Abstract

Qarhan Salt Lake, China’s largest brine-type potassium-lithium deposit, holds substantial economic value. However, the timing of lithium-rich brine formation, its origin, and the role of climate in its development remain unclear. This highlights the need for a deeper understanding of salt lake evolution, particularly regarding ore-forming brine composition and the palaeoclimate. Therefore, we conducted 230Th dating on halite deposits from borehole ZK6-7 (7.5–46.7 metres) in the northern Bieletan, revealing halite deposition at 237.79–30.29 thousand years before 2000 A.D. The maximum homogenisation temperature of fluid inclusions was 23.9–41.7 °C, indicating frequent palaeobrine temperature fluctuations, corresponding to palaeoclimatic events in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and Qaidam Basin. Lithium, potassium, magnesium, boron, and bromine concentrations were inversely correlated with the maximum homogenisation temperature. Lithium-rich brine formation in the Bieletan was a long-term process driven by interglacial-glacial cycles, where warm periods increased river flow and material supply, while dry-cold periods intensified evaporation, promoting mineral enrichment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Qarhan Salt Lake (QSL), situated in the eastern Qaidam Basin (QB), is China’s largest industrial source of potassium and lithium. Despite its significance, the metallogenic mechanisms and salt-forming periods, especially in the lithium-rich Bieletan (BLT) section, remain controversial topics1,2,3,4,5. The BLT brine holds ~12 Mt of LiCl reserves, with solid and liquid potassium reserves comprising >60% of the total in QSL6. Previous studies have correlated metallogenic processes with global palaeoclimatic events by comparing isolated age data. However, this approach may overlook regional variations in recharge sources and topographic structures. The lack of palaeotemperature data and detailed analyses of palaeobrine composition has restricted our understanding of salt lake evolution and resource formation, limiting studies on critical deposition periods and sedimentary events.

The formation and evolution of lithium-rich salt lakes are influenced by climate change, material sources, and structural coupling7,8. Salt lake sediments record periodic shifts between freshwater and saline conditions, capturing unique salinity and climatic fluctuations which are rarely preserved in typical lacustrine deposits9,10,11. Investigating these environmental changes is crucial for reconstructing salt lake history and unravelling the mechanisms behind resource enrichment, offering valuable insights into ore deposit development12,13,14.

Primary fluid inclusions in halite crystals preserve direct records of brine composition and the physical and chemical conditions during crystal formation, making them invaluable for studying evaporative environments15,16,17. Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) has emerged as a powerful tool for fluid inclusion analysis due to its high sensitivity and broad dynamic range18,19,20,21. Halite, commonly formed in epigenetic environments, often traps primary fluid inclusions at low pressures, allowing direct palaeotemperature measurements. The maximum homogenisation temperature (Th, max) of these inclusions, determined through freezing homogenisation, generally correlates with local air temperatures22,23, providing critical data for palaeoenvironmental and palaeoclimatic reconstructions24,25,26,27.

The uranium-series disequilibrium method (230Th) exploits the disequilibrium between the radionuclide 238U and its decay progenies 234U and 230Th to date evaporite deposits using multicollector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (MC-ICP-MS)28. Extensive 230Th dating studies of rock salt deposits in the arid regions of western China have established a reliable stratigraphic chronology, forming a crucial foundation for investigating climatic and environmental changes, tectonic movements, basin evolution, and the processes of salt formation and mineralisation21,29.

This study combined 230Th dating, primary fluid inclusion composition analysis, and palaeotemperature reconstruction to elucidate the relationships between the formation period, material sources, and climatic conditions of potassium- and lithium-rich brines in the QSL.

Geological setting

The QB, the largest plateau basin on the northern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (QTP), is characterised by a complex geological evolution, rich resources, and sensitivity to global climate change30,31,32. Bordered by the Altun, Qilian, and Kunlun Mountains, it is a rhomboidal inland basin covering ~120,000 sq. km23,33. Continuous lacustrine strata have been deposited since the Oligocene, recording essential data on the uplift and environmental changes in the QTP. The surrounding mountains create rain shadows, making the QB one of the driest regions in Central Asia, with an average annual precipitation of 55 mm and evaporation >3000 mm annually9. This extreme aridity, coupled with a lack of outflow, has led to the evaporation of lakes, increased salinity, and the formation of extensive dry salt flats and salt lake landforms.

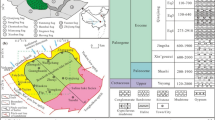

The QSL is divided into two sub-basins by basement structures: the Biele Depression, Bieda Uplift, and Dacha Depression34. The playa is further subdivided into four sections from west to east: the BLT, Dabuxun (DBX), Qarhan, and Huobuxun (Fig. 1). The BLT section, located in the centre of the QB, spans >1500 km2 with salt deposits up to 70 m thick4.

a Location of the Qaidam Basin on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau (from Google Earth). b Schematic geological map of the Qaidam Basin. c Geological map of Qarhan Salt Lake showing the borehole site. Altitude data based on ASTER GDEM 30 m resolution digital elevation data downloaded from (https://www.gscloud.cn/search).

The BLT, along with the West Taijinaier, East Taijinaier, and Yiliping Salt Lakes, is a terminal salt lake fed by the Hongshui (H) and Nalenggele (N) rivers. The Hongshui River, originating from Bukadaban Peak in the Kunlun Mountains, transports high concentrations of potassium, lithium, and boron30. It is the only river that crosses the East Kunlun fault and reach the QB35. Over 50% of the H-N River infiltrates the groundwater at the pre-mountain alluvial fan, re-emerging as spring-fed rivers, including the East Taijinaier and Wutumeiren River20. The lithium-rich Wutumeiren River flows into Senie Lake, where prolonged evaporation increases the average lithium concentration to 0.106 g/L36. The intercrystalline brine of the BLT section is continuously replenished by lithium-rich seepage from Senie Lake, with an average lithium concentration of 0.594 g/L and a maximum of 1.225 g/L37. Potassium is primarily derived from the residual waters of the Nalenggele River, Golmud River, northern fault zone, and the ancient Qaidam Lake. Understanding the distinct sources and processes of lithium and potassium enrichment is crucial for understanding the metallogenic mechanisms of large continental salt lakes.

