Abstract

Biodiversity hotspots often coincide with regions along subduction zones where tectonic activity continuously make and break geographic connections promoting biological diversification and speciation. A puzzling biodiversity hotspot is the northern Caribbean islands that contain endemic terrestrial and freshwater biotas mainly evolved from South American colonizers that dispersed during the Cenozoic. However, tectonic reconstructions have always assumed a mostly inactive and coherent eastern Caribbean plate, such that migration routes must either have been overwater, or through an inner-plate land bridge. Nevertheless, recent studies revealed that the northeastern Caribbean region underwent tectonically induced uplift, subsidence and large-scale block rotations questioning the assumed plate coherency. Here we present a plate reconstruction including these novel constraints and reveals how tectonic and volcanic activity along the Lesser Antilles subduction zone have established a transient land corridor connecting South America and the Greater Antilles from ~45 to 25 Ma ago offering a new avenue to explain Caribbean biotic interchanges and diversification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

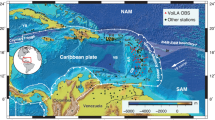

Biodiversity hotspots are characterized by rich and endemic fauna and flora and are mostly located in regions where plate tectonic processes have induced rapid geographic and environmental change in the past tens of millions of years1,2. The distribution of biodiversity is thus thought to be partly shaped by geologically induced physiographic changes at the Earth’s surface3,4. Subduction zones are especially prone to such changes, induced by geological processes such as volcanism5, tectonic deformation forming mountain belts or marine basins6, and large-scale, low amplitude uplift or subsidence driven by deep mantle flow known as dynamic topography7. It is thus no surprise that biodiversity hotspots are often found in regions associated with subduction (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). The Greater and Northern Lesser Antilles islands of the northern Caribbean region are located along former and active subduction zones, and host such a biodiversity hotspot1 (Fig. 1). Most of its terrestrial and freshwater biota originated from South American colonizers8,9,10, despite that the region is separated from South America by a deep, >500 km wide, oceanic channel (Fig. 1). South American land mammals, amphibians, arachnids, reptiles, freshwater fish and plants11,12,13,14,15,16,17 colonized these islands during the Cenozoic and efficiently radiated by filling unoccupied ecological niches10,17. Most of the colonization times, estimated from molecular clocks and the fossil record, occurred during the Cenozoic, between ~60 and 10 million years ago. Despite these broad colonization intervals and error margins ranging from 30 to 50 million years, colonization events appear to cluster predominantly during the Eocene–Oligocene interval8,10,18.

PRVI Puerto Rico Virgin Island, NOLA Northern Lesser Antilles, SOLA Southern Lesser Antilles. Tectonic blocks color code: Caribbean (green); Central America (blue green); South America (purple); North America (orange), Coco-Nazca (light blue). The topographic basemap was extracted from the ETOPO 2022 (NOAA)71. A detailed list of tectonic blocks and fault names is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. The species represented correspond to the Eocene to Oligocene (ca. 45–25 Ma ago) South American colonizers. They include land mammals (i.e., Paralouatta marianae monkey, megalocnid sloths; chinchilloid caviomorphs), amphibians (i.e., Caribbean toads and treefrogs), reptiles (i.e., Plethodontid salamanders, Aristelliger geckos, Sphaerodactylus geckolets, Amphisbaena worm lizards, Celestinae lizards, Tropidophiidae tropes, Cyclura iguanas, Typhlopidae blind snakes), arachnids (i.e., Anttillatus); freshwater fishes (i.e., Poeciliidae, Cichlidae) and plants (i.e., Podocarpus conifers)10,12,13,14,72.

Surprisingly, however, there has so far not been evidence for strong tectonic deformation that could have made and broken land bridges between the northeastern Antilles Islands and South America. Ever since the plate tectonic revolution in the 1960s, the Caribbean Plate has been considered as a mostly coherent plate that moved eastward from a late Cretaceous position west of Colombia towards its modern position19. Even though detailed geological data of the Antilles islands have revealed episodes of tectonic shortening, extension, and rotations20,21,22,23,24, only E-W directed strike-slip motion localized along the northern and southern Caribbean plate boundaries was implemented in tectonic reconstructions25,26,27,28 and the eastern Caribbean plate’s overall rigidity remained the paradigm in interpreting its paleogeographic history8,10,18,29.

Under this paradigm, explaining the South American origin of the Caribbean biodiversity hotspot proved challenging, and include three options: (i) late Cretaceous vicariance30,31, (ii) long-distance overwater dispersal throughout the Cenozoic10,14,17,32, or (iii) overland dispersal via a late Eocene-early Oligocene land bridge or stepping-stone islands, postulated to coincide with the Aves ridge, an eastern Caribbean submarine high now resting at 1 km depth- that must then have risen and sunk vertically without a known tectonic cause- known as the GAARlandia hypothesis8,18.

