Abstract

Subsurface structure investigation on Mars is crucial for understanding its geological evolution and past hydrological conditions. Elysium Planitia (EP), located near the hypothesized ancient ocean shorelines, could contain clues for past water activity and paleoclimate. Here we present better-constrained subsurface models beneath InSight extending to ~800 m depth, obtained from joint inversion of seismic and seismoacoustic coupling data, and use the well-resolved subsurface structure to explore the lithological profile through rock physics models. The derived subsurface lithology agrees well with local geological context and exhibits a shallow 60-m-thick low-rigidity layer consistent with hydrated sedimentary materials. Despite possible contributions of aeolian and volcanic deposits, we favor the interpretation that the low-rigidity layer originated from fluvial activity in EP during the Hesperian or Hesperian-to-Amazonian epoch, as supported by adjacent paleo-shoreline morphology observations. These results hint at a period of warmer paleoclimate at low latitudes, possibly during high-obliquity phases of Mars’ rotational axis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mars’ subsurface structure preserves crucial information on the planet’s geological events, paleoclimate, and paleoenvironment1,2,3. Current knowledge about Mars’ paleoclimate changes and water evolution has largely relied on morphological and spectral observations of the exposed Martian surface4,5,6. However, these observations provide limited insights into subsurface geological units, leaving out key information about the hydrological and temperature conditions at their formation time. Seismological methods provide an effective way to probe the subsurface structure, as demonstrated on Earth and the Moon, where seismic data recorded in-situ provided constraints on subsurface materials from the meter to kilometer scales7,8. On Mars, the success of the InSight mission9,10,11,12 (Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport) provided the fundamental data for the first seismic investigation of Mars’ subsurface structure, offering geophysical constraints that complement geological observations in reconstructing Mars’ paleoclimatic evolution and aqueous history.

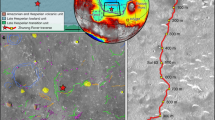

Despite ongoing debate, multiple lines of morphological evidence, along with radar observations from the Zhurong rover in southern Utopia Planitia13,14,15, support the hypothesis that Mars hosted large volumes of water in the northern lowland during the Noachian and Hesperian epochs4,5,6. Elysium Planitia (EP), where InSight landed, is a topographically flat volcanic plain located near the shorelines of a hypothesized ocean (Fig. 1a). The complex geological context of EP consists of volcanic and sedimentary units of Noachian, Hesperian, and Amazonian ages16,17 (Fig. 1c), indicating multiple episodes of volcanic activity, aeolian erosion, and sedimentation during different geological epochs. Geological observations of crater ejecta, scarps, and slopes18,19,20 suggest the presence of layered, weak sediments beneath the overlaying volcanic layer in EP. However, it remains unclear what the material compositions of such sediments could be and at which geological epoch they may have formed. Northwest to EP, the sedimentary Vastitas Borealis Formation unit exhibits kilometer-scale terrain roughness21 and contains fluvial-deltaic features interpreted as debris flow lobes and paleochannel networks6,22,23, indicating the past existence of large-scale water body near EP. Furthermore, spectral observations of Fe/Mg phyllosilicate in the Kalpin crater and at two other locations in EP20, as well as the alluvial deposits in Gale crater24,25, possibly imply a wide distribution of hydrated-mineral subsurface sediments in the surrounding regions of EP (Fig. 1b). Nevertheless, whether the subsurface sediments beneath EP correspond to deposits of hydrated minerals has not yet been investigated in depth.

Terrain texture is drawn using MOLA topography data112. a Geology context of the InSight landing site. Black segments show the fault systems in Cerberus Fossae113. Red and blue curves represent Mars’ hypothesized ocean shorelines for the younger Deuteronilus Level67 and older Arabia Level4, respectively. Mars’ dichotomy boundary114 is plotted in grey. The red triangles mark the locations of Mars missions, the yellow star marks S1222a event33, and the blue starts mark the locations for hydrated minerals20. b Zoomed-in topographic map for the studied region. c Geologic units for the studied region. Information about the geologic units is adopted from Mars’ geologic map115.

Furthermore, subsurface models derived from seismic data support the existence of one or two low-velocity sedimentary layers within 200 m depths of EP26,27. In contrast, studies based on InSight’s seismoacoustic coupling data (i.e., seismic signals associated to the mechanical coupling dynamics between the solid ground and the atmosphere)28,29 tend to provide subsurface models without a shallow low-velocity anomaly (Supplementary Fig. 1). These substantial discrepancies, together with the notable non-uniqueness of the low-velocity layers in these models (Supplementary Fig. 1), lead to a considerable uncertainty in lithological interpretations and accordingly hinder investigations of past water activity in EP.

In this study, we combine seismic and seismoacoustic coupling data from the InSight mission to constrain the subsurface structure and further investigate the lithology profile beneath the InSight landing site. Our results revealed a shallow 60-m-thick low-rigidity layer that exhibits S-wave velocities compatible with hydrated sedimentary materials. Taking into account geological observations, we propose that fluvial activity and a period of warm paleoclimate likely occurred in EP during the Hesperian or Hesperian-to-Amazonian epoch, potentially driven by high obliquity of Mars’ rotational axis.

Results

Data and inversion method

InSight’s seismic and seismoacoustic coupling signals originate from distinct physical processes, making them sensitive to subsurface properties at different depths. These differing depth sensitivities lead to the discrepancies in existing subsurface models. Sensitivity tests confirm that seismoacoustic coupling data predominantly resolve subsurface structures within the upper ~100 m depths, a shallower and narrower depth range compared to seismic data (Supplementary Discussion 1 and Supplementary Figs. 7–9). Nevertheless, the superior shallow-depth resolution of seismoacoustic coupling data can be strategically employed to mitigate the inherent non-uniqueness in seismic subsurface structure inversion. To enhance model constraints, we implement a joint inversion strategy that leverages the complementary sensitivities of multiple data types to different regions of the model space, thereby reducing the non-uniqueness of the inversion problem. This approach has been successfully applied in previous studies of Mars’ crustal structure30,31,32. In this study, we integrate InSight’s seismic and seismoacoustic coupling signals to jointly constrain the physical properties of subsurface structure within the upper hundreds of meters below the lander.

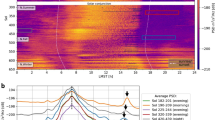

For seismic signals, we adopt the largest marsquake S1222a, which has the advantages of having a high signal-to-noise ratio over a wide range of frequencies33. We extract HVSR (horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio) curves in the 0.4–10 Hz frequency band for S1222a within the P-wave and S-wave spectral windows34 (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3) by applying the HVSR method7,35 (see Methods section). We have identified contamination of the HVSR by Load Shunt Assembly signal of the lander at 9.0 Hz, evidenced by the contaminated signal’s waveform pattern similarity and spectral consistency with known Load Shunt Assembly noise, as well as the signal’s elevated coherence values, which are characteristic of lander mechanical noise (Supplementary Method 1 and Figs. 2–4; see Methods section). After removing the Load Shunt Assembly contamination, we select the more stable S-wave HVSR curve for our inversion (Supplementary Fig. 3). Besides, we observe a minor HVSR trough at around 2.4 Hz induced by the controversial 2.4 Hz signal, whose origin is still debated27,36. As previous works27,36 suggest that the 2.4 Hz signal could originate from subsurface structure resonance, we systematically investigate its effect through two independent inversions.

The presented inversion case applies equal weight coefficients for seismic and seismoacoustic coupling data, thus 0.5, 0.25, 0.25 for horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio (HVSR), convective vortex compliance (CVC), and horizontal-to-vertical infrasound compliance (HVIC), respectively. a Inverted velocities for the shallow 180 m depth. Kernel densities of inverted subsurface velocity profiles are plotted, with orange dashed lines marking the prior velocity ranges and black dashed curves marking the inverted velocity range where the kernel density exceeds 40% of its peak value. The orange dashed lines display depth superposition, reflecting overlapping depth ranges between adjacent layers in the prior model, while the inversion imposes strictly increasing layer depths as a physical constraint. b Lithology profiles for subsurface velocities in (a). Material compositions are indicated for different layers, with numbers within brackets denoting the estimated porosities for the optimal velocities assuming an aspect ratio range of 0.02–0.10 (see Methods section). c Inverted velocities for subsurface 0–3000 m. d Lithology profiles for subsurface velocities in (c). e Kernel density estimates of data fitting for CVC at a wind speed of 4 m s−1. Solid and dashed black curves show the mean values and standard deviations of observations, with misfit ranges at the bottom and mean values in the brackets. f Similar to (e) for CVC at a wind speed of 8 m s−1. g Similar to (e) for HVSR. h Similar to (e) for HVIC. HML1 first high-velocity middle layer, LML low-velocity middle layer, HML2 second high-velocity middle layer, TL transition layer, CIL crustal interface layer, UCL upper crustal layer.

