Abstract

Decarbonizing the energy sector requires renewable sources that are economic and responsive to demand. Intermittency and seasonal variability, therefore, limit the potential of wind and solar. Geothermal energy can potentially provide low-carbon renewable power that is dispatchable and responsive to demand. However, conventional geothermal methods require high permeability in high-temperature subsurface zones, which restricts their application. Here, we assess the global potential of the closed-loop geothermal system (CLGS), an emerging technology that does not require high permeability. Using thermodynamic, process, and technoeconomic modeling, we analyze the potential for CLGS in 12,000 candidate regions to estimate global viability. With the base case of water as the working fluid in a Rankine cycle, we estimate the global potential to be 9 TWe, equivalent to 70% of current electricity production. We assess using phase change working fluids to broaden applicability and improve efficiency, and evaluate the remaining technological barriers to closed-loop geothermal energy production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The intermittency of solar and wind power sources is a barrier to deploying them on a large scale and attaining decarbonization goals1,2,3. Geothermal energy is a renewable source that can provide continuous baseload power and be dispatched to meet demand4,5. Reaching net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 is expected to require a 13% annual increase in geothermal energy production6. However, conventional geothermal technologies are not on track to expand at this rate due in large part to a dependency on geology—underground resources that offer both high temperature and high permeability7,8,9,10. Additional challenges stem from the open nature of these systems, with the fluid exchange between the system and the reservoir, and the risk of induced seismicity where fracturing is required to induce permeability9,11. Closed-loop geothermal systems (CLGS) present an alternative in which the working fluid is contained throughout the process12. CLGS provides an opportunity to tap into hot impermeable reservoirs where heat conduction, rather than convection, is the dominant mechanism. The amagmatic regions (typical of sedimentary basins) and igneous rocks (typical of volcanic regions) with temperatures of >225 °C are examples of such hot domains13. The fluid circulates in a closed-loop system, and the loop acts as an underground heat exchanger, extracting heat from the earth. The closed-loop nature of this technology thus also has the potential to avoid the limitations of conventional geothermal approaches, with respect to geology and selection of working fluid. Interest in this technology is growing, and field-scale CLGS in Alberta and California has been successfully implemented in deep underground layers14,15.

Despite the advantages of CLGS, deployment incurs high capital costs due to uncertainties in drilling, especially in the deep, high-temperature formations of the most interest8,16,17. Drilling a single multilateral set can cost 50–100 million USD, and profitability depends on power generation and demand18. Although the closed nature of CLGS provides flexibility regarding working fluid and avoids the challenges associated with open-loop geothermal systems19,20, the energy transfer process relies on conduction rather than convection, limiting power-generation efficiency16. As a result, CLGS requires high-temperature rock to leverage heat flow and perform efficiently. Subsurface conditions—thermal gradient, thermal conductivity, and heat flow—vary widely, as does the viability of CLGS. While the performance of a single CLGS in a given geology is becoming established16,20,21,22, the global potential for this technology is unknown. Widespread adoption requires energy and techno-economic analyses (TEA) to map low- and high-risk geothermal resources and evaluate the system’s viability across diverse geological conditions.

Herein, we assess the global potential of CLGS. We analyzed geothermal gradients to identify potential locations and optimal depths around the world. We investigate the base case of single-loop CLGS with organic Rankine cycles, as well as the potential for multilateral wells, advanced geothermal working fluids, and additional energy recovery routes such as thermosiphon turbines. We assess the energy production cost, economic viability, and barriers to developing CLGS and compare these with other renewable energy sources. This study analyzes the benefits and challenges of CLGS technology and provides a roadmap to increase production of low-carbon geothermal energy globally.

Results

Potential for water-based CLGS energy extraction

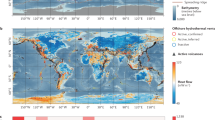

Mapping worldwide CLGS potentials requires first an analysis of local geothermal gradients and thermal conductivities that influence CLGS performance (refer to Supplementary Note 1 for detailed methodology description). Drawing on data from refs. 23,24,25,26,27, and digital resources [Mapping toolbox, MATLAB], we analyzed and integrated the datasets, producing an estimated temperature gradient map (Fig. 1a). The result is consistent with previous studies showing variations of ~10% to 20% in gradient magnitude over ~50 km to 100 km length scales23. Although more local variations, not captured here, are likely to be consequential, we expect the long length scale trends to be sufficient to estimate overall potential. The areas with the highest thermal gradients are distributed along the west coast of North America and South America, northeast Africa, Western Europe, and East Asia23.

