Abstract

Around 80% of the world’s hard-rock lithium supply comes from pegmatites formed in the Archean Eon, yet our understanding of how Lithium-pegmatites form assumes magma source compositions not relevant to those Archean cratons hosting most of the giant Lithium-pegmatites. These models emphasize extraction of residual pegmatitic liquids from granitic magmas formed through melting sedimentary sequences. However, there is no evidence that such sequences provided the source to Lithium-rich granites and related giant Lithium-pegmatites in the Archean cratons of Western Australia. Economically important Lithium-pegmatites in these terrains form near faulted contacts between regional granites and basalt-dominated greenstone belts. Where spatially associated granites are Lithium-rich, they also contain unusually radiogenic Neodymium, resembling earlier, but spatially associated hydrated high-Magnesium diorites of mantle origin (sanukitoid). Intrusion of sanukitoids along crustal-scale structures prior to granitic magmatism induced Lithium-rich biotite alteration of the felsic basement beneath greenstone belts. Analogous to melting metasomatized lithospheric mantle to produce sanukitoids, melting of sanukitoid-infused basement beneath greenstone roots produced Lithium-rich granites and ultimately Lithium-pegmatite. Melting buried metasediments might produce Lithium-pegmatites, but most of the world’s giant Lithium-pegmatites formed along major crustal boundaries in response to the transfer of hydrous mantle-derived magma from metasomatized deep lithospheric domains in the Archean.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lithium is critical for the global transition to new, clean, energy sources, with a predicted future demand that greatly exceeds current production. Most current production is from Li-pegmatites. These deposits have smaller environmental footprints and higher grades1,2,3 than other Li resources. Currently, Li-pegmatites in Archean terrains of Western Australia account for around 35% of world Li production, more than 1.5 times the cumulative Li-production from hard-rock and brine deposits of the next largest producer - Chile4.

Li-pegmatites typically contain high concentrations of both Cs and Ta, forming a petrogenetic family of granite pegmatites referred to as LCT pegmatites5. This distinguishes them from the NYF (Nb–Y–F) pegmatite family, and other more common pegmatite varieties that lack rare metals.

One of the challenges in finding the Li resources required to meet future demand is in understanding how Li-pegmatites form in the first place. Studies of pegmatites from the Archean terrains of Canada made early advances in understanding pegmatite petrogenesis and classification6,7,8,9,10. Studies of post-Archean occurrences have also influenced models for LCT type pegmatite genesis in Archean and younger terranes11,12,13,14 and have thus influenced strategies for finding new Li resources. Rare studies have acknowledged a potential6 or likely15 role of juvenile, meta-igneous, rocks in the melt-sources of some granite—Li-pegmatite systems. However, most studies, and consequent exploration strategies, conclude that Li-pegmatites ultimately require a sediment-rich crustal source12,16,17,18 buried to melting depths during crustal thickening2. This produces peraluminous S-type granitic magmas capable of yielding Li-rich residual liquids by extended crystallisation18,19,20,21 or through remelting during later thermal events22. As Li-concentrations in pegmatites can exceed levels normally considered possible through mineral/melt partitioning in granitic melts, source evolution is thought to require multiple stages of crustal reworking and enrichment in Li and associated rare metals such as Cs, Rb, Nb, Ta and Sn19,22, or zone-refining type crystallisation models18.

‘Sediment-source’ petrogenetic models are commonly assumed to be generally valid for Archean Li-pegmatites11,13,17,23, despite suggestions to the contrary24. However, in the Yilgarn and Pilbara Cratons of Western Australia, where most of the world’s hard-rock Li is currently mined, viable sedimentary sources are not observed.

Li-pegmatites of the Pilbara and Yilgarn cratons are typically emplaced into shear zones at the margins of basalt-dominated (+ultramafic lavas ± sediments) ‘greenstone’ sequences24, proximal to contacts with light-coloured (leucocratic), silica-rich (SiO2 typically > 70 wt%), monzo- to syenogranites, poor in mafic minerals (herein referred to as ‘leucogranites’). Such leucogranites flooded the crust of the Pilbara Craton at c. 2.93 Ga and 2.86–2.83 Ga and the Yilgarn Craton at c. 2.69–2.61 Ga25,26(Fig. 1), reflecting late to post orogenic, craton-wide, mid-crustal melting events in the lead up to final cratonization27,28. These younger leucogranites are spatially associated with Li-pegmatites. They represent the only felsic magmatism contemporaneous with the pegmatites, and isotopic evidence additionally supports a genetic relationship29. In the Yilgarn Craton, magmatic ages (mainly U–Pb from zircon—see ‘Data Availability’) from 87 leucogranite samples show continuous magmatism between 2.655 and 2.61 Ga, embracing the ages of the directly dated pegmatites29,30. One potential exception is the Greenbushes pegmatite in the far southwest of the Yilgarn Craton for which several different Neoarchean ages have been proposed30.

Geological maps, a, b of the Yilgarn Craton, showing the distribution of main granite types; c of the Pilbara Craton showing the location of leucogranite suites. TTG refers to rocks of the Archean tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite series, also forming the main component of ‘unassigned granites’ in (c).

Because melt-fertile metasedimentary sources are characteristically peraluminous, with an Aluminium Saturation Index (ASI = mol Al/(Ca + Na + K)) > 1.1, the evolution of S-type granite magmas does not result in ASI < 1.031. Although the Yilgarn and Pilbara leucogranites evolve to ASI values between 1.0 and 1.1, the trend with decreasing silica is towards ASI < 1. This requires metaluminous (i.e. ASI < 1) parental magmas (Fig. 2) formed through melting of crustal source regions dominantly of felsic metaigneous origin32.

Variation in the Aluminium Saturation Index [ASI = Molecular ratio Al/(Ca + Na + K)] with SiO2 for leucogranites of the Yilgarn and Pilbara cratons. Note that the leucogranites form fields that follow the same trends as those of the tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite (TTG) series rocks which represent melts of mafic, igneous, lower crust32.

In both the Yilgarn and Pilbara cratons, metasedimentary rocks are minor components of most greenstone belts, and there is little evidence for regionally voluminous clastic accumulations in basement terrains—and certainly not of the extent required to account for the regionally voluminous leucogranites (Fig. 1). Where clastic basins are in areas associated with Li-pegmatites or Li-rich leucogranites, they formed late in the regional Archean tectonic evolution25,26 and exposed metamorphic assemblages typically do not exceed greenschist facies. Hence, nowhere in the Australian Archean record are S-type granites or their residual mineral assemblages identified. In this respect, the Australian Archean record differs from some Archean terranes such as the Superior Province of Canada, where S-type granites and associated pegmatites have been noted33.

