Abstract

Ocean temperature anomalies can drive anomalous atmospheric circulation, further impacting High Mountain Asia’s glacier dynamics, but this teleconnection remains underexplored. Here we present robust interannual and multidecadal relationships between glacier mass balance over the northeastern Tibetan Plateau and the North Atlantic sea surface temperature anomalies, after removing anthropogenic warming trends. The annual sea surface temperature tripole pattern explains 33.6% of the interannual glacier mass variability, mediated by the atmospheric wave train. On multi-decadal timescales, the average glacier mass loss of the northeastern Tibetan Plateau accelerates from −0.16 ± 0.14 m w.e. yr−1 (1965–2000) to −0.25 ± 0.10 m w.e. yr−1 (2000–2020), coinciding with a phase shift of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Anomalous North Atlantic warming triggers mid-latitude Rossby waves and an anticyclone over the northeastern Tibetan Plateau, amplifying early-21st-century regional warming through reduced clouds and albedo to enhance glacier mass loss. These results emphasize the crucial role of natural variability in the North Atlantic ocean alongside anthropogenic forcing in comprehensively understanding glacier response to future climate changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The High Mountain Asia (HMA), excluding the Antarctic and Arctic, hosts the largest fraction of Earth’s glaciers, commonly known as the Asian water tower, because it sustains irrigation, freshwater supplies, and hydropower for nearly two billion people in Asia1,2,3. As a consequence of the approximately two-fold warming faster than the global mean in this region4, the Asian water tower has experienced an imbalance in recent decades5, with the transformation of more and more ice and snow into liquid water. Progressive ice-to-water conversion has triggered frequent occurrences of glacier-associated hazards such as outbursts of glacier lakes, glacial debris flow, and ice avalanches6,7,8, posing severe threats to human lives, water resources, and ecological security in local and downstream communities.

HMA glacier changes exhibit obvious spatial heterogeneity, characterized by considerable ice mass loss in the southern Tibetan Plateau (TP) and relatively minor recession and mass loss in the northern sectors during the 21st century9,10,11,12. Specifically, glaciers in the northwestern TP (Karakoram, Pamir, and western Kunlun Mountains), are in balance or even slightly growing called a phenomenon termed the Karakoram anomaly12,13, which lasts for at least three decades. This spatial heterogeneity arises from regional differences in temperature trends and a north-south dipole precipitation pattern (wetter conditions in the north and drier conditions in the south)14,15. Divergent regional climate changes in the HMA are primarily governed by both mid-latitude westerly circulation and Asian summer monsoon, and further modulated by oceanic teleconnection associated with main SST variability modes, including the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation (AMO), the Pacific decadal oscillation (PDO) and the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD)16,17,18,19. Thus, oceanic teleconnections are likely important contributors to the TP glacier mass changes through modulating atmospheric circulation patterns. Nevertheless, the quantitative relationship between oceanic SST anomalies and regional glacier mass balance remains unclear, and the physical mechanism underlying these teleconnections is not yet fully understood.

Here, we test the role of North Atlantic sea surface temperature (NASST) anomalies in glacier mass balance in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau (NTP), where is strongly affected by mid-latitude westerlies all year round. Moisture originating from the North Atlantic is transported over long distances to the NTP region via the mid-latitude westerlies, and the North Atlantic has been identified as the primary marine oceanic source for atmospheric moisture20 in this region (Fig. S1). Additionally, we investigate the underly physical mechanisms driving glacier mass changes attributable to NASST anomalies. Annual glacier mass change data are obtained from Hugonnet et al.21. Multidecadal estimations of glacier mass balance are derived from digital elevation models (DEMs) generated using topographical maps and ASTER imagery.

Results

Interannual and multidecadal glacier mass balance in the NTP

Based on the glacier mass change dataset developed by Hugonnet et al.21 using ASTER images, we observed substantial interannual variability in aggregated glacier mass balance across the NTP from 2000 onwards. A statistically significant negative trend (p < 0.01) was evident in annual glacier mass balance during 2000–2019 (Fig. S2).

