Abstract

Earthquakes are among the most destructive natural hazards whose released energy can be quantified by their magnitude. Predicting how much energy will be released before the end of the rupture process represents a challenging question. The way earthquake ruptures grow, propagate and arrest determines the final size: small-to-moderate ruptures evolve in few seconds within few kilometers, while large-to-huge events develop in tens of seconds and several hundred kilometers. If the rupture process starts in the same way for small and large earthquakes, no deterministic prediction of the final size is feasible, until the process has completed. Instead, if the source mechanism starts differently from its beginning, real-time proxies can be measured on early radiated waves to discriminate the final event size. Here we show that the initial ground displacement grows differently for small and large earthquakes, based on the analysis of an unprecedented catalog of seismic waveforms from worldwide earthquakes. The result supports the hypothesis of early predictable magnitude for a wide range of different earthquakes in diverse geological settings. This study confirms that the initial growth of displacement can be used for a fast magnitude estimation, making it potentially feasible for future implementation in early warning systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The generation mechanism of earthquakes is a long-standing issue in seismology, for which a straightforward and established description has not yet been provided. It is hypothesized from theoretical analyses and laboratory experiments1,2 that seismic ruptures begin with a process of quasi-static slip accumulation over a limited region of the fault. Here, the slip slowly accumulates until reaching a critical threshold, beyond which the fracture becomes unstable and triggers the dynamic propagation1,2,3,4. While the quasi-static phase (referred to as the preparatory phase) has no definite beginning and duration, the time during which the rupture accelerates to the dynamic propagation (referred to as the break-out phase), in contrast, is thought to be well defined and relatively short1.

The unresolved question is whether, and to what extent, the physical mechanisms that initiate seismic rupture provide information about the final size of an earthquake. Specifically, it remains unclear whether all earthquakes begin through a similar process—characterized by the exceedance of a yield stress and influenced by local frictional properties or geometric complexities of the fault surface5—with the rupture extent determined during propagation, or whether fundamentally different initiation mechanisms govern small vs. large events6,7,8,9.

Most of the literature studies focused on the analyses of the P-wave onset of real earthquakes to shed light on the mechanism of generation of seismic ruptures and to understand the role of the parameters involved in the process10,11,12,13. Observations provided so far are contradictory, due to the use of different types of data, frequency scales and methodological approaches.

Several authors7,13,14,15,16,17 did not observe any scaling of the P-wave onset with the final earthquake size, or they interpreted it in terms of biases due to data processing and/or wave propagation (attenuation) effects. These authors supported the idea of a universal behavior of the seismic rupture onset, for which there is no natural predisposition for a rupture to grow to a large earthquake since the beginning of the rupture process. Other studies10,18,19,20,21 provided evidence for a deterministic nature of the seismic rupture, showing straightforward relationships between the early signals radiated by the source and the final earthquake size. Among them, at the time scale of seconds to tens of seconds Melgar and Hayes22 provided evidence that the initial growth-rate amplitude is higher for larger events and lower for smaller ones, although some questions arise about the time range of their analysis being comparable to the time peak of the moment rate function (MRF)23. At a much shorter time scale (seconds or shorter), observations of the early recorded amplitude on a limited catalog of past Japanese earthquakes12,21 have shown that the initial growth-rate amplitude is lower for larger events and higher for smaller ones. The main limitation of previous studies lies in the small number of available observations and the high variability in the data, which means that the concept of rupture determinism remains uncertain and considered as lacking of strong empirical support.

Here, we show that the initial ground displacement growth behaves differently for small and large earthquakes by analyzing an unprecedented catalog of seismic waveforms from worldwide earthquakes. Our results support the hypothesis of early predictable event magnitude for a wide range of different-sized earthquakes in diverse geological settings, regardless of the distance from the event location. The initial ground displacement rate is interpreted here in terms of a characteristic time of the rupture process, during which changes of the critical slip weakening distance and/or rupture slip/velocity can occur and increase with the final earthquake size. This study confirms that the measurement of the initial growth of displacement can be used as a proxy for a fast magnitude estimation, making it potentially feasible for future implementation in early warning systems.

