Abstract

Coastal sea ecosystems are increasingly threatened by global change and human activities. Our understanding of these changes is limited, especially in dynamic coastal regions lacking thick sediment sequences. Iron-manganese concretions, biogeochemical precipitates on the seafloor, grow in non-depositional coastal areas and record numerous marine processes and environmental variability. Establishing reliable geochronology for these precipitates has been challenging. We combine anthropogenic lead accumulation, cobalt chronometry, and radiocarbon dating to develop a high-resolution Bayesian age model for a rapidly growing iron-manganese concretion from the Baltic Sea. The concretion core formed ca. 11,000 cal. BP, with overgrown material showing successively younger ages from 7500 years ago to recent decades. Analyses of microstructure, magnetic microscopy, and bulk mineral magnetic properties, trace elements, and iron isotopic composition reveal that the concretion records environmental variability over the past 7000 years. Our study may serve as a benchmark for paleoenvironmental records from coastal iron-manganese concretions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coastal sea ecosystems worldwide, including the Baltic Sea, are under increasing pressure from human activities such as overfishing, pollution, habitat alteration, and eutrophication, and associated seafloor deoxygenation1,2,3,4. Climate change is also impacting coastal sea ecosystems, resulting in increased sea surface temperatures, reduced sea ice, more frequent marine heatwaves, acidification, and enhanced oxygen deficiency4,5,6,7. Understanding the amplification of these pressures over time is crucial for the development of effective management and protective strategies of coastal sea areas. Systematic oceanographic studies have been conducted in many coastal sea areas over the past several decades; however, this period is heavily influenced by human activity. In order to assess the current state of coastal sea ecosystems in the context of anthropogenic pressures and climate influence over longer time scales, it is necessary to analyze geological records2,8,9.

Thick sediment sequences deposited continuously over centennial and longer time scales are the key archives of environmental and climatic changes in the deep sea; however, such deposits are generally lacking in dynamic coastal sea areas, where sediment deposition typically is patchy and discontinuous10,11. This condition is unfortunate, because coastal sea areas play a key role in the transformation, retention, and recycling of riverine suspended particles, and dissolved and particulate nutrient pools on their passage to the open sea12,13. The low sedimentation rates and erosive conditions in coastal sea areas, however, favor the formation of iron-manganese concretions, making them useful recorders of coastal environmental variability and anthropogenic pressures14,15,16,17,18.

Iron-manganese concretions commonly occur in coastal sea areas around the world19,20,21,22. In the Baltic Sea, they cover approximately 10% of the seafloor at depths of 20–100 meters23,24. These concretions are biogeochemical precipitates primarily composed of poorly crystalline iron (Fe) and manganese (Mn) (oxyhydr)oxides that form on the seafloor in areas that are predominantly oxic and where no net sediment deposition takes place. In the Baltic Sea, such conditions are typically encountered on the exposures of silty clays of the previous lacustrine phase of the Baltic Sea basin17,18,25. The shallow-water concretions display various shapes and microstructures that reflect the hydrodynamic and sedimentation conditions of the formation environment18,23,26,27. The primary pathway for Fe and Mn to the Baltic Sea is riverine influx26,28, with possible additional inputs from benthic efflux and lateral transport from adjacent oxygen-deficient areas29,30, as well as diffusion from the reactive Fe-containing lacustrine sediments31. The poorly crystalline Fe-Mn oxide phases composing the concretions are effective at scavenging a wide range of cations and anions from the seawater32. In addition, microbes that oxidize and reduce Fe and Mn inhabit the concretions and have a role in the precipitation and dissolution of these oxides, influencing also the cycling of other metals33,34. Consequently, the structure as well as elemental and isotopic composition of iron-manganese concretions serve as a valuable record of many marine processes and highlight their potential as sources of economically important elements.

The Baltic Sea iron-manganese concretions have been studied for their records of anthropogenic metal loading, climate-driven erosive influx from land, and saline influx from the North Sea, using rare earth element (REE) contents, and Ce, Sr, Nd, Os, and Pb isotopes15,16,35,36. Additionally, the interplay of concretion formation conditions and their magnetic properties has been previously studied in the Baltic Sea18. However, only two studies have provided reliable geochronologies for Baltic Sea concretions based on radioisotopes 226Ra and 210Pb37,38, which is crucial for understanding the environmental drivers and their variability through time. Based on the previous studies, iron-manganese concretions in the Baltic Sea grow relatively quickly, at a rate of several millimeters per thousand years, compared to a few millimeters per million years for iron-manganese crusts and polymetallic nodules on ocean floors39. Therefore, Baltic Sea iron-manganese concretions offer significantly better temporal resolution than their oceanic counterparts.

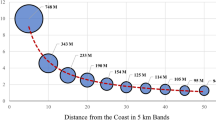

In this study, we show that a rapidly growing shallow-marine iron-manganese concretion from the northern coastal area of the Gulf of Finland, Baltic Sea (Fig. 1), can record environmental information in areas where other sedimentary archives are scarce. We combine two independent geochronological methods (radiocarbon dating and anthropogenic lead accumulation) along with a supporting method based on cobalt accumulation (Co-chronometer) to construct a Bayesian probabilistic age model for the concretion. We then show that temporal changes in the concretion microstructure, mineral magnetic properties, trace element behavior, and iron isotopic composition are linked to local and basin-scale environmental forcing.

Left: Sampling site (orange point) of the crust-discoidal iron-manganese concretion (MGBC-2021-4-1) off the city of Espoo, in the northern Gulf of Finland, within the eastern parts of the Baltic Sea. Base map: ESRI Inc. (Redlands) Ocean Basemap 2018. Baltic Sea bathymetric data: EMODnet Bathymetry 2018137 Right: photo and X-Ray microtomography image of the studied concretion sample from Wasiljeff et al. 18. The tomography image’s color scheme from blue to red indicates a change from less dense to increased density. The orange box indicates the studied growth lobe and the dashed red box the QDM field of view in Fig. 3.

Results and Discussion

Baltic Sea iron-manganese concretion

The Baltic Sea iron-manganese concretions occur in three endmember morphotypes: crust, discoidal, and spheroidal, with the shape controlled by hydrodynamic and sediment depositional conditions in the near-bottom environment18,26,27,40. The internal structure of the Baltic Sea iron-manganese concretions is typically characterized by alternating Fe and Mn-rich layers and accompanied by structural discontinuities and pores, resulting from variability in the formation environment18,23,27. In this study, we investigate a single growth lobe of a crust-discoidal concretion from the Gulf of Finland with two distinct growth phases that contain typical Baltic Sea concretion microstructures18 (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S1). In the first growth phase, encrusting the core, there is a thick, massive Fe-rich layer, which is followed by mainly anisotropic directional Mn-rich structures (Supplementary Fig. S1a) intergrown by thin and fragmentary Fe-rich laminae (Supplementary Fig. S1c) and occasional non-directional structures (Supplementary Fig. S1b). The Mn-rich growth predominantly connects with the subsequent Fe-rich layers. This growth phase is 3–4 mm thick and has occasional clay and silt-sized Si and Al-containing detrital minerals associated with the extensive pore space surrounding the Mn-rich branches, which is typical of detritus readily accumulating in topographic lows in the pore space41. The magnetic mineral concentration (as indicated by the intensity of sample surface magnetic fields carrying a saturation remanence or |B | IRM) in this growth phase is comparably low (Supplementary Table 1), and the mineral populations are characterized by biogenic magnetite18 (Fig. 2). The anisotropic directional Mn-rich growth pattern has been associated with relatively calm formation environment which occurs in relatively slow pace compared to the non-directional growth42.

Element map of Fe, Mn, and Si of the studied iron-manganese concretion (MGBC-2021-4-1) growth lobe together with simplified microstratigraphical features (anisotropic/non-directional, laminated)18 as well as the interpreted growth phases 1 and 2. Corresponding magnetic mineral populations (detrital, biogenic, hard) and mean coercivities of the respective distributions for the growth phases are derived from Wasiljeff et al. 18. The modeled mean concretion age and growth rate (GR) are depicted as a function of concretion depth with solid lines, whereas the shaded area represents the 5–95 % percentile. The lead age tie points (Pb), radiocarbon ages (14C), and the used cobalt chronometer (Co) sample approximate middle depths are indicated in the figure. Corresponding relative change in sea level is based on shoreline displacement reconstructions from the northern middle parts of the Gulf of Finland, near the concretion collection site89. |B | IRM, χARM/IRM, Ce/Ce* and δ56FeSW curves are presented as a function of age. The shaded areas around the curves are 2σ uncertainty. Pollen-based annual mean temperature record provided by Seppä et al. 138 is shown as a dark red curve. Holocene Thermal Maximum (HTM), Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA), and Little Ice Age (LIA) are indicated in the figure.

