Abstract

Atmospheric and marine heatwaves are intensifying under climate change, increasingly co-occurring with significant impacts on ecosystems and society. Despite their significance, the effects of their concurrence remain poorly understood, particularly the influence on air-sea heat exchange—a key driver of weather patterns and climate variability. Using ERA5 reanalysis data (1940–2022), here we analyse heat flux variations and the marine heatwave intensification during concurrent atmospheric and marine heatwaves in the Mediterranean, a climate change hotspot. We find a sharp increase in latent heat release from the ocean to the atmosphere after concurrence end. This could be linked to the observed marine heatwave intensity dissipation at concurrence end. This effect has strengthened over recent decades, suggesting a transient thermoregulation mechanism linked to atmospheric blocking and ocean stratification changes. Our findings underscore the crucial role of air-sea interactions in modulating marine heatwave dynamics, with implications for climate projections and extreme event predictability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human-induced climate change has already impacted extreme weather and climatic events globally1 by increasing their frequency and/or intensity in recent decades. This trend is expected to strengthen in the coming years with high confidence1. In the context of extreme weather events, the projected increase in atmospheric temperature drastically increases the probability of devastating global-scale atmospheric heatwaves2 (AHWs), which cannot be explained without human-induced climate change. Parallel to this, recent research3 found that the rate of change of global sea surface temperature (SST) has increased, in proportion with Earth’s energy accumulation as ocean heat content (OHC), with 44% of this change due to the acceleration of global SST warming. In the case of the Mediterranean Sea the observed OHC also increased, exceeding the OHC global increase in other regions4, highlighting the Mediterranean area as hotspot of ocean warming with record OHC values observed in 20235. In addition, marine heatwaves (MHWs), which are extreme events of high SST, are becoming more frequent and extreme under climate warming scenarios6,7,8,9. Projections indicate a future increase in the intensity and the annual count of MHW days, with widespread and significant environmental impacts10 expected by the end of the 21st century11.

The Mediterranean region stands out as a hotspot for climate change12,13, where temperature warming is more pronounced than in other regions of the globe14. Long-term increasing atmospheric15,16 and marine17,18 temperatures have strengthened their environmental impacts in the Mediterranean area19,20,21,22,23,24, which will likely increase in future scenarios25,26. In the Mediterranean Sea, AHWs and MHWs have shown an increase in frequency and intensity27,28,29,30, with record-breaking events in recent years31, although AHWs over the sea have been less studied than AHWs over land.

More frequent extreme events will consequently lead to a higher chance of their spatiotemporal concurrence, accompanied by environmental and socioeconomic impacts1,32,33,34. The compounding of extreme events, being the combination of two or more climate hazards, is the cause of many major weather and climate-related catastrophes33. The compounding of AHWs and extreme sea level has increased in frequency over the last decades and will likely increase in future scenarios35. Biological impacts like mass mortality of marine organisms associated with concurrent MHW could also be more severe19,20,21,22,23,24 due to the already established Mediterranean Sea MHW intensification36. The co-occurrence of MHWs and terrestrial AHW has been studied in different regions31,37,38,39, unlike the concurrence of MHW and AHW over the sea, which has not been in-depth studied. Other studies are focused on the relationship between MHWs and other marine or atmospheric extreme events. For example, low chlorophyll40 and acidification41 events or droughts, involving atmospheric blocking42, or between concurrent AHWs and MHWs with drought and wildfires in the Mediterranean region38,39.

The compounding of climate extremes has recently received increasing attention in the scientific literature43. However, there are few studies on the interaction and impacts of compounding AHW-MHW over the ocean. For the Eastern Mediterranean, a statistically significant correlation was found between AHWs and MHWs frequencies and total days, as well as an increase in their co-occurrence44. A recent study has characterised concurrent AHW-MHWs identified in the Mediterranean from 1940 to 202236. This study shows that AHW-MHW concurrence has become more frequent in recent decades and that MHWs intensify in the presence of concurrent AHWs. This intensification could be related to changes in the interactions and energy exchanges at the air-atmosphere interface when concurrence is present. Most Mediterranean AHWs are associated with an anticyclonic stable situation with strong stagnation and subsidence45. This persistent atmospheric stability is usually found to be a driver of MHWs through an increase of solar radiation (clear skies) and calm winds that, in turn, favours upper marine levels stratification, starting or reinforcing MHWs46.

At the ocean-atmosphere interface, heat and moisture fluxes drive the surface energy balance, understood as the sum of different heat transfer components. The net heat flux balance at the air-sea interface (Qnet) is the sum of the radiative heat flux components, namely the incoming net solar radiation (net shortwave radiation, SWRnet) and net longwave radiation (LWR), and two turbulent heat flux components, namely latent (LH) and sensible (SH) heat fluxes47. LH and SH fluxes are dependent on the air-sea interface conditions through seawater evaporation and air-sea temperature differences.

LH flux has increased globally, at least since 1985, similarly to the SST48, which suggests an atmospheric response to ocean forcing. Air-sea heat fluxes can impact atmospheric phenomena such as extratropical cyclone intensification49 or atmospheric frontogenesis50 at the regional scale. The influence of heat fluxes on the development or intensification of atmospheric processes mostly occur on areas where LH and SH fluxes and SST show strong spatial gradients51.