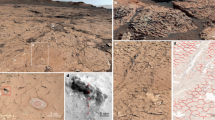

a Fit to the seismic velocities of LML using the cementless sediment model90. The inverted velocity ranges (dashed lines) are from Fig. 2. Velocity predictions for three potential lithological scenarios are presented: (i) basaltic sediment with an initial surface porosity of 0.58 (as estimated in the Methods section), following an exponential porosity-depth relationship100; (ii) basaltic sediment, maintaining a regolith porosity of 0.58 and transitioning to reduced porosities ( ≤ 0.30) in underlying strata; (iii) a mixed-composition sediment of 30% basalt and 70% smectite, with similar depth-reduced porosities from 0.30. b Fit to seismic velocities of LML using the cemented sediment model93 with respect to porosity. Coordination number is determined using an empirical relationship102. The colored curves show velocity predictions for three lithological scenarios: (i) a mixed-composition sediment of 30% basalt and 70% smectite with 0.3% kaolinite cement within pores; (ii) similar to (i) but with 1.0% kaolinite cement within pores; (iii) a mixed-composition sediment of 30% basalt, 50% smectite, and 20% halite with 0.3% kaolinite cement within pores. Dashed and solid lines denote Hashin-Shtrikman upper and lower bounds, respectively. These predictions are calculated using the constant-mode cementation. For comparison, Supplementary Fig. 16 presents results for the contact-mode cementation, which yield substantially larger velocity predictions than the constant-mode cementation presented here. c Fit to seismic velocities of LML similar to (b) but for various single-phase cemented sediments. d S-wave velocity predictions using the self-consistent fractured rock model94,95 for various lithological compositions with respect to porosity. Results for pore/grain aspect ratios (AR) at 0.02 and 0.10 (the adopted range in the Methods section) are presented. AR values higher than 0.10 lead to higher velocities at the same porosity, further deviating from the low velocities of LML. The horizontal dashed line represents the upper limit of porosity estimation (0.40) for exposed Martian basalts54,55,56. Results using the differential-effective-medium fractured rock model96,97 are presented in Supplementary Fig. 16, which obtains slightly higher velocity predictions (more reliable at high porosities; see Methods section). The pore-filling materials consist of a mixture of 99.5% gaseous CO2 and 0.5% cement (mineralogically identical to the host mineral), consistent with the mineralogical compositions adopted in Supplementary Fig. 16. Vertical grey dotted lines in (b)–(d) mark the optimal velocities for the inverted subsurface layers as shown in Fig. 2, with the horizontal line segments displaying the velocity uncertainty. Layer abbreviations are the same as those in Fig. 2.

Depth is not to scale. a Initial crust layering due to surface alteration before the Hesperian epoch. b Volcanic activity in the Early Hesperian epoch formed a basaltic layer (HML2), which became porous under surface modifications such as meteorite impacts. However, a sedimentary origin involving reworked basaltic materials remains a plausible alternative interpretation. c Fluvial sediments deposited during the Hesperian or Hesperian-to-Amazonian epoch, possibly related to the presence of water in Mars’ equatorial regions at a time of high obliquity of Mars’ rotational axis. d Volcanic activity during the Early Amazonian epoch formed another basaltic layer with less porosities. e Regolith production by impact gardening and aeolian erosion until present. Layer abbreviations are the same as those in Fig. 2.

Seismoacoustic coupling signals refer to the seismic response of the solid ground excited by a pressure perturbation. The transfer function from atmospheric perturbation to ground deformation is known as compliance37,38, and can provide constraints on physical properties in the subsurface (see Methods section). We use compliance data from two existing measurements (Supplementary Method 2 and Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). The first one is the convective vortex compliance26, obtained between 0.05 and 0.5 Hz for the vertical component under wind speeds of 4 and 8 m s−1. The second one is the ground compliance caused by infrasound waves28 generated by the so-called S0986c impact event, measured between 0.5 and 2.0 Hz. In this particular case, the horizontal-to-vertical ratio of the infrasound compliance is used as a substitute since the absolute compliance values are inaccessible in the absence of pressure recordings (Supplementary Method 2).

Our inversion scheme integrates the three datasets with distinct physical units and measurement precision by normalization of each dataset using its observed standard deviation-derived misfit metric and implementation of dataset-specific weight coefficients (Supplementary Method 3 and Supplementary Discussion 2). On the basis of the model prior information provided by the HP3 hammering experiments on Mars’ surface39,40 and receiver functions for Mars’ crust30,32,41, our subsurface model is parameterized with a top regolith layer, seven middle layers, and two crustal layers down to 3 km, with proper search ranges for the S-wave velocity and depth of each layer (Supplementary Method 3 and Supplementary Table 1). The seven-layer parameterization of the middle regions is sufficient to resolve discrete velocity contrasts with less than six interfaces, such as the three-layer velocity structure in previous models27, while accommodating gradual velocity gradients. P-wave velocities and densities are determined empirically based on S-wave velocities when lacking in-situ references (Supplementary Method 3). We implement the inversion with the neighbourhood algorithm42,43, which has the advantage to conduct self-adaptive search in multi-dimensional model space and obtain an ensemble of models with equally acceptable data fitting (see Method section).

Inverted subsurface structure

Our inversion tests demonstrate a robust velocity pattern characterized by a persistent sandwiched low-velocity anomaly (VS around 500 m s−1) in the upper 100 m depth across varying parameter configurations, including variations in both weight coefficients and the inclusion/exclusion of the 2.4 Hz signal (Supplementary Discussions 1–3 and Supplementary Figs. 10–14). We focus our analyses on the inversion case that retains the 2.4 Hz signal (regarding it as a structural resonance) and achieves the optimal joint fitting to both seismic and seismoacoustic coupling data. Meanwhile, we employ the inversion case excluding the 2.4 Hz signal to quantify associated uncertainties of inverted velocities (Supplementary Discussions 2 and 3). The resulting models resolve into seven layers based on the S-wave velocities, each corresponding to a different geological unit (Fig. 2a–c).

The top layer has exponentially depth-increasing S-wave velocities, with a surface velocity of 60 m s−1 (40–80 m s−1 range where kernel density exceeds 40% of peak) increasing to 275 (200–300) m s−1 at the bottom of 9 m depth (Fig. 2a). The depth-increasing velocity characteristic corresponds to unconsolidated materials on the surface which become more consolidated at depths under gravity compaction44. Sensitivity tests show that the combined datasets have good constraints for both the thickness and basal velocity of the top layer (Supplementary Discussion 1), which can contribute to further lithology analysis of the top layer.

The middle three layers are the focus of our study. The joint inversion yields a 14-m-thick first middle layer (HML1), a 60-m-thick low-velocity middle layer (LML), and another 97-m-thick high-velocity layer (HML2) with S-wave velocities of 1700 (1125–2250), 425 (330–600), and 775 (500–1350) m s−1, respectively. The inversion case excluding the 2.4 Hz signal produces a 20-m thinner LML with 55 m s−1 faster S-wave velocities (Supplementary Discussion 3). Sensitivity tests show that this high-low-high velocity pattern within the depth range of 9–180 m (Fig. 2a) is necessary to explain the adopted geophysical observations (Supplementary Discussion 1). Such a velocity pattern is consistent with a sedimentary layer between overlaying and underlain rock strata, potentially recording past depositional processes. Previous studies26,27 resolved this sandwiched low-velocity layer with S-wave velocities spanning 170–780 m/s within the 20–70 m depth (Supplementary Fig. 1), where the broad velocity range reflects considerable inversion non-uniqueness influenced by prior model parameter choices. Consequently, although these studies interpreted the low-velocity layers as sedimentary deposits26,27, this conclusion remains uncertain due to the inherent ambiguity in velocity structure, thereby limiting robust lithological analyses. Our joint inversion reduces the non-uniqueness in both inverted velocities and depths of the middle layers, particularly for the low-velocity layer where the S-wave velocity uncertainty currently spans from 330 to 600 m s−1 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Discussions 1–3). It thus provides more reliable velocity estimates for investigating the material compositions of such low-velocity sedimentary layer.

