Abstract

Planktonic foraminifera are key contributors to the oceanic carbon cycle. In pelagic environments, carbonate production by planktonic biomineralizers regulates ocean-atmosphere carbon dioxide exchange and exports surface carbon to the deep ocean. Here we compare shell traits of three planktonic foraminifera species from the central Atlantic with a suite of environmental parameters to discern the factors underlying their variations. Our analysis revealed that calcification in foraminifera is associated with seawater density and depends on species habitat depth, whereas foraminifera bulk shell densities may serve as a seawater density proxy, regardless of species. We observe that their shell weights increased with habitat depth, enabling the living cells to adjust their overall density to match that of the surrounding liquid. This suggests that calcification in nonmotile organisms has a buoyancy regulatory function and will respond to the anthropogenically driven reductions in ocean density (oceanic rarefication), with potential consequences for the carbon cycle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Planktonic foraminifera are marine protists that house their unicellular bodies within sophisticated calcite shells and are distributed globally in oceanic surface waters. They are relatively simple unicellular organisms that cannot actively swim; they can only control their buoyancy1,2. They occupy surface to subthermocline depths in the pelagic ocean, with regional differences in food and seawater properties constraining their latitudinal, temporal and depth distributions3. Most modern species are primarily epipelagic, although some descend into mesopelagic waters for reproduction or seasonal survival4,5. The exact mechanism by which planktonic foraminifera control their position in the water column to attain neutral buoyancy is not fully understood. However, observations suggest that species-specific buoyancy adjustments occur, concentrating populations of each species at specific depths6. Although positive buoyancy can be achieved by low-density metabolites like gasses and lipids2,7 or osmolytes8, negative buoyancy adjustment mechanisms remain poorly studied. The ability of foraminifera to control their sinking rates and maintain depth-specific habitats may be linked to their biomineralization processes.

Planktonic foraminifera have been thought to regulate their shell masses in response to ambient carbonate chemistry9. However, recent studies challenge this assumption, showing that calcification is not directly controlled by ocean acidity10,11,12, suggesting that other environmental factors play a more dominant role. Since foraminifera can calcify by maintaining chemical gradients with their ambient environment13,14, understanding what drives changes in shell mass requires considering the fundamental role of the shell itself. In addition to providing cellular support and protection from the biological, physical and chemical stresses of the ocean15, increasing organismal density is one of the adaptive roles of skeletal calcification, serving as part of a buoyancy regulation mechanism16,17,18. It has been proposed that foraminifera modify their shape and size, influencing their weight and overall density (i.e., the ratio between calcite and protoplasm), to adapt their hydrodynamic behaviour in response to changes in water conditions19,20,21, a strategy that has also been confirmed in other plankton taxa22. Indeed, foraminifera were found to increase their shell mass with depth23, demonstrating an active, biologically mediated carbon sequestration mechanism. Considering that planktonic foraminifera constitute a major fraction (~32–80%) of deep-sea carbonate sediments24, understanding their biomineralization strategies is critical for understanding the history of the marine carbon cycle and hence the mechanisms regulating atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations.

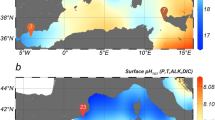

In this study, we conducted physiochemical analyses on the shells (300–350 μm in size) of three planktonic foraminifera species, namely Globigerinoides ruber albus sensu stricto (s.s.), Trilobatus trilobus, and Globorotalia truncatulinoides, collected from the central Atlantic surface sediment along the mid-Atlantic ridge (Fig. 1), spanning habitats from shallow to subthermocline depths. To investigate the factors influencing shell mass and calcification, we conducted Mg/Ca analyses to estimate species-specific apparent calcification depths and paired those with stable oxygen isotope (δ18O) measurements to reconstruct the surrounding seawater density. In addition to shell weights, we used X-ray microcomputed tomographic (μCT) data to examine physical traits such as skeletal percentage, thickness, volume, and bulk density (volume-normalized shell weights). Bulk shell density (BSD), as used here, is defined as the shell weight divided by the “cell” total volume derived from μCT imaging, which is the volume a living organism would occupy if the internal voids of the (fossil) shell were fully filled with protoplasm. These six shell traits were statistically analysed via linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) and compared with geochemically reconstructed and in situ physical oceanographic parameters, as well as carbonate system properties (alkalinity, CO32−), to evaluate correlations between environmental factors and calcification. Our findings indicate that shell weights and bulk shell densities (BSDs) are directly related to ambient seawater density, suggesting that planktonic foraminifera shells serve as proxies for seawater density throughout the water column. Additionally, these results imply that the ongoing ocean warming, via thermal expansion, and freshening from ice melt, which lead to oceanic rarefication (lower seawater density), may lessen the future calcification requirements of planktonic calcifiers.

Results

Interspecies shell response to environmental parameters

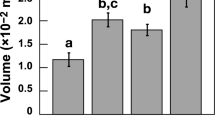

The three species exhibited significant (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 > 28.7; Benjamini and Yekuetli adjusted p < 0.01 for all comparisons) morphological differences across all six traits (Fig. 2). Many of these traits covary strongly (Supplementary Table 1), and across species, display similar relationships with environmental conditions.

For all six traits, the linear mixed-effects model (LMM) incorporating only seawater density consistently yielded the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) values or was indistinguishable from the best-performing model (Table 1). For all traits except test thickness, the density model performed roughly as well as the model incorporating both density and salinity (density + salinity model, Table 1). For “potential cell” volume, the density model, temperature model, salinity model, and salinity + [CO32−] models performed equally well, whereas for shell weight, the three models that incorporated density were equivalent. For test volume, the null model, incorporating only [CO32−] and temperature, performed equally well as the full model and density model. Using the density + salinity model, shell weight, BSD, test volume, test thickness, and test percentage were all positively associated with density (all t > 2.31, the mean effect size ranged from β = 0.40 to β = 0.96; Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that individuals with heavier and thicker tests were found in denser waters (Fig. 3). “Cell” volume, however, was not significantly associated with density (β = −0.19, t = −1.00; Supplementary Fig. 1). Although salinity showed some effect on shell weight (β = 0.14, t = 2.00) and BSD (β = 0.13, t = 1.94), it was not significantly related to other traits (all other |t | <1.32). These findings challenge the common assumption that carbonate ion availability is the dominant control on calcification9 and instead support seawater density as a primary driver.

