Abstract

Hydrothermal fluid migration and supercritical phase transitions around the brittle–ductile transition are key to understanding volcanic activity and geothermal energy, but it remains challenging due to limited subsurface imaging. Here we conducted active-source seismic surveys at Kuju volcano, Japan, applying extended common-reflection-surface analysis to image magma-related and hydrothermal structures. We further estimated earthquake hypocenters, focal mechanisms, and seismic velocity. A continuous horizontal reflector could indicate a low-permeability seal confining supercritical fluids, while a low-amplitude reflection zone reveals fractures disrupting the seal. This permeable window, located at the magma margin, coincides with earthquake clusters of various focal mechanisms, suggesting upward fluid migration. A plume-shaped zone with low P-wave and S-wave velocity ratio (Vp/Vs) above the permeable window indicates thermally-altered formations and gas release from phase transitions. These results provide 3D visualization of the interplay among trapped supercritical fluid, its migration through permeable window, and related seismicity near the brittle-ductile transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pathways and the phase transitions of supercritical fluids around the volcanic brittle–ductile transition (BDT) critically influence the dynamics of magmatic-hydrothermal systems by regulating fluid migration, pressure redistribution, and associated seismic and volcanic activity. However, these deep and complex structures remain poorly imaged due to the lack of effective geophysical methods1,2,3. This challenge is especially pronounced in onshore mountainous volcanic regions, where seismic exploration is inherently difficult. From an energy engineering perspective, visualizing structures around the BDT in mountainous area is fundamental to the assessment of supercritical geothermal power potential4. The supercritical fluids are believed to have the potential to generate higher energy outputs compared to conventional geothermal systems5,6. The supercritical fluids are expected at depths near the BDT, where an impermeable sealing horizon allows pressures to exceed hydrostatic levels7. Because rocks are likely to behave ductilely in such high-pressure and high-temperature environments, it has been proposed that supercritical fluids are associated with a low risk of brittle failures, such as earthquakes8. Therefore, understanding the location of BDT is crucial for advancing geothermal energy and modeling earthquake ruptures. While laboratory experiments have provided key insights into seal formation around the BDT9, geophysical data to pinpoint the BDT, magma-related structures, impermeable sealing formations, and permeable fracture systems controlling hydrothermal fluid pathways remains limited.

Magnetotelluric surveys are widely used in geothermal exploration due to their sensitivity to hydrothermal fluids10. However, their limited spatial resolution restricts detailed imaging of reservoir features, such as localized fractures and sealing layers. For the development of next-generation geothermal power, such as supercritical systems, we should precisely delineate borehole targets within highly heterogeneous lithologies, fracture networks, and supercritical fluid distributions. To enhance spatial resolution in imaging data, active-source multi-channel seismic reflection surveys can be employed1,11. Recent seismic studies have demonstrated their success in investigating geothermal fracture systems12,13, magma-related structures14,15,16, fluid–gas distributions17,18, and geothermal reservoirs1,19. However, such surveys have traditionally been considered unsuitable for mountainous geothermal areas due to the difficulty of deploying seismic sources and receivers in regions with limited road access, as well as the complex subsurface conditions characterized by strong heterogeneities. Especially, limited source-receiver deployment precludes the construction of a 3D seismic volume, which is crucial for investigating the interrelationships among heterogeneous magma-related structures, fluid pathways, and the seal layer of the reservoir. Recently, the Common Reflection Surface (CRS) approach increases the stacking number of seismic traces to improve signal-to-noise ratio even from the limited locations of seismic source and receivers19,20,21, and visualization by such advanced analysis could reveal high-resolution geological structures even in mountainous geothermal fields.

In addition to the static seismic image of geothermal structures, earthquake distribution and its source mechanisms provide crucial insights into dynamic fluid behaviors around the BDT. Fluid migration through fractures changes pore pressure, potentially triggering earthquakes22,23,24,25. Furthermore, detailed investigation of earthquake distribution based on dense seismometer networks can help identify the BDT location26. Integrating such dynamic seismic activity with static seismic images enhances the interpretation of hydrothermal fluid migration.

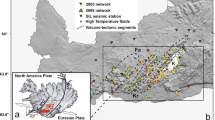

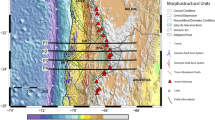

Here, we visualized 3D geothermal structures in the mountainous Kuju volcanic field on Kyushu Island, Japan (Fig. 1), using a 3D active-source multichannel seismic survey and a 3D seismic velocity model, including P-wave velocity (Vp), S-wave velocity (Vs), and their ratio (Vp/Vs). To identify the dynamic fluid behavior, we further estimated earthquake distribution and focal mechanisms based on data from a dense seismic network. The Kuju area comprises several volcanoes and experienced a major andesitic eruption ~1600 years ago, with intermittent eruptions continuing in more recent times27. The region hosts two major geothermal power plants, Hatchobaru and Otake (Fig. 1). The Hatchobaru power plant, with a capacity of 110 MW, is the largest geothermal facility in Japan. Additionally, this field is considered a potential site for future supercritical geothermal energy production26. The heat source for the geothermal power plants is believed to be located beneath Mt. Kuroiwa and Mt. Sensui (Fig. 1)28,29,30. The geothermal reservoir appears to consist of heated meteoric water that has migrated westward through the fault system28. However, the detailed magmatic structures and fluid pathways remain unclear. In this study, we visualized magma-related structures, fracture-controlled fluid pathways, and seal layers of supercritical fluids around the BDT at Kuju volcano. This study not only contributes to the scientific understanding of magma and the associated fluid system but also provides engineering insights by identifying potential targets for supercritical geothermal development.

