Abstract

In February 2022, eastern Australia experienced an extreme flood due to a combination of intense rainfall and close to saturation initial soil water conditions. It resulted in record-breaking water levels and flood volumes, leading to Australia’s largest total insurance claim for a single flood event. Here we analyse the physical factors underlying this event and compare them with a large dataset of floods in Australia dating back to 1950. Our findings show that February 2022 had the largest impact on design flood volumes with a 1% annual exceedance probability, which are expected to increase by 16% on average across the affected region. Additionally, this flood prompted major changes in national flood risk management, including upgrades to flood warning networks and a comprehensive review of the flood insurance sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flooding is the most common type of natural hazard around the world, with an estimated 1.65 billion people affected between 2000 and 20191. The modern approach to flood prevention and mitigation relies on physical and statistical models that generate a range of flood scenarios such as the 1% Annual Exceedance Probability flood (AEP). Despite progress in Earth system modelling, including artificial intelligence2, developing and calibrating flood models remains challenging3 because catastrophic floods typically occur a few times only within hydro-climate data records. At the same time, flood models are becoming more complex to account for climate change4 and include a broader range of simulated events, for example, in coastal areas where riverine floods combine with ocean storm surges5. Increasing flood model complexity requires access to more forcing and calibration data, but the number of in-situ hydro-climate observation sites has declined since the beginning of the 2000s6,7. This alarming trend jeopardises the potential for flood modelling to tackle emerging societal issues like rising exposure to flood hazard8,9,10, especially in low- and middle-income countries, which represent 89% of the world’s flood-exposed population9.

To ensure that flood knowledge can be preserved and shared, several regional and global initiatives gather a wide range of flood data11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. However, these databases are often too coarse in their spatial resolution11,13 or data timesteps16,19 to be used in a local flood study9,20. They are also mostly focused on high-income countries in Europe13,14,21,22 or the United States12,15,17. As a result, lower latitude regions, where flood exposure is particularly severe9 and increasing23,24, are largely under-represented in these datasets. This paper makes three main contributions to the critical need for high temporal and spatial resolution flood data. First, the paper provides a detailed analysis of an extreme flood event that occurred on the east coast of Australia in February 2022. Characteristic of extreme weather events observed in lower latitudes in the Asia-Pacific region, the event saw exceptional rainfall totals and streamflow peaks that rank amongst the highest ever recorded in the country. Second, the paper compares this event with a large dataset of historical events in Australia that blends in-situ hydro-climate observations with a national register of flood events. The comparison includes a ‘surprise’ index that evaluates how a single flood alters the 1% AEP flood level. Third, the paper presents several factors that could have led to aggravated flooding levels. The paper concludes with a summary of the main factors governing the 2022 flood, which can serve as a reference for future floods in coastal catchments and humid sub-tropical climates, especially around the Pacific.

Results and discussion

The impossible flood

Australia experienced a series of floods between 2020 and the beginning of 2024 that culminated in February and March 2022 with a regional event that affected the north-east part of the state of New South Wales (NSW) and the south-east part of the state of Queensland (QLD) as shown in Fig. 1a with further location details in Fig. 2. This flood resulted in 24 deaths25,26 and is considered the costliest flood event in Australia, with a total insurance claim estimated at over AUD$6 billion27 and combined infrastructure damage and loss of economic opportunity reaching AUD$7.7 billion in QLD alone28. The flood triggered a state-level enquiry25 in NSW, an enquiry by the Australian Parliament about insurers’ responses to 2022 flood claims29, and several recovery plans, including an investment of AUD$150 million by the Australian government to cover immediate mitigation and resilience activities.

a Historical percentile of root zone soil moisture saturation before the February 2022 flood, b Maximum five-day rainfall, c–f river flow and water level during the flood at the stations of Bellbird Creek, Durrumbul, Eltham and Woodlawn (precise location of Eltham and Woodlawn are given in Fig. 2). 1% AEP values reported in (c)–(f) are obtained from data presented in Section “One of the most surprising floods in recorded Australian history”, except for Woodlawn, where the data is obtained from a local flood study70.

Despite a long history of flooding in the region, including well-documented events such as the 1954 flood, the Brisbane floods in 2010–201130,31 and Cyclone Debbie in 201732,33, the 2022 event is often described by local residents as “impossible”25. For example, on the 28 of February, the water level in the Wilsons River reached 14.4 m in the city of Lismore (see Fig. 1a), breaking the previous record of 12.3 m observed in 1954. The observations at this station started in 191734.