The second growth phase is characterized by increased frequency of alternating and interfingering Fe- and Mn-rich layers and overall thicker Fe-rich layers (Fig. 2). These Fe-rich layers are mottled with Mn phases and interbedded with increasingly non-directional Mn-rich growth patterns. This second phase is ca. 7 mm thick and extends to the outer rim of the concretion. The increased anisotropy and non-directional patterns originate from patched growth in various locations on the same surface43. This patchiness results from different factors such as bioturbation or physical sediment mixing, from obstacles caused by trapped detrital minerals or random growth processes18,44. The anisotropic directional and non-directional growth patterns have also been associated with abiotic chemically oscillating reactions accompanied by decomposition of biomass in the inter-pore space45, as well as with biomineralization46,47,48. The precipitation of Fe-rich layers intermixed with Mn mottles reflects a more turbulent environment and strong near-bottom flow conditions49, which is supported by the slightly increased amount and grain size of intercalated detrital minerals in these layers, as well as by an increase in overall magnetic mineral concentration (increase in |B | IRM values) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1). This is consistent with the presence of discrete, strongly magnetic sources both at the Fe-Mn layer interfaces and scattered within the Mn-rich zones in these layers (Fig. 3) and a more prominent contribution from the detrital magnetic component (Fig. 2). Such iron-rich laminations have further been associated with intermittently less oxic/mildly reducing bottom-water conditions43. In dynamic (fluctuating oxygen and flow regime) bottom conditions, Mn and Fe remobilize differently, leading to retention of Fe in the accumulated layers and outflux of Mn14,22,27,50.

QDM magnetic field mapping overlay on top of the Fe and Mn element map from ref. 18. The QDM field map of a saturation isothermal remanent magnetization shows magnetic sources along the Fe-Mn interfaces and scattered within the Mn-rich growth zones.

Age model

We used radiocarbon (14C) to constrain the time during which the studied concretion had precipitated. Initial trials involved accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS)-14C dating of the NaOH-soluble fraction of concretion material51. The NaOH-soluble fraction yielded consistent ages (~2000 yr BP) across different sampling depths in the concretion (Supplementary Table 2), suggesting that the fraction was dominated by modern organic material that had migrated through the porous concretion. Consequently, to constrain the maximum age of the concretion, we utilized the residual fraction of NaOH extraction as recommended for low carbon samples52, focusing on the core (12–15 mm concretion depth) and the first alternating Fe- and Mn-rich growth layers (7–11 mm depth), which contained sufficient material for the analysis (Fig. 2). The AMS-14C ages of the extraction residuals were 10490 ± 210 BP for the core and 6850 ± 480 BP for the first growth layers, and the mean calibrated ages were 11041 BP and 6815 BP, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). To determine the calibrated ages, we used OxCal 4.4.453 with IntCal20 curve54, and assumed a conservative reservoir age of 900 ± 50055.

The Pb contents (range: 3.8–420 ppm) in the studied concretion covary with the Fe/Mn ratio (Fig. 4), which is expected, since increased Pb incorporation has been associated with the presence of poorly-crystalline Fe oxide phases and vernadite (δ-MnO2) in growth zones showing high Fe/Mn ratios in marine iron-manganese concretions and polymetallic nodules27,56. On the other hand, while the Pb enrichment factor (EFPb) variability (range: 0–25) follows a similar trend to the Pb contents and Fe/Mn ratios (range: 0.02–10.7), the EFPb peak profile gets less synchronized with the other two variables from around 5.8 mm towards the outer edge (Fig. 4). These peaks of higher Pb enrichment align well with declines in 206Pb/207Pb and 208Pb/207Pb ratios (Fig. 4). The 206Pb/207Pb values range from 1.22 to 1.54 and the 208Pb/207Pb from 2.39 to 2.85. Overall, the Pb isotope ratios recorded across the studied concretion reflect the 206Pb/207Pb and 208Pb/207Pb values obtained from the Finnish soils57,58,59, with some overlap from Swedish and Norwegian soils (Supplementary Fig. S4). This suggests that most of the lead incorporated in the concretion originates from the immediate catchment area, which is considered a major source of the concretion building materials via river runoff and groundwater seepage18,26,27,40,60. While the variance in stable Pb isotope ratios recorded in the concretion can largely be explained by changes in the supply of concretion building materials from the catchment area, the distinctive pattern and overlap of higher Pb enrichment with the stable Pb isotope peaks support the interpretation of anthropogenic contribution to these intervals.

Iron to manganese (Fe/Mn) ratio, Pb content, lead enrichment (EFPb), 206Pb /207Pb and 208Pb /207Pb ratios from the outer edge next to the core of a Gulf of Finland iron-manganese concretion (MGBC-2021-4-1). Identified anthropogenic lead peaks are indicated in the figure from I to IV. The orange line is LOWESS fit of the data.

This is reflected in the EFPb profile that follows those obtained previously from Baltic Sea sediments in the Archipelago Sea (Haverö)8 and from lake sediments in Sweden (Kassjön, Koltjärnen, and Kalven)61,6 allowing the assignment of age tie points. We selected four intervals that are consistent with the other records (Figs. 4 and 5). We interpret that the first clear increase from the background values at around 5.8 mm (base of interval IV), accompanied by a decline in the 206Pb/207Pb and 208Pb/207Pb ratios, indicates the onset of anthropogenic Pb accumulation and corresponds to the beginning of the Roman pollution at around 0 AD63. During this interval, the Pb content reaches a peak of approximately 200 ppm (EFPb 10). Importantly, sources from the Iberian Peninsula partially overlap with our Pb isotope ratio data, supporting the assignment of the peak to Roman pollution (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Lead enrichment (EFPb) profile of a Gulf of Finland iron-manganese concretion (MGBC-2021-4-1) compared to pollution Pb reference curves from Swedish lakes Kassjön, Koltjärnen, and Kalven61,62, and from Haverö in the Archipelago Sea area, eastern Baltic Sea8. A detailed inset of unfiltered EFPb data is shown from the outermost ~100 µm of the concretion and compared to Kassjön pollution Pb. In the inset, the 1900 minima and the leaded gasoline peak of 1980 are indicated.

Upward from interval IV, we found a clear consistency in the peak profile between our EFPb pattern (Fig. 5) and the pollution Pb enrichments in Swedish lakes and in Haverö in the Archipelago Sea8,61,62. We identify the onset of medieval pollution at around 900 AD (base of interval III)64, followed by the medieval pollution maximum at around 1200 AD55,63,64, the pollution peak of 1530 AD (base of interval II), and the 1350 and 1600 AD pollution minima8, which are previously reported age constraints within the Baltic Sea. Finally, the top of interval II represents the pre-industrial peak (1750 AD) observed in lake Koltjärnen61. The assignment of interval II to this time frame is supported by Pb isotope values aligning with the isotopic composition of the Sjangeli area in Sweden (Supplementary Fig. S3), where mining operations commenced in 1690s65. As the last tie point, we used the onset of modern Pb pollution, which we designated to 1900 AD (interval I and Fig. 5 inset). Our results support the idea of using Pb accumulation and Pb isotopes as an independent dating tool in Baltic Sea coastal iron-manganese concretions, as originally proposed by Liebetrau et al. 15.

Cobalt accumulation has been extensively used in the deep ocean and shallow-water environments to date iron-manganese concretions under the assumption of a constant Co intake rate from ambient seawater66,67,68. Despite Co-chronometers being originally developed to take advantage of the hydrogenous component of Co specifically, it has been shown that 98–99% of the total Co content of various Fe-Mn precipitates is hosted by the hydrogenous Fe-Mn oxides, mainly vernadite32,69,70. Leaching studies of iron-manganese concretions from the Gulf of Finland are consistent with these findings17. Thus, the whole rock analyses can approximate the hydrogenous Co content accurately, which would be indistinguishable from leachable Co within analytical uncertainty71.

Several empirical equations which relate the growth rate (GR) to Co contents have been developed67,72,73, but ages derived from them only represent minimum values since the method does not detect hiatuses during the growth process nor considers variable Co flux to the seafloor74. Additionally, while all the equations share a similar mathematical form:

Or

their coefficients a and b are different, which could yield significantly differing age estimates for the same sample75, and may have regional constraints. Also, various other factors influence the incorporation of Co to Fe-Mn precipitates besides the growth rate and variable Co flux, such as variations in surface complexation of Co to different Fe and Mn oxides, the oxidation state of the (biogenic) Mn oxides, as well as dilution effects by other minerals (as Co mainly resides in the Mn-rich phase)32,76,77. In this study, we used Eq. (2), where [Co]n is the Mn-normalized Co content, to reduce errors from contamination by other minerals76.