In the Mediterranean, air-sea heat fluxes play a central role in the onset of 44% of MHWs52, especially during the summer months. However, depending on the Mediterranean subregion, other drivers such as SWRnet or SH also play an important role in MHW activity53. LH flux is the major contributor to SST anomalies leading to MHWs54,55,56. A case study on the response of SST to AHWs highlighted the crucial role of air-sea fluxes for the onset of record-breaking SST events57. Hence, heat fluxes are, in some cases and to some extent, drivers of the development of MHWs. The study of heat fluxes is of utmost importance in the compounding of AHWs and MHWs because they could play a role in their primary characteristics’ changes from the non-HW situations or from preexisting stand-alone MHW conditions. AHWs could be considered a driver not only for MHW formation but also for the observed MHW intensification when compounding with an AHW36. A complete understanding of heat flux performance on MHW-AHW concurrence is crucial for MHW forecasting, which still faces many challenges, especially in the Mediterranean58,59,60,61. The concurrence of AHWs and MHWs could also support an extra addition of moisture to lower atmospheric levels62 by means of enhanced evaporation19,20,21,22,23,24,36.

The present work aims to understand the still non-studied/unknown impact of the AHW-MHW concurrence on the air-sea heat flux balance and whether this impact could be related to MHW intensification during concurrence pointed out by Pastor et al.36. The main objective is to describe the changes in heat fluxes during concurrence, focusing on the onset and end stages. These stages represent the transitions between different air-sea heat exchange regimes that result from the absence or presence of the AHW. Although many studies have highlighted the role of air-sea heat fluxes in the life cycle of MHWs this is, to the authors’ knowledge, the first analysis of the heat fluxes on concurrent AHWs and MHWs.

Results

MHW intensity variation on AHW-MHW concurrence onset and end stages

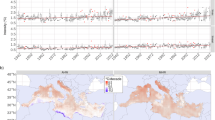

We first analyse the MHW intensity variation around concurrence onset and end (see section ‘Marine heatwave catalogue’ in Methods). Figure 1 shows the daily percentage of concurrent MHW points with a given intensity, highlighting a lower intensity and lesser variability on the days before concurrence onset (i.e. days −5 to −1 in Fig. 1a). In contrast, concurrent days (i.e. days from 0 to 5 in Fig. 1a, and days from −5 to 0 in Fig. 1b) show higher and more spread intensities. An inverse pattern appears at the end of concurrence (i.e. days 1–5 in Fig. 1b), with the spread and magnitude of the MHW intensity value progressively decreasing. We observe a MHW intensification on concurrent points on the concurrence onset of about 0.25 °C on average (Fig. 1a), but with a significant variability around the average. The MHW intensity gradually rises from 2 days before concurrence onset (day −2 in Fig. 1a) until the second concurrent day (day 1 in Fig. 1a). In the following days, until the fifth day of concurrence, the MHW intensity continues to rise on a similar path. Almost symmetrically, the MHW intensity decreases by 0.24 °C just after the concurrence end (day 0 in Fig. 1b)36.

Marine heatwave (MHW) intensity on atmospheric-marine heatwave concurrent points of the MHW from May to September 1940 to 2022. Probability distribution of the MHW intensity (°C) around the (a) concurrence onset (from the five prior days to concurrence onset to the first five concurrent days, T1) and b the concurrence end (from the five last concurrent days and the 5 days after concurrence end, T2). The coloured area represents the percentage of MHW points with a given intensity. The dotted black line shows the daily mean MHW intensity, and the shadowed area between thin black lines depicts the daily standard deviation.

Changes in heat fluxes through AHW-MHW concurrence phases

Once the MHW intensity change during transitional concurrence stages is established, changes in air-sea heat fluxes are analysed. Figure 2 shows heat fluxes averaged over the concurrent points of each MHW, analysed over five distinct periods, namely non-MHW days, non-concurrent MHW days and three AHW-MHW concurrence phases, being before-concurrence (comprising five prior days to concurrence onset), concurrent days and after-concurrence (comprising 5 days after concurrence end).

Net shortwave radiation (SWRnet), net longwave radiation (LWRnet), sensible heat (SH), latent heat (LH) and the net heat balance (Qnet) fluxes on concurrent atmospheric-marine heatwave points on days without marine heatwave (No MHW, white), five prior and posterior days to concurrence (Before concurrence, blue and after concurrence, green, respectively), the other marine heatwave days without concurrence with atmospheric heatwaves (Non-concurrent MHW, grey), and concurrent days (Concurrent MHW, red).

The mean total heat flux balance, Qnet, is about 101 W/m2 on non-MHW and non-concurrent MHW days, but it presents different values through concurrence phases. In comparison with the non-MHW days, the mean Qnet flux rises 41% (41 W/m2) in the before-concurrence and concurrent days phases and decreases 39% (39 W/m2) in the after-concurrence phase, which presents the greatest variability.

The LH flux component displays a similar pattern as Qnet, with the largest changes through the concurrence phases. Compared to the non-MHW days, there is a 32% (27 W/m2) lower LH flux emission from the sea to the air in both before-concurrent and concurrent days phases and a 28% (24 W/m2) greater LH emission in the after-concurrence phase. The most noticeable change in the LH flux is observed from the concurrent days phase to the after-concurrence phase, when there is a mean 93% (53 W/m2) increase in the LH emission from the sea to the air.