Figure 1 summarises several important characteristics of the 2022 event. Figure 1a shows the saturation level of the topsoil layer simulated by the Australian Water Resources Assessment landscape model35 on the 23 February, just before the main rainfall event started. The plot highlights two areas – one between the cities of Gympie and Sunshine Coast and one between the cities of Gold Coast and Lismore – where root zone soil saturation was above the 90th percentile of its historical distribution (1911–2024). Such initial conditions that were consistently wetter than normal resulted from higher-than-average rainfall since the end of 2019 in the context of an active La Niña phase of the tropical Pacific Ocean36. It is worth noting that this wet phase followed an extreme dry period known as the Tinderbox Drought37 during which the region suffered from intense wildfires.

A first weather system reached the region on the 24 February. The system was generated by a Rossby wave break-up combined with a blocking high in the Tasman Sea and warm and moist air inputs from the Coral Sea25. A second system developed on the 25, affecting southeast QLD, which moved to NSW on the 27th and generated extreme rainfall totals38. Figure 1b shows the maximum five-day total rainfall during February and March 2022. In several areas, the totals exceeded 1000 mm, representing more than half of the mean annual total in the region. A value of 775 mm was recorded in 24 h at the gauging station at Dunoon, located upstream of Lismore36. This value is just below the highest maximum daily rainfall recorded in NSW (809.2 mm)39. Compared to 24-hour design rainfall in the region, daily totals at several stations in the area were above the 0.05% AEP threshold34,40. Remarkably, the areas with the most intense rainfall in Fig. 1b coincides with the highest soil saturation before the flood, as seen in Fig. 1a. In these areas, soil water profiles close to their maximum historical values led to negligible rainfall infiltration and increased overland flow, directly contributing to river flows.

Following record rainfall intensities, river flows across the area reacted quickly, as shown by the hydrographs presented in Fig. 1c–f where streamflow rose by several hundreds of metre cube per second in less than three hours, including a flow rise of 1083 m3s−1 in one hour in Bellbird Creek station. The peak flow measured at the Durrumbul station (Fig. 1d) reached 792 m3s−1 for a catchment area of 34 km2, noting that high-flow measurements at this location are known to be underestimated41. Upstream of Lismore (see Fig. 1e, f, with precise location shown in Fig. 2), the hydrograph shows two distinct peaks: the first on the 25 February and the second on the 28. In addition to reaching water levels never observed before in Lismore, this particular sequence exacerbated the impact of the flood by creating a false sense of security among local communities following the fall of the first peak25.

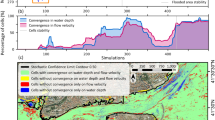

Figure 2 provides more information about the propagation of the flood along a reach of the Wilsons River between the stations of Eltham (upstream) and Woodlawn (downstream), located 22 and 5 km upstream of Lismore, respectively (see inset in Fig. 2). The figure shows the peak time difference between the two stations on the bottom axis, the difference between peak water levels at the upstream and downstream locations (peak attenuation) on the right axis, and the maximum water level reached at the Woodlawn station on the vertical axis. Each point in the figure corresponds to one of 25 historical events in this river reach from 1983 to 2022.

Figure 2 highlights how the dynamics of the 2022 flood (coloured in red) differed from other historical floods. In addition to reaching the highest water levels (vertical axis), the time difference between upstream and downstream was negative in 2022. In other words, the peak occurred first at the downstream end of the reach in Woodlawn, and then later at the upstream end of the reach in Eltham. This was unexpected because flood propagation generally delays downstream peaks. However, intense localised rainfall falling in the lower part of the catchment just north of Lismore (as seen in Fig. 1b) generated local runoff that reached the downstream station before the upstream flood wave arrived, leading to the downstream peak occurring first. Figure 2 also reveals that the 2022 peak attenuation (right axis) was the lowest, with a value close to 3 m, compared to earlier floods where attenuation was above 5 m. The combination of negative peak time difference with reduced attenuation suggests that forecasting the 2022 flood dynamic based on data from the Eltham upstream station was particularly challenging, partly explaining the difficulty local communities and emergency response teams faced during this event25.