a Topographic map of Kyushu Island, southwest Japan. b Enlarged view of the Kuju area with geometry of 3D active-source seismic survey and dense seismic network. The white rectangle outlines the 3D active-source seismic survey area (i.e., the gridded zone used for 3D seismic analysis), and the white numbers indicate the inline and crossline numbers. Gray rectangle in b indicates the area shown in Fig. 3. The base map is a 10-m-mesh digital elevation model published by the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan55. These figures were adapted from Tsuji et al.56 and generated using the Generic Mapping Tools57.

Results

Seismic reflection volume

We acquired multichannel seismic data covering the geothermal field (20 × 10 km) in 2022 (Fig. 1). The active seismic surveys faced challenges from the mountainous geography and the limited availability of suitable sites for vibrator source excitation and receiver deployments (blue lines in Fig. 1). Seismic signals generated by three vibroseis sources were recorded by 1270 receivers deployed along the road. To construct a 3D seismic volume from such restricted source-receiver data, we applied the extended CRS method (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2)19,20,21,31. While the shallower formations could not be visualized due to the limitation of source-receiver geometry, the target geothermal reservoir deeper than 2 km below the ground surface was successfully imaged in three dimensions (Figs. 2 and 3). We can visualize the various geological features, including magmatic structures, hydrothermal fluid pathways and seal layer of the pressurized supercritical fluid to the depth of ~10 km below sea level (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Seismic profiles, Vp/Vs and focal mechanisms are shown along two NNE–SSW crosslines: a western side (crossline 63) and b eastern side (crossline 170), and c a WNW–ESE inline (Inline 250). Profile locations are indicated in Fig. 1b. In c the middle panel overlays the reflection profile. White dots mark interpreted faults (F1 and F2). In a blue dots indicate the low-amplitude reflection zone (LARZ), black arrows indicate a horizontal reflector, and red arrows highlights its discontinuities. In b red dots show the high-amplitude reflection zone (HARZ). In c relative location between LARZ and HARZ are shown. Green squares are geothermal power plants. Triangles indicate the seismometer locations, and the color of the triangles indicate the number of earthquake that the seismometer detected.

a Depth slices of the Vp/Vs (color scale) with earthquake hypocenters (black dots) at depths of 1000 , 2000 , and 3000 m below sea level. The location of this area is indicated in Fig. 1b. Triangles indicate the locations of seismometers, and their color indicates the number of earthquake that the seismometer detected. b Depth slices of the seismic reflection volume at depths of 2800, 3600, and 5000 m below sea level. We traced the faults as single lines, although they may in fact represent broad shear zones.

Earthquake hypocenters and focal mechanisms

To evaluate dynamic fluid motion and the BDT, we analyzed earthquake distribution and focal mechanisms with high spatial resolution using data from a dense seismic network (47 seismometers; Fig. 1)26. Although seismic data by dense seismic network have been continuously acquired since 2022, we only used seismometer data collected between May and July 2022 for source estimation. Most earthquakes were concentrated along the western side of the survey area near geothermal power plants, and in the southern area close to active volcanoes (Fig. 3). The estimated focal mechanisms in the region with the highest earthquake density (western part of the survey area) show a mixture of diverse patterns (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S4), suggesting ruptures along the randomly orientated dislocation planes.

Seismic velocity

Seismic velocity models can be derived using a tomographic approach based on earthquake recorded by a dense seismic network (Figs. 2 and 3; Supplementary Figs. S5–S10). These velocity models are valuable for assessing fluid phases (i.e., gas, supercritical, liquid)32,33 and pore pressure conditions34. While Vp can also be estimated from active-source seismic data, the earthquake tomographic approach provides both Vp and Vs in higher accuracy for deeper formations. Therefore, in our interpretation, we relied on seismic velocities obtained through earthquake tomography. The final earthquake locations are determined using the velocity model derived from the earthquake tomography (Figs. 2 and 3). The outstanding anomaly is a plume-shaped zone of extremely low Vp/Vs (<1.4) at depths of 2–3 km below sea level (Fig. 2), located above the high-seismicity region. Additionally, a high Vp/Vs layer extends horizontally beneath and around this seismically active zone.

Discussion

We identified a high-amplitude reflection zone (HARZ) in the 3D seismic volume (red dots in Figs. 2 and 3), extending from 3 to 6 km below sea level (or 4 to 7 km below ground surface). This zone comprises a series of strong seismic reflectors, indicating heterogeneous structures with large seismic velocity contrasts. The HARZ aligns with a low-electric resistivity region interpreted as magma-related fluids (Supplementary Fig. S11)10. While the resistivity anomaly is broad, our seismic data reveal multiple strong reflectors within the HARZ, suggesting repeated magmatic activity that generated multiple intrusions. Its circular shape on depth slices implies a lens-like structure (Fig. 3). Beneath the HARZ, we identified a continuous dipping reflector, which could represent either a fault or a lithological boundary (F1 in Fig. 2). However, considering its linear nature, its intersection with the surrounding geological formations, and the absence of a clear seismic velocity contrast across it, we interpret it as a fault. Since multiple reflectors are observed along the fault, the fault could be thick shear zone with ductile behavior. The fault is oriented NNW–SSE and dips southwest at ~45° (Fig. 3). As it connects to the HARZ and extends southeast toward Mt. Iwo (Fig. 1; the most active volcano in the Kuju area), it may work as a conduit for magma-related fluids ascending from deeper crust.