Results

If we accept the evidence that Li-pegmatites of the Yilgarn and Pilbara cratons are the evolved products of spatially, temporally and isotopically related leucogranite magmas that were not derived through melting of sedimentary sources, can we demonstrate that alternative melt source regions with a similar intrinsic Li-enrichment (~125 ppm22) existed in the right place and at the right time to explain the presence and distribution of Li-rich leucogranites? To investigate this, we use a large dataset combining new and published whole-rock geochemical data (4531 Samples), SIMS zircon U–Pb geochronology and whole-rock Sm-Nd isotope data34,35,36 (see ‘Data Availability’). Datasets covering the Yilgarn Craton are considerably more extensive than those for the Pilbara Craton, and hence much of our discussion is centred on the former craton.

The median Li concentration for the Yilgarn leucogranites is ~22 ppm, and we consider concentrations > 70 ppm (95 percentile) to be anomalous. The maximum whole-rock concentrations of the leucogranites are ~300 ppm and ~450 ppm in the Yilgarn leucogranites and c. 2.85 Ga Pilbara leucogranites respectively. This is significantly lower than the 5000–11,000 ppm37 required for melt saturation of primary Li aluminosilicates, but similar to the Li concentrations of granites elsewhere thought to be genetically related to Li-pegmatites21,38,39. For example, leucogranites with an average of ~200 ppm Li (80–560 ppm range) are considered parental to lepidolite-saturated magmas of southern China with 2200–19,300 ppm Li and with no physical evidence of intermediate compositions39. Similarly, the Lhozhag leucogranite, with 23–108 ppm Li has been shown to be the parental magma to spodumene pegmatites in the eastern Himilaya21. In the case of the Yilgarn and Pilbara leucogranites, it is possible that Li might have been lost to alteration or weathering. It is also possible that whole-rock Li concentrations underestimate original magmatic Li concentrations. Nevertheless, the trend to higher Li with decreasing K/Rb (Fig. 3) (and decreasing modal biotite) clearly reflects igneous differentiation. Irrespective, our purpose here is not to investigate the complex processes that ultimately allow felsic magmas to reach Li-saturation, but to reconcile the presences of globally predominant Li-pegmatite resources with the absence of sedimentary melt sources.

Yilgarn Craton leucogranites

Like other Archean cratons, the Yilgarn and Pilbara cratons are dominated by rocks of the tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite (TTG) series and by leucogranites, reflecting melting of mafic lower-crust and of compositionally more evolved mid-crust respectively32. In both cratons (Fig. 1), rocks of these series collectively comprise at least 80% of granitic rocks in roughly equal proportions. TTGs in the Yilgarn Craton form basement to, and have intruded into, greenstone belts.

The abundant, mildly peraluminous, leucogranites of the Yilgarn Craton typically contain minor amounts of biotite (±fluorite, allanite–titanite) and dominate the vast granitic tracts separating greenstone belts (Fig. 1a). Approximately 95% of 170 dated leucogranites within the Yilgarn Craton formed in the period from c. 2.7 to 2.6 Ga, with the onset of voluminous magmatism coinciding with the c. 2.67 Ga end of greenstone deposition and start of regional crustal thickening26. Apart from pegmatites, these leucogranites represent the only felsic magmatism after c. 2.65 Ga. This post-orogenic period accounts for 54% of dated leucogranites and ~80% of the observed anomalies in Li (or Cs > 8 ppm where Li has not been determined), consistent with all dated Li-pegmatites being 2.655 Ga or younger29. Viewing the entire leucogranite population, ~60% of samples with anomalous Li occur within 5 km of a known granite–greenstone contact (Fig. 4). This increases to 65% in the eastern part of the craton, where generally higher crustal levels are exposed, suggesting that uplift of the more deeply eroded southwestern Yilgarn has removed greenstones but not those Li-rich leucogranites emplaced at deeper levels.

Nd-isotopic analyses of Yilgarn leucogranites (n = 126) show a total ɛNd (2.65Ga) range from c. −8 to +2, reflecting melt sources of widely differing bulk age and composition (Fig. 5a). Nearly all samples showing anomalous concentrations of Li and Cs fall in the most radiogenic part of the array for leucogranite (ɛNd (2.65Ga) = −2.0 to +2.0) and largely overlap the most juvenile part of the Nd-isotopic array for all Yilgarn felsic rocks (Fig. 5a). This implies a link between Li endowment and the age of the magma source.

Since many of the leucogranites do not contain abundant inherited zircon40,41, the zircon saturation thermometer42 can be used to estimate magmatic temperatures. Although the thermometer is strictly applicable to liquid compositions, the partial cumulate assemblages studied here return what appear to be reasonable temperatures, consistently between ~750 and 820 °C throughout the Neoarchean evolution of the Yilgarn Craton (Fig. 5b). However, from ~2.66 Ga onwards, two temperature trends are discernible. The first trend continues the 750–820 °C path and includes nearly all leucogranites with anomalous Li (or Cs). The second trend shows temperatures increasing to as high as ~950 °C by c. 2.6 Ga and includes nearly all leucogranites with anomalous Nb concentrations (>25ppm). Leucogranites forming the high-temperature trend also include a group that can be distinguished by enrichments in TiO2, Fe2O3T, Y, Nb and heavy rare earth elements, characteristics of A-type granites43. The Ti-enriched leucogranites lie within the non-radiogenic portion (ɛNd (2.65Ga) mostly < −2.0) (Fig. 5a) of the Nd-isotopic compositional field of leucogranites, suggesting melting of crustal sources that were older than the sources for leucogranites with anomalous Li (Cs). These compositional variations suggest melting of crustal sources over a range of temperatures (and perhaps depths) with higher crustal temperatures allowing fusion of older and more refractory crustal components (i.e. transitioning to more A-type characteristics). Regardless of the process forming the Ti-enriched leucogranites, magmatic enrichments in Li do not seem to have occurred, although such compositions may favour formation of niobium-yttrium-fluorine (NYF) rare metal pegmatites.