The previous Co-chronometer methods allow only for relative age determination if absolute age tie points are missing. To address this limitation, we utilized a Bayesian probabilistic modeling approach to construct an age model for the studied concretion. Jiang et al. 78 derived a discrete analytical Bayesian model to estimate Co content at different depths of a deep ocean polymetallic nodule, based on an age calibration dataset. We continued this work by deriving a continuous analytical form of the model and incorporating the sampled Co and Mn contents into the model. Additionally, we included sampling errors from the analyzed samples, sampling depths, and calibration age tie points. The analytical continuous form preserves the interpretability of the parameters and enables us to simultaneously fit both the sampled data and the calibration data points. As calibration data, we used the calibrated radiocarbon ages and pollution Pb age tie points (Supplementary Table 4) which were fit together with the [Co]n, determined from the geochemical data of sample slices (Supplementary Table 3).

The bulk geochemical data used to construct the age model were obtained from relatively thick slices, which integrate multiple Fe- and Mn-rich growth layers. Across these alternating layers commonly observed in the Baltic Sea concretions, the mineralogy of Fe- and Mn-rich phases appears consistent27. At the time of sampling, bottom water was oxic and pH was commonly around 7–834, and it is assumed that such oxic, non-reducing conditions prevailed throughout most of the observation period, allowing the formation and relatively continuous concretion growth. Despite the slightly changing redox conditions during the growth process and the likely but minor variability in water Co concentrations79 between deeper and shallower water growth phases, it is reasonable to assume Mn oxide reactive surface area to be the primary limiting factor for the accumulation of Co. This is influenced, e.g., by Mn mineral crystallinity, oxidation state, competing ions, and pH77,80,81,82. While microbial processes may introduce additional complexity77, assuming first-order kinetics in Co accumulation remains a sufficient approximation for our modeling purposes in this study. Consequently, the [Co]n values were modelled to follow a data-driven exponentially decaying trend (3) as a function of concretion depth, derived from a fit of the Pb and radiocarbon age tie points. Although a relatively simplistic approach, it effectively captures the average growth trend at moderate resolution, while accounting for intrinsic high-resolution fluctuation within the model’s confidence intervals. The function for calibration ages was derived by integrating growth rates (2) over different depths after inserting (3). Thus, the tie point ages can be written as a function of depth (4).

Coefficients a and b were discussed above. \(\beta\) describes [Co]n decay rate, and \(\alpha\) the [Co]n at the surface. Sampling depths and measured Mn and Co contents were modeled using a measurement error model. These variables were treated as unknowns with errors computed based on the sampled mean and their deviation.

The model was implemented in the Stan programming language, and sampling was performed using the built-in Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampler83. Both equations were simultaneously fitted, which constrained α and β by both (3) and (4), limiting the number of possible solutions. Data was scaled before fitting for numerical stability. The sampler was run with 4 chains with 1000 samples per chain. The success of sampling was evaluated with Stan’s diagnostics tools. Detailed model and prior specification, and diagnostics are provided in the Supplementary Note 2.

The model (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S5a) suggests that the alternating Fe and Mn-rich layers of the concretion started to accumulate between 7600 and 7500 years ago, approximately coinciding with the marine flooding and establishment of the modern brackish-water Baltic Sea ca. 7600 years ago84. This translates into growth rates of 1–4 µm yr-1 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S5b). Previous growth rate estimates for Baltic Sea concretions, determined by the accumulation of anthropogenic metals14,26, cosmogenic isotopes85, 226Ra/Baex ratio37, 210Pb dating38, and a laboratory microcosm experiment34, range from 1.7 to 60 µm yr-1, and are thus consistent with our results, increasing the confidence in the constructed age model.

Basin scale environmental change as recorded by the concretion

The first growth phase (ca. 7500–3100 years ago) of the studied iron-manganese concretion is characterized by Mn-rich anisotropic directional patterns that result from comparably slow growth, as also indicated by the modeled mean growth rate of 1–2 µm yr-1 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S5b). The growth start was roughly coincident with the marine flooding and establishment of modern brackish-water conditions in the Baltic Sea ca. 7600 years ago84. This environmental change resulted in strongly increased primary productivity and organic deposition84,86,87, which triggered enhanced microbial activity88 and (bio)mineralization at the concretion formation site. The second growth phase (ca. 3100 years ago to present) is dominated by alternating Fe- and Mn-rich banding, indicating growth under more variable conditions and at the slightly higher rate of 2–4 µm yr-1 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S5b). By 3100 years ago, the relative sea level at the sampling site fell by ca. 20 m due to glacio-isostatic uplift89 to roughly the 60 m depth, which is the depth of storm wave base in the Gulf of Finland90. This change led to intensified flow velocities, intermittent sediment transport to the site, and variable but generally improved oxygenation, causing accelerated concretion growth. These more dynamic environmental conditions are reflected both in the microstructural characteristics and proxy data of the second growth phase of the studied concretion.

The cerium anomaly (Ce/Ce*) values decrease from 1.05 at ca. 7000 years ago to 0.55 by 5000 years ago, indicating a steady decline in seafloor oxygenation (Fig. 2). This deteriorating trend reflects the influence of the Holocene Thermal Maximum (HTM; 8000–4500 years ago), during which widespread hypoxia emerged in the Baltic Sea9,91. During that time, the coevally increasing total magnetic mineral concentration (|B | IRM) and χARM/IRM ratio (Fig. 2, Supplementary Tables 1 and 3) indicate increased contribution from single domain (SD)-sized (30–80 nm) magnetite particles that are associated with a biogenic origin and expansion of oxygen deficient bottom-waters adjacent to Baltic Sea iron-manganese concretion formation sites18. This is further corroborated by the higher mean coercivity of ~90 mT of the biogenic magnetite (associated with increased elongation of the magnetite crystal) during the growth phase (Fig. 2), consistent with the commonly observed biogenic hard component in aquatic settings92, reflecting a less-oxygenated environment93. The cerium anomaly values rebound back to a more oxic level of 0.85 at 2000–1500 years ago, when further increased hydrodynamic energy levels at the seafloor due to the continued relative sea level fall surpassed the waning influence of the HTM. The higher energy levels are supported by the coarsening of magnetic mineral grain size (a decrease in the χARM/IRM ratio) and an increase in total magnetic mineral concentration (|B | IRM; Fig. 2, Supplementary Tables 1 and 3), which subsequently remains at a generally higher level. The growing contribution from a widely dispersed low-coercivity magnetic component further suggests increased incorporation of detrital material after ca. 2000 years ago, peaking at approximately 1000 BP (Fig. 2). Similarly, the lower coercivity of the biogenic component could be attributed to both the collapse of magnetofossil chains and alterations in magnetite crystal morphology93,94, driven by more dynamic and oxic environmental conditions, respectively. The temporarily improved oxygenation is followed by a subsequent, steeper decrease in Ce/Ce* values to 0.58 over the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA; 1350–750 years ago), indicating rapid decline of seafloor oxygen levels9,91. Atmospheric temperatures play a crucial role in driving primary productivity and organic sedimentation, which fuel oxygen consumption and the development of hypoxia on the seafloor95,96,97. During the MCA, the amount of detrital magnetic minerals increased as shown by the coeval decrease in χARM/IRM ratio and increase in magnetic mineral concentration (Fig. 2; Supplementary Tables 1 and 3), likely reflecting increased exposure to storm events and wave-induced sediment flows due to reduced ice-cover in the warmer climate98.

The magnitude of Ce/Ce* ratio is not necessarily related to only the oxygen conditions of the environment, but can be influenced by other factors, including the presence of organic matter99 and the growth rate of the concretion27. However, in our proxy record, the variability of the ratio is mirrored in the fluctuations of the reconstructed paleoseawater δ56FeSW values (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 3). The calculated δ56FeSW values range between +0.03 ± 0.07 and +0.36 ± 0.08‰ (Fig. 2). These are typical values obtained in the Baltic Sea region, where the heavier endmember is similar to dissolved Fe in the upper oxidized water column (+0.3‰) and approaches dissolved Fe imported by rivers (+0.53 ‰), whereas the lighter endmember (~−0.59 to ~+0.02‰) is likely from reductive dissolution processes in the sediments100,101,102. Given the largely covarying long-term evolution of δ56FeSW along Ce/Ce* during concretion growth (Fig. 2), we interpret that both proxies mainly reflect changes in varying oxygen and redox conditions at or near the formation site, linked to basin-scale environmental forcings. Nevertheless, Ce/Ce* ratio should be interpreted only through relative changes when inferring trends in the varying redox and oxygen conditions.

The transition to the Little Ice Age (LIA; 600–300 years ago) is recorded by the increased Ce/Ce* and δ56FeSW values and thus the improvement of seafloor oxygenation (Fig. 2), caused by decreased primary productivity attributed to lower temperatures9,96. However, the relative increase in SD magnetite suggests that oxygen-deficient conditions were retained at least periodically in the proximity of the concretion formation site (Fig. 2). Our records of oxygen variability during the 7500 years of concretion growth underscore the susceptibility of coastal regions to hypoxia that can be exacerbated by both natural and anthropogenic factors.

