Abstract

As a sub-type of micrometeorites, I-type cosmic spherules form by complete melting and oxidation of extraterrestrial Fe, Ni metal particles during their atmospheric entry. All oxygen in the resulting Fe, Ni oxides sources from the Earth’s atmosphere and hence makes them probes for the composition of atmospheric oxygen. When recovered from sedimentary rocks, they allow the reconstruction of the triple oxygen isotope composition of past atmospheric O2, providing quantitative constraints on past CO2 levels or global primary production. Here we establish using fossil I-type cosmic spherules as an archive of Earth’s atmospheric composition with the potential for a unique record of paleo-atmospheric conditions dating back billions of years. We present combined triple oxygen and iron isotope compositions of a collection of fossil I-type cosmic spherules recovered from Phanerozoic sediments. We reconstruct the triple oxygen isotope anomalies of past atmospheric O2 and quantify moderate ancient CO2 levels during the Miocene (~8.5 million years) and late Cretaceous (~87 million years). We also demonstrate this method’s competitive precision for paleo-CO2 determination, despite challenges in finding micrometer-sized unaltered fossil I-type cosmic spherules. Our work indicates that morphologically intact spherules can be isotopically altered by terrestrial processes, underscoring the need for rigorous sample screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Earth receives a continuous flux of small extraterrestrial particles. When hitting the Earth’s atmosphere with hypervelocity, such particles are visible as shooting stars. The remnants of such objects are termed micrometeorites and comprise particles smaller than 2 mm1. Those micrometeorites that suffered complete melting in the upper atmosphere at 85 – 90 km are termed cosmic spherules2. Micrometeorites with terrestrial ages <2 Ma (hereafter referred to as modern) can be collected in Antarctica or even from roof tops, with the latter being called urban micrometeorites with very young decades or centuries long terrestrial ages. Geologically old fossil micrometeorites are preserved in sediments with the oldest record dating 2.7 Ga back in Earth’s history3,4,5,6,7,8. Iron-rich I-type cosmic spherules are virtually the exclusive component in fossil micrometeorite collections due to their resistance to weathering6. The I-type cosmic spherules are composed of Fe, Ni oxides, namely wüstite (FeO) and magnetite (Fe3O4) and residual metal9. Their I-type micrometeorite precursor consists of Fe, Ni metal alloy, which is gradually oxidized in molten state during atmospheric interaction9. Thus, the entire oxygen in I-type cosmic spherules originates from the atmosphere, which is, e.g., CO2 for the Archean or O2 for younger samples after the Great Oxidation Event10,11.

It has been demonstrated on Quaternary Antarctic I-type cosmic spherules that the triple oxygen isotope anomaly of air O2 can be reconstructed from combined triple oxygen and iron isotope compositions10,11. Both, oxygen and iron in unaltered modern I-type spherules are enriched in heavy isotopes due to evaporation during atmospheric entry10,11,12. The iron isotopes are used in this approach as proxy for the degree of atmospheric evaporation, because iron is only affected by evaporation and, unlike oxygen, not by exchange with the atmosphere.

Atmospheric O2 carries a 17O oxygen isotope anomaly that is isotopically homogenous up to ~80 km10. The oxygen isotope anomaly observed in atmospheric O2 is a function of atmospheric CO2 levels or the global primary production (GPP)13,14,15. The 17O depletion of air O2 counterbalances the 17O enrichment of stratospheric O3 and CO2. The larger the stratospheric CO2 reservoir, the larger the negative anomaly of O2. Anomalous O2 is diluted by isotopically normal O2 from photosynthesis, i.e., the anomaly of O2 becomes smaller with increasing GPP. The triple oxygen isotope composition of air O2 hence is a proxy for the size of the atmospheric CO2 reservoir (i.e., CO2 mixing ratio) or GPP.

Variations in the oxygen and iron isotope ratios are expressed with the δ notation with Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) as reference scale for oxygen and IRMM-14 for iron isotopes16 (Eq. 1). Equation 1 can equally be written for δ17O as well as for δ56Fe and δ57Fe with 54Fe in the denominator of the isotope ratio expressions.

Deviations in δ17O from a reference line are expressed in the Δ’17O notation (Eq. 2). For Δ’17O, we use a reference line (RL) with a slope of λRL = 0.528 and zero intercept17,18,19. Similarly, Eq. 2 can be used to express deviations from the correlated relation of δ56Fe and δ57Fe (Δ‘56Fe notation). We use the high-temperature approximation for triple iron isotope equilibrium fraction as a reference line with λRL = 0.678 for Δ‘56Fe20.

Modern I-type cosmic spherules have δ18O values up to 57‰ and δ56Fe up to 45‰10,11,12. Reported Δ’17O and Δ’56Fe of modern spherules vary between −0.5‰ and −0.8‰ and −0.05‰ and −0.18‰, respectively10,11. No such combined triple oxygen and iron isotope data have been published on fossil I-type cosmic spherules yet. This is due, on the one hand, to a lack of analytical precision in Δ′17O analysis of established techniques for samples as small as fossil I-type cosmic spherules with diameters predominantly <200 µm. On the other hand, it is not known whether widely abundant chemical and mineralogical diagenetic alteration of fossil I-type cosmic spherules4,5 also affects their oxygen and iron isotope composition.

Here, we report triple oxygen and iron isotope data of fossil I-type cosmic spherules that were collected from sedimentary rocks of Silurian to Miocene age (~411–7 Ma). We present a technique for the combined analysis of oxygen and iron isotopes of small samples. We also provide details of a non-destructive technique on the identification of diagenetic alteration in a large set of cosmic spherules. We evaluate the isotopic results for their potential to reconstruct past atmospheric Δ′17O, CO2 levels, or GPP, and compare their precision and significance to established CO2 proxies.

