Abstract

Understanding crop migration to adapt to climate change is important to achieve food security and sustainable agriculture. Previous researches mainly focus on the impacts of climate change on crop yields and migration, but environmental feedback has been overlooked. Here we analyze the rice migration and its impact on water use in Sanjiang Plain, Northeast China—which experienced considerable poleward expansion and climate warming. From 2000 to 2020, rice cultivation expanded northeast by 2.19 million hectares, increasing irrigation demand by 6.36 billion tonnes. Rice expansion contributed 122.18% to the abrupt irrigation increase, while the direct impact of climate change resulted in a −22.18% increase due to decreased evapotranspiration and increased precipitation. Such phenomenal rice expansion is considerably associated with the decline of groundwater levels by an average of 4.79 meters. Our findings highlight the urgent need to make integrated strategies balancing crop migration to climate change and water resource conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding climate adaptation through crop migration is essential to both food and nutrition security and agricultural sustainability1,2. The agricultural system is one of the most sensitive sectors to climate change. The impact of climate change is not only on crop yields but also on crop geographic distributions3,4,5,6. Crop migration, as a cost-effective strategy, adapts to climate change through shifts in the geographic distribution of crops from one area to another regionally that will lead to crop switches, expansion, abandonment, and changes in harvesting frequency locally2. Continuous climate warming opens new climatic suitable areas for crop cultivation7, which helps eliminate damages of climate change on crop yields and thus ensures food security8,9. Inversely, crop migration creates positive or negative environmental externalities on water consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and biodiversity losses, which are not yet well documented. For instance, the expansion of rainfed cropland transformed from forest and grassland changes the landscape and raises groundwater levels by declining rooting depths and evapotranspiration in South American plains10. The rapid rice expansion in Africa contributes 7% of the current global increment of methane emissions11. Therefore, understanding crop migration and its potential feedback to local and global environments is vital to guide policymakers and practitioners in adapting to climate change sustainably.

Irrigation plays an essential role in crop migration to adapt to climate change by increasing water accessibility. Irrigation expansion is an important driver of rainfed crop migration because the addition of irrigation to previously rainfed crop areas alters the global geographic distribution of rainfed crops and provides more potential for crop switches to high-water demand crops2. To date, more than 40% of global crop production is fed by irrigation12. Additionally, irrigation can facilitate crop migration in semi-arid and arid regions where crops can obtain enough thermal input but suffer from water deficits. More than 52% of global irrigation expansion happened in water-stressed regions in the twenty-first century12. Approximately 43% of global irrigation consumption depends on groundwater13. Such mismatches between irrigation demands and water resource endowment and intensive irrigation degraded water flows and depleted local groundwater in many important agricultural areas of the world, including but not limited to North China Plain, High Plains and Central Valley of America, and the Indo-Gangetic Basin14,15,16,17,18. However, quantifying the relationship between crop migration and irrigation consumption and groundwater levels is still in its infancy.

Rice expansion to adapt to climate change in Sanjiang Plain in Northeast China epitomizes the feedback loop between crop migration and environmental consequences such as irrigation consumption (Fig. 1). Sanjiang Plain is located in the high latitude region and is one of the marginalized and ecologically vulnerable areas, which experiences warmer climate19. Crops are cultivated once a year and rice is one of the predominant crops now. The climate warming expanded climatically suitable areas for rice cultivation and thus the paddy rice frontier migrated by 88 km poleward from 1984 to 2013 in Sanjiang Plain20. Rice cultivation in China has shifted northward considerably marked by an area increase in northern China and a decrease in southern China, which exacerbates the already uneven distribution of water endowment in China with more in the South and less in the North15,21. A substantial portion of this northward expansion occurred in the Sanjiang Plain, where rice is mainly transformed from dryland primarily from rainfed dryland, as well as unused land and forests19,21,22,23. Such dramatic rice expansion makes Sanjiang Plain a new rice breadbasket in China. It also dramatically increases irrigation water consumption and leads to unsustainable water use such as accelerating local groundwater exploitation because of the long-lasting flooding needed during rice cultivation24.

a Land use and land cover of Sanjiang Plain in 2020 (http://www.resdc.cn) and locations of groundwater observations. b The ratio of irrigation water use of rice fields to the total water use of prefectures in the Sanjiang Plain in 201346.