In addition to oxygen, anthropogenic Pb pollution is consistently recorded in the concretion during the past 2000 years (Fig. 5). During the first centuries AD, the surge in Pb pollution resulted from increased metallurgical activity in the Roman Empire, especially around the Iberian Peninsula103,104. Also, early mining activities in Sweden105 may have contributed to the onset of pollution in our record. From then on, our Pb enrichment data provide a high-resolution archive of human impact in the northern Baltic Sea region. The Pb enrichments are linked to advances in mining and extraction techniques as well as regional population expansions, and the decreases associated with economic crises, wars, disease, and famine15,106, with the last mentioned modulated especially in the Nordic countries by LIA and other climatic disruptions107.

Conclusions

We demonstrate that shallow-water iron-manganese concretions from the Baltic Sea serve as valuable archives of global to basin-scale paleoenvironmental changes and anthropogenic impact. We constructed the most detailed age model for a rapidly growing shallow-water iron-manganese concretion to date, utilizing a Bayesian probabilistic model that integrates radiocarbon dating, pollution Pb age tie points, and cobalt chronometry. Our findings highlight the vulnerability of coastal environments to changes in atmospheric circulation and temperature, and glacio-eustatic uplift, which affected bottom-water oxygenation and hydrodynamic energy levels in the northern Baltic Sea over the past 7000 years. The variability of Pb enrichment in the concretion provides a high-resolution record of human activity in the region since Roman times.

Methods

Study site

The bedrock of the region consists of Paleoproterozoic crystalline basement of mainly quartz diorite and granodiorite that outcrops locally on the seafloor108. The area was previously covered by the Fennoscandian continental ice sheet, which retreated northwest from the area ca. 12700 calendar years ago109. The retreating ice-margin left behind till and glacial outwash deposits in a deep ice-contact lake, where glaciolacustrine varved silt and clay, and successive postglacial lacustrine silty clay, were deposited as conformable drapes of comparably uniform thickness11,110. Beginning at ca. 7600 years ago, the thresholds to the Atlantic in the Kattegat were inundated due to the glacioeustatic sea-level rise, resulting in the establishment of brackish-water conditions and drift-type deposition of organic-rich mud11,98. Due to the rapid glacioisostatic rebound, the relative sea level in the study area has fallen ca. 30 m since the onset of the brackish-water conditions89, and the fall continues today at the rate of 2.5 mm yr-1 111. Sediment distribution on the present seafloor is patchy; roughly a third is composed of bedrock and till, a third of glaciolacustrine and postglacial lacustrine silty clay, and a third of organic-rich brackish-water mud. The near-bottom water temperature typically ranges 2–5 °C, while the salinity ranges 5–9 due to the high riverine runoff from the large catchment area and the long distance to the narrow connections to the North Sea in the Kattegat112. Dissolved oxygen concentration in the bottom water occasionally decreases to hypoxic levels at water depths exceeding 60 m113.

Water depth at the study site is 53 m. The near-bottom water was well oxygenated with the dissolved oxygen concentration of 8.5 mg dm−3 at the time of sampling. Near-bottom water temperature was 4.2 °C and salinity was 7.6.

Sample collection and preparation

Our research cruises with R.V. Geomari to the Gulf of Finland during the years 2021 and 2022 produced abundant collections of iron-manganese concretions of various sizes and morphotypes. One representative iron-manganese concretion was selected for the current study (Fig. 1). MGBC-2021-4-1 is a crust-like concretion with discoidal growth bands around the nucleus extending approximately horizontally along the sediment-water interface. The sample was collected using a box corer from a location (N 59°57.929 E 24°46.726) where silty clay glacial rhythmite sediments of the previous lacustrine phase of the Baltic Sea basin were exposed on the seafloor covered by a 1-cm veneer of fine sand. Immediately after collection, the sample was flushed with ultrapure water (MilliQ) and frozen with dry ice. The frozen sample was later freeze-dried at the Geological Survey of Finland (GTK) laboratory in Espoo, Finland. The drying made the sample fragile, and hence it was impregnated with epoxy resin (Struers EpoFix) after the collection of samples for radiocarbon dating. The resin-embedded concretion was cut in slices perpendicular to the growth axis with a precision saw. One discoidal growth lobe was selected for the analysis and cut in half, where the other half was prepared as an epoxy button and thin section, and the other half was cut into 8 pieces for trace element and Fe isotope determinations as well as rock magnetic measurements.

Microstructural features

Concretion microstructure and growth features were investigated from a polished epoxy button with a JEOL JSM-7100F (JEOL Ltd, Japan) Schottky field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) equipped with an Oxford Instruments EDS-spectrometer X-Max 80 mm2 (SDD) at 20 kV acceleration voltage and a 1.3 nA probe current at the GTK. EDS mapping and image processing were conducted using AZtec software (Oxford Instruments plc, UK).

Geochemistry

Major (Si, Al, Mn, P, K, Ca, Fe, Na, Mg) and trace (V and Ba) element analyses were undertaken with a JEOL JXA-iHP200F (JEOL Ltd, Japan) electron microprobe analyzer (FEG-EMPA) at the GTK, using the WDS (wavelength-dispersive) technique. Accelerating voltage and beam current were 15 kV and 10 nA, respectively. EMPA spots were carefully placed to avoid any obvious pores or detrital mineral grains. However, due to the high porosity of the sample, the totals of quantified measurements with EMPA were around 60 wt-%, which were then normalized to 100%. To obtain a sufficient average surface area for measurement despite the pores, a defocused beam set to 20 µm was used in the analysis. Further defocusing was avoided to prevent intensity loss due to Bragg defocusing114. A defocused beam has a lower energy density, resulting in a stable count per second acquisition over the measurement time, typically in the range of a few minutes. Analytical results have been corrected using the XPP online correction program115. Natural and synthetic minerals and metals were used as standards. The EMPA data were used only as an internal standard (major elements) in this study and will not be discussed further.

Contents of 55Mn, 57Fe, and 208Pb were determined in situ with a single collector high resolution ICP mass spectrometer (AttoM, Nu Instruments Ltd, UK) coupled with a 193 nm solid state deep UV laser ablation system (New Wave Research Inc., USA) at the GTK. While other elements were analyzed, only Mn, Fe, and Pb data are discussed in this study. Helium was used as a carrier gas and argon as a makeup gas, mixed with the carrier gas before entering the ICP. Laser operating conditions were 5–10 Hz repetition rate, and 1.25 J cm−2 fluence. Data were acquired with time-resolved analysis (TRA) in continuous transects using a letterbox aperture (10 × 155 µm), where ablation spots were rasterized perpendicular to the growth axis at 1 µm s−1. Each line was split after acquisition of 1400 µm and included a 20 s background for a gas blank before the data acquisition. The analyses targeted sites near or at EMPA spot locations. In the calibration, EMPA analyses were used as an internal standard, whereas FeMnOx-1116 was selected as the primary external standard in association with one quality control standard (Nod-A-1 by the United States Geological Survey, USGS), which was measured in the same session before and after each set of unknowns. The standards were pressed nanopellets. Data reduction consisted of background selection and integration, filtering of outliers, and smoothing the data over a 20-point moving average, followed by the quantification using known concentrations of the standard. RSD (%) of the quality control measurements for the selected elements was <3 % and RE (%) was <5%.

Stable Pb isotope ratios (208Pb, 207Pb, 206Pb, and 204Pb) were determined with the LA-ICP-MS. Laser operating conditions were 10 Hz repetition rate, and 2.17 J cm−2 fluence. Data were acquired with TRA in transects using 25 µm spots where ablation spots were lined perpendicular to concretion growth axis, next to the LA-ICP-MS trace element and EMPA transects. Each line was split after the acquisition of 250 µm. Isotope values were corrected using standard bracketing to USGS Nod-P-1. Repeated standard measurements (Nod-P-1: 208Pb/204Pb 38.0352 ± 0.4808, 207Pb/204Pb 15.5062 ± 0.3597, 206Pb/204Pb 18.2580 ± 0.3227) approach the GeoREM117 recommended values for Nod-P-1 (208Pb/204Pb 38.6555, 207Pb/204Pb 15.6276, 206Pb/204Pb 18.6949) and have RE (%) and RSD (%) <2.4 %. Values for 204Pb were corrected for the interference of 204Hg using 202Hg.