Results

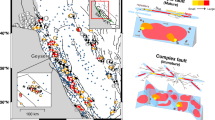

We analyzed 200 earthquakes with magnitude between 4 and 9 occurred worldwide (Fig. 1). For each event, we selected the seismic records of stations which fall within a circular ring of 25 km width starting from the nearest station to the event epicenter (see inset in Fig. 2A) and using both velocimetric or accelerometric waveforms, depending on the availability of data (Fig. 1). We perform a single or a double integration of the signal to get displacement, respectively. The logarithm of the peak of the absolute displacement is computed starting from the P-wave arrival time and then, by averaging the station curves, a single event curve is obtained, hereinafter referred to as the LPDT curve (Fig. 2). For each curve, we identified the plateau time and then measured the initial slope on the curves from the line that crosses the LPDT curve in its early part (see “Methods” section). The plot of Fig. 2 shows that for different magnitude classes (Mw = 4 in cyan and Mw = 7 in red), the initial slope is steeper for lower magnitude events and more gradual for higher magnitude events. Additionally, we observe that the time window used to evaluate the initial slope increases with magnitude.

The figure shows the epicentral position of the events used in this study (colored circles). The size of the circles is proportional to the earthquake magnitude, and the color shows the event depth. Black triangles are the velocimeter sensors, while yellow reversed triangles represent accelerometer sensors. The histogram in the bottom left shows the distribution of records in each magnitude bin.

A Color represents two different magnitude values (cyan is Mw = 4, red is Mw = 7). Dotted lines show the LPDT curves at each station; thick lines show the averaged LPDT curve. The circle (corresponding to tMIN = 0.05 s) is the starting point for the slope evaluation. The diamond (tHALF) is the ending point for slope evaluation, corresponding to half-time of the maximum LPDT curvature. Slope is evaluated as \(({{\rm{L}}}{{\rm{P}}}{{\rm{D}}}{{\rm{T}}}({{t}}_{{{\rm{H}}}{{\rm{A}}}{{\rm{L}}}{{\rm{F}}}})-{{\rm{L}}}{{\rm{P}}}{{\rm{D}}}{{\rm{T}}}({{t}}_{{{\rm{M}}}{{\rm{I}}}{{\rm{N}}}}))/({{t}}_{{{\rm{H}}}{{\rm{A}}}{{\rm{L}}}{{\rm{F}}}}-{{t}}_{{{\rm{M}}}{{\rm{I}}}{{\rm{N}}}})\). The figure inset shows a sketch of station selection for LPDT curves evaluation: only the records between the closest station to the event epicenter (yellow star) falling within a circular crown of 25 km are taken into account. B shows an example of the averaged LPDT curve for each magnitude bin. To appreciate initial slope variation, the curves are shifted to their initial point LPDT0. C shows the LPDT curvatures of LPDT in (B). The maximum curvature is reached at the plateau level of each LPDT curve.

The main result of this study is illustrated in Fig. 3, where the slope measurements along the initial rise of LPDT curves are represented as a function of magnitude (Fig. 3A). When evaluated over a large spectrum of magnitudes and for different tectonic areas worldwide, the early part of the log-displacement vs. time curves measured along the P-wave portion of stations in close-proximity distances (maximum distance difference of 25 km between the closest and the furthest stations from event epicenter) show a clear decreasing linear trend with the earthquake magnitude. The time window in which this estimate is done also depends on the final earthquake magnitude, with larger time windows being necessary to measure the initial slope for larger magnitude events (Fig. 3B). Given the variability and uncertainties of measurements, the observed standard error of the linear regressions suggests an uncertainty of about one magnitude unit associated with the slope measurement obtained by averaging the values at the stations within a very narrow (25 km) circular ring starting from the nearest station to epicenter. Furthermore, the correlation t test (Table 1) conducted on both the negative linear relationship between the logarithm of the slope and magnitude, and the positive linear relationship between the corresponding time window and magnitude, confirms the statistical significance of the observed linear trends between the two sets of variables. Specifically, a robust anti-correlation is found between the logarithm of the slope and the magnitude, while a clear correlation between the characteristic time window and magnitude is observed, as confirmed by the two correlation coefficients r and the related p-values (Table 1). Overall, Fig. 3 shows that a P-wave time window of about 1 s is sufficient to discriminate between small–moderate (M < 5.5) and large (M > 6.5) earthquakes and to determine their magnitude with the specified uncertainty.

A, C shows the initial slope of LPDT curves as a function of magnitude for tHALF and tTHIRD, respectively. B, D show the time at which LPDT curves reach half and third of the maximum of their curvature (tHALF and tTHIRD, respectively) as a function of magnitude. In all panels, gray dots are single slope and time measurements, while red squares are the average values for each magnitude bin (bin width = 1). The solid black line represents the best-fit line, along with ± one-SE (standard error) thin lines. The fit parameters and the SE values are shown at the bottom left of the panel. B, D also show a shaded blue area including all the possible peak time values resulting from the computation of the MRFs. Minimum and maximum peak times and the corresponding stress drop and rupture velocity combinations are shown as the contour of the shaded area with solid blue lines.