Spatial relationship between Li-pegmatites, leucogranites, greenstone–granite contacts and isotopically juvenile sources

The spatial association between Li-pegmatites and greenstone–granite contacts is well established but not well understood24. The association between Li-rich leucogranite and greenstone–granite contacts (Figs. 4, 6) suggests that sources of Li-enriched leucogranite developed in association with greenstone belt evolution and with greenstone–granite contacts. Our data also shows that these sources are surprisingly isotopically juvenile. This is consistent with Li-rich leucogranites, and their source regions, typically lying within zones of felsic crust with primitive Nd-isotopic compositions surrounding many Yilgarn greenstone belts or within regions characterised by isotopically primitive granite source regions (Fig. 6). The isotopic gradients displayed in Fig. 6 specifically suggest that the crustal source regions of granites became more juvenile closer to greenstone belts.

The role of hydrated, mantle-derived magmas—sanukitoid series

Sanukitoid describes a series of rocks derived through hornblende-dominated fractionation of mantle-derived, mafic–ultramafic lamprophyres. At upper crustal levels they are dominated by evolved compositions in the monzodiorite to diorite range but typically retain Mg# > 60 and elevated Sr, Ba and LREE implicating melting of a hydrated, metasomatized, mantle source44,45,46. They form the most hydrous Archean magmas known46. Sanukitoid series rocks also represent the most isotopically primitive felsic magmas in the Yilgarn Craton, with ɛNd (2.65 Ga) values up to +2.5 (Fig. 5a). They form 5–10% of the granite inventory of the Yilgarn Craton and are virtually restricted to greenstones belts (Fig. 1b). Roughly 90% of exposed sanukitoid samples were emplaced along shear zones within greenstone belts or at greenstone margins, and 97% of samples are exposed within 5 km of greenstone–granite boundaries (Fig. 4), implying a relationship with greenstone forming processes and architecture34. In the Yilgarn Craton, sanukitoid magmatism occurred continuously from 2.7 to 2.65 Ga, overlapping the early period of leucogranite magmatism, but was very rare or absent during the subsequent, and peak, period of pegmatite–leucogranite magmatism26. Emplacement during this prolonged duration of sanukitoid magmatism occurred as a series of pulsed, nested, magma batches each intruding wholly to partially solidified earlier sanukitoid intrusions, as indicated by a complex cognate xenolith suite and abundant antecrystic zircons47.

We suggest that the isotopic patterns seen in Fig. 6 can largely be accounted for in terms of the large proportion of hydrated mantle-derived magmas, and their felsic derivative melts (sanukitoid series magmas) that were incorporated into greenstone-proximal melt-sources during the late-stage (c. 2.7–2.65 Ga) construction of the greenstone sequences34. These interpretations suggest that these mantle-derived ‘sanukitoids’ form a major component of the crustal melt-source of Li-rich leucogranites in the Yilgarn Craton.

Comparisons with Pilbara Craton granites

Yilgarn leucogranite magmatism occurred without a perceptible break between c. 2.69 and 2.61 Ga. In contrast, at least two distinct episodes of leucogranite magmatism (c. 2.93 Ga and 2.86–2.83 Ga) occurred in the Pilbara Craton, the two groups largely overlapping in geographical extent (Fig. 1c), but broadly distinct in terms of compositional range. In particular, the older Sisters Supersuite48,49 leucogranites show a much wider compositional range that extends to lower SiO2 (mostly < 74 wt%) and higher K/Rb ratios (99% > 120) than the younger Split Rock Supersuite (SiO2 mostly > 73 wt%, K/Rb mostly < 150) (Supplementary Fig. 1), with limited overlap. In the regions where both groups crop out, major- and trace-element trends and Nd-isotope data suggest that younger Split Rock Supersuite leucogranites either represent lower degree melts of the same source compositions that produced the older leucogranites, or are partial melts of the Sisters leucogranites themselves, or both (Fig. 7c, and Supplementary Fig. 1).

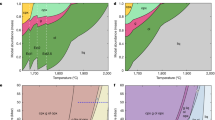

a Geological basement map of the central portion of the Pilbara Craton; b Nd-isotope map covering the same region as in (a) and contoured for two-stage depleted mantle model ages (TDM2). Also shown is the boundary between the East Pilbara Craton and the Central Pilbara48,49, the ‘juvenile western margin’ (bold dashed lines) as well as the outlines of sanukitoid (red dash) and Split Rock leucogranites (grey dash); c Plot of Nd-isotopic composition (initial ɛNd) against magmatic age for felsic magmatic units throughout the Pilbara Craton. Although granites within the area outlined by the bold dashed line in (b) (denoted ‘juvenile western margin’) lie within the ‘geological’ East Pilbara (based mainly on greenstone stratigraphy), they are isotopically equivalent to the juvenile Central Pilbara. Pink band shows the isotopic evolution of old (>3.3 Ga) Pilbara crust. Gold stars in (a, b) represent major Li-pegmatite projects or mines. Nd-isotope data refs. 35,36.

Craton-wide, the Nd-isotopic compositions of Split Rock leucogranites range from ɛNd (2.85Ga)<−5 to + 1.8 (Fig. 7). The radiogenic part of this range occurs only in a northeast-trending ‘juvenile’ corridor (‘juvenile western margin’ in Fig. 7b, c) between the central Pilbara and the western part of the Eastern Pilbara, where the ɛNd (2.85Ga) values of the Split Rock leucogranites and the Sisters leucogranites overlap (Fig. 7). Here, both the 2.93 Ga and 2.86–2.83 Ga leucogranites are too radiogenic to be derived from pre 3.2 Ga components of Pilbara lithosphere alone35,36,50,51, i.e. they require an additional younger component. This ‘juvenile’ corridor includes the two major operating Li-pegmatite mines of the Pilbara Craton – Wodgina and Pilgangoora (Fig. 7). Notably, the Hf isotope composition of cassiterite from the Wodgina Li-pegmatite mine also requires a source that was younger than pre 3.2 Ga Pilbara lithosphere29.

Sanukitoid magmatism is also well established in the central Pilbara Craton and has been related to parental mafic–ultramafic partial melts extracted from a mantle source metasomatized during a 3.2–3.12 Ga subduction event that reunited the Eastern and Western Pilbara cratons25,52. They form a voluminous c. 2.945 Ga suite emplaced along crustal-scale structures related to the slightly earlier evolution of the clastic c. 2.97 Ga Mallina Basin. The sanukitoids also occur peripheral to, and southeast of, the Mallina Basin, intruding granite–greenstone contacts, and form xenoliths within younger leucogranite, within the juvenile western margin between the central Pilbara and in the Eastern Pilbara (Fig. 7a). Here, the leucogranites also overlap the Nd-isotopic compositional range of the sanukitoids and collectively comprise the most radiogenic felsic components of the Pilbara crust. This is particularly apparent surrounding the Wodgina Li mine (the single Nd-isotopic data point near Pilgangoora is likewise superchondritic) (Fig. 7).

