Abstract

Municipalities face growing challenges in independently managing frequent and severe external shocks, often constrained by limited relief supplies and inefficient allocation strategies. Here we develop and implement hybrid coordination strategies that integrate cross-regional and multi-entity resource allocation to enhance national flood resilience across China’s eight major river basins. By incorporating cross-regional coordination among government reserves, we demonstrate that the 12-h demand coverage rate (DCR) for 1-in-100-year basin flood events can increase from 15% to 51%. Expanding to multi-entity coordination, which integrates enterprise reserves, further improves the 12-h DCR to 76%. Optimizing enterprise contractual reserve proportions can achieve complete demand coverage, even in the Yangtze and Pearl River basins with dense populations and large relief shortages. Our work provides insights into operational disaster relief coordination and informs flood management strategies for other countries facing extreme flooding challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

External shocks, such as climate change-related extreme events and global pandemics, can precipitate a swift surge in demand for relief materials, which are designed to alleviate suffering, save lives, and maintain human dignity in the affected areas1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Many countries rely on relief reserves operated by government agencies to respond to major crisis9,10,11,12. For instance, the Strategic National Stockpile, managed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, was established to deliver medication to any state within 12 h13. Similarly, China has more than 120 government-operated reserves, also mandated to meet the basic needs of affected individuals within 12 h14. However, during extreme basin floods, there may be instances where a government reserve situated in the vicinity of the disaster site is unable to meet the surge in relief needs, and distant reserves cannot arrive within a reasonable timeframe, typically 12 h15,16. Therefore, to address the deficiency of relief provision in the aftermath of a flood event, it is imperative to develop effective deployment strategies for relief resources across regions and suppliers17.

In both practice and literature, cross-regional and multi-entity coordination are considered instrumental in mitigating disaster relief shortages18,19. In the United States, the Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC), which is underpinned by state laws, enables the integration and coordination of relief resources across states without federal authorization. However, these models often rely on voluntary partnerships and decentralized operational protocols, with limited pre-disaster optimization of resource allocation. In China, cross-regional coordination is typically implemented in the form of Paired Assistance Programs (PAP), where an unaffected province provides aid to a severely affected city or county20,21. This strategy has demonstrated strong potential in addressing the scarcity of relief supplies in the hardest-hit areas, as evidenced by previous catastrophes such as Hurricane Katrina, the Wenchuan Earthquake, and the COVID-19 epidemic19,22. Multi-entity coordination can augment the government’s limited reserve capacity and facilitate a more rapid response to the needs of victims19,22. During Hurricane Harvey in 2017, the Federal Emergency Management Agency collaborated with Walmart and Johnson & Johnson to leverage their advanced storage and logistics networks to enhance the disaster response efforts. In China, the government bears the primary responsibility for disaster response and post-disaster recovery. Social participation is also notable19,21,23. For instance, during the severe flooding in Henan Province in 2021, numerous non-governmental organizations and individuals from unaffected regions spontaneously donated relief materials to support the victims in Henan24.

Despite these advances, existing research on disaster logistics coordination exhibits several limitations. Broadly, prior studies can be grouped into two strands: (1) institutional analyses that explore coordination governance frameworks20,22, and (2) optimization-based models that focus on facility location or route planning2,11,12. For example, Kapucu et al.9 emphasized legal and administrative interoperability for U.S. state-level coordination, while Li et al.19 and Chen et al.10 developed mathematical models to quantify the benefits of cooperative stockpiling. However, existing studies are often limited in scope—focusing primarily on isolated administrative levels (e.g., single cities or provinces) or single actor groups (either governmental or enterprise), with few integrating public-private collaboration and multi-level coordination within unified models at broader spatial scales (e.g., national or river-basin levels). This fragmentation hinders the systematic evaluation of coordination strategies required for large-scale disaster response. Additionally, most logistical models seldom incorporate hydrodynamic flood simulations to capture the spatiotemporal dynamics of exposure, supply reachability, and transport disruptions. As a result, they fall short of addressing the operational complexity and time-sensitive nature of large-scale flood disaster responses.

To address these gaps, this study introduces a national-scale coordination framework that integrates hydrodynamic flood simulations with multi-level, public-private resource allocation modeling to systematically optimize cross-regional and multi-entity strategies for reserving and deploying relief materials under 1-in-100-year basin flood scenarios. Unlike existing frameworks such as the United States’ EMAC, which rely primarily on voluntary partnerships and decentralized operational responses, our framework emphasizes pre-disaster strategic optimization tailored explicitly to China’s centralized institutional context. Specifically, we first modeled the flood risk across China’s eight main river basins by utilizing the CaMa-Flood model, under the assumption that these floods occur independently in each basin25,26. Subsequently, we revealed the size of China’s population exposed to major basin floods and the anticipated demand for relief materials. Next, we quantified the effectiveness and efficiency of relief supply when various cross-regional and multi-entity coordination strategies are employed. Last, we proposed a hybrid coordination strategy as the optimal solution and discussed the feasibility of translating scientific modeling into actionable policies under specific national paradigms. This work offers a robust framework to improve disaster preparedness and resilience to large-scale flooding in China and other flood-prone regions globally.

