Abstract

The 1458/59 CE volcanic event, among the largest in the last millennium, is primarily attributed to the Kuwae volcano in Vanuatu. However, a recent study suggests the Reclus volcano in southern Patagonia, Chile, as an alternative source. Here, we assess the hypothesis by examining unpolished, micron-sized glass shards from the 1458/59 CE cryptotephra in the Antarctic Vostok Station firn core. Results reveal a bimodal composition of dacitic and rhyolitic shards, linked to Kuwae and Reclus, respectively. Antarctic ice core records also exhibit a two-stage pattern of ash deposition: coarse ash from nearby volcanoes followed by finer ash transported over long distances, implying concurrent eruptions. Nevertheless, discrepancies in composition between observed rhyolitic shards and existing Reclus data, combined with no recorded Reclus activity in the 1450 s, suggests the possibility of an undocumented extratropical rhyolitic source. This study underscores the value of glass shard analysis in identifying the origins of volcanic eruptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large volcanic eruptions inject large amounts of sulfur-rich gases, mainly sulfur dioxide (SO2), into the stratosphere, which are converted to sulfate aerosols (H2SO4) by oxidation, eventually causing an interannual to decadal cooling effect on the hemispheric and global climate by reducing incoming solar radiation1,2,3,4. Several studies have attempted to understand the climate response to stratospheric volcanic eruptions by reconstructing comprehensive records of large volcanic eruptions and the associated short-term climate variability using high-resolution analyses of bipolar volcanic sulfate signals simultaneously recorded in Greenland and Antarctic ice cores5,6,7,8,9. Despite these advances, exact dating and source identification of each volcanic event are essential because estimates of the volcanic-induced cooling effect can vary according to various factors, such as the timing and location of the eruption10,11,12.

The 1450s was one of the coldest decades in the Northern Hemisphere during the Common Era (CE), likely due to the cooling effect induced by a large explosive volcanic eruption during the corresponding period7,13,14. This volcanic event was initially considered to be associated with a large stratospheric eruption of the submarine caldera of Kuwae, Vanuatu (16.83 °S, 168.54 °E) at 1452/53 CE, based on matching bipolar volcanic acidity and sulfate peaks that were dated to 1452/53 CE in an array of Greenland and Antarctic ice cores15. However, subsequent studies utilizing well-constrained chronologies and highly resolved volcanic sulfate records from multiple Greenland and Antarctic ice cores have revised the date of the Kuwae eruption signal from 1452/53 CE to 1458/59 CE5,6,7,16,17.

Despite these promising results, there are still remaining questions regarding the precise dating and validation of Kuwae eruption signals derived from ice core records. These uncertainties arise primarily from the fact that Greenland ice core records display two prominent sulfate peaks in the 1450s, with a relatively small volcanic signal at 1452/53 CE and a larger peak at 1458/59 CE15,18. In contrast, the Antarctic ice core records show only one dominant sulfate peak during the corresponding period5,15,16. Tree-ring-based reconstructions of Northern Hemisphere summer temperatures revealed a strong cooling event in 1453 CE, suggesting an association between the corresponding climatic anomaly and a mid-fifteenth-century volcanic eruption19,20,21,22. However, according to sulfur isotopic signatures from the Greenland and Antarctic ice cores, the 1452/53 CE and 1458/59 CE volcanic signals were attributed to a Northern Hemisphere extratropical eruption and a large tropical eruption in the Southern Hemisphere, respectively9, confirming a large stratospheric sulfate injection in 1458/59 CE, which may have originated from the Kuwae eruption23.

Hartman et al24 examined the geochemical properties of glass shards from a cryptotephra sampled from the South Pole Ice Core (SPC14) at 1458/59 CE. They found rhyolitic glass particles of a diameter of up to 50 μm that differed markedly from the dacitic compositions of the Kuwae eruption25,26,27, but closely matched those of the Reclus eruption (50.96 °S, 73.59 °W), a volcano located in the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, Chile28,29,30. Consequently, ref. 24 proposed the Reclus volcano as the candidate source volcano for the 1458/59 CE large sulfate signal in Antarctic ice cores, resulting from the advection of volcanic plumes from the eruption of the Reclus volcano over Antarctica via the troposphere. The suggested tropospheric pathway contrasts with the extensive and enduring deposition of volcanic sulfate6,7 and sulfur isotopic signatures that constrained the 1458/59 CE stratospheric volcanic event9,23. As a result, the precise source volcano responsible for the 1458/59 CE bipolar sulfate anomaly remains uncertain.

The traditional method for source discrimination of volcanic glass shards trapped in ice relies on geochemical characterization using electron probe X-ray microanalysis with wavelength dispersive spectrometry (EPMA–WDS) and scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (SEM–EDX)31,32,33. These techniques, however, face challenges in accurately identifying the potential source of non-visible volcanic ash, also known as cryptotephra (typically less than 125 μm in diameter), in the ice-core layers because of the difficulties in obtaining robust composition data for fine particles with conventional analytical methods. For example, EPMA–WDS provides accurate and precise geochemical quantification; however, it is challenging to determine the abundance of elements in small particles because of beam size constraints (typically ~5–20 μm in routine practice). In contrast, SEM–EDX analysis can determine the geochemical composition of small particles using a sub-micrometer probe diameter (≤1 μm), but offers less precise compositional quantification owing to matrix and geometric effects. Both methods also require completely flat, polished glass shards for effective geochemical quantification33,34, which is labor-intensive and challenging for sparse and fine-grained cryptotephra samples. To address these issues, previous studies have developed optimal protocols such as EPMA–WDS methods for measuring a beam size as small as 3 μm35 and for determining the beam overlap integral when the beam size from 3 to 20 μm is larger than those in the polished glass areas, exhibiting beams partially overlapping onto the mounting substrates31,33. In addition, a method involving the light polishing procedure (<5 min) using 0.25–1 μm grades has been developed for the mounting and analysis of small glass shards33,36,37. However, when polished glass shards are insufficient in population, irregular in shape, or very small in size, these optimized analytical approaches become impractical. In such cases, SEM–EDX analysis of unpolished shards is the final available option; however, there are still challenges related to the accuracy and precision of compositional quantification.

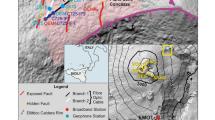

In this study, we analyzed the geochemical composition of unpolished, micron-sized volcanic glass shards extracted from a shallow firn core (referred to as the VK22 core) drilled near Russia’s Vostok Station in East Antarctica (Fig. 1), using a quantitative SEM–EDX technique. This was performed using a reverse Monte Carlo simulation combined with a robust successive approximation algorithm, which can adequately account for the matrix and geometric effects, contributing to an accurate determination of the characteristic X-ray intensities of specific elements in unpolished glass shards. This method allowed for the quantitative determination of cryptotephra’s geochemical composition, enabling us to identify potential source volcanoes for the 1458/59 CE eruption through comparison with known volcanic products.

