Abstract

As global change reshapes ecosystems, establishing conservation priorities is crucial for managing threatened areas with limited resources. Biodiversity hotspots, often defined by high endemism, are key in conservation management. However, these may not capture other dimensions of biodiversity, including functional and phylogenetic diversity or knowledge from Indigenous communities. Here, we demonstrate that different metrics identify different hotspots using simulated plant communities as a case study. We compiled existing data on 318 plant species, including functional trait data and Traditional Ecological Knowledge on Indigenous plant names and uses. We simulated 100,000 communities by randomly assembling species that naturally co-occur within an ecoregion, and calculated taxonomic, phylogenetic, functional, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge-based biodiversity metrics. The metrics cluster into two groups based on shared hotspot identification, with phylogenetic and functional metrics distributed between groups, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge-based metrics aligning with some metrics, but not all. This suggests that integrating Traditional Ecological Knowledge into conservation planning can expand the scope of biodiversity assessments and help recognize places of cultural significance that might otherwise be overlooked.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In an era of global climate change, habitat loss, and species extinction, conservation strategies are crucial for minimizing global biodiversity loss. Identifying global areas of primary concern is essential for prioritizing biodiversity conservation efforts, as time and financial resources are typically limiting factors1,2. To this end, biodiversity hotspots are usually suggested as conservation priorities, which have been defined as habitats containing high levels of endemism that are under high human threat3. This type of conservation priority alone has mobilized millions of dollars to fund conservation1,4. However, defining conservation priorities as biodiversity hotspots with high degrees of endemism may overlook geographic regions harboring biodiversity that lies outside of the traditional definition of a biodiversity hotspot, including areas with exceptional taxonomic diversity, phylogenetic diversity (PD);5 functional diversity (FD);6 and socioecological values from Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)7. Incorporating a more comprehensive set of biodiversity dimensions may provide flexibility in decisions regarding how to measure biodiversity and allow managers and policymakers to refine conservation priorities. Additionally, and importantly, incorporating TEK into conservation planning will help create effective conservation strategies that are participatory, sustainable, and socially just8,9—if done with respect for Indigenous data sovereignty8,9,10.

Two dimensions of biodiversity originating from Western scientific views, PD and FD, are influencing and being incorporated into conservation priorities and management decision making11,12. PD is the sum of all the branch lengths on a phylogenetic tree and quantifies the evolutionary relationship and shared evolutionary history among a set of species. Thus, PD is of conservation interest as an additional tool for measuring biodiversity within a community13. For instance, incorporating PD into conservation decision-making for mammals has been able to identify species with high PD that are not usually recognized as conservation priorities14 and, in aquatic invertebrate communities, has been used to inform management decisions, particularly when obtaining ecological trait data is difficult15.

FD represents the diversity and distribution of functional traits within a set of species, including morphological, physiological, and phenological properties of species that directly impact fitness. Assessing FD is relevant because traits provide information about ecosystem services16 and, when aggregated to the community level, offer insights into ecosystem stability and resilience to disturbances17,18. Moreover, FD can explain variation in ecosystem function even when taxonomic richness does not17,18,19. Traits are often conserved along evolutionary lines, allowing phylogenies to serve as a practical substitute for understanding functional composition in the absence of specific trait information20. However, there is increasing evidence that PD and FD do not necessarily align, highlighting the importance of considering PD and FD (in addition to taxonomic diversity) as separate aspects of biodiversity that may need separate conservation strategies6,21,22,23.

A long-overlooked measure of biodiversity in scientific literature is the knowledge of ecological communities and interactions held by local Indigenous communities. Indigenous perspectives often see nature as an intricate, interconnected web of relationships rather than as a set of isolated, unrelated objects24,25, and Indigenous land stewardship principles are often rooted in a deep understanding of local ecosystems26; a concept referred to as TEK27,28. Incorporating TEK into conservation policies and decision-making has several advantages over utilizing information gathered only from Western science practices, including access to location-specific knowledge, increased knowledge of environmental connections, and local capacity building29,30. Successful conservation of natural resources requires collaborative efforts on small local scales, incorporating local knowledge that is then integrated across an extensive network, transcending ownership boundaries, and including those whose activities impact the ecosystem31.

There are a variety of metrics that come from Traditional Knowledge that can be invaluable to measuring biodiversity and identifying biodiversity hotspots, including (but not limited to): folk taxonomy and systematics (identification, classification, and nomenclature applied to organisms by a particular group of people);32 traditional phenological knowledge, local knowledge of plants, animals, and landscapes, socio-economic importance/uses, and linguistic diversity30,33,34,35. Name diversity is a measure of Indigenous naming systems that refers to the names and number of names associated with an organism. A single species may be associated with multiple names when there are different names for various plant tissues, life stages, and morphs. Similarly, the number of identified uses for a single plant can be quite large, as different plant tissues (such as the leaf, fruit, or roots) may be used for a variety of practices, such as medicine, food, clothing dye, or building36. While some studies have incorporated TEK into conservation management strategies and in identifying biodiversity hotspots37,38, it remains an undervalued resource despite its value, and to our understanding, TEK metrics such as species name and number of uses are not often considered when identifying biodiversity hotspots or in combination with other metrics.

