Abstract

Perfluoroalkyl acids have been widely used during the last fifty years in a myriad of industrial and consumer applications, and are a paradigm of persistent “forever chemicals”. Earlier studies suggested a limited occurrence in the Southern Ocean as a consequence of the Antarctic circumpolar current preventing their oceanic transport southwards. Here we show perfluoroalkyl acids in the Bransfield Strait and Bellingshausen Sea (west of Antarctic Peninsula) at concentrations of comparable magnitude to those measured in the North Atlantic, a region impacted by historical sources. Atmospheric wet deposition of perfluoroalkyl acids previously aerosolized by sea-spray arises as the perfluoroalkyl acids source to Antarctica. The prevailing marine and atmospheric circulation in the region encapsulate these chemicals in the Antarctic region once these have crossed the Antarctic divergence. This work underscores the importance of persistence driving chemical’s environmental risk, and raises concern on the impact of the larger pool of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a large group of synthetic organic chemicals widely used in the industry, household consumer products, and various other applications1,2,3,4,5. Among PFAS, some perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) have received increasing attention. PFAAs are widely distributed in tropical and subtropical oceans6,7,8,9, and are extremely persistent in the environment4. PFAAs have been reported in the Arctic9,10, and Antarctica11,12,13,14,15, but with few reports for PFAAs in open waters from the Southern Ocean.

Oceans are a major reservoir of PFAAs16,17, and long-range transport by oceanic currents has generally been assumed to drive their global occurrence and long-term trends. This contrasts with the successive volatilization and atmospheric deposition, a process known as grasshopping, which is the dominant transport mechanism for semi-volatile persistent organic pollutants (POPs), such as legacy polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), hexachlorocyclohexanes (HCHs), or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)18,19,20. Known oceanic sinks of perfluoroalkyl sulfonates (PFSAs) and perfluoroalkyl carboxylates (PFCAs) in the marine environment are vertical eddy diffusion21, deep water formation21,22, and settling of particle bound PFAAs (known as biological pump)11,16,23. However, despite these sinks, their persistence is estimated to range between a decade and centuries in the marine environment16,23,24.

Disparate PFAAs concentrations in coastal and open Antarctic waters have been reported11,25,26, ranging from high concentrations close to the anthropically impacted King George Island14, to extremely low levels in early reports of PFAAs in the open Southern Ocean10,25,27. Research stations account for a point source of PFAAs, but limited to the perimeter of the facilities12,28. Generally, it is thought that the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) acts as a barrier for the north-south transport of PFAAs by oceanic currents15,29. Neutral PFAS, precursors of PFAAs, have been reported in the Southern Ocean’s atmosphere around the Antarctic Peninsula with a potential role as a source of PFAAs to this region30,31,32. Only recently, the potential role of wet deposition of sea spray aerosol-bound PFAAs has been identified as an additional mechanism accounting for a source of PFAAs in the Southern Shetland’s coastal waters11,12,33. Nevertheless, the relevance of these atmospheric sources to the larger Antarctic Peninsula region remains unquantified, as well as how the current occurrence of PFAAs in the open Southern Ocean compares with that measured two decades ago, as well with the occurrence in other oceanic regions.

The main goals of this work were i) to provide measurements of PFCAs and PFSAs in the Atlantic Ocean, Bransfield Strait and Bellingshausen Sea, obtained using the same sampling and analytical procedures, thus allowing a comparison of concentrations in seawater from 37°N to 71°S, covering latitudes in the Southern Ocean never sampled before for PFAAs, (ii) to assess the PFAAs depth distribution, and iii) to elucidate the processes driving the long-term occurrence and accumulation of PFAAs in Antarctic waters within the framework of the general atmospheric and oceanic patterns in the Atlantic-Southern Ocean continuum.

Results and discussion

Occurrence of PFCAs and PFSAs in the Atlantic Ocean

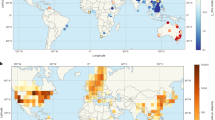

Seventeen of the nineteen targeted PFAAs were detected in seawater (see list of sampling stations in Supplementary Table S1 and chemicals and acronyms in Supplementary Table S2). At 5 m depth in the Atlantic Ocean, ∑17PFAAs concentrations ranged from 36.0 to 810 pg L−1 with an average of 204 pg L−1. ∑6PFSAs (PFBS, PFHxS, PFECHS, PFOS, PFDS, PFDoDS) ranged from 3.0 to 38.2 pg L−1, and ∑11PFCAs (PFPeA, PFHpA, PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFUnDA, PFDoDA, PFTrDA, PFTeDA, PFHxDA, PFODA) ranged from 15.0 to 801 pg L−1. The highest concentrations were found off-shore Brazil and Argentina (21°S and 43°S), with 467 and 810 pg L−1 of ∑17PFAAs, respectively (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S3).

