Abstract

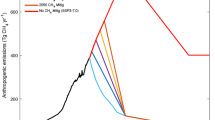

Human activities are expected to delay the next glacial inception because of the long atmospheric lifetime of anthropogenic CO2. Here we present Earth system model simulations for the next 200,000 years with dynamic ice sheets and interactive atmospheric CO2, exploring how emissions will impact a future glacial inception. Historical emissions (500 PgC) are unlikely to delay inception, expected to occur under natural conditions around 50,000 years from now, while a doubling of current emissions (1000 PgC) would delay inception for another 50,000 years. Inception is generally expected within the next 200,000 years for emissions up to 5000 PgC. Our model results show that assumptions about the long-term balance of geological carbon sources and sinks has a strong impact on the timing of the next glacial inception, while millennial-scale variability in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation influences the exact timing. This work highlights the long-term impact of anthropogenic CO2 on climate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past 2.6 million years (the Pleistocene), Earth’s climate has been characterized by glacial cycles, i.e., quasi-periodic patterns of long, cold glacials followed by shorter, warm interglacials. These glacial cycles were driven by seasonal variations in insolation caused by changes in orbital configuration, and shaped by internal feedbacks between ice sheets, the climate, the solid Earth1,2, and the carbon cycle3. According to Milankovitch theory, a new glacial cycle begins (i.e., glacial inception) when there is a prolonged period of low summer insolation in high-latitude regions of the Northern Hemisphere (NH). Snow that is not completely melted during summer turns into ice, and the increasing albedo reinforces ice accumulation year after year4,5,6,7.

Although summer insolation during the Holocene has already reached its minimum, there is no sign of an imminent glacial inception despite the 100 kyr cyclicity that has persisted during the last 800 kyr. Some argue that, under hypothetical non-anthropogenic conditions, the current interglacial would have already ended8,9,10,11; others suggest that we were already pre-dispositioned for an interglacial longer than 10 kyr as a result of a minimum in the 100-kyr and 400-kyr eccentricity cycles12,13,14, similar to the prolonged interglacial observed during Marine Isotope Stage 1115,16. Various estimates have been given for the potential duration of this exceptionally long interglacial. A few studies have proposed that the current interglacial would persist until ~10 kyr AP (after present)17,18 or ~20 kyr AP19, but more often, estimates of ~40–60 kyr AP have been provided using a variety of modeling tools20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29.

Considering that anthropogenic activities over the past few centuries have increased atmospheric CO2 concentration beyond natural Pleistocene levels to ~420 ppm30, the natural length of the Holocene interglacial may now only be of theoretical interest. This is because atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, particularly CO2, will also affect summer temperatures in the NH, and the critical insolation required to trigger glacial inception will vary with atmospheric CO2 concentration28,31. Although glacial inceptions were triggered by decreasing summer insolation over the past ~1 million years, the timing of the next glacial inception will additionally depend on the amount of anthropogenic carbon emissions. This CO2 effect is particularly relevant for the next ~100 kyr because of weak orbital forcing associated with a minimum in Earth’s eccentricity32. Given that anthropogenic CO2 emissions will remain in the atmosphere over the coming millennia due to their long lifetime22,33,34, elevated CO2 concentrations will likely delay the onset of the next glacial period28,29. Predicting the timing of the next glacial cycle under anthropogenic conditions, therefore, strongly depends on our ability to model long-term carbon cycle dynamics.

Despite efforts to model climate change over the next century, the long-term trajectory of the Earth system is essential for both ethical and practical reasons. From a broad perspective, such simulations help to understand the full extent of the Anthropocene: will anthropogenic impacts become negligible in a few multi-millennia, or will they fundamentally change the Earth’s natural cycles on orbital timescales and beyond? On a more practical level, long-term climate projections are necessary to assess the safety of high-level radioactive waste repositories, which must remain secure for hundreds of thousands of years. While this is not the first work to discuss the deep future climate evolution and the impact of human activity on future glacial cycles14,22,28,29,35,36, we revisit this topic now with ongoing discussions on the definition of the Anthropocene, and the construction of the fast Earth system model CLIMBER-X, which represents a substantial advancement in model complexity compared to previous studies on this topic.