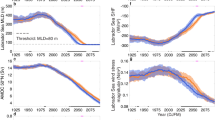

From 1965 to 2020, the NTP experienced a pronounced negative glacier mass balance of −0.19 ± 0.11 m w.e. yr−1 (Fig. 1a), with a slightly accelerated loss rate of −0.25 ± 0.10 m w.e. yr−1 during 2000–2020, compared to −0.16 ± 0.14 m w.e. yr−1 during 1965–2000 (Fig. 1b). Despite difference in mass balance estimation methodologies, our post–2000 results were consistent with those reported by Hugonnet et al.21 and Shean et al.22 in the same region (−0.29 m w.e. yr−1 and −0.28 ± 0.07 m w.e. yr−1 for the 2000–2019 and 2000–2018, respectively), and also aligned with CryoSat-2 altimetry estimates (−0.29 ± 0.22 m w.e. yr−1) between 2010 and 201923. Spatially, glacier mass loss rates were slightly higher in the eastern mountains than in the west during 2000–2020, with the highest loss observed in Lenglongling Mountain (−0.56 ± 0.13 m w.e. yr−1). Despite spatial heterogeneity, the post–2000 acceleration in glacier mass loss rates was broadly consistent across the 11 mountains (presented in Fig.1, Table S1), except Haerke Shan, where glaciers showed a slight positive balance (0.05 ± 0.02 m w.e. yr−1) during 2000–2020.

a glacier mass changes of the 11 mountain ranges in the NTP from the 1965–2000 and 2000–2020 periods, and numbers 1–11 correspond to the Altun Shan, Daxue Shan, Danghenan Shan, Tuergendaban, Chaidamu Shan, Zoulangnan Shan, Tuolai Shan, Tuolainan Shan, Shulenan Shan, Haerke Shan, and Lenglongling, respectively. Column height indicates the magnitude of glacier mass loss. b the location of the NTP within the HMA.

Influence of the NASST tripole on the interannual glacier mass balance

Glacier mass balance was highly sensitive to climatic factors, particularly temperature and precipitation. Based on detrended time series, annual glacier mass balance from Hugonnet et al.21 showed a strong negative correlation with observed summer temperature (r = −0.70, p < 0.01), but not a significant correlation with annual precipitation (r = 0.14, p > 0.05) over the NTP. Summer temperature correlated significantly (r = 0.79, p < 0.01) with the ratio of snowfall to rain, but not significantly (r = 0.33, p > 0.05) with precipitation in this region, indicating the impact of summer temperature on snowfall amount by altering the precipitation phase. These suggested that the inter-annual variations of the NTP glacier mass balance were primarily driven by summer temperature, which can be confirmed by sensitivity experiments on the Ningchan No.1 Glacier and Qiyi Glacier of this region using an energy and mass balance model24. Regional temperature and precipitation changes were often modulated by large-scale dynamic processes related to SST anomalies. We regressed global SSTs against NTP glacier mass balance from 2000 to 2019, using detrended observations to remove the background warming signal (see Methods), in order to explore the potential impact of SST anomalies on glacier mass balance variability in the region. A steady and statistically robust signal emerged in the North Atlantic Ocean (Fig. 2, Fig. S3a), whereas responses in the Pacific and Indian Oceans were weak and statistically insignificant during the same period. This spatial pattern was confirmed by the reconstructed mass balance series derived from in-situ observations of two NTP glaciers25 during 2000–2018 (Fig. S4). This signal resembled the interannual variability in NASST modes and showed a tripole pattern (Fig. S3b), which explained 33.6% of the variance in NTP glacier annual mass balance during 2000–2019 (Fig. S3c). Moreover, the dominant NASST modes were seasonally dependent, which gradually weaken from winter to summer and disappear in autumn (Fig. S5). Specially during summer (June-August, JJA), the two leading SST Empirical Orthogonal Function (EOF) modes (accounting for 38.2% variance of NASST) displayed a pronounced tripole pattern with increased strength in the second mode (Fig. 3a, b). Meanwhile, the dominant annual glacier mass loss over the NTP occurred in summer24. This suggests that summer NASST anomalies may modulate atmospheric circulation patterns that affect the annual NTP glacier mass budget (Fig. 2).

Blue dotted ellipses represent cyclonic circulation centers, while red ones indicate anticyclonic centers. Black vectors denote statistically significant regression coefficients at the 95% confidence level (p < 0.05). The blue contour line represents the 2500 m elevation threshold, based on the ETOPO5 Global Surface Relief data.

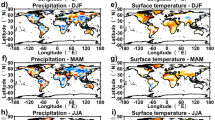

a, b Spatial patterns of the leading EOF modes of summer NASST and their corresponding normalized principal components (PCs; c, d) during 1965–2020. e, f Correlations of PC1 and PC2 with the 300 hPa geopotential height over the North Atlantic for the same period, respectively. g correlations between summer temperature in the NTP glacier region and the Northern Hemisphere 300 hPa geopotential height during 1965–2020. Black dots indicate grid points where correlation coefficients are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

The anomalous upper-level circulation over the NTP can be attributed to interannual NASST anomalies, which excited an anticyclonic–cyclonic teleconnection Rossby wave train across Eurasia26. During the positive phase of the summer NASST tripole pattern, characterized by a meridional negative-positive-negative (like −+−) SST pattern in the subtropical to subarctic North Atlantic Ocean (Fig. 3a, b), enhanced convective activity over the central North Atlantic induced strong upward motion, leading to the development of anomalous high-pressure ridges developing in the upper troposphere (Fig. 3e, f). The resulting atmospheric Rossby wave train propagated eastward through mid-latitude westerlies, causing an upper-level trough over the Mediterranean and the Central Asian-West Siberian, and an anomalous high-pressure ridge over the Ural Mountains region and the North China plain-northern TP (Fig. 3g). The high-pressure anomaly reduced total cloud cover and enhanced surface solar radiation in the NTP, accompanied by oceanic warm air resulting from the atmospheric teleconnection27,28.

