Abstract

Lakes are critical sentinels of climate change, yet their responses to rapid warming remain poorly understood. Here we present organic geochemical data of lacustrine sediments from eastern China during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (56 million years ago) to unravel environmental and biotic responses to rapid warming. Organic geochemical proxies indicate ≥7 °C continental warming in East Asia, triggering cascading effects including intensified stratification, bottom-water deoxygenation, eutrophication, and methanogenesis. These processes, evidenced by isotopic, productivity, and redox proxies, parallel modern lake responses to anthropogenic forcing. During the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, elevated methane emissions from lacustrine systems likely amplified warming through positive carbon-cycle feedbacks. Our findings highlight lakes as one of potential dynamic amplifiers of carbon cycle perturbations, providing critical insights into freshwater ecosystem resilience in a warming world. This deep-time perspective underscores the vulnerability of modern lakes to cascading ecological disruptions, informing models of ecosystem resilience and carbon-climate interactions under sustained warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anthropogenic carbon emissions are causing rapid global warming and associated environmental change1, which are expected to pose severe threats to lake ecosystems in the future2. Presently, however, the limited duration of modern observational records hinders our scientific understanding of potential ecological and environmental responses to warmer climates in lakes. Studies on the past responses of lakes to warmer climatic conditions could provide unique insight into natural processes and mitigation strategies for lake ecosystems.

The Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum (PETM, ~56 Ma) stands as one of the most abrupt and extreme hyperthermal events in Earth’s history, characterized by a rapid global temperature rise of 5–8 °C and a remarkable negative carbon isotope excursion (CIE) in marine and terrestrial substrates3. This event, triggered by a massive release of isotopically light carbon into the atmosphere-ocean system4, likely originated from methane hydrate dissociation4, volcanic outgassing5, thermogenic methane6, or permafrost thaw7. Therefore, the PETM offers a critical deep-time analog for understanding biotic and environmental responses to anthropogenic warming3,8. While marine PETM records have been extensively studied, terrestrial and lacustrine archives—key components of the global carbon cycle—remain comparatively underexplored. Lakes, as sensitive sentinels of environmental change, integrate signals from watersheds, atmosphere, and aquatic ecosystems, making them ideal archives to disentangle the cascading effects of warming on hydrology, biogeochemistry, and biodiversity9.

Existing studies of PETM terrestrial systems have focused on mammalian migrations10, hydroclimate11, and floral turnovers12. However, lacustrine records, which capture both aquatic and catchment processes, are sparse and often lack multi-proxy datasets needed to resolve ecosystem-scale feedbacks. For instance, while marine sediments document expanded oxygen minimum zones and shifts in planktonic communities13,14, analogous responses in lakes—such as stratification dynamics, methane cycling, and nutrient-driven productivity—remain poorly constrained. This knowledge gap limits our ability to model how inland water bodies, which today store large amounts of organic carbon15, may respond to or amplify future warming.

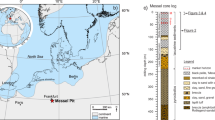

Recently, we identified the PETM event in a lacustrine section (Longwangjing) from the Jianghan Basin, eastern China16 (Fig. 1). This section, primarily consisting of the upper Gongjiachong and lowermost Yangxi Formations, represents an ideal sedimentary sequence for studying lake responses to global warming. The upper Gongjiachong Formation is dominated by marls. The lowermost part of the Yangxi Formation is dominated by finely laminated black shales interbedded with thin limestone layers. Abundant exceptionally well-preserved fossils were discovered in the laminated shales of the Yangxi Formation16 (Fig. 1). The fish assemblage recovered from the shales indicates a freshwater lacustrine setting for these deposits17. Comprehensive biostratigraphic investigations have constrained the chronology of the Yangxi Formation to the early Eocene18. The oldest known primate fossil (Archicebus achilles, ~56 Ma) found in the Longwangjing section (Fig. 1C), further assigned the age of the lowermost part of this formation to the earliest Eocene19. The PETM in the Longwangjing section was defined within the stratigraphic interval between 5.5 and 2.4 m based on negative δ13C excursions in both inorganic and organic substrates16 (Fig. 1D). The organic matter in the section is relatively thermally immature, as indicated by Tmax values of 401–428 °C (temperature of maximum pyrolysis yield in Rock-Eval pyrolysis), making it usable to investigate biomarkers20. Lipid biomarkers preserved in lacustrine sediments provide a powerful toolkit to reconstruct lacustrine environmental and ecological changes. Branched glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers (brGDGTs) offer robust temperature reconstructions21, while carbon isotopes of terrestrial n-alkanes (δ13C) trace vegetation changes22. Steroidal compounds serve as proxies for primary productivity23, whereas redox-sensitive biomarkers like gammacerane and pristane/phytane ratios elucidate water-column stratification and hypoxia23,24. Critically, isoprenoid GDGTs (isoGDGTs) derived from archaeal membranes can fingerprint methanogenic activity, linking methane cycling to microbial ecology25,26. When integrated, these proxies enable a holistic reconstruction of lacustrine environmental and ecological trajectories during hyperthermals.

A Location and regional geology of the Longwangjing section (red star). B Field view of the Longwangjing section, showing the Paleocene/Eocene boundary and the fossil bed location. C Primate fossil (Archicebus achilles)19. D Carbon isotope stratigraphy of total organic carbon (δ13CTOC) and carbonate (δ13Ccarb)16. The colored area demarcates the PETM interval, defined by a large negative carbon isotope excursion.

Here, we present a multi-proxy biomarker study for the Longwangjing section to address three key questions: (1) How did abrupt warming alter lacustrine thermal structure and hydrology? (2) What mechanisms linked warming, nutrient fluxes, and ecosystem productivity? (3) Did methane cycling in lakes amplify carbon-climate feedbacks during the PETM? Our results show a warming of at least 7 °C in the East Asian continent during the PETM. By coupling the temperature reconstructions with isotopic, productivity, redox, and methane cycling proxies, we demonstrate that the PETM warming intensified lake stratification, deoxygenation, eutrophication, and methanogenesis. Increased lake methane emissions likely amplified PETM warming through positive feedbacks—a critical mechanism underrepresented in current climate models.