PFAAs concentrations at 5 m depth (surface) showed a north-to-south decreasing trend from 40oN to the Equator (0o), and concentrations were high but variable off-shore Argentina between 21°S and 46°S. The range of concentrations reported here is consistent, but in the lower end of those previously reported for the Atlantic Ocean8,10,34,35, but higher than those reported for the open Pacific and Indian oceans8,36. The measured concentrations in the Atlantic Ocean showed no evidence of a long-term increasing concentration of PFAAs. A compilation of oceanic PFAAs measures done recently17 reported PFCAs medians in the North Atlantic for the periods 2000–2009 and 2010–2014 of 70 pg L−1 and 264 pg L−1, respectively, within the range of the PFCA concentrations reported here (similar also for PFCAs in the south Atlantic). Conversely, PFSA concentrations in the North Atlantic had medians of 49 pg L−1 and 128 pg L−1 for the periods 2000-2009 and 2010-2014, respectively. In the South Atlantic, PFSAs had medians of 31.0 pg L−1, 365 pg L−1, and 387 pg L−1 for the periods 2000–2009, 2010–2014, 2015–2020, respectively, which are above the range of PFSAs measured here for the South Atlantic. Such comparison should be taken with caution due to the high temporal and spatial variability of reported PFSA concentrations, especially those of PFOS. For example, during the Malaspina circumnavigation cruise in 2010, ∑21PFAS at surface in the Atlantic ranged from 131 to 10,900 pg L−1, with the highest concentrations off-shore Brazil8, consistent with the high values reported here in terms of geographical distribution, even though with significant lower maximum concentration in 2021 than in 2010. At least for PFOS, the overall trend seems to show a decrease of concentrations in the Atlantic Ocean, which were low for the measurements done here. Such decrease could mirror the decreased PFOS primary sources due to its inclusion into the Stockholm Convention, combined with a larger sorption of PFOS to phytoplankton than that of PFOA, thus leading to a larger sink due to the biological pump23, or to a potential microbial desulfurization of PFOS, a mechanism suggested elsewhere37, but which oceanic relevance cannot be assessed here.

At the Atlantic Ocean stations, the deep chlorophyll maximum (DCM) depth ranged from 50 to 145 m. ∑17PFAA concentrations at the DCM showed a mean of 143.2 pg L−1 (ranging 48.7–444.0 pg L−1) with ∑6PFSAs and ∑11PFCAs ranging from 0.7 to 53.2 pg L−1, and from 38.2 to 390.7 pg L−1, respectively (Supplementary Table S3). The concentrations of ∑17PFAAs at the DCM were significantly correlated with those at surface (R2 = 0.77, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Concentrations of most PFAAs were not significantly different between surface and the DCM, while some of those with lower contributions to ∑17PFAAs (PFDoDA, PFDA and PFOS), showed higher concentrations (about 10 pg L−1 higher) at surface than at the DCM (p-value < 0.05). A surface-enrichment depth depletion profile is consistent with chemicals that are introduced at surface and efficiently transported downward by the biological pump. This would be the case of PFNA and PFDA, which have a longer perfluoroalkyl chain, higher hydrophobicity, and higher tendency to accumulate in sinking particles (biological pump). Such vertical settling may deplete their concentrations in the DCM. On the contrary, for other PFAAs, the biological pump may be not effective enough to deplete the photic zone concentrations of PFAAs. This is consistent with previous patterns of PFAAs occurrences at surface and the DCM for the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans16.

At six stations from the Atlantic Ocean, additional measurements were performed along the vertical profile when sea conditions allowed them. The sampled depths were the depth with a 1% photosynthetic active radiation (1% PAR), the minimum of oxygen depth (MOx), and 2000 m depth. Such coverage of PFAAs in the meso-pelagic and deep ocean provides further information on the extent of the distribution of PFAS in the ocean and the biogeochemical controls on their transport and sinks.