Results and discussion

Petrological characteristics

The core samples contained numerous micron-sized square primary fluid inclusions that appeared opaque to translucent under a microscope. These inclusions were distributed in alternating bands with clear zones devoid of inclusions, forming chevron growth patterns (Fig. 2a, b) and cumulative crystals (Fig. 2c, d), with chevron crystals dominating. The inclusions ranged in size from 5 × 5 μm to 80 × 80 μm. Most inclusions were single-phase liquids (Fig. 2e), although some were gas–liquid two-phase inclusions (Fig. 2f).

Homogenisation temperature of fluid inclusions

A total of 741 fluid inclusions from 18 samples were analysed to determine the homogenisation temperature. The homogenisation temperatures ranged from a maximum (Th, max) of 41.7 °C to a minimum (Th, min) of 5.9 °C, with average values (Th, avg) between 15.6 °C and 31.2 °C. Most homogenisation temperatures fell within the 14–28 °C range (Supplementary Fig. 1). The detailed temperature data are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Chemical composition of fluid inclusions

The chemical compositions of the fluid inclusions in 18 samples were analysed, with 15 data points per sample, yielding 210 valid data points (Supplementary Table 2 and Fig. 3). The temporal variation in ion signal strength during the analysis revealed two distinct patterns (Fig. 4): (1) an initial sodium ion signal from halite crystal ablation followed by an increase in other ions, indicating inclusions at a distance from the crystal surface (Fig. 4a, b); and (2) a simultaneous increase in all ion signals upon direct ablation of inclusions on the crystal surface, with a subsequent slight decrease in Na signals (Fig. 4c, d).

The chemical composition of the fluid inclusions varied across different test points within the same sample (Fig. 3), and the corresponding mass-spectrum signal intensities are depicted in Fig. 4. These variations primarily arose from the selection of inclusions from distinct halite crystal bands, reflecting efforts to capture a more comprehensive profile of the palaeobrine composition. The presence of extremely high values may have indicated the influence of episodic events such as hydrothermal activity or extreme climatic conditions.

230Th dating results

Supplementary Table 3 summarises the 230Th dating results for the ten halite samples, including U and Th concentrations, U–Th atomic ratios, and both uncorrected and corrected ages. The age of sample H-16 was determined to be 131.14 ± 233.45 thousand years before present (ka BP), where “present” is defined as the year 2000 A.D.; however, the low U content caused a large error, making the results unreliable.

Geological significance of homogenisation temperature data

Hydrothermal activity is a common phenomenon in evaporite basins and may influence the homogenisation temperature of fluid inclusions. Over 90% of temperature difference data (Pdf, 10–15 °C) was 10–15 °C (Supplementary Table 1), revealing that these primary fluid inclusions were not altered by late-stage hydrothermal processes38.

Deformation can cause the homogenisation temperature of fluid inclusions to deviate from the true palaeotemperatures, especially in larger inclusions that are more susceptible to pressure from the overlying strata or hydrothermal activity, leading to increased temperatures39. However, in this study, no clear correlation was observed between the inclusion size and homogenisation temperature (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 4), implying that the samples did not experience late-stage alteration. Thus, the homogenisation temperatures measured in this study likely reflect the palaeobrine conditions at the time of halite deposition.

Halite typically precipitates during summer afternoons, with cumulative crystals forming in the surface brine layers and chevron crystals forming at the bottom of the shallow brine (<50 cm)40,41. The Th, max of the fluid inclusions captures the temperatures of the surface and bottom brine during summer27,42. A close relationship exists between bottom brine temperature and atmospheric temperature. In shallow brine environments, the annual and seasonal average temperatures of the bottom brine closely approximate surface atmospheric temperature25,26,43. For example, in Owens Lake, located in eastern California, USA, the average summer temperature of the bottom brine closely matches the average atmospheric temperature, with a difference of only 1–4 °C in other seasons. The average temperature difference between the bottom brine and atmosphere in a single year was ~1.57 °C44.

Therefore, the Th, max (23.9–41.7 °C) of primary fluid inclusions in the halite from the ZK6-7 core reflects the summer palaeotemperature during halite deposition.

Age analysis of evaporite formation in the BLT section

Using 230Th dating data from nine halite samples, a Bayesian age–depth model for borehole ZK6-7 was constructed using Bacon software (Supplementary Fig. 3), providing age estimates for the remaining samples. Notably, four samples (H-8, K-2, H-14, H-19) exhibited 230Th ages that deviated considerably from the expected stratigraphic sequence and did not increase with depth. To ensure the consistency of the age–depth relationship, the model-simulated ages were used to replace the 230Th ages of these four samples (Supplementary Table 5). These results indicated that halite deposition in borehole ZK6-7 occurred between ~237.79 and 30.29 ka BP. An age–depth framework for borehole ZK6-7 was established according to the stratigraphic sequence (Fig. 5).

