Abstract

Over the past few decades, a reduction in chlorinated long-lived ozone-depleting substance emissions due to the regulations imposed by the Montreal Protocol has led to a global decrease in stratospheric chlorine. At the same time, emissions of chlorinated Very Short-Lived Substances, which are unregulated, have increased. Here we show that observed changes of inorganic stratospheric chlorine are inconsistent with changes in the tropospheric abundances of long-lived ozone-depleting substances. Satellite observations of stratospheric chlorine species from the Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment—Fourier Transform Spectrometer during 2004–2020 reveal that the observed decrease in inorganic stratospheric chlorine is 25%–30% smaller than expected based on trends of long-lived ozone-depleting substances alone. At mid-latitudes in the lower stratosphere, this can be explained by the chlorinated Very Short-Lived Substances increase, which offsets the long-term reduction of stratospheric chlorine by up to 30%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The stratospheric ozone layer protects life on Earth by absorbing harmful solar ultraviolet (UV) radiation. The discovery of ozone (O3) destruction by halogen-containing Ozone-Depleting Substances (ODSs), such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), in the 1980s was thus of major concern [e.g. refs. 1,2]. The 1987 Montreal Protocol and its subsequent amendments and adjustments successfully reduced anthropogenic emissions of long-lived ODSs3, leading to 21st century increases in stratospheric O3 concentrations in the middle and upper stratosphere [e.g. refs. 4,5,6]. However, O3 depletion can also be caused by Very Short-Lived Substances (VSLSs), which are not regulated by the Montreal protocol [e.g. refs. 7,8]. VSLSs are trace gases that have lifetimes of less than 6 months and less uniform tropospheric concentrations compared to longer-lived species such as CFCs3. Brominated and iodinated VSLSs have mostly natural sources, such as algae, seaweed, and phytoplankton [e.g. refs. 9,10,11], but the most important chlorinated VSLSs (Cl-VSLSs, such as dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), chloroform (CHCl3) and 1,2-dichloroethane (C2H4Cl2)) are mainly emitted by anthropogenic activities [e.g. refs. 12,13]. The contribution of Cl-VSLSs to the total inorganic stratospheric chlorine (Cly) is small, but growing, as emissions of chlorinated long-lived ODSs decrease and emissions of Cl-VSLSs increase14,15. The global mean total tropospheric Cl-VSLS abundance increased from 103 ppt in 2016 to about 113 ppt in 2020, a rate of 2.5 ppt/year3. This can impact the rate of O3 recovery, potentially delaying it to a later date than projected by models that neglect VSLSs16,17.

Previous studies have calculated the Cl-VSLS trend in the upper troposphere/lower stratosphere (UTLS) using a Chemical Transport Model (CTM)14,18 or a Chemistry-Climate Model (CCM)19 constrained by observed surface abundances of Cl-VSLSs. Using a CTM resulted in a Cl-VSLS trend at the tropical tropopause of 3.8 ± 0.3 ppt/year for 2004–201714, and using a CCM resulted in similar Cl-VSLS trend of 3.7 ± 0.5 for the same period19. Cl-VSLS measurements in the UTLS are available from aircraft campaigns [e.g. refs. 20,21], and there is reasonable agreement between modelled and observed Cl-VSLS concentrations near 17 km in the tropics between 2004 and 201614. At higher altitudes in the stratosphere it is only possible to measure the chlorinated product gases, such as HCl (also formed from long-lived ODSs), and not the Cl-VSLSs themselves, which are no longer present in detectable amounts at these altitudes. Modelled stratospheric HCl trends were shown to agree better with HCl trends in observations from the Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment—Fourier Transform Spectrometer (ACE-FTS)22 when Cl-VSLSs were included in the simulations14,19, but the specific impact of Cl-VSLSs on stratospheric Cly trends was not quantified.

Here we use ACE-FTS observations of HCl and ClONO2 to determine the stratospheric Cly trend at mid-latitudes for 2004–2020. The observed Cly trend is derived by scaling the ACE-FTS HCl+ClONO2 trend by the modelled ratio of the Cly trend to the HCl+ClONO2 trend. The resulting ACE-FTS Cly trends are shown to be inconsistent with the trend in the chlorine component of the Equivalent Effective Stratospheric Chlorine (Cl-EESC)23, which is used as a proxy for the trend in chlorinated long-lived ODSs. The stratospheric Cly trends are 25% − 30% smaller than expected based only on decreases in long-lived ODSs. Cl-VSLS can explain most of this difference. In particular, for younger air, the combined Cl-VSLS+Cl-EESC trend is equivalent to the observed stratospheric Cly trend in both hemispheres.