Compared to non-MHW days, the SWRnet mean absorption is ~5% (14 W/m2) higher in the before-concurrence and concurrent days phases, while a decrease of about 4% (10 W/m2) is noted in the after-concurrence phase. The other heat flux components, namely LWRnet and SH fluxes, show a stable behaviour, with close mean values and similar variability across the analysed phases. Hence, most of the change in the heat flux balance (i.e. Qnet) is due to the variation in LH from the before-concurrence, through the concurrent days phase, to the after-concurrence phase.

Latent heat flux variation in AHW-MHW concurrence onset and end stages

In the following, we analyse the most remarkable changes in the air-sea heat fluxes, thus, the LH flux variation at the transition from before-concurrence to concurrent days phases (transition T1) and the transition from concurrent days to after-concurrence phases (transition T2). The subsequent analysis shows how the LH flux changes daily, considering each concurrent MHW point independently. Analogous analyses for the total heat flux balance Qnet and the other heat flux components, namely SWRnet, LWRnet and SH, are shown in the Supplementary Material (Figs. S1, S2, S3 and S4).

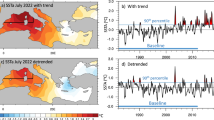

The mean LH emitted from the sea to the atmosphere at the transition T1 (Fig. 3a) exhibits minimal change, with only a 1 W/m2 decrease from the day before concurrence onset to the second concurrent day. Conversely, at the transition T2 (Fig. 3b), the mean LH emission increases in 57 W/m2 from the penultimate concurrent day (day −1 in Fig. 3b) to the first day after concurrence end (day 1 in Fig. 3b).

Latent heat (LH) flux (W/m²) around the (a) concurrence onset (from the five prior days to concurrence onset to the first five concurrent days, T1) and b the concurrence end (from the five last concurrent days and the 5 days after concurrence end, T2) on concurrent points of concurrent atmospheric-marine heatwaves from May to September 1940 to 2022. The coloured area represents the daily probability distribution of the LH flux (percentage of concurrent marine heatwave points with a given LH flux). The dotted black line shows the daily mean, and the shadowed area between thin black lines depicts the daily standard deviation.

We note that the MHW intensity increase at the onset of concurrence (Fig. 1a) does not correspond to a parallel variation in LH flux (Fig. 3a). Nevertheless, there is a consistent variation in both magnitudes at the end of concurrence, consisting of an MHW intensity decrease (Fig. 1b) and an LH ocean to air emission increase (Fig. 3b), denoted by more negative LH flux values.

The LH flux change between the penultimate concurrent day and the first day after concurrence end (i.e. the interest interval on T2) has been assessed across successive 30-year periods from 1940 to 2022 (Fig. 4). The LH flux change on the interest interval on T2 has progressively intensified towards more negative values, from −39 W/m2 in 1940–1969 to −63 W/m2 in 1989–2018 (Fig. 4). This intensification of the LH flux change has accentuated after 1998. A negative LH change indicates an increase in the LH emission from the sea to the air on the first day after the concurrence end, compared to the penultimate concurrent day. We only show this analysis for the interest interval on T2 because of its bigger magnitude with respect to the interest interval on T1 (the day before concurrence onset to the second concurrent day).

There is a reduction of the LH flux emission from the ocean to the air (i.e. positive change) on the interest interval on transition T1 affecting 34% of the MHW concurrent area on average and affecting at least 50% of the MHW concurrent area in 15% of the MHWs (Fig. 5a).

Accumulated concurrent marine heatwave (MHW) area (%) with an (a) latent heat (LH) flux change in the transition from the previous day to concurrence onset to the second concurrent day higher than a given value (W/m2); and b LH flux change in the transition from the penultimate concurrent day to the first day after concurrence end lower than a given value (W/m2). Grey lines represent individual concurrent MHWs; the black line is the corresponding mean. Boxplot represents grey lines values at crossing the vertical red line at LH change equal to 0, showing the distribution of MHW concurrent areas with a (a) positive or (b) negative LH change.

A greater LH emission (i.e. negative change) on the interest interval on transition T2 is observed on at least 50% of the concurrent points in 82% of concurrent MHWs (Fig. 5b). The mean MHW concurrent area with an increased LH emission in the same period is 65% (Fig. 5b). There is a change in the LH of −200 W/m2 in 5% of concurrent points at the interest interval on transition T2. A change of such magnitude is rarely observed at the interest interval on transition T1.

Higher variability between concurrent MHWs is observed in the LH change from the day before concurrence onset day to the first day after concurrence than in the LH change from the day before concurrence onset to the second concurrent day. The magnitude of the change is larger in the transition from the penultimate concurrent to the first day after concurrence end than in the transition from the day before concurrence onset to the second concurrent day.

To assess the possible relationship between MHW intensity and LH change at the transition T2, a Pearson correlation value is obtained for each MHW using the MHW intensity-LH change pairs of its concurrent area. A statistically significant (p < 0.05) negative correlation is found between MHW intensity and subsequent LH release on 81% of concurrent MHWs spanning from –0.03 up to –0.71, meaning that the higher the MHW intensity, the more negative the change in the LH release is (Fig. 6). The most frequent correlation values are comprised in the −0.3 to −0.2 interval, accounting for more than 40% of the concurrent MHW events.