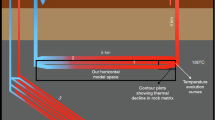

a Assembled global thermal gradient map showing the potential locations for geothermal energy harvesting (with data from refs. 23,24,25,26,27). Dark red regions show a very high thermal gradient ( > 80 °C/km), while the dark blue represents low thermal gradient areas (10 °C/km); b CLGS, which is similar to an underground heat exchanger extracting heat from a hot rock. As opposed to conventional geothermal systems, closed-loop geothermal is flexible on the type of working fluid20,54, enabling the formulation of fluids tailored for maximum heat extraction from a specific reservoir; c Electric output from a 12-laterals CLGS with 7 km depth at different geothermal gradient over 30 years. It shows a rapid reduction in power generation in the first 5 years due to fast energy depletion around the geo-loop, followed by a linear steady-state decrease in power output owing to a constant temperature gradient from the geo-loop toward the hot outer rock.

A typical closed-loop geothermal system is, in effect, an underground heat exchanger that extracts heat from hot rock (Fig. 1b). This approach enables the use of advanced fluids, such as thermal expansion fluids28,29,30,31, to extract more energy from the reservoir (Fig. 1b). The distance between the laterals may be optimized to harvest more energy and avoid overlap between the energy depletion zone around each lateral (Fig. S3). We conducted a sensitivity analysis on the number and length of laterals to identify optimal design parameters for maximizing the thermal performance of the CLGS (Fig. S4). Depending on the outlet temperature of the CLGS, the platform can be used for either electricity output (high-grade heat) or thermal output (low-grade heat).

Using momentum and energy conservation laws, we modeled non-isothermal fluid flow in a CLGS to evaluate its energy-extraction potential. By simulating a typical CLGS with water as the working fluid, we analyzed energy production behaviour over time under two distinct thermal gradients of 30 °C/km and 60 °C/km (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Note 1). We calculated the conversion of thermal energy to electricity using the organic Rankine cycle (ORC)32. Energy output declines substantially in the first five years due to the reliance on conduction through rock to the geo-loop (lacking convection present in conventional geothermal operations)33. The power output reaches a steady state condition after 5 years for both high and low thermal gradient cases (Fig. 1c). The average power generation for 30 °C/km and 60 °C/km is, respectively, 2.9 MWe and 10.8 MWe, equivalent to power generation in the fifth year. Economic viability thus depends on the geothermal gradient and any applicable alternative processes or fluids that could improve performance.

To realistically estimate CLGS performance on a global scale, the operating parameters must be assessed and optimized for individual reservoir conditions. The operating conditions, inlet temperature, and flow rate are the controllable variables that most influence performance in water-based CLGS (Fig. 2a)16. An optimum flow rate and inlet temperature maximize electricity output. The optimum occurs due to the tradeoff between thermal load, pumping power, and ORC efficiency. Generally, these optimum parameters depend on geothermal loop configuration, geo-fluid, and reservoir properties (refer to Figs. S5–S7).

a Impact of flow rate and inlet temperature on electricity output for a 7 km deep, 12 lateral CLGS at 30 °C/km reservoir; b Temperature output at different depths and thermal gradients showing an increase in output temperature with respect to increasing depth and thermal gradient; c Electric power output as a function of loop depth and thermal gradient; d Thermal output as a function of depth and thermal gradient.