Maximum covariance analysis (MCA) (see Methods) revealed that warming in the NTP was associated with an upper-level Rossby wave propagation induced by the interannual NASST anomalies (Fig. S6). MCA further identified an atmospheric fingerprint associated with the NASST patterns (Fig. S7). These analyses reproduced the NASST tripole patterns and linked them to anomalous anticyclone and cyclone over the northern hemisphere mid-latitude, further confirming a quasi-stationary atmospheric wave train driven by NASST variability consistent with the pattern shown in Fig. 3g. The positive phase of SST tripole modes can induce a atmospheric wave train (like +−+−+), leading to more frequent occurrences of anomalous blocking highs over the NTP. Anticyclonic circulation generated strong subsidence and warm southeasterly winds, further amplifying surface warming over the region. Elevated temperature intensified glacier melting. Thus, the positive phase of NASST tripole patterns can trigger an anomalous atmospheric Rossby wave train that exacerbates NTP glacier mass loss through thermal forcing.

The NASST tripole pattern can also regulate the NTP glacier mass balance by influencing precipitation changes. This study focused on investigating the role of summer precipitation on glacier changes, because it accounted for 60–80% of annual precipitation, and dominated its inter-annual variability (Fig. S8). The first leading EOF mode (explaining 26.7% of the variability) consisted of a south-north dipole over the TP with negative precipitation anomalies in the south, and positive anomalies in the north, including the NTP (Fig. 4c and Fig. S9a). The northern wetting resulted largely from a weakening of the Eurasian subtropical westerly jet (SWJ) in summer15. At the interannual scale, the summer SWJ was closely associated with the NASST tripole pattern (Fig. 4a, b). The positive phase of the NASST tripole pattern corresponded to a significant weakening of the 200 hPa zonal wind over the TP and a strengthening over the Mongolian Plateau (Fig. 4b). This dipole pattern was linked to a blocking anticyclone over the North China plain and northern TP (Fig. 3g), generated by the interannual NASST-triggered wave train. This atmospheric configuration resulted in anomalous westerly winds on the north side of the anticyclone, and easterly and southeasterly winds on the south side. The latter weakened the SWJ, promoting anomalous vertical moisture advection and hence enhancing precipitation on the NTP. The increased precipitation may be beneficial to snow accumulation over the glaciers and partly mitigate warming-induced melting. Instead, due to increased summer temperature, more precipitation fell as rain, not snowfall over the NTP24, and further caused glacier melting.

a, b The correlations between PC1 and PC2 of the North Atlantic summer SST EOF modes with Northern Hemisphere 200 hPa zonal winds during 1965–2020, respectively. Shaded areas indicate the values statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (p < 0.05). c the first EOF mode of precipitation over the TP. d The normalized principal component (PC1) of the precipitation EOF mode, the SWJ index anomaly (left y-axis), and summer precipitation anomalies over the NTP glacier regions (right y-axis). All time series were smoothed by a 9-year running mean.