Discussion

We show here that the P-wave signals associated with large earthquakes typically begin with a slow initial amplitude growth in the first few seconds, while the P-wave signals radiated by small events are mainly characterized by a rapid amplitude increase in a shorter time. The results are consistent with observations from previous works12,21 that focused on the analysis of a limited number of Japanese earthquakes, recorded at regional distances (R < 100–200 km), with most of the events having magnitudes below 6 and very few of them having larger magnitudes (above 7).

We used a massive catalog of worldwide earthquakes, from different tectonic areas and geological settings, including normal fault zones, strike-slip environments, as well as major earthquakes from subduction zones. Our study is based on over 7000 seismic records spanning a wide distance range (0–500 km), providing a robust catalog where all magnitude classes are well represented by a consistent number of data points. We manually picked the P-wave arrival times from all available waveforms, resulting in an unprecedented dataset in terms of both the quantity and quality of recorded data.

We adopted a straightforward workflow for data processing that minimizes artificial contaminations and potential bias of results. One potential source of bias could stem from the high-pass filtering applied to the displacement data. However, we followed the approach outlined by Colombelli12, who addressed this issue, demonstrating that the slope calculated from displacement records derived from unfiltered acceleration and velocity data maintains the scaling trend with magnitude. Another potential bias could arise from geometric or anelastic attenuation of the radiated wavefield over distance. While Colombelli12 showed that slope measurements from LPDT curves are only weakly affected by distance attenuation, for this analysis we selected records from a narrow circular zone (25 km wide) to minimize distance attenuation effects. The potential directivity effect is mitigated by averaging LPDT curves distributed azimuthally within the selected circular zone to evaluate the initial slope. The variability in slope caused by unaccounted directivity and distance attenuation contributes to uncertainty in the event slope measurements (Fig. S3), but this uncertainty is smaller than the variability range of the log-slope vs. magnitude shown in Fig. 3. Finally, we observe that deep earthquakes (depth >30 km) tend to exhibit slightly higher slope values compared to shallow events of the same magnitude (see Fig. S5), which may indicate different stress and/or friction conditions that govern the initial rupture process of deep, mainly subduction zone, earthquakes. Although the in-depth analysis of such a differential mechanism is beyond the scope of our study, we note that the overall scaling of the initial slope with magnitude is preserved, independent of the event depth.

We adopted a simple scheme for the early P-wave slope measurement that does not require complex signal processing or manipulations. We identified the plateau time on the LPDT curves by analyzing the curvature and then directly measured the initial slope on the curves between tMIN = 0.05 s and tHALF corresponding to half of the estimated plateau time (see “Methods section” for more details). Slope measurements are directly obtained from the observed log-displacement evolution, with no use of interpolated models or fitted curves.

Our results show that the initial slope of LPDT curves decreases with magnitude, with an average value of about 20 s−1 for M = 4 earthquakes and about 2 s−1 for M = 9 events (Fig. 3A). The time at which the slope is measured increases with magnitude, being approximately 0.2 s for M = 4 earthquakes and about 1 s for M = 9 events (Fig. 3B). The times measured here are related to the plateau time of LPDT curves which are, in turn, a proxy for the peak of the MRF20,23. Indeed for M = 4 the typical MRF duration is between 0.5 and 1 s, whereas for M = 7 the typical MRF duration is between 5 and 15 s24. We evaluated the relative portion of the analyzed time window (tHALF) compared to the peak (tPEAK) of MRFs for different magnitude earthquakes, according to the Sato and Hirasawa model25 and exploring a broad range of stress drop (between 0.1 and 10 MPa) and rupture velocity values (between 0.5 and 0.9 of the shear wave velocity)26,27. Figure 3A compares the two time windows (tHALF and tPEAK) for each magnitude. The peak time of the computed MRFs (shown as a shaded blue area) varies between 0.2 and 0.6 s for M = 4, between 0.3 and 1 s for M = 5, between 0.8 and 3 s for M = 6, and between 2 and 10 s for M = 7. For the very small events (M < 5), our time window (tHALF) is partially overlapped by the lower bound of the shaded area, suggesting that the analyzed time window can be of the same order as the peak of MRF only in the case of very high values of both stress drop (10 MPa) and rupture velocity (0.9 vs). For M > 5, the tHALF time window is on average smaller than the lowest values of tPEAK. As the magnitude increases, the difference between the two times becomes more evident.

