Abstract

China is a major hotspot of black carbon (BC) emissions, contributing to climate warming and risk to public health. Here, our dual-isotope-constrained observations indicate stringent air pollution controls have drastically reduced coal-burning in North China over the past decade, marking a transition to a “post-coal” era compared to earlier 2012–2014. However, biomass-burning fraction (fbb) for north/central/east winter hazes has doubled from earlier (north/east) ~20%, with significantly higher fbb during polluted winters. Comparisons between observation and transport modelling show good alignment in BC concentrations but substantial discrepancies in source attribution (i.e., fbb). Leveraging radiocarbon measurements, advanced atmospheric modelling, and a Bayesian approach, our study identifies biases stemming from misallocated residential fuel types in emission inventories. These findings underscore the untapped potential to mitigate BC emissions by targeting rural biomass burning, while providing critical insights into BC source evolution to refine emission inventories and formulate effective air quality policies for China and other nations facing severe air pollution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

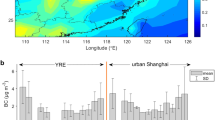

Faced with persistent severe air pollution1, a major economic and social issue, China adopted the toughest-ever clean air actions in 2013 aimed at reducing particulate matter concentrations in emission hotspots2, such as the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region (BTH, with Tianjin as a representative regional site for BTH) and the Yangtze River Delta (YRD, including Shanghai and Hefei in Fig. 1a). Data from China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment indicate a 30% drop in annual average PM2.5 (particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 2.5 µm) levels from 2013 to 2017, and slight improvements since then3. However, unexpected haze events have persisted in recent years4,5,6; and satellite-based aerosol optical depth (AOD) maps also reveal a 1000 km diameter pollution ring, affecting more than 600 million people, despite varying reductions in AOD since 2013/2014 (Fig. 1a, b). Recent emission inventory-driven models suggest that while China’s clean air initiatives have improved PM2.5 air quality, air pollution and PM2.5-related health issues remain critical7,8,9. Emission control measures may alter the sources and evolution of aerosols, at least for inorganic sulfate-nitrate-ammonium9,10, introducing new uncertainties and complexities to East Asian aerosols.

Prefixes ‘aut’, ‘win’, ‘spr’ and ‘sum’ in the x-Tick-Label denote autumn (September-October-November), winter (December-January-February), spring (March-April-May) and summer (June-July-August), while suffix numbers show the campaign year. For example, 12 denotes 2012, and ‘win 12’ refers to the 2012 winter (December 2012, January and February 2013). a Sampling sites: Tianjin and Beijing in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of North China; Kaifeng in the Central Plains of China; Hefei in the west of Yangtze River Delta (YRD); Shanghai and YRE (Yangtze River Estuary, Shanghai Chongming Island) in eastern YRD; Yantai on the east coast of Shandong Peninsula. AOD (550 nm) map showing high-loading aerosols spreading from north over central to east China from Dec. 2018–Mar. 2023. b The AOD changes (ΔAOD) equals the average (Dec. 2018–Mar. 2023) AOD minus the average (2013–2014) AOD. c Seasonal variability of PM2.5 BC concentrations (mean ± SD) at Tianjin (BTH annotated for Tianjin), the 2012–2014 BTH data from refs. 33,34. and 2013 winter Beijing data from ref. 33. d Hefei from 2016 to 2019, and Kaifeng from 2021 to 2023. e Yantai from 2020 to 2023, YRE data from ref. 4, 2012–2014 YRD (Haining) and Shanghai data from refs. 33,34. The error bars in (c–e) denote the SD of seasonal BC concentrations. The seasons with no data in (c–e) is due to a lack of sampling. The number of seasonal samples is indicated by ‘n’ in (c–e). AOD data were obtained from NASA Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) level 3 collection 6. Notice that the ordinate scales are different in each panel.

BC, released during incomplete combustion of biomass and fossil fuels, is the primary light-absorbing component of PM2.511,12,13. It significantly contributes to positive radiative forcing and poses serious health risks, particularly in high-concentration hotspot regions over Asia11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Over the past decade, stringent emission controls responding to severe air pollution, along with China’s industrialization and economic development, have created unprecedented uncertainties regarding BC emissions. However, knowledge of recent decade trajectories of BC levels and source changes within China’s prevailing pollution ring is scarce, yet vital for advancing measures to reduce climate warming and predicting source-related implications. Bottom-up emission inventories (EIs) are widely used in climate and air quality models to assess the effects of BC11,12,23,24,25,26,27, yet models lack observational constraints since China’s clean air actions4. Atmospheric chemistry transport models, essential for validating inventories used in mitigation policy discussions, face challenges to accurately reproduce BC levels, especially concerning source attributions in East Asia and the remote Arctic4,28,29,30. A major cause for these model-observation discrepancies is the large uncertainty of the underlying EIs4,12,24,25,26,27,28,29,30.

To address these knowledge gaps, we hypothesize that the unprecedented air quality control measures implemented since 2013 have substantially altered the spatial distribution and source contributions of BC across China’s prevailing pollution ring. Consequently, current bottom-up EIs may not accurately represent the real-world sources and trends of BC emissions. This study aims to test this hypothesis by applying multi-year isotopic observations (δ¹³C/∆¹⁴C) across multiple key sites combined with atmospheric transport modelling, to assess the decadal evolution of BC sources and identify potential biases in existing inventories.