Results

Trends in chlorinated long-lived ODSs

We use the trend in the chlorine component of EESC to represent the trend in long-lived chlorinated ODSs. EESC is a metric for the combined effects of long-lived chlorinated and brominated ODSs on the stratosphere, based on abundances of the tropospheric source gases23,24,25. EESC is derived by propagating tropospheric ODS abundances into the stratosphere according the age spectrum described by a Green’s function for air with a given mean age23. Typically 3 and 5.5 years are used for the mean ages, chosen to roughly correspond to the lower stratosphere at mid-latitudes and polar latitudes, respectively25. The age spectra are further modified to account for chemical loss, in addition to transport. Details of the EESC calculation are provided in ref. 23. We use the same method here to calculate the chlorine contribution to the total EESC: the Cl-EESC. The tropospheric abundances of ODS used in the Cl-EESC calculation are from the WMO 2022 Ozone Assessment3, based primarily on measurements from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) [e.g. ref. 26] and the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE) [e.g. ref. 27].

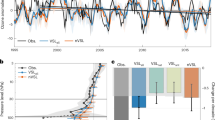

Figure 1 shows the resulting Cl-EESC from 1980 to 2020 for 3- and 5.5-year-old air. Since ~2000, the Cl-EESC mixing ratio has decreased at a steady rate due to the phase-out of long-lived ODSs, so the trend in the Cl-EESC can be approximated using a simple linear regression. The trend is calculated for 2004–2020: the start year is limited by the ACE-FTS record, and the end year is limited by the availability of ODS abundance measurements that are needed for the Cl-EESC calculation. The dashed black lines in Fig. 1 show the resulting fit for 3- and 5.5-year-old air. The corresponding trends for 2004–2020 are −9.24 ± 0.65 ppt/year for 3-year-old air and −18.66 ± 0.82 ppt/year for 5-year-old air.

Trends in inorganic stratospheric chlorine

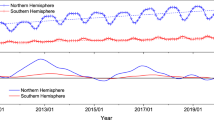

For our initial assessment, we use the sum of ACE-FTS HCl observations and ClONO2 observations to represent the stratospheric inorganic chlorine reservoir. Trends in stratospheric trace gas concentrations are typically calculated using a multiple linear regression (MLR) model that includes proxies for phenomena that are known to contribute to the observed variability, such as the solar cycle and the quasi-biennial oscillation (QBO). By applying this standard MLR to monthly zonal mean (MZM) ACE-FTS observations of HCl+ClONO2 we find a distinct hemispheric asymmetry in the trends for 2004–2020: below 30 km the inorganic stratospheric chlorine decreased in the SH by up to 20 ppt/year and increased by an insignificant amount in the NH (Fig. 2A). This pattern was observed previously in HCl trends16,28,29,30 and it was attributed to a slowdown of the Brewer-Dobson circulation (BDC) in the NH relative to the SH28. We would expect to see HCl decrease in both hemispheres if the trend was only due to surface emissions of chlorine-containing substances. The HCl+ClONO2 trends are therefore caused by the combined effect of transport and emission changes. Using the sum of HCl and ClONO2 also ensures that the trends are not significantly impacted by the 2020 Australian wildfires, which occurred near the end of the time period used for the trend calculation. The associated anomalies in both gases following the wildfires compensate for each other: HCl decreased and ClONO2 increased31.

Trends are for 2004-2 to 2020-12. The magenta boxes mark the approximate regions of 3- and 5.5-year-old air at mid-latitudes (35°–55° in each hemisphere; older air is at higher altitudes for a fixed latitude). The height of each box is 3 km, corresponding to the vertical resolution of the AoA observations. A Trends calculated with a standard MLR. B Trends calculated with the N2O MLR, which uses N2O as a proxy for dynamical variability. Hatching denotes statistically insignificant trends at the 2σ level.

