Abstract

The isotopic compositions of authigenic minerals of marine sediments are potential proxies for reconstructing paleoenvironmental conditions. However, the reliability and applicability of this tracer remain elusive due to the limited spatial distribution scope and alteration during early diagenesis. Here we report isotopic measurements of seep carbonates (calcium, molybdenum, strontium, neodymium) generated by gas hydrate dissociation, sampled from a core drilled at the South China Sea. Our results show that there is approximately −1.2‰ calcium isotopic fractionation between aragonite and seawater. On the other hand, the molybdenum, strontium, and neodymium isotopic compositions are similar to those found in modern seawater. These results indicate that aragonite-dominated seep carbonate, which preferentially precipitates in proximity to the seawater-sediment interface, can preserve the pristine seawater isotopic signatures. Therefore, we infer that aragonite-dominant seep carbonate is a promising archive for coeval seawater chemistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Changes in seawater chemistry are intertwined with the evolution of the overall Earth system1,2,3. The isotopic compositions of authigenic sedimentary phases, including bioapatite, Fe–Mn oxides, and authigenic carbonate, are valuable archives for seawater compositions, and have been widely used in paleoenvironment studies4,5,6,7. However, tracking the isotopic variations of seawater through time still remains difficult due to the lack of a continuous record5. The biological factors, so-called “vital effects”, also alter some isotope systems, limiting their use as oceanic tracers8,9. In addition, the application of the geochemical paleoredox proxies can be limited by our ability to recognize records impacted by diagenesis10,11,12, as pore water often exhibits geochemical compositions distinct from seawater7,13,14. While developing a universally applicable archive for the authigenic phase from different sediments poses challenges, establishing such a framework is essential to advance the use of Ca–Mo–Sr–Nd isotopic records as robust paleoceanographic tracers.

Methane seeps are widely observed on active and passive continental margins worldwide throughout much of Earth’s history15,16,17, and are commonly associated with the dissociation of gas hydrates18,19. The sulfate-driven anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) has been shown to consume 90% or more of the methane produced in subsurface seafloor environments20. Seep carbonates, by-products of methane seepage, are formed widely close to the seafloor21,22 due to the AOM coupled with sulfate reduction23. It was suggested that seep carbonates represent excellent archives of past methane seepage and paleoenvironmental conditions16,19,24. A recent study from the South China Sea (SCS) indicated the potential for seep carbonates to preserve the (near) seawater molybdenum isotopic composition, whereas there is still an isotopic offset of ~0.5‰ from seawater25. The Ca–Mo–Sr–Nd isotopic compositions of seawater hold important information on past environmental changes and marine geochemical cycles. Aragonite, one of the authigenic carbonates in seep settings, preferentially forms near the seawater-sediment interface26,27. Their formation at or near the seafloor also reduces exposure to diagenesis in pore water, which commonly alters redox-sensitive proxies in deeper sediments26,27. Consequently, aragonite and co-precipitated authigenic minerals (e.g., sulfides) at methane seeps may serve as reliable archives for seawater chemistry. Aragonite, or formerly aragonite, is also commonly found in seep settings in geological history28,29. However, studies assessing the reliability of authigenic carbonates in seep settings as archives of coeval seawater isotopic records remain scarce.

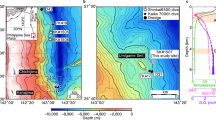

Although previous studies have progressively investigated the Mo–Ca–Sr–Nd isotopes of seep carbonates, their focus has predominantly been on the isotopic fractionation mechanisms and compositional characteristics within cold seep systems25,30. The Ca isotopes record carbonate precipitation kinetics modulated by AOM, while Mo isotopes reveal redox transitions (suboxic-anoxic-sulfidic) in cold seep environments. Radiogenic Sr and Nd isotopes effectively delineate the origins of seep fluids (e.g., seawater versus pore water) contributing to carbonate formation. The combined Ca–Mo–Sr–Nd isotopic systems synergistically constrain fluid sources, seepage flux magnitudes, and redox dynamics during carbonate precipitation, offering a multi-proxy framework to decode seep system evolution. This approach resolves ambiguities inherent to conventional proxies (e.g., δ13C, δ18O, trace elements), which often provide indirect or conflated constraints on environmental conditions. By resolving Mo–Ca–Sr–Nd isotopic behaviors and linking them to fluid and redox dynamics, which would open avenues for paleoenvironmental studies. The isotopic signatures preserved in seep carbonates, particularly their fidelity to seawater chemistry, provide a baseline for reconstructing past environmental changes and marine geochemical cycles. Here, we present the multiple (i.e., Mo, Ca, Sr and Nd) isotopic values, in combination with other geochemical data, in the different authigenic minerals of 14 layers of seep carbonate from a drill core recovered during China’s second gas hydrate drilling expedition (GMGS-2) in the SCS (Fig. 1). The present study provides new insight into the isotope systematics of seep carbonates. In addition, it provides an opportunity to evaluate whether these sediments can preserve the pristine seawater signatures.

Geological background

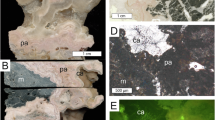

The study area (GMGS2-08 site) is located in the northeastern part of the SCS, which is one of the largest marginal seas in the West Pacific (Fig. 1). This site was drilled to a depth of ~95 meters below the seafloor (mbsf) and is dominated by clayey silt and silt, at water depths of ~800 m with high deposition rate of ∼54.2 cm/ka over the past 0.12 Ma time period19,24. Three stages of methane seepage: ∼130.3 ka BP before, MIS 5 (~130.3–111.4 ka BP), and MIS 1 (~11.1–10.0 ka BP) have been observed. Massive aragonite-dominant seep carbonates formed under intermittently euxinic conditions with enhanced methane seepage close to or at the sediment-seawater interface during stage 2. The typical textures of well-preserved, needle-like aragonite crystals (Supplementary Fig. 1), coupled with δ¹³C values (−31.6‰ to −56.8‰) and δ18O values (average: ~3.64‰) commonly found in methane-rich fluids, confirm that aragonite-dominated carbonates retain primary isotopic compositions. Stages 1 and 3 are dominated by high-magnesium calcite (HMC), low-magnesium calcite (LMC), and dolomite, which were proven to be formed deeper in the sediment column with weak seepage and a low methane flux19,24.

Results

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 show the Mo, Ca, Sr, and Nd isotope data for seep carbonate from the GMGS2-08 site. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) results are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Nearly all of the carbonate cement in stage 2 is aragonite, whereas HMC (mean = 49%, n = 25), LMC (mean = 14%, n = 25), and dolomite (mean = 14%, n = 25) dominate carbonate crusts and microcrystalline matrix samples in stages 1 and 3 (Supplementary Table 1).

