Abstract

Despite high confidence in the intensification of the hydrological cycle due to global warming, the future spatiotemporal patterns of extreme precipitation remain uncertain. Here we explore how climate change influences the seasonal timing of extreme precipitation events, using daily output from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6. We show that at latitudes between about 45°N and 75°N in Eurasia and North America, where extreme precipitation typically peaks in summer, climate models project a substantial shift in the seasonal timing of extreme precipitation from summer into the colder seasons, spring and autumn, or even into winter, by the late 21st century. We show that this shift is associated with reduced moisture supply during strong updraft events in summer. These results point towards a need for improved representations of processes determining the change in the moisture availability and simulated vertical winds of the atmosphere as well as for adaptation to higher flood risk in colder seasons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extreme precipitation events have increased across many regions of the globe due to climate change1,2,3,4,5,6,7, and are projected to become more frequent and intense in the future1,5,8,9,10. These changes are primarily driven by the increased capacity of a warmer atmosphere to hold and transport moisture, thus allowing for enhanced precipitation extremes1,11,12. Beyond annual trends, observational studies confirm widespread increases in the seasonal frequency of daily extreme precipitation events across large parts of the contiguous USA13,14. Similarly, regional climate models project more frequent extreme precipitation events across all seasons, particularly over Northern Hemisphere land regions except for some arid areas. Notably, the strongest increases are projected for autumn and winter in the extratropics and high latitudes in response to global warming15,16,17. These findings raise a key question: Does a warming climate alter the seasonal timing of extremes, rather than causing a uniform intensification throughout the entire seasonal cycle?

While many studies have focused on the changes in the intensity and frequency of extreme precipitation, an important but less explored aspect is the shifts in the seasonal timing of extremes. Extremes occurring outside today’s peak heavy rainfall season may alter flood regimes and exacerbate hydrological hazards, including debris flows and soil erosion18,19. Additionally, shifts in extreme precipitation events to colder seasons, coupled with warming-induced snowmelt runoff, could increase the risk of more severe winter and spring floods20. Seasonal shifts in extremes also have strong implications for agriculture and terrestrial ecosystems18,21. For instance, as crop vulnerability varies throughout the year, precipitation extremes of similar magnitude can cause disproportionately high damage when occurring during planting or harvest seasons. Therefore, understanding the future timing of extremes is crucial for infrastructure planning and long-term mitigation strategies.

Recent observational studies indicate that the seasonal patterns of daily extreme precipitation events are already shifting, with statistical analyses detecting changes in their timing14,22,23,24. However, trends vary widely across datasets and regions. Significant shifts of extremes to spring have been observed at some stations, but no spatially consistent changes have been detected across the contiguous USA14,22. At broader scales, extratropical regions exhibit modest clustering of extremes, while global-scale analyses reveal little change in average timing23,24. Nevertheless, future projections suggest that shifts in the average seasonality of extremes may become more pronounced under high-emission scenarios, though these changes are expected to remain regionally heterogeneous24.

Despite growing evidence of changes in the timing of future extremes, to our knowledge, there is no rigorous inter-model assessment at the global scale beyond shifts in the average seasonality24. We aim to bridge this gap by evaluating the projected changes in the seasonal timing of extreme precipitation events using a large ensemble of global models. Additionally, we investigate the underlying mechanisms driving inter-model differences, providing new insights into model development and emergent constraints for improving long-term climate projections.