Beneath the middle layers are three bottom layers, involving a transition layer (TL), a crustal interface layer (CIL), and an upper crust layer (UCL) with S-wave velocities of 775 (500–1350) m s−1, 1600 (1500–1750) m s−1, and 2300 (2050-2500) m s−1, respectively (Fig. 2c). Unlike previous models that commonly employed a half-space approximation below shallow depths (100 or 300 m), our model resolves velocity transition zones continuously extending to crustal layers. The observed S-wave velocity variations within the transition layer can be interpreted as a gradual velocity increase with depth until reaching the CIL ( ~ 800 m depth), an intermediate velocity pattern that successfully fits the observed P-to-S receiver functions45. Our joint inversion reveals no sharp velocity discontinuity above ~800 m, but cannot resolve whether potential deeper discontinuity exists (Supplementary Discussion 1 and Supplementary Fig. 9). Below ~800 m, the inverted velocity ranges approach the prior bounds, indicating weak data sensitivity to structures beneath this depth.

Lithological interpretation

The well-constrained seismic velocities obtained through our joint inversion promotes further lithology analyses of the subsurface materials. We perform lithology analyses using a rock physics model approach46 that utilizes effective medium theories for granular models (sediments) and inclusion-based models (fractured rocks). These rock physics models provide quantitative predictions of seismic velocities based on the mineralogical compositions and mesoscale geometry characteristics of sediment and rock assemblages. These models are sensitive to the host material (the interconnected, load-bearing solid framework) and the pore-filling media of the geological assemblages. Our inversion scheme merely resolves only S-wave velocities, as the employed seismic and seismoacoustic coupling data exhibit limited sensitivity to bulk density and Poisson’s ratio (or VP/VS ratio)27,28,29,47,48. Subsequently, we apply this rock physics modelling approach to estimate the mineralogical compositions corresponding to the inverted S-wave velocities.

Our analyses primarily assume the widespread Martian basalt as the host material, while alternative host materials are considered only when encountering property mismatches. The derived lithology interpretations for both the top <9 m and three bottom layers ( > 180 m) demonstrate good consistency with in-situ experiments and geological observations beneath the InSight landing site (see Method section). Based on our model, the top layer can be interpretated as a cementless basaltic sedimentary unit formed through prolonged surface weathering effects (Supplementary Fig. 15). The three bottom layers likely represent distinct geological units: (a) a basaltic sedimentary unit or highly-fractured basalt (TL), underlain by (b) a fractured basaltic unit (CIL) with moderate porosity, and (c) a deeper fractured basaltic layer (UCL) with the lowest porosity (Fig. 2d, 3d), although alternative lithological interpretations cannot be ruled out (see Methods section). Building on these reasonable results, we further apply the rock physics model to investigate the lithology of the high-low-high velocity structure in the three middle layers.

HML1 and HML2 exhibit S-wave velocities that can be explained by fractured basalts with moderate and high porosities, respectively (Fig. 3d), if assuming a laboratory-estimated pore aspect ratio range of 0.02–0.10 (characterizing thin pores) for Martian basalt analog49,50 (see Method section). Thus, the shallower HML1 may represent a basaltic rocky unit, which is consistent with the presence of a shallow, mechanically competent rock-producing layer, as indicated by the fresh rocky ejecta craters in EP18,19,51. This layer formed during the Early Amazonian epoch (~.17 Gyr)19 and was subsequently fractured by impact and aeolian processes, leading to the formation of present-day surface regolith. We also assess the alternative interpretation that HML1 could correspond to sedimentary units. The S-wave velocities of HML1 are compatible with basaltic sediments containing either moderate constant-mode cements (cements coating grain surfaces) or minimal contact-mode cements (cements limited to grain contact points), as demonstrated by our rock physics modeling in Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 16a. However, the sedimentary interpretation is disfavored because sedimentary materials lack the mechanical competence to generate the observed rocky ejecta crater morphology18,19,51 and no geological evidence has been identified for extensive aqueous sediment deposition in EP during the inferred Early Amazonian epoch17,18. For the deeper HML2, we rule out the possibility of intrusive volcanic flows because intrusive volcanic rocks typically exhibit higher seismic velocities than the one of HML2. Instead, HML2 better correlates with a geologically older, highly fractured volcanic unit that experienced substantial alteration. This interpretation is consistent with the Early Hesperian volcanic basement unit52,53 of EP, dated to 3.6 Gyr, which exhibited enhanced weathering due to the elevated impact rate of the Early Hesperian epoch27,52. If supporting the sedimentary interpretation, the relatively low velocities of HML2 can be satisfied by a basaltic sedimentary unit with minimal cementation around grains (Fig. 3c). Consequently, we favor the interpretation that HML1 is most likely an Amazonian volcanic flow unit and HML2 may be volcanic flow or basaltic sedimentary unit of Hesperian age (Fig. 4).

Accordingly, the LML sandwiched between HML1 and HML2 accounts for low-rigidity materials during Early Hesperian to Early Amazonian. We discard the interpretation of fractured basalts because an extremely high porosity (over 0.40; Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 16b and Supplementary Table 2) would be required to match the optimal velocities of LML (425 or 480 m s−1), exceeding the upper limit of porosity estimation for exposed Martian basalts54,55,56. Alternative lithological interpretations for the low S-wave velocities in LML include cementless sedimentary units comprising purely basaltic material or a basalt-smectite mixture (Fig. 3a). However, the 60-m-thickness of LML (40-m-thickness for the inversion excluding the 2.4 Hz signal; Supplementary Table 2) is larger than the common thickness range of surficial cementless layers around InSight19,20 (from 3 to 30 m) and the thickness predicted by a regolith production model19,57 from Early Amazonian to Early Hesperian ( ~ 19 m). All these results imply that LML is not merely composed of aeolian and pyroclastic deposits.

Among the minerals detected in EP (Supplementary Table 3), only smectite and halite minerals could satisfy the low velocities of LML, either as fractured rocks (porosity <0.40) or cemented sediments (Fig. 3c, d). The subsurface temperature condition on Mars (200 K) are substantially lower than terrestrial diagenesis conditions ( > 273 K), potentially inhibiting the rates of mineralogical alteration. We therefore interpret the LML as cemented sediments containing smectite and halite minerals. This inference is also supported by Martian geological observations. Fe/Mg smectite is found to occupy the majority among all detected hydrated minerals on Mars58. Additionally, clay-bearing sediments could originate from the Fe/Mg phyllosilicates, which have been detected in two sites of EP and the Kalpin crater20,59 (Fig. 1a, b), as well as in Gale crater60. Spectral observations also reveal that halite minerals are widespread near the dichotomy61 and in Gale crater62. All these geological observations favor the scenario that cemented sediments of hydrated minerals could be retained as the host materials of LML.

Our analysis reveals several feasible clay-bearing mineralogical compositions that match the LML velocity range. We find that a sediment mixture of 30% basalt and 70% smectite with 0.3% kaolinite cementation (in constant mode) predicts velocities compatible with LML values (Fig. 3b). For comparison, the identical compositions without cementation (cementless model; Fig. 3a) yields velocities at the lower bound of the LML range, while increasing cementation to 1.0% produces velocities approaching the upper bound (Fig. 3b). Crucially, contact-mode cementation scenario systematically overpredicts velocities outside the LML range even with minimal cementation (Supplementary Fig. 16a). These results demonstrate that minimal constant-mode cementation (0.3–1.0% cementation around grains) is a robust requirement for interpretating the LML velocities, possibly due to inhibited cementation kinetics under Mars’ low-gravity, low-pressure, and cryogenic subsurface conditions.

However, we emphasize here the difficulty in uniquely constraining the mineralogical compositions of LML based on solely S-wave velocities. As demonstrated by the case of 20% halite addition, while producing moderately higher velocities, the velocity predictions remain within the LML range (Fig. 3b). Similar limitations apply to characterizing the pore-filling fluids and cements within the basaltic layers HML1 and HML2, in which cements of water ice and calcite yield similar velocity predictions (Supplementary Discussion 6). Although the composition of pore-filling materials remains ambiguous, this uncertainty does not affect our lithological interpretation of the LML host material, as our analysis is based on the lower-bound velocity estimates derived from gas-filled pores. Additional constraints from bulk density and Poisson’s ratio would better resolve the non-unique mineralogical composition.