Interestingly, almost no earthquakes are observed within the HARZ, which we interpret as magma-related structures, likely due to high-temperature, ductile conditions (Fig. 2). Instead, seismicity is concentrated along the western margin of the HARZ and at shallower depths. In the seismic profiles and depth slices, the high-seismicity area is clearly associated with a low-amplitude reflection zone (LARZ) (blue dots in Figs. 2 and 3). The reduced reflection amplitude likely results from open fractures or cracks, possibly caused by elevated fluid pressure. Earthquake focal mechanisms within or above the LARZ show diverse types (Fig. 2), suggesting that seismicity is triggered by upward fluid migration through a randomly oriented fracture system (Fig. 4).

a Seismic profile (crossline number 63; Fig. 2a) with the 5 km depth slice, crossing the high-seismicity area and LARZ. b Interpreted schematic image. The interpreted seal layer, appearing as a distinct horizontal reflector on seismic profiles, is disrupted where it intersects the fault (i.e., LARZ), enabling the upward migration of supercritical fluids and triggering earthquakes. Thus, the LARZ works as permeable window.

Above the seismicity region (or LARZ), we observed a distinct, plume-shaped low Vp/Vs anomaly (Figs. 2 and 3). The lowest Vp/Vs is less than 1.4, which indicates negative Poisson’s ratio. Crack-dominant formation with intense thermal alteration could explain such extremely low Vp/Vs35. Furthermore, this anomaly could be partially caused by gas, because Vp largely decreases due to small amount of gas in the crack33, while Vs remains relatively unchanged. Therefore, supercritical fluids migrating upward through the randomly oriented fractures may cause depressurization and undergo phase transition to gas or liquid (Fig. 4). These observations suggest that seismic activity within the LARZ is closely linked to fluid upward migration and accompanying phase transitions.

Around the LARZ, a continuous horizontal reflector was observed (black arrows in Fig. 2a). This horizontal reflector cuts across the pre-existing dipping geological formations, indicating that it formed subsequent to the original crust. Beneath this horizontal reflector, a relatively high Vp/Vs anomaly is observed. Therefore, the horizontal reflector likely represents a boundary between low and high Vp/Vs regions. The high Vp/Vs below the horizontal reflector could indicate pressurized supercritical fluid (Fig. 4). To further evaluate the fluid status around the horizontal reflector, we estimated the temperature at its horizon using well temperature data (Fig. 1)36. Although the well is located ~2 km far from the horizontal reflector, the estimated temperature (~370 °C) indicates that the fluid beneath the horizontal reflector is in the supercritical phase. Furthermore, the depth of the horizontal reflector is around the BDT, because the BDT commonly occurs around 370–400 °C7. Indeed, earthquakes are not frequent below the depth of the horizontal reflector (Fig. 2), possibly due to ductile behavior. We should note that, even within the interpreted ductile region beneath the horizontal reflector, earthquakes locally occur along the fault, maybe due to the fluid-assisted weakening and localized stress accumulation (Fig. 2c).

At the BDT, the impermeable self-sealed zone may form. This zone separates the deeper ductile, high-pore-pressure region from the shallower brittle zone where hydrothermal fluids (gas) circulate through fractures (i.e., low Vp/Vs)7. The self-sealed zone is primarily controlled by temperature and exhibits a sharp acoustic impedance contrast, allowing it to be identified as the continuous horizontal reflector in the seismic images (black arrows in Fig. 2)37. In addition to this self-sealing mechanism, another type of sealing structure may develop through silica precipitation. As supercritical geothermal fluids rise and cool, the decreasing solubility of silica38 promotes quartz precipitation within the pore space. This process could result in the formation of a low-permeability layer along the fault, further contributing to generate formation of a low-permeability layer.

Although the origin of the horizontal reflector remains uncertain, its role as a sealing layer that traps supercritical fluid and generates high pore pressure provides a plausible explanation for the observed earthquake distribution. Seismicity is concentrated at the disrupted portion of this seal layer (i.e., the LARZ), which forms a permeable window (Fig. 4). This window lies along or above the fault, suggesting that either fault displacement or fluid migration may have breached the sealed layer. Offsets observed in the horizontal reflector at its intersection with the F2-fault (red arrows in Fig. 2) support the occurrence of displacement and the associated generation of fractures. In detail, the F2-fault locates between HARZ and LARZ, and earthquakes align along the F2-fault (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, F2-fault proximity to the youngest volcano in this area (Mt. Kuroiwa; Figs. 2 and 3), it may also work as a recent pathway for upward magma migration. Depth slices (Fig. 3) show that most earthquakes align where the fault intersects the horizontal reflector. Seismic anisotropy results39 further reveal well-developed fractures oriented NNE–SSE, consistent with the fault. This fault may work as a conduit for heated meteoric water migrating from a southeastern heat source, as suggested by previous studies28.