In general, the Mo, Ca, Sr and Nd isotopic values are similar between stages 1 and 3, which are greatly different from those of stage 2 (Fig. 2). As shown in Supplementary Table 2, the seep carbonates exhibit a large range of δ98Mo values from 0.3 to 2.5‰ (mean = 1.8 ± 0.7, n = 28) throughout the core. The δ98Mo values of the seep carbonates range from 0.7 to 1.7 ‰ (mean = 1.1 ± 0.4 ‰, n = 4) in stage 1 and from 0.3 to 1.6 ‰ (mean = 1.0 ± 0.6 ‰, n = 7) in stage 3. In contrast, δ98Mo values in stage 2 are higher, in the range of 1.9–2.5 ‰ (mean = 2.3 ± 0.2 ‰, n = 17).

The δ44/40Ca values show a wide range, from 0.6 to 1.6 ‰ (mean = 1.0 ± 0.3 ‰, n = 27). The δ44/40Ca values are positively correlated with Mg/Ca ratios (r2 = 0.47, n = 26, p < 0.0001), but are negatively correlated with Sr/Ca ratios (r2 = 0.44, n = 26, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). The δ44/40Ca values decrease from stage 1 (mean = 1.2 ± 0.3 ‰, n = 4) to stage 2 (mean = 0.9 ± 0.1 ‰, n = 15), followed by a rebound in stage 3 (mean = 1.3 ± 0.3 ‰, n = 7).

a Relationship between δ44/40Ca and Mg/Ca ratios in three-stage seep carbonates, with the red curve indicating the trend line. The gray area represents the 95% confidence interval. b Relationship between δ44/40Ca and Sr/Ca ratios in three-stage seep carbonates, with the red curve indicating the trend line. The gray area represents the 95% confidence interval. c Relationship between 87Sr/86Sr and seawater mixing ratio in three-stage seep carbonates, with the red dashed line representing the mixing trend.

The 87Sr/86Sr ratios of carbonate samples vary between 0.709160 and 0.710336 (mean = 0.709472 ± 0.000415, n = 25). The Sr isotopic ratios are also expressed in δ notation relative to that of the modern seawater δ87Sr (‰) = [(87Sr/86Sr)sample/(87Sr/86Sr)seawater−1] × 1000, where (87Sr/86Sr)seawater is ~0.709175. Compared with carbonates in stage 2 (δ87Sr varying from -0.021 to 0.049, mean = 0.009 ± 0.024), carbonate δ87Sr in stages 1 and 3 display a larger variation range from 0.049 to 1.637, with a mean value of 0.937 ± 0.539. Carbonate samples in stage 2 display a depletion in 143Nd, with εNd values between −4.8 and −3.2 (mean = −4.0). Comparatively, the stages 1 and 3 samples exhibit lower εNd values from −8.5 to −7.6 (mean = −7.5) (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

Calcium isotopes in seep carbonates: limitations as a proxy for ancient seawater

Aragonite precipitation typically occurs under high methane flux conditions with a shallow sulfate-methane transition zone (SMTZ) near the sediment-water interface, where sulfate is abundant, which can result in carbonate-cemented seafloor crusts31. However, dolomite and Mg-calcite (up to 20 mol% Mg) forms under lower methane flux when the SMTZ is within subsurface sediments and pore water sulfate is relatively low32. Therefore, the aragonite potentially preserves the seawater isotopic composition.

The δ44/40Ca data for seep carbonates are 0.3–1.2 ‰ lower than that of modern seawater (~1.9 ‰)33. Although carbonates in stage 2 are proven to be formed near the seafloor19,24, their δ44/40Ca values are even lower relative to those of seawater (Fig. 2). Thus, there is a range of isotope fractionations during the formation of seep carbonates, with the precipitated mineral typically enriched in 40Ca relative to pore water or seawater. It is generally accepted that the Ca isotopic ratios in modern marine carbonate minerals are very different from one another. For instance, the Ca isotope fractionations between carbonate minerals and seawater can be anywhere from −1.8 to −0.8‰34,35, which depends on the mineralogy and the rate of precipitation33,36. However, investigations of Ca isotope fractionation during the formation of seep carbonate are scarce34,37,38,39, particularly in a dynamic cold seep system with different seepage intensities.

Although the magnitude of Ca isotope fractionation during the precipitation of seep carbonate is less than that of modern marine carbonates34, it is still a non-negligible fractionation37,38. Seep carbonates are an important Ca sink in the cold seep sediments39,40. Since 44Ca is depleted in the near-surface region of carbonate minerals, rapid crystal growth leads to low δ44/40Ca values in newly formed carbonate crystals41. Under thermodynamic disequilibrium conditions, Ca isotope fractionation in the growing calcite is primarily controlled by the preferential incorporation of light Ca isotopes41. Consequently, higher precipitation rates result in larger Ca isotope fractionation in the newly formed crystals41,42. Controlled calcite precipitation experiments show that δ44/40Ca decreases linearly with increasing growth rates43. In a cold seep system, AOM produces bicarbonate, raising pore water pH and driving rapid carbonate precipitation. The rapid carbonate precipitation will cause 44Ca enrichment in the pore water, because of the preferred incorporation of 40Ca into the precipitate through Rayleigh distillation37,39. The precipitation rate is a primary factor controlling Ca isotope fractionation during the formation of seep carbonate34. Aragonite forms at higher methane fluxes and precipitation rates compared to Mg-calcite38, and the higher precipitation rates of seep carbonate during stage 2 lead to more negative Ca isotopes (Fig. 2). Aragonite δ44/40Ca values diverge from seawater due to kinetic isotope effects during rapid carbonate precipitation under high methane flux. This change in precipitation rate is also supported by trace element distributions24. δ44/40Ca values are positively correlated with Mg/Ca ratios (r2 = 0.47, n = 26, p < 0.0001), but are negatively correlated with Sr/Ca ratios (r2 = 0.44, n = 26, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3), which are similar to previously published data of seep carbonates in the Barents Sea and the North Sea34,38. Therefore, the Ca isotope in seep carbonate is not likely an ideal archive for the Ca isotopic composition of ancient seawater. While this complicates direct seawater δ44/40Ca reconstruction, it provides a potential tracer for methane seepage intensity and carbonate precipitation rates.