Extreme precipitation shifts to colder seasons

We evaluate the mean timing of extremes in global climate models from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6), computed as the mean Day of Year (DoY) when precipitation extremes occur (see “Methods”), i.e., the days when the historical all-day 98th percentile is exceeded (Fig.1). We find that CMIP6 models generally agree with the spatial pattern of the mean timing in the historical period covered by the observational rainfall estimates on a gridded network (REGEN25, Fig. 2a, b). Furthermore, there is good agreement on the duration of the “heavy rainfall season”, which here refers to the part of a seasonal cycle covered by one standard deviation (±1σ) of the DoY spread around the mean (Figs. 1 and 2c, d). Even though capturing the exact mean timing of extremes and the duration of the heavy rainfall season is challenging, the agreement between the spatial patterns of individual models and REGEN is good, with spatial correlation exceeding 0.5 and 0.6, respectively, in more than 80% models. The spatial correlation is even higher between the multi-model mean and observations (0.66 for mean timing and 0.76 for the duration of the heavy rainfall season) as internal uncertainties partially cancel out. The largest biases are found in subtropical to mid-latitude regions such as central America, Central Eurasia, and Northern Africa (Fig. 2e, f). This is partially due to mismatches in the transition zones of seasonal extremes (mean-summer/winter extremes) between models and REGEN observations, and a tendency of models to overestimate the duration of the heavy rainfall season. This overestimation likely reflects limitations in convective parameterizations and the representation of small-scale processes, such as mesoscale convective systems. Our results are broadly consistent with previous studies showing that climate models can reproduce the historical seasonality of precipitation extremes relatively well, thus providing insights into future real-world changes and the underlying processes23,24,26,27,28.

Dots and rose diagrams represent the Day of Year (DoY) and monthly distribution, respectively, of extreme precipitation events in the historical period (1950–1999, in blue) and the future period (2050–2099 under scenario SSP5-8.5, in red) for a specific grid cell (34.7°E, 56.9°N) from the HadGEM3-GC31-LL r1i1p1f3 simulation. The mean timing of extremes and the duration of the heavy rainfall season are depicted with dashed and solid lines with arrows, respectively.

The mean timing of historical extreme precipitation events in a CMIP6 multi-model mean and b REGEN observational data. Duration of the historical heavy rainfall season (in number of days) in c CMIP6 multi-model mean and d REGEN observational data. Differences between CMIP6 multi-model mean and REGEN observational data in e the historical mean timing of extremes and f the historical duration of the heavy rainfall season (in number of days).

Given the reasonable reproduction of spatial patterns in the seasonal timing of extreme precipitation events, CMIP6 models are considered informative for projecting future conditions (Figs. 2 and 3). Consistent with the previous study based on CMIP524, there are no coherent large-scale changes in the mean timing of extremes in CMIP6 and patterns are quite variable in space (Fig. 3a). However, we find a significant extension of the heavy rainfall season at latitudes between about 45°N and 75°N in Eurasia and North America, as indicated by all 37 CMIP6 models (Fig. 3b). These regions typically experience a summer peak of extreme precipitation in today’s climate, and the mean timing does not change much in the future23 (Figs. 2a, b and 3a). This implies that future extremes shift from summer more often into the shoulder seasons of spring and autumn, or even into winter. Here, this is expressed as a reduction in the summer (June–August, JJA) fraction of extreme precipitation events (Fig. 3c). The most pronounced and robust change occurs in central Eurasia (marked with a yellow box in Fig. 3b), where the future heavy rainfall season is projected to extend by nearly 60 days. In this region, 90% of the precipitation extremes in today’s climate occur between late March and mid-November, in the future the corresponding period is projected to extend from mid-February to early December. This result remains robust whether events are defined using the 95th, 99th percentiles, or alternatively using Rx1day (Fig. S1). It also holds if the extremes are defined as exceedances of the respective historical and future 98th percentiles, and not only the historical percentile (Fig. S1d).

Future changes in a the mean timing of extremes and b the duration of the heavy rainfall season (in number of days). Future changes in c the summer (June–August, JJA) fraction of the number of extremes and d relative humidity at 850 hPa during strong updraft events in JJA (in %). Stippling indicates regions where more than 80% of models agree on the sign of changes. The case study region marked with a yellow box in (b) is used for the analysis of relative humidity and updrafts.

Understanding model differences

In the following, we analyze this pronounced extension of the heavy precipitation season into spring and autumn over the selected region as a case study to discuss potential mechanisms, before drawing conclusions about hemispheric signals. The grid cells within the case study region exhibit coherent seasonality of extreme precipitation events and are typically associated with similar synoptic-scale circulation features such as extratropical cyclones and cold fronts29,30, making them suitable for a more detailed regional analysis.

