Abstract

Marine authigenic carbonates are considered a major long-term carbon sink, yet the role of silicate weathering in their formation remains unclear. Here we use lithium isotope compositions of authigenic carbonates from the Gulf of Mexico to trace the coupling between silicate weathering and carbonate authigenesis in marine sediment. In contrast to the positive δ7Licarb values in seep carbonates formed near the seafloor, carbonates originating from organoclastic sulphate reduction in deeper burial settings exhibit negative δ7Licarb values (−6.6‰ to −1.2‰). Calculated δ7Lifluid values (−4‰ to +1.4‰) in pore fluids closely match the δ7Lisilicate values of the silicate component in the rocks, suggesting congruent silicate weathering is approached. A positive correlation between δ7Lifluid and δ13Ccarb values indicates organoclastic sulphate reduction enhances silicate weathering, which together promote carbonate authigenesis in anoxic sediments. Our findings demonstrate that lithium isotopes are a valuable tool for tracing carbon–silicate interactions and reconstructing carbon cycling in anoxic sediments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Authigenic carbonates are carbonate minerals that precipitated in situ from solution, either at the sediment-water interface or within sediment pore water1. These carbonates differ fundamentally from depositional carbonates—which include skeleton and fragments coated allochems—not only in their textural attributes but also in their timing of formation, typically occurring after sediment deposition. Authigenic carbonate formation in marine sediments represents an important long-term sink for carbon, accounting for at least 10% of modern marine carbonate burial and probably a much greater proportion during past intervals of ocean anoxia1,2,3. Understanding the mechanisms that drive carbonate authigenesis is essential for reconstructing Earth’s carbon cycle and its links to global carbon, magnesium and calcium budgets4,5.

In continental margin sediments, authigenic carbonates form above and within the sulphate–methane transition zone (SMTZ), where alkalinity is elevated by the degradation of organic matter through organoclastic sulphate reduction (OSR) or sulphate-driven anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM)6. However, carbonate precipitation is also observed at greater sediment depths, below the SMTZ, where microbial processes such as fermentation and methanogenesis dominate7,8. These processes do not elevate alkalinity but instead generate CO2 and decrease pore water pH, conditions generally considered unfavourable for carbonate precipitation9,10. Nevertheless, pore fluids in deeply buried, methanic sediments commonly exhibit elevated alkalinities, suggesting the presence of an additional, previously underappreciated alkalinity source9.

One possible mechanism is silicate weathering under anoxic conditions, which consumes CO₂ and releases calcium and alkalinity, promoting carbonate formation11,12,13. Recent estimates by Wallmann et al.13 underscore the global significance of this pathway, revealing that anoxic marine sediments sequester ~2.5 trillion mol C yr⁻¹ via authigenic carbonates—with calcium and alkalinity largely sourced from silicate mineral dissolution. Silicate weathering is enhanced by acidic pore fluids that result from organic matter degradation in anoxic sediments9,11,14. However, direct geochemical evidence for silicate weathering in marine sediments is limited, and the relationship between degradation of organic matter and silicate dissolution remains poorly constrained.

Conventional tracers of silicate weathering, such as strontium isotopes (87Sr/86Sr), are commonly confounded by fluid mixing and evaporite dissolution15,16,17,18. This limitation arises because the Sr component in pore fluids is commonly dominated by contributions from ancient deposits or brines15,19,20, while paleo-seawater Sr isotope ratios exhibit wide-ranging temporal variations21. For instance, the 87Sr/86Sr signal from silicate weathering recorded in the Hockley Dome anhydrite (Gulf Coast, U.S.A.) was intensively influenced by mixing with Middle Jurassic seawater, resulting in 87Sr/86Sr ratios ranging from 0.7071 to 0.709215. This case demonstrates that observed isotope variability primarily reflects the proportion of ancient brine-derived Sr rather than the contribution from silicate dissolution during silicate weathering22. In contrast, previous studies have successfully used δ7Li values in pore fluids to reconstruct the degree of silicate weathering congruency in burial sediments23,24,25, making Li isotopes a potential indictor for tracing silicate weathering during authigenic carbonate formation.

Recent studies have shown that authigenic carbonates from the Gulf of Mexico (GoM) formed through OSR at temperatures up to 53 °C, indicating active OSR below the SMTZ26. Considering the widespread occurrence of sulphate replenishment from depth through seawater convection and the dissolution of buried evaporites15,27, OSR-driven carbonate authigenesis possibly represents a carbon sink in deep burial settings of the GoM. However, in contrast to AOM, OSR would lower pH by producing one mole of H+ per mole of sulphur turned over28. Like methanogenesis, OSR itself does not necessarily favour carbonate precipitation since the lower pH can hinder carbonate formation despite the generation of alkalinity28,29. We hypothesize that the coupling of silicate weathering with OSR promotes the formation of authigenic carbonates in the GoM. To explore this connection, we analyse the lithium isotopic composition of carbonates formed in two distinct diagenetic environments: shallow sediments typified by sulphate-driven AOM and deeper sediments dominated by OSR. By comparing δ7Li signatures across these settings, this study provides geochemical evidence for silicate weathering in marine sediments and unravels carbon-silicate interactions during burial diagenesis.