One of the most surprising floods in recorded Australian history

The facts highlighted in the previous section set the 2022 flood apart. To assess the significance of this flood at the national level in Australia, observed flood data were collected at 1094 streamflow gauging stations across the country with records starting from 1950 (see data and code availability for details). These stations were selected based on a range of quality metrics described in Supplementary Note 1. Annual instantaneous peak flow maximums were identified for each river flow time series, leading to 43,946 events, referred to as “site events” in the rest of the paper. Subsequently, site events were grouped into broader events, such as the 2022 flood, referred to as “regional event” as presented later in this section.

Figure 3a shows the peak flow from each site event against the catchment area of the corresponding site. Peak flow data alone are insufficient to characterise flood regimes42. Consequently, Fig. 3b compares these peak values with an estimate of flood volume, computed as the annual maximum runoff total over ten consecutive days. In Fig. 3a, 12 site events corresponding to the 2022 regional event (red points) exceed the 99% percentile line (black) computed from a quantile regression43 fitted over the whole dataset, while four of these site events are on, or close to, the maximum envelope of the entire dataset (dotted line). In other words, the 2022 flood includes some of Australia’s most extreme site events. In addition, 11 site events from 2022 are located above the 99% line derived from floods in the United States12 (violet dashed line), which confirms the international significance of the 2022 flood. The comparison between flood peaks and volumes shown in Fig. 3b reveals that 19 site events from 2022 are located between the 95% and 99% probability region, while 3 are outside of the 99% region. This result highlights that 2022 was extreme in terms of both peak and volume at many sites across the region. More precisely, the 2022 points appear clustered along the right side of the iso-probability contours shown in Fig. 3b. This fact suggests that 2022 volumes were among the highest ever observed in Australia compared to other site events with similar bivariate probability.

Both panels show 42,946 site events in Australia (grey dots). Sites affected by the 2022 regional flood are highlighted in red. A quantile regression with catchment area as a predictor is used to draw the “99% AUS” line in (a). The curve “Max AUS” corresponds to the maximum envelope of all points shown in (a). The line “99% US” is obtained from O’Connor and Costa12. Kernel Density Estimates (KDE) are used in (b) to draw contour lines corresponding to areas with 90%, 95% and 99% probability mass.

Despite the extreme nature of most 2022 points in Fig. 3, certain site events not pertaining to the 2022 flood, shown as grey dots, can be seen to reach higher peak flows and volumes. However, Fig. 3 does not tell if these more extreme points are related to broad regional floods with a similar impact as 2022, or if they are isolated and independent events. This point raises the question of defining regional floods, recognising that large-scale events invariably show spatial heterogeneity. For example, certain points in Fig. 3 pertaining to the 2022 flood are not particularly extreme (i.e. well below the 99% lines in Fig. 3a or in the centre of iso-probability contours in Fig. 3b), suggesting that the event’s intensity varied across the affected region. This fact can also be deduced from Fig. 1b, which shows that rivers located west of Lismore received lower rainfall totals than those recorded upstream of Lismore (e.g. stations of Eltham or Woodlawn located in Fig. 2b) or around Gympie (Bellbird Creek).

To compare the 2022 flood with past regional events, a grouping of site events was undertaken based on 52 regional floods identified by the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience44, using additional information from the Historical Normalised Catastrophe List from the Insurance Council of Australia45. The result of this grouping is shown in Fig. 4 for the 2010 flood in QLD, which is considered one of the most notable recent floods in Australia30,31, and for the 2022 flood. Although it is based on a published flood list, it is acknowledged that this selection process remains subjective. In addition, the number of site events selected varies depending on the extent and duration of the regional event, as can be seen in Fig. 4 where the 2010 flood includes 103 site events against 61 for the 2022 flood. Further details on regional events, including their most frequent months of occurrence, are provided in Section “Methods” of the paper and in Supplementary Note 2.

Panel a shows the sites affected by the 2010 Queensland flood while Panel b focuses on the 2022 flood discussed in this paper. The red rectangle defines the spatial window associated with each regional event. Site events selected within these two regional events are coloured according to their specific instantaneous peak flow as shown in the legend. More information about each regional event can be obtained from the link to the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience44 website indicated at the bottom of each figure.