Incorporating various perspectives on biodiversity can guide efforts in effective resource management when prioritizing habitats for conservation39,40. In addition to the loss of land tenure due to colonization41, Indigenous knowledge has been historically disregarded when planning areas for conservation; however, in recent decades, there has been an increased awareness of the need to engage with Indigenous communities for conservation efforts, management, and policy decisions42,43,44. Here, we expand the multifaceted Western approach to biodiversity hotspot identification by incorporating hotspots identified by TEK.

Plant communities were simulated from a list of 318 species native to the PNW, for which information on Indigenous names and traditional uses is available with the consent of local peoples. Using simulated plant communities allowed for flexibility in our data sources (i.e., acquiring TEK data) while also allowing us to illustrate our conceptual framework, which employs both Western Science and TEK metrics to identify biodiversity hotspots. These metrics included, taxonomic species richness, phylogenetic species richness (PSR), phylogenetic species variability (PSV), phylogenetic Rao’s entropy, Faith’s metric, functional richness, functional Rao’s entropy, functional dispersion, number of Indigenous names, and number of Indigenous uses (for definitions and citations, see Table 1). Our comparison of hotspots from these Western science- and TEK-based biodiversity metrics revealed similarities and dissimilarities across simulated communities. This has important implications for conservation planning, sustainable ecosystem management, and social justice, as areas of unique biocultural value may get lost when using Western science-based metrics as the sole indicator for policy decisions.

Results and discussion

Biodiversity metrics from Western science frequently led to different hotspot identifications

The distribution pattern of biodiversity values for the simulated communities varied substantially across metrics, even across those representing the same dimension of biodiversity (e.g., functional richness vs. functional dispersion, both metrics of FD; Fig. 1). As a result, some diversity metrics suggested that biodiversity hotspots (defined as the top 5% of data values; see Methods) featured uniquely high biodiversity, while other metrics suggested that hotspots had biodiversity levels close to the average of all communities. This implies that biodiversity hotspots might be undervalued should one of the latter diversity metrics be used as their sole descriptor.

Distributions of biodiversity metric values across one thousand patches for a single simulation run. The red region indicates biodiversity values exceeding the 95% cutoff, above which a patch is designated a hotspot. The black dotted line indicates the mean biodiversity level of patches in the region. Colored panels indicate the type of metric: black for taxonomic, green for TEK, purple for functional, and orange for phylogenetic. The height of each distribution is scaled to a maximum of one.

Measures of precision and sensitivity (see Methods for definition and calculation) indicate that different biodiversity metrics may identify different simulated communities as hotspots. The overlap between hotspots identified by PSR and phylogenetic Rao’s entropy was among the strongest, with 94% of the hotspots identified by phylogenetic Rao’s entropy also being PSR hotspots (precision values of 0.94; Fig. 2). Taxonomic species richness and PSR also commonly identified the same hotspots (precision of 0.88 and 0.86, respectively; Fig. 2). In contrast, Faith’s PD metric was less likely to identify the hotspots determined from taxonomic species richness (precision of 0.28; Fig. 2), while functional richness shared a moderate amount of overlap with hotspots determined from phylogenetic or taxonomic species richness (precision values of 0.52 and 0.54, respectively). These observations demonstrate that different dimensions of biodiversity will only sometimes identify the same simulated communities as hotspots, aligning with previous research demonstrating that while taxonomic species richness and PSR often correlate, there is variability in the hotspots identified from taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic dimensions of biodiversity5,45.

The pairwise precision (A) and sensitivity (B) of biodiversity metrics for identifying biodiversity hotspots are shown as a heatmap (with blue indicating more shared hotspots and white indicating fewer shared hotspots). When making comparisons, the baseline indices are treated as identifying the true list of hotspots to which the list derived from the comparison indices is then compared. See Table 1 for complete definitions of the biodiversity metrics. Colored text indicates the type of metric: black for taxonomic, green for TEK, purple for functional, and orange for phylogenetic.

Frequently, there were large mismatches in the identification of hotspots (which we define as precision and sensitivity being below 0.5). For example, none of the hotspots derived from functional dispersion and PSV corresponded with functional or PSR, taxonomic species richness, both TEK-based metrics, or functional and phylogenetic Rao’s entropy. Other work has reported similar patterns, where global measures of biodiversity from taxonomic species richness and functional richness align more closely with one another, but other FD metrics show distinct patterns of biodiversity46,47. While our results are based on simulated communities, they support previous studies warning that one dimension of biodiversity cannot necessarily serve as a proxy for another to inform conservation prioritization21,22. For example, prioritizing the protection of species-rich communities of birds may not be an effective strategy for conserving FD45. An integrative, multifaceted approach is needed, particularly if the goal is to maximize multiple dimensions of biodiversity.

Even among diversity metrics that are thought to represent similar aspects of biodiversity, there was sometimes little correspondence in the identified hotspots. For example, none of the hotspots identified by functional richness were identified as hotspots based on functional dispersion, and vice versa (zero precision and sensitivity). Our results, therefore, indicate that even when conservation goals are focused, it is good practice to quantify multiple metrics for the same dimension of biodiversity.