The migration of pressurized supercritical fluid trapped beneath the horizontal reflector layer is further supported by the timing of earthquakes, which appear to correlate with rainfall events26. While no clear correlation is observed between seismic activity and the geothermal power plant operations (i.e., production and injection volumes), indicating that the earthquakes are likely unrelated to such geothermal operations, a notable correlation is evident between earthquake occurrences and rain precipitation (Fig. 5). From May to December 2024, a distinct time lag of approximately 9 days was identified between rainfall events and subsequent seismicity, although the lag time appears to vary over time. Indeed, the shorter time lag was observed in 202226. This observation suggests that increased vertical stress on the geothermal reservoir, caused by rising groundwater levels following rainfall, may elevate pore pressure in the underlying formations and potentially trigger earthquakes. When pore pressure conditions below the seal layer are close to critical, even minor variations in pore pressure can trigger fracturing, thereby increasing the permeability around pre-existing fractures. The hydrothermal fluid trapped beneath the horizontal reflector would then be able to pass through the permeable window within the seal layer. The upward migration of supercritical fluid through the LARZ transfers to gas or liquid, causing the earthquake and thermal alteration. Following upward fluid migration, the pore pressure beneath the horizontal reflector would decrease, leading to reduced seismicity. Thus, the hydrothermal fluid migration through the permeable window and phase transition around the BDT could play a crucial role in the occurrence of earthquakes.

a Temporal variations in earthquake occurrences and rainfall (mm/day), and the corresponding cross-correlation coefficient. The rain is from Global Satellite Mapping of Precipitation (GSMaP) data58. b Temporal variations in earthquake occurrences and geothermal fluid production in this geothermal field (ton/day), and the corresponding cross-correlation coefficient. c Temporal variations in earthquake occurrences and geothermal fluid injection (ton/day), and the corresponding cross-correlation coefficient. A strong correlation is observed between rainfall and earthquake occurrences, with a time lag of about 9 days during the period from May to December 2024.

Our findings demonstrate that an extended CRS approach applied to seismic data with limited source-receiver geometry, combined with precise earthquake localization and seismic velocity analysis, effectively captures critical structures relevant to hydrothermal fluid migration pathway (e.g., permeable window within the seal layer) and dynamic fluid motion and phase transition around the BDT. In addition to advancing scientific understanding of hydrothermal fluid processes, this seismic approach provides a foundation for identifying drilling targets (e.g., supercritical fluids, BDT, and fracture systems) that can reduce exploration risks and support the development of next-generation geothermal systems. Moreover, this approach is applicable to any mountainous volcanic region, even where road access for source-receiver deployment is limited.

Methods

Active-source seismic data and CRS analysis

Seismic survey lines were established along four WNW–ESE-oriented roads and two NNE–SSW-oriented roads, which represent the only accessible routes within the study area (Fig. 1). We utilized three vibroseis (or shot vehicles) for the seismic survey, each with a hold-down weight of 18.6 tons for effective coupling. The seismic source generated sweeps with 6–30 Hz or 6–40 Hz at 855 positions. Other source parameters, such as sweep time are described in Supplementary Table S1. As receivers, we used vertical component geophones with a natural frequency of 5 or 10 Hz at 1270 receiver positions.

The Kuju mountains are characterized by large variations in altitude, and Mt. Nakadake, the highest peak, reaches 1791 m above sea level. As a result, there were considerable differences in the elevations of the shot points and receiver stations. When exploring supercritical geothermal reservoirs, the target depth is interpreted to be greater than 3 km below the surface based on the magnetotelluric surveys. Therefore, a line separation of about 1.5 km reasonably covers the fold map (distribution of midpoints), provided that depths of 3 km or shallower are imaged only along the survey lines. Using the CRS approach, we constructed super gathers from multiple gathers to enhance the fold number even at far from the survey line.

To obtain 3D subsurface images for a seismic dataset acquired in this mountainous area (i.e., limited source and receiver positions), we adopted a series of data processing steps (See Supplementary Table S2 for the processing steps and parameters). As in typical seismic surveys, during data processing, primary wave reflections are imaged40, and wavelet processing, including minimum phase conversion and deconvolution, is applied. The operator of the minimum phase conversion is generated from the reference vibrator excitation signal. Minimum phase conversion suppresses the orthogonal component against the reference signal. Static correction is then applied to eliminate the effects of the weathering layer, specifically the influence caused by shallow, soft sediment. Here, deconvolution was applied to obtain the reflectivity time series (i.e., impulse response) from the recorded seismograms, including the source and receiver. A modified prediction filter, spectral whitening in the time-spectral domain, and a time-variant band-pass filter are applied to extract reflections while suppressing the background and coherent noise components (direct wave, S-waves, and surface wave). On the preprocessed shot profiles (Supplementary Fig. S1) obtained by these data processing steps, the noise components, including refracted waves and air blast, are suppressed. However, the extracted reflected waves were not continuous, presumably due to the volcanic geology in the survey area.