Results and discussion

Spherule characteristics and isotopic compositions

In total 92 micrometeorites were extracted from six sediments from different localities spanning the Carboniferous to Cretaceous periods. In addition, eight micrometeorites from existing collections4,5,21 were included in the study, extending the investigated time span from Silurian to Quaternary periods (Supplementary Table S1). All micrometeorites are I-type cosmic spherules. The spherules have diameters between 18 and 429 µm (Supplementary Table S2). The estimated masses of individual spherules, based on their diameters and assumed bulk density of 5 g cm−3 22, range from 0.02 to 103 µg with a median mass of 0.2 µg.

The I-type cosmic spherule exteriors show characteristic dendritic textures and no signs of terrestrial alteration in the secondary electron images (Fig. 1). The samples´ surface mineralogy, determined with the Energy Dispersive X-ray detector (EDX), is composed of Fe oxides. Nickel is present in two Miocene spherules with 1.80 wt% (MDC-D4) and 4.28 wt% (MDC-A5) and Cretaceous spherule SUT11-3 with 0.52 wt% (Supplementary Table S3). Cobalt is abundant in one Carboniferous spherule with 0.50 wt%. Chromium is present in two Permian spherules and three Cretaceous spherules with concentrations between 0.08 wt% and 0.78 wt%. Manganese is detectable from the surface EDX analyses in ~50% of the analyzed I-type cosmic spherules with abundances between 0.21 wt.% and 1.85 wt.%.

Displayed are nine of the investigated spherules, exhibiting different types of larger and smaller external dendritic textures. The figure shows samples from the modern Antarctic sedimentary trap (A), Miocene marl (B), Cretaceous lime marl (C), Triassic paleosoil (D), Triassic arkosic sandstone (E, F), Permian Halite (G, H), and Carboniferous Limestone (I). The images were taken prior to the cleaning procedure for oxygen isotope analysis. Some samples show fragments of the host sedimentary rocks sticking at the surface (B, C, D, I).

The triple oxygen isotope composition was determined for one modern (MA-9) and 20 fossil I-type cosmic spherules large enough for individual analysis (>1 µg23). The results are listed in Table 1. Modern sample MA-9 was split into several aliquots to match the small mass of the individual fossil spherules. The investigated I-type cosmic spherules show two distinct patterns of triple oxygen isotope variations (Fig. 2). Most samples cluster between 2.8‰ and 10.0‰ in δ18O, with a Δ’17O of −0.48‰ to -0.08‰ referred hereafter as the low δ18O population. A second group comprising of five I-type cosmic spherules scatter in a wider range with elevated δ18O between 21.9‰ and 54.0‰ and Δ’17O values between −1.54‰ and −0.03‰. Four of the high- δ18O specimens, including one modern, one Miocene and two Cretaceous spherules, fall on an extrapolated linear triple oxygen isotope trend described by modern Antarctic I-type cosmic spherules. Miocene sample MDC-D4 and Cretaceous sample SUT11-3 have triple oxygen isotope compositions in the range of unaltered modern specimens (δ18O = 39–48‰, Δ’17O = −0.5 to −0.8‰, Fig. 2). Cretaceous sample SUT16-1 is on an extended range of the trend described by modern I-type cosmic spherules with a δ18O of 21.9 and a Δ‘17O of −0.03‰. The Miocene sample MDC-A5 has a distinctively low Δ’17O of −1.54‰, deviating from the trend of modern Antarctic I-type cosmic spherules with an offset of −0.83‰.

The linear regression (gray solid line) is defined by modern I-type cosmic spherules11. The majority of fossil spherules are diagenetically altered (black ellipse). The gray-blue dashed curves represent equilibration of oxygen from specimens with modern oxygen isotope composition and oxygen from different meteoric waters54. The brown-red dotted curves represent equilibration of oxygen from spherules with a presumed unaltered oxygen isotope composition (brown-red hexagon) with oxygen from meteoric waters54, indicating a lower Δ’17O of the Middle Triassic atmosphere (cyan star). The vertical lines of both equilibration line types indicate 10% intervals. Error bars and envelopes are 1SD.

The triple iron isotope composition was determined for one modern (MA-9) and 12 fossil I-type cosmic spherules that were large enough for individual analysis (Table 1). A majority of the I-type cosmic spherules cluster around 0‰ in δ56Fe, δ57Fe and Δ‘56Fe (Fig. 3). Four I-type cosmic spherules, including one modern, two Miocene and one Cretaceous specimen, show enriched δ56Fe and δ57Fe of 12.1‰ to 34.6‰ and 18.0‰ to 51.7‰, respectively. The four heavily fractionated I-type cosmic spherules follow a linear trend described by modern Antarctic I-type cosmic spherules11 in the Δ‘56Fe versus δ57Fe space with Δ‘56Fe values down to −0.26‰ (Fig. 3). The Δ‘56Fe of the isotopically heavy fossil I-type cosmic spherules is compatible with Rayleigh-type evaporation of Fe and FeO and Graham’s law kinetic fractionation24 with no back-reaction between the spherule and the evaporated gas11 and thus indicative of a preserved primary atmospheric signal.

Modern Antarctic I-type cosmic spherules from the literature11 are presented as reference (gray triangles). The composition of chondritic metal26 is depicted as the presumed precursor of I-type cosmic spherules. The slope of the regression line described by modern specimens (gray solid line) can be explained by Graham’s law fractionation for Rayleigh-type evaporation of Fe (dashed line) and FeO (dotted line) as described in detail by Fischer et al.11. Error bars are 2SD.

The diagenetic alteration of cosmic spherules

The presence of Mn in I-type cosmic spherules is diagnostic of diagenetic terrestrial alteration4. Manganese should be absent in the Fe-oxides as extraterrestrial metal does not contain any lithophile Mn25. Leaching of Ni, Cr and Co, otherwise occurring in detectable amounts in pristine I-type cosmic spherules, is accompanied by implantation of lithophile cations such as Mn, but also Na, Mg, Al and Si4. We demonstrated that the Mn to Fe ratio can be readily determined with non-destructive micro X-ray fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. S1). Micro X-ray fluorescence can be utilized to investigate a large number of spherules for terrestrial alteration (i.e., Mn/Fe > 5 × 10−2) in a time- and resource-efficient manner. The investigated samples in this study show that terrestrial Mn is common in fossil I-type cosmic spherules, independent of host rock lithology and residence time (Supplementary Table S3). The enrichment of Mn is thus likely driven by the abundance of Mn in diagenetic pore fluid.