In this research, we integrate long-term satellite rice maps and in situ groundwater observations in farmland to assess the impact of rice expansion on groundwater levels in the frontiers of rice cultivation in the high-latitude region of the Sanjiang Plain, Northeast China. Our objectives are to track the trajectory of rice expansion in Sanjiang Plain and detect its cascading effect on local groundwater consumption from 2000 to 2020. Specifically, we (i) measure the patterns of rice expansion from 2000 to 2020 based on annual rice maps and FishNet analysis; (ii) evaluate the dynamics of water requirements of rice cultivation including blue water (irrigation water) and green water requirements employing a process-based water requirement model since actual water consumption data are unavailable; (iii) quantify the contributions of climate change and rice expansion to irrigation water requirement changes using the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index model; (iv) evaluate the impact of rice expansion on groundwater through a statistic method.

Results

Rice area has obviously increased and become highly centralized in the 21st century

The rice area in Sanjiang Plain increased more than three times from 2000 to 2020. The trend of rice area sharply increased before 2016 with a rate of 0.17 million ha year−1. The trend of rice area change is reversed after 2016 with a rate of −0.08 million ha year−1 (Fig. 2a).

a The rice area of Sanjiang Plain from 2000 to 2020. The dashed line is the trend of rice area changes. b, c The marginal line graphs show the mean slope of rice area changes along with longitude and latitude based on a 5 × 5 km fishnet. d The slope of the rice area changes based on a 5 × 5 km fishnet.

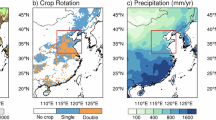

Moreover, the change in rice area is spatially heterogeneous. Regions in higher latitudes experienced faster rice expansion and centralized in northern and southeastern regions of Sanjiang Plain currently (Figs. 2–3). Area under rice cultivation for more than 10 years counts for 66% and more than 20 years counts for 11% (Fig. 3a, b). 43% of the rice cultivation started from 2009 to 2012 and is located in the north (Fig. 3c). The area for rice production currently covers most of the northern and southeastern regions of Sanjiang Plain (Fig. 3d).

Volumetric irrigation requirement for rice cultivation increased considerably while the depth of irrigation requirement decreased

The volumetric water requirement of rice is determined by both the depth of water requirement and the rice area. The volumes of rice water requirement for all categories considerably increased in Sanjiang Plain over the past two decades though the depth of total water and blue water requirement of rice considerably decreased due to climate change. The depth of total water requirement for rice evapotranspiration in 78% of counties in the northwest experienced a significant decrease between 2000 and 2020 in Sanjiang Plain (Fig. 4a). The green water requirement of rice has an obvious increase because of the increment of precipitation from 2000 to 2020. 43% of counties in the west showed significant and higher increment rates in the depth of rice green water requirement (Fig. 4b). The blue water requirement depth of rice in most of Sanjing Plain obviously decreased, which is attributed to less water requirement for rice to avoid water stress and simultaneously more efficient precipitation to be available (Fig. 4c). However, the volumetric water requirement for rice production (tonne year-1) in most of Sanjiang Plain starkly increased by including rice area from 2000 and 2020. Counties with a higher increment of water requirement are concentrated in the northeast of Sanjiang Plain due to rice expansion, which indicates rice cultivation expanded into places with less depth of irrigation decrement and precipitation increment (Fig. 4d–g).

The first row is the slope of depth of water requirement changes of rice production for (a) total water requirement (TWR), b green water requirement (GWR), and (c) blue water requirement (BWR). The second row is the slope of volumetric water requirement changes for rice production (that is depth of water requirement multiplied by rice area) for (d) total water requirement (TWV), e green water requirement (GWV), and (f) blue water requirement (BWV). g The slope of area change under rice cultivation. Counties with bold boundaries mean the slope of water requirement or rice area change is significant at the level of 0.05.

Rice expansion mainly contributed to the volumetric irrigation requirement changes instead of climate change

The volumetric blue water requirement for rice production in Sanjiang Plain rose till 2017 and came down afterward (Fig. 5a). The total volume of blue water requirement for rice cultivation in Sanjiang Plain increased at a rate of 0.55 billion tonnes per year before 2017, and decreased at a rate of 1.36 billion tonnes per year after.

a The trends of volumetric blue water requirement change of rice from 2000 to 2020 using a piecewise regression model with one turning point. Slope1 and slope2 are the slopes before and after the turning point, respectively. ** means the trends are significant at the level of 0.01. b The relative contribution of depth changes of total water requirement (TWR), green water requirement (GWR), and rice area to the volumetric blue water requirement changes during two periods based on the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index. Grey boxes show the volumetric blue water requirement of rice cultivation in 2000, 2017, and 2020. Red rectangles represent the direct contributions of climate change and also indicate depth changes of blue water requirement.