Aragonite-dominated seep carbonates: reliable archives of seawater δ98Mo, εNd, and 87Sr/86Sr

Molybdenum is a crucial element in biology, which may be attributed to its unique chemical properties, adaptation to higher availability in more oxygenated oceans through evolution, or association with sulfide minerals or organic matter during prebiotic chemical evolution in Mo-rich environments44. Mo behaves conservatively in oxic seawater, where it is homogenously distributed due to the long residence time of about 0.44–0.78 Ma5,45,46. The anoxic sediments are major marine Mo sinks, and the Mo isotopic compositions of euxinic sediments can be used to trace paleo-ocean water Mo isotopic compositions if there is essentially complete scavenging of Mo from bottom waters with high concentration of hydrogen sulfide47,48. The modern open-ocean seawater Mo reservoir is enriched in heavy isotopes (2.3‰ ± 0.1‰, 2SD, relative to NIST3134 = 0.25‰)49.

The authigenic fraction of seepage carbonates is primarily composed of carbonate and sulfide minerals, as supported by petrographic evidence (Supplementary Fig. 1). Recent sequential extraction experiments on authigenic carbonates from cold seeps in the Gulf of Mexico and SCS reveal that pyrite fractions sequester up to 90% of the total Mo inventory and dominate the Mo budget in these sediments50. Minor fractions are associated with carbonate phases, organic matter, and Fe–Mn oxides50. The Stage 2 aragonite-dominated seep carbonates formed near the sediment-seawater interface, preventing H2S consumption during upward migration through the sedimentary column19,24. The intense methane seepage may lead to episodic or continuous euxinic conditions (dissolved H2S concentrations above 11 μΜ) where H2S was continuously formed in the bottom water during stage 2 by the AOM process19,24. Building on prior constraints, our study reveals that Mo enrichment in aragonite-dominated carbonates reflects extreme sulfidation driven by sustained methane flux. Under these conditions, Mo deposition can be accelerated by one to two orders of magnitude, leading to minor or no isotopic fractionations due to the complete removal of tetrathiomolybdate from the euxinic water25,47. This is evidenced by a positive correlation between δ98Mo and Mo contents in the study area (Fig. 4a). Meanwhile, δ98Mo also exhibit a positive correlation with the contents of aragonite (r2 = 0.64, n = 28, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4b). The average value of δ98Mo in aragonite-dominant seep carbonates (aragonite contents exceed 60%) in stage 2 is 2.3 ‰, corresponding to those of modern seawater (Fig. 4b). Consequently, elevated Mo concentrations and δ98Mo values in aragonite-dominated seep carbonates reflect intense sulfidation driven by methane flux. Under sulfidic conditions, Mo is scavenged as thiomolybdates (MoS42−), incorporated into pyrite, and co-precipitated with carbonates (Detailed information of Mo isotope analysis can be found in the MATERIALS AND METHODS). Previous studies indicated that calcium carbonates formed in open marine environments only record the Mo isotopic composition of seawater when the sulfide concentration reaches a high level between 20 and 300 μM51. Our study now documents seawater δ98Mo values for aragonite-dominant seep carbonates that formed at times of intense methane fluid flow and episodic or continuous euxinic conditions with high enough free H2S (>>11 μM) and dissolved Mo in the bottom waters24. Thus, we demonstrate the potential of seep carbonates to preserve the seawater Mo isotopic signal, providing a novel proxy for reconstructing paleo-seawater chemical compositions.

a Variations of Mo contents and δ98Mo values of three-stage seep carbonates. The δ98Mo values and Mo contents of seep sediments and carbonate nodules from ref. 25 are included for comparative analysis. The red curve indicates the variation trend. The blue bar represents the estimated δ98Mo value of seawater. The yellow curve shows the range of Mo contents and δ98Mo values in carbonate nodules. b Relationship between aragonite content and δ98Mo values in three-stage seep carbonates. The red curve indicates the trend line. The blue bar represents the estimated δ98Mo value of seawater. The gray area represents the 95% confidence interval.

In marine environments, there is a variation in Mo isotope fractionation during the removal of Mo to sediments (Fig. 5). When black shale is formed in partially limited basins with euxinic bottom waters, it is likely to record the δ98Mo signature of the global seawater47. Hydrogenous Fe–Mn oxides are also a valuable tool to trace the evolution of seawater δ98Mo52. This approach exploits a consistent isotopic offset of ~3‰ between modern Mn oxides and seawater (Fig. 5b). In addition, seawater δ98Mo can be recorded in some cases by primary carbonate precipitates and phosphorites5. However, a small Mo isotope fractionation is often observed, resulting in the wide range of δ98Mo values in black shale, Fe–Mn oxides, carbonate and phosphorites (Fig. 5b). In fact, the content of hydrogen sulfide in water column is a key factor controlling the Mo isotopic compositions of sediments in reducing marine environments53,54. Under conditions of low hydrogen sulfide content, the incomplete conversion of MoO42− to MoS42− would lead to Mo isotopic fractionation, resulting in a broad range of δ98Mo values in sediments that do not accurately reflect the Mo isotopic composition of seawater53,55. Additionally, if non-quantitative uptake occurs, the preferential incorporation of light Mo isotopes would lead to lower δ98Mo values in seep sediments53. In high-sulfide water columns, MoO42− can be rapidly and efficiently converted into MoS42−, enabling sulfide to effectively remove Mo from the water, thereby enriching Mo in the sediments while preserving the Mo isotopic composition of the surrounding water25,47.

a Histograms of δ44/40Ca, 87Sr/86Sr, and εNd values in (dolomite-, calcite-, and aragonite-dominated) seep carbonates. Orange, green, and blue bars represent δ44/40Ca, 87Sr/86Sr, and εNd values, respectively. Black dashed lines indicate seawater 87Sr/86Sr and εNd values. b Comparative δ98Mo values of different biological and marine sediment samples. The blue bar represents the estimated δ98Mo value of seawater. The isotope data are from refs. 19,24,25,30,31,34,37,38,39,75,76,77,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95.

