Abstract

Over the past four decades, seasonal snow cover has declined rapidly in temperate alpine regions. However, the fine-scale dynamics of snowmelt preceding the ongoing warming period remain largely unknown, limiting our understanding of the long-term influence of past snow cover on alpine ecosystems. Here we rely upon the spatial similarities in melt-out patterns and a temperature-based model of fractional snow cover area, to reconstruct fine-scale snow cover changes over the past 250 years in instrumented catchments of the southwestern Alps. We provide evidence that, until the 1980s, prolonged snow cover in many late-lying snowfields delayed ecosystem development and explain why current vegetation cover, soil organic matter content, and mineral weathering are significantly lower in these areas than in surrounding ecosystems. These findings highlight the long-term legacy of snow cover on alpine landscapes and underscore the need to re-evaluate its effects on ecosystem structure, functioning, and responsiveness to ongoing changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, there has been growing recognition that ecosystem properties are, in part, shaped by the lasting effects of past environmental changes1,2,3. This dependence on past conditions, known as the legacy effect, operates across varying temporal scales. For example, climatic legacies on soil carbon stocks were reported at a millennial timescale2 while drought legacies on ecosystem phenology and productivity were observed a few months or years after the occurrence of extreme events4,5,6. Similarly, historical land use can leave lasting imprints on present-day ecosystems, persisting for decades or even centuries after the cessation of disturbances7,8,9. Accounting for legacy effects has proven pivotal to model the spatial distribution of biodiversity10 and understanding why biodiversity dynamics may lag behind changes in climate and land use11.

Climate legacies are often observed when shifts occur in the key drivers of ecosystem functioning, such as precipitation-related events in drylands1. A key driver of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in the arctic and temperate alpine zones is seasonal snow cover12,13,14. The insulating properties of the snowpack regulate soil microclimate, leading to cascading effects on nutrient fluxes15,16. Snowmelt timing determines the length of the growing season, influencing plant phenology17,18 and ecosystem productivity19. Consistent variations in snow cover duration are associated with shifts in taxonomic and functional diversity20,21,22,23. While recent studies have documented the short-term legacy effect of snow cover on ecosystem functioning24,25,26,27, to our knowledge, no study has explicitly investigated the legacy of snow cover on alpine landscapes over decadal to centennial timescales. This knowledge gap is problematic as it leads to completely overlooking the time-lagged responses of alpine biodiversity and ecosystem functioning to the ongoing decline in snow cover, observed in many Arctic and alpine ecosystems28,29.

The temperate mountains of Europe are among the fastest-warming areas on Earth30. Compared to the 1850–1900 period, air temperatures in the European Alps have risen by approximately 2.0 °C ± 0.3 °C31. Climate reconstructions indicate an acceleration of warming in recent decades, with an average temperature increase of approximately 0.3 °C ± 0.2 °C per decade32,33. This warming is particularly pronounced during summer at high elevations. In contrast, there are no significant trends in summer precipitation above 1500 m a.s.l.34,35, though large uncertainties persist due to the scarcity of high-elevation observations. The cryosphere is profoundly affected by these changes, as evidenced by a recent decline in snow cover duration, even at high elevations. This reduction is primarily driven by earlier snow melt-out dates (SMOD, i.e., the day of the year when the snow cover disappears) while Snow Onset Dates (SOD) in fall have shown no major change36,37. Furthermore, recent years have been characterized by unprecedented winter droughts and record-low snowpacks38,39. Although interannual variability in snow cover remains high, the last exceptionally snowy winters in the French Alps, for example, occurred in the late 1970s to early 1980s40, with no comparable snow accumulations observed since41,42,43.

The high spatial variability of snow cover in alpine landscapes presents a distinct challenge when examining the ecological consequences of the decadal-scale decline in snow cover duration. The SMOD can vary by over a month across a typical 50–100 m mesotopographical gradient, ranging from a wind-exposed ridge where snow does not accumulate to snow-drifts44,45. This local-scale variability amounts to the average reduction in snow cover duration observed at 2000 m in the French Alps between 1950–1980 and 1991–202036. Reductions in snow cover may either benefit ecosystem development by extending the growing season and favoring a positive carbon balance or have detrimental effects by reducing soil thermal insulation and limiting water and nutrient availability from the melting snowpack46. Recent findings confirm that rising air temperatures and associated changes in snow cover regimes have contrasting impacts on ecosystems depending on the topography47,48, hence the need to analyze snow cover changes at decametric resolution to better understand both the short- and long-term impacts of a changing cryosphere on alpine ecosystems.

Empirical evidence from ground surveys and remote sensing indicates a trend toward a greener and more productive alpine zone in response to recent climate warming49,50,51. In areas where snow accumulates, earlier snowmelt and warmer summers have led to a striking increase in plant cover, indicative of a shift to positive carbon balance52. Where snow melts out by mid-summer, the survival of photoautotrophs is pushed to its limits. For instance, plants require a minimum snow-free period of two months with positive root temperature to sustain a positive annual carbon balance53,54,55. If the growing season length falls below this critical threshold, vegetation cover, primary productivity, and soil development are delayed or inhibited. In this study, we test the hypothesis that past fluctuations in snow cover duration, particularly those that led to the crossing of this threshold, may have left lasting imprints on contemporary alpine landscapes.