Also shown are the locations of the VK22 (Vostok; black circle), SPC14 (South Pole; blue circle), and WDC06A (WAIS Divide; purple circle) ice core sites mentioned in the text. Basemap from Google Earth Pro (version 7.3.6). Map data: © 2024 Google; Data SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO; imagery: Landsat/Copernicus, US Geological Survey, PGC/NASA. Modified and annotated by the authors.

Results and discussion

Geochemical properties of glass shards from the 1458/59 CE cryptotephra

Table 1 summarizes the geochemical characteristics of the 14 volcanic glass shards extracted from the 1458/59 CE cryptotephra layer. The data for all measured shards are presented in Supplementary Data 1. Individual glass particles showed a typical range of volcanic ash shapes (platy, cuspate, and fluted)30,32 with very small sizes of less than 11 μm (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The compositions of all glass shard particles in the sample were characterized by a wide range of mean values in the oxide percentages of eight major elements (SiO2, TiO2, Al2O3, FeO, MgO, CaO, Na2O, and K2O), showing a bimodal distribution in composition from dacite to rhyolite (Table 1, Fig. 2, and Supplementary Data 1). Eight shard particles with a mean diameter of 4.0 ± 1.0 μm were in the dacite composition range, whereas the remaining six shards with a mean diameter of 4.8 ± 3.0 μm have a rhyolitic composition. Variations in individual glass compositions were observed for elements with low concentrations (e.g., TiO2, FeO, MgO, and CaO; see Supplementary Data 1). These variations are likely partially attributable to the intrinsic analytical limitations of SEM–EDX and the unpolished surface of the glass shards, thus underscoring the importance of careful interpretation. Nevertheless, the rhyolitic shards closely overlap with the previously reported compositions of the 1458/59 CE cryptotephra in the SPC14 core24, with statistical distance (D2)38,39 and similarity coefficient (SC)40 values of 6.28 and 0.93, respectively, which are indicative of a corresponding source (e.g., Reclus; see Table 1, Fig. 2, and Methods). This statistical similarity between the glass compositions of the SPC14 core (EPMA analysis of polished shards24) and the VK22 (Monte Carlo simulation-based SEM–EDX of unpolished shards) validates our analytical method (see Methods).

All compositions (SiO2, TiO2, Al2O3, FeO, MgO, CaO, Na2O, and K2O) were normalized to a sum of 100 wt%. Error bars represent the range within ±1 standard deviation (SD) of the mean obtained from repeat measurements of reference materials. The geochemical data used here are listed in Supplementary Data 1, 2.

Potential (near-)simultaneous eruptions of Kuwae and an extratropical volcano in 1458/59 CE

The bimodal geochemical signatures of glass shards observed in the VK22 1458/59 CE cryptotephra can be attributed to one of two possible scenarios: (1) compositional variation from dacite to rhyolite during a single eruption41 and (2) (near-)simultaneous effects of the two types of volcanic eruptions in different places, including Kuwae and Reclus. Considering the dating uncertainties for the eruption, these possibilities were assessed by comparing the glass geochemical characteristics of the 1458/59 CE VK22 cryptotephra with those from Kuwae, Reclus, and 18 different volcanic eruptions in the tropics (30 °N–30 °S) and the Southern Hemisphere extratropics (30 °S–90 °S) during the 1450s, which were drawn from the catalog of volcanic eruptions of the Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program (https://volcano.si.edu) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). The geochemical compositions of the volcanic glasses are available in the literature for 18 of the 23 recorded eruptions, allowing a comparison of only these datasets with the present data. When comparing these datasets, it was assumed that no other volcanism occurred during the 1450s, apart from those of Kuwae, Reclus, and 18 different volcanoes, and that the geochemical properties of glass shards from the cryptotephra layer in the ice provide reliable evidence of volcanic provenance.

As shown in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2, individual volcanoes that could be related to the VK22 1458/59 CE cryptotephra had distinctive geochemical characteristics of glass shards, constraining the specific source of the cryptotephra deposits. Geochemical comparisons indicated that no single volcano could account for the broad compositional range observed, thereby ruling out the first possibility. The dacitic composition of glass shards in the VK22 1458/59 CE cryptotephra is comparable to the Kuwae and Rabaul (4.27 °S, 152.20 °E, Papua New Guinea; eruption at 1450 ± 150 CE; unknown Volcanic Explosivity Index, VEI; see Supplementary Data 2) fields, with the statistical significances of the respective D2 values of 1.09 and 2.41 and the respective SCs of 0.96 and 0.93 (Table 1). The rhyolitic compositions are close to the compositional fields of Reclus, Mount Pelée (14.82 °N, 61.17 °W, the French Caribbean Island of Martinique; eruption at 1460 ± 20 CE; unknown VEI), and Pinatubo (15.14 °N, 120.35 °E, Philippines; eruption at 1450 ± 50 CE; VEI 5; see Supplementary Data 2), with the respective D2 values of 17.3, 6.70, and 2.70 and the respective SCs of 0.85, 0.87, and 0.90 (Table 1).

Despite the similarities in geochemical signatures and eruption chronologies, the magnitude and associated plume height of candidate volcanoes are crucial parameters for assessing the potential of volcanic ash to reach Antarctica and, consequently, to validate the source volcanoes42,43. However, as detailed information on past eruption magnitudes remains limited (see above), we examined the geographical and volcanological features of individual volcanoes. For example, although Kuwae and Rabaul are both located in the tropics, Kuwae is classified as a stratovolcano, which typically ejects substantial quantities of sulfate and ash into the stratosphere26. In contrast, Rabaul is a shield volcano, characterized by small- to moderate-sized ignimbrite-forming eruptions, whose ejecta dispersal is mostly confined to local areas44. This suggests that Kuwae was the most likely source of the dacitic shards identified in the sample. Reclus, Pelée, and Pinatubo are all stratovolcanoes45 and can also be potential sources of shards with uniform rhyolitic compositions. Although Reclus is located in the Southern Hemisphere extratropics, the other two volcanoes are located in the tropics. Given the presence of large rhyolitic shard particles (up to 50 micrometers) in the SPC14 1458/59 CE cryptotephra sample24 and the slightly larger size of rhyolite compared to dacitic shards in this study (as shown in Table 1), it seems improbable that the source is a distant volcano. This observation aligns with the hypothesis of a southern high-latitude origin, and among the known candidates, Reclus has been put forth24. Despite that, no known eruptions from Reclus have been documented in the 1450s28,29,30,46, and the VK22 and SPC14 rhyolitic glasses show compositional differences from published Reclus glass (e.g., ~3 wt% lower SiO2 and higher FeO and MgO), making a unique connection less likely. This raises the possibility that the rhyolitic shards originated from a different, yet undocumented, source in high-latitude Southern Hemisphere regions such as (sub-) Antarctica, South America, southern Africa, and New Zealand. As of now, the existing data do not suffice to conclusively assign the rhyolitic component to a specific volcano (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Consequently, further investigations are required to substantiate this hypothesis.