TEK-based biodiversity hotspots do not align as closely with one another as with some hotspots derived from Western science diversity metrics

More than half of the biodiversity hotspots identified by the two TEK-based biodiversity metrics (number of Indigenous names of plants and their parts and number of traditional uses of plants and their parts) were shared, with a precision of 0.71 (Fig. 2). This overlap may partly be attributed to the positive correlation between the species-specific number of traditional uses and Indigenous plant names (r = 0.44, p < 2.2e-16; Supplementary Fig. 2). Species may have many names when various parts of it are used. Indeed, how plants are named in Indigenous languages often relates to how they are used, in addition to reflecting phenology, environmental patterns, and local ecology48,49. Most plant species had fewer than fifty names and one hundred uses, but several had over 100 names and 200 uses (Supplementary Fig. 2). The highest number of names was associated with Rubus spectabilis, common name Salmonberry, which had a recorded 170 unique names. The highest number of traditional uses was reported for Western redcedar, Thuja plicata, at 368 recorded uses, possibly because of their ability to hybridize and mix with congeners easily.

Interestingly, there was quite a large degree of overlap between several diversity metrics derived from Western science knowledge and Indigenous knowledge. These included taxonomic, functional, and PSR, as well as functional and phylogenetic Rao’s entropy, which all had precision values ranging from 0.55 (functional richness) to 0.86 (taxonomic species richness). However, PSV and functional dispersion never identified the same hotspots as either of the two TEK-based diversity metrics.

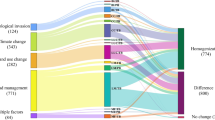

A clustering analysis revealed overlapping patterns between biodiversity hotspot metrics. PSV and functional dispersion formed one group due to shared hotspots, and the remaining biodiversity metrics clustered into a second group (Fig. 3). Most metrics between these two clusters rarely identify the same hotspots, whether measured through precision or sensitivity. Notably, no metric pairs between the two clusters overlapped in their identified hotspots by more than 3% (Faith’s metric and PSR; Fig. 2), with most metrics overlapping by 0%. This underscores the variation in hotspot identification across metrics, highlighting the importance of choosing multiple metrics when possible.

A dendrogram depicting the relatedness of biodiversity metrics according to the level of precision with which they identify the same hotspots. The dendrogram indicates that biodiversity metrics cluster into two major groups. Biodiversity metric names are colored by metric type: black for taxonomic, green for TEK, purple for functional, and orange for phylogenetic.

Outlook and implications for biological conservation

Identifying biodiversity hotspots is key to efficiently allocating resources to preserve ecosystems across the planet. This study shows that choosing a biodiversity metric for identifying hotspots is not neutral: different metrics identify very different hotspots. Biodiversity researchers and policymakers are advised to use various biodiversity metrics and frameworks like two-eyed seeing, recognizing that plant communities are different when viewed through different cultural lenses50. For example, species-poor communities may be of special conservation value if they feature, for instance, a species from a unique phylogenetic branch or with a unique traditional use or cultural value.

In this study, we computed two TEK-based biodiversity metrics. A more holistic view of TEK could include “stories, songs, folklore, proverbs, cultural values, beliefs, rituals, community laws, local language, and agricultural practices, including the development of plant species and animal breeds”51. Quantifying biodiversity is complex52, and even when it is possible to incorporate multiple biodiversity perspectives, culturally meaningful places may still remain undetected53. However, incorporating TEK-based perspectives into conservation planning and decision-making will be essential for the holistic management of threatened and vulnerable ecosystems.

Due to the nature of our simulation study, there are two fundamental aspects to the practice of biological conservation that we could not address, warranting tests of our conceptual framework on real-world data. In this simulation study, scale is undefined, although we recognize it is a critical aspect of conservation and restoration, as different strategies may operate at different spatial scales54,55. The number of shared hotspots identified from TEK- and Western science-based diversity metrics may differ at different spatial scales, especially if the scales of languages and species turnover do not match. Moreover, the dispersal and distribution of culturally important species are partly driven by Indigenous Peoples36, which may contribute to divergent hotspot identifications across scales.

Second, our simulations were based on a list of native species for which we were able to compile information on their Indigenous names and traditional uses. In today’s globalized world, few locations are free from non-native species naturalizing in or invading ecosystems outside their native range. The presence of non-native species may affect TEK- and Western science-based biodiversity metrics differently (and are dependent on spatial scale) and, as a result, lead to different identified hotspots. For example, species richness may increase locally with species invasion56, while TEK-based diversity would decrease or remain the same. Gaps between Western science- and TEK-based metrics could serve as warning signals in conservation practices.

In the Pacific Northwest (PNW), integrative groups are working to describe local ecological knowledge and are calling for studies on how this knowledge can be actively implemented into conservation management31. In the PNW, research has found increased taxonomic and functional plant diversity in regions historically utilized by Indigenous peoples with long-lasting effects on plant diversity for over 150 years57. Globally, scientists and managers should work to build, improve, and sustain collaborations with local and Indigenous communities to produce similar regional datasets and libraries, taking special care to preserve the intellectual property rights of communities35,58,59,60. Overall, we suggest that a multi-metric approach to biodiversity hotspot identification, acknowledging the interconnections between species and cultural practices, is crucial to preserving biological and cultural values36.

