Abstract

Nitrogen (N) cycling has been reshaped during the Anthropocene epoch, yet the global change pattern of sedimentary N stable isotope (δ15N) remains unclear. Previous research has mainly focused on changes of sedimentary δ15N in remote areas or during the Holocene epoch, yet the differentiation of sedimentary δ15N between remote areas and disturbed regions and the onset of the differentiation time are neglected in the Anthropocene epoch. Here we synthesized published records of well-dated δ15N abundance in sedimentary sequences from 173 sites globally, including natural and disturbed areas, and proposed a conceptual diagram to descript the global change patterns of sedimentary δ15N in past 300 years. Sedimentary δ15N in disturbed sites enriched, with two breakpoints in 1910s and 1950s. The other one, δ15N trend in natural sites mostly depleted, with a breakpoint in 1920s. The timeline aligns with unprecedented anthropic perturbations to the global N cycle, such as the invention and application of the Haber-Bosch process. The divergence of δ15N change pattern between disturbed and natural areas can be attributed to either direct human activities or indirect consequences. Taken together, we propose that the 1910s − 1930s can be considered the precursor of the Anthropocene due to the application of artificial N fixation and its consequent biogeochemical effect. We emphasize that the Haber-Bosch process could be the important event before the impact of human activities on Earth history is reflected in global stratigraphy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the First Industrial Revolution, human-induced changes in the global environment have become significant enough to halt the current Holocene geological epoch and it has been proposed the concept of the Anthropocene1. On March 2024, the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) voted down the proposal to define the Anthropocene as a new geological epoch based on the current geological evidence, however, the concept of the Anthropocene remains controversial, including whether the Earth system has entered the Anthropocene from the Holocene and the onset of the Anthropocene2,3,4. Here, on the one hand, we hypothesize that the Earth system has entered the Anthropocene because human impacts on Earth gradually outweigh natural processes5. For instance, artificial nitrogen (N) fixation by Haber-Bosch reaction accounts for 30% of global N fixation, and atmospheric reactive nitrogen (Nr, primarily as NH3, NO, NO2, or peroxyacetyl nitrates) gradually enriches from this approach6. On the other hand, the proposed potential onsets of the Anthropocene are from 138,000 B.P. to 1950s3,7, indicating large uncertainties. We suggest that the onset of the Anthropocene can be narrowed down to the 1750s–1950s because the industry, population, and productivity in human society have developed rapidly during this period, which may exert global impacts on the Earth system. In particular, the Anthropocene is characterized by the dominance of human activities such as nuclear explosions, land use and land cover change (LUCC), and population growth, compared to other geological epochs3. We assume that the response of remote areas and disturbed regions to global change is equally important during the Anthropocene epoch. Therefore, the scenarios of natural and disturbed should be jointly considered to determine the features of the Anthropocene, especially in N cycle.

In the past century, the application of artificial N fixation (transfer of atmospheric inert N to soil inorganic N pool is approximately 80 × 1012 g/year), the extensive cultivation of leguminous plants (biological N fixation, approximately 40 × 1012 g N/year), and the burning of fossil fuels (emission ~30 × 1012 g Nr/year) have significantly altered the global N biogeochemical cycle, leading to bottom-up changes in the Earth system, especially the biosphere6,8,9. For example, artificial N fixation has exceeded the N fixation capacity of terrestrial organisms worldwide5,10. Meanwhile, the invention of the Haber–Bosch process not only supported exponential human population growth under the use of N fertilizer in agriculture10, but also caused atmospheric Nr deposition via N loss such as volatilization, and runoff globally11, resulting in a series of ecological and environmental problems including eutrophication in aquatic ecosystems12. Aquatic ecosystems are widely distributed on Earth, and their sediments play an important role in recording regional tectonic activity, climate change, and human activities due to their advantages of long-time scales and high resolution. Therefore, sedimentary N (including N concentration and N isotope, δ15N) can reflect changes of global N cycling, especially during the Anthropocene epoch, because of the “Great Acceleration”13.

Previously, research mainly focused on changes in sediment N concentration, such as the enhanced N concentration in remote areas due to the increase in global N deposition14. Yet, the sedimentary N concentration is difficult to reflect changes in N sources. Importantly, stable isotopes could record changes in relationship between biological and environmental conditions, especially for substances that develop in an increasing form, such as sediments15. Combining the information contained in N isotopes (δ15N) and N concentration plays a crucial role in understanding global N cycling changes during the Anthropocene epoch8,16,17. For example, sedimentary δ15N analysis has been applied in remote lacustrine sediments and distinguished differences between the Anthropocene and the Holocene indirectly16,18,19. Simultaneously, it has been reported that human activities such as N fertilizer use, sewage discharge, fossil fuel combustion, and LUCC greatly and directly altered sedimentary δ15N17,20,21. However, the pattern of global change on sedimentary δ15N was still unclear, especially in distinctions between natural and human-influenced ecosystems. Therefore, we hypothesize that the trend of sedimentary δ15N has varied between disturbed and natural areas globally, and that this trend has further expanded during the Anthropocene epoch after the invention of the Haber–Bosch process.