Interestingly, recent detailed geological studies in the northeastern Caribbean islands, and geophysical studies of the intervening seaways and basins have demonstrated much stronger physiographic and tectonic changes than previously known for the northeastern Caribbean Plate33,34,35,36. These studies revealed that the islands from Puerto Rico to Antigua underwent uplift and (partial) emergence during the middle to late Eocene (~45–35 Ma) as a result of shortening and incipient volcanism, forming the GrANoLA (Greater Antilles Northern Lesser Antilles)-land34. Since the late Oligocene (~25 Ma), the GrANoLA-land broke into the modern archipelago in response to regional tectonic extension33,35,37. In the southern Antilles region, recent geophysical research also revealed that the Grenada–Tobago basin opened from 48 to 38 Ma in response to slab roll-back triggering NW-SE directed extension38. The tectonic deformation and volcanic evolution of the eastern Caribbean region is geodynamically interpreted as resulting from the onset of westward subduction below the western Caribbean margin39,40 that occurred during a marked change in relative motion between the Caribbean and North and South American plates around 50 Ma from NE to E-ward25,26,40. In addition, the northeastern Caribbean plate margin obliquely overrode the buoyant Bahamas bank23,41,42 and underthrusted the northwestern South American margin27,28. These studies revealed tectonic causes for uplift, emergence, subsidence, and submergence that coincide with Cenozoic biological colonization intervals8,10,17,18. The uplift of GrANoLA-land could thus have played a paleogeographic role34, but in its current position within the Caribbean Plate, it would still have been 500 km away from South America at that time. However, paleomagnetic data recently revealed that the GrANoLA tectonic blocks (i.e., the Puerto Rico Virgin Islands and the Northern Lesser Antilles blocks) experienced a major and consistent counterclockwise rotation of 45° and perhaps up to 70° since the late Eocene36. This rotation was previously unknown and further challenges the rigid or coherent Caribbean plate paradigm. These large, regional rotations require that GraNoLA-land must have been part of a lithospheric block that has moved over distances of hundreds of kilometers relative to the Caribbean plate interior and South America, and may be relevant in interpreting the origin and evolution of the Caribbean biodiversity hotspot biota36.

In this study, we provide an updated kinematic reconstruction of the eastern Caribbean region since 50 Ma that takes the recent evidence for intraplate tectonic deformation into account, and that aims to reconstruct the paleo-position of GrANoLA-land relative to the Caribbean plate interior as well as South America. We subsequently use this reconstruction to assess the role that deformation may have played in forming and destroying dispersal pathways and in the shaping of Caribbean biogeography.

Result and discussion

Eastern Caribbean plate tectonics since 50 Ma

The implemented key new constraint for the tectonic reconstruction of the eastern Caribbean region is the paleomagnetically documented counterclockwise rotation of GrANoLA blocks that places it in a N-S orientation in the Eocene36 (Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 2). This may be reconstructed in two ways36: either with oroclinal bending and rotation around a pole located around Antigua, which would require unrecorded hundreds of km of N-S convergence between Puerto Rico and the Caribbean plate interior, and place the GrANoLA blocks over the Bahamas Platform, which is not feasible (Supplementary Fig. 3). Or, alternatively, with the GrANoLA blocks forming a forearc and arc sliver that moved around the northeastern Caribbean plate corner, which is the preferred scenario that we reconstructed here (Fig. 2, Supplementary Movie 1, Supplementary Files 1, 2, Supplementary Fig. 3). This brings the GrANoLA blocks as far south as the modern position of Grenada around 50–40 Ma, immediately adjacent to the South American continent (Fig. 2D). In this scenario, the GraNoLA blocks moved away from the South American continent until 20 Ma while rotating counterclockwise as a sliver that moved slower eastwards relative to North America than the Caribbean plate interior around the Montserrat-Harvers Fault Zone (Fig. 2B, C). The position and motion of the GrANoLA blocks differ from previous tectonic models25,26,27,28. In the absence of paleomagnetic-derived rotation estimates, these reconstructions implemented an eastward-directed motion of the GrANoLA blocks, tacking Puerto Rico to the south of Southern Hispaniola, 500 km away from the subduction trench. This was problematic as it would imply the presence of an unspotted left-lateral strike-slip fault and fail to explain the presence of Eocene arc rocks in Puerto Rico43. Moreover, our preferred scenario restores the Caribbean Plate interior ~500 km farther west around 50 Ma than in previous reconstructions and invokes a ~15° clockwise rotation to avoid overlap with the Chortis Block, consistently with previous reconstructions of Montes et al.27. This straightforwardly solves an overlap problem of the eastern Caribbean Plate with South America that remained a challenge in previous reconstructions (Fig. 2).

After 40 Ma, the eastward motion and clockwise rotation of the Caribbean Plate led to lengthening of the Caribbean-South American oblique-subduction plate boundary, at which the Barbados and the northern Venezuela accretionary prism started forming44 (Fig. 2C, D). The reconstructed clockwise rotation of the eastern Caribbean Plate generates an E-W, trench-perpendicular opening of the Grenada–Tobago basin from 48 to 38 Ma38. Venezuelan and Leeward Antilles blocks in the reconstruction underwent 90° of clockwise rotation, consistent with paleomagnetic evidence (Supplementary Table 2). As a result, the opening of the Grenada–Tobago basin is associated with a saloon door-style, opposite rotations of forearc and arc blocks, clockwise for the North Venezuela and Leeward Antilles blocks and counterclockwise for the GraNoLA blocks (Fig. 2C, D).