However, the timing of salt formation in the QSL remains controversial. Approximately 30 ka BP, neotectonic movements led to the invasion of ancient lakes in the East Kunlun Mountains by the N and G Ancient Rivers, causing brackish water to flow into the Qarhan Ancient Lake45. Optically stimulated luminescence dating of quartz from the Nalenggele River terraces indicated that the formation of the terminal salt lake and lithium enrichment occurred ~15 ka BP46. Additionally, 230Th tests of the borehole core in the eastern BLT and eastern DBX sections suggest a salting period of ~50 ka BP29,47. Lai et al. used optically stimulated luminescence to date the shell bar to 113–99 ka BP, which is earlier than the previous 14C ages of 40–30 ka BP1,2,3.

The evolution of salt lakes and evaporite deposition is closely tied related the migration of the depositional centre in the QB and tectonic activity in the northeastern QTP48. The bedrock erosion in the Kunlun–Golmud River Valley indicates that the river system incised to its present valley floor before the middle to late Early Pleistocene, and the Golmud River system attained its current form by that time49. The fluvial patterns and longitudinal profiles of the N and Golmud Rivers were modified by the left-lateral strike-slip of the East Kunlun Fault, suggesting that these rivers were established ~15 Ma before the occurrence of the East Kunlun fault39. Thus, whether the Nalenggele River terraces and shell bar represent the salting period of the QSL or the lithium deposition age in the BLT section requires further investigation.

Before halite deposition, the BLT section was a deep, isolated sub-basin50. The Bieda Uplift between the BLT and DBX prevented the Wutumeiren River from supplying high-lithium water to DBX. The DBX and Qarhan sections were still in the pre-playa stage, and the BLT playa was deposited at the 60 m contour. As the BLT playa thickened to ~15 m, it connected with the DBX, forming a unified QSL36. This explains why the halite depositional age in the BLT was markedly older than that of DBX.

Monitoring data from the BLT section indicated that the brine mainly migrated northward, where the lithium concentration is the highest6. A 3D model of the BLT section reveals that lithium-rich brines are primarily distributed in the north-central region51. The depositional centre of the BLT section was likely located in its northern area. Therefore, the salting age of eastern borehole ISL1A, at 50.7 ka BP29, was much lower than that of western borehole ZK6-7.

Furthermore, investigations of alluvial fans deposited by the H-N River at the northern foot of the Kunlun Mountains suggested that before halite deposition, the elevations of the East Taijinaier and Yiliping Salt Lakes were ~20–40 m higher than those of the BLT section6. Consequently, most of the streams flowed into Senie Lake and BLT. Following the prolonged expansion of alluvial fans, the East Taijinaier River formed, discharging runoff from the H-N River into the East Taijinaier, West Taijinaier, and Yiliping Salt Lakes, where lithium deposition began. Recent geochronological and LA-ICP-MS studies confirmed lithium enrichment in the 120–100 ka BP halite layer of the Yiliping Salt Lake, with the lithium content in fluid inclusions ranging from 135.49 to 248.09 mg/L21,52. Optically stimulated luminescence and AMS14C measurements of West Taijinaier Salt Lake sediments indicate that they formed at least 70 ka BP10,53. Data from this study revealed that the BLT section began receiving lithium-rich water from the H-N River ~240 ka BP. The lithium content in fluid inclusions from this period, ranging from 0.17 to 4.15 g/L, was considerably higher than that of the Yiliping Salt Lake at 120 ka BP.

Palaeoclimate reconstruction during the formation of lithium-rich palaeobrine in the BLT section

The H-N River transported substantial amounts of soluble elements (lithium, boron, etc.) to terminal salt lakes, which were progressively enriched through evaporation under arid climatic conditions34,54. Once lithium is released from primary minerals, it remains in solution rather than forming crystalline minerals, especially as a lake desiccates55,56. The absence of lithium- and boron-containing minerals in the BLT section sediments57 indicated that lithium and boron were consistently preserved in the palaeobrine during evaporation. The positive correlation between lithium and boron substantiated the experimental data (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The modern H-N River is primarily fed by meltwater from alpine ice and snow, with frequent flooding in July and August and the lowest water levels in March and April6. Flooding temporarily deepened and expanded Senie Lake; however, the dilution effect was brief. In a dry-cold winter climate, reduced recharge of salt lakes and decreased halite solubility trigger substantial halite precipitation36. The relationships between the Th, max of fluid inclusions and the concentrations of lithium, potassium, boron, magnesium, and bromine were inversely correlated (Supplementary Fig. 5), confirming that brine is highly concentrated in dry-cold environments. The geochemical behaviour of calcium differed. Between 24 and 36 °C, no clear relationship was observed between calcium content and Th, max; however, above 40 °C, calcium content increased noticeably. At lower temperatures, as brine evaporated, calcium more likely precipitated as gypsum. In contrast, higher temperatures and recharge conditions increased calcium solubility and enrichment in the brine.

High temperatures generally accelerated the evaporation and concentration of brine, thereby promoting the deposition of salt minerals. However, in the QB and QTP, the salt-forming period of the salt lakes fed with glacial meltwater was controlled by glacial-interglacial cycles. Specifically, salt formation in the QTP aligned with the Quaternary glacial periods9,48. During these glacial periods, dry-cold conditions and cryosphere expansion reduced water inflow into the basin, leading to increased evaporation and higher salinity of the salt lake58,59. However, the climate fluctuated periodically, and precipitation did not necessarily decrease during glacial periods. For example, precipitation during marine isotope stage 16 (MIS 16) was higher than the current levels60. The most recent interglacial (MIS 5) and glacial (MIS 3) periods experienced multiple warm and glacial phases (Fig. 6).

a LR04 δ18O curve61. b Lake transgression phase of Lake Nam Co, Tibetan Plateau62. c Total organic carbon (TOC) curve from Qarhan Salt Lake borehole CH031063. d Log of natural gamma radiation (counts per second) in the Salar de Uyuni drill76. e Wet phase in the Salar de Atacama78. f Maximum homogenisation temperature of fluid inclusions in halite from borehole ZK6-7. g Lithium content in halite fluid inclusions from borehole ZK6-7. The blue areas represent glacial periods. The grey curve represents January insolation at 15°S77. The green curve represents March insolation at 20–30°N80.

