-eutectic solvents, and nanomaterials, the synthesis steps for organometallic catalytic processes are simple and easy to implement. Initially, organometallic catalysts (e.g., zinc or magnesium acetate, sodium/potassium sulfate, and titanium phosphate) with high stability and reactivity are used for PET glycolysis; but these catalysts potentially contribute to heavy metal contamination, which leads to additional environmental and economic burdens. As the green alternatives to traditional organometallic complexes, the organic catalysts are preferably applied in the polymer depolymerization.

The organic catalysts are mainly classified into cationic, anionic, and neutral types, which interact with PET molecules through different mechanisms. Taking aluminum ion as an example, cationic catalysts interact with the negative charge portions of PET molecules (such as oxygen atoms in the ester groups) through their positive charges, significantly reducing the energy barrier for PET molecular chain breakage. On the other hand, anionic catalysts, represented by hydroxide ions, utilize their negative charges to interact with the positive charge portions of PET molecules (such as carbon atoms in the ester groups), also promoting the degradation process of PET. Furthermore, neutral ion catalysts like cuprous oxide accelerate PET degradation by forming coordination bonds with ester groups in PET molecules. These specific examples demonstrate the practical applications and mechanisms of different types of organic catalysts in glycolysis, collectively enhancing the efficiency of PET recycling.

Methanolysis

Hofmann et al.54 successfully employed microwave heating strategy to degrade daily-use end-of-life poly(lactic acid) (EoL-PLA) to methyl lactate. It was achieved through selective depolymerization and degradation of discarded EoL-PLA plastics. The process involved methanol cracking, facilitated by the addition of an industrially relevant catalyst, tin 2-ethylhexanoate (Sn(Oct)2). The main PET methanol decomposition products are dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) and ethylene glycol. To improve the efficiency of plastic methanolysis, it is both necessary and urgent to develop catalysts with high catalytic activity, high stability, and easy separability. Tang et al.55 reported that the use of MgO/NaY as a PET methanolysis catalyst effectively promotes the chemical recovery of PET. The yield of DMT and supercritical methanolysis of PET were significantly improved by the addition of carbon dioxide (CO2), and the maximum DMT yield was up to 95%. In addition, the supercritical methanolysis of PET was improved by the addition of 1.5 MPa carbon dioxide, which reduced the reaction temperature, the amount of solvent methanol required, and the energy consumption of the reaction56.

Aminolysis

Amines are more reactive nucleophiles than alcohols and can react rapidly with ester functional groups. Therefore, employing the amino alcohols as an alternative has two main advantages: (1) reactions with amines have better chemo-selectivity compared to alcohol functionalities (which require more energy and catalyst to produce esters), (2) the presence of two terminal alcohol functional groups contributes to the formation of the central portion of terephthalate. The rigidity of the molecule is improved due to the aromatic ring situated next to the amide function, thus creating a strong H-bonding interaction in secoamides. Due to the high chemical stability and low solubility of PET in organic solvents, the depolymerization process usually needs harsh conditions and heat-resistant organometallic catalysts (i.e., zinc, cobalt, or lead). Lately, several organocatalysts have been found effective in the depolymerization of PET with amines, among which 1,5,7-triazabicyclo [4.4.0] dec-5-ene (TBD) is one of the most effective catalysts. The depolymerization process of PET waste is more efficient when using equimolar mixtures of amino alcohols and acid-based ions as the catalysts, particularly (1) triazabicyclodecene (TBD) and methanesulfonic acid or (2) 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) and benzoic acid57.

Biocatalysis

Biocatalysis using microorganisms to recycle material has become a common alternative method to previously established methods58. The key points for the success of biocatalysis are the improvement of bioengineering techniques and the discovery of novel microorganisms and enzymes with high degradation ability.

The advantages of biocatalysis are detailed as follows: (1) biocatalysis can catalyze reactions at mild conditions (room temperature and pressure), which results in lower energy consumption and reduced equipment requirements than chemical catalysis (high temperatures or pressures), (2) biocatalysts have strong catalytic specificity and can selectively catalyze specific chemical reactions, which helps to obtain high-purity products, and (3) biocatalysis processes produce less waste and has a lower environmental impact. However, there are also setbacks of biocatalysis: (1) biocatalysts, especially enzymes, are sensitive to environmental factors such as temperature and pH, resulting in poor stability and potential loss of catalytic activity, (2) biocatalysts are vulnerable to several interferences from chemical substances and miscellaneous bacteria, which may upset catalytic performance, (3) the high production cost of the biocatalysts may limit the overall economic benefit, (4) the biocatalysis reactions require precise controlled conditions such as temperature and pH, and (5) biocatalytic products and substrates are often mixed in solution and difficult to separate.

Cutinase enzymes

The Cutinase enzyme has demonstrated remarkable capabilities in the process of plastic degradation59,60. Taking polyethylene terephthalate (PET) as an example, this material, widely used in plastic bottles, fibers, and packaging, is difficult to degrade naturally, causing long-term environmental pollution. However, the emergence of the Cutinase enzyme provides a solution to this problem. Through its unique catalytic mechanism, the Cutinase enzyme can recognize the ester bonds in PET molecular chains and precisely hydrolyze them into terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol monomers. This decomposition process can be carried out under relatively mild conditions, without the need for extreme conditions such as high temperature or high pressure, which not only reduces energy consumption but also minimizes the generation of pollutants.

Moreover, the Cutinase enzyme exhibits the ability to degrade various polyester materials, including polycaprolactone (PCL). These polyester materials are also widely used in industrial production, but their non-degradability poses significant pressure on the environment. The broad substrate specificity of the Cutinase enzyme enables it to act on multiple polyester materials simultaneously, greatly improving the efficiency and feasibility of plastic degradation.