The volume of blue water requirement for rice cultivation increased by 10.38 billion tonnes or over 358.13% in the 2000–2017 timeframe, with rice area expansion contributing to 98.56%, and climate change contributing to 1.44%. Thereinto, the increased depth of rice total water for evapotranspiration contributed to 2.85% while the increased depth of precipitation eliminated the depth increment of blue water requirement by 1.42% (Fig. 5b).

The volume of blue water requirement for rice cultivation decreased by 4.02 billion tonnes (by 30.26%) in the 2017–2020 timeframe, with the rice area decrease contributing to 24%, and climate change contributing to 76%. Thereinto, the decreased depth of evapotranspiration and increased depth of precipitation contributed 66.55% and 9.45%, respectively (Fig. 5b).

Rice expansion is significantly associated with the decline of groundwater levels

We show our results as trends in elevation to groundwater, which means that the negative slope represents groundwater levels becoming deeper over time and vice versa. We find that groundwater levels in Sanjiang Plain become deeper over the past two decades. The average groundwater elevation of all wells falls from 48.63 m in 2000 to 43.84 m in 2017 by −4.79 m with a speed of −0.29 m per year (Fig. 6). Moreover, the reduction of groundwater elevation varies across wells from 1.20 m to 7.8 m from 2000 to 2017. Rice area expansion and the increased irrigation for rice have strong and significant negative correlations with the changes in groundwater elevation in Sanjiang Plain (Fig. 7, Supplementary Fig. 1). Places with more rice expansion and rice cultivation tend to have more reduction in groundwater levels.

Box plots show the groundwater elevation for all wells each year, including the minimum, first quartile, median (solid line), third quartile, and maximum values. Black points show the mean values of groundwater elevation of the well for each year. The Red dashed line means the trend of mean groundwater elevation of wells with years using a regression model. ** means the trend of groundwater elevation is significant at the level of 0.01.

Discussion

Rice expands dramatically in Sanjiang Plain, Northeast China to adapt to climate change and to increase food production in China. The temperature increased at the rate of 0.2 °C per decade since 2000, which improves rice suitability since climate warming not only provides more thermal for rice growth but also reduces the risks of cold stress and even chilling damages25. The north frontier of rice cultivation migrated poleward obviously and areas under rice cultivation expanded by 2.19 million hectares in Sanjiang Plain to adapt to climate warming. Aligning with a rice yield increase by 0.64 tonne ha-1 associated with socioeconomic improvements such as fertilizer inputs and irrigation construction, rice expansion led to a rice production increase of 11.73 million tonnes. This contributed to a 33% increment of China’s rice production from 2000 to 2020 (https://www.stats.gov.cn/). With continuous climate change in the future, Sanjiang Plain in Northeast China will get warmer and wetter, which will increase rice suitability. Therefore, future climate change will provide more potential areas for rice expansion and rice production.

Nevertheless, the abrupt area expansion and centralization of rice cultivation in Sanjiang Plain not only transgresses the boundary of water-sustainable consumption but also leads to cascading effects on the environment. Our results show that in the past two decades, total volumetric water requirement of rice cultivation increased by 10.74 billion tonnes, including 6.36 billion tonnes of irrigation water requirement increment, which is mainly due to rice area expansion instead of direct impacts of climate change on rice fields evapotranspiration and precipitation (Fig. 6). Such dramatic irrigation water requirement change has a considerable impact on the overexploitation of groundwater and decline of groundwater levels by 4.79 m over the last two decades. In Sanjiang Plain, irrigation heavily relies on groundwater pumping, with a maximum ratio of 72% in northeast regions where rice is highly centralized (Figs. 1b, 7). The overexploitation of groundwater will bring negative environmental repercussions that have great impacts on the water resources and local environment. For instance, more energy will be used to pump water from deeper groundwater levels, which will increase greenhouse gas emissions in rice cultivation since more energy will be needed to overcome the gravity of water from deeper aquifers26.