Furthermore, recent studies have highlighted the crucial role of the Fe–Mn particulate shuttle processes in Mo burial at high methane fluxes, identifying it as the primary factor responsible for the negative δ98Mo values in seep sediments55,56. This occurs because Fe–Mn oxyhydroxides tend to absorb lighter Mo isotopes from seawater and transfer this portion of Mo to seep sediments through reductive dissolution57. Reductive dissolution of Fe–Mn particles at the sediment-water interface under anoxic and sulfidic conditions would release trace metals (e.g., Zn and Mo) into bottom water and pore water58,59. The δ98Mo values of carbonates in stages 1 and 3 are lower than that of seawater (Fig. 2), these values are similar to the previously published δ98Mo data of seep carbonates in the SCS25, which are most likely the result of the Fe–Mn particle shuttle processes. The δ98Mo values of the aragonite-dominant seep carbonates (aragonite contents exceed 60%) are independent of Mo enrichment (Fig. 4b) and the contribution of oxyhydroxide-bound Mo is minimal, suggesting that oxyhydroxide have limited influence on δ98Mo values of these carbonates. This further implies that Mo in the water column is nearly quantitatively removed to the seep carbonates. The Mo isotopic compositions (average: ~2.30‰) of aragonite-dominant seep carbonates may reflect the δ98Mo value of bottom seawater, which is consistent with the values of modern seawater (2.3‰ ± 0.1‰)49. A plausible explanation for the consistent isotopic composition between deep seawater and the aragonite-dominant seep carbonates is that the Mo contribution from Fe–Mn particle shuttling in the bottom water is minimal. Therefore, seep carbonate formed at a high level of hydrogen sulfide can effectively preserve the Mo isotopic signatures of contemporaneous seawater, and aragonite-dominant seep carbonates can serve as valuable records for reconstructing Mo isotopic variations in paleo-seawater.

Sr isotopes are considered to have a globally uniform distribution in seawater as the modern seawater residence time of Sr (~106 years) is >1000 times longer than the ocean circulation time60. Differences in Sr isotopic compositions in seep sediments are influenced by the compositions of seep fluids and the environmental conditions under which carbonate precipitation occurs61,62. The Sr isotopic signatures of seep carbonates offer valuable insights into the processes of fluid-sediment interactions in cold seep environments61,63. In methane seep areas, the seepage fluids, including methane, hydrogen sulfide, and other reducing species, mix with bottom seawater in varying proportions depending on methane seep flux, creating a dynamic geochemical environment24,64. In areas of high-intensity methane seeps, aragonite typically forms directly from seawater24,64. In such cases, the Sr isotopic compositions of the aragonite closely mirror that of seawater, with minimal fractionation (Fig. 2). However, in areas of low seep intensity, the chemical compositions of the seep fluids can modify the Sr isotopic signature of the carbonates, leading to potential deviations from typical seawater values65. This occurs in cases where carbonates, such as dolomite and calcite, form under low methane seepage intensity66, with the seep fluid contributing a greater proportion of Sr than the bottom seawater. Seep fluids are particularly enriched in radiogenic strontium isotopes and exhibit distinct isotopic signatures compared to ambient bottom seawater30. In such scenarios, the Sr isotopic compositions of precipitated calcite or dolomite reflect a mixture of Sr isotopes from the seep fluid and the underlying seawater, rather than solely from the bottom seawater, leading to an isotopic signature that diverges from the typical oceanic Sr isotopic ratios.

In studies of cold seeps, Sr isotopic compositions have been utilized to determine the sources of fluids in both modern61 and ancient30 seep environments. The contributions of seawater sources can be calculated following the methods of Viola et al.65:

where sw means seawater, and sf is seep fluid. Srsw and Srsf are Sr concentrations in seawater and seep fluid (mg/L), respectively. Sr concentration of seawater (8.10 mg/L) and seep fluid (2.179 mg/L) in the SCS were estimated by Yu et al.67. Modern seawater has a 87Sr/86Sr ratio of 0.70917530,68, and seep fluid has a 87Sr/86Sr ratio of 0.71121930. Calculated seawater fractions vary between 17% and 100% (Fig. 3c). The aragonite-dominant seep carbonates in stage 2 show a major contribution from seawater (94%–100%), whereas the HMC, LMC and dolomite in stages 1 and 3 show a mix of 6%–83% seep fluid and 17%–94% seawater. 87Sr/86Sr ratios in seep carbonates with a typical coeval seawater value were also reported from the North Sea32, the Cascadia margin63, the Gulf of Mexico62, the Gulf of Cadiz69, the mid-Atlantic Margin70, and the SCS30. In summary, the differences among cold seep carbonates highlight the critical role of seep fluid compositions and seepage intensity in determining the Sr isotopic signatures preserved in these sediments. Aragonite-dominated seep carbonates, which form in environments with intense methane seepage, are more likely to accurately record the Sr isotopic composition of the surrounding seawater.

Neodymium isotopic signatures of authigenic sedimentary phases were also widely used for reconstructing past ocean circulation patterns7,71. The use of Nd isotopes as a seawater circulation proxy is grounded in its quasi-conservative behavior in seawater and the geographically differences in εNd value based on water mass origin72. However, recent studies have shown that lithogenically sourced Nd could impact the Nd isotopic signature of the authigenic component, with the authigenic record of sediments being heavily affected by detrital components, potentially leading to the misrepresentation of bottom water εNd values6. Theoretically, aragonite precipitated under high methane seepage intensity has the potential to more faithfully preserve the Nd isotopic characteristics of seawater. In these high-flux environments, where rapid precipitation occurs in direct contact with seawater, aragonite can capture a Nd isotopic signature that closely mirrors the surrounding water mass7,73,74. Instead, dolomite and calcite that form in pore water environments are more influenced by the Nd isotopic signature of pore water from which they precipitate30,75,76,77. Neodymium isotopic signatures of pore water are typically governed by post-deposition processes (such as mineral dissolution, organic matter degradation, and adsorption/desorption reactions), leading to an Nd isotopic composition that is distinct from that of bottom seawater7,74.

The spatial distribution of seawater εNd in the northern SCS has shown that εNd of the deep-water masses of the SCS below 1500 m is homogenous (−3.5 to −4.5) and displays similar εNd values to those of the Pacific Deep Water (−3.9 to −4.4)78,79. This implies that the εNd values of the Pacific Deep Water, which enters the northern SCS through the Luzon Strait, are not modified by the local process79. This contrasts with the southern SCS, where εNd is slightly more radiogenic due to greater influence of local riverine inputs (e.g., Pearl River: −10; Mekong River: −8)79. The εNd levels in stages 1 and 3 were between −8.5 and −5.6 (mean = −7.5), which is similar to previously published εNd data of seep carbonates30,75,76,77 (Fig. 2). These results are different from those of the seawater (−3.5 to −4.5)78,79 and bulk sediments (−11.7 to −8.8)78,80 in the SCS. The precipitation of HMC, LMC, and dolomite took place within sediment pore water61, and thus εNd values of seep carbonate in stages 1 and 3 are similar to those of the Fe–Mn oxyhydroxides (−8.2 to −6.2)81 and organic matters (−6.7)82. This supports the previous suggestion that pore water εNd is controlled mainly by authigenic components, i.e., organic matter and Fe–Mn (oxyhydr) oxides7. Conversely, the average value of εNd in the aragonite-dominant seep carbonates in stage 2 is −4.1 (Supplementary Table 2), which is about the same as the value of seawater in SCS (−3.5 to −4.5)78,79. This Pacific-like signature contrasts with radiogenic pore fluids (−8 to −11) and aligns with mid-Holocene coral records (−4.2), confirming that aragonite preserves seawater εNd79. Therefore, the Nd isotopic composition of dolomite- and calcite-dominant seep carbonates formed in low methane seepage environments tends to reflect local sedimentary influences on pore water, causing their isotopic signatures to differ from bottom seawater (Fig. 2). Notably, aragonite-dominant seep carbonates can effectively record the Nd isotopic information of the bottom seawater, largely because aragonite tends to precipitate rapidly from seawater in high methane seepage environments38. The rapid precipitated of aragonite at the sediment-seawater interface limits the influence by pore waters, thus preserving the Nd isotope signature of the seawater at the time of precipitation38. These results indicate that the Nd isotopic signal in aragonite has not been blurred by diagenetic alteration, and thus can record the Nd isotopic signal of seawater. The rapid precipitation of aragonite-dominated carbonates in closed systems could preserve the original fluid signatures, while their high Sr/Ca ratios and resistance to diagenetic alteration ensure reliable isotopic records. Consequently, aragonite-dominated carbonates offer distinct advantages over traditional proxies like biogenic shells for reconstructing seawater Sr–Nd isotopes.