Plots A–C correspond to raw shell mass, normalized mass, and total volume, respectively. Plots D–F show CT-derived digital traits: D test volume, E test thickness, and F test percentage. The shaded areas lie between the 5% and 95% confidence intervals of the linear model coefficients. Asterisks denote the species with responses to density significantly different (i.e., stronger) from those of G. ruber (interaction effect p < 0.05). All values were scaled to unit variance to enable comparisons between the traits.

The LMMs revealed a general effect of seawater density on the calcification of foraminifera across all three species. However, the magnitude of this effect varied between each species and trait individually (Fig. 3). The random effect term (differences in mean trait values among the species) accounted for the majority of variance in the density + salinity LMMs for shell weight (82%), “cell” volume (71%), and test volume (60%). For test thickness and test percent, the differences between traits among species were outstripped by the effect of the environmental characteristics, accounting for 13% and 9.2% of the model variance, respectively. Importantly, BSD was not significantly influenced by species differences (differences between species traits not accounted for by our environmental predictors were negligible), indicating that it serves as a species-independent proxy for seawater density. This suggests that BSD-based reconstructions could provide reliable insights into past ocean density gradients across species.

Ocean density had a significantly greater effect on the test thickness of T. trilobus (p = 0.03) than it did on the other two species (Fig. 3). In addition, the test volumes of T. trilobus increased with increasing density, whereas the test volume of G. truncatulinoides and G. ruber did not substantially vary with increasing density. Finally, although the “potential cell” volume was insignificantly related to density across and within the three species, each species individually presented different relationships, with G. ruber and (to a lesser extent) G. truncatulinoides showing a decrease in “cell” volume with increasing density and T. trilobus showing no relationship.

Species specific calcification response to seawater density

The relationships between surface ocean density, shell weights and bulk shell densities, as identified previously (Fig. 3A, B), are presented unscaled in Fig. 4 for each species individually, without accounting for the other covariates (salinity and [CO32−]). Furthermore, the formulas derived from the regression analysis are given in each graph and may be used to convert species-specific shell weights and overall BSDs into ambient seawater densities. These strong correlations support the role of seawater density as a key driver of foraminiferal calcification, rather than carbonate chemistry alone.

A Correlation between bulk shell density (BSD) of planktonic foraminifera and ambient seawater density. Highlighted G. truncatulinoides data points denote a group; B–D species-specific shell weights with respect to seawater density. The data points are color-coded according to their site. Asterisks in the G. ruber and T. trilobus graphs mark samples of relatively enhanced dissolution. The gray shaded areas are σθ horizons from atlases at species-specific apparent calcification depths. Discrepancies between the atlases’ σθ range and geochemically reconstructed densities may arise from “vital effects” on δ18Oshell (see discussion). The 1σ confidence is depicted at the lower right of each graph.

Since buoyancy force depends on the volume of displaced fluid, total cell volume plays a crucial role in regulating depth positioning in plankton22. Larger cells displace more seawater, increasing buoyant force and reducing sinking tendency, even in heavily calcified species. This explains why T. trilobus, despite having shell weights nearly as heavy as G. truncatulinoides (Fig. 2A), remains in surface waters in the region25. Its greater total “cell” volume (Fig. 2C) offsets its calcification, allowing it to stay afloat at depths similar to G. ruber. When normalized to total volume (BSDs), T. trilobus exhibits density traits consistent with surface-dwelling forms, aligning more closely with G. ruber (Fig. 2B). This pattern is further supported by digital tomographic data alone (Fig. 2E, F), reinforcing that T. trilobus functionally aligns with surface-dwelling foraminifera.

Planktonic foraminifera BSDs (volume-normalized shell weights) show a highly significant, species-independent correlation with seawater density (Fig. 4A), reinforcing their potential use as a density proxy. The G. ruber test mass shows strongest correlation to density among globigerinids, whereas T. trilobus shows a slightly weaker relationship, likely due to differential dissolution effects, which have been observed to impact T. trilobus more significantly than other species26. In these two groups, the heavier specimens are found in the saltier and thus denser subtropical gyre waters, whereas the lightest specimens carry the geochemical signal of the lighter equatorial waters.

The calcification data for G. truncatulinoides do not follow a latitudinal trend, as light specimens are present in both equatorial and subtropical areas. However, the variations in shell weights and water densities are better explained when two distinct population groups are considered, as has been previously suggested for these central Atlantic samples27. The average G. truncatulinoides shell weight remains stable at 31.2 μg across both groups but analysing them separately reveals key differences. The first group shows an exceptionally strong correlation (r2 = 0.95), with weights varying between 27.6 and 35 μg. The second group also shows a strong correlation (r2 = 0.76) but has less weight variability, ranging from 28.5 to 33.2 μg (Fig. 4D). This suggests that while seawater density is a dominant control, additional ecological or physiological factors may influence the calcification response within distinct G. truncatulinoides populations. The divergence between the two populations lies in the geochemically reconstructed seawater densities but diminishes when shell weights are normalized to the total specimen (“potential cell”) volumes (Fig. 4A). This normalization reinforces BSD as a species-independent seawater density proxy, reducing interspecies variability.

Overall, the rate at which foraminifera species increase their shell weight per unit change in water density (i.e., the slope of the regression line) is species-specific and appears to be dependent on habitat depth, increasing from the surface-dwelling G. ruber to the deeper-dwelling G. truncatulinoides. These findings further support the hypothesis that foraminiferal calcification serves as an adaptive buoyancy regulation mechanism, rather than being solely controlled by surface ocean carbonate chemistry.

Discussion

Planktonic foraminifera shell masses as indicators of seawater density

The present analysis revealed a general influence of seawater density on the calcification of planktonic foraminifera across all three species studied. Compared with previous work9,28, in this study, we assess multispecies modern shell traits across ocean-wide oceanographic gradients, we do not find an overall dependency of the various shell traits on [CO32−]. Instead, all the various shell traits related to calcification intensity, such as test percentage, weight, thickness, and BSD, respond primarily to seawater density, with the magnitude of this response varying among the species. In addition, the significant effects of density on “potential cell” volume, shell weight, and shell density, even when trait differences across species are considered, indicate that planktonic foraminifera may adapt to in situ oceanic environmental conditions. While traits involving shell weight measurements may be subject to detritus contamination23, traits derived from 3D X-ray tomographic data analyses, such as test thickness and test percentage, are more precise species-specific indicators of calcification. The strong correlations between independently derived in situ oceanographic data and geochemical foraminifera shell information corroborate hydrography as a key driver of plankton calcification in the open ocean.