The vertical profiles showed distinct trends (Supplementary Table S4). At 37°N, a surface enrichment depth depletion profile was present, consistent with PFAAs sources at surface, with ∑17PFAAs concentrations at 5 m depth of 369.0 pg L−1, and descending to 317.2 pg L−1 at 2000 m depth. This decrease was mainly driven by PFOA, PFNA, and PFDA, three long chain PFCA, thus with larger potential for sorbing to settling particles. At 28°N and 10°N, no discernible vertical trends were found, with especially low concentrations in the latter, ranging from 36.0 pg L−1 at surface to 120 pg L−1 at 400 m depth. Low concentrations were also found at Equator (station 12), slightly increasing from 42.7 pg L−1 at the surface to 125 pg L−1 at 2000 m depth. The lower occurrence of PFAAs at 10°N and 0°N is consistent with their distance from potential source regions in Europe and America. Conversely, at 14°S and 46°S, maximum concentrations of 144 pg L−1 and 461 pg L−1 were found at 350 m and 200 m depth, respectively. The diverse profiles at different stations may reflect different influences of sources, with the largest at 37°N and 46°S, but also related to the fact that sampling was performed at different stages of the physical and biological seasonal succession. The profiles at latitudes 37°N, 28°N, and 10°N (stations 1, 4, and 9) account for the conditions during winter, while the profiles at 14°S and 46°S (stations 15 and 19) account for depth profiles in summer conditions. The relative contribution of individual PFAAs at Equator (0°S, station 12) was characterized by a higher contribution of PFCAs (91%) to ∑17PFAAs, than in the other stations (Supplementary Table S7). The Equator is one of the few oceanic regions receiving significant wet deposition events38, and rain is generally enriched in PFCAs in comparison to PFSAs11,33. In addition, equatorial regions, or those regions with upwelling waters, such as off-Sahara or off-South America, may be subject to lateral/upwelling transport of PFAS at depth further affecting the depth trends of PFAAs occurrence.

Despite the decreasing trend in PFAAs concentrations that arise when comparing early with recent reports from the Atlantic Ocean11,17,24,35, a notable variability of ∑12PFAS concentrations at surface, meso-pelagic and deep waters occurs as shown in this work and elsewhere (n.d to 224 pg L−1)35. This contrasts with observations from the Indian Ocean, where a general pattern of surface enrichment and depth depletion has been described, with concentrations decreasing to a few pg L−1 at depths deeper than 1000 m36. The elucidation of the major processes affecting the depth distribution of PFAAs requires future research efforts, as this is a key feature driving the oceanic reservoir of PFAAs.

The deep ocean integrates long-term inputs, mainly originating from the biological pump transport of PFAS23. As settling particles release PFAAs when organic matter is remineralized, PFAAs can build up their concentrations in deep waters. At 2000 m depth, ∑17PFAAs averaged 142 pg L−1, with the maximum value at 37°N, off-shore the Iberian Peninsula. The range of concentrations at 5 m depth measured in the vertical profiles (average of 159 pg L−1, ranging from 36.0 to 369 pg L−1) was not significantly different than at 2000 m depth. Furthermore, the relative contributions of PFHpA (58%), PFPeA (26%), and PFOA (9%) at 2000 m depth were similar than at surface (46%, 27% and 12%, respectively). Such similarities between the surface and deep ocean in terms of concentrations and patterns are strong indicators of the persistence of PFAAs under oceanic conditions. The low concentrations of PFAS reported previously for the Indian Ocean36 may be related to lower historical inputs in this region and different oceanographic conditions.

Occurrence of PFCAs and PFSAs in the Southern Ocean

In the Southern Ocean, concentrations of ∑17PFAAs averaged 189 pg L−1 at 5 m depth (ranging from 72.7 to 343 pg L−1), with ∑6PFSAs ranging from 13.6 to 149 pg L−1 and ∑11PFCAs ranging from 59.1 to 214 pg L−1 (Supplementary Table S5). At the DCM, ∑17PFAAs averaged 189 pg L−1 (with a range of 72.7–336.0 pg L−1), with ∑6PFSAs ranging from 15.8 to 121 pg L−1 and ∑11PFCAs ranging from 51.7 to 286 pg L−1 (Supplementary Table S5). As in the Atlantic Ocean, PFAAs concentrations at surface were correlated with those at the DCM (R2 = 0.72, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2), with no significantly different concentrations between both depths.

The measurements in the Southern Ocean were conducted away from research stations, with the exception of station 28 (Deception Island), and were, therefore, not affected by their localized impact12,28. At the inner harbour of Deception Island (station 28), ∑17PFAAs concentrations were not significantly higher than those in the proximate open ocean stations, despite the presence of two research stations inside the volcano caldera and the visits of thousands of tourists during the austral summer.

PFAAs in the open Southern Ocean reported here are the only recent measurements for open waters in the Southern Ocean. These concentrations are comparable to those previously reported in bays from Livingston Island, and Port Foster in Deception Island11,12, but significantly lower than those reported by others at King George Island14. Generally, these concentrations in Western Antarctic seawaters are higher than those in Eastern Antarctica13, and significantly higher than those reported for the open Southern Ocean in early reports of PFAAs in north-south transects10,25,27. For example, the previous reports of PFOS and PFOA in open Southern Ocean waters were of 21.7 ± 12.9 and below LOD, respectively, for samples taken in 200825, and of 6.2 ± 3.4 pg L−1 and 0.8 ± 0.8 pg L−1, respectively for samples taken in 201011. These PFOS and PFOA concentrations are significantly lower than the 41.2 ± 10.2 pg L-1 and 8.5 ± 1.1 measured here, respectively, for samples taken in 2022. The increase for other PFAAs is even more pronounced as they were not detected in early assessments of PFAAs for open Antarctic waters.