Discussion

This study investigates the air-sea heat exchange dynamics during concurrent AHWs and MHWs, a question still not addressed in scientific literature, in the Mediterranean, a region particularly vulnerable to climate change. Our aim was to elucidate the processes governing variations in the net heat flux (Qnet) and its components during these events, and to assess how transitions between concurrent and non-concurrent conditions may influence MHW intensification on concurrence with AHWs described in a previous study36.

Our analysis of Qnet reveals pronounced changes during AHW-MHW concurrent events. Specifically, we observe a 39% increase in heat absorption from the atmosphere to the ocean during the 5 days preceding and throughout concurrence, followed by a 41% reduction in absorption during the 5 days after concurrence relative to non-MHW or non-concurrent MHW conditions. These shifts are primarily driven by variations in the latent heat (LH) flux, with a secondary contribution from net shortwave radiation (SWRnet), while net longwave radiation (LWRnet) and sensible heat (SH) fluxes remain largely unchanged. Thus, the transition from concurrent to non-concurrent conditions emerges as a hotspot for air-sea interaction dynamics.

Previous studies have established that concurrent MHW intensification occurs33 in the Mediterranean but do not point to the processes accounting for this phenomenon. Our results indicate that increased SWRnet absorption and suppressed LH release during before-concurrence and concurrence phases may contribute to this intensification. This could happen in a similar mechanism to the onset phase of atmospheric-driven MHWs63, even though the gradual onset of MHW warming suggests additional factors are involved. Notably, we consistently observe a marked increase in LH emission from the ocean in over 50% of the concurrent area in most events just after concurrence end, similarly to the net loss of heat to the atmosphere in the MHW decline phase63. The largest LH change occurs over a 3-day period—from the penultimate concurrent day to the first day after concurrence end—and correlates with the MHW intensification during concurrence at an event scale. This enhanced LH release after the concurrence end has intensified since 1940, aligning with long-term trends in SST warming and MHW intensification. Such an increase in LH flux could alter local moisture content and further influence atmospheric processes such as fostering cyclone intensification.

The present analysis shows an MHW intensification during concurrence, in agreement with previous studies36. Our results show, for the first time to our knowledge, that this MHW intensification in concurrence with AHW occurs gradually during the first days after concurrence onset.

A proposed mechanism for the MHW intensification in concurrence with AHWs (Fig. 7) raises/proposes that during concurrent events, AHWs promote MHW intensification by reinforcing upper-ocean stratification and reducing LH loss from the sea. Synoptic blocking—characterised by increased shortwave radiation, associated with reduced cloud cover and reduced wind speed—leads to a shallower mixing layer that limits the entrainment of colder, deeper waters, thereby enhancing heat accumulation. Once concurrence ends, an air mass shift (likely involving drier conditions) and a weakening of stratification allow for a rapid rebound in LH flux, restoring the before-concurrence heat balance.

Our study provides new insights into the air-sea interactions associated with AHW-MHW concurrent events in the Mediterranean. We demonstrate that concurrent AHWs contribute to MHW intensification primarily by altering the surface heat flux balance. A key finding is the substantial increase in latent heat release from the sea at the end of concurrence. This increase in the latent heat release appears to act as a transient cooling mechanism following MHW intensification, which would be in agreement with the role of atmospheric heat fluxes as cooling mechanisms in MHWs in the Red Sea64 and specifically the role of LH flux in the decay phase of the MHWs at global scale54,63. This shift in heat fluxes is consistent with long-term trends in Mediterranean warming and MHW frequency.

Our results highlight the critical role of LH flux variations in modulating MHW dynamics, in concurrence with AHWs. This study offers novel valuable insights for improving forecasting and assessing the broader climatic and ecological impacts of these extreme events. The observed changes in air-sea heat exchange may have broader climatic and ecological implications, influencing local atmospheric circulation, OHC and marine ecosystem stress. The increasing magnitude of post-concurrence latent heat flux release suggests a strengthening feedback loop, which may further amplify Mediterranean climate extremes. Future research should focus on better quantifying the mechanisms driving these heat flux anomalies, with high-resolution ocean-atmosphere coupled models and their potential cascading impacts on regional weather patterns.

Methods

ERA5 data

All the analysis in this work is based on ERA5 reanalysis data65 of the global weather and climate developed by the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasting (ECMWF) under the auspices of the EU-funded Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). ERA5 is a comprehensive global reanalysis dataset, assimilating as many observations as possible in the upper air and near-surface, offering a complete set of atmospheric, ocean-wave and land-surface variables with a 5 km horizontal resolution and time span from 1940 to the present. The variables used in this study are SST and 2-m temperature for the AHW and MHW identification and LH, SH, LWR and SWR to analyse net energy balance (Qnet) at the air-sea interface, with positive values of the heat fluxes indicating a downward direction, from the air to the sea. Hourly values have been aggregated into daily mean values for the analysis. The data set used here corresponds to the regridded subset to a regular lat-lon grid of 0.25° of the full ERA5 data set on native resolution, which amply satisfies the requirements for the present analyses. ERA5 temperature data has been found to compare well with observations from station data for AHW analysis in the Mediterranean region38,39 and good agreement has also been found in the evaluation of SST against observations65,66.

