Abstract

Observations show an Atlantification of the Eurasian Basin of the Arctic Ocean, with deeper penetration, shoaling, and ventilation of Atlantic waters in the eastern Arctic and an associated weakening of the cold halocline layer. These processes have a profound impact on the sea ice cover above and potentially on the transition of the Arctic to a seasonal ice cover. Here we show, using a coupled ice-ocean model, that a proper simulation of the landfast ice cover in the relatively small but deeper peripheral Kara Sea has a disproportionately large influence on the halocline stability in the Eurasian Basin and beyond. Specifically, landfast ice in the Kara Sea reduces ice growth and therefore salt rejection into the surface ocean. This negative salinity anomaly is advected eastward with a coastal current along the continental shelf in the Makarov Basin and then out of the Arctic through Fram Strait by the Transpolar Drift Stream on timescales of less than ten years. Global Climate Models, however, do not yet include landfast ice parameterizations. Therefore, they are missing this key process affecting the halocline stability, Atlantification of the Makarov Basin, and potentially the timing of a seasonally ice-free Arctic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Landfast ice (LFI)—sea ice that stays fast along the coast where it is attached to the shore or over shoals1—can extend a few kilometers (e.g., Beaufort Sea, Western Laptev Sea) to several hundred kilometers into the ocean (e.g., Kara Sea, East Siberian Sea, Eastern Laptev Sea). Its presence is associated with specific bathymetry and coastline features. For instance, it can be grounded on the ocean floor by pressure ridges in shallow water and over shoals (Stamukhi)2,3,4,5,6,7; it can be attached to coastlines by local tensile forces or compressive forces from distant land protrusion along the coast8; or it can be supported by offshore islands9. LFI plays an important role in polar coastal regions. It decreases the energy, momentum, and heat flux between the atmosphere and the ocean, and thereby reduces surface ocean mixing4,10,11,12. This extension of the land also provides a platform for hunting, tourism, scientific research, oil and gas exploration, and serves as a habitat for polar wildlife13,14,15,16.

At the seaward end of LFI, flaw-lead polynyas5 form as openings between stationary fast ice and mobile pack ice. In these flaw polynyas, large air-sea heat fluxes, sea ice growth, and associated salt rejection lead to the formation of dense waters. These cold dense waters spill over the continental shelves and find their level of neutral buoyancy between the warm salty Atlantic and the cold fresher surface water, where they form the cold halocline layer17,18. This cold halocline layer acts as a buffer between the two water masses and leads to significant sea ice growth in winter and the formation of a perennial sea ice cover. For, when ice growth and salt rejection drive surface convection, cold and saltier surface water sinks to the base of the mixed layer where it is still well above the warm water, and brings (still) cold halocline water at the freezing point into the mixed layer. This process does not lead to vertical transport of ocean heat because it does not reach the warm water, in contrast with the Southern Ocean where the thermocline coincides with the halocline19.

The recent Atlantification of the Eurasian Basin, that is, the eastward progression of warmer Atlantic Water into the eastern Arctic, has led to shoaling of the intermediate-depth Atlantic Water layer and a weakening of the halocline, increasing ocean-interior ventilation in winter20,21,22. Subsequently, the associated enhanced release of oceanic heat reduced winter sea ice formation in the Eurasian Basin23. Should the cold halocline disappear, the Atlantification of the Arctic would ventilate significant Atlantic water heat in winter leading to a seasonal sea ice cover in the Eurasian Basin24. A retreat of the cold halocline, as documented in the early 1990’s25, can affect the shelf hydrography and the formation of the cold halocline waters in the Makarov Basin26.

This work presents evidence for a significant impact of an LFI cover in the Kara Sea—a feature that is missing in current Earth System Models because of the absence of fast ice parameterizations—on the local salt budget. Without LFI, local ice formation modifies the fresh surface water provided by the large river systems to a local coastal current so that too salty water leaves the Kara Sea. This salinity anomaly signal increases the stability of the halocline over the entire Eurasian Basin.