Results and Discussion

brGDGT-based temperature reconstruction and its comparison with carbonate clumped isotope temperature

Our paleotemperature reconstructions are based on concentrations of brGDGTs extracted from sediments. brGDGTs are a suite of membrane lipids produced by bacteria, and their relative distribution is highly correlated to ambient temperatures27,28,29. We used the MBT’5ME (methylation of 5-methayl branched tetraethers) index21 and newly developed pantropical temperature calibration29 to reconstruct mean annual air temperature (MAT) for the Longwangjing section. We applied this calibration due to (1) consideration of the improved chromatographic separation (MBT’5ME)30 relative to older calibrations, (2) its applicability for lake-specific sediments29, (3) appropriate upper calibration limit (29.2 °C) which is more suitable for the warmer Eocene climate, and (4) the reconstructed temperatures in broadly agreement with estimates from pollen data31.

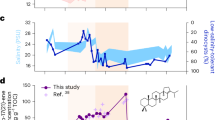

The reconstructed brGDGT MATs vary between 14.5 °C and 27.6 °C (calibration error: ±2.26 °C; Fig. 2B). Pre-PETM temperatures fluctuate around an average of 18. 4 °C (n = 6) but increase by ~8 °C to an average of 26.4 °C (n = 23) during the PETM. In general, the absolute temperature reconstructions in the Jianghan Basin are slightly lower than those reported from the adjacent Nanyang Basin based on brGDGT data32. This could have arisen from different calibrations or caveats associated with the brGDGT paleothermometer (Supplementary Fig. 1). Recent studies have noted that without a site-specific calibration, or at least more information on local sources of GDGT production, absolute temperature reconstructions using any external calibration should be interpreted with caution33,34. Despite this, brGDGT MAT estimates from the two basins yield a similar magnitude of warming (~7–8°C) during the PETM. However, in terms of both absolute temperature and warming amplitude, brGDGT MATs are substantially lower than carbonate clumped isotope-derived temperatures (T(Δ47)), which range between 27.4 °C and 40.5 °C with a warming amplitude reaching ~11°C (Fig. 2C)16. Two factors could contribute to this discrepancy. First, because lacustrine authigenic carbonates precipitation occurs in summer35, T(Δ47) had been interpreted to bias towards warm month mean temperatures16. Second, the dispersed limestone layers used for T(Δ47) reconstructions during the PETM could be formed during periods of extreme lake heatwaves, which recorded extreme warm lake surface water temperature and in turn amplified warming amplitude.

Overall, both organic and inorganic proxies indicate that the East Asian continent warmed by at least 7 °C during the PETM period, which is substantially higher than the magnitude of warming (~4°C) in global mean sea surface temperature36. Our findings align closely with recent research showing that terrestrial temperature responses are disproportionately amplified under global warming conditions compared to oceanic environments37. The increased sea-land thermal contrast might intensify the monsoon-like climate, causing more precipitation and greening in the East Asian continent31,38,39.

Compound specific stable isotopic data and implications for carbon cycle

The pronounced negative CIEs recorded in lacustrine sediments during the PETM—approximately −5‰ in n-alkanes and bulk organic carbon16, and a more extreme ~−7‰ in the isoprenoids pristane and phytane (Fig. 3) —provide critical insights into both global carbon cycle perturbations and localized ecosystem dynamics. These isotopic depletions are consistent with the rapid injection of large quantities of isotopically light carbon into the atmosphere-ocean system, a hallmark of the PETM3. The magnitude and synchronicity of the CIEs across multiple organic components strongly support the hypothesis that 13C-depleted carbon reservoirs, such as methane hydrates from continental margins or thermogenic methane from organic-rich sedimentary basins, were destabilized during this interval4,6. Methane release, either directly or via oxidation to CO2, would have diluted the δ13C of atmospheric CO2, propagating this signal into terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems through photosynthetic pathways and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) uptake40.

The −5‰ CIE in bulk organic carbon likely reflects a mixture of autochthonous (aquatic) and allochthonous (terrestrial) organic matter. The parallel −5‰ shift in long-chain n-alkanes (C27–C31), biomarkers predominantly derived from terrestrial higher plants, suggests that the atmospheric CO2 δ13C signal was transmitted to land plants via changes in photosynthetic fractionation. C3 plants, which dominated Paleocene-Eocene terrestrial ecosystems41, exhibit a well-documented correlation between atmospheric CO2 δ13C and leaf wax n-alkane δ13C, modulated by factors such as pCO2, water availability, and stomatal conductance42,43. The consistency between bulk organic carbon and n-alkane CIEs implies that terrestrial organic matter contributed substantially to the lacustrine sedimentary record, though aquatic productivity likely increased concurrently due to PETM warming and nutrient fluxes.

The amplified ~−7‰ CIE in pristane and phytane, however, points to distinct biogeochemical processes within the lake system. Pristane and phytane are primarily derived from the phytyl side chain of chlorophyll a (photoautotrophs) or archaeal membrane lipids (e.g., methanogens)44, with their δ13C values reflecting the isotopic composition of their carbon sources and associated metabolic fractionation45. The more negative δ13C values in these isoprenoids compared to bulk organic matter and n-alkanes may be attributed to two factors. First, enhanced methanogenesis in anoxic lake sediments and subsequent aerobic or anaerobic oxidation of methane (δ13C: −60‰ to −110‰) could have transferred this extremely light carbon to biomass, including archaeal lipids, thereby imprinting a stronger CIE on pristane and phytane46. Second, increased contributions of 13C-depleted DIC to lake primary productivity, driven by methane-derived CO2 invasion or intensified microbial respiration, may have further lowered the δ13C of photoautotroph-derived isoprenoids45.