Top-down source constraints are crucial for evaluating measures and developing successful mitigation strategies. However, BC (hereafter elemental carbon (EC), the mass-based analog, is used as BC)12,31 observations in China exhibit geographical and temporal biases. They primarily focus on North China, megacities and short-term winter haze events from 2012 to 2014 refs. 32,33,34,35,36,37,38, while lacking long-term data on source diagnostic dual-isotopic composition (δ13C/∆14C) across the pollution ring (Fig. 1a)4. Here, we present new multi-year δ13C/∆14C-based source apportionment of BC in PM2.5 for Tianjin (BTH annotated for Tianjin hereafter), Kaifeng (in the central China Plain), Yantai and Hefei (Fig. 1a), covering the period 2016–2023. These records, together with data from our 2018–2020 Shanghai study4, are compared to previously published data of BC concentrations and isotopic signatures from the 2012–2014 campaigns in BTH34, Beijing33, Shanghai33 and YRD34 to decipher the decadal evolution of BC sources. The radiocarbon signature (∆14C) enables precise quantification of fbb (containing modern 14C) and fossil fuel combustion fraction (ffossil; devoid of 14C)39,40,41. The combination of δ13C and ∆14C can further distinguish liquid fossil vs coal in BC4,32,33,34. BC observations from each site of the prevailing pollution ring, since China’s clean air actions, are then compared with respective simulations from the atmospheric transport model FLEXPART (flexible particle dispersion model)28,30, coupled to ECLIPSE (Evaluating the Climate and Air Quality Impacts of Short-Lived Pollutants) version 6 BC23,25 and open-fire BC emissions from Global Fire Emission Database (GFED) version 4s42 EIs. The FLEXPART-ECLIPSE-GFED (FEG) set-up has shown to predict the observational data effectively4,29,30. Finally, a Bayesian approach utilizing the observed ∆14C and FEG model results is employed to identify potential deficiencies in EIs for seasonal residential fbb in key emission provinces (Supplementary Note).

Results

BC concentration changes

Recent observations reveal a consistent seasonal pattern across inter-site, intra-sites and interannual, with the lowest BC and PM2.5 (for PM2.5 levels, see Supplementary Fig. 1) concentrations occurring in summer (e.g., Yantai-BC: 1.0 ± 0.1 µg m−3) and peaks in winter (e.g., Kaifeng-BC: 4.5 ± 1.6 µg m−3; Fig. 1c–e). Kaifeng recorded the highest frequency of elevated levels of BC (8 µg m−3) and PM2.5 (150–200 µg m−3) in winter haze, followed by Tianjin, Hefei, Shanghai and Yantai (time series of BC concentrations measured at each site are provided in Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables 1–5), highlighting Central and North China as regions most affected by severe aerosol pollution (for China administrative map of provinces and cities, see Supplementary Fig. 3).

Notably, wintertime BC concentrations in North China (Tianjin and Beijing) have declined by half compared to 2012–2014 levels, dropping from 8.5 ± 4.0 µg m−3 in 2013 Beijing winter and 8.3 ± 3.2 µg m−3 in 2013 Tianjin winter33 to e.g., 4.1 ± 1.6 µg m−3 in 2021 Tianjin winter. In Hefei (western YRD), BC concentrations also decreased from 6.1 ± 1.6 µg m−3 in the 2016 winter to 3.8 ± 1.6 µg m−3 in the 2018 winter. In contrast, winter BC concentrations in Shanghai have remained persistently high, exceeding January 2014 levels33; this sustained elevation is likely attributed to the trans-provincial influx of pollution while the oceanic air diluted earlier (January 2014) samples4. FLEXPART model outputs, seasonal (mean) potential FES, suggest that air masses arriving at the five measured sites shift by season, with footprints primarily originating from local provinces and heavily influenced by neighbouring provinces and nearby upwind regions (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 4–6).

Triangle on each map shows the air arriving site (sampling site) of aerosol BC FES. The north-to-south circles (and triangle) denote locations of Beijing, Tianjin, Yantai, Kaifeng, Hefei, YRE (Shanghai Chongming Island) and urban Shanghai, respectively. Average model output for wintertime samples collected at a Tianjin from this 2020–2023 study, b Kaifeng from this 2021–2023 study, c Yantai from this 2020–2023 study, d Hefei from this 2016–2019 study and e YRE (Shanghai) in previous (2018–2019) campaign4.

In addition to variations in emissions, factors such as air transport, aerosol lifetime, meteorological conditions and aerosol boundary layer dynamics can impact BC and PM2.5 concentrations over periods ranging from days to weeks at the observation sites. However, with year-by-year, highly intensive sampling and measurement, the effects of meteorological condition variation, measurement uncertainties or atmospheric processes should be relatively minor8,30,43. In summary, the overall declining trend in BC concentrations across different sites aligns with observed reductions in aerosol3,8 and AOD levels in China’s key regions over (Fig. 1a, b) the last decade, with a more pronounced decrease in North China than in East China.

Rapid changes in sources from dual-carbon-isotope fingerprints

Analysis of Δ14C and δ13C signatures of BC offers direct, observationally-based constraints on the relative contributions of major sources. Here we observe distinct seasonality in Δ14C-BC—the Δ14C signal is directly translated into the fraction of biomass burning (fbb)—across all sites, with higher contemporary biomass burning during winter and spring yet significantly lower values in summer and autumn since 2018 (Fig. 3b, c, e, f). Specifically, radiocarbon signals from 2020 to 2023 show clear seasonal stratification in Tianjin, with high fbb prevalent in winter haze, moderate levels in spring and autumn, and the lowest in the relatively clean summer. This pattern closely mirrors the seasonal variation observed in Hefei and Shanghai4 within the YRD since 2018, despite the regions being over a thousand kilometres away. In Kaifeng and Yantai, winter is characterized by elevated fbb, contributing to increased BC and haze levels, while spring shows the highest fbb.