Legacy POPs have previously been reported in Western Antarctic seawaters, including PCBs39, HCHs40, or PAHs41,42, with concentrations higher than in other Antarctic regions. This occurrence of semi-volatile POPs is driven by the large influence of air masses entering from the north, which bring POPs to the Antarctic region by atmospheric transport33,41,43,44 and are associated with wet deposition events11,12,43, even though for semi-volatile chemicals diffusive air-water exchange is a key input to the region39,40. Indeed, for semi-volatile chemicals, such PCBs, HCHs, and PAHs, long range atmospheric transport is driven by successive volatilization and deposition processes (grasshopping)18,45. Conversely, PFAAs are highly soluble compounds at environmental pH values, and their volatilization-absorption fluxes are negligible.

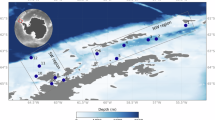

Three Southern Ocean vertical profiles were measured at stations 24, 27, and 28 (Figs. 1 and 3, and Supplementary Table S6). At station 27 (62°S), there were relatively constant ∑17PFAAs concentrations through the water column averaging 93.5 pg L−1 (124, 79.5, 110, 76.5, and 77.4 pg L−1, from 5 to 1620 m depth, respectively) with no significant changes of the relative abundance of individual PFCAs. Conversely, PFOS showed a decreasing pattern from 33.7 pg L−1 at surface to 7.5 pg L−1 at 1620 m. Inside the proximate Deception Island volcano (62°S, station 28), ∑17PFAAs concentrations were not significantly different between 5 and 40 m depth, and decreased at 155 m depth close to the bottom (72.0, 72.7, and 38.2 pg L−1, respectively). The vertical profile at station 24 (70.8°S, 79.9°W), situated at the southernmost station, showed a surface enrichment depth depletion distribution with ∑17PFAAs concentration of 346, 265, 158, and 94.5 pg L−1 at 5, 75, 210, and 584 m (close to bottom) depths, respectively. Such decrease was mainly driven by PFCAs.

Latitudinal and depth distribution of concentrations (pg L−1) for ∑11PFCAs (top panels) and ∑6PFSAs (bottom panels), in the Atlantic Ocean (right panels) and Southern Ocean (left panels). The circle’s color accounts for concentrations of different magnitude. Black line and shadow show the bathymetry of the ocean.

Generally, there were higher contributions of PFCAs than PFSAs in Antarctic waters. This is consistent with rain and snow PFAAs inputs, as these are enriched in PFCAs to a greater extent than PFSAs11,12,33. Snow and rain are the only plausible long-range transport sources of PFAAs to the Southern Ocean, south of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (Antarctic Divergence).

North-south transport of PFAAs and accumulation in the Southern Ocean

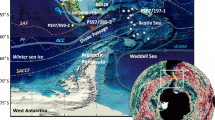

The southward transport of PFAAs from the South Atlantic into the Southern Ocean can be explained by taking into account the observed PFAAs distribution together with the general oceanic and atmospheric circulation pattern (Fig. 4). In the Atlantic Ocean, concentrations of Σ17PFAAs at 5 m depth declined from 369 pg L⁻¹ at 37°N to 90.7 pg L⁻¹ at 14°S. The higher concentrations in the North Atlantic in comparison to Equatorial and intertropical regions are consistent with larger potential sources from Europe, while the sampling points at low latitudes were distant from continents, reflecting lower influence from potential sources. The high ∑17PFAAs concentrations at stations 16 and 18 (467 and 810 pg L−1, respectively) reflect the influence from proximate Argentina and Brazil, as well as the influence of the warm current descending along the eastern coast of South America, transporting water masses from off-shore Brazil to the South Atlantic. Further south, in Antarctic waters south of the Antarctic Divergence, unexpectedly, high ∑17PFAAs concentrations, comparable to those measured in the Northern Atlantic, were found. This finding is not consistent with the suggested role of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current as a barrier for the transport of PFAAs to Antarctica.

The accumulation of PFAAs to Antarctica arise from their aerosolization mediated by sea-spray aerosols in the sub-Antarctic surface water, followed by atmospheric transport and wet deposition in the Antarctic Peninsula region. Once in Antarctic waters, the Antarctic Divergence prevents their transport out of the region.