The δ18O curve (Fig. 6a)61, the pan-lacustrine stage of Nam Co Lake in the QTP (Fig. 6b)62, and the total organic carbon (TOC) curve from borehole CH0310 in QSL (Fig. 6c)63 closely corresponded with the fluctuations in Th, max of fluid inclusions (Fig. 6f) over tens of thousands of years. The TOC curve, which reflects climate changes not captured by the δ18O curve, exhibited periodic cycles that deviate from the δ18O data. Thus, the climate of QB exhibited both global and regional characteristics.

During the early stage of MIS 7 (247.7–218.1 ka BP), the QB had a semi-arid climate with sparse forest and grassland vegetation. However, a sharp temperature decrease in late MIS 7 (218.1–209.4 ka BP) led to the lowest sedimentary levels in Leng Lake, which were characterised by sparse vegetation and a lack of palynological records64. Correspondingly, Th, max values from borehole ZK6-7 at 237.79, 231.50, and 206.62 ka BP were 28.8 °C, 28.9 °C, and 26.4 °C, respectively. The prolonged semi-arid and dry-cold climate during this period led to extreme enrichment of potassium, lithium, magnesium, and boron in the palaeobrine of the BLT section (Fig. 7).

During the penultimate glacial period (MIS 6), the climate was notably ‘dry and cold’, with temperatures in the eastern QTP 8–12 °C lower than present. Widespread halite deposition in most QB salt lakes occurred, and cold-phase mineral mirabilite deposits were discovered in Yiliping, Chahansilatu, and Dalangtan salt lakes33,65. The temperature increase at the end of MIS 7 increased the water supply, causing a sharp decrease in the concentrations of potassium, lithium, magnesium, and boron in the palaeobrine. As MIS 6 progressed, these ion levels increased again owing to a reduction in water supply.

Palynological studies of borehole I in the DBX section during MIS 5 indicate that 122–110 ka BP was a warm and wet period66. The high lake water levels recorded in Tianshuihai Lake on the QTP occurred between 132 and 112 ka BP67. At 115.9 ka BP, water levels in Nam Co Lake peaked at 139 m above its current level (Fig. 6b). Salt crust ages of 97 ka BP and 136 ka BP in the QSL suggest that the ancient lake was nearly dry and experienced extreme arid conditions during these times68. Th, max values of borehole ZK6-7 at 100.05 ka BP and 115.20 ka BP were 28.5 °C and 41.2 °C, respectively, aligning with the early to middle MIS 5 climate recorded in previous studies. Sedimentary magnetic susceptibility and chromaticity (b*) data from Qarhan Lake indicate an extremely dry-cold period beginning at 86 ka BP and lasting until 57 ka BP69. During the late MIS 5 (87.22–79.52 ka BP), Th, max values ranged from 23.9 to 27.2 °C.

The late MIS 3b and MIS 3a were warm periods, characterised by Th, max values of 33.6–42.65 °C recorded between 42.64 ka BP and 30.29 ka BP, which are consistent with the prevailing climatic conditions of that time. The pan-lake period for the lakes in the western Ngari region of the QTP between 32°N and 34°N was 43–30 ka BP70. The last high lake level in Tianshuihai Lake occurred at 42–35 ka BP67. Sedimentary changes in the QSL and palynological studies of the DBX section (borehole I) suggest that the desalination phase of Qarhan Ancient Lake under high temperature conditions 41.9–30.9 ka BP66.

Analysis of variations in lithium-rich brine deposition

Through a comprehensive analysis of lithology, lithium content in fluid inclusions in halite, and Th, max at various depths of borehole ZK6-7, brine deposition was divided into three stages: upper, middle, and lower. Each stage reflected distinct genesis processes and sedimentary environmental characteristics.

The upper strata (7.5–15.9 m) primarily comprised silty halite and mirabilite/gypsum-containing silty halite. The lithium content in the halite inclusions was relatively high, particularly during MIS 4, when the lithium concentration in the halite layers containing the cold-phase mineral mirabilite was 5.05–5.85 g/L. During this period, the Th, max reached 23.9 °C. Despite the low Th, max across the upper strata, the increased precipitation during the warm and humid conditions of MIS 5c likely temporarily diluted the salt lake water. However, as precipitation decreased towards the end of MIS 5 and evaporation intensified, the salt lake started contracting, which greatly elevated lithium concentrations under the increasingly dry conditions. This climatic shift was further supported by the δ18O record from fine-grained lake carbonates of the QSL29. The relatively low sedimentation rate (0.07–0.23 m/ka, mean 0.15 m/ka) provided a favourable time window for the enrichment of soluble elements, such as lithium.