The term “Source Transition” refers to the major shifts in the relative contributions of biomass burning, coal combustion and liquid fossil fuel combustion to BC aerosol over the past decade, as revealed by Δ¹⁴C and δ¹³C measurements. The fbb is calculated by Eq. (1) in Method. The expected Δ14C and δ13C endmember range for biomass, liquid fossil and coal fossil (Supplementary Table 7) are shown as green, grey and yellow rectangles, respectively. The circle area shows BC aerosol concentrations in µg m–3 (see scales with black circles on the bottom-right side). a The shifts of carbon isotope signatures in North China (Tianjin (BTH) and Beijing (BJ)) and East China (Shanghai (SH) and Shanghai Chongming Island (YRE)) since 2012. The 2012–2014 BTH data from refs. 33,34. and 2013 winter Beijing data from ref. 33. b Seasonal isotope signatures of BC at Tianjin (BTH). The black, green, red and blue respectively represent winter, spring, summer and autumn in the current campaigns. The numerical suffix indicates the campaign year. For example, ‘winter 20’ refers to 2020 winter (December 2020, January and February 2021). c Seasonal isotope signatures of BC at Kaifeng in the Central China Plains. d The shifts of BC isotope signatures in wintertime haze events at Hefei (HF) and Shanghai (SH) in East China during China’s clean air actions. YRE data from ref. 4. and urban Shanghai data from refs. 4,33. e Seasonal isotope signatures of BC at Yantai on the east coast of Shandong Peninsula. f Seasonal isotope signatures of BC at Hefei in the western YRD. Uncertainties are less than 0.2‰ for δ13C and 5‰ for Δ14C (corresponding to <1% for fbb) and thus not shown here because they are much smaller than the diameter of the circles (all dual-isotope data are provided in Supplementary Table 8).

In Hefei, isotopic data from 2016 to 2019 reveal a transition pattern in winter haze, akin to the shifts observed in Shanghai when comparing the recent winters to those of 2013–2014 refs. 4,33. (Fig. 3d). Strikingly, significant changes in the BC isotopes have also been observed in recent winters in North China (Tianjin), with an increasing fbb and depleted δ13C (indicating a shift away from the coal endmember) compared to the winters of 2012 and 2013 refs. 33,34. (Fig. 3a). This shift in radiocarbon signature parallels the changes observed in Shanghai and Hefei, resulting in a convergence of isotope signals between North and East China during winter haze. Notably, these isotope signatures, which differed markedly a decade ago due to distinct emission sources and meteorological conditions, now show substantial overlap (Fig. 3a, d). This convergence in dual-isotope signatures reflects a broader source transition—that is, a shift from historically coal- and liquid fossil-dominated emissions toward an increasing dominance of biomass burning in winter haze pollution.

In addition to radiocarbon signatures, the stable carbon isotopic ratio (δ13C) of recalcitrant BC adds a dimension where sources can be further distinguished between biomass, liquid fossil and coal. We applied a Bayesian Monte Carlo model (MC; “Methods”) that accounts for variability in δ13C and Δ14C in both samples and source endmembers to provide statistically robust estimates of relative source contributions with comprehensive uncertainty (see “Methods” of MC source analysis). The MC calculations reveal significant geographical variability and substantial (re-occurring) seasonality in BC source contributions since 2018 (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 7). Certain regions display similar patterns of seasonal source shifts and cycles. For instance, Tianjin, Hefei and Shanghai show comparable seasonal oscillations in source proportions, with a rise in the fraction of liquid fossil combustion (fliq. fossil) from its lower level in winter (e.g., Tianjin: 0.23; Hefei: 0.30) to its peak in summer (e.g., Tianjin: 0.61; Hefei: 0.62). Conversely, fbb increases from its lowest ratio in summer (e.g., Tianjin: 0.24; Hefei: 0.22) to its peak in winter (e.g., Tianjin: 0.46; Hefei: 0.43). The seasonality of fcoal is less pronounced in Hefei and Shanghai (Hefei: 0.15–0.26) compared to Tianjin (0.15–0.34). Yantai exhibits the largest seasonal amplitude in both fbb (0.21–0.62) and fliq. fossil (0.20–0.62), while Kaifeng exhibits the least seasonality across all three sources. In both Yantai and Kaifeng, spring and winter are dominated by high fbb, followed by fliq. fossil and fcoal.

a The comparison of source contributions (biomass, liquid fossil and coal burning) of BC isotope samples collected at Tianjin (BTH) in North China from this 2020–2023 study compared to the previous 2012–2014 studies33,34. b MC-simulated mean source contributions of BC isotope samples collected at Kaifeng in the Central Plains of China from 2021 autumn to 2023 spring. c MC-simulated mean source contributions of BC isotope samples collected at Yantai in the Shandong Peninsula from Dec. 2020–Mar. 2023. d MC-simulated mean source contributions of BC isotope samples collected at Beijing in North China from the previous January 2014 haze study33. e MC-simulated mean source contributions of BC isotope samples collected at Hefei in the western YRD from Apr. 2016–Dec. 2019 (without sampling from Oct. 2017–Nov. 2018). f MC-simulated mean source contributions of BC isotope samples collected at urban Shanghai in January 2014 ref. 33 and 2019 ref. 4, and at YRE ref. 4. (Shanghai Chongming Island) from Dec. 2018–Nov. 2019. The x-axis dates represent the sampling start dates for each individual isotope sample. Each data point corresponds to one specific measurement; see Supplementary Table 8 for detailed sample dates and information. All MC-simulation results are provided in Supplementary Table 8 and the SD for data in (a–f) are provided in Supplementary Fig. 14. The white gap and break are due to the lack of sampling.