To determine the trend solely due to changes in chlorine-containing substance emissions, it is necessary to account for BDC changes in the regression. This can be done using N2O observations as a proxy for dynamical variability32: N2O is a long-lived trace gas with a tropospheric source and a known surface trend, so it provides a good representation of transport anomalies throughout the stratosphere. Later work further demonstrated that using ACE-FTS N2O observations as a proxy for dynamical variability could explain nearly all of the inter-hemispheric asymmetry in ACE-FTS HCl trends over 2004–201830. Fig. 2B shows the trend in ACE-FTS HCl+ClONO2 from this version of the regression, which we call the N2O MLR (see data and methods section for details). Both hemispheres have a significant negative HCl+ClONO2 trend, which suggests that hemispherically asymmetric changes in the BDC were properly controlled for in this version of the trend calculation.

To compare the ACE-FTS HCl+ClONO2 trends to the Cl-EESC trends, it is necessary to have the HCl+ClONO2 trends for air of the same mean ages (3 and 5.5 years). The ACE-FTS MZM age of air profiles33 are used to determine the mean altitude of each age in four 10° latitude bins centred at 50°S, 40°S, 40°N, and 50°N, which we refer to as mid-latitudes. The focus is on mid-latitudes as the fraction of the source gases that has been converted to Cly in the tropics is low, and the polar vortex regions are highly variable. Mid-latitudinal Cly trends are also a more representative measure of stratospheric chlorine trends than tropical Cly trends since many more transport pathways are integrated into mid-latitude air masses.

The ACE-FTS HCl and ClONO2 are interpolated to the mean altitudes of 3- and 5.5-year-old air at mid-latitudes (19.0 km and 29.5 km, respectively), and the trends are then calculated with the N2O MLR. The resulting HCl+ClONO2 trends are nearly equivalent at all four latitudes for 5.5-year-old air (Fig. 3). There are some small differences between the trends at each latitude for 3-year-old air, with the values varying from −7.63 ± 1.82 ppt/year to −5.34 ± 1.39 ppt/year. This suggests that while the N2O MLR can significantly reduce inter-hemispheric differences in the HCl+ClONO2 caused by BDC changes compared to the standard MLR, there are still some small differences that the method does not account for at lower altitudes.

The mean HCl+ClONO2 trends in each hemisphere are used as estimates of the overall mid-latitude NH and SH chlorine trends for 3- and 5.5-year-old air. The resulting NH HCl+ClONO2 trend is −6.97 ± 1.72 ppt/year for 3-year-old air and −13.04 ± 1.80 ppt/year for 5.5-year-old air. The SH HCl+ClONO2 trend is −6.42 ± 1.59 ppt/year for 3-year-old air and −13.03 ± 1.88 ppt/year for 5.5-year-old air. The absolute HCl+ClONO2 decrease is greater for older air because the total HCl+ClONO2 abundance is larger: in older air, there has been more time for chlorinated source gases to be converted to stratospheric inorganic chlorine reservoirs. This can be seen in Supplementary Fig. 1: the mean HCl+ClONO2 trend is −0.4%/year for both 3- and 5.5-year-old air.

To assess how well the HCl+ClONO2 trend captures the total Cly trend, we use results from the Canadian Middle Atmosphere Model (CMAM)34,35. Fig. 4A shows the trend in CMAM HCl+ClONO2, and Fig. 4B shows the trend in CMAM Cly. The trends in the two cases are very similar below ~25 km, but the Cly decrease is greater than the HCl+ClONO2 decrease at higher altitudes. The ratio of the Cly trend to the HCl+ClONO2 trend is given in Fig. 4C: the ratio is close to 1 at lower altitudes, and reaches up to ~1.15 at 35 km. This shows that the HCl+ClONO2 trend can fully explain the Cly trend at lower altitudes, but is missing part of the Cly trend at higher altitudes, in particular contributions from ClO. It should also be noted that the inconsistency between the HCl+ClONO2 trend from CMAM in Fig. 4 and from ACE-FTS in Fig. 2 is not important, as we are only using the model results to get the relationship between HCl+ClONO2 and Cly, not the actual trend values, and this relationship largely depends on the model chemistry.

A Trends in HCl+ClONO2. B Trends in Cly. C The ratio of the trends, Cly/(HCl+ClONO2). The magenta boxes mark the approximate regions corresponding to 3- and 5.5-year-old air at mid-latitudes. The height of each box is 3 km, corresponding to the vertical resolution of the AoA observations. Trends are calculated with the N2O MLR.