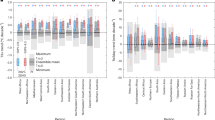

Models consistently project a future extension of the heavy rainfall season into the colder seasons, although the magnitude of this extension varies across models (Fig. S3). Notably, not all models reproduce the single summer peak of extreme precipitation observed in REGEN. Some instead show a bimodal distribution of extremes even in historical climate (Fig. 4). These differences are discussed in the next section, where we examine the underlying physical mechanisms. Despite substantial uncertainties in the magnitude of projected seasonal shifts, model projections tend to cluster by family (Fig. 4). For instance, UKESM1, HadGEM3, and ACCESS project a reduced number of summer extremes in the future, with an average decrease of about 19 percentage points in the fraction of extremes occurring during JJA. EC-Earth models (EC-EARTH, EC-EARTH-Veg, EC-EARTH-Veg-LR, EC-EARTH-CC), on the other hand, indicate a reduction in the JJA fraction by less than 10 percentage points, even though the absolute number of future summer extremes increases. The regional analysis focusing on the DoY distribution highlights a reduction in the JJA fraction of extremes, which leads to extended heavy rainfall seasons in the future. To investigate the complexity of seasonal shifts across models, it is necessary to focus on JJA precipitation extremes and the synoptic drivers behind these projected changes.

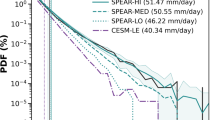

Results are shown for grid cells in the case study region of Fig. 3b. Boxplots show the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles of the distributions. Percentages refer to the JJA fraction of extremes, represented between the vertical dashed lines, in the historical (in blue) and future (in red) periods. The areas under the future distribution curves exceed 100%, as more events occur above the historical percentile. From family a to f, models project a less pronounced reduction in the JJA fraction of precipitation extremes. The panel with light blue shading on the top right shows the historical distribution based on REGEN observations. Characteristic models of each family, marked by gray shading, are used for the analysis of relative humidity and updrafts in Fig. 5.

It turns out that the subsets of models that show similar behavior in the DoY distribution of extreme precipitation events correspond closely to established climate model genealogies identified in the literature31,32. Models within the same family show consistent DoY distributions in both historical and future periods, while the most pronounced differences occur between families (Fig. 4). This is particularly interesting, as it highlights how structural differences across model families govern the representation of precipitation extremes, especially their seasonal timing and projected future changes. In the following section, we explore the underlying physical mechanisms driving these inter-model differences.

Understanding the physical mechanisms

Moisture supply during strong updraft events is critical because both sufficient atmospheric moisture and upward vertical motion are necessary to reach saturation and condensate enough precipitable water and ultimately generate extreme precipitation12. While atmospheric warming increases the potential for heavier precipitation through enhanced water-holding capacity (i.e., Clausius-Clapeyron relation), the actual intensity of extremes depends on how much moisture can be lifted and reaches saturation during the time and location of strong updrafts. By examining relative humidity during strong updraft days, we evaluate how this joint condition, that is, moisture availability coupled with updrafts, is represented across models. This approach is supported by a recent study using convection-resolving models, which emphasizes the importance of boundary-layer relative humidity in modulating updraft strength and precipitation efficiency that can influence convective precipitation extremes33.

In our analysis, we focus on changes in relative humidity during strong updraft events in JJA at 850 hPa. This level shows the strongest and most spatially coherent correlation with reductions in the JJA fraction of extreme precipitation events, but results are also consistent with relative humidity changes at the surface (Fig. S2). Strong updraft events in JJA are defined as exceedances of the historical all-JJA-day 98th percentile of daily-mean vertical wind at 850 hPa. We hypothesize that these events would produce extreme precipitation if tropospheric humidity were sufficiently large12,34. Under future warming, specific humidity during JJA strong updraft days increases in both mean and spread of its distribution, broadly consistent with the Clausius-Clapeyron relation that the saturation specific humidity of water increases with warming. However, the distribution of relative humidity conditional on these days indicates a robust future drying, the magnitude of which is highly model-dependent (Fig. S4).