Wet deposition arises as the only process that can explain the large-scale occurrence of PFAAs in the Southern Ocean. Recently, it has been suggested that both snow and rain deposition events could be relevant sources of PFAAs to coastal Antarctica11,12,33. For example, PFCAs concentrations are more than one order of magnitude higher in freshly deposited snow (760–3600 pg L−1) than in seawater (94–420 pg L−1)12. The transport of PFAAs from the southern subtropical Atlantic Ocean to the sub-Antarctic current will occur by oceanic transport, with a contribution from sea-spray mediated grasshopping. Such grasshopping is different than that responsible for the transport of semi-volatile POPs which is driven by volatilization-absorption. For PFAAs, the grasshopping would occur by aerosolization mediated by sea-spray formation and deposition of the sea-spray aerosols after atmospheric transport (Fig. 4). The Southern Ocean, and especially the sub-Antarctic waters, are characterized by high wind speeds, and are the world region of a larger emission flux of PFAAs associated with sea-spray46. In the region around the Antarctic Peninsula, there are incursions of air masses from the north that are humid, with such moisture originating in the sub-Antarctic zone (around 50°S)47, and resulting in wet deposition of PFAAs by rain or snow12,33. Such wet deposition increases the concentrations of PFAAs in Antarctic coastal surface waters12. Here we show that such PFAAs occurrence is widespread in the open Bellingshausen Sea and Bransfield Strait, and thus rain and snow deposition are relevant sources for the Southern Ocean surrounding the Antarctic Peninsula. Wet deposition of PFAAs neutral precursors or their oxidation products may also contribute to the PFAAs inputs in the region. The snow (and rain) deposition events are especially relevant, at large scale, in the Antarctic Peninsula regions, to a greater extent than in other coastal Antarctica regions48. A yearly wet deposition of rain/snow of 445 mm (water equivalents) per year has been reported at Livingston Island49, and the extent of snow deposition is even larger in some areas of the Antarctic Peninsula region48. Concentrations of PFAAs in Antarctic snow and rain range from 200 pg L−1 to 20,000 pg L−19,12. Assuming an average PFAAs concentration of 2000 pg L−1, and a wet deposition flux of 500 mm y−1, would result in an atmospheric input of 1,000,000 pg m−2 y−1. If this is diluted in the top 100 m of the water column would result in an increase annually of 10 pg L−1 of PFAAs, probably more for surface waters. In addition, flushing to the sea after snow melting on land would add to the PFAAs burden11,12.

As a reservoir, taking into account the volumes of seawater in the photic zone (top 200 m) of the Southern Ocean, and the South and North Atlantic oceans, there are 650 Tn, 1180 Tn, and 1750 Tn of PFAAs, respectively. For the Southern Ocean this may be an upper end estimate, as not all the Antarctic sectors have the same level of PFAAs wet deposition inputs. Therefore, the relatively high levels of PFAAs in Antarctic waters can be reached even if a relatively small fraction of the oceanic reservoir of PFAAs is in the Antarctic Peninsula sector.

An accumulation of PFAAs to the levels observed in this work, higher than in early studies of PFAAs in the Southern Ocean, can only occur if the inputs are larger than sinks and sustained over time. A potential sink for PFAAs is the biological pump, but even if this is relevant in explaining the occurrence of PFAAs in the deep ocean, the resulting residence times in the water column due to this sink are longer for PFAAs16,23 than for other legacy POPs such as PCBs, for which the biological pump effectively depletes the surface concentrations in the ocean19,39. Microbial degradation has been suggested for PFOS in seawater from Deception Island37, but its relevance for the rest of Antarctic waters is unclear. Generally, PFCA concentrations are much higher than those of PFSAs in the ocean. PFCAs arise as perfectly persistent, truly forever chemicals. Once PFAAs reach Antarctica, their aerosolization by sea-spray formation will be lower than in the region north of the Antarctic Divergence, as wind speeds are lower in Antarctic waters. Indeed, PFAS transfer to the atmosphere has been estimated to be larger in regions north of 60°S than in seawater south of the Antarctic divergence46. Therefore, atmospheric transport of PFAAs from Antarctic waters out of the region will be of lower magnitude than the atmospheric inputs in the opposite direction. In addition, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current has a dual role as both a barrier for the input and output of PFAAs to/from Antarctica by oceanic currents (Fig. 1). The accumulation of PFAAs in this Antarctic sector would originate from a net atmospheric input to the region. For other POPs, the biological pump for PCBs39, or degradation for PAHs or HCHs40,50, reduces their concentrations and prevents their long-term increasing accumulation in Antarctic waters. For these semivolatile POPs, their concentrations in Antarctica are lower, thus generally not comparable, to those observed in the North Atlantic Ocean. However, for extremely persistent chemicals such as PFAAs, this results in a long-term accumulation around the Antarctic Peninsula. The fact that concentrations were higher at the southernmost stations (Fig. 1) is consistent with increasing inputs from deposition or melting, which supports the levels of the East Wind Drift current along the Antarctic Peninsula. The Antarctic Peninsula receives more precipitation events than other Antarctic regions51, which is also consistent with the generally higher levels of PFAAs and other contaminants here than in other Antarctic sectors.