Geological settings and samples

The GoM began forming in the Late Jurassic (~165 Ma) during the breakup of Pangaea. Extension and thinning of the continental crust created restricted marine basins, where evaporation led to the deposition of the Louann Salt. As rifting transitioned to seafloor spreading, opening of a connection to the Atlantic Ocean terminated evaporite deposition, and the basin began receiving vast terrigenous sediment from North America’s rivers30,31. Later, salt deformation in the subsurface led to widespread salt diapirism and fractures, which act as pathways for hydrocarbon and brine migration32,33. The migrating fluids interacted with sediments, affecting pore water chemistry and forming authigenic deposits near the seafloor15,27,32,34. Both, OSR-derived carbonate forming at burial depth and AOM-driven carbonate forming near the seafloor have been reported in the GoM19,20,26,34.

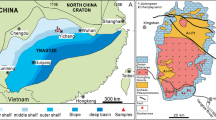

To explore the Li isotope composition of carbonate forming across different diagenetic environments, we analysed 16 carbonate samples from five GoM sites: Ship Shoal 296 (SS296), Green Canyon 53 (GC53), Garden Banks 260 (GB260), Garden Banks 697 (GB697) and Alaminos Canyon 601 (AC601; Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1). These carbonate samples were collected from the seafloor with research submersibles. All study sites were affected by salt diapirism, potentially resulting in material migration and fluid seepage. Three sites with active seepage (GC53, GB697, AC601) are characterized by ongoing fluid expulsion, chemosynthesis-based seep communities and authigenic mineral deposits such as carbonate crusts and barite chimneys34,35,36,37. Sites with carbonate deposits brought up from depth (SS296, GB260) are located within salt-withdrawal basins38,39, typified by horizontally layered salt structures with no evidence of active seepage.

The lithological characteristics of the carbonate rocks analysed herein have been previously described in detail19,20. Microcrystalline, authigenic carbonate minerals are interspersed with silicate detritus in the rock matrix, displaying a texture indicative of carbonate minerals cementing silicate clasts. In this study, mineralogical, elemental and lithium isotope analyses were conducted to characterize the diagenetic signatures of the GoM authigenic carbonates and to trace subsurface processes.

Results and discussion

Authigenic Carbonates Resulting from Sulphate-driven AOM and OSR

The authigenic carbonates resulting from sulphate-driven AOM have been described in detail20. The δ13Ccarb values of these carbonates range widely from −52.2‰ to −0.1‰, with most values lower than −20‰, agreeing with methane and oil as dominant carbon sources cf. ref. 40. The carbonate rocks are dominated by microcrystalline calcium carbonate minerals (calcite and aragonite; Supplementary Table 1), enclosing abundant peloids and skeletal carbonate, and containing pore-filling, marine carbonate cement20. The occurrence of peloids, skeletal carbonate and marine cement is typical of a formation at shallow depth close to the seafloor (Fig. 1) cf. ref. 41.

The authigenic carbonates resulting from OSR have been described in Huang et al.19,26. The presence of framboidal pyrite with relatively low δ34S values (−27.8‰ to 11.5‰) confirms the occurrence of microbial sulphate reduction in the depositional environment where carbonate precipitation took place26. Organic matter enclosed in the carbonates revealed δ13Corg values like the typical sedimentary organic matter in the sediments of the GoM, values higher than those of the organic fractions in seep carbonates42. The δ13Ccarb values range from −16.9‰ to 2.6‰, consistent with carbonate authigenesis influenced by microbial degradation of organic matter mediated by OSR (−20‰ to −1‰)43. Cone-in-cone textures and lower Δ47 values (clumped isotope thermometry) in some of the studied samples (site SS296) indicate higher precipitation temperatures during deep burial26, corresponding with the absence of features typical of a formation in a shallow subseafloor environment such as peloids, skeletal carbonate and marine cement (Fig. 1). The recognition of authigenic carbonates resulting from OSR below the upper SMTZ is surprising and has been linked to the presence of sulphate evaporites and residual marine brines in the subsurface of the GoM19,26.

Lithium isotope fingerprint of silicate weathering

Silicate weathering may play a previously underappreciated role in facilitating carbonate precipitation during OSR in the subsurface of marginal seas, a process that can be traced through the δ7Li signatures preserved in authigenic carbonates. First, the acetic acid-extracted Li from the carbonate phase shows no contamination by detrital silicate as evidenced by the low Ti content (<2.2 μg/g), which is more than two to three orders of magnitude lower than Ti content in the bulk rock (82–1486 μg/g) (Supplementary Table 2). Whereas Li and Ti contents in the bulk rock show a strong correlation, no such relationship exists between the Li and Ti in the carbonate phase determined from the acetic-leaching solutions (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, δ7Licarb values show no corelation with δ7Lisilicate values (Fig. 2B). The δ7Licarb values can therefore primarily be used to reflect the Li isotope composition of the parent fluid. The Δδ7Licarbonate-fluid values during precipitation of aragonite and calcite have been constrained using different solutions44,45,46. Notably, Δδ7Licalcite-fluid values differ between seawater-like solutions (−2.6‰44) and solutions with small ion load (−8.4‰45; −8.5‰46). Day et al.46 ascribed such a difference to the precipitation rate of calcite. Considering that the values derived from seawater-like solution better match marine carbonates, mean fractionation factors of −11.7‰ for aragonite and −2.6‰ for calcite can be adopted to estimate the δ7Li values of the parent fluids44.