Planktonic foraminifera shell weights are valuable, easily measured biological indicators in geological records and are shown here to respond to seawater density changes at both the intra- and interspecies levels. The shell weights (Fig. 2A) and volume-normalized shell weights (Fig. 2B) of the different species increased with habitat depth despite the increase in oceanic acidity, reflecting an adaptation to increasing seawater density at greater depths. Similar trends can been observed in coccolithophores, which increase their cell density with depth by raising their particulate inorganic carbon to particulate organic carbon (PIC:POC) ratios (Supplementary Fig. 2). More specifically, the rate at which each species increased its shell weight in response to changes in ambient seawater density (regression slopes; Fig. 4) potentially aligning with the inclination of the pycnocline, with more gradual slopes for the surface mixed-layer species25 and steeper slopes for G. truncatulinoides at the base of the pycnocline27. Discrepancies between geochemically reconstructed (from combined Mg/Ca and δ18O) and in situ densities (Fig. 4) may stem from species-specific “vital effects” that are known to alter the δ18O in foraminifera carbonate, possibly because of the photosynthetic activity of algal symbionts29. Indeed, discrepancies are greater for symbiont-bearing globigerinids30 and smaller for the symbiont-barren G. truncatulinoides. Since the magnitude of these effects remains uncertain31, no corrections were applied here for consistency.

The species-specific shell weight to seawater density relationships reported here (Fig. 4B, C) and elsewhere for upwelling species18 may be simple yet powerful tools for ocean density reconstructions. However, if the slopes of these regression lines follow the structure of the pycnocline, they may vary spatiotemporally (e.g., ref. 32). Alternatively, of particular importance is the strong correlation between foraminifera shell weights normalized to their μCT-derived total volumes (BSDs), and seawater density (Fig. 4A). This strong relationship suggests that BSDs can be used as species-independent seawater density proxies to describe the surface and subsurface structure of the ocean. The BSD-density relationship converged more strongly across species than the other traits did (Fig. 3), which implies that size control may be another strategy used by nonmotile planktonic organisms for depth determination along water density gradients. However, since some species exhibit weak relationships between total “cell” size and seawater density, may indicate that size alone is not the primary factor in buoyancy regulation.

For G. truncatulinoides, the shell weight–density relationship (Fig. 4D) is more complex, aligning with distinct population groups in the central Atlantic27,33. The presence of G. truncatulinoides subspecies has been previously suggested34,35. Although the average shell weight is consistent across both variants, they yield slightly different ambient seawater densities. Since this discrepancy disappears when BSDs are considered, it implies that specimens in the different variants have different volumes. Indeed, the individuals from the two groups differ by ~5% in size (Table 2), despite both being picked from a size-restricted sieve fraction (300-355 μm). This sensitivity suggests that shell weight is a characteristic trait even among intraspecific species variants, indicating that planktonic forms may very precisely regulate shell weight.

Furthermore, G. truncatulinoides shows another slightly distinct calcification response to density than the globigerinids (Fig. 3E). Compared with those of the other two species, the heaviest and densest shells are not always found in denser subtropical gyres. This species is predominantly thermocline-associated4,36, but its habitat depth range varies based on encrustation stage37. In subtropical waters, G. truncatulinoides calcification begins near the surface, with secondary crust deposition occurring at ~700 m. In the tropics, although secondary crusting occurs at shallower depths (~400 m), the calcification of the primary shell takes place below the mixed layer at ~200 m38. Since the geochemical signature of bulk shell analyses represents an integrated signal over the specimen’s ontogenetic depth migration39,40,41, subtropical G. truncatulinoides exhibit lower average Mg/Ca values (Table 2), skewing seawater density reconstructions overall.

Such discrepancies in depth habitats may arise because, in encrusting species like G. truncatulinoides, the gametogenic crust calcite generally has a lower Mg/Ca ratio than earlier ontogenetic calcite, regardless of the depth at which it forms42,43,44. To assess whether potential overestimation of ACDMg/Ca in heavily encrusted specimens, which have inherently lower Mg/Ca ratios, might affect the robustness of our results, we repeated our statistical analyses using, for G. truncatulinoides alone, oceanographic parameters extracted at δ¹⁸O-based apparent calcification depths ACDiso (see Supplementary Note). We found that the main results of the study remain consistent (Supplementary Table 5). The only notable difference was that the relationship between test thickness and density became significantly stronger when using ACDiso of ACDMg/Ca (Supplementary Table 2d).

Changes in the shell weight of planktonic foraminifera have also been associated with variations in seawater salinity23,45. In the present study, salinity was found to exert some influence on the calcification of the mixed layer species G. ruber and T. trilobus (Supplementary Table 2) but not on that of G. truncatulinoides or the present dataset as a whole (Table 1). Salinity is important in determining the depth of the surface mixed layer46, and in this central Atlantic area, there is a subsurface salinity maximum between ~50 and 150 m47,48, below which salinities gradually decrease. However, since planktonic foraminifera calcification follows habitat depth and continues to increase rather than decrease in species residing below the surface mixed layer (e.g., G. truncatulinoides; Fig. 2A, B), this suggests that it is driven by the seawater density gradient rather than the salinity profile. Consequently, since salinity and density co-vary with depth in the mixed layer, surface-dwelling species respond similarly to both parameters, whereas at greater depths (e.g., G. truncatulinoides calcification depths) where these two hydrographic parameters diverge, the effect of density becomes evident.

Foraminiferal shell weight has also often been observed to decrease with increasing sea surface temperature49,50. In this study, such an inverse relationship is weak or absent, particularly for G. truncatulinoides, and this holds for other calcification metrics such as test percentage and BSD (Supplementary Table 2). Across the full dataset, no consistent effect of temperature on shell weight was detected, although slight negative correlations with test percentage and BSD were observed (Table 1). Consistent with previous studies, we interprete these inverse trends to reflect the indirect influence of temperature via its control on seawater density, which in the mixed layer of this region is primarily temperature-driven51. This supports further the broader conclusion that it is the physical property of density rather than temperature alone that better explains patterns of calcification in planktonic foraminifera.