Figure 4 and Supplementary Fig. 7 highlight the significant changes in BC source contributions across China over the past decade. Following clean air initiatives, there has been a notable increase in fbb during winter in both North and East China. In the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, fbb rose from ~0.20 during the 2012–2014 winters to 0.35–0.43 in recent winters, with a similar trend also observed in Shanghai. Conversely, fcoal in Tianjin dropped from 0.52 to 0.59 in 2012–2014 to 0.26 recently, while fliq. fossil in Shanghai decreased from 0.61 in 2013 to 0.30. Hefei has also experienced a marked increase in fbb and a decrease in fliq. fossil during the air-cleaning actions period (e.g., from 2016 to 2019).

By combining source fractions with BC levels, a clear hierarchy emerges across North, Central and East China, with biomass burning now the largest contributor to winter haze, followed by liquid fossil- and coal-combustion (Fig. 5). Biomass burning is particularly prominent during both annual and haze periods in the Central Plains and Shandong regions. Strikingly, the concentrations of both total BC and coal-burning-derived BC have significantly decreased during recent winters in North China compared to levels observed in 2012–2014 refs. 33,34. The significant reduction in BC concentrations in BTH is primarily due to the emission control of coal combustion in the BTH region, for example, implementation of control measures in residential and coal-fired power plants and industrial boilers. This trend highlights the remarkable effectiveness of the clean air actions in reducing coal combustion emissions in this region. However, the concentrations of BC derived from liquid fossil fuels (e.g., vehicle emissions and industrial processes) and biomass burning have remained relatively constant over the same period. These findings underscore the need for further enhancement of control measures targeting emissions from liquid fossil fuel combustion and biomass burning to achieve comprehensive air quality improvements.

Source concentrations were calculated using BC concentration multiplied by the MC-simulated mean fraction of sources. a The significantly declined BC emissions from coal burning in this 2020–2023 winter haze study in Tianjin compared to the previous 2012–2014 winter haze study in BTH33,34. b Source concentrations to BC isotope samples collected at Kaifeng in the Central China Plains from 2021–2023. c Source concentrations to BC isotope samples collected at Yantai in the Shandong Peninsula from 2020–2023. d Source concentrations to BC isotope samples collected at Beijing in North China from the previous January 2014 winter haze study33. e Source concentrations to BC isotope samples collected at Hefei in the western YRD from 2016–2019 (not sampling from October 2017 to November 2018). f Source concentrations to BC isotope samples collected at urban Shanghai in January 2014 ref. 33 and 2019 ref. 4, and YRE ref. 4. (Shanghai Chongming Island) from December 2018 to November 2019. The x-axis dates represent the sampling start dates for each individual isotope sample. Each data point corresponds to one specific measurement; see Supplementary Table 8 for detailed sample dates and information. The SD for data in (a–f) are provided in Supplementary Fig. 15. The white gap and break are due to the lack of sampling.

Hefei has also experienced significant improvements in air quality following the implementation of clean air actions, evidenced by a substantial reduction in BC concentrations. This reduction is primarily attributed to effective control measures targeting liquid fossil fuel combustion emissions, including those from liquid-fossil-fueled motor vehicles and the petrochemical industry. However, in the YRD region, biomass burning emissions in Hefei and Shanghai have not decreased during recent winters, remaining a major contributor to seasonal haze.

In contrast, cities such as Kaifeng and Yantai in central China plains and Shandong Peninsular have consistently recorded high concentrations of biomass-burning-derived BC during winter and spring haze events over recent years. The persistence of similar source concentration structures across consecutive winters and springs suggests a relative stability and repetitiveness in BC sources in these regions. This pattern indicates that central and eastern China and Shandong Peninsular may be hotspots for severe biomass-burning BC emissions. They potentially serve as major source regions of biomass-burning-derived BC for nearby large urban centres and, thus, contribute largely to the prevailing aerosol pollution ring in China.

Implications from model-observation comparison

FEG coupling shows that BC sources at the sampling sites are primarily influenced by emissions from local and nearby provinces (Supplementary Figs. 9–12). Comparing model predictions with source-diagnostic observations provides a means to enhance understanding of BC emissions and to evaluate the quality of the underlying EIs used in the simulations. Overall, FEG simulations captured the observed concentrations and seasonality of BC well at the five measurement sites located around the pollution ring (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 8; R = 0.64 for all 587 samples at the five sampling sites), although some deviations were noted. Specifically, in Tianjin and Kaifeng, the model slightly overestimated BC concentrations for several winter samples; a possible reason may include that EIs underestimating the effects of clean air actions. Conversely, in spring, the model underestimated BC levels for several samples in Kaifeng, Yantai and Tianjin, which could be attributed to missing emissions in the inventories, such as unrecorded wildfires captured by GFED. In Hefei, FEG-modelled BC concentrations for 2018–2019 matched observations more closely than for 2016–2017, suggesting that earlier inventories may have underestimated emissions from local and nearby provinces. Beyond uncertainties in EIs, modelling BC transport remains inherently challenging due to complex atmospheric processes such as dry deposition, precipitation scavenging and diabatic transport under strong surface-based inversions28,30.

While the FEG well reproduced concentrations, its source predictions are less accurate when compared to 14C constraints. In Tianjin, the model overestimated or underestimated fbb during winter and overestimated the fbb for 2016–2017 Hefei (Fig. 6a, d). The largest model-observation discrepancies in fbb occurred in Kaifeng and Yantai, where the model consistently underpredicted fbb by approximately 20–30 percentage points (Fig. 6b, c). The fbb underestimation by the FEG model is not only in China but was also observed at Arctic sites such as Alert (Canada), Zeppelin (Svalbard), Barrow (Alaska), Abisko (Scandinavia) and Tiksi (Siberia), where the FEG-modelled fbb for October-April were factor 3 lower than 14C observations29,44. The underlying causes leading to this underestimation by FEG remain unclear.