Based on the grouping described above, a quantitative comparison of regional events is undertaken based on a “surprise index”. This index is computed for each site as the relative change between the 1% AEP estimated from all historical data available at the site and the 1% AEP value estimated from the same dataset but excluding one event (e.g., 2022). The index measures how a single event can “surprise” local flood managers by shifting the 1% AEP levels and therefore affect the level of risk protection provided by flood defence infrastructure. Intuitively, removing one extreme flood from the fitting data is expected to shift down the distribution of design floods, leading to a lower 1% AEP value compared to a fit where all data are used, and, hence, to a positive surprise index. Figure 5 presents the distribution of the surprise index for site events grouped as per 52 regional events presented sequentially along the x-axis. White dots represent the mean index value for each regional event.

The index is computed for a maximum specific instantaneous peak flow and b ten-day total runoff. The bars show the index’s 25–75% percentile ranges for each regional event. The mean index is shown as a white circle. Items corresponding to the top four regional events, excluding 2022, are coloured in purple, and items related to the 2022 event are coloured in red.

Figure 5 reveals that the 2022 flood has the highest mean surprise index for ten-day runoff totals, reaching a value of 0.16. In other words, the 1% AEP design flood hydrographs estimated after the 2022 event are likely to see an increase in flood volumes (estimated here as 10 days total runoff) by 16% on average across the affected region, thus increasing flood hazard levels substantially compared to the pre-2022 situation. Note that the surprise index exceeds 30% for certain sites during the 2022 event (see distribution of red points in Fig. 5) leading to a similar increase in 1% AEP values, and hence a pronounced impact on protection levels offered by flood defence infrastructure. This result also confirms the extreme nature of flood volumes during the 2022 flood, as seen in Fig. 3. Similar impacts of record-breaking events on flood frequency fitting have been reported46, but they have not been systematically measured as is done in Fig. 5.

It is noteworthy that the 2022 event ranks third in terms of the mean index for peak flow with a surprise index mean of 0.07 (Fig. 5.a). Two other events, the Victoria floods in January 2011 (mean of 0.11) and a flood that affected the Kimberley region in Western Australia in March 2011 (mean of 0.10), reached higher index values. This result highlights the importance of considering multiple metrics beyond peak values in analysing flood events.

It could have been worse, so what’s next?

Two elements could have exacerbated the 2022 event. First, the spatial extent of the weather system was centred on the eastern parts of the Richmond catchment and upstream parts of the Mary catchment, as shown in Fig. 1.b, which means that the rainfall event covered an area of less than 40,000 km2. In contrast, other floods, such as Cyclone Debbie in 2017, affected most of the east coast of Australia, an area twenty times larger.

Second, ocean conditions could have made the 2022 flood worse close to the outlet of the Richmond River (orange line in Fig. 1a) into the Pacific Ocean. Analysis of ocean tide data reveals that the storm surge generated by low atmospheric pressure peaked several hours before the arrival of the flood wave34. This asynchronicity prevented further elevation of water levels in the lower parts of the Richmond catchment.

In terms of flood process typology, four elements characterise the 2022 event: (1) soil conditions with saturation levels above their 90% historical percentile following several months of higher-than-average rainfall, (2) a localised rainfall cell concentrated upstream of the towns of Lismore and Gympie leading to 24 h totals above 750 mm, (3) a multi-peak streamflow response and record flood volumes over a ten-day period, (4) an ocean storm surge that occurred before the flood peak reached the Richmond River mouth. These four elements could be used to build alternative scenarios, such as a large-scale and extreme flood affecting the east coast of Australia, with an approach similar to that developed to estimate the impacts of an intense winter storm scenario (called ArkStorm) for the United States West Coast47.

The 2022 flood had a major impact on several aspects of flood management in Australia: first, it highlighted the vulnerability of observation networks to such extreme hydro-climate conditions. In response, the Australian Government initiated a review and a 10-year upgrade program of flood warning networks across Australia48. Second, the record flood levels and fast propagation times highlighted in Section “Results and discussion” hindered rescue operations25, which prompted the Government of NSW to review the organisation of local emergency services and enhance the role of local communities in responding to natural disasters49. Third, the results presented in Section “Results and discussion” highlighted the regional footprint of a flood like 2022, which goes beyond administrative boundaries that often determine flood risk management policies. As a result, the Australian Government funded a program to estimate flood risk at the scale of the entire Richmond catchment (which includes the Wilsons River) using a single integrated hydrodynamic model50. Finally, Section “One of the most surprising floods in recorded Australian history” of our paper showed that predefined flood design levels, such as the 1% AEP values, can change considerably following a major event such as 2022. These findings confirm the need to abandon a deterministic approach in flood risk assessment51, which is bound to experience bad “surprises” such as 2022, and move to a broader risk-based decision framework.