The present analysis demonstrates that variations in planktonic foraminifera shell weight strongly correlate with changes in ambient seawater density, supporting the idea that foraminifera, as nonmotile plankton, adjust their overall density through biomineralization to match that of the surrounding fluid at specific depths along the pycnocline, allowing them to occupy optimal depth habitats. In the absence such adjustment, displacement will occur until the densities of the organism and the surrounding medium equilibrate. This identified dependency of calcification on surface ocean density implies adaptations of calcifying plankton as a response to anthropogenic oceanic warming and freshening due to melting ice sheets. Modest decreases in calcification can lead to pronounced increases in surface ocean alkalinity levels and deepening of the carbonate compensation depth (CCD)52. A decrease in pelagic calcification in response to the ongoing decrease in seawater density could lead to long-term alkalinity build-up in the surface ocean, which has the potential to partially mitigate atmospheric carbon emissions. Furthermore, the active regulation of calcification in planktonic organisms for buoyancy adjustment would require reduced calcification needs in the future ocean, alleviating some of the known pressure exerted by ongoing ocean acidification11.

The above comprehensive analysis aimed to elucidate the relationships between environmental conditions and shell traits within calcifying plankton communities. Along the studied central Atlantic transect, we observed strong relationships between surface ocean density and the degree of biomineralization in three planktonic foraminifera species, which highlights the importance of water density in driving variation and adaptation in these species. Individuals inhabiting denser waters consistently presented heavier, denser, and thicker shells. This correlation persisted across all three species studied, despite their differing depth habitats and life histories, indicating that this effect arises directly from adaptation rather than ecology. Our models suggest that seawater density exerts a stronger influence on foraminifera calcification than other environmental factors such as carbonate ion concentrations, and that their shell weight, particularly bulk shell density (volume normalized shell weight), may serve as a proxy for seawater density. The adaptation of planktonic calcifiers to changes in ocean density may indeed demonstrate aspects of their resilience, while also impacting the surface ocean’s capacity to absorb atmospheric carbon.

Given the significance of these findings and their potential implications for planktonic communities and the carbon cycle, we advocate expanding this type of analysis to a broader set of taxa, including species with less well-defined depth distributions, and incorporating water column–collected specimens to reduce uncertainties inherent in (geochemically) reconstructed seawater densities.

Methods

The present study is based on planktonic foraminifera specimens from a meridional transect of 16 core-top sediment samples spanning from 31°N to 25°S and their locations are situated along either flank of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (Fig. 1). This is a subset of the samples used in previous studies26,27,53, where information about the Holocene age of the samples can be found. We focus on size-restricted (300–355 μm) shells of three planktonic foraminifera species: Globigerinoides ruber albus sensu stricto (commonly referred to as G. ruber white s.s.; marinespecies.org:taxname:1629739), Trilobatus trilobus (a morphotype of T. sacculifer characterized by a three-chambered final whorl and slit-like aperture; marinespecies.org:taxname:1027267), and Globorotalia truncatulinoides (marinespecies.org:taxname:113453).

All specimens used in this study were previously assessed for preservation using μCT scanning23,26. In the present study, the same μCT-scanned tests were geochemically analysed for paired stable oxygen isotope (δ18O) and Mg/Ca measurements. These geochemical data were used to calculate key physical oceanic variables such as temperature, salinity, density and species-specific apparent calcification depths. Based on these data, we estimated species-specific calcification depths, at which corresponding in situ physicochemical oceanographic parameters were obtained from oceanic atlases (as detailed below).

Species with known habitat preferences were selected to span both shallow (surface) and deeper (subthermocline) waters. Shell weight means were calculated from 50 specimens per sample23, while 20 µCT-scanned individuals were used for morphometric analysis. From the scanned individuals 20 G. ruber, 14 T. trilobus, and 14 G. truncatulinoides specimens per location were crushed, homogenized, and then separated for isotope and trace element analyses. The number of specimens analyzed varied according to the species used; however, in all instances approximately 400 μg of carbonate was used for the geochemical analyses. The tests were gently crushed between two glass plates to ensure that all the chambers were opened, and any visible large coarse grains were removed. Approximately 350 μg were transferred to acid-cleaned vials using a damp sable brush for elemental analyses and the remaining ~50 μg was used for stable isotope analyses. All the generated data are given in Table 1.

Trace element analyses

For the Mg/Ca analyses the standard cleaning protocol for foraminifera54 was used. The treatment took place in the metal free suite of the Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford. After dissolution, the samples were centrifuged for 5 min (5000 rpm) to exclude any remaining insoluble particles from the analyses. The samples were diluted with 2% nitric acid water before analysis with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS; Perkin Elmer NexION 350D at the Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford. Instrumental precision of the ICP-MS was monitored every five samples by analysis of an in-house standard solution with a Mg/Ca of 2.93 mmol mol−1 (long-term standard deviation of 0.026 mmol mol−1 or 0.88%).

To enable interlaboratory comparison, the ECRM752-1 limestone standard, with a reported Mg/Ca ratio of 3.75 mmol mol−1 (ref. 55), was also analysed (n = 3), yielding an average value of 3.85 ± 0.027 mmol mol−1. Procedural blank values below zero were measured. Negative values can apparently occur due to the nonlinearity of the calibration at very low values. All the Mg/Ca values are given in mmol mol−1. Replicate measurements of 7 samples revealed an average standard deviation of 0.11 mmol mol−1 (Table 2). To monitor the cleaning efficacy, Al/Ca, Fe/Ca, and Mn/Ca were measured alongside Mg/Ca. None of these ratios showed covariance with Mg/Ca (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Stable isotopes

Samples ranging from 41 to 75 μg, in mass were analysed isotopically for δ13C and δ18O at the Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, using a Thermo Delta V Advantage gas source mass spectrometer, fitted with a Gas Bench II peripheral. Within the Gas Bench II sample block, the powdered samples, in 12 mL He-flushed exetainers (Labco), are reacted with 100% phosphoric acid at 50 °C. The relative 13C/12C values are reported in the conventional δ13C (‰) notation, relative to the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (V-PDB), by assigning a value of +1.95‰ exactly to NBS-19. The relative 18O/16O values are reported in the conventional δ18O (‰) notation, relative to V-PDB, on a normalised scale such that the δ18O of NBS-19 is −2.2‰. Reproducibility of in-house marble standard NOCZ during these analytical runs was 0.03‰ for δ13C and 0.045‰ for δ18O (1σ, n = 5), with average δ13C = 2.17 ± 0.03 (1σ, n = 5) and δ18O = −2.03 ± 0.045‰ (1σ, n = 5) within the combined uncertainty of the long-term average of NOCZ (δ13C = 2.17 ± 0.06; δ18O = −1.90 ± 0.09‰; 1σ; n = 120).

Oceanographic data

The mean annual and monthly ocean temperature and salinity data from the period between January 2004 and January 2020 were extracted for each core site from the International Argo Ocean Monitoring Program56. The values are quality-controlled and refer to data from the first 1000 m of the water column. Instead of extrapolating single-point hydrographic data at the exact core coordinates, average surface (2.5 m) temperature and salinity values for each site were extracted from an area of 0.1 × 0.1 decimal degrees (~10 × 10 km) around the site location.