The disparity between terrestrial and aquatic biomarker CIEs underscores the heterogeneous response of ecosystems to PETM forcings. While terrestrial plants recorded the global atmospheric δ13C signal with minimal attenuation, aquatic systems experienced additional isotopic modulation from local redox processes, microbial activity, and carbon source variability. This decoupling highlights the importance of compound-specific isotope analysis in disentangling regional environmental feedbacks from global carbon cycle drivers22,47. In summary, the lacustrine δ13C record during the PETM captures a complex interplay of global carbon release, atmospheric-terrestrial coupling, and localized aquatic biogeochemical cascades. The exaggerated CIE in pristane and phytane serves as a sensitive tracer of methane cycling intensification and water column redox shifts, offering an archive of both global climate dynamics and lake ecosystem resilience during the hyperthermal.

Biomarker indicators of source and ecology

Since some biomarker compounds or compound classes are associated with a particular biological source, molecular distributions can be informative about changes in source and ecology23. The pronounced variations in oleanane and steroidal biomarkers during the PETM offers a nuanced lens to explore the cascading impacts of abrupt warming on terrestrial-aquatic biogeochemical linkages.

Oleanane, a diagenetic product of angiosperm-derived triterpenoids, is particularly diagnostic of flowering plant contributions to sedimentary archives48. The oleanane index (oleanane / oleanane + C30 αβ hopane), used as an indicator of relative angiosperm organic matter input to aquatic organic matter input, ranged between 0 and 0.3, with notable elevated values during the PETM at the Longwangjing section (Fig. 4C). Its surge implies not only enhanced productivity of angiosperms but also accelerated export of plant debris to lacustrine basins. This could reflect two synergistic mechanisms: (1) CO2-induced fertilization under PETM’s elevated pCO2 (~2000 ppm)49, which likely stimulated the expansion of angiosperm-dominated ecosystems31, and (2) intensified hydrological cycle38, which amplified physical erosion of soils and organic matter transport.

A Total organic carbon δ13C values (δ13CTOC)16. B brGDGT-based MATs. Orange shading indicates RMSE uncertainty (±2.26 °C). C Oleanane index (oleanane/oleanane + C30 αβ hopane), indicative of angiosperm plant input. D Ratio of steroidal compounds over hopanoids. E Gammacerane index ((gammacerane/gammacerane + C30 αβ hopane) × 100), indicative of physical stratification of the water column; F Pr/Ph ratio. G Ratio of GDGT-0 to Crenarchaeol (higher values indicate greater methanogenesis). H Methane Index (MI) (higher values indicate greater methanotrophy). MI = (GDGT-1 + GDGT-2 + GDGT-3)/(GDGT-1 + GDGT-2 + GDGT-3 + Crenarchaeol + Crenarchaeolˊ)26. The colored area indicates the PETM event. See lithological legend in Fig. 1.

Steroidal compounds in lacustrine systems, including steranes and sterenes, are primarily sourced from eukaryotic algae23, with their abundance often tied to nutrient availability. The relative contribution of eukaryotes versus prokaryotes to the biomass in sediments can be evaluated via the steroids/hopanoids index23. At the Longwangjing section, the steroids/hopanoids index presents a markable increase from a pre-PETM average of ~0.51 up to ~2 during the PETM (Fig. 3D). The rise in steroidal compounds reflects heightened aquatic primary productivity, potentially linked to eutrophication triggered by nutrient influx (e.g., phosphorus, nitrogen) from terrestrial runoff. In addition, extended growing season due to global warming may also contribute to boosting lake primary productivity.

In sum, the synergy of these biomarkers implies a climate-mediated feedback loop: warming and CO2-driven fertilization may have boosted vascular plant productivity, increasing terrestrial organic export, while nutrient enrichment in lakes stimulated algal blooms. However, alternative mechanisms, such as shifts in microbial communities or preservation biases due to anoxia, cannot be entirely ruled out.

Lake stratification, redox change, and methane cycling

A suite of biomarkers was used to assess changes in water column stratification, redox potential, and methane cycling in lake, including gammacerane index, pristane/phytane (Pr/Ph) ratio, GDGT-0/Crenarchaeol25, and methane index (MI = [GDGT-1 + GDGT-2 + GDGT-3]/[GDGT-1 + GDGT-2 + GDGT-3 + Crenarchaeol + Crenarchaeolˊ])26 (Fig. 4).

Gammacerane derives from tetrahymanol produced by ciliates that thrive along the chemocline of physically stratified water columns24,50. The production of tetrahymanol by lacustrine bacterivorous ciliates in stratified lakes is well-documented51,52,53. Thus, the occurrence of gammacerane, expressed as the gammacerane index (=[gammacerane/(gammacerane + C30 αβ hopane) × 100]), has been used to infer changes in water column stratification in both marine and lacustrine settings24,54. At the Longwangjing section, the gammacerane index was generally lower than 15% before the PETM, while it increased up to ~70% across the PETM (Fig. 4E). Elevated abundance of gammacerane during the PETM may indicate the development of intensified water column stratification, possibly due to warming-driven surface heating and/or enhanced hydrological cycle. Water column stratification in lakes arises from density differences between surface (epilimnion) and deep waters (hypolimnion), driven by temperature (thermocline) and/or salinity gradients (chemocline)55. Climate change amplifies stratification through multiple interconnected mechanisms. Rising air temperatures increase surface water temperatures, reducing water density and enhancing thermal stability56. Warmer, less dense surface layers resist mixing with cooler, denser deep waters. For example, the extremely warm European summer of 2003 resulted in a long period of thermal stratification57. During the PETM, prolonged warming likely extended the duration of stratification, as evidenced by modern analogs where rising temperatures lengthen seasonal stratification in temperate lakes58,59. Alternatively, increased precipitation and runoff during the PETM likely introduced large volumes of low-salinity water into lake surfaces38, decreasing water transparency and creating density gradients independent of temperature60. This could have caused stable lake stratification by reinforcing the thermocline and reducing convective mixing60,61.