As in the Yilgarn Craton, the Pilbara leucogranites spatially and temporally associated with Li-enrichments have the most radiogenic Nd-isotope compositions, localised within primitive zones of felsic crust (Fig. 7) likely reflecting the earlier intrusion of sanukitoid.

Discussion

Regional geological and geochemical considerations indicate that most Li-pegmatites of the Yilgarn and Pilbara Cratons are related to Li-rich leucogranitic magmas that were not derived from sediment-rich crustal sources. Instead, our data strongly suggest that these Li-rich leucogranites formed through melting of crustal sources that had specific isotopic compositions resembling sanukitoids and that formed along greenstone–granite contacts known to have previously channelled large volumes of sanukitoid magmas.

The voluminous leucogranite magmatic episodes in both cratons reflect late to post orogenic, craton-wide, mid-crustal melting in the lead up to final cratonisation27,28. Geochemical and isotopic trends and thermal evolution modelling27,32 are consistent with these mid-crustal sources essentially comprising metaigneous components dominated by earlier TTG. Our data suggest that the Li-rich leucogranites formed through melting crustal source regions that were previously intruded by sanukitoid magma in the root zones of greenstone belts (Fig. 8).

Schematic block diagrams representative of the eastern Yilgarn Craton showing, a granitic magmatism at the late stage of greenstone-belt evolution within an already TTG-rich crustal column. Magmatism includes ongoing TTG production from the more mafic lower part of the crust, leucogranite production from the more TTG-rich mid-levels of the crust and sanukitoid series rocks from the lithospheric mantle. Magma ascent and emplacement is facilitated by crustal-scale structures involved in the formation and evolution of the greenstone belts. b At c. 2.65 Ga, biotite-dehydration melting becomes viable at crustal levels as shallow as ~20 km27. Leucogranite melts formed at this stage additionally include those formed from altered and hydrated sanukitoid-infused sources in the immediate root zones beneath greenstone-belts. In this respect, production of Li-enriched Archean granites is intricately linked to greenstone-belt formation. Today’s surface level (depicted) exposes c. 2.65 Ga ‘surface’ deposits and is a reasonable estimation of the surface during leucogranite magmatism. In the case of the southwest Yilgarn, the present surface exposes crustal levels perhaps slightly higher than those at which biotite dehydration melting was possible.

We suggest that metasomatically hydrated and enriched mantle lithospheric source regions yielded mafic to ultramafic partial melts during the late stages of greenstone belt development. These magmas were channelled along crustal-scale structures, including greenstone–granite contacts, related to greenstone belt formation, fractionating to strongly hydrous felsic sanukitoid intrusions (Fig. 8). We hypothesise that later melting of these greenstone-proximal crustal regions produced leucogranite magmas intrinsically more enriched in Li (Cs, Rb) and with higher ɛNd (2.85Ga) and ɛHf (2.85Ga) values than contemporaneous leucogranites produced in regions distal to greenstone belts. These enriched leucogranite magmas either directly fractionated to the extent required to produce Li-rich pegmatitic liquids or perhaps solidified and were again partially remelted and fractionated22, prior to yielding pegmatitic magmas. To investigate this hypothesis, we assess evidence that interaction with sanukitoid might lead to Li enrichment of a putative mid-crustal melt source region.

Were sanukitoids Li-rich?

It has been suggested that Phanerozoic mantle source regions metasomatically enriched at subducting margins through melt-infiltration, rather than fluid-infiltration, can produce primitive magmas with 2–3-fold enrichment in Li (to ~13 ppm) compared to magmas derived from unenriched mantle53. These primitive Li-enriched magmas have the additional capacity to fractionate to Li-enriched residual felsic melts (Li > 100 ppm53). There is an additional potential for a two-fold increase in the concentrations of Li in mantle-derived magmas formed beneath thick (~60 km) crust, reflecting lower degrees of mantle melting (i.e. greater melt enrichment)54.

The variation in Li concentration with Mg# for least-altered samples of Yilgarn and Pilbara sanukitoids shows a poorly defined trend to slightly higher Li concentrations broadly consistent with fractional crystallisation. Perhaps clearer is that least-altered samples can have concentrations as high as 50 ppm and that primitive magmas have Li concentrations as high as 21 ppm (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Sanukitoid-related Li-rich alteration assemblages

Micas, and biotite in particular, are the main crustal carrier of Li, Cs, Rb and volatiles, and can be a major host of rare metals such as Sn, W, Nb and Ta (refs. 22,55,56,57). Magmatic biotite can contain Li-concentrations in the several 1000’s ppm58,59. Even in existing sediment-source Li-pegmatite models, the key to forming and preserving a Li enriched source is primarily related to the capacity of a source rock to form micas that both retain existing Li (Cs, Rb) and capture additional contributions from brines or circulating hydrothermal fluids.

Sanukitoids represent the most hydrated magmas known from the Archean Eon, with parental magmas estimated to have up to 7–9 wt% dissolved H2O (ref. 46). This ensures that they reached vapour saturation at an early stage of ascent and crystallisation. Experimental work on partitioning of Li between felsic melts and coexisting fluid phases60 for magmas of calc-alkaline compositions suggest that Li has a moderate preference for the melt phase (DLifluid/melt ~ 0.3–0.5), although this is dependent on the Cl and CO2 content of the fluid61,62. This is consistent with the observed magmatic enrichment trends for evolving sanukitoids (Supplementary Fig. 2) but also allows for a large proportion of magmatic Li to enter the vapour phase and be transported along country rock fluid pathways. Biotite-rich assemblages are a prominent feature of alteration haloes observed around sanukitoid intrusions63 in the Yilgarn Cratons and are hence also expected to form a large component of the mid-crustal regions lying in the ‘sanukitoid-infused’ root zones of greenstone belts (Fig. 8). The complex, pulsing, emplacement mode of sanukitoids, as indicated by the abundance of cognate xenoliths47,52, suggests that in addition to country rock, earlier sanukitoid was probably also altered as successive magmatic pulses achieved vapour saturation. Biotite in alteration zones related to sanukitoid emplacement has concentrated up to 700 ppm Li (ref. 63). Anomalously Li-enriched sanukitoid samples in our dataset (Supplementary Fig. 2) include sanukitoid variably biotite-altered during subsequent sanukitoid emplacement and show Li concentrations up to 300 ppm. Consequently, it seems plausible that, irrespective of whether primary sanukitoid magmas were Li-enriched or not, mid-crustal regions lying in the ‘sanukitoid-infused’ root zones of greenstone belts contained enrichments in Li at least similar to the 125.5 ppm global average of siliciclastic sedimentary sources22.