Marine heatwave catalogue

We analyse heat fluxes at the air-sea interface during the concurrence of AHWs and MHWs in the Mediterranean Sea across the extended summers (May–September) from 1940 to 2022. To determine HW events, we used the MHW, AHW and concurrence definitions from Pastor et al.36, who conducted an AHW and MHW concurrence analysis over the Mediterranean Sea.

Their MHW definition is based on the Hobday definition67, which is widely used in scientific literature, but includes some spatiotemporal requirements to qualify as a MHW event. According to Hobday67, a MHW is an event where SST exceeds the 90th percentile for at least five consecutive days. In this work, we have used the MHW spatiotemporal methodology detection developed by the authors36 in which a minimum spatial extension of 5% of the Mediterranean basin was applied to consider an extreme SST event as a MHW29. On each MHW day, any MHW point must belong to a group of contiguous points of a minimum extension of at least 5% of the study area with an overlap with the previous days to cope with the spatiotemporal evolution of the MHW. Additionally, two MHWs separated by 2 days or less are considered the same event.

The AHW definition used in this study is based on that of the Spanish MetService (AEMET). An AHW is an event in which, for at least three consecutive days, the daily maximum 2-m air temperature (Tmax) is above its 95th daily percentile. Following the methodology developed by Pastor et al.36 to detect AHW in the Mediterranean basin, we apply two additional considerations. First, each AHW day has to occupy at least 5% of the Mediterranean Basin to be considered an AHW day. Second, two AHW separated by one day are considered the same event.

The reference for the daily percentile for AHWs and MHWs is the period from 1961 to 1990, following the WMO recommendation for long-term climate change assessments68, for analyses of the changes from 1950 to the present. This baseline was tested for AHW and MHW analysis in the Mediterranean concurrent HW, defined as the spatiotemporal co-occurrence of MHW and AHW for at least three consecutive days36, which coincides with the minimum duration of AHW.

The AHW and MHW definitions described in the previous paragraphs are applied to SST and T2m data to obtain a spatiotemporal tracking of MHWs and AHWs, respectively. Thereafter, the daily concurrent areas over the Mediterranean Sea are identified following the above-mentioned concurrence definition. The consecutive days that were identified as concurrent days had at least 75% of their area overlapping in most of the cases, ensuring spatial coherence36. In the subsequent analysis, for each MHW, the spatial points that are concurrent at any time of that MHW duration are named concurrent points.

The present analysis is based on the MHW catalogue described in Pastor et al.36, which is a list of the 169 identified MHW events in the extended summers (May–September) from 1940 to 2022. We restrict the period of analysis to the extended summer69,70 because, during the warm season, SST is higher54 and therefore, the ecological impacts of MHWs are presumably larger. We use an extended summer version of that MHW catalogue, restricting the yearly period from May to September. We split MHWs that persisted for longer than one extended summer into shorter events occurring within a single extended summer period. The updated catalogue includes a total of 173 MHWs, among which 108 are identified as concurrent with AHWs. A MHW is classified as concurrent if it satisfies the criteria for concurrence for a minimum of 3 days, regardless of whether it is not concurrent during its entire duration. For the subsequent analysis shown in the next sections, we focus exclusively on the concurrent points of the 108 MHWs that were found to be concurrent.

The analysed MHWs from our catalogue are described in a three-dimensional array of consecutive daily maps from which we track the MHW daily evolution and identify the daily concurrent areas. Figure 8 shows an example of concurrent AHW and MHW identified on May 1st, 2003, with the concurrent and non-concurrent areas identified.

MHW intensity and heat fluxes during concurrent stages

For all the concurrent MHW events, we analyse MHW intensity, the total heat flux balance Qnet and its components in the air-sea interface, namely LWRnet, SWRnet, LH and SH, on all the concurrent points in the Mediterranean in the May to September period from 1940 to 2022. The first step in heat flux analysis is the evaluation of the total heat flux balance Qnet and its components on five periods consisting of three phases of AHW-MHW concurrence: the five prior days to concurrence onset (before-concurrence phase), the concurrent days (concurrence phase) and the 5 days after concurrence end (after-concurrence phase); and two other periods: days without an MHW (no MHW) and the other non-concurrent days that are not in the phases before/after-concurrence (non-concurrent MHW). For each concurrent point of the MHW, we compute the mean heat flux on each period. Thereafter, we compute the mean of all concurrent points for each MHW and represent it on boxplots. Sensitivity tests with different lengths of the before/after-concurrence phases from one up to 10 days have been run, presenting minor differences in the results. Based on these tests, we use a length of 5 days for the before/after-concurrence phases because the major changes were observed during the first five previous/posterior days to concurrence onset/end.

As MHWs have different durations, and on each grid point, concurrence may start and last for different times, it is difficult to compare different full concurrent MHW events. To cope with this difficulty, we systematically examine the onset and the end of concurrence on each point as follows. The subsequent analysis is conducted individually for the MHW intensity, for the total heat flux balance and for its components. On concurrent MHWs, we analyse how the MHW intensity/heat flux changes at the onset and end of its concurrence with AHWs. We focus on two pivotal moments: the transition from non-concurrent to concurrent conditions (T1, Fig. 9 left) and the transition from concurrent to non-concurrent conditions (T2, Fig. 9 right).