Following the data preprocessing, the extended CRS method was applied19,20,21. Especially, when the source and receiver number are limited or heterogeneously distributed, such as in mountainous geothermal fields, the CRS method that can increase the number of stacked traces (i.e., super gather) is effective techniques for seismic data processing. In the CRS method, reflections in the observed data are approximately expressed by the following travel-time equation.

where

t0 is the zero-offset reflection time at the center common midpoint (CMP) of a super gather, h is half the offset distance between the shot point and the receiver point, Δm is the horizontal distance between the midpoint and the center CMP, and α and β are the emergence angle and azimuth for the zero-offset reflection ray at the surface, respectively. V0 is the propagation velocity at the surface, KN is a parameter associated with the curvature of the zero-offset reflection (the Hessian matrix of travel time for exploring the reflector model), and KNIP is a parameter associated with the offset moveout (the Hessian matrix of travel time for a point source). In Eq. (1), four parameters are unknown: α, β, KN, and KNIP. KN and KNIP are 2 × 2 symmetrical matrices; therefore, a total of eight scalar values are unknown. It is not realistic to analyze eight parameters manually. Therefore, in the CRS method, these unknown eight parameters must be automatically scanned, where the strongest semblance value is obtained.

In the CRS method, reflectivity time series are stacked at the reflection time theoretically calculated using not only the offset but also midpoint distribution with a specified range (we adopted 750 × 750 m). In conventional seismic data processing, the recorded dataset is sorted into CMP ensembles and the root-mean-square (RMS) velocity can be analyzed by semblance values of various RMS velocity on velocity spectrum. In the CRS method, the theoretical semblance as a function of the theoretical travel time (Eq. 1) is composed of the RMS velocity, dip, and azimuth. Moreover, in our extended CRS method, the stacked image is created with the primary, secondary, and third strongest semblances to avoid conflicting dips. Rose diagrams of the fold number (Supplementary Fig. S2) demonstrate that the super gather in CRS method increases the number of folds by roughly two orders of magnitude and improves offset–azimuth distribution. Therefore, the reflection signal could be much enhanced by the stacking.

After we obtained the stacked image, we carried out migration to move the reflection point to its spatially true position. In the CRS method, a velocity model is not directly obtained. Therefore, 3D travel-time tomography was performed separately to obtain the seismic velocity model for the seismic migration process as follows:

-

(1)

The first break in the recorded data was picked.

-

(2)

The travel time was computed using the initial model, in which velocity increases with depth (from 2750 m/s at the surface to 6500 m/s at 3000 m depth). The travel time was calculated using 3D eikonal solvers41.

-

(3)

The initial model was updated by adjusting for the time difference between i) the picked travel time and ii) the computed travel time. The Simultaneous Iterative Reconstruction method42 was used for this inversion process.

-

(4)

Steps (2) and (3) were repeated to estimate final 3D Vp model. In this study, this process was repeated for 30 iterations to confirm to stabilization of the inversion results.

The smoothed 3D velocity model created by the travel time tomography calculations was then used to carry out the depth conversion. On the processed seismic profile, we can investigate vertical scales greater than a quarter of the acoustic wavelength on a reflection seismic profile, based on Rayleigh’s criterion43. With a seismic velocity of approximately 3000 m/s and a maximum frequency of ~30 Hz, the wavelength is 100 m. Consequently, anomalies as small as 25 m in the depth direction can be resolved in shallow part. Since the resolution is decreasing with the depth, the effective resolution around our target zone (i.e., 3000 m depth below sea level) was 50 m.

Deep learning earthquake catalog, focal mechanisms, and 3D travel-time tomography

We accurately estimated earthquake hypocenters using data from a dense network of 47 seismometers deployed within the Kuju volcanic complex26 (Fig. 1). Most of these seismometers were positioned at elevations of less than 1 km above sea level. We deployed the seismometers far from the traffic road to reduce environmental noise. The instruments used were vertical component velocity seismometers with a sampling frequency of 100 Hz, featuring two poles, two zeros, and a natural frequency of 2 Hz. This type of seismometer has previously been successfully employed for fault and volcano monitoring26,44.

To establish an earthquake catalog, we implemented a deep-learning seismic data processing platform, SeisBlue, for automatically picking P- and S-wave arrivals and locating earthquakes45. Using a 1D velocity model26, we then located the sources of earthquakes by the HYPOCENTER program46. The data used span from May 21 to July 27, 2022. A total of 694 events were selected for the earthquake catalog based on the criteria that both P- and S-waves must have at least three arrivals picked. The RMS of the travel time residuals is 0.15 ± 0.04 s, while the standard errors in the epicenter (ERH) and depth (ERZ) are 1.37 ± 1.02 km and 1.02 ± 0.75 km, respectively. The number of recorded P-wave arrivals was 9764, while there were 9057 S-wave arrivals. These data from the earthquake catalog with P- and S-wave arrivals were further utilized to invert a 3D travel-time tomography model.

For the analysis of focal mechanism solutions (FMS) using P-wave polarities, we utilized the SEISAN earthquake analysis software47,48 to determine P-wave polarities for seismic events. Backazimuths and incidence angles of these P-waves were calculated using a three-dimensional velocity model derived from our relocated earthquake catalog, which is described in detail later. Subsequently, we applied the FPFIT algorithm49, along with the FOCMEC software50 and HASH method51, to determine the FMS. To ensure high-quality FMSs, we selected those where at least two of the three methods—FPFIT, FOCMEC, and HASH—produced consistent results. A total of 193 such FMSs were included in this study. The average errors for strike, dip and rake are 5.75 ± 4.00, 5.02 ± 3.31, and 8.12 ± 8.44 degrees, respectively.