The ACE-FTS HCl+ClONO2 trends are converted to Cly trends using a scale factor from CMAM. At mid-latitudes, the Cly/HCl+ClONO2 trend ratio is 1.02 for 3-year-old air and 1.05 for 5.5-year-old air. Multiplying the ACE-FTS HCl+ClONO2 trends by this ratio gives an ACE-FTS Cly trend in the NH of −6.53 ± 1.59 ppt/year for 3-year-old air and −13.97 ± 1.93 ppt/year for 5.5-year-old air during 2004–2020. The corresponding Cly trends in the SH are −6.59 ± 1.63 ppt/year for 3-year-old air and −13.50 ± 1.95 ppt/year for 5.5-year-old air.

To test the ability of CMAM to accurately represent the ratio of Cly to HCl+ClONO2 trends, we also considered scale factors from six other models using runs that follow the same REFD1 scenario as the CMAM runs. Five of the models have realistic Cly amounts and partitioning and can be compared to CMAM. Scaling factors from all of these models are very similar, which suggests that CMAM provides an accurate representation of the chlorine partitioning in these regions. Further discussion and the scaling factors for each model are provided in the Supplementary Information document.

Discussion and conclusion

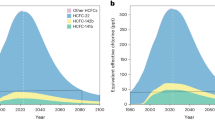

The recovery of the stratospheric ozone layer depends upon a reduction in anthropogenically emitted halocarbons. While atmospheric abundance of long-lived chlorinated ODSs have indeed decreased over the past two decades due to regulations imposed by the Montreal Protocol, stratospheric concentrations of Cly have not gone down at a similar rate: if long-lived chlorinated ODSs were the only source of stratospheric chlorine, we would expect the trend in the inorganic stratospheric chlorine reservoir to be the same. However, we find that the observed decrease in Cly is 25–30% smaller than the Cl-EESC trend (Fig. 5). This difference cannot be explained by the uncertainties in the Cl-EESC and Cly trend calculations.

To see if the discrepancy between long-lived ODS trends and total stratospheric chlorine trends can be explained by rising emissions in unregulated Cl-VSLSs, we also compare the Cly trends to the combined trend in Cl-EESC+Cl-VSLS. The Cl-VSLS trends that we use are 3.0 ± 0.5 ppt/year for 3-year-old air and 2.4 ± 0.5 ppt/year for 5.5-year-old air. The Cl-VSLS trends are from simulations done with the Met Office’s Unified Model coupled to the United Kingdom Chemistry and Aerosol (UM-UKCA)36, which are constrained to observed surface values of Cl-VSLS19. The combined Cl-EESC+Cl-VSLS trend agrees with the stratospheric Cly trend for 3-year-old air in both hemispheres, showing the Cl-VSLSs have a significant impact on stratospheric chlorine in the lower stratosphere: Cl-VSLSs offset the decrease in stratospheric chlorine loading by ~30% in this region (Fig. 5). For 5.5-year-old air the agreement is less strong, but the combined Cl-EESC+Cl-VSLS trend is nonetheless more similar to the total stratospheric Cly trend than the Cl-EESC trend is on its own, particularly in the NH.

The fact that our Cly trend estimates based on stratospheric satellite measurements are consistent with the Cl-EESC + Cl-VSLS trend estimates based on modelling combined with ground-based observations provides convincing evidence that stratospheric chlorine trends can only be explained if all sources of chlorine are taken into account. It should be noted that the presented uncertainties are based on the trend-calculation method and describe unexplained variations of the quantities over time. Other sources of uncertainty, such as the potential impact of satellite sampling patterns on zonal mean stratospheric chlorine estimates, are not taken into account, but could bias the trends37,38. Furthermore, transport variations that would impact N2O differently than HCl or ClONO2 will not be removed from the chlorine trends by our N2O proxy method. However, the very good agreement between the Cly trends in the NH and the SH in Fig. 3 suggests that our trend-calculation method successfully removes the dominant first-order effects of the well-known hemispheric asymmetries of the circulation changes. Finally, Cl-VSLS trend estimates can be impacted by uncertainties in the observed circulation and its trends, alongside its representation in the different reanalysis products and models19, and uncertainties in the spatial distribution of VSLS emissions13,39 and their interactions with the atmospheric transport pathways that may not be adequately represented by using latitudinally uniform lower boundary conditions

Overall, our results show that rising Cl-VSLS levels in the stratosphere have a significant impact on the total inorganic stratospheric chlorine concentrations. Cl-VSLS increases are causing stratospheric Cly to decrease at a slower rate than anticipated based on reductions in long-lived ODS emissions. These findings are important to consider when evaluating the progress of the Montreal Protocol and predicting the ozone recovery date.