Results

More landfast ice in the Kara Sea, fresher surface water in the interior Arctic

We activate different parameterizations of LFI, which results in the presence or absence of LFI in specific parts of the model domain (see “Methods” section). More LFI makes the shelves fresher17, but more LFI in the Kara Sea also makes the halocline in the interior Arctic (approximately the top 40 m) fresher (Fig. 1). This negative salinity anomaly in the interior Arctic Ocean reduces the salinity bias of our model relative to observations. As observational reference, we use an average of 20 salinity casts from the Unified Database for Arctic and Subarctic Hydrography (UDASH)27,28 that were collected in all Aprils of our simulation period of 2006–2015 in the region between 120°–180°E and north of 75°N (approximately the Makarov Basin). Compared to this average, the control simulation (CTRL) is too saline by 0.88. This mean difference reduces to 0.58 for the simulation with LFI. The root-mean-square difference also reduces from 1.27 to 1.06.

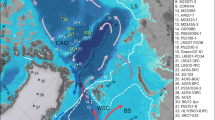

a Arctic topography. VS denotes the Vilkitsky Strait. The blue contour line denotes the (poorly) simulated fast ice extent in the control run (CTRL, without fast ice parameterization). Depth averaged (0–40 m) salinity differences for the mean April of 2006–2015: b between the simulation with all fast ice parameterizations, i.e., with a realistic LFI distribution as indicated by the blue contour line, and the CTRL simulation; c the same as (b), but with the lateral drag parameterization turned off explicitly in the Kara Sea; there is no LFI in the Kara Sea as indicated by the blue contour line; d the same as (b), but without river runoff in the Kara Sea and in CTRL; there is slightly less LFI in the Kara Sea as indicated by the blue contour line.

The simulation with the fast ice parameterization (Fig. 1b) produces higher ice concentration (less open water available for sea ice formation) along the coastlines in the Beaufort, East Siberian, Laptev, and Kara Seas, and lower ice concentration (more open water available for more sea ice formation in flaw polynyas) offshore. This is consistent with previous results17. The formation of sea ice generally leads to a local increase of surface salinity as most of the salt of seawater is left behind and not included in new sea ice. A stable LFI cover inhibits new ice formation where the continuous export of ice in the control simulation leads to continuous new ice formation and increase of salinity. Therefore, the surface water is fresher (less saline) underneath the stable LFI cover of the simulations with fast ice parameterization compared to the control simulation (Fig. 1b). This is particularly evident in the Laptev and East Siberian seas (Fig. 1b). Northward of the LFI edge in the East Siberian Sea, the upper ocean is more saline than in the control simulation, again in accord with previous results17. Offshore winds in the East Siberian Sea drive ice northwards and form polynyas at the edge of the LFI where new ice formation leaves more salt behind and increases the local surface salinity.

In the Kara Sea, an additional LFI parameterization8 also leads to an LFI cover where the water is deeper and ice keels alone fail to stabilize the LFI cover (Fig. 1b). In contrast to the local effects in and near the shallow East Siberian and Laptev Seas, LFI in the relatively deep Kara Sea leads to a much fresher upper ocean that spreads with a well-known coastal current that also carries river water along the Taymyr Peninsula and through the Vilkitsky Strait (between the Laptev and Kara Seas, Fig. 1b) into the Makarov Basin29,30. We emphasize that this low salinity anomaly in the Makarov Basin is almost entirely caused by the additional LFI in the Kara Sea. In a simulation where the new LFI parameterization8 is turned off, there is no LFI in the Kara Sea and the fresh anomaly in the Makarov Basin disappears (Fig. 1c).

As a further piece of evidence for the suggested mechanism, the amplitude of the negative salinity anomaly in the Kara Sea and the Makarov Basin decreases in an experiment where the river runoff in the Kara Sea is turned off (in both control and sensitivity experiments). Instead, a positive anomaly appears north of the New Siberian Islands (Fig. 1d). From this, we conclude that the river runoff provides a large contribution to transporting the low salinity signal in the upper ocean from the Kara Sea to the Makarov Basin (Fig. 2).