Methods

We used the PNW as a case study to simulate plant communities, calculate biodiversity metrics, and identify hotspots. To do so, we compiled a list of native plant species in the PNW for which we curated data on the number of Indigenous plant names and uses, and plant functional trait values. This geographic focal area was chosen because of the availability of multiple TEK sources and sufficient coverage of trait data in existing databases in this region. However, we acknowledge that TEK in the other areas is well-documented and publicly shared with the consent of local people, e.g., ref. 61 in Central Asia, the Rizoma database of native plants in Chile62, the Ewé ethnobotanical database in Brazil63,64 in Australia, traditional uses of plants in New Guinea65, and data on traditional ethnomedicines in Pakistan66.

TEK data

We obtained names of plant taxa from Indigenous communities and language groups from the Names of Native Plant Species in Indigenous Languages of Northwestern North America, Appendix 2B in the book Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge. Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America67. This appendix provides names for native plant species, subspecies and varieties in the PNW, with the names of the Indigenous languages and major dialects listed for each entry. The number of traditional uses associated with each plant taxa was obtained from the Native American Ethnobotany Database68, which stores plant-derived uses (foods, drugs, dyes, and fibers) of Native American Peoples. This database has been curated over the past 25 years and includes uses from 291 Native American Indigenous peoples and 4029 plant species from 243 different plant families across North America. This data curation produced an initial list of 330 plant taxa with recorded numbers of Indigenous names and numbers of traditional uses.

To facilitate linking TEK data to information about traits (see further), taxa were assigned formal binomial nomenclature by the global names resolver function, gnr_resolve, of the taxize package in R, using The Leipzig Catalog of Vascular Plants as the data source69,70,71. We reduced subspecies and varieties to their basic species names in case no synonym was found with this approach. The synonymization process led to unambiguous results for all but four species names in the dataset. These included Cornus unalaschkensis, which had six recorded uses, while its synonym, Cornus canadensis, had forty uses. Additionally, Platanthera stricta had one recorded use, while its synonym, Platanthera dilatata, had two uses. This difference in the number of recorded uses may be due to the species being considered distinct at the time of recording. Therefore, we summed the number of unique uses for these species pairs and assigned that number to the synonym from the Catalog. After accounting for all synonyms, our species list was refined to 318 plant species. Because fine-scale data were not available for all species in the TEK dataset, we were unable to resolve taxa to the level of author name; as such, there is some minor taxonomic uncertainty and thus, a small level of uncertainty for the reported results.

Functional trait data

We used the global trait dataset compiled by ref. 72 as the basis for trait information for the species in our case study. We extracted data on seven continuous vascular plant traits that define the primary axes of variation in plant form and function—plant height (m), leaf area (LA; mm2), leaf nitrogen content per dry mass (Nmass; mg/g), leaf mass per area (LMA; gm2), leaf dry matter content (LDMC; g/g), diaspore mass (SM; mg) and stem specific density (SSD; mg/mm3), as well as one categorical trait-plant woodiness. For species that were missing from the Díaz et al.72 dataset, we extracted functional trait information from the TRY database73. Due to variation between observations in the use of descriptive terminology for plant woodiness, we used a binary level of classification, labeling all species as either woody or not woody. Additionally, all leaf area data for leaflet and leaf were combined into a single leaf area trait. Once this dataset was compiled for all of our plant species, we retained only entries that were single observations or measures of central tendency and discarded entries that only contained extremal estimates for a trait. We then summarized numerical trait values by calculating the mean of each trait for a given species across studies. Note that we treated average values as single observations in this averaging process because sample sizes are unavailable for values reported as averages in the Díaz et al.72 dataset.

The data coverage for our focal species varied substantially across the traits available in the Díaz dataset (Supplementary Table 1). We, therefore, discarded those traits with data coverage for less than 20% of the species list (i.e., SSD, covering only 14% of the species), leaving six traits for functional biodiversity analyses (Supplementary Table 1). Because the retained traits still showed data incompleteness, we used the missForest algorithm from the missForest R package to impute missing trait values with 1000 maximum iterations and 1000 trees per forest74. The missForest algorithm can impute categorical and continuous variables and provides estimates of out-of-bag error for both. We ran the imputation algorithm with and without taxonomic data (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), with and without log-transformed trait data, and by scaling or normalizing the trait data. Ultimately, taxonomic data were included in the final fitting process, and trait values were normalized, as this combination resulted in the lowest out-of-bag error (NRMSE of 0.223 compared to 0.96 for unmodified traits without taxonomic data). A visual comparison of the distributions of trait values in the dataset before and after imputation indicates that the fitted values reasonably match the original dataset (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Simulating plant communities

We created 100,000 simulated plant species communities by sampling species from the curated species list. These communities are by no means representative of real plant assemblies. Still, to increase the probability that species in simulated communities co-occur in natural conditions, we only combine species that grow under similar environmental conditions. More specifically, we only combined species that grow in the same ecoregion, which is defined as the Level II product from the Commission for Environmental Cooperation North American Environmental Atlas map of Terrestrial Ecoregions75. While the PNW has no official boundaries, we defined the area as the region described in Figs. 1-1 of ref. 67 to create a list of ecoregions in the PNW. We then used the BIEN_occurrence_species function from the BIEN package in R76 to determine in which Level II ecoregions the species naturally occur and to create ecoregion-specific species lists.

