Abstract

Indigenous Territories are crucial for preserving biodiversity, particularly in tropical regions, yet their contribution to human health is poorly understood. Using 20 years of data on fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne diseases, we evaluated how Indigenous Territories, their legal recognition status, and landscape parameters affected disease incidence in the Amazon biome. Overall, we found that Indigenous Territories extent had complex and non-linear effects, with a potential to reduce fire-related disease incidence and to increase zoonotic/vector-borne diseases, depending on the local landscape structure. For instance, Indigenous Territories within municipalities with high forest cover outside their boundaries can mitigate the impacts of particulate matter with less than 2.5 micrometer on human health and reduce the incidence of fire-related diseases. For zoonotic/vector-borne diseases, both forests inside and outside Indigenous Territories, when covering over 40% of a municipality, can contribute to reducing the negative effects from edge density on disease incidence. Our findings emphasize the complex relationships between conservation and human health, which vary based on the local context and Indigenous Territories legal recognition, and underscores the importance of Indigenous Territories and their legal acknowledgment for supporting ecosystem and human health, particularly in landscapes with high forest integrity and low fragmentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Indigenous people represent 6% of the world’s population1 and administer or have tenure rights over at least ~38 million km2 of land, mainly in the tropics and subtropics2, through indigenous territories (ITs, areas of land and associated resources traditionally occupied and used by indigenous people, which may or may not be officially recognized by the state). Their deep-rooted, collective ancestral relationship with native lands and natural resources—based on beliefs, practices, knowledge systems, and social norms3,4—led to presumed sustainable ways of living with nature3,5, although those equilibria are fragile and may be weakened by socio-economic and environmental changes6, leading to animal population collapses7. Nevertheless, a growing body of evidence shows that indigenous-managed lands are largely forest covered8, especially when legally held or titled9. Indigenous Territories therefore contribute to curb deforestation8,10,11,12,13 and slow biodiversity loss14, underscoring the need to recognize and support Indigenous rights globally.

An estimated 33 million people live in the Amazon biome, from these, 2.7 million are indigenous people representing approximately 350 ethnic groups15. Covering around seven million square kilometers and spanning nine South American countries, the Amazon biome is the most biodiverse region on earth16,17, with a quarter of the Planet’s biodiversity and half of the world’s remaining tropical forests18,19. The protection of this region is key not only for biodiversity conservation20 but also for the provision of key ecosystem services to humans, such as freshwater supply21, carbon sequestration and climate regulation22,23. For example, an estimated 100 billion tons of Carbon are stored in the Amazon forests24,25, which is equivalent to more than ten years of global fossil-fuel emissions.

This region is also threatened by human actions, such as agricultural production, oil extraction26, mining, among others, having the highest deforestation rates in the world27,28, which resulted in an estimated loss of 30.7 million hectares of primary forest in the last 20 years29. Much of this deforestation happens through the clear-cut and burn of the forests, where forest is first clear-cut, left to dry for weeks or months, and then set on fire to remove biomass30. This results in the complete removal of forest vegetation over large expanses of land which are then used for pasture or agriculture31. In addition to contributing to deforestation, these fires also release large amounts of carbon dioxide, particulate matter (PM) and trace gasses, contributing to climate change32 and negatively affecting human health33,34.

Fires in tropical and subtropical regions are responsible for 90% of global PM2.5 emissions35), PM with an aerodynamic median diameter smaller than 2.5 μm, degrades regional air quality affecting the human population’s respiratory health36,37. Specifically, 9.1 g of PM2.5 are emitted per kg of dry matter burned in tropical forests38. Human population exposure to smoke from forest fires is associated with increased respiratory symptoms, heart disease, stroke, emphysema, and lung cancer, as well as bronchitis, asthma, chest pain, chronic lung and heart problems, and increases in the risk of death39. As a consequence, in the Amazon, smoke from forest fires has been related to an increasing number of people hospitalized with respiratory system diseases40. For instance, in the Brazilian Amazon, more than 24 new fire-related disease cases are estimated to occur for every 1 kg increase of PM2.537, while between 2002 and 2011, deforestation fires were responsible for, on average, 2906 premature deaths from cardiopulmonary disease and lung cancer36.

However, the health impacts of deforestation and land use change are not limited to the haze from fires. Recent approximations attribute as much as 23% of global deaths and 22% of global disability adjusted life years to poor environmental quality, including land-use patterns41. For instance, in Brazil, 18% of the total annual disease burden would be preventable through healthier environments42. More specifically, land-use change stands as the leading driver for emerging zoonotic infectious diseases43,44,45. Deforestation alters the niche of vectors, hosts, and pathogens, changing their community composition, behaviors, movements, and spatial distribution46,47, and forcing them to live in closer proximity to humans. Deforestation also leads to fragmentation, altering the configuration of the remaining forest areas48. For instance, fragmentation is associated with increased forest edges, which can positively affect the abundance of several vectors49, increasing the transmission risks of pathogens linked to these vectors (the “perturbation hypothesis”)50,51,52. The creation of forest edges is also linked to increased contacts between humans and infected wildlife53,54. In those ways, forest conservation could potentially play a fundamental role in buffering against disease outbreaks.

Growing evidence suggests that Indigenous Territories play a crucial role in buffering against anthropogenic threats and preserving tropical forests and their ecosystem services2,55. However, their role in safeguarding human health is still less understood (but see refs. 37, 56). To fill this gap and considering the nine countries encompassing the Amazon biome, we first examined whether cases of fire-related disease were associated with the amount of PM2.5 released by forest fires. Then, we assessed (a) the inter-related effects between the extent of ITs, forest outside ITs, overall forest cover, as well as that of forest fragmentation metrics (i.e., edge density, patch density and an aggregation index) on the incidence of fire-related (respiratory and cardiovascular) and zoonotic/vector-borne diseases (i.e., malaria, cutaneous leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, hantavirus, rickettsia and visceral leishmaniasis), and (b) the importance of the legal recognition status of ITs on the overall, fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne disease incidence. Overall, despite the relationship between ITs and disease incidence to be complex, we expect municipalities with higher forest cover and lower fragmentation would reduce disease incidence, especially when associated with legally recognized Indigenous territory (Fig. 1). We also hypothesized that ITs that are legally recognized offer greater co-benefits for human health due to eventually reduced exploitation and higher forest integrity than unrecognized ITs. This study is the first to evaluate the human health benefits of indigenous lands throughout the Amazon biome, highlighting the complexity of these relationships in the face of different contexts of landscape structure, the legal status of indigenous lands and the trade-offs that exist between different diseases.

The diagram outlines the relationships between ITs, forest fragmentation and forest cover (overall, within and outside ITs) on disease outcomes. Hypotheses elaborate on single, additive and interactive effects of ITs, forest fragmentation and forest cover, evaluating how these factors together or independently affect disease incidence. Each of the models considered and corresponding hypotheses are described in Supplementary Table 1.