Whole rock analyses were undertaken on the cut epoxy-impregnated slices. The slices were first treated with acetone and concentrated HNO3, followed by H2O2 to digest the epoxy residues from the samples. Samples were further digested to a clear solution using a mixture of concentrated HNO3-HF and aqua-regia on a hot plate for several days. Samples were finally dissolved in 2% HNO3, and split of the sample was further diluted 4000–40000 times with 2% HNO3. The analyses were carried out with the same AttoM SC-ICP-MS at low mass resolution (Δm/m = 300) using a standard Meinhard nebulizer. The trace element measurements were performed in deflector scan mode, measured in 5 blocks, with 500 sweeps per block. On peak dwell time was 10 ms. Three multi-elemental solutions were prepared using single- and multi-elemental solutions at 100 and 1000 ppm from LabKingTM. Concentration of the standards were 0,01 and 0,1 ppb for As, Au, B, Ba, Be, Bi, Cd, Ce, Co, Cs, Cu, Dy, Er, Eu, Ga, Gd, Ge, Hf, Hg, Ho, In, Ir, La, Lu, Mn, Mo, Nb, Nd, Ni, Ni, Os, Pb, Pd, Pt, Rb, Re, Rh, Ru, Sb, Sc, Se, Si, Sm, Sn, Sr, Ta, Tb, Te, Th, Ti, Tl, Tm, U; 0,02 and 0,1 ppb for Cr, and V; 0,1 and 1 ppb for Li and 10 and 100 ppb for Al, Ca, Fe, Mg, Na, P and S. Additional solution was made for Si, Zn and Mn with concentration of 100 and 1000 ppb. This set of calibration multi-elemental solutions, together with blanks, was measured at the beginning and end of the run. The concentrations in ppb were calculated with NuQuant using blank and external drift by regression through the two multi-element standards and the blank.

Iron isotopes were determined for aliquots of the multi-element samples. Iron was first eluted following the column chromatography method described in ref. 118 and then analyzed following119. Iron was separated from matrix elements using anion exchange chromatography (Bio-Rad; AG1-X8 200–400 mesh) in an HCl medium. The digested sample was loaded in 0.5 mL of concentrated HCl, where iron was quantitatively retained on the resin. Matrix elements were eluted sequentially with 5 mL of concentrated HCl, followed by 22 mL of 4 M HCl, and finally 1 mL of 0.4 M HCl. Iron was subsequently eluted from the resin using 15 mL of 0.4 M HCl, a process that was repeated twice. After evaporating to dryness, concentrated HNO3 was added directly to the residue, followed by the addition of Milli-Q water. The purified fractions were analyzed using a Neptune Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) multi-collector (MC)-ICP-MS at a commercial laboratory (ALS Scandinavia, Lund, Sweden) in high-resolution static mode. The 54(Fe and Cr), 56Fe, 57Fe, 58(Fe and Ni), 60Ni and 62Ni were collected. The instrument was equipped with a micro-concentric nebulizer and a tandem cyclonic/Scott double-pass spray chamber. Instrumental mass biases were corrected by sample-standard bracketing using IRMM-014 CRM120,121, with an internal standard (Ni) added to all samples to correct for instrumental drift. The data correction process, outlined in ref. 122, included baseline subtraction (120 s before each measurement), calculation of ion beam intensity ratios, and filtering of outliers using a 2σ test. Iron isotope data are expressed as δ56Fe, relative to the IRMM-014 standard:

Rock magnetism and magnetic microscopy

Quantum diamond microscopy (QDM) maps of sample thin section surface magnetic fields were captured at the Harvard Paleomagnetics Lab after imparting a near-saturating 0.3 T isothermal remanent magnetization (IRM) out of the sample plane. This field is sufficient to saturate magnetite-carried remanence and likely represents saturation for the whole sample since no significant regions of the map showed magnetization in other directions. Due to the unidirectionality of the magnetization, the surface magnetic field strength should be a close proxy for the underlying magnetization intensity123. Maps were acquired in projected magnetic microscopy mode under a 0.9 mT bias field reversed over the course of the measurement for an effective bias field of ~400 nT124.

The bulk magnetic properties of the concretion have been extensively studied in Wasiljeff et al. 18. For this study, additional measurements were conducted for the sample slices at the HelLabs Geophysics Research Laboratory of the University of Helsinki, Finland. In summary, an anhysteretic remanent magnetization (ARM) was imparted using a peak field of 100 mT and a direct current bias field of 0.1 mT with an AGICO LDA-3A (Advanced Geoscience Instruments Company, Czech Republic). An IRM up to 3 T was imparted with a MMPM10 Pulse Magnetizer (Magnetic Measurements, UK). Both the ARMs and IRMs were demagnetized using alternating fields (AF), and remanences were measured with a 2 G Enterprises (WSGI, USA) superconducting rock magnetometer (model 755). Magnetic grain size dependent parameter, χARM/IRM, was calculated125. The magnetic mineral populations in the concretion determined with coercivity spectra unmixing are composed of three populations, which are detrital magnetite, biogenic magnetite, and a high coercivity magnetic mineral, goethite, published in ref. 18. The magnetic mineralogy, however, is dominated by magnetite based on low- and high-temperature thermomagnetic measurements and transmission electron microscopy imaging18, and thus the χARM/IRM mainly reflects relative changes in magnetic mineral grain size, namely the abundance and lack of single-domain (30–80 nm) magnetite.

Radiocarbon dating

Samples of approximately 90 mg for accelerator mass spectrometry radiocarbon (AMS-14C) dating were drilled from the internal crosscut using a handheld multitool, creating even pits of about 3–4 mm, starting from the concretion core (12–15 mm from the edge) and moving towards the outer rim. External surface material was avoided to mitigate potential contamination. NaOH leaching to extract soluble and insoluble fractions and their AMS-14C dating were conducted at the Poznań Radiocarbon Laboratory, Poland126. NaOH-soluble fraction age was determined for all samples and residual age for the core and the first alternating Fe- and Mn-rich growth layers (7–11 mm depth). The two obtained residual ages were used for constructing an age-depth model for the studied concretion.

Pollution lead

The pollution Pb ages were derived from high-resolution Pb content profiles acquired with the LA-ICP-MS system at the GTK, which was then compared to varved sediments from the Archipelago Sea8 and some Swedish lakes61,62. Following ref. 8, we assumed a conservative 50-year uncertainty to the Pb constraints. Additionally, a 100 µm depth uncertainty was assigned for the measurements.

Variations in Pb accumulation is influenced e.g. by changes in the supply and origin (natural vs. anthropogenic) of Pb as well as the iron-manganese concretion growth rate. In this study, we estimated the amount of anthropogenic Pb with enrichment factor (EF) determined here as the ratio of Pb to the Fe-Mn matrix as follows:

where [Pb], [Fe] and [Mn] are contents of Pb, Fe, and Mn measured in the Fe-Mn growth layers, respectively. The [Pb]/([Fe] + [Mn])0 ratio is a mean value taken from the growth layers between ca. 10 and 6 mm from the edge and represent pre-anthropogenic Pb accumulation. Lead was normalized to the authigenic Fe-Mn matrix because, when the variability of the element of interest is predominantly governed by the authigenic matrix, it serves as a more suitable reference method compared to a conservative element127.

Redox conditions and paleoseawater iron isotope composition

Subtle changes in bottom-water oxygenation can be inferred from iron-manganese concretion recorded cerium anomaly (Ce/Ce*)78, which was defined here after128 as

where N is normalization to PAAS129.

Fluctuations in δ56Fe values are shown to be unrelated to concretion growth rates or mineralogical alterations in deep ocean settings and are primarily governed by diagenetic, terrigenous and hydrothermal inputs130,131. In the context of the shallow Baltic Sea, where hydrothermal inputs are not expected and the northern parts function as a large estuary, the coastal filter controls the terrigenous input of Fe to the basin13,132, and part of this Fe pool contributes to the precipitation of iron-manganese concretions. In boreal regions, one major route of Fe to estuaries is river transport, in dissolved and particulate forms, both as Fe-organic carbon complexes and Fe (oxy)hydroxides102,133. Since the Fe isotopic composition is largely controlled by the catchment area (origin of Fe and amount of organic matter) as well as redox conditions in sediments134,135, these properties are reflected in the composition of Baltic Sea water dissolved Fe from which the concretions precipitate. To calculate the iron isotopic composition of the source water, we followed Horner et al. 130 who suggested a fractionation factor between seawater (SW) and iron-manganese concretion (FeMn) during uptake as

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available in the Supplementary Information and in Zenodo136.

Code availability

The age model code is available at https://github.com/ArttuD/AgeModel.git.

References

Halpern, B. S. et al. A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science 319, 948–952 (2008).

Rabalais, N. N., Cai, W.-J., Carstensen, J., Conley, D. J. & Fry, B. Eutrophication-driven deoxygenation in the coastal ocean. Oceanography 27, 172–183 (2015).

HELCOM. State of the Baltic Sea. Third HELCOM holistic assessment 2016–2021. Baltic Sea Environment Proceedings no. 194. (2023).

Varela, R., de Castro, M., Dias, J. M. & Gómez-Gesteira, M. Coastal warming under climate change: Global, faster and heterogeneous. Sci. Total Environ. 886, 164029 (2023).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. & Bruno, J. F. The impact of climate change on the world’s marine ecosystems. Science 328, 1523–1528 (2010).

Breitburg, D. et al. Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science 359, eaam7240 (2018).

Smith, K. E. et al. Biological impacts of marine heatwaves. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15, 119–145 (2023).