During simulations, each community was randomly assigned an ecoregion type, L, from the Level II ecoregion types identified in the PNW. The number of species assigned to a community, M, was randomly sampled from a uniform distribution between one and the maximum number of species occurring in the given ecoregion type. To assign species to a community in ecoregion type L with M species, we sampled M species without replacement from the species list for ecoregion type L. By doing this, we assumed equal species abundances within a community. We ran one hundred simulation rounds, each producing a set of 1000 simulated communities. Additionally, we changed the number of patches to assess how robust our results are to the simulation parameter choice for number of patches. At 10,000 patches (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6) we see more or less the same groupings as when we simulate 100 patches (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). We acknowledge that the simulated plant communities do not represent real-world communities and that more advanced simulation tools exist to deal with some of the problems of missing or incomplete data77,78. However, the goal of these analyses is to serve as an illustration of our conceptual idea, as such, simulating more realistic plant communities was outside the scope of this study.

Calculating dimensions of biodiversity

We quantified multiple dimensions of biodiversity—based on Western and TEK—for each of the 100,000 simulated communities. Table 1 shows the names, definitions, and citations for all biodiversity metrics used in this study.

First, we determined taxonomic diversity. Because we did not simulate species abundances, species richness was calculated as the sole measure of taxonomic biodiversity. Species richness was calculated directly as the number of unique species in a community.

Second, we generated a phylogenetic tree for the species list to calculate PD using the V.PhyloMaker2 R package79. As the backbone mega-tree, we used the GBOTB.extended.LCVP.tre mega-tree, which combines the GBOTB phylogeny for seed plants80 and the clade of pteridophytes from the phylogeny of ref. 81, and is standardized following the botanical nomenclature of the Leipzig catalog of vascular plants71. Tips for a new genus were bound to this mega-tree using scenario 3, the most commonly used scenario according to ref. 79. Of the 318 species in our dataset, 73 species were bound to the backbone phylogeny. One species, Pterospora andromedea, failed to bind to the mega-tree (R package function error), so it was excluded from all community composition simulations. The mega-tree was subsequently pruned to the available species list using the picante R package82. Next, we calculated four commonly used PD metrics for each simulated community: PSR, PSV, phylogenetic Rao’s entropy, and Faith’s PD83.

Third, we used the trait dataset (compiled from data sets72,73 with missing values imputed; see above) to calculate three metrics of FD for each simulated community, using the fundiversity R package84,85: functional Rao’s entropy83, functional richness, and functional dispersion83). While these FD metrics are typically applied to abundance data, they are also applicable to presence/absence data84,86. To moderate the weight of species with extreme trait values, leaf area, LDMC, plant height, and diaspore mass were log-transformed. All traits were standardized to a zero mean and unit variance.

Fourth, TEK-based biodiversity metrics included the number of unique names and the number of identified uses by Indigenous communities for each plant species present in a simulated community. To derive these metrics, we simply summed all the unique names and identified uses for species in a given community.

Identifying and comparing hotspots

Following87, hotspots were defined as all the simulated communities landing in the upper 95% quantile in the distribution of values for a given biodiversity metric. We identified hotspots for all one hundred simulation rounds and across all biodiversity metrics (Supplementary Table 2). To compare the hotspots identified for each biodiversity metric, we computed the precision (or positive predictive value) and sensitivity (or true positive rate, or recall) of one biodiversity metric compared to another, doing this for all possible combinations of biodiversity metrics. To do this, we assigned one metric as the baseline (representing the true hotspots) and the alternative metric as the comparison. Precision measures the proportion of hotspots identified by the comparison metric that are also identified by the baseline metric. It is defined as TP/Ncomparison, with TP (the true positives) denoting the number of hotspots identified by the comparison metric that are correct and Ncomparison denoting the total number of hotspots identified by the comparison metric. If the comparison metric identifies the same hotspots as the baseline metric but also identifies many other hotspots (false positives), then the precision will be lower because Ncomparison > TP. Sensitivity measures the proportion of true hotspots identified by the comparison metric. It is defined as TP/Nbaseline, with Nbaseline denoting the total number of hotspots identified by the baseline metric. We calculated precision and sensitivity for every possible pairing of biodiversity metrics, allowing each to serve as a baseline and a comparison metric. To assess which biodiversity metrics tend to identify the same hotspots, the biodiversity metrics were clustered (with lists of identified hotspots as input) by Ward’s (1963) clustering criterion through the function hclust in the R package stats88.

Data availability

All of the data used for this simulation study are from publicly available data sources listed in the methods with full citations in the references. The data curation performed to analyze our data can be found in the clean and raw data folders (including excel sheets,.csv files, and.rds files) on GitHub: https://github.com/kydahl/biodiv-hostpots.

Code availability

The code for the analyses, as well as the clean and raw data files for running the code can be found on GitHub: https://github.com/kydahl/biodiv-hostpots.

References

Brooks, T. M. et al. Global biodiversity conservation priorities. Science 313, 58–61 (2006).

Schmitt, C. B. A tough choice: approaches towards the setting of global conservation priorities. In Biodiversity Hotspots (eds. Zachos, F. E. & Habel, J. C.) 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-20992-5_2 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011).

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. & Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858 (2000).

Marchese, C. Biodiversity hotspots: a shortcut for a more complicated concept. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 3, 297–309 (2015).

Tietje, M. et al. Global hotspots of plant phylogenetic diversity. N. Phytol. 240, 1636–1646 (2023).