Implication for Martian paleoclimate and hydrological evolution

The hydrated minerals in LML could be transported from the southern highland, where previously formed hydrated minerals are widespread63, or be the result of in-situ water-rock interaction, or of a mix of both processes. Each case indicates that LML is associated with past fluvial activity in EP. The occurrence time of the fluvial activity remains poorly constrained and speculated to be between the Early Hesperian and Early Amazonian epoch (Fig. 4c). The InSight landing site lies proximal to the hypothesized Arabia shoreline4 formed during the Late Noachian and Early Hesperian epochs (Fig. 1a). Besides, numerous studies in the Aeolis Dorsa region, situated between the western Medusae Fossae Formation, have identified fluvial sedimentary deposits that were interpreted as the evidence of Early Hesperian sea-level fluctuations64,65,66. Thus, a plausible hypothesis is that LML may represent nearshore sediments associated with the Late-Noachian-to-Early-Hesperian Arabia Level shoreline (Fig. 4d). Another hypothesis is that the fluvial sedimentary deposits of LML may date back to the Late-Hesperian or Hesperian-to-Amazonian epoch, potentially correlating with the hypothesized Hesperian-aged Deuteronilus ocean67. Despite being distal to the Deuteronilus shoreline, fluvial activity may have persisted regionally in EP, as supported by contemporaneous geological observations, including the observed Late-Hesperian and Amazonian clay formation across Mars1,58,68, Late-Hesperian-aged (3.2–3.3 Gyr) fan deposits found at Gale crater24, and extensive Hesperian-to-Amazonian fluvial light-toned deposits in the western Medusae Fossae Formation69. We inferred that the fluvial processes possibly represented a widespread surface feature of the EP region during its wet climatic intervals, while subsequent volcanic flows erased much of the fluvial record.

From a paleoclimatic perspective, fluvial sedimentation implies stable existence of liquid water over a period of time. The freezing point of water stabilizes at around zero Celsius degree for the pressure range between ~611 Pa and 10 MPa. Thus, considering a Martian atmosphere pressure comparable to present ( ~ 700 Pa) during the Hesperian and Amazonian epochs, the inferred fluvial activity implies a period of warm paleoclimate in the EP region, allowing liquid water to exist. The deductive occurrence time of such warm paleoclimate aligns with the Middle-Hesperian fluvial deposits discovered in Gale crater24,70 and the Late Hesperian-Early Amazonian paleo-polygon terrain detected by Zhurong’s rover radar in southern Utopia Planitia15. Furthermore, combining with additional Hesperian-to-Amazonian fluvial features documented in Mars’ low-latitude regions71,72, these observations suggest that relatively warm climatic conditions likely persisted intermittently until the Hesperian-to-Amazonian epoch across multiple low-to-mid latitude locations on Mars. Such warm paleoclimate conditions may be linked to periods of high Martian obliquity, as numerical modeling suggested that obliquity reached about 60° between 3.0 and 4.0 Gyr73. Assessing the durations of individual warm periods in EP remains challenging without additional observations. Current inference, anchored to Gale crater’s lacustrine chronology (less than thousands to million years)70, lacks spatiotemporal resolution for different geological conditions. Future studies should incorporate observations from diverse geological periods and locations to better constrain Mars’ paleoclimate variability.

Methods

This section includes the technical details for data processing, subsurface structure inversion, and lithological interpretation. The content is organized as follows: (a) InSight seismic data processing procedures; (b) theoretical framework and application of the horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio method in a diffused wavefield; (c) theoretical basis and implementation of ground compliance for convective vortices and impact-generated infrasound waves; (d) theoretical foundations of the neighbourhood algorithm for seismic inversion; (e) theoretical basis of rock physics models employed in this study; (f) lithological characterization of the top regolith layer; and (g) lithological interpretation of the bottom layer from inversion. Subsections (a)-(d) outline the methods to process seismic data and conduct the subsurface structure inversion, while subsections (e)-(g) provide the lithological analysis techniques applied to the subsurface structure, along with their specific implementations.

Seismic data processing

We use raw Mars seismic data from open-source databases74,75. We then remove the tick noise, mean values, and linear trend. Similar to previous study76, we derive the tick noise waveform by averaging normalized 100-sample-per-second Very Broad Band records acquired during seismically quiet periods (18:00-24:00 local time). The obtained tick noise is then systematically subtracted from all original seismic records. Finally, we apply a second-order Butterworth bandpass filter in 0.01–49.5 Hz, remove the instrument response to obtain ground displacement and acceleration records, and rotate to Z, N, E components.

We calculate multiple spectral estimates. The amplitude spectra of ground displacements and power spectral densities of ground accelerations are computed within the P-wave and S-wave time windows (68.5 s and 341.4 s in length, respectively) of the S1222a event34, using Fast Fourier Transform and the Welch’s method77. We also obtain an estimate of the cross-component coherence values. For all these calculations, we apply a 4096-point sliding time window technique with 80% overlap between the neighbouring time windows. The coherence between two signals x(t) and y(t), Cxy(f), is calculated as the ratio between their squared cross power spectral densities, Pxy(f), and the product of their power spectral densities, Pxx(f) and Pyy(f):

These coherence values, derived from the power spectral densities of ground accelerations, represent dimensionless ratios (between 0 and 1) that quantify the correlation between two signals at each frequency. Lander-generated mechanical noises typically exhibit high coherence values across multiple components (Supplementary Method 1 and Supplementary Fig. 4), making this parameter a useful preliminary indicator for identifying potential mechanical noise contamination in seismic records.

Horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio and diffused field assumption

The processed seismic data are subsequently used to calculate the horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio (HVSR) curves, which serve as the fundamental seismic constraints for our subsurface structure inversion. The traditional HVSR method is based on measurements of the ratio between the root-mean-square horizontal Fourier spectral amplitude and the vertical Fourier spectral amplitude for ground velocity records7,35. Variations in the horizontal-to-vertical velocity energy partition are caused by the wave reverberations in the subsurface structure and can therefore reflect certain subsurface physical properties78,79.

We use the diffuse field approximation (DFA) method80 as the forward modelling method of the HVSR curve. The DFA method assumes an equipartitioned wavefield, where the excitation energy of different types of seismic waves at one frequency is statistically equal to those in the neighborhood frequencies81. Under the DFA assumption, the horizontal and vertical kinetic energy densities at each frequency can be obtained for a given subsurface model81,82. Since the kinetic energy density is proportional to the power spectra density, the DFA methods can be used to calculate the horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio curve. In this case, the power spectra instead of the square of the Fourier spectra is used to calculate the HVSR curve27, i.e.:

where \( < \parallel {u}_{i}\left(f\right){\parallel }^{2} > \) denotes the power spectra density in the i direction (i = Z, N, E), Ei(f) denotes the kinetic energy density at the frequency f from the DFA calculation.

The DFA method is applicable to marsquake coda waves because the seismic coda waves quickly reach the status of energy equipartitioning due to scattering83. The DFA method has the advantage to naturally consider the contributions of the different wavefield components on the HVSR curve27, in comparison to methods considering only Rayleigh wave26. HVSR observations are obtained from equation (2). By definition, HVSR values represent dimensionless ratios and are therefore independent of the physical units used in power spectral density calculations. Multiple HVSR curves are calculated using a 4096-point sliding time window with 80% overlap, in the noise, P-wave, and S-wave time windows34 of S1222a. We then obtain the mean values and standard deviations of these HVSR curves from the statistics of all time windows. The inversion also requires a forward model of HVSR given a certain subsurface model. Synthetic HVSR curves are calculated from Eq. (3), where the horizontal and vertical kinetic energy partition of all types of seismic waves are obtained using the DFA code developed by Margerin 81.

Ground compliance and impact infrasound coupling

This subsection details the additional seismoacoustic constraints utilized in our inversion. The motion of the ground in response to a pressure perturbation in an overlying fluid layer (the atmosphere in this study) is commonly expressed by the compliance. The response process can be quasi-static (leading to low-frequency ground deformation), if the pressure perturbation has a lower horizontal speed than the seismic velocities, or dynamic (causing seismic waves excitation), if the pressure perturbation has a larger horizontal velocity, as is the case for an acoustic wave.

Compliance is defined as the ratio between the vertical (resp. horizontal) particle velocity in the ground and the vertical stress exerted by the atmosphere on the ground surface and is expressed in the frequency domain. Sorrells’ theory37,38 achieved the first analytical derivation of compliance for the case of quasi-static loading by a horizontally-moving source over homogeneous and layered media. A theory of compliance valid for both static and dynamic loading, was discussed in Tanimoto 84 for a half space and unified in Xu & Lognonné 85 for a layered medium. In Xu & Lognonné (2024)’s approach85, the compliance function is derived from the equations of motion in the elastic media, with plane wave assumption for surface perturbations and ground displacements. A forward model of compliance can be obtained using the propagator matrix method, also known as the Haskell propagator, to integrate the differential system28,48,86. This method takes advantage of the fact that the subsurface is a succession of homogeneous layers over a non-reflective half-space to conduct the integration.