Results

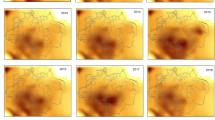

A total of 28,429,422 cases of 21 diseases, with an incidence rate of 556.96 per 100,000 people, were reported across the Amazon between 2001 and 2019. Fire-related diseases accounted for 80.3% (22,821,426 cases), with respiratory diseases being the most prevalent (79.4%), while cardiovascular diseases made up only 0.87%. Vector-borne/zoonotic diseases comprised 19.7% (5,607,996 cases), with malaria representing 92.62% of these. Venezuela, Suriname, and Peru exhibited the highest overall incidences (Fig. 2), with Venezuela reporting the highest incidence of zoonotic/vector-borne diseases, namely malaria (Fig. 2e). Other zoonotic/vector-borne diseases such as cutaneous leishmaniasis (5.57%), Chagas disease (1.60%), and visceral leishmaniasis (0.12%) were less common (Fig. 2e–j). Disease temporal trends showed high variability, with respiratory diseases peaking in 2004 and malaria in 2005, 2008, and 2017. Cases of Chagas and hantavirus have declined recently, while rickettsia cases have remained steady since 2007 (Fig. 2).

Overall incidence of (a) fire-related diseases and (b) zoonotic/vector-borne diseases, both averaged by the number of diseases reported by each country and by the number of years. Panels (c–j) show the incidences of each disease separately—(c) only cardiovascular diseases, averaged by the number of diseases reported by each country and the number of years; d only respiratory diseases, averaged by the number of diseases reported by each country and the number of years; e malaria; f cutaneous leishmaniasis, g Chagas disease; h hantavirus, i rickettsia, j visceral leishmaniasis. Temporal patterns of the number of fire-related diseases (green) and zoonotic/vector-borne (red) diseases reported in the Amazon from 2001 to 2019 are also shown.

During the same period, 532,571 km² of the Amazon burned, averaging 28,030 km² annually. Brazil had the largest burned area (372,281 km²), followed by Bolivia (121,189 km²) and Colombia (21,956 km²). Proportionally, Bolivia experienced the highest burn extent, with nearly 16% of its Amazon area affected, compared to 8.6% in Brazil and 4% in Colombia (Fig. 3a). The accumulated burned area, including repeated fires, reached 923,784 km², with nearly 30% of the Bolivian and 15% of the Brazilian Amazon affected. The highest number of fires was in 2010 (Fig. S1) and, on average, areas burned 18 times, indicating frequent fires (Fig. 3a). Most fires (~88.7%) occurred outside Indigenous territories, with 11.3% within, 7.5% in recognized areas, and 3.7% in unrecognized territories (Fig. 3b).

These fires produced around 1236 tons/m³ of PM2.5, with a strong correlation between calibrated AOD-PM2.5 and fire activity (r > 0.92), potentially impacting populations within 500 km of the fire events37. On average, 65 tons/year/m³ of PM2.5 accumulated every 500 km annually, with 2007, 2010, and 2005 having the highest concentrations (Fig. S2). Brazil had the highest levels, with 45 tons/year/m³, followed by Peru (7.21 tons) and Bolivia (6.33 tons). Residual analysis indicated that Brazil, Colombia, and French Guiana had less accumulated PM2.5 than expected given the number of fires, while Peru and Suriname had more (Fig. S3). This suggests that fire impacts are a cross-boundary issue that needs to be understood at a biome level.

The amount of PM2.5 positively explained the number of reported cases of fire-related diseases (Fig. 4a). This effect is more pronounced for respiratory (Fig. 4b) than cardiovascular diseases (Fig. 4c). For cardiovascular diseases, the model considering the accumulated amount of PM2.5 over a 5-year period showed the best performance, suggesting that cardiovascular diseases can be associated with constant and accumulated exposure to PM2.5 in order to manifest.

Being largely forest covered, the extent of ITs can be associated with human health, having complex non-linear and specific effects for each disease evaluated (Table 1, Fig. 5). For overall fire-related diseases, the model that best explained incidence contained the interactive effects between forest inside and outside ITs (including the orthogonal polynomial of the latter), in addition to the additive effect of edge density (Table 1, Fig. 6; Supplementary Table 2 shows the set of models tested). ITs’ effects were nonlinear (β [IT2] = 4.178), varying according to both the amount and fragmentation degree of forests non managed by indigenous (β [forest outside IT2 * IT] = -9.714): in contexts with low and intermediate amounts of forest cover (15– 45%), ITs can be associated with increases in the incidence of fire-related diseases. However, in high forest cover contexts (>45%), ITs can mitigate PM2.5 impacts on human health, being associated with a decrease in fire-related disease incidences. These relationships remain consistent as edge density increases (β [edge density] = 0.106), but disease incidence is proportionally higher when edge densities rise (Supplementary Table 2, Fig. 6a), showing a detrimental effect of forest fragmentation on fire-related disease incidences. A similar pattern was observed for respiratory diseases (Supplementary Table 3, Fig. 6b).

Effect sizes displayed correspond to estimates from the best-supported models. Fire-related diseases were disaggregated in both respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Zoonotic/vector-borne diseases were disaggregated in malaria, cutaneous leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, hantavirus, rickettsia and visceral leishmaniasis. Disease incidence was log10-transformed except for Chagas disease, hantavirus, rickettsia and visceral leishmaniasis for which we considered disease occurrence. Predictor variables included the proportions of indigenous territories (IT), forest cover outside the IT, overall forest cover and the orthogonal polynomials of these (ˆ2), edge density, patch density and the interaction terms between two pairs of predictor variables. Circles are sized according to the estimate obtained from ‘best’ models (see further details on model selection and the full summary of the ‘best’ model in Tables S2 and S3, respectively). Blue and yellow circles denote positive and negative estimates, respectively.

Panels represent predicted incidences for (a) overall fire-related, b respiratory and (c) cardiovascular diseases. The lines indicate predictions, and shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. Each panel set highlights a different interaction between forest cover. In (a) and (b), columns display levels of edge density (low: 10, medium: 25, and high: 50), and the lines are patterned (color and linetype) according to the levels of forest cover outside Indigenous Territories: 15% (light green, dotted), 45% (medium green, dashed), and 75% (dark green, solid). In (c), columns display levels of Indigenous Territories coverage (low: 15%, medium: 45%, high: 75%). Lines are patterned according to edge density: low (10; olive green, solid), medium (20; brownish yellow, dashed), and high (50; light mustard, doted).

For cardiovascular diseases, the best model included the interactive effects between the extent of forest outside ITs (along with the orthogonal polynomial) and edge density, as well as the additive effect of the extent of ITs (and its orthogonal polynomial) (Table 1). This shows that habitat fragmentation is associated with increases in the incidence of cardiovascular diseases (β [edge density] = 0.106). However, those effects can be more prominent in municipalities with low IT extent. In addition, as forest outside ITs increases, cardiovascular disease incidence decreases (β [forest outside IT] = -5.523), except in municipalities with high fragmentation (i.e., forest edge density). Particularly under both high edge density and large ITs extents, cardiovascular disease incidence increases with the extent of forest outside ITs (Supplementary Table 3, Fig. 6c). This suggests that forest areas and ITs could potentially only mitigate cardiovascular incidence where edge density is low. Smooth terms regarding year and geographical coordinates further affected disease incidence in all instances (Supplementary Table 4).