In recent years, with the in-depth research on the Cutinase enzyme, its application prospects have become increasingly broad. Taking the research conducted by Kyoto University in Japan as an example, they successfully isolated the Cutinase enzyme from a bacterium called “Ideonella sakaiensis” that can efficiently degrade PET. This enzyme can decompose PET plastic bottles into monomers within just a few weeks, providing strong support for plastic recycling and reuse. In addition, researchers have modified the enzyme-producing microorganisms through genetic engineering techniques to enable them to express the Cutinase enzyme in large quantities, further improving degradation efficiency.

Other biocatalysts

In addition to Cutinase enzymes, many other enzymes of microbial origin have the potential to degrade plastics. These enzymes may have specific substrate specificity and can recognize and hydrolyze different types of plastic polymers. PET is one of the most widely produced plastics. Nowadays, the large accumulation of polyester waste in the environment becomes a serious threat to the ecosystem. An effective method of PET pollution mitigation is to depolymerize PET using PET hydrolytic enzymes. Therefore, developing more efficient enzymes is essential to achieve this goal61. In the last few years, many researchers have found, characterized, and engineered enzymes with PET degradation activity. To date, over 24 different types of enzymes that have the characteristics of PET degradation were identified, including hydrolases that can promote the breakdown of PET polymer into TPA, ethylene glycol, BHET, and (mono-(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalic acid (MHET). By real-time non-invasive analysis of biocatalytic PET degradation, Frank et al.62 showcased the effectiveness of polyester hydrolase PHL7 and LCC. Despite possible enzymatic degradation of PET, PET depolymerization rate is theoretically enhanced at higher reaction temperatures, so it is urgent to search for thermophilic PET hydrolases with higher heat resistance. The most effective PET hydrolase discovered is called Isophthaloyl-CoA Carboxylase/Geranylgeranyl Diphosphate Synthase (ICCG), which is a heat-resistant catalase derived from leaf and branch compost. Starting from the investigation of the crystal structure of ICCG enzyme and its complex with the PET degradation intermediate MHET, Zeng et al.63 successfully engineered ICCG through structure-based design, obtaining variants with higher activity at temperatures up to 90 °C. These variants not only enhance the decomposition properties of low-crystallinity PET but also strengthen the potential for PET material recycling and reuse.

In the field of plastic degradation, although some enzymes show great potential, further improvements in their activity and thermal stability, especially for degrading difficult-to-degrade materials like PET, are still necessary for effective industrial applications. Through systematic mutagenesis studies, we can explore new variants of these enzymes, enhance their degradation performance, and ultimately promote their use in the field of plastic recycling.

Biochar-based catalysts in catalytic plastic transformation

Currently, common commercial catalysts used in the field of converting plastic waste into fuels include zeolite catalysts (such as ZSM-5), metal oxide catalysts (such as V2O5 and Fe2O3), noble metal catalysts (such as Pt and Pd), and activated carbon catalysts. These catalysts are widely used due to their high catalytic performance and mature technologies, but they also face issues such as high costs, limited resources, high energy consumption during production, and susceptibility to coking and deactivation. In contrast, the use of biochar as a catalyst offers several merits, specifically its feasible production from low-cost, readily available biomass resources, and its mitigation of adverse environmental impacts caused by biomass mismanagement64,65. The BBCs are thermally and mechanically stable, chemically inert, and biodegradable. In addition, it improves metal-carrier interactions between metal and carbon by templating, chemical activation, metal impregnation, or heteroatom doping66. It is regenerative, inexpensive, and adaptable for continued effective operation at high temperatures. Therefore, compared to expensive metal catalysts, biochar is a lower-cost and more sustainable catalytic material67, making them a strong alternative to traditional commercial catalysts.

Activation and modification of biochar-based catalysts

Biochar is a low-cost carbon-based solid residue that is typically derived from pyrolysis or gasification of various renewable biomass wastes, such as sludge, manure, food waste, agricultural waste, and forestry waste68. Biochar is widely developed as a catalyst or catalyst support by high porosity, large specific surface area, long-term stability, good coking resistance, and rich surface functional groups. Hydrochar is obtained by biomass hydrothermal carbonization, but hydrochar is classified under biochar since it requires post-functionalization steps to synthesize high-performance catalysts. The process of upcycling plastic waste to hydrocarbons over carbon-based catalysts has been studied. González et al.69 showed that the activated carbon (AC) outperformed silica and molecular sieve in catalytic polyethylene pyrolysis. AC’s surface functional groups (i.e., carboxyl groups) could promote the oligomerization, decarbonylation, and decarboxylation of polyethylene. Without activation, the carbon-based catalysts had insufficient catalytic activity, which limited the pyrolytic formation of light oil distillate and left wax as the main product.

Physical activation, chemical activation, and/or functionalization are widely used to increase the physicochemical properties (e.g., specific surface area (SSA), surface functional groups, and acidity), which are beneficial for better catalytic pyrolysis performance. In addition, BBCs have the potential to replace traditional catalysts due to their sustainability and cost-effectiveness70. Compared to unprocessed biochar, activated or modified biochar has further improved properties with larger SSA, more developed porosity, and more active sites or functional groups. There is no strict distinction between activation and modification as they both aim to improve the characteristics of raw biochar. This review introduces the activation methods (physical activation and chemical activation) and modification methods (metal modification and non-metal modification) of biochar (Fig. 2a).

a Activation, modification methods and related parameters of BBCs, b pore structure of biochar during co-pyrolysis72, c metal-doped mesoporous biochar catalysts74, d effect of different feeding ratios on the product75, e variation of raw peak counts of various products with the pyrolysis temperature81, and f training flow of machine learning models and optimization via cross-validation and hyper-parameters97. (Reprinted with permission from refs. 72,74,75,81).