AMO’s role in the multidecadal NTP glacier variations

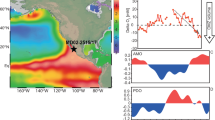

Glacier mass balance during 2000–2020 was more negative than during 1965–2000 over the NTP, corresponding to a warming of 0.83 oC, and an increase of about 7% annual precipitation for the two timespans. Despite the precipitation rise, the snow-to-rain ratio dropped by 13.6% from 1965–1999 to 2000–2020. Sensitivity experiments29 revealed that a 1.5 °C warming over 2000–2010 relative to the 1950s caused 51.9% glacier melting of the Laohugou No. 12 Glacier in this area, which required a 30% enhancement in annual snowfall to offset the resulting mass loss. Sensitivity analysis using an energy and mass balance model for Qiyi and Ningchan No.1 glaciers of this region also showed that almost all mass loss of the two glaciers from 1970–1994 to 1995–2015 resulted from increased summer temperature over the same two timespans24. Thus, the more negative NTP glacier mass balance since 2000 was primarily forced by regional summer warming. Another important factor was warming-induced reduction in precipitation falling as snow24. Given these climatic influences, a critical research priority was to elucidate how atmospheric circulation patterns modulate decadal-scale glacier mass balance variability over the NTP via their influence on temperature and precipitation patterns. On multidecadal scales, the AMO (see Methods) has been recognized as a major driver of climate variability across Eurasia30. Indeed, a strong positive correlation (r = 0.61, p < 0.01) existed between the AMO index and summer air temperature on the NTP glacier region, underscoring the important AMO’s influence on NTP glacier mass budget. Since the mid-1990s, the AMO experienced a multi-decadal shift from a cold to a warm phase (Fig. 5c). During its warm period, warmer SST caused anticyclonic circulation anomalies over the North Atlantic, which propagated a wave train of cyclonic and anticyclonic anomalies across Eurasia31 (Fig.5a), strengthening anticyclonic conditions over the NTP and increasing regional temperatures during 2000–2020. Increased temperature directly enhanced glacier melting and further exacerbated this by reducing snowpack on the glacier surface and corresponding surface albedo. As a consequence, this warming signal aligned with the observed acceleration of glacier mass loss in the NTP after 2000 (Fig.5c).

a the difference in 200 hPa geopotential height and wind fields between 1997–2020 and 1965–1996. b vertical cross-section of velocity difference between these two periods, taken from the green-shaded region in (a). c Line and blue bands represent the 9-year running mean of summer temperature anomalies in the NTP glacier regions and AMO anomalies.

Despite the important influence of anthropogenic aerosols on the weakening of summer Eurasian SWJ during the past 40 years32, a substantial portion of inter-annual and decadal variability in the SWJ since the late 20th century was attributed to the Atlantic SST variability33, i.e., interannual NASST tripole anomalies (See above) and positive phase of the AMO34, respectively. Opposite to the positive polarity of the AMO, the summer SWJ index switched from positive to negative anomalies during the mid-1990s. This switch largely resulted from the AMO-triggered anticyclonic blocking (Fig. 5a) over the Mongolian, which led to easterly anomalies and anomalous upward motion over the NTP (in front of the trough) (Fig. 5b), and caused increased precipitation (Fig. 4d). Moreover, orographic uplift enhanced ascending air motion, which in turn further promoted increased precipitation. However, due to an increase in dedacal summer temperature associated with AMO phase shift and anthropogenic forcing, the mean snow-to-rain ratio over the NTP glaciers decreased from 37.7% (1965–2000) to 24.1% (2000–2020) (Fig. S10). Furthermore, the ratio consistently remained below 0.5 throughout the post-2000 period, indicating a transition toward rainfall-dominated precipitation, which further intensified glacier ablation.

Discussion

We found that the interannual variability of the NTP glacier mass budget was closely associated with the interannual NASST tripole mode. This covariation arose that the mid-latitude westerlies, teleconnected with the extratropical Atlantic ocean climate through atmospheric wave propagation, serve as the predominant boundary conditions driving temporal variability in glacier mass budget over the NTP. In particular, atmospheric waves triggered by the interannual mode of the interannual NASST tripole pattern facilitate the occurrence of anomalous cyclone and anticyclones, and alter the SWJ strength on the NTP during summer. In turn, these changes obviously impacted local temperature and precipitation, thereby resulting in glacier mass variations. Correlation analysis using detrended time series of reconstructed mass balance against temperature and precipitation showed that temperature was the dominant driver of glacier mass loss in this region (Fig. S11), which explained approximately 47% and 60% of mass budget variations of the Qiyi Glacier and the Laohugou No.12 Glacier, respectively. By comparison, precipitation played a minor role in glacier accumulation (in Qiyi Glacier (r = 0.15, p > 0.05) and in Laohugou No.12 Glacier (r = 0.22, p > 0.05). Despite a substantial influence of the East Asian summer monsoon on glacier changes elsewhere on the TP during summer, its impact on glacier changes on the NTP was minor, as more than 95% of the glacierized regions lay outside the boundaries of the summer monsoon on the TP35.