Fossil I-type cosmic spherules fall into two groups. A small group preserved atmospheric high δ18O and δ56Fe, with elevated Ni and no detectable Mn. A large group shows low δ18O and δ56Fe and elevated Mn (Supplementary Fig. S2). The iron isotope composition of Mn-bearing I-type cosmic spherules investigated here indicates complete mobilization and replacement of extraterrestrial Fe with terrestrial from diagenetic fluids, accompanied with terrestrial values around 0‰ in δ56Fe, δ57Fe26,27 and Δ‘56Fe (Fig. 3). Thus, the strong enrichment in heavy iron isotopes 56Fe and 57Fe seen in pristine I-type cosmic spherules (occurring during evaporation in the atmosphere) is not preserved in diagenetically altered specimens.

The δ18O and Δ’17O variations in the low- δ18O population can be explained by mixing of inherited primary atmospheric O2 with oxygen obtained from equilibration with terrestrial fluids (Fig. 2). The degree of oxygen exchange between unaltered and altered endmembers was estimated with a reconstruction of the mixing curve28 between hydrosphere-equilibrated Fe-oxides and original, evaporated atmospheric Fe-oxides. Under equilibrium low-T conditions there is little oxygen isotope fractionation between magnetite and water29,30. Among the diagenetically altered fossil I-types the degree of exchange of oxygen by oxygen from meteoric water ranges from 65% to 90%. The observation of oxygen exchange with pore fluid is consistent with recrystallization of magnetite from primary wüstite in a terrestrial diagenetic setting4.

We conclude that triple oxygen and iron isotopes can be utilized to assess the proportions of atmospheric signals that are still preserved in the low δ18O population despite chemical alteration (traced by Mn enrichment).

Reconstructing ancient atmospheric oxygen isotope compositions and paleo-CO2 levels

We identified four fossil I-type cosmic spherules that entirely preserved their original (from atmospheric interaction) oxygen and iron composition (no Mn enrichment and high δ18O and δ56Fe). These unaltered fossil I-type cosmic spherules are the Late Miocene samples MDC-A5 and MDC-D4 (~8.5–6.9 Ma) and late Cretaceous samples SUT11-3 and SUT16-1 (~87 Ma). The samples fall on the δ18O versus δ56Fe trend described by modern, unaltered I-type cosmic spherules (Fig. 4A). The relation of Δ’17O and δ56Fe of the high- δ18O specimens agrees closely with the kinetic fractionation trend described by modern I-type cosmic spherules (Fig. 4B). Sample SUT16-1 has a lower δ18O, Δ’17O and δ56Fe than the other three samples, suggesting low grades of evaporation at atmospheric entry. The good agreement with modern, unaltered spherule entry dynamics indicate that the oxygen in the spherules sources from the Miocene (MDC-A5 and MDC-D4) and Cretaceous (SUT11-3 and SUT16-1) Earth atmosphere. However, Miocene sample MDC-A5 falls off the trend and shows a very low Δ’17O (−1.54‰), which we relate to the analytical uncertainty of that sample with ~65% blank contribution (average blank = 44%). We therefore exclude this sample from further discussion on the atmospheric composition, although it otherwise appears structurally, chemically and isotopically (except Δ’17O) pristine. The δ18O (45.4‰) and δ56Fe (25.5‰) of MDC-A5 match well within the distribution of other unaltered I-type cosmic spherules (Fig. 4A).

Displayed are the δ18O (A) and Δ’17O (B) versus δ56Fe of the spherules investigated in this study, together with modern I-type cosmic spherules that are displayed as ref. 11 (gray triangles). The relation between oxygen and iron isotopes of modern I-type cosmic spherules from Fischer et al.11 is represented as gray solid curves. The oxygen isotope composition of modern atmospheric O2 is shown for comparison at a pre-evaporative δ56Fe of 0‰. The vertical offset of sample MDC-A5 in Δ’17O (B) is depicted with a grey dashed arrow. Error bars for oxygen isotopes are 1SD and for δ56Fe they are 2SD.

Unaltered fossil I-type cosmic spherules can be used to derive the Δ’17O of ancient atmospheric O2 and, consequently, to constrain past pCO2 or GPP at these time intervals. Modern pristine I-type cosmic spherules fall on a linear trend in the triple oxygen isotope space (Δ’17O versus δ18O, Fig. 2) with a slope of λ = 0.4995 ± 0.0003 (1SD) and an intercept of 0.57 ± 0.13‰ (1SD)11. The slope is defined by the atmospheric entry processing (kinetic evaporation and oxygen exchange) of the cosmic spherules, which we assume to be similar for modern and fossil specimens. The intercept of the regression function is expected to shift with shifting Δ’17O of atmospheric O2 (modern Δ’17O = −0.432‰18). With this approach, it is possible to reconstruct the Δ’17O of ancient atmospheric O2 directly, even from the isotope composition of a single fossil I-type cosmic spherule that has preserved its primary atmospheric signal (Eq. 3).

Using Eq. 3, the modern Antarctic I-type cosmic spherule from this study (MA-9) yields a value of -0.49 ± 0.08‰ for Δ‘17O of atmospheric O2, which is in good agreement with direct measurements of -0.432‰18. The reconstructed paleo-atmospheric Δ‘17O values for the investigated unaltered fossil spherules are −0.29 ± 0.08‰ for Cretaceous samples SUT11-3, −0.41 ± 0.08‰ for SUT16-1 and −0.42 ± 0.08‰ for Miocene MDC-D4.