Here, we present a set of long-term transient coupled climate-carbon cycle-ice sheet model simulations under different emission scenarios for the next ~200 kyr using CLIMBER-X (section “Model”). We explore how the timing of the next glacial inception depends on the magnitude of cumulative anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Our results show that assumptions about the long-term balance of geological carbon sources and sinks have profound implications on the timing of the next glaciation. This calls into question assumptions used by most previous studies that the carbon cycle was in quasi-equilibrium at the pre-industrial time, as the carbon cycle responds over very long timescales and is therefore heavily influenced by the climate history of previous glacial cycles. In addition to this, we highlight the potentially critical role of millennial-scale variability in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) on a future glacial inception. To the best of our knowledge, these are the first transient simulations of the next glacial inception under natural and anthropogenic conditions performed using a fully coupled (climate-carbon cycle-ice sheet) Earth system model.

Results

Effect of imbalances in the carbon cycle

To project the long-term evolution of atmospheric CO2 and climate, it is necessary to make assumptions about the initial conditions of the carbon cycle. The ocean and land carbon cycle can be assumed to be reasonably close to equilibrium during the pre-industrial time as a result of relatively stable conditions persisting over most of the Holocene (~12 kyr). This time is sufficiently long even for the equilibration of slow ocean biogeochemical processes (e.g., ocean circulation) and permafrost carbon. For centennial projections, carbon exchange between the atmosphere, ocean, and land is generally sufficient to consider. On multi-millennial timescales and beyond, however, the response of marine sediments becomes important, and geological sources and sinks of carbon from sediment burial and chemical weathering on land must be accounted for. In such an open carbon cycle setup, the absence of a long-term drift in CO2 implies that, on the long-term average (i.e., a few hundreds of thousands of years), volcanic CO2 outgassing has to provide half of the atmospheric CO2 consumed by silicate weathering37,38, for more details see section S1.1.

Some studies investigating the long-term response of the climate assume that the pre-industrial state was in equilibrium, which also implies that a constant volcanic outgassing is assumed to balance half of the pre-industrial silicate weathering rate29,33,34,36. However, it is well established that the silicate weathering rate depends on climate, the so-called geological “thermostat" of Earth39,40,41, meaning that it is expected to vary substantially over glacial–interglacial cycles. Since most of the last ~1 million years has been colder than the pre-industrial, and CO2 concentrations have remained nearly constant when averaged over multiple glacial cycles, it is reasonable to assume that volcanic outgassing should provide the equivalent of one-half of the average CO2 consumption by silicate weathering over one or more glacial cycles. The maximum imbalance between the two has been shown to be less than 1–2% over the Pleistocene42.

In a set of experiments using prescribed present-day ice sheets, we apply two different constant volcanic outgassing rates to first examine how different assumptions about the pre-industrial balance of the carbon cycle influence the natural (i.e., in the absence of anthropogenic emissions) evolution of simulated future atmospheric CO2 concentrations. These rates, determined in the section “Initialization of the carbon cycle,” correspond to (1) half the estimated pre-industrial silicate weathering rate and to (2) half the average silicate weathering rate over the last glacial cycle.

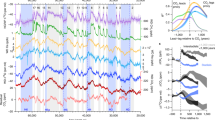

In our model, the assumption that the carbon cycle is in balance at the pre-industrial time (PIeq) corresponds to a constant volcanic outgassing of 0.0706 PgC yr−1 (Table 1). This results in simulated CO2 concentrations that remain relatively stable for the whole simulation period of 200 kyr (Fig. 1). In the PIeq experiment, atmospheric CO2 concentration responds to the evolving orbital configuration of the Earth, oscillating by up to ±20 ppm around the long-term average of about 280 ppm (Fig. S1). The more realistic assumption where volcanic outgassing is equal to half the average CO2 consumption rate by silicate weathering over the last glacial cycle (LGCeq) requires a constant volcanic outgassing of 0.0559 PgC yr−1 (Table 1), which is about 20% smaller than in PIeq. This rate is similar to those used in other studies that have successfully simulated previous glacial cycles3,43,44 and leads to a CO2 decreasing trend induced by the pre-industrial imbalance between geological carbon sources and sinks. This results in a substantial change in simulated atmospheric CO2 from PIeq within only a few tens of kyr (Fig. 1). In the LGCeq experiment, atmospheric CO2 concentration reaches ~220 ppm after 200 kyr, and is substantially lower than in PIeq, which is ~280 ppm at this time (Fig. 1). Although we assume that the LGCeq setup is the most realistic, it should be noted that, due to poor constraints on present-day silicate weathering rates and the sensitivity of both silicate weathering and volcanic outgassing to glacial–interglacial variability45,46,47, the value used for volcanic outgassing in LGCeq has considerable uncertainties. Therefore, we also present results from the PIeq setup, which represents an upper bound on future CO2 concentrations.