Data and methods

Observations and model results

Observations from ACE-FTS22,40 are used to determine HCl and ClONO2 trends, as well as the altitude corresponding to a given mean age. We use HCl, ClONO2, and N2O profiles from version 5.2 of the ACE-FTS retrieval41. All trace gas profiles are filtered using the data quality flags developed by ref. 42 before any further analysis is performed. Trends are calculated in the area-weighted monthly zonal mean ACE-FTS observations for 10° latitude bins. The MZM age of air derived from v3.6 of the ACE-FTS SF6 retrieval33 is used to determine the altitude level corresponding to a given mean age. SF6 was used to derive the AoA because it has a long chemical lifetime in the stratosphere and a well-defined tropospheric trend.

The relationship between HCl+ClONO2 changes and Cly changes is determined using model simulations from CMAM34,35. CMAM is a vertically extended version of the Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis third-generation atmospheric general circulation model [AGCM3, ref. 43] that also includes interactive stratospheric chemistry. The CMAM results used here follow the REFD1 scenario, which includes forcing from observed sea surface temperatures, greenhouse gases, ozone-depleting substances, and volcanic aerosol44. Results from five ensemble members, each with slightly different initial conditions, are considered. The CMAM configuration does not include VSLS. Including VSLSs is not expected to change the scale factors, as the impact of VSLS would affect the Cly and HCl+ClONO2 trends in a consistent way.

The values for the Cl-VSLS trends are based on simulations from the UM-UKCA36 chemistry-climate model run in a specified-dynamics configuration19, with temperatures and zonal and meridional winds nudged to European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5 reanalysis45. The model configuration includes the explicit treatment of four of the most important Cl-VSLSs: CH2Cl2, CHCl3, C2Cl4, and C2H4Cl246. The modelled Cl-VSLSs are constrained at the surface by annual mean observations in five latitude bands. The CH2Cl2 and C2Cl4 surface values are from NOAA, the CHCl3 surface values are from AGAGE, and the C2H4Cl2 surface values are estimated from the HIPPO aircraft campaign14,46,47. Trends are calculated in the modelled stratospheric source gas injection (SGI) plus the product gas injection (PGI) of chlorine from Cl-VSLSs, which corresponds to the simulated concentrations at 17 km and from 20°S-20°N. We use the trend from 1999-2015 for comparison to 5.5-year-old air at mid-latitudes and the trend from 2001 to 2017 for the comparison to 3-year-old air at mid-latitudes to account for the transit time from the tropical tropopause region.

Trend calculations

Trends are calculated with a generalised least squares method using the Long-term Ozone Trends and Uncertainties in the Stratosphere (LOTUS) regression code48. Three different sets of proxies are considered, each of which is described in this section. In all cases, the uncertainties are defined as the 2σ error of the trend parameter estimate in the regression (95% confidence level). The uncertainties account for first-order autocorrelation in the residuals49.

The uncertainty in the mean Cly trend presented in Fig. 5 is calculated as

where N = 4, corresponding to the four latitude bins that are considered.

The Cl-EESC and Cl-VSLS trends are calculated with a simple linear regression, defined by the equation

where y(t) is the mixing ratio of either Cl-EESC or Cl-VSLS as a function of time, β is the constant term, βtrend is the trend, and R(t) is the residual. The linear(t) variable represents a linear function of time that is fit to the observations (the trend is the slope of this line).

Trends in HCl+ClONO2 are calculated in two ways: with the standard MLR and with the N2O MLR. The standard MLR is defined as

In Eq. (3) each βi defines a regression coefficient QBOa(t) and QBOb(t) are the first two principal components of the Singapore zonal winds, F10.7(t) is the solar flux at 10.7 cm, and ENSO(t) is the multivariate El-Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) index. The superscripts specify the number of seasonal harmonics included for a given term. Therefore, the coefficient for the constant term expands to

\({\beta }_{qboa}^{(2)}\) and \({\beta }_{qbob}^{(2)}\) are expanded similarly. There are 18 regression coefficients in total: one corresponding to each of the trend, ENSO(t), and F10.7(t) terms and five coefficients from each of the constant, QBOa(t), and QBOb(t) terms. Further details on this version of the regression model, the data sources for the proxies, and examples showing how the regression model can be used to calculate stratospheric ozone trends are provided in refs. 48,49.