The Δ‘17O of paleo-atmospheric O2 provides information about pCO2 and/or GPP (Eq. 4)11,13. For the paleo-pCO2, we first adopt published GPP estimates31. The pCO2 is further depending on the atmospheric pO2 to pCO2 ratio13. A 50% decrease in pO2 from the modern value of 21% is reflected in a decrease of the atmospheric O2 Δ’17O by -0.13‰13. A −0.13‰ lower Δ’17O of atmospheric O2 would result in a ~300 ppmv higher pCO2 at a constant GPP (Eq. 4). In this study we apply the paleo-pCO2 reconstruction on Quaternary to Cretaceous spherules, periods with relatively stable pO2 compared to the modern value32. Possible fluctuations of the pO2 in the range of ±5% do not affect the pCO2 reconstruction above the analytical precision (±180–370 ppmv [1SD]). We thus apply Eq. 4 to the atmospheric O2 Δ’17O with using the models modern day pO2 estimate13. The paleo-pCO2 reconstruction based on the Δ’17O of spherules older than the Jurassic would need an adaption of the model Eq. 4 is based on13 to account for higher or lower paleo-pO2.

Using Eq. 4, the modern Antarctic I-type cosmic spherule MA-9 suggests a pCO2 of 417 ± 180 ppmv (1SD), consistent with pre-industrial CO2 levels of 280 ppmv. The millennium-long residence time of atmospheric O2 prevents the anthropogenic rise in pCO2 from immediately impacting modern atmosphere’s Δ‘17O13. The pCO2 reconstruction of MA-9, supported by published data on Antarctic I-type cosmic spherules10,11, validates the overall approach. However, the interpretation of the reconstructed pCO2 data is challenged by the relatively large uncertainty resulting from analyzing such small samples in the lowest microgram range for their Δ’17O (±0.08‰ [1SD], resulting in pCO2 ± 180–370 ppmv).

Miocene spherule MDC-D4 with an age of ~8.5 Ma4 yields a pCO2 of 294 ± 220 ppmv. Cretaceous specimens SUT13-11 and SUT16-1 with terrestrial residence ages of ~87 Ma5 suggest pCO2 levels of −40 \(\begin{array}{c}+360\\ -0\end{array}\) ppmv and 500 ± 370 ppmv. The average pCO2 from the two 87 Ma Cretaceous spherules is 230 \(\begin{array}{c}+250\\ -230\end{array}\) ppmv.

Significance of the reconstructed CO2 levels

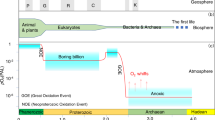

All reconstructed paleo-atmospheric CO2 levels, based on the Δ’17O of I-type cosmic spherules, agree within uncertainty with existing proxy data (LOESS fit)33 and CO2 level models (GEOCARBSULF)34,35 at the respective time intervals (Fig. 5). The spherule, proxy and model data indicate moderate CO2 levels in modern times (<2 Ma) as well as 10 and 90 million years ago.

Displayed are pCO2 reconstructions determined in this study based on fossil I-type cosmic spherules (labeled) in comparison to published data throughout the Phanerozoic, reconstructed with proxies33,36,37 and a mass balance model (GEOCARBSULF)34,35. Proxies include δ13C in liverworts, alkenones (phytoplankton) or paleosols, leaf stomata density and index of land plants and boron isotopes in foraminifers. The light blue trend indicates a 0.5 Myr spaced LOESS fit through the proxy data33. The light brown trend shows the GEOCARBSULF mass balance model34 with an associated uncertainty interval35. The 1SD uncertainties of individual proxies are displayed as black error bars. For the I-type cosmic spherules 1SD error bars are displayed in blue. The average SUT data point is marginally shifted along the time axis to avoid overlapping the two source data points (SUT11-3 and SUT16-1).

The analytical precision of this dataset is ±0.08‰ for the Δ’17O of iron oxides as small as 1 µg (10 nmol O2), resulting in pCO2 reconstructions with an uncertainty between ±180 and ±370 ppmv. The precision of the Δ’17O analysis dominates the reconstruction precision because it is directly translated into the precision of the reconstructed Δ’17O of atmospheric O2 (Eq. 3), which in turn provides information on the atmospheric CO2 reservoir (pCO2) and bio productivity (GPP).

Existing proxy collections include δ13C in liverworts, alkenones (phytoplankton) or paleosols, leaf stomata density and index of land plants and boron isotopes in foraminifers33,36,37. The pCO2 uncertainty in this study (±180–370 ppmv) is of the same magnitude of the average uncertainty of existing proxies for the Miocene and Cretaceous, which range from \(\begin{array}{c}+120\\ -70\end{array}\) ppmv in the Miocene to \(\begin{array}{c}+380\\ -150\end{array}\) ppmv for the Upper Cretaceous33,36,37. The weakness of most existent proxies is that they become less available and increasingly imprecise (several thousand ppmv) with geological age and increasing pCO2 (Fig. 5). The biological and geochemical pCO2 proxy uncertainties result, next to diagenetic loss of bio-geochemical tracers, from model dependent error estimates that are strongly influenced by calibration of fossil measurements to modern counterparts and imprecise input parameters of transfer functions33,38. Corresponding fits (LOESS) based on these proxies, therefore, become increasingly imprecise and are not used for time intervals older than 420 million years (i.e., Devonian).

Our study shows the feasible reconstruction of pCO2 from the Δ’17O of a single, intact I-type cosmic spherule across various time intervals (Miocene and Cretaceous) with a consistent precision of < ± 400 ppmv. This degree of precision should extend throughout the entire Phanerozoic and even throughout the Precambrian, given the enduring geological preservation of I-type cosmic spherules, with the oldest record of unaltered I-type cosmic spherules dating back to 2.7 Ga3.

Potential and limitations of the atmospheric proxy

The oxygen isotope analytical method used in this study suits samples as small as 1 µg or 10 nmol of O2, challenging the analytical limits of the laser fluorination technique for micrometer-sized cosmic spherules23. The ~1 µg samples allow for an external reproducibility of ±0.04‰ for Δ’17O23, close to the 0.03‰ internal precision of a gas-source isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Supplementary Fig. S3), potentially reducing the pCO2 reconstruction uncertainty to ±90–185 ppmv compared to ±180–370 ppmv reported in this study.