Results and discussion

Low vegetation greenness and limited soil development in late-lying snowfields

Using 10 m resolution imagery, we analyzed the relationships between landforms and greenness anomalies in a representative treeless alpine landscape of the South-Western Alps (Methods, Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Fig. 1). The greenness anomaly is defined as the standardized difference between the annual maximum greenness of a pixel and the mean maximum greenness value of all pixels of the study catchments within the same elevation and aspect class (Methods). We found that negative greenness anomalies are not only observed on steep slopes, where mobile substrates limit plant establishment and growth, but also in flat areas and gentle slopes where snow accumulates (Fig. 1c, d). Specifically, an abrupt transition from positive to negative greenness anomalies is evidenced in areas of late snowmelt (i.e., SMOD after mid-June), between densely vegetated snowbeds (sites CF, dominated by the sedge Carex foetida) and sparsely vegetated late-lying snowfields (sites EA, characterized by alpine pioneer plants including Epilobium anagallidifolium) (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Table 1). The other main alpine habitats, including grasslands (MS, CT, PP, CM) and heathlands (VM), distributed along the snow cover gradient (Supplementary Table 1), exhibit positive anomalies of greenness (Fig. 2b). A unique long-term monitoring dataset of near-surface soil temperature across those habitats44 enabled the estimation of the SMOD at these sites. The shift in greenness anomaly from CF to EA corresponds to a 20- to 30-day delay in SMOD, typically occurring in the second half of June for CF and in the first half of July for EA (Fig. 2c). In contrast, the SOD shows much less variation between these sites (Fig. 2c). The negative greenness anomaly observed at EA sites is also reflected by anomalies in soil properties. Soil organic content, carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio and K2O:TiO2 ratio, used as a proxy of geochemical weathering, are significantly lower at EA sites (Fig. 2d–f). These characteristics, along with soil profile descriptions (Supplementary Table 2), indicate low soil development, consistent with recent findings from late-lying snowfields in the Pyrenees56.

a Infrared false-color SPOT 5 image (10 m resolution) showing the locations of the three study catchments (Lauzelle, Roche Noire, Mandette) in the above-treeline ecosystems of the southwestern French Alps, located between the Lautaret and Galibier passes. The black square marks the position of the FluxAlp weather station. b Standardized Anomaly of Greenness (SAG) derived from multi-temporal 10 m resolution SPOT 5 images collected during the 2015 growing season. For each pixel, SAG represents the standardized difference between the annual maximum of the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and the mean NDVI for all pixels in a similar topographic context, defined by elevation within ±50 m and Diurnal Anisotropic Heating within ±0.1 (Methods). c Example of a 5 m resolution binary snow cover map derived from a RapidEye Level3A product (European Space Agency, https://earth.esa.int/eogateway/catalog/rapideye-esa-archive) acquired on 10-07-2010, highlighting the distribution of late-lying snowfields (in blue). The fractional snow-covered area (fSCA) represents 15.5% of the study area. d Distribution of SAG for snow-covered and snow-free pixels from the RapidEye image (c), categorized by slope classes. Boxplots within the violin plots show the median, first quartile, and third quartile of the SAG distribution. The comparison between the no-snow and snow groups using a one-sided t test (no-snow greater than snow) is significant (P < 0.001) for all three slope classes (t = 85.874, df = 25,067 for slope <15°; t = 69.97, t = 179.26, df = 91,372 for slope >15° and <30°; t = 69.97, df = 39,233 for slope >30°). Credit: a, European Space Agency (ESA Earth online).

a Landscape view of the upper part of the Roche Noire catchment taken on 2021-07-02. The foreground shows a mosaic of late-snow melting habitats, including sparsely vegetated sites on incipient soils (EA) and densely vegetated sites (CF) on well-developed soils. b Standardized Greenness Anomaly for the main habitats identified along the snow cover gradient (Methods, Fig. 1b). c Distribution of snow melt-out date (SMOD) and snow onset day (SOD) per habitat. Values were inferred from 43 sites in which near-surface soil temperature was continuously monitored since 2007. Each dot represents a site × year combination (n = 354). The horizontal lines show the distribution of observed SMOD and SOD values across habitats, including the median (solid) and the first and last deciles (dashed). d Topsoil (0–10 cm) soil organic carbon (SOC) content, e C:N ratio, f K2O:TiO2 ratio used as a proxy of mineral weathering. The comparison between the EA (n = 12) and non-EA (n = 33) habitats using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test is significant (P < 0.001) for all three soil properties. Boxplots within the violin plots show the median, first quartile, and third quartile of the distribution. Credit: a Ph. Choler, CNRS.

In summary, our analysis of vegetation cover and soil properties reveals an ecosystem threshold in late snow-melting sites. A shift from grassy snowbeds on relatively deep soils (CF) to sparsely vegetated areas on incipient soils (EA) occurs over a short distance (typically 10–30 m) and corresponds to a difference of approximately 3 weeks in the growing season length. These fine-scale contrasts in ecosystem development may either result from the current snow cover regime or reflect a delayed ecosystem response to past snow cover conditions. Distinguishing between these two hypotheses requires a long-term, high-resolution reconstruction of snow cover dynamics.