The extreme warmth and the development of intensified water column stratification during the PETM would have aided the development of water column oxygen-depletion by decreasing oxygen solubility and restricting oxygen exchange to deeper layers, respectively. This could be evidenced by pristane/phytane (Pr/Ph) ratio. Pristane and phytane are acyclic isoprenoids predominantly formed as degradation products of the chlorophyll phytyl chain from photoautotrophs and their formations are associated with redox conditions44; therefore, the Pr/Ph ratio has been proposed as a redox proxy, where low values (<1) indicate anoxic conditions due to preferential preservation of phytane under reducing environments, while higher values (>1) reflect oxic settings dominated by pristane stability23. The Pr/Ph ratio values below 1 during the PETM (Fig. 4F), together with the marked enrichments of molybdenum (Mo) and uranium (U) in the shales16, suggest anoxic conditions in the water columns. These anoxic environments ensured optimal conditions for exceptional preservation of animal skeletons16, and provided suitable conditions for the activity of methanogenic and methanotrophic archaea.

Isoprenoidal GDGTs (isoGDGTs) are biosynthesized by a wide range of archaea, with some isoGDGTs such as crenarchaeol and its isomer exclusively produced by ammonia-oxidizing Thaumarchaeota62,63. In contrast, GDGT-1, GDGT-2, and GDGT-3 are associated with high activity of methanotrophic archaea in methane rich environments64,65,66. Methanogenic archaea synthesize GDGT-0 as their dominant lipid, alongside minor isoGDGTs with one or more cyclopentane moieties62,67. Consequently, the GDGT-0/crenarchaeol ratio25 and the MI index26 have been proposed as tracers of past methane cycling variations, with GDGT-0/crenarchaeol ratios >2 indicating a substantial loading of methanogenic archaea25, and MI > 0.3 indicating a substantial contribution of methanotrophic archaea26. However, both proxies should be applied cautiously in lacustrine settings. Water depth can influence the GDGT-0/crenarchaeol ratio68,69, and MI was primarily used for marine environments26,70. Indeed, higher GDGT-0/crenarchaeol ratios typically correlate with shallower water depths68,69. However, evidence of fine laminations observed in the Jianghan Basin during the PETM suggests an increased lake level16. This interpretation contradicts the concurrent PETM increase in the GDGT-0/crenarchaeol ratio, implying that the ratio primarily reflects variations in methane cycling within the Jianghan paleolake25. While MI was initially developed for marine systems26,70, its biochemical basis—archaeal membrane lipid adaptations to methane metabolism—represents a universal archaeal response to methane availability. This principle supports its applicability to anoxic lacustrine systems hosting similar microbial consortia71,72. Furthermore, a recent study suggests that lakes with extremely low sulfate concentration could provide potential analogs of marine systems and applicability of MI–methane flux reconstruction70. Given evidence for a relatively low sulfate environment in the Jianghan paleolake16, MI is therefore appropriate for tracking methane cycling in this setting70. At the Longwangjing section, the concurrent increase in GDGT-0/Crenarchaeol ratio (up to ~100) and MI values (up to ~0.8) across the PETM (Fig. 4G, H) highlights a shift toward methanogen-dominated archaeal communities. This transition implies that methane production became a dominant pathway in lacustrine carbon cycling. The intensified methane cycling during the PETM could be attributed to synergistic interactions between climatic warming, hydrological changes, and biogeochemical feedbacks. First, elevated global temperatures likely enhanced microbial methanogenesis in lake sediments by increasing metabolic rates of methanogenic archaea, which thrive under warmer conditions73. Second, increased organic matter input from intensified terrestrial runoff (as indicated by oleanane index) (Fig. 4C) and in situ algal productivity (as indicated by steroids/hopanes index) (Fig. 4D), leading to greater organic carbon burial (as evidenced by high TOC up to ~5%) (Fig. 3A) and subsequent anaerobic degradation—a key substrate for methanogenesis74. Third, widespread lake bottom-water hypoxia, evidenced by laminated sediments and geochemical proxies (Pr/Ph, Mo, and U), would have favored anaerobic methane production and potentially anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) coupled to sulfate or iron reduction16,75,76. The enhanced methane cycling not only reflects local biogeochemical changes but also underscores its potential role in global carbon-climate feedbacks. The net flux of biogenic methane into the atmosphere is primarily governed by the balance between methane production (methanogenesis) and methane oxidation (methanotrophy)77,78,79. Warming tends to increase net methane emissions because methanogenesis exhibits greater sensitivity to temperature increments than methanotrophy77,79. This disproportionate increase in methanogenesis over methanotrophy under warming conditions is well-documented by both field studies and laboratory experiments73,77. Quantitatively, a data-driven model indicates that a 2 °C increase in lake water temperature can elevate net methane emissions by 47–183%79. If this empirical relationship between temperature and methane emissions is linearly extrapolated to ancient lake systems, the total methane emissions from the paleolake could potentially have increased at least twofold in response to the ~8°C warming during the PETM. A similar scenario of methane emissions was recently proposed for the Early Permian (~286 Ma)80, the early Toarcian (~183 Ma)46, and the Cretaceous Oceanic Anoxic Event 1a (~120 Ma) warming81. These findings suggest that an intensified lacustrine methane cycling is a universal phenomenon in a warming world. Given that methane is a potent greenhouse gas, with a warming potential 27 times higher than CO21, the heightened release of methane from lakes likely served as a positive feedback mechanism for the PETM warming. While our data suggest that methane production in anoxic lake bottoms potentially contributed to PETM warming, other mechanisms—such as marine hydrate dissociation4, thermogenic methane release6, and wetland/permafrost methane emissions7,82,83—likely played concurrent roles in global carbon cycle perturbations. Further modeling efforts are needed to evaluate the relative significance of these feedbacks. Additionally, the anoxic conditions that promoted methanogenesis in our study site may have simultaneously enhanced carbon burial in other lacustrine systems, highlighting the complex role of lakes in the PETM carbon budget.