The pore structure of biochar catalysts is vital for their catalytic performances, which is the main regulating characteristic of physical activation71. For catalytic fast co-pyrolysis of Douglas fir and low-density polyethylene (LDPE), Lin et al.72 synthesized four types of ACs via physical (steam) and chemical (phosphoric acid; H3PO4) activations. Experiments have proven that steam-activated AC catalysts preserved the original skeleton structure, while the H3PO4-activated AC catalysts developed new pore structures due to the reaction between phosphoric acid and biomass fragments. Considering highly porous structure and P-containing functional groups, the H3PO4-activated AC catalysts catalyzed the co-pyrolysis with high efficiency and stability (Fig. 2b).

Commonly, CO2 and steam are mostly used for physical activation to develop pore structures well. For example, the pore formation during CO2 activation for biochar is a three-step process. The first step is to open the pores that are formed during carbonization but are clogged by carbon atoms and heteroatoms in a disordered manner; the second step is to further widen, permeate and deepen the opened pores. The third step is to form new pores. In contrast to CO2 activation, the microporous structure of carbon materials is directly expanded by steam activation through pore expansion instead of the pore opening process mentioned in the first step above. In summary, the physical activation process has the advantages of simple operation, low amount of chemical solvent, and less liquid phase contamination. The final AC product is characterized by high SSA and well-developed pore structures, but its limitations are the long activation time and high energy consumption73.

The chemical activation shortens activation time and reduces energy consumption for biochar activation. From catalytic pyrolysis of mixed plastics for the production of aromatic oils, Sun et al.74 revealed the role and the possible dominant catalytic mechanism of biochar and chemical-activated AC catalysts using various chemical agents. The Olefin content of the oil was increased after adding biochar to the pyrolysis of plastic waste. After the activation of ZnCl2, KOH, and H3PO4, the aromatic selectivity of chemical-activated AC was high, with the respective aromatic proportion of 47.6%, 44.7% and 66.0%. KOH-activated AC had enriched C=O groups and low metal content, which could promote the hydrogen transfer reaction of alkenes to form alkanes and aromatics. Meanwhile, ZnCl2- and H3PO4-activated AC had enriched Lewis acid site and Brønsted acid site, which favored aromatization process for higher aromatic yield (Fig. 2c)74. Primary detrimental drawback of chemical activation was secondary pollution (i.e., heavy metal pollution and wastewater generation) that arising from chemical usage and washing treatment of AC.

Based on the presence or absence of metal, biochar modification is categorized into metal modification and non-metal modification. Metal-modified biochar refers to the biochar loaded with metal monomers or metal oxides, aiming to introduce active sites on its surface improving the catalytic performance. The two main methods of metal modification are listed below: (1) biochar is produced through pyrolysis by combining metal salt with biomass raw materials; (2) biochar is generated via the pyrolysis conversion of biomass raw materials into biochar and subsequently soaked the biochar in metal salt under specific conditions75. The SSA of biochar is improved through the pre-pyrolysis modification, while the impregnated metal ions, such as iron, nickel, copper and magnesium, are connected to the biochar surface, providing more catalytic active sites for the catalyst76. Huang et al.77 investigated the influence of different metal dopants (i.e., Cu, Fe, Ni and Ru) on the catalytic pyrolysis of LDPE and mixed plastics over biochar-supported catalysts. After the metal modification, biochar pores became more abundant. Acidic sites on the catalyst catalyze a series of reactions, such as dehydrogenation and dehydrocyclization of alkanes and olefins. The active sites and the physicochemical properties of the biochar can be improved by metal impregnation. By simple metal impregnation, Xu et al.78 synthesized several metal-doped mesoporous graphite catalysts (MMGCs) to catalyze fast co-pyrolysis of biomass and plastic waste to fuels. With the doped metal active sites (Zn, Fe, and Ni), the resulting surface acidity of MMGCs promoted the rate of aromatization and dehydrogenation of hydrocarbons (CnHm) for co-generation of H2 and valuable carbons.

Under the classification of non-metallic modified biochar, sulfonated biochar contains strong sulfonic and weak acid groups (e.g., carboxyl and phenolic hydroxyl) on its surface, making it highly efficient in catalyzing acid-driven reactions (hydrolysis, dehydration, esterification, and transesterification reactions). Concentrated sulfuric acid (98%), fuming sulfuric acid, and gaseous SO3 are the typical sulfonation reagents that expand the pore structure of the biochar for a greater SSA that is conducive to enhanced catalytic efficiency. The density of -SO3H group in H2SO4-sulfonated biochar is lower than that in SO3-sulfonated biochar, attributed to the higher activity and selectivity of gas79. Alkane and aromatic hydrocarbons are produced by -SO3H groups, promoting catalytic cracking, hydrogenation, and aromatization reactions. Meanwhile, weak acids are carried as the hydrogen bonding sites in the former, promoting water adsorption. Mateo et al.80 executed the sulfonation of H3PO4-activated corn kernel biochar (from microwave-assisted carbonization) with concentrated sulfuric acid, where the sulfonated biochar significantly improved the bio-oil quality. Further, Mateo et al.81 validated that the sulfonic acid density increased when the sulfonation temperature was lower. Jahnavi et al.82 found that H2SO4-sulfonated eucalyptus seeds outperformed the AC and zeolite in the catalytic pyrolysis of polypropylene. Compared to Zeolite Y (180–190 °C), H2SO4-sulfonated eucalyptus seeds allowed pyrolysis reaction to occur at milder temperatures (120–130 °C). Apart from sulfonation, gas purging with non-inert gas (i.e., CO2, NH3, or their mixtures) are also used as a method to modify the biochar under the pyrolytic atmosphere.