Long-term similarities in snow-melting patterns

Reconstructing the distribution of snow cover duration over multiple decades is particularly challenging, as long-term series of meteorological variables driving snow accumulation and ablation during winter are not available. This limitation has hindered the development of process-based models of the dynamics of late-lying snowfields at an ecologically relevant scale and prompted the development of more empirical approaches57,58,59. Here, we drew upon the remarkable similarities of late-spring, early-summer spatial snowmelt patterns across the study catchments, as evidenced by the comparison of historical documents and current images (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 2). These repeated snow-melting figures have been observed in other temperate mountain ranges60,61,62,63, including the Japanese Alps, where the term Yukigata has been coined to describe the recurring landscape-scale features formed by late-lying snow patches64. To complement these historical documents, we processed 208 cloud-free satellite Landsat and Sentinel-2 images spanning from 1984 to 2023 to determine the spatial distribution of snow-covered pixels at 30 m resolution for specific values of fractional snow cover area (fSCA), i.e., the percentage of the catchments covered by snow (Methods and Supplementary Fig. 3). Pairwise comparisons of the annual SMOD maps show high similarities (mean overall accuracy of 0.88 ± 0.02 and kappa coefficient of 0.77 ± 0.04 for fSCA = 0.5) (Supplementary Fig. 4), indicating a high probability that snow melting patterns repeat from one year to the next. We attribute these similarities to the strong control exerted by topography and consistent wind-driven snow redistribution60,65. Therefore, it is possible to estimate with high confidence whether a pixel is snow-covered based on a given value of fSCA (Fig. 3c–e). Additionally, the Day of Year (DOY) when fSCA reaches a low value (typically 0.1) can be used as a proxy for the time at which late-lying snowfields are the only remaining snow-covered areas within the catchments (Fig. 3e).

a, b Early summer snowmelt patterns illustrated by a historical postcard from 1900 and a recent photograph from 2024, both taken from a similar vantage point. The black line indicates the north-facing slopes of the Roche Noire catchment. c–e Probability of snow cover for varying values of fractional Snow Covered Area (fSCA). This probability is calculated as the proportion of years in which a pixel is modeled as snow-covered during the period 1984–2023 using 30 m resolution satellite images (Methods). Bar plots display the percentage of snow-covered (blue) and snow-free (pale yellow) pixels with a probability greater than 0.9. Pale blue pixels have a probability of being either snow-covered or snow-free below 0.9. The contour in black corresponds to the spotted area in panels (a) and (b). Credit: a, b Editions Gilletta, Nice a; b Jardin du Lautaret, CNRS.

Seasonal decline in fractional snow cover area driven by accumulated degree days

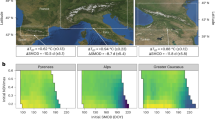

We used the same archive of satellite images to develop a low-dimensional, temperature-based model of fSCA using a degree-day (DD) approach66(Methods, Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5). DD was estimated as the cumulative sum of mean daily air temperatures above 0 °C from January 1st to the date of scene acquisition, using air temperature time series recorded at the FluxAlp weather station, located at the base of one of the study catchments (Methods, Fig. 1a). A three-parameter log-logistic function accurately captured the seasonal decline in fSCA with increasing DD (MAE = 0.07, RMSE = 0.1) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 5b, c). We adopted this straightforward yet effective snowmelt model to facilitate its application in historical reconstructions.

A three-parameter log-logistic function was fitted to relate DD to fSCA using 208 cloud-free Landsat and Sentinel-2 images (gray dots) available for the period 1984–2023. For each image, the normalized difference snow index (NDSI) was calculated, and fSCA was inferred as the percentage of pixels in the study catchments with NDSI < 0.154 (Methods). DD is the sum of daily mean air temperatures above 0 °C, measured at FluxAlp from January 1st to the date of image acquisition. Superimposed colored horizontal bars show the DD values in all sites where soil temperature was monitored. DD were estimated from January 1st to the SMOD using the same time series of air temperature measured at FluxAlp. The bars, shown for each habitat, extend from the first to the third quartile of the DD distribution. See Supplementary Fig. 5 for model parameters and goodness-of-fit estimates.

We estimated the DD corresponding to the SMOD for each site-year combination and found that specific fSCA values reliably predict whether a given site is snow-covered or snow-free. For instance, when fSCA is 0.1, corresponding to a DD of 760 °C, EA sites remain snow-covered, whereas snow at CF sites has already melted (Fig. 4). These findings pave the way for using historical DD reconstructions to track habitat-specific long-term changes in snow cover duration.

Legacy of snow cover duration

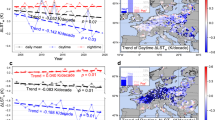

To model long-term DD time series, we combined air temperature records (available since 1946) from a nearby weather station at 1800 m a.s.l., located 10 km from the study catchments, with historical climate reconstructions for the European Alps67(Methods, Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). The sharp increase in DD observed since the late 1980s is unprecedented over the past 250 years (Fig. 5a). Earlier DD fluctuations, including those during the Little Ice Age, were significantly lower in magnitude compared to this recent warming trend. These results are consistent with regional climate reconstructions derived from tree-rings68 and historical archives69.

a Estimated DD from January 1st to mid-August (DOY = 227) over the past 250 years. We used quantile regression to adjust the long-term air temperature time series, either measured at the nearby weather station in Le Monêtier-les-Bains or reconstructed using the Histalp dataset, to FluxAlp (Methods). b Reconstructed SMOD for late snow melting sites corresponding to the EA, CF, and MS habitats (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Table 1). Time series are shown for each habitat, corresponding to the date when the median DD value for each habitat is reached. For readability, confidence intervals for SMOD estimates are shown only for EA. A SMOD in mid-August (vertical gray line) indicates a snow-free season of less than two months, which is insufficient for sustained plant growth and soil development. The black line represents the SMOD required to reach DD values of 800 °C (DD800). The bold lines in panels a and b represent a Gaussian filter (using sigma = 8). See Supplementary Fig. 6 for the goodness-of-fit estimates of the quantile regression models.