Daily evolution of atmospheric (purple, AHW), marine (light blue, MHW) and concurrence (dark blue) occurrence with time denoted on the horizontal axis. On the left, the transition from non-concurrent to concurrent conditions (T1), where time equal to zero is set on the first day of concurrence. On the right, the transition from concurrent to non-concurrent conditions (T2), where time equal to zero is set to the last day of concurrence.

For each concurrent MHW point (i.e. the points that are concurrent at some time of the MHW duration), we generate two daily time series of the analysed variable, one for transition T1 and another for transition T2, respectively (Fig. 9). For the T1 time series, we assign day 0 to the first day with concurrence and extend that time series 5 days before and after day 0. Similarly, for the T2 time series, we assign day 0 to the last day with concurrence and extend that time series 5 days before and after day 0.

At this point, we have two time series for each of the concurrent points of the 108 concurrent MHWs. Both time series are stored in two matrices, where the columns are the days and the rows are each time series. We calculate the probability distribution, mean and standard deviation of the analysed variable on each column of the matrix. In our analysis, the probability distribution of the analysed variable represents the percentage of concurrent points with a given value.

Considering that the largest variations around concurrence onset or end are observed on the LH flux, a deeper detailed analysis is run for the LH flux. As our results show that the largest change on the LH flux is observed around day 0, specifically between the day before and after the concurrence onset and end, we examine its variation on that interval, which in the following is named “interest interval” on T1 or T2 as follows:

-

For each concurrent point, and independently for the interest interval on T1 and for the interest interval on T2, we compute the difference in the LH flux in the interest interval as the LH flux on day 1 (the next day after concurrence onset in the case of T1, and the first day after concurrence end in the case of T2) minus the LH heat flux on day −1 (the day before the concurrence onset in the case of T1, and the penultimate concurrent day in the case of T2).

-

Then we compute the mean of that difference over all the concurrent points.

We examine the long-term trend of the above-mentioned LH flux change in the interest interval on T2 as follows. We compute the mean LH flux difference in the interest interval, considering 30-year consecutive subperiods starting at 1940 and until the period 1993 to 2022, obtaining a mean difference for each sub-period. We only show this analysis for the T2 interest interval because of its bigger magnitude with respect to T1.

The next analysis step consists of computing the probability distributions of the LH flux changes on the interest interval on T1 and T2, independently for each MHW and considering its concurrent points. Thereafter, we compute the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of these probability distributions to quantify the MHW concurrent area displaying an LH emission decrease in T1 and an increase on T2. The CDF is the percentage of concurrent points whose LH flux difference in the interest interval is more positive, in the case of T1, or more negative, in the case of T2, than or equal to a given value.

Then we evaluate if there is a relationship between the MHW intensity and the LH change in the interest interval on T2. We calculate the Pearson correlation for each MHW using the MHW intensity-LH pairs of its concurrent area, and the corresponding p-value obtained from the student’s t-distribution.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

ERA5 data has been obtained from Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). ERA5: Fifth generation of ECMWF atmospheric reanalyses of the global climate. Copernicus Climate Change Service Climate Data Store (CDS), https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=overview (accessed on 15 March 2023).

Code availability

The code used for this study is available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

IPCC. Synthesis Report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). Diriba Korecha Dadi (2023).

Vogel, M. M., Zscheischler, J., Wartenburger, R., Dee, D. & Seneviratne, S. I. Concurrent 2018 hot extremes across Northern hemisphere due to human-induced climate change. Earths Future 7, 692–703 (2019).

Merchant, C. J., Allan, R. P. & Embury, O. Quantifying the acceleration of multidecadal global sea surface warming driven by Earth’s energy imbalance. Environ. Res. Lett. 20, 024037 (2025).

Cheng, L. et al. Past and future ocean warming. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 776–794 (2022).

Cheng, L. et al. New record ocean temperatures and related climate indicators in 2023. Adv. Atmos. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-024-3378-5 (2024).

Plecha, S. M. & Soares, P. M. M. Global marine heatwave events using the new CMIP6 multi-model ensemble: from shortcomings in present climate to future projections. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 124058 (2019).

Darmaraki, S. et al. Future evolution of marine heatwaves in the Mediterranean Sea. Clim. Dyn. 53, 1371–1392 (2019).

Frölicher, T. L. & Laufkötter, C. Emerging risks from marine heat waves. Nat. Commun. 9, 650 (2018).

Laufkötter, C., Zscheischler, J. & Frölicher, T. L. High-Impact Marine Heatwaves Attributable to Human-Induced Global Warming. http://science.sciencemag.org/.

Smith, K. E. et al. Socioeconomic impacts of marine heatwaves: global issues and opportunities. Science 374, eabj3593 (2021).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Projected marine heatwaves in the 21st century and the potential for ecological impact. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 734 (2019).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cross-chapter Paper 4: Mediterranean Region. In Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability 2233–2272 (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Tuel, A. & Eltahir, E. A. B. Why is the Mediterranean a climate change hot spot? J. Clim. 33, 5829–5843 (2020).

Zittis, G., Hadjinicolaou, P., Klangidou, M., Proestos, Y. & Lelieveld, J. A multi-model, multi-scenario, and multi-domain analysis of regional climate projections for the Mediterranean. Reg. Environ. Change 19, 2621–2635 (2019).