3D P- and S-wave travel-time tomography models were developed using the finite-difference arrival time tomography algorithm52,53. Arrival time tomographic inversion is a two-step process. The first step involves determining the locations of earthquakes within an initial model using a grid search method. In the second step, ray-paths from all seismic sources to recording stations are calculated, and this information is used to form a system of linear equations. Solving these equations yields perturbations in P- and S-wave velocities, which leads to iterative relocation of earthquake hypocenters53. The inversion parameters were optimized by testing various grid sizes (0.5 km and 1.0 km), damping values ranging from 50 to 800, and iterations up to 100. After thorough optimization, the final model utilized a minimum grid size of 0.5 km, a damping value of 400, and 22 iterations. The data variance reduced from 0.1908 s2 to 0.1348 s2 (~30%) after 22nd iterations, then the reduction magnitude decreased until 50th iteration with 0.132 s2 (~2%) total variance. The 3D Vp and Vs models are used for evaluating source parameters of earthquake catalog relocation and focal mechanisms to improve our understanding of seismic events.

To assess its resolution, we performed a checkerboard test on the background models employed in the inversion process. The checkerboard pattern consists of cells measuring 2 × 2 × 2 km, with perturbations applied at ±10% anomalies within a central region (1 × 1 × 1 km). Surrounding areas were perturbed by ±5% anomalies within buffer zones extending 0.5 km eastward, northward, and downward from the edges of the central region. The design of the checkerboard cell is followed by Rawlinson and Spakman54. This approach allowed us to evaluate the spatial resolution and reliability of our velocity models in different directions. As a result, the resolution of the models extends down to approximately 5 km depth, with interpretable structures of about 2 × 2 × 2 km in size for both the 3D Vp and Vs models within the study area (Supplementary Fig. S11).

Temperature around the LARZ

Several wells have been drilled in this area. Among these, the DY-5 well (red dots in Fig. 1b)36 provides the temperature data closest to the target. In the DY-5 well, the temperature at a depth of 3000 m is approximately 260 °C, corresponding to a vertical temperature gradient of about 15 °C per 100 m. Extrapolating this gradient linearly to a depth of 3500 m yields an estimated temperature of ~335 °C. Since the LARZ is observed near a hydrothermal upwelling zone, it is reasonable to infer that the temperature in this region reaches the supercritical threshold of water. Moreover, the pressure required for supercritical conditions, approximately 22 MPa, is likely achieved by the hydrostatic pressure at this depth.

Data availability

The active-source seismic data were acquired under the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) project and are directly related to geothermal power production in the Kuju area. To prevent unsustainable geothermal development by third parties and to respect the concerns of local residents, the full dataset of active-source seismic survey cannot be publicly released online. Access to the data may be granted upon request to the corresponding author. However, numerous seismic profile images are provided in the Supplementary Figures, and the key processed results, including estimated earthquake distributions, focal mechanisms, and seismic velocity models, are openly available at the following reposit: https://tsuji-lab.jp/opendata/. The seismometer data used in this study can be obtained from the following repository: https://zenodo.org/records/17011327. The geothermal operation data (production and re-injection volumes) used in Fig. 5 are owned by Kyushu Electric Power Co., Inc., and are not publicly available.

Code availability

The code we used for earthquake estimation can be available from the following URL; https://github.com/SeisBlue/SeisBlue. The codes we used to interpret the 3D active-seismic volume are open software packages (OpendTect ver 6.6.0).

References

Duan, C. et al. A sharp volatile-rich cap to the Yellowstone magmatic system. Nature 640, 962–966 (2025).

Domra Kana, D. J., Djongyang, N., Raïdandi, D., Njandjock Nouck, P. & Dadjé, A. A review of geophysical methods for geothermal exploration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 44, 87–95 (2015).

Zhang, Y. & Zhao, G. F. A global review of deep geothermal energy exploration: from a view of rock mechanics and engineering. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-energ. Geo-resour. 6, 4 (2020).

Reinsch, T. et al. Utilizing supercritical geothermal systems: a review of past ventures and ongoing research activities. Geotherm. Energy 5, 16 (2017).

Elders, W. A., Friðleifsson, G. Ó & Albertsson, A. Drilling into magma and the implications of the Iceland Deep Drilling Project (IDDP) for high-temperature geothermal systems worldwide. Geothermics 49, 111–118 (2014).

Friðleifsson, G. Ó, Elders, W. A. & Albertsson, A. The concept of the Iceland Deep Drilling Project. Geothermics 49, 2–8 (2014).

Fournier, R. O. Hydrothermal processes related to movement of fluid from plastic into brittle rock in the magmatic-epithermal environment. Econ. Geol. 94, 1193–1211 (1999).

Asanuma, H., Muraoka, H., Tsuchiya, N. & Ito, H. The concept of the Japan Beyond-Brittle Project (JBBP) to develop EGS reservoirs in ductile zones. Geotherm. Resour. Counc. Trans. 36, 359–364 (2012).

Meyer, G. G. et al. Permeability partitioning through the brittle-to-ductile transition and its implications for supercritical geothermal reservoirs. Nat. Commun. 15, 7753 (2024).