For overall zoonotic/vector-borne diseases, malaria and cutaneous leishmaniasis incidence, the best model consistently included the interactive effects of the extent of forest outside ITs (and the orthogonal polynomial) and edge density in the case of zoonotic/vector-borne and cutaneous leishmaniasis, or patch density in the case of malaria, in addition to the additive effect of the extent of ITs (and the orthogonal polynomial). Figure 5 displays the relative importance and direction of predictors as estimated by the best-fitting models, as detailed in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. ITs (β [IT2] = -4.909) and the amount of forest outside ITs (β [forest outside IT] = -1.590) presented nonlinear effects on the overall incidence of zoonotic/vector-borne diseases. In addition, the amount of forest areas outside ITs varied according to the density of forest edges: when edge density is low, forest areas outside ITs are associated with positive effects (β [forest outside IT*edge density] = −14.623; β [forest outside IT2*edge density] = −19.72), increasing the incidence of zoonotic/vector borne diseases. However, when forest edge density increases, both forest areas (inside and outside ITs) present non linear effects, mitigating potential increases due to edge effects on zoonotic/vector-borne incidences if covering more than 40% of the municipality (Supplementary Table 3, Fig. 7a).

Panels represent predicted incidences of (a) overall zoonotic/vector-borne diseases, b malaria and (c) cutaneous leishmaniasis. The lines indicate predictions across varying levels of edge density in (a) and (b) and patch density in c malaria. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. Columns display levels of Indigenous Territories coverage (low: 15%, medium: 45%, high: 75%). Lines are patterned according to patch or edge density: low (olive green, solid), medium (brownish yellow, dashed), and high (light mustard, dotted).

The same trend was observed when considering malaria incidence separately, with a more noticeable increase in disease incidence being associated with augments in forest cover outside IT when both IT coverage and patch density are low (β [forest outside IT*patch density] = −24.811; β [forest outside IT2*patch density] = −24.614). Intermediate amounts of ITs could mitigate fragmentation effects if immersed in contexts of high forest cover outside ITs (Supplementary Table 3, Fig. 7b). Cutaneous leishmaniasis incidence peaks at high extents of forest cover outside ITs when both ITs extent is low and edge density is high (Fig. 7b). At the same time, for this disease, increasing the extent of ITs could mitigate those effects, decreasing disease incidence (β [IT] = 24.13). For the rare zoonotic/vector diseases, the occurrence of visceral leishmaniasis was best explained by the interactive effects of the extent of ITs and forest outside ITs, with or without the additive effect of edge density (Supplementary Table 3, Table 2, Fig. 5). Yet, the best ranked models for either Chagas disease or rickettsia retained the extent of cover cover and fragmentation (Supplementary Table 3, Table 2, Fig. 5). For all those rare diseases, the effect was negative, with increases in forest area, regardless if managed or not by indigenous people, being associated with decreases in disease occurrence. As before, the smooth terms regarding year and geographical coordinates further affected disease incidence in all instances (Supplementary Table 4).

The extent of legally recognized and unrecognized ITs differently affected disease incidence (Fig. 8). When legally recognized, ITs non-linearly affected disease incidence (β [recognized IT2] = −2.740), which was particularly noticeable when considering fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne diseases separately (Supplementary Table 5). In both instances, when municipalities have low to mid-coverages of legally recognized ITs, these have a positive association with disease incidence, whereas higher recognized ITs coverages have a negative effect (Fig. 8b, c). In contrast, the extent of unrecognized ITs had a positive association with both overall (β [unrecognized IT] = 5.062) and fire-related diseases incidence (β [unrecognized IT2] = −1.317; Fig. 8a, b), whereas the incidence of zoonotic/vector-borne diseases remained unaffected by the extent of unrecognized ITs (Fig. 8c). The smooth terms regarding year and geographical coordinates further affected disease incidence in all instances (Supplementary Table 6).

Predicted impacts of legal status of Indigenous Territories (ITs) on the incidence of (a) overall diseases, b fire-related diseases, and, c zoonotic/vector-borne diseases across municipalities in the Amazon biome. The model estimates the effect of recognized ITs (green lines) and unrecognized ITs (brown lines); shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. The coefficients (β – β1 and β2, in cases nonlinear relationship fitted better, see methods) and their standard errors (SE) are annotated for each line.

Discussion

Indigenous Territories have been fundamental to safeguard forests, biodiversity and overall ecological balance in the tropics9, but their effects on human health have been little investigated. Here, we expanded on previous work37 to understand the influence of ITs in safeguarding human health throughout the Amazon biome, where ITs are largely forest covered. Our results indicated that the association of the extent of ITs in mitigating fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne disease incidences is complex, non-linear, and highly dependent on the landscape context. In fact, ITs can only potentially mitigate PM2.5 impacts on fire-related diseases if inserted in municipalities with high forest cover contexts (>45%). For cardiovascular diseases specifically, this effect can only happen in municipalities with a low edge density, suggesting that fragmentation effects can be highly detrimental to human health. For zoonotic/vector-borne incidences, ITs could also decrease risks only if covering more than 40% of the municipality. Moreover, the legal status of ITs seems to play a critical role in the potential of ITs to minimize disease incidence, with unrecognized ITs boosting especially fire-related disease incidence.

Fire-related diseases showed a positive and significant association with the amount of PM2.5 accumulated in the environment, particularly for respiratory conditions, corroborating other studies36,37,57,58. In the Brazilian Amazon, for example, forest fires caused a 38% increase in respiratory and 27% in circulatory hospital admissions between 2008–201859, and preventing these fires could have averted 16,800 premature deaths in South America60. In fact, pollution was responsible for 9 million premature deaths in 2015 globally, being the largest environmental risk for disease57. Forest areas and particularly ITs, can play a key role in air pollution mitigation, removing PM2.5 from the environment37 through the dry deposition process61. Therefore, protecting more forest areas under Indigenous people’s management could significantly reduce atmospheric pollutants and improve human health outcomes.

However, the relationship between ITs extent, forest cover outside ITs, and fragmentation on fire-related disease incidence is nonlinear and complex, which indicates that the protection of ITs could mitigate the incidence of those diseases only in some contexts. This nonlinear effect indicates that there is a positive and unexpected association between the extent of the ITs on the incidence of fire-related diseases, contrasting results previously found for the Brazilian Amazon37. When considering the entire Amazon biome, the extent of the ITs is only associated with a decrease in fire-related diseases when the forest outside the ITs is high. This may reflect the generally lower amount of forest cover present in the municipalities when comparing the entire biome to the Brazilian Amazon, which means that large continuous forest areas seem necessary for the provisioning of this ecosystem service. Moreover, in municipalities with only small IT coverage, these areas are often embedded within highly degraded and fragmented landscapes, where forest fires are more frequent and intense, and the remaining forest is insufficient to buffer PM2.5 emissions—thereby increasing the risks of fire-related diseases.

Furthermore, the relationship between forest areas and the absorption of pollutants is complex and is directly associated with the dispersion of the pollutant and the speed and direction of the wind. Thus, for the service to be provided, the ITs must be located within 500 km of the fire outbreaks, which is not always the case. Our residual analysis indicates that high levels of potentially transboundary PM2.5 are observed in Peru and Suriname, drifting from Brazil and Colombia. Further studies should evaluate these transboundary effects and whether the absorption capacity of the forest changes with different distances from the emission source, different wind speeds, and different biotic parameters of the forests. In addition, local experimental research is needed to evaluate whether factors like temperature, humidity, or wind affect this capacity, further providing baseline information to elucidate the mechanisms underlying disease incidence. It’s also worth noting that these diseases also have other risk factors, such as diets based on industrialized foods, nicotine use, lack of exercise and stress, just to name a few, that were not considered in this study.