Previous studies have recognized a warming and wetting trend since the 1980s, with an acceleration from the mid-1990s onward over Northwest China including the NTP36,37. While much of the overall warming was attributable to ongoing emission of greenhouse gases38, our analyses, based on the detrended and low-frequency-filtered observational and reanalysis data, showed that internal climate variability, especially the NASST tripole pattern and the AMO phase transition, also played a key role. The multi-decadal signatures from AMO dynamics were superimposed onto the interannual variability in NTP glacier mass balance by altering glacier melting and accumulation conditions. Simulations from the Atlantic Pacemaker experiments using CESM1 with external forcings removed exhibited that during the positive phase of the AMO, SST anomalies induced the anomalous anticyclonic circulation (Fig. S12), which propagated toward the TP via the Rossby wave trains. This led to an upper-level anticyclonic high over the NTP (Fig. S13), suppressing cloud formation and reducing surface albedo (Fig. S14), thereby enhancing regional warming, as observed higher average temperatures during 2000–2020 than 1965–2000, which accelerated glacier ablation after 2000. Furthermore, the easterly and southeasterly winds associated with the anticyclone block westerly airflow, resulting in increased precipitation. But because of elevated temperature, a decrease in the average snow-to-rain ratio during 2000–2020 was observed, relative to 1965–2000 (Fig. S10). The increased precipitation falling as rain further enhanced melting. An additional factor contributing to glacier mass loss was the deposition of light-absorbing impurities such as black carbon (BC) on glacier surfaces, which reduced the albedo and caused glacier melting. Yet, they only accounted for about 6.3% of current glacier melting on the NTP39. Therefore, projections of future glacier evolution in this region must account for both anthropogenic forcing and internal modes of climate variability such as the AMO and interannual NASST patterns.

Conclusions

This study highlights the obvious influence of NASST anomalies on glacier mass balance variability over the NTP at both interannual and multidecadal timescales. Over the past 50-plus years, glaciers in the NTP region experienced an acceleration of mass loss, with rates increasing from −0.16 ± 0.14 m w.e. yr−1 (1965–2000) to −0.25 ± 0.10 m w.e. yr−1 (2000–2020). The interannual NASST tripole pattern excited atmospheric wave trains that propagate across Eurasia, driving regional climate anomalies and then year-to-year NTP glacier mass fluctuations. At the multidecadal scale, the AMO’s phase transition from negative to positive since 2000 amplified summer warming which contributed to accelerated glacier mass loss. These findings emphasize natural oceanic variability as a critical modulator of glacier responses to ongoing climate changes in the HMA. Quantifying these linkages is imperative for projecting future glacier dynamics under anthropogenic forcing.

Data and Methods

DEM construction

A total of 84 topographic maps at the scale of 1:50000 across the NTP were collected, with contour lines with a 10-meter interval, generated by the Chinese Military Geodetic Service (CMGS) using aerial photogrammetry. After digitizing the scanned topographic map contour lines, the Delaunay triangulation method was used to create irregular triangulation networks, from which historical DEMs (here called TOPO-DEM) were constructed. Aerial photographs used to generate the topographic maps of the NTP glacier region were acquired from 1956 to 1975, with the majority (covering more than 50% glacier area) dating to the mid-1960s (Table S2). Thus, TOPO-DEM was taken to represent the entire NTP glacier surface elevation circa 1965. According to the compilation standards and specifications of the topographic Maps released by the General Administration of Quality Supervision Inspection and Quarantine40, the vertical error of topographic maps were controlled within 6–10 m for the flat or hilly regions with slopes less than 6°, 10–16 m in mountainous areas with slopes of 6°–25°, and 16–28 m in high mountain areas with slopes greater than 25°, respectively. With an average slope of 17.8° across the NTP glacier region, the TOPO-DEM vertical accuracy was estimated to be better than ±8 m.

For contemporary glacier elevation, we acquired all available AST_L1A stereo imageries (30 m resolution) covering the NTP glaciers for the 2000–2002 and 2019–2021 epochs. Using the NASA Ames Stereo Pipeline (ASP) tool, DEMs were created from the AST_L1A stereo images (3 N band and 3B band). We manually selected the high-quality and minimal-void data and mosaicked them to generate glacier surface DEMs for 2000 and 2020, respectively. The SRTM Version 3.0 Global 1 arc second dataset (SRTM GL1) served as a vertical reference. All DEMs were harmonized to the World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS84) coordinate system and EGM96 vertical datum.

Glacier extent extraction

Glacier boundaries for the NTP in 1965 were digitized directly from topographic maps. Landsat 7 Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM + ) and Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager/Thermal Infrared Sensor (OLI/TIRS) images with cloud cover less than 10%, acquired during June–October, were used to manually delineate the glacier outlines in 2000 and 2020, respectively. A total of 30 Landsat 7 ETM+ images and 26 Landsat 8 OLI_TIRS images were used (Table S3). All images were reprojected to the WGS84 geographic coordinate system and the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) projection. Co-registration with topographic maps was performed using 20–30 ground control points (GCPs), ensuring registration errors within one pixel. To enhance ice-rock spectral contrast, false-color composites were generated using Shortwave Infrared-2 (band 7), Near-Infrared (band 5), and Green (band 3) wavelengths. Glacier boundaries were then manually digitized through visual interpretation, cross-validated with the Randolph Glacier Inventory v6.0 (RGI 6.0).