Compared to the wide range of sizes (~5 to 50 μm) of rhyolitic glass particles in the SPC14 core, the rhyolitic glass shards from the VK22 core sample were smaller than 11 μm (Table 1). The variation in size between the two sites may be attributed to differing atmospheric transport efficiencies for tephra particles originating from a southern high-latitude source region, as these particles traverse to their respective destinations. This is evidenced by the size distribution of dust in different areas of East Antarctica, which shows that a larger proportion of the coarser dust fractions is related to atmospheric pathways subjected to short and relatively low-altitude trajectories in the mid-troposphere47,48. For example, trajectory modeling showed that dust originating from Patagonia, southernmost South America, appears to be transported more quickly and effectively to the South Pole than to Vostok49, supporting the above speculation.

Overall, the bimodal composition of glass shards observed in the VK22 1458/50 CE cryptotephra most likely arises from the (near-)simultaneous deposition of cryptotephras originating from both the Kuwae and a southern high-latitude eruption, which are geochemically distinguishable from each other.

Antarctic ice core perspectives on (near-)simultaneous Kuwae and extratropical volcanic eruptions

SO2 injected into the stratosphere after large volcanic eruptions from high to low latitudes in both hemispheres can persist for several years, inducing a global distribution of sulfate aerosols and resulting in the presence of distinct sulfate peaks lasting a few years in both Greenland and Antarctic ice cores5,7,23,50. However, the volcanic ash released into the troposphere is transported quickly by wind to distant locations away from the volcano and tends to be smaller in size as the distance from the volcano increases51. This ultimately results in tephra layers appearing in the ice prior to the major sulfate peak24,52,53, with relatively larger particles from eruptions at high latitudes than at mid- and low latitudes53,54. Consequently, the depositional sequence of volcanic ash and sulfate in ice cores, combined with the particle size distributions of cryptotephras, has the potential to constrain the source parameters of past volcanic eruptions, including their source locations and transport mechanisms53,54,55. Note that such detailed investigations necessitate high-resolution ice-core records because lower sampling resolutions can smooth out information about depositional sequence.

Koffman et al.53 used this approach to provide potential insights into the relative locations of known and unknown volcanic events, including the 1458/59 CE eruption recorded in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) Divide Deep Core WDC06A, using electrolytic conductivity (a substitute proxy for sulfate concentration) and particle concentration profiles. That study referred to the 1458/59 CE event as a single eruption of the Kuwae volcano and used the particle size distribution determined by calculating the total volume of insoluble particles in 31 size bins ranging in diameter from 1.0 to 15 μm. However, the volume-based particle size mode (PSM), defined as the most commonly occurring size, in ice at the WAIS Divide site, can be strongly influenced by large dust particles derived from local dust sources when the PSM is used for size distributions56. Moreover, the PSM records in the SPC14 ice core are available for the size range from 2.0 to 6.4 μm57. Therefore, this study used the PSM of 2.0–6.4-μm diameter to characterize the fine volcanic ash deposition patterns, as shown in Fig. 3.

The particle mode size and concentration lines represent the 51 and 7-point running averages for the WDC06A and SPC14, respectively, resulting in approximately seasonal time resolution records. Magenta and green shaded areas show the time intervals of particle peak concentrations with increased particle mode size and post-particle peak concentrations with decreased particle mode size, respectively, during the 1458/59 CE volcanic eruption period. Blue shaded areas show the occurrence of peak concentrations of particles at each site, following massive volcanic eruptions of Tambora, Huaynaputina, and Samalas. More details of the WDC06A and SPC14 cores are shown in Fig. 1.

Based on the above features, the 1458/59 CE geochemical signatures in the VK22 core were further tested to determine whether they represent concurrent cryptotephras from (near-)simultaneous eruptions of the Kuwae and extratropical volcanoes. This study examined high-resolution records of sulfur/sulfate, particle concentrations, and PSM exclusively available from the WDC06A and SPC14 cores among the existing Antarctic ice core records, spanning the specific periods of 1455–1465, 1810–1820, 1595–1605, and 1255–1265 CE. The selected times were associated with known volcanic eruptions in 1458/59 CE (marked as an unknown location), 1815 CE (Tambora, Indonesia), 1600 CE (Huaynaputina, Peru), and 1257 CE (Samalas, Indonesia) (see Fig. 3). These volcanic events were chosen because the latter three volcanoes are located in the tropics of the Southern Hemisphere, which may provide another approach for evaluating the concurrent presence of geochemically different tephra glasses from the contemporaneous but separate eruptions observed in the VK22 1458/59 CE cryptotephra layer.

The four different temporal sequences of individual volcanic events exhibited distinct particle concentration peaks preceding the maxima of the sulfate peaks by several months or even a year (Fig. 3), which could be explained by the consistent pattern of the initial tropospheric intrusion of volcanic particles, followed by the subsequent transport of stratospheric sulfate aerosols over Antarctica. Interestingly, the PSM decreased in parallel with particle concentration peak in the tephra layers from the eruptions of Tambora (~3.5 μm in both WDC06A and SPC14), Huaynaputina (~5 μm in SPC14), and Samalas (~4 and ~2.5 μm in the WDC06A and SPC14 cores, respectively) (blue shaded boxes in Fig. 3). This feature reflects the higher proportions of very fine volcanic ash in these layers, likely due to the lower removal efficiency in the atmosphere, resulting in longer lifetimes for ashes that have undergone long-range transport following such tropical volcanic eruptions53,58. Compared to the shifts in the PSMs associated with known tropical volcanic eruptions, an increase in the PSM is seen in the 1458/59 CE layers (~4.5 μm in both WDC06A and SPC14) when the particle concentrations peaked (magenta shaded box in Fig. 3). Subsequently, the PSM decreased to ~3.5 μm (WDC06A) and ~3 μm (SPC14) within the layers where the particle concentration levels exceeded the background concentrations (green shaded box in Fig. 3). The characteristic pattern of changing PSM identified in the WDC06A and SPC14 1458/59 CE records may be related to the initial transport of relatively coarse volcanic ash from a source closer to Antarctica and subsequent deposition of long-distance transported finer ash particles from the remote volcano (i.e., Kuwae). This supports two (near-)simultaneous eruptions of the Kuwae and extratropical volcanoes in 1458/59 CE, as indicated by the bimodal composition of glass shards in the VK22 1458/59 CE cryptotephra (Fig. 2).