Pollock, L. J., Thuiller, W. & Jetz, W. Large conservation gains possible for global biodiversity facets. Nature 546, 141–144 (2017).

Robinson, J. M. et al. Traditional ecological knowledge in restoration ecology: a call to listen deeply, to engage with, and respect Indigenous voices. Restor. Ecol. 29, e13381 (2021).

Yanou, M. P., Ros-Tonen, M., Reed, J. & Sunderland, T. Local knowledge and practices among Tonga people in Zambia and Zimbabwe: a review. Environ. Sci. Policy 142, 68–78 (2023).

Fernández-Llamazares, Á et al. No basis for claim that 80% of biodiversity is found in Indigenous territories. Nature 633, 32–35 (2024).

Carroll, S. R., Herczog, E., Hudson, M., Russell, K. & Stall, S. Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous data futures. Sci. Data 8, 108 (2021).

Cardillo, M. Phylogenetic diversity in conservation: a brief history, critical overview, and challenges to progress. Camb. Prism. Extinct.1, 1–20 (2023).

Miatta, M., Bates, A. E. & Snelgrove, P. V. R. Incorporating biological traits into conservation strategies. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 13, 421–443 (2021).

Forest, F. et al. Preserving the evolutionary potential of floras in biodiversity hotspots. Nature 445, 757–760 (2007).

Isaac, N. J. B., Turvey, S. T., Collen, B., Waterman, C. & Baillie, J. E. M. Mammals on the EDGE: conservation priorities based on threat and phylogeny. PLoS One 2, e296 (2007).

Weglarz, K. M., Saunders, W. C., Van Wagenen, A. & Pearse, W. D. Phylogenetic diversity efficiently and accurately prioritizes conservation of aquatic macroinvertebrate communities. Ecosphere 12, e03383 (2021).

de Bello, F. et al. Towards an assessment of multiple ecosystem processes and services via functional traits. Biodivers. Conserv. 19, 2873–2893 (2010).

Funk, J. L. et al. Revisiting the Holy Grail: using plant functional traits to understand ecological processes. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 92, 1156–1173 (2017).

Valencia, E. et al. Synchrony matters more than species richness in plant community stability at a global scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA117, 24345–24351 (2020).

Cadotte, M. W., Carscadden, K. & Mirotchnick, N. Beyond species: functional diversity and the maintenance of ecological processes and services: functional diversity in ecology and conservation. J. Appl. Ecol. 48, 1079–1087 (2011).

Cadotte, M. W. & Davies, T. J. Rarest of the rare: advances in combining evolutionary distinctiveness and scarcity to inform conservation at biogeographical scales: Conservation phylo-biogeography. Divers. Distrib. 16, 376–385 (2010).

Doxa, A. et al. Beyond taxonomic diversity: Revealing spatial mismatches in phylogenetic and functional diversity facets in Mediterranean tree communities in southern France. Ecol. Manag. 474, 118318 (2020).

Mazel, F., Mooers, A. O., Riva, G. V. D. & Pennell, M. W. Conserving phylogenetic diversity can be a poor strategy for conserving functional diversity. Syst. Biol. 66, 1019–1027 (2017).

Hähn, G. J. A. et al. Global decoupling of functional and phylogenetic diversity in plant communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 9, 237–248 (2024).

Salmon, E. Kincentric ecology: Indigenous perceptions of the human-nature relationship. Ecol. Appl. 10, 1327 (2000).

Gratani, M., Sutton, S. G., Butler, J. R. A., Bohensky, E. L. & Foale, S. Indigenous environmental values as human values. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2, 1185811 (2016).

Tengö, M., Brondizio, E. S., Elmqvist, T., Malmer, P. & Spierenburg, M. Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: the multiple evidence base approach. Ambio 43, 579–591 (2014).

Lefale, P. F. Ua ‘afa le Aso Stormy weather today: traditional ecological knowledge of weather and climate. The Samoa experience. Clim. Change 100, 317–335 (2010).

Velázquez-Rosas, N., Silva-Rivera, E., Ruiz-Guerra, B., Armenta-Montero, S. & González, J. Traditional Ecological Knowledge as a tool for biocultural landscape restoration in northern Veracruz, Mexico: a case study in El Tajín region. Ecol. Soc. 23, 3 (2018).

Kapoor, I. Towards participatory environmental management?. J. Environ. Manag. 63, 269–279 (2001).

Drew, J. Use of traditional ecological knowledge in marine conservation. Conserv. Biol. 19, 1286–1293 (2005).

Charnley, S., Fischer, A. P. & Jones, E. T. Integrating traditional and local ecological knowledge into forest biodiversity conservation in the Pacific Northwest. Ecol. Manag. 246, 14–28 (2007).

Worojie, T. B., Asfaw, B. T. & Mengesha, W. A. Indigenous biosystematics of yams (Dioscorea spp.) in Southwest Ethiopia: folk taxonomy, ethnolinguistic analysis, and folk descriptors. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 17, 1 (2021).

Berlin, B. Folk systematics in relation to biological classification and nomenclature. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 4, 259–271 (1973).

Sinthumule, N. I. Traditional ecological knowledge and its role in biodiversity conservation: a systematic review. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1164900 (2023).