Around 20 Ma, the GrANoLA blocks approached their present-day position. From there, forearc sliver motion slowed down, and the eastward motion of the Caribbean plate relative to North and South America was accommodated by strike-slip motion on the Swan-Motagua-Oriente and Oca-San Sebastian-El Pilar fault system, forming the northern and southern Caribbean plate boundaries, respectively (Figs. 2A, B). From 20 Ma onward, the indentation of the Bahamas Bank on the northern Caribbean plate, combined with transpression along the curved Puerto Rico trench, induced shortening and uplift in Hispaniola20 (Fig. 2B) and left-lateral strike-slip motion on the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden Fault42.

Potential geodynamic drivers

The reconstructed sliver motions of the GrANoLa and Northern Venezuela–Leeward Antilles arc and forearc blocks, concurrent with the opening of the Grenada-Tobago basin in a back-arc position, the increase in trench length, and the eastward retreat of the southeastern Caribbean trench in a mantle reference frame45 (Supplementary Movie 1, Supplementary Files 1, 2, Fig. 2), suggest that slab roll-back played a significant role in the tectonic evolution of the eastern Caribbean plate. This phase of slab roll-back must have occurred in the first ~10 Ma after the initiation of the Lesser Antilles subduction zone (Fig. 2C, D): Before 50 Ma, Caribbean plate motion relative to the Americas was NE-ward, accommodated by SW-ward subduction below the Greater Antilles25,26. The subduction trench at 50 Ma extended from Cuba to the Virgin Islands (Fig. 2D), also shown by the occurrence of Cretaceous to early Eocene arc-related rocks on these islands43. During this time, the eastern Caribbean plate - or Lesser Antilles - margin was dominantly a transform plate boundary (Fig. 2D). However, due to the ~50 Ma change to eastward motion of the Caribbean Plate, subduction propagated southward and this N-S trending transform became a subduction zone (Fig. 2C). Our reconstruction shows that the roll-back of the Lesser Antilles slab is mostly concentrated in the period of opening of the Grenada–Tobago basin (ca. 48–38 Ma) and occurred during the first hundreds of kilometers of subduction below the eastern Caribbean plate, during which period the slab was still only located within the upper mantle. We hypothesize that rapid roll-back during the late Eocene, and the opening of the Grenada–Tobago basin, occurred as long as both poloidal upper mantle flow (below the slab) and toroidal flow (around the slab) were possible. Once the slab reached the base of the upper mantle around 660 km, poloidal flow was impeded and roll-back ceased, after which the Caribbean plate became nearly mantle-stationary, and relative motion with the Americas was accommodated by the westward advance of the Americas. During the Eocene roll-back phase, the relative motion between the eastern Caribbean plate margin and the buoyant and rigid Bahamas Bank indenter and the South American promontory was highest. We infer that the contrast between friction in the north and south with roll-back in the center may have caused the Venezuela and GrANoLa double saloon door-style sliver motion, back-arc opening, and contractional tectonics and uplift in the arc and forearc (Fig. 2D). Analogous tectonic histories may be found in the western Mediterranean region, where roll-back of the Calabrian and Gibraltar slabs led to the opening back-arc basins accompanied by opposite rotations of forearc accretionary units on Sicily and the southern Apennines, and in the Betic and Rif orogens, respectively46,47,48. These sliver motions and contractional tectonics continued until the late Oligocene (ca. 25 Ma) but progressively slowed down once roll-back ceased driven by ongoing relative Caribbean-Americas motion (Fig. 2C). Since approximately 25 Ma, the westward migration of the Bahamas has placed the GrANoLa region beyond its zone of influence, potentially participating to the regional extensional regime and associated subsidence phase33,37 (Fig. 2A, B).

Eastern Caribbean volcanic arc evolution

In the reconstructed configuration prior to 50 Ma, the Aves Ridge was behind, and at a high angle to the Greater Antilles arc (Fig. 2D) and situated approximately 500 km west of the eastern Caribbean plate boundary. Even though this boundary was likely a subduction zone in the late Cretaceous25,26, this distance is much larger than for typical arcs. Unambiguous record of Cretaceous volcanic arc rocks in the Aves ridge consists of a limited number of dredged samples restricted to its southernmost (i.e., Los Hermanos spur) and northernmost (i.e., Saba bank) parts49,50,51 (Fig. 4) (Supplementary Note 1). The 50 Ma back-arc position of the Aves Ridge, combined with the limited and spatially restricted Cretaceous arc samples, may challenge the long-standing interpretation of the entire Aves Ridge as a Cretaceous volcanic arc51,52. The thick crust of the central Aves Ridge may instead consist of Caribbean Large Igneous Province related rocks51 similarly to the ~20 km thick Beata Ridge53 located on the central Caribbean Plate (Fig. 1). The Cretaceous arc volcanic rocks found on the northern and southern extremities of the ridge may instead be part of the ~E-W trending arcs of the Northern and Southern Caribbean plate (i.e., Greater Antilles and Leeward Antilles arcs), and may even have been tectonically juxtaposed against the central Aves ridge.