A Ti contents versus Li contents in bulk rock and carbonate phase. Ti content shows a positive relationship to Li content in bulk rock. B Plot of δ7Licarb versus δ7Lisilicate values. Error bars for δ7Licarb values represent ±2 SD (standard deviation) of replicates. δ7Lisilicate values are calculated based on Li content and δ7Li value of bulk rocks and carbonate phases. Error bars for δ7Lisilicate values are the uncertainty estimated using the ErrorPropagationTool function in Mathematica (Wolfram Research Inc.). AOM anaerobic oxidation of methane, OSR organoclastic sulphate reduction.

The GoM authigenic carbonates resulting from sulphate-driven AOM exhibit positive δ7Licarb values (3.8‰ to 11.7‰), close to values of seep carbonate from the Black Sea and the Sea of Japan (8.3‰ to 15.6)47. The δ7Lifluid values calculated from the studied GoM seep carbonates, ranging from 9.5‰ to 15.4‰ (Supplementary Table 3), are lower than values of modern seawater (31‰) and brine-seep fluids from Green Canyon 415 of the GoM (44.7‰ to 45.7‰)23. However, the calculated values are within the range of values observed for pore fluids in seep environments (7.5‰ to 32.3‰)23, which reflect a mixture of seawater and seep fluids cf. refs. 23,47. The large variability in δ7Li values of the GoM seep carbonates indicates variable degrees of mixing of seawater and 7Li-depleted seep fluids (Fig. 3).

Box plots show the maximum value, minimum value, median value and interquartile range for the data of authigenic carbonate (carbonate phase; Miyajima et al., 2023), bioclastic carbonate (Rollion-Bard et al., 2009; Misra & Froelich, 2012; Dellinger et al., 2018; Roberts et al., 2018) and platform carbonates (Dellinger et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023). Redrawn from Pogge von Strandmann et al. (2021). Fora.—Foraminifera, carb.—carbonate. Seep carbonate results from sulphate-driven AOM. Estimated lithium isotope compositions of aragonite to calcite represent estimated compositions, reflecting isotopic equilibrium with seawater.

Compared to the GoM seep carbonates, the GoM carbonates resulting from OSR at depth show lower δ7Licarb values (−6.6‰ to −1.2‰). These values are the lowest values reported for carbonate minerals to date (Fig. 3). The calculated δ7Lifluid values of the parent fluids range from −4.0‰ to 1.4‰ (Supplementary Table 3), lower than the values of pore fluids in seep systems near the seafloor47. Low δ7Li values in pore fluids have been attributed to silicate weathering in buried sediments cf. refs. 23,47, since marine clay-rich sediments exhibit low δ7Li values in the range of −1.5‰ to 5‰48. However, the calculated δ7Lifluid values are even lower than the typical δ7Li values of marine clay-rich sediments. During silicate weathering, primary silicate dissolution releases Li of mineral-like δ7Li values into pore fluids while 6Li in pore fluids will be preferentially removed by secondary silicate formation48,49. Consequently, the δ7Li value in solution is controlled by the ratio of primary silicate mineral dissolution to secondary mineral formation (known as “weathering congruency”)22,50. If a rock congruently dissolves without the formation of secondary minerals, the solution will reveal a mineral-like δ7Li value, while incongruent weathering, involving the formation of secondary silicate, leads to higher δ7Li value in solution22,51. Since determining the δ7Li value of ambient sediment during carbonate precipitation is practically impossible, we instead calculated the δ7Lisilicate values of the silicate phase in the authigenic carbonates based on Li content and δ7Li values of bulk rocks and carbonate phases. The calculated δ7Lisilicate values range from −5.1‰ to −1.2‰ (Supplementary Table 3). Such low δ7Lisilicate values reflect the long-term burial history of the silicate component prior to its cementation by authigenic carbonate, agreeing with authigenic carbonate formation at a later burial stage cf. refs. 22,51. The calculated low δ7Lifluid values are close to or slightly higher than the δ7Lisilicate values, reflecting a high ratio of silicate dissolution to formation of secondary silicate minerals, approaching congruent silicate weathering. Since 6Li is preferentially incorporated into carbonate during carbonate authigenesis, the δ7Lifluid values may continuously rise due to carbonate precipitation. Consequently, the primary δ7Lifluid values exclusively influenced by silicate weathering may have even been lower than the calculated values and closer to the δ7Lisilicate values.