Conclusions

In this study, geochemical properties of the glass shards in the VK22 1458/59 CE cryptotephra were used to constrain the source volcano related to a bipolar ice core record of very large eruptions during the corresponding period. The newly obtained glass shard compositions contained a wide range of major oxides. They are bimodal, showing two distinct compositional ranges between dacite and rhyolite. Comparing the data with those compiled for Kuwae, Reclus, and 18 known explosive eruptions in the 1450s, the observed bimodal composition of glass shards indicates that cryptotephra deposits may have been differentially transported from the (near-)simultaneous eruptions of tropical Kuwae (the most likely source for dacitic shards) and Southern Hemisphere extratropical (for rhyolitic shards) volcanoes. Even though Reclus has been proposed as a potential source of the rhyolitic shards, the lack of documented Reclus activity in the 1450s and the compositional offsets from published Reclus glass collectively suggest a greater probability of an alternative, yet undocumented, extratropical source, necessitating further exploration. According to the reference sequences of volcanic ash and sulfate deposition from the Antarctic ice core records of four well-known stratospheric eruptions, a characteristic pattern of changing PSM in the 1458/59 CE event reveals the initial transport of relatively coarse volcanic ash from a nearby source and the subsequent deposition of finer ash particles transported long distances from a remote source. This provides constraints on (near-)simultaneous eruptions of candidate volcanoes.

Methods

Ice-core drilling and processing

In December 2021, a 30.18-m-deep VK22 firn core, ~7.5 cm in diameter, was drilled near the Russian inland Vostok Station in Central Antarctica (78.47 °S, 106.84 °E, 3,490 m above sea level; Fig. 1) using a light mechanical auger59, as part of the consortium project between the Republic of Korea and Russia. After drilling, electrical conductivity measurements (ECM) of the entire VK22 core were performed in the glaciological laboratory of the Vostok station at −15 °C ± 4 °C using a 1000 V DC input signal. The output signals were recorded digitally at one-second intervals, which have a resolution of ~1.4 cm from discrete samples that correspond to 2–5 data points per year according to the core density60. Subsequently, 40 sections, 39–65 cm in length, were cut longitudinally into two halves and frozen in polyethylene bags. One-half was transported to the Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI) in the Republic of Korea and stored in a cold room at –15 °C before analysis. It should be noted that the melting of core sections between depths of 9.94 and 17.96 m occurred during transportation, resulting in substantial damage to the segments that were excluded from analysis.

Each core section at depths between 17.96 and 30.18 m was mechanically decontaminated using a cylindrical homemade Teflon tumbler and ultraclean procedures at KOPRI, as described elsewhere61. These procedures involved chiseling successive veneers of ice in progression from the contaminated outside to the central part of each section using ultraclean ceramic knives (Models: FK075WH, Kyocera Advanced Ceramics, Kyoto, Japan). All the equipment used in the decontamination process was acid-cleaned extensively prior to use, and chiseling was performed inside a class 10 vertical laminar flow clean bench installed inside a cold room at –15 °C. The innermost parts of each section obtained were then divided into two to three pieces, each 6.0 to 12.5 cm long, which were recovered directly into ultraclean 1 L wide-mouth low-density polyethylene (LDPE) bottles (Nalgene, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wiesbaden, Germany). The inner core samples were melted at room temperature, aliquoted, and frozen until analysis.

Major ion measurements

The aliquots of the VK22 firn core samples between 17.96 and 30.18 m were melted at room temperature. Ionic species (Na+ and SO42−) were determined using Dionex (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) ICS-2100 and ICS-5000 with an IonPac CS12A (2 × 250 mm) analytical column, methanesulfonic acid eluent, and a CSRS-300 suppressor for Na+ and Dionex ICS-2000 and ICS-5000 equipped with an IonPac AS15 (2 × 250 mm) analytical column, potassium hydroxide eluent, and an ASRS-300 suppressor for SO42−. Detection limits (three times the standard deviation (3 SD) of ten measurements of standard solutions (Cat No. P/N 046070 for Na+ and P/N 057590 for SO42−) from Dionex; 0.4 and 5 μg L−1, respectively) for Na+ and SO42− are 1.2 and 0.58 μg L−1 for Na+ and SO42−, respectively. Calibration was performed using the diluted standard solutions. Analytical accuracy was 4.9% for Na+ and 5.6% for SO42−. All sample-handling and analytical procedures were performed inside Class 10 vertical laminar flow clean benches or clean booths installed inside Class 1000 laboratories at KOPRI. Further details regarding the analytical methods are provided elsewhere62,63,64.

In this study, the non-sea salt budget for SO42− (nssSO42−) was calculated using the following equation:

where [\({{\rm{Na}}}^{+}\)]sample and [\({{\rm{SO}}}_{4}^{2-}\)]sample are the measured concentrations of total Na+ and SO42−, respectively in the samples. [\({{\mathrm{SO}}}_{4}^{2-}\)/\({{\rm{Na}}}^{+}\)]seawater is the \({{\mathrm{SO}}}_{4}^{2-}\)/\({{\rm{Na}}}^{+}\) ratio (0.25 w/w) in bulk seawater65.

VK22 chronology

Considering the low snow accumulation at Vostok Station (22.5 ± 1.3 kg m−2 yr−1)66 and low-resolution depth intervals (an average of 9 cm) of the discrete samples taken from the VK22 firn core, the VK22 chronology was established using simple linear interpolation based on volcanic time markers, identified by comparing ECM and nssSO42− records with those from a 70.20-m-deep VK16 firn core drilled in the vicinity of Vostok Station in January 2018, which provided a well-dated record of volcanic eruptions over the past 2200 years60. Volcanic signals in the VK22 core, matching the VK16 core record, were likely associated with the eruptions of Mount Parker (1641 CE, Philippines), Huaynaputina (1600 CE, Peru), Nevado del Ruiz (1595 CE, Colombia), 1458/59 CE eruption, El Chichón (1345 CE, Mexico), Quilotoa (1286 CE, Ecuador), and Samalas (1257 CE, Indonesia) at the corresponding depth intervals of 16.99–17.06 m, 18.47–18.62 m, 18.74–18.89 m, 23.63–23.73 m, 27.29–27.47 m, 29.58–29.68 m, and 30.10–30.18 m, respectively. The synchronization of these volcanic markers from specific depth intervals in the two cores provided constraints for age-depth estimates from the 17.96 to 30.18 m depth interval for the VK22 core, corresponding to 1617 CE and 1256 CE, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3).