The N2O MLR equation is

All terms are the same as in Eq. (3), except in this case the N2O(t) term represents all sources of dynamical variability, including ENSO, the QBO, and the BDC. The N2O proxy is the anomaly in the MZM ACE-FTS N2O mixing ratio, with the trend due to surface emissions of N2O removed. The proxy is therefore different in each latitude and altitude bin. Further details on the N2O proxy and MLR are provided in ref. 30.

Altitudes for a specified mean age

The ACE-FTS MZM age of air profiles are used to determine the altitude corresponding to each mean age. First, a cubic spline is fit to each MZM age of air profile, and then that curve is interpolated to the altitude corresponding to the specified mean age. The result is an MZM time series of the altitude corresponding to each mean age. This time series is then filtered by removing monthly values that are more than 5 median absolute deviations from the median. The mean altitude of the remaining values is taken as the altitude of 3- and 5.5-year-old air at each latitude.

For 3-year-old air, the altitudes are 18.5 km, 19.6 km, 20.1 km, 19.1 km for the latitudes 50°S, 40°S, 40°N, 50°N. For a 5.5-year-old air, the altitudes are 29.3 km, 30.2 km, 30.4 km, 29.6 km for the latitudes 50°S, 40°S, 40°N, 50°N. The ACE-FTS AoA has a vertical resolution of 3 km, so the difference in the altitude for each mean age across the four latitudes is smaller than the resolution of the data. We therefore present our results in terms of the average altitude across all four latitudes for each mean age: 19.0 km for 3-year-old air and 29.5 km for 5.5-year-old air.

Conversion of HCl+ClONO2 trends to Cly trends

We convert the ACE-FTS HCl+ClONO2 trend to a Cly trend using a scale factor from CMAM:

The CMAM HCl+ClONO2 and Cly trends are calculated with the N2O MLR to be consistent with the ACE-FTS trends. The ACE-FTS pressure profiles that are retrieved with each scan are used to determine the average pressure corresponding to the altitude of 3- and 5.5-year-old air, and then the scale factors are calculated from CMAM trends interpolated to this pressure level.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

ACE-FTS ClONO2, HCl, and N2O observations are available by registration at https://databace.scisat.ca/level2/50. ACE-FTS data quality flags are available from https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/NAYNFE51. ACE-FTS age of air is available from https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/5AC1F052 CMAM REFD1 simulations are available by registration from the CEDA archive, https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/uuid/3f06d743521f44a5ba8e666e11f66d6b/53.

Code availability

The LOTUS regression code and documentation are available at https://github.com/usask-arg/lotus-regression48.

References

Solomon, S., Garcia, R. R., Rowland, F. S. & Wuebbles, D. J. On the depletion of Antarctic ozone. Nature 321, 755–758 (1986).

Solomon, S. Stratospheric ozone depletion: a review of concepts and history. Rev. Geophys. 37, 275–316 (1999).

Laube, J. et al. Update on ozone-depleting substances (ODSs) and other gases of interest to the Montreal Protocol. Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022 GAW Report No. 278, Ch. 1, 53–113 (WMO, 2022).

Steinbrecht, W. et al. An update on ozone profile trends for the period 2000 to 2016. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 10675–10690 (2017).

Godin-Beekmann, S. et al. Updated trends of the stratospheric ozone vertical distribution in the 60S–60N latitude range based on the LOTUS regression model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 11657–11673 (2022).

Bognar, K. et al. Stratospheric ozone trends for 1984–2021 in the SAGE II–OSIRIS–SAGE III/ISS composite dataset. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 9553–9569 (2022).

Salawitch, R. J. et al. Sensitivity of ozone to bromine in the lower stratosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L05811 (2005).

Hossaini, R. et al. The increasing threat to stratospheric ozone from dichloromethane. Nat. Commun. 8, 15962 (2017).

Carpenter, L. J. & Liss, P. S. On temperate sources of bromoform and other reactive organic bromine gases. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 105, 20539–20547 (2000).

Butler, J. H. et al. Oceanic distributions and emissions of short-lived halocarbons. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 21, GB1023 (2007).

Stemmler, I., Hense, I. & Quack, B. Marine sources of bromoform in the global open ocean—global patterns and emissions. Biogeosciences 12, 1967–1981 (2015).