To date, our study now documents the values of δ98Mo, εNd, and 87Sr/86Sr for aragonite-dominant seep carbonates that formed at the SMTZ close to the seafloor, which show no fractionation relative to those of seawater. However, variations in mineralogy and precipitation rate are most likely what led to the existence of Ca isotope fractionation. Still, our study indicates the potential of seep carbonates to preserve the isotopic compositions of seawater. Further studies on other aragonite in seep carbonates are required to determine whether seep carbonates formed during periods of intense fluid flow can firmly record the isotopic composition of the coeval seawater as observed in this study.

Materials and methods

Mineralogy analysis

XRD is used for semi-quantitative carbonate mineralogy via a DXR 3000 diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) equipped with a diffracted beam graphite monochromator and using CuKα radiation at the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey (GMGS, Guangzhou, China). Scans were done from 5° to 60° (2θ) at 0.02°/s, using 40 mA current and 40 kV acceleration voltage. Rietveld analysis of the diffractograms with the program SIROQUANT was used to figure out the relative amounts of carbonate minerals. LMC represents calcite with MgCO3 less than 5 mol%, HMC stands for calcite with 5–20 mol% MgCO3, and dolomite is carbonate phases with 30–50 mol% MgCO3.

Mo isotope analysis

Analysis of Mo isotopes was performed on a multicollector inductively coupled plasma mass-spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS, Thermo-Fisher Scientific Neptune) in the State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources (GPMR), China University of Geosciences in Wuhan, using a double isotope tracer (100Mo, 97Mo) for correction of instrumental mass bias. The authigenic fractions of seep carbonates include carbonate and sulfide minerals, which (particularly pyrite) account for up to 90% of the Mo budget, rendering the influence of the detrital fraction quite limited. Consequently, for cold seep carbonates, analyzing the Mo isotopes of the carbonate fraction alone holds little significance. Therefore, in this study, we measured the Mo isotopic composition of whole-rock samples, which effectively represents the Mo isotopic composition of the authigenic components within the cold seep carbonates. Samples were digested in a mixture of HNO3, HClO4, and HF. Prior to analyses, Mo was extracted and purified by using a custom-made extraction chromatographic resin of N-benzoyl-N-phenyl hydroxylamine83. All procedures were carried out in a clean laboratory environment. Isotope ratios of Mo are expressed as δ98Mo relative to NIST SRM 3134 (δ98MoNIST3134 = 0.25‰). Reference material (GBW07316 marine sediment) was also repeatedly measured along with the samples. The δ98Mo values of NIST SRM 3134 and GBW07316 were determined to be 0.25 ± 0.05‰ (2SD, n = 18), and −0.46 ± 0.06‰ (2SD, n = 3), which is in excellent agreement with previously published values84. The results in the conventional δ-notation in (‰) are equivalent to milli Urey (mUr).

Sr and Nd isotope analysis

Sr and Nd isotopic ratios were analyzed following the method of Ge et al.30 at the GPMR, using a Finnigan Triton TIMS. Approximately 10–20 ml of the acetic acid leachate stock solution was used to rinse the carbonate components from seep carbonates. This ensures the accurate acquisition of the Sr–Nd isotopic compositions of the authigenic carbonate components in the seep carbonates, free from the influence of Sr–Nd derived from detrital sources. The samples were then purified in a clean laboratory using ion exchange columns of Dowex AG50WX12 cation resin and Eichrom Ln-Spec resin successively to separate Sr and Nd. Isotopic ratios of 143Nd/144Nd and 87Sr/86Sr were normalized to 146Nd/144Nd = 0.721900 and 88Sr/86Sr = 8.375209, respectively. Measurements of standard JNdi-1 and SRM NBS987 give average values of 0.512118 ± 0.000007 (n = 25) and 0.710254 ± 0.000008 (n = 22) for ratios of 143Nd/144Nd and 87Sr/86Sr, respectively. Nd isotopic analyses are reported in the standard epsilon notation εNd(t) = [(143Nd/144Nd)sample(t)/(143Nd/144Nd)CHUR(t)−1]104, where CHUR is the chondritic uniform reservoir with a present day 143Nd/144Nd = 0.512638.

Ca isotope analysis

The TIMS method described by Feng et al.85 was used to do the Ca isotope analyses in the GPMR with a 42Ca–48Ca double spike. In brief, sample powder was weighted into a homemade PTFE-lined steel bomb, and wetted with 0.5 ml of H2O. After the addition of 1 ml HNO3 and 1 ml HF, samples were maintained at 190 °C for 48 h for digestion. The contents were dried and redissolved with 1 ml of HNO3 twice to completely remove HF. Finally, the solution was evaporated to dryness, redissolved in 1 ml of purified HNO3 and evaporated to dryness again. Certain amounts of 42Ca–48Ca double spike were added to optimize the test precision. Then the mixture, including the sample and double spike, was purified from matrix elements prior to mass spectrometry using DGA resin (Eichrom, Bruz, France) in gravity flow micro-columns. The purified Ca was then loaded with 20% H3PO4 (Merk KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) on Re double filaments and introduced into the TIMS for mass spectrometric analysis. Referring the measured values to the international standards, NIST SRM915a as a common standard allows for the comparison of data from different laboratories. The results of the Ca isotope expressed in delta (δ) notation δ44/40Ca = [(δ44/40Ca)sample/(δ44/40Ca)std−1]103. Std refers to the NIST SRM915a, and the sample donates data corrected for instrumental fractionation. The analytical precision achieved by this procedure is 0.14‰ (2σ, at the 95% confidence level). The total Ca blank was typically less than 10 ng.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All relevant data to reproduce the manuscript findings can be found online at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15124252.