After 50 Ma, the Lesser Antilles subduction initiation, coupled with interaction with the buoyant Bahamas Bank to the north, likely triggered a reorganization of the eastern Caribbean arc systems40. This reconfiguration is recorded by the progressive cessation of arc magmatism along the Greater Antilles, with a southeastward younging trend in the ages of arc-related rocks40,43,54, and by the magmatic flare-up in the northern Lesser Antilles segment36,51. Our tectonic scenario also accounts for the absence of straightforward evidence of Eocene arc rocks in the southern Lesser Antilles36,55 as this region was located in a back-arc position, west of the northern Lesser Antilles arc and forearc blocks during the Eocene (Fig. 2C, D). The southern Lesser Antilles reached the subduction front during the Oligocene, following the double saloon door opening of the Grenada–Tobago Basin, consistent with the age of arc-related rocks in the southern Lesser Antilles islands55.

Cenozoic Caribbean paleogeography

Our tectonic reconstruction with a mobile eastern Caribbean arc and forearc allows re-evaluating the paleogeography that existed during the Cenozoic biological dispersal of South American organisms into the Caribbean. 50 Ma ago, the GrANoLA blocks were in contact with South America’s Maracaibo promontory (Fig. 2D), but at that time, the Eastern Caribbean region was mainly submarine8,33. Erosional hiatuses and subaerial volcanic flows in the northern Caribbean islands (Puerto Rico, St Barthélemy, St Martin, Anguilla, Antigua) and regional unconformities recognized in deep drillings and seismic profiles of adjacent basins33,34 indicate that potentially interconnected land masses emerged in the GrANoLA region, from Puerto Rico to Antigua, during the middle Eocene (~45 Ma ago), synchronous with the emergence of land in Cuba and Hispaniola8,18. We interpret this phase of uplift and emersion as resulting from the combined effects of contractional tectonics and of arc magmatism flare-up in the northern Lesser Antilles, both driven by subduction zone processes (see previous section). Over time, the GrANoLA-land(s) moved away from South America due to sliver motion (Figs. 2 and 3B). Nevertheless, siliciclastic sediments in blocks now thrust upon northern Venezuela, as well as in the Barbados accretionary prism show that during the late Eocene emergent land must have existed in the southeast Caribbean corner forming the so-called Northern Venezuela land, located between GrANoLa and South America34,44 (Fig. 3B). The GrANoLA and Northern Venezuela land masses may thus have formed an Eastern Caribbean transient land bridge between South America and the Greater Antilles that most probably consisted of a chain of large islands separated by narrow and very shallow-water sea corridors. These lands may thus have connected or disconnected in response to high-frequency sea-level fluctuation or local tectonic variations (Fig. 3B). An additional forcing may have come from the global 50 to 70 m sea level drop associated with the onset of Antarctic glaciation around 34 Ma56,57, potentially extending the land surface and fully connecting land masses. From the late Oligocene onward (~25 Ma), the GrANoLA and northern Venezuela lands split apart due to ongoing sliver motion, dismembering the Eastern Caribbean transient land bridge (Figs. 2 and 3A). In addition, the GrANoLA-land(s) were tectonically broke up by trench-parallel extension during a late Oligocene to Miocene regional subsidence and submersion event recorded by shallow-water marine limestones recognized on GrANoLA remnant islands (i.e., Puerto Rico, St Barthélemy, St Martin, Anguilla, Antigua) and on seismic lines and deep-water sediments dredges covering previously emergent areas in the surrounding northern Caribbean basins33,37 (Fig. 3A).

A Late Oligocene—early Miocene paleogeography; B the late Eocene—early Oligocene paleogeography. The maps are built upon the kinematic scenarios at 20 (Fig. 2B) and 35 (Fig. 2C) million years, respectively. The light green areas indicate regions where geological data are sparse, and where either the presence of land or very shallow seaways is plausible. The paleogeography of the Lesser Antilles and the Eastern Greater Antilles is adapted from Cornée et al.33. For Central America, the Caribbean plate interior, the Greater Antilles, northwestern South America, the Leeward Antilles, and the Aves Ridge, we combined the paleogeographic maps of Iturralde-Vinent and MacPhee8,18 and Ali and Hedges17 and of Pindell et al.25 for northeastern South America. The list of South American colonizer species is detailed in Fig. 1.

The possibility of a transient land bridge in the mobile easternmost Caribbean arc and forearc slivers, does not preclude that also the Aves Ridge formed a land bridge or stepping-stone islands as postulated by Iturralde-Vinent & McPhee8,18 nor does it exclude overwater dispersal10,17 (Fig. 3B). In our tectonic configuration the Leeward Antilles, la Blanquilla, Saba bank and adjacent basins, erosional hiatuses indicate the presence of land from the late Eocene to the Oligocene aligning with the (potentially) emerged Aves Ridge58,59,60 (Fig. 3B).