We calculated the maximum output at different thermal gradients and depths by optimizing the operating conditions (Fig. 2b). As expected, the highest electricity output results from deep geothermal reservoirs with a high thermal gradient. Using water as the geo-fluid for a geothermal system with a thermal gradient of 100 °C/km and a depth of 7 km, the maximum surface fluid temperature, electrical power output, and thermal output are 205 °C, 20 MWe, and 132 MWth, respectively (Fig. 2b, c, d). The areas above the dashed curves in Fig. 2a–d indicate the economic ranges of depth and the thermal gradient, assuming a levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) of $200/MWhe. These ranges will vary, for instance, with electricity costs in different regions and seasons. With these approximate economic ranges, a global estimate of the CLGS can be calculated. These outputs are based on a single CLGS, which is equivalent to 13.4 GWe and 88.7 GWth per 1° latitude × 1° longitude at a depth of 7 km. While deeper drilling is possible, the average deep-drilling depth achieved in recent years is about 7 km, with greater depths posing safety challenges and exceeding industry norms34.

We performed depth-dependent local optimizations worldwide ( > 150,000 simulations) to understand the global CLGS energy production potential. Alongside our energy extraction analysis, we conducted techno-economic evaluations to provide a practical estimate of global power output, supporting broader technology adoption (see Supplementary Note 1). A full-capacity water-based CLGS can provide up to 9 TWe. By including the effects of regional temperature differences, this capacity exceeds the less accurate estimate we calculated based solely on average surface temperature of ~5 TWe. The estimated 9 TWe represents an upper bound, based on optimistic but thermodynamically plausible conditions. Key uncertainties—such as variability in thermophysical properties, heat losses, and geological heterogeneity—can markedly affect this global potential. Future work could incorporate probabilistic sensitivity analyses and region-specific modeling to refine these estimates.

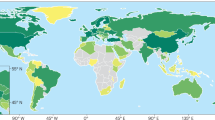

The global distribution of potential power output reflects the distribution of high thermal gradients (Fig. 3a), and we highlight the top 40 sites that this analysis indicates to be the most favourable for CLGS (Table S6). The optimal entrance depth for energy extraction around the globe varies depending on geothermal properties (Fig. 3b). The depth at which substantial electric output may be achieved in areas with a high thermal gradient can be as low as 2 km, and the minimum depth increases as the thermal gradient decreases. The regions with a low thermal gradient (< 30 °C/km) are not well suited21, without technological improvements that reduce drilling costs and/or more efficient extraction of heat.

Comparing the potential of CLGS to that of conventional geothermal systems is challenging, as the latter relies on exploring suitable underground reservoirs, which introduces substantial uncertainty35. As a result, estimates of conventional geothermal electricity potential vary widely, with realistic projections ranging from 70 GWe to 140 GWe36. The fundamental shift in CLGS design—operating independently of natural reservoirs—enables access to geothermal energy in regions previously deemed unsuitable. Accordingly, we estimate that the deployment of CLGS could increase the global geothermal electricity potential by up to two orders of magnitude, reaching the scale of tens of terawatts (TWe).

In geothermal reservoirs characterized by porous media and fluid-saturated formations, the presence of natural or induced background flow can substantially enhance convective heat transfer (Fig. S5). This additional backflow promotes more efficient thermal sweeping of the rock matrix, improving the overall heat extraction efficiency of CLGS. However, in our current analysis, we have not accounted for this background flow due to the inherent uncertainties in characterizing subsurface flow regimes and the challenges associated with identifying such complex, heterogeneous reservoirs at depth.

Depending on the depth of the reservoir, its thermal properties, and the design of surface facilities, closed-loop geothermal systems (CLGS) can be configured to either use heat directly or as an input for electricity generation. To explore this flexibility, we conducted a comprehensive thermal analysis of CLGS performance by evaluating the thermal output as a function of geofluid flow rate and inlet temperature. Our results indicate that for relatively shallow reservoirs (~3000 m), the outlet temperature at optimal flow conditions can reach approximately 120 °C, while deeper reservoirs (up to 7000 m) can achieve outlet temperatures exceeding 200 °C (Fig. S6).

In addition, we analyzed the thermal load capacity of water-based CLGS configurations as a function of rock thermal conductivity and geothermal gradient across a range of depths (Figs. S4 and S5). The results show a clear increase in thermal load with both increasing geothermal gradient and depth, with peak thermal loads reaching approximately 40 MWth at 7 km depth for high-conductivity formations. These findings show the potential for CLGS in direct-use heat applications, especially in moderate geothermal resources—either shallow formations or those with lower thermal conductivity—where the relatively low thermodynamic efficiency of small-scale ORC systems limits the viability of electricity generation. While this paper focuses primarily on the potential of CLGS for electricity production, our findings also highlight the broader versatility of CLGS, including the opportunity to use the heat generated directly in distributed-energy applications.