Aizawa, K. et al. Magmatic fluid pathways in the upper crust: insights from dense magnetotelluric observations around the Kuju volcanoes, Japan. Geophys. J. Int. 228, 755–772 (2022).

Kent, G. M. et al. Melt focusing along lithosphere–asthenosphere boundary below axial volcano. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08865-8 (2025).

Aoki, N. et al. Demonstration experiment of 3D seismic survey in the Yamagawa geothermal field, Butsuri-tansa, 70, 124–141 (Japanese with English abstract), https://doi.org/10.3124/segj.70.124 (2017).

Aleardi, M., Mazzotti, A., Tognarelli, A., Ciuffi, S. & Casini, M. Seismic and well log characterization of fractures for geothermal exploration in hard rocks. Geophys. J. Int. 203, 270–283 (2015).

Magee, C. et al. Magma plumbing systems: a geophysical perspective. J. Petrol. 59, 1217–1251 (2018).

Matsushima, J. & Okubo, Y. Rheological implications of the strong seismic reflector in the Kakkonda geothermal field, Japan. Tectonophysics 371, 141–152 (2003).

Infante-Paez, L. & Marfurt, K. J. Seismic expression and geomorphology of igneous bodies: a Taranaki basin, New Zealand, case study. Interpretation 5, SK121–SK140 (2017).

Tsuji, T. et al. Hydrothermal fluid flow system around the Iheya North Knoll in the mid-Okinawa Trough based on seismic reflection data. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 213, 41–50 (2012).

Mukumoto, K., Tsuji, T. & Hendriyana, A. Large gas reservoir along the rift axis of a continental back-arc basin revealed by automated seismic velocity analysis in the Okinawa Trough. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 9583–9590 (2019).

Krawczyk, C. M. et al. 3-D seismic exploration across the deep geothermal research platform Groß Schönebeck north of Berlin/Germany. Geotherm. Energy 7, 15 (2019).

Jäger, R., Mann, J., Höcht, G. & Hubral, P. Common-reflection-surface stack: image and attributes. Geophysics 66, 97–109 (2001).

Minato, S., Tsuji, T., Matsuoka, T., Nishizaka, N. & Ikeda, M. Global optimisation by simulated annealing for common reflection surface stacking and its application to low-fold marine data in southwest Japan. Explor. Geophys. 43, 59–69 (2012).

De Matteis, R. et al. Pore fluid pressure in St. Gallen geothermal field (Switzerland) based on earthquake focal mechanisms. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL105127 (2024).

El Hariri, M., Abercrombie, R. E., Rowe, C. A. & Do Nascimento, A. F. The role of fluids in triggering earthquakes: observations from reservoir induced seismicity in Brazil. Geophys. J. Int. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2010.04554.x (2010).

Geoffroy, L. et al. Hydrothermal fluid flow triggered by an earthquake in Iceland. Commun. Earth Environ.3, 54 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. Episodic earthquakes controlled by the migration of crustal fluids and fault valve behavior. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL114093 (2025).

Andajani, R. D. et al. Tracking supercritical geothermal fluid distribution from continuous seismic monitoring. Sci. Rep. 13, 8370 (2023).

Kamata, H. & Kobayashi, T. The eruptive rate and history of Kuju volcano in Japan during the past 15,000 years. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 76, 163–171 (1997).

Momita, M. et al. Deep geothermal structure and the hydrothermal system in the Otake-Hatchobaru geothermal field, Japan. In Proc. 22nd New Zealand Geothermal Workshop 257–262 (Geothermal Institute, 2000).

Watanabe, K., Hayashi, M. & Fujino, T. Fission track age of volcanoes in the Kuju volcanic region in relation to geothermal activity. J. Geotherm. Res. Soc. Jpn. 9, 207–217 (1987).

Hirowatari, K. Development-related changes in the Hatchobaru geothermal system, Japan. Geochem. J. 25, 283–299 (1991).

Studer, F., Chasserot, F. & Strobbia, C. Optimisation of 2D foothills imaging and acquisition by the means of common-offset CRS. In Proc. 78th EAGE Conference and Exhibition 1–5 (European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers, 2016).

Chhun, C., Kioka, A., Jia, J. & Tsuji, T. Characterization of hydrate and gas reservoirs in plate convergent margin by applying rock physics to high-resolution seismic velocity model. Mar. Pet. Geol. 92, 719–732 (2018).

Pasquet, S. et al. Multi-scale geophysical imaging of a hydrothermal system in Yellowstone National Park, USA. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 130, e2024JB029839 (2025).

Tsuji, T., Kamei, R. & Pratt, R. G. Pore pressure distribution of a mega-splay fault system in the Nankai Trough subduction zone: insight into up-dip extent of the seismogenic zone. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 396, 165–178 (2014).

Flinchum, B. A. et al. Low Vp/Vs values as an indicator for fractures in the critical zone. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL105946 (2024).

Geological Survey of Japan. Well data compiled from Japan nation-wide geothermal surveys, part 2, logging data and geologic columns data. No 273 (eds Suda, Y & Yano, Y) 131–132 (Geological Survey Japan, 1991).

Piana Agostinetti, N. et al. Discovering geothermal supercritical fluids: a new frontier for seismic exploration. Sci. Rep. 7, 14592 (2017).