References

Canfield, D. E., Poulton, S. W. & Narbonne, G. M. Late-neoproterozoic deep-ocean oxygenation and the rise of animal life. Science 315, 92–95 (2007).

Lyons, T. W., Reinhard, C. T. & Planavsky, N. J. The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307–315 (2014).

Lu, W. Y. et al. Late inception of a resiliently oxygenated upper ocean. Science 361, 174–177 (2018).

Martin, E. E. & Scher, H. D. Preservation of seawater Sr and Nd isotopes in fossil fish teeth: bad news and good news. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 220, 25–39 (2004).

Wen, H. J. et al. Molybdenum isotopic records across the Precambrian-Cambrian boundary. Geology 39, 775–778 (2011).

Abbott, A. N., Löhr, S. C., Payne, A., Kumar, H. & Du, J. Widespread lithogenic control of marine authigenic neodymium isotope records? Implications for paleoceanographic reconstructions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 319, 318–336 (2022).

Deng, Y. N. et al. Early diagenetic control on the enrichment and fractionation of rare earth elements in deep-sea sediments. Sci. Adv. 8, abn5466 (2022).

Adkins, J. F., Boyle, E. A., Curry, W. B. & Lutringer, A. Stable isotopes in deep-sea corals and a new mechanism for “vital effects. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 1129–1143 (2003).

Rollion-Bard, C. et al. Effect of environmental conditions and skeletal ultrastructure on the Li isotopic composition of scleractinian corals. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 286, 63–70 (2009).

Fantle, M. S., Barnes, B. D. & Lau, K. V. The role of diagenesis in shaping the geochemistry of the marine carbonate record. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 48, 549–583 (2020).

Lau, K. V. & Hardisty, D. S. Modeling the impacts of diagenesis on carbonate paleoredox proxies. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 337, 123–139 (2022).

Zhao, M. Y. & Zheng, Y. F. A geochemical framework for retrieving the linked depositional and diagenetic histories of marine carbonates. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 460, 213–221 (2017).

Deng, Y. N. et al. Rare earth element geochemistry characteristics of seawater and porewater from deep sea in western Pacific. Sci. Rep. 7, 16539 (2017).

Zhao, M. Y., Zheng, Y. F. & Zhao, Y. Y. Seeking a geochemical identifier for authigenic carbonate. Nat. Commun. 7, 10885 (2016).

Boetius, A. & Wenzhöfer, F. Seafloor oxygen consumption fuelled by methane from cold seeps. Nat. Geosci. 6, 725–734 (2013).

Feng, D. et al. A carbonate-based proxy for sulfate-driven anaerobic oxidation of methane. Geology 44, 999–1002 (2016).

Peng, Y. B. et al. A transient peak in marine sulfate after the 635-Ma snowball Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2117341119 (2022).

Berndt, C. et al. Temporal constraints on hydrate-controlled methane seepage off Svalbard. Science 343, 284–287 (2014).

Deng, Y. N. et al. Possible links between methane seepages and glacial-interglacial transitions in the South China Sea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091429 (2021).

Reeburgh, W. S. Oceanic methane biogeochemistry. Chem. Rev. 107, 486–513 (2007).

Loyd, S. J. et al. Methane seep carbonates yield clumped isotope signatures out of equilibrium with formation temperatures. Nat. Commun. 7, 12274 (2016).

Michaelis, W. et al. Microbial reefs in the Black Sea fueled by anaerobic oxidation of methane. Science 297, 1013–1015 (2002).

Boetius, A. et al. A marine microbial consortium apparently mediating anaerobic oxidation of methane. Nature 407, 623–626 (2000).

Deng, Y. N. et al. Methane seepage patterns during the middle Pleistocene inferred from molybdenum enrichments of seep carbonates in the South China Sea. Ore Geol. Rev. 125, 103701 (2020).

Lin, Z. Y. et al. Molybdenum isotope composition of seep carbonates—constraints on sediment biogeochemistry in seepage environments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 307, 56–71 (2021).

Aloisi, G., Pierre, C., Rouchy, J.-M., Foucher, J.-P. & Woodside, J. Methane-related authigenic carbonates of eastern Mediterranean Sea mud volcanoes and their possible relation to gas hydrate destabilisation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 184, 321–338 (2000).

Bohrmann, G., Greinert, J., Suess, E. & Torres, M. Authigenic carbonates from the Cascadia subduction zone and their relation to gas hydrate stability. Geology 26, 647–650 (1998).

Kennedy, M., Mrofka, D. & von der Borch, C. Snowball Earth termination by destabilization of equatorial permafrost methane clathrate. Nature 453, 642–645 (2008).

Savard, M. M., Beauchamp, B. & Veizer, J. Significance of aragonite cements around Cretaceous marine methane seeps. J. Sediment Res 66, 430–438 (1996).

Ge, L. et al. Sr and Nd isotopes of cold seep carbonates from the northern South China Sea as proxies for fluid sources. Mar. Pet. Geol. 115, 104284 (2020).

Crémière, A. et al. Timescales of methane seepage on the Norwegian margin following collapse of the Scandinavian Ice Sheet. Nat. Commun. 7, 11509 (2016).

Naehr, T. H. et al. Authigenic carbonate formation at hydrocarbon seeps in continental margin sediments: a comparative study. Deep Sea Res. II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 54, 1268–1291 (2007).

Gussone, N. et al. Calcium isotope fractionation in calcite and aragonite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 4485–4494 (2005).

Blättler, C. L., Hong, W. L., Kirsimae, K., Higgins, J. A. & Lepland, A. Small calcium isotope fractionation at slow precipitation rates in methane seep authigenic carbonates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 298, 227–239 (2021).

Fantle, M. S. & Tipper, E. T. Calcium isotopes in the global biogeochemical Ca cycle: Implications for development of a Ca isotope proxy. Earth Sci. Rev. 129, 148–177 (2014).

Blättler, C. L., Henderson, G. M. & Jenkyns, H. C. Explaining the Phanerozoic Ca isotope history of seawater. Geology 40, 843–846 (2012).

Teichert, B. M. A., Gussone, N., Eisenhauer, A. & Bohrmann, G. Clathrites: archives of near-seafloor pore-fluid evolution (δ44/40Ca, δ13C, δ18O) in gas hydrate environments. Geology 33, 213–216 (2005).

Thiagarajan, N. et al. Stable and clumped isotope characterization of authigenic carbonates in methane cold seep environments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 279, 204–219 (2020).