Optimization of operating parameters on catalytic conversion

The primary goal of most research studies is to improve the quality and quantity of the product. To meet the above two objectives, many studies have been conducted in different kinds of processes with different parameters. The results unanimously showed that catalyst-to-feed ratio, reaction temperature, and reaction time are the most critical parameters that affect the yield and properties of final products83,84,85,86.

Catalyst-to-feed ratio

The catalyst-to-feed ratio determines the number of active sites and the degree of contact between reactants and catalysts. By optimizing the catalyst-to-feed ratio, the catalytic effect, product selectivity, and catalyst stability can be improved to ensure an efficient, eco-friendly, and sustainable catalytic conversion process. The selectivity of mono-aromatics is improved by increasing the catalyst ratio and temperature. For example, Lin et al.75 showed that the waxy compounds were converted more efficiently into liquid, gas, or coke with more AC content, due to the increase in active sites (Fig. 2d). Fe-modified AC had improved catalytic activity because its new strong acid sites (Fe3+) allowed the wax to decompose completely at a lower catalyst feed ratio. However, bio-oil underwent undesirable secondary reactions at excess active sites. Therefore, increasing the catalyst-to-feed ratio decreases the bio-oil production but increases gas yield.

Reaction temperature

Reaction temperature significantly affects the extent of plastic conversion into liquid and gaseous products as well as the product yields. The kinetic energy obtained is affected by the temperature applied by free radicals attacking bonds in long-chain polymers. At high temperatures, the higher kinetic energy of the polymer chain hastens the breakdown of plastics into smaller hydrocarbons, thus increasing the product yield. Besides, energy is not provided well to break polymer bonds at low temperatures, resulting in zero or low overall conversion rates. The minimum temperature for the liquefaction of plastics is 162 °C, while the recorded maximum temperature is 550 °C87. Different plastics require varying temperatures for liquefaction due to their distinct chemical structures and molecular chains, specifically depending on the type of plastic, additives, and liquefaction conditions. For instance, polypropylene typically liquefies within a relatively precise range of 164 °C to 170 °C, applicable to various polypropylene materials. The optimal processing temperature depends largely on the type of plastic polymer and additives (solvents and catalysts). The processing temperature range for each type of plastic is typically determined by observing degradation trends using thermogravimetric analysis. However, it is worth highlighting that the range of degradation temperatures during thermogravimetric analysis and supercritical fluid handling is different with distinct reaction environments88.

Ismail and Dincer89 illustrated the relationship between syngas composition and temperature in the PE waste pyrolysis process. When the pyrolysis temperature rises, the production of methane and hydrogen is increased, while the production of liquid decreases. For rapid pyrolysis of waste polyethylene, Kannan et al.81 unveiled that the total peak intensity of volatiles and the gas yield (almost tripled) increases with the rising temperature, especially from 700–800 °C. Among myriad products, temperature variation has the most profound effect on ethylene but trivial effects on bulky hydrocarbons (more than four carbon atoms), especially above 800 °C (Fig. 2e).

The product distributions of bio-oils is also greatly affected by pyrolysis temperature. As C-C bond cleavage favors high temperatures, higher reaction temperature promotes alkane aromatization, ultimately raising the content of aromatic and hydrogen molecules. At higher temperatures, waxy compounds are preferably cracked into low-molecule-weight compounds, which easily diffuse into the catalyst pore before being converted to the jet fuel range hydrocarbons90. Since gas is easily formed at higher temperatures than bio-oil, the maximum bio-oil yield was more likely to be obtained at a moderate temperature. Rapid pyrolysis reaction produces high yields of bio-oil at high heating rates and low volatilization residence times83, so the pyrolysis reactor should be configured for a high heating rate if the oil production is interested.

For slow pyrolysis with a low heating rate, a uniform temperature for the entire solid mass can be achieved due to sufficient heating time; howbeit, the secondary reactions namely condensation and repolymerization will prompt the formation of coke (char) whereas thermal cracking of volatiles will generate non-condensable gases.

Kanduri and Seethamraju91 showed that compared to the in-situ configuration, the bio-oil quality and the gas production were improved, while char yield was decreased through the ex situ configuration. The study also illustrates that the ex-situ mode has certain advantages over the in situ process, as the temperature of the catalytic stage can be varied according to the desired product yield, thus modulating the course of the reaction and the reaction product fractions.

Reaction time

The contact time between the reactant and the catalyst is determined by the residence time. A long enough residence time allows the reactants to fully diffuse to the active site of the catalyst and interact with it, thereby improving the catalytic conversion efficiency. In addition, the length of residence time directly affects the production and transformation of products. Short residence time may result in insufficient conversion of the reactants, reducing the yield and selectivity of the products. Long residence time may lead to over-conversion of products or production of by-products, which also affects the catalytic effect. Proper residence time can ensure the full utilization of the catalyst’s active sites and the avoidance of wasting catalysts. The kinetic model and reaction mechanism can be developed from the change of reaction rate in response to different residence times. The establishment and analysis of catalytic reaction kinetic models and mechanisms are crucial steps in studying catalytic reaction processes. As one of the key factors affecting reaction rate and product distribution, residence time plays a significant role in the investigation of kinetic models and mechanisms. By varying the residence time and observing changes in reaction rate and product distribution, it is possible to infer the adsorption, and desorption of reactants on the catalyst surface, as well as the key steps and limiting factors in the reaction process.