Time series analysis of DD enabled us to infer the long-term trajectories of SMOD for late-melting sites (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). For example, the DD required for complete snowmelt at EA sites was estimated at approximately 1000 °C (Fig. 4), a threshold that was not reached until mid-August before the 1980s (Fig. 5b). When considering a SMOD in mid-August, corresponding to a snow-free season of one to two months, the average DD before the 1980s was above 800 °C (Fig. 5b). This value falls within the DD range that distinguishes CF from EA sites (Fig. 4). We conclude that conditions favorable for vascular plant persistence and pedogenesis have prevailed at CF sites for at least the past 250 years, whereas such conditions were absent at EA sites prior to the 1980s.

We do not rule out the possibility of transient colonization of EA sites during warmer periods, such as the 1940s, when the SMOD occurred earlier (Fig. 5a, b). Vegetative forms of some alpine plants can persist for several years beneath a continuous snowpack54,70, enabling survival under suboptimal thermal conditions. In addition, source populations of pioneer plants are growing near the retreating snow patches, facilitating a rapid colonization of newly exposed ground. However, even if windows of opportunity for ecosystem development existed before the 1980s, the series of cold and snowy years during the 1970s likely reset the system, initiating a new phase of primary succession after the 1980s.

Currently, DD values observed at EA sites resemble thermal conditions experienced by CF sites during colder periods (Fig. 5b), indicating that local conditions at EA sites are now favorable for increased primary productivity, mineral weathering, and soil formation. However, our analysis suggests that ecosystem properties at EA sites will require much more time—likely several decades—to approach those observed at CF sites. This finding is consistent with long-term vegetation surveys in glacier forelands, where early successional stages can persist several decades, while pioneer species coverage gradually increases71.

We conclude that the prolonged snow cover duration before the 1980s has left a detectable imprint on the present-day landscape, which we interpret as a legacy effect of snow cover on the alpine landscape. The detectability of such a legacy effect depends on the timescale of ecosystem response to environmental change. In this case, the legacy effect is observable because ecosystem properties—such as soil formation and vegetation development—respond slowly following the removal of the limiting factor—namely, the insufficiently long snow-free season. A similar phenomenon has been hypothesized in high-Arctic ecosystems to explain the presence of vegetation trimlines in relation to past snowfield expansions72.

Far-reaching implications

Our findings have broad implications for understanding alpine ecosystem responses to climate change.

First, late-lying snowfields, covering approximately 1750 km2 in the above-treeline area of the European Alps (see Methods), are comparable in coverage to the glaciers (2080 km2)73 but are more evenly distributed (Supplementary Fig. 7). Late-lying snowfields extend into lower elevation massifs and areas where glaciers never existed or have already disappeared forming a fragmented network. Their fragmented distribution provides a network of refugia for cold-adapted biodiversity, favoring its persistence amid climate change74,75.

Second, the temporal stability of snowmelt patterns along with snow cover decline since the 1980s suggests that many late-lying snowfields still bear the imprint of past snow cover changes. These legacy effects offer a framework for understanding landscape-scale anomalies in soil properties and vegetation cover associated with the persistence of alpine pioneer species. They challenge current biodiversity models, including those recognizing snow cover as a key driver76, that assume species distributions are determined solely by present environmental conditions and overlook the importance of lagged ecological responses when predicting the present and future states of alpine biodiversity.

Finally, late-lying snowfields exhibiting negative greenness anomalies are responding more rapidly to recent climate warming than other alpine habitats52, suggesting an ongoing “catching-up” phenomenon50. These uneven rates of change across ecosystems are also underrepresented in current models of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning.

Overall, our findings highlight the need to re-evaluate the long-term legacy effects of snow cover on alpine landscapes, to advance our understanding of both alpine ecosystem structure and their responsiveness to ongoing climate change.

Methods

Study area

The study area comprises three high-elevation, above-treeline catchments located between the Lautaret pass and the Galibier pass in the southwestern French Alps (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 3). The main bedrock is represented by flysch sediments, locally known as the Flysch des Aiguilles d’Arves77. Air temperature, precipitation and snow depth have been continuously recorded since 2013 at the FluxAlp micrometeorological station (ICOS code FR-CLt, https://meta.icos-cp.eu/resources/stations/ES_FR-CLt), located near the outlet of the Roche Noire catchment at 2050 m a.s.l. (Fig. 1a). In addition, 43 standalone temperature data loggers (Hobo pendant UA, Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, MA) monitor near-surface soil temperatures on an hourly basis, with most time series beginning in 200744. We estimated SMOD as the first day in late spring, early summer, where the daily mean soil temperatures were above 0.5 °C and the daily thermal amplitude was above 1 °C. Late-spring snow falls leading to ephemeral snow coverage (typically lasting less than 3 days), regardless of habitat type, were not considered in the estimation of SMOD44. Supplementary Figure 8 shows the relation between remotely-sensed and ground-level estimates of SMOD.

Greenness anomaly

The greenness anomaly was calculated as the difference between the annual maximum of the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVImax) of a pixel i, located at an elevation ELEVi and with a Diurnal Anisotropic Heating DAHi, and the mean NDVImax value of all pixels within the catchments falling within the elevation range [ELEVi − 50 m; ELEVi + 50 m] and the DAH range [DAHi − 0.1; DAHi + 0.1]. The standardized anomaly of greenness (SAG) was then obtained by dividing this difference by the standard deviation of NDVImax of all pixels within the selected ranges of elevation and DAH. Negative anomalies indicate an abnormally low NDVImax value relative to elevation and DAH. NDVImax for each pixel was derived from a time series of 10 m resolution SPOT5 images acquired by the French Space Agency (CNES) and the European Space Agency (ESA) from April to September 201578.