Source melting and crustal recycling

The thermal conditions in the Yilgarn Craton evolved primarily due to the upwards magmatic redistribution of radiogenic heat-producing elements (U, Th and K), as well as magmatic advection itself, in the lead up to cratonization. Recent thermal modelling27,64 has shown that conditions favouring biotite-dehydration melting were likely achieved at mid-crustal levels after c. 2.70 Ga, and at depths as shallow as 20 km or less soon after 2.65 Ga when most Li-rich leucogranite magmatism occurred. This thermal evolution is largely independent of sanukitoid intrusions but indicates that very soon after greenstone-proximal, sanukitoid-infused source regions formed, conditions became regionally favourable for remelting of mid-crustal sources to form younger leucogranites. Where this included greenstone-proximal, sanukitoid-infused, source regions, we predict that Li-rich leucogranite magma would have formed (Fig. 8), analogues in many respects with recent source recycling models for Li-pegmatites22. In this respect, Archean Li-rich leucogranites and LCT pegmatites worldwide might be viewed as a reflection of final cratonization. The Li concentrations in the resulting leucogranites will depend on the amount of source enrichment, but also on the proportion of source biotite and the temperature interval required to achieve complete biotite breakdown19.

The thermal evolution of the Pilbara Craton is less well constrained than that of the Yilgarn Craton and possibly more complex, given the large time gap between Split Rock and Sisters leucogranite magmatism. Field, geochemical and isotopic evidence suggest the evolution of the older leucogranites involved melting a sanukitoid-bearing source and that either deeper crustal equivalents of older leucogranites then remelted to form the distinctly younger leucogranites or the younger leucogranites represent lower degree partial melts of the same sanukitoid-rich source that produced the older leucogranites. If the older leucogranites form a source component to the younger leucogranites, then the increase in mean Li concentration from the older (2.93 Ga) leucogranites (54 ppm; 95 percentile > 101 ppm) to the younger leucogranites (80.5 ppm; 95 percentile > 247 ppm) might reflect an additional crustal Li-enrichment event. Leucogranite magmatism in the Yilgarn Craton occurred over a similar duration as that in the Pilbara Craton, but geochronological evidence identifies no clear breaks in magmatism and no time-constrained compositional variation. Recycling within the Yilgarn leucogranite suite nevertheless also remains possible.

Although our purpose here is not to investigate the transition from leucogranite to Li-pegmatite, it has been suggested that many Precambrian rare metal pegmatites typically appear to have evolved from much more voluminous granite systems than younger counterparts64. Larger melt volumes potentially allowed combinations of fractional crystallisation and zoning-refining type crystallisation processes65 to play the primary role in Li-enrichment, provided effective means of liquid extraction and ponding existed65. Although extended and complex fractionation paths do not make sense if a metasedimentary source model is applied to Australian Archean terranes, it is fully consistent with the outcrop and geophysically inferred extents of the leucogranites of those terranes. This is particularly evident in the case of the Pilbara Craton (e.g. Fig. 1c), where batholithic tracts of leucogranite lying at or close to granitic minimum melt compositions (Fig. 9), can potentially be spatially and temporally linked to Li-pegmatite systems.

Compositions of leucogranites expressed in terms of normative quartz (Q)—albite (Ab)—and orthoclase (Or) components. The density cloud contains data for the Yilgarn leucogranites and the c. 2.93 Ga Sisters Supersuite leucogranites of the Pilbara Craton. Red dots show the composition of the c. 2.86–2.83 Ga Split Rock leucogranites of the Pilbara Craton. Thin black lines show the positions of the water-saturated quartz + feldspar cotectics labelled with pressure69. Green line traces the composition for the granite minima at pressures from 1 to 10 kbar70. Blue line traces the composition for the granite minima at excess water at 1 kbar and with 0 to 4% added F71.

Conclusion

Studies positing that Li-pegmatites represent extreme residual magmas extracted from S-type leucogranite parental bodies are typically based on the observation that contemporaneous, strongly peraluminous, and often isotopically similar S-type magmas are found nearby. Archives of granite geochemistry for the Australian Archean are amongst the most detailed of granitic terranes globally34. Paradoxically, whilst pegmatite in Australian Archean terranes currently represents the world’s most productive source of Li from hard-rock sources, the granite archives reveal no evidence for S-type granites and hence for voluminous sedimentary stratigraphy that might have undergone melting. The obvious conclusion is that other mechanisms can be responsible for generation of Li-rich leucogranites and these may have been more important, at least in the Archean.

A more plausible melt-source for Li-rich leucogranites and related Li-pegmatites in the Australian Archean cratons includes mid-crustal felsic domains marginal to greenstone belts, where source enrichment in Li is controlled by volatile-rich mantle derived magmas channelled along crustal-scale structures that controlled greenstone basin development. It is quite likely that this also applies to other Archean Cratons. Greenstone–granite terranes in Zimbabwe, for example, closely resemble the Yilgarn Craton in terms of granite compositions, including sanukitoids, and have Li-pegmatites that appear to be related to late, strongly fractionated leucogranites66.

Our findings do not invalidate the sediment-source models for post-Archean (or indeed some Archean) LCT-pegmatites, particularly where strongly peraluminous granites and peraluminous-granite trends are also found, but there is no compelling reason why Li-pegmatites in post-Archean terranes could not have evolved in similar settings and from similar sources as those in the Yilgarn and Pilbara Cratons. Whether these Archean settings have direct analogues in modern plate tectonic settings remains uncertain32,67 and is beyond the scope of this study. However, the geological environments described here do share many similarities with modern continental arcs. In both, voluminous dioritic to granodioritic magmas evolved from metasomatically enriched mantle melts are emplaced into thick crust along linear crustal-scale structures. These magmas have the capacity to enrich the mid- to upper crust with Li (refs. 53,54), and potentially even link mantle source regions with evaporite-related salar brine Li deposits, at the surface, in a crustal scale Li-cycle54,68. Within this context it is possible that having post-collisional, basin-forming, crustal-scale structures able to channel hydrated mantled-derived magmas (e.g. sanukitoid or their post Archean equivalents, including appinites), is the most important factor in developing Li-pegmatites – even some directly related to melting metasedimentary basins.