A similar result was found for zoonotic/vector-borne diseases. Indigenous Territories typically buffer against deforestation11,12, and thus help maintain biodiversity and overall ecological stability9. These conditions confer these areas with the potential to minimize disease outbreaks62,63. Our findings, however, demonstrate that the effects of ITs on the incidence of zoonotic/vector-borne diseases are rather complex, further depending on the amount of forest outside ITs and the degree of forest fragmentation. In scenarios where forest areas outside ITs have a low fragmentation degree (i.e., lower edge density), we found a consistent positive association with disease incidence, which can be linked to increases in the availability of suitable habitats for hosts and vectors. This pattern was corroborated by other studies, especially those carried out on large spatial scales, with the amount of forest cover being an important predictor of zoonotic/vector-borne disease risk, such as malaria64,65, cutaneous leishmaniasis66,67 and visceral leishmaniasis68. However, other studies carried out on smaller spatial scales have found the opposite result, with forest loss being a strong predictor of malaria incidence (e.g.69,70). Moreover, in scenarios of higher forest cover outside ITs and lower IT extent, fragmentation via edge density seems to boost zoonotic disease incidence, which might be due to the increased human exposure to the pathogen agents53,54.

Our results also point to a nonlinear effect between zoonotic/vector-borne disease incidence and forest cover in contexts of intermediate to high levels of forest fragmentation. As forest cover increases above 40%, overall zoonotic/vector borne disease incidence decreases. As an exception, when the extent of ITs is high, any increment in the forest cover outside ITs can be associated with an increase in the disease incidence, regardless of the degree of fragmentation. The complexity of such relationships, either positive or negative, has been noted in other studies: areas with an intermediate amount of forest cover (~30–70%) and higher levels of forest fragmentation posing the highest risk of Plasmodium transmission to humans69,71. The incidence of cutaneous leishmaniasis also varied non-linearly with the extent of ITs, but not that of forest cover outside ITs. When the extent of ITs is low, forest cover outside ITs above 60% has the potential to increase this disease incidence. This agrees with recent findings across the Brazilian Amazonia reporting a higher incidence of cutaneous leishmaniasis when forest cover is high, particularly when higher densities of livestock exist72.

However, our results point to another layer of complexity in this relationship, indicating that ITs can mitigate fragmentation effects on disease incidences only if covering more than 40% of the municipality. Non-linear relationships have widely characterized biodiversity responses to forest loss and fragmentation73,74,75, but little is known about the specific impact of these non-linear dynamics on the risk of transmission of pathogens that cause zoonotic/vector-borne diseases, and the interactive effect between forest areas in different fragmentation contexts. Non-linearities between biodiversity and disease incidence were found before76, but so far, to our knowledge, no study has evaluated forest cover thresholds in the risk of zoonotic diseases77. Notwithstanding, the drivers of zoonotic/vector-borne disease incidence involve not only the response of vectors and hosts (hazard), landscape structure, remaining biodiversity loss, but also human exposure, behavior, and socio-economic factors. To handle the complexity associated with the different drivers of disease incidence, local studies are needed to disentangle the contribution of such different factors.

Furthermore, when distinguishing between the legal status of the ITs, legally recognized ITs had the previously discussed nonlinear association with disease incidence. In contrast, unrecognized ITs drove most of the positive impacts on the overall fire-related disease incidence, likely due to higher fire activity and deforestation rates where ITs lack legal recognition, as observed in the Brazilian Amazon9. Our findings reinforce the importance of legally recognizing ITs, not only to curb deforestation but also to improve local human health. Finally, the balance between autochthonous traditional ways of life and the sustainability of natural resources is fragile and may be weakened by socio-economic and environmental changes6, potentially leading to animal population collapses7, and threatening ecological dynamics essential for preserving disease emergence.

Limitations

It is worth acknowledging that this study has several limitations that must be taken into account. First, there are limitations due to variations in health data collection across countries, as evidenced by the importance of the spatial and temporal smooth terms of the models. Indeed, not all diseases are mandatorily reported (such as the fire-related diseases), and the monitoring scope varies by country. To account for this, a weighted average of disease incidence was used. Differences in temporal and spatial data scales, as well as underreporting of mild cases, may also lead to underestimated figures. Additionally, differences in the availability and resolution of socioeconomic data across countries led us to adopt the Human Development Index (HDI) at the country-level, which may not capture intra-municipal disparities. Specific analyses for each disease and each country can help to limit these biases; however, this was not the intent of this paper. Despite these limitations, the estimates provide a valuable overview of the general patterns and relationships that exist between landscape structure, ITs conservation and disease outcomes.

Second, PM2.5 measurements in tropical regions, including in the Amazon, can be affected by cloud cover. This study tried to overcome this by only including clear-sky aerosol optical depth (AOD) data, reflecting mostly dry-season months. In addition, AOD data do not distinguish between particle sizes or sources, which challenges our assumption that the Amazon Biome operates as a relatively closed system. Dust particles coming from other regions of the world, especially from the Saharan dust events78,79, can be a bias in the PM2.5 estimates and affect human health, especially in the Atlantic side of the Amazon. Finally, PM2.5 concentrations were calibrated using NASA’s SEDAC V4.03 dataset, based on satellite data and a chemical transport model, though the model is largely calibrated with data from outside the Amazon. Therefore, to improve PM2.5 accuracy in situ PM2.5. monitoring would be needed in the region80.

Third, the definition of “Indigenous Territories” varies across Amazon nations, with many territories unmapped due to political issues2. This study conservatively used official databases, validated by local collaborators, following the Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information (RAISG). This includes both recognized and traditionally claimed Indigenous lands. Differences in land management practices, such as the lack of Indigenous recognition in French Guiana and ongoing land rights discussions in Suriname, highlight the complexity of the issue. In addition, we did not account for differences in Indigenous groups and sustainable practices, which may occur due to different cultures and traditions and that could result in different outcomes for human health. This aspect could be considered in future studies. Despite these challenges, Indigenous stewardship remains vital for biodiversity and conservation efforts. Moreover, we did not consider any other type of protected areas apart from the ITs. As forests outside ITs might be considered both protected and unprotected forests, this might be a further source of noise in our analysis.

Finally, this study only considers the most common zoonotic and vector-borne diseases and does not account for other important and emerging viruses, such as the arenaviruses (mammarenaviruses), whose spillover risk can also be driven by land use change and other ecological aspects. Therefore, more studies considering other viruses and pathogens are needed to provide a clearer picture of how indigenous lands can protect human health.

Conclusions

Our study underscores the complex relationships between the extent of ITs in minimizing the incidence of both fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne diseases, which is dependent on the landscape context in which the IT is inserted, i.e. the amount of forest outside ITs and and the degree of forest fragmentation in minimizing the incidence of both fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne diseases. We further emphasize the importance of legally recognized ITs, particularly when those cover a considerable part of the municipality, to minimize fire-related diseases. The different responses of fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne disease incidence to the extent of ITs, landscape composition and ITs legal status suggest that different mechanisms underlie the risk of those diseases. Despite this study representing a first step in uncovering relationships between fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne diseases and ITs, local-scale research is imperative to understand the underlying mechanisms. Our findings highlight the need for policies supporting indigenous land rights, which are not only essential for protecting these populations but can also generate positive outcomes for human health.