McCulloch, A. et al. Industrial emissions of trichloroethene, tetrachloroethene, and dichloromethane: reactive Chlorine Emissions Inventory. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 104, 8417–8427 (1999).

Claxton, T. et al. A synthesis inversion to constrain global emissions of two very short lived chlorocarbons: dichloromethane, and perchloroethylene. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2019JD031818 (2020).

Hossaini, R. et al. Recent trends in stratospheric chlorine from very short-lived substances. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 2318–2335 (2019).

Hossaini, R. et al. On the atmospheric budget of 1,2-dichloroethane and its impact on stratospheric chlorine and ozone (2002–2020). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 13457–13475 (2024).

Bednarz, E. M., Hossaini, R. & Chipperfield, M. P. Atmospheric impacts of chlorinated very short-lived substances over the recent past—Part 2: impacts on ozone. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 13701–13711 (2023).

Villamayor, J. et al. Very short-lived halogens amplify ozone depletion trends in the tropical lower stratosphere. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 554–560 (2023).

Hossaini, R. et al. Growth in stratospheric chlorine from short-lived chemicals not controlled by the Montreal Protocol. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 4573–4580 (2015).

Bednarz, E. M., Hossaini, R., Chipperfield, M. P., Abraham, N. L. & Braesicke, P. Atmospheric impacts of chlorinated very short-lived substances over the recent past—Part 1: stratospheric chlorine budget and the role of transport. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 10657–10676 (2022).

Adcock, K. E. et al. Aircraft-based observations of ozone-depleting substances in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere in and above the Asian summer monsoon. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2020JD033137 (2021).

Roozitalab, B. et al. Measurements and modeling of the interhemispheric differences of atmospheric chlorinated very short-lived substances. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2023JD039518 (2024).

Bernath, P. F. et al. Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment (ACE): mission overview. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L15S01 (2005).

Engel, A. et al. A refined method for calculating equivalent effective stratospheric chlorine. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 601–619 (2018).

Daniel, J. S., Solomon, S. & Albritton, D. L. On the evaluation of halocarbon radiative forcing and global warming potentials. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 100, 1271–1285 (1995).

Newman, P. A., Daniel, J. S., Waugh, D. W. & Nash, E. R. A new formulation of equivalent effective stratospheric chlorine (EESC). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 4537–4552 (2007).

Montzka, S. et al. Recent trends in global emissions of hydrochlorofluorocarbons and hydrofluorocarbons: reflecting on the 2007 adjustments to the Montreal Protocol. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 4439–4449 (2015).

Prinn, R. G. et al. History of chemically and radiatively important atmospheric gases from the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 985–1018 (2018).

Mahieu, E. et al. Recent Northern Hemisphere stratospheric HCl increase due to atmospheric circulation changes. Nature 515, 104–107 (2014).

Strahan, S. E. et al. Observed hemispheric asymmetry in stratospheric transport trends from 1994 to 2018. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088567 (2020).

Dubé, K. et al. N2O as a regression proxy for dynamical variability in stratospheric trace gas trends. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 13283–13300 (2023).

Bernath, P., Boone, C. & Crouse, J. Wildfire smoke destroys stratospheric ozone. Science 375, 1292–1295 (2022).

Stolarski, R. S., Douglass, A. R. & Strahan, S. E. Using satellite measurements of N2O to remove dynamical variability from HCl measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 5691–5697 (2018).

Saunders, L. N. et al. Age of air from ACE-FTS measurements of sulfur hexafluoride. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 25, 4185–4209 (2025).

Beagley, S., de Grandpré, J., Koshyk, J., McFarlane, N. & Shepherd, T. Radiative-dynamical climatology of the first-generation Canadian middle atmosphere model. Atmos. Ocean 35, 293–331 (1997).

de Grandpré, J. et al. Ozone climatology using interactive chemistry: results from the Canadian Middle Atmosphere Model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 105, 26475–26491 (2000).

Sellar, A. A. et al. UKESM1: description and evaluation of the U.K. Earth System Model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 4513–4558 (2019).

Millán, L. F. et al. Case studies of the impact of orbital sampling on stratospheric trend detection and derivation of tropical vertical velocities: solar occultation vs. limb emission sounding. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 11521–11534 (2016).

Damadeo, R. P., Zawodny, J. M., Remsberg, E. E. & Walker, K. A. The impact of nonuniform sampling on stratospheric ozone trends derived from occultation instruments. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 535–554 (2018).