Implications for the impact of past and future warming on lakes

The PETM sedimentary record from the Jianghan Basin reveals a cascade of interconnected limnological responses to abrupt warming, offering critical lessons for understanding both past and future climate-lake interactions. The observed intensification of the hydrological cycle aligns with modern projections of increased precipitation extremes in a warmer world1. Enhanced runoff likely delivered greater fluxes of terrestrial nutrients (e.g., phosphorus, nitrogen) and organic matter to lakes (Fig. 5), as inferred from elevated organic carbon concentrations in PETM sediments (Fig. 3A). Increased nutrient availability could initially boost aquatic productivity as evidenced by elevated organic biomarkers, reflected in biomarker records of algal blooms (Figs. 4D and 5B). However, sustained warming and stratification may ultimately decouple nutrient recycling from biological demand, leading to ecological instability84. As surface waters warm, thermal stratification intensifies, reducing vertical mixing and the upward flux of nutrients to the epilimnion2,84. This decoupling can starve primary producers, shifting ecosystems toward smaller, nutrient-efficient species (e.g., cyanobacteria) and destabilizing food webs16,84.

The development of persistent thermal stratification and hypoxic/anoxic bottom waters during the PETM highlights a critical threshold in lake responses. Prolonged stratification inhibits vertical mixing, trapping organic matter in the hypolimnion and promoting oxygen depletion through microbial respiration85,86. This oxygen-starved environment favors anaerobic microbial metabolisms, including methanogenesis, as indicated by elevated GDGT-0/Crenarchaeol ratio and MI values (Fig. 4G, H). Enhanced methane production under hypoxia creates a positive feedback loop (Fig. 5B), as methane emissions amplify atmospheric warming – a process particularly concerning given modern lakes already contribute ~20% of natural methane emissions87.

Importantly, modern lakes face compounding stressors absent during the PETM, including anthropogenic eutrophication and faster warming rates8,88. While PETM-like stratification and hypoxia may develop naturally under warming, excessive nutrient loading from agriculture and urbanization could exacerbate deoxygenation, pushing lakes into unprecedented ecological states85. For example, synergistic effects between climate-driven warming and eutrophication have already expanded hypoxic zones in global lakes85,89. Furthermore, the PETM record suggests that warming and prolonged hypoxia may drive taxonomic shifts toward low-oxygen-tolerant species (e.g., certain cyanobacteria)16, reducing biodiversity and altering food web dynamics – a pattern mirrored in modern hypoxic lakes90.

These paleo-environmental insights underscore the urgency of integrating lakes into climate mitigation strategies. If future warming follows PETM-like trajectories, lakes may transition from carbon sinks to sources, with methane emissions offsetting carbon burial91. However, targeted management—such as reducing nutrient pollution and slowing down global warming—could enhance lake resilience by mitigating stratification and oxygen loss9,88. Future research should prioritize quantifying lake methane fluxes and their climate feedback contributions, while integrating paleoenvironmental data with model simulations to improve predictive capabilities for lacustrine carbon cycle dynamics.

Methods

Extraction and separation

The samples analyzed in this study were collected from the Longwangjing section (30°06′10″N, 111°38′26″E) in Jingzhou City, Hubei Province, eastern China (Fig. 1). Forty-five samples were collected for biomarker analyses. Approximately 10–30 g of powder sample was extracted using an accelerated solvent extractor (ASE 350) with a solvent mixture of dichloromethane (DCM) and methanol (MeOH) (9:1, v/v). Elemental sulfur in the total lipid extract (TLE) was removed using activated copper turnings. The TLE was condensed by rotary evaporation and subsequently separated into to saturated, aromatic, and polar fractions using alumina/silica-gel column chromatography, through sequential elution with hexane, DCM:hexane (2:1, v/v), and DCM:methanol (1:1, v/v).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Biomarker analysis

The saturated fractions were analyzed by gas chromatograph/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) and gas chromatograph/isotope ratio mass spectrometry (GC/IRMS) at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS). The GC/MS used an Agilent 7890(GC) coupled to Agilent 5975i (MS) with an HP-5 MS fused silica column (30 m × 0.25 mm inner diameter with a 0.25 µm film coating). The injection port temperature was 300 °C. The temperature program includes four stages: 50 °C hold for 1 min, 50 °C to 120 °C at 20 °C/min, 120 °C to 310 °C at 3 °C/min, and finally maintained at 310 °C for 20 min. The MS was operated in electron impacting (EI) with an ionization energy of 70 eV, scanning a mass range of m/z 5–600. nD50C24 was added as a standard for quantitative analysis. The identification of biomarkers was based on mass spectra and retention times (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Compound-specific δ13C analysis

Compound-specific δ13C (GC/IRMS part) were analyzed on a ThermoFisher DELTA V plus, and the column conditions and temperature program of GC were the same as described above for GC/MS analyses. Samples were measured in duplicate with a reproducibility typically <0.6‰. The standard USGS-67 n-hexadecane with a δ13C value of -34.50‰ V-PDB (Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite) was used for compound-specific δ13C during the analysis and the reproducibility on the standards is better than ±0.3‰.