Impact on Caribbean biotas evolution

Our reconstructed paleogeography offers a novel insight into dispersal pathways of South American biota into the Caribbean realm. We identified a roughly 20 Ma-long window of opportunity between 45 and 25 Ma for overland dispersal via a land-supported connection (i.e., transient island-continent land bridge or stepping-stone islands) in the Eastern Caribbean region. This new timeframe and geographical position for a historical South American-Caribbean land connection could help to explain the apparent Eocene to Oligocene clustering of colonization times inferred in the literature8,10,17.

While a full land connection would have allowed the dispersal of South American biota, both the current Caribbean biota and its late Quaternary fossil record lack several groups of extant and extinct South American vertebrates. Moreover, the colonization timings are wider than the Eocene and Oligocene only (i.e., 60–10 Ma) and the number of taxa dispersing into the Caribbean from continental America is significantly less than during the Great American Biotic Interchange, despite a similar time length of opportunity for colonization61. These observations suggest that either Caribbean biota was more strongly filtered by geographic or ecological filters (i.e., the very shallow-water seaways between large islands reducing the number of taxa that dispersed into the Antilles), that the transient and ephemeral nature of the land connections to the Caribbean were not effective pathways for many organisms, or that a larger number of groups dispersed but went extinct before the late Quaternary62.

Future characterization of the habitat conditions in this updated paleogeographic configuration will permit biologists to infer dispersal routes and mechanisms for taxa with specific physiological tolerances. For example, terrestrial deposits with freshwater lakes prior to 30 Myr have been found in Antigua36, suggesting that freshwater connections within GrANoLA-land could have facilitated migrations of freshwater fishes14. The subsequent Miocene separation of GrANoLA-land into smaller islands with an increasing distance from South America owing to forearc sliver motion could have triggered inter-island diversification via allopatric speciation, rendering many single-island endemics in Puerto Rico and in the northern Lesser Antilles63.

Our novel reconstruction has broader implications for the field of historical biogeographic modeling, which uses spatial and temporal characteristics of past and current island connections with the mainland to infer the ancestral areas and thereby dispersal of any taxonomic group64. This reconstruction provides solid geological evidence for a time window, mechanism of formation and destruction (i.e., tectonics and volcanism) of transient land pathways that could have served as biological dispersal corridors. We thus provide a synthesis of independent evidence that will contribute to the biogeographical discussion around long-distance oceanic versus island hopping, or land bridge-facilitated colonization of insular biota.

Our study demonstrates how, also in the Caribbean region, tectonic deformation and volcanic activity associated with subduction zone processes led to the rapid formation and destruction of geographic features, which could have in turn influenced the assembly and evolution of modern biodiversity. Subduction zone processes cause the most rapid horizontal and vertical motions of land masses on Earth. As a result, land connections for biological dispersal appear and disappear frequently, and populations of species may become isolated or (re-)connected. A better understanding of biodiversity assembly and evolution may thus be achieved by bringing together the (paleo)biological community, which reconstructs lineage divergence times and ancestral areas, and the geological community, which develops detailed paleogeographic reconstructions of regions with active and past subduction.

Methods

Our kinematic reconstruction (Supplementary Data 1 and 2, Supplementary Movie 1) is built with the GPlates reconstruction software65 and placed in the latest paleomagnetic reference frame66. Relative motions between the plates surrounding the Caribbean region use a North American-Africa-South America plate circuit and a North America-Africa-Antarctica-Pacific-Cocos-Nazca plate circuit, with rotation parameters as summarized in Vaes et al.66 (Supplementary Fig. 4). The eastward motion of the Caribbean plate relative to North America is reconstructed using the magnetic anomalies of the Cayman Trough67. Restoration of the northwestern Caribbean blocks (e.g., Cuba, Yucatan, Chortis, Nicaragua, Jamaica) and of Central America blocks follows Boschman et al.26, with updates for the Chortis Block as detailed in Molina-Garza et al.68 (Supplementary Fig. 5).

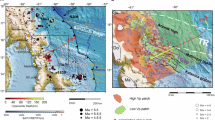

The rigid Caribbean plate interior, that comprises the Cretaceous Large Igneous Province (Fig. 4), is surrounded by deformed belts consisting of fault-bounded blocks of Caribbean plate lithosphere that comprise volcanic arc rocks and rock units accreted from downgoing plates (i.e., high pressure–low temperature metamorphic rocks, ophiolitic mélanges and accretionary prism sediments), both used as subduction proximity indicators (Fig. 4). We divide these into undeformable polygons (Supplementary Fig. 5), increasing blocks subdivision compared to previous reconstructions, using fault locations based on mapping24, geodetic data69 and gravity gradients70.

This map outlines the specific lithologies used as subduction proximity indicators in the reconstruction (i.e., high-pressure rocks, ophiolitic mélanges, arc-related rocks, accretionary prism sediments) and was built according to the lithostratigraphic review presented in Supplementary Note 1 and adapted from Bouysse et al.24 and Hu et al.43. The Caribbean Large Igneous Province delimitation is from Mauffret and Leroy22.