Methods

The geochronological data and Sm–Nd isotope data contained in refs. 35,36,37 are mostly from databases maintained by the Geological Survey of Western Australia (GSWA) and Geoscience Australia (Canberra) and were carried out mainly onwards of 2000 and at a range of laboratories and institutions. The majority of the SIMS zircon U–Pb geochronology was collected at the SHRIMP facilities either at Geoscience Australia, in Canberra, or at the John de Laeter Center, Curtin University, Perth.

Most whole-rock major- and trace-element geochemical data in ref. 35 and in the Supplementary information files (Supplementary Table 1) were collected since 2020 and are on samples either newly collect during GSWA mapping/sampling programs or re-analyses of archive samples originally collected by GSWA or Geoscience Australia (>80% of archive samples). New samples were visibly inspected, and any weathering or excessive vein material was removed. Each sample was crushed by the GSWA using a plate jaw crusher and splitter and milled by ALS using a low-Cr steel mill to produce a pulp with a nominal particle size of 85% < 75 μm. A quartz–feldspar aggregate material containing below detection level concentrations of transition and precious metals was milled between each sample to scrub any remaining pulp residue from the previous sample. Representative pulp aliquots were analysed for 14 elements as major and minor oxide element components, mass LOI and 60 elements as trace elements. Major and minor elements were determined by mixing a 0.66 g aliquot of sample with lithium borate flux (LiBO2, LiB4O7 and LiNO3) in a 1:10 ratio, and then fusing the mixture at 1025 °C and pouring it into a platinum mould. The resulting disk was analysed by XRF (ALS method ME-XRF26). LOI was determined by thermogravimetric analysis (ALS method ME-GRA05). For trace elements associated with minerals that are not fully dissolved by mixed acid digests alone (i.e. Cr, V, Cs, Rb, Ba, Sr, Th, U, Nb, Zr, Hf, Y, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb and Lu), an aliquot of the sample was mixed with lithium borate flux and fused, then digested in acid and analysed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS; ALS method ME-MS81). For the remaining trace elements (Ag, As, Be, Bi, Cd, Co, Cu, Ge, In, Li, Mo, Ni, Pb, Re, Sb, Sc, Se, Te, Tl and Zn); that is, predominantly transition metals, a 0.25 g aliquot of sample was digested with a mixture of concentrated acids (HClO4, HNO3 and HF), heated at 185 °C until incipient dryness, then leached with 50% HCl and diluted to volume with weak HCl, then analysed by ICP-MS and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ALS method ME-MS61L).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data used in this manuscript (including those required to produce the Figures) are included in the published article (and its supplementary information files). These include a recent whole-rock geochemical and SIMS zircon U–Pb geochronology dataset for the Yilgarn Craton34, and whole-rock Sm–Nd isotope data from both the Yilgarn and Pilbara cratons35,36. New whole-rock geochemical and Sm–Nd isotope data for the Pilbara Craton are also presented. All analytical data are available at Figshare (at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29561312).

References

Kesler, S. E. et al. Global lithium resources: Relative importance of pegmatite, brine and other deposits. Ore Geol. Rev. 48, 55–69 (2012).

Bradley, D. C., McCauley, A. D. & Stillings, L. L. Mineral-deposit model for lithium-caesium-tantalum pegmatites. US Geological Survey Report 2010-5070-O, https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20105070O (2017).

Gardiner, N. J., Jowitt, S. M. & Sykes, J. P. Lithium: critical, or not so critical? Geoenergy, 2, https://doi.org/10.1144/geoenergy2023-045 (2024).

U.S. Geological Survey, 2025, Mineral commodity summaries. U.S. Geological Survey, 212, https://doi.org/10.3133/mcs2025 (2025).

Černý, P. & Ercit, T. S. The classification of granitic pegmatites revisited. Can. Mineral. 43, 2005–2026 (2005).

Goad, B. E. & Černý, P. Peraluminous pegmatitic granites and their pegmatite aureoles in the Winnipeg River district, southeastern Manitoba. Can. Mineral. 19, 177–194 (1981).

Černý, P. Distribution, affiliation and derivation of rare-element granitic pegmatites in the Canadian Shield. Geol. Rundsch. 79, 183–226 (1990).

Černý, P. Rare-element granitic pegmatites. Part II: Regional to global environments and petrogenesis. Geosci. Can. 18, https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/GC/article/view/3723 (1991).

Breaks, F. W., Selway, J. B. & Tindle, A. G. Fertile peraluminous granites and related rare-element mineralization in pegmatites, Superior Province, northwest and northeast Ontario: Operation Treasure Hunt. Ontario Geological Survey Publication, Open File Report 6099, https://www.geologyontario.mndm.gov.on.ca/mndmfiles/pub/data/records/OFR6099.html (2003).

Selway, J. B., Breaks, F. W. & Tindle, A. G. A review of rare-element (Li-Cs-Ta) pegmatite exploration techniques for the Superior Province, Canada, and large worldwide tantalum deposits. Explor. Min. Geol. 14, 1–3 (2005).

Martin, R. F. & De Vito, C. The patterns of enrichment in felsic pegmatites ultimately depend on tectonic setting. Can. Mineral. 43, 2027–2048 (2005).

Černý, P., London, D. & Novak, M. Granitic pegmatites as reflections of their sources. Elements 8, 289–294 (2012).

Yang, X. M., Drayson, D. & Polat, A. S-type granites in the western Superior Province: a marker of Archean collision zones. Can. J. Earth Sci. 56, 1409–1436 (2019).

Wise, M. A., Müller, A. & Simmons, W. B. A proposed new mineralogical classification system for granitic pegmatites. Can. Mineral. 60, 229–248 (2022).

Černý, P. Contrasting geochemistry of two pegmatite fields in Manitoba: products of juvenile Aphebian crust and polycyclic Archean evolution. Precambrian Res. 45, 215–234 (1989).

Müller, A., Romer, R. L. & Pedersen, R. B. The Sveconorwegian pegmatite province—thousands of pegmatites without parental granites: Can. Mineral 55, 283–315 (2017).

Steiner, B. M. Tools and workflows for grassroots Li–Cs–Ta (LCT) pegmatite exploration. Minerals 9, 499 (2019).

London, D. Ore-forming processes within granitic pegmatites. Ore Geol. Rev. 101, 349–383 (2018).