To better verify our hypothesis and understand the temporal patterns of δ15N in sediments, we compiled published records of sedimentary δ15N abundance from 173 sites containing 198 sedimentary sequences globally (although the Northern Hemisphere accounts for 86.4% of the sediments, the trends of sedimentary N changes in the two hemispheres are similar, Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). For this synthesis, sites had to meet specific criteria for sampling density and duration of sedimentary record, including clearly dating up to 300 years and having sufficient data on sedimentary N and δ15N. Ultimately, the global sedimentary δ15N dataset was assembled, including lake, wetland, coastal, reservoir, and ocean ecosystems. According to the description of the original literature (such as, whether sites had agricultural or industrial activities or pollutions discharge into aquatic ecosystem), sites were classed into two types, natural and disturbed, accounting for 87 and 96 sites, respectively (Fig. 1). Subsequently, we used the N deposition flux to semi-quantitatively verify the correctness of the prior classification, resulting in significant differences between natural and disturbed sites from 1860 to 2016 (more detail included in Methods and Supplementary Fig. 2). Overall, sites were distributed broadly over the globe, representing a variety of climates, biomes, and degrees of human impact. Current mean annual precipitation at these sites ranges from 64 to 3100 mm, and mean annual temperature ranges from −16 to 28°C.

Disturbed (black) indicates a sedimentary record that was directly affected by human activities, natural (green) indicates an indirect effect by human activities such as N deposition. For example, at the bottom are photographs of the two types of sample sites: disturbed and natural. Left is Dianchi lake (N 24.84°, E 127.72°), right is Tanggula Glacial Lake (N 32.92°, E 91.97°) (Photo credit: Xin Li), reflecting dramatic differences in landscape.

Results and discussion

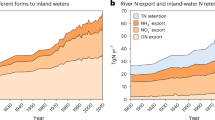

Global patterns of sedimentary δ15N have significantly different trends in the past 300 years (Figure 2a, b), most likely due to the presence or absence of direct human impacts (Supplementary Fig. 3). The trend of sedimentary δ15N is a general increase in disturbed sites (account for 73.0%), whereas the pattern of natural sites showed a decrease (account for 80.5%) (Supplementary Table 1). In natural conditions, atmospheric Nr is transported over long distances and subsequently deposited on terrestrial ecosystems, resulting in increased N loading and aggravated sedimentary N concentration in remote regions (Fig. 2d)16. Meanwhile, the major N sources of natural (or remote) regions come from precipitation with δ15N less <0‰, such as the weighted annual mean δ15N is ≈−3‰ at Pretoria, and similarly in other places22. Finally, the trend of the sedimentary δ15N in remote regions depleted (Fig. 2b), similar to the pattern found in the Greenland ice core16,23. However, the pattern in disturbed sites was opposite to natural sites. The fate of N used in agricultural production varies, with only 17% consumed by humans in crops, dairy, and meat products, while the remainder being lost to the soils, freshwaters, and the atmosphere5,24 resulting in sedimentary N concentration and δ15N increased or enriched (Fig. 2a, c). Additionally, other N sources such as animal feces (δ15N-NO3− ≈ + 7‰ ~ + 20‰)25, sanitary sewage (δ15N-NO3− ≈ + 4‰ ~ + 19‰)26,27 from human activity discharge catchment, leading to sedimentary δ15N enriched as well. Generally, due to factors such as N deposition, agricultural activities, and urban/domestic wastewater discharge, N enters watersheds in inorganic or organic forms14. It is then taken up by phytoplankton and aquatic plants, forming biological N. After plant death, biological N undergoes mineralization, nitrification, and denitrification, resulting in the return of part of the N to the water or atmosphere28. Meanwhile, a portion of organic N binds with planktonic debris and humic substances to form particulate organic nitrogen (PON), which subsequently settles to the bottom through flocculation or hydrodynamic processes29. Once deposited in surface sediments, the decomposition rate of PON decreases under anoxic or reducing conditions. Part of the organic N is mineralized into ammonium via early diagenesis, with some diffusing back into the overlying water, while the remainder becomes rapidly buried and enters long-term storage30. Therefore, the long-term sedimentary δ15N and N concentration records historical nutrient dynamics and signals of anthropogenic activity18,31,32. Overall, an increasing trend in sedimentary N concentration indicates that greater amounts of N have been entering the watershed; meanwhile, the trend of δ15N in sediment reflects in the different sources of ecosystem for natural and disturbed sites over time, mostly caused by human affects during Anthropocene epoch.

a normalized trend of sedimentary δ15N in disturbed sites. b normalized trend of sedimentary δ15N in natural sites. c normalized trend of sedimentary TN in disturbed sites. d normalized trend of sedimentary TN in natural sites. The results of the Davies hypothesis test indicate that (a–d) had least one breakpoint statistically (p < 0.01). Specifically, the red curve represents the non-linear fitting of pyGAM; The blue curve represents the 95% confidence interval for nonparametric fitting; the vertical yellow line indicates the year of the breakpoint; and the vertical green lines demonstrated the ± 1 standard deviation for the breakpoint.