The middle strata (15.9–40 m) exhibited more complex lithology and a relatively lower degree of lithium enrichment (0.17–1.38 g/L), with an increased sedimentation rate (0.08–0.86 m/ka, mean 0.21 m/ka). During the late MIS 7 (~194 ka BP), increasing temperatures (Th, max 41.3 °C) promoted increased precipitation and glacial meltwater, resulting in the influx of more detrital material and lithium resources. A 2.8-m thick halite-containing silt layer (34.3–37.1 m) was deposited in the early MIS 6. The water supply in the BLT section primarily relied on meltwater from the Kunlun Mountain glacial system, with evidence suggesting that MIS 6 glaciation was more extensive than the Last Glacial Maximum71, and the expansion of the ice sheet was supported by evidence of glacial advance72. The reduced influx of water into the basin led to the concentration of the salt lake water and an increase in salinity73,74, resulting in the deposition of a 7.7-m thick silt-containing halite layer. The prolonged duration of the glacial period inhibited the migration of soluble elements75. During this period, lithium concentrations remained relatively low at 0.17 g/L at 194.84 ka BP, increasing only to 1.38 g/L by 141.34 ka BP. Upon entering MIS 5, frequent climatic fluctuations during interglacial periods, combined with the impact of floods, introduced more detrital material, leading to an increase in the sedimentation rate (0.86 m/ka for the K-2 to B-9 section). However, owing to the alternating deposition of salt minerals and silts, lithium enrichment was somewhat diluted, and lithium content was 0.34–0.48 g/L.

The lower strata (40–47 m) exhibited more complex lithology, with a relatively stable lithium content of 3.92–4.15 g/L. Owing to the greater depth of the lower strata, uranium elements greatly reduced, rendering the 230Th dating ineffective. Consequently, the sedimentation rate was modelled at 0.19 m/ka. Despite the lower Th, max values recorded in the three samples, the sedimentary environment during the MIS 7 period exhibited pronounced climatic fluctuations (Fig. 6a, c). At a depth of 43.7–44.5 m, halite formed microcrystalline structures, and no effective sample was obtained. Based on the lithology of the silt layers between 42 and 43.7 m, this layer likely formed under a warm and humid climate, leading to increased water supply. Subsequently, a temperature decrease facilitated the enrichment of lithium. Overall, lithium enrichment in the lower strata was primarily influenced by climatic fluctuations, particularly during periods of cooling, when intensified water concentration effects created favourable conditions for lithium accumulation.

Comparison of palaeoclimate between the QSL and South American salt lakes

A comparative analysis of palaeoclimate changes between the QSL (ZK6-7) and South American salt lakes offers valuable insights into the driving mechanisms of global climate change on salt lake sedimentation. The natural gamma radiation fluctuations in Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia, were correlated with changes in solar radiation at 15°S (Fig. 6d)76,77. Increased solar radiation enhanced monsoonal circulation, promoting the transport of moisture from the Atlantic, resulting in more precipitation and glacial meltwater. During periods of high solar radiation, this process maintains the lake state of Salar de Uyuni, while during low radiation intervals, the lake transitions into a shallow salt lake or salt sediment area76. Similarly, the wet periods in Salar de Atacama, Chile, correspond to high solar radiation intervals (Fig. 6e)78, further supporting the influence of monsoonal and radiation-driven changes on salt lake hydrology.

In Salar de Pozuelos, Argentina, lithium accumulates under cold and dry climatic conditions through chemical weathering79, a process analogous to the lithium deposition observed in the QSL. The Th, max fluctuations in borehole ZK6-7 exhibited a pattern similar to solar radiation changes between 20°N and 30°N (Fig. 6f)80 and were negatively correlated with the lithium content in halite fluid inclusions (Fig. 6g). The dry and cold climate driven by solar radiation changes played a crucial role in salt lake sedimentation and lithium enrichment in low-latitude regions. This climate not only influenced sedimentary processes in South American salt lakes but also profoundly impacted sedimentation and resource accumulation in salt lakes on the Tibetan Plateau.

This comparative analysis provided a perspective on the mechanisms of salt lake resource formation in low-latitude regions, emphasising the pivotal role of dry, cold climates and solar radiation fluctuations in driving salt lake sedimentation and lithium enrichment.

Methods

Homogenisation temperature determination of primary fluid inclusions in halite

Eighteen halite samples were collected from borehole ZK6-7 in the BLT section of the QSL (Fig. 1). Intact crystals were sectioned along cleavage planes and examined microscopically to identify primary fluid inclusions. To distinguish two-phase (gas–liquid) from single-phase (liquid) inclusions, samples were first cooled to −20 °C to induce bubble formation, then heated at 0.5 °C/min, reducing to 0.1 °C/min near homogenisation. Homogenisation temperatures were measured using a Linkam THMSG600 heating-freezing stage with an accuracy of ±0.1 °C at the Institute of Mineral Resources, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences.

Chemical composition analysis of primary fluid inclusions in halite

Primary fluid inclusions were analysed using LA-ICP-MS at the National Research Center for Geoanalysis, China Geological Survey. Halite samples were ablated with a New Wave UP213 laser and measured on a Finnigan Element 2 ICP-MS, with high-purity helium as the carrier gas. Data processing followed the protocol of Hu et al.21.

230Th dating

230Th dating was performed at the Laboratory of Uranium Series Chronology, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Ten halite samples from the borehole cores were meticulously sectioned to minimise contamination. Analyses were conducted using a Neptune Plus MC-ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled with a CETAC Aridus 1 microsampling system (Teledyne CETAC). Sample preparation followed the protocols outlined by Wang et al.28.

Data availability

All datasets in this study are publicly available. The raw data can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28783730.

References

Chen, K. Z. & Bowler, I. M. Late Pleistocene evolution of salt lakes in the Qaidam Basin, Qinghai province, China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 54, 87–104 (1986).

Zhang, H. C. et al. Chronology of the shell bar section and a discussion on the ages of the Late Pleistocene lacustrine deposits in the paleolake Qarhan, Qaidam basin. Front. Earth Sci. China 2, 225–235 (2008).

Lai, Z. P., Steffen, M. & David, B. M. Paleoenvironmental implications of new OSL dates on the formation of the “Shell Bar” in the Qaidam Basin, northeastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. J. Paleolimnol. 51, 197–210 (2014).