Glacier mass balance changes and uncertainties

Prior to glacier surface elevation and mass balance calculations, the Nuth and Kääb co-registration method41 was used to estimate DEM misalignments and correct spatial offsets between the multi-source DEMs. This approach iteratively solved a cosine equation to estimate the direction and magnitude of displacement, based on a Python package xDEM42. Iterations terminated when either the maximum number of steps was reached or the normalized median absolute deviation (NMAD) no longer improved obviously. After differencing DEMs (dDEM) to obtain surface elevation changes, we filtered out the eliminated values with elevation changes of more than 100 m or slopes of greater than 45° to minimize noise. Then, the remaining voids in the dDEM were filled by a regional hypsometric interpolation method (integrated in the xDEM package), which assumed that elevation changes were strongly dependent on elevation and estimated elevation change gradients across the region to interpolate missing data. Ultimately, we combined the different DEMs and a snow-ice density conversion factor (\(\rho\)) (850 ± 60 kg m−3)43 to estimate the decadal glacier mass balance in the NTP region during 1965–2020. Glacier mass balance (\(\Delta {{\rm{M}}}\)) was calculated using the following formula:

where \({S}_{i}\) and \({S}_{f}\) represent the initial area and the end area of the glaciers, respectively.\(\,{y}_{1}\) and\(\,{y}_{2}\) represent the initial year and the end year, respectively. \(\Delta {{\rm{V}}}\) denotes the of glacier volume change, which is obtained by multiplying the glacier elevation change by the initial glacier area.

Following Hugonnet et al.44 and Rolstad et al.45, the glacier elevation uncertainty (\({U}_{\Delta h}\)) was estimated as the ratio of the NMAD of elevation differences on stable terrain and the arithmetic square root of the effective number of observations (\({N}_{{eff}}\)). The effective number of observations was obtained from the total pixel number of the stable topographic area and the spatial autocorrelation distance. When calculating the glacial mass balance uncertainty (\({U}_{M}\)), we also accounted for uncertainties in the glacier area error (\({U}_{A}\)), ice density (\({U}_{d}\)), and measurement extrapolation (\({U}_{e}\)), and its formula as follow:

where \(\Delta h\) represents the elevation difference, \({R}_{P/A}\) is defined as the ratio between the perimeter and area, and the value of \({R}_{{P/A}_{({Paul\; et\; al})}}\) is 5.03 km−1 46,47.

AMO and SWJ indices

The AMO index was defined here as the annual average of SST anomalies over the North Atlantic according to Enfield et al.48. Its spatial pattern resembled the first EOF pattern of the NASST, characterized by dominant warming in the North Atlantic and a bi-center structure near southern Greenland and the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Following previous studies15,32, the subtropical westerly jet (SWJ) was defined as the averaged zonal wind over 35°–45°N, 40°-120°E.

Correlation, regression, EOF, and MCA

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated after removing long-term trends from the datasets. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied to calculate the statistical significance of all regressions and correlations. Additionally, to further verify how NASST affects temperature and precipitation variations as well as glacial mass balance in the NTP region by influencing atmospheric circulation anomalies, we analyzed summer-mean horizontal wind fields, geopotential height fields, vertical velocity, water vapor flux, snow-to-rain ratio, and albedo differences/anomalies for the 1965–2000 and 2000–2020 periods. All variables were derived from the ERA5 reanalysis, with the exception of snowfall and rainfall, which were sourced from the ERA5-Land dataset.

Empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis was applied to extract the meridional tripole structure of the North Atlantic (0°–70°N, 90°W–15°E) SST variability during 1965–2020, with positive (negative) loadings in the south of Greenland and the subtropics, and negative (positive) loadings in between (Fig. 3a, b; Fig. S5). Moreover, the first two leading modes of summer precipitation across the TP were also extracted by the EOF analysis (Fig. S9).

The maximum covariance analysis (MCA), also known as singular value decomposition, was used to determine the dominant coupled patterns between the 300 hPa geopotential height over the northern hemisphere and both the summer temperature of the entire TP region (Fig. S6) and the NASST (Fig. S7). Remarkably, the correlation, regression, EOF, and MCA analysis results were conducted using detrended and low-pass filtered summer mean datasets.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

AST_L1A stereo imageries are obtained from NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/). Landsat images are available at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS, https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/). Global monthly mean SST data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Extended Reconstructed SST Version 5 dataset are available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html. The ECMWF ERA5 reanalysis product is available at https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/datasets. The ERA5-Land dataset product is also publicly available through the official ECMWF data portal at: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets. The AMO index can be downloaded at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/timeseries/AMO/. SRTM DEMs are obtained from the USGS EROS archive (https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-digital-elevation-shuttle-radartopography-mission-srtm-1). Monthly gridded temperature and precipitation (0.5° × 0.5°) from the CRU TS Version 4.07 dataset come from the UK National Centre for Atmospheric Science (NCAS) (https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/cru_ts_4.07/). The Community Earth System Model version 1 (CESM1) Atlantic Pacemaker Simulations dataset is available at https://www.earthsystemgrid.org/dataset/ucar.cgd.ccsm4.ATL-PACEMAKER.html.