Results

Impact of cross-regional coordination

We examine three scenarios of cross-regional coordination among government reserves as follows: (1) non-coordination (NC), where relief materials are entirely supplied by government reserves in the city experiencing the flood; (2) limited coordination (LC), which allows for intra-provincial sharing, meaning that relief materials are supplied by government reserves among cities within the same province; (c) full coordination (FC), which permits inter-provincial sharing, thereby enabling the supplying of relief materials by all government reserves nationwide. It is important to note that in China, government reserves are divided into national, provincial, and municipal levels. For NC, only reserves at the municipal level can be accessed. For LC, all municipal and provincial reserves within the relevant province, as well as all national reserves, can be accessed. For FC, government reserves of any level and location can be accessed.

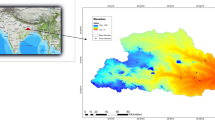

The flood exposure analysis reveals a substantial variation in the disaster relief demands among the eight basins (gray histograms in Fig. 1). The Southwest Basin has the lowest demand (about 1.5 million people), while the Yangtze River Basin has the highest (about 81.7 million people). The demand coverage rate (DCR) achieved through cross-regional coordination strategies also varies across basins. In the NC scenario, where each city relies solely on its own government reserves, the average DCR stands at 15%, with the Southwest Basin achieving the highest (27%) and the Pearl River Basin the lowest (7%). Introducing the LC strategy boosts the average DCR to 83%, but the DCR for the Yangtze and Pearl River Basins remains at 41% and 49%, respectively. The FC scenario, which enables inter-provincial sharing, shows that government reserves are sufficient to address the needs of relief materials in any basin, except for the Yangtze River Basin, where the DCR stands at 61% (Table 1).

The map presents basin locations and municipal-level demand aggregation. Circle size represents relief demand (in millions), while circle color indicates the demand range, from blue to red. Histograms aligned with the shaded background on the left y-axis illustrate the total demand per basin. Gray histograms represent basin-level total flood relief demand. Orange and red histograms on the right y-axis depict 12-h DCR with non-coordination (NC), limited coordination (LC), and full coordination (FC) strategies. Orange histograms indicate DCR with government reserves only, while red histograms show DCR with both government and enterprise reserves.

Government reserves at different levels serve distinct functions. In the NC scenario, the municipal-level reserves can offer immediate response and initial support at the onset of a flood event but are typically exhausted within 6 h, fulfilling only about one-seventh of the average demand for a single basin (purple dashed lines in Fig. 2). The implementation of the LC strategy allows for the satisfaction of relief demands in all basins except for the Yangtze and Pearl River basins, due to the support of national and provincial reserves with substantial capacity. However, this process takes a relatively long time, ~24–48 h (bule dashed lines in Fig. 2). Under FC, inter-provincial coordination enables municipal-level reserves to play a crucial role once again, facilitating the achievement of complete DCR within 24 h in most basins. The Pearl River Basin also achieved complete demand coverage within 48 h, substantially superior to that achieved under LC. However, the Yangtze River Basin continues to confront a serious shortage of relief materials (orange dashed lines in Fig. 2).

Line colors represent different cross-regional coordination strategies: purple for non-coordination (NC), blue for limited coordination (LC), and orange for full coordination (FC). Dashed lines indicate DCR using government reserves only, while solid lines show DCR utilizing both government and enterprise reserves.

Given China’s mandate for initiating basic life support within 12 h for disaster-affected populations, our analysis delves deeper into the 12-h DCR (orange histograms in Fig. 1). Results show that cross-regional coordination among government reserves can raise the average 12-h DCR from 15% to 51% (Table 1), with the Yellow River Basin achieving the highest (83%) and the Pearl River Basin the lowest (18%). Although the cross-regional collaboration strategy achieves higher demand coverage, basins with larger demands, including the Yangtze, Pearl, Huaihe, and Southeast Basin, still encounter deficits within the 12-h timeframe. Additionally, this study extends its analysis to concurrent flooding in the Yellow-Huaihe-Haihe River Basin and Yangtze-Huai River Basin, given their common occurrence27,28. When the FC strategy is employed in these two multi-basin flood scenarios, the total cumulative DCR achieves 84% and 43%, respectively, while the 24-h DCR is 58% and 36%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). These findings underscore the inadequacy of relying solely on government reserves to meet the demands posed by major flood events in an individual basin with large demand or widespread flooding in multiple basins.

Impact of multi-entity coordination

We posit that enterprises, in addition to governments, constitute the primary suppliers of relief materials. To evaluate the impact of multi-entity coordination, we initially hypothesize that enterprises can provide a quantity of relief materials comparable to those held in government reserves. Subsequently, a Pareto optimization model is employed to ascertain the optimal distribution of enterprise reserves in each city. Supplementary Table 2 indicates that, based on the NC, LC, and FC strategy, introducing equivalent enterprise reserves (i.e., enterprise reserves with quantities matching those of government reserves) can boost the average DCR across eight river basins to 28%, 96%, and 100%, respectively.