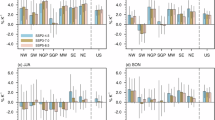

The HadGEM3 model, one of the models with the strongest fractional reduction in JJA extremes, projects that the fraction of strong updraft days with relative humidity higher than 90% (nearly saturated wet days) will reduce by more than 30 percentage points in the future (from 41% to 11%, Fig. 5). The MPI-LR model on the other hand suggests a weaker drying, with nearly saturated wet days decreasing from 72% to about 54% yet showing a minimal change in the median of the distribution (Fig. 5). The inter-model differences in changes of relative humidity conditional on strong updraft days in JJA can explain the varying changes of the JJA fraction of extremes across model families. Models with strong drying of the tropospheric air during updraft days show a pronounced reduction in the JJA fraction of extreme precipitation, whereas models with weak drying and generally high humidity during updraft days show little decrease in the JJA fraction of extremes (Figs. 4 and 5). We compare the frequency of strong updraft events during JJA and find that some models project fewer high-percentile updrafts in the future (Fig. S5). However, this does not explain the inter-model differences in the projected shifts of precipitation extremes. The decrease in strong updrafts could result from a generally more stable atmosphere with future warming.

Results are shown for grid cells in the case study region of Fig. 3b and for the characteristic models HadGEM3-GC31-LL, INM-CM4-8, NorESM2-MM, CNRM-CM6-1-HR, and MPI-ESM1-2-LR marked by gray shading in Fig. 4. Boxplots below show the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles of the distributions. Note the different y-axis for MPI-ESM1-2-LR.

We test this link between drying during updraft days and change in JJA fraction of extreme precipitation over central Eurasia more systematically across 17 CMIP6 models that provide daily data of relative humidity and vertical wind (Fig. 6a). We find a remarkably robust correlation exceeding 0.83, suggesting that the different changes in the JJA fraction of future extremes are directly related to the projected changes in relative humidity over the selected Eurasian region. The MPI family (MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MPI-ESM1-2-LR, and NESM3) projects a decrease by 7–12 percentage points in the JJA fraction of extremes and a less than 10 percentage points reduction in the median of relative humidity on days with strong updrafts in JJA. On the other hand, UKESM1, HadGEM3, and ACCESS suggest a more pronounced reduction, with decreases exceeding 15 percentage points in the JJA fraction of extremes and more than 30 percentage points in the median of relative humidity. Again, we observe clusters of models in each family and large inter-family spread along the relationship (Fig. 6a).

In addition to explaining projected shifts of extremes, seasonal relative humidity patterns help account for the bimodality found in some models’ present-day distributions (Fig. 4). For instance, models such as FGOALS-g3, INM-CM4-8, and INM-CM5-0 show a persistent bimodal structure, which can be primarily attributed to a pronounced dry bias in relative humidity during JJA that limits the occurrence of summer extremes (Figs. 4 and S6). In models like INM-CM4-8 and INM-CM5-0, the relative humidity climatology shows a sharp drop in late August, aligning with a local minimum in extreme event frequency. This relationship between the seasonal relative humidity pattern and the DoY structure is consistent across time and space within each model individually and becomes more evident in future projections. Under warming, enhanced JJA drying suppresses summer extremes, while spring and autumn events become more frequent, together contributing to the emergence or amplification of bimodal structures in the future. Although inter-model variability exists, partly due to adjustments of stronger vertical motion in drier models, relative humidity patterns strongly shape the seasonal distribution of extremes and their projected changes in each model.

Quantifying changes at global scale

Finally, we test whether the above relationship also holds across other regions of the globe. Multi-model mean changes in the fractional extremes in JJA and the median of relative humidity on JJA days with strong updraft events at 850 hPa show consistent reduction over Eurasia and central North America (Fig. 3c, d), with the magnitude of which covariant across models (Figs. S7 and S8). To test the relevance of drying, we calculate the same correlation as in Fig. 6a for the entire globe using 3° × 3° latitude-longitude grid boxes (7200 total). We find that the strong relation between changes in the JJA fraction of extremes and the median of relative humidity during strong updraft days holds across most land regions between about 45°N and 75°N (Fig. 6b). A particularly high correlation (above 0.8) is found over northern Eurasia, eastern Canada and the western Mediterranean. Unlike the former two regions that are characterized by more pronounced JJA extremes and an extended heavy rainfall season in the future, precipitation extremes over the Mediterranean occur mainly in winter in the historical period. Hence, in this region the already low JJA fraction of extreme events is projected to further decrease due to even drier summers in the future, leading to a future decrease in the duration of the heavy rainfall season (Fig. 3b). As seen in central Eurasia, we observe similar patterns in the seasonality of extremes and moisture conditions in JJA within groups of models over the yellow box region in eastern Canada in Fig. S11b (Figs. S9 and S10). A consistent and even more robust signal (a correlation coefficient reaching 0.92) is found when aggregating over the yellow box region, which supports the universality of the analysis (Fig. S11a). This correlation is slightly stronger than at the 3° × 3° grid-box level, likely due to spatial aggregation over a larger region that helps to further reduce the internal variability35.