Ocean carbonate system data were taken from GLODAPv1.157. Given the late Holocene age of the core tops, we corrected the modern seawater data for the acidifying influence of anthropogenic CO2, by subtracting the GLODAPv1.1 anthropogenic Dissolved Inorganic Carbon (DIC) estimates from the total DIC values to provide an estimate of preindustrial DIC. These values, along with paired alkalinity, nutrient, and hydrographic data, were used to make preindustrial CO2 system determinations for GLODAP using CO2sys.m v1.158. This dataset was then imported to Ocean Data View59 and carbonate system variables obtained for each site at species-specific apparent calcification depth range over an area of 100 km around the sampling locations using Ocean Data View’s 3D estimation tool. For consistency further oceanographic parameters (3D Temperature, 3D Salinity, and 3D Density) were calculated for the same depth ranges.

Estimation of temperatures and apparent calcification depths (ACDs)

In the literature, foraminifera ACDs are calculated via either one or a combination of isotope or Mg/Ca temperature (TMg/Ca) methods. Since “vital effects” strongly offset shell oxygen isotopes from equilibrium values, calcification depth estimates using δ18O may be less accurate60. In the present study, TMg/Ca reconstructions were used for ACD determination. For G. truncatulinoides, given the absence of symbionts and the influence of secondary crust on total shell Mg/Ca, we also calculated ACDiso (see Supplementary Note). The Mg/Ca reconstructed temperatures (calculated following the procedures described below) for each species were compared with the mean annual temperature profile for sites between 23°N and 23°S and mean temperatures of the three warmest months of the year north of 23°N and south of 23°S, similar to previous studies61. For these extratropical locations, the oceanographic parameters were averaged only for the three warmest months, since studies have shown that the largest flux of foraminifera dwelling above the thermocline occurs during the warmest months of the year at these latitudes62,63. The water depth where shell TMg/Ca matched that of the in situ water temperature profile was considered to reflect the calcification depth (ACDMg/Ca) of the respective species at the site.

While non-thermal factors like carbonate chemistry and salinity can influence Mg/Ca in planktonic foraminifera, their effects are species-specific and secondary to temperature64,65. Given their uncertainty and the inconsistent taxon-specific responses that make universal corrections unreliable, no adjustments were applied, and Mg/Ca ratios were used solely as temperature indicators for calcification depth estimates.

There are many published Mg/Ca—temperature calibration equations for various planktonic foraminifera species. Temperature estimates using seven different equations were compared with the in situ SSTs at each site along the transect (Supplementary Fig. 4). The best-fitting equations, which most accurately describe the data and predict calcification depths comparable to those reported in the literature, were those from ref. 66, which were also derived from the same region, for G. ruber albus [Mg/Ca = 0.4 (±0.28) * exp (0.094 (± 0.01) * T) Eq. 1] and T. trilobus [Mg/Ca = 0.6 (±0.16) * exp (0.075 (±0.006) * T) Eq. 2]. For G. truncatulinoides the ref. 27 calibration equation for samples shallower than 4 km [Mg/Ca = 0.975 (±0.07) * exp (0.06 (±0.007) * T) Eq. 3] was used. This equation was produced from the superset of the present samples and provides good characterization of the present dataset.

Geochemical determination of seawater density

The combination of Mg/Ca ratios of foraminiferal shell calcite with δ18Oshell isotope measurements has been used to reconstruct ambient δ18Oseawater values and, subsequently, water salinities through the commonly applied technique67,68. For the two globigerinid species, the δ18Oshell, without any correction for vital effects, was converted to δ18Oseawater using the Mulitza et al.69, equations. For G. truncatulinoides, which is assumed to calcify in equilibrium with seawater without vital effects70,71, the general quadratic Kim and O’Neil72 equation rewritten by ref. 73 was used to convert δ18Oshell to δ18Oseawater. Subsequently the δ18Oseawater was converted to salinity values using the global δ18Oseawater—salinity relationship of Broecker74 for all species. The geochemically derived temperature and salinity values were then entered into the equation of state to calculate in situ and potential seawater densities18,75 at average depths of 50 m for G. ruber, 60 m for T. trilobus and 300 m for G. truncatulinoides. These depths were obtained by averaging the Mg/Ca-derived depth estimates for each species along the transect. The two different definitions of density serve different purposes: in situ density is the correct density to use when calculating the weight of the fluid and is relevant to buoyancy considerations, whereas potential density is the appropriate variable to employ when inferring ocean dynamics and in this form is given in ocean atlases.

The error in the δ18O of seawater (σδw) is a combination of the error in the measurement of δ18Oshells (σδc = 0.08‰) and the error in the Mg/Ca-derived pelagic temperature (σT = 0.194‰): σδw = √σΤ2 + σδc2, consequently σδw = 0.21‰. The total error in the ice-volume–corrected δ18O of seawater is σδw-ice = √σδw2 + σSL2 = 0.23‰. By assuming a linear relationship between σδw-ice and salinity76, the partial differential equations of ref. 75 yield an error for salinity σS = 0.63 psu and for in situ density σt = 1.72 kg m−3.

Shell traits from μCT analyses

Microcomputed tomography (μCT) provides high-precision spatial information, enabling the study of the three-dimensional mass distribution of foraminiferal tests and the quantification of detrimental detrital infillings. Shell traits for each sample were calculated from a subset of the specimens collected, with shell weight being an average 50 specimens23 and the μCT-based traits being the average of approximately 20 specimens. μCT data of ~20 specimens per species per site for G. ruber s.s. were obtained from Zarkogiannis et al.77,78 and for T. trilobus from Zarkogiannis79. Various shell traits resulting from the spatial analyses of the existed tomographs include the “potential cell” volume, which represents the total volume, assuming that the cell was alive with all its chambers filled with protoplasm, and the “potential” outer surface area (Fig. 5). Volume-normalized foraminiferal shell weights were determined by dividing the average shell weights by the average “potential cell” volume (Fig. 5C) for each sample. The ratio of mass to volume is a measure of density and thus volume-normalized shell weights are termed bulk shell density (BSD)23. Furthermore, the total test surface area and test volume (i.e., the volume of the calcite test) were determined, and the ratio of these two parameters was used as an estimate of the average test thickness. Finally, the ratio of the test volume to the “potential cell” volume, when expressed as a percentage, provides an estimate of the total amount of biomineralized space per unit volume within the foraminiferal cell. This is referred to here as the test percentage (test %).