Model-observation comparison of fbb in a Tianjin, b Kaifeng, c Yantai, d Hefei and e YRE. The observed fbb (orange) was obtained from the 14C measurements, while the FEG-modelled fbb was calculated based on FEG coupling. The original FEG model fbb (blue dash) refers to the sum of biomass-burning BC concentration contributed by each emission sector (e.g., residential, waste, energy) from various provinces (and other regions) plus GFED wildfire BC concentration to the sampling site compared to the total BC concentration calculated by the FEG model for the sample. The revised FEG model fbb (black) is recalculated following the same protocol but using revised seasonal residential fbb in main emission provinces from Bayesian MC calculations (Supplementary Note). The correlations of fbb between the FEG model (original and revised) and observation are provided in Supplementary Fig. 13. The x-axis dates represent the sampling start dates for each individual isotope sample. Each data point corresponds to one specific measurement; see Supplementary Table 8 for detailed sample dates and information.

Assuming the accuracy of the transport model and satellite wildfire data interpretation, comprehensive long-term 14C datasets across main emission provinces in China provide means to address the offset in fbb. A Bayesian MC method was employed to estimate seasonal fbb in the residential sector—the dominant biomass-burning contributor—in key emission provinces in China. This approach utilized observed 14C data as prior information to estimate posterior distributions of (province) seasonal residential fbb, combined with the original FEG-modelled BC loadings for each sector and province (see Supplementary Note for method details). Our results indicate that residential fbb for the main emission provinces has apparent seasonal fluctuations and has increased significantly in most provinces compared to EIs (Supplementary Table 6). The revised FEG-modelled fbb, which was recalculated using revised (province) seasonal residential fbb, shows significant improvement across these regions (Fig. 6). Only several spring samples showed a notable model-observation offset in both BC concentrations and revised FEG-modelled fbb, possibly due to the lack of local biomass-burning activities—such as small-scale agricultural burning, residential biomass use, wild grass fires, and open waste burning—in the EIs. The much-improved linear correlations between posterior results and observations suggest that EIs have likely underestimated fbb, particularly in the residential sector, across major emission provinces in China (Supplementary Fig. 13). These findings also hold important implications for enhancing model accuracy in predicting sources in the Arctic. Posterior emissions may be affected by several uncertainties, including potential misestimations of sectoral emissions in the EIs4,23,25, inaccuracies in wildfire estimates45, the relatively large standard deviation of the numerical model and uncertainties in the atmospheric transport model28,29,30,44,45. However, the significantly improved posterior across all sites (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 13), combined with well-constrained ¹⁴C analysis (uncertainty <5%), indicates that updates to the EIs are necessary to accurately reflect changes in China’s BC emission sources.

Discussion

Our comprehensive isotope-based observations combined with modelling provide a more precise assessment of BC source transitions, offering critical insights into the impact of clean air policies and a robust scientific underpinning for further reducing BC emissions. The findings reveal that the shifts in BC sources across China’s largest pollution regions have been unprecedentedly significant since the implementation of clean air actions. The decline in fossil-fuel-derived BC in North China, driven by stringent coal-burning regulations, underscores the success of these emission control measures. While stringent emission controls on power plants, industry, liquid-fossil-fueled vehicles, and (the BTH region) residential coal burning2,3,22 have notably reduced emissions—aligning with the observed decrease in fossil-fuel-derived BC—biomass burning from residential sources remains persistently high and has emerged as the single largest contributor to haze events across China’s pollution ring, particularly in central China, a previously understudied area. Residential biofuel emissions in rural areas continue to pose significant challenges, often overlooked in policy frameworks despite their considerable impact on regional air quality and population exposure. Mitigation strategies, such as promoting BC-free stoves, transitioning to cleaner fuels (e.g., natural gas or electricity), and improving plume filtration technologies, offer promising avenues for reducing emissions. However, these measures must balance cost and accessibility to ensure sustainable adoption, particularly for low-income households.

Through dual-isotope-constrained observations, advanced atmospheric transport modelling, and Bayesian approaches, we identify substantial discrepancies between observed BC sources and EIs. These discrepancies stem from the misallocation of residential fuel types with EIs underestimating residential biomass burning in major emission provinces. These findings underscore the necessity of refining EIs and integrating seasonal and regional variations to enhance policy efficacy and model accuracy.

Taken together, this study provides crucial insights into the evolving sources of aerosol pollution in China, offering valuable lessons for air quality and climate policy globally. Our findings highlight the need to strengthen existing emission reduction measures (for cutting emissions from liquid-fossil-fueled vehicle and coal-combustion) and underscore the untapped potential for further BC emission reductions in China—for example, by cutting residential biomass burning emissions across large rural areas in northern, central and eastern China. Such measures would mitigate climate warming and health risks while providing broader implications for designing future clean air policies in China and other nations suffering from severe air pollution11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,46,47. Continuous monitoring and improved emission controls are vital for achieving sustainable air quality improvements and long-term climate goals.

Methods

The sampling campaign and concentration analysis

The multi-year PM2.5 sampling campaigns in this study were conducted in Tianjin (representative for Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region in North China; BTH), Kaifeng (Henan province in Central China), Yantai (Shandong province in east of North China Plain), Hefei (Anhui province in western YRD). PM2.5 samples for urban Shanghai and its suburban Chongming Island (YRE) are from ref. 4, while earlier samples for Beijing, Tianjin and Haining (Haining in Zhejiang in YRD) are from previous studies33,34. In total, 145, 75, 109 and 187 PM₂.₅ samples were collected on pre-combusted (500 °C for 24 h) quartz-fibre filters using high-volume samplers equipped with a PM₂.₅ impactor in Tianjin (from Nov. 2020 to Mar. 2023), Kaifeng (from Oct. 2021 to Mar. 2023), Yantai (from Dec. 2020 to Mar. 2023), and Hefei (from Apr. 2016 to Sept. 2017 and from Dec. 2018 to Dec. 2019), respectively. Further detailed information regarding the coordinates of sampling sites, sampling times and volumes, and measured BC concentrations is provided in Supplementary Tables 1–5.