Fan, Q. S. et al. Boron occurrence in halite and boron isotope geochemistry of halite in the Qarhan Salt Lake, western China. Sediment. Geol. 322, 34–42 (2015).

Chang, Q. F. et al. Chronology for terraces of the Nalinggele River in the north Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and implications for salt lake resource formation in the Qaidam Basin. Quat. Int. 430, 12–20 (2017).

Yu, J. Q. et al. Geomorphic, hydroclimatic and hydrothermal controls on the formation of lithium brine deposits in the Qaidam Basin, northern Tibetan Plateau, China. Ore Geol. Rev. 50, 171–183 (2013).

Oviatt, C. G., Madsen, D. B., Miller, D. M., Thompson, R. S. & McGeehin, J. P. Early holocene great Salt Lake. USA Quat. Res. 84, 57–68 (2015).

Liu, C. L. et al. The impact of the linked factors of provenance, tectonics and climate on potash formation: An example from the potash deposits of Lop Nur Depression in Tarim Basin, Xinjiang, Western China. Acta. Geol. Sin. 86, 2030–2047 (2015).

Wang, J. Y., Fang, X. M., Appel, E. & Zhang, W. Magnetostratigraphic and radiometric constraints on salt formation in the Qaidam Basin, NE Tibetan Plateau. Quat. Sci. Rev. 78, 53–64 (2013).

Zeng, F. M. & Xiang, S. Y. Geochronology and mineral composition of the pleistocene sediments in Xitaijinair Salt Lake region, Qaidam Basin: Preliminary results. J. Earth Sci. 28, 622–627 (2017).

Xue, F. et al. Contrasting sources and enrichment mechanisms in lithium-rich salt lakes: a Li-H-O isotopic and geochemical study from northern Tibetan Plateau. Geosci. Front. 15, 101768 (2023).

Wei, H. C. et al. A 94–10 ka pollen record of vegetation change in Qaidam Basin, northeastern Tibetan Plateau. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 431, 43–52 (2015).

Li, Y. L. et al. Origin of lithium-rich salt lakes on the western Kunlun Mountains of the Tibetan Plateau: evidence from hydrogeochemistry and lithium isotopes. Ore. Geol. Rev. 155, 105356 (2023).

Li, Z. Y. et al. Multi-isotopic composition (Li and B isotopes) and hydrochemistry characterization of the Lakko Co Li-Rich Salt Lake in Tibet, China: origin and hydrological processes. J. Hydrol. 630, 130714 (2024).

Lowenstein, T. K. et al. Oscillations in phanerozoic seawater chemistry: evidence from fluid inclusions. Science 29, 1086–1088 (2001).

Kovalevych, V. M., Marshall, T., Peryt, T. M., Petrychenko, O. Y. & Zhukova, S. A. Chemical composition of seawater in Neoproterozoic: results of fluid inclusion study of halite from Salt Range (Pakistan) and Amadeus Basin (Australia). Precambrian. Res. 144, 39–51 (2006).

Guillerm, E., Gardien, V., Ariztegui, D. & Caupin, F. Restoring halite fluid inclusions as an accurate palaeothermometer: Brillouin thermometry versus microthermometry. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 44, 243–264 (2020).

Shepherd, T. J., Naden, J., Chenery, S. R., Milodowski, A. E. & Gillespie, M. R. Chemical analysis of palaeogroundwaters: a new frontier for fluid inclusion research. J. Geochem. Explor. 69, 415–418 (2000).

Sun, X. H. et al. Composition determination of single fluid inclusions in salt minerals by laser ablation ICP-MS. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 41, 235–241 (2013).

Li, J. et al. Halogenases of Qarhan Salt Lake in the Qaidam Basin: evidence from halite fluid inclusions. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 698229 (2021).

Hu, Y. F., Zhao, Y. J., Wang, M. Q. & Jiao, P. C. The variations of brine composition and its significance in the Yiliping area of the Qaidam basin—evidence from fluid inclusions in halite analysed by LA- ICP- MS. Acta Geol. Sin. 95, 2109–2120 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Halite fluid inclusions and the late Aptian sea surface temperatures of the Congo Basin, northern South Atlantic Ocean. Cretac. Res. 71, 85–95 (2017).

Fan, Q. S. et al. Sr isotope and major ion compositional evidence for formation of Qarhan Salt Lake, western China. Chem. Geol. 497, 128–145 (2018).

Meng, F. W. et al. Ediacaran seawater temperature: evidence from inclusions of Sinian halite. Precambrian. Res. 184, 63–69 (2011).

Lowenstein, T. K., Li, J. R. & Brown, C. B. Paleotemperatures from fluid inclusions in halite: method verification and a 100,000 year paleotemperature record, Death Valley, CA. Chem. Geol. 150, 223–245 (1998).

Zambito, J. J. & Benison, K. C. Extremely high temperatures and paleoclimate trends recorded in Permian ephemeral lake halite. Geology 41, 587–590 (2013).

Zhao, Y. J. et al. Late Eocene to early Oligocene quantitative paleotemperature record: evidence from continental halite fluid inclusions. Sci. Rep. 4, 5776 (2014).

Wang, L. S., Ma, Z. B., Cheng, H., Duan, W. H. & Xiao, J. L. Determination of 230Th dating age of uranium-series standard samples by multiple collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J. Chin. Mass. Spectrom. Soc. 37, 262–272 (2016).

Fan, Q. S., Ma, H. Z., Ma, Z. B., Wei, H. C. & Han, F. Q. An assessment and comparison of 230Th and AMS 14C ages for lacustrine sediments from Qarhan Salt Lake area in arid western China. Environ. Earth Sci. 71, 1227–1237 (2014).