Rational and holistic strategies for sustainable crop migration to climate change should be considered by policymakers and practitioners in the future. With continuous climate change, future rice distribution could expand to still higher latitude regions. But it could also increase the risks of depletion of aquifers. Efforts to reasonably control rice areas in water-stress regions to adapt to climate change are urgent to avoid unlimited rice expansion in the future. Additionally, previous studies demonstrated crop redistribution and crop switches are promising ways to reduce irrigation consumption without compromising food production in China, the United States, India, and even the globe14,16,27,28. Crop migration to climate change should be incentivized to optimize and relocate to regions with abundant natural endowments. For instance, more policy incentives should be made for decentralized rice cultivation in Northeast China with more water stress to regions with abundant water resources such as South China.

Moreover, agricultural policies should be directed to stimulate water-saving techniques, and cropland consolidation to avoid natural resource degradation. For instance, it is necessary to upgrade the priority of sustainable water consumption for regions suffering from water stress and groundwater overexploitation like Sanjiang Plain in national cropland consolidation programs such as the Construction of High-standard Farmland in China29. On the one hand, well construction of canal networks is not only beneficial to increase the accessibility of irrigation to surface water sources (such as rivers, reservoirs, streams, etc.) and reduce the dependence of irrigation on groundwater but also to improve irrigation efficiency by reducing the waste during water transfer. On the other hand, applying water-saving technology and agronomic strategies can also provide a promising way to reduce the depth of water consumption. For example, alternate wetting and drying irrigation for rice cultivation can reduce irrigation water consumption per hectare by 23–34% without compromising rice yield in Northeast China30.

Lessons from our study are also valuable for other regions that experience or will experience crop migration and expansion to adapt to climate change. First, building a comprehensive long-term spatial monitoring network on crop cultivation and local environmental conditions is essential to understanding the dynamics of crop migration and effectively forecasting its potential risks and opportunities for the local environment such as water sustainability in North China and Indus basin, biodiversity changes in Brazil, and etc. Second, our findings underscore the important insight of accounting for the environmental impacts of crop migration to climate change for regions that will experience crop migration in the future. For instance, with climate warming, 270 million hectares of wilderness particularly high-latitude wilderness in the northern hemisphere of the world will become suitable for agriculture in the next 40 years31. While this potential agricultural expansion will provide more opportunities for ensuring food security, this irreversible change will also threaten the local biodiversity, carbon storage, and soil quality. It is essential to integrate environmental costs into agricultural expansion evaluation.

Materials and Methods

Data sources

Annual rice distribution from 2000 to 2020 in Sanjiang Plain is a subset of Asian monsoon regions obtained from Han et al.32, which is produced at 500-m resolution using an improved rice model based on multi-resource remote sensing data.

Groundwater elevation (meters above the sea level) observations are the most recently available data at well stations at the aquifer level from 2000 to 2017 collected from state farms in Sanjiang Plain, Northeast China33.

Rice water requirement is simulated through the pixel-based process model fed with daily reference evapotranspiration datasets, daily precipitation datasets, and soil datasets. To calculate rice water requirement from 2000 to 2020, daily reference evapotranspiration datasets from 1999 to 2020 were obtained from Singer et al.34, which were calculated using the FAO’s Penman-Monteith equation based on hourly ERA5-Land reanalysis meteorological variables datasets. Daily precipitation datasets are collected from The Climate Hazards Group Infrared Precipitation with Stations dataset with a spatial resolution of 0.05° × 0.05° from 1999 to 202035. Maximum soil available water capacity and maximum infiltration rate are from the ISRIC-WISE dataset36 and groundwater resources and recharge dataset37.

Rice mapping method

The paddy rice maps in Asian monsoon regions from 2000 to 2020 are produced based on an improved method32. The basic theory of the improved method is identifying the flooding signals of paddy rice in the transplanting phase as paddy rice has a few weeks of flood/open-canopy phase after transplanting into soil and water mixed fields while other crops don’t. In the flood/open-canopy phase, the land surface water index (LSWI) of paddy rice is temporally higher than the enhanced vegetation index (EVI). Firstly, the non-cropland pixels and unsuitable pixels for rice are removed based on the integrated multiple land cover products, topography, and climate. Then, the flood/open-canopy phase is defined according to the night land surface temperature higher than 5 °C. Finally, paddy rice is identified using multiple threshold methods, such as LSWI + 0.05 ≥ EVI in transplanting phase to capture flooding signals, and EVI > 0.4 within 16 days of transplanting phase, and frequency of EVI less than 0.3 within 80 days of transplanting phase. We re-validated the accuracy of this rice map product in Sanjiang Plain with ground labels from 2011 to 2019 and statistical rice area from 2000 to 2020. It shows that the overall accuracy based on ground labels is greater than 86% and the R square compared to the statistical rice area is 0.99 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