More importantly, there are two differences in the distribution patterns of sedimentary δ15N between natural and disturbed sites. First, disturbed sites show two transition points, in 1908 ± 3 years (±1 standard deviation) and 1965 ± 3 years (±1 standard deviation), respectively (Fig. 2a). Natural sites only exhibit a transition point in 1917 ± 10 years (±1 standard deviation), later than the first breakpoint (1908) in disturbed sites with time-lag of ~10 years. This is likely due to the fact that disturbed N flows directly into the watershed, causing rapid sedimentary δ15N changes. However, atmospheric Nr is transported to remote areas by atmospheric circulation. Second, the sedimentary δ15N change rate after the first transition points is different; the rate of anthropogenic (0.0101 (R2 = 0.90)) is higher than natural (0.0068 (R2 = 0.87)) of Normalized δ15N year-1, possibly related to the distinctions of N source-δ15N and the intensity of human effect. For example, the δ15N of disturbed sites tends to be higher or more positive than natural sites. Conclusively, sedimentary δ15N exhibits significantly different patterns of change in natural and disturbed catchments.

Remarkably, the trend of δ15N changes in regional sediments contradicts the global model (Supplementary Table 1). For instance, the changing pattern of sedimentary δ15N in natural sites is enriched, and in disturbed sites is depleted, indicating these divergent trends are likely relative to local catchment features or other factors (named “local factors”). The Hornsund fjord (77°N, 15–16°30′E), the Atlantic Arctic region without human impacts, contains bird colonies of the Alle alle species. These sedimentary δ15N (Hor 7) were significantly enriched in 1920 (δ15N change over 12‰), clearly demonstrating the beginning of bird impact on this site33. And, the Gulf of Palermo in the central Mediterranean is affected by urban and industrial pollution. Yet the sedimentary δ15N depleted with years, which may be controlled by phytoplankton N uptake during growth34. Meanwhile, minor changes should not be ignored during the individual sedimentary δ15N trend that likely indicates local progress. For example, in Tanggula Glacial Lake on Tibetan Plateau (N 32.92°, E 91.97°) with less human activities, the sedimentary δ15N enriched at the beginning (Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting the increase in atmospheric Nr deposition led to algal or phytoplankton (δ15N ≈ +3.9‰ ~ + 5.0‰ in Gaigong Cuona lake) blooms and then influenced sedimentation35,36. Moreover, warming can significantly influence post-depositional processes such as denitrification, thereby altering the change trend of sedimentary δ15N. For example, warming mostly enhanced nitrous oxide emissions within the watershed in tundra regions, resulting in more positive sedimentary δ15N37. Overall, the pattern of sedimentary δ15N was not only controlled by N sources, but was also affected by local catchment features or other factors (such as warming, animal settlement, algal bloom, etc.).

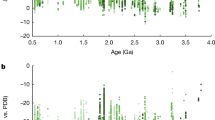

To accurately determine the starting point of δ15N changes in sediment sequences, we relied on the sedimentary δ15N database in this analysis and selected sediments that were primarily affected by global nitrogenous changes or human activities (excluding local progress or other factors mostly) to infer the breakpoints during the Anthropocene. As shown in Fig. 3a, the most significant breakpoint in disturbed sites when sedimentary δ15N enriched trend emerged was in 1955 ± 16 year (±1 standard deviation), which contradicts the time of the first transition point in Fig. 2a. We speculate that this could possibly be related to algorithm preferences. There are two transition points of sedimentary δ15N for disturbed sites in Fig. 2a (sedimentary TN also shows similar pattern, Fig. 2c), and the change rate of the second transition point (1965 year) is greater than the first one. For such reason, the algorithm selects the most significant trend of changes or integrated two breakpoints comprehensively. Interestingly, the most significant breakpoint is in 1923 ± 17 years (±1 standard deviation) in natural sites (Fig. 3b), similar to Fig. 2b (1917 ± 10 years), reflecting the consistency of the two algorithms. Besides, compared to Fig. 2, Fig. 3 uses a “purer-dataset”, and its results more accurately represent the timing at which changes in the global N cycle became recorded in the sedimentary archive. Additionally, previous studies suggested that the 1950s (human activities and global environmental changes with “the Great Acceleration”) and 1945 or 1964 (nuclear explosion) could be regarded as the onset of the Anthropocene3,7, which was close to the break point in 1961 at disturbed sites in this study, that likely overlook the preceding change. In summary, integrating the results from the two approaches and considering the strong influence of synthetic N fixation, the Great Acceleration on disturbed sites, and the relatively limited impact of atmospheric N deposition on natural sites after the 1950s (Supplementary Fig. 2), we suggest that two breakpoints are present in disturbed sites, while only one breakpoint in natural regions globally.