Plant species assemblages

We recorded plant species composition in 120 physiognomically homogeneous plots, measuring between 16 m2 and 25 m2. The plot x species dataset was clustered using the partitioning around medoids (PAM) algorithm of the R package cluster79, based on a dissimilarity matrix from presence/absence data. Rare species with fewer than three occurrences were discarded. The Euclidean distance between two plots was computed as sqrt(A + B − 2C), where A and B are the number of species in the two plots and C is the number of species occurring in both plots. We identified seven floristic clusters corresponding to the alpine habitats spanning the study snow cover gradient. The strength of the association between a species and a cluster was quantified using the Indicator Species Analysis implemented in the R package indicspecies80,81. Indicator plant species per habitat are listed in the Supplementary Table 1.

Soil chemical analysis

Soil analyses were conducted on 42 profiles representing all plant communities. Each profile was sampled systematically at 10 cm intervals from the surface to the parent material, which was also collected. Soils were classified according to the World reference base for soil resources 201482 (Supplementary Table 2). Soil organic carbon (SOC) and nitrogen contents were determined on dried and ground samples using a CHN elemental analyzer (Flash EA 1112, Thermo Electron Corporation, ThermoFisher). Geochemical composition of major elements was analyzed using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (S8 Tiger Series 2, Bruker)83. Soil weathering was evaluated using the classical K2O:TiO2 ratio of the 0–10 cm horizon84,85. We found a high heterogeneity of the K2O:TiO2 ratio in the parent rocks (Supplementary Fig. 9), because the flysch sediments are composed of a succession of decametric beds with varying grain size and mineralogical composition. However, we found no difference in K2O:TiO2 ratio of the parent material between EA (n = 12) and non-EA (n = 33) using a two-sided Wilcoxon non-parametric test, while a significant difference of this ratio was found between EA and non-EA topsoils (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Remote sensing

A total of 208 cloud-free, 30 m resolution satellite images acquired from February to mid-August were included in our analysis. For the recent period (2013 onward), 138 Landsat 8 OLI and Sentinel-2 surface reflectance images were retrieved from the Theia repository86. For the period 1985–2012, we used Google Earth Engine (GEE) to extract 80 additional Landsat 5 TM and 7 ETM+ surface reflectance images from the Landsat Collection 2. We calculated a Normalized Difference Snow Index using the equation: NDSI = rVIS − rSWIR/rVIS + rSWIR, where VIS and SWIR are the top-of-atmosphere reflectance bands in the green and short-wave Infrared, respectively. We used an NDSI threshold of 0.154 to determine whether pixels were snow-free or snow-covered87 and to estimate their percentage in the study catchments, i.e., the fractional snow cover area (fSCA). The between-year consistency of snow-covered areas for a given fSCA was evaluated using two indices: the overall accuracy and the kappa coefficient88. To assess the extent of late-lying snowfields in the European Alps, we processed all available cloud-free Landsat Collection 2 satellite images to compute the median SMOD for the period 2004–2023 and identified locations where the SMOD occurred between DOY 195 (mid-July) and DOY 245 (end of August) (see “Code availability”).

Climate

We implemented a degree days (DD) approach to model the seasonal decline of fSCA over a season66. A 3-parameter log-logistic function was fitted to data, using the 2013–2023 period for calibration and the 1985–2012 period for evaluation. DD was calculated as the cumulative sum of daily mean temperatures above 0 °C from January 1st to the date of interest (e.g., image acquisition or SMOD at instrumented sites). Model parameters were optimized using nonlinear least-squares estimates and a Gauss-Newton algorithm. Confidence intervals for model parameters were estimated using bootstrapping methods. To evaluate model performance, we fitted a standardized major axis between observed and predicted fSCA and calculated goodness-of-fit statistics including R-squared, mean absolute error (MAE), and mean systematic error (MSE) (Supplementary Fig. 5). To keep the approach straightforward, the model assumes a constant contribution of warming temperatures without including a decay factor to account for changes in air temperature effects as snow ripens and incident radiation increases. Similarly, we chose not to include snowfalls or snow depth in the model, as it would limit its applicability for long-term reconstructions, given the uncertainty in the amount and phase of precipitation in the climate of the past.

Long-term DD reconstructions relied on temperature records from the Le-Monêtier-les Bains weather station (1800 m a.s.l.), located 15 km from the Roche Noire outlet, and at which daily minimum (Tmin) and maximum (Tmax) temperatures have been monitored since 1944. Daily mean temperatures were calculated as 0.5 × (Tmin + Tmax). For historical reconstructions spanning 1780–2010, we used the monthly records provided by the Histalp database67. Monthly temperatures were disaggregated on a daily basis using a Fast Fourier Transform89. Historical daily mean air temperatures were aligned with the FluxAlp time series using either quantile mapping or quantile regression techniques, with the latter showing slightly better performance (MAE = 2.73 vs. MAE = 3.61 when aligning Histalp with Le-Monêtier-les Bains over a 70-year-long period) (Supplementary Fig. 6). The final model was built on a monthly basis using the quantile 0.5 and using the function rq of the R package quantreg90.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Weather station data are available at https://meteo.data.gouv.fr/datasets/. Histalp data are available at https://www.zamg.ac.at/histalp/. Soil temperature data are available at https://entrepot.recherche.data.gouv.fr/dataverse/ZAA_SOIL_TEMP. Landsat 8 (2013–2023) and Sentinel-2 snow cover binary maps are retrieved from the Theia Land catalog at https://catalogue.theia-land.fr/. Source data of all figures have been deposited at https://zenodo.org/uploads/1521165291.

Code availability

The GEE scripts for Landsat image extraction, estimates of SMOD are available at https://code.earthengine.google.com/ebf3a71b8502f53a70bf6e4fc63ff6de?noload=true. The R scripts to produce the figures are available at https://zenodo.org/uploads/15211652.