Controlling reaction time is a crucial strategy in catalytic reaction processes, as it directly affects reaction rate, product selectivity, and catalyst life. To achieve optimal reaction outcomes, various specific measures can be implemented to control reaction time. Firstly, by precisely controlling the feed pump and incorporating automated control systems, the feed rate can be flexibly adjusted, thereby controlling the residence time of reactants in the reactor. Secondly, modifying reactor design is also an effective strategy, including increasing reactor volume, optimizing internal structure, and selecting different types of reactors, to prolong or shorten the residence time of reactants. Additionally, optimizing operating conditions is another important means of controlling reaction time, such as adjusting reaction temperature, controlling reaction pressure, and regulating reactant concentration, all of which can influence the progress of the reaction and the length of residence time. Lastly, adopting advanced monitoring and control technologies is key to achieving precise control over reaction time. Through online monitoring technologies and automated control systems, key parameters during the reaction process can be monitored in real time, and adjustments can be made automatically based on the data to maintain optimal residence time and reaction outcomes. In summary, by comprehensively applying these strategies and specific measures, reaction time in catalytic reactions can be effectively controlled, resulting in a more efficient and stable catalytic process.

Machine learning-guided optimization

As a typical data-driven approach, machine learning (ML) is widely used for innovating advanced carbon materials, such as high-performance biochar and biochar-based catalyst materials92,93,94 and also is successfully employed to predict plastic waste generation, identify plastic waste for classification, and model analysis and optimization in the catalytic process95. ML analyzes the effects of operating parameters such as reaction temperature, pressure, time, and concentration on the catalytic performance of biochar, and establishes the mapping relationship between reaction conditions and catalytic performance. By optimizing these parameters, the catalytic efficiency and selectivity of biochar are improved, and an efficient and green catalytic conversion process could be achieved. ML also reveals the reaction mechanism of biochar catalysis through deep mining and analysis of experimental data. This will help understand further the catalytic process and provide guidance for further catalyst design and reaction optimization.

As displayed in Fig. 3a, b, Zhang et al.96 reviewed on ML-assisted prediction of biochar and its application in anaerobic digestion (AD), verifying ML as one effective approach in addressing biochar-enhanced AD for bioenergy recovery. As a typical case study shown in Fig. 3c–f, Yuan et al. firstly applied ML to predict the application performance of biochar samples92,93, and then further trained the ML models for effectively providing detailed synthesis paraments of biochar samples with high-performance applications, presenting certain closed-loop and promising guidelines (Fig. 3c) for enabling AI-related technologies to foster the accelerated screening, design, and synthesis of BBCs. Especially, after three iterations (Fig. 3d), the biochar samples guided by ML algorithms display enhanced performances and also highly consistent results between experimental and predicted aspects (Fig. 3e, f). Alabdrabalnabi et al.97 conducted ML models to predict the yielding of biochar and bio-oil from co-pyrolysis of biomass and plastics, taking into the characteristics of feedstock, reaction conditions and the amount of plastic in feed (Fig. 2f). Lu et al.98 designed a PET hydrolase enzyme with robustness and activity using an ML algorithm based on structure, and improved enzyme performance on the PETase scaffold through machine-learn-guided predictions. The experimental results showed that recycling enzymatic plastics on an industrial scale is feasible.

a Machine learning (ML)-assisted biochar for enhancing anaerobic digestion (AD) in bioenergy recovery, b schematic diagram of predicting biochar application in AD, c machine learning-based guided synthesis of high-performance biochar samples for CO2 capture, d evolution of biochar textural property in the form of histogram over the ML cycle, e summary of various experimental data guided by ML, and f detailed comparisons between experimental and predicted results96.

Compared to traditional trial-and-error approaches, ML has several main advantages of intuitiveness, high computational prowess, and wide acceptance and application across scientific disciplines99. Most importantly, the limitations and/or challenges of applying ML to develop desired BBCs for high-performance plastic valorization are addressed as follows: (1) the current datasets reported in previous studies are quite small, suggesting that the developed ML models have weak or limited generalization ability to predict their performances of biochar-based catalytic transformations, (2) the data used for training ML models is manually collected, implying that the collected dataset is prone to manipulation with high probability, (3) at current stage, most of investigations only applied ML algorithms for performance predication, however, more important things need to be focused on investigations of feature importance and correlations of process paraments with biochar-based catalytic performance, and (4) the developed predictive ML models for biochar-based catalytic transformation is a first and plain step, it is worth noting that applying ML algorithms to design specific BBCs for sustainable plastic management is more important and interesting. Therefore, to accelerate ML approaches for synthesizing BBCs, both centralized and decentralized data-sharing networks need to be proposed, that ML approaches are highly data-driven; moreover, the strengths of both data-driven and knowledge-based approaches need to be leveraged, which are beneficial to improving the accuracy and interpretability of developed ML models.

Biochar-based catalysts for advanced oxidation processes

As high thermal energy input is unavoidable in thermochemical processes, exploring more efficient processes that can be performed under mild reaction conditions is necessary. In relation to conventional methods, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) were evidenced to be more effective in degrading plastic waste, such as catalytic plastic conversion that is assisted by light, Fenton reagent, or electricity100.

Biochar-based catalysts in photocatalytic systems

Photocatalytic technology is a promising application in environmental remediation and energy conversion, and its end application encompasses organic pollutants degradation, air purification, water splitting, organic synthesis, CO2 reduction, etc.101. Photocatalysis is an attractive and effective strategy for reducing plastic waste because it uses a semiconductor photocatalyst to convert photon energy into chemical energy, preferably at room temperature and atmospheric pressure101. Generally, photodegradation and photosynthesis are the two common photocatalytic plastic conversion systems (Fig. 4a). Photodegradation degrades and mineralizes the plastic into CO2, while photosynthesis uses the plastic as a hydrocarbon resource to produce value-added products. The key criterion that distinguishes photosynthesis and photodegradation is the selectivity of cleaning target products. During photodegradation, highly oxidizing radicals (i.e., -OH) due to mono-linear oxygen are generated under aerobic conditions, leading to non-selective oxidation reactions. The complex fragments and mixtures (i.e., microplastics, nano-plastics, organic compounds, and CO2) are generated by the breakdown of plastic substrates102.

a Two types of photocatalytic plastics conversion systems104, b a photocatalyst panel -CNx/Ni2P without noble metal for the preparation of hydrogen from various plastic wastes, c electronic structure modification strategies in photoelectrocatalytic transformation of plastic wastes, and d regulation of biochar catalyst morphology. (Reprinted with permission from refs. 126,127).