Urdiales-Flores, D. et al. A global analysis of historical and future changes in Mediterranean climate-type regions. Int. J. Climatol. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.8655 (2024).

Zittis, G. et al. Climate change and weather extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Rev. Geophys. 60, 3 (2022).

Pastor, F., Valiente, J. A. & Khodayar, S. A warming Mediterranean: 38 years of increasing sea surface temperature. Remote Sens. 12, 2687 (2020).

Pisano, A. et al. New evidence of Mediterranean climate change and variability from sea surface temperature observations. Remote Sens. 12, 132 (2020).

Garrabou, J. et al. Mass mortality in Northwestern Mediterranean rocky benthic communities: effects of the 2003 heat wave. Glob. Change Biol. 15, 1090–1103 (2009).

Estaque, T. et al. Marine heatwaves on the rise: one of the strongest ever observed mass mortality event in temperate gorgonians. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 6159–6162 (2023).

Garrabou, J. et al. Marine heatwaves drive recurrent mass mortalities in the Mediterranean Sea. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 5708–5725 (2022).

Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M. et al. The burden of heat-related mortality attributable to recent human-induced climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 492–500 (2021).

Naumann, G. et al. Global Warming and Human Impacts of Heat and Cold Extremes in the EU – JRC PESETA IV Project - Task 11 (Publications Office, 2020).

Papadaskalopoulou, C. et al. Assessment of total climate change impacts on the agricultural sector of Cyprus. Atmosphere 11, 608 (2020).

Cramer, W. et al. Climate change and interconnected risks to sustainable development in the Mediterranean. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 972–980 (2018).

Konsta, K., Doxa, A., Katsanevakis, S. & Mazaris, A. D. Projected marine heatwaves over the Mediterranean Sea and the network of marine protected areas: a three-dimensional assessment. Clim. Change 178, 17 (2025).

Juza, M., Fernández-Mora, A. & Tintoré, J. Sub-regional marine heat waves in the Mediterranean Sea from observations: long-term surface changes, sub-surface and coastal responses. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 785771 (2022).

Martínez, J. et al. Evolution of marine heatwaves in warming seas: the Mediterranean Sea case study. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1193164 (2023).

Pastor, F. & Khodayar, S. Marine heat waves: characterizing a major climate impact in the Mediterranean. Sci. Total Environ. 861, 160621 (2023).

Simon, A. et al. Hot and cold marine extreme events in the Mediterranean over the period. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 1982–2021 (2022).

Trigo, R. M. et al. The outstanding European and Mediterranean heatwave activity during summer 2022. Atmos. Res. 323, 108195 (2025).

Zscheischler, J. et al. Future climate risk from compound events. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 469–477 (2018).

Zscheischler, J. et al. A typology of compound weather and climate events. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 333–347 (2020).

Biess, B., Gudmundsson, L., Windisch, M. G. & Seneviratne, S. I. Future changes in spatially compounding hot, wet or dry events and their implications for the world’s breadbasket regions. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 064011 (2024).

Zhou, M. & Wang, S. The risk of concurrent heatwaves and extreme sea levels along the global coastline is increasing. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 144 (2024).

Pastor, F., Paredes-Fortuny, L. & Khodayar, S. Mediterranean marine heatwaves intensify in the presence of concurrent atmospheric heatwaves. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 797 (2024).

Pathmeswaran, C., Sen Gupta, A., Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. E. & Hart, M. A. Exploring potential links between co-occurring coastal terrestrial and marine heatwaves in Australia. Front. Clim. 4, 792730 (2022).

Santos, R., Russo, A. & Gouveia, C. M. Co-occurrence of marine and atmospheric heatwaves with drought conditions and fire activity in the Mediterranean region. Sci. Rep. 14, 19233 (2024).

Santos, R., Russo, A. & Gouveia, C. M. Concurrent marine and atmospheric heatwaves and droughts and their influence on fire activity in the Mediterranean Region. In Advances in Meteorology and Geophysics 2023 (eds. Pereira, M. G., Oliveira, R., Navarro, P. & Bugalho, L.) (Portuguese Association of Meteorology and Geophysics, 2023).

Le Grix, N., Zscheischler, J., Laufkötter, C., Rousseaux, C. S. & Frölicher, T. L. Compound high-temperature and low-chlorophyll extremes in the ocean over the satellite period. Biogeosciences 18, 2119–2137 (2021).

Burger, F. A., Terhaar, J. & Frölicher, T. L. Compound marine heatwaves and ocean acidity extremes. Nat Commun 13, 4722 (2022).

Rodrigues, R. R., Taschetto, A. S., Sen Gupta, A. & Foltz, G. R. Common cause for severe droughts in South America and marine heatwaves in the South Atlantic. Nat. Geosci. 12, 620–626 (2019).

Aghakouchak, A. et al. Climate extremes and compound hazards in a warming world. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 48, 519–567 (2020).

Aboelkhair, H., Mohamed, B., Morsy, M. & Nagy, H. Co-occurrence of atmospheric and oceanic heatwaves in the Eastern Mediterranean over the last four decades. Remote Sens. 15, 1841 (2023).

Zschenderlein, P., Fink, A. H., Pfahl, S. & Wernli, H. Processes determining heat waves across different European climates. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 145, 2973–2989 (2019).

Capotondi, A. et al. A global overview of marine heatwaves in a changing climate. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 701 (2024).