Methods

The sources of data used in this research are listed in Section “Data availability”. It is acknowledged that daily rainfall data obtained from a national product that was used to draw Fig. 1a remains insufficient to capture sub-daily flood dynamics. In line with recommendations following the 2022 event34, the development of a sub-daily national product is currently underway52, which constitutes a promising avenue for future flood research in Australia. The limitations associated with streamflow data used throughout the paper are twofold: first, as can be seen in Fig. 4, few streamflow stations are available in Australia’s north and north-west. Despite their high cyclonic activity, these regions exhibit a low population density, which challenges the creation and maintenance of measurement networks. Second, the measurement of extreme streamflow values remains a highly uncertain process53. Efforts detailed in Supplementary Note 1 were made to select high-quality stations. Nonetheless, the large uncertainty associated with streamflow values during extreme floods, sometimes exceeding 50%, must be acknowledged.

The data presented in Fig. 3 are the annual maximums of instantaneous streamflow and ten-day runoff for each of the 1094 sites in our dataset following the Australian Rainfall and Runoff guidelines (ARR) adopted for most flood studies in Australia54.

The specific peak flow displayed in Fig. 3a is obtained by dividing the annual maximum streamflow by the corresponding catchment area, as supplied by data providers (see Section “Data availability”). When missing, this area is estimated by deriving the catchment boundaries using the Geofabric terrain analysis data produced by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology55.

For each site event, the maximum runoff over \(N\) days is obtained by maximising the total streamflow computed from hourly data over sliding periods of \(24\) h, including the timing of the peak. The total streamflow computed through this process is subsequently divided by the catchment area to obtain total runoff.

The space and time windows shown in Fig. 4 are obtained by combining information from the list of Australian Disasters44 and the Historical Normalised Catastrophe List from the Insurance Council of Australia45. These windows permit the identification of site events whose peak flow falls within the corresponding space/time region (see data and code availability for details). 56 regional events were initially identified, but given limited data availability for 4 events, the list was subsequently reduced to 52 events.

The surprise index presented in Fig. 5 is computed in three steps. In a first step, for each variable displayed in Fig. 5 and each of the 1094 sites, the generalised extreme value (GEV) distribution is fitted to an annual maximum series containing all available data points. The fitting follows the Bayesian calibration process described in the Australian Rainfall and Runoff guidelines54, where the three GEV parameters are sampled from their posterior distribution using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo method (MCMC). The likelihood function of this statistical model given a series of annual maximums \({\left\{{y}_{i}\right\}}_{i=1,\ldots T}\) is

where \(\theta =\{\tau ,\alpha ,\kappa \}\) is the GEV parameter vector. A flat prior is assumed for the location \((\tau )\) and scale (\(\alpha\)) parameters while a Gaussian prior with mean 0 and standard deviation 0.256 is used for the shape parameter (\(\kappa\)). The fitting is concluded by sampling 10,000 parameter sets and estimating the 1% AEP as the average of its posterior distribution57:

where \({y}_{1 \% }\) is the 1% AEP value, \({N}_{S}\) is the number of samples, \({\theta }_{j}\) is the \({j}^{{th}}\) parameter sample and \(Q\) is the quantile function of the GEV distribution given by

where p is a given probability. The samples from the GEV posterior are generated using the No-U-Turn MCMC sampler implemented in the Stan programming language58. The main reason to select a Bayesian approach here is to incorporate the uncertainty due to limited sample size and compare results across sites with varying record duration. This cannot be done with more traditional fitting approaches, such as the L moment matching method59. It is highlighted that Eq. (2) provides a point estimate of \({Q}_{1 \% }\), which is less informative than credible intervals that can be derived from the same parameter samples. We chose to restrict our analysis to a point estimate such as Eq. (2) to simplify the presentation of results and remain comparable to more traditional and deterministic estimates of 1% AEP events. Further information can be obtained from the supporting dataset60 in which credible intervals for 1% AEP values are provided.