In photosynthesis, plastic is converted into valuable products by photoholes irradiated by semiconductors under hypoxic conditions, while the protons are reduced by the remaining photoelectrons to high-purity H2 (similar mechanisms to CO2 reduction and N2 fixation)103. For H2 production from various plastic wastes, Uekert et al.104 managed to develop a photocatalyst panel -CNx/Ni2P without noble metal, where the panel exhibited a comparable H2 production rate to the corresponding photocatalyst pulp. Scalability was further evidenced by incorporating 25 cm2 panels on the designed flow reactor to produce up to 21 μmol H2 m−2 h−1 under “real world” (seawater, low light) conditions (Fig. 4b).

Compared to the fewer benefits of photodegradation, photosynthesis has intrinsic value in the formation of carbon, H2, energy, or plastic macromolecular structures (precursor of value-added fuels, chemicals, and materials). Green H2 from renewable sources has been regarded as a promising clean fuel in the future, in line with the concept of sustainable development. H2 production via plastic photosynthesis (photo-reforming) expends a lower energy than water splitting as plastics are easier oxidize than water. Although photo-reforming of plastics is feasible, the photocatalytic efficiency is severely limited by the high recombination probability of photoexcited electrons and holes.

Native biochar-based catalysts

Biochar is often used as the basis for the development of various functionalized BC composites due to its large number of surface active groups (C=O, -COOH, -OH, -NH etc.) and easy modification67. Besides, biochar-based photocatalysts have shown their potential applications in plastic waste degradation and conversion. Because of its special structure and chemical properties105, biochar improves the efficiency, optical performance, and stability of photocatalysts in plastic waste degradation. During photocatalysis, the charge separation of the e−/h+ pair after photoactivation is crucial since the photogenerated species are the driving forces of photocatalytic reactions. However, the photogenerated species intrinsically tend to undergo charge recombination. The rapid recombination of the e−/h+ pair can be prevented by introducing biochar into the catalyst formulation. Considering biochar’s larger surface area, the nanoparticles can be distributed more evenly on the biochar surface. Following a good dispersion of surface nanoparticles, the increase in the number of active sites enhanced light scattering, thus improving the photodegradation of adsorbed contaminants. Besides, abundant surface functional groups of biochar enhance the adsorption capacity of photocatalysts for various pollutants, which are beneficial for photocatalysis106.

The photocatalyst with a porous nanostructure has the following four advantages: (1) the improvement of the light absorption capacity due to the multiple scattering of incident light by the pore structure; (2) the nanoscale particle size and pore wall thickness shorten the charge transfer distance, as well as promoting the separation and migration of photogenerated charge carriers; (3) the additional built-in electric fields are induced in the radial direction of the pore structure by the co-catalysts loaded on the inner and outer surfaces of the pores, respectively, which are distributed spatially and further accelerate the dynamics of directional charge transfer; and (4) the density of active center and the mass transfer efficiency of the reactive substrate increase due to the high specific surface area107,108.

Semiconductor-doped biochar-based catalysts

The low photocatalytic activity of raw biochar, which requires high-energy proton excitation, is a known disadvantage of carbon-based semiconductors. Thus, doping semiconductors onto biochar to enhance the photocatalytic performance becomes appealing. Apart from the high stability and electrical conductivity, biochar has plenty of surface functional groups that assist in the adsorption of organics, making biochar a good support for TiO2109. After doping TiO2 onto biochar, the biochar not only serves as the dispersant of TiO2 but also greatly improves the separation efficiency of carriers and broadens the visible light response of photocatalysts. Notwithstanding these improvements, TiO2 powder tends to agglomerate inside the polymer and only favors ultraviolet light absorption, TiO2 alone may not the best photocatalyst dopant. Nguyen et al.110 confirmed the high photocatalytic activity of iron-containing biochar (mainly α-Fe2O3) derived from the iron-contaminated Acrostichum aureum Linn plant. Amir et al.111 overcame the inherent problems (i.e., charge recombination, wide band gap, and poor visible light absorption) of ZnO by synthesizing ZnO/gigantea leave-derived biochar.

The aforementioned studies have confirmed the feasibility of adopting doping strategies for photocatalytic conversion of plastic waste. Besides, the content of the dopant is also closely related to the catalytic activity. Excessive semiconductor dopants may cause undesirable side reactions, such as the possibility of forming recombination sites in the photocatalyst. Hence, the type and concentration of dopants are two important factors for the future development of photocatalysts specifically tailored for plastic waste conversion. He et al.112 demonstrated that ZnO/biochar catalyst had enhanced photocatalytic activity because of its higher specific surface area, greater number of active sites, and stronger electron transfer processes between the interfaces of biochar and ZnO nanoparticles.

In addition, different ratios of semiconductor and biochar have remarkable effects on their structures and compositions, and thus on the catalytic performance. He et al.112 tuned the molar ratio of ZnO and biochar in the synthesis of ZnO/biochar. When the molar ratio of ZnO/biochar was 0.5:1, the resulting biochar-supported ZnO composite exhibited 3D flower-shaped ZnO nanoparticles with an optimal crystalline surface (002), which is responsible for its excellent photodegradation efficiency.