Methods

Study area

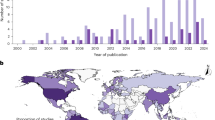

We focus our analysis on the Pan-Amazonian region, which spans the Amazon biome and includes eight nations: Brazil (64%), Peru (10%), Colombia (6%), Bolivia (6%), Venezuela (6%), Guyana (3%), Suriname (2%), and Ecuador (2%), as well as one French/European overseas territory, French Guiana (1%). This biogeographical limit of approximately 7.0 million km² considers the functional and biotic relatedness of ecosystems classified as Amazonian biome (Fig. 9a). If a municipality was only partially within the Amazon biome, it was considered as part of our study area.

a Location of the Amazon biome (in light green), and the indigenous territories. ITs can be recognized (dark green) by local governments, or unrecognized (brown) if classified as ‘recognition requested’ or ‘without recognition request. b Temporal distribution of disease data collected in the Amazonian countries—categorized in zoonotic (containing both zoonotic/vector-borne diseases), and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Each horizontal line represents the span of years data was collected for each country, with dots indicating specific years of recorded data.

Fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne diseases data

Data collected for this study encompass the number of human cases of 21 fire-related (cardiovascular and respiratory) and six zoonotic/vector-borne diseases (i.e. malaria, cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, hantavirus and spotted fever), in a municipality or similar scale for most of the countries that compose the Amazon biome (Supplementary Table 7 lists each disease and the corresponding International Classification ICD-10). Those six zoonotic and vector-borne diseases were chosen to represent some of the most common diseases in the region, because they cover transmission modes with different organisms involved, and because they have evidence to be affected by environmental variables such as land use change. The data for each country was collected by local collaborators retrieved from official reports to national health systems, or through direct contact with local health systems. Therefore, not all the data collected for this study is available in online government repositories. All six zoonotic and vector-borne diseases chosen are diagnosed with valid diagnostic tests and only cases confirmed by laboratory tests were included in the analysis.

Across the Amazon, Guyana was the only country for which no disease data were available, accounting for 3% of the Amazon biome. In total, temporal disease data were available for 1,733 municipalities across eight countries, representing 74.3% of the entire Amazon. Data from Suriname was aggregated to the country level due to the methodology for disease data collection, thereby not following administrative divisions. Moreover, each country has its own reporting system and, as not all the diseases considered for this study were compulsorily notifiable, the accuracy of the disease data collected varies for each country. On average, data was collected between 2000–2019, with some countries having data from 1995–2017 and others from 2015–2020 (Fig. 9b). All data collected between 2020 and 2022 has been discarded to avoid any confounding factors due to the COVID-19 pandemic (including low reporting of zoonotic/vector-borne diseases due to low laboratory capacity in some countries). Supplementary data 1 presents a summary of the spatial and temporal scale, and the access link, if available, for each disease collected for each country. In cases where fire-related diseases were zero for that country and year, we assumed it was not monitored and substituted zeros with NAs to avoid underestimation, as fire-related diseases are common and normally have a high incidence.

For each fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne disease, we considered the disease incidence as calculated by dividing the total number of cases in a specific year by the total population of each municipality for that year, then multiplying by 100,000. Population data were obtained from the WorldPop project (www.worldpop.org), which provides high-resolution, open-access mapping and data on population distributions and demographics globally. As the data is only available every five years (i.e., 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020) we extrapolated the population for each municipality and each year by using the formula:

Indigenous Territories (ITs) and recognition status

We considered the entire area covered by Indigenous Territories per municipality. Indigenous Territories’ boundaries of the Amazon biome were obtained from the Amazonian Network of Georeferenced Socio-environmental Information (Red Amazónica de Información Socioambiental Georreferenciada—RAISG, https://www.raisg.org/) for 2023. The RAISG database provides a comprehensive and regularly updated compilation of spatial information on ITs and Protected Natural Areas (PNAs) across the Amazon. The database integrates data from various governmental and non-governmental sources and provides detailed information on individual ITs, including their names, recognition status, governance structures, and management goals. For this study, we utilized the 2023 RAISG database release to capture the most current data on ITs. Indigenous territories were classified as ‘recognized’ status by local governments, as indicated in the database only if they were designated as ‘officially recognized’ in the RAISG database. Other territories, classified as ‘recognition requested’ or ‘without recognition request’, were considered as ‘unrecognized’ Indigenous lands, without official recognition. This classification approach aligns with the criteria provided by RAISG, which distinguishes the level of formal recognition granted by local governments. For that reason, those two countries did not have ITs being included in the analysis.

To enhance data accuracy, whenever available we cross-referenced national official mappings of Indigenous territories with the RAISG data where available, helping to address any discrepancies and ensuring reliability. It is important to note that Indigenous territories from Suriname are absent, as the Surinamese government does not officially recognize Indigenous or tribal communities, and there is no legal framework governing such territories or related rights. Additionally, in French Guiana, as a French overseas territory, Indigenous status is not formally recognized, and Indigenous lands designated by local decrees have a more limited legal standing and may not be recognized internationally.

Forest fires and PM2.5 estimation

A yearly time series of total fire events for the period 2001 - 2019 was developed from daily MODIS Terra thermal anomalies product (MOD14A1 V6.1) at 1 km spatial resolution. Daily thermal anomalies were masked to include only fires detected with high confidence (Bits 0-3 = 9). The masked daily images were then summed to produce yearly images where the pixel value corresponds to the number of days a pixel was burning during that year (Supplementary Fig. 1).

To map the yearly spatial distribution of PM2.5, the MAIAC Land Aerosol Optical Depth (MCD19A2 V6.1) was combined with the PM2.5 from NASA’s Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC V4.0380) from 2001 to 2019, at a spatial resolution of 1 km (Supplementary Fig. 2). Total fire events in the Amazon had a better temporal relationship with MAIAC AOD than with SEDAC PM2.5 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Although MAIAC AOD is a good proxy for PM2.5 ground concentrations81, it needs to be calibrated into PM2.5 concentrations to be suitable for health impact analysis.

The AOD-calibrated PM2.5 dataset was calculated by extracting daily MODIS MAIAC Aerosol optical depth Blue band (0.47 μm). Each daily image was masked to keep only pixels that were clear from clouds and deemed the best quality (bits 0 to 2 = 1, and bits 8 to 11 = 0). The mean yearly AOD was calculated at each pixel considering only those best quality values. MAIAC AOD values were then calibrated into PM2.5 using NASA’s SEDAC PM2.5 as a reference through a pixel-level temporal OLS regression. For each 1 km pixel, a temporal linear regression was extracted between AOD (dependent) and PM2.5 (independent). The results of this are, for each pixel, a slope and intercept coefficients that were then applied to the complete MAIAC AOD time series 2001- 2019 to transform the AOD values into PM2.5. The final result is a time series 2001- 2019 of calibrated AOD-PM2.5 (μg m-3). The calibrated AOD-PM2.5 product showed a better correlation with fires than AOD or SEDAC alone and had a high correlation with SEDAC PM2.5. Finally, the average PM2.5 in each municipality was calculated. All analyses were done in South America Albers equal-area conic projection (EPSG:4618). The calibrated AOD-PM2.5 product showed a high correlation with the SEDAC PM2.5 for the years of overlap (Pearson r > 0.95).

Since the pollution generated by forest fires in this region could be displaced by the wind over 500 kilometers37, we calculated the sum of PM2.5 within this radius by using a moving window approach, an assumed that this considers the transboundary effect of pollutant that can affect human health (Supplementary Fig. 4). Analysis was performed on Google Earth Engine and TerrSet. The total area burned in the Amazon biome was calculated considering only the presence or absence of fire per pixel between 2001 and 2019. This way, even if a pixel caught fire every year during this period, it was only counted once when calculating the area burned. As each pixel is 1 km2, the sum of all pixels that caught fire at least once gives us the total area burned between 2001 and 2019. For the accumulated burned area, the frequency of forest fires per pixel was also considered.