Global CLGS energy extraction using advanced fluids

To increase heat extraction and efficiency, alternative fluids such as supercritical CO2 and nanofluids have been explored30,31,37,38,39,40,41. Here, we focus on thermal expansion phase change slurries (PCSs), which enhance energy recovery using a hydroelectric turbine and an ORC power plant (Fig. 4a). PCSs enable two mechanisms: thermal expansion, to drive hydroelectric turbines and ORC plants (Figs. 4b and S7), and heat of fusion, to directly power ORC (Figs. 4c,d, S8)42. Deep reservoirs favour expansion due to buoyancy, maximizing electricity at peak outlet pressure (Figs. 4d and 5a). phase change material (PCM) expansion, ~5× more efficient than the heat of fusion43, is the preferred mechanism for deep geothermal power.

a Hydroelectric turbine combined with ORC power plant to generate electricity using high-pressure, high-temperature PCS output from CLGS; b Selection and optimization of phase change material for bespoke geothermal reservoir conditions. The phase change slurries can improve the CLGS performance with respect to water, and the efficiency enhancement is more pronounced at shallower geothermal reservoirs. The PCS properties need to be optimized for bespoke reservoir conditions; c Optimization for maximum electric and thermal output using max hydro-turbine and maximum thermosiphon mechanisms, respectively. We have showcased that PCS with lower melting temperature has different optimum operating conditions; d Performance comparison between water and phase change slurries using two distinct energy extraction mechanisms, latent heat and thermal expansion.

a Sensitivity analysis on PCS-based geo-loop performance for 15% deviation from a base case. The values are selected based on the typical paraffin PCM properties55. Thermal expansion, melting temperature, and viscosity are the three most important parameters to be considered when designing a PCS solution for CLGS; b PCS improvement compared to water showing an increased enhancement effect at weak geothermal reservoir; c ORC efficiency at different depths and thermal gradients, which shows a higher efficiency at strong geothermal reservoirs with a high thermal gradient; d Effects of PCS on geo-loop pressure demonstrating the thermal expansion impact on pressure gain at melting temperature.

For a global estimate of CLGS performance, understanding PCS behaviour across reservoir conditions is needed. We analyzed key PCS properties—melting temperature and thermal expansion–which impact performance differently at various depths (Fig. 4b—see Fig. S9 for the effects of other parameters). CLGS output scales with thermal expansion, while melting temperature has an optimal value at each depth, maximizing thermosiphon force. Optimal melting points for 3 km, 5 km, and 7 km reservoirs are 60 °C, 80 °C, and 100 °C, respectively. However, PCS benefits decline at greater depths as the high heat capacity of water outperforms PCS in energy extraction. At >400 °C, ORC efficiency is high, reducing PCS advantages over water (Fig. 5b,c). The demonstrated PCM improvement represents an optimized case for a typical reservoir, while our global PCS estimate optimizes operating parameters for diverse geothermal conditions worldwide. We conducted a sensitivity analysis and found the PCS properties most important for power generation, i.e., thermal expansion, melting point, and viscosity (Fig. 5a). Thermal expansion has a linear effect on CLGS performance, and an increase in thermal expansion—and PCS concentration – results in higher power generation (Fig. S7). Optimizing melting point based on the geothermal reservoir properties is crucial, as the PCS needs to melt in the horizontal laterals to enhance geothermal performance (Fig. 1b). Early melting, late melting, or non-melting makes the PCS ineffective on geothermal performance. Due to the large thermal resistance and friction factor in the laminar zone, viscosity needs to be optimized so the PCS flow regime is turbulent in the geo-loop to maximize energy extraction (refer to Fig. S10 for more details). Note that slurries in a turbine and in a geo-loop will likely present new challenges. The findings here motivate the testing of this approach30,40,44.