Grey curve indicates the distribution of Y0 in individual sediment, red curve indicates the distribution of global Y0. Y0 indicates a critical time threshold when the effects of human contributions to N deposition (expressed in years before 2010). a Global Y0 hyper-parameter distribution for disturbed sites. b Global Y0 hyper-parameter distribution for natural sites. More details are described in “Methods”.

Furthermore, based on the global change pattern of sedimentary δ15N in the past 300 years (Fig. 2, and Fig. 3), we propose a conceptual diagram of the temporal trends of sedimentary δ15N abundance in the Anthropocene epoch (Fig. 4). Sedimentary δ15N abundance tends to be enriched at disturbed sites because of the direct emissions of disturbed N scours, meanwhile, the trend of sedimentary δ15N likely experienced two breakpoints, 1910s and 1950s, respectively (Fig. 4b, indicated by red dots). At natural sites, sedimentary δ15N mostly depleted (1920s) over time in the past 300 years because the precipitation with δ15N < 0‰ was the main N sources for field catchment (Fig. 4d, represented at red dot). Simultaneously, the deflection of sedimentary δ15N at disturbed sites is greater than natural sites due to disturbed δ15N (δ15N ≈ + 4 ~ + 20‰) is higher than precipitation (δ15N < 0‰) (Fig. 4). However, owing to local or other factors, sedimentary δ15N deviation may differ from the main global patterns (Fig. 4, indicated by dashed lines). More importantly, global N biogeochemical cycle has undergone significant changes due to the invention of the Haber-Bosch process, resulting in the sedimentary δ15N diverge during the 1910s–1930s (Fig. 4).

a indicates the trend of N concentration in disturbed sites. b indicates the trend of δ15N in disturbed sites. c indicates the trend of N concentration in natural sites. d indicates the trend of δ15N in natural sites. Red dots mark potential breakpoint points in sedimentary records (a–d). Solid and dashed lines denote global versus local trends in TN and δ15N. The left part contrasts N sources in disturbed (agriculture, wastewater, aquaculture, etc.) and natural catchments (atmospheric N deposition, watershed input, etc.). Specifically, human activities such as sewage discharge, agricultural fertilization, and fisheries significantly influence sediment N accumulation through direct emissions or short-distance dry/wet deposition. Conversely, sediment N dynamics in natural areas are primarily governed by long-distance N transport processes. However, sedimentary N concentrations are not solely determined by N deposition intensity, but are also modulated by global hydrological cycling processes, such as damming, glacial melting, and LUCC54,55,56. Consequently, the trend patterns of sediment δ15N likely serve as more robust indicators for delineating human-driven modifications to the global N cycle during the Anthropocene. The diagram adapted from Ariane Arias-Ortiz57.

The Anthropocene working group (AWG) proposed that the mid-twentieth-century is onset of Anthropocene (a spike in atmospheric plutonium concentrations caused by the first hydrogen-bomb tests is seen consistently in sediments worldwide), but this was rejecting by ICS2. However, the proposal remains generally accepted because of its fit with many socio-economic drivers and Earth-system responses after the Second World War, which was named the “Great Acceleration”2,38. Yet, modifications of the Earth’s environment by human activity events (e.g. early agriculture development39,40, Columbian Exchange41, Industrial Revolution42) still cannot be ignored before the “Great Acceleration”. For this reason, the concept of “The Anthropocene Is More Than a Time Interval” was proposed, and emphasized the cumulative/continuing impact of disturbed events on Earth’s history43,44. The anthropic synthesis of ammonia represents a further increase in the productivity of human society10. Therefore, we suggest that the Haber-Bosch process is the precursor for the Earth’s Anthropocene evidenced from sedimentary δ15N globally (Figs. 2, 3). Firstly, prior to the invention of the Haber-Bosch process, the main source of fertilizers relied on the mining of mineral deposits such as the phosphate layer on Jawa island. Therefore, the impact of human activities on the Earth’s N cycle was limited. However, due to the exponential increase in N fertilizer production as a result of the invention of the Haber-Bosch process in 1908 (Supplementary Fig. 5), disturbed impacts on N cycling began to emerge. Even more, the fixation of N through Haber-Bosch process (120 Tg N yr−1) in 2010 was double the natural terrestrial sources of Nr (63 Tg N yr-1)5. Secondly, artificial N fixation has greatly contributed to the world’s population growth (8 billion in 2022, approximately 3 times compared to mid-twentieth-century), resulting in the ability of humans to modify the Earth being strengthened (the expansion of cities, the exploitation of mineral resources, deforestation, etc.)7, which has accelerated the arrival of the Anthropocene40. In other words, the “Great Acceleration” could be delayed by decades or centuries without artificial N fixation. Thirdly, N as one of the key life elements involved in biological activity, meanwhile the N-limited is widespread on Earth45,46. Hence, the leakage of N fertilizers is clearly causing global biodiversity changes, ultimately altering the Earth’s environment from the bottom up9. To our knowledge, the invention of the Haber-Bosch process (humans converted ammonia from the atmosphere) may be similar to the Great Oxidation Event (cyanobacteria excrete oxygen about 2.7 billion to 2.2 billion years ago, leading to the first mass extinction of organisms) and other geological events of significant importance to Earth’s history.