The concentrations of OC and BC (here refers to EC, the mass-based analogue of optically-defined BC) were measured by a standard thermal/optical carbon analyzer (Desert Research Institute, DRI Model 2001) using the IMPROVE_A protocol48. The relative standard deviation of triplicate analysis was <5% for BC and TC. BC was not detectable in the blanks (n = 20). In addition, the instrument was well calibrated by standards at high frequency (e.g., performed calibration/standard every 10 samples) before and during sample analysis.

Dual-carbon isotope analysis

For BC isotope analysis, in total 156 samples, including 28, 36, 34, 42 and 16 samples from Tianjin (from Dec. 2020 to Mar. 2023), Kaifeng (from Oct. 2021 to Mar. 2023), Yantai (from Dec. 2020 to Mar. 2023), Hefei (from Apr. 2016 to Jul. 2017 and from Jan. 2019 to Nov. 2019) and YRE (from Dec. 2018 to Nov. 2019; plus urban Shanghai)4 with relatively high loadings across seasons, were chosen and isolated for subsequent δ13C and ∆14C analysis. In principle, at least three representative high-concentration samples (e.g., winter haze) were selected for isotope measurement in each quarter. The 140 samples from Tianjin, Kaifeng, Yantai and Hefei were pooled into 100 composites for dual-isotope analysis, but with one sample failed for 14C measurement. The approach of BC isolation by thermal/optical carbon analyzer is the same as the recent study4 using thermal-optical protocol and similar to the previous studies29,32,33,34,44. Before OCEC analysis and BC isolation, the filter samples were acid-fumigated with 2 M HCl (inside a desiccator for 24 h and subsequently dried at 60 °C for 3 h) to remove carbonates and to prevent their charring effect during pyrolysis29,32,33,34,44. Total sample size was at least 50 µg BC. Finally, the dried preserved BC samples were analyzed for high-precision natural 14C abundance and 13C/12C ratio using Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (i.e., MICADAS, Ionplus AG, Switzerland) facility and Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer at the US-NSF NOSAMS Facility (Woods Hole, MA, USA). Radiocarbon and stable carbon isotopic values are reported on a per mil scale as ∆14C and δ13C, respectively29,32,33,34,35,44. Values of δ13C were reported in per mil (‰) relative to the international standards Vienna PeeDee Belemnite, and the analytic precision is better than ±0.2‰. All Δ14C results were corrected for δ13C fractionation and for 14C decay for the time period between 1950 and the year of sample collection. The precision of 14CO2 gas measurements for the international standard Oxalic Acid (OxII, NIST SRM 4990C) is better than 10‰.

The relative contributions to atmospheric BC from contemporary biomass-burning (fbb) sources and radiocarbon-extinct fossil (ffossil) sources can be calculated with an isotopic mass balance equation29,32,33,34,35,39,40,41,44:

where Δ14Csample represents the radiocarbon signature of a sample, Δ14Cbb is the endmember of the contemporary radiocarbon, and Δ14Cfossil is defined as −1000‰, since fossil fuel is completely devoid of 14C. The contemporary Δ14Cbb signature depends on the biomass type, age and year of harvest. The Δ14C signatures of atmospheric CO2 are around +50‰ (that is, applicable for crop residue burning)49. In China, freshly younger biomass (e.g., crop residual and younger wood burning) is dominant and Δ14Cbb = +70 ± 35‰ is determined by combining EIs with endmember differences in biomass (for Δ14Cbb determination, see ref. 4). The conservative estimates for combined uncertainties of endmember and 14C measurement introduced an fbb variability of <5%.

Monte Carlo (MC) source analysis

The dual-carbon isotope signatures of BC were used in combination with our MC method to further constrain the relative contributions from three combustion sources: biomass-burning (fbb), coal (fcoal), and liquid fossil-fuel (fliq fossil). The isotopic mass balance is described by the following relation4,29,32,33,34,44:

Here, f is the fractional contribution of a given source, and subscripts of “sample”, “bb”, “liq fossil” and “coal” denote the investigated sample, biomass-burning, liquid fossil- and coal-combustion, respectively. The last row ensures the mass-balance principle. Supplementary Table 7 provides source signatures (fuel endmembers, mean ± SD) of radiocarbon Δ14C and stable carbon δ13C used in the MC simulation. The MC calculations were performed using the measured Δ14C and δ13C data, the fuel endmembers, and Eq. (2) with 100,000 iterations. The MC numerical simulations outputted the posterior probability density functions (PDF) of the relative source contribution of three major sources (liquid fossil, coal and biomass burning) for BC aerosols. The mean modelled fraction of the relative source contribution and the numerical spread (normal distribution) can be derived from this PDF (frequency ≥0), allowing the computation of the mean and SD of the modelled sources. The uncertainty ranges (SD) of the source endmember values for δ¹³C were determined based on the reported variability in previous studies across East Asia4,29,32,33,34,44. These SDs were incorporated into the MC simulations for dual-isotope source apportionment. Given the distinct Δ¹⁴C endmembers for biomass burning and fossil fuels, the uncertainty of the biomass burning fraction (fbb) estimates is generally low (typically <1%). In contrast, due to the overlap between coal and liquid fossil fuel δ¹³C values, the uncertainties for coal and liquid fossil fractions can be larger, sometimes reaching ~15% (see Supplementary Fig. S14 for detailed distributions).