Optimized employment of PCMs for geothermal enhancement at various thermal gradients and depths shows notable improvement over water at typical geothermal reservoirs (3–5 km depth) or reservoirs with low thermal gradients (Fig. S11). PCMs have a small effect on geothermal energy extraction performance at ultra-deep geothermal systems with high thermal gradients. We observed up to 100% improvement in cases that would not have been economically viable without PCS (Fig. S11a). This means that PCS can increase applicability in geothermally weak reservoirs. The main reason for PCS improvement is the thermal expansion of the PCM. It results in a pressure gain of up to ~10 MPa during melting, which helps to improve energy extraction using a hydro-turbine (Figs. 5d, S9, and S12). The pressure gain occurs when the geothermal flow rate is optimized to ensure PCM melting. Moreover, PCS makes shallower geothermal energy extraction economically viable. Using PCS can also reduce the economic entrance depth for energy extraction (Fig. S11b). In geothermally weak regions, PCS has the remarkable potential to reduce entrance depths by up to 3 km, resulting in considerable savings on the substantial capital costs associated with drilling. Reducing entrance depths using PCS highlights its potential to mitigate a major barrier to CLGS development (high drilling costs) and the need for further research to derisk this approach31,40,44. Future studies are warranted to assess the feasibility of PCM applications under relevant geothermal conditions.

Evaluating CLGS in relation to wind and solar energy

The global estimate of potential energy harvesting using CLGS depends on LCOE45. The appropriate criteria for evaluating the fiscal performance of a CLGS can vary by region, local target operating conditions (e.g., thermosyphon-driven flow versus active pumping, as shown in Fig. S12), and may also evolve over time due to changing energy demands, public policy, or market conditions46. Our global estimate of full-capacity electricity reveals the impact of LCOE on power generation (Fig. 6a). The lower the economic LCOE, the lower the electricity production. We considered an LCOE of 200 $/MWhe as the basis for global CLGS energy production47. The CLGS cost depends primarily on the drilling cost and rate, and a higher drilling rate can reduce the upfront costs of CLGS16,48. While the considered LCOE is higher compared to other renewable energies, new drilling technologies such as electrical discharge drilling49 or plasma pulse geo drilling50 could reduce the upfront cost of CLGS. Using advanced thermal fluids such as PCS, it is possible to improve economic feasibility without increasing the levelized cost of energy. This can be accomplished by increasing power output and reducing entrance depths, improving the return on investment (Fig. 6a). The benefit is greater at larger LCOEs, because more weak geothermal areas become economically viable, and PCS offers improvements in weak geothermal reservoirs (Fig. 6a).

a The global CLGS energy extraction potential at different economic LCOE for water and PCS; the global estimate is based on the optimized operating condition at each location and depth and customized fluid for each CLGS, b Contribution of CLGS in the world renewable energy by 2050; comparing CLGS potential with solar and wind energy. It demonstrates the potential of the high contribution of CLGS to renewable energy production in the world.

Solar and wind are the leading renewable energy sources, contributing up to 90% of added renewable capacity51. Therefore, we have compared the CLGS global potential with respect to solar and wind energy capacity. Solar and wind offer low LCOEs (< 100 $/MWhe) but pose challenges for baseload energy production51. Despite power storage techniques, there remains a considerable gap between electricity demand and supply from solar and wind power1,52. Hence, there is an opportunity for dispatchable renewable energy sources, such as geothermal, even with higher LCOE rates. In many countries around the world, small land areas and high latitudes are limiting factors for reliance on solar systems since those areas result in larger interannual variations. Similarly, interannual variation of wind energy is high in many regions1. Our study shows that in many regions with the above-mentioned limitations, closed-loop geothermal would be attractive due to high subsurface thermal gradients. Examples include Japan, Germany, Iceland, Norway, Indonesia, Turkey, and Central American countries (Table S6). As such, CLGS with a larger LCOE can still contribute to world renewable energy production due to its reliability and dispatchability, which make it an attractive complementary source of energy to wind and solar. Widespread CLGS technology adoption holds promise for achieving lower LCOEs by streamlining capital costs and advancing the design and development of cutting-edge geo-fluids.