In (a), we show atmospheric CO2 concentration for the past 200 kyr, and the simulated natural evolution of atmospheric CO2 for the next 200 kyr. With this, we demonstrate the resulting long-term trend in atmospheric CO2 evolution due to the carbon cycle imbalance arising between outgassing and weathering (PIeq vs. LGCeq), leading to substantially different climate evolutions over the 200 kyr period. In (c), we display the assumption that the carbon cycle is in balance with average glacial cycle conditions (LGCeq), which necessitates a constant volcanic outgassing of 0.0559 PgC yr−1 that ultimately produces a negative decreasing trend in atmospheric CO2. Given considerable uncertainties in this value, we simulated future atmospheric CO2 concentrations for values which are ±5–10% the constant volcanic outgassing used in LGCeq. In light of this, we also display in (b) the assumption where the carbon cycle is in balance at the pre-industrial time (PIeq). We consider this to be an upper bound on plausible future CO2 concentrations, which necessitates a constant volcanic outgassing of 0.0706 PgC yr−1. The proxy record (black) shows a reconstruction of atmospheric CO2 concentration from the EPICA Dome C and Vostok ice cores97. A 300-year rolling mean was applied to the simulated data shown here for visibility. Sketches (b, c) were created in part using modified images from the UMCES IAN Media Library under a Creative Commons license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/CC BY-SA 4.0. In these sketches, we show volcanic outgassing must equal one-half atmospheric CO2 consumption via silicate weathering on timescales >100,000 years. This is explained with further detail in section S1.1. It should be noted that most of the carbon from volcanic CO2 outgassing originates from hydrothermal sources (e.g., along mid-ocean ridges), and only a small amount is contributed from sub-aerial volcanoes.

Natural length of the current interglacial

We use Eq. (1), the critical insolation–CO2 relation for glacial inception28,31 to predict the timing of the next glaciation using the simulated atmospheric CO2 and the well-known future evolution of maximum insolation at 65°N (smx65 in Wm−2, 32). This is done by determining when simulated atmospheric CO2 falls below the “inception threshold" (CO2,cr in ppm):

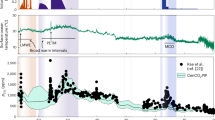

At different insolation minima over the next 200 kyr, the associated level of CO2,cr ranges between approximately 185 ppm (at 37 kyr AP) to approximately 325 ppm (at 170 kyr AP) (Table S1). The relation suggests that, under present-day insolation conditions, an imminent glacial inception would only be possible if CO2 concentration drops below approximately 235 ppm (Table S1), demonstrating that the current climate is far from conditions required for glacial inception. Present-day inception thresholds for CO2 concentration identified by other studies (e.g., 210 ppm20, 245 ppm48, or 270 ppm23) would not be crossed either. For the PIeq experiment, glacial inception under the natural evolution of the Earth system (i.e., the “natural timing” of glacial inception) is predicted to occur around 126 kyr AP, with a CO2 concentration of approximately 285 ppm (Fig. 2d, Table S2). For the LGCeq experiment, the natural timing changes considerably, and glacial inception is predicted to occur around 52 kyr AP with a CO2 concentration of approximately 260 ppm (Fig. 2e, Table S2). This aligns with some previous estimates placing the next glacial inception at around 50 kyr AP20,22,23,24,25,26,28,29.

The orbital parameters of (a) eccentricity modulated precession and (b) obliquity have been taken from Laskar et al.32. The maximum annual insolation at 65°N in (c) was also taken from Laskar et al.32. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the last 200 kyr (gray) in (d, e) were taken from the EPICA Dome C and Vostok ice cores97. The glacial inception threshold (light blue) was calculated using Eq. (1). Future CO2 concentrations were plotted for the (d) PIeq ensemble and (e) the LGCeq ensemble. The vertical lines in (d, e) correspond to the predicted timing of glacial inceptions (Table S2). For reference, 280 ppm is denoted using a horizontal gray line in (d, e).