Code availability

The data in this study are analyzed with widely available tools in Python. Contact the Corresponding author for specific code requests.

References

Immerzeel, W. W. et al. Importance and vulnerability of the world’s water towers. Nature 577, 364–369 (2020).

Immerzeel, W. W., Beek, L. P. H. & Bierkens, M. F. P. Climate change will affect the Asian Water Towers. Science 328, 1382–1385 (2010).

Nie, Y. et al. Glacial change and hydrological implications in the Himalaya and Karakoram. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 91–106 (2021).

Yao, T. et al. Recent Third Pole’s rapid warming accompanies cryospheric melt and water cycle intensification and interactions between monsoon and environment: Multidisciplinary approach with observations, modeling, and analysis. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-17-0057.1 (2019).

Yao, T. et al. The imbalance of the Asian water tower. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 618–632 (2022).

Carrivick, J. L. & Tweed, F. S. A global assessment of the societal impacts of glacier outburst floods. Glob. Planet. Change 144, 1–16 (2016).

Wang, X., Liu, S. & Zhang, J. A new look at roles of the cryosphere in sustainable development. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 10, 124–131 (2019).

Huggel, C. Effects of climate change on mass movements in mountain environments. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 36, 421–439 (2012).

Dehecq, A. et al. Twenty-first century glacier slowdown driven by mass loss in High Mountain Asia. Nat. Geosci. 12, 22–27 (2019).

Bhattacharya, A. et al. High Mountain Asian glacier response to climate revealed by multi-temporal satellite observations since the 1960s. Nat. Commun. 12, 4133 (2021).

Brun, F., Berthier, E., Wagnon, P., Kääb, A. & Treichler, D. A spatially resolved estimate of High Mountain Asia glacier mass balances from 2000 to 2016. Nat. Geosci. 10, 668–673 (2017).

Bolch, T. et al. The state and fate of Himalayan glaciers. Science 336, 310–314 (2012).

Kääb, A., Berthier, E., Nuth, C., Gardelle, J. & Arnaud, Y. Contrasting patterns of early twenty-first-century glacier mass change in the Himalayas. Nature 488, 495–498 (2012).

Yao, T. et al. Different glacier status with atmospheric circulations in Tibetan Plateau and surroundings. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 663–667 (2012).

Jiang, J. et al. Precipitation regime changes in High Mountain Asia driven by cleaner air. Nature 623, 544–549 (2023).

Zhang, K., Zuo, Z., Suarez-Gutierrez, L. & Bu, L. The significant influence of the Atlantic multidecadal variability to the abrupt warming in Northeast Asia in the 1990s. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 28 (2024).

Dong, W., Ming, Y., Deng, Y. & Shen, Z. Recent wetting trend over Taklamakan and Gobi Desert dominated by internal variability. Nat. Commun. 15, 4379 (2024).

Cai, Q. et al. Recent pronounced warming on the Mongolian Plateau boosted by internal climate variability. Nat. Geosci. 17, 181–188 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Interannual variation in the East Asian summer monsoon-tropical Atlantic SST relationship modulated by the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 169 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Oceanic climate changes threaten the sustainability of Asia’s water tower. Nature 615, 87–93 (2023).

Hugonnet, R. et al. Accelerated global glacier mass loss in the early twenty-first century. Nature 592, 726–731 (2021).

Shean, D. E. et al. A systematic, regional assessment of High Mountain Asia glacier mass balance. Front. Earth Sci. 7, 363 (2020).

Jakob, L., Gourmelen, N., Ewart, M. & Plummer, S. Spatially and temporally resolved ice loss in High Mountain Asia and the Gulf of Alaska observed by CryoSat-2 swath altimetry between 2010 and 2019. Cryosphere 15, 1845–1862 (2021).

Zhu, M. et al. What induces the spatiotemporal variability of glacier mass balance across the Qilian Mountains. Clim. Dyn. 59, 3555–3577 (2022).

Su, B. et al. Glacier change in China over past decades: Spatiotemporal patterns and influencing factors. Earth-Sci. Rev. 226, 103926 (2022).

Song, Y. & Chen, H. Influence of the late-winter North Atlantic tripole sea surface temperature anomalies on spring land surface temperature in mid-to-high latitudes of western Eurasia. J. Clim. 36, 4933–4950 (2023).