Wang, S. H. et al. Calcium isotope fractionation and its controlling factors over authigenic carbonates in the cold seeps of the northern South China Sea. Chin. Sci. Bull. 57, 1325–1332 (2012).

Gong, S. et al. Calcium isotopic fractionation during aragonite and high-Mg calcite precipitation at methane seeps. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 622, 118419 (2023).

Tang, J., Dietzel, M., Böhm, F., Köhler, S. J. & Eisenhauer, A. Sr2+/Ca2+ and 44Ca/40Ca fractionation during inorganic calcite formation: II. Ca isotopes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 3733–3745 (2008).

Fantle, M. S. & DePaolo, D. J. Ca isotopes in carbonate sediment and pore fluid from ODP Site 807A: the Ca2+(aq)–calcite equilibrium fractionation factor and calcite recrystallization rates in Pleistocene sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 2524–2546 (2007).

Nielsen, L. C., DePaolo, D. J. & De Yoreo, J. J. Self-consistent ion-by-ion growth model for kinetic isotopic fractionation during calcite precipitation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 86, 166–181 (2012).

Anbar, A. & Knoll, A. Proterozoic ocean chemistry and evolution: a bioinorganic bridge?. Science 297, 1137–1142 (2002).

Miller, C. A., Peucker-Ehrenbrink, B., Walker, B. D. & Marcantonio, F. Re-assessing the surface cycling of molybdenum and rhenium. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 7146–7179 (2011).

Zhao, M. et al. Covariation between molybdenum and uranium isotopes in reducing marine sediments. Chem. Geol. 603, 120921 (2022).

Arnold, G. L., Anbar, A. D., Barling, J. & Lyons, T. W. Molybdenum isotope evidence for widespread anoxia in mid-proterozoic oceans. Science 304, 87–90 (2004).

Wille, M., Nägler, T. F., Lehmann, B., Schröder, S. & Kramers, J. D. Hydrogen sulphide release to surface waters at the Precambrian/Cambrian boundary. Nature 453, 767–769 (2008).

Barling, J., Arnold, G. L. & Anbar, A. D. Natural mass-dependent variations in the isotopic composition of molybdenum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 193, 447–457 (2001).

Jia, Z. et al. Seawater-fluid composition records from molybdenum isotopes of sequentially extracted phases of seep carbonate rocks. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 24, e2023GC011128 (2023).

Bura-Nakić, E., Sondi, I., Mikac, N. & Andersen, M. B. Investigating the molybdenum and uranium redox proxies in a modern shallow anoxic carbonate rich marine sediment setting of the Malo Jezero (Mljet Lakes, Adriatic Sea). Chem. Geol. 533, 119441 (2020).

Siebert, C., Nägler, T. F., von Blanckenburg, F. & Kramers, J. D. Molybdenum isotope records as a potential new proxy for paleoceanography. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 211, 159–171 (2003).

Kendall, B., Dahl, T. W. & Anbar, A. D. The stable isotope geochemistry of molybdenum. Rev. Miner. Geochem. 82, 683–732 (2017).

Neubert, N., Nägler, T. F. & Böttcher, M. E. Sulfidity controls molybdenum isotope fractionation into euxinic sediments: evidence from the modern Black Sea. Geology 36, 775–778 (2008).

Jin, M. et al. Isotope evidence for the enrichment mechanism of molybdenum in methane-seep sediments: Implications for past seepage intensity. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 373, 282–291 (2024).

Miao, X. et al. Isotopically light Mo in sediments of methane seepage controlled by the benthic Fe–Mn redox shuttle process. Glob. Planet. Change 239, 104512 (2024).

Nan, J. et al. Postdepositional behavior of molybdenum in deep sediments and implications for paleoredox reconstruction. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104706 (2023).

Eroglu, S., Scholz, F., Frank, M. & Siebert, C. Influence of particulate versus diffusive molybdenum supply mechanisms on the molybdenum isotope composition of continental margin sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 273, 51–69 (2020).

Zhang, G. et al. Copper and zinc isotopic compositions of methane-derived carbonates: Implications for paleo-methane seepage and paleoenvironmental proxies. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 136, 4005–4017 (2024).

Elderfield, H. Strontium isotope stratigraphy. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 57, 71–90 (1986).

Peckmann, J. et al. Methane-derived carbonates and authigenic pyrite from the northwestern Black Sea. Mar. Geol. 177, 129–150 (2001).

Aharon, P., Schwarcz, H. P. & Roberts, H. H. Radiometric dating of submarine hydrocarbon seeps in the Gulf of Mexico. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 109, 568–579 (1997).

Joseph, C. et al. Using the 87Sr/86Sr of modern and paleoseep carbonates from northern Cascadia to link modern fluid flow to the past. Chem. Geol. 334, 122–130 (2012).

Crémière, A. et al. Fluid source and methane-related diagenetic processes recorded in cold seep carbonates from the Alvheim channel, central North Sea. Chem. Geol. 432, 16–33 (2016).

Viola, I., Capozzi, R., Bernasconi, S. M. & Rickli, J. Carbon, oxygen and strontium isotopic constraints on fluid sources, temperatures and biogeochemical processes during the formation of seep carbonates—Secchia River site, Northern Apennines. Sediment. Geol. 357, 1–15 (2017).

Zhang, G. et al. A 209,000-year-old history of methane seepage activity controlled by multiple factors in the South China Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 151, 106200 (2023).

Yu, H. T., Ma, T., Du, Y. & Chen, L. Z. Genesis of formation water in the northern sedimentary basin of South China Sea: clues from hydrochemistry and stable isotopes (D, 18O, 37Cl and 81Br). J. Geochem. Explor. 196, 57–65 (2019).

Paytan, A., Kastner, M., Martin, E. E., Macdougall, J. D. & Herbert, T. Marine barite as a monitor of seawater strontium isotope composition. Nature 366, 445–449 (1993).

Magalhaes, V. H. et al. Formation processes of methane-derived authigenic carbonates from the Gulf of Cadiz. Sediment. Geol. 243, 155–168 (2012).

Prouty, N. G. et al. Insights into methane dynamics from analysis of authigenic carbonates and chemosynthetic mussels at newly-discovered Atlantic Margin seeps. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 449, 332–344 (2016).

Toyoda, K. & Tokonami, M. Diffusion of rare-earth elements in fish teeth from deep-sea sediments. Nature 345, 607–609 (1990).

Thomas, D. J. Reconstructing ancient deep-sea circulation patterns using the Nd isotopic composition of fossil fish debris. in Isotopic and elemental tracers of Cenozoic climate change (eds Mora, G. & Surge, D.) (Geological Society of America, 2005).