A pixel-based process water requirement model

Since actual water consumption data for rice production in the study area are not available, the rice water requirement, a common alternative, is used to estimate the water demand for rice growth. We employ a pixel-based process model to calculate the water requirement for rice cultivation, which represents the depth of water needed to compensate for losses from evapotranspiration. The pixel-based process model is based on the theory of daily soil water balance for each grid and divides rice water requirement (mm year−1) into blue water requirement supported by irrigation and green water requirement supported by precipitation38 (Eqs. 1–7). For each grid, the potential evapotranspiration (PET) for each day is the total water requirement (TWR) of the well-watered rice calculated by multiplying reference evapotranspiration (\({{ET}}_{0}\)) and crop coefficients for rice \(({k}_{c})\) (Eq. 3). The actual evapotranspiration \(({{AET}}_{i,t})\) of rice that is the green water requirement (GWR) is the water requirement when rice growth suffers from water stress by multiplying \({{PET}}_{i,t}\) (Eq. 2) and the water stress coefficient \(({k}_{s})\) (Eq. 4). The blue water requirement (BWR) is the depth of irrigation water required (\({I}_{t}\)) (Eq. 1) in the absence of sufficient precipitation calculated as the difference between the unstressed actual evapotranspiration \({{PET}}_{i,t}\) and stressed actual evapotranspiration \({{AET}}_{i,t}\). We then take a summation of the daily green and blue water requirement across the growing season of rice from May to September for each year from 2000 to 2020.

The volumetric water requirement is the amount of water needed for rice cultivation (tonne year−1), which is calculated by multiplying the depth of water requirement and rice area from 2000 to 2020.

The daily soil water balance for each grid is:

where \({S}_{t-1}\) means the water content at the end of the previous step. \(\Delta t\) refers to the time steps of one day. \({P}_{{eff},t}\) is the effective precipitation actually absorbed in the soil that 5% of the precipitation is assumed as surface runoff \({R}_{t}\) 38. \({D}_{t}\) represents the deep percolation below the root zone, which happens when soil moisture exceeds field capacity38 (Eq. 7).

where \({TAW}\) is the total available soil water capacity in the root zone (mm). \({TAWC}\) means the total available water capacity of the soil (mm m−1). \({rd}\) means the depth of rice root (m). The depletion fraction \({p}_{t}\) is the fraction of TAW that rice can uptake from the root zone without suffering water stress. \({p}_{{std}}\) is the value of depletion fraction for rice for PET of around 5 mm day−1 obtained from Allan et al.39 and Siebert et al.40. \({F}_{\max }\) is the soil-specific maximum infiltration rate depending (mm day−1).

Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI)

The volumetric blue water requirement of rice is the volume of irrigation water requirement to avoid water stress from evapotranspiration in the absence of sufficient rainfall for the area under rice cultivation (Eq. 8). It is determined by both the depth of blue water requirement directly affected by climate change and the rice area determined by practitioners (Eq. 9). We employ the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index model (LMDI) to diagnose the driving force of climate change and human direct impacts. The change of volumetric rice blue water requirement in each period is decomposed into the depth of rice water requirement and area under rice cultivation, and their contributions are calculated using the logarithmic average weight (Eq. 10). The LMDI has no residual errors and is widely used in energy, carbon emission, water use, and recently crop production41,42,43,44. Before applying the LMDI, we detect different change periods of rice blue water requirement volume with different trends using the piecewise regression model45.

where the \({{BW}V}_{t}\) (\({{BWV}}_{0}\)) is the volumetric of blue water requirement in year t (the base year), which is the difference between the volume of total water requirement (TWV) and green water requirement (GWV). The \({{BW}R}_{{t}}\) (\({{BWR}}_{0}\)) is the depth of blue water requirement in year t (the base year), which is equal to the difference between the depth of total water requirement (TWR) and green water requirement (GWR). The \({{area}}_{t}\) (\({{area}}_{0}\)) means the rice area in the year of t (the base year). \(L\left({TWV}_{t},{TWV}_{0}\right)\) and \(L\left({GWV}_{t},{GWV}_{0}\right)\) represent the logarithmic mean of the volumetric total water requirement and green water requirement in year t and the base year, respectively.