GDGT analysis and temperature reconstruction

The polar fraction, containing the GDGTs, was dried, re-dissolved in hexane, and filtered over a 0.45 μm PTFE filter prior to analysis. GDGTs were analyzed using an Agilent 1200 series high-performance liquid chromatography-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization mass spectrometry (HPLC-APCI-MS). Separation of GDGTs was achieved with two coupled Inertsil SIL-100A silica columns (each 250 mm ×4.6 mm, 3μm; GL sciences Inc.) using isopropanol and n-hexane as elutes, following the new chromatography methods capable of separating 5-methyl and 6-methyl brGDGTs14. Archaeol, the isoprenoidal GDGTs, and branched GDGTs were detected in selected ion monitoring mode, and quantified by integration of the peak area of [M + H]+ ions in the extracted ion chromatogram.

In order to quantify paleo-temperatures, we calculated the Methylation of Branched Tetraether (MBT’5ME) index21:

Roman numerals correspond to molecular brGDGT structures shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. The MBT’5ME is translated into MATs using newly developed pantropical temperature calibration (RMSE = 2.26 °C)29:

Duplicate analyses as well as analyses of an internal laboratory standard throughout the runs yielded an error of 0.009 MBT’5ME (1-sigma), which would translate into a temperature error of ≤0.3 °C, negligible relative to the calibration error.

Data availability

The data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the Supplementary Materials. All data are available through SCIENCE DATA BANK, which can be accessed through https://www.scidb.cn/s/JNfqqa.

References

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Ed. Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom, 2023).

Woolway, R. I. et al. Global lake responses to climate change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 388–403 (2020).

McInerney, F. A. & Wing, S. L. The Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum: a perturbation of carbon cycle, climate, and biosphere with implications for the future. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 39, 489–516 (2011).

Dickens, G. R., O’neil, J. R., Rea, D. K. & Owen, R. M. Dissociation of oceanic methane hydrate as a cause of the carbon isotope excursion at the end of the Paleocene. Paleoceanography 10, 965–971 (1995).

Gutjahr, M. et al. Very large release of mostly volcanic carbon during the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Nature 548, 573–577 (2017).

Frieling, J. et al. Thermogenic methane release as a cause for the long duration of the PETM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa 113, 12059–12064 (2016).

DeConto, R. M. et al. Past extreme warming events linked to massive carbon release from thawing permafrost. Nature 484, 87–91 (2012).

Zeebe, R., Ridgwell, A. & Zachos, J. Anthropogenic carbon release rate unprecedented during the past 66 million years. Nat. Geosci. 9, 325–329 (2016).

Williamson, C. E., Saros, J. E. & Schindler, D. W. Sentinels of change. Science 323, 887–888 (2009).

Smith, T., Rose, K. D. & Gingerich, P. D. Rapid Asia–Europe–North America geographic dispersal of earliest Eocene primate Teilhardina during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 11223–11227 (2006).

Bowen, G., Beerling, D., Koch, P., Zachos, J. C. & Quattlebaum, T. A humid climate state during the Palaeocene/Eocene thermal maximum. Nature 432, 495–499 (2004).

Wing, S. L. et al. Transient floral change and rapid global warming at the Paleocene-Eocene boundary. Science 310, 993–996 (2005).

Sluijs, A. et al. Environmental precursors to rapid light carbon injection at the Palaeocene/Eocene boundary. Nature 450, 1218–1221 (2007).

Yao, W. et al. Expanded subsurface ocean anoxia in the Atlantic during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Nat. Commun. 15, 9053 (2024).

Tranvik, L. J. et al. Lakes and reservoirs as regulators of carbon cycling and climate. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 2298–2314 (2009).

Chen, Z. et al. Freshwater ecosystem collapse and mass mortalities at the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum. Glob. Planet. Change 227, 104175 (2023).

Zhang, J. & Wilson, M. V. H. First complete fossil Scleropages (Osteoglossomorpha). Vertebrata Palasiat. 55, 1–23 (2017).

Lei, Y. in Biostratigraphy of the Yangtze Gorge Area (5) Cretaceous and Tertiary (ed. Yichang Institute of Geology and Mineral Resources) 60–80 (Geological Publishing House, 1987).

Ni, X. et al. The oldest known primate skeleton and early haplorhine evolution. Nature 498, 60–64 (2013).

Chen, Z. et al. Two sites in East Asia add to spatiotemporal heterogeneity of wildfire activity across the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL113829 (2025).

De Jonge, C. et al. Occurrence and abundance of 6-methyl branched glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers in soils: implications for palaeoclimate reconstruction. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 141, 97–112 (2014).

Inglis, G. N. et al. Biomarker approaches for reconstructing terrestrial environmental change. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 50, 369–394 (2022).

Peters, K. E., Walters, C. C. & Moldowan, J. M. The Biomarker Guide, vol. 1 (Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom, 2005).

Sinninghe et al. Evidence for gammacerane as an indicator of water column stratification. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 1895–1900 (1995).

Blaga, C. I., Reichart, G. J., Heiri, O. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Tetraether membrane lipid distributions in water-column particulate matter and sediments: a study of 47 European lakes along a north-south transect. J. Paleolimnol. 41, 523–540 (2009).

Zhang, Y. et al. Methane Index: A tetraether archaeal lipid biomarker indicator for detecting the instability of marine gas hydrates. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 307, 525–534 (2011).

Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., Hopmans, E. C., Pancost, R. D., Schouten, S. & Geenevasen, J. A. J. Newly discovered non-isoprenoid glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraether lipids in sediments. Chem. Commun. 1683–1684 (2000).

Weijers, J. W. H., Schouten, S., van den Donker, J. C., Hopmans, E. C. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Environmental controls on bacterial tetraether membrane lipid distribution in soils. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 703–713 (2007).

Zhao, B. et al. Evaluating global temperature calibrations for lacustrine branched GDGTs: Seasonal variability, paleoclimate implications, and future directions. Q. Sci. Rev. 310, 108124 (2023).

Hopmans, E. C., Schouten, S. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. The effect of improved chromatography on GDGT-based palaeoproxies. Org. Geochem. 93, 1–6 (2016).