When deep pore fluids ascend through marine sediments, light Li isotopes tend to be incorporated into secondary clay minerals during clay mineral authigenesis or be adsorbed on sediment particle surfaces, further increasing δ7Li values of pore fluids23,48,49. Therefore, the calculated low δ7Lifluid values indicate that the pore fluids from which the carbonate minerals precipitated did not migrate over a long distance after silicate weathering took place cf. ref. 23. Our observations therefore suggest that the Li isotopic composition of the OSR-derived authigenic carbonate preserves the signatures of silicate weathering in the parent fluids during carbonate formation at burial depth.

Carbon sequestration through coupled marine silicate weathering and OSR

Negative δ7Licarb values like those documented herein have not been reported to the best of our knowledge, but low δ7Lifluid values similar to those of the parent fluids of OSR-derived carbonates have been encountered in settings influenced by silicate weathering. Low δ7Lifluid values reflect a high ratio of silicate dissolution to formation of secondary silicate minerals23,24,25. The calculated δ7Lifluid values for OSR-derived carbonates resemble the corresponding δ7Lisilicate values, with Δ7Lisilicate-fluid values (δ7Lifluid - δ7Lisilicate) ranging from 0.5‰ to 2.8‰. The Δ7Lisilicate-fluid values are lower than values reported for the Hikurangi subduction zone (~10‰)25, confirming a high ratio of silicate dissolution to formation of secondary silicate mineral during carbonate authigenesis cf. refs. 24,25.

It remains unclear how the scenario of approaching congruent weathering emerges in the system. Similar to methanogenesis, OSR potentially lowers the pH and increases pCO2 of pore fluids, which can impede carbonate precipitation28. Silicate weathering counteracts this effect by neutralizing pH, consuming CO2 and generating HCO3−, thereby promoting carbonate authigenesis in sediments9,12. In cases where OSR proceeds at greater burial depth, favoured by a subsurface source of dissolved sulphate, the production of CO2 is presumably increased, thereby necessitating a higher rate of silicate weathering to enable carbonate precipitation. A weak but consistent positive correlation between δ7Lifluid and δ13Ccarb values is observed among the GoM OSR-derived carbonates (Fig. 4). The low δ13C values in pore fluids are mainly controlled by the OSR contributions43, whereas the low δ7Lifluid values are primarily controlled by silicate dissolution. Since silicate dissolution is promoted under low pH conditions9,11,52, the simultaneous decreases of δ7Lifluid and δ13Ccarb values may reflect enhanced silicate dissolution driven by intensified OSR. Secondary silicate formation may be suppressed during ongoing OSR and carbonate authigenesis. Recently, experiments led to the observation of a amount of secondary silicate mineral formation even in conditions of low pH and constant primary silicate mineral dissolution e.g. refs. 53,54. Thus, OSR may not directly inhibit secondary silicate formation. Instead, the consumption of cations by carbonate authigenesis may limit the development of secondary silicate mineral cf. ref. 10. If this hypothesis is correct, strengthening of silicate dissolution and associated weakening of secondary silicate formation may concur in the complex interactions among organic matter degradation, silicate weathering and carbonate precipitation.

We put forward a conceptual scenario that illustrates the coupled interactions among organic matter degradation, silicate weathering and carbonate precipitation, offering a mechanistic explanation for carbon sequestration in the deep marine sediments of marginal seas (Fig. 5). Microbial degradation of organic matter at depth—fuelled by sulphate from evaporite dissolution—generates acidic conditions that promote silicate weathering. This weathering process favours the conversion of CO2 to HCO3−, enabling carbon to be sequestered in the subsurface despite high CO2 production during organic matter degradation. The existence of such interaction is affirmed by the consistently low δ7Li signatures of the OSR-derived authigenic carbonates and the positive correlation between δ7Lifluid and δ13Ccarb values.

The blue dashed box highlights authigenic carbonate formation near the sulphate–methane transition zone (SMTZ), primarily driven by sulphate-driven anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM). The red dashed box emphasizes authigenic carbonate formation at greater depths, where organoclastic sulphate reduction (OSR) occurs. In this setting, coupled silicate weathering and carbonate precipitation under anoxic, acidic conditions lead to low δ⁷Li values in both pore fluids and carbonate phases. The right panel depicts biogeochemical processes and lithium isotope behaviour during carbonate formation, illustrating how Li isotopes trace the extent of silicate dissolution and the fluid’s residence time. This schematic highlights OSR-derived carbonates as a key element of deep subsurface carbon sequestration.

Evaporites are widely distributed in the sedimentary sequences of marginal seas, with prominent examples including the Gulf of Mexico, the North Sea, the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea55. While our current dataset is admittedly limited to the GoM, the widespread distribution of salt-rich, organic-rich marginal basins implies that OSR-enhanced silicate weathering may represent a previously overlooked pathway of long-term carbon sequestration in anoxic marine sediments. Moreover, due to the similar geochemical effects of methanogenesis and OSR on pore water chemistry, our scenario of a coupling between organic matter degradation, silicate weathering and carbonate precipitation may also apply to sedimentary environments dominated by methanogenesis. Such coupling between methanogenesis and silicate weathering has been put forward as a globally relevant driver of authigenic carbonate formation in marine sediments9,10. Although direct geological evidence remains sparse, consistent geochemical signatures in pore waters and numerical modelling results support its broader significance9,13. The lithium isotope approach used in this study provides a promising tool for identifying and quantifying this silicate–carbon coupling in the sedimentary record. Broader application of this approach may ultimately help refine our understanding of carbon cycling in subsurface marine environments.