Ballouard, C. et al. A felsic meta‑igneous source for Li‑F‑rich peraluminous granites: insights from the Variscan Velay dome (French Massif Central) and implications for rare‑metal magmatism. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 178, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-023-02057-1 (2023).

Roda-Robles, E. et al. Li-rich pegmatites and related peraluminous granites of the Fregeneda-Almendra field (Spain-Portugal): a case study of magmatic signature for Li enrichment. Lithos 452, 107195 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Petrogenetic link between leucogranite and spodumene pegmatite in Lhozhag, eastern Himalaya: Constraints from U–(Th)–Pb geochronology and Li–Nd–Hf isotopes. Lithos, 470–471, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2024.107530 (2024).

Koopmans, L. et al. The formation of lithium-rich pegmatites through multi-stage melting. Geology 52, https://doi.org/10.1130/G51633.1 (2023).

Parsa, M. et al Pan-Canadian predictive modelling of lithium–caesium–tantalum pegmatites with deep learning and natural language processing. Nat. Resour. Res. 34, 639–668 (2025).

Sweetapple, M. T. & Collins, P. L. F. Genetic framework for the classification and distribution of Archean rare metal pegmatites in the North Pilbara Craton, Western Australia. Econ. Geol. 97, 873–895 (2002).

Van Kranendonk, M. J., Smithies, R. H., Hickman, A. H. & Champion, D. C. Secular tectonic evolution of Archaean continental crust: interplay between horizontal and vertical processes in the formation of the Pilbara Craton, Australia. Terra Nova 19, 1–38 (2007).

Czarnota, K. et al. Geodynamics of the eastern Yilgarn Craton. Precambrian Res. 183, 175–202 (2010).

Korhonen, F. J. et al. Radiogenic heat production provides a thermal threshold for Archean cratonization process. Geology 53, 222–226 (2024).

Zibra, I. et al. The importance of being molten: 100 Myr of synmagmatic shearing in the Yilgarn Craton (Western Australia). Implications for mineral systems. Precambrian Res. 406, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2024.107393 (2024).

Kendall-Langley, L. A., Kemp, A. I. S., Grigson, J. L. & Hammerli, J. U-Pb and reconnaissance Lu-Hf isotope analysis of cassiterite and columbite group minerals from Archean Li-Cs-Ta type pegmatites of Western Australia. Lithos 352-353, 105231 (2020).

Wells, M., Aylmore, M. & McInnes, B. MRIWA Report M532—The geology, mineralogy and geometallurgy of EV materials deposits in Western Australia. Geological Survey of Western Australia, Report 228, 187, https://dmpbookshop.eruditetechnologies.com.au/category/reports.do (2023).

Chappell, B. W. & White, A. J. R. I- and S-type granites in the Lachlan fold belt. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 83, 1–26 (1992).

Champion, D. C. & Sheraton, J. W. Geochemistry and Nd isotope systematics of Archaean granites of the Eastern Goldfields, Yilgarn Craton, Australia: implications for crustal growth processes. Precambrian Res. 83, 109–132 (1997).

Breaks, F. W. & Moore, J. M. The Ghost Lake batholith, Superior Province of northwestern Ontario: a fertile, S-type, peraluminous granite-rare-element pegmatite system. Can. Mineral. 30, 835–835 (1992).

Smithies, R. H. et al. Geochemical mapping of lithospheric architecture disproves Archean terrane accretion in the Yilgarn craton. Geology 52, 141–146 (2023).

Champion, D. C. Neodymium depleted mantle model age map of Australia: explanatory notes and user guide. Geoscience Australia, Record 2013/044, https://doi.org/10.11636/Record.2013.044 (2013).

Lu, Y. et al. Samarium-Neodymium Isotope Map of Western Australia. Geological Survey of Western Australia Data Layer, accessed June 2023. https://www.dmirs.wa.gov.au/geoview (2022).

Maneta, V., Baker, D. R. & Minarik, W. Evidence for lithium-aluminosilicate supersaturation of pegmatite-forming melts. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 170, 1–16 (2015).

Cerny, P. & Meintzer, R. E. Fertile granites in the Archean and Proterozoic fields of rare-element pegmatites: crustal environment, geochemistry and petrogenetic relationships. In Recent Advances in the Geology of Granite-Related Mineral Deposits (eds Taylor, R. P. & Strong, D. F.) Canadian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. Vol. 39, 170–207 (1988).

Pollard, P. J. The Yichum Ta-Sn_Li deposit, South China: evidence for extreme chemical fractionation in F-Li-P-rich magma. Econ. Geol. 116, 453–469 (2021).

Wingate, M. T. D., Kirkland, C. L. & Hall, C. E. 193433: biotite monzogranite, Shay Cart Range. Geological Survey of Western Australia Geochronology Record 958, 4, https://dmpbookshop.eruditetechnologies.com.au/category/geochronology-records.do (2011).

Wingate, M. T. D., Lu, Y. & Romano, S. S. 207528: monzogranite, Cat Camp. Geological Survey of Western Australia. Geochronology Record 1418, 3, https://dmpbookshop.eruditetechnologies.com.au/category/geochronology-records.do (2017).

Watson, E. B. & Harrison, T. M. Zircon saturation revisited: Temperature and composition effects in a variety of crustal magma types. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 64, 295–304 (1983).

Collins, W. J., Beams, S. D., White, A. J. R. & Chappell, B. W. Nature and origin of A-type granites with particular reference to southeastern Australia. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 80, 189–200 (1982).

Shirey, S. B. & Hanson, G. N. Mantle-derived Archaean monozodiorites and trachyandesites. Nature 310, 222–224 (1984).

Smithies, R. H. et al. No evidence for high-pressure melting of Earth’s crust in the Archean. Nat. Commun. 10, 5559 (2019).

Oliveira, M. A., Dall’Agnoli, R. & Scaillet, B. Petrological constraints on crystallization conditions of mesoarchean sanukitoid rocks, southeastern Amazonian Craton, Brazil. J. Petrol. 51, 2121–2148 (2010).

Smithies, R. H. et al. Geochemical Characterization of the Magmatic Stratigraphy of the Kalgoorlie and Black Flag Groups—Ora Banda to Kambalda Region. Geological Survey of Western Australia, Report 226, 100, https://dmpbookshop.eruditetechnologies.com.au/category/reports.do (2022).

Hickman, A. H. Northwest Pilbara Craton: a record of 450 million years in the growth of Archean continental crust. Geological Survey of Western Australia, Report 160, 104, https://dmpbookshop.eruditetechnologies.com.au/category/reports.do (2016).