Previous results suggest that the path of the Ob and Yenisei river water29,30 coincides with the spreading of the low salinity water leading to the anomaly in Fig. 1b. To show that this is the case in our model, we trace the river runoff from the Ob and Yenisei Rivers in the Kara Sea with a passive tracer (Fig. 2). The passive tracer exits the Kara Sea through the Vilkitsky Strait. A portion enters the Laptev Sea while the remainder subducts into the Amundsen and Makarov Basins. The tracers are then advected by the Transpolar Drift Stream over the Lomonosov Ridge and finally exit through Fram Strait (Fig. 2). The distribution of passive tracer of the Ob and Yenisei water resembles observed patterns based on chemical tracer-based water mass analyses [ref. 29, their Fig. 3b]. The tracer pattern is also very similar to the pattern of the low salinity signal in the upper ocean (Fig. 1), implying a freshwater transport path from the Kara Sea to the Makarov Basin.

A Hovmöller diagram along the dashed line in Fig. 2a of the depth-averaged (0–40 m) salinity and salinity difference between different experiments illustrates the transport of the low salinity signal from the Kara Sea to the Chukchi Sea (Fig. 3). The difference between simulations with and without LFI in the Kara Sea clearly shows that salinity anomalies in the Makarov Basin originate from the Kara Sea, and that local salinity anomalies in the Laptev or East Siberian seas are not responsible for the negative salinity anomaly in the Makarov Basin.

Hovmöller diagram along the dashed line in Fig. 2a for years 2001 to 2015 (2001–2005 is a spin-up) of depth-averaged (0–40 m) (a) salinity in the control simulation (CTRL); b salinity difference between the simulation with LFI in the Kara Sea and the control simulation (corresponding to Fig. 1b); c salinity difference between the simulation without LFI in the Kara Sea and the control simulation (corresponding to Fig. 1c). The blue ellipse marks the strong negative salinity anomaly described in the text. The x-axis is the distance in kilometers along the transect (dashed line) in Fig. 2a. The dashed vertical lines parallel to the y-axis indicate the approximate locations of the Vilkitsky Strait, the Amundsen and the Makarov Basins (from left to right). The lower dashed horizontal lines mark the end of the spin-up and the upper ones the beginning of the large positive salinity anomaly in 2012.

Very early in the simulation without LFI in the Kara Sea, a positive salinity anomaly develops locally at the edge of the polynya in the Laptev and East Siberian seas (1500–2200 km, after 2001 during the spinup, Fig. 3c), because new ice formation releases salt into the ocean. This anomaly persists until the end of the simulation (see also light blue arrow in Fig. 1c). The same positive salinity anomaly in the Makarov Basin also appears early in the simulation with LFI in the Kara Sea (Fig. 3b). But here, and in contrast to the locally generated signal, low salinity of the Kara Sea is advected to the Makarov and Eurasian Basins as early as 2002. There are smaller pulses of negative salinity anomaly moving from the Kara Sea to the Makarov Basin throughout 2001–2007. This process increases in 2008, with a negative salinity anomaly peak in 2012 (blue ellipse in Fig. 3b).

Salt budget analysis

The salt content in the Arctic Ocean is determined by surface forcing, advection, and to a very small extent by diffusion between the surface and deeper ocean layer (see “Methods” section). The differences in salt content, salt advection and diffusion between the simulation with and without LFI parameterization in the Kara Sea are small when integrated over the entire model domain (O( <1%) of the signal, results not shown). In the upper 40 m of the Makarov Basin, which we chose to approximate the halocline depth in our model, the mean salt content changes very little over time in the CTRL simulation. In the cumulative budget, however, the considerable horizontal advection of salt is balanced by downward vertical advection out of the 40 m surface layer (i.e., the halocline). Vertical diffusion and surface fluxes are small (Fig. 4a).