A The foraminiferal test is segmented in yellow, while regions covered by external debris are segmented in red; B Internal chamber voids and debris are grouped together (blue) to represent the volume that would have been occupied by protoplasm; C Protoplasm and shell volumes are combined (cyan) to estimate the total potential “cell” volume occupied by a living foraminifer.

Statistical analyses

The key environmental parameters considered for the present statistical analyses encompass a range of factors, such as: a) geochemically reconstructed seawater in situ densities (DensityMg/Ca in Table 2); b) Argo salinity at ACD (Salinity in Table 2); c) 3D Density; d) 3D Salinity; and 3D Temperature (refer to Oceanographic Data section). In our approach, the key oceanographic parameters were derived using Mg/Ca-based calcification depths. To avoid statistical circularity, we excluded Mg/Ca-derived temperature from our linear mixed models. However, to ensure that the relationships observed between foraminiferal traits and oceanographic variables were not solely driven by temperature, we conducted the analyses using the independent 3D Temperature estimates. This allowed us to verify that the patterns identified were not artifacts of temperature-based derivation.

In addition to the in situ salinity, temperature and density, we used the concentration of carbonate ions as predictors of the traits. In particular, the study addresses carbonate system parameters, specifically e) Alkalinity; and f) CO32− concentrations ([CO₃²−]) at ACD. Alkalinity (ALK), however, exhibited an extremely high correlation (r = 0.963) with Argo salinity, making it statistically impractical to separate their individual effects within the model; therefore, it was not further considered in the LMMs. Instead, we used [CO₃²−] to address the effects of the carbonate system as it was less correlated with other predictors (see correlation’s Table 1) and also is traditionally associated with shell calcification traits. Substituting ALK in place of [CO₃²−] in our models did not alter the selected results based on AICc, due to the strong correlation between these parameters. This interchangeability confirms that our conclusions remain robust regardless of whether ALK or [CO₃²−] is used, reinforcing the validity of our chosen model structure.

Once we had selected the predictor variables to use in our analyses, we compared the six traits (“potential cell” volume, shell weight, bulk shell density, test volume, test thickness, and test percent) among the three species examined. We used Kruskal-Wallis tests to account for non-normality and differences in the variances between species, and to correct for multiple comparisons (n = 6), we used the Benjamini and Yekuetli adjustment80. These adjustments minimize Type I error, providing a conservative estimate of the differences among species.

Because the six traits all varied significantly across species (see Fig. 2), we had to consider differences in the responses of each species to their surrounding environmental conditions. To achieve this goal, we employed two categories of linear models to analyse the relationships between each trait and the environmental variables while accounting for species identity. First, we developed linear mixed effects models (LMMs), treating species identity as a random. By incorporating species identity as a random intercept in these models, we controlled for the nonindependence of traits within each species (Fig. 2), thereby ensuring that this trait variation and the composition of species at each site did not obscure the relationship between environmental factors and traits. A significant result in these LMMs would indicate an association between traits and environmental variables irrespective of species identity.

We compared LMMs incorporating density (density model), salinity (salinity model), and both (density + salinity model), to a null model incorporating only carbonate ion concentrations [CO32−] using Akaike information criterion values corrected for small sample sizes (AICc), to determine which model best explained our data. For the LMM incorporating both density and salinity, we examined the effect sizes of the environmental predictors and their standard errors. The predictors used in these models are somewhat strongly correlated, leading to high variance inflation factors (VIF > 6) for the full model predicting shell density (Salinity = 7.1, [CO32−] = 10.7). However, this model was not selected for using AICc (see Table 1). All other models had VIF values less than 6, indicating that this multicollinearity had little effect on the model parameters.

After examining the trait-environment relationships, irrespective of species, we then reincorporated species identity as an intended, fixed effect to examine how density influences the traits of each species independently. For each trait, we used a model incorporating density and CO32− and converted species identity from a random effect to a fixed effect that interacted with density. These linear models explicitly model the response of each species to density. As with the linear mixed effects models, multicollinearity had little effect on the model parameters (all VIF < 4). Before generating both sets of linear models, we centred and scaled the trait and environmental data to unit variance so that the effect sizes of each model were comparable and informative. Each of the models in which effect sizes and confidence intervals were required (the density + salinity LMMs and all fixed effect models) were checked for heteroscedasticity and normality using the Breusch-Godfrey test in the R package “lmtest”81. For the fixed effect model using shell weight as the response, the model was significantly heteroscedastic (p = 0.016), likely due to the differences between the two populations of G. truncatulinoides (see above). Therefore, we modified this model using weighted regression (the significance and magnitude of the coefficients were only negligibly affected). All models were fit using log-likelihood.

All the statistical analyses were conducted in R (v. 4.3, R Core Team 2024), and a list of packages used and their versions can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study, including those used to generate the figures are available at Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29459315.

References

Schiebel, R. et al. Modern planktic foraminifera. Paläontologische Z. 79, 135–148 (2005).

Furbish, J. D. et al. Hydrodynamic strategies in the morphological evolution of spinose planktonic foraminifera. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 109, 1055–1072 (1997).

Rebotim, A. et al. Factors controlling the depth habitat of planktonic foraminifera in the subtropical eastern North Atlantic. Biogeosci. Discuss 2016, 1–48 (2016).

Fairbanks, R. G. et al. Vertical distribution and isotopic fractionation of living planktonic foraminifera from the Panama Basin. Nature 298, 841–844 (1982).

Meilland, J. et al. Population dynamics and reproduction strategies of planktonic foraminifera in the open ocean. Biogeosciences 18, 5789–5809 (2021).

Hull, P. M. et al. Seasonality and depth distribution of a mesopelagic foraminifer, Hastigerinella digitata, in Monterey Bay, California. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 562–576 (2011).

Campbell, R. W. et al. Role of lipids in the maintenance of neutral buoyancy by zooplankton. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 263, 93–99 (2003).

Boyd, C. et al. Impact of osmolytes on buoyancy of marine phytoplankton. Mar. Biol. 141, 605–618 (2002).

Barker, S. et al. Foraminiferal calcification response to glacial-interglacial changes in atmospheric CO2. Science 297, 833–836 (2002).

Barrett, R. et al. What controls planktic foraminiferal calcification?. Biogeosciences 22, 791–807 (2025).

Leung, J. Y. S. et al. Is ocean acidification really a threat to marine calcifiers? A systematic review and meta-analysis of 980+ studies spanning two decades. Small 18, 2107407 (2022).