Tan, H., Chen, J., Rao, W., Zhang, W. & Zhou, H. Geothermal constraints on enrichment of boron and lithium in salt lakes: an example from a river-salt lake system on the northern slope of the eastern Kunlun Mountains, China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 51, 21–29 (2012).

Fan, Q. S. et al. Late Pleistocene paleoclimatic history documented by an oxygen isotope record from carbonate sediments in Qarhan Salt Lake, NE Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. J. Asian Earth Sci. 85, 202–209 (2014).

Chevalier, M. L. & Replumaz, A. Deciphering old moraine age distributions in SE Tibet showing bimodal climatic signal for glaciations: marine Isotope Stages 2 and 6. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 507, 105–118 (2019).

Zhang, W. L., Appel, E., Fang, X. M., Song, C. H. & Cirpka, O. A. Magnetostratigraphy of deep drilling core SG-1 in the western Qaidam Basin (NE Tibetan Plateau) and its tectonic implications. Quat. Res. 78, 139–148 (2012).

Zhang, X. R. et al. The source, distribution, and sedimentary pattern of K-rich brines in the Qaidam Basin, Western China. Minerals 9, 655 (2019).

Klinger, Y. et al. High-resolution satellite imagery mapping of the surface rupture and slip distribution of the Mw ∼7.8, 14 November 2001 Kokoxili earthquake, Kunlun fault, northern Tibet, China. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 95, 1970–1987 (2005).

Yu, J. Q., Hong, R. C., Gao, C. L., Cheng, A. Y. & Zhang, L. S. Lithium Brine Deposits in Qaidam Basin: constraints on formation processes and distribution pattern. J. Salt Lake Res. 26, 7–14 (2018). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liang, Q. S. & Han, F. Q. Distribution characteristics of Li content in shallow intercrystalline brine from the Bieletan’s Northwestern edge in Qarhan Salt Lake area. J. Salt Lake Res. 22, 1–5 (2014).

Benison, K. C. & Robert, H. G. Permian paleoclimate data from fluid inclusions in halite. Chem. Geol. 154, 113–132 (1999).

Yu, X. J. et al. River system reformed by the Eastern Kunlun Fault: implications from geomorphological features in the Eastern Kunlun Mountains, Northern Tibetan Plateau. Geomorphology 350, 106876 (2020).

Roedder, E. C. The fluids in salt. Am. Mineral. 69, 413–439 (1984).

Roberts, S. M. & Spencer, R. J. Paleotemperatures preserved in fluid inclusions in halite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 3929–3942 (1995).

Zachos, J. C., Pagani, M., Sloan, L. C., Thomas, E. & Billups, K. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science 292, 686–693 (2001).

Zhang, X. Y., Meng, F. W., Li, W. X., Tang, Q. L. & Ni, P. Reconstruction of Late Cretaceous coastal paleotemperature from halite deposits of the Late Cretaceous Nongbok Formation (Khorat Plateau, Laos). Palaeoworld 25, 425–430 (2016).

Zheng, M. P., Zhao, Y. Y. & Liu, J. Y. Quaternary saline lake sedimentation and paleoclimate. Quat. Sci. 4, 297–307 (1998).

Zhu, Y. Z. & Wu, B. H. The formation of the Qarhan Saline Lake as viewed from the neotectonic movement. Acta Geol. Sin. 64, 13–21 (1990).

Du, Y. S. et al. Evaluation of boron isotopes in halite as an indicator of the salinity of Qarhan paleolake water in the eastern Qaidam Basin, western China. Geosci. Front. 10, 253–262 (2019).

Huang, Q. & Han, F. Q. Evolution of Salt Lakes and Palaeoclimate Fluctuation in Qaidam Basin (Science Press, 2007).

Zheng, M. P. et al. Progress and prospects of Salt Lake Research in China. Acta Geol. Sin. 90, 1195–1235 (2016).

Zhao, X. T. et al. Discovery of the early Pleistocene Kunlunhe conglomerate in Golmud of Qinghai Province and its geological significance. J. Geomech. 1, 1–10 (2010).

Yuan, J. Q. et al. The Formation Conditions of the Potash Deposits in Qarhan Saline Lake, Qaidam Basin, China (Geology Press, 1995).

Cui, Z. H. et al. Spatial distribution characteristics of deep brine reservoir in Beletan area, Qaidam Basin. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 42, 723–734 (2023).

Hu, Y. F., Zhao, Y. J., Wang, M. Q. & Jiao, P. C. Ore genesis of the lithium-rich brine deposit from Yiliping Salt Lake, Qaidam Basin under dry-cold climate: evidence from fluid inclusions. Acta Petrol. Sin. 39, 2185–2196 (2023).

Wang, Y. X. et al. Formation and evolution of the Xitaijinair Salt Lake in Qaidam Basin revealed by chronology. Arid Land Geo. 42, 876–884 (2019).

Gao, C. L. et al. The sedimentary evolution of Da Qaidam Salt Lake in Qaidam Basin, northern Tibetan Plateau: implications for hydro-climate change and the formation of pinnoite deposit. Environ. Earth. Sci. 78, 463 (2019).

Zhang, B. et al. Geological characteristics, metallogenic regularity, and research progress of lithium deposits in China. China Geol. 5, 734–767 (2022). 2022.

Stober, I., Zhong, J. & Bucher, K. From freshwater inflows to salt lakes and salt deposits in the Qaidam Basin, W China. Swiss J. Geosci. 116, 1–30 (2023).

Niu, X., Jiao, P. C., Cao, Y. T., Zhao, Y. J. & Liu, B. S. The origin of polyhalite and its indicating significance for the potash formation in the Bieletan area of the Qarhan Salt Lake, Qinghai. Acta Geol. Sin. 89, 2087–2095 (2015).