Jokinen, S. A. et al. A 1500-year multiproxy record of coastal hypoxia from the northern Baltic Sea indicates unprecedented deoxygenation over the 20th century. Biogeosciences 15, 3975–4001 (2018).

Andrén, E. et al. Medieval versus recent environmental conditions in the Baltic Proper, what was different a thousand years ago? Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 555, 109878 (2020).

Nittrouer, C. A. & Wright, L. D. Transport of particles across continental shelves. Rev. Geophys. 32, 85–113 (1994).

Virtasalo, J. J., Kotilainen, A. T., Räsänen, M. E. & Ojala, A. E. K. Late-glacial and post-glacial deposition in a large, low relief, epicontinental basin: the northern Baltic Sea. Sedimentology 54, 1323–1344 (2007).

Dürr, H. H. et al. Worldwide typology of nearshore coastal systems: Defining the estuarine filter of river inputs to the oceans. Estuaries Coasts 34, 441–458 (2011).

Asmala, E. et al. Efficiency of the coastal filter: Nitrogen and phosphorus removal in the Baltic Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 62, S222–S238 (2017).

Hlawatsch, S. et al. Fast-growing, shallow-water ferro-manganese nodules from the western Baltic Sea: origin and modes of trace element incorporation. Mar. Geol. 182, 373–387 (2002).

Liebetrau, V. et al. Radiometric growth rate and Pb isotope evolution of Mn/Fe precipitates from the SW-Baltic Sea. Z. Für Angew. Geol. 2, 195–215 (2004).

Bock, B., Liebetrau, V., Eisenhauer, A., Frei, R. & Leipe, T. Nd isotope signature of Holocene Baltic Mn/Fe precipitates as monitor of climate change during the Little Ice Age. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 2253–2263 (2005).

Zhamoida, V. et al. Ferromanganese concretions of the eastern Gulf of Finland – Environmental role and effects of submarine mining. J. Mar. Syst. 172, 178–187 (2017).

Wasiljeff, J. et al. Morphology-dependent magnetic properties in shallow-water ferromanganese concretions. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 25, e2023GC011366 (2024).

Ku, T. L. & Glasby, G. P. Radiometric evidence for the rapid growth rate of shallow-water, continental margin manganese nodules. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 36, 699–703 (1972).

Baturin, G. N. Distribution of elements in ferromanganese nodules in seas and lakes. Lithol. Miner. Resour. 54, 362–373 (2019).

Kaikkonen, L. & Virtanen, E. A. Shallow-water mining undermines global sustainability goals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 37, 931–934 (2022).

Shulga, N., Abramov, S., Klyukina, A., Ryazantsev, K. & Gavrilov, S. Fast-growing Arctic Fe–Mn deposits from the Kara Sea as the refuges for cosmopolitan marine microorganisms. Sci. Rep. 12, 21967 (2022).

Glasby, G. P. et al. Environments of formation of ferromanganese concretions in the Baltic Sea: a critical review. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 119, 213–237 (1997).

Kaikkonen, L., Virtanen, E. A., Kostamo, K., Lappalainen, J. & Kotilainen, A. T. Extensive coverage of marine mineral concretions revealed in shallow shelf sea areas. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, (2019).

Marcus, M. A., Manceau, A. & Kersten, M. Mn, Fe, Zn and As speciation in a fast-growing ferromanganese marine nodule. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 3125–3136 (2004).

Zhamoida, V. A., Butylin, W. P., Glasby, G. P. & Popova, I. A. The nature of ferromanganese concretions from the eastern Gulf of Finland, Baltic Sea. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 14, 161–176 (1996).

Wasiljeff, J. et al. Mineral phases and growth conditions of morphologically diverse shelfal ferromanganese concretions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 400, 227–247 (2025).

Winterhalter, B. Ferromanganese concretions in the Gulf of Bothnia. in Geology and Geochemistry of Manganese III (eds. Varentsov, I. M. & Graselly, G.) 227–254 (Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, 1980).

Widerlund, A. & Ingri, J. Redox cycling of iron and manganese in sediments of the Kalix River estuary, Northern Sweden. Aquat. Geochem. 2, 185–201 (1996).

Pakhomova, S. V. et al. Fluxes of iron and manganese across the sediment–water interface under various redox conditions. Mar. Chem. 107, 319–331 (2007).

Virtasalo, J. J. & Kotilainen, A. T. Phosphorus forms and reactive iron in lateglacial, postglacial and brackish-water sediments of the Archipelago Sea, northern Baltic Sea. Mar. Geol. 252, 1–12 (2008).

Huang, S. & Fu, Y. Enrichment characteristics and mechanisms of critical metals in marine Fe-Mn crusts and nodules: a review. Minerals 13, 1532 (2023).

Sujith, P. P. & Gonsalves, M. J. B. D. Ferromanganese oxide deposits: Geochemical and microbiological perspectives of interactions of cobalt and nickel. Ore Geol. Rev. 139, 104458 (2021).

Majamäki, R. et al. Microbially-enhanced growth and metal capture by ferromanganese concretions in a laboratory experiment. Geobiology 23, e70010 (2025).

Amakawa, H., Ingri, J., Masuda, A. & Shimizu, H. Isotopic compositions of Ce, Nd and Sr in ferromanganese nodules from the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, the Baltic and Barents Seas, and the Gulf of Bothnia. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 105, 554–565 (1991).

Peucker-Ehrenbrink, B. & Ravizza, G. Continental runoff of osmium into the Baltic Sea. Geology 24, 327–330 (1996).

Liebetrau, V. et al. 226Raexcess/Ba growth rates and U-Th-Ra-Ba systematic of Baltic Mn/Fe crusts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 66, 73–83 (2002).

Grigoriev, A. G., Zhamoida, V. A., Gruzdov, K. A. & Krymsky, R. S. Age and growth rates of ferromanganese concretions from the Gulf of Finland derived from 210Pb measurements. Oceanology 53, 345–351 (2013).

Hein, J. R. & Koschinsky, A. 13.11 - Deep-ocean ferromanganese crusts and nodules. in Treatise on Geochemistry (Second Edition) (eds. Holland, H. D. & Turekian, K. K.) 273–291 (Elsevier, Oxford, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-095975-7.01111-6.

Winterhalter, B. Ferromanganese concretions in the Gulf of Bothnia. In Mineral resources of the Baltic sea – Exploration, exploitation and sustainable development (eds. Harff, J., Emelyanov, E., Schmidt-Tome, M. & Spiridonov, M.) (2004).

Josso, P. et al. Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic paleoceanography from north-east Atlantic ferromanganese crust microstratigraphy. Mar. Geol. 422, 106122 (2020).

Friedrich, G. & Schmitz-Wiechowski, A. Mineralogy and chemistry of a ferromanganese crust from a deep-sea hill, central Pacific, “Valdivia” cruise VA 132. Mar. Geol. 37, 71–90 (1980).

Guan, Y., Sun, X., Ren, Y. & Jiang, X. Mineralogy, geochemistry and genesis of the polymetallic crusts and nodules from the South China Sea. Ore Geol. Rev. 89, 206–227 (2017).

Sutherland, K. M., Wankel, S. D., Hein, J. R. & Hansel, C. M. Spectroscopic insights into ferromanganese crust formation and diagenesis. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst.21, e2020GC009074 (2020).

Papineau, D. et al. Abiotic chemically oscillating reactions make patterns in deep–sea ferromanganese nodules and crusts. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 35, 55–61 (2025).

Blöthe, M. et al. Manganese-cycling microbial communities inside deep-sea manganese nodules. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 7692–7700 (2015).

Heim, C., Quéric, N.-V., Ionescu, D., Schäfer, N. & Reitner, J. Frutexites-like structures formed by iron oxidizing biofilms in the continental subsurface (Äspö Hard Rock Laboratory, Sweden). PLOS ONE 12, e0177542 (2017).

Scopelliti, G. & Russo, V. Petrographic and geochemical characterization of the Middle‒Upper Jurassic Fe–Mn crusts and mineralizations from Monte Inici (north-western Sicily): genetic implications. Int. J. Earth Sci. 110, 559–582 (2021).

Ren, Y. et al. Nano-mineralogy and growth environment of Fe-Mn polymetallic crusts and nodules from the South China Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, (2023).

Heller, C., Kuhn, T., Versteegh, G. J. M., Wegorzewski, A. V. & Kasten, S. The geochemical behavior of metals during early diagenetic alteration of buried manganese nodules. Deep Sea Res. Part Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 142, 16–33 (2018).

Olsson Ingridu. A warning against radiocarbon dating of samples containing little carbon. Boreas 8, 203–207 (1979).

Olsen, L. et al. AMS radiocarbon dating of glacigenic sediments with low organic carbon content - An important tool for reconstructing the history of glacial variations in Norway. Nor. Geol. Tidsskr. 81, (2001).

Bronk-Ramsey, C. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 51, 337–360 (2009).

Reimer, P. J. et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62, 725–757 (2020).