Conclusions

Authigenic carbonates from the Gulf of Mexico preserve distinct lithium isotope signatures that reflect their formation environments, ranging from near-surface seepage zones to deeply buried, anoxic sediments. Carbonates formed near or within the sulphate–methane transition zone (SMTZ) close to the seafloor exhibit positive δ7Li values, consistent with precipitation from mixed seawater and seep fluids. In contrast, carbonates formed through organoclastic sulphate reduction (OSR) at burial depths display exceptionally low δ7Li values, corresponding to calculated pore fluid values as low as –4.0‰. These values represent the strongest 6Li enrichment in carbonate minerals reported to date, closely matching the δ7Li values of the accessory silicate minerals enclosed in the authigenic carbonates. Such concordance indicates a high ratio of primary silicate dissolution to secondary clay formation, which was apparently driven by acidity produced during microbial sulphate reduction at burial depth. The alkalinity generated by silicate weathering promoted carbonate authigenesis under otherwise unfavourable acidic conditions, representing a direct link between microbial activity, silicate weathering and carbon mineralization in a marine sedimentary environment. Our findings document a previously unrecognized mechanism of in situ carbon sequestration in anoxic marine sediments, with implications for global carbon cycling and diagenesis. Lithium isotopes thus offer a powerful proxy to trace carbon-silicate interactions in the marine subsurface. Broader application of the lithium isotope approach may help constrain the long-term role of marine silicate weathering in shaping Earth’s climate and geochemical history.

Methods

Mineralogical analyses

Subsamples of the studied rocks were drilled from clean surfaces and crushed to less than 200 mesh using an agate mortar and pestle. Mineralogical analyses were conducted using a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer at the South China Sea Institute of Oceanography, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The X-ray source was generated by a Cu anode operating at 40 kV and 40 mA. The MgCO3 content of calcite was determined based on the 2θ of the 104 peaks in the XRD spectrum56. Following the classification based on calcite stability, low-magnesium calcite contains less than 5 mol% MgCO3, while high-Mg calcite contains more than 5 mol% MgCO357.

Major and trace element analyses

For major and trace element analysis of bulk samples, the powdered samples were digested in Teflon beakers using ultra-cleaned HF/HNO3 (2:1) at 195 °C for 3 days. After evaporation overnight, the residue was dissolved in 15 wt.% HNO3 (5 ml) and heated again at 195 °C overnight. Following a second evaporation, samples were redissolved in 3 wt% HNO3 spiked with an internal rhodium standard. Major elements were analysed with ICP-OES (Agilent 5110) and trace elements with ICP-MS (Agilent 7700x) at Nanjing FocuMS Technology Co. Ltd. Geochemical reference materials of USGS—including basalt (BCR-2, BHVO-2), andesite (AVG-2), rhyolite (RGM-2) and granodiorite (GSP-2)—were used for quality control. Obtained values were cross-checked with certified values from the GeoReM database58. Analytical deviations were less than 5% for MnO; 3% for Na2O, MgO, Al2O3, K2O, CaO and Fe2O3; within 20% for Li content, and better than 5% for Ti content.

Analyses of carbon, oxygen and lithium isotopes

For carbon and oxygen stable isotope analysis, powdered samples were treated with 100% phosphoric acid at 90 °C. The released CO2 was extracted and purified before being introduced into a Delta-V Plus mass spectrometer at the College of Marine Sciences, Shanghai Ocean University. The carbon and oxygen isotope compositions are expressed in delta notation (δ) in per mil relative to the Vienna-Pee Dee Belemnite (V-PDB) standard. Precision was on the order of 0.1‰ for both δ13C and δ18O values.

Individual samples were split into two for repeated measurement of the lithium isotope composition of bulk samples and carbonate phases, respectively. For bulk analysis, about 50 mg samples were treated with HF/HNO3 solution (3:1) in Teflon beakers at 120 °C for two days. After evaporation, samples were redissolved in aqua regia and heated to 120 °C for an additional two days. After mineral digestion, solutions were subsequently dried at 90 °C and redissolved in HCl solution before purification. For carbonate phases, about 50–150 mg samples were dissolved in 5% acetic acid solutions, a method previously validated for accurate carbonate Li isotope measurement59,60. Each sample was vortexed for 10 min, centrifuged at 3000 rps for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected. This procedure was repeated once, followed by two rinses with deionized water using the same vortex-centrifugation process. All collected solutions were dried at 90 °C and redissolved in HCl solution before purification. The solution was also used for Li and Ti content analysis of the carbonate phase using a Thermo iCAP ICP-MS. Lithium separation was achieved using two-step cation exchange chromatography60,61. The obtained purified solutions (~100 ng Li) were analysed for lithium isotope composition using a Thermo Finnigan Neptune MC-ICP-MS. The instrumental mass fractionation generated during determination was corrected by using the following test procedure: Blank 1, Standard (L-SVEC), Blank 2 and Sample. Each sample was analysed four times. The results are expressed in delta notation (δ) in per mil relative to the L-SVEC standard. Standards (IRMM016, RGM-2, AGV-2 and BCR-2) were used to evaluate external accuracy and precision. The δ7Li values of IRMM016, RGM-2, AGV-2 and BCR-2 were 0.23 ± 0.09‰ (2 SD, n = 5), 2.63 ± 0.45‰ (2 SD, n = 12), 6.45 ± 0.40‰ and 2.35 ± 0.15‰, falling within the isotope range reported in previous studies (GeoReM58).