Geothermal energy currently provides <1% of the world’s total primary energy supply. However, it has the potential to play a much larger role in future global energy production. Comparing the potential contribution of CLGS to the world’s solar and wind energy production highlights the relative importance of each of these renewable energies (Fig. 6b). To compete with solar- and wind-predicted capacity, geothermal energy requires >2% growth per year. With a 3% growth rate per year, CLGS could produce 25% more electricity than predicted for wind power generation. Solar energy has the largest potential as a renewable energy source53.

While CLGS has the potential to become a substantial source of renewable energy, there are many challenges that must be addressed to realize this potential. Compared to wind and solar, CLGS is lower in technological readiness and will require more private and public investment to advance. The dispatchable nature of CLGS and the region-specific potential for this technology, can motivate such investment.

Discussion

We evaluated the potential global energy production by CLGS and assessed means to increase CLGS output and applicability. The map of energy production and the optimum entry depths for geothermal energy extraction show the areas where CLGS technology could best be adopted. We further highlight locations that could most benefit from this technology. In addition to the Ring of Fire surrounding the Pacific Ocean, we predict that locations in Asia, Africa, Europe, the United States, and Antarctica also have high geothermal potential. Considering a levelized cost of electricity of 200 $/MWhe, we showed that worldwide employment of water-based CLGS could produce up to 9 TWe at full capacity, which corresponds to 70% of current world electricity production. Achieving such a capacity requires selection of operating conditions and well configurations based on the local geothermal properties. The overall performance of CLGS could be improved substantially (to over 15 TWe) by using customized fluids such as phase change slurries and applying geothermal-driven hydro-turbine. A sensitivity analysis revealed the important PCS properties affecting CLGS performance and the corresponding non-linear trends to maximize energy production. This analysis showed that CLGS is likely to be more expensive than the leading renewable energy sources and further reductions in capital cost, especially the drilling cost, are needed. CLGS could complement the leading renewable sources of energy by providing power when they cannot, and fill the gap between energy demand and renewable capacity.

Methods

The CLGS model incorporates axial variations in fluid flow parameters along the loop and solves energy balance and momentum balance to generate profiles for temperature and pressure. The circulating fluid’s properties are temperature-dependent. The surrounding rock temperature is modeled as a linear function of depth, with the rock formation treated as a purely conductive medium, excluding convection effects. Consequently, the time-dependent thermal depletion of the rock is modeled using the established Ramey’s model. The fluid flow is assumed to run continuously, exchanging heat with the surrounding formation.

To calculate axial temperature, pressure, and—when applicable—liquid mass fraction (e.g., for PCS), the CLGS is discretized into equal-sized elements along the pipe length and solved using the Euler method with specified temperature and pressure boundary conditions. The ORC system employed in this study includes a heat exchanger to transfer heat from the geo-loop outlet to the ORC working fluid, a steam turbine with an efficiency of 85%, a condenser to dissipate heat from the turbine outlet at 25 °C, and a pump with an efficiency of 75%. The pinch point in the heat exchanger is set at 5 °C. The subsurface and surface facility models are fully integrated to enable the dynamic optimization of the entire cycle, leveraging both the hydro-turbine and the ORC system. The model’s robustness and accuracy are validated against literature data.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and the Supplementary Information. Source data are available through Figshare at https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Source_data_for_figures_on_the_closed-loop_geothermal_system/29710493?file=56713457.

Code availability

The code used to perform the simulations in this study is available at https://github.com/zargartalebi/CLGS under an MIT license. The code is written in MATLAB 2025 and can be executed using the CLGS_Run.m script. All key parameters and functions are clearly annotated to ensure reproducibility.

References

Tong, D. et al. Geophysical constraints on the reliability of solar and wind power worldwide. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–12 (2021).

Bogdanov, D. et al. Radical transformation pathway towards sustainable electricity via evolutionary steps. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–16 (2019).

Li, M. et al. Renewable energy quality trilemma and coincident wind and solar droughts. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 661 (2024).

Anderson, A. & Rezaie, B. Geothermal technology: trends and potential role in a sustainable future. Appl. Energy 248, 18–34 (2019).

van der Zwaan, B. & Dalla Longa, F. Integrated assessment projections for global geothermal energy use. Geothermics 82, 203–211 (2019).

Bouckaert, S. et al. Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector (International Energy Agency, 2021).