Marañón, E. et al. Coccolithophore calcification is independent of carbonate chemistry in the tropical ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, 1345–1357 (2016).

de Nooijer, L. J. et al. Foraminifera promote calcification by elevating their intracellular pH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15374–15378 (2009).

Evans, D. et al. Assessing foraminifera biomineralisation models through trace element data of cultures under variable seawater chemistry. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 236, 198–217 (2018).

Armstrong, H. A. et al. Foraminifera. In Microfossils (Wiley, 2004).

Marszalek, D. S. The role of heavy skeletons in vertical movements of non-motile zooplankton. Mar. Behav. Physiol. 8, 295–303 (1982).

Raven, J. A. et al. The evolution of silicification in diatoms: inescapable sinking and sinking as escape? N. Phytol. 162, 45–61 (2004).

Zarkogiannis, S. D. et al. Influence of surface ocean density on planktonic foraminifera calcification. Sci. Rep. 9, 533 (2019).

Malmgren, B. A. et al. Phyletic gradualism in a late Cenozoic planktonic foraminiferal lineage; DSDP site 284, Southwest Pacific. Paleobiology 7, 230–240 (1981).

Norris, R. D. et al. Evolution of depth ecology in the planktic foraminifera lineage Globorotalia (Fohsella). Geology 21, 975–978 (1993).

Schneider, C. E. et al. Isotopic evidence for interspecies habitat differences during evolution of the Neogene planktonic foraminiferal clade Globoconella. Paleobiology 22, 282–303 (2015).

Larson, A. G. et al. Inflation-induced motility for long-distance vertical migration. Curr. Biol. 34, 5149–5163.e5143 (2024).

Zarkogiannis, S. D. et al. Calcification, dissolution and test properties of modern planktonic foraminifera from the Central Atlantic Ocean. Front. Marine Sci. 9, 864801 (2022).

Schiebel, R. Planktic foraminiferal sedimentation and the marine calcite budget. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 16, 1065 (2002).

Farmer, E. C. et al. Corroborating ecological depth preferences of planktonic foraminifera in the tropical Atlantic with the stable oxygen isotope ratios of core top specimens. Paleoceanography 22, PA3205 (2007).

Zarkogiannis, S. Calcification and ecological depth preferences of the planktonic foraminifer Trilobatus trilobus in the central Atlantic. R. Soc. Open Sci. 11, 240179(2024).

Cléroux, C. et al. Reconstructing the upper water column thermal structure in the Atlantic Ocean. Paleoceanography 28, 503–516 (2013).

Osborne, E. B. et al. Calcification of the planktonic foraminifera Globigerina bulloides and carbonate ion concentration: results from the Santa Barbara Basin. Paleoceanography 31, 2016PA002933 (2016).

Ravelo, A. C. et al. Oxygen isotopic composition of multiple species of planktonic foraminifera: Recorders of the modern photic zone temperature gradient. Paleoceanography 7, 815–831 (1992).

Takagi, H. et al. Characterizing photosymbiosis in modern planktonic foraminifera. Biogeosciences 16, 3377–3396 (2019).

Niebler, H.-S. et al. Oxygen isotope values of planktic foraminifera: a tool for the reconstruction of surface water stratification. in Use of Proxies in Paleoceanography: Examples from the South Atlantic (eds. Fischer, G. & Wefer, G.) (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1999).

Frankel J. et al. Palaeoceanographic reconstruction of the Benguela-Namibia Upwelling System during the last two climatic cycles: on the use of planktonic foraminifera test mass as a paleoclimatic tool. Quat. Res. 106, 171–183 (2024).

de Vargas, C. et al. Pleistocene adaptive radiation in Globorotalia truncatulinoides: genetic, morphologic, and environmental evidence. Paleobiology 27, 104–125 (2001).

Aze, T. et al. A phylogeny of Cenozoic macroperforate planktonic foraminifera from fossil data. Biol. Rev. 86, 900–927 (2011).

Sprovieri, A. et al. Globorotalia truncatulinoides excelsa n. subsp., foraminifero planctonico guida per il Pleistocene inferiore. Boll. della Soc. à Geologica ltaliana 99, 3–11 (1980).

Faul, K. L. et al. Reconstructions of upwelling, productivity, and photic zone depth in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean using planktonic foraminiferal stable isotopes and abundances. J. Foraminifer. Res. 30, 110–125 (2000).

Spear, J. W. et al. Globorotalia truncatulinoides (dextral) Mg/Ca as a proxy for Gulf of Mexico winter mixed-layer temperature: evidence from a sediment trap in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Micropaleontol. 80, 53–61 (2011).

Mulitza, S. et al. Planktonic foraminifera as recorders of past surface-water stratification. Geology 25, 335–338 (1997).

Hemleben, C. et al. Foraminiferal population dynamics and stable carbon isotopes. in Carbon Cycling in the Glacial Ocean: Constraints on the Ocean’s Role in Global Change (eds. Zahn, R., Pedersen, T. F., Kaminski, M. A. & Labeyrie, L.) (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1994).

Wilke, I. et al. The influence of seawater carbonate ion concentration [CO32−] on the stable carbon isotope composition of the planktic foraminifera species Globorotalia inflata. Mar. Micropaleontol. 58, 243–258 (2006).

Metcalfe, B. et al. Late Pleistocene glacial–interglacial shell-size–isotope variability in planktonic foraminifera as a function of local hydrography. Biogeosciences 12, 4781–4807 (2015).

Reynolds, C. E. et al. Environmental controls on the geochemistry of Globorotalia truncatulinoides in the Gulf of Mexico: implications for paleoceanographic reconstructions. Mar. Micropaleontol. 142, 92–104 (2018).

Hupp, B. N. et al. Geochemical differences between alive, uncrusted and dead, crusted shells of Neogloboquadrina pachyderma: implications for paleoreconstruction. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 38, e2023PA004638 (2023).

Davis, C. V. et al. Relationships between temperature, pH, and crusting on Mg/Ca ratios in laboratory-grown Neogloboquadrina foraminifera. Paleoceanography 32, 1137–1152 (2017).

Weinkauf, M. F. G. et al. Calcification intensity in planktonic foraminifera reflects ambient conditions irrespective of environmental stress. Biogeosciences 10, 6639–6655 (2013).

Lukas, R. et al. The mixed layer of the western equatorial Pacific Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 96, 3343–3357 (1991).