Landscape metrics extraction and socio-economic factors

Forest cover and fragmentation metrics were extracted from MapBiomas Amazon mapping Collection 4 (available at http://mapbiomas.org/), with 30-meters spatial resolution and available from 1985 to 2022. Metrics extraction was carried out for years coinciding with both disease health and pollution data (2000 - 2019). MapBiomas mapping includes 25 land cover classifications: forest, savanna, mangrove, flooded forest, grassland, rocky outcrop, pasture, agriculture, silviculture, palm oil, mining, other non-vegetated areas, and river, lakes, and oceans. A detailed methodology of the mapping can be found at https://amazonia.mapbiomas.org/vision-general-de-la-metodologia/. From these land cover classifications, we retained forest and savanna which together comprised ‘forest’ cover measured at the municipality level (or country, in the case of Suriname) (i.e., overall forest cover). Forest cover outside ITs was obtained by subtracting the IT extent from the overall forest cover. IT extent was additionally considered by distinguishing between legally recognized and unrecognized extent within the municipality. Fragmentation metrics, included edge density (the total length of forest edge in a municipality), patch density (number of forest patches divided by the total area), and the aggregation between those forest remnants (equals the number of adjacencies involving forest and divided by the maximum possible number of adjacencies in each municipality), and were extracted at the municipality level (i.e., considering outside and inside ITs). All landscape metrics were extracted using R, ArcGis 10.8.1, and Fragstats 4.2.

For each country, we also collected one socioeconomic indicator to consider for such potential effects. The Human Development Index (HDI), which includes life expectancy and Gross National Income (GNI) per capita, adjusted for subnational variations. We used national-level HDI data sourced from the Global Data Lab (https://globaldatalab.org/), as it was the most comprehensive and consistently available source across all countries and years in our study period (2000–2019).

Statistical analysis

To assess the effects of fire pollutants (PM2.5) on the overall number of fire-related disease cases, as well as on those of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases separately, we fitted Generalized Additive Models (GAMs, ‘mgcv’ R package82) with a negative binomial error distribution and geographic coordinates and year as smooth terms to account for underlying spatial trends and temporal variations. GAMs were chosen for their flexibility in modeling complex relationships while addressing potential temporal and spatial autocorrelation. Additionally, as human vulnerability to fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne diseases is associated with socioeconomic conditions (e.g.83), we included the Human Development Index (HDI) as an offset in the models, allowing us to account for any potential effect regarding socioeconomic differences across municipalities.

For cardiovascular diseases, which are normally chronic and can be more affected by the cumulative exposure to pollutants, we also tested models with cumulative effects of 2 and 5 years of PM2.5, selecting those with the lowest Akaike Information Criteria (AIC). Given the acute nature of most respiratory diseases in our dataset, time lags were not modeled for these conditions. Model diagnostics were performed using the ‘DHARMa’ R package84, model predictions were extracted and visualized using the ‘ggeffects’ R package85, and the performance of the models was evaluated using the adjusted R² from the model summaries.

To evaluate the interrelated effects of the extent of ITs, forest outside ITs, overall forest cover, as well as that of forest fragmentation metrics (i.e., edge density, patch density and an aggregation index) on the incidence of fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne diseases, we also applied GAMs. The incidence of fire-related diseases was further disaggregated into respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, and that of zoonotic/vector-borne diseases in malaria and cutaneous leishmaniasis. Those disease incidences were log10-transformed and the corresponding GAMs fitted with a Gaussian distribution. Cases of Chagas disease, rickettsia and visceral leishmaniasis comprised rare events, and the high number of zeros precluded us from fitting a suitable data distribution to the model. With that, we restricted the dataset to municipalities with at least one case of the disease and randomly selected the same number of municipalities with no cases. The occurrence of these diseases was modeled using GAMs fitted with a binomial distribution. Hantavirus was a particularly rare event, with only 228 cases being reported in 100 out of 13,125 municipalities, and thus not analyzed in a disease-specific model.

Using the same R package, GAMs again considered HDI as an offset, year and geographic coordinates as smooth parameters. The effect of forest cover on biological processes is often non-linear and to account for this, prior to constructing the set of alternative models, we considered the orthogonal polynomials of the ITs extent, forest outside ITs and overall forest cover in the municipality. To do so, we applied two GAMs relating disease incidence (or occurrence) considering either ITs extent, forest outside ITs or overall forest cover, including and excluding the corresponding orthogonal polynomial. For each of these explanatory variables, the orthogonal polynomial was retained in subsequent models whenever that allowed to improve model fit (i.e., \(\triangle\)AIC > 2, being \(\triangle\)AIC = AICi − AICmin in which i = ith model). We then constructed a set of 27 alternative models aiming to cover all possible combinations of non-correlated variables that have been hypothesized to affect each response variable. The set of alternative models included models with (1) only either ITs extent, forest outside ITs, overall forest cover, edge or patch density, (2) the additive effects between the extent of ITs, forest outside ITs and edge and patch density, (3) the interactive between these variables (considering two variables to interact at a time), and (4) both additive and interactive effects (the set the alternative models is described in Table 6). For diseases for which the orthogonal polynomial has been retained for both the extent of ITs and forest outside ITs, in alternative models considering both variables, the orthogonal polynomial was retained in only one variable at a time. The area covered by ITs in the Amazon biome is known to be largely forest covered8. To avoid redundancy in accounting for the area covered by forest in the municipality in multiple variables, we did not include overall forest cover in the same model as ITs extent or forest cover outside indigenous territories. Edge and patch density were highly correlated and also not included in the same models. The aggregation index was highly correlated with the extent of ITs and thus not included in any alternative model. Additionally, as the mechanisms involved in disease regulation services are largely restricted to native vegetation areas, we excluded municipalities where ITs were not covered by forests or savannas. We then visualized the model predictions based on the best model (i.e., lowest AIC), using the ‘ggeffects’ R package85, and assessed the model residuals using the ‘DHARMa’ R package84.

To unveil the importance of the recognition status of ITs on the overall fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne disease incidence, as well as on the incidence of fire-related and zoonotic/vector-borne diseases separately, we applied GAMs considering the extent of recognized and unrecognized ITs at the municipality level as explanatory variables. As before, we applied GAMs relating disease incidence considering either the extent of recognized ITs or unrecognized ITs, including and excluding the corresponding orthogonal polynomial. For each of these explanatory variables, the orthogonal polynomial was retained in subsequent models whenever it allowed to improve model fit (i.e., \(\triangle\)AIC > 2). Disease incidences were log10-transformed and GAMs fitted with a Gaussian distribution. As before, year and geographic coordinates were included as smooth parameters; GAMs were performed using the ‘mgcv’ R package82; model predictions plotted using the ‘ggeffects’ R package85 and the model residuals assessed using the ‘DHARMa’ package84. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.1.2 (R Core Team, 2021).

Data availability

To guarantee full reproducibility of our research, all the data and analytical codes—from data management, to analyses, model validation and used to generate the figures and the Supplementary Materials in this paper—are available at Zenodo86 DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.16124886.

References

World Bank Group. Indigenous Peoples (2025). https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/indigenouspeoples.

Garnett, S. T. et al. A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nat. Sustain 1, 369–374 (2018).

Fernández-Llamazares, Á & Virtanen, P. K. Game masters and Amazonian Indigenous views on sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain 43, 21–27 (2020).