In reality, these blocks may have undergone some internal deformation, but by reconstructing them as rigid units, the extensional or contractional nature of that internal deformation becomes visible via gaps or overlaps between blocks. We updated the reconstruction of Boschman et al.26 and redrew blocks where we found reason to infer previously unreconstructed relative motions (e.g., the Caribbean plate interior is split into two along the Beata Ridge). The motion of the block-bounding faults is constrained by (i) previously estimated timing and displacement of faults based on geological data (Supplementary Table 3), (ii) vertical axis rotations estimated from paleomagnetic data (Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 2), (iii) consistency of subduction proximity indicators and (iv) geometrical consistency of the kinematic model.

A detailed review of the Caribbean and northern South American lithologies and fault kinematics is presented in Supplementary Note 1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are provided in the Supplementary Information files. This includes all input files and reconstruction models (Supplementary Data 1 and 2) used in the GPlates software to reproduce the modeling results. No additional datasets were used or generated outside those provided.

References

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., Da Fonseca, G. A. & Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858 (2000).

Pellissier, L., Heine, C., Rosauer, D. F. & Albouy, C. Are global hotspots of endemic richness shaped by plate tectonics?. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 123, 247–261 (2018).

Ota, H. Geographic patterns of endemism and speciation in amphibians and reptiles of the Ryukyu Archipelago, Japan, with special reference to their paleogeographical implications. Res. Popul. Ecol. 40, 189–204 (1998).

Skeels, A. et al. Paleoenvironments shaped the exchange of terrestrial vertebrates across Wallace’s Line. Science 381, 86–92 (2023).

Gabrielse, H. et al. Cretaceous and Cenozoic dextral orogen-parallel displacements, magmatism, and paleogeography, north-central Canadian Cordillera. Geol. Assoc. Can. Spec. Pap. 46, 255–276 (2006).

McCaffrey, R. et al. Strain partitioning during oblique plate convergence in northern Sumatra: Geodetic and seismologic constraints and numerical modeling. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 105, 28363–28376 (2000).

Flament, N., Gurnis, M. & Müller, R. D. A review of observations and models of dynamic topography. Lithosphere 5, 189–210 (2013).

Iturralde-Vinent, M.A. & MacPhee, R. D. Paleogeography of the Caribbean region: implications for Cenozoic biogeography. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 238, 1–95 (1999).

Antonelli, A. et al. Amazonia is the primary source of Neotropical biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 6034–6039 (2018).

Ali, J. R. & Hedges, S. B. Colonizing the Caribbean: new geological data and an updated land-vertebrate colonization record challenge the GAARlandia land-bridge hypothesis. J. Biogeogr. 48, 2699–2707 (2021).

Blackburn, D. C., Keeffe, R. M., Vallejo-Pareja, M. C. & Vélez-Juarbe, J. The earliest record of Caribbean frogs: a fossil coquí from Puerto Rico. Biol. Lett. 16, 20190947 (2020).

Roncal, J., Nieto-Blázquez, M. E., Cardona, A. & Bacon, C. D. Historical biogeography of Caribbean plants revises regional paleogeography. In Neotropical Diversification: Patterns and Processes. 521–546 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2020).

Cala-Riquelme, F., Wiencek, P., Florez-Daza, E., Binford, G. J. & Agnarsson, I. Island–to–island vicariance, founder–events and within–area speciation: the biogeographic history of the Antillattus Clade (Salticidae: Euophryini). Diversity 14, 224 (2022).

Massip-Veloso, Y., Hoagstrom, C. W., McMahan, C. D. & Matamoros, W. A. Biogeography of Greater Antillean freshwater fishes, with a review of competing hypotheses. Biol. Rev. 99, 901–927 (2024).

Zaher, H. et al. Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of the dwarf boas of the family Tropidophiidae (Serpentes: Alethinophidia). Syst. Biodivers. 22, 2319289 (2024).

Tejada, J. V. et al. Bayesian total-evidence dating revisits sloth phylogeny and biogeography: a cautionary tale on morphological clock analyses. Syst. Biol. 27-73, 125–139 (2024).

Ali, J. R. & Hedges, S. B. Paleogeography of the Aves Ridge and its potential role as a bio-colonization pathway linking South America and the Greater Antilles in the mid-Cenozoic. Earth Sci. Rev. 254, 104823 (2024).

Iturralde-Vinent, M.A. & MacPhee, R.D.E. New evidence for late Eocene-early Oligocene uplift of Aves Ridge and paleogeography of GAARlandia. Geol. Acta 21, 5 (2023).

Pindell, J. & Dewey, J. F. Permo-Triassic reconstruction of western Pangea and the evolution of the Gulf of Mexico/Caribbean region. Tectonics 1, 179–211 (1982).

Dolan, J. F., Mullins, H. T. & Wald, D. J. Active tectonics of the north-central Caribbean: Oblique collision, strain partitioning, and opposing subducted slabs (1998).

Speed, R. C., Smith-Horowitz, P. L., Perch-Nielsen, K. V. S. & Sanfilippo, A. B. Southern Lesser Antilles Arc Platform: Pre-Late Miocene Stratigraphy, Structure, and Tectonic Evolution Vol. 277 (Geological Society of America, 1993).

Mauffret, A. & Leroy, S. Seismic stratigraphy and structure of the Caribbean igneous province. Tectonophysics 283, 61–104 (1997).