In a second step, the fitting process described above is repeated using all annual maximums \(\{{y}_{i}\}\), except the \({j}^{{th}}\) year. This restricted fitting leads to a different predictive estimate of the 1% AEP, denoted by \({Q}_{1 \% }^{(-j)}\). Finally, the surprise index for year \(j\) is computed as

This value is the relative log-difference61 between the 1% AEP value from the full fit and that from the \({j}^{{th}}\) restricted fit. Relative log-difference is preferred to the classical expression of relative change involving the ratio of \({Q}_{1 \% }\) over \({Q}_{1 \% }^{\left(-j\right)}\) as log-difference is symmetrical and more stable for small values of \({Q}_{1 \% }^{\left(-j\right)}\).

To test the sensitivity of the whole approach to the choice of the probability distribution, the whole process is conducted using the Log-Pearson III probability distribution. Results are similar to the ones obtained with the GEV distribution and hence only included in Supplementary Note 3. Finally, another fitting is implemented where the lowest 20% of annual maximums are considered as left-censored in the likelihood function to mitigate the impact of low values on the fitting following the ARR approach. Here again, results are similar to the original fitting as shown in Supplementary Note 3.

Data availability

The rainfall data presented in this study are extracted from the interpolated gridded rainfall product of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology62. The streamflow data for 1094 sites are obtained from state and territory governments across Australia, including New South Wales63, Northern Territory64, Queensland65, South Australia66, Tasmania67, Victoria, and Western Autralia68, and from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology water data online website69. All data used in this paper can be downloaded from the associated code repository60.

Code availability

All code used in this paper can be downloaded from the associated code repository60.

References

CRED. The Human Cost of Disasters: An Overview of the Last 20 Years (2000-2019). 30 https://www.undrr.org/publication/human-cost-disasters-overview-last-20-years-2000-2019 (2020).

Bentivoglio, R., Isufi, E., Jonkman, S. N. & Taormina, R. Deep learning methods for flood mapping: a review of existing applications and future research directions. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 26, 4345–4378 (2022).

Bates, P. Fundamental limits to flood inundation modelling. Nat. Water 1, 566–567 (2023).

Cheng, L. & AghaKouchak, A. Nonstationary Precipitation Intensity-Duration-Frequency Curves for Infrastructure Design in a Changing Climate. Sci. Rep. 4, 7093 (2014).

Santiago-Collazo, F. L., Bilskie, M. V. & Hagen, S. C. A comprehensive review of compound inundation models in low-gradient coastal watersheds. Environ. Model. Softw. 119, 166–181 (2019).

Menne, M. J., Durre, I., Vose, R. S., Gleason, B. E. & Houston, T. G. An Overview of the Global Historical Climatology Network-Daily Database. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 29, 897–910 (2012).

Mishra, A. K. & Coulibaly, P. Developments in hydrometric network design: A review. Rev. Geophys. 47, RG2001 (2009).

Tate, E., Rahman, M. A., Emrich, C. T. & Sampson, C. C. Flood exposure and social vulnerability in the United States. Nat. Hazards 106, 435–457 (2021).

Rentschler, J., Salhab, M. & Jafino, B. A. Flood exposure and poverty in 188 countries. Nat. Commun. 13, 3527 (2022).

Rentschler, J. et al. Global evidence of rapid urban growth in flood zones since 1985. Nature 622, 87–92 (2023).

Herschy, R. W. The world’s maximum observed floods. Flow. Meas. Instrum. 13, 231–235 (2002).

O’Connor, J. E. & Costa, J. E. Spatial distribution of the largest rainfall-runoff floods from basins between 2.6 and 26,000 km2 in the United States and Puerto Rico. Water Resources Res. 40, W01107 (2004).

Barredo, J. I. Major flood disasters in Europe: 1950–2005. Nat. Hazards 42, 125–148 (2007).

Uhlemann, S., Thieken, A. H. & Merz, B. A consistent set of trans-basin floods in Germany between 1952 and 2002. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1277–1295 (2010).

Gourley, J. J. et al. A Unified Flash Flood Database across the United States. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 94, 799–805 (2013).

Do, H. X., Gudmundsson, L., Leonard, M. & Westra, S. The Global Streamflow Indices and Metadata Archive (GSIM) – Part 1: The production of a daily streamflow archive and metadata. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 765–785 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. A multi-source 120-year US flood database with a unified common format and public access. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 3755–3766 (2021).

Saharia, M. et al. India flood inventory: creation of a multi-source national geospatial database to facilitate comprehensive flood research. Nat. Hazards 108, 619–633 (2021).

Kratzert, F. et al. Caravan - A global community dataset for large-sample hydrology. Sci. Data 10, 61 (2023).