The choice of the time to measure the slope is arbitrary (half of the plateau time of the curves), since any shortest interval could be used, provided that a sufficient number of data points are considered for the linear fitting of the initial slope. In Fig. 3C, D, we compared the results in terms of slope and related time using a smaller time window, equal to tTHIRD of the plateau level. As expected, when using tTHIRD, the considered time window is smaller than the tPEAK for all the computed MRFs in the entire magnitude range, while the initial slope measurement is still stable. However, the absolute individual values of slope depend on the time window at which they are measured. Therefore, we do not interpret the physical meaning of absolute slope values and related times but only focus on and discuss their scaling over the entire magnitude range.

Our observation suggests that the initial displacement growth of small earthquakes is faster than for large earthquakes. There are two relevant aspects resulting from this result that need to be clarified and that are related to two different time scales during the rupture process.

At short time scale (e.g., within 1–2 s after the P-wave arrival), our observations contrast with the idea of a universal, identical onset for all earthquakes, which has been suggested by various authors so far15,17. Although being conceptually like the initial amplitude rate measured in this study, none of the previous works measured the initial slope of the P-wave displacement amplitude with the same quantitative parameter (the slope) as we did here. Therefore, no direct comparison of such different results can be done. Moreover, significant differences in the processing of data may justify the observed differences in the initial rate of the P-wave displacement amplitude. We provide a detailed discussion about the most significant differences with previous works in Text S2 of the Supplementary Material.

At longer time scales (several to tens of seconds after P-wave arrival, corresponding to the peak of the MRF), Melgar and Hayes22 analyzed a dataset of source time functions from large to very large earthquakes (M 7–9) and showed that events of different magnitudes can be distinguished after the initial rupture phase. They observed that ground motion amplitudes eventually become higher for M9 than for M7, suggesting an inverse scaling with magnitude—contrary to our findings. In our study, we focused on the first 1–2 s after the P-wave arrival and did not analyze the behavior of LPDT curves at later stages, particularly near or beyond their plateau. Given that LPDT is defined as the maximum of the logarithmic time evolution of Pd, we cannot retrieve its decaying portion from our data. Consequently, our current dataset and methodology do not allow us to assess the growth of MRFs at later stages, and our results do not rule out the longer-term source evolution described in other studies15,22.

Another aspect to consider is that, whatever the initial behavior of the source process is, self-similar scaling relationships (e.g., total duration vs. seismic moment) provide constraints to the macro source parameters, at the entire scale. We suggest a potential hypothesis that could bring together our observations at short time scales with observations done at long time scales22, while keeping the expected scaling relationships between source parameters.

At laboratory scale, it has been shown that during the preparatory phase of earthquake ruptures, the crack size increases slowly at a few percent of the shear wave speed1,4 until it reaches a critical size related to the frictional parameters (such as the slip-weakening critical distance, Dc). At this point, the unstable fracture expands at an increasing velocity, with an acceleration stage that finally triggers the dynamic propagation at seismic or sub-seismic velocities1,2,3,4. The time during which rupture accelerates to the dynamic propagation is well defined and observed to be related to the final slip1. Moreover, in some numerical modeling and laboratory experiments, the slip-weakening critical distance, Dc, is related to the final slip, which in turn scales with the earthquake magnitude1,28. With this in mind, the scaling of times and slopes observed here could be the footprint of this unstable acceleration phase and could corroborate the idea that earthquakes are different already at the beginning of the rupture process. Intuitively, at the scale of real earthquakes longer times are needed to reach this condition on a limited portion of the fault for larger events, thus implying a smaller rate of amplitude growth. Therefore, a long duration of the rupture acceleration (i.e., large Dc, large magnitude) is associated with a low rate of amplitude increase (i.e., a small slope value). Conversely, for small events, the smaller Dc value is reached in a shorter time on a limited portion of the fault, with consequent higher rates of amplitude growth. A short duration of the acceleration phase is therefore associated with high values of the amplitude growth rate (large slopes). Thus, the break-out phase is different for small and large events, and this difference can be seen within a “characteristic time” of the process itself (Fig. 4). We clarify that the hypothesis of the scaling of Dc with earthquake magnitude has been supported so far only by laboratory-scale experiments1. Extrapolating these findings to the natural earthquakes remains non-trivial, since no direct observations of Dc at the scale of small, moderate, and large events are available.