Hickman, A. H. East Pilbara Craton: a record of one billion years in the growth of Archean continental crust. Geol. Geological Survey of Western Australia, Report 143, 187, https://dmpbookshop.eruditetechnologies.com.au/category/reports.do (2021).

Champion, D. C. & Huston, D. L. Radiogenic isotopes, ore deposits and metallogenic terranes: novel approaches based on regional isotopic maps and the mineral systems concept. Ore Geol. Rev. 76, 229–256 (2016).

Kemp, I. S. A., Vervoort, J. D., Petersson, A., Smithies, R. H. & Lu, Y. A linked evolution for granite-greenstone terranes of the Pilbara Craton from Nd and Hf isotopes, with implications for Archean continental growth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 601, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2022.117895 (2023).

Smithies, R. H. & Champion, D. C. The Archaean high-Mg diorite suite: links to tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite magmatism and implications for early Archaean crustal growth. J. Petrol. 41, 1653–1671 (2000).

Schettino, E. et al. Slab melting boosts the mantle wedge contribution to Li‑rich magmas. Sci. Rep. 14, 15168 (2024).

Chen, C., Lee, C.-T. A., Tang, M., Biddle, K. & Sun, W. Lithium systematics in global arc magmas and the importance of crustal thickening for lithium enrichment. Nat. Commun. 11, 5313 (2020).

Gao, X. et al. Trace element (Be, Zn, Ga, Rb, Nb, Cs, Ta, W) partitioning between mica and Li-rich granitic melt: Experimental approach and implications for W mineralization. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 375, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2024.05.004 (2024).

Tischendorf, G., Förster, H. J. & Gottesmann, B. Minor-and trace-element composition of trioctahedral micas: a review. Mineral. Mag. 65, 249–276 (2001).

Van Lichtervelde, M., Grégoire, M., Linnen, R. L., Béziat, D. & Salvi, S. Trace element geochemistry by laser ablation ICP-MS of micas associated with Ta mineralization in the Tanco pegmatite, Manitoba, Canada. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 155, 791–806 (2008).

Ellis, B. S. et al. Biotite as a recorder of an exsolved Li-rich volatile phase in upper-crustal silicic magma reservoirs. Geology 50, 481–485 (2022).

Jancsek, K., Janovszky, P., Galbacs, G. & Toth, T. M. Granite alteration as the origin of high lithium content of groundwater in southeast Hungary. Appl. Geochem. 149, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2023.105570 (2023).

Iveson, A. A., Webster, J. D., Rowe, M. C. & Neill, O. K. Fluid-melt trace-element partitioning behaviour between 1 evolved melts and aqueous fluids: Experimental constraints on the magmatic-hydrothermal transport of metals. Chem. Geol. 516, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.03.029 (2019).

An, Y., Zhang, H., Tang, Y., Lv, Z.-H. & Ma, Z.-L. Lithium partitioning between aqueous fluids and granitic melt and implications for ore genesis of pegmatite-type Li deposits. Ore Geol. Rev. 181, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2025.106567 (2025).

Gion, A. M. & Gaillard, F. The multicomponent exchange of metals between magmatic fluids and silicate melts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 395, 112–134 (2025).

Doutch, D. A. Origin, Geochemistry, Stratigraphic and Structural Setting of the Archean Invincible Gold Deposit, St Ives Gold Camp, Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia. PhD thesis, 330 University of Tasmania (2019).

Tucker, N. M. et al. Ultrahigh thermal gradient granulites in the Narryer Terrane, Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia, provide a window into the composition and formation of Archean lower crust. J. Metamorph. Geol. 42, 425–470 (2024).

London, D. Rare-element granitic pegmatites. In; Rare Earth and Critical Elements in Ore Deposits, Reviews in Economic Geology. (eds Verplanck, P. L & Hitzman, M. W.) Society of Economic Geologists Vol. 18, 165–193, https://doi.org/10.5382/REV.18 (2016).

Chagondah, G. S. Petrogenesis and Metallogenesis of Granitic Rare-metal Pegmatites Along the Southern Margin of the Zimbabwe Craton: Implications to Exploration. PhD thesis 292 University of Johannesburg, South Africa, https://hdl.handle.net/10210/503959 (2022).

Johnson, T. E., Brown, M., Gardiner, N. J., Kirkland, C. L. & Smithies, R. H. Earth’s first stable continents did not form by subduction. Nature 543, 239–242 (2017).

Al-Jawad, J., Ford, J., Petavratzi, E. & Hughes, A.Understanding the spatial variation in lithium concentration of high Andean Salars using diagnostic factors. Sci. Total Environ. 906, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167647 (2024).

Johannes, W. & Holtz, F. Petrogenesis and experimental petrology of granitic rocks. Minerals and Rocks Vol. 22,115–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-61049-3 (Springer, 1996).

Luth, W. C., Jahns, R. H. & Tuttle, O. F. The granite system at pressures of 4 to 10 kilobars. J. Geophys. Res. 69, 759–773 (1964).

Manning, D. A. C. The effect of fluorine on liquidus phase relationships in the system Qz-Ab-Or with excess water at 1 Kb. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 76, 206–215 (1981).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding through the Government of Western Australia’s Exploration Incentive Scheme. Helpful reviews from Robert Linnen and John Mavrogenes, an earlier review from Carl Spandler, and numerous discussions with Scott Halley are greatly appreciated. We acknowledge the guidance of Kariyarra Aboriginal Corporation and the Kariyarra People on whose ground new Pilbara samples were collected. No permissions were required for collection of earlier data. R.H.S., J.R.L., N.H.B., T.J.I., R.E.T., K.G., and F.J.K. publish with the permission of the Executive Director of the Geological Survey of Western Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.H.S., Y.L., project conceptualisation; R.H.S., Y.L., D.C.C., K.F.C. and K.G. sample collection; All authors (R.H.S., Y.L., D.C.C., M.T.S., J.R.L., N.H.B., K.F.C., T.J.I., A.I.S.K., R.E.T., K.G. and F.J.K) contributed to discussions, manuscript writing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks John Mavrogenes and Robert Linnen, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Evan Hastie, Carolina Ortiz Guerrero, Somaparna Ghosh [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smithies, R.H., Lu, Y., Champion, D.C. et al. Giant lithium-rich pegmatites in Archean cratons form by remelting refertilised roots of greenstone belts. Commun Earth Environ 6, 630 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02622-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02622-5

This article is cited by

-

Experimental constraints on the sources of lithium-rich granites and pegmatites

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)