Deng, Y. et al. Possible links between methane seepages and glacial-interglacial transitions in the South China Sea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091429 (2021).

Abbott, A. N., Haley, B. A. & McManus, J. Bottoms up: sedimentary control of the deep North Pacific Ocean’s εNdsignature. Geology 43, 1035–1035 (2015).

Jakubowicz, M., Agirrezabala, L. M., Belka, Z., Siepak, M. & Dopieralska, J. Sr-Nd isotope decoupling at Cretaceous hydrocarbon seeps of the Basque-Cantabrian Basin (Spain): implications for tracing volcanic-influenced fluids in sedimented rifts. Mar. Pet. Geol. 135, 105430 (2022).

Jakubowicz, M., Kiel, S., Goedert, J. L., Dopieralska, J. & Belka, Z. Fluid expulsion system and tectonic architecture of the incipient Cascadia convergent margin as revealed by Nd, Sr and stable isotope composition of mid-Eocene methane seep carbonates. Chem. Geol. 558, 119872 (2020).

Jakubowicz, M. et al. Nd isotope composition of seep carbonates: Towards a new approach for constraining subseafloor fluid circulation at hydrocarbon seeps. Chem. Geol. 503, 40–51 (2019).

Li, X. H. et al. Geochemical and Nd isotopic variations in sediments of the South China Sea: a response to Cenozoic tectonism in SE Asia. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 211, 207–220 (2003).

Wu, Q. et al. Neodymium isotopic composition in foraminifera and authigenic phases of the South China Sea sediments: implications for the hydrology of the North Pacific Ocean over the past 25 kyr. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 16, 3883–3904 (2015).

Boulay, S., Colin, C., Trentesaux, A., Frank, N. & Liu, Z. Sediment sources and East Asian monsoon intensity over the last 450 ky. Mineralogical and geochemical investigations on South China Sea sediments. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 228, 260–277 (2005).

Huang, K. F., You, C. F., Chung, C. H., Lin, Y. H. & Liu, Z. F. Tracing the Nd isotope evolution of North Pacific Intermediate and Deep Waters through the last deglaciation from South China Sea sediments. J. Asian Earth Sci. 79, 564–573 (2014).

Freslon, N. et al. Rare earth elements and neodymium isotopes in sedimentary organic matter. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 140, 177–198 (2014).

Scholz, F., Siebert, C., Dale, A. W. & Frank, M. Intense molybdenum accumulation in sediments underneath a nitrogenous water column and implications for the reconstruction of paleo-redox conditions based on molybdenum isotopes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 213, 400–417 (2017).

Greber, N. D., Siebert, C., Nägler, T. F. & Pettke, T. δ98/95Mo values and molybdenum concentration data for NIST SRM 610, 612 and 3134: towards a common protocol for reporting Mo data. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 36, 291–300 (2012).

Feng, L. P. et al. Calcium isotopic compositions of sixteen USGS reference materials. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 41, 93–106 (2017).

Huang, H. W. et al. New constraints on the formation of hydrocarbon-derived low magnesium calcite at brine seeps in the Gulf of Mexico. Sediment. Geol. 398, 105572 (2020).

Huang, H. W. et al. Formation of authigenic low-magnesium calcite from sites SS296 and GC53 of the Gulf of Mexico. Minerals 9, 251 (2019).

Novikova, S. A. et al. A methane-derived carbonate build-up at a cold seep on the Crimean slope, north-western Black Sea. Mar. Geol. 363, 160–173 (2015).

Rongemaille, E. et al. Rare earth elements in cold seep carbonates from the Niger delta. Chem. Geol. 286, 196–206 (2011).

Tong, H. P. et al. Diagenetic alteration affecting delta δ18O, δ13C and 87Sr/86Sr signatures of carbonates: a case study on Cretaceous seep deposits from Yarlung-Zangbo Suture Zone, Tibet, China. Chem. Geol. 444, 71–82 (2016).

Wang, S. H., Yan, W., Chen, Z., Zhang, N. & Chen, H. Rare earth elements in cold seep carbonates from the southwestern Dongsha area, northern South China Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 57, 482–493 (2014).

Zhu, B., Ge, L., Yang, T., Jiang, S. Y. & Lv, X. Stable isotopes and rare earth element compositions of ancient cold seep carbonates from Enza River, northern Apennines (Italy): Implications for fluids sources and carbonate chimney growth. Mar. Pet. Geol. 109, 434–448 (2019).

Anbar, A. D. Molybdenum stable isotopes: observations, interpretations and directions. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 55, 429–454 (2004).

Luo, J. et al. Pulsed oxygenation events drove progressive oxygenation of the early Mesoproterozoic ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 559, 116754 (2021).

Chen, S. et al. Extremely light molybdenum isotope signature of sediments in the Mariana Trench. Chem. Geol. 605, 120959 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Professors Alice Drinkwater and Feifei Zhang and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments that improved this manuscript. Thanks to the crew and scientists of the vessel during the GMGS Haiyangdizhi-6 cruise. The authors deeply appreciate Dr. Yu Hu for revising this manuscript. This research was financially supported by the Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (grant no. 2023B0303000015), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 42476237, U2344222, 41803026, 41702096), and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (grant no. 2024A1515012506). No permissions were required for sampling.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yinan Deng: conceptualization, investigation, funding acquisition, data curation, data interpretation, writing—original draft, writing—reviewing & editing. Qingjun Guo: conceptualization, investigation, writing—reviewing & editing. Ganglan Zhang: visualization, writing—reviewing & editing. Fang Chen: writing—reviewing & editing. Shengxiong Yang: funding acquisition, writing—reviewing & editing. Gaowen He: writing—reviewing & editing. Hongfei Lai: writing—reviewing & editing. Daohua Chen: writing—reviewing & editing. Yunxin Fang: funding acquisition. Zenggui Kuang: funding acquisition. Jun Cao: writing—reviewing & editing. Yangtao Zhu: methodology, writing—reviewing & editing. Dawuda Usman: writing—reviewing & editing. Yufei Liu: methodology, writing—reviewing & editing. Bin Zhao: writing—reviewing & editing. Xuexiao Jiang: methodology. Mingyu Zhao: writing—reviewing & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Feifei Zhang and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, Y., Guo, Q., Zhang, G. et al. The potential of seep carbonates to preserve the seawater isotope compositions. Commun Earth Environ 6, 407 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02388-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02388-w

This article is cited by

-

Cold-Seep Carbonate Factory: Formation Mechanisms, Geochemical Proxies, and Implications for Global Carbon Cycling

Journal of Ocean University of China (2025)