Our results are consistent with recent smaller-scale studies using regional and convection-permitting models that have pointed out a less distinct future summer peak in the frequency of sub-daily to daily extreme events over Central US Plains, northeastern North America, and Northern Europe, where in the past extreme precipitation predominantly occurred in summer16,27,28. Furthermore, our findings are in line with previous studies indicating that thermodynamic processes, in particular the limited moisture supply, can explain the projected changes in the seasonality at high latitudes16,24. Recent work has applied a physical scaling to separately decompose summer and winter precipitation extremes, and further shows that the changes in summer extremes over the Northern Hemisphere extratropical land is correlated with decreases in near-surface relative humidity in summer, which, in their diagnostic, shows up as a negative dynamic contribution34.

Conclusions

Unlike the variable spatial patterns of changes in the mean timing of extremes, we find a significant and robust extension of the heavy rainfall season in the Northern Hemisphere’s high latitudes, except for some dry areas and the oceans, across CMIP6 models (Fig. 3a, b). Conversely, mid-latitude areas characterized by cold-season extremes, such as the western Mediterranean, are projected to experience a shorter heavy rainfall season with a more concentrated winter-peak distribution in the future.

Our analysis, conditional on the occurrence of strong updrafts, indicates that the projected reduction in the JJA fraction of extremes is largely driven by future decreases in low-level relative humidity during JJA days with strong updrafts. The relationship remains robust across 17 models over most land regions at latitudes between about 45°N and 75°N. This drying during strong updrafts is consistent with the general tendency of mid-to-high latitudes to experience pronounced future decreases in relative humidity, which relates to the land-sea contrast of the surface energy budget and moisture availability in the warm season36,37,38. Additional reasons may be that, with future warming, favorable conditions for warm-season extreme precipitation events are likely to occur more evenly throughout the year when temperatures exceed a certain threshold39.

The shifts in the seasonal timing suggest that more complex mechanisms are involved beyond basic thermodynamic feedback leading to an overall intensification of extreme precipitation15. They thus help explaining why the thermodynamic contribution to the intensification of precipitation extremes is below the Clausius–Clapeyron value over these regions: due to the shift towards colder seasons, the associated warming on the day of the events is smaller than it would be if the future extremes were to occur on about the same day of the year as in the past. As a result, the intensification of extremes is lower than expected compared to what would be projected based solely on mean warming. This is consistent with a previous study40, in which smaller increases in vertically integrated saturation specific humidity, conditioned on the occurrence of precipitation extremes, were found compared to the annual mean over some northern extratropical regions. The results presented here refer to the very-high-emission scenario SSP5-8.5 and the second half of the 21st century, but qualitatively similar, albeit smaller changes are obtained for lower emission scenarios and lower warming levels. However, it should be noted that our study is limited by the coarse CMIP6 model resolution and related uncertainties associated with the parameterization of moist convection.

The CMIP6 multi-model ensemble provides clear evidence for seasonal shifts in extremes, but narrowing uncertainties through improved models and observational constraints is crucial for providing more robust climate information for adaptation decisions. Future research will benefit from examining the presented relationship in convection-permitting models41. Further investigation is also needed to analyze the changes in the seasonal timing of extremes at different timescales, such as hourly to 5-day extreme precipitation events. In spite of these limitations, the reasonable representation of the seasonality of historical precipitation extremes, as well as the robust and physically plausible link to summer drying increase confidence in our main finding of an extended heavy rainfall season over Northern Hemisphere land regions in a warmer future climate.