Giardini, D. Geothermal quake risks must be faced. Nature 462, 848–849 (2009).

Yuan, B. & Wood, D. A. A holistic review of geosystem damage during unconventional oil, gas and geothermal energy recovery. Fuel 227, 99–110 (2018).

Knoblauch, T. A. & Trutnevyte, E. Siting enhanced geothermal systems (EGS): Heat benefits versus induced seismicity risks from an investor and societal perspective. Energy 164, 1311–1325 (2018).

Soltani, M. et al. Environmental, economic, and social impacts of geothermal energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 140, 110750 (2021).

Teske, S. Achieving the Paris climate agreement goals: Global and regional 100% renewable energy scenarios with non-energy GHG pathways for +1.5 C and +2 C (Springer Nature, 2019).

Blackwell, D. D., Negraru, P. T. & Richards, M. C. Assessment of the enhanced geothermal system resource base of the United States. Nat. Resour. Res. 15, 283–308 (2006).

Higgins, B., Muir, J., Scherer, J. & Amaya, A. GreenFire energy closed-loop geothermal demonstration at the Coso geothermal field. GRC Transactions 43 (2019).

Toews, M., Riddell, D., Vany, J. & Schwarz, B. Case study of a multilateral closed-loop geothermal system. In Proc. World Geothermal Congress, Reykjavik, Iceland, April 26–May 2 (2020).

Jolie, E. et al. Geological controls on geothermal resources for power generation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 324–339 (2021).

Malek, A. E., Adams, B. M., Rossi, E., Schiegg, H. O. & Saar, M. O. Techno-economic analysis of Advanced Geothermal Systems (AGS). Renew. Energy 186, 927–943 (2022).

Vargas, C. A., Caracciolo, L. & Ball, P. J. Geothermal energy as a means to decarbonize the energy mix of megacities. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 66 (2022).

Soltani, M. et al. A comprehensive study of geothermal heating and cooling systems. Sustain. Cities Soc. 44, 793–818 (2019).

Sun, F., Yao, Y., Li, G. & Li, X. Geothermal energy development by circulating CO2 in a U-shaped closed loop geothermal system. Energy Convers. Manag. 174, 971–982 (2018).

Beckers, K. F. et al. Techno-economic performance of closed-loop geothermal systems for heat production and electricity generation. Geothermics 100, 102318 (2022).

Malek, A. E., Adams, B., Rossi, E., Schiegg, H. O. & Saar, M. O. In 46th Annual Stanford Geothermal Workshop (SGW, 2021).

van Oort, E., Chen, D., Ashok, P. & Fallah, A. In SPE/IADC International Drilling Conference and Exhibition (OnePetro).

Aghahosseini, A. & Breyer, C. From hot rock to useful energy: a global estimate of enhanced geothermal systems potential. Appl. Energy 279, 115769 (2020).

Pollack, H. N., Hurter, S. J. & Johnson, J. R. Heat flow from the Earth’s interior: analysis of the global data set. Rev. Geophys. 31, 267–280 (1993).

Cermak, V. & Rybach, L. Terrestrial heat flow in Europe. Vol. 58 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Majorowicz, J. & Wybraniec, S. New terrestrial heat flow map of Europe after regional paleoclimatic correction application. Int. J. Earth Sci. 100, 881–887 (2011).

Le Gal, V. et al. Heat flow, morphology, pore fluids and hydrothermal circulation in a typical Mid-Atlantic Ridge flank near Oceanographer Fracture Zone. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 482, 423–433 (2018).

Royon, L. & Guiffant, G. Forced convection heat transfer with slurry of phase change material in circular ducts: a phenomenological approach. Energy Convers. Manag. 49, 928–932 (2008).

Delgado, M., Lázaro, A., Peñalosa, C. & Zalba, B. Experimental analysis of the influence of microcapsule mass fraction on the thermal and rheological behavior of a PCM slurry. Appl. Therm. Eng. 63, 11–22 (2014).

Soni, V. et al. Evaluation of a Microencapsulated Phase Change Slurry for Subsurface Energy Recovery. Energy Fuels 35, 10293–10302 (2021).