Kennedy, G. C. A portion of the system silica-water. Econ. Geol. 45, 629–653 (1950).

Chhun, C., Tsuji, T. & Ikeda, T. Potential fluid flow pathways and the geothermal structure of Kuju revealed by azimuthal anisotropic ambient noise tomography. Geothermics 119, 102932 (2024).

Yilmaz, Ö. Seismic Data Analysis: Processing, Inversion, and Interpretation of Seismic Data https://doi.org/10.1190/1.9781560801580 (Society of Exploration Geophysicists, 2001).

Kim, S. 3-D eikonal solvers: first-arrival traveltimes. Geophysics 67, 1225–1231 (2002).

Trampert, J. & Leveque, J. J. Simultaneous iterative reconstruction technique: physical interpretation based on the generalized least square solution. J. Geophys. Res. 95, 12553–12559 (1990).

Sheriff, R. E. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Exploration Geophysics 4th edn, Vol. 13 (Society of Exploration Geophysicists, 2002).

Iio, Y. et al. Extremely weak fault planes: an estimate of focal mechanisms from stationary seismic activity in the San’in district, Japan. Tectonophysics 723, 136–148 (2018).

Sun, W.-F. et al. Deep learning-based earthquake catalog reveals the seismogenic structures of the 2022 MW 6.9 Chihshang earthquake sequence. Terr. Atmos. Ocean Sci. 35, 5 (2024).

Lienert, B. R. & Havskov, J. A computer program for locating earthquakes both locally and globally. Seismol. Res. Lett. 66, 26–36 (1995).

Havskov, J. & Ottemoller, L. SeisAn earthquake analysis software. Seismol. Res. Lett. 70, 532–534 (1999).

Havskov, J., Voss, P. H. & Ottemöller, L. Seismological observatory software: 30 Yr of SEISAN. Seismol. Res. Lett. 91, 1846–1852 (2020).

Reasenberg, P. A. & Oppenheimer, D. FPFIT, FPPLOT and FPPAGE; Fortran Computer Programs for Calculating and Displaying Earthquake Fault-Plane Solutions. 109, https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr85739 (U.S. Geological Survey, 1985).

Snoke, J. A., Munsey, J. W., Teague, A. G. & Bollinger, G. A. A program for focal mechanism determination by combined use of polarity and SV-P amplitude ratio data. Earthquake Notes 55, 15 (1984).

Hardebeck, J. L. & Shearer, P. M. A new method for determining first-motion focal mechanisms. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 92, 2264–2276 (2002).

Roecker, S., Thurber, C. & McPhee, D. Joint inversion of gravity and arrival time data from Parkfield: new constraints on structure and hypocenter locations near the SAFOD drill site. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, 2003GL019396 (2004).

Roecker, S., Thurber, C. & Roberts, K. Refining the image of the San Andreas Fault near Parkfield, California using a finite difference travel time computation technique. Tectonophysics 426, 189–205 (2006).

Rawlinson, N. & Spakman, W. On the use of sensitivity tests in seismic tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 205, 1221–1243 (2016).

Geological Survey of Japan, AIST (ed.). Seamless digital geological map of Japan 1:200,000. May 29, 2015 version. Geological Survey of Japan, National institute of advanced industrial science and technology (Geological Survey of Japan, 2015).

Tsuji, T. et al. Horizontal sliding of kilometre-scale hot spring area during the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake. Sci. Rep. 7, 42947 (2017).

Wessel, P. & Smith, W.H.F. New improved version of generic mapping tools released. EOS Trans. AGU. 579, 79, https://doi.org/10.1029/98EO00426 (1998).

Kubota, T. et al. Global precipitation map using satellite-borne microwave radiometers by the GSMaP project: production and validation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 45, 2259–2275 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) and was partially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI program (Grant Numbers JP21H05202, JP22H05108, and JP24H00440). J. Ishibashi (Kobe University) gave fruitful comments for the interpretation. We thank Kyushu Electric Power Co., Inc. for their support of the seismometer deployment and for providing their geothermal fluid production and reinjection data (shown in Fig. 5).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T. Tsuji managed the acquisition of the 3D active-source seismic data and the deployment of seismometers. N. Aoki, S. Abe, T. Tsuji, and H. Inagaki designed the active seismic survey. T. Tsuji, M. Katou, A. Hara, and N. Aoki analyzed and interpreted the active-source seismic data. R.D. Andajani and T. Tsuji deployed and managed the dense seismic network. H. Kuo-Chen, Z. Guan, W. Sun, S. Pan, Y. Liu, and T. Tsuji. analyzed and interpreted the dense seismic network data. K. Kitamura and J. Nishijima managed the supercritical geothermal project in the Kyushu area and contributed to the geological interpretation. The manuscript was written and revised by T. Tsuji and reviewed by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Steve P. Jarpe and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Adriana Paluszny and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsuji, T., Andajani, R.D., Katou, M. et al. Supercritical fluid flow through permeable window and phase transitions at volcanic brittle–ductile transition zone. Commun Earth Environ 6, 752 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02774-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02774-4

This article is cited by

-

Unlocking larger flow and higher temperature with enhanced geothermal systems innovation in 2025

Nature Reviews Clean Technology (2026)