References

Monger, C. et al. Legacy effects in linked ecological-soil-geomorphic systems of drylands. Front. Ecol. Environ. 13, 13–19 (2015).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. Climate legacies drive global soil carbon stocks in terrestrial ecosystems. Sci. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1602008 (2017).

Tappeiner, U., Leitinger, G., Zarina, A. & Bürgi, M. How to consider history in landscape ecology: patterns, processes, and pathways. Landsc. Ecol. 36, 2317–2328 (2021).

Kannenberg, S. A., Schwalm, C. R. & Anderegg, W. R. L. Ghosts of the past: how drought legacy effects shape forest functioning and carbon cycling. Ecol. Lett. 23, 891–901 (2020).

Bastos, A. et al. Direct and seasonal legacy effects of the 2018 heat wave and drought on European ecosystem productivity. Sci. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba2724 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Drought legacies delay spring green-up in northern ecosystems. Nat. Clim. Change https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02273-6 (2025).

Partel, M., Helm, A., Reitalu, T., Liira, J. & Zobel, M. Grassland diversity related to the Late Iron Age human population density. J. Ecol. 95, 574–582 (2007).

Dambrine, E. et al. Present forest biodiversity patterns in France related to former Roman agriculture. Ecology 88, 1430–1439 (2007).

Vuichard, N., Ciais, P., Viovy, N., Calanca, P. & Soussana, J. F. Estimating the greenhouse gas fluxes of European grasslands with a process-based model: 2. Simulations at the continental level. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles https://doi.org/10.1029/2005gb002612 (2007).

Auffret, A. G., Kimberley, A., Plue, J. & Waldén, E. Super-regional land-use change and effects on the grassland specialist flora. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05991-y (2018).

Bürgi, M., Östlund, L. & Mladenoff, D. J. Legacy effects of human land use: ecosystems as time-lagged systems. Ecosystems 20, 94–103 (2017).

Jones, H. G., Pomeroy, J. W., Walker, D. A. & Hoham, R. W. Snow Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Examination of Snow-Covered Ecosystems. (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Walker, D. A., Halfpenny, J. C., Walker, M. D. & Wessman, C. A. Long-term studies of snow-vegetation interactions. Bioscience 43, 287–301 (1993).

Rixen, C. et al. Winters are changing: snow effects on Arctic and alpine tundra ecosystems. Arct. Sci. 8, 572–608 (2022).

Edwards, A. C., Scalenghe, R. & Freppaz, M. Changes in the seasonal snow cover of alpine regions and its effect on soil processes: a review. Quat. Int. 162, 172–181 (2007).

Lyu, Z. et al. Seasonal dynamics of arctic soils: capturing year-round processes in measurements and soil biogeochemical models. Earth https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2024.104820 (2024).

Kudo, G. Performance and phenology of alpine herbs along a snow-melting gradient. Ecol. Res. 7, 299–316 (1992).

Vorkauf, M., Kahmen, A., Korner, C. & Hiltbrunner, E. Flowering phenology in alpine grassland strongly responds to shifts in snowmelt but weakly to summer drought. Alp. Bot. 131, 73–88 (2021).

Choler, P. Growth response of temperate mountain grasslands to inter-annual variations in snow cover duration. Biogeosciences 12, 3885–3897 (2015).

Kudo, G. & Ito, K. Plant distribution in relation to the length of the growing season in a snow-bed in the Taisetsu mountains, northern Japan. Vegetatio 98, 319–328 (1992).

Zinger, L., Shahnavaz, B., Baptist, F., Geremia, R. A. & Choler, P. Microbial diversity in alpine tundra soils correlates with snow cover dynamics. ISME J. 3, 850–859 (2009).

Kosolapova, A. & Altshuler, I. Effects of reduced snowpack due to climate warming on abiotic and biotic soil properties in alpine and boreal forest systems. Plos Clim. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000417 (2024).

Carlson, B. Z., Choler, P., Renaud, J., Dedieu, J.-P. & Thuiller, W. Modelling snow cover duration improves predictions of functional and taxonomic diversity for alpine plant communities. Ann. Bot. 116, 1023–1034 (2015).

Hua, J., Sun, Q. Q. & Marschner, P. Immediate and prolonged effects of snow coverage alteration on soil carbon dynamics and microbial activity: a meta-analysis. Geoderma https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2024.117029 (2024).

Li, Y. Y., Sun, Q. Q., Zou, H. F. & Marschner, P. Distance to a river modifies climate legacy on vegetation growth in a Boreal Riparian forest. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15235582 (2023).

Pauli, J. N., Zuckerberg, B., Whiteman, J. P. & Porter, W. The subnivium: a deteriorating seasonal refugium. Front. Ecol. Environ. 11, 260–267 (2013).

Slatyer, R. A., Umbers, K. D. L. & Arnold, P. A. Ecological responses to variation in seasonal snow cover. Conserv. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13727 (2022).

Estilow, T. W., Young, A. H. & Robinson, D. A. A long-term Northern Hemisphere snow cover extent data record for climate studies and monitoring. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 7, 137–142 (2015).

Bormann, K. J., Brown, R. D., Derksen, C. & Painter, T. H. Estimating snow-cover trends from space. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 923–927 (2018).

European Environment Agency. European Climate Risk Assessment, EEA Report No 1/2024, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/european-climate-risk-assessment. (2024).

Monteiro, D. & Morin, S. Multi-decadal past winter temperature, precipitation and snow cover information over the European Alps using multiple datasets. EGUsphere 2023, 1–62 (2023).

Pepin, N. C. et al. Climate changes and their elevational patterns in the mountains of the world. Rev. Geophys. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020rg000730 (2022).