The 12-h DCR for individual river basins is illustrated by the red histograms in Fig. 1. In the NC scenario, the combination of city-level government reserves and enterprise reserves achieves an average DCR of 28%. Despite the depletion of all reserves within 6 h, the DCR doubled compared to the baseline (purple solid lines in Fig. 2). With LC, the average DCR increases to 64%, with the Huaihe River Basin leading at 92% and the Pearl River Basin at 22%. With FC, the average DCR climbs to 76%, with both the Yellow and Huaihe River Basins exceeding 90%. However, the Yangtze River Basin records DCR below 60%, and the Pearl River Basin notably at 30%. In both the LC and FC scenarios, the inclusion of enterprise reserves markedly reduces the time required to achieve complete DCR (blue and orange solid lines in Fig. 2), enabling most basins to reach 100% DCR within 36 h. However, achieving complete DCR within 12 h remains challenging, with only the Haihe River Basin accomplishing this. For multi-basin flood events, the 24-h DCR stands at only 64% for the Yangtze-Huaihe River Basin and 98% for the Yellow-Huaihe-Haihe River Basin (Supplementary Table 3). The deficiency is primarily observed in cities along the lower reaches of the Yangtze and Huaihe River, where high population densities and severe disasters amplify the demands for relief materials, leading to notable resource shortages (Supplementary Fig. 2). These findings indicate that the integration of enterprise reserves substantial enhances the government’s ability to address the shortage of relief supplies during severe floods. However, certain basins continue to face challenges in meeting requirements in a timely manner.

Therefore, we proceeded to refine the enterprise contractual reserves proportion (ECRP) in each city through a Pareto model. ECRP is defined as the proportion of enterprise supply capacity that is contractually designated for emergency use. It is calculated by dividing the enterprise’s designated emergency reserve volume by its estimated total supply capacity. The model has three objectives: (1) maximizing the 12-h DCR for individual basin floods; (2) maximizing the 24-h DCR for multi-basin floods; and (3) minimizing the overall increase in ECRP for economic considerations. Besides, this optimization process considers the reserve potential of each city (Supplementary Fig. 3). The model generates two solutions: the first suggests a substantial ECRP increase in a few cities (referred to as local optimization, as displayed in Fig. 3), whereas the second advocates for a modest enhancement of ECRP in a wide range of cities (referred to as global optimization, as displayed in Fig. 3c).

Maps (a–c) display the distribution of ECRP across cities under no optimization, local optimization, and global optimization, respectively, as indicated by gray, green, and yellow colors in (d, e). d The average 12-h DCR across eight individual basin flood scenarios and the average 24-h DCR in two multi-basin flood scenarios (Y-H for Yangtze-Huaihe River Basin and Y-H-H for Yellow-Huaihe-Haihe River Basin). e The time required for each city within a specific basin to reach a 100% DCR. For instance, in the Yangtze River Basin, under global optimization, nearly all cities attain a 100% DCR within 12 h, while 75% of cities reach this target under local optimization, in comparison to only 50% achieving the same under no optimization. In (e), box plots show the median as the center line, the 25th and 75th percentiles as the lower and upper box edges, and the range within 1.5 times the interquartile range as the whiskers.

Optimizing ECRP effectively addresses the shortage of relief materials in China’s southern region within tight timeframes, boosting the 12-h DCR in the Pearl, Yangtze, Southeast, and Yangtze-Huaihe River Basin notably. With local optimization, the cities in Guangdong province experience the most substantial ECRP uplift. This enhancement substantially benefits the Pearl River Basin and supports flood relief efforts in the Yangtze and Huaihe Basins (Fig. 4). The global optimization strategy enhances the ECRP in most cities, thereby ensuring sufficient local supply and reducing the costs of transporting resources between cities. This shift alters the dynamics of inter-city coordination and enables the fulfillment of complete DCR in all basins within the 12-h constraint (yellow color in Fig. 3d, e).

a, d, g, j The cumulative DCR for two individual basins and two multi-basin regions. Gray, green, and yellow lines represent the cumulative DCR under no optimization, local optimization, and global optimization, respectively. The second column (b, e, h, k) and the third column (c, f, i, l) display the spatial deployment of relief materials under local and global optimization, respectively. Red and green bubbles represent the quantities of supplies exported and imported, respectively. Gradient red lines depict the volume of inter-city transportation. Blue gradient color bar indicates the shortage rate of DCR (i.e., 1−DCR) within these timeframes, with darker tones denoting a lower fulfillment level.

Figure 4 displays the cumulative DCR and relief material flow for two individual basins with the highest demand (Pearl and Yangtze River Basin) and two multi-basin regions. The first column illustrates that the global optimization strategy enables the Yangtze, Pearl, and Yellow-Huaihe-Haihe River Basins to achieve 100% DCR within 12 h, whereas the local optimization prolongs the time to 18 h. Despite the considerable challenge posed by concurrent flooding in the Yangtze-Huai River Basin, both optimization strategies successfully ensured that demand coverage reached near-completion within 24 h. The second and third columns indicate that, after ECRP optimization, the deployment of relief materials in the Yangtze and Yangtze-Huaihe River Basin promotes a pattern of “Paired Assistance,” whereby distant, unaffected cities provide relief to impacted regions. In contrast, the Pearl and Yellow-Huaihe-Haihe River Basin fosters a “Mutual Aid” pattern between adjacent cities within urban clusters.

Discussion

We systematically evaluated various coordination strategies, including cross-regional coordination among government reserves and multi-entity coordination involving both government and enterprise reserves, to devise a hybrid coordination strategy for enhancing relief efforts during severe basin floods. Our findings demonstrate that implementing full cross-regional and multi-entity coordination with the optimization of ECRP across most cities can increase the 12-h DCR of relief materials from 15% to over 80% (Figs. 1 and 3). While China has practical experiences such as “Paired Assistance” authorized by the central government and “Mutual Aid” promoted by regional integration policies, the challenge remains in strengthening governance mechanisms to facilitate relief coordination, notably in tailoring spatially varying policies and coordination plans for river basins with diverse needs, alongside reinforcing the role of social participation.