The Li isotope composition of the fluids from which carbonate minerals precipitated (δ7Lifluid values) was calculated using the factors of Li isotope fractionation (i.e., Δδ7Licarbonate-fluid = δ7Licarb − δ7Lifluid) and their mineralogical compositions (δ7Lifluid = δ7Licarb-Δ7Li1*f1-Δ7Li2*f2), following Miyajima et al.47 In the equation, fn represents the proportion of the carbonate mineral N in the carbonate phase. Note that siderite (a calcite group mineral) was treated as calcite for the calculation since the fractionation factor of Li for siderite is unknown to date. The Li isotope composition of the silicate phase (δ7Lisilicate) in the carbonates was calculated using the Li content ([Li]) and the δ7Li values of bulk rock samples and carbonate phase based on the conservation of elements and isotopes in a binary mixing system:

Thus, the δ7Lisilicate value can be calculated

It should be noted that the uncertainty of the calculated δ7Lisilicate values depends heavily on the proportion of carbonate minerals that are qualitatively determined by XRD data, as well as the analysing uncertainties of Li content and the δ7Li values.

Data availability

All data used in the publication, as well as the original data for the Figures, can be found at the following link https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29978509.

References

Schrag, D. P., Higgins, J. A., Macdonald, F. A. & Johnston, D. T. Authigenic carbonate and the history of the global carbon cycle. Science 339, 540–543 (2013).

Sun, X. & Turchyn, A. V. Significant contribution of authigenic carbonate to marine carbon burial. Nat. Geosci. 7, 201–204 (2014).

Akam, S. A., Swanner, E. D., Yao, H., Hong, W.-L. & Peckmann, J. Methane-derived authigenic carbonates – a case for a globally relevant marine carbonate factory. Earth Sci. Rev. 243, 104487 (2023).

Zhao, M.-Y., Zheng, Y.-F. & Zhao, Y.-Y. Seeking a geochemical identifier for authigenic carbonate. Nat. Commun. 7, 10885 (2016).

Loyd, S. J. & Smirnoff, M. N. Progressive formation of authigenic carbonate with depth in siliciclastic marine sediments including substantial formation in sediments experiencing methanogenesis. Chem. Geol. 594, 120775 (2022).

Jørgensen, B. B., Findlay, A. J. & Pellerin, A. The biogeochemical sulfur cycle of marine sediments. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1–27 (2019).

Froelich, P. N. et al. Early oxidation of organic matter in pelagic sediments of the eastern equatorial Atlantic: suboxic diagenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 43, 1075–1090 (1979).

Emerson, S. et al. Early diagenesis in sediments from the eastern equatorial Pacific, I. Pore water nutrient and carbonate results. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 49, 57–80 (1980).

Wallmann, K. et al. Silicate weathering in anoxic marine sediments. Mineral. Mag. 72, 363–366 (2008).

Solomon, E. A., Spivack, A. J., Kastner, M., Torres, M. E. & Robertson, G. Gas hydrate distribution and carbon sequestration through coupled microbial methanogenesis and silicate weathering in the Krishna–Godavari Basin, offshore India. Mar. Pet. Geol. 58, 233–253 (2014).

Aloisi, G., Wallmann, K., Drews, M. & Bohrmann, G. Evidence for the submarine weathering of silicate minerals in Black Sea sediments: Possible implications for the marine Li and B cycles. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst.5, Q04007 (2004).

Torres, M. E. et al. Silicate weathering in anoxic marine sediment as a requirement for authigenic carbonate burial. Earth Sci. Rev. 200, 102960 (2020).

Wallmann, K., Geilert, S. & Scholz, F. Chemical alteration of riverine particles in seawater and marine sediments: effects on seawater composition and atmospheric CO2. Am. J. Sci. 323, 1–39 (2023).

Meister, P. et al. Microbial alkalinity production and silicate alteration in methane charged marine sediments: implications for porewater chemistry and diagenetic carbonate formation. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 756591 (2022).

Posey, H. H., Richard Kyle, J., Jackson, T. J., Hurst, S. D. & Price, P. E. Multiple fluid components of salt diapirs and salt dome cap rocks, Gulf Coast. USA Appl. Geochem. 2, 523–534 (1987).

Blum, J. D. & Erel, Y. A silicate weathering mechanism linking increases in marine 87Sr/86Sr with global glaciation. Nature 373, 415–418 (1995).