FLEXPART-ECLIPSE-GFED transport modelling

To simulate the BC concentrations arriving at sampling sites in Tianjin, Kaifeng, Yantai, Hefei and YRE, the FLEXPART-ECLIPSE-GFED (FEG) model was used, comprising of the atmospheric dispersion model FLEXPART version 10.4 refs. 50,51,52, coupled with the ECLIPSE version 6B25 EI and satellite-based open fire emissions by GFED version 4.1s42. FLEXPART version 10.4 ran in backward mode from the station location at the 5 measurement sites and for the exact same periods as the measurements. A mean particulate diameter of 250 nm was used, with a logarithmic size distribution of 0.3. Simulations extended 30 days back in time, which is sufficient to include most emissions injected into an air mass arriving at the station, given a typical BC lifetime of roughly a week. The simulations used operational meteorological analysis data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) at a resolution of 1° × 1° latitude/longitude. FLEXPART accounts for dry deposition and wet scavenging of particle, differentiating between below-cloud and in-cloud scavenging. Anthropogenic BC emissions were received from the ECLIPSE version 6B25, which is based on the greenhouse gas–air pollution interactions and synergies model53. The emissions were explicitly split between biofuels (modern; e.g., agricultural waste burning) and fossil fuels emissions (Supplementary Table 9). Emissions from agricultural waste burning/wildfires were not accounted in ECLIPSE EIs, and they were adopted from GFED. The most recent version (4.1 s) of GFED was applied42. This satellite-based emission inventory was used with in daily resolution, while the spatial resolution was 0.5° × 0.5° to match ECLIPSE’s resolution.

Data availability

The observational (measured) data that support the findings of this study are provided in SI and can be also accessible at https://zenodo.org/records/15656064. Bayesian MC simulation results for BC sources and seasonal residential fbb in nine major emission provinces are archived on the Zenodo repository (https://zenodo.org/records/15656064). FEG Model outputs can also be seen at https://atmo-access.nilu.no/China_Cui.py. The surface PM2.5 observational data from the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment can be obtained from https://quotsoft.net/air/. EI data for GFED is freely available and can be found on the website www.globalfiredata.org/data.html. The data for BC emissions for different emission scenarios of ECLIPSE is freely available from IIASA.

Code availability

The FLEXPART model is freely available to the scientific community and can be downloaded from https://www.flexpart.eu/. Meteorological fields to run FLEXPART can be downloaded from ECMWF following their terms/guidelines.

References

Cao, J. J. Pollution status and control strategies of PM2.5 in China. J. Earth Environ. 3, 1030–1036 (2012).

Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan State Council Document Number 37 [in Chinese] www.gov.cn (Central Government of the People’s Republic of China, 2013).

Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China, 2017 to 2022 Report on the State of the Ecology and Environment in China (accessed August 2024) https://english.mee.gov.cn/Resources/Reports/soe/.

Fang, W. et al. Increased contribution of biomass burning to haze events in Shanghai since China’s clean air actions. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 310 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Winter particulate pollution severity in North China driven by atmospheric teleconnections. Nat. Geosci. 15, 349–355 (2022).

Wang, P. et al. Severe air pollution events not avoided by reduced anthropogenic activities during COVID-19 outbreak. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 158, 104814 (2020).

Geng, G. et al. Drivers of PM2.5 air pollution deaths in China 2002–2017. Nat. Geosci. 14, 645–650 (2021).

Zhang, Q. et al. Drivers of improved PM2.5 air quality in China from 2013 to 2017. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 24463–24469 (2019).

Zhai, S. et al. Control of particulate nitrate air pollution in China. Nat. Geosci. 14, 389–395 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Decline in bulk deposition of air pollutants in China lags behind reductions in emissions. Nat. Geosci. 15, 190–195 (2022).

Ramanathan, V. & Carmichael, G. Global and regional climate changes due to black carbon. Nat. Geosci. 1, 221–227 (2008).

Bond, T. C. et al. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: a scientific assessment. J. Geophy. Res. Atmos. 118, 5380–4496 (2013).

Naik, V. et al. Short-lived climate forcers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds. Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Ding, A. J. et al. Enhanced haze pollution by black carbon in megacities in China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2873–2879 (2016).

Fuzzi, S. et al. Particulate matter, air quality and climate: lessons learned and future needs. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 8217–8299 (2015).

Lelieveld, J., Evans, J. S., Fnais, M., Giannadaki, D. & Pozzer, A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 525, 367–371 (2015).

New WHO Global air quality guidelines. WHO (accessed August 2024) https://www.who.int/news/item/22-09-2021-new-who-global-air-quality-guidelines-aim-to-save-millions-of-lives-from-air-pollution.

Shindell, D. et al. Simultaneously mitigating near-term climate change and improving human health and food security. Science 335, 183–189 (2012).

Ebenstein, A. et al. New evidence on the impact of sustained exposure to air pollution on life expectancy from China’s Huai River Policy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10384–10389 (2016).

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development https://sdgs.un.org/goals (United Nations).

Sheehan, P., Cheng, E., English, A. & Sun, F. China’s response to the air pollution shock. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 306–309 (2014).

Zhang, Q., He, K. B. & Huo, H. Cleaning China’s air. Nature 484, 161–162 (2012).

Stohl, A. et al. Evaluating the climate and air quality impacts of short-lived pollutants. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 10529–10566 (2015).

Lu, Z., Zhang, Q. & Streets, D. G. Sulfur dioxide and primary carbonaceous aerosol emission trends in China and India, 1996–2010. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 9839–9864 (2011).

Klimont, Z. et al. Global anthropogenic emissions of particulate matter including black carbon. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 8681–8723 (2017).

Zhao, Y. et al. Quantifying the uncertainties of a bottom-up emission inventory of anthropogenic atmospheric pollutants in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 4825–4841 (2011).