We use the propagator matrix method in this study. In the case of convective vortices, we calculate the vertical compliance function between 0.05 and 0.5 Hz for two wind velocities of 4 and 8 m s−1. We then normalize the compliance values by the wind speeds following Onodera et al. 29. In the case of the impact-generated infrasound waves, we calculate the horizontal-to-vertical ratio of the infrasound compliance of S0986c, as the absolute compliance values are not available (Supplementary Method 2). Xu et al. 28 provide the atmosphere model and the associated phase velocity of the infrasound waves between 0.5 and 2.0 Hz during the impact S0986c. The phase velocity of the impact infrasound waves guided in the lower Martian atmosphere is dispersive47. Again, we use the propagator matrix method to calculate horizontal and vertical compliance as well as their ratio in 0.5-2.0 Hz.

Neighbourhood algorithm

After obtaining the seismic and seismoacoustic constraints, we perform subsurface structure inversion using the Neighbourhood algorithm (NA) method42. NA method is a derivative-free search method to find models with acceptable data fitting in the multi-dimensional model space. The NA method is based on the neighbourhood approximation, i.e., using the model samples of the previous iteration to approximate the misfit values within a neighbouring regional model space of these model samples. Such a neighbouring regional model space of each model sample is determined using the Voronoi diagram87 and is called Voronoi cell. The misfit approximation, instead of forward modelling to get the actual misfit, is used to generate the next iteration of model samples within each Voronoi cell. It is noted that the neighbourhood approximation can be combined with any direct search sampler to generate model samples, such as the Markov-chain random sampler88 and the uniform random sampler42. We follow Sambridge 42 to use the uniform random sampler in our inversion. The iteration of model samples continues until the misfits become acceptable or the total number of model samples is large enough.

The NA method requires only two control parameters (the lower and upper limits) to define one dimension of model space. Besides, the NA method is self-adaptive to the size of the parameter search ranges, regardless of how irregular the distribution of previous model samples is. Another advantage of the NA method is to obtain an ensemble of models that all fit the data well instead of a single inverted model. This can provide the uncertainty of the inversion. The dinver tool of the open-source Geopsy package89 incorporates an improved NA method43 that can optimize the model sampling. We use the dinver tool of the Geopsy package (version 3.5.0) to conduct the NA inversion with our forward modelling codes. In our inversion, the NA method starts with an initial set of 200 random model samples in the model space and then conducts multiple iterations of model samples until reaching a total of twenty thousand model samples. For each NA inversion case, we search for twenty thousand models and use the optimal 5% to calculate the uncertainty of model distribution. The parameter search ranges are set based on the model prior information in Supplementary Method 3.

Rock physics model

Subsequently, we employ a rock physics model method to derive quantitative lithological interpretations from the inverted seismic velocities. The rock physics model enables to predict the effective elastic moduli of sediment or rock assemblages that are composed of multiple constituents, including host grains, pore space, and potential cements within pore space. After obtaining the effective moduli, the seismic velocities can be calculated using the following equations46:

where \({\phi }_{i}\) and \({\rho }_{i}\) are the volume fractions and bulk densities of the ith constituent, and \({K}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}\) and \({\mu }_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}\) are the effective bulk and shear modulus of the assemblage, respectively.

In the cementless sediment model, grains are viewed as a random pack of spherical grains compacted by compressional pressures, without cements in the pore space between grains. The effective moduli of cementless sediment model can be obtained by applying the Hertz-Mindlin contact theory90. This theory assumes that all grain contacts are identical and calculates the effective moduli based on mechanical relationships at grain contacts. The obtained moduli have a positive correlation with increasing compressional pressure. A series of mathematical formulations has been well documented for the cementless model, known as the Hertz-Mindlin model90. To apply this model, we need to determine the physical properties of host grains, coordination number (the average number of grain contacts per grain in the assemblage), porosity, and the applied compressional pressure. In practical applications, two additional corrections are considered for the Hertz-Mindlin model. The first correction introduces a frictional contact coefficient f (0 ≤ f ≤ 1) to quantify the portion of rough grain contacts exhibiting tangential friction46, where f = 1 means all grain contacts are rough (with full tangential friction) and f = 0 mean all grains are smoothly contacted without tangential friction. The second correction incorporates grain asperities to better represent realistic grain shapes through two asperity parameters, root-mean-square height and microhardness of the contact surface asperities91. This modified Hertz-Mindlin model is valid for pressure conditions in the kPa pressure range92, consistent with the overburden pressure regime of the Martian regolith layer. In the next section, we employ this model to explore the lithological parameters that best reconcile with our inverted top regolith layer.

For the cemented sediment model, cements exist in the pore space, strengthen the grain contact, and elevate the effective moduli. Cements can either embay grains (constant mode) or concentrate at the grain contact (contact mode), depending on which pattern better matches the studied case. A cementation contact theory93 provides the mathematical formulations that well describe the effective moduli of grain packs with small portions of cementation. The cementation contact theory is inherently independent of external pressure. Even minor cementation can substantially strength the elastic moduli of granular materials, maintaining the pressure resistance up to at least 23 MPa for Oseberg Field sandstones93. Thus, this model is applicable to Martian shallow subsurface environments ( < 200 m depth), where the confining pressures are less than 2 MPa. Model implementation requires to define lithological parameters including the host grain properties, cement properties and cementation content, porosity and pore-filling fluids (in this study, gaseous CO2).

The effective moduli of fractured rocks are quantitatively estimated through inclusion-based micromechanical models for wave propagations. One commonly used model is the self-consistent model94,95, which approximates the pore interaction by replacing the background medium with a yet-unknown effective medium. The self-consistent model performs well at low porosities but underestimates effective moduli at high porosities, as it overestimates inclusion interactions. A differential-effective-medium model96,97 resolves this defect through progressive replacement of the background medium by small frictions of inclusions. The mathematical formulations for both rock models are summarized in literature46. For the self-consistent model, the formulations are iteratively solved until the difference of effective moduli values becomes small enough between two iterations (e.g., relative error is less than 1.0e-6). The differential-effective-medium model is formulated as a system of differential equations, which can be solved using standard numerical methods. The implementation of these models requires specification of constituents (minerals or fluids), constituent volume fractions, porosity, and pore/grain geometries (aspect ratio). The aspect ratio ranges from nearly zero (thin shape) to 1.0 (spherical shape). Laboratory measurements of Snake River Plain basalt samples49, tested under differential pressures of 3.4–17.2 MPa, provide a valid analog for Martian basalts50. These experimental results derived pore aspect ratios spanning 0.02–0.10. The shallow subsurface pressures investigated in this study ( < 200 m depth, <2 MPa) falls below the experimental pressure range (3.4–17.2 MPa). Nevertheless, given that inclusion-based models have been successfully applied to sandstone experimental data98 across a broader pressure range of 0–110 MPa, we assume a same pore aspect ratio range (0.02–0.10) in our analyses.

In the granular model framework, the estimated elastic moduli represent properties of the dry sediment matrix, assuming zero-modulus pore-filling fluids46. While Gassmann’s equations99 can be applied to account for the pore-filling fluids (gaseous CO2 here), the elastic properties of gaseous CO2 under Martian surface conditions (low temperature-pressure conditions) have negligible impact on the effective moduli.

Under self-compaction condition, the porosities decrease exponentially with increasing depth100:

where z denotes depth (unit: kilometer), \({\phi }_{0}\) is the porosity at the surface (z = 0), and the porosity reduction constant k is 2.82 for Mars’ gravity101. Considering that we focus on structures within the shallow hundreds of meters, the porosity reduction can almost be neglected. The coordination number C in the granular assemblage can be obtained based on the relationship102 with porosity \(\phi\):

This empirical relationship is derived from a compilation of published data from literature46, covering porosities of 0.20–0.70 and coordination numbers of 3–14. Extrapolation to the porosity range of 0–0.20 provides coordination numbers in 14-20.

These rock physics models have been widely applied for interpreting Mars’ internal structures50,56,103,104. Potential variations in mineral compositions and temperature-pressure conditions exert only minor influence on the physical properties of rocks (Supplementary Discussions 4 and 5 and Supplementary Figs. 17–19). Therefore, we adopt physical properties of common minerals and rocks from laboratory measurements on Earth as proxies for Martian rocks (Supplementary Table 1).