In summary, sedimentary δ15N exhibits great performance in tracing N cycling or sources changes. We proposed a conceptual model for the temporal pattern of sedimentary δ15N abundance based on the global sedimentary δ15N database from 86 publications (Supplementary Data). Meanwhile, we emphasize that the invention of the Haber-Bosch process had led to significant changes in sedimentary δ15N globally, potentially reflecting the Earth entering the Anthropocene. However, determining a new geological epoch for the Earth system is an extremely complex systematic process that requires the consideration of a series of biogeochemical processes, such as the element cycles across the biosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, cryosphere, and lithosphere19. This study only stands from the perspective of N cycling and relies on temporal trends of sedimentary δ15N abundance and N concentration to emphasize that the Haber-Bosch process is mostly event as precursor of the Anthropocene, which may have limitations. Therefore, future research on the Anthropocene requires the integration of multiple factors and processes, such as combining sediment multi-agent indicators (e.g. diatoms, carbon isotopes, carbon-nitrogen ratios, pollen, etc.) and recording materials (e.g. tree rings, ice cores, etc.), and incorporating global changes such as increasing greenhouse gas concentrations and changes in temperature on global biogeochemical cycles.

Methods

Literature search and data pre-processing

Literature search was conducted using Web of Science database and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) with keywords “nitrogen isotopes”, “nitrogen”, “sediment”, “wetland”, “lake”, “delta (15)N”, “δ15N” and “aquatic ecosystems” in April 2024. A total of 86 publications that met the criteria of providing well-dated N stable isotopes and N concentration in aquatic ecosystems were selected. All studies reported bulk sedimentary δ15N data expressed in standard delta notation relative to the isotopic composition of air. Data used for the analysis (sedimentary δ15N, chronology, and N concentration) were obtained from the publications by GetData Graph Digitizer (version 2.22). In the case of duplicate cores from the same study site, all cores were chosen because of the heterogeneity of sediments. Meanwhile, base information of sample sites, such as longitude, latitude, sampling water table, Human Footprint47, the aridity index48, annual precipitation, temperature, and altitude (http://worldclim.org) were also collected. More importantly, according to the trend of original δ15N abundance over time, the trend was categorized into enriched and depleted, and the study sites were classed into two types, natural and disturbed sites, based on the description of literature (i.e., presence of agricultural or industrial activities), respectively. Finally, considering the heterogeneity of sedimentary sequences, the Z-score standardized method was applied in this synthesis.

Noticeably, the majority of sampling sites in this study are located in the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 1), which may introduce bias in the global assessment of sedimentary N concentration and δ15N. To evaluate whether temporal trends are consistent across hemispheres, we categorized the dataset into Northern and Southern Hemisphere groups based on site latitude. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, although the Southern Hemisphere is underrepresented, the overall trends in sedimentary N concentration and δ15N are broadly consistent with those observed in the Northern Hemisphere. Therefore, we consider the pooling of all sites for global-scale analysis. In addition, the classification of “natural” and “disturbed” based on descriptions from the original literature may introduce subjectivity. To address this, we conducted a posterior validation using gridded N deposition data (combined nitrate and ammonium deposition) from 1860 to 201649. Specifically, we averaged monthly N deposition data to obtain annual values, and then divided the full record into four time periods: 1860–1900 (representing natural background conditions), 1901–1950 (the starting period of N deposition increase), 1951–2016 (the “Great Acceleration” period), and 1860–2016 (long-term average). Subsequently, we applied Kruskal-Wallis tests (two-side) to evaluate differences in N deposition. The results show that disturbed sites experienced significantly higher N deposition than natural sites across all periods (p < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 2). Interestingly, disturbed sites of N deposition during 1860–1900 and 1901–1950 had significant differences (p < 0.01), not yet in natural sites, consistent with the observation that disturbed sites exhibit two breakpoints in sedimentary N, while natural sites show only one (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 2). Remarkably, anthropic N sources include not only atmospheric deposition but also direct human emissions (e.g., domestic wastewater, fertilizer leakage). In summary, although limitations exist, the spatial dataset is sufficiently representative for global analysis, and the qualitative classification of sites into natural and disturbed sites is supported. Therefore, we conducted the following statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses

To determine the pattern of sedimentary δ15N abundance over time at disturbed and natural sites, firstly, frequency statistics were performed in Excel (Supplementary Table 1). Subsequently, the BorutaShap algorithm was applied to feature selection (or relative importance) using the “BorutaShap” package in Python; the δ15N trend was dependent variable, and other factors were independent variables (Supplementary Fig. 3). Briefly, BorutaShap is a feature selection algorithm based on the combination of Boruta and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP). It not only evaluates the importance of features by using SHAP values, but also accurately preserves features that contribute to the target, thereby improving the interpretability and predictive ability of the model (https://pypi.org/project/BorutaShap).