Cronin, M. F. et al. Air-sea fluxes with a focus on heat and momentum. Front. Mar. Sci. 6 (2019).

Yu, L. & Weller, R. A. Objectively analyzed air-sea heat fluxes for the global ice- free oceans (1981-2005). Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 88, 527–539 (2007).

Hirata, H., Kawamura, R., Nonaka, M. & Tsuboki, K. Significant impact of heat supply from the gulf stream on a “Superbomb” cyclone in January 2018. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 7718–7725 (2019).

Reeder, M. J., Spengler, T. & Spensberger, C. The effect of sea surface temperature fronts on atmospheric frontogenesis. J. Atmos. Sci. 76, 1753–1771 (2021).

Parfitt, R. Air-sea heat and moisture flux gradients. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110728 (2024).

Denaxa, D., Korres, G., Bonino, G., Masina, S. & Hatzaki, M. The role of air–sea heat flux for marine heatwaves in the Mediterranean Sea. https://sp.copernicus.org/articles/4-osr8/11/2024/https://doi.org/10.5194/sp-4-osr8-11-2024 (2024).

Simon, A., Pires, C., Frölicher, T. L. & Russo, A. Long-term warming and interannual variability contributions’ to marine heatwaves in the Mediterranean. Weather Clim. Extrem. 42, 100619 (2023).

Sen Gupta, A. et al. Drivers and impacts of the most extreme marine heatwaves events. Sci. Rep. 10, 19359 (2020).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Marine heatwaves. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-032720 (2021).

Marin, M., Feng, M., Phillips, H. E. & Bindoff, N. L. A. Global, multiproduct analysis of coastal marine heatwaves: distribution, characteristics, and long-term trends. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 126, e2020JC016708 (2021).

Guinaldo, T., Voldoire, A., Waldman, R., Saux Picart, S. & Roquet, H. Response of the sea surface temperature to heatwaves during the France 2022 meteorological summer. Ocean Sci. 19, 629–647 (2023).

Jacox, M. G. et al. Global seasonal forecasts of marine heatwaves. Nature 604, 486–490 (2022).

McAdam, R., Masina, S. & Gualdi, S. Seasonal forecasting of subsurface marine heatwaves. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 225 (2023).

De Boisséson, E. & Balmaseda, M. A. Predictability of marine heatwaves: assessment based on the ECMWF seasonal forecast system. Ocean Sci. 20, 265–278 (2024).

McAdam, R., Bonino, G., Clementi, E. & Masina, S. Forecasting the Mediterranean Sea marine heatwave of summer 2022. State Planet 14, 1–10 (2024).

Jung, T., Ferranti, L. & Tompkins, A. M. Response to the summer of 2003 Mediterranean SST anomalies over Europe and Africa. J. Clim. 19, 5439–5454 (2006).

Vogt, L., Burger, F. A., Griffies, S. M. & Frölicher, T. L. Local drivers of marine heatwaves: a global analysis with an earth system model. Front. Clim. 4, 847995 (2022).

Darmaraki, S., Krokos, G., Genevier, L., Hoteit, I. & Raitsos, D. E. Drivers of marine heatwaves in coral bleaching regions of the Red Sea. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 120 (2025).

Luo, B. & Minnett, P. J. Evaluation of the ERA5 sea surface skin temperature with remotely-sensed shipborne marine-atmospheric emitted radiance interferometer data. Remote Sens. 12, 1873 (2020).

Yao, L., Lu, J., Xia, X., Jing, W. & Liu, Y. Evaluation of the ERA5 sea surface temperature around the Pacific and the Atlantic. IEEE Access 9, 12067–12073 (2021).

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 227–238 (2016).

WMO. WMO Guidelines on the Calculation of Climate Normals (WMO-No.1203). Geneva: World Meteorological Organization. ISBN 978‑92‑63‑11203‑3

Peña-Ortiz, C., Barriopedro, D. & García-Herrera, R. Multidecadal variability of the summer length in Europe*. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14.

Park, B. J., Kim, Y. H., Min, S. K. & Lim, E. P. Anthropogenic and natural contributions to the lengthening of the summer season in the Northern Hemisphere. J. Clim. 31, 6803–6819 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The work presented was funded by the research project EVER_PROMETEO (CIPROM/2022/37) funded by the Generalitat Valenciana. The contribution of Laura Paredes-Fortuny was supported by the program Generació Talent of Generalitat Valenciana (CIDEGENT/2018/017). The Mediterranean Centre for Environmental Studies (CEAM) is partly supported by Generalitat Valenciana.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceived the study, contributed to the analysis, discussion, manuscript writing and reviewing. L.P.F. was responsible of first drafting the results section and developing the code for data analysis and heatwave detection. L.P.F. and F.P. performed data curation and visualisation. S.K. coordinated the investigation, funding acquisition and project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Sreelekha Jarugula and Alice Drinkwater. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paredes-Fortuny, L., Pastor, F. & Khodayar, S. Concurrent atmospheric heatwaves intensify marine heatwaves through air-sea heat flux change in the Mediterranean Sea. Commun Earth Environ 6, 638 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02633-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02633-2

This article is cited by

-

Compound coastal marine–terrestrial heatwaves associated with humid-heat stress in Europe

Scientific Reports (2025)