To evaluate our prediction for the natural timing of glacial inception, done using Eq. (1), we repeat the LGCeq simulation with interactive ice sheets (LGCeq_ice) in the NH (Table 1). For this, we consider a doubling of present-day NH ice sheet area as our criterion for a simulated glacial inception (section “Definition of glacial inception”). Over the first 40 kyr of the simulation, some high-altitude areas become glaciated (e.g., Baffin Mountains) due to successive insolation minima at ~17 kyr and ~37 kyr (Table S1). However, more sites become nucleated around 45 kyr AP (Fig. 3c), and global mean sea-level, which remained nearly constant for the first ~40 kyr of the simulation, starts to fall at this time due to an increase in land ice volume (Fig. 3d). This change in sea-level is particularly heterogeneous, due to the 3D Earth structure employed from Bagge et al.49 (Fig. 4g). Millennial-scale variability in AMOC also begins around 45 kyr AP (Figs. 3b and 5a, h) and closely resembles past Dansgaard–Oeschger events50,51, which are realistically reproduced by CLIMBER-X52.

This figure depicts NH ice sheet and climate conditions from the LGCeq_ice experiment. Colors for the timeseries and trajectories here correspond to the different emission scenarios shown in Fig. 2. The simulated (a) change in global mean temperature from the pre-industrial, (b) maximum strength of the AMOC, (c) NH ice sheet area, and (d) NH ice sheet volume in m sle (meters sea-level equivalent) is shown. In (e), the evolution of simulated ice area as a function of the difference between maximum summer insolation and smx65cr (the “critical insolation” for glacial inception, determined by inverting Eq. (1) and using simulated atmospheric CO2 concentration) is presented, showing trajectories corresponding to the different emission scenarios. All trajectories in (e) from present-day (white marker). A crossing below 0 in the x-axis, synonymous with CO2 crossing the inception threshold (here represented through smx65cr), is shown here to lead to a rapid expansion of ice sheet area that puts trajectories in a glacial state. For visibility, a 300-year rolling mean was applied to (a–d), and a 30-year rolling mean was applied to (e). The predicted timing for glacial inception in the different emission scenarios (as determined using Eq. (1) and shown in Fig. 2e, Table S2) is given by the shaded vertical lines in (a–d). The simulated timing of glacial inception (Table S2), defined in our study as the time when NH ice sheet area doubles from present day (horizontal gray line in c), is denoted in (c, e) using colored markers. Data is only shown here for 5 kyr after the simulated timing of glacial inception (indicated using dashed lines), as discussed in the sections “Experiments” and “Definition of glacial inception”.

The time slices of (a–c) 45 kyr AP, (d–f) 51 kyr AP, and (g–i) 55 kyr AP correspond to the timing before, during, and after the simulated natural timing of glacial inception in the LGCeq_ice experiment (~52 kyr AP). The (a, d, g) natural evolution, (b, e, h) 1000 PgC, and (c, f, i) 5000 PgC scenarios were plotted to show the complete range of potential ice sheet evolutions, with changes in relative sea-level highlighting the effects of glacial isostatic adjustment and ice sheet melt.

Summer insolation (defined as maximum insolation at 65°N) is shown in (a–g) to compare the timings of the next glacial inception and the future summer insolation minimum. The predicted timing of glacial inception based on the critical insolation–CO2 relation is also provided for comparison (gray vertical lines, Table S2). Maximum strength of AMOC and NH ice sheet area is shown for the (h) natural evolution, and for the (i) 500 PgC, (j) 1000 PgC, (k) 2000 PgC, (l) 3000 PgC, (m) 4000 PgC, (n) 5000 PgC emission scenarios. Data were taken from the LGCeq_ice experiment. The 15 kyr leading up to the simulated glacial inception (black dashed lines, Table S2), and the 5 kyr following it, are plotted. Data is cut ~5 kyr after inception, as discussed in the sections “Experiments” and “Definition of glacial inception”.