Xie, Y., Wu, F. & Fang, X. A transient south subtropical forest ecosystem in central China driven by rapid global warming during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Gondwana Res. 101, 192–202 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Structure of the carbon isotope excursion in a high-resolution lacustrine Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum record from Central China. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 408, 331–340 (2014).

de Wet, G. A., Castañeda, I. S., DeConto, R. M. & Brigham-Grette, J. A high-resolution mid-Pleistocene temperature record from Arctic Lake El’gygytgyn: a 50 kyr super interglacial from MIS 33 to MIS 31. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 436, 56–63 (2016).

Inglis, G. N. et al. Terrestrial environmental change across the onset of the PETM and the associated impact on biomarker proxies: a cautionary tale. Glob. Planet. Change 181, 102991 (2019).

Leng, M. J. & Marshall, J. D. Palaeoclimate interpretation of stable isotope data from lake sediment archives. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 811–831 (2004).

Dunkley et al. Climate model and proxy data constraints on ocean warming across the Paleocene-Eocene thermal Maximum. Earth Sci. Rev. 125, 123–145 (2013).

Seltzer, A. M., Blard, P. H., Sherwood, S. C. & Kageyama, M. Terrestrial amplification of past, present, and future climate change. Sci. Adv. 9, 1–9 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. Spatial change of precipitation in response to the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum warming in China. Glob. Planet. Change 194, 103313 (2020).

Meijer, N. et al. Proto-monsoon rainfall and greening in Central Asia due to extreme early Eocene warmth. Nat. Geosci. 17, 158–164 (2024).

Pagani, M., Caldeira, K., Archer, D. & Zachos, J. C. An ancient carbon mystery. Science 314, 1556–1557 (2006).

Tipple, B. J. & Pagani, M. The early origins of terrestrial C4 photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 35, 435–461 (2007).

Diefendorf, A. F. & Freimuth, E. J. Extracting the most from terrestrial plant-derived n-alkyl lipids and their carbon isotopes from the sedimentary record: a review. Org. Geochem. 103, 1–21 (2017).

Schubert, B. A. & Jahren, A. H. The effect of atmospheric CO2 concentration on carbon isotope fractionation in C3 land plants. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 96, 29–43 (2012).

ten Haven, H. L., de Leeuw, J. W., Rullkötter, J. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Restricted utility of the pristane/phytane ratio as a palaeoenvironmental indicator. Nature 330, 641–643 (1987).

Schouten, S. et al. Biosynthetic effects on the stable carbon isotopic compositions of algal lipids: Implications for deciphering the carbon isotopic biomarker record. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 62, 1397–1406 (1998).

Huang, Y., Jin, X., Pancost, R. D., Kemp, D. B. & Naafs, B. D. A. An intensified lacustrine methane cycle during the Toarcian OAE (Jenkyns event) in the Ordos Basin, northern China. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 639, 118766 (2024).

Hayes, J. M., Freeman, K. H., Popp, B. N. & Hoham, C. H. Compound-specific isotopic analyses: a novel tool for reconstruction of ancient biogeochemical processes. Org. Geochem. 16, 1115–1128 (1990).

Riva, A., Caccialanza, P. G. & Quagliaroli, F. Recognition of 18B(H)oleanane in several crudes and Tertiary-Upper Cretaceous sediments. Definition of a new maturity parameter. Org. Geochem. 13, 671–675 (1988).

Li, M. et al. Coupled decline in ocean pH and carbonate saturation during the Palaeocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum. Nat. Geosci. 17, 1299–1305 (2024).

ten Haven, H. L., Rohmer, M., Rullkötter, J. & Bisseret, P. Tetrahymanol, the most likely precursor of gammacerane, occurs ubiquitously in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 5, 3073–3079 (1989).

Hanisch, S., Ariztegui, D. & Püttmann, W. The biomarker record of Lake Albano, central Italy–implications for Holocene aquatic system response to environmental change. Org. Geochem. 34, 1223–1235 (2003).

Xu, Y. & Jaffé, R. Biomarker-based paleo-record of environmental change for an eutrophic, tropical freshwater lake, Lake Valencia, Venezuela. J. Paleolimnol. 40, 179–194 (2008).

Castañeda, I. S., Werne, J. P., Johnson, T. C. & Powers, L. A. Organic geochemical records from Lake Malawi (East Africa) of the last 700 years, part II: Biomarker evidence for recent changes in primary productivity. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 303, 140–154 (2011).

Stüeken, E. E., Buick, R. & Schauer, A. J. Nitrogen isotope evidence for alkaline lakes on late Archean continents. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 411, 1–10 (2015).

Adrian, R. et al. Lakes as sentinels of climate change. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 2283–2297 (2009).

Woolway, R. I. & Merchant, C. J. Worldwide alteration of lake mixing regimes in response to climate change. Nat. Geosci. 12, 271–276 (2019).

Jankowski, T., Livingstone, D. M., Bührer, H., Forster, R. & Niederhauser, P. Consequences of the 2003 European heat wave for lake temperature profiles, thermal stability, and hypolimnetic oxygen depletion: Implications for a warmer world. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 815–819 (2006).

Kraemer, B. M. et al. Morphometry and average temperature affect lake stratification responses to climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 4981–4988 (2015).

Woolway, R. I. et al. Phenological shifts in lake stratification under climate change. Nat. Commun. 12, 2318 (2021).

Pilla, R. M. et al. Browning-related decreases in water transparency lead to long-term increases in surface water temperature and thermal stratification in two small lakes. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 123, 1651–1665 (2018).

Rimmer, A., Gal, G., Opher, T., Lechinsky, Y. & Yacobi, Y. Z. Mechanisms of long-term variations in the thermal structure of a warm lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 974–988 (2011).

Schouten, S., Hopmans, E. C. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. The organic geochemistry of glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraether lipids: a review. Org. Geochem. 54, 19–61 (2013).