Claxton, T., Hossaini, R., Wild, O., Chipperfield, M. P. & Wilson, C. On the regional and seasonal ozone depletion potential of chlorinated very short-lived substances. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5489–5498 (2019).

Boone, C. D. et al. Retrievals for the atmospheric chemistry experiment Fourier-transform spectrometer. Appl. Opt. 44, 7218–7231 (2005).

Boone, C., Bernath, P. & Lecours, M. Version 5 retrievals for ACE-FTS and ACE-imagers. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 310, 108749 (2023).

Sheese, P. E., Boone, C. D. & Walker, K. A. Detecting physically unrealistic outliers in ACE-FTS atmospheric measurements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 741–750 (2015).

Scinocca, J. F., McFarlane, N. A., Lazare, M., Li, J. & Plummer, D. Technical Note: The CCCma third generation AGCM and its extension into the middle atmosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 7055–7074 (2008).

Plummer, D. et al. CCMI-2022: a new set of Chemistry-Climate Model Initiative (CCMI) community simulations to update the assessment of models and support upcoming ozone assessment activities. SPARC Newsletter No. 57 (2021). http://www.sparc-climate.org/publications/newsletter. Accessed 2 April 2023.

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Bednarz, E. M., Hossaini, R., Abraham, N. L. & Chipperfield, M. P. Description and evaluation of the new UM–UKCA (vn11.0) Double Extended Stratospheric–Tropospheric (DEST vn1.0) scheme for comprehensive modelling of halogen chemistry in the stratosphere. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 6187–6209 (2023).

Wofsy, S. C. HIAPER Pole-to-Pole Observations (HIPPO): fine-grained, global-scale measurements of climatically important atmospheric gases and aerosols. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 369, 2073–2086 (2011).

Damadeo, R. et al. LOTUS Regression Code. SPARC LOTUS Activity (2022). https://github.com/usaskarg/lotus-regression. Accessed 23 Feb 2024.

SPARC/IO3C/GAW. SPARC/IO3C/GAW Report on Long-term Ozone Trends and Uncertainties in the Stratosphere SPARC Report No. 9, GAW Report No. 241, WCRP-17/2018 (2019).

ACE-FTS. Level 2 Data, Version 5.2 (2023). https://databace.scisat.ca/level2/. Accessed 15 May 2024.

Sheese, P. & Walker, K. Data Quality Flags for ACE-FTS Level 2 Version 5.2 Data Set (2023). https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/NAYNFE. Accessed 16 Sep 2024.

Saunders, L., Walker, K. & Stiller, G. Stratospheric Age of Air Derived from ACE-FTS and MIPAS SF6 (2025). https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/5AC1F0.

Plummer, D. CCMI-2022: refD1 data produced by the CMAM model at CCCma. NERC EDS Centre for Environmental Data Analysis (2023). https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/uuid/3f06d743521f44a5ba8e666e11f66d6b/. Accessed 05 Aug 2024.

Acknowledgements

K.D. was supported by the Canadian Space Agency (grant no. 21SUASULSO). The Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment (ACE) is a Canadian-led mission mainly supported by the CSA and the NSERC, and Peter Bernath is the principal investigator. Support for E.M.B. has been provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) cooperative agreement (NA22OAR4320151) and the Earth Radiative Budget (ERB) programme. R.H. and E.M.B. also acknowledge support from the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) SISLAC project (Sources and Impacts of Short-Lived Anthropogenic Chlorine; grant no. NE/R001782/1). The development of the ACE-FTS stratospheric age of air dataset was supported by a grant from the Canadian Space Agency (CSA; grant no. 16SUASCMEV).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.D. performed the analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. S.T. conceptualised and supervised the project. A.E. provided the code for the Cl-EESC calculation. J.L. provided the ODS mole fractions needed to calculate the EESC. L.S. provided the ACE-FTS age of air dataset. R.H. and E.B. provided the Cl-VSLS trends. All authors provided significant feedback on the method and the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Sandro Vattioni, Megan Lickley and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Mengze Li and Alice Drinkwater. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dubé, K., Tegtmeier, S., Bourassa, A. et al. Chlorinated very short-lived substances offset the long-term reduction of inorganic stratospheric chlorine. Commun Earth Environ 6, 487 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02478-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02478-9