Li, Y.-P. & Jiang, S.-Y. Sr isotopic compositions of the interstitial water and carbonate from two basins in the Gulf of Mexico: Implications for fluid flow and origin. Chem. Geol. 439, 43–51 (2016).

Tipper, E. T. et al. Global silicate weathering flux overestimated because of sediment–water cation exchange. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2016430118 (2021).

Huang, H. et al. Formation of authigenic low-magnesium calcite from sites SS296 and GC53 of the Gulf of Mexico. Minerals 9, 251 (2019).

Huang, H. et al. New constraints on the formation of hydrocarbon-derived low magnesium calcite at brine seeps in the Gulf of Mexico. Sediment. Geol. 398, 105572 (2020).

McArthur, J. M., Howarth, R. J. & Bailey, T. R. Strontium isotope stratigraphy: LOWESS version 3: best fit to the marine Sr-isotope curve for 0-509 Ma and accompanying look-up table for deriving numerical age. J. Geol. 109, 155–170 (2001).

Misra, S. & Froelich, P. N. Lithium isotope history of Cenozoic seawater: changes in silicate weathering and reverse weathering. Science 335, 818–823 (2012).

Scholz, F. et al. Lithium isotope geochemistry of marine pore waters – insights from cold seep fluids. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 3459–3475 (2010).

Barnes, J. D. et al. The role of the upper plate in controlling fluid-mobile element (Cl, Li, B) cycling through subduction zones: Hikurangi forearc, New Zealand. Geosphere 15, 642–658 (2019).

Luo, M. et al. Volcanic ash alteration triggers active sedimentary lithium cycling: Insights from lithium isotopic compositions of pore fluids and sediments in the Hikurangi subduction zone. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 642, 118854 (2024).

Huang, H. et al. Organoclastic sulfate reduction in deep-buried sediments: evidence from authigenic carbonates of the Gulf of Mexico. Chem. Geol. 610, 121094 (2022).

Caesar, K. H., Kyle, J. R., Lyons, T. W., Tripati, A. & Loyd, S. J. Carbonate formation in salt dome cap rocks by microbial anaerobic oxidation of methane. Nat. Commun. 10, 808 (2019).

Meister, P. Two opposing effects of sulfate reduction on carbonate precipitation in normal marine, hypersaline, and alkaline environments. Geology 41, 499–502 (2013).

Coleman, M. L. Geochemistry of diagenetic non-silicate minerals: kinetic considerations. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 315, 39–56 (1985).

Ewing, T. E. & Galloway, W. E. Evolution of the northern Gulf of Mexico sedimentary basin. In The Sedimentary Basins of the United States and Canada 627–694 (Elsevier, 2019).

Hudec, M. R., Norton, I. O., Jackson, M. P. A. & Peel, F. J. Jurassic evolution of the Gulf of Mexico salt basin. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 97, 1683–1710 (2013).

Roberts, H. H. & Aharon, P. Hydrocarbon-derived carbonate buildup of the northern Gulf of Mexico continental slope:a review of submersible investigations. Geo Mar. Lett. 14, 135–148 (1994).

Sassen, R. & MacDonald, I. R. Evidence of structure H hydrate, Gulf of Mexico continental slope. Org. Geochem. 22, 1029–1032 (1994).

Feng, D. & Roberts, H. H. Geochemical characteristics of the barite deposits at cold seeps from the northern Gulf of Mexico continental slope. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 309, 89–99 (2011).

Roberts, H. H. Comparison of small salt-cored diapirs (northern Gulf of Mexico slope) with Green Knoll beyond the Sigsbee Escarpment: variability in surface expression and seismic character. In Proceedings of the Annual Offshore Technology Conference 1 537–547 (OTC, 2000).

Sassen, R. et al. Association of oil seeps and chemosynthetic communities with oil discoveries, upper continental slope, Gulf of Mexico. Gulf Coast Assoc. Geol. Soc. Trans. 43, 349–355 (2003).

Roberts, H. H., Feng, D. & Joye, S. B. Cold-seep carbonates of the middle and lower continental slope, northern Gulf of Mexico. Deep. Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 57, 2040–2054 (2010).

Christopher, K. S. & Joel, W. S. Geometry and development of the salt withdrawal basin in Ship Shoal Block 318 and vicinity. Gulf Coast Assoc. Geol. Soc. Trans. 48, 173–180 (1998).

Okuma, A. F., Pressler, R. R., Walker, D. B., Kemp, K. & Boslaugh, B. Baldpate field exploration history, Garden Banks 260, Gulf of Mexico. In GCSSEPM Foundation 20th Annual Research Conference, Deep-Water Reservoirs of the World 739–755 at (GCSSEPM, 2000).

Campbell, K. A., Farmer, J. D. & Des Marais, D. Ancient hydrocarbon seeps from the Mesozoic convergent margin of California.pdf. Geofluids 2, 63–94 (2002).

Feng, D., Roberts, H. H., Joye, S. B. & Heydari, E. Formation of low-magnesium calcite at cold seeps in an aragonite sea. Terra Nova 26, 150–156 (2014).