Time series of (a) accumulated salt budget terms (\(\int_{0}^{t}\,G(t{\prime} )\,dt{\prime}\), see Eq. (1) in the “Methods” section) for the top four layers (40 m) of the Eurasian and Makarov Basin (see red area in the inset) for the CTRL simulation. The horizontal advection of salt (\({G}_{{{{\rm{adv,h}}}}}^{S}\), red line) is balanced by vertical advection (\({G}_{{{{\rm{adv,v}}}}}^{S}\), green line). b difference of simulations without and with LFI in the Kara Sea. With LFI (but not in the Kara Sea) the horizontal advection of salt is reduced, balanced by a reduction of downward advection (faint thick lines). With LFI also in the Kara Sea the downward advection decreases less than the horizontal advection, potentially because of increased stability, so that these terms no longer balance and the net salt content reduces (thin lines). c difference of accumulated salt flux relative to CTRL through the Vilkitsky Strait (in gigatons of salt, negative values mean a reduced salt flux). The flux is the combination of the flux through the actual Vilkitsky Strait and a small northward opening (see inset); red thin line: with LFI in the Kara Sea (KS); faint thick line: without LFI in the Kara Sea.

In the simulation without LFI only in the Kara Sea, but with the additional LFI in other marginal seas (Fig. 1c) and with less sea ice formation and salt release into the ocean, less salt is advected into the Makarov Basin, especially after 2012. This decrease of horizontal advection is balanced by reduced downward vertical advection of salt, leaving the mean salt practically unchanged (Fig. 4b, thick lines). The reduction of salt advected into the Makarov Basin is even larger with LFI present in the Kara Sea (after 2008 and 2012). In this case, however, it is not balanced entirely by a reduction in downward vertical advection, probably because of the surface stratification and the mean salinity increase (Fig. 4b, thin lines). The local reduction in horizontal advection between 2004 and 2008 is offset by vertical advection in this simulation supporting the notion that the magnitude of the horizontal advection anomaly is important in this balance and can lead to non-linear effects.

The salt leaves the Kara Sea mainly through the Vilkitsky Strait (Fig. 4c). In the simulation with LFI in the Kara Sea, approximately 100 gigatons of salt are not advected out of the Kara Sea through the Vilkitsky Strait (Fig. 4c), in line with the deficit of advected salt in the Makarov Basin.

Discussion

LFI affects the position of offshore polynyas and hence the location where sea ice forms over open water17. The altered freshwater flux and associated salinity forcing changes the stability of the halocline, which can be demonstrated with numerical models with adequate parameterization of LFI17. A new parameterization that allows to selectively enable LFI in the Kara Sea8 makes it possible to include its effects. The effect on the Makarov Basin hydrography is surprisingly large given the small size of the Kara Sea compared with other marginal seas (e.g., Laptev Sea, East Siberian Sea). The significant decrease in salinity within the top 40 meters of the water column (approximately the halocline in our model) in the Makarov Basin enhances the stability of the water column, while also correcting a saline model bias. Similarly, a reduction in LFI in the Kara Sea—driven, for example, by climate change—could decrease stability in the central Arctic Ocean, potentially accelerating Atlantification. This would allow warmer and more saline Atlantic waters to more easily reach the surface31,32, with profound implications for sea ice extent and seasonality.

More generally, the surface water in the Kara Sea, freshened by river water from rivers Ob and Yenisei, flows along the coast, through the Vilkitsky Strait, and into the Makarov Basin29,30. LFI along the coast causes polynyas to form off the fast ice edge and away from the core of the coastal current, so that salt rejection during sea ice formation does not modify the fresh surface water runoff. As a result, the waters exiting through the Vilkitsky Strait are relatively fresh. In a model that does not reproduce LFI along the coast of the Kara Sea, the fresh surface water is modified by salt rejection in coastal polynyas that form in winter where the LFI should be, so that the water passing through the Vilkitsky Strait is too saline. This is most likely the situation for most numerical ocean and climate models as they underestimate the fast ice extent in the Kara Sea3. As a consequence, we speculate that current ocean and climate models underestimate the stability of the Arctic halocline and potentially overestimate Atlantification.

As LFI in the Kara Sea is supported by arching of the ice33, models with non-zero tensile strength or larger maximum viscosities in the sea-ice rheology also simulate realistic LFI distributions in the Kara Sea4,33 with similar consequences for the halocline stability18. Here, we can cleanly separate the LFI effects from changes in sea ice cover due to the modified rheology18, but in general, the results are robust with respect to the specific rheological modifications used to simulate LFI in the Kara Sea.