Sinninghe et al. The enigmatic structure of the crenarchaeol isomer. Org. Geochem. 124, 22–28 (2018).

Pancost, R. D., Hopmans, E. C. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Archaeal lipids in Mediterranean cold seeps: molecular proxies for anaerobic methane oxidation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 1611–1627 (2001).

Blumenberg, M., Seifert, R., Reitner, J., Pape, T. & Michaelis, W. Membrane lipid patterns typify distinct anaerobic methanotrophic consortia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 11111–11116 (2004).

Rossel, P. E. et al. Intact polar lipids of anaerobic methanotrophic archaea and associated bacteria. Org. Geochem. 39, 992–999 (2008).

Bauersachs, T., Weidenbach, K., Schmitz, R. A. & Schwark, L. Distribution of glycerol ether lipids in halophilic, methanogenic and hyperthermophilic archaea. Org. Geochem. 83, 101–108 (2015).

Wang, H., Leng, Q., Liu, W. & Yang, H. A rapid lake-shallowing event terminated preservation of the Miocene Clarkia Fossil Konservat-Lagerstatte (Idaho, USA). Geology 45, 239–242 (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Lake Water Depth Controlling Archaeal Tetraether Distributions in Midlatitude Asia: Implications for Paleo Lake-Level. Reconstruction. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5274–5283 (2019).

Kim, B. & Zhang, Y. Methane Index: Towards a quantitative archaeal lipid biomarker proxy for reconstructing marine sedimentary methane fluxes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 354, 47–87 (2023).

Daniels, W. C. et al. Archaeal lipids reveal climate-driven changes in microbial ecology at Lake El’gygytgyn (Far East Russia) during the Plio-Pleistocene. J. Quat. Sci. 37, 900–914 (2022).

Collins, E. R. A Biomarker-based Reconstruction and Comparison of The Microbial Ecology of Ancient Lake Magadi and Modern Nasikie Engida in the East African Rift Valley. 1–133 (Doctoral thesis, University of Pittsburgh, 2023).

Yvon-Durocher, G. et al. Methane fluxes show consistent temperature dependence across microbial to ecosystem scales. Nature 507, 488–491 (2014).

Grasset, C. et al. Large but variable methane production in anoxic freshwater sediment upon addition of allochthonous and autochthonous organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr. 63, 1488–1501 (2018).

Dean, J. F. et al. Methane feedbacks to the global climate system in a warmer world. Rev. Geophy. 56, 207–250 (2018).

Hounshell, A. G., McClure, R. P., Lofton, M. E. & Carey, C. C. Whole-ecosystem Oxygenation Experiments Reveal Substantially Greater Hypolimnetic Methane Concentrations in Reservoirs during Anoxia. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 6, 33–42 (2021).

Zhu, Y. et al. Disproportionate increase in freshwater methane emissions induced by experimental warming. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 685–690 (2020).

Borrel, G. et al. Production and consumption of methane in freshwater lake ecosystems. Res. Microbiol. 162, 832–847 (2011).

Sepulveda-Jauregui, A. et al. Eutrophication exacerbates the impact of climate warming on lake methane emission. Sci. Total Environ. 636, 411–419 (2018).

Sun, F. et al. Sustained and intensified lacustrine methane cycling during Early Permian climate warming. Nat. Commun. 13, 4856 (2022).

Sun, F. et al. Methane fueled lake pelagic food webs in a Cretaceous greenhouse world. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2411413121 (2024).

Inglis, G. N. et al. Terrestrial methane cycle perturbations during the onset of the Palaeocene-Eocene thermal maximum. Geology 49, 520–524 (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. Wetland methane feedback during the early Eocene hyperthermals. Geology 53, 404–408 (2025).

O’Reilly, C. M., Alin, S. R., Plisnier, P.-D., Cohen, A. S. & McKee, B. A. Climate change decreases aquatic ecosystem productivity of Lake Tanganyika, Africa. Nature 424, 766–768 (2003).

Jane, S. F. et al. Widespread deoxygenation of temperate lakes. Nature 594, 66–70 (2021).

Hessen, D. O. et al. Lake ecosystem tipping points and climate feedbacks. Earth Syst. Dynam. 15, 653–669 (2024).

Rosentreter, J. A. et al. Half of global methane emissions come from highly variable aquatic ecosystem sources. Nat. Geosci. 14, 225–230 (2021).

Beaulieu, J. J., DelSontro, T. & Downing, J. A. Eutrophication will increase methane emissions from lakes and impoundments during the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 10, 1375 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Shi, K., Woolway, R. I., Wang, X. & Zhang, Y. Climate warming and heatwaves accelerate global lake deoxygenation. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt5369 (2025).

Kraemer, B. M. et al. Climate change drives widespread shifts in lake thermal habitat. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 521–529 (2021).

Bastviken, D., Tranvik, L. J., Downing, J. A., Crill, P. M. & Enrich-Prast, A. Freshwater methane emissions offset the continental carbon sink. Science 331, 50–50 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Strategy Priority Research Program (Category B) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB0710000), the National Key R & D Program of China (2022YFF0800800 and 2023YFF0803500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42372210 and 92479208), and Open Fund Project of the State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution (SKL-K202301). Sampling permissions were not required. We thank Niels Meijer and an anonymous reviewer for their suggestions and constructive comments that improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.C. and Z.D. designed this study. Z.C., J.S., and X.N. collected samples. Z.C. and P.L. performed geochemical analyses. Z.C. drafted the manuscript with major input from S.Y., J.S., X.N., C.L., L.G., and Z.D. All co-authors contributed to interpreting the data and writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Haihan Zhang and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Lü, P., Yang, S. et al. Extreme warming intensified lacustrine deoxygenation and methane cycling during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Commun Earth Environ 6, 592 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02597-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02597-3

This article is cited by

-

Satellites reveal widespread deoxygenation of large global reservoirs from 1984 to 2023

Scientific Reports (2025)