Shcherbina, A. Y. et al. Variability and interleaving of upper-ocean water masses surrounding the North Atlantic salinity maximum. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu Rev. 28, 106–113 (2015).

Aubone, N. et al. The surface salinity maximum of the South Atlantic. Prog. Oceanogr. 191, 102499 (2021).

Gonzalez-Mora, B. et al. Controls of shell calcification in planktonic foraminifers. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 956–961 (2008).

Pak, D. K. et al. Foraminiferal proxy response to ocean temperature variability and acidification over the last 150 years in the Santa Barbara Basin (California). Quat. Int. 469, 141–150 (2018).

Johnson, G. C. et al. Relative contributions of temperature and salinity to seasonal mixed layer density changes and horizontal density gradients. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 117, C04015 (2012).

Boudreau, B. P. et al. The role of calcification in carbonate compensation. Nat. Geosci. 11, 894–900 (2018).

Arbuszewski, J. et al. On the fidelity of shell-derived δ18Oseawater estimates. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 300, 185–196 (2010).

Barker, S. et al. A study of cleaning procedures used for foraminiferal Mg/Ca paleothermometry. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 4, 8407 (2003).

Greaves, M. et al. Interlaboratory comparison study of calibration standards for foraminiferal Mg/Ca thermometry. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, Q08010 (2008).

Argo. Argo float data and metadata from Global Data Assembly Centre (Argo GDAC) (SEANOE, 2000).

Key, R. M. et al. A global ocean carbon climatology: results from Global Data Analysis Project (GLODAP). Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 18, GB4031 (2004).

van Heuven, S. et al. CO2SYS v 1.1. in MATLAB Program Developed for CO2 System Calculations. ORNL/CDIAC-105b (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2011).

Schlitzer, R. Interactive analysis and visualization of geoscience data with Ocean Data View. Comput. Geosci. 28, 1211–1218 (2002).

Gray, W. R. et al. The effects of temperature, salinity, and the carbonate system on Mg/Ca in Globigerinoides ruber (white): a global sediment trap calibration. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 482, 607–620 (2018).

Hertzberg, J. E. et al. Refining Globigerinoides ruber Mg/Ca paleothermometry in the Atlantic Ocean. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 383, 123–133 (2013).

Tolderlund, D. S. et al. Seasonal distribution of planktonic foraminifera in the Western North Atlantic. Micropaleontology 17, 297–329 (1971).

Bé, A. W. H. Ecology of recent planktonic foraminifera: part 2: bathymetric and seasonal distributions in the Sargasso Sea off Bermuda. Micropaleontology 6, 373–392 (1960).

Gray, W. R. et al. Nonthermal influences on Mg/Ca in planktonic foraminifera: a review of culture studies and application to the last glacial maximum. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 34, 306–315 (2019).

Allen, K. A. et al. Trace element proxies for surface ocean conditions: a synthesis of culture calibrations with planktic foraminifera. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 193, 197–221 (2016).

Regenberg, M. et al. Calibrating Mg/Ca ratios of multiple planktonic foraminiferal species with δ18O-calcification temperatures: paleothermometry for the upper water column. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 278, 324–336 (2009).

Thornalley, D. J. R. et al. Holocene oscillations in temperature and salinity of the surface subpolar North Atlantic. Nature 457, 711–714 (2009).

Rohling, E. J. Paleosalinity: confidence limits and future applications. Mar. Geol. 163, 1–11 (2000).

Mulitza, S. et al. Temperature:δ18O relationships of planktonic foraminifera collected from surface waters. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 202, 143–152 (2003).

Erez, J. et al. Comparison of isotopic composition of planktonic foraminifera in plankton tows, sediment traps and sediments. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 33, 129–156 (1981).

Lončarić, N. et al. Oxygen isotope ecology of recent planktic foraminifera at the central Walvis Ridge (SE Atlantic). Paleoceanography 21, PA3009 (2006).

Kim, S.-T. et al. Equilibrium and non-equilibrium oxygen isotope effects in synthetic carbonates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 3461–3475 (1997).

Bemis, B. E. et al. Reevaluation of the oxygen isotopic composition of planktonic Foraminifera: Experimental results and revised paleotemperature equations. Paleoceanography 13, 150–160 (1998).

Broecker, W. S. The salinity contrast between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans during glacial time. Paleoceanography 4, 207–212 (1989).

Roberts, J. et al. Evolution of South Atlantic density and chemical stratification across the last deglaciation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 514–519 (2016).

LeGrande, A. N. et al. Global gridded data set of the oxygen isotopic composition in seawater. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L12604 (2006).

Zarkogiannis, S. D. et al. Tomographic data of G. ruber albus sensu stricto shells from central Atlantic core-top sediment samples [Dataset]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17088860.v1 (2022).

Zarkogiannis, S. D. et al. Tomographic data of G. truncatulinoides shells from central Atlantic core-top sediment samples [Dataset]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19747198.v2 (2022).

Zarkogiannis, S. Tomographic data of Trilobatus trilobus shells from central Atlantic core-top sediment samples [Dataset]. Dryad https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.6t1g1jx6q (2024).

Benjamini, Y. et al. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann. Stat. 29, 1165–1188 (2001).

Zeileis, A. et al. Diagnostic checking in regression relationships. R. N. 2, 7–10 (2002).

Zarkogiannis, S. et al. Summary table listing all the shell traits calculated for the different studied planktonic foraminifera species, together with the associated geochemical and in situ oceanographic data [Dataset]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29459315.v3 (2025).

Acknowledgements

S.D.Z. would like to acknowledge the UK Research and Innovation Grant (SODIOM) EP/Y004221/1. B.R.S. is funded by the NSF EAR Postdoc Fellowship 2305234. J.W.B.R. was supported by European Research Council Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme grant agreement No. 805246. The authors would like to thank Dr Joost de Vries for producing Supplementary Fig. 2 from the CASCADE dataset and Dr Lennart de Nooijer for the valuable discussions. This research used samples provided by the Lamont-Doherty Core Repository.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D.Z. conducted the laboratory analyses, contributed to formal analysis and data visualization, and led the generation of geochemical datasets. J.W.B.R. extracted and processed the in situ oceanographic data and calculated the carbonate system parameters. B.R.S. performed the statistical analyses and contributed to formal analysis and visualization. P.G.M. provided guidance on the geochemical measurements and contributed to data interpretation. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Yiming Wang and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zarkogiannis, S.D., Rae, J.W.B., Shipley, B.R. et al. Planktonic foraminifera regulate calcification according to ocean density. Commun Earth Environ 6, 605 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02558-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02558-w