To obtain the global change trend of sedimentary δ15N abundance and N concentration after standardization, smooth semi-parametric regression model was conducted using the “pyGAM” package to fit a regression curve of all points in Python50. In this study, actually, the independent variable is dating year, and the dependent variable is the standardized sedimentary N concentration or δ15N. We choose LinearGAM with a normal error distribution and an identity link to fit regression curve. Specifically, we set the parameter (“n_splines”) to 15 to make the regression curve smoother.

Subsequently, we referred to Muggeo’s method to estimate regression breakpoints using the “piecewise_regression” package in Python (Fig. 2)51,52. The Muggeo’s method derived an alternative method whereby the breakpoint positions and the line segment models are fitted simultaneously using an iterative method, which is computationally efficient and allows for robust statistical analysis52. Meanwhile, a Davies hypothesis test for the existence of at least 1 breakpoint53. Besides, Muggeo’s method can fit by more than one breakpoint or might not know how many breakpoints to expect in the data. In this study, therefore, this method was used to evaluate the breakpoints in the fitted curve. However, global sedimentary δ15N data included “local effects”, and the choice of parameters (“n_breakpoints = ”) is subjective in the “piecewise_regression” package. For these reasons, we further performed a hierarchical Bayesian modeling framework in R16.

Importantly, we excluded sedimentary δ15N data that might be affected by the “local affects”, and then bring the pure sedimentary δ15N data into the hierarchical Bayesian model. Notably, the hierarchical Bayesian model does not require standardization. Firstly, the power function model was constructed, the form is:

where C0 is the average preindustrial δ15N and k is the rate constant describing annual change over time. Time (Ti) is the difference between a given year in the historical record (Yi; expressed in years before 2010) and a critical time threshold when the effects of human contributions to N deposition are estimated to have begun (Y0)16. Then, specify the prior distribution of the model parameters, such as C0 is consistent with the uniform distribution. Finally, use the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method to estimate the posterior distribution of the parameters, more details refer to Holtgrieve GW, et al.16. For the global hyperparameters, it is obtained by mean the parameters of each sediments (including Y0, k, or both Y0 and k)16. In this study, we incorporated the sedimentary δ15N data into the model to obtain the global estimate of Y0 for natural sites (Fig. 3b). Specifically, the original power function model was adapted only to natural sites (or depleted trend). Therefore, we added negative signs to the front of exponential part (\({+C}_{0}^{k{T}_{i}}\)) of this power function model without changing other parameters (in other words, the exponential model only changes the direction), resulting in it being applicable to disturbed sites (or enriched trend, Fig. 3a).

Data availability

All raw data used from the global synthetic analysis are provided in the Supplementary Data. Human Footprint data could be found at [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-022-01284-8]. The aridity index data could be found at [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-022-01493-1]. Annual precipitation, temperature, and altitude could be found at [http://worldclim.org], and the gridded N deposition data could be found at [https://data.isimip.org/search/tree/ISIMIP2a/query/ndep/]. The data for all figures presented in this article are available at [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30048526.v1].

Code availability

The “BorutaShap” package could be found at [https://pypi.org/project/BorutaShap]. The “pyGAM” package could be found at [https://pypi.org/project/pygam/]. The “piecewise_regression” package could be found at [https://github.com/chasmani/piecewise-regression], and the “hierarchical Bayesian modeling” could be found at [https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1212267]. All plotting codes and associated files are accessible at [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30048526.v1].

References

Crutzen, P. J. Geology of mankind. Nature 415, 23 (2002).

Zalasiewicz, J. et al. What should the Anthropocene mean: Why it matters even without a formal geological definition. Nature 632, 980–984 (2024).

Smith, B. D. & Zeder, M. A. The onset of the Anthropocene. Anthropocene 4, 8–13 (2013).

Prillaman, M. Are we in the Anthropocene? Geologists could define new epoch for Earth. Nature 613, 14–15 (2023).

Fowler, D. et al. The global nitrogen cycle in the twenty-first century. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 368, 20130164 (2013).

Li, C. BIOGEOCHEMISTRY Scientific Fundamentals and Modeling Approach (eds P. Liu & C. Zhao) 189-189 (Tsinghua University Press, 2016).

Yin, Z. Y. & Liu, X. “The Anthropocene”—its proposition and controversies. Quat. Sci. 43, 1146–1156 (2023).