Lougheed, B. C. et al. Bulk sediment 14C dating in an estuarine environment: How accurate can it be?. Paleoceanography 32, 123–131 (2017).

Guan, Y. et al. Fine scale study of major and trace elements in the Fe-Mn nodules from the South China Sea and their metallogenic constraints. Mar. Geol. 416, 105978 (2019).

Reimann, C. et al. Lead and lead isotopes in agricultural soils of Europe – The continental perspective. Appl. Geochem. 27, 532–542 (2012).

Reimann, C., Birke, M., Demetriades, A., Filzmoser, P. & O’Connor, P. Chemistry of Europe’s Agricultural Soils, Part A. (Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Hannover, 2014).

Reimann, C., Birke, M., Demetriades, A., Filzmoser, P. & O’Connor, P. Chemistry of Europe’s Agricultural Soils, Part B. (Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Hannover, 2014).

Callender, E. & Bowser, C. J. Freshwater ferromanganese deposits. in Au, U, Fe, Mn, Hg, Sb, W, and P Deposits (ed. Wolf, K. H.) vol. 7 341–394 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1976).

Bränvall, M.-L., Bindler, R., Emteryd, O. & Renberg, I. Four thousand years of atmospheric lead pollution in northern Europe: a summary from Swedish lake sediments. J. Paleolimnol. 25, 421–435 (2001).

Bindler, R. Contaminated lead environments of man: reviewing the lead isotopic evidence in sediments, peat, and soils for the temporal and spatial patterns of atmospheric lead pollution in Sweden. Environ. Geochem. Health 33, 311–329 (2011).

Zillén, L., Lenz, C. & Jilbert, T. Stable lead (Pb) isotopes and concentrations – A useful independent dating tool for Baltic Sea sediments. Quat. Geochronol. 8, 41–45 (2012).

Lougheed, B. C. et al. Using an independent geochronology based on palaeomagnetic secular variation (PSV) and atmospheric Pb deposition to date Baltic Sea sediments and infer 14C reservoir age. Quat. Sci. Rev. 42, 43–58 (2012).

Awebro, K. Tre gruvfält i norr - Gustafsfält, Kalix kopparbruk och Sjangeli. Stud. Lapplandia 10, 49–72 (1989).

Halbach, P., Segl, M., Puteanus, D. & Mangini, A. Co-fluxes and growth rates in ferromanganese deposits from central Pacific seamount areas. Nature 304, 716–719 (1983).

Manheim, F. T. & Lane-Bostwick, C. M. Cobalt in ferromanganese crusts as a monitor of hydrothermal discharge on the Pacific sea floor. Nature 335, 59–62 (1988).

Szamałek, K., Uścinowicz, S. & Zglinicki, K. Rare earth elements in Fe-Mn nodules from southern Baltic Sea – a preliminary study. Biul. Państw. Inst. Geol. 199 (2018).

Koschinsky, A. & Halbach, P. Sequential leaching of marine ferromanganese precipitates: Genetic implications. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 5113–5132 (1995).

Koschinsky, A. & Hein, J. R. Uptake of elements from seawater by ferromanganese crusts: solid-phase associations and seawater speciation. Mar. Geol. 198, 331–351 (2003).

Josso, P. et al. Improving confidence in ferromanganese crust age models: A composite geochemical approach. Chem. Geol. 513, 108–119 (2019).

Frank, M., O’Nions, R. K., Hein, J. R. & Banakar, V. K. 60 Myr records of major elements and Pb–Nd isotopes from hydrogenous ferromanganese crusts: reconstruction of seawater paleochemistry. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 1689–1708 (1999).

McMurtry, G. M., VonderHaar, D. L., Eisenhauer, A., Mahoney, J. J. & Yeh, H.-W. Cenozoic accumulation history of a Pacific ferromanganese crust. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 125, 105–118 (1994).

Park, J., Jung, J., Ko, Y., Lee, Y. & Yang, K. Reconstruction of the paleo-ocean environment using mineralogical and geochemical analyses of mixed-type ferromanganese nodules from the tabletop of Western Pacific Magellan seamount. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 24, e2022GC010768 (2023).

Yi, L. et al. The potential of marine ferromanganese nodules from Eastern Pacific as recorders of Earth’s magnetic field changes during the past 4.7 Myr: A geochronological study by magnetic scanning and authigenic 10Be/9Be dating. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125, e2019JB018639 (2020).

Ren, X., Hein, J. R., Yang, Z., Xing, N. & Zhu, A. Controls on cobalt concentrations in ferromanganese crusts from the Magellan seamounts, west Pacific. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, (2024).

Shi, M. et al. The mechanism of cobalt enrichment by biogenic manganese oxides with different average oxidation states. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 13, 115412 (2025).

Jiang, X. D. et al. Abyssal manganese nodule recording of global cooling and Tibetan Plateau uplift impacts on Asian aridification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL096624 (2022).

Pempkowiak, J., Chiffoleau, J.-F. & Staniszewski, A. The vertical and horizontal distribution of selected trace metals in the Baltic Sea off Poland. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 51, 115–125 (2000).

Crowther, D. L., Dillard, J. G. & Murray, J. W. The mechanisms of Co(II) oxidation on synthetic birnessite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 47, 1399–1403 (1983).

Yin, H. et al. Co2+-exchange mechanism of birnessite and its application for the removal of Pb2+ and As(III). J. Hazard. Mater. 196, 318–326 (2011).

Zhao, H., Feng, X., Lee, S., Reinhart, B. & Elzinga, E. J. Sorption and oxidation of Co(II) at the surface of birnessite: Impacts of aqueous Mn(II). Chem. Geol. 618, 121281 (2023).

Carpenter, B. et al. Stan: A probabilistic programming language. J. Stat. Softw. 76, 1–32 (2017).

Virtasalo, J. J. et al. Base of brackish-water mud as key regional stratigraphic marker of mid-Holocene marine flooding of the Baltic Sea Basin. Geo-Mar. Lett. 36, 445–456 (2016).

Anufriev, G. S. & Boltenkov, B. S. Ferromanganese nodules of the Baltic Sea: Composition, helium isotopes, and growth rate. Lithol. Miner. Resour. 42, 240–245 (2007).

Andrén, E., Andrén, T. & Kunzendorf, H. Holocene history of the Baltic Sea as a background for assessing records of human impact in the sediments of the Gotland Basin. The Holocene 10, 687–702 (2000).

Tuovinen, N., Virtasalo, J. J. & Kotilainen, A. T. Holocene diatom stratigraphy in the Archipelago Sea, northern Baltic Sea. J. Paleolimnol. 40, 793–807 (2008).

Lyra, C., Sinkko, H., Rantanen, M., Paulin, L. & Kotilainen, A. Sediment bacterial communities reflect the history of a sea basin. PLOS ONE 8, e54326 (2013).

Seppä, H., Tikkanen, M. & Shemeikka, P. Late-Holocene shore displacement of the Finnish south coast: diatom, litho- and chemostratigraphic evidence from three isolation basins. Boreas 29, 219–231 (2000).

Kohonen, T. & Winterhalter, B. Sediment erosion and deposition in the western part of the Gulf of Finland. Baltica 12, 53–56 (1999).

Häusler, K. et al. Mid- to late Holocene environmental separation of the northern and central Baltic Sea basins in response to differential land uplift. Boreas 46, 111–128 (2017).

Egli, R. Characterization of individual rock magnetic components by analysis of remanence curves, 1. Unmixing natural sediments. Stud. Geophys. Geod. 48, 391–446 (2004).

Chang, L. et al. Indian Ocean glacial deoxygenation and respired carbon accumulation during mid-late Quaternary ice ages. Nat. Commun. 14, 4841 (2023).

Heslop, D., Roberts, A. P. & Chang, L. Characterizing magnetofossils from first-order reversal curve (FORC) central ridge signatures. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 15, 2170–2179 (2014).

Virtasalo, J. J., Leipe, T., Moros, M. & Kotilainen, A. T. Physicochemical and biological influences on sedimentary-fabric formation in a salinity and oxygen-restricted semi-enclosed sea: Gotland Deep, Baltic Sea. Sedimentology 58, 352–375 (2011).

Kabel, K. et al. Impact of climate change on the Baltic Sea ecosystem over the past 1,000 years. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 871–874 (2012).

Papadomanolaki, N. M. et al. Controls on the onset and termination of past hypoxia in the Baltic Sea. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 490, 347–354 (2018).

Virtasalo, J. J. et al. Middle Holocene to present sedimentary environment in the easternmost Gulf of Finland (Baltic Sea) and the birth of the Neva River. Mar. Geol. 350, 84–96 (2014).

Kraemer, D., Tepe, N., Pourret, O. & Bau, M. Negative cerium anomalies in manganese (hydr)oxide precipitates due to cerium oxidation in the presence of dissolved siderophores. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 196, 197–208 (2017).