The figure shows a plot of logarithm of initial LPDT slope vs. tHALF of the earthquakes used in this work. Circle markers are single-event data; squares are the averaged value in the magnitude bin. The average slope value ranges from 20 for magnitude = 4 events to 2 for magnitude = 9 events; the average time required to evaluate the initial slope ranges from 0.2 s for magnitude = 4 events to 1 s for magnitude = 9 events.

Once the dynamic propagation has started and until the peak values of the source process (MRF), the amplitude could either (a) grow with an increasing rate with magnitude or (b) maintain the same growth rate with magnitude, leading in both cases to absolute peak amplitudes and related times, which are consistent with those predicted from the scaling laws29.

In the first case (a), after the initial slower acceleration of the breakout phase, large events could then accelerate more than small events, reaching higher rupture velocities and even supershear ruptures, as often estimated from the inversion of recorded seismograms30,31.

In the second case, small and large earthquakes could mainly differentiate only during the breakout phase, but then converge to a similar rupture velocity, common to all ruptures. As a support of the second case, we computed the duration-moment scaling produced by a Sato and Hirasawa25 circular rupture model where a linear decreasing rupture velocity is assigned for an increasing moment magnitude in the range Mw 4–8. Indeed, based on the dynamic-consistent model for an expanding shear circular crack of Sato and Hirasawa \({\Omega }_{P}\left(t\right)\), the relation between the early P radiated displacement pulse  \({\tau }_{e}\)(

\({\tau }_{e}\)( ) \({v}_{R}\)(

) \({v}_{R}\)( ) during the rupture growth phase can be written as32:

) during the rupture growth phase can be written as32:

where \(\Delta {v}_{{{\rm{o}}}}\) is peak slip velocity, μ the rigidity at the source region, and \(\zeta =\frac{{v}_{{{\rm{R}}}}}{{v}_{{{\rm{P}}}}}\sin \theta \) is the P-wave apparent Mach number32, with θ being the angle between the ray take-off direction and the normal to the circular fault. The term including the apparent Mach number accounts for rupture directivity, depending on the receiver view angle and the rupture to wave velocity ratio. In Eq. 1, the relation between the peak slip velocity and dynamic stress drop is inferred from the dynamic models of a propagating shear crack by Kostrov33 and Dahlen34. Averaging over θ, Eq. 1 changes to:

where the rupture velocity factor

grows as a power of \({v}_{{{\rm{R}}}}\). According to Eq. 2, both the rupture velocity and/or dynamic stress drop control the rise of the radiated P pulse displacement and therefore its initial slope.

An example of the effect of a varying rupture velocity with magnitude on LPDT curves and slope by assuming a Sato and Hirasawa25 kinematic source model of a circular shear crack is presented in the Supplementary Material (Text S1 and Fig. S4). Synthetic tests support the idea that a decreasing value of rupture velocity with magnitude could be responsible for the observed decrease in the initial slope of P-wave displacement.

We note that the theoretical duration of far-field displacement waveforms from uniform rupture speed, circular rupture, is indeed model-independent, and it only uses the Fraunhofer approximation to evaluate the directivity modulation of the azimuthal varying pulse duration. Even considering a decreasing rupture velocity with magnitude for the entire duration of the process, the final pulse duration would still obey a self-similar, constant stress-drop scaling with magnitude (Fig. S6 of the Supplementary Material). In a more realistic rupture model accounting for the breakout phase, due to the very limited duration of this unstable acceleration process (of the order of 1–2 s for M 7–8) as compared to the entire process (tens of seconds for the same magnitude range), no significant effects on the total duration would be produced. In this view, the observed differences between small and large events during the very early stage of the rupture process could be reconciled with the long-time scaling of earthquake source parameters.

This idea of a variable rupture velocity with magnitude has been recently explored by a theoretical study, showing that rupture acceleration during the breakout phase inversely scales with the size of the initial breakout patch and therefore with the size of the event, being larger for small earthquakes and smaller for large events35. Nielsen35 provides a statistical interpretation of the result: for a small initial breakout area, the initial moment rate grows relatively faster, reducing the probability of a large magnitude earthquake. Conversely, a slower moment rate growth is associated with an extended break-out patch on a large fault segment and, therefore, to a larger probability of a large magnitude earthquake.