This unexpected accumulation evidences the global risk posed by persistent chemicals, raises concerns on the risk posed to the Antarctic ecosystem, and will require further research on the occurrence of many persistent contaminants of emerging concern, such as the thousands of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances currently used by the contemporaneous society2,52.

Methods

Sampling

Seawater from 5 m depth (below the influence of the ship), and along the water column down to a depth of 2000 m, was collected during two oceanographic expeditions. During the ANTOM-I cruise (December 2020-January 2021), from Vigo (Spain) to Punta Arenas (Chile), a total of 19 stations were sampled along a latitudinal transect in the Atlantic Ocean onboard the R/V Sarmiento de Gamboa. The second campaign, ANTOM-II, focused on the Southern Ocean west of the Antarctic Peninsula, covering 9 stations in the Bransfield Strait and the Bellingshausen Sea, conducted onboard the R/V Hespérides from January to February 2022 (Supplementary Table S1). Seawater samples were collected using a Niskin-rossete system equipped with a Sea-bird SBE 9 CTD, which measured salinity, temperature, fluorescence, depth, and oxygen concentrations, enabling characterization of the water column. The 5 m depth water samples were collected at 28 stations (19 in the Atlantic, and 9 in the Southern Ocean). In addition, seawater from the DCM, determined using the fluorescence from the CTD, was sampled at thirteen stations in the Atlantic Ocean and seven stations in the Southern Ocean. Vertical profiles (5 depths) were obtained at six stations in the Atlantic Ocean and at three stations in the Southern Ocean. These profiles included samples from the layer with 1% of photosynthetic active radiation (1% PAR), the layer with minimum of oxygen (MOx), and at a depth of 2000 m depth, in addition to surface and DCM.

Sample treatment

Samples were extracted on board following a previously published procedure8,11 with minor modifications. Briefly, samples were filtered with pre-combusted glass fiber filters (GF/F, 0.7 µm, Whatman) and spiked with 1000 pg of a 13C-labeled mixture of nine recovery standards (Supplementary Note S1, Supplementary Table S2). Then, filtered samples were extracted by solid phase extraction at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1 using Oasis Wax 6cc cartridges pre-conditioned with 6 ml of 0.1% ammonia in MeOH, 6 mL of MeOH, and 6 mL of HPLC-grade water. Salts were washed with one cartridge volume of HPLC-grade water, and cartridges were vacuum-dried for 10 min before being labelled and frozen at −20 °C until final treatment in an ultraclean laboratory.

After unfreezing, each cartridge was conditioned in a clean laboratory with 6 mL of ammonium acetate buffer (25 mM) at pH 4, and centrifuged 4 min at 3500 rpm to eliminate excess water. Samples were then eluted with 8 mL of MeOH containing 0.1% ammonia and dry-evaporated under N2 stream, and reconstituted in 300 µl PP vials with 50:50 MeOH-H2O.

Instrumental analysis

Instrumental analysis was performed with a Waters Acquity Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography system coupled with a Waters XEVO TQS, triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (UPLC-MS/MS) using an established method with minor modifications16,33. Specific conditions of the equipment are described in Supplementary Note S2. Before the injections, vials were spiked with 1000 pg of a mixture of 6 C-labelled internal standards (Supplementary Table S2). Each sample was analysed in duplicate with an injection volume of 10 μL. Quantification was based on a calibration curve of 12 points (0.005–100 pg). All native and labelled standards were purchased from Wellington Laboratories. Quality Control/Quality Assurance protocols are detailed in Supplementary Note S1, and Supplementary Tables S8 and S9.

Statistical analysis

The normality of concentrations was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, which revealed a non-normal distribution. Consequently, non-parametric statistical tests were employed to compare groups of samples. To determine statistically significant differences among groups, t-test and Mann-Whitney U test were used with a significance level of 0.05. Linear regression models were used to assess the linear relation among groups of paired samples. The statistical analysis was carried out using R-Studio (version 2024.09.1 + 394).

Data availability

The complete data set of PFAAs concentrations and ancillary data is available at https://zenodo.org/records/15425789.

References

Lindstrom, A. B., Strynar, M. J. & Libelo, E. L. Polyfluorinated compounds: past, present, and future. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 7954–7961 (2011).

Glüge, J. et al. An overview of the uses of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 22, 2345–2373 (2020).

Cousins, I. T., Johansson, J. H., Salter, M. E., Sha, B. & Scheringer, M. Outside the safe operating space of a new planetary boundary for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 11172–11179 (2022).

Cousins, I. T. et al. The high persistence of PFAS is sufficient for their management as a chemical class. Environ. Sci. Proc. Impacts 22, 2307–2312 (2020).