Methods

Extreme precipitation in CMIP6 and the REGEN observational data

Climate model outputs from CMIP6 are analyzed, using all models that provide daily accumulated surface precipitation data for the historical period 1950–1999 and future period 2050–2099 under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. These data are available for 37 models, with 16 models providing multiple members of initial-condition ensembles (Table S1). Extreme precipitation events are identified on each model’s original grid for the historical and future periods as exceedances of the all-day 98th percentile of daily accumulated precipitation during all years of the historical period. The DoY on which the extreme events occur is extracted to describe the seasonal timing of extremes and their changes in the future. The mean timing of extremes and standard deviation of the DoY are computed for each period using the R package circular, which accounts for the circular nature of the data. We introduce the concept of the heavy rainfall season, referring to the part of a seasonal cycle covered by one standard deviation (±1σ) of the DoY spread around the mean (in number of days, Fig. 1). All calculations are performed on each model’s original grid, with the resulting fields interpolated to a 1° × 1° latitude-longitude resolution to calculate the multi-model mean. Members of initial-condition ensembles are treated separately, and are first averaged within each model to ensure equal contribution from each model, regardless of the number of ensemble members. To evaluate model performance on the seasonal timing of extremes, observational data from REGEN are used for the period 1950–1999. REGEN provides area-averaged precipitation estimates derived from merged archives of in situ rain gauge data and covers global land areas with a 1° × 1° resolution. The REGEN observational data are processed using the same methodology applied to the model output. For both regional and global analyses, extreme events are first identified independently at each grid cell, and the corresponding DoY values are then pooled across all grid cells within the specified box region prior to constructing the distributions. Model families are first grouped based on similarities in the DoY distributions of extremes over central Eurasia. These preliminary clusters are then validated using established model genealogies31,32. Finally, clusters are refined (either expanded or merged) based on model genealogy.

Synoptic conditions during strong updraft events in JJA

To explore the causes of the reduced JJA fraction of extreme precipitation events and the associated inter-model differences, daily-mean specific humidity, relative humidity, and vertical wind velocity at all available vertical pressure levels are analyzed for the historical and future period under scenario SSP5-8.5. These data are available for 17 models, 4 of which provide multiple members of initial-condition ensembles (Table S2). Characteristic models of each family, marked by gray shading, are selected based on variable availability and the range of projected changes in the JJA fraction of extremes (Fig. 4). Strong updraft events in JJA are identified on each model’s original grid for both periods as days when the daily-mean vertical wind at 850 hPa exceeds the all-JJA-day 98th percentile during all years of the historical period. Specific and relative humidity values are extracted during these strong updraft events to evaluate the synoptic moisture supply. For both regional and global analyses, the corresponding values are pooled across all grid cells within the specified box region prior to constructing distributions. Monthly mean relative humidity at all available vertical pressure levels is also used to evaluate its relationship with changes in the JJA fraction of extremes. In this study, we focus primarily on the 850 hPa pressure level, as it exhibits both the most pronounced decrease in relative humidity during JJA and the strongest correlation with the projected reduction in the JJA fraction of extremes, compared to the 500 hPa, 700 hPa, or surface levels. Changes in median relative humidity during strong updraft events in JJA are used to summarize synoptic moisture conditions and are correlated with model-specific changes in the JJA fraction of precipitation extremes. While the correlation pattern remains broadly consistent, it becomes less robust when using the 25th or 75th percentiles instead of the median. To calculate inter-model correlation at the global scale, data are aggregated on a 3° × 3° latitude-longitude grid to ensure adequate sample size at each location.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available. The CMIP6 output can be assessed via the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) portals, for example, https://esgf-data.dkrz.de/search/cmip6-dkrz/. The REGEN-LONG observational precipitation dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.25914/5ca4c2c6527d242. The processed data used to generate the figures in this study are available at https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-00074583443.

Code availability

The code used to process the data and generate the figures in this study is publicly available at https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-00074583443.

References

Fischer, E. M. & Knutti, R. Observed heavy precipitation increase confirms theory and early models. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 986–991 (2016).