The result of the rupture front propagation solution is analytically derived from classic fracture mechanics and is also supported by laboratory experiments and numerical simulations. While the recent work of Nielsen35 provides a fundamental theoretical support of a proper causative model, empirical observations of a clear rupture velocity–magnitude dependence, especially during the very early stages of rupture, remain scarce. A comprehensive study of real earthquake data confirming this trend would greatly strengthen the case, though such an effort is challenging due to observational limitations at rupture onset. Future high-resolution observational studies—enabled by dense seismic arrays and advanced back-projection or early-time waveform analysis—could provide critical tests to corroborate this model and offer new insights into the dynamics of the breakout phase of the earthquake rupture. The dynamic modeling of source processes also represents a valid tool for simulating the mechanical conditions for fault activation, including the friction law, the critical slip value of the nucleation size, the rupture velocity, and the role of these parameters in controlling the final earthquake size. Complementary, laboratory experiments may provide direct measurement of the parameters involved in the generation and propagation of seismic ruptures, and the increasing availability of high-frequency records during laboratory micro-earthquake ruptures will pave the way for the future interpretation of natural, large-scale seismic processes36.

Relevant implications of the proposed model are also related to the rapid assessment of the earthquake size for Earthquake Early Warning Systems (EEWS), for which the possibility of discriminating a large event from a small one is crucial to provide a reliable prediction of the incoming ground shaking level, for the prompt activation of emergency procedures and real-time risk mitigation actions. While EEWS are already operational in several countries, their performance is inherently limited by the distribution of seismic stations and system latency, which may delay access to the very first portion of the P-wave. In this context, the approach we explore- based on the initial amplitude growth rate- could contribute to enhancing the existing frameworks by providing a fast proxy for earthquake size. This could be achieved either using direct amplitude measurement or passing through the computation and modeling of amplitude vs. time curves. The challenges of real-time analysis are mainly related to (a) the automatic identification of the plateau level (and related time) of the curves and (b) the robust, early estimation of the earthquake size and its uncertainty, as resulting from the observed scatter of the curves in Fig. 4. One possibility toward the real-time application could be to adopt an evolutionary strategy, where updated estimates of magnitude (and related uncertainty) are obtained from slope measurements in progressively expanded P-wave time windows. A simple threshold-based warning system, accounting for the observed variability of the initial slope measurement, would allow for a fast discrimination of small/large events within very short time windows (ideally <1 s), opening up new perspectives for the practical applications of EEWS.

Methods

The initial dataset consists of 200 earthquakes from worldwide locations (see Fig. 1). The events span a time ranging between 2003 and 2023 and moment magnitude ranging between 4 and 9 (see Supplementary Material, Table S1). Waveforms were downloaded from all available catalogs, both at the European and global scales. Specifically, small-to-moderate Japanese events (in the range M 4–7) were downloaded from the Japanese Strong-motion Seismograph Networks (https://www.kyoshin.bosai.go.jp/kyoshin/download/); small-to-moderate (M 4–7) European and Californian events were downloaded from the European-Mediterranean Seismological Centre (http://www.seismicportal.eu/fdsnws/event/1/) and from the Northern California Earthquake Data Center (https://service.ncedc.org/ncedcws/eventdata/1/). Finally, for larger magnitude events (M ≥ 7) we downloaded the available records from the IRIS worldwide archive (http://service.iris.edu/fdsnws/dataselect/1/), selecting earthquakes that occurred between January 2010 and December 2023.

The resulting dataset ensured a sufficiently high number of events and waveform records (about 7000) distributed worldwide, with an adequate and balanced coverage of different magnitude ranges. At the same time, the dataset size remained manageable for the detailed analysis we performed, including manual picking of waveforms, which would not have been feasible at this stage with a larger dataset.

The waveforms are recorded either from velocimeter networks or accelerometer networks, depending on data availability. For each earthquake having a number of records higher than two, we select those records within a 25 km wide circular crown that includes the closest station to event epicenter. Depending on the available recording sensor (velocimeter or accelerometer) (see Fig. 1) we perform a single or double integration of signal, respectively, to get displacement and we finally apply a high-pass Butterworth filter with cut-off frequency of 0.075 Hz to remove possible baseline effects. We compute the logarithm of the peak of the absolute displacement starting from the P-arrival time at the station.

We average the obtained LPDT curves by stations (dashed lines in Fig. 2). The average is performed on the logarithm of P-peak of displacemet (LPD) at each time step and the starting point of the single station curve corresponds to the P-wave arrival at the station. Finally, we get the final LPDT curve (thick line in Fig. 2) whose points have a standard deviation coming from the average we performed on single station curves. The shape of the LPDT curves is characterized by an initial increase followed by the bending towards the Plateau Level.