Ackerman Grunfeld, D. et al. Underestimated burden of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in global surface waters and groundwaters. Nat. Geosci. 17, 340–346 (2024).

Ahrens, L. & Bundschuh, M. Fate and effects of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in the aquatic environment: a review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 33, 1921–1929 (2014).

Yamashita, N., Kannan, K., Taniyasu, S. & Horii, Y. A global survey of perfluorinated acids in oceans. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 51, 658–668 (2005).

González-Gaya, B., Dachs, J., Roscales, J. L., Caballero, G. & Jiménez, B. Perfluoroalkylated substances in the global tropical and subtropical surface oceans. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 13076–13084 (2014).

Benskin, J. P. et al. Perfluoroalkyl acids in the Atlantic and Canadian Arctic oceans. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 5815–5823 (2012).

Zhao, Z. et al. Distribution and long-range transport of polyfluoroalkyl substances in the Arctic, Atlantic Ocean and Antarctic coast. Envion. Pollut. 170, 71–77 (2012).

Casas, G. et al. Inputs, amplification and sinks of perfluoroalkyl substances at coastal Antarctica. Envion. Pollut. 338, 122608 (2023).

Casal, P. et al. Role of snow deposition of perfluoroalkylated substances at coastal Livingston Island (Maritime Antarctica). Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 8460–8470 (2017).

Shan, G. et al. Legacy and emerging per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances in surface seawater from Northwestern Pacific to Southern Ocean: evidences of current and historical release. J. Hazard. Mater. 411, 125049 (2021).

Cai, M. et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in snow, lake, surface runoff water and coastal seawater in Fildes Peninsula, King George Island, Antarctica. J. Hazard. Mater. 209–210, 335–342 (2012).

Yu, J. et al. Marine transport barrier for traditional and emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the Southeast Indian Ocean and Antarctic Marginal Seas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 59, 5283–5292 (2025).

González-Gaya, B., Casal, P., Jurado, E., Dachs, J. & Jiménez, B. Vertical transport and sinks of perfluoroalkyl substances in the global open ocean. Environ. Sci. Process Impacts 21, 1957–1969 (2019).

Muir, D. & Miaz, L. T. Spatial and temporal trends of perfluoroalkyl substances in Global Ocean and Coastal Waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 9527–9537 (2021).

Jurado, E. & Dachs, J. Seasonality in the ‘grasshopping’ and atmospheric residence times of persistent organic pollutants over the oceans. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35 (2008).

Galbán-Malagón, C., Berrojalbiz, N., Ojeda, M. J. & Dachs, J. The oceanic biological pump modulates the atmospheric transport of persistent organic pollutants to the Arctic. Nat. Commun. 3 (2012).

González-Gaya, B. et al. High atmosphere-ocean exchange of semivolatile aromatic hydrocarbons. Nat. Geosci. 9, 438–442 (2016).

Lohmann, R., Jurado, E., Dijkstra, H. A. & Dachs, J. Vertical eddy diffusion as a key mechanism for removing perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) from the global surface oceans. Envion. Pollut. 179, 88–94 (2013).

Armitage, J. M., Schenker, U. R. S., Scheringer, M., Martin, J. W. & Macleod, M. Modeling the global fate and transport of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and Precursor compounds in relation to temporal trends in wildlife exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 9274–9280 (2009).

Casal, P. et al. Accumulation of perfluoroalkylated substances in oceanic plankton. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 2766–2775 (2017).

Yamashita, N. et al. Perfluorinated acids as novel chemical tracers of global circulation of ocean waters. Chemosphere 70, 1247–1255 (2008).

Ahrens, L., Xie, Z. & Ebinghaus, R. Distribution of perfluoroalkyl compounds in seawater from Northern Europe, Atlantic Ocean, and Southern Ocean. Chemosphere 78, 1011–1016 (2010).

Xie, Z. & Kallenborn, R. Legacy and emerging per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances in polar regions. Curr. Opin. Green. Sustain. Chem. 42, 100840 (2023).

Wei, S. et al. Baseline distribution of perfluorinated compounds in surface seawaters between Asia and Antarctica. Mar. Poll. Bull. 54, 1813–1818 (2007).

Wild, S. et al. An antarctic research station as a source of brominated and perfluorinated persistent organic pollutants to the local environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 103–112 (2015).

Bengtson Nash, S. et al. Perfluorinated compounds in the Antarctic region: Ocean circulation provides prolonged protection from distant sources. Envion. Pollut. 158, 2985–2991 (2010).

Dreyer, A., Weinberg, I., Temme, C. & Ebinghaus, R. Polyfluorinated compounds in the atmosphere of the Atlantic and Southern Oceans: evidence for a global distribution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 6507–6514 (2009).