Fehr, M. A., Andersson, P. S., Hålenius, U., Gustafsson, Ö & Mörth, C.-M. Iron enrichments and Fe isotopic compositions of surface sediments from the Gotland Deep, Baltic Sea. Chem. Geol. 277, 310–322 (2010).

Staubwasser, M., Schoenberg, R., von Blanckenburg, F., Krüger, S. & Pohl, C. Isotope fractionation between dissolved and suspended particulate Fe in the oxic and anoxic water column of the Baltic Sea. Biogeosciences 10, 233–245 (2013).

Conrad, S., Wuttig, K., Jansen, N., Rodushkin, I. & Ingri, J. The stability of Fe-isotope signatures during low salinity mixing in subarctic estuaries. Aquat. Geochem. 25, 195–218 (2019).

Kylander, M. E. et al. Refining the pre-industrial atmospheric Pb isotope evolution curve in Europe using an 8000 year old peat core from NW Spain. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 240, 467–485 (2005).

Silva-Sánchez, N. & Armada, X.-L. Environmental impact of Roman mining and metallurgy and its correlation with the archaeological evidence: A European perspective. Environ. Archaeol. 0, 1–25 (2023).

Bindler, R. et al. Copper-ore mining in Sweden since the pre-Roman Iron Age: Lake-sediment evidence of human activities at the Garpenberg ore field since 375 BCE. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 12, 99–108 (2017).

McConnell, J. R. et al. Pervasive Arctic lead pollution suggests substantial growth in medieval silver production modulated by plague, climate, and conflict. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 14910–14915 (2019).

Ljungqvist, F. C., Seim, A. & Collet, D. Famines in medieval and early modern Europe—Connecting climate and society. WIREs Clim. Change 15, e859 (2024).

Koistinen, T. et al Geological map of the Fennoscandian Shield, Scale 1:2 000 000. Geol. Surv. Finl. Nor. Swed. North-West Dep. Nat. Resour. Russ. (2001).

Stroeven, A. P. et al. Deglaciation of Fennoscandia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 147, 91–121 (2016).

Virtasalo, J. J., Hämäläinen, J. & Kotilainen, A. T. Toward a standard stratigraphical classification practice for the Baltic Sea sediments: the CUAL approach. Boreas 43, 924–938 (2014).

Mäkinen, J. & Saaranen, V. Computation of Land Uplift from the Three Precise Levellings in Finland. (1998).

Leppäranta, M. & Myrberg, K. Physical Oceanography of the Baltic Sea. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-79703-6.

Laine, A. O., Andersin, A.-B., Leiniö, S. & Zuur, A. F. Stratification-induced hypoxia as a structuring factor of macrozoobenthos in the open Gulf of Finland (Baltic Sea). J. Sea Res. 57, 65–77 (2007).

Reed, S. J. B. Electron Microprobe Analysis and Scanning Electron Microscopy in Geology. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511610561.

Pouchou, J.-L. & Pichoir, F. Quantitative analysis of homogeneous or stratified microvolumes applying the model “PAP”. in Electron Probe Quantitation (eds. Heinrich, K. F. J. & Newbury, D. E.) 31–75 (Springer US, Boston, MA, 1991). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2617-3_4.

Jochum, K. P. et al. FeMnOx-1: A new microanalytical reference material for the investigation of Mn–Fe rich geological samples. Chem. Geol. 432, 34–40 (2016).

Jochum, K. P. et al. GeoReM: A new geochemical database for reference materials and isotopic standards. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 29, 333–338 (2005).

Craddock, P. R. & Dauphas, N. Iron isotopic compositions of geological reference materials and chondrites. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 35, 101–123 (2011).

Rodushkin, I. et al. Assessment of the natural variability of B, Cd, Cu, Fe, Pb, Sr, Tl and Zn concentrations and isotopic compositions in leaves, needles and mushrooms using single sample digestion and two-column matrix separation. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 31, 220–233 (2015).

Dauphas, N. & Rouxel, O. Mass spectrometry and natural variations of iron isotopes. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 25, 515–550 (2006).

Rouxel, O. J. & Auro, M. Iron isotope variations in coastal seawater determined by multicollector ICP-MS. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 34, 135–144 (2010).

Baxter, D. C., Rodushkin, I., Engström, E. & Malinovsky, D. Revised exponential model for mass bias correction using an internal standard for isotope abundance ratio measurements by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 21, 427–430 (2006).

Lima, E. A., Weiss, B. P., Baratchart, L., Hardin, D. P. & Saff, E. B. Fast inversion of magnetic field maps of unidirectional planar geological magnetization. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 118, 2723–2752 (2013).

Glenn, D. R. et al. Micrometer-scale magnetic imaging of geological samples using a quantum diamond microscope. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 18, 3254–3267 (2017).

Evans, M. E. & Heller, F. Environmental Magnetism — Principles and Applications of Enviromagnetics. vol. 86 (Academic Press, USA, 2003).

Goslar, T., Czernik, J. & Goslar, E. Low-energy 14C AMS in Poznań Radiocarbon Laboratory. Poland. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 223–224, 5–11 (2004).

Boyle, J., Chiverrell, R. & Schillereff, D. Lacustrine archives of metals from mining and other industrial activities—a geochemical approach. in Environmental Contaminants: Using natural archives to track sources and long-term trends of pollution (eds. Blais, J. M., Rosen, M. R. & Smol, J. P.) 121–159 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9541-8_7.

Toyoda, K., Nakamura, Y. & Masuda, A. Rare earth elements of Pacific pelagic sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 54, 1093–1103 (1990).

Pourmand, A., Dauphas, N. & Ireland, T. J. A novel extraction chromatography and MC-ICP-MS technique for rapid analysis of REE, Sc and Y: Revising CI-chondrite and Post-Archean Australian Shale (PAAS) abundances. Chem. Geol. 291, 38–54 (2012).

Horner, T. J. et al. Persistence of deeply sourced iron in the Pacific Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 1292–1297 (2015).

Marcus, M. A. et al. Iron mineral structure, reactivity, and isotopic composition in a South Pacific Gyre ferromanganese nodule over 4 Ma. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 171, 61–79 (2015).

Jilbert, T. et al. Impacts of flocculation on the distribution and diagenesis of iron in boreal estuarine sediments. Biogeosciences 15, 1243–1271 (2018).

Hirst, C. et al. Iron isotopes reveal the sources of Fe-bearing particles and colloids in the Lena River basin. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 269, 678–692 (2020).

Lotfi-Kalahroodi, E. et al. More than redox, biological organic ligands control iron isotope fractionation in the riparian wetland. Sci. Rep. 11, 1933 (2021).

Fitzsimmons, J. N. & Conway, T. M. Novel insights into marine iron biogeochemistry from iron isotopes. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15, 383–406 (2023).

Wasiljeff, J. et al. Centennial to millennial-scale paleoenvironmental record from a coastal iron-manganese concretion [dataset]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16881134 (2025).

Thierry, S., Dick, S., George, S., Benoit, L. & Cyrille, P. EMODnet Bathymetry a compilation of bathymetric data in the European waters. in OCEANS 2019 - Marseille 1–7 https://doi.org/10.1109/OCEANSE.2019.8867250. (2019).

Seppä, H., Hammarlund, D. & Antonsson, K. Low-frequency and high-frequency changes in temperature and effective humidity during the Holocene in south-central Sweden: implications for atmospheric and oceanic forcings of climate. Clim. Dyn. 25, 285–297 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the constructive comments by Rashida Doctor and two anonymous reviewers that greatly improved our work. We thank the crew of r/v Geomari for sampling assistance, Meiru Zhou for help in sample preparations in the lab, and Ilia Rodushkin for the iron isotope analyses. We also thank Xiaodong Jiang and Xiang Zhao for providing the original age model code and for initial guidance. We further acknowledge Ossi Arasalo for insightful comments and contributions during the development of the age model. We also want to thank Tomasz Goslar for the radiocarbon dating. This work was supported by the Research Council of Finland (Fermaid project, grant 332249). This study has used research facilities provided by the Finnish Marine Research Infrastructure (FINMARI) network. This is HelLabs publication #0028. No permissions were required for sampling.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. and J.V. conceived the original idea and design of the study. A.L. was responsible for the age model development with inputs from J.W. J.W., J.V., Y.L., and A.L. interpreted the data and developed the manuscript. J.W. and J.V. performed field sampling. R.F., J.S., R.M., M.K., and M.M. contributed to laboratory analyses, interpretation, and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Dedication

This paper is dedicated to Yann Lahaye, our co-author and colleague, who passed away in late 2024. Yann was a respected and beloved colleague and instrumental in the development of the Espoo Research Laboratory of the Geological Survey of Finland, especially the ICP-lab. His contributions left a lasting impact, and his absence will be deeply felt by all who knew him.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Claire Nichols and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wasiljeff, J., Lahaye, Y., Lehtonen, A. et al. Centennial to millennial-scale paleoenvironmental record from a coastal iron-manganese concretion. Commun Earth Environ 6, 771 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02741-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02741-z