The negative surface salinity anomaly in our simulation with LFI in the Kara Sea travels from the Kara Sea to the Makarov Basin soon after the start of the model run, but there are two larger transport anomaly episodes (2002–2006 and 2008–2015) driven by specific wind-forcing anomalies34,35. The negative salinity difference in the upper ocean is largest after the end of summer in 2012 (Fig. 3b), presumably because of the large sea ice retreat in 2012. In August 2012, an intense storm increased mixing in the ocean boundary layer, increased upward ocean heat transport, and caused bottom melt that reduced the sea ice volume about twice as fast as in other years36. Eventually, the sea ice extent at the end of the summer in 2012 was smaller than it had been since the beginning of the satellite record in the late seventies37. These processes were also at play in our simulation and the mean simulated sea ice extent reached its lowest value of the simulation in 2012 (not shown).

The Kara Sea receives freshwater discharge from the Ob and Yenisei Rivers, which carry over one-third of the total freshwater discharge in the Arctic30. This water then travels with a coastal current, leaves the Kara Sea through the Vilkitsky Strait, and eventually reaches the Makarov Basin29,30. In our simulation, a passive tracer for Ob and Yenisei water agrees with the observed Ob and Yenisei water distribution29,38 giving us faith in the accuracy of that aspect of our simulation. The simulated tracer distribution illustrates the path of the river runoff and hence any surface anomaly from the Kara Sea to the Makarov Basin via the Vilkitsky Strait (Fig. 2). In our simulations, the LFI in the Kara Sea leads to a deficit of about 100 gigatons of salt leaving the Kara Sea by the end of the simulation (Fig. 4c). This deficit in the horizontal advection is so large that it cannot be balanced by the vertical transport of salt in the Makarov Basin, because the vertical transport, mostly vertical advection, needs to overcome an increasing stability.

The Arctic mixed layer is important to physical, chemical, and biological processes. Simulating mixed layer dynamics accurately requires relatively high vertical resolution of the model grid. Our simulations are relatively coarse (10 m vertical grid spacing near the surface). Therefore, we do not expect that our simulation accurately represents the details of mixed layer dynamics. For example, we would need a dramatically refined vertical grid or even Large Eddy Simulations to study the impact of LFI on surface drivers for the change of the seasonal mixed layer depth, that is, sea ice thermodynamics (i.e., salt rejection during ice formation, freshwater input during ice melt) and wind-driven mixing39 and their effect on the mixed layer depth. Further, we note that riverine heat, which is not considered in our model, is believed to be important in explaining the phenomena of freeze-up and sea ice melt along the Arctic coasts40.

Conclusion

LFI in the Kara Sea changes the surface salinity of the central Arctic on timescales of a few years. In general, more LFI in the Arctic Ocean decreases the upper ocean salinity locally on the shelves in the Kara, Laptev, and East Siberian Seas. The largest effect, however, is found for the Kara Sea. Here, the relatively small LFI area induces a fresh anomaly in the upper ocean that is transported to the central Arctic Ocean. There, it leads to a surprisingly large salinity anomaly that increases the halocline stability. River runoff in the Kara Sea contributes to transporting the signal from the Kara Sea to the Makarov Basin. The negative salinity tendency observed with LFI on both shallow and deep shelves can be attributed mainly to reduced horizontal salt transport, which is not fully compensated by reduced vertical advective fluxes. These mechanisms become apparent after implementing a combination of a lateral and a basal drag parameterization in a pan-Arctic sea ice model to improve the simulation of LFI in the Arctic.

A sea ice model with a proper representation of LFI will improve our understanding of its influence on the hydrography in the Arctic. Our model simulations suggest that LFI in the Kara Sea stabilizes the water column in the central Arctic. Once the LFI in the Kara Sea disappears due to a warming Arctic, the stabilizing effect reduces within a few years and the Atlantification of the Arctic can accelerate.