Soni, V. et al. Performance analysis of phase change slurries for closed-loop geothermal system. Renew. Energy. 216, 119044 (2023).

Ahmadi, A. et al. Applications of geothermal organic Rankine Cycle for electricity production. J. Clean. Prod. 274, 122950 (2020).

Song, X. et al. Numerical analysis of the heat production performance of a closed loop geothermal system. Renew. Energy 120, 365–378 (2018).

Wang, H. et al. Deep and ultra-deep oil and gas well drilling technologies: progress and prospect. Nat. Gas. Ind. B 9, 141–157 (2022).

Ciriaco, A. E., Zarrouk, S. J. & Zakeri, G. Geothermal resource and reserve assessment methodology: overview, analysis and future directions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 119, 109515 (2020).

Bertani, R. In Proceedings of the international conference on national development of geothermal energy use, Slovakia.

Randolph, J. B. & Saar, M. O. Combining geothermal energy capture with geologic carbon dioxide sequestration. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38 (2011).

Brown, D. W. In Proceedings of the twenty-fifth workshop on geothermal reservoir engineering. Stanford University. 233-238.

Hu, Z. et al. Thermal and fluid processes in a closed-loop geothermal system using CO2 as a working fluid. Renew. Energy 154, 351–367 (2020).

McPhee, H. et al. Rheological behavior of phase change slurries for thermal energy applications (Langmuir, 2022).

Darzi, A. et al. Biofuel processing in a closed-loop geothermal system. Appl. Energy 376, 124188 (2024).

Li, B.-H., Castillo, Y. E. C. & Chang, C.-T. An improved design method for retrofitting industrial heat exchanger networks based on Pinch Analysis. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 148, 260–270 (2019).

Ksayer, E. B. L. Design of an ORC system operating with solar heat and producing sanitary hot water. Energy Procedia 6, 389–395 (2011).

Saber, S. et al. Thermophysical behavior of phase change slurries in the presence of charged particles. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 653, 129967 (2022).

Park, S., Langat, A., Lee, K. & Yoon, Y. Measuring the impact of risk on LCOE (levelized cost of energy) in geothermal technology. Geotherm. Energy 9, 27 (2021).

Aldersey-Williams, J. & Rubert, T. Levelised cost of energy–A theoretical justification and critical assessment. Energy Policy 124, 169–179 (2019).

Barros, J. J. C., Coira, M. L., de la Cruz López, M. P. & del Caño Gochi, A. Probabilistic life-cycle cost analysis for renewable and non-renewable power plants. Energy 112, 774–787 (2016).

Beckers, K. F. & Johnston, H. E. Techno-Economic Performance of Eavor-Loop 2.0.

Mao, X., Almeida, S., Mo, J. & Ding, S. The state of the art of electrical discharge drilling: a review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 121, 1–23 (2022).

Ezzat, M. et al. in 48th European Conference on Plasma Physics. 316.

Yao, Y., Xu, J.-H. & Sun, D.-Q. Untangling global levelised cost of electricity based on multi-factor learning curve for renewable energy: Wind, solar, geothermal, hydropower and bioenergy. J. Clean. Prod. 285, 124827 (2021).

Shaner, M. R., Davis, S. J., Lewis, N. S. & Caldeira, K. Geophysical constraints on the reliability of solar and wind power in the United States. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 914–925 (2018).

IEA. World Energy Outlook. (2024).

Nalla, G., Shook, G. M., Mines, G. L. & Bloomfield, K. K. Parametric sensitivity study of operating and design variables in wellbore heat exchangers. Geothermics 34, 330–346 (2005).

Aftab, W. et al. Phase change material-integrated latent heat storage systems for sustainable energy solutions. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 4268–4291 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from Eavor Technologies, as well as the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada through the Alliance and Discovery programs. Support from the Canada Research Chairs program is also greatly appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Z. and A.D. designed and carried out all simulations, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. A.K. assisted with manuscript editing. D.S. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and assisted during manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: financial support from Eavor Technologies Inc.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Somaparna Ghosh. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zargartalebi, M., Darzi, A., Kazemi, A. et al. Closed-loop geothermal system is a potential source of low-carbon renewable energy. Commun Earth Environ 6, 812 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02729-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02729-9