Ellis, E. C. et al. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2023483118 (2021).

Pérez, C. J. & Smith, C. A. Indigenous knowledge systems and conservation of settled territories in the Bolivian Amazon. Sustainability 11, 6099 (2019).

Iwamura, T., Lambin, E. F., Silvius, K. M., Luzar, J. B. & Fragoso, J. M. V. Socio–environmental sustainability of indigenous lands: simulating coupled human–natural systems in the Amazon. Front Ecol. Environ. 14, 77–83 (2016).

De Thoisy, B., Richard-Hansen, C. & Peres, C. A. in South American Primates: Comparative Perspectives in the Study of Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation (eds Garber, P. A., Estrada, A., Bicca-Marques, J. C., Heymann, E. W. & Strier, K. B.) 389–412 (Springer, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-78705-3.

Nepstad, D. et al. Inhibition of Amazon deforestation and fire by parks and indigenous lands. Conserv. Biol. 20, 65–73 (2006).

Baragwanath, K. & Bayi, E. Collective property rights reduce deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 20495–20502 (2020).

Robinson, B. E., Holland, M. B. & Naughton-Treves, L. Does secure land tenure save forests? A meta-analysis of the relationship between land tenure and tropical deforestation. Glob. Environ. Change 29, 281–293 (2014).

Bonilla-Mejía, L. & Higuera-Mendieta, I. Protected areas under weak institutions: evidence from Colombia. World Dev. 122, 585–596 (2019).

Porter-Bolland, L. et al. Community managed forests and forest protected areas: an assessment of their conservation effectiveness across the tropics. Ecol. Manag. 268, 6–17 (2012).

Jusys, T. Changing patterns in deforestation avoidance by different protection types in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS ONE 13, e0195900 (2018).

IPBES. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (IPBES, 2019).

WWF. Inside the Amazon (2024). https://wwf.panda.org/discover/knowledge_hub/where_we_work/amazon/about_the_amazon/?.

Raven, P. H., Gereau, R. E., Phillipson, P. B., Chatelain, C., Jenkins, C. N. & Ulloa Ulloa, C. The distribution of biodiversity richness in the tropics. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc6228 (2020).

Mittermeier, R. A. et al. Wilderness and biodiversity conservation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 100, 10309–10313 (2003).

Dirzo, R. & Raven, P. H. Global state of biodiversity and loss. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 28, 137–167 (2003).

Science Panel for the Amazon. Amazon Assessment Report 2021 (2021). https://www.theamazonwewant.org/amazon-assessment-report-2021/.

Barlow, J. et al. The future of hyperdiverse tropical ecosystems. Nature 559, 517–526 (2018).

Latrubesse, E. M. et al. Damming the rivers of the Amazon basin. Nature 546, 363–369 (2017).

Esquivel-Muelbert, A. et al. Compositional response of Amazon forests to climate change. Glob. Chang Biol. 25, 39–56 (2019).

Baker, J. C. A. & Spracklen, D. V. Climate benefits of intact Amazon forests and the biophysical consequences of disturbance. Front. Forests Glob. Chang. 2, 47 (2019).

Malhi, Y., Saatchi, S., Girardin, C. & Aragão, L. E. O. C. The Production, Storage, and Flow of Carbon in Amazonian Forests. Amazonia and Global Change 355–372 https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GM000733 (2013).

Saatchi, S. S., Hiughton, R. A., Dos Santos Alvalá, R. C., Soares, J. V. & Yu, Y. Distribution of aboveground live biomass in the Amazon basin. Glob. Chang Biol. 13, 816–837 (2007).

Lessmann, J. & Fajardo, J. Muñoz, J. & Bonaccorso, E. Large expansion of oil industry in the Ecuadorian Amazon: biodiversity vulnerability and conservation alternatives. Ecol. Evol. 6, 4997–5012 (2016).

Turubanova, S., Potapov, P. V., Tyukavina, A. & Hansen, M. C. Ongoing primary forest loss in Brazil, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Indonesia. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 074028 (2018).

Lapola, D. M. et al. The drivers and impacts of Amazon forest degradation. Science 379, eabp8622 (2023).

Finer, M. & Mamani, N. MAAP Synthesis: 2019 Amazon Deforestation Trends and Hotspots—MAAP (2020). https://www.maapprogram.org/synthesis-2019/.

Morton, D. C. et al. Agricultural intensification increases deforestation fire activity in Amazonia. Glob. Chang. Biol. 14, 2262–2275 (2008).

Aragão, L. E. O. C. et al. 21st Century drought-related fires counteract the decline of Amazon deforestation carbon emissions. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–12 (2018).

Barreto, J. R. et al. Assessing invertebrate herbivory in human-modified tropical forest canopies. Ecol. Evol. 11, 4012–4022 (2021).

Johnston, F. H. et al. Estimated global mortality attributable to smoke from landscape fires. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 695–701 (2012).

Naeher, L. P. et al. Woodsmoke health effects: a review. Inhal. Toxicol. 19, 67–106 (2007).

Mishra, A. K., Lehahn, Y., Rudich, Y. & Koren, I. Co-variability of smoke and fire in the Amazon basin. Atmos. Environ. 109, 97–104 (2015).

Reddington, C. L. et al. Air quality and human health improvements from reductions in deforestation-related fire in Brazil. Nat. Geosci. 8, 768–771 (2015).

Prist, P. R. et al. Protecting Brazilian Amazon Indigenous territories reduces atmospheric particulates and avoids associated health impacts and costs. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 146 (2023).

van der Werf, G. R. et al. Global fire emissions estimates during 1997–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 697–720 (2017).

Apte, J. S., Marshall, J. D., Cohen, A. J. & Brauer, M. Addressing global mortality from ambient PM 2.5. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 8057–8066 (2015).

Machado-Silva, F. et al. Drought and fires influence the respiratory diseases hospitalizations in the Amazon. Ecol. Indic. 109, 105817 (2020).

Prüss-Ustün, A. et al. Diseases due to unhealthy environments: an updated estimate of the global burden of disease attributable to environmental determinants of health. J. Public Health (Bangk.) 39, 464–475 (2017).

Prüss-Üstün, A., Bonjour, S. & Corvalán, C. The impact of the environment on health by country: a meta-synthesis. Environ. Health 7, 1–10 (2008).

Loh, E. H. et al. Targeting transmission pathways for emerging zoonotic disease surveillance and control. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 15, 432–437 (2015).

Allen, T. et al. Global hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases. Nat. Commun. 8, 1124 (2017).

Jones, K. E. et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990–993 (2008).

Jones, B. A. et al. Zoonosis emergence linked to agricultural intensification and environmental change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 8399–8404 (2013).

Gottdenker, N. L., Streicker, D. G., Faust, C. L. & Carroll, C. R. Anthropogenic land use change and infectious diseases: a review of the evidence. Ecohealth 11, 619–632 (2014).

Fahrig, L. Rethinking patch size and isolation effects: the habitat amount hypothesis. J. Biogeogr. 40, 1649–1663 (2013).

Kocher, A. et al. Biodiversity and vector-borne diseases: Host dilution and vector amplification occur simultaneously for Amazonian leishmaniases. Mol. Ecol. 32, 1817–1831 (2023).

Guégan, J.-F., Ayouba, A., Cappelle, J. & de Thoisy, B. Forests and emerging infectious diseases: unleashing the beast within. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 083007 (2020).