Herrero, M. J., Escavy, J. I. & Schreiber, B. C. Thenardite after mirabilite deposits as a cool climate indicator in the geological record: lower Miocene of central Spain. Clim. Past. 11, 1–13 (2014).

Tan, M. Q. et al. Rock magnetic record of core SG-3 since 1 Ma in the western Qaidam Basin and its paleoclimate implications for the NE Tibetan Plateau. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 560, 109949 (2020).

Shi, Y. F. Evolution of the cryosphere in the Tibetan Plateau, China, and its relationship with the global change in the Mid Quaternary. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 20, 197–208 (1998).

Lisiecki, L. E. & Raymo, M. E. A Pliocene‐Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records. Paleoceanography 20, 1–17 (2005).

Zhu, D. G. et al. Evolution of an ancient large lake in the southeast of the Northern Tibetan Plateau. Acta Geol. Sin. 78, 982–992 (2004).

Zhang, J. H. Paleoclimate Change in the Middle and late Pleistocene Revealed by the Core CH0310 in the Qiadam Basin. Ph.D. Thesis, Lanzhou University China (2010).

Yuan, Y. The Characteristics of Climate since Late Pleistocenein Lenghu area of Qaidam Basin and its Response to Global Climate Change and Uplift of the Plateau. Ph.D. Thesis, Tsinghua University, China (2015).

Li, M. H. et al. Evaporite minerals and geochemistry of the upper 400 m sediments in a core from the Western Qaidam Basin, Tibet. Quat. Int. 218, 176–189 (2010).

Jiang, D. X. & Yang, H. Q. Palynological evidence for climatic changes in Dabuxun Lake of Qinghai Province during the Past 500,000 Years. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 19, 101–106 (2001).

Li, S. J., Qu, R. K., Zhu, Z. Y. & Li, B. Y. A carbonate content record of late quaternary climate and environment changes from lacustrine core TS95 in Tianshuihai Lake Basin Northwestern Qinghai-Xizang(Tibet) Plateau. J. Lake Sci. 10, 58–65 (1998).

Ding, Z. J. et al. Episodic sediment accumulation linked to global change in the endorheic Qaidam Basin of the Tibetan Plateau revealed by feldspar luminescence dating. Quat. Geochronol. 81, 101522 (2024).

Chen, Z. Y., Chen, K. L. & Luo, Z. X. Climatic change recorded by the chroma of lacustrine sediments from 130 ka B. P. in Qarhan area. J. Salt Lake Res. 19, 1–7 (2001).

Zheng, M. P., Yuan, H. R., Zhao, X. T. & Liu, X. F. The quaternary Pan-lake (Overflow) period and Paleoclimate on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Acta. Geol. Sin. 80, 169–180 (2006). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Li, J. J., Zhou, S. Z. & Pan, B. T. The problems of quaternary glaciation in the eastern part of Qinghai-Xijing Plateau. Quat Sci 3, 193–209 (1991).

Owen, L. A., Robert, F. C., Ma, H. Z. & Barnard, P. L. Late Quaternary landscape evolution in the Kunlun Mountains and Qaidam Basin, Northern Tibet: a framework for examining the links between glaciation, lake level changes and alluvial fan formation. Quat. Int. 154, 73–86 (2006).

Herrero, M. J., Escavy, J. I. & Schreiber, B. C. Thenardite after mirabilite deposits as a cool climate indicator in the geological record: lower Miocene of central Spain. Clim. Past 11, 1–13 (2015).

Chen, A. D. et al. Gypsum 230Th dating of the15YZKO1 drilling core in the Qaidam Basin: salt deposits and their link to Quaternary glaciation and tectonic movement. Acta. Geol. Sin. 38, 494–504 (2017).

Gu, J. N., Chen, A. D., Song, G. & Wang, X. F. Evaporite deposition since marine isotope stage 7 in saline lakes of the western Qaidam Basin, NE Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Quat. Int. 613, 14–23 (2022).

Fritz, S. C. et al. Hydrologic variation during the last 170,000 years in the southern hemisphere tropics of South America. Quat. Res. 61, 95–104 (2004).

Berger, A. Long-term variations of daily insolation and Quaternary climatic changes. J. Atmos. Sci. 35, 2362–2367 (1978).

Bobst, A. L. et al. A 106 ka paleoclimate record from drill core of the Salar de Atacama, northern Chile. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 173, 21–42 (2001).

Meixner, A. et al. Lithium and Sr isotopic composition of salar deposits in the Central Andes across space and time: the Salar de Pozuelos, Argentina. Miner. Depos. 57, 255–278 (2021).

Berger, A. & Loutre, M. F. Insolation values for the climate of the last 10 million years. Quat. Sci. Rev. 10, 297–317 (1991).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC2906502), and the Qinghai Zhonghang Resources Co., Ltd. Commissioned Science and Technology Research Project (zhzyb20210126-01). We also appreciate Qinghai Salt Lake Industry Co., Ltd for providing geological samples. No specific permissions were required for sampling in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Pengyu Long: conceptualisation, data curation, investigation, writing—original draft; Yanjun Zhao: conceptualisation, formal analysis, methodology, investigation, resources, writing—review and editing; Xiaohong Sun: formal analysis; Ik Woo: formal analysis; Jiangmin Du: formal analysis; Yufei Hu: data curation, formal analysis; Wanping Liu: resources, formal analysis; Ju Jiao: formal analysis; Lisheng Wang: data curation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Andong Chen, Chunliang Gao and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Long, P., Zhao, Y., Sun, X. et al. Lithium enrichment in the Qarhan Salt Lake (China) was a long-term process driven by interglacial-glacial cycles. Commun Earth Environ 6, 307 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02297-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02297-y