Data availability

Annual rice distribution maps32 are collected from https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5555721. Groundwater level observation data are collected from state farms in Sanjiang Plain, Northeast China33, which are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15690243. Daily reference evapotranspiration datasets34 are obtained from https://doi.org/10.5523/bris.qb8ujazzda0s2aykkv0oq0ctp. Daily precipitation datasets are collected from The Climate Hazards Group Infrared Precipitation with Stations datasets (https://www.chc.ucsb.edu/data/chirps). Maximum soil available water capacity and maximum infiltration rate are from the ISRIC-WISE dataset36 at https://data.isric.org/geonetwork/srv/eng/catalog.search#/metadata/dc7b283a-8f19-45e1-aaed-e9bd515119bc and groundwater resources and recharge dataset37 at https://www.whymap.org/whymap/EN/Maps_Data/Gwr/gwr_node_en.html.

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Gu, W. et al. Climate adaptation through crop migration requires a nexus perspective for environmental sustainability in the North China Plain. Nat. Food 5, 569–580 (2024).

Sloat, L. L. et al. Climate adaptation by crop migration. Nat. Commun. 11, 1243 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Chinese Rice Production Area Adaptations to Climate Changes, 1949–2010. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 2032–2037 (2015).

Olmstead, A. L. & Rhode, P. W. Adapting North American wheat production to climatic challenges, 1839–2009. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108, 480–485 (2011).

Rezaei, E. E. et al. Climate change impacts on crop yields. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 831–846 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Emergent constraint on crop yield response to warmer temperature from field experiments. Nat. Sustain. 3, 908–916 (2020).

Iizumi, T. & Ramankutty, N. How do weather and climate influence cropping area and intensity? Glob. Food Sec. 4, 46–50 (2015).

Franke, J. A. et al. Agricultural breadbaskets shift poleward given adaptive farmer behavior under climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 167–181 (2022).

Zaveri, E., Russ, J. & Damania, R. Rainfall anomalies are a significant driver of cropland expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 10225–10233 (2020).

Houspanossian, J. et al. Agricultural expansion raises groundwater and increases flooding in the South American plains. Science 380, 1344–1348 (2023).

Chen, Z., Balasus, N., Lin, H., Nesser, H. & Jacob, D. J. African rice cultivation linked to rising methane. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 148–151 (2024).

Mehta, P. et al. Half of twenty-first century global irrigation expansion has been in water-stressed regions. Nat. Water 2, 254–261 (2024).

Siebert, S. et al. Groundwater use for irrigation – a global inventory. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1863–1880 (2010).

Chakraborti, R. et al. Crop switching for water sustainability in India’s food bowl yields co-benefits for food security and farmers’ profits. Nat. Water 1, 864–878 (2023).

Qi, X. et al. Rising agricultural water scarcity in China is driven by expansion of irrigated cropland in water scarce regions. One Earth 5, 1139–1152 (2022).

Richter, B. D. et al. Alleviating water scarcity by optimizing crop mixes. Nat. Water 1, 1035–1047 (2023).

Rosa, L. Adapting agriculture to climate change via sustainable irrigation: biophysical potentials and feedbacks. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 063008 (2022).

Scanlon, B. R. et al. Groundwater depletion and sustainability of irrigation in the US High Plains and Central Valley. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109, 9320–9325 (2012).

Huang, P. et al. Projected high-resolution ET0 spatiotemporal variation under future climate change and paddy area expansion in the Sanjiang Plain, Northeast China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 50, 101574 (2023).

Liang, S. et al. Climate-mediated dynamics of the northern limit of paddy rice in China. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 064008 (2021).

Zhang, G. et al. Spatiotemporal patterns of paddy rice croplands in China and India from 2000 to 2015. Sci. Total Environ. 579, 82–92 (2017).

Liu, D., Chen, W. & Li, L. Disentangling the relative effects of climate change and anthropogenic activities on paddy expansion in the northern Sanjiang Plain of China. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110543 (2023).

Pan, T. et al. Large-scale rain-fed to paddy farmland conversion modified land-surface thermal properties in Cold China. Sci. Total Environ. 722, 137917 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of water supply–demand patterns under large-scale paddy expansion: Implications for regional sustainable water resource management. Agric. Water Manag. 285, 108388 (2023).