Mann, P., Hippolyte, J.-C., Grindlay, N. R. & Abrams, L. J. Neotectonics of southern Puerto Rico and its offshore margin. In Active tectonics and seismic hazards of Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and offshore areas. (ed. Mann, P.) 173–214 (Geological Society of America, 2005).

Bouysse, P., Garcia-Reyes, A., de Lépinay, B. M., Ellouz-Zimmermann, N. & Pubellier, M. Structural Map of the Caribbean, scale 1: 4M (2020).

Pindell, J. L. & Kennan, L. Tectonic evolution of the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean and northern South America in the mantle reference frame: an update. Geol. Soc. 328, 1–55 (2009).

Boschman, L. M. et al. Kinematic reconstruction of the Caribbean region since the Early Jurassic. Earth Sci. Rev. 138, 102–136 (2014).

Montes, C. et al. Continental margin response to multiple arc-continent collisions: The northern Andes-Caribbean margin. Earth Sci. Rev. 198, 102903 (2019).

Escalona, A., Norton, I. O., Lawver, L. A. & Gahagan, L. Quantitative plate tectonic reconstructions of the Caribbean region from Jurassic to present. AAPG 239–263 https://doi.org/10.1306/13692247M1233849 (2021).

Escalona, A., Ahmad, S. S. & Watson, L. Quantitative plate tectonic reconstructions of the Caribbean region from Jurassic to present. AAPG 513–538 (2021).

Rosen, D. E. A vicariance model of Caribbean biogeography. Syst. Biol. 24, 431–464 (1975).

Felix, F. & Mejdalani, G. Phylogenetic analysis of the leafhopper genus Apogonalia (Insecta: Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) and comments on the biogeography of the Caribbean islands. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 163, 548–570 (2011).

Darlington, P. J. The origin of the fauna of the Greater Antilles, with discussion of dispersal of animals over water and through the air. Q. Rev. Biol. 13, 274–300 (1938).

Cornée, J.-J. et al. Lost islands in the northern Lesser Antilles: possible milestones in the Cenozoic dispersal of terrestrial organisms between South-America and the Greater Antilles. Earth Sci. Rev. 217, 103617 (2021).

Philippon, M. et al. Eocene intra-plate shortening responsible for the rise of a faunal pathway in the northeastern Caribbean realm. PLoS ONE 15, e0241000 (2020).

Roman, A. et al. Timing and magnitude of progressive exhumation and deformation associated with Eocene arc-continent collision in the NE Caribbean plate. Bulletin 133, 1256–1266 (2021).

Montheil, L. et al. Paleomagnetic rotations in the northeastern Caribbean region reveal major intraplate deformation since the Eocene. Tectonics 42, e2022TC007706 (2023a).

Boucard, M. et al. Paleogene V-Shaped Basins and Neogene Subsidence of the Northern Lesser Antilles Forearc. Tectonics 40, e2020TC006524 (2021).

Garrocq, C. et al. Genetic relations between the Aves Ridge and the Grenada back-arc basin, East Caribbean Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2020JB020466 (2021).

van Benthem, S. et al. Tectonic evolution and mantle structure of the Caribbean. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 118, 3019–3036 (2013).

Conrad, C. P. et al. Tectonic reorganization of the Caribbean plate system in the Paleogene driven by Farallon slab anchoring. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 25, e2024GC011499 (2024).

Lao-Davila, D. et al. Collisional zones in Puerto Rico and the Northern Caribbean. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 54, 1–19 (2014).

Wessels, R. et al. Polyphase tectonic history of the Southern Peninsula, Haiti: from folding-and-thrusting to transpressive strike-slip. Tectonophysics 751, 125–149 (2019).

Hu, J. et al. Review of geochronologic and geochemical data of the Greater Antilles volcanic arc and implications for the evolution of oceanic arcs. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 23, e2021GC010148 (2022).

Deville, E. et al. Tectonics and sedimentation interactions in the east Caribbean subduction zone: an overview from the Orinoco delta and the Barbados accretionary prism. Mar. Pet. Geol. 64, 76–103 (2015).

Doubrovine, P. V. et al. Absolute plate motions in a reference frame defined by moving hot spots in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian oceans. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 117, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JB009072 (2012).

Cifelli, F. et al. Tectonic evolution of arcuate mountain belts on top of a retreating subduction slab: The example of the Calabrian Arc. J. Geophys. Res. 112, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004848 (2007).

Cifelli, F. et al. New paleomagnetic data from Oligocene–upper Miocene sediments in the Rif chain (northern Morocco): insights on the Neogene tectonic evolution of the Gibraltar arc. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 113, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JB005271 (2008).

van Hinsbergen, D. J. J. et al. Orogenic architecture of the Mediterranean region and kinematic reconstruction of its tectonic evolution since the Triassic. Gondwana Res. 81, 79–229 (2020).

Fox, P. J. et al. The geology of the Caribbean crust: tertiary sediments, granitic and basic rocks from the Aves Ridge. Tectonophysics 12, 89–109 (1971).

Bouysse, P. et al. Aves Swell and northern Lesser Antilles Ridge: rock-dredging results from ARCANTE 3 cruise. In Proc. Symposium géodynamique des Caraïbes 65–76 (BRGM, 1985).