Carbonate rocks are currently the sole source of I-type cosmic spherules unaffected by terrestrial weathering3,4,5, a conclusions supported our findings. Targeting carbonate host rocks can yield larger populations of pristine spherules, notably reducing uncertainty in pCO2 reconstructions, as larger sample quantities allow for considerably improved precision. For instance, sampling 10 pristine spherules could achieve an average Δ’17O uncertainty better than 0.025‰, leading to pCO2 reconstructions of ~50 ppmv, irrespective of the examined time interval.

We demonstrated that even diagenetically altered fossil I-type cosmic spherules (low δ18O-population) remain useful for paleo-atmosphere reconstruction, because they still contain some oxygen (10 – 35%) of atmospheric origin. Low Δ‘17O values of altered fossil specimens indicate a lower Δ‘17O of the atmospheric O2 component. For example, altered Middle Triassic spherules show Δ‘17O values as low as −0.48 ± 0.08‰ (Fig. 2). Accounting for diagenetic influences (i.e., substitution of atmospheric oxygen with oxygen from meteoric water), the unaltered endmember Δ‘17O might be as low as approximately −1.20 ± 0.08‰ (Fig. 2). The investigated Silurian spherule with a Δ‘17O of −0.20‰ is indicative of a higher Δ‘17O of atmospheric O2 with respect to the Triassic specimens. However, more unaltered spherules should be isolated in order to confirm the conclusion of modern-like Δ’17O of the Silurian atmosphere.

Pristine fossil I-type cosmic spherules that preserved the entire atmospheric O2 signal are, however, the primary target for paleo-atmospheric reconstruction. The current analytical capabilities provide pCO2 estimates from one individual unaltered spherule that are comparable or exceeding other existing CO2 proxy and model uncertainties especially with increasing geologic age33,34,35. The extraction of unaltered I-type cosmic spherules from 2.7 Ga old carbonates3 is promising in this context. The oxygen isotope composition of unaltered I-type cosmic spherules has the potential to trace paleo-atmospheric processes further back in time than any other existing proxy.

Methods

Samples

We included I-type cosmic spherules from ten localities in this study (Supplementary Table S1). The sedimentary host rocks include marl, limestone, dolocrete, arkosic sandstone and rock salt (halite). A modern Antarctic I-type cosmic spherule from the TAM collection (sediment trap #65) was included as a reference sample21. The I-type cosmic spherules in this study span Silurian to Quaternary ages (Supplementary Table S1), covering a wide range of discrete points within the Phanerozoic Eon4,5,21,39,40,41,42,43,44. Varying amounts of rock between 6 kg and 49 kg were collected from each locality (Supplementary Table S2), depending on the expected number of I-type cosmic spherules in the respective rock type. I-type cosmic spherules from existing collections were also examined in this study4,5.

Micrometeorite extraction

The I-type cosmic spherules were extracted with methods adjusted to the respective host rocks. We focused on collecting the magnetic fraction of each rock for the subsequent search for I-type cosmic spherules with an optical microscope. The magnetic fraction in all the selected lithologies makes up a small proportion of the total rock mass. Possible I-type cosmic spherules can be concentrated efficiently in small magnetic fraction quantities from a large sample quantity (Supplementary Table S2).

The I-type cosmic spherule candidates were identified microscopically (round shape and dendritic texture) and first mounted on double sided tape. That setup was used for micro X-ray fluorescence (µXRF) investigation of the I-type cosmic spherule candidates. The candidates were subsequently mounted and carbon coated on pin stubs for imaging and chemical analysis of the micrometeorite surfaces under the scanning electron microscope (SEM).

Micro X-ray fluorescence

Geochemical investigations were conducted at the University of Göttingen, Germany. The I-type cosmic spherules were scanned for their Mn to Fe ratio and possible Ni content with a Bruker M4 TORNADO µXRF. The µXRF was equipped with an X-ray tube with a rhodium target. We used the µXRF under low-vacuum conditions of 20 mbar, an acceleration voltage of 50 kV and 200 µA beam current. A minimum spot size of 20 µm and acquisition times of 120 s were selected for analysis. We used precidur® 11SMn30Pb30 steel as reference with a Mn concentration of 1.03 ± 0.02 wt%. We also analyzed nine modern Antarctic I-type cosmic spherules with low Mn concentrations of 0.02 ± 0.02 wt% and Ni concentrations of 2.4 ± 1.4 wt% multiple times within each measurement sequence. The weight percentages were calculated semi-quantitatively using a recent oxide calibration.

Scanning electron microscopy

The SEM analyses were carried out using a JEOL JSM-IT500 InTouchScope™ equipped with a Tungsten source and an Ultim Max EDX detector from Oxford Instruments allowing for semi-quantitative EDX analyses. Analyses were performed under high-vacuum at a working distance of 11 mm. The acceleration voltage was set to 15 kV with a beam current of 20 nA and a focused beam. The SEM was used for the acquisition of secondary electron images of the I-type cosmic spherule candidates as well as EDX spot analysis on their surfaces to investigate the size, texture, mineralogy and chemical composition. The SEM data was used to verify the extraterrestrial origin of the I-type cosmic spherules as well as to identify weathering and diagenetic alteration signatures. The detection limits as well as elemental uncertainties varied between 0.04 and 0.21 wt% for µXRF and SEM measurements. The efficiency of both µXRF and SEM in tracing Mn in I-type cosmic spherules is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Oxygen isotope analysis

The samples were removed from the pin holder and stored in individual glass vials in preparation for triple oxygen isotope analysis of the identified I-type cosmic spherules. In order to remove residual glue and sediment sticking at the samples, the spherules were gradually cleaned with acetone, ethanol and pure grade H2O. The samples were stored overnight in a drying cabinet at 50 °C to remove residual moisture.