Molnár, Z. et al. Towards richer knowledge partnerships between ecology and ethnoecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 39, 109–115 (2024).

Ens, E. J., Rossetto, M. & Costello, O. Recognising Indigenous plant-use histories for inclusive biocultural restoration. Trends Ecol. Evol. 38, 896–898 (2023).

Gorenflo, L. J., Romaine, S., Mittermeier, R. A. & Walker-Painemilla, K. Co-occurrence of linguistic and biological diversity in biodiversity hotspots and high biodiversity wilderness areas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 8032–8037 (2012).

Stepp, J. R. et al. Development of a GIS for global biocultural diversity. Policy Matters Inst. Res. Public. Policy 13, 267–270 (2004).

Wilder, B. T., O’Meara, C., Monti, L. & Nabhan, G. P. The importance of indigenous knowledge in curbing the loss of language and biodiversity. Bioscience 66, 499–509 (2016).

Jessen, T. D., Ban, N. C., Claxton, N. X. & Darimont, C. T. Contributions of Indigenous Knowledge to ecological and evolutionary understanding. Front. Ecol. Environ. 20, 93–101 (2022).

Redvers, N. et al. Indigenous natural and First Law in planetary health. Challenges 11, 29 (2020).

Wheeler, H. C. & Root-Bernstein, M. Informing decision-making with Indigenous and local knowledge and science. J. Appl. Ecol. 57, 1634–1643 (2020).

Wheeler, H. C. et al. The need for transformative changes in the use of Indigenous knowledge along with science for environmental decision-making in the Arctic. People Nat.2, 544–556 (2020).

Singer, C. L. et al. Equal use of Indigenous and scientific knowledge in species assessments: a case study from the Northwest Territories, Canada. Biol. Conserv. 281, 109995 (2023).

Devictor, V. et al. Spatial mismatch and congruence between taxonomic, phylogenetic and functional diversity: the need for integrative conservation strategies in a changing world: Spatial mismatch between diversity facets. Ecol. Lett. 13, 1030–1040 (2010).

Safi, K. et al. Understanding global patterns of mammalian functional and phylogenetic diversity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 366, 2536–2544 (2011).

Stuart-Smith, R. D. et al. Integrating abundance and functional traits reveals new global hotspots of fish diversity. Nature 501, 539–542 (2013).

Hidayati, S., Abdul Ghani, B. A., Giridharan, B., Hassan, M. Z. & Franco, F. M. Using ethnotaxonomy to assess traditional knowledge and language vitality: a case study with the vaie people of Sarawak, Malaysia. Ethnobiol. Lett. 9, 33–47 (2018).

Wehi, P. M., Whaanga, H., Roa, T. & Cox, M. P. Woven languages: understanding Indigenous socioecological systems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 39, 881–884 (2024).

Hanspach, J. et al. Biocultural approaches to sustainability: a systematic review of the scientific literature. People Nat. 2, 643–659 (2020).

Biosafety unit. Introduction. (2021).

Masood, E. More than dollars: mega-review finds 50 ways to value nature. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01930-6 (2022).

Goolmeer, T. et al. Indigenous-led designation and management of culturally significant species. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1623–1631 (2024).

Daily, G. C., Ceballos, G., Pacheco, J., Suzán, G. & Sánchez-Azofeifa, A. Countryside biogeography of neotropical mammals: Conservation opportunities in agricultural landscapes of Costa Rica. Conserv. Biol. 17, 1814–1826 (2003).

Van Cleemput, E. et al. Scaling-up ecological understanding with remote sensing and causal inference. Trends Ecol. Evol. 40, 122–135 (2024).

Kortz, A. R. & Magurran, A. E. Increases in local richness (α-diversity) following invasion are offset by biotic homogenization in a biodiversity hotspot. Biol. Lett. 15, 20190133 (2019).

Armstrong, C. G., Miller, J. E. D., McAlvay, A. C., Ritchie, P. M. & Lepofsky, D. Historical indigenous land-use explains plant functional trait diversity. Ecol. Soc. 26, 6 (2021).

Langton, M. & Rhea, Z. M. Traditional indigenous biodiversity-related knowledge. Aust. Acad. Res. Libr. 36, 45–69 (2005).

Ens, E. J. et al. Indigenous biocultural knowledge in ecosystem science and management: Review and insight from Australia. Biol. Conserv. 181, 133–149 (2015).

Copete, J. C., Kik, A., Novotny, V. & Cámara-Leret, R. The importance of Indigenous and local people for cataloging biodiversity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 38, 1112–1114 (2023).

Jackson, R. & Jain, N. Mountain Cultures, Keystone Species: Exploring the Role of Cultural Keystone Species in Central Asia. http://www.snowleopardconservancy.org/pdf/grant2019.pdf (2006).

Cordero, S., Abello, L. & Gálvez, F. Rizoma: a new comprehensive database on traditional uses of Chilean native plants. Biodivers. Data J. 10, e80002 (2022).

do Nascimento Fernandes de Souza, E. & Hawkins, J. A. Ewé: a web-based ethnobotanical database for storing and analysing data. Database (Oxford) 2020, baz144 (2020).

Ems, E. et al. Cross-Cultural Guide to Some Animals and Plants of South East Arnhem Land. (Batchelor Press Institute, 2020).