Du, H. et al. Precipitation from persistent extremes is increasing in most regions and globally. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6041–6049 (2019).

Dunn, R. J. et al. Development of an updated global land in situ-based data set of temperature and precipitation extremes: HadEX3. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2019JD032263 (2020).

Sun, Q., Zhang, X., Zwiers, F., Westra, S. & Alexander, L. V. A global, continental, and regional analysis of changes in extreme precipitation. J. Clim. 34, 243–258 (2021).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 1513–1766 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Min, S.-K., Zhang, X., Zwiers, F. W. & Hegerl, G. C. Human contribution to more-intense precipitation extremes. Nature 470, 378–381 (2011).

Zhang, X., Wan, H., Zwiers, F. W., Hegerl, G. C. & Min, S.-K. Attributing intensification of precipitation extremes to human influence. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5252–5257 (2013).

Fischer, E. M. & Knutti, R. Anthropogenic contribution to global occurrence of heavy-precipitation and high-temperature extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 560–564 (2015).

Kharin, V. et al. Risks from climate extremes change differently from 1.5 °C to 2.0 °C depending on rarity. Earths Future 6, 704–715 (2018).

Li, C. et al. Changes in annual extremes of daily temperature and precipitation in CMIP6 models. J. Clim. 34, 3441–3460 (2021).

Allan, R. P. & Soden, B. J. Atmospheric warming and the amplification of precipitation extremes. Science 321, 1481–1484 (2008).

O’Gorman, P. A. & Schneider, T. The physical basis for increases in precipitation extremes in simulations of 21st-century climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 14773–14777 (2009).

Janssen, E., Sriver, R., Wuebbles, D. J. & Kunkel, K. Seasonal and regional variations in extreme precipitation event frequency using CMIP5. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 5385–5393 (2016).

Mallakpour, I. & Villarini, G. Analysis of changes in the magnitude, frequency, and seasonality of heavy precipitation over the contiguous USA. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 130, 345–363 (2017).

Rajczak, J. & Schär, C. Projections of future precipitation extremes over Europe: a multimodel assessment of climate simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 10–773 (2017).

Innocenti, S., Mailhot, A., Leduc, M., Cannon, A. J. & Frigon, A. Projected changes in the probability distributions, seasonality, and spatiotemporal scaling of daily and subdaily extreme precipitation simulated by a 50-member ensemble over northeastern North America. J. Geophys. Res. 124, 10427–10449 (2019).

Cardell, M. F., Amengual, A., Romero, R. & Ramis, C. Future extremes of temperature and precipitation in Europe derived from a combination of dynamical and statistical approaches. Int. J.Climatol. 40, 4800–4827 (2020).

Kundzewicz, Z. W., Pińskwar, I. & Brakenridge, G. R. Changes in river flood hazard in Europe: a review. Hydrol. Res. 49, 294–302 (2018).

Wasko, C., Nathan, R. & Peel, M. C. Changes in antecedent soil moisture modulate flood seasonality in a changing climate. Water Resour. Res. 56, e2019WR026300 (2020).

Tarasova, L. et al. Shifts in flood generation processes exacerbate regional flood anomalies in Europe. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 49 (2023).

Beier, C. et al. Precipitation manipulation experiments–challenges and recommendations for the future. Ecol. Lett. 15, 899–911 (2012).

Dhakal, N., Jain, S., Gray, A., Dandy, M. & Stancioff, E. Nonstationarity in seasonality of extreme precipitation: a nonparametric circular statistical approach and its application. Water Res. Res. 51, 4499–4515 (2015).

Gründemann, G. J., Zorzetto, E., van de Giesen, N. & van der Ent, R. Historical shifts in seasonality and timing of extreme precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105200 (2023).

Marelle, L., Myhre, G., Hodnebrog, Ø., Sillmann, J. & Samset, B. H. The changing seasonality of extreme daily precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 11–352 (2018).

Contractor, S. et al. Rainfall Estimates on a Gridded Network (REGEN)–a global land-based gridded dataset of daily precipitation from 1950 to 2016. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 919–943 (2020).

Brönnimann, S. et al. Changing seasonality of moderate and extreme precipitation events in the Alps. Nat. Hazards Earth Sys. Sci. 18, 2047–2056 (2018).