Methods

We use a regional Arctic configuration of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology general circulation model (MITgcm)41,42 with a grid resolution of 36 km. This model resolves ocean and sea ice processes with a finite-volume discretization on an Arakawa C grid. The sea ice component includes zero-layer thermodynamics43 and viscous-plastic dynamics with an elliptical yield curve and a normal flow rule44,45. The model is forced by atmospheric fields from the global atmospheric reanalysis ERA-Interim data set46. The hydrography is initialized with temperature and salinity fields from the Polar Science Center Hydrographic Climatology 3.047. Details of the sea ice model can be found in refs. 48,49.

Without an explicit parameterization of LFI, sea ice models grossly underestimate the LFI extent. We implement two fast ice parameterizations: a basal drag parameterization3 leads to realistic LFI areas in shallow marginal seas such as the Beaufort, Laptev and the East Siberian Seas, and a new fast ice parameterization where an explicit lateral drag that depends on the sub-grid-scale coastline length and orientation replaces the no-slip boundary condition of the sea ice momentum equations8. The latter parameterization leads to more LFI in the relatively deep Kara Sea, where the basal drag parameterization that relies on relatively shallow depths fails. Thus, the new parameterization can be used as a switch to turn on or off the LFI cover in the Kara Sea and other selected regions of the Arctic Ocean8. A control simulation (CTRL) without fast ice parameterization grossly underestimates LFI extent and timing. We make use of the fast ice parameterizations so that we can compare simulations with realistic LFI in all relevant regions and simulations where the parameterizations are turned off in selected regions such as the Kara Sea to the control simulation. For each configuration, the model is run from 2001 to 2015. The first 5 years constitute a spin-up during which the sea ice and surface ocean reach stable states for analysis.

Integrating the salt conservation equation leads to a salt budget equation. The change in salt content over time (\({G}_{{{{\rm{tot}}}}}^{S}\)) in a given volume V with total surface area A and interface area with the atmosphere Asurf is equal to the convergence of the advective (\({G}_{{{{\rm{adv}}}}}^{S}\)) and diffusive fluxes Fdiff (\({G}_{{{{\rm{diff}}}}}^{S}\)), and a forcing term associated with surface salt flux Fforc (\({G}_{{{{\rm{forc}}}}}^{S}\)):

where u is the ocean velocity normal to the area A, S is the salinity (in grams per kilograms of sea water), s = ρ∭VS dx dy dz is the salt content (in grams), ρ = 1035 kg m−3 is the sea water reference density, da is the area element. For our analysis we split the advective contribution into a horizontal \({G}_{{{{\rm{adv,h}}}}}^{S}\) and a vertical part \({G}_{{{{\rm{adv,v}}}}}^{S}\). Integrating Eq. (1) gives the accumulated salt contents \(\int_{0}^{t}\,G(t^{\prime} )\,dt^{\prime}\) for each term.

Data availability

The salinity in the Unified Database for Arctic and Subarctic Hydrography (UDASH) is available from the PANGAEA data archive27.

Code availability

The model data in this manuscript is based on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology general circulation model (MITgcm)42, the version with lateral drag parameterization is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7954400 and the model configurations at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7919422.

References

World Meteorological Organization. WMO Sea-Ice Nomenclature. Terminology, Codes and Illustrated Glossary. Tech. Rep. (Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization, 1970).

Mahoney, A. R., Eicken, H., Gaylord, A. G. & Gens, R. Landfast sea ice extent in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas: the annual cycle and decadal variability. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 103, 41–56 (2014).

Lemieux, J. F. et al. A basal stress parameterization for modeling landfast ice. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 120, 3157–3173 (2015).

Lemieux, J. F. et al. Improving the simulation of landfast ice by combining tensile strength and a parameterization for grounded ridges. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 121, 7354–7368 (2016).

Rabault, J. et al. A dataset of direct observations of sea ice drift and waves in ice. Sci. Data 10, 251 (2023).

Kasper, J. L. & Weingartner, T. J. The spreading of a buoyant plume beneath a landfast ice cover. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 45, 478–494 (2015).