Heteroatom-doped biochar-based catalysts

A crystal defect is an imperfect arrangement of atoms in crystal materials, wherein the missing or irregularly arranged atoms, screw or edge dislocations, grain or twin boundaries, and voids or lattice disorder separately determine the point, line, planar, and volume defects. In photocatalytic technology, the photophysical properties of semiconductor materials can be improved by spontaneous formation or intentional introduction. The presence of surface defects within the semiconductor energy bands induces the formation of additional electronic states, which considerably narrows the bandgap of UV-active semiconductors for better visible light absorption. Further, due to the accompanying thermodynamically unstable coordination of unsaturated atoms and surface-suspended bonds, the local charge gradually accumulates and precisely modulates the local electronegativity and coordination environment around the active site, thus altering the adsorption and activation behavior of the active substrate on the catalyst surface. Defect engineering strategies could effectively achieve an efficient photocatalytic plastic conversion process by adjusting the electronic structure of photocatalysts.

The use of carbonaceous materials as carriers for semiconductor materials to rapidly trap electrons and retard the recombination of electron-hole species is an excellent strategy to further enhance photocatalytic activity by doping with electron-deficient heteroatoms, which facilitates ultrafast electron transfer processes via interfacial interactions. For instance, Hou et al.’s113 ultrathin nitrogen-doped biochar-modified biospheres showed high photocatalytic activity. A large number of well-contacted interfaces were formed between N-doped hierarchical structure cattail-based carbon (NCC) and BiOI, acting as electron-acceptor bridges during ultrafast electron transfer, thus hindering electron-hole pair recombination. Through first-principles calculations, Cao et al.114 constructed a model catalyst to examine the electric and structural properties of BiOCl/biochar before and after Co(II) doping. The Co dopant enhances the photocatalytic effect of Co-BiOCl/biochar by narrowing the band gap. Meanwhile, the doping of nonmetallic elements like iodine (I) into biochar could reduce the band gap, broaden visible light absorption, promote photogeneration of charge carriers, inhibit charge complexation, reduce photo corrosion, and raise conductivity.

The electronic structure of the photocatalyst can be fine-tuned by introducing external impurities as dopants into the semiconductor to (1) generate electronic states, including donor levels above the valence band (VB) and/or acceptor levels below the conduction band (CB); (2) adjust the band structure, especially the position of minimum CB and maximum VB; (3) improve the absorption and utilization efficiency of the visible light region; (4) accelerate the transfer kinetics of photoelectrons and holes; and (5) control the exposed crystal face and crystal phase. Based on the aforementioned merits, defect engineering could be an efficient method to convert plastic waste through a photocatalytic process. The adsorption and activation behavior of reactive substrates on the photocatalyst surface can be regulated by abundant coordination of unsaturated atoms and surface-suspended bonds. However, the electron transfer efficiency can be reduced by defects that act as charge traps. In the future development of photocatalytic conversion of plastic waste, more attention should be paid to the density, location, relative concentration ratio and defect stability of accumulation and surface defects.

Biochar-based catalysts in Fenton-like systems

Fenton oxidation is an attractive AOP because of its high cost-benefit ratio. Fenton’s reagent has been broadly used to treat various pollutants because it can produce many active hydroxyl radicals responsible for the decomposition and/or mineralization of organic substances. Fenton reaction involves free radical-induced bond cleavage, so the degradation of Fenton’s reagents is usually uncontrollable. There is an urgent need for a new approach that makes the reaction more controllable and has better selectivity to obtain the desired valuable product. In Fenton oxidation, plastic waste is broken down into specific small molecules by Fenton reagent. In addition, there is a pressing demand for sustainable and environmentally friendly catalysts. Using a biochar catalyst could curtail the number of toxic contaminants or negate their effects, turning them into by-products or intermediates with milder toxicity and better degradability. Extensive research is being conducted to explore the catalytic properties of biochar.

Native biochar-based catalysts

In many studies, functionalized or engineered biochar has been used as a catalyst when the Fenton process was employed to degrade refractory organic pollutants. High-efficiency oxidation is promoted by adding a biochar catalyst to the Fenton reaction. During this process, Fe(III) was reduced to Fe(II) with biochar acting as an electron donor and electron shuttle. Then, a series of free radicals were produced through the reaction with Fe(II) and O2 dissolved in water, accelerating the Fenton reaction115.

Transition metal-doped biochar catalysts

In the process of magnetic biochar synthesis, transition metals (Fe, Co, Ni, etc.) and their oxides are often added to the biochar matrix. Materials doped into the biochar matrix can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) by activating hydrogen peroxide, persulfate, and other substances, contributing to the effective degradation of organic pollutants116,117. The presence of transition metals in magnetic biochar is critical for the activation of hydrogen peroxide118. The addition of biochar to Fe3S4 can enhance the activity of H2O2 to generate hydroxyl free radicals, thus promoting the degradation of pollutants. The electrons produced by biochar and the particles generated on the surface of Fe3S4 promote the redox cycle of surface iron through the regeneration of Fe2+119. Wang et al.120 synthesized a highly dispersed iron-doped graphite biochar catalyst, which is highly stable and has a wide pH range for efficient generation of hydroxyl radicals through direct single electron transfer to activate H2O2. Hence, doping highly dispersed iron on biochar can considerably improve the catalytic activity of biochar. Due to various synergies, the composite metal oxides show high catalytic activity, but the high solubility of metal ions leads to catalyst instability and low reusability. By ultrasonic impregnation, Zhang et al.121 generated a biochar-supported Fe-Ce catalyst, and the biochar improved the stability by lowering the metal dissolution rate while the composite metals effectively increased catalyst activity. The main limitation in the application of Fenton technology is H2O2, which is costly to transport, store and produce. Hence, it is important to introduce photocatalysts as heterogeneous Fenton reagents to generate H2O2 in situ. Peng et al.122 innovatively used iron plaque as the raw material to prepare CdSe cluster-modified biogenic α-FeOOH on macroporous biochar-based catalysts. Furthermore, they constructed a photocatalysis-self-Fenton system for in-situ H2O2 production. Under visible light irradiation, the photocatalyst activates the molecular O2 to form H2O2 via photocatalysis, and then Fe2+ decomposes the produced H2O2 into •OH efficiently.