We defined the dating error by successive ‘switching off’ from one age marker to another and comparing the dates of discrete ice core sections with and without these markers, as detailed in ref. 60. This method enabled us to establish a simple linear relationship between the maximum dating error and the distance to the nearest age marker, expressed as

Both “Error” and “Distance” are in years. The constant term (3.1) in this equation represents the possible dating error inherent to the age markers themselves, which is attributed to their sampling resolution (an average of 3.1 years). The calculated error ranged from 3.3 to 9.8 years, with an average of 5.9 years.

Sample preparation for analyses of volcanic glass shards

The cryptotephra from the VK22 core were analyzed by taking two discrete samples from the specific depth intervals of 18.47–18.62 and 23.63–23.73 m, corresponding to the layers with cryptotephra from the 1600 CE Huaynaputina and the 1458/59 CE eruptions, respectively. Volcanic glass shards from the VK22 Huaynaputina cryptotephra layer were analyzed as secondary glass standards.

Aliquots of the samples were melted at room temperature, and unpolished individual glass shards were recovered by filtering ~3 mL of the samples through pre-cleaned gold (Au)-coated polycarbonate filters (13 mm diameter, 0.4-μm pore size; Sterlitech Corporation, USA) using a micropipette. After filtration, each filter was attached to an aluminum (Al) stub. All procedures were conducted inside a Class 10 clean bench installed in the Class 1000 clean laboratory at KOPRI. Normal polycarbonate or carbon-coated filters are commonly used in electron microprobe analysis to avoid spectral interference of X-ray emissions between the target and substrate. However, the Au X-ray lines do not overlap with those of the elements of interest in this study, and the Monte Carlo simulation-based method applied to determine the chemical compositions of glass shards allows the correction of interference effects in the layers on the substrates (see below). Accordingly, the Au-coated polycarbonate filter used in our study has suitable characteristics as a substrate for the analysis of glass shards.

Quantitative SEM–EDX measurement of unpolished micron-sized glass shards

Traditional EPMA quantification methods, such as ZAF and ϕ(ρz)-based procedures, require perfectly flat sample surfaces and homogenous compositions to mitigate geometric effects, as X-rays generated by the electron beam have different matrix effects among particles according to morphology. Furthermore, the side-scattering correction of the ϕ(ρz) function is feasible only when the electron excitation volume is smaller than the particle, particularly when the average atomic number of the substrate differs significantly from that of the particle67. Consequently, conventional EPMA methods have difficulty in quantifying the heterogeneous chemical compositions of submicron- to micron-sized particles with rough surfaces68. To overcome these limitations, a Monte Carlo simulation-based technique was applied to quantitative SEM–EDX chemical analyses of micron-sized glass shards without the polishing process. This technique is based on a modified version of the single-scattering CASINO Monte Carlo program69,70, which was originally designed to simulate generated characteristic X-ray and electron signals. The modified CASINO program enables the simulation of electron trajectories in particles with various morphologies on a given substrate, effectively accounting for the excitation interactions between electrons and matrix atoms, and the matrix and geometric effects of electron-induced X-ray signals for chemical elements in individual particles. This program also determines the characteristic and continuum (bremsstrahlung) background X-ray flux emitted from the underlying substrate, and the influence of the substrate on the energy distribution of the exciting electrons, consequently providing a correction for substrate-derived interference71. Subsequently, a method for quantifying the elemental compositions of particles was developed by combining Monte Carlo simulations with reverse successive approximations71,72,73,74. This quantification procedure yielded accurate results with a relative deviation of ≤12% for various types of standard particles75,76 and has been successfully applied to unpolished natural desert soil, aerosol, mineral dust, and volcanic ash particles in a multitude of studies over the past two decades77,78,79,80,81.

Glass shard analyses were performed at Inha University in the Republic of Korea using a JEOL JSM-6390 SEM instrument equipped with an Oxford Link SATW ultrathin window EDX detector with a 133 eV spectral resolution for Mn Kα X-rays. The operating conditions were set to an accelerating voltage of 10 kV, a beam current of 0.8 nA, and a measuring time of 20 s to avoid the time-dependent loss of Na intensity during electron bombardment82 and to maximize data precision33,83. The morphological parameters of each shard were obtained from the secondary electron images (SEIs) and set as the input parameters for the quantification procedure. The X-ray spectra were recorded using Oxford INCA Energy software (INCA suite version 4.09, Oxford Instruments Analytical Ltd., UK) and the EDX data were acquired through 1 μm single-point analyses on grain-free surface areas of unpolished shards to capture their intrinsic chemical compositions, as measurements on surfaces with adhered grains can yield inaccurate chemical results84. The net X-ray intensities of elements were obtained using a nonlinear least-squares method in the AXIL program85 and elemental concentrations were determined from X-ray intensities through the Monte Carlo simulation combined with reverse successive approximations. The elements determined included low-Z (C, O) and major (Na, Mg, Al, Si, K, Ca, Ti, and Fe) elements, as this quantification method was originally developed for the simultaneous quantification of low-Z and other elements from a single X-ray spectrum71. The elemental concentrations were provided as normalized values, summing to 100% in atomic fractions among the determined elements, based on the assumption that all the constituent elements were observed72. The atomic concentrations of the major elements were manually converted to weight percentage (wt%) concentrations, yielding a sum of 100%. The concentrations of minor elements (Mn and P) were not determined in this study because SEM–EDX analysis does not usually provide accurate results for these elements, which could ultimately lead to errors in the quantification of other oxides after normalization31,33,83.

The quality of these analyses was verified using unpolished micron-sized reference kaolinite particles (Cat No. 1318-74-7; Sigma–Aldrich, Germany), reference potassium feldspar particles (Cat No. 68476-25-5; National Institute of Standards and Technology, USA), in-house phonolitic glass shards (81003 G) from Mount Erebus in Antarctica86, certified basaltic and rhyolitic glass shards (USNM 113716, VG-A99, and VG-568) from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History87, and Huaynaputina glass shards preserved in the VK22 core. These reference materials were analyzed along with the VK22 cryptotephra in the same batch, except for the Smithsonian samples, which were measured separately. A good agreement was observed between the measured and certified values in the reference materials. While precision decreased at lower elemental concentrations, the absolute relative errors remained within acceptable ranges: 0.04–5.6% for elements >5 wt%, 0.15–16% for elements between 1 and 5 wt%, and 12–20% for elements between 0.5 and 1 wt% (Supplementary Data 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Statistical analysis

Two different tests of D2 and SC were performed to assess the geochemical similarities between the data and reference datasets, which helped discriminate the source volcanoes of the volcanic glass shards in the samples32,38,39,40. The D2 test determines whether there is a statistically significant difference between a matched pair and provides a means of assessing the degree of geochemical similarity between samples. Calculated D2 values greater than the critical value of 20.09 (eight degrees of freedom) indicated that a statistically significant difference existed between the two geochemical datasets. SC values greater than 0.92 strongly suggest that the geochemical signatures of distinct glass shards originate from the same volcanic source88. It is worth noting, however, that a wide range of geochemical compositions may induce higher D2 and lower SC values. Accordingly, the analysis was performed on eight major elemental oxides (SiO2, TiO2, Al2O3, FeO, MgO, CaO, Na2O, and K2O) with weight concentrations greater than 0.1% for D2 and 1% for SC, based on the method described by refs. 38,39.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data presented in this study are available in Supplementary Data and at https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.980746.