Plante, M., Tremblay, B., Losch, M. & Lemieux, J.-F. Landfast sea ice material properties derived from ice bridge simulations using the Maxwell elasto-brittle rheology. Cryosphere 14, 2137–2157 (2020).

Liu, Y., Losch, M., Hutter, N. & Mu, L. A new parameterization of coastal drag to simulate landfast ice in deep marginal seas in the Arctic. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 127, e2022JC018413 (2022).

Divine, D. V., Korsnes, R., Makshtas, A. P., Godtliebsen, F. & Svendsen, H. Atmospheric-driven state transfer of shore-fast ice in the northeastern Kara Sea. J. Geophys. Res. C Oceans 110, 1–13 (2005).

Johnson, M. et al. Evaluation of Arctic sea ice thickness simulated by Arctic Ocean Model Intercomparison Project models. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 117, C00D13 (2012).

Fraser, A. et al. Antarctic landfast sea ice: a review of its physics, biogeochemistry and ecology. Rev. Geophys. 61, e2022RG000770 (2023).

Cornish, S. et al. Rise and fall of sea ice production in the Arctic ocean’s ice factories. Nat. Commun. 13, 7800 (2022).

Labrousse, S. et al. Where to live? Landfast sea ice shapes emperor penguin habitat around Antarctica. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg8340 (2023).

Cooley, S. W. et al. Coldest Canadian Arctic communities face greatest reductions in shorefast sea ice. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 533–538 (2020).

Laidler, G. J. et al. Travelling and hunting in a changing Arctic: assessing inuit vulnerability to sea ice change in Igloolik, Nunavut. Clim. Change 94, 363–397 (2009).

Laidre, K. L. et al. Glacial ice supports a distinct and undocumented polar bear subpopulation persisting in late 21st-century sea-ice conditions. Science 376, 1333–1338 (2022).

Itkin, P., Losch, M. & Gerdes, R. Landfast ice affects the stability of the Arctic halocline: evidence from a numerical model. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 120, 2622–2635 (2015).

Sterlin, J. et al. Influence of the representation of landfast ice on the simulation of the Arctic sea ice and Arctic Ocean halocline. Ocean Dyn. 74, 407–437 (2024).

Martinson, D. G. & Iannuzzi, R. A. Spatial/temporal patterns in Weddell gyre characteristics and their relationship to global climate. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 108, 8083 (2003).

Beer, E., Eisenman, I., Wagner, T. J. & Fine, E. C. A possible hysteresis in the Arctic Ocean due to release of subsurface heat during sea ice retreat. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 53, 1323–1335 (2023).

Polyakov, I. V., Pnyushkov, A. V. & Carmack, E. C. Stability of the Arctic halocline: a new indicator of Arctic climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 125008 (2018).

Polyakov, I. V. et al. Atlantification advances into the Amerasian Basin of the Arctic Ocean. Sci. Adv. 11, eadq7580 (2025).

Polyakov, I. V. et al. Greater role for Atlantic inflows on sea-ice loss in the Eurasian Basin of the Arctic ocean. Science 356, 285–291 (2017).

Martinson, D. G. & Steele, M. Future of the arctic sea ice cover: implications of an Antarctic analog. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 307–310 (2001).

Steele, M. & Boyd, T. Retreat of the cold halocline layer in the Arctic ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 103, 10419–10435 (1998).

Newton, R., Schlosser, P., Martinson, D. G. & Maslowski, W. Freshwater distribution in the Arctic ocean: simulation with a high-resolution model and model-data comparison. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 113, C05024 (2008).

Behrendt, A., Sumata, H., Rabe, B. & Schauer, U. A comprehensive, quality-controlled and up-to-date data set of temperature and salinity data for the Arctic Mediterranean Sea (Version 1.0) (2017).

Behrendt, A., Sumata, H., Rabe, B. & Schauer, U. UDASH–Unified Database for Arctic and Subarctic Hydrography. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 1119–1138 (2018).

Paffrath, R., Laukert, G., Bauch, D., Rutgers van der Loeff, M. & Pahnke, K. Separating individual contributions of major Siberian rivers in the Transpolar Drift of the Arctic Ocean. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–11 (2021).