The analyses suggest the establishment of a hybrid coordination framework that integrates full cross-regional and multi-entity coordination, with performance-based optimization of enterprise reserves, to enhance disaster response capacity across diverse flood scenarios. Upon revealing the benefits of coordination, another question arises: How is collaboration facilitated? This is important for determining the feasibility of translating scientific modeling into actionable policies. The classic theory of collaborative governance suggests that initial conditions, facilitative leadership, institutional design, and collaborative process are four fundamental elements for successful collaboration29. While China lacks administrative regulations akin to the EMAC, the central government-endorsed PAP demonstrates robust execution capabilities, coordinating nationwide support during major crises30. Recent urban agglomeration and regional integration policies further foster inter-city coordination for achieving cohesive development and responding to extreme events31. These are important institutionalizing mechanisms to facilitate coordination in response to severe floods in China. Moreover, the spatial heterogeneity of coordination needs revealed by our results suggests that a uniform national strategy may not be appropriate. Tailored approaches should be adopted in accordance with regional governance structures and exposure patterns. For example, in the Yangtze and Huaihe river basins, systems that can promote the adoption of PAP are recommended. Conversely, in the Pearl, Yellow, and Haihe river basins, it is more urgent and effective to strengthen coordination between neighboring cities within urban agglomerations.

The second issue is the enhancement of enterprise reserves. The expansion of ECRP in a multitude of urban areas, particularly those situated in the eastern region, can effectively enhance the DCR in the Pearl, Yangtze, Huaihe, and Haihe river basins. However, it is essential to recognize that enterprise contractual reserves are distinct from social donations. It acts as a form of government procurement, where excessive reserves could financially strain local governments. While expanding enterprise reserves is an effective means of addressing relief material shortages, it might not be a sustainable economic solution for all municipalities. Thus, scaling up contractual reserves must be balanced against economic sustainability, particularly in resource-constrained regions. Another viable approach is to increase the engagement of social organizations and individuals, whose contributions can further complement the efforts of government and enterprise reserves32.

To evaluate the robustness of our findings against uncertainties in flood frequency estimation, we conducted sensitivity analyses using alternative flood distributions33. Specifically, in addition to the baseline Gumbel distribution, we simulated 100-year flood scenarios using the Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) and Weibull distributions, subsequently recalculating relief demand and corresponding DCR values. The results indicated that alternative distribution assumptions altered basin-level relief demand estimates by ±8% on average, and led to variations in 12-h DCRs of approximately ±7% (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). These deviations remain within an acceptable range for operational planning, indicating that the core demand estimates are relatively stable across commonly used statistical models. Importantly, the relative effectiveness of coordination strategies remained consistent across all tested distributions. The hybrid approach (government plus enterprise reserves) consistently outperformed the government-only strategy, under both limited and full collaboration conditions. This consistency underscores the methodological and operational robustness of adopting hybrid, cross-entity coordination strategies despite inherent uncertainties in flood frequency modeling.

The proposed coordination framework is designed to be modular and adaptable. It integrates flood exposure modeling, demand estimation, and multi-entity resource allocation, all of which can be customized for different spatial scales, administrative contexts, or disaster types. With minor adjustments, this framework could support coordination planning not only at the national level but also within provinces, between urban agglomerations, or even across borders for international humanitarian logistics.

This research has some limitations. Firstly, this study uses historical 1-in-100-year flood scenarios to evaluate coordination strategies, without incorporating the projected intensification of extreme events under climate change. In addition, the model assumes statistical independence of flood events across river basins, which may underestimate the risk of compound flooding caused by typhoons or large-scale climate extremes. Furthermore, the reservoir operation module in CaMa-Flood was not activated, as part of a modeling simplification. While this assumption allows for consistent comparison across basins and focuses on worst-case exposure scenarios, it may overestimate inundation extents, particularly in areas with large reservoir storage capacity. Future research could incorporate dynamic flood projections under climate scenarios, copula-based joint flood modeling, and reservoir regulation modules to enhance the applicability and robustness of coordination strategies under increasingly complex and uncertain conditions34,35,36,37,38. It should also be noted that although we assessed the uncertainty arising from the choice of flood distribution (e.g., Gumbel, GEV, Weibull), other sources of model uncertainty remain unquantified. These include errors in hydrological input data, uncertainties in flood extent mapping, and simplifications regarding transport network performance. Future work could adopt Monte Carlo simulation, scenario-based perturbation analysis, or robust optimization frameworks to systematically incorporate these sources of uncertainty and improve the model’s adaptability39,40,41. Moreover, the current model considers only flood-induced road inaccessibility and does not account for the potential contribution of multimodal transport systems such as railways and air routes. In reality, during certain flood scenarios, trunk railway lines and major airports may remain partially operable and provide critical redundancy for cross-regional emergency supply distribution. Future extensions could incorporate dynamic mode-switching and capacity-aware multimodal routing, thereby improving the operational realism and feasibility of emergency logistics planning42,43. Finally, the demand estimation in this study is based on population exposure and does not yet account for differences in vulnerability or infrastructure resilience. Incorporating socioeconomic indicators—such as the proportion of elderly population, access to healthcare, or income levels—would support a more equitable and targeted distribution of emergency resources, particularly for vulnerable populations44,45.