Lithology of the top layer

The top layer has very low velocities that correspond to the unconsolidated regolith on Mars’ surface. We assume that the top layer consists of weathered basaltic products and approximate the physical properties of Martian basalts by terrestrial basalt analogs (Supplementary Table 3). We then apply the Hertz-Mindlin model for cementless sediments90 to explore the lithological characteristics of this top layer. Only the S-wave velocities from our joint inversion are utilized, as the adopted seismic and seismoacoustic coupling data neither have sufficient sensitivity to constrain the bulk density and Poisson’s ratio27,28,29,47,48. A more reliable independent constraint on bulk density is derived from in-situ surface thermal inertia measurements40, which yields a range of 1098–1360 kg m−3. This bulk density range corresponds to a porosity range of 0.53–0.62 and a coordination number range of 4.3–5.9, using Eqs. (4) and (8), respectively. As for Poisson’s ratio, results from the in-situ HP3 experiment39 obtained a relatively broad range of 0.09–0.42, whereas a laboratory experiment on Martian regolith simulants92,105 reported a narrower range of 0.10–0.15. In this analysis, we adopt a Poisson’s ratio of 0.15, which is also consistent with the expected value for dry, loose regolith. For the calculation of compressional pressure, we initialize the surface pressure to be equivalent to the mean Martian atmospheric pressure (about 0.7 kPa), while compressional pressure versus depth is calculated as the sum of the initial surface pressure and gravity-induced pressure. This gives a compressional pressure range below 50 kPa within the shallow 10 m, consistent with the applicable pressure range for the Hertz-Mindlin model as in the regolith simulant experiment92. In the following, we investigate the frictional contact coefficient f, the porosity, and the asperity parameter root-mean-square height Hrms and microhardness Pmic of the top layer based on the fit to S-wave velocities.

The Poisson’s ratio in the Hertz-Mindlin model only correlates with the Poisson’s ratio of host grain material (0.286 for basalt) and the frictional contact coefficient f for with-friction portion46,92. The Poisson’s ratio of 0.15 thus provides f = 0.42. For a lower Poisson’s ratio of 0.10, f increases to 0.65. These results indicate that a substantial portion of grains exhibit smooth contact without tangential friction.

Direct in-situ measurements constraining the asperity parameters Hrms and Pmic of Martian regolith are currently unavailable. Available laboratory measurements of silica grains106 on Earth show a Pmic value of 8.2 GPa. We adopt this value as a reasonable approximation, given that silica grains have a shear modulus (44 GPa) comparable to the average shear modulus of zero-porosity basalts (40 GPa). Notably, sensitivity analysis reveals that the Pmic value has almost negligible influence on S-wave velocity predictions in our model (Supplementary Fig. 15c). For the root-mean-square height Hrms, we refer to the values (0.6–0.8 µm) determined for the Martian regolith simulants92, considering that the estimated in-situ grain diameters (104–173 µm) from in-situ thermal conductivity40 are comparable to the grain diameter the regolith simulants (220 µm)92.

We further adopt a two-phase grid search to determine the porosity and Pmic in the ranges 0.53–0.62 and 0.01–10 µm, respectively. When assuming a grain diameter of 173 µm, the optimal solution, with a porosity of 0.58 and Hrms of 0.1 µm, demonstrates good agreement with the inverted median S-wave velocity profile (60–275 m/s) in the topmost 9 m (Supplementary Fig. 15a and 15b). These parameters are robust for different values of the asperity microhardness Pmic. We observe that the predicted S-wave velocities reduce by about 10% when the root-mean-square height Hrms increase to 0.2 µm or the grain diameter reduces to 104 µm (Supplementary Fig. 15c), meaning that a rougher contact surface would lower the effective modulus in the Hertz-Mindlin model. Considering the upper and lower velocity bounds leads to slightly different porosity estimations and distinct Hrms values (Supplementary Fig. 15d). Therefore, the lithological parameters obtained to explain the S-wave velocities in the top regolith layer are non-unique. Uncertainties of these parameters should be considered when applying them in further investigations.

We also find that the predicted S-wave velocities within 0.3 m depth are larger than the inverted S-wave velocities and those from the in-situ measurement39, which is a similar phenomenon observed for the regolith simulats92. The gravity-induced pressure at 0.3 m depth is approximately 1.3 kPa, which is only marginally higher than the assumed surface pressure of 0.7 kPa. One plausible interpretation for the higher velocity prediction is that limited atmospheric exchange exists in the topmost 0.3 m depth, thus lowering the effective compressional pressure. Furthermore, soil cohesion forces are inferred to substantially influence the mechanical behavior of high-porosity sand under low-pressure environment40. The very shallow part of regolith layer may deviate from the Hertz-Mindlin contact theory predictions due to cohesion-dominated grain interactions. Other alternative interpretations include instable force chains in low confining pressures107,108 or grains exhibit nonaffine motion108,109 (localized strain heterogeneity), thus causing velocity mispredictions. Additional constraints are needed to explore the contributions of these potential factors on the observed velocity discrepancy.

The landing site was proposed to have a ~ 3-m-thick fine-grained regolith51,53 in consideration of surface weathering for 1.7 Gyr. Underlain materials below 3 m could be a mixture of sand and cobble-size debris/ejecta53. While the Hertz-Mindlin model is based on contacts of granular media, our velocity predictions could reflect the average effect of sand and debris/ejecta. A comparable in-situ observation is Zhurong rover’s radar detection at the southern Utopia Planitia13,14, which resolved a regolith layer of less than 10 m. Notably, freeze-thaw cycles15 have been identified at the Zhurong landing site, which could also contribute to regolith formation, while constraints of such effect are absent at the InSight landing site.

Lithology of the bottom layers

In the bottom layers, the relative low S-wave velocities of TL could be either cemented sediments of basalts or highly porous basalts (Fig. 3, c-d). Geological mapping and crater statistics suggest Hesperian-to-Early-Amazonian basaltic flows underlain by Noachian-to-Early-Hesperian sedimentary materials below 170 m depth53, which is comparable with the stratigraphic sequence of the HML2 and TL in our inversion (Fig. 2a, b). One plausible interpretation suggests that TL may represent substantial sedimentary deposits (extending from 180 to ~800 m depth) during the Noachian epoch when the fluvial activity was widespread on Mars59,63, though potential contributions from impact-fragmented megaregolith cannot be ruled out. In this scenario, the observed positive velocity-depth gradient within this sedimentary layer can be attributed to progressive compaction with depth. The CIL and UCL below ~800 m with higher velocities than HML1 and HML2 could correspond to fractured basalts with less porosities, representing differentiation of Mars’ primordial crustal layers. It should be noted that these interpretations for the bottom layers assume basalt as the host material and neglect mineral cements, representing merely one plausible scenario. A comprehensive analysis of all possible crustal lithology configurations is referred to Knapmeyer-Endrun et al. 110.

Data availability

The InSight’s seismic data are available from NASA’s Planetary Data System74, IPGP’s MSDC75, and the IRIS DMC (https://www.iris.edu/hq/sis/insight). The Mars seismic catalogue is available from InSight Marsquake Service 34. The convective vortex compliance and the compliance of impact-generated infrasound waves are available through the corresponding literatures as well as in Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6. See Supplementary Discussions 1, Supplementary Figs. 2–4, and Supplementary Table 2 for more details about time-frequency analyses for S1222a, inverted subsurface velocities, and lithology results. The datasets generated and analyzed in this study are openly available at Zenodo through https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15574498111.

Code availability

Technical details for all calculations in this study are described in the Methods section, with publicly available codes cited in the reference list. We used version 3.5.0 of the Geopsy package89. Other codes for data analyses and lithology results developed in this study are available at Zenodo through https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15574498111.

References

Ehlmann, B. et al. Subsurface water and clay mineral formation during the early history of Mars. Nature 479, 53–60 (2011).

Kleinböhl, A. et al. Hydrogen escape on Mars dominated by water vapour photolysis above the hygropause. Nat. Astron. 8, 827–837 (2024).

Valantinas, A. et al. Evidence for transient morning water frost deposits on the Tharsis volcanoes of Mars. Nat. Geosci. 17, 608–616 (2024).

Clifford, S. & Parker, T. J. The evolution of the Martian hydrosphere: Implications for the fate of a primordial ocean and the current state of the Northern Plains. Icarus 154, 40–79 (2001).

Carr, M. H. & Head, J. W. III Oceans on Mars: An assessment of the observational evidence and possible fate. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 108, 5042 (2003).

Di Achille, G. & Hynek, B. Ancient ocean on Mars supported by global distribution of deltas and valleys. Nat. Geosci. 3, 459–463 (2010).

Nogoshi, M. & Igarashi, T. On the amplitude characteristics of microtremor, part II. J. Seismol. Soc. Jpn. 24, 26–40 (1971).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Shallow lunar structure determined from the passive seismic experiment. The Moon 13, 57–66 (1975).

Banerdt, W. B. et al. Initial results from the InSight mission on Mars. Nat. Geosci. 13, 183–189 (2020).

Giardini, D. et al. The seismicity of Mars. Nat. Geosci. 13, 205–212 (2020).