Ribeiro Prist, P. et al. Roads and forest edges facilitate yellow fever virus dispersion. J. Appl. Ecol. 59, 4–17 (2022).

Gómez-Hernández, E. A., Moreno-Gómez, F. N., Bravo-Gaete, M. & Córdova-Lepe, F. Competition and edge effect in wildlife zoonotic agents. Ecol. Model. 496, 110838 (2024).

Faust, C. L. et al. Pathogen spillover during land conversion. Ecol. Lett. 21, 471–483 (2018).

Borremans, B., Faust, C., Manlove, K. R., Sokolow, S. H. & Lloyd-Smith, J. O. Cross-species pathogen spillover across ecosystem boundaries: mechanisms and theory. Philos. Trans. Roy. Soc. B 374 (2019).

Fernández-Llamazares, Á et al. The importance of Indigenous Territories for conserving bat diversity across the Amazon biome. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv 19, 10–20 (2021).

Bauch, S. C., Birkenbach, A. M., Pattanayak, S. K. & Sills, E. O. Public health impacts of ecosystem change in the Brazilian Amazon. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7414–7419 (2015).

Fuller, R. et al. Pollution and health: a progress update. Lancet Planet Health 6, e535–e547 (2022).

Butt, E. W. et al. Large air quality and human health impacts due to Amazon forest and vegetation fires. Environ. Res. Commun. 2, 095001 (2020).

Requia, W. J., Amini, H., Mukherjee, R., Gold, D. R. & Schwartz, J. D. Health impacts of wildfire-related air pollution in Brazil: a nationwide study of more than 2 million hospital admissions between 2008 and 2018. Nat. Commun. 12, 6555 (2021).

Butt, E. W., Conibear, L., Knote, C. & Spracklen, D. V. Large air quality and public health impacts due to Amazonian deforestation fires in 2019. Geohealth 5, e2021GH000429 (2021).

Beckett, K. P., Freer-Smith, P. H. & Taylor, G. Particulate pollution capture by urban trees: effect of species and windspeed. Glob. Chang Biol. 6, 995–1003 (2000).

Keesing, F., Holt, R. D. & Ostfeld, R. S. Effects of species diversity on disease risk. Ecol. Lett. 9, 485–498 (2006).

Ostfeld, R. S. & Keesing, F. Effects of host diversity on infectious disease. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 43, 157–182 (2012).

Valle, D. & Clark, J. Conservation efforts may increase malaria burden in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS ONE 8, e57519 (2013).

Bailey, A. & Prist, P. R. Landscape and socioeconomic factors determine malaria incidence in Tropical Forest countries. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health 21, 576 (2024).

Quintana, M. G., Fernández, M. S. & Salomón, O. D. Distribution and abundance of phlebotominae, vectors of Leishmaniasis, in Argentina: spatial and temporal analysis at different scales. J. Trop. Med 2012, 1–16 (2012).

Valero, N. N. H., Prist, P. & Uriarte, M. Environmental and socioeconomic risk factors for visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis in São Paulo, Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 797, 148960 (2021).

Almeida, A. S. & Werneck, G. L. Prediction of high-risk areas for visceral leishmaniasis using socioeconomic indicators and remote sensing data. Int J. Health Geogr. 13, 13 (2014).

MacDonald, A. J. & Mordecai, E. A. Amazon deforestation drives malaria transmission, and malaria burden reduces forest clearing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 22212–22218 (2019).

Santos, A. S. & Almeida, A. N. The impact of deforestation on malaria infections in the Brazilian Amazon. Ecol. Econ. 154, 247–256 (2018).

Laporta, G. Z. et al. Malaria transmission in landscapes with varying deforestation levels and timelines in the Amazon: a longitudinal spatiotemporal study. Sci. Rep. 11, 6477 (2021).

Portella, T. P., Sudbrack, V., Coutinho, R. M., Prado, P. I. & Kraenkel, R. A. Bayesian spatio-temporal modeling to assess the effect of land-use changes on the incidence of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in the Brazilian Amazon. Sci. Total Environ. 953, 176064 (2024).

Pardini, R., de Bueno, A. A., Gardner, T. A., Prado, P. I. & Metzger, J. P. Beyond the fragmentation threshold hypothesis: Regime shifts in biodiversity across fragmented landscapes. PLoS ONE 5, e13666 (2010).

Haddad, N. M. et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500052 (2015).

Dobson, A. P. et al. Ecology and economics for pandemic prevention. Science 369, 379–381 (2020).

Halliday, F. W. & Rohr, J. R. Measuring the shape of the biodiversity-disease relationship across systems reveals new findings and key gaps. Nat. Commun. 10, 5032 (2019).

Mancini, M. C. S. et al. Landscape ecology meets disease ecology in the Tropical America: patterns, trends, and future directions. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep.9, 31–62 (2024).

Prospero, J. M., Collard, F. X., Molinié, J. & Jeannot, A. Characterizing the annual cycle of African dust transport to the Caribbean Basin and South America and its impact on the environment and air quality. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 28, 757–773 (2014).

Nacher, M. et al. Desert dust episodes during pregnancy are associated with increased preterm delivery in French Guiana. Front. Public Health 12, 1252040 (2024).

Hammer, M. S. et al. Global estimates and long-term trends of fine particulate matter concentrations (1998-2018). Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 7879–7890 (2020).

Chudnovsky, A. et al. High resolution aerosol data from MODIS satellite for urban air quality studies. Cent. Eur. J. Geosci. 6, 17–26 (2014).

Wood, S. Package ‘mgcv’ – Mixed GAM Computation Vehicle with Automatic Smoothness Estimation. CRAN (2025) https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315370279.

Alvar, J., Yactayo, S. & Bern, C. Leishmaniasis and poverty. Trends Parasitol. 22, 552–557 (2006).

Hartig, F. DHARMa: Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level/Mixed) Regression Models. R package version 0.2.4 (2019).

Lüdecke, D. ggeffects: tidy data frames of marginal effects from regression models. J. Open Source Softw. 3, 772 (2018).

Barreto, J. Barretoju/it_conservation_health_amazon: Release to Zenodo. v01, Zenodo (2025), https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16124886.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Paulo Inácio de K. L. de Prado for the support and availability in the initial development of this project. We are grateful to PIKLP, Melina de Souza Leite and Fernanda Alves-Martins for their helpful discussions on the analytical approach of this study. We also thank the FORD Foundation for the funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Author notes

Independent Consultant: Nerida H. Valero, Catalina Zuluaga Rodríguez.

Contributions

P.R.P. secured funding and was responsible for designing the research. J.B. was responsible for Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Data Collection, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing, Review & Editing. J.B., F.P., P.R.P., F.S. were responsible for data analysis. F.S., F.C.R., B.d.T., A.G.C., M.E.G., V.M.D., N.H.V., C.Z.R., and P.R.P. contributed to data collection. J.R.B., A.F.P., F.S., F.C.R., B.d.T., A.G.C., M.E.G., V.M.D., F.E.R.G., A.R.S.R., N.H.V., C.Z.R., and P.R.P. contributed to writing and revising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. P.R.P. is an Editorial Board Member for Communications Earth & Environment, but was not involved in the editorial review of, nor the decision to publish this article.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barreto, J.R., Palmeirim, A.F., Sangermano, F. et al. Indigenous Territories can safeguard human health depending on the landscape structure and legal status. Commun Earth Environ 6, 719 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02620-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02620-7