Methods

Flood modeling

Bias-corrected runoff outputs from the Variable Infiltration Capacity (VIC) hydrological model were used to drive the CaMa-Flood model for simulating basin-scale flood dynamics. These outputs, corrected using the Global Streamflow Characteristics dataset, provide daily runoff data at a spatial resolution of 3 arcmin and have demonstrated strong performance in replicating flow regimes and extreme events46,47,48. The dataset covers the period from 1979 to 2019. CaMa-Flood v4.0.4, a global river hydrodynamics model, was employed to simulate daily river discharge, storage, water levels, and inundation depth at a spatial resolution of 0.1° 49,50,51. The historical annual maximum river storage data were analyzed using the Gumbel probability distribution function to calculate the river storage values for a 100-year return period at each grid point26,52. Subsequently, the water storage maps were downscaled through overlapping with a high-resolution digital elevation model at a 15-arcsecond resolution (~450 m at the equator), facilitating the creation of inundation maps49,53,54. For details on model validation, refer to the Supplementary Method 1.

Estimating relief demand and supply during flood events

We estimated the relief demands during 1-in-100-year flood events based on the number of people requiring emergency evacuation55. This metric, widely used by the Chinese government, serves as a quantitative standard for evaluating local emergency reserve levels and can be sourced from government documents or inferred from the size of local emergency material reserves. By using the number of people requiring emergency evacuation and resettlement to estimate resource needs during floods, we effectively integrate national guidelines with scenario simulation outcomes. Specifically, we overlap flood inundation data from CaMa-Flood simulations with population distribution grids to estimate the relief demands in each city during floods, focusing on populations residing in areas with water depths exceeding 0.3 m, aggregated at the city level (Supplementary Method 2). Population data, derived from the Popworld dataset and refined using China’s seventh census data at the city level, ensure city-specific population totals align with census records.

In China, the government reserves span the national, provincial, city, county, and township levels. The volume of government reserves is determined based on official documentation such as the Emergency Plan for Natural Disaster Relief, the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan for Food Circulation and Material Reserve Development, the Emergency Material Support Fourteenth Five-Year Plan, and the Emergency System Construction Fourteenth Five-Year Plan. These documents specify the severity of disasters that should trigger various levels of disaster relief material deployment, by considering local disaster risk, economic conditions, and population size. The prescribed number of individuals needing evacuation and resettlement serves as a proxy for determining the government reserves’ capacity. For a detailed methodology on estimating government reserves, please refer to Supplementary Method 3.

We hypothesize that for any given city, all medium and large-scale supermarkets that provide essential daily goods constitute the foundation for its enterprise reserves. In this framework, it is assumed that the volume of enterprise reserves comprises a fixed quantity of physical stockpiles, equivalent to those of government reserves, and an adjustable quantity of contractual stockpiles. Contractual reserves are calculated by multiplying the ECRP by the regular production capacity of each enterprise. For a comprehensive methodology on these estimations and the influence of flood conditions on the availability of enterprise resources, refer to Supplementary Method 4.

Modeling transportation disruptions under flood conditions

A network-based analytical framework is adopted to simulate post-disaster relief logistics under realistic flood conditions, incorporating flood-induced changes in travel costs. The transportation network is constructed using OpenStreetMap data, integrating hierarchical attributes such as road type, speed limits, and connectivity rules. Each road segment is assigned a baseline travel speed, which is then adjusted to reflect accessibility disruption caused by flooding. We define a road segment as disrupted if the inundation depth exceeds 0.3 m, a threshold commonly adopted in road closure protocols56. Affected segments are reassigned to a waterborne transport mode with a fixed travel speed of 20 km/h, simulating the use of emergency boats or amphibious vehicles. This adjustment ensures that the cost surface embedded in the network accurately represents reduced mobility within inundated zones. We construct an origin–destination (O–D) matrix to represent the minimum travel time between all supply nodes and demand cities affected by flooding. The O–D matrix captures both intra-regional (within-city) and inter-regional (between-city) delivery costs. The adjusted travel time matrix is then integrated into a linear programming formulation that optimizes relief material allocation and minimizes total delivery time under capacity and accessibility constraints. Detailed implementation steps and parameter configurations are provided in Supplementary Method 5.

Modeling distribution of relief materials under collaboration scenarios

In this study, we established an optimization model based on linear programming to improve the allocation of relief materials during flood disasters, aiming to minimize transportation time costs and maximize material fulfillment rates18,57,58,59. The model explores three collaborative scenarios to examine the efficiency of resource allocation strategies at various administrative levels. For each city, we simulate the cumulative allocation of relief materials over time and compute the DCR at multiple time intervals (e.g., 6, 12, 18, and 24 h). The minimum time required to reach a given level of DCR (e.g., 100%) is recorded as the city’s response time. This time-based DCR evaluation is used to assess the effectiveness of coordination strategies under flood scenarios.