Biochar-based catalysts in photo/electrocatalytic systems

In recent years, several literature sources on electrocatalytic conversion of plastic waste have been reported, indicating that plastic waste recycling has great potential123,124. Compared with other technologies, electrocatalytic technology can convert plastic waste into high-value-added chemicals. First, electrocatalysis enables the efficient and selective upgrading of plastic waste into value-added chemicals (such as ethylene, propylene, styrene,) and industrial precursors under mild conditions. Second, in the electrocatalytic reforming process of plastic waste, the cathode enriches the electrons and protons that are released from the anode to produce H2 or liquid fuel, showing great potential for sustainable development. Third, electrocatalysis could realize the conversion of discontinuous and variable electrical energy into chemical energy that is easier to store and transport. Fourth, selective catalytic conversion can be achieved by reactor configuration or rational electrocatalyst design125. Therefore, the electrocatalytic reaction can alleviate the pollution problem, achieve the improvement of waste value, and provide an effective way for the conversion of plastics.

Porous materials with abundant hole channels and voids are useful for electrocatalytic upcycling of plastic. The accessibility of active sites could be enhanced by constructing porous nanostructures within the electrocatalyst, thereby ensuring an effective surface behavior and mass transfer of the reactants. High porosity is the key to enabling some specific photoelectric and electronic functions in photoelectrocatalysts. For porous nanostructures, different levels of porosity, sc. microporous (<2 nm), mesoporous (2–50 nm), and macroporous (>50 nm) can permeate the inner and outer spaces of pores and channels. The porous structures can provide a wealth of active sites for mobile guest species in various applications, such as adsorption, separation, storage, energy conversion, and catalysis. For photocatalysis and electrocatalysis, nanoporous catalysts typically possess high specific surface area, tunable pore size and wall thickness, as well as interconnected porous networks. These beneficial features can promote the mass transfer of the reaction matrix to the active site in the channel as well as facilitate the adsorption or desorption of the reaction substrate at the active site. For electrocatalysis, the design of the anode is crucial to guarantee good performance of fuel cells or electrolyzers. Carbon-based anodes should have sufficiently large structures with high surface area so that plastic oxidation can manifest. Hori et al.126 improved the performance of electrocatalytic hydrogen production from plastic waste using carbon anode materials with different pore structures and designing a flow injection system.

Indeed, the development of porous nanostructures is a promising approach to promote surface-led heterogeneous photoelectrocatalytic conversion of plastic waste. However, there are still some technical challenges in this field. During multiple cycles of catalytic processes, porous structures are prone to collapse, resulting in a low recycling utilization rate. Although thickening the pores can avert structural collapse, it will increase the charge transfer distance and reduce the conversion efficiency. More sophisticated designs of porous nanostructures are needed to overcome these challenges127.

In photoelectrocatalysis, the electronic structure of photocatalysts and electrocatalysts plays a critical role in their catalytic activities. The intensity of light absorption (especially visible light), the concentration and mobility of photogenerated carriers, as well as the redox of photocatalysts, are easily affected by their electron band structure. Similarly, the electronic structure of electrocatalysts affects their thermal/electrical conductivity, the adsorption/desorption behavior of important intermediates, and the reaction energy barrier of the rate-limiting step. Nowadays, the modification of electronic structure is widely used in the catalytic transformation of plastic waste. These strategies include the doping strategy to introduce external impurities, the alloying strategy to fabricate multi-component solid solutions, and the defect engineering strategy to introduce structural defects (Fig. 4c, d).

Catalyst induced into foreign atoms has the advantages of regulating the distribution of local charges, enhancing the conductivity and electron density, serving as the active site of the reaction substrate, and reducing the reaction energy barrier by controlling the adsorption and activation behavior of important intermediates. Thus, doping strategies have been widely used in the electrocatalytic conversion of plastic waste into H2 fuel and valuable chemicals.

Properties, upgrading, and applications of catalytic conversion products

From Section “Biochar-based catalysts for advanced oxidation processes”, it is understood that advanced oxidation processes of plastic waste can produce valuable chemicals and fuels under relatively mild conditions, but there are some limitations to these emerging technologies, viz. high design cost and difficulty in scaling up. Compared to advanced oxidation processes, thermal catalytic conversion is currently the most widely used and easiest to realize on a large processing scale.

Properties of catalytic conversion products

Catalytic conversion products comprised the solid, liquid, and gaseous fuels (Fig. 5a). The product distribution of catalytic plastic pyrolysis is influenced by the reaction conditions (i.e., temperature, time, and feedstock) and catalyst properties (i.e., type, pore structure, and acid content of catalyst). Frequently, catalytic plastic pyrolysis aims to convert plastic waste into liquid fuels, with gaseous and solid fuels as concomitant products. Fuel products based on plastic waste can also be effectively replaced by traditional fossil fuels.

a Products from catalytic plastic waste pyrolysis131, b photographic images of waste cooking oil biodiesel production and glycerol separation137, c typical layout of the engines tested, and d internal combustion engine of single cylinder, liquid-cooled, naturally aspirated diesel engine with computerized test rig137. (Reprinted with permission from ref. 137).