Janout, M. A. et al. Kara Sea freshwater transport through Vilkitsky Strait: variability, forcing, and further pathways toward the western Arctic Ocean from a model and observations. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 120, 4925–4944 (2015).

Asbjørnsen, H., Årthun, M., Skagseth, Ø. & Eldevik, T. Mechanisms underlying recent Arctic Atlantification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088036 (2020).

Ingvaldsen, R. B. et al. Physical manifestations and ecological implications of Arctic Atlantification. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 874–889 (2021).

Olason, E. A dynamical model of Kara Sea land-fast ice. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 121, 3141–3158 (2016).

Duan, C., Dong, S., Xie, Z. & Wang, Z. Temporal variability and trends of sea ice in the Kara Sea and their relationship with atmospheric factors. Polar Sci. 20, 136–147 (2019).

Zatsepin, A. et al. On the mechanism of wind-induced transformation of a river runoff water lens in the Kara Sea. Oceanology 57, 1–7 (2017).

Zhang, J., Lindsay, R., Schweiger, A. & Steele, M. The impact of an intense summer cyclone on 2012 Arctic sea ice retreat. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 720–726 (2013).

Parkinson, C. L. & Comiso, J. C. On the 2012 record low Arctic sea ice cover: combined impact of preconditioning and an August storm. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1356–1361 (2013).

Laukert, G. et al. Ocean circulation and freshwater pathways in the Arctic Mediterranean based on a combined Nd isotope, REE and oxygen isotope section across Fram Strait. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 202, 285–309 (2017).

Peralta-Ferriz, C. & Woodgate, R. A. Seasonal and interannual variability of pan-Arctic surface mixed layer properties from 1979 to 2012 from hydrographic data, and the dominance of stratification for multiyear mixed layer depth shoaling. Prog. Oceanogr. 134, 19–53 (2015).

Janout, M. A. et al. On the variability of stratification in the freshwater-influenced Laptev Sea region. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 543489 (2020).

Marshall, J., Adcroft, A., Hill, C., Perelman, L. & Heisey, C. A finite-volume, incompressible Navier Stokes model for studies of the ocean on parallel computers. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 102, 5753–5766 (1997).

MITgcm Group. MITgcm User Manual https://mitgcm.readthedocs.io/ (2022).

Semtner, A. J. A model for the thermodynamic growth of sea ice in numerical investigations of climate. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 6, 379–389 (1976).

Hibler, W. D. A dynamic thermodynamic sea ice model. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 9, 815–846 (1979).

Zhang, J. & Hibler, W. D. On an efficient numerical method for modeling sea ice dynamics. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 102, 8691–8702 (1997).

Dee, D. P. et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 137, 553–597 (2011).

Steele, M., Ermold, W. & Zhang, J. Modeling the formation and fate of the near-surface temperature maximum in the Canadian Basin of the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 116, 1–13 (2011).

Losch, M., Menemenlis, D., Campin, J. M., Heimbach, P. & Hill, C. On the formulation of sea-ice models. Part 1: effects of different solver implementations and parameterizations. Ocean Model. 33, 129–144 (2010).

Ungermann, M. & Losch, M. An observationally based evaluation of subgrid scale ice thickness distributions simulated in a large-scale sea ice-ocean model of the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 123, 8052–8067 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Thomas Jung and Lars Kaleschke for constructive discussions. This work is supported by the DFG-funded International Research Training Group ArcTrain (IRTG 1904 ArcTrain). We acknowledge support by the Open Access publication fund of Alfred-Wegener-Institut, Helmholtz- Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and M.L. designed the experiments, Y.L. carried them out and analyzed the data with help of M.L., L.B.T., and M.J. Y.L. wrote the manuscript with contributions from M.L., L.B.T., and M.J.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Seung-Ki Min and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Losch, M., Tremblay, L.B. et al. Landfast ice in the Kara Sea stabilizes the Arctic halocline and may slow down Atlantification of the Eurasian Basin. Commun Earth Environ 6, 423 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02360-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02360-8