Chan, S. C. et al. Europe-wide precipitation projections at convection permitting scale with the Unified Model. Clim. Dyn. 55, 409–428 (2020).

Moustakis, Y., Papalexiou, S. M., Onof, C. J. & Paschalis, A. Seasonality, intensity, and duration of rainfall extremes change in a warmer climate. Earths Future 9, e2020EF001824 (2021).

Pfahl, S. & Wernli, H. Quantifying the relevance of cyclones for precipitation extremes. J. Clim. 25, 6770–6780 (2012).

Catto, J. L. & Pfahl, S. The importance of fronts for extreme precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 10–791 (2013).

Knutti, R., Masson, D. & Gettelman, A. Climate model genealogy: generation CMIP5 and how we got there. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1194–1199 (2013).

Brunner, L. et al. Reduced global warming from CMIP6 projections when weighting models by performance and independence. Earth Syst. Dyn. 11, 995–1012 (2020).

van der Drift, R. J. & O’Gorman, P. A. Dependence of convective precipitation extremes on near-surface relative humidity. J. Clim. 1 https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-24-0738.1 (2025).

Williams, A. I. & O’Gorman, P. A. Summer-winter contrast in the response of precipitation extremes to climate change over Northern Hemisphere Land. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL096531 (2022).

Fischer, E. M., Beyerle, U. & Knutti, R. Robust spatially aggregated projections of climate extremes. Nat. Climate Change 3, 1033–1038 (2013).

Byrne, M. P. & O’Gorman, P. A. Link between land-ocean warming contrast and surface relative humidities in simulations with coupled climate models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5223–5227 (2013).

Byrne, M. P. & O’Gorman, P. A. Understanding decreases in land relative humidity with global warming: Conceptual model and GCM simulations. J. Clim. 29, 9045–9061 (2016).

Douville, H. & Willett, K. M. A drier than expected future, supported by near-surface relative humidity observations. Sci. Adv. 9, eade6253 (2023).

Vincent, L., Zhang, X., Mekis, É., Wan, H. & Bush, E. Changes in Canada’s climate: trends in indices based on daily temperature and precipitation data. Atmosphere Ocean 56, 332–349 (2018).

Pfahl, S., O’Gorman, P. A. & Fischer, E. M. Understanding the regional pattern of projected future changes in extreme precipitation. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 423–427 (2017).

Prein, A. F. et al. A review on regional convection-permitting climate modeling: demonstrations, prospects, and challenges. Rev. Geophys. 53, 323–361 (2015).

Contractor, S. et al. Rainfall Estimates on a Gridded Network based on long-term station data v1-2019. NCI National Research Data Collection. Available at https://doi.org/10.25914/5ca4c2c6527d2 (2019).

Zhu, D. et al. Future extreme precipitation may shift to colder seasons in northern mid- and high latitudes–Code and Data. ETH Research Collection. Available at https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000745834 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) through the project “AL CAPONE” (Grant No. 465143647). We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme’s Working Group on Coupled Modeling for coordinating CMIP, and we thank the participating climate modeling groups for making their model outputs available. We also recognize the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) for data archiving and access, supported by various funding agencies. We gratefully acknowledge the teams responsible for the development and maintenance of the REGEN observational dataset25. Finally, we thank the German Climate Computing Center (DKRZ) and ETH Zurich for providing storage and computational resources for this study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.H.Z. performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript. S.P. and E.F. initiated the project. S.P. conceived the research idea. E.F. and D.H.Z. developed the detailed framework for the study. R.K. assisted with result interpretation and provided critical feedback. All authors contributed to discussing the results and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Wenxia Zhang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Akintomide Akinsanola and Aliénor Lavergne. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, D., Pfahl, S., Knutti, R. et al. Future extreme precipitation may shift to colder seasons in northern mid- and high latitudes. Commun Earth Environ 6, 657 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02651-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02651-0

This article is cited by

-

Detecting anthropogenically induced changes in extreme and seasonal evapotranspiration observations

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Westerly jet waviness modulates mid-latitude hydroclimate variability

Nature Communications (2025)