Scenario 1, non-coordination (NC): relying solely on city-level reserves

Scenario 1 assumes that each affected city relies solely on its own city-level reserves to meet demand, without involving inter-city coordination. In this scenario, the amount of relief materials allocated from city d’s city-level reserves, \({X}_{dd}^{{{{\rm{city}}}}}\), is calculated as follows:

where \({X}_{dd}^{{{{\rm{city}}}}}\) represents the quantity of materials allocated from city d from its own city-level reserves, \({S}_{d}^{{{{\rm{city}}}}}\) denotes the city-level storage capacity of city d, and \({D}_{d}\) indicates the demand in city d.

Based on this, the material fulfillment rate \({R}^{(1)}\) can be calculated as follows:

where \({R}^{(1)}\) denotes the fulfillment rate when relying solely on city-level reserves, and D is the set of all demand cities.

Scenario 2, limited coordination (LC): provincial collaboration + national reserves

When city-level reserves are insufficient, we introduce Scenario 2, which incorporates provincial collaboration and national central reserves. In this scenario, relief materials are allocated sequentially, starting from city-level reserves, followed by provincial-level reserves within the same administrative region, and finally, if needed, from the national central reserves. Specifically, if the demand of a city d cannot be fully met by its city-level reserves, additional support is provided from provincial reserves, calculated as follows:

where \({X}_{pd}^{{{{\rm{prov}}}}}\) represents the quantity of materials allocated from provincial reserves to demand city d, \({S}_{p}^{{{{\rm{prov}}}}}\) is the provincial storage capacity, and \({D}_{d}-{X}_{dd}^{{{{\rm{city}}}}}\) represents the remaining demand in city d after using its city-level reserves.

If provincial reserves are still insufficient, national central reserves are used, calculated as:

where \({X}_{nd}^{{{{\rm{central}}}}}\) is the quantity allocated from national central reserves, and \({S}_{n}^{{{{\rm{central}}}}}\) denotes the national central storage capacity.

In Scenario 2, the material fulfillment rate\({R}^{(2)}\) is calculated as follows:

where \({R}^{(2)}\) represents the fulfillment rate under provincial collaboration and national central reserves, and P denotes the set of all provincial supply cities.

Scenario 3, full coordination (FC): nationwide cross-provincial collaboration

If Scenario 2’s reserves are still insufficient, Scenario 3 is applied, introducing nationwide cross-provincial collaboration. Under this scenario, if provincial and central reserves are inadequate, reserves from other provinces are allocated to meet the demand, calculated as:

where \({X}_{id}^{{{{\rm{inter}}}}-{{{\rm{prov}}}}}\) represents the quantity allocated from other provincial reserves i to demand city d, and \({S}_{i}^{{{{\rm{prov}}}}}\) is the storage capacity of the supplying city in another province.

In Scenario 3, the material fulfillment rate \({R}^{(3)}\) is calculated as follows:

where \({R}^{(3)}\) denotes the fulfillment rate under nationwide cross-provincial collaboration, and N represents the set of all supply cities nationwide.

Efficiency analysis

To assess the efficiency improvement of different collaborative scenarios, we define the following gain indicators: the efficiency gains from Scenario 1 to Scenario 2, \(\Delta {R}^{(2,1)}\), is calculated as:

and the efficiency gain from Scenario 2 to Scenario 3, \(\Delta {R}^{(3,2)}\), is calculated as:

These efficiency gain indicators help evaluate the effectiveness of cross-regional collaboration in actual emergency rescue operations and quantify the material allocation efficiency under different scenarios.

For detailed methodology for estimating delivery costs, refer to Supplementary Method 5. The executable code used for implementing this optimization model can be found in the custom code.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

VIC-Bias-Corrected runoff data are accessible at https://www.reachhydro.org/home/records/grfr. GSW data can be sourced from https://global-surface-water.appspot.com/. River flow data are courtesy of the Yangtze River Water Conservancy Committee, Ministry of Water Resources of China. Data from China’s seventh census can be obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics. Population data at a resolution of 1 km can be accessed at https://hub.worldpop.org/geodata/summary?id=34879. The road network dataset can be obtained from the OpenStreetMap dataset (https://www.openstreetmap.org). Government reserves data are compiled from various sources, including the State Council of China, the Food and Material Reserve Department, the Emergency Management Department, and local governments. Enterprise reserves data are estimated through POI data, which can be collected from Baidu Maps. While quality checks have been conducted on data pertaining to government and enterprise reserves to ensure accuracy, inconsistencies might arise due to varied data origins. Data created in this study are openly available, which can be found in the Figshare repository60.

Code availability

The source code of the CaMa-flood model, executable scripts, global river maps, and regionalization tools for the CaMa-flood model can be found at http://hydro.iis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/~yamadai/cama-flood/. The code used to produce the numbers, tables, and figures is available from the associated code repository60.

References

Altay, N. & Green, W. G. OR/MS research in disaster operations management. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 175, 475–493 (2006).

Shahverdi, B., Tariverdi, M. & Miller-Hooks, E. Assessing hospital system resilience to disaster events involving physical damage and Demand Surge. Socio Econ. Plan. Sci. 70, 100729 (2020).

Ye, Y., Jiao, W. & Yan, H. Managing relief inventories responding to natural disasters: gaps between practice and literature. Prod. Oper. Manag. 29, 807–832 (2020).

Raymond, C. et al. Understanding and managing connected extreme events. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 611–621 (2020).

Garrido, R. A., Lamas, P. & Pino, F. J. A stochastic programming approach for floods emergency logistics. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 75, 18–31 (2015).