We perform a fit of the real LPDT curve with an exponential function of the form:

where \({{{\rm{LPDT}}}}_{0}\) and \({{{\rm{LPDT}}}}_{{{\rm{end}}}}\) are the first and the last point of the curve respectively, \({{\rm{t}}}_{1}\) is a fit parameter that simply allows the function to bend towards the plateau level. The fitting procedure is used to avoid numerical noise caused by the discontinuity of real curves. As explained in the following the fitting curve is just used to select the time window for the slope measurement on the original LPDT curve.

For each curve, we then compute the curvature as

where \({y}^{{\prime} }\) and \({y}^{{{{\prime} }}{{{\prime} }}}\) are the numerical first and second derivative of the interpolated LPDT curve. The curvature allows to quantify how much the curve deviates from a linear behavior, with minimum curvature values correspondig to the linear sections of the LPDT curves, and reaching the maximum curvature value at the time of the plateau level.(see panel B and C of Fig. 2)

Figure S2 of the Supplementary Material shows an example of curvature computation.

Finally, we evaluate the slope along the original LPDT curve as:

where tMIN is fixed at 0.05 s after P-wave arrival and \({{\rm{t}}}_{{{\rm{HALF}}}}\), corresponds to half of the time where the maximum of the curvature is reached. The choice of the starting point for the slope evaluation is done to account for errors in affect the manual picking of waveforms. The choice for selecting the half-time between the first-P arrival and the LPDT plateau time is arbitrary, since any shortest interval could be used, provided that a sufficient number of data points are considered for the linear fitting of the initial slope. In Fig. 3c, we show the results of the slope measurement using a shorter time window. The slope is obtained from the line that crosses the LPDT between tMIN and tHALF, using a weighted least-square fit which takes into account the standard deviation on each point of the averaged LPDT.

Data availability

The waveform data used for the study are available at https://www.kyoshin.bosai.go.jp/kyoshin/download/ for Japanese earthquakes; at http://www.seismicportal.eu/fdsnws/event/1/ for European earthquakes; at https://service.ncedc.org/ncedcws/eventdata/1/ for Californian earthquakes and at http://service.iris.edu/fdsnws/dataselect/1/ for worldwide big earthquakes with free access.

Code availability

Data analysis is performed using Python version 3.9.13 (details at https://www.python.org). The same software was used to produce Figs. 2, 3, and 4. Figure 1 was prepared using PyGMT (details at https://www.pygmt.org/latest/).

References

Latour, S., Schubnel, A., Nielsen, S., Madariaga, R. & Vinciguerra, S. Characterization of nucleation during laboratory earthquakes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5064–5069 (2013).

Ampuero, J. -P., Vilotte, J. -P. & Sánchez-Sesma, F. J. Nucleation of rupture under slip dependent friction law: simple models of fault zone. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 107, ESE 2-1–ESE 2-19 (2002).

Dascalu, C., Ionescu, I. R. & Campillo, M. Fault finiteness and initiation of dynamic shear instability. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 177, 163–176 (2000).

Nielsen, S., Taddeucci, J. & Vinciguerra, S. Experimental observation of stick-slip instability fronts. Geophys. J. Int. 180, 697–702 (2010).

Wesnousky, S. G. Predicting the endpoints of earthquake ruptures. Nature 444, 358–360 (2006).

Ishihara, Y., Fukao, Y., Yamada, I. & Aoki, H. Rising slope of moment rate functions: the 1989 earthquakes off east coast of Honshu. Geophys. Res. Lett. 19, 873–876 (1992).

Abercrombie, R. & Mori, J. Local observations of the onset of a large earthquake: 28 June 1992 Landers, California. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 84, 725–734 (1994).

Ellsworth, W. L. & Beroza, G. C. Seismic evidence for an earthquake nucleation phase. Science 268, 851–855 (1995).

Mori, J. & Kanamori, H. Initial rupture of earthquakes in the 1995 Ridgecrest, California sequence. Geophys. Res. Lett. 23, 2437–2440 (1996).

Olson, E. L. & Allen, R. M. The deterministic nature of earthquake rupture. Nature 438, 212–215 (2005).

Zollo, A., Lancieri, M. & Nielsen, S. Earthquake magnitude estimation from peak amplitudes of very early seismic signals on strong motion records. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL027795 (2006).