Code availability

A custom Monte Carlo calculation-based quantitative SEM–EDX technique, comprising nonlinear least-squares peak fitting implemented in the AXIL program (which necessitates Windows XP), a modified version of the CASINO Monte Carlo program, and multiple Microsoft Excel macros (compatible exclusively with Microsoft Office 2003), was used to quantify the compositions of unpolished, micro-sized glass shards. These in-house programs were calibrated to the specific SEM–EDX system used here (i.e., instrument, analytical conditions, and control software) and are not transferable to other hardware/software setups. Consequently, while this technique, initially developed by C.-U. Ro in 1999, has been extensively documented in numerous academic publications over the past two decades, the underlying custom source code and executables have not been made publicly available. Nevertheless, upon request to the corresponding author, we can share the program files used in this study, accompanied by a concise manual and a demonstration video illustrating their application to a standard material.

References

Bender, F. A.-M., Ekman, A. M. L. & Rodhe, H. Response to the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in relation to climate sensitivity in the CMIP3 models. Clim. Dyn. 35, 875–886 (2010).

Kloss, C. et al. Stratospheric aerosol layer perturbation caused by the 2019 Raikoke and Ulawun eruptions and their radiative forcing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 535–560 (2021).

Mann, M. E., Steinman, B. A., Brouillette, D. J. & Miller, S. K. Multidecadal climate oscillations during the past millennium driven by volcanic forcing. Science 371, 1014–1019 (2021).

Fuglestvedt, H., Zhuo, Z., Toohey, M. & Krüger, K. Volcanic forcing of high-latitude Northern Hemisphere eruptions. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 10 (2024).

Sigl, M. et al. A new bipolar ice core record of volcanism from WAIS Divide and NEEM and implications for climate forcing of the last 2000 years. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 1151–1169 (2013).

Sigl, M. et al. Insights from Antarctica on volcanic forcing during the Common Era. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 693–697 (2014).

Sigl, M. et al. Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years. Nature 523, 543–549 (2015).

Schneider, L., Smerdon, J. E., Pretis, F., Hartl-Meier, C. & Esper, J. A. new archive of large volcanic events over the past millennium derived from reconstructed summer temperatures. Environ. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa9426 (2017).

Burke, A. et al. High sensitivity of summer temperatures to stratospheric sulfur loading from volcanoes in the Northern Hemisphere. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2221810120 (2023).

Arfeuille, F. et al. Volcanic forcing for climate modeling: a new microphysics-based data set covering years 1600-present. Clim. Past 10, 359–375 (2014).

Toohey, M. et al. Disproportionately strong climate forcing from extratropical explosive volcanic eruptions. Nat. Geosci. 12, 100–107 (2019).

Marshall, L. R. et al. Large variations in volcanic aerosol forcing efficiency due to eruption source parameters and rapid adjustments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090241 (2020).

Esper, J. et al. Large-scale, millennial-length temperature reconstructions from tree-rings. Dendrochronologia 50, 81–90 (2018).

Büntgen, U. et al. Prominent role of volcanism in Common Era climate variability and human history. Dendrochronologia https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dendro.2020.125757 (2020).

Gao, C. et al. The 1452 or 1453 A.D. Kuwae eruption signal derived from multiple ice core records: Greatest volcanic sulfate event of the past 700 years. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005jd006710 (2006).

Plummer, C. T. et al. An independently dated 2000-yr volcanic record from Law Dome, East Antarctica, including a new perspective on the dating of the 1450s CE eruption of Kuwae, Vanuatu. Clim. Past 8, 1929–1940 (2012).

Cole-Dai, J. et al. Two likely stratospheric volcanic eruptions in the 1450s C.E. found in a bipolar, subannually dated 800 year ice core record. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 7459–7466 (2013).

Abbott, P. M. et al. Cryptotephra from the Icelandic Veiðivötn 1477 CE eruption in a Greenland ice core: confirming the dating of volcanic events in the 1450s CE and assessing the eruption’s climatic impact. Clim. Past 17, 565–585 (2021).

Briffa, K. R., Jones, P. D., Schweingruber, F. H. & Osborn, T. J. Influence of volcanic eruptions on Northern Hemisphere summer temperature over the past 600 years. Nature 393, 450–455 (1998).

Stoffel, M. et al. Estimates of volcanic-induced cooling in the Northern Hemisphere over the past 1,500 years. Nat. Geosci. 8, 784–788 (2015).

Wilson, R. et al. Last millennium northern hemisphere summer temperatures from tree rings: part I: the long term context. Quat. Sci. Rev. 134, 1–18 (2016).

Esper, J., Büntgen, U., Hartl-Meier, C., Oppenheimer, C. & Schneider, L. Northern Hemisphere temperature anomalies during the 1450s period of ambiguous volcanic forcing. Bull. Volcanol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-017-1125-9 (2017).

Gautier, E. et al. 2600-years of stratospheric volcanism through sulfate isotopes. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08357-0 (2019).

Hartman, L. H. et al. Volcanic glass properties from 1459 C.E. volcanic event in South Pole ice core dismiss Kuwae caldera as a potential source. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50939-x (2019).

Robin, C., Monzier, M. & Eissen, J.-P. Formation of the mid-fifteenth century Kuwae caldera (Vanuatu) by an initial hydroclastic and subsequent ignimbritic eruption. Bull. Voncanol. 56, 170–183 (1994).

Witter, J. B. & Self, S. The Kuwae (Vanuatu) eruption of AD 1452: potential magnitude and volatile release. Bull. Volcanol. 69, 301–318 (2007).

Strandberg, N. A. et al. Island ecosystem responses to the Kuwae eruption and precipitation change over the last 1600 years, Efate, Vanuatu. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11, 1087577 (2023).

Stern, C. R. Holocene tephrochronology record of large explosive eruptions in the southernmost Patagonian Andes. Bull. Volcanol. 70, 435–454 (2008).

Del Carlo, P. et al. Late Glacial-Holocene tephra from southern Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego (Argentina, Chile): a complete textural and geochemical fingerprinting for distal correlations in the Southern Hemisphere. Quat. Sci. Rev. 195, 153–170 (2018).

Smith, R. E. et al. Refining the Late Quaternary tephrochronology for southern South America using the Laguna Potrok Aike sedimentary record. Quat. Sci. Rev. 218, 137–156 (2019).