Lognonné, P. et al. Constraints on the shallow elastic and anelastic structure of Mars from InSight seismic data. Nat. Geosci. 13, 213–220 (2020).

Lognonné, P. et al. Mars seismology. Annu. Rev. Earth Planetary Sci. 51, 643–670 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Layered subsurface in Utopia Basin of Mars revealed by Zhurong rover radar. Nature 610, 308–312 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Ancient ocean coastal deposits imaged on Mars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA122, e2422213122 (2025).

Zhang, L. et al. Buried palaeo-polygonal terrain detected underneath Utopia Planitia on Mars by the Zhurong radar. Nat. Astron. 8, 69–76 (2024).

Tanaka, K. L. et al. The digital global geologic map of Mars: Chronostratigraphic ages, topographic and crater morphologic characteristics, and updated resurfacing history. Planet. Space Sci. 95, 11–24 (2014).

Golombek, M. et al. Geology and Physical Properties Investigations by the InSight Lander. Space Sci. Rev. 214, 84 (2018).

Golombek, M. et al. Selection of the InSight Landing Site. Space Sci. Rev. 211, 5–95 (2017).

Warner, N. H. et al. Near Surface Stratigraphy and Regolith Production in Southwestern Elysium Planitia, Mars: Implications for Hesperian-Amazonian Terrains and the InSight Lander Mission. Space Sci. Rev. 211, 147–190 (2017).

Pan, L. et al. Crust stratigraphy and heterogeneities of the first kilometers at the dichotomy boundary in western Elysium Planitia and implications for InSight lander. Icarus 338, 113511 (2020).

Kreslavsky, M. A. & Head, J. W. III Kilometer-scale roughness of Mars: Results from MOLA data analysis. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 26695–26711 (2000).

Ivanov, M. A., Hiesinger, H., Erkeling, G. & Reiss, D. Mud volcanism and morphology of impact craters in Utopia Planitia on Mars: Evidence for the ancient ocean. Icarus 228, 121–140 (2014).

Ivanov, M. A. et al. Topography of the Deuteronilus contact on Mars: Evidence for an ancient water/mud ocean and long-wavelength topographic readjustments. Planet. Space Sci. 144, 49–70 (2017).

Grant, J. A. et al. The timing of alluvial activity in Gale crater, Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1142–1148 (2014).

Grant, J. A. & Wilson, S. A. Evidence for late alluvial activity in Gale crater, Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 7287–7294 (2019).

Hobiger, M. et al. The shallow structure of Mars at the InSight landing site from inversion of ambient vibrations. Nat. Commun. 12, 6756 (2021).

Carrasco, S. et al. Empirical H/V spectral ratios at the InSight landing site and implications for the martian subsurface structure. Geophys. J. Int. 232, 1293–1310 (2023).

Xu, Z. et al. Modeling seismic recordings of high-frequency guided infrasound on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 127, e2022JE007483 (2022).

Onodera, K. et al. Description of Martian convective vortices observed by InSight and implications for vertical vortex structure and subsurface physical properties. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 128, e2023JE007896 (2023).

Carrasco, S. et al. Constraints for the Martian crustal structure from Rayleigh waves ellipticity of large seismic events. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104816 (2023).

Drilleau, M. et al. Constraints on lateral variations of Martian crustal thickness from seismological and gravity field measurements. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL105701 (2024).

Joshi, R. et al. Joint inversion of receiver functions and apparent incidence angles to determine the crustal structure of Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL100469 (2023).

Kawamura, T. et al. S1222-The largest marsquake detected by InSight. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL101543 (2022).

InSight Marsquake Service. Mars seismic catalogue, InSight mission; V14 2023/04/01. ETHZ, IPGP, JPL, ICL, ISAE-Supaero, MPS, Univ. Bristol. https://doi.org/10.12686/a21 (2023).

Nakamura, Y. A method for dynamic characteristics estimation of subsurface using microtremor on the ground surface. RTRI Quart. Rep. 30, 25–33 (1989).

Xiao, W. & Wang, Y. Characteristics of horizontal to vertical spectral ratio of InSight seismic data from Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 127, e2020JE006813 (2022).

Sorrells, G. G. A preliminary investigation into the relationship between long-period seismic noise and local fluctuations in the atmospheric pressure field. Geophys. J. Int. 26, 71–82 (1971).

Sorrells, G. G. et al. Earth Motion caused by local atmospheric pressure changes. Geophys. J. Int. 26, 83–98 (1971).

Brinkman, N. et al. In situ regolith seismic velocity measurement at the InSight landing site on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 127, e2022JE007229 (2022).

Grott, M. et al. Thermal conductivity of the martian soil at the Insight landing site from HP3 active heating experiments. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 126, e2021JE006861 (2021).

Shi, J. et al. High-frequency receiver functions with event S1222a reveal a discontinuity in the Martian shallow crust. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL101627 (2022).

Sambridge, M. Geophysical inversion with a neighbourhood algorithm—i. searching a parameter space. Geophys. J. Int. 138, 479–494 (1999).

Wathelet, M. An improved neighborhood algorithm: parameter conditions and dynamic scaling. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L09301 (2008).

Morgan, P. et al. A pre-landing assessment of regolith properties at the InSight landing site. Space Sci. Rev. 214, 104 (2018).

Carrasco, S. Multi-scale investigation of the subsurface structure at the InSight landing site, on Mars, using single-station seismology (Doctoral dissertation). University of Cologne, https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/73169 (2024).

Mavko, G., Mukerji, T. & Dvorkin, J. In The Rock Physics Handbook (3rd edition). (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Froment, M. et al. Inferring the speed of sound and wind in the nighttime Martian boundary layer from impact-generated infrasound. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL109726 (2024).

Kenda, B. et al. Subsurface structure at the InSight landing site from compliance measurements by seismic and meteorological experiments. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 125, e2020JE006387 (2020).

Adam, L. & Otheim, T. Elastic laboratory measurements and modeling of saturated basalts. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 118, 840–851 (2013).

Manga, M. & Wright, V. No cryosphere-confined aquifer below InSight on Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093127 (2021).

Golombek, M. et al. Geology of the InSight landing site on Mars. Nat. Commun. 11, 1014 (2020).

Sweeney, J. et al. Degradation of 100m-scale rocky ejecta craters at the InSight landing site on Mars and implications for surface processes and erosion rates in the Hesperian and Amazonian. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 123, 2732–2759 (2018).

Warner, N. H. et al. In situ and orbital stratigraphic characterization of the InSight landing site—A type example of a regolith-covered lava plain on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 127, e2022JE007232 (2022).

Warren, P. H. & Rasmussen, K. L. Megaregolith insulation, internal temperatures, and bulk uranium content of the moon. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 92, 3453–3465 (1987).

Hanna, J. C. & Phillips, R. J. Hydrological modeling of the Martian crust with application to the pressurization of aquifers. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 110, E01004 (2005).

Wright, V., Dasent, J., Kilburn, R. & Manga, M. A minimally cemented shallow crust beneath InSight. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099250 (2022).

Hartmann, W. K., Anguita, J., de la Casa, M. A., Berman, D. C. & Ryan, E. V. Martian cratering 7: The role of impact gardening. Icarus 149, 37–53 (2001).

Sun, V. Z. & Milliken, R. E. Ancient and recent clay formation on Mars as revealed from a global survey of hydrous minerals in crater central peaks. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 120, 2293–2332 (2015).

Pan, L., Ehlmann, B. L., Carter, J. & Ernst, C. M. The stratigraphy and history of Mars’ northern lowlands through mineralogy of impact craters: A comprehensive survey. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 122, 1824–1854 (2017).

Carter, J., Poulet, F., Bibring, J.-P., Mangold, N. & Mruchie, S. Hydrous minerals on Mars as seen by the CRISM and OMEGA imaging spectrometers: Updated global view. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 118, 831–858 (2013).

Bramble, M. S. & Hand, K. P. Spectral evidence for irradiated halite on Mars. Sci. Rep. 14, 5503 (2024).

Thomas, N. H. et al. Mars Science Laboratory observations of chloride salts in Gale crater, Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 10754–10763 (2019).

Carter, J., Poulet, F., Bibring, J.-P. & Murchie, S. Detection of hydrated silicates in crustal outcrops in the Northern plains of Mars. Science 328, 1682–1686 (2010).

Hughes, C. M., Cardenas, B. T., Goudge & Mohrig, D. Deltaic deposits indicative of a paleo-coastline at Aeolis Dorsa, Mars. Icarus 317, 442–453 (2019).

Cardenas, B. T., Mohrig, D. & Goudge, T. A. Fluvial stratigraphy of valley fills at Aeolis Dorsa, Mars: Evidence for base-level fluctuations controlled by a downstream water body. GSA 130, 484–498 (2017).