Cámara-Leret, R. & Dennehy, Z. Information gaps in indigenous and local knowledge for science-policy assessments. Nat. Sustain. 2, 736–741 (2019).

Ishtiaq, M. et al. Traditional ethnobotanical knowledge of important local plants in Sudhnoti, Azad Kashmir. Pak. Sci. Rep. 14, 22165 (2024).

Turner, N. J. Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America. (McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2014).

Moerman, D. E. BRIT—Native American Ethnobotany Database. http://naeb.brit.org/ (1998).

Chamberlain, S. A. & Szöcs, E. taxize: taxonomic search and retrieval in R. F1000 Res. 2, 191 (2013).

Chamberlain, S., Szoecs, E., Foster, Z. & Arendsee, Z. taxize: taxonomic information from around the web. R package version 0.9 (2020).

Freiberg, M. The Leipzig catalogue of vascular plants. German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig. https://doi.org/10.15468/9QXMN3 (2020).

Díaz, S. et al. The global spectrum of plant form and function: enhanced species-level trait dataset. Sci. Data 9, 755 (2022).

Kattge, J. et al. TRY plant trait database—enhanced coverage and open access. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 119–188 (2020).

Stekhoven, D. J. & Bühlmann, P. MissForest–non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 28, 112–118 (2012).

Commission for Environmental Cooperation. Ecological Regions of North America: Toward a Common Perspective. (Montreal, Quebec, 1997).

Maitner, B. S., Boyle, B., Casler, N. & Condit, R. The bien r package: A tool to access the Botanical Information and Ecology Network (BIEN) database. Methods Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12861 (2018).

Munoz, F. et al. ecolottery: Simulating and assessing community assembly with environmental filtering and neutral dynamics inR. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9, 693–703 (2018).

May, F., Gerstner, K., McGlinn, D. J., Xiao, X. & Chase, J. M. mobsim: an r package for the simulation and measurement of biodiversity across spatial scales. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9, 1401–1408 (2018).

Jin, Y. & Qian, H. V. PhyloMaker2: an updated and enlarged R package that can generate very large phylogenies for vascular plants. Plant Divers. 44, 335–339 (2022).

Smith, S. A. & Brown, J. W. Constructing a broadly inclusive seed plant phylogeny. Am. J. Bot. 105, 302–314 (2018).

Zanne, A. E. et al. Three keys to the radiation of angiosperms into freezing environments. Nature 506, 89–92 (2014).

Kembel, S. W. et al. Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 26, 1463–1464 (2010).

Helmus, M. R., Bland, T. J., Williams, C. K. & Ives, A. R. Phylogenetic measures of biodiversity. Am. Nat. 169, E68–E83 (2007).

Villéger, S., Mason, N. W. H. & Mouillot, D. New multidimensional functional diversity indices for a multifaceted framework in functional ecology. Ecology 89, 2290–2301 (2008).

Grenié, M. & Gruson, H. fundiversity: a modular R package to compute functional diversity indices. Ecography 2023, e06585 (2023).

Nowak, L. et al. Projecting consequences of global warming for the functional diversity of fleshy-fruited plants and frugivorous birds along a tropical elevational gradient. Divers. Distrib. 25, 1362–1374 (2019).

Sabatini, F. M. et al. Global patterns of vascular plant alpha diversity. Nat. Commun. 13, 4683 (2022).

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Available at https://www.R-project.org/ (2023).

Krebs, C. J. Ecology. (Pearson, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2009).

Mouillot, D., Mason, W. H. N., Dumay, O. & Wilson, J. B. Functional regularity: a neglected aspect of functional diversity. Oecologia 142, 353–359 (2005).

Laliberté, E. & Legendre, P. A distance-based framework for measuring functional diversity from multiple traits. Ecology 91, 299–305 (2010).

Rao, C. R. Diversity and dissimilarity coefficients: a unified approach. Theor. Popul. Biol. 21, 24–43 (1982).

Balick, M. J. Transforming ethnobotany for the new millennium. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 83, 58 (1996).

Faith, D. P. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol. Conserv. 61, 1–10 (1992).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Bela Loza and Abdel Holloway for their early contributions to the conceptualization of this manuscript. This work is the outcome of discussions the coauthors had at a workshop sponsored by the U.S. National Science Foundation, and we acknowledge NSF for financial support of publication costs. K.J.M.D. was supported by NSF Award #2316455, and L.R.S. was supported by NSF Award #2010702.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J.M.D.: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. EVC: conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration. SA: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. K.C.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data curation, writing- original draft, writing- review & editing. L.R.S.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion and ethics

This research did not involve empirical data collection, human participants, or biological material transfer, as it drew on publicly available data and existing knowledge frameworks, including Traditional Ecological Knowledge. While none of the authors are Indigenous to the PNW, we recognize the deep history of stewardship and knowledge held by Indigenous communities across this region. In developing this research, we took particular care to engage with and cite relevant literature that documents local and Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Yann Benetreau and Heike Langenberg. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dahlin, K.JM., Van Cleemput, E., Adhikari, S. et al. Simulated biodiversity hotspots from traditional ecological knowledge and Western metrics do not always overlap. Commun Earth Environ 6, 350 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02309-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02309-x

This article is cited by

-

Exploring the abyss through recent advances in microbial profiling technologies

Discover Oceans (2025)