This variability in AMOC can be attributed to convective instability in the northern North Atlantic, which arises when the net surface buoyancy loss averaged over northern North Atlantic and Arctic approaches zero. As outlined in Willeit et al.52, deep convection in these regions can only be sustained under net negative surface buoyancy flux conditions. As CO2 levels decline, buoyancy loss progressively decreases, driven by several factors related to a weakened meridional heat transport, and a reduced thermal expansion coefficient of seawater at lower temperatures52. Generally, the abrupt weakening of the AMOC into a Stadial state leads to a reduction in the northward transport of warm surface waters and an expansion of sea ice (Fig. S2). This causes widespread cooling in the northern North Atlantic, thereby facilitating the formation of these additional nucleation sites and the lateral expansion of NH ice sheets. The effect of AMOC-induced summer cooling dominates over the decrease in annual precipitation, and leads to a net increase of the surface mass balance over ice sheets (Fig. S2). The orbital configuration is also expected to influence the stability of the AMOC, as contributing factors such as sea ice area are strongly shaped by insolation.

The simulated natural timing of glacial inception generally agrees well with the predicted timing determined by the critical insolation–CO2 relation, with a doubling of NH ice area by ~52 kyr AP (Fig. 3c, Table S2). At this time, deep convection in both the Arctic and North Atlantic cannot be sustained, and ice area rapidly increases over the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and Scandinavian Mountains (Fig. 4d, g). Widespread ice sheet growth at nucleation sites over Svalbard, Franz Josef Land, Novaya Zemlya, the Scandinavian Mountains, and the Pacific and Arctic Cordillera coalesce into the Barents, Fennoscandian, Cordilleran, Innuitian, and Foxe–Baffin ice sheets. This is consistent with patterns of ice sheet development during the last glacial cycle in North America and Eurasia53,54,55,56,57. Following this, ice sheets in North America and Eurasia merge by 53 kyr AP, demonstrating the formation of future North American and European ice sheet complexes (Fig. S3). After inception, the relative sea-level rises around the ice sheets due to an increased gravitational attraction and regional subsidence by the growing ice sheets, while sea-level falls in the far field due to the accumulation of ice on land (Fig. 4g). The forebulge surrounding the subsiding regions lowers sea-level, and is most pronounced in regions where the considered mantle viscosity is small, e.g., in the mid-Atlantic, and at the northwestern Pacific coast.

Anthropogenic global warming and the next glaciation

Anthropogenic activities are projected to further raise atmospheric CO2 levels and global temperatures. In the absence of considerable carbon dioxide removal efforts, it is expected that the land and ocean in combination will absorb up to ~60% of emissions33,34,58,59, leading to a sharp decline in atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the first millennium after anthropogenic emissions cease. On longer timescales, however, the climate–silicate weathering feedback will control the lifetime of anthropogenic CO234,58,59, shaping the Earth’s long-term carbon cycle response. In the LGCeq experiment, this is combined with a CO2 decreasing trend, as the pre-industrial state is not in balance, and half the CO2 consumption rate by silicate weathering is not completely compensated by volcanic outgassing. This results in atmospheric CO2 concentrations returning to pre-industrial levels faster than in some previous studies22,36, bringing the Earth system closer to the inception threshold.

The timing of the next glacial inception, as predicted by Eq. (1), varies substantially depending on the level of cumulative emissions (ensemble ranging from 0 to 5000 PgC) and on the assumed carbon cycle (im)balance (PIeq vs. LGCeq). In the PIeq experiment, glacial inception is predicted to occur around or after ~170 kyr AP for emission scenarios 500 PgC and larger (Fig. 2d, Table S2). In contrast, the predicted timing of glacial inception in the LGCeq experiment is more evenly distributed over the 200 kyr simulation duration during four periods of sufficiently low insolation (Fig. 2e, Table S2).