Feng, D. et al. Contribution of deep-sourced carbon from hydrocarbon seeps to sedimentary organic carbon: evidence from radiocarbon and stable isotope geochemistry. Chem. Geol. 585, 120572 (2021).

Petrash, D. A. et al. Microbially catalyzed dolomite formation: From near-surface to burial. Earth Sci. Rev. 171, 558–582 (2017).

Marriott, C. S., Henderson, G. M., Crompton, R., Staubwasser, M. & Shaw, S. Effect of mineralogy, salinity, and temperature on Li/Ca and Li isotope composition of calcium carbonate. Chem. Geol. 212, 5–15 (2004).

Marriott, C. S., Henderson, G. M., Belshaw, N. S. & Tudhope, A. W. Temperature dependence of δ7Li, δ44Ca and Li/Ca during growth of calcium carbonate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 222, 615–624 (2004).

Day, C. C., Pogge von Strandmann, P. A. E. & Mason, A. J. Lithium isotopes and partition coefficients in inorganic carbonates: Proxy calibration for weathering reconstruction. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 305, 243–262 (2021).

Miyajima, Y. et al. Lithium isotope systematics of methane-seep carbonates as an archive of fluid origins and flow rates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 361, 152–170 (2023).

Chan, L. H., Leeman, W. P. & Plank, T. Lithium isotopic composition of marine sediments. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst.7, Q06005 (2006).

Chan, L., Edmond, J. M. & Thompson, G. A lithium isotope study of hot springs and metabasalts from Mid-Ocean Ridge Hydrothermal Systems. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 98, 9653–9659 (1993).

Wanner, C., Sonnenthal, E. L. & Liu, X. M. Seawater δ7Li: a direct proxy for global CO2 consumption by continental silicate weathering?. Chem. Geol. 381, 154–167 (2014).

Pogge von Strandmann, P. A. E., Dellinger, M. & West, A. J. Lithium Isotopes. vol. 7027 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Penman, D. E., Caves Rugenstein, J. K., Ibarra, D. E. & Winnick, M. J. Silicate weathering as a feedback and forcing in Earth’s climate and carbon cycle. Earth Sci. Rev. 209, 103298 (2020).

Shao, H., Ray, J. R. & Jun, Y.-S. Dissolution and precipitation of clay minerals under geologic CO2 sequestration conditions: CO2 −brine−phlogopite interactions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 5999–6005 (2010).

Kanakiya, S., Adam, L., Esteban, L., Rowe, M. C. & Shane, P. Dissolution and secondary mineral precipitation in basalts due to reactions with carbonic acid. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 122, 4312–4327 (2017).

Milanović, P., Maksimovich, N. & Meshcheriakova, O. Distribution of Evaporite Karst in the World. In Dams and reservoirs in evaporites 1–8 (Springer, 2019).

Goldsmith, J. R., Graf, D. L. & Heard, H. Lattice constants of the calcium-magnesium carbonates. Am. Mineral. 46, 453–457 (1961).

Burton, E. A. & Walter, L. M. The effects of PCO2 and temperature on magnesium incorporation in calcite in seawater and MgCl2-CaCl2 solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 55, 777–785 (1991).

Jochum, K. P. et al. GeoReM: A new geochemical database for reference materials and isotopic standards. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 29, 333–338 (2005).

Lin, J. et al. Accurate measurement of lithium isotopes in eleven carbonate reference materials by MC-ICP-MS with soft extraction mode and 1012 Ω resistor high-gain Faraday amplifiers. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 43, 277–289 (2019).

Li, X., Han, G., Zhang, Q., Qu, R. & Miao, Z. Accurate lithium isotopic analysis of twenty geological reference materials by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Spectrochim. Acta Part B. Spectrosc. 188, 106348 (2022).

Liu, X.-M. & Li, W. Optimization of lithium isotope analysis in geological materials by quadrupole ICP-MS. J. Anal. Spectrom. 34, 1708–1717 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Carbonate samples for this study were collected during projects funded by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and NOAA’s National Undersea Research Program. We dedicate this work to the memory of Dr. Harry H. Roberts (Louisiana State University), whose leadership during the research cruises enabled the collection of these samples. His scientific insight and enduring contributions to marine geology were invaluable, and he is profoundly missed. This study was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42225603, 42406063, 42476069), the Special Fund of South China Sea Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (SCSIO2023QY06) and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2021A1515110323). We are grateful to Editor Feifei Zhang for handling the manuscript. We also extend our sincere thanks to Jack Geary Murphy and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive feedback, which greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H. and D.F. designed the research. D.F., H.H., and W.X. acquired funding, H.H. conducted the experiments. H.H. and S.G. led the data interpretation. H.H., S.G. and D.F., wrote the manuscript. J. P., T. S. W. X., and W. Y. assisted with writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Jack Murphy and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review was single-anonymous OR Peer review was double-anonymous. Primary Handling Editors: Feifei Zhang and Alice Drinkwater. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, H., Gong, S., Peckmann, J. et al. Lithium isotopes trace silicate weathering-driven authigenic carbonate formation in marine sediments. Commun Earth Environ 6, 787 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02756-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02756-6