Beaumet, J. et al. Twentieth century temperature and snow cover changes in the French Alps. Reg. Env. Change https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-021-01830-x (2021).

Masson, D. & Frei, C. Long-term variations and trends of mesoscale precipitation in the Alps: recalculation and update for 1901-2008. Int. J. Climatol. 36, 492–500 (2016).

Ménégoz, M. et al. Contrasting seasonal changes in total and intense precipitation in the European Alps from 1903 to 2010. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 5355–5377 (2020).

Matiu, M. et al. Observed snow depth trends in the European Alps: 1971 to 2019. Cryosphere 15, 1343–1382 (2021).

Essery, R. et al. Snow cover duration trends observed at sites and predicted by multiple models. Cryosphere 14, 4687–4698 (2020).

Brunner, M. I., Götte, J., Schlemper, C. & Van Loon, A. F. Hydrological Drought Generation Processes and Severity Are Changing in the Alps. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022gl101776 (2023).

Avanzi, F. et al. Winter snow deficit was a harbinger of summer 2022 socio-hydrologic drought in the Po Basin, Italy. Commun. Earth Env. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01222-z (2024).

Le Roux, E., Evin, G., Eckert, N., Blanchet, J. & Morin, S. Elevation-dependent trends in extreme snowfall in the French Alps from 1959 to 2019. Cryosphere 15, 4335–4356 (2021).

Vernay, M. et al. The S2M meteorological and snow cover reanalysis over the French mountainous areas: description and evaluation (1958-2021). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 1707–1733 (2022).

Bozzoli, M. et al. Long-term snowfall trends and variability in the Alps. Int. J. Climatol. 44, 4571–4591 (2024).

Gascoin, S. et al. Evolution of the snow cover during the 2022 drought in France. Lhb-Hydrosci. J. https://doi.org/10.1080/27678490.2024.2314174 (2024).

Choler, P. Winter soil temperature dependence of alpine plant distribution: Implications for anticipating vegetation changes under a warming climate. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 30, 6–15 (2018).

Billings, W. D. & Bliss, L. C. An alpine snowbank environment and its effect on vegetation, plant development and productivity. Ecology 40, 388–397 (1959).

Körner, C. Alpine Plant Life. (Springer Verlag, 1999).

Liberati, L., Messerli, S., Matteodo, M. & Vittoz, P. Contrasting impacts of climate change on the vegetation of windy ridges and snowbeds in the Swiss Alps. Alp. Bot. 129, 95–105 (2019).

Oldfather, M. F. et al. Divergent community trajectories with climate change across a fine-scale gradient in snow depth. J. Ecol. 112, 126–137 (2024).

Kullman, L. A richer, greener and smaller alpine world: review and projection of warming-induced plant cover change in the Swedish Scandes. Ambio 39, 159–169 (2010).

Choler, P. et al. The tempo of greening in the European Alps: spatial variations on a common theme. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 5614–5628 (2021).

Anderson, K. et al. Vegetation expansion in the subnival Hindu Kush Himalaya. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 1608–1625 (2020).

Choler, P., Bayle, A., Fort, N. & Gascoin, S. Waning snowfields have transformed into hotspots of greening within the alpine zone. Nat. Clim. Change https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02177-x (2025).

Korner, C. Coldest places on earth with angiosperm plant life. Alp. Bot. 121, 11–22 (2011).

Crawford, R. M. M. Cold climate plants in a warmer world. Plant Ecol. Divers. 1, 285–297 (2008).

Crawford, R. M. M. Plants at the Margin—ecological Limits and Climate Change. (2008).

Vidaller, I. et al. Incipient soils: new habitats in proglacial areas of the Maladeta massif (Central Pyrenees). Sci. Total Environ. 967, 178740 (2025).

Erickson, T. A., Williams, M. W. & Winstral, A. Persistence of topographic controls on the spatial distribution of snow in rugged mountain terrain, Colorado, United States. Water Resour. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003wr002973 (2005).

Winstral, A., Elder, K. & Davis, R. E. Spatial snow modeling of wind-redistributed snow using terrain-based parameters. J. Hydrometeorol. 3, 524–538 (2002).

Largeron, C. et al. Toward snow cover estimation in mountainous areas using modern data assimilation methods: a review. Front. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2020.00325 (2020).

Sturm, M. & Wagner, A. M. Using repeated patterns in snow distribution modeling: an Arctic example. Water Resour. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010wr009434 (2010).

Bloschl, G. & Kirnbauer, R. An analysis of snow cover patterns in a small alpine catchment. Hydrol. Process. 6, 99–109 (1992).

Egli, L., Jonas, T., Grünewald, T., Schirmer, M. & Burlando, P. Dynamics of snow ablation in a small Alpine catchment observed by repeated terrestrial laser scans. Hydrol. Process. 26, 1574–1585 (2012).

Gjaeveroll, O. The Plant Communities of the Scandinavian Alpine Snow-Beds. 1 (Bruns, 1956).

Han, Y. A. study on the relationship between the Japanese cultural landscape YUKIGATA and the Chinese zodiac culture. Acad. J. Human. Soc. Sci. 6, 24–30 (2023).

Pflug, J. M. & Lundquist, J. D. Inferring distributed snow depth by leveraging snow pattern repeatability: investigation using 47 Lidar Observations in the Tuolumne Watershed, Sierra Nevada, California. Water Resour. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020wr027243 (2020).

Rango, A. & Martinec, J. Revisiting the degree-day method for snowmelt computations. Water Resour. Bull. 31, 657–669 (1995).