Cardenas, B. T. & Lamb, M. P. Paleogeographic reconstructions of an ocean margin on Mars based on deltaic sedimentology at Aeolis Dorsa. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 127, e2022JE007390 (2022).

Parker, T. J., Gorsline, D. S., Saunders, R. S., Pieri, D. C. & Schneeberger, D. M. Coastal geomorphology of the Martian northern plains. J. Geophys. Res. 98, 11061–11078 (1993).

Ehlmann, B. L. & Edward, C. S. Mineralogy of the Martian surface. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 42, 291–315 (2014).

Lefort, A., Burr, D. M., Beyer, R. A. & Howard, A. D. Inverted fluvial features in the Aeolis-Zephyria Plana, western Medusae Fossae Formation, Mars: Evidence for post-formation modification. J. Geophys. Res. 117, E03007 (2012).

Grotzinger, J. P. et al. Deposition, exhumation, and paleoclimate of an ancient lake deposit, Gale crater, Mars. Science 350, aac7575 (2015).

Morgan, A. M. et al. Sedimentology and climatic environment of alluvial fans in the martian Saheki crater and a comparison with terrestrial fans in the Atacama Desert. Icarus 229, 131–156 (2014).

Leask, E. K. & Ehlmann, B. L. Evidence for deposition of chloride on Mars from small-volume surface water events into the Late Hesperian-Early Amazonian. AGU Adv. 3, e2021AV000534 (2022).

Laskar, J. et al. Long term evolution and chaotic diffusion of the insolation quantities of Mars. Icarus 170, 343–364 (2004).

InSight Mars SEIS Data Service. Data service, InSight SEIS data Bundle. PDS Geosciences (GEO) Node. https://doi.org/10.17189/1517570 (2019).

InSight Mars SEIS Data Service. SEIS raw data, Insight Mission. IPGP, JPL, CNES, ETHZ, ICL, MPS, ISAE-Supaero, LPG, MFSC. https://doi.org/10.18715/SEIS.INSIGHT.XB_2016 (2019).

Compaire, N. et al. Autocorrelation of the ground vibrations recorded by the SEIS InSight seismometer on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 126, e2020JE006498 (2021).

Welch, P. D. The use of fast Fourier transforms for the estimation of power spectra: A method based on time averaging over short modified periodograms. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust 15, 70–73 (1967).

Horvath, P., Latham, G. V., Nakamura, Y. & Dorman, H. J. Lunar near-surface shear wave velocities at the Apollo landing sites as inferred from spectral amplitude ratios. J. Geophys. Res. 85, 6572–6578 (1980).

Sánchez-Sesma, F. J. et al. A theory for microtremor H/V spectral ratio: application for a layered medium. Geophys. J. Int. 186, 221–225 (2011).

Weaver, R. On diffuse waves in solid media. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 71, 1608–1609 (1982).

Margerin, L. Generalized eigenfunctions of layered elastic media and application to diffuse fields. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 164–174 (2009).

Margerin, L., Campillo, M., Van Tiggelen, B. & Hennino, R. Energy partition of seismic coda waves in layered media: Theory and application to pinyon flats observatory. Geophys. J. Int. 177, 571–585 (2009).

Menina, S. et al. Energy envelope and attenuation characteristics of High-Frequency (HF) and Very-High-Frequency (VF) Martian events. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 111, 3016–3034 (2021).

Tanimoto, T. & Wang, J. Theory for deriving shallow elasticity structure from colocated seismic and pressure data. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 124, 5811–5835 (2019).

Xu, Z. & Lognonné, P. A comprehensive theory for 1-D (an)elastic medium deformation due to plane-wave fluid pressure perturbation. Geophys. J. Int. 236, 1499–1512 (2024).

Crawford, W. C., Webb, S. C. & Hildebrand, J. A. Seafloor compliance observed by long-period pressure and displacement measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 96, 16151–16160 (1991).

Voronoi, G. Nouvelles applications des paramètres continus à la théorie des formes quadratiques. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik (Crelles Journal) 134, 97–102 (1908).

Gelfand, A. E. & Smith, A. F. M. Sampling based approaches to calculating marginal densities. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 85, 398–409 (1990).

Wathelet, M. et al. Geopsy: A user-friendly open-source tool set for ambient vibration processing. Seismol. Res. Lett. 91, 1878–1889 (2020).

Mindlin, R. D. Compliance of elastic bodies in contact. J. Appl. Mech. 16, 259–268 (1949).

Bahrami, M., Yovanovich, M. M. & Culham, J. R. A compact model for spherical rough contacts. J. Tribol. 127, 884–889 (2005).

Caicedo, B., Betancourt, J. P. C., Delage, P., Lognonné, P. & Banerdt, B. Wave velocities and Poisson ratio in a loose sandy Martian regolith simulant under low stresses: 2. Theoretical analysis. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 128, e2023JE008008 (2023).

Dvorkin, J. & Nur, A. Elasticity of high-porosity sandstones: Theory for two North Sea data sets. Geophysics 61, 1363–1370 (1996).

Berryman, J. G. Long-wavelength propagation in composite elastic media I. Spherical inclusions. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 68, 1809–1819 (1980a).

Berryman, J. G. Long-wavelength propagation in composite elastic media II. Ellipsoidal inclusions. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 68, 1820–1831 (1980b).

Norris, A. N. A differential scheme for the effective moduli of composites. Mech. Mater. 4, 1–16 (1984).

Berryman, J. G. Single-scattering approximations for coefficients in Biot’s equations of poroelasticity. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 91, 551–571 (1992).

David, E. C. & Zimmerman, R. W. Pore structure model for elastic wave velocities in fluid-saturated sandstones. J. Geophys. Res. 117, B07210 (2012).

Gassmann, F. Über die Elastizität poroser Medien. Veirteljahrsschrift der Naturforschen den Gesellschaft in Zürich 96, 1–23 (1951).

Athy, L. F. D. ensity porosity, and compaction of sedimentary rocks. AAPG Bull 14, 1–24 (1930).

Clifford, S. M. A model for the hydrologic and climatic behavior of water on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 98, 10973–11016 (1993).

Murphy, W. F. Effects of microstructure and pore fluids on granular sedimentary materials (Doctoral dissertation). (Stanford: Stanford University, 1982).

Kilburn, R., Dasent, J., Wright, V. & Manga, M. Lithology, pore-filling media, and pore closure depth beneath InSight on Mars inferred from shear wave velocities. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 127, e2022JE007539 (2022).

Dai, M. & Sun, D. Martian crustal model from a joint inversion of receiver functions and apparent shear wave velocity. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 128, e2022JE007702 (2023).

Betancourt, J. P. C., Delage, P., Caicedo, B., Lognonné, P. & Banerdt, B. Wave velocities and Poisson ratio in a loose sandy Martian regolith simulant under low stresses: 1. Laboratory investigation. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 128, e2023JE007988 (2023).

Yovanovich, M. Micro and macro hardness measurements, correlations, and contact models. In 44th AIAA aerospace sciences meeting and exhibit, no. 979 http://www.mhtl.uwaterloo.ca/pdf_papers/mhtl06-2.pdf (2006).

Li, W. & Juanes, R. Dynamic imaging of force chains in 3D granular media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 121, e2319160121 (2024).

Makse, H. A., Gland, N., Johnson, D. L. & Schwartz, L. Granular packings: Nonlinear elasticity, sound propagation, and collective relaxation dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 70, 061302 (2004).

Johnson, D. L., Makse, H. A., Gland & Schwartz, L. Nonlinear elasticity of granular media. Physica B: Condensed Matter 279, 134–138 (2000).

Knapmeyer-Endrun, B. et al. Porosity and hydrous alteration of the Martian crust from InSight seismic data. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter., 107383 (2025).

Xiao, W. Data and code repository for “Subsurface fluvial sediments beneath InSight on Mars from geophysical constraints”. Version V1. Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15574499 (2025).

Smith, D. et al. Mars Global Surveyor Laser Altimeter mission experiment gridded data record. NASA Planetary Data System, MGS-M-MOLA-5-MEGDR-L3-V1.0 (2003).

Perrin, C. et al. Geometry and segmentation of Cerberus Fossae, Mars: Implications for marsquake properties. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 127, e2021JE007118 (2022).

Andrews-Hanna, J., Zuber, M. & Banerdt, W. The Borealis basin and the origin of the martian crustal dichotomy. Nature 453, 1212–1215 (2008).

Tanaka, K. L. et al. Geologic Map of Mars, Scale 1:20,000,000. U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map SIM 3292 (2014).

Acknowledgements