Neill, I. et al. Origin of the Aves Ridge and Dutch–Venezuelan Antilles: interaction of the Cretaceous ‘Great Arc’ and Caribbean–Colombian Oceanic Plateau?. J. Geol. Soc. 168, 333–348 (2011).

Burke, K. Tectonic evolution of the Caribbean. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 16, 201–230 (1988).

Dürkefälden, A. et al. Age and geochemistry of the Beata Ridge: Primary formation during the main phase (~ 89 Ma) of the Caribbean Large Igneous Province. Lithos 328, 69–87 (2019).

Bosc, D. et al. Tracking the Caribbean magmatic evolution: the British Virgin Islands as a transition between the Greater and Lesser Antilles arcs. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 26, e2024GC012057 (2025).

Allen, R. et al. The role of arc migration in the development of the Lesser Antilles: A new tectonic model for the Cenozoic evolution of the eastern Caribbean. Geology 47, 891–895 (2019).

Katz, M. E. et al. Stepwise transition from the Eocene greenhouse to the Oligocene icehouse. Nat. Geosci. 1, 329–334 (2008).

Miller, K. G. et al. Cenozoic sea-level and cryospheric evolution from deep-sea geochemical and continental margin records. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz1346 (2020).

MacSotay, O. & Feraza, L. Middle Eocene foreland sediments covered by late Oligocene foredeep turbidites on Margarita Island, Northeastern Venezuela. In Proc. Transactions of the 16th Caribbean Geological Conference. Caribbean Journal of Earth Science. Vol. 39, 105–111 (2005).

Clark, S. et al. Negligible convergence and lithospheric tearing along the Caribbean–South American plate boundary at 64 W. Tectonics 27, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008TC002328 (2008).

Escalona, A. & Mann, P. Tectonics, basin subsidence mechanisms, and paleogeography of the Caribbean-South American plate boundary zone. Mar. Pet. Geol. 28, 8–39 (2011).

Pelegrin, J. et al. El Gran Intercambio Biótico Americano: una revisión paleoambiental de evidencias aportadas por mamíferos y aves neotropicales. Ecosistemas 27, 5–17 (2018).

Vinola-Lopez, G. et al. A South American sebecid from the Miocene of Hispaniola documents the presence of apex predators in early West Indies ecosystems. Proc. B 292, 20242891 (2025).

Schneider, C. J. et al. Exploiting genomic resources in studies of speciation and adaptive radiation of lizards in the genus Anolis. Integr. Comp. Biol. 48, 520–526 (2008).

Matzke, N. J. et al. Founder-event speciation in BioGeoBEARS package dramatically improves likelihoods and alters parameter inference in Dispersal-Extinction-Cladogenesis (DEC) analyses. Front. Biogeogr. 4, 210 (2012).

Boyden, J. A. et al. Next-generation plate-tectonic reconstructions using GPlates. Geoinform. Cyberinfrastruct. Solid Earth Sci. 9, 5–114 (2011).

Vaes, B. et al. A global apparent polar wander path for the last 320 Ma calculated from site-level paleomagnetic data. Earth Sci. Rev. 245, 104547 (2023).

Leroy, S. et al. An alternative interpretation of the Cayman trough evolution from a reidentification of magnetic anomalies. Geophys. J. Int. 141, 539–557 (2000).

Molina-Garza, R. S. et al. Large-scale rotations of the Chortis Block (Honduras) at the southern termination of the Laramide flat slab. Tectonophysics 760, 36–57 (2019).

Symithe, S. et al. Current block motions and strain accumulation on active faults in the Caribbean. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 3748–3774 (2015).

Gómez-García, A. et al. 3-D modeling of vertical gravity gradients and the delimitation of tectonic boundaries: the Caribbean Oceanic Domain as a case study. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 5371–5393 (2019).

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. ETOPO 2022 15 arc-second global relief model. (NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, 2022).

Marivaux, L. et al. Early Oligocene chinchilloid caviomorphs from Puerto Rico and the initial rodent colonization of the West Indies. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20192806 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Leny Montheil: conceptualization, literature review, GPlates modeling, writing, formal analysis. Douwe J.J. van Hinsbergen: supervision, conceptualization, GPlates modeling, writing, formal analysis, funding acquisition. Mélody Philippon: supervision, conceptualization, literature review, writing, formal analysis, funding acquisition. Lydian Boschman: formal analysis, writing. Jean-Jacques Cornée: supervision, formal analysis, writing. Franck Audemard: formal analysis, literature review, writing. Richard Wessels: formal analysis, literature review, writing. Sylvie Leroy: formal analysis, writing. Julissa Roncal: formal analysis, writing. Philippe Münch: supervision, conceptualization, literature review, writing, formal analysis, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Manuel Iturralde-Vinent, Ethan M. Conrad, David Buchs, Lazaro W Viñola Lopez, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Alireza Bahadori and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Montheil, L., van Hinsbergen, D.J.J., Philippon, M. et al. Caribbean biodiversity shaped by subduction zone processes along the Lesser Antilles arch. Commun Earth Environ 6, 900 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02828-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02828-7