Ceferino, L., Mitrani-Reiser, J., Kiremidjian, A., Deierlein, G. & Bambarén, C. Effective plans for hospital system response to earthquake emergencies. Nat. Commun. 11, 4325 (2020).

Shu, J., Lv, W. & Na, Q. Humanitarian relief supply network design: expander graph based approach and a case study of 2013 Flood in Northeast China. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 146, 102178 (2021).

Devi, S. Pakistan floods: impact on food security and health systems. Lancet 400, 799–800 (2022).

Kapucu, N., Augustin, M. E. & Garayev, V. Interstate partnerships in emergency management: emergency management assistance compact in response to catastrophic disasters. Public Adm. Rev. 69, 297–313 (2009).

Chen, Y., Zhao, Q., Wang, L. & Dessouky, M. The regional cooperation-based warehouse location problem for relief supplies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 102, 259–267 (2016).

Wang, Q. & Nie, X. A stochastic programming model for emergency supply planning considering transportation network mitigation and traffic congestion. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 79, 101119 (2022).

Yin, J. et al. Strategic storm flood evacuation planning for large coastal cities enables more effective transfer of elderly populations. Nat. Water 2, 274–284(2024).

CHEMM. Strategic National Stockpile [cited 2023 Sept 18]. Available from: https://chemm.hhs.gov/sns.htm.

Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. The Ministry of Civil Affairs and nine other departments jointly issued the Guiding Opinions on Strengthening the Construction of Natural Disaster Relief Materials Reserve System. [cited 2023 Sept 15]. Available from: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2015-09/10/content_2928409.htm (2015).

Lu, Y. & Xu, J. The progress of emergency response and rescue in China: a comparative analysis of Wenchuan and Lushan earthquakes. Nat. Hazards 74, 421–444 (2014).

Zhang, L. et al. Emergency medical rescue efforts after a major earthquake: lessons from the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Lancet 379, 853–861 (2012).

Mukhopadhyay, A. et al. A review of incident prediction, resource allocation, and dispatch models for emergency management. Accid. Anal. Prev. 165, 106501 (2022).

Chang, M., Tseng, Y. & Chen, J. A scenario planning approach for the flood emergency logistics preparation problem under uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 43, 737–754 (2007).

Li, X., Ramshani, M. & Huang, Y. Cooperative maximal covering models for humanitarian relief chain management. Comput. Ind. Eng. 119, 301–308 (2018).

Hu, Q., Zhang, H., Kapucu, N. & Chen, W. Hybrid coordination for coping with the medical surge from the COVID‐19 pandemic: paired assistance programs in China. Public Adm. Rev. 80, 895–901 (2020).

State Council of the People’s Republic of China. National Emergency Management System Plan during the 14th Five-Year Plan Period. [cited 2023 Sept 10]. Available from: https://www.mem.gov.cn/zl/202208/P020220823583813558584.pdf (2022).

Cheng, Y. D., Yu, J., Shen, Y. & Huang, B. Coproducing responses to COVID‐19 with community‐based organizations: lessons from Zhejiang Province, China. Public Adm. Rev. 80, 866–873 (2020).

Rodríguez-Espíndola, O., Albores, P. & Brewster, C. Disaster preparedness in humanitarian logistics: a collaborative approach for resource management in floods. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 264, 978–993 (2018).

Lu, Y., Zhang, Z. & Gan, Y. Joint disaster relief: the Chinese civilian rescue teams’ response to the 2021 Henan flood. Nat. Hazards. 120, 1755–1783 (2024).

Wang, W., Yang, S., Stanley, H. E. & Gao, J. Local floods induce large-scale abrupt failures of road networks. Nat. Commun. 10, 2114 (2019).

Kimura, Y., Hirabayashi, Y., Kita, Y., Zhou, X. & Yamazaki, D. Methodology for constructing a flood-hazard map for a future climate. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 27, 1627–1644 (2023).

Wang, H., Sun, J., Fu, S. & Zhang, Y. Typical circulation patterns and associated mechanisms for persistent heavy rainfall events over Yangtze-Huaihe River Valley during 1981–2020. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 38, 2167–2182 (2021).

Ren, J. et al. Evolution and prediction of drought-flood abrupt alternation events in Huang-Huai-Hai River Basin. China. Sci. Total Environ. 869, 161707 (2023).

Ansell, C. & Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theory. 18, 543–571 (2008).

Bai, X. Build networked resilience across cities. Science 383, eado5304 (2024).

Jiang, N. & Jiang, W. How does regional integration policy affect urban resilience? Evidence from urban agglomeration in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 104, 107298 (2024).

Guo, J., Bian, Y., Li, M. & Du, J. Assessing resilience through social networks: a case study of flood disaster management in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 108, 104583 (2024).

Jiang, R. et al. Substantial increase in future fluvial flood risk projected in China’s major urban agglomerations. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 389 (2023).

Xu, H. et al. Combining statistical and hydrodynamic models to assess compound flood hazards from rainfall and storm surge: a case study of Shanghai. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 3919–3930 (2024).

Hanazaki, R., Yamazaki, D. & Yoshimura, K. Development of a reservoir flood control scheme for global flood models. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 14, e2021MS002944 (2022).

Boulange, J., Hanasaki, N., Yamazaki, D. & Pokhrel, Y. Role of dams in reducing global flood exposure under climate change. Nat. Commun. 12, 417 (2021).