Del Vento, S., Halsall, C., Gioia, R., Jones, K. & Dachs, J. Volatile per- and polyfluoroalkyl compounds in the remote atmosphere of the western Antarctic Peninsula: an indirect source of perfluoroalkyl acids to Antarctic waters?. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 3, 450–455 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. Neutral poly/per-fluoroalkyl substances in air from the Atlantic to the Southern Ocean and in Antarctic Snow. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 7770–7775 (2015).

Casas, G., Martinez-Varela, A., Vila-Costa, M., Jiménez, B. & Dachs, J. Rain amplification of persistent organic pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 12961–12972 (2021).

Zhang, X., Lohmann, R. & Sunderland, E. M. Poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in seawater and plankton from the Northwestern Atlantic Margin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 12348–12356 (2019).

Savvidou, E. K., Sha, B., Salter, M. E., Cousins, I. T. & Johansson, J. H. Horizontal and vertical distribution of perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) in the water column of the Atlantic Ocean. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 10, 418–424 (2023).

Han, T. et al. Spatial distribution, vertical profiles and transport of legacy and emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the Indian Ocean. J. Hazard. Mater. 437, 129264 (2022).

Cerro-Gálvez, E. et al. Microbial responses to perfluoroalkyl substances and perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) desulfurization in the Antarctic marine environment. Water Res. 171, 115434 (2020).

Jurado, E. et al. Wet deposition of persistent organic pollutants to the global oceans. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 2426–2435 (2005).

Galbán-Malagón, C. J., Del Vento, S., Cabrerizo, A. & Dachs, J. Factors affecting the atmospheric occurrence and deposition of polychlorinated biphenyls in the Southern Ocean. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 12029–12041 (2013).

Galbán-Malagón, C., Cabrerizo, A., Caballero, G. & Dachs, J. Atmospheric occurrence and deposition of hexachlorobenzene and hexachlorocyclohexanes in the Southern Ocean and Antarctic Peninsula. Atmos. Environ. 80, 41–49 (2013).

Casal, P. et al. Pivotal role of snow deposition and melting driving fluxes of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons at Coastal Livingston Island (Antarctica). Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 12327–12337 (2018).

Iriarte, J. et al. Snow-dependent biogeochemical cycling of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons at Coastal Antarctica. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 1625–1636 (2023).

Casal, P. et al. Snow amplification of persistent organic pollutants at coastal Antarctica. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 8872–8882 (2019).

Khairy, M. A., Luek, J. L., Dickhut, R. & Lohmann, R. Levels, sources and chemical fate of persistent organic pollutants in the atmosphere and snow along the western Antarctic Peninsula. Envion. Pollut. 216, 304–313 (2016).

Wania, F. & Mackay, D. Tracking the distribution of persistent organic pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 30, 390A–396A (1996).

Sha, B., Johansson, J. H., Salter, M. E., Blichner, S. M. & Cousins, I. T. Constraining global transport of perfluoroalkyl acids on sea spray aerosol using field measurements. Sci. Adv. 10, 1–10 (2024).

Sodemann, H. & Stohl, A. Asymmetries in the moisture origin of Antarctic precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36 (2009).

Dalaiden, Q., Goosse, H., Lenaerts, J. T. M., Cavitte, M. G. P. & Henderson, N. Future Antarctic snow accumulation trend is dominated by atmospheric synoptic-scale events. Commun. Earth. Environ. 1, 1–9 (2020).

Bañón, M., Justel, A., Velázquez, D. & Quesada, A. Regional weather survey on Byers Peninsula, Livingston Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. Antarct. Sci. 25, 146–156 (2013).

González-Gaya, B. et al. Biodegradation as an important sink of aromatic hydrocarbons in the oceans. Nat. Geosci. 12, 119–125 (2019).

Thomas, E. R., Marshall, G. J. & McConnell, J. R. A doubling in snow accumulation in the western Antarctic Peninsula since 1850. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35 (2008).

Schymanski, E. L. et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in PubChem: 7 million and growing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 16918–16928 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of the Spanish Government with project ANTOM (PGC2018-096612-B-I00) and PANTOC (PID2021-127769NB-I00). N.T.P. and J.I. have been funded with predoctoral FPI and FPU fellowships, respectively. We thank the UTM-CSIC and the crew from R/V Sarmiento de Gamboa and R/V Hespérides for technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.T.P., J.D., M.V.C., and B.J. conceived the work. N.T.P., J.D., J.I., N.B., G.C., and B.J. did the field work. N.T.P., N.B., P.C., O.G.G., and B.J. performed the chemical analysis. N.T.P., J.D., and B.J. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion and final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Hongyuan Zheng and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Somaparna Ghosh [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Trilla-Prieto, N., Dachs, J., Iriarte, J. et al. Accumulation of perfluoroalkyl acids as forever chemicals in Antarctic waters. Commun Earth Environ 6, 545 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02535-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02535-3