Colombelli, S., Festa, G. & Zollo, A. Early rupture signals predict the final earthquake size. Geophys. J. Int. 223, 692–706 (2020).

Meier, M.-A., Ampuero, J. P. & Heaton, T. H. The hidden simplicity of subduction megathrust earthquakes. Science 357, 1277–1281 (2017).

Aagaard, B. T. & Heaton, T. H. Constraining fault constitutive behavior with slip and stress heterogeneity. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004793 (2008).

Meier, M., Heaton, T. & Clinton, J. Evidence for universal earthquake rupture initiation behavior. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 7991–7996 (2016).

Scherbaum, F. & Bouin, M.-P. FIR filter effects and nucleation phases. Geophys. J. Int. 130, 661–668 (1997).

Trugman, D. T., Page, M. T., Minson, S. E. & Cochran, E. S. Peak ground displacement saturates exactly when expected: implications for earthquake early warning. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 124, 4642–4653 (2019).

Beroza, G. C. & Ellsworth, W. L. Properties of the seismic nucleation phase. Tectonophysics 261, 209–227 (1996).

Iio, Y. Observations of the slow initial phase generated by microearthquakes: implications for earthquake nucleation and propagation. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 100, 15333–15349 (1995).

Rice, J. R. Elastic wave emission from damage processes. J. Nondestr. Eval. 1, 215–224 (1980).

Colombelli, S., Zollo, A., Festa, G. & Picozzi, M. Evidence for a difference in rupture initiation between small and large earthquakes. Nat. Commun. 5, 3958 (2014).

Melgar, D. & Hayes, G. P. Characterizing large earthquakes before rupture is complete. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav2032 (2019).

Meier, M.-A., Ampuero, J.-P., Cochran, E. & Page, M. Apparent earthquake rupture predictability. Geophys. J. Int. 225, 657–663 (2021).

Duputel, Z., Tsai, V. C., Rivera, L. & Kanamori, H. Using centroid time-delays to characterize source durations and identify earthquakes with unique characteristics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 374, 92–100 (2013).

Sato, T. & Hirasawa, T. Body wave spectra from propagating shear cracks. J. Phys. Earth 21, 415–431 (1973).

Abercrombie, R. E. Earthquake source scaling relationships from −1 to 5 M L using seismograms recorded at 2.5-km depth. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 100, 24015–24036 (1995).

Allmann, B. P. & Shearer, P. M. Global variations of stress drop for moderate to large earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JB005821 (2009).

Ampuero, J. & Rubin, A. M. Earthquake nucleation on rate and state faults – aging and slip laws. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JB005082 (2008).

Aki, K. & Richards, P. G. Quantitative Seismology (University Science Books, 2009).

Bouchon, M. et al. How fast is rupture during an earthquake? New insights from the 1999 Turkey Earthquakes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 2723–2726 (2001).

Andrews, D. J. Rupture velocity of plane strain shear cracks. J. Geophys. Res. 81, 5679–5687 (1976).

Boatwright, J. A spectral theory for circular seismic sources; simple estimates of source dimension, dynamic stress drop, and radiated seismic energy. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 70, 1–27 (1980).

Kostrov, B. V. Selfsimilar problems of propagation of shear cracks. J. Appl. Math. Mech. 28, 1077–1087 (1964).

Dahlen, F. A. On the ratio of P-wave to S-wave corner frequencies for shallow earthquake sources. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 64, 1159–1180 (1974).

Nielsen, S. Earthquakes big and small: same physics, different boundary conditions. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.00544 (2024).

Acosta, M., Passelègue, F. X., Schubnel, A., Madariaga, R. & Violay, M. Can precursory moment release scale with earthquake magnitude? A view from the laboratory. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 12927–12937 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, through the project FORESEEING (GA 101164646), by the EU through the project GOBEYOND (GA 101121135 - HORIZON-CL3-2022-DRS-01), and by the “Multi-Risk sciEnce for resilienT commUnities undeR a changiNg climate” (RETURN) project, funded by the European Union’s NextGenerationEU and the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP; Code PE0000005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.L.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. S.C.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. A.Z.: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. A.Z. is the corresponding author and the supervisor of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Binhao Wang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Sylvain Barbot, Joe Aslin Alireza Bahadori, and Aliénor Lavergne. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Longobardi, V., Colombelli, S. & Zollo, A. The deterministic behaviour of earthquake rupture beginning. Commun Earth Environ 6, 883 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02814-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02814-z