Jones, R. L., Guha-Sapir, D. & Tubeuf, S. Human and economic impacts of natural disasters: can we trust the global data?. Sci. Data 9, 572 (2022).

Blöschl, G. et al. Changing climate both increases and decreases European river floods. Nature 573, 108–111 (2019).

Bertola, M. et al. Megafloods in Europe can be anticipated from observations in hydrologically similar catchments. Nat. Geosci. 16, 982–988 (2023).

Jongman, B., Ward, P. J. & Aerts, J. C. J. H. Global exposure to river and coastal flooding: Long term trends and changes. Glob. Environ. Change 22, 823–835 (2012).

Tellman, B. et al. Satellite imaging reveals increased proportion of population exposed to floods. Nature 596, 80–86 (2021). 2021 596:7870.

Parliament of NSW. Response to Major Flooding across New South Wales in 2022. (Parliament of NSW, Legislative Council, Select Committee on the Response to Major Flooding Accross New South Wales in 2022, 2022).

Queensland Reconstruction Authority. 2021–22 Southern Queensland Floods - State Recovery and Resilience Plan 2022–24. https://www.qra.qld.gov.au/2021-22-Southern-Queensland-Floods#State-Recovery-Plan (2022).

Insurance Council of Australia. Historical Normalised Catastrophe - January 2024. Insurance Council of Australia https://insurancecouncil.com.au/industry-members/data-hub/ (2024).

Deloitte. The Social, Financial and Economic Costs of the 2022 South East Queensland Rainfall and Flooding Event. 33 https://www.qra.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-07/dae_report_-_south_east_queensland_rainfall_and_flooding_event_-_8_june_2022.pdf (2022).

Commonwealth Parliament. Flood Failure to Future Fairness - Report on the Inquiry into Insurers’ Responses to 2022 Major Floods Claims. https://www.aph.gov.au/floodinsurance (2024).

Chanson, H. The 2010-2011 Floods in Queensland (Australia): Observations, First Comments and Personal Experience. La Houille Blanche 1, 5–11 (2011).

Van den Honert, R. C. & McAneney, J. The 2011 Brisbane Floods: Causes, Impacts and Implications. Water 3, 1149–1173 (2011).

Lenzen, M. et al. Economic damage and spillovers from a tropical cyclone. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 137–151 (2019).

Bruyère, C. L. et al. Physically-based landfalling tropical cyclone scenarios in support of risk assessment. Weather Clim. Extremes 26, 100229 (2019).

Lerat, J., Vaze, J., Marvanek, S. & Ticehurst, C. Characterisation of the 2022 Floods in the Northern Rivers Region. https://doi.org/10.25919/1bcs-e398 (2022).

Vaze, J. et al. The Australian water resource assessment modelling system (AWRA). In: 20th International Congress on Modelling and Simulation, Modelling and Simulation 16, 3015–3021 (2013).

Bureau of Meteorology. Special Climate Statement 76 – Extreme Rainfall and Flooding in South-Eastern Queensland and Eastern New South Wales. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/current/statements/scs76.pdf (2022).

Devanand, A. et al. Australia’s Tinderbox Drought: An extreme natural event likely worsened by human-caused climate change. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj3460 (2024).

Goodwin, D. I. D. Weather behind the Eastern Australian floods – February to April 2022. Risk Frontiers https://riskfrontiers.com/insights/eastern-australian-floods-february-april-2022/ (2022).

Bureau of Meteorology. Rainfall and temperature records. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/extreme/records.shtml (2025).

Green, J., Beesley, C. & Podger, S. New design rainfalls for Australia. In: 36th Hydrology and Water Resources Symposium,Engineers Australia, 1261–1268 (2015).

BMT WBM. North Byron Shire Flood Study Report. https://flooddata.ses.nsw.gov.au/flood-projects/north-byron-shire-flood-study (2016).

Merz, R. & Blöschl, G. A process typology of regional floods. Water Resources Res. 39, 1340 (2003).

Wasko, C. & Sharma, A. Quantile regression for investigating scaling of extreme precipitation with temperature. Water Resour. Res. 50, 3608–3614 (2014).

National Emergency Management Agency. Australian disasters. https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/collections/australian-disasters/ (2024).

Insurance Council of Australia. Historical Normalised Catastrophe list (Insurance Council of Australia, 2025).