Iverson, N. A., Kalteyer, D., Dunbar, N. W., Kurbatov, A. & Yates, M. Advancements and best practices for analysis and correlation of tephra and cryptotephra in ice. Quat. Geochronol. 40, 45–55 (2017).

Lowe, D. J. et al. Correlating tephras and cryptotephras using glass compositional analyses and numerical and statistical methods: Review and evaluation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 175, 1–44 (2017).

Innes, H. M., Hutchison, W. & Burke, A. Geochemical analysis of extremely fine-grained cryptotephra: New developments and recommended practices. Quat. Geochronol. 83, 101553 (2024).

Hunt, J. B. & Hill, P. G. Tephra geochemistry: a discussion of some persistent analytical problems. Holocene 3, 271–278 (1993).

Hayward, C. High spatial resolution electron probe microanalysis of tephras and melt inclusions without beam-induced chemical modification. Holocene 22, 119–125 (2012).

Kuehn, S. C. & Froese, D. G. Tephra from ice – a simple method to routinely mount, polish, and quantitatively analyze sparse fine particles. Microsc. Microanal. 16, 218–225 (2010).

Hall, M. & Hayward, C. Preparation of micro- and crypto-tephras for quantitative microbeam analysis. Geo. Soc. Spec. Publ. 398, 21–28 (2014).

Perkins, M. E., Nash, W. P., Brown, F. H. & Fleck, R. J. Fallout tuffs of Trapper Creek, Idaho–a record of Miocene explosive volcanism in the Snake River Plain volcanic province. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 107, 1484–1506 (1995).

Perkins, M. E., Brown, F. H., Nash, W. P., McIntosh, W. & Williams, S. K. Sequence, age, and source of silicic fallout tuffs in middle to late Miocene basins of the northern Basin and Range province. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 110, 344–360 (1998).

Borchardt, G. A., Aruscavage, P. J. & Millard, H. J. Correlation of the Bishop Ash, a Pleistocene marker bed, using instrumental neutron activation analysis. J. Sediment. Res. 42, 301–306 (1972).

Garg, D., Papale, P., Colucci, S. & Longo, A. Long-lived compositional heterogeneities in magma chambers, and implications for volcanic hazard. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40160-1 (2019).

Robock, A. Volcanic eruptions and climate. Rev. Geophys. 38, 191–219 (2000).

Lee, G. et al. Phasing and climate forcing potential of the Millennium Eruption of Mt. Baekdu. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 549 (2024).

Bernard, O. & Bouvet de Maisonneuve, C. Controls on eruption style at Rabaul, Papua New Guinea – Insights from microlites, porosity and permeability measurements. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.volgeores.2020.107068 (2020).

Siebert, L., Simkin, T. & Kimberly, P. Volcanoes of the World 3rd edn (Univ. California Press, 2011).

Moy, C. M. et al. Isotopic evidence for hydrologic change related to the westerlies in SW Patagonia, Chile, during the last millennium. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 1335–1349 (2008).

Delmonte, B. et al. Dust size evidence for opposite regional atmospheric circulation changes over east Antarctica during the last climatic transition. Clim. Dyn. 23, 427–438 (2004).

Delmonte, B. et al. Holocene dust in East Antarctica: provenance and variability in time and space. Holocene 30, 1–13 (2020).

Neff, P. D. & Bertler, N. A. N. Trajectory modeling of modern dust transport to the Southern Ocean and Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 9303–9322 (2015).

Niemeier, U. et al. Initial fate of fine ash and sulfur from large volcanic eruptions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 9043–9057 (2009).

Eychenne, J. & Engwell, S. L. The grainsize of volcanic fall deposits: spatial trends and physical controls. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 135, 1844–1858 (2023).

Fiacco, R. J., Palais, J. M., Germani, M. S., Zielinski, G. A. & Mayewski, P. A. Characteristics and possible source of a 1479 A.D. volcanic ash layer in a Greenland ice core. Quat. Res. 39, 267–273 (1993).

Koffman, B. G., Kreutz, K. J., Kurbatov, A. V. & Dunbar, N. W. Impact of known local and tropical volcanic eruptions of the past millennium on the WAIS Divide microparticle record. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 4712–4716 (2013).

Abbott, P. M. et al. Mid-to Late Holocene East Antarctic ice-core tephrochronology: implications for reconstructing volcanic eruptions and assessing their climatic impacts over the last 5,500 years. Quat. Sci. Rev. 329, 108544 (2024).

Koffman, B. G. et al. Rapid transport of ash and sulfate from the 2011 Puyehue-Cordón Caulle (Chile) eruption to West Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 8908–8920 (2017).

Koffman, B. G. et al. Centennial-scale variability of the Southern Hemisphere westerly wind belt in the eastern Pacific over the past two millennia. Clim. Past 10, 1125–1144 (2014).

Kreutz, K. J. South Pole (SPC14) microparticle concentration, mass concentration, flux, particle-size-distribution mode, and aspect ratio measurements. U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) Data Center. https://doi.org/10.15784/601553 (2022).

Rose, W. I. & Durant, A. J. Fine ash content of explosive eruptions. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 186, 31–39 (2009).

Veres, A. N., Ekaykin, A. A., Lipenkov, V. Y., Turkeev, A. V. & Khodzher, T. V. First data on the climate variability in the vicinity of Vostok Station (Central Antarctica) over the past 2,000 years based on the study of a snow-firn core. Arctic Antarctic Res. 66, 482–500 (2020). in Russian.

Veres, A. N. et al. A record of volcanic eruptions over the past 2,200 years from Vostok firn cores, central East Antarctica. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1075739 (2023).

Han, C. et al. Determination of lead isotopes in a new Greenland deep ice core at the sub-picogram per gram level by thermal ionization mass spectrometry using an improved decontamination method. Talanta 140, 20–28 (2015).

Hong, S.-B. et al. Uncertainties of ionic species in snowpit samples determined with ion chromatography system. Anal. Sci. Technol. 25, 350–363 (2012). in Korean.

Ro, S. et al. An improved ion chromatography system coupled with a melter for high-resolution ionic species reconstruction in Antarctic firn cores. Microchem. J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2020.105377 (2020).

Ro, S. et al. Variability of sea salt and methanesulfonate in firn cores from northern Victoria Land, Antarctica: their links to oceanic and atmospheric condition variability in the Ross Sea. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 896470 (2022).

Kester, D., Duedall, I., Connors, D. & Pytkowicz, R. Preparation of artificial seawater. Limnol. Oceanogr. 12, 176–179 (1967).

Ekaykin, A. A., Lipenkov, V. Y. & Tebenkova, N. A. Fifty years of instrumental surface mass balance observations at Vostok Station, central Antarctica. J. Glaciol. 69, 1705–1717 (2023).