Eilander, D. et al. A globally applicable framework for compound flood hazard modeling. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 823–846 (2023).

Wang, N. et al. Flood fatalities and displacement influence human migration in floodplains of developing countries. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 319 (2025).

Alipour, S. M., Engeland, K. & Leal, J. Uncertainty analysis of 100-year flood maps under climate change scenarios. J. Hydrol. 628, 130502 (2024).

Muñoz, D. F., Moftakhari, H. & Moradkhani, H. Quantifying cascading uncertainty in compound flood modeling with linked process-based and machine learning models. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 2531–2553 (2024).

Aitken, G., Beevers, L. & Christie, M. A. Multi‐Level Monte Carlo models for flood inundation uncertainty quantification. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2022WR032599 (2022).

Ma, W., Lin, S., Ci, Y. & Li, R. Resilience evaluation and improvement of post-disaster multimodal transportation networks. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 189, 104243 (2024).

Liu, Z., Chen, H., Liu, E. & Zhang, Q. Evaluating the dynamic resilience of the multi-mode public transit network for sustainable transport. J. Clean. Prod. 348, 131350 (2022).

Lee, H., Hong, W. & Lee, Y. Experimental study on the influence of water depth on the evacuation speed of elderly people in flood conditions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 39, 101198 (2019).

Ermagun, A., Smith, V. & Janatabadi, F. High urban flood risk and no shelter access disproportionally impacts vulnerable communities in the USA. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 2–8 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Global reach-level 3-hourly river flood reanalysis (1980–2019). Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc. 102, E2086–E2105 (2021).

Liang, X., Wood, E. F. & Lettenmaier, D. P. Surface soil moisture parameterization of the VIC-2L model: evaluation and modification. Glob. Planet. Change 13, 195–206 (1996).

Beck, H. E., de Roo, A. & van Dijk, A. I. J. M. Global maps of streamflow characteristics based on observations from several thousand catchments*. J. Hydrometeorol. 16, 1478–1501 (2015).

Yamazaki, D., Kanae, S., Kim, H. & Oki, T. A physically based description of floodplain inundation dynamics in a global river routing model. Water Resour. Res. 47, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009726 (2011).

Yamazaki, D., de Almeida, G. A. M. & Bates, P. D. Improving computational efficiency in global river models by implementing the local inertial flow equation and a vector-based river network map. Water Resour. Res. 49, 7221–7235 (2013).

Yamazaki, D., Sato, T., Kanae, S., Hirabayashi, Y. & Bates, P. D. Regional flood dynamics in a bifurcating mega delta simulated in a global river model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3127–3135 (2014).

Hirabayashi, Y., Tanoue, M., Sasaki, O., Zhou, X. & Yamazaki, D. Global exposure to flooding from the new CMIP6 climate model projections. Sci. Rep. 11, 3740 (2021).

Yamazaki, D. et al. Analysis of the water level dynamics simulated by a global river model: a case study in the Amazon River. Water Resour. Res. 48, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012WR011869 (2012).

Yamazaki, D. et al. MERIT Hydro: a high‐resolution global hydrography map based on latest topography dataset. Water Resour. Res. 55, 5053–5073 (2019).

Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Standard for the construction of Disaster Relief Materials Reserve. [cited 2023 June 15]. Available from: https://www.mca.gov.cn/zt/history/checkUp/mzzt/201605/20160527092338124.doc (2009).

Lu, C. Robust weighted vertex p-center model considering uncertain data: an application to emergency management. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 230, 113–121 (2013).

Yu, D. et al. Disruption of emergency response to vulnerable populations during floods. Nat. Sustain. 3, 728–736 (2020).

D'Aeth, J. C. et al. Optimal national prioritization policies for hospital care during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Nat. Comput. Sci. 1, 521–531 (2021).

Tzeng, G., Cheng, H. & Huang, T. D. Multi-objective optimal planning for designing relief delivery systems. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 43, 673–686 (2007).

Yao, Q. Data and code for cross-regional and multi-entity resource coordination in flood relief planning across China’s river basins. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27641547 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the editors and reviewers for their constructive suggestions. This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation in China (Grant No. 42371088 and 42471082), the “Shu Guang” project supported by Shanghai Municipal Education Commission and Shanghai Education Development Foundation (Grant No. 21SG28).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. and M.L. conceived, conceptualized, and supervised the study. Q.Y. completed the framework of methodology. Q.Y. and M.L. conducted data analysis and performed the visualization of the results. Q.Y., M.L. and J.W. discussed and interpreted the results. M.L. and Q.Y. wrote the first manuscript. M.P.K. and J.Y. helped interpret the results. All authors edited and approved the manuscript and contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Masoud Zaerpour and Sudarshana Mukhopadhyay for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Rahim Barzegar and Martina Greceqyet. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, Q., Wang, J., Li, M. et al. Cross-regional and multi-entity resource coordination can enhance the supply of disaster relief materials during flood events in China. Commun Earth Environ 6, 472 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02461-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02461-4

This article is cited by

-

Assessing and Optimizing Urban Dynamic Resilience to Extreme Rainfall from Shock to Recovery

International Journal of Disaster Risk Science (2026)

-

A Stochastic Mixed Integer Linear Programming Model for Cross-Regional Supply Network Optimisation Under Dynamic Flow Constraints

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2025)