Auer, I. et al. HISTALP—historical instrumental climatological surface time series of the Greater Alpine Region. Int. J. Climatol. 27, 17–46 (2007).

Kuhl, E. et al. Revising Alpine summer temperatures since 881 CE. Clim. Dyn. 62, 6141–6157 (2024).

Wanner, H., Pfister, C. & Neukom, R. The variable European Little Ice Age. Quat. Sci. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2022.107531 (2022).

Pielou, E. C. After the Ice Age: the Return of Life to Glaciated North America. (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

Erschbamer, B., Schlag, R. N., Carnicero, P. & Kaufmann, R. Long-term monitoring confirms limitations of recruitment and facilitation and reveals unexpected changes of the successional pathways in a glacier foreland of the Central Austrian Alps. Plant Ecol. 224, 373–386 (2023).

Wolken, G. J., England, J. H. & Dyke, A. S. Re-evaluating the relevance of vegetation trimlines in the Canadian Arctic as an indicator of Little Ice Age paleoenvironments. Arctic 58, 341–353 (2005).

RGI 7.0 Consortium. Randolph Glacier Inventory—A Dataset of Global Glacier Outlines, Version 7.0. (National Snow and Ice Data Center, Boulder, Colorado, USA). https://doi.org/10.5067/f6jmovy5navz (2023).

Steinbauer, M. J. et al. Accelerated increase in plant species richness on mountain summits is linked to warming. Nature 556, 231 (2018).

Muhlfeld, C. C. et al. Specialized meltwater biodiversity persists despite widespread deglaciation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 12208–12214 (2020).

Panchard, T., Broennimann, O., Gravey, M., Mariethoz, G. & Guisan, A. Snow cover persistence as a useful predictor of alpine plant distributions. J. Biogeogr. 50, 1789–1802 (2023).

Dumont, T. et al. Structural and sedimentary records of the Oligocene revolution in the Western Alpine arc. J. Geodyn. 56-57, 18–38 (2012).

Dedieu, J.-P. et al. On the importance of high-resolution time series of optical imagery for quantifying the effects of snow cover duration on alpine plant habitat. Remote Sens. 8, 481–481 (2016).

Maechler, M., Rousseeuw, P. J., Struyf, A., Hubert, M. & Hornik, K. cluster: Cluster Analysis Basics and Extensions. R Package Version 2.1.6. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cluster (2023).

Dufrêne, M. & Legendre, P. Species assemblages and indicator species: the need for a flexible asymetrical approach. Ecol. Monogr. 67, 345–366 (1997).

De Caceres, M. & Legendre, P. Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference. Ecology 90, 3566–3574 (2009).

IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, update 2015. International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps. World Soil Resources Reports No. 106. FAO, Rome. (2015).

Towett, E. K., Shepherd, K. D. & Cadisch, G. Quantification of total element concentrations in soils using total X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (TXRF). Sci. Total Environ. 463, 374–388 (2013).

Bajard, M. et al. Progressive and regressive soil evolution phases in the Anthropocene. Catena 150, 39–52 (2017).

Brantley, S. L. & Lebedeva, M. in Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Vol 39 39 Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences (eds R. Jeanloz & K. H. Freeman) 387–416 (2011).

Gascoin, S. et al. Estimating fractional snow cover in open terrain from Sentinel-2 using the normalized difference snow index. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12182904 (2020).

Bayle, A., Gascoin, S., Corona, C., Stoffel, M. & Choler, P. Snow melt-out date (SMOD) change spanning four decades in European temperate mountains at 30 m from Landsat time series. Sci. Data https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05044-2 (2025).

Congalton, R. G. A review of assessing the accuracy of classification of remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. Environ. 37, 35–46 (1991).

Singleton, R. (IEEE Digital Signal Processing Committee, IEEE Press, 1979).

Koenker, R. quantreg: quantile regression. R package version 6.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=quantreg (2025).

Choler, P. et al. Legacy of snow cover on alpine landscapes. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/uploads/15211652 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of the Jardin du Lautaret, D. Gateuille, J. Puissant, and the undergraduate students of the BEE and ECOMONT programs for their support during fieldwork. We are also grateful to W. Galloway and F. Dominé for their valuable feedback and discussions on the manuscript. This research was funded by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (project TOP, grant no. ANR-20-CE32-0002) and the EC2CO program of the CNRS (project HERCULEEN). Additional support was provided by the Jardin du Lautaret and the LTSER Zone Atelier Alpes, with the Lautaret/Roche Noire site being part of the eLTER Research Infrastructure (https://deims.org/8574370e-934e-418a-af63-e15f4cbc5084). LECA acknowledges funding from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (grant nos. Labex OSUG@2020 and IA-10-LABX-0056).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study builds upon years of sustained and collaborative fieldwork conducted jointly by P.C. and J.P. P.C. first conceptualized the idea of snow cover legacies, designed the study, conducted the final analyses, and led the manuscript writing. N.B., J.-C.C., and J.P. led soil sampling and performed soil chemical analyses. A.B. and S.G. contributed to the methodology and processing of remote sensing data. A.R., J.-M.C., and D.V. provided data from the FluxAlp weather station and contributed to climate data analysis. C.C. brought his expertise to historical climate reconstruction. L.L. and B.N. organized the field campaigns and actively participated in the fieldwork. All co-authors extensively discussed the study during a week-long field and brainstorming session at the Lautaret Pass in September 2024. All authors contributed to data interpretation and manuscript editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Javier Herrero and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choler, P., Bonfanti, N., Reverdy, A. et al. Legacy of snow cover on alpine landscapes. Commun Earth Environ 6, 758 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02702-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02702-6