We used laser fluorination oxygen extraction and purification in combination with gas chromatography and continuous flow isotope ratio monitoring gas spectrometry (IRMS) for triple oxygen isotope analyses at the University of Göttingen, Germany. For continuous flow IRMS analyses a customized Thermo Scientific™ GasBench II coupled with a Thermo Scientific™ MAT 253 gas source IRMS was used. The oxygen isotope analyses followed the procedure described by Zahnow et al.23 with adjustments made to improve precision with regard to samples in the lowest microgram mass range (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Data was reduced and corrected according to the procedure for continuous flow IRMS analysis23. Aliquots as well as bulk I-type cosmic spherule samples, investigated for their triple oxygen isotope composition, had masses ≥1 µg and calculated oxygen amounts ≥8 nmol. The lower limit of the applied continuous flow IRMS oxygen isotope analysis method is ~10 nmol of O223. Samples with O2 amounts <10 nmol experience a non-linear drift in Δ’17O, due to the low signal intensity at the IRMS. We filtered the Δ’17O for O2 amounts > 10 nmol in order to acquire a robust data set. We used UWG-2 garnet as our primary standard with δ18OVSMOW = 5.75‰ and Δ’17O0.528 = −0.059‰45,46. As the matrix matched secondary standard, we used magnetite 070113 with δ18OVSMOW = 9.9‰ and Δ’17O0.528 = -0.09‰11,23,47. The external reproducibility is reported as 1SD of a single analysis and was adopted for all samples based on 27 UWG-2 garnet and 16 magnetite 070113 analyses between 1 and 9 µg or 13 to 119 nmol O2 (Supplementary Table S4 and Fig. S5). The external reproducibility in δ18O was 0.6‰ and in Δ’17O it was 0.08‰.

Iron isotope analysis

We developed a novel approach by employing wet plasma MC-ICP-MS for Fe fluorides, instead of in situ laser ablation on intact I-type cosmic spherules used in earlier studies11,48. Utilizing Fe fluorides remaining after oxygen isotope analysis was crucial due to the low masses of individual fossil I-type cosmic spherules, often approaching or falling below the analytical limit of the continuous flow IRMS method (~1 µg or 10 nmol O2). The goal was to maximize the analysis of individual micrometeorites by initially utilizing the entire sample mass for oxygen isotope analysis.

Iron fluorides that remained in the sample pits after laser fluorination oxygen extraction were collected and stored in Eppendorf vials. The fluorides were dissolved in 0.5 mL of 9 M HCl for extraction of Fe. The digested samples were taken up in 1 ml of 9 M HCl, and pure Fe fractions were obtained by passing the solution through AG MP-1 (100-200 mesh) resin in 2 ml Bio-Rad® columns49.

Iron isotope measurements were performed at the University of Hannover, Germany using a Thermo-Finnigan Neptune multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS). For sample introduction, the instrument was equipped with a quartz glass spray chamber (double pass Scott design), a PFA nebulizer (~100 µl min−1 uptake rate, Elemental Scientific), a Ni sampler and a Ni X-type skimmer cone. Masses 53Cr, 54Fe, 56Fe, 57Fe, (58Fe) 58Ni and 60Ni were detected simultaneously following the procedure described in Roebbert et al.49 and Oeser et al.50, respectively.

The accuracy and precision of the Fe isotope analysis was monitored using an in-house standard (Fe salt from ETH Zurich, Switzerland). Measured at the intensity above 8 V on 56Fe, the average δ56Fe and δ57Fe values of our in-house standard relative to IRMM-014 were −0.74 ± 0.03‰ (mean ± 2SD, n = 22) and −1.05 ± 0.06‰ (mean ± 2SD, n = 22) respectively, in a good agreement with previously published values (δ56Fe = −0.72‰, δ57Fe = −1.06‰51,52,53). Larger uncertainties of δ56Fe = −0.79 ± 0.21‰ (mean ± 2SD, n = 6) and δ57Fe = −0.92 ± 0.27‰ (mean ± 2SD, n = 6) occurred for the in-house standard measured at ~3 V (~0.3 ppm Fe) on 56Fe. We excluded micrometeorite data analyzed at lower intensities than 3.5 V on 56Fe, to avoid a non-linear drift in Δ‘56Fe.

Test measurements were conducted on Fe fluorides using magnetite standard material (magnetite 070113) and a large modern Antarctic I-type cosmic spherule (MA-9). This allowed us to confirm the efficacy of Fe fluorides for iron isotope analysis and to quantify the fractionation introduced by the laser fluorination oxygen extraction procedure (Supplementary Table S5 and Fig. S6). The resulting uncertainty from the Fe fluoride procedure on iron isotope analyses is larger than the internal analytical errors derived from the Fe in-house standard. We adopted the 2SD uncertainty of fluoride measurements of magnetite 070113 standard with δ56Fe = 0.9 ± 0.8‰ (mean ± 2SD, n = 6), δ57Fe = 1.4 ± 1.3‰ (mean ± 2SD, n = 6) and Δ’56Fe = −0.02 ± 0.04‰ (mean ± 2SD, n = 6) for all samples. The uncertainties in δ56Fe and δ57Fe are correlated, thus the uncertainty in Δ‘56Fe is smaller. The determined iron isotope values for magnetite 070113 are in good agreement with published values from laser-ablation MC-ICP-MS measurements (δ56Fe = 0.86‰, δ57Fe = 1.26‰, Δ’56Fe = 0.00‰11).

Data availability

The chemical and oxygen and iron isotope data that support the findings of this study are available in the Göttingen Research Online data repository with the identifier https://doi.org/10.25625/M0BRRB.

References

Rubin, A. E. & Grossmann, J. N. Meteorite and meteoroid: new comprehensive definitions. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 45, 114–122 (2010).

Love, S. G. & Brownlee, D. E. Heating and thermal transformation of micrometeoroids entering the Earth’s atmosphere. Icarus 89, 26–43 (1991).