Wolfe, A. P. et al. Stratigraphic expressions of the Holocene–Anthropocene transition revealed in sediments from remote lakes. Earth Sci. Rev. 116, 17–34 (2013).

Elser, J. J. et al. Shifts in Lake N:P stoichiometry and nutrient limitation driven by atmospheric nitrogen deposition. Science 326, 835–837 (2009).

Erisman, J. W., Sutton, M. A., Galloway, J., Klimont, Z. & Winiwarter, W. How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world. Nat. Geosci. 1, 636–639 (2008).

Galloway, J. N. et al. Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science 320, 889–892 (2008).

Carpenter, S. R. Eutrophication of aquatic ecosystems: bistability and soil phosphorus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 102, 10002–10005 (2005).

Zalasiewicz, J. et al. The Anthropocene: Comparing Its Meaning in Geology (Chronostratigraphy) with Conceptual Approaches Arising in Other Disciplines. Earth’s. Future 9, e2020EF001896 (2021).

Galloway, J. N. et al. Nitrogen Cycles: Past, Present, and Future. Biogeochemistry 70, 153–226 (2004).

Lin, G. Stable Isotope Ecology (eds L. Liu & Y. Guan) 365 (Higher Education Press 2013).

Holtgrieve, G. W. et al. A Coherent Signature of Anthropogenic Nitrogen Deposition to Remote Watersheds of the Northern Hemisphere. Science 334, 1545–1548 (2011).

Dutton, C. L. et al. A 2000-year sediment record reveals rapidly changing sedimentation and land use since the 1960s in the Upper Mara-Serengeti Ecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 664, 148–160 (2019).

McLauchlan, K. K., Williams, J. J., Craine, J. M. & Jeffers, E. S. Changes in global nitrogen cycling during the Holocene epoch. Nature 495, 352–355 (2013).

Waters, C. N. et al. The Anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene. Science 351, aad2622 (2016).

Zan, F. et al. A 100-year sedimentary record of natural and anthropogenic impacts on a shallow eutrophic lake, Lake Chaohu, China. J. Environ. Monit. 14, 804–816 (2012).

Struck, U., Emeis, K. C., Voss, M., Christiansen, C. & Kunzendorf, H. Records of southern and central Baltic Sea eutrophication in δ13C and δ15N of sedimentary organic matter. Mar. Geol. 164, 157–171 (2000).

Heaton, T. H. E. Isotopic studies of nitrogen pollution in the hydrosphere and atmosphere: A review. Chem. Geol. Isot. Geosci. Sect. 59, 87–102 (1986).

Hastings, M. G., Jarvis, J. C. & Steig, E. J. Anthropogenic impacts on nitrogen isotopes of ice-core nitrate. Science 324, 1288–1288 (2009).

Leach, A. M. et al. A nitrogen footprint model to help consumers understand their role in nitrogen losses to the environment. Environ. Dev. 1, 40–66 (2012).

Aravena, R. & Robertson, W. D. Use of multiple isotope tracers to evaluate denitrification in ground water: study of nitrate from a large-flux septic system plume. Groundwater 36, 975–982 (1998).

Li, X., Masuda, H., Koba, K. & Zeng, H. Nitrogen Isotope Study on Nitrate-Contaminated Groundwater in the Sichuan Basin, China. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 178, 145–156 (2007).

Koh, D.-C., Kim, E.-Y., Ryu, J.-S. & Ko, K.-S. Factors controlling groundwater chemistry in an agricultural area with complex topographic and land use patterns in mid-western South Korea. Hydrol. Process. 23, 2915–2928 (2009).

Seitzinger, S. P. Denitrification in freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems: Ecological and geochemical significance. Limnol. Oceanogr. 33, 702–724 (1988).

Huynh, T. T. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of suspended particulate matter in water environments: a review. Water 16, 3613 (2024).

Lehmann, M. F. et al. Seasonal variation of the δC and δN of particulate and dissolved carbon and nitrogen in Lake Lugano: Constraints on biogeochemical cycling in a eutrophic lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49, 415–429 (2004).

Wang, X. T. et al. Natural forcing of the North Atlantic nitrogen cycle in the Anthropocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 115, 10606–10611 (2018).

Castro, P., Valiela, I. & Freitas, H. The use of sedimentary %C, %N, delta(15)N, and Pb concentrations to assess historical changes in anthropogenic influence on Portuguese estuaries. Environ. Pollut. 147, 706–712 (2007).

Gąsiorowski, M. & Sienkiewicz, E. Bird population changes reconstructed from isotopic signals of peat developed in a nutrient enriched tundra. Sci. Total Environ. 646, 1359–1366 (2019).

Di Leonardo, R., Cundy, A. B., Bellanca, A., Mazzola, A. & Vizzini, S. Biogeochemical evaluation of historical sediment contamination in the Gulf of Palermo (NW Sicily): Analysis of pseudo-trace elements and stable isotope signals. J. Mar. Syst. 94, 185–196 (2012).