McDonald, W. M. & Naughton, J. B. Impact of hurricane Harvey on the results of regional flood frequency analysis. J. Flood Risk Manag. 12, e12500 (2019).

Porter, K. et al. Overview of the ARkStorm Scenario. Open-File Report https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/ofr20101312 (2011).

Bureau of Meteorology. Flood Warning Network Upgrades. http://www.bom.gov.au/australia/flood/FWIN.shtml (2024).

NSW Government. NSW Government Response to the NSW Independent Flood Inquiry. https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/noindex/2022-08/NSW_Government_Reponse.pdf (2022).

CSIRO. Northern Rivers Resilience Initiative. https://www.csiro.au/en/research/disasters/floods/Northern-NSW-Resilience-Initiative (2025).

Merz, B. et al. Floods and climate: emerging perspectives for flood risk assessment and management. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1921–1942 (2014).

Velasco, Forero C., Pudashine, J., Robinson, J. & Seed, A. Radar-based ensemble forecasts to enhance flood forecasting and warnings in Australia. In: HWRS2023: Hydrology & Water Resources Symposium, 760–764, https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.T2024051500013091362438995 (2023).

World Meteorological Organization. Guidelines for the Assessment of Uncertainty for Hydrometric Measurement. WMO-No. 1097. http://library.wmo.int/records/item/55462-guidelines-for-the-assessment-of-uncertainty-for-hydrometric-measurement (2017).

Kuczera, G. & Francks, S. At Site Flood Frequency Analsysis, Chapter 2, Book 3 in Australian Rainfall and Runoff. (2019).

Australian Bureau of Meteorlogy. Australian Hydrological Geospatial Fabric (Geofabric), Product Guide. http://www.bom.gov.au/water/geofabric/documents/v3_0/ahgf_productguide_V3_0_release.pdf (2015).

Renard, B. et al. Data-based comparison of frequency analysis methods: A general framework. Water Resour. Res. 49, 825–843 (2013).

Kuczera, G. Comprehensive at-site flood frequency analysis using Monte Carlo Bayesian inference. Water Resour. Res. 35, 1551–1557 (1999).

Stan Development Team. Stan Modeling Language Users Guide and Reference (Stan Development Team, 2024).

Hosking, J. R. M. & Wallis, J. R. Regional Frequency Analysis: An Approach Based on L-Moments (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511529443 (1997).

Lerat, J. Data and code supporting the analysis of the 2022 flood event. CSIRO. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15208254 (2024).

Tornqvist, L., Vartia, P. & Vartia, Y. O. How Should Relative Changes Be Measured?. Am. Statistician 39, 43–46 (1985).

Jones, D. A., Wang, W. & Fawcett, R. High-quality spatial climate data-sets for Australia. Aust. Meteorological Oceanographic J. 58, 233 (2009).

WaterNSW. Real-time water data. https://realtimedata.waternsw.com.au/water.stm (2025).

Northern Territory Government. The NT Water Data Portal. https://ntg.aquaticinformatics.net/ (2025).

Queensland State Government. Water Monitoring Information Portal. https://water-monitoring.information.qld.gov.au/ (2025).

Government of South Australia. Water Data SA. https://water.data.sa.gov.au/ (2025).

Government of Tasmania. Water Information Tasmania Web Portal. https://portal.wrt.tas.gov.au/Data (2025).

Government of Western Australia. Water Information Reporting. https://wir.water.wa.gov.au/Pages/Water-Information-Reporting.aspx (2025).

Australian Bureau of Meteorlogy. Water Data Online. (2025).

Engeny Water Management. Lismore Floodplain Risk Management Study. https://flooddata.ses.nsw.gov.au/flood-projects/lismore-floodplain-risk-management-study (accessed 28/2/2023) (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Australian Government, National Emergency Management Agency, as part of the Northern Rivers Resilience Initiative. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Matt Gibbs, CSIRO Australia, Cuan Petheram, CSIRO Australia, Vazken Andreassian, INRAE France and Margie Beilharz, The Open Desk, for their comments, which helped improve the manuscript substantially.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Julien Lerat contributed to the conception of the work, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, development of code used in the work, and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. Jai Vaze contributed to the conception of the work and substantively revised the initial version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Rahim Barzegar and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lerat, J., Vaze, J. How February 2022 redefines extreme floods in Australia. Commun Earth Environ 6, 378 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02307-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02307-z