Pan, T. et al. A large-scale shift of cropland structure profoundly affects grain production in the cold region of China. J. Clean. Prod. 307, 127300 (2021).

Rao, N. D., Poblete-Cazenave, M., Bhalerao, R., Davis, K. F. & Parkinson, S. Spatial analysis of energy use and GHG emissions from cereal production in India. Sci. Total Environ. 654, 841–849 (2019).

Davis, K. F., Rulli, M. C., Seveso, A. & D’Odorico, P. Increased food production and reduced water use through optimized crop distribution. Nat. Geosci. 10, 919–924 (2017).

Xie, W. et al. Crop switching can enhance environmental sustainability and farmer incomes in China. Nature 616, 300–305 (2023).

Liu, H. & Zhang, W. Spatial and temporal variation and convergence in the efficiency of high-standard farmland construction: Evidence in China. J. Clean. Prod. 452, 142200 (2024).

Tian, Z. et al. Searching for “Win-Win” solutions for food-water-GHG emissions tradeoffs across irrigation regimes of paddy rice in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 166, 105360 (2021).

Gardner, A. S., Trew, B. T., Maclean, I. M. D., Sharma, M. D. & Gaston, K. J. Wilderness areas under threat from global redistribution of agriculture. Curr. Biol. 33, 4721–4726.e2 (2023).

Han, J. et al. Annual paddy rice planting area and cropping intensity datasets and their dynamics in the Asian monsoon region from 2000 to 2020. Agric. Syst. 200, 103437 (2022).

Liu, A., Sha, N. & Cheng, C. Groundwater dynamics in catchment of Jiansanjiang in Sanjiang Plain. J. Irrig. Drain. 39, 96–101 (2020).

Singer, M. B. et al. Hourly potential evapotranspiration at 0.1° resolution for the global land surface from 1981-present. Sci. Data 8, 224 (2021).

Funk, C. et al. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations—a new environmental record for monitoring extremes. Sci. Data 2, 150066 (2015).

Batjes, N. H. ISRIC-WISE derived soil properties on a 5 by 5 arc-minutes global grid (ver. 1.2). 56 (2012).

Sustaining Groundwater Resources: A Critical Element in the Global Water Crisis. (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2011).

Chiarelli, D. D. et al. The green and blue crop water requirement WATNEEDS model and its global gridded outputs. Sci. Data 7, 273 (2020).

Allan, R., Pereira, L. & Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration-Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements-FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 56. vol. 56 (1998).

Siebert, S. & Döll, P. Quantifying blue and green virtual water contents in global crop production as well as potential production losses without irrigation. J. Hydrol. 384, 198–217 (2010).

Ang, B. W. The LMDI approach to decomposition analysis: a practical guide. Energy Policy 33, 867–871 (2005).

Cansino, J. M., Román, R. & Ordóñez, M. Main drivers of changes in CO2 emissions in the Spanish economy: A structural decomposition analysis. Energy Policy 89, 150–159 (2016).

Xu, J. et al. Double cropping and cropland expansion boost grain production in Brazil. Nat. Food 2, 264–273 (2021).

Zhao, C. & Chen, B. Driving Force Analysis of the Agricultural Water Footprint in China Based on the LMDI Method. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 12723–12731 (2014).

Toms, J. D. & Lesperance, M. L. Piecewise Regression: A Tool for Identifying Ecological Thresholds. Ecology 84, 2034–2041 (2003).

Zhou, F. et al. Deceleration of China’s human water use and its key drivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 7702–7711 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD2001105), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42401117), the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project of the Chinese Academy of Agriculture Sciences, and the Guangzhou Construction Group Co., Ltd ([2024]-KJ0003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.F.L., L.Z.Y., H.J.T., and P.Y. conceptualized and designed the research. S.F.L., W.P.L., and L.X. performed the research and conducted analyses. S.F.L. drafted the first version of the manuscript. S.F.L., M.L., L.Z.Y., Y.L., Z.H.L., Y.Z., and P.Y. reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Wouter Smolenaars and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Mengjie Wang. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, S., Liu, W., Lu, M. et al. Climate adaptation through rice northward expansion aggravated groundwater overexploitation in Northeast China. Commun Earth Environ 6, 516 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02504-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02504-w