Wang, R. et al. Exposure to ambient black carbon derived from a unique inventory and high-resolution model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 2459–2463 (2014).

Eckhardt, S. et al. Current model capabilities for simulating black carbon and sulfate concentrations in the Arctic atmosphere: a multi-model evaluation using a comprehensive measurement data set. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 9413–9433 (2015).

Winiger, P. et al. Siberian Arctic black carbon sources constrained by model and observation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E1054–E1061 (2017).

Eckhardt, S. et al. Revised historical Northern Hemisphere black carbon emissions based on inverse modeling of ice core records. Nat. Comm. 14, 271 (2023).

Petzold, A. et al. Recommendations for reporting “black carbon” measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 8365–8379 (2013).

Andersson, A. et al. Regionally-varying combustion sources of the January 2013 severe haze events over eastern China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 2038–4496 (2015).

Fang, W. et al. Divergent evolution of carbonaceous aerosols during dispersal of East Asian haze. Sci. Rep. 7, 10422 (2017).

Fang, W. et al. Dual-isotope constraints on seasonally resolved source fingerprinting of black carbon aerosols in sites of the four emission hot spot regions of China. J. Geophy. Res. Atmos. 123, 11735–11747 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Fossil vs. non-fossil sources of fine carbonaceous aerosols in four Chinese cities during the extreme winter haze episode of 2013. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 1299–1312 (2015).

Liu, J. et al. Radiocarbon-derived source apportionment of fine carbonaceous aerosols before, during, and after the 2014 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in Beijing, China. J. Geophy. Res. Atmos. 121, 4177–4187 (2016).

An, J. et al. Emission inventory of air pollutants and chemical speciation for specific anthropogenic sources based on local measurements in the Yangtze River Delta region, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 2003–2025 (2021).

Huang, R.-J. et al. High secondary organic aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China. Nature 514, 218–222 (2014).

Szidat, S. Sources of Asian haze. Science 323, 470 (2009).

Zotter, P. et al. Diurnal cycle of fossil and nonfossil carbon using radiocarbon analyses during CalNex. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 119, 6818–6835 (2014).

Szidat, S. et al. Contributions of fossil fuel, biomass-burning, and biogenic emissions to carbonaceous aerosols in Zurich as traced by 14C. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 111, D07206 (2006).

van der Werf, G. R. et al. Global fire emissions estimates during 1997–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 697–720 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. The impact of meteorological changes from 2013 to 2017 on PM2.5 mass reduction in key regions in China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 62, 1885–1902 (2019).

Winiger, P. et al. Source apportionment of circum-Arctic atmospheric black carbon from isotopes and modeling. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau8052 (2019).

Evangeliou, N. et al. Wildfires in northern Eurasia affect the budget of black carbon in the Arctic—A 12-year retrospective synopsis (2002–2013). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 7587–7604 (2016).

Li, C. et al. India is overtaking China as the world’s largest emitter of anthropogenic sulfur dioxide. Sci. Rep. 7, 14304 (2017).

Rooney, B. et al. Impacts of household sources on air pollution at village and regional scales in India. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 7719–7742 (2019).

Chow, J. C. et al. Equivalence of elemental carbon by Thermal/Optical Reflectance and Transmittance with different temperature protocols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38, 4414–4422 (2004).

Graven, H. D., Guilderson, T. P. & Keeling, R. F. Observations of radiocarbon in CO2 at seven global sampling sites in the Scripps flask networks: analysis of spatial gradients and seasonal cycles. J. Geophy. Res. 117, D02302 (2012).

Pisso, I. et al. The Lagrangian particle dispersion model FLEXPART version 10.4. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 4955–4997 (2019).

Stohl, A. et al. Validation of the Lagrangian particle dispersion model FLEXPART against large-scale tracer experiment data. Atmos. Environ. 32, 4245–4264 (1998).

Stohl, A. et al. Technical note: the Lagrangian particle dispersion model FLEXPART version 6.2. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 5, 4739–4799 (2005).

Amann, M. et al. Cost-effective control of air quality and greenhouse gases in Europe: modeling and policy applications. Environ. Model. Softw. 26, 1489–1501 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Heli Wang, Yao Wang, Xuan Lin, Mengjiao Cui, Huanhuan Wang, Lei Peng, Jun Chen, Yepeng Yu and Liusi Sheng, for assistance during analysis and sampling. We gratefully acknowledge Roberta L. Hansman and scientists at NOSAMS Facility (Woods Hole, MA, USA) for measuring the 13C-14C samples. The research was funded by Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (Grant # 25ZR1401095 to W.F.). W.F. acknowledges the start-up funding from East China Normal University. N.E. and S.E. were supported and used cross-atmospheric research infrastructure services provided by ATMO-ACCESS (EU grant agreement No 101008004) to perform all FLEXPART model analyses. The computations/simulations/[SIMILAR] were performed on resources provided by Sigma2—the National Infrastructure for High Performance Computing and Data Storage in Norway. The authors also gratefully acknowledge ECMWF for permitting access to the meteorological data used for the model simulations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.F. designed the research, sampling campaign and experiments. H.L. was involved in the sampling at Tianjin and H.X. involved in the OCEC analysis discussion. W.F. analysed and interpreted data with discussion from N.E. and S.E. W.F. performed MC simulations and numerical simulations, while N.E. and S.E. were in charge of FEG simulations. W.F. wrote the paper and produced the figures with review from N.E. and S.E.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Rakesh K. Hooda and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alice Drinkwater. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, W., Evangeliou, N., Eckhardt, S. et al. Unprecedented shifts in aerosol pollution sources in China under a decade of clean air actions. Commun Earth Environ 6, 512 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02487-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02487-8