Tomkins, A. G. et al. Ancient micrometeorites suggestive of an oxygen-rich Archaean upper atmosphere. Nature 533, 235–238 (2016).

Suttle, M. D. et al. Fossil micrometeorites from Monte dei Corvi: searching for dust from the Veritas asteroid family and the utility of micrometeorites as a palaeoclimate proxy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 355, 75–88 (2023).

Suttle, M. D. & Genge, M. J. Diagenetically altered fossil micrometeorites suggest cosmic dust is common in the geological record. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 476, 132–142 (2017).

Taylor, S. & Brownlee, D. E. Cosmic spherules in the geologic record. Meteoritics 26, 203–211 (1991).

Onoue, T., Nakamura, T., Haranosono, T. & Yasuda, C. Composition and accretion rate of fossil micrometeorites recovered in Middle Triassic deep-sea deposits. Geology 39, 567–570 (2011).

van Ginneken, M. et al. Micrometeorite collections: a review and their current status. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 382, 20230195 (2024).

Brownlee, D. E. Cosmic dust: Collection and research. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 13, 147–173 (1985).

Pack, A. et al. Tracing the oxygen isotope composition of the upper Earth’s atmosphere using cosmic spherules. Nat. Commun. 8, 15702 (2017).

Fischer, M. B. et al. I-Type cosmic spherules as proxy for the Δ′ 17 O of the atmosphere—a calibration with quaternary air. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 36, e2020PA004159 (2021).

Engrand, C. et al. Isotopic compositions of oxygen, iron, chromium, and nickel in cosmic spherules: Toward a better comprehension of atmospheric entry heating effects. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 5365–5385 (2005).

Young, E. D., Yeung, L. Y. & Kohl, I. E. On the Δ17 O budget of atmospheric O2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 135, 102–125 (2014).

Luz, B., Barkan, E., Bender, M. L., Thiemens, M. H. & Boering, K. A. Triple-isotope composition of atmospheric oxygen as a tracer of biosphere productivity. Nature 400, 547–550 (1999).

Bender, M., Sowers, T. & Labeyrie, L. The Dole Effect and its variations during the last 130,000 years as measured in the Vostok Ice Core. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 8, 363–376 (1994).

McKinney, C. R., McCrea, J. M., Epstein, S., Allen, H. A. & Urey, H. C. Improvements in mass spectrometers for the measurement of small differences in isotope abundance ratios. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 21, 724 (1950).

Miller, M. F. & Pack, A. Why Measure 17 O? Historical Perspective, triple-isotope systematics and selected applications. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 86, 1–34 (2021).

Pack, A. Isotopic traces of atmospheric O2 in rocks, minerals, and melts. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 86, 217–240 (2021).

Sharp, Z. D. & Wostbrock, J. A. Standardization for the triple oxygen isotope system: waters, silicates, carbonates, air, and sulfates. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 86, 179–196 (2021).

Young, E. D., Galy, A. & Nagahara, H. Kinetic and equilibrium mass-dependent isotope fractionation laws in nature and their geochemical and cosmochemical significance. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 66, 1095–1104 (2002).

Suttle, M. D. & Folco, L. The extraterrestrial dust flux: size distribution and mass contribution estimates inferred from the transantarctic mountains (TAM) micrometeorite collection. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 125, e2019JE006241 (2020).

Feng, H. et al. Internal structure of type I deep-sea spherules by X-ray computed microtomography. Meteorit. Planet Sci. 40, 195–206 (2005).

Zahnow, F., Stracke, T., Di Rocco, T., Hasse, T. & Pack, A. High precision triple oxygen isotope composition of small size urban micrometeorites indicating constant influx composition in the early geologic past. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 58, 1567–1579 (2023).

Graham, T. X. V. I. I. On the molecular mobility of gases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 153, 385–405 (1863).

Nozaki, W., Nakamura, T., Iida, A., Matsuoka, K. & Takaoka, N. Trace element concentrations in iron type cosmic spherules determined by the SR-XRF method. Antarct. Meteor. Res. 12, 199–212 (1999).

Wang, K. et al. Homogeneous distribution of Fe isotopes in the early solar nebula. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 48, 354–364 (2013).

Beard, B. L. & Johnson, C. M. High precision iron isotope measurements of terrestrial and lunar materials. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 1653–1660 (1999).

Herwartz, D. Triple oxygen isotope variations in Earth’s crust. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 86, 291–322 (2021).

Zheng, Y.-F. Calculation of oxygen isotope fractionation in metal oxides. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 55, 2299–2307 (1991).

Levin, N. E., Raub, T. D., Dauphas, N. & Eiler, J. M. Triple oxygen isotope variations in sedimentary rocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 139, 173–189 (2014).

Beerling, D. Quantitative estimates of changes in marine and terrestrial primary productivity over the past 300 million years. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 266, 1821–1827 (1999).

Mills, B. J., Krause, A. J., Jarvis, I. & Cramer, B. D. Evolution of atmospheric O2 through the phanerozoic, revisited. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 51, 253–276 (2023).

Foster, G. L., Royer, D. L. & Lunt, D. J. Future climate forcing potentially without precedent in the last 420 million years. Nat. Commun. 8, 14845 (2017).

Berner, R. A. GEOCARBSULF: A combined model for Phanerozoic atmospheric O2 and CO2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 5653–5664 (2006).

Royer, D. L., Donnadieu, Y., Park, J., Kowalczyk, J. & Godderis, Y. Error analysis of CO2 and O2 estimates from the long-term geochemical model GEOCARBSULF. Am. J. Sci. 314, 1259–1283 (2014).

Royer, D. L., Berner, R. A. & Beerling, D. J. Phanerozoic atmospheric CO2 change: evaluating geochemical and paleobiological approaches. Earth Sci. Rev. 54, 349–392 (2001).

Royer, D. L., Berner, R. A., Montañez, I. P., Tabor, N. J. & Beerling, D. J. CO2 as a primary driver of Phanerozoic climate. GSA Today 14, 4 (2004).