Zhu, Y. Long-term characteristics and patterns of algal responses to regional warming and atmospheric deposition in alpine lakes on the southeastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau. (2023).

Hu, Z., Yang, X., Anderson, N. J. & Li, Y. The Landscape–Atmosphere Continuum Determines Ecological Change in Alpine Lakes of SE Tibet. Ecosystems 21, 839–851 (2018).

Anderson, N. J., Engstrom, D. R., Leavitt, P. R., Flood, S. M. & Heathcote, A. J. Changes in coupled carbon‒nitrogen dynamics in a tundra ecosystem predate post-1950 regional warming. Commun. Earth Environ. 1, 38 (2020).

Steffen, W., Broadgate, W., Deutsch, L., Gaffney, O. & Ludwig, C. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. Anthropocene Rev. 2, 81-–898 (2015).

Ruddiman, W. F. The Anthropogenic Greenhouse Era Began Thousands of Years Ago. Climatic Change 61, 261–293 (2003).

Ruddiman, W. F. The Anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 41, 45–68 (2013).

Lewis, S. L. & Maslin, M. A. Defining the Anthropocene. Nature 519, 171–180 (2015).

Crutzen, P. J. Earth System Science in the Anthropocene (eds E. Ehlers & T. Krafft) 13-18 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2006).

Edgeworth, M. et al. The Anthropocene is more than a time interval. Earth’s. Future 12, e2024EF004831 (2024).

Steffen, W. et al. Stratigraphic and Earth System approaches to defining the Anthropocene. Earth’s. Future 4, 324–345 (2016).

Paerl, H. W. Why does N-limitation persist in the world’s marine waters?. Mar. Chem. 206, 1–6 (2018).

Vitousek, P. & Field, C. B. Global Biogeochemical Cycles in the Climate System (eds E-Detlef S. et al.) 217-225 (Academic Press, 2001).

Mu, H. et al. A global record of annual terrestrial Human Footprint dataset from 2000 to 2018. Sci. Data 9, 176 (2022).

Zomer, R. J., Xu, J. & Trabucco, A. Version 3 of the Global Aridity Index and Potential Evapotranspiration Database. Sci. Data 9, 409 (2022).

Tian, H. et al. The global N2O Model Intercomparison Project (NMIP): Objectives, Simulation Protocol and Expected Products. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, 1–51 (2018).

Daniel Servén, & Charlie Brummitt. pyGAM: Generalized Additive Models in Python. Zenodo, (2018).

Muggeo, V. M. R. Estimating regression models with unknown break-points. Stat. Med. 22, 3055–3071 (2003).

Pilgrim, C. piecewise-regression (aka segmented regression) in Python. J. Open Source Softw. 6, 3859 (2021).

Davies, R. B. Hypothesis testing when a nuisance parameter is present only under the alternatives. Biometrika 74, 33–43 (1987).

Owens, P. N. Soil erosion and sediment dynamics in the Anthropocene: a review of human impacts during a period of rapid global environmental change. J. Soils Sediment. 20, 4115–4143 (2020).

Fluet-Chouinard, E. et al. Extensive global wetland loss over the past three centuries. Nature 614, 281–286 (2023).

Shugar, D. H. et al. Rapid worldwide growth of glacial lakes since 1990. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 939–945 (2020).

Arias-Ortiz, A. et al. Reviews and syntheses: 210Pb-derived sediment and carbon accumulation rates in vegetated coastal ecosystems—setting the record straight. Biogeosciences 15, 6791–6818 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the associate editor and the reviewers for their useful comments that improved this paper. We also appreciate Dr. Grace Cott from the University College Dublin, Ireland for improving the English language used in the manuscript. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 32160288, 32272818, 32471561, 32472837), the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) program (grant number: 2019QZKK0308), the Key Project of Yunnan Provincial Basic Research Program (grant number: 202301AS070024), the Thousand Young Talents Program of Yunnan Province, Double Top University Plan Fund of Yunnan University (grant number: C176220100044), and Scientific Research and Innovation Project of Postgraduate Students in the Academic Degree of Yunnan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L., X.L., and X.D. conceived the research and designed the study. M.L., Z.Z., X.L., and X.D. obtained funding. X.L. and J.W. synthesized published data for the analyses and performed the lab analyses. X.L., J.Z., M.L., and X.D. analyzed data and wrote the draft of the manuscript, and all authors (X.L., M.L., J.W., L.C., Z.Z., X.W., J.Z., K.J., X.Z., and X.D.) contributed to the final version of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Alberto Araneda and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review was single-anonymous OR Peer review was double-anonymous. Primary Handling Editors: Somaparna Ghosh [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Lu, M., Wu, J. et al. Global change pattern of sedimentary nitrogen isotope during the Anthropocene epoch. Commun Earth Environ 6, 809 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02773-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02773-5