Armstrong, J. T. & Buseck, P. R. A general characteristic fluorescence correction for the quantitative electron microbeam analysis of thick specimens, thin films and particles. X-Ray Spectrom. 14, 172–182 (1985).

Armstrong, J. T. in Electron Probe Quantitation (eds. Heinrich, K. F. J. & Newbury, D. E.) (Plenum Press, 1991).

Hovington, P., Drouin, D. & Gauvin, R. CASINO: A new monte carlo code in C language for electron beam interactions – part I: description of the program. Scanning 19, 1–14 (1997).

Drouin, D., Hovington, P. & Gauvin, R. CASINO: A new monte carlo code in C language for electron beam interactions – part II: tabulated values of the mott cross section. Scanning 19, 20–28 (1997).

Ro, C.-U., Osán, J. & Van Grieken, R. Determination of low-Z elements in individual environmental particles using windowless EPMA. Anal. Chem. 71, 1521–1528 (1999).

Ro, C.-U. et al. A Monte Carlo program for quantitative electron-induced X-ray analysis of individual particles. Anal. Chem. 75, 851–859 (2003).

Osán, J., Szalóki, I., Ro, C.-U. & Van Grieken, R. Light element analysis of individual microparticles using thin-window EPMA. Mikrochim. Acta 132, 349–355 (2000).

Szalóki, I., Osán, J., Ro, C.-U. & Van Grieken, R. Quantitative characterization of individual aerosol particles by thin-window electron probe microanalysis combined with iterative simulation. Spectrochim. Acta Part B 55, 1017–1030 (2000).

Ro, C.-U. et al. Determination of chemical species in individual aerosol particles using ultrathin window EPMA. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34, 3023–3030 (2000).

Ro, C.-U. et al. Chemical speciation of individual atmospheric particles using low-Z electron probe X-ray microanalysis: characterizing “Asian Dust” deposited with rainwater in Seoul, Korea. Atmos. Environ. 35, 4995–5005 (2001).

Hwang, H. & Ro, C.-U. Single-particle characterization of “Asian Dust” certified reference materials using low-Z particle electron probe X-ray microanalysis. Spectrochim. Acta B 61, 400–406 (2006).

Kim, H., Hwang, H. & Ro, C.-U. Single-particle characterization of soil samples collected at various arid areas of China, using low-Z particle electron probe X-ray microanalysis. Spectrochim. Acta B 61, 393–399 (2006).

Malek, M. A., Kim, B., Jung, H.-J., Song, Y.-C. & Ro, C.-U. Single-particle mineralogy of Chinese soil particles by the combined use of low-Z particle electron probe X-ray microanalysis and attenuated total reflectance-FT-IR imaging techniques. Anal. Chem. 83, 7970–7977 (2011).

Malek, M. A. et al. Single particle mineralogy of microparticles from Himalayan ice-cores using SEM/EDX and ATR-FTIR imaging techniques for identification of volcanic ash signatures. Chem. Geol. 504, 205–215 (2019).

Ro, S. et al. Millennial-scale variability of Greenland dust provenance during the last glacial maximum as determined by single particle analysis. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52546-x (2024).

Nielsen, C. H. & Sigurdsson, H. Quantitative methods for electron microprobe analysis of sodium in natural and synthetic glasses. Am. Mineral. 66, 547–552 (1981).

Guyett, P. C. et al. Optimizing SEM-EDX for fast, high-quality and non-destructive elemental analysis of glass. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 39, 2565 (2024).

Piva, S. B. et al. Volcanic glass from the 1.8 ka Taupo eruption (New Zealand) detected in Antarctic ice at ~230 CE. Sci. Rep. 13, 16720 (2023).

Vekemans, B., Janssens, K., Vincze, L., Adams, F. & Van Espen, P. Analysis of X-ray spectra by iterative least squares (AXIL): New developments. X-ray Spectrom. 23, 278–285 (1994).

Kelly, P. J., Kyle, P. R., Dunbar, N. W. & Sims, K. W. W. Geochemistry and mineralogy of the phonolite lava lake, Erebus volcano, Antarctica: 1972–2004 and comparison with older lavas. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 177, 589–605 (2008).

Jarosewich, E. & Nelen, J. A. & Norberg. Reference samples for electron microprobe analysis. J. A. Geostand. Newsl. 4, 43–47 (1980).

Froggatt, P. C. Standardization of the chemical analysis of tephra deposits: report of the ICCT working group. Quatern. Int. 13-14, 93–96 (1992).

Le Bas, M. J., Le Maitre, R. W., Streckeisen, A. & Zanettin, B. A chemical classification of volcanic rocks based on the total alkali-silica diagram. J. Petrol. 27, 745–750 (1986).

Breton, D. J., Koffman, B. G., Kurbatove, A. V., Kreutz, K. J. & Hamilton, G. S. Quantifying signal dispersion in a hybrid ice core melting system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 11922–11928 (2012).

Kreutz, K. J. & Koffman, B. G. WAIS Divide microparticle concentration and size distribution, 0-2400 ka. U. S. Antarctic Program (USAP) Data Center. https://doi.org/10.7265/N5KK98QZ (2015).

Winski, D. A. South Pole ice core Holocene major ion dataset. U. S. Antarctic Program (USAP) Data Center. https://doi.org/10.15784/601399 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a research grant (PE23905-360-05) funded by Polar Academic Program (PAP) from the Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI) and a research grant (PE25100) from KOPRI. The drilling of the VK22 hole was conducted within the framework of the Russian Science Foundation grant 25-17-00172. The authors are grateful to all participants of the Russian Antarctic Expedition and KOPRI technicians and engineers for their efforts in achieving, preparing, and measuring the VK22 firn core samples. We particularly wish to thank Dr. Alexey Bolshunov and his colleagues from St Petersburg Mining University for their help and support during ice core drilling.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.R. and S.D.H. contributed equally. S.R., S.D.H., Y.H. and S.H. designed the project. A.E. and A.V. performed the ECM analyses. S.R., S.L., J.M., H.J., and A.L. performed the ice core decontamination. S.-B.H. and C.C. performed ion concentration analyses. S.R. and C.-U.R. performed glass shard analyses. The original manuscript was written by S.R. and S.H., with contributions of S.D.H., A.E., Y.H. and M.J.L. to manuscript revision. All of the authors have read and approved the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Takehiko Suzuki, Gill Plunkett and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Domenico Doronzo, Alireza Bahadori and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ro, S., Hur, S.D., Ekaykin, A. et al. Origin of the 1458/59 CE volcanic eruption revealed through analysis of glass shards in the firn core from Antarctic Vostok station. Commun Earth Environ 6, 828 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02797-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02797-x