Beerling, D. J., Fox, A. & Anderson, C. W. Quantitative uncertainty analyses of ancient atmospheric CO2 estimates from fossil leaves. Am. J. Sci. 309, 775–787 (2009).

Niebuhr, B. & Reich, M. Exkursion 7. Das Campan (höhere Ober-Kreide) der Lehrter Westmulde bei Hannover. In Geobiologie 2. 74. Jahrestagung der Paläontologischen Gesellschaft in Göttingen, 02. bis 08. Oktober 2004, Exkursionen und Workshops (eds Reitner, J., Reich, M. & Schmidt, G.) 193–210 (Universitätsverlag Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2004).

Arp, G., Hoffmann, V.-E., Seppelt, S. & Riegel, W. Exkursion 6: Trias und Jura von Göttingen und Umgebung. In Geobiologie 2. 74. Jahrestagung der Paläontologischen Gesellschaft in Göttingen, 02. bis 08. Oktober 2004, Exkursionen und Workshops (eds Reitner, J., Reich, M. & Schmidt, G.) 147–192 (Universitätsverlag Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2004).

Salger, M. & Schmidt, H. Die Forschungsbohrung Eschertshofen 1981 (Vorläufige Mitteilung). Geol. Bavarica 83, 145–161 (1982).

Zhang, Y., Krause, M. & Mutti, M. The formation and structure evolution of Zechstein (Upper Permian) salt in Northeast German Basin: a review. OJG 03, 411–426 (2013).

Gebhart, U. Mikrofazies and Paläontologie biogener Karbonate der Unteren Mansfelder Schichten (Oberkarbon, Stefan). Hallesches Jahrb Geowiss. 13, 5–21 (1988).

Miller, C. G. Ostracode and conodont distribution across the Ludlow/Pridoli boundary of Wales and the Welsh Borderland. Palaeontology 38, 341 (1995).

Miller, M. F., Pack, A., Bindeman, I. N. & Greenwood, R. C. Standardizing the reporting of Δʹ17 O data from high precision oxygen triple-isotope ratio measurements of silicate rocks and minerals. Chem. Geol. 532, 119332 (2020).

Valley, J. W., Kitchen, N., Kohn, M. J., Niendorf, C. R. & Spicuzza, M. J. UWG-2, a garnet standard for oxygen isotope ratios: Strategies for high precision and accuracy with laser heating. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 5223–5231 (1995).

Pack, A. & Herwartz, D. The triple oxygen isotope composition of the Earth mantle and understanding Δ17O variations in terrestrial rocks and minerals. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 390, 138–145 (2014).

Lampe, S. et al. Decoupling of chemical and isotope fractionation processes during atmospheric heating of micrometeorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 324, 221–239 (2022).

Roebbert, Y. et al. Fractionation of Fe and Cu isotopes in acid mine tailings: modification and application of a sequential extraction method. Chem. Geol. 493, 67–79 (2018).

Oeser, M., Weyer, S., Horn, I. & Schuth, S. High-precision Fe and Mg isotope ratios of silicate reference glasses determined in situ by femtosecond LA - MC - ICP - MS and by solution nebulisation MC - ICP - MS. Geostand. Geoanalytic Res. 38, 311–328 (2014).

Kiczka, M. et al. Iron speciation and isotope fractionation during silicate weathering and soil formation in an alpine glacier forefield chronosequence. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 5559–5573 (2011).

Schuth, S., Hurraß, J., Münker, C. & Mansfeldt, T. Redox-dependent fractionation of iron isotopes in suspensions of a groundwater-influenced soil. Chem. Geol. 392, 74–86 (2015).

Kusonwiriyawong, C. et al. Isotopic variation of dissolved and colloidal iron and copper in a carbonatic floodplain soil after experimental flooding. Chem. Geol. 459, 13–23 (2017).

Surma, J., Assonov, S. & Staubwasser, M. Triple oxygen isotope systematics in the hydrologic cycle. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 86, 401–428 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—Project number PA909/25-1. This research is also funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. This work is supported by ERC grant “KinO”, Project 101088020. We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds/transformative agreements of the Göttingen University. The use of equipment in the Göttingen laboratory for correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (GoeLEM) is gratefully acknowledged. D. Kohl is acknowledged for the support with the oxygen isotope analysis. We thank the Bavarian Environmental Agency (Hof, Germany) and Gernot Arp (University of Göttingen, Germany) for providing the Triassic rock core samples. We thank G. Miller (of NHM, London) for the supply of a micropaleontology acid-digestion residue from which the two Silurian fossil micrometeorites were extracted. We thank the Royal Society for fieldwork funding (grant number RGS-R1-221005) which made the collection of Miocene micrometeorites possible. Funding for micrometeorite research at the University of Pisa is facilitated by the Italian Programma Nazionale delle Ricerche in Antartide (PNRA) under grant number PNRA16 00029. Planetary materials study at the University of Pisa is also supported by PRIN2022 Cosmic Dust II, ID# 2022S5A2N7 and ASI-MUR SpaceitUp! ID# 2024-5-E.0 - CUP n. I53D24000060005 projects. Antarctic micrometeorites studied in this work were collected during the 2017 Programma Nazionale delle Ricerche in Antartide (PNRA) expedition. Finally, we thank Alireza Bahadori and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero for editorial handling and the reviewers for their valuable suggestions and comments.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.Z.: conceptualization, visualization, methodology, investigation, evaluation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. M.D.S.: investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. M.L.: methodology, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. S.W.: methodology, writing—review & editing. T.D.R.: methodology, writing—review & editing. L.F.: conceptualization, supervision, writing—review & editing. A.P.: conceptualization, visualization, supervision, writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Guido Jonker and Huiming Bao reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Alireza Bahadori and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zahnow, F., Suttle, M.D., Lazarov, M. et al. Traces of the oxygen isotope composition of ancient air in fossilized cosmic dust. Commun Earth Environ 6, 577 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02541-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02541-5