Rounce, D. R. et al. Global glacier change in the 21st century: Every increase in temperature matters. Science 379, 78–83 (2023).

Mölg, T., Maussion, F., Collier, E., Chiang, J. C. H. & Scherer, D. Prominent midlatitude circulation signature in High Asia’s surface climate during monsoon. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 122, 712 (2017).

Chen, J. Z. et al. Mitigation of black carbon emissions could immediately reduce 6.3% of glacier melting in the Qilian Mountains. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 15, 725–736 (2024).

Ehsan, M. A. et al. Atlantic Ocean influence on Middle East summer surface air temperature. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 3, 5 (2020).

Zang, Y., Zhao, H., Klotzbach, P. J., Wang, C. & Cao, J. Relationship between the South Asian High and Western North Pacific tropical cyclone genesis. Atmos. Res. 281, 106491 (2023).

Dong, B., Sutton, R. T., Shaffrey, L. & Harvey, B. Recent decadal weakening of the summer Eurasian westerly jet attributable to anthropogenic aerosol emissions. Nat. Commun. 13, 1148 (2022).

Lin, L. et al. Atlantic origin of the increasing Asian westerly jet interannual variability. Nat. Commun. 15, 2155 (2024).

Sun, J. et al. Why Has the inner Tibetan Plateau become wetter since the Mid-1990s? https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0471.1 (2020).

Huang, L. et al. The northern boundary of the Asian summer monsoon and division of westerlies and monsoon regimes over the Tibetan Plateau in present-day. Sci. China Earth Sci. 66, 882–893 (2023).

Chen, F. et al. Discussion of the “warming and wetting” trend and its future variation in the drylands of Northwest China under global warming. Sci. China Earth Sci. 66, 1241–1257 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Climatic warming and humidification in the arid region of Northwest China: Multi-Scale characteristics and impacts on ecological vegetation. J. Meteorol. Res 35, 113–127 (2021).

Zhou, T. & Zhang, W. Anthropogenic warming of Tibetan Plateau and constrained future projection. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 044039 (2021).

Chen, J.-Z. et al. Mitigation of black carbon emissions could immediately reduce 6.3% of glacier melting in the Qilian Mountains. Adv. Clim. Change Res. S1674927824000868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accre.2024.06.010 (2024).

General Administration of Quality Supervision Inspection and Quarantine (2008) GB/T 12341-2008: Compilation specifications for national fundamental scale Maps. Part 1: Compilation specifications for 1:25000/ 1:50000/1:100000 topographic Maps. General Administration of Quality Supervision Inspection and Quarantine, Beijing (in Chinese).

Nuth, C. & Kääb, A. Co-registration and bias corrections of satellite elevation data sets for quantifying glacier thickness change. Cryosphere 5, 271–290 (2011).

Mälicke, M. SciKit-GStat 1.0: a SciPy-flavored geostatistical variogram estimation toolbox written in Python. Geoscientific Model Dev. 15, 2505–2532 (2022).

Huss, M. Density assumptions for converting geodetic glacier volume change to mass change. Cryosphere 7, 877–887 (2013).

Hugonnet, R. et al. Uncertainty analysis of digital elevation models by spatial inference from stable terrain. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 15, 6456–6472 (2022).

Rolstad, C., Haug, T. & Denby, B. Spatially integrated geodetic glacier mass balance and its uncertainty based on geostatistical analysis: application to the western Svartisen ice cap, Norway. J. Glaciol. 55, 666–680 (2009).

Braun, M. H. et al. Constraining glacier elevation and mass changes in South America. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 130–136 (2019).

Paul, F. et al. On the accuracy of glacier outlines derived from remote-sensing data. Ann. Glaciol. 54, 171–182 (2013).

Enfield, D. B. et al. The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation and its relationship to rainfall and river flows in the continental U.S. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 2077–2080 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFA0608202), Taishan Scholars Program of Shandong Province (No. tsqn202312158), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41971081, 41101072, and 41671072), and the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (No. 252300421473).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.T.W. and M.Z. designed and performed the research, and wrote the original draft; Z.Z. and Y.Z.W. processed and analyzed data; All authors contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript, with S.H., Z.L., and W.S. participating in the process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Communication thanks Manuel Tobias Blau and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jennifer Veitch and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

43247_2025_2851_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Information for North Atlantic Ocean natural variability drives glacier mass loss over the Northeastern Tibetan Plateau

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, M., Wang, Y., Hou, S. et al. North Atlantic Ocean natural variability drives glacier mass loss over the Northeastern Tibetan Plateau. Commun Earth Environ 6, 843 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02851-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02851-8