Similar to the section “Natural length of the current interglacial,” we rerun the LGCeq experiment with interactive ice sheets (LGCeq_ice) to evaluate our prediction. Ice sheet volume in the 500 PgC scenario closely follows the natural evolution, and glacial inception is simulated at approximately the same time as for the natural evolution at ~50 kyr AP, as predicted (Figs. 3c and S4a, b). Cumulative CO2 emissions of 1000 PgC are enough to evade inception at ~50 kyr AP (Fig. 4h) and postpone it to ~100 kyr AP (Figs. 3c and S4c, d). Emissions higher than 1000 PgC lead to an initial loss of the Greenland ice sheet due to a combination of high CO2 and several summer insolation maxima (Figs. 3c and 4h, i). Although glacial inception in the 4000 and 5000 PgC scenarios is simulated when predicted at ~170 kyr AP (Figs. 3c and S4i–l), it does not occur when predicted at ~125 kyr AP for the 2000 and 3000 PgC emission scenarios (Fig. 3c). Two interconnected reasons could explain this. Not only is there a regional warming effect from the missing Greenland ice sheet60 that is not accounted for in the critical insolation–CO2 relation (since Eq. (1) was derived in the presence of the Greenland ice sheet), but the 2000 and 3000 PgC emission scenarios also lack millennial-scale AMOC variability at ~125 kyr AP as atmospheric CO2 concentrations are too high52. Despite this, the low insolation minimum at ~170 kyr AP ensures that inception occurs at the latest during that time, at least for emissions up to 5000 PgC (Fig. 3c, Table S2). The spatial patterns of ice sheet growth during glacial inception is similar to that of the natural evolution, with an initial ice nucleation over high altitude sites, followed by widespread expansion and thickening of ice sheets (Fig. S4).

Discussion

We presented, to the best of our knowledge, the first, fully coupled climate-carbon cycle-ice sheets model simulations for the next 200,000 years and investigated how the timing of the next glacial inception varies under different scenarios of cumulative anthropogenic carbon emissions. For emissions of 500 PgC and less, glacial inception is simulated around 50 kyr AP, while a doubling of present-day emissions (~1000 PgC) would delay inception at the 50 kyr AP insolation minimum to approximately 100 kyr AP. Although historical carbon emissions have already contributed ~500 PgC in cumulative emissions, low-emission scenarios with net negative emissions (e.g., SSP1-2.6, SSP4-3.4, SSP5-3.4-OS) are projected to result in similar levels of cumulative emissions (Fig. S5). To further frame this in the context of climate policy, cumulative emissions are expected to reach 1000 PgC by ~2070 in intermediate-emission scenarios such as SSP2-4.5 and as early as ~2050 in high-emission scenarios like SSP5-8.5 (Fig. S5). Our study shows that the next glacial inception will likely occur before 200 kyr AP in all emission scenarios (up to 5000 PgC) when accounting for the long-term CO2 decreasing trend resulting from the imbalance between geological carbon sinks and sources (Fig. 2e). If this trend is not accounted for, glacial inception is predicted to occur by the 170 kyr AP insolation minimum at the latest for all emission scenarios less than 5000 PgC (Fig. 2d). This is because summer insolation is substantially lowered at this time, allowing glacial inception to be triggered even at relatively high CO2 concentrations of ~325 ppm.

Both the predicted and simulated timing of glacial inception are in agreement with some previous studies28,35,61, but are notably different than others, whose results suggest that even intermediate emissions could postpone glacial inception for up to 500 kyr29,36. There are two reasons for this. First, the strength of the silicate weathering feedback in CLIMBER-X, while within range of other models, is relatively strong and falls on the higher end of the spectrum34. Secondly, the latter studies made the implicit assumption that the carbon cycle was in equilibrium during the pre-industrial time, such that atmospheric CO2 concentration would eventually return to and remain around 280 ppm following an anthropogenic perturbation. This assumption is equivalent to the one made in the PIeq experiment, where there is no negative trend in the long-term CO2 evolution due to the carbon cycle imbalance arising between outgassing and weathering (Fig. 2d).

The simulated timing of the next glaciation in the LGCeq_ice experiments is generally well predicted by the critical insolation–CO2 relation28,31. The only exceptions occur in two scenarios where the Greenland ice sheet is initially melted and fails to regrow before glaciation starts in other parts of the NH, as the ice sheet exhibits hysteresis behavior62,63,64. This is to be expected, as the critical insolation–CO2 relation was derived under the implicit assumption of an ice-covered Greenland. An ice-free Greenland would warm the climate in some inception regions60, thus requiring lower CO2 concentrations to trigger widespread glaciation. Future AMOC variability is also shown to influence the timing of the next glacial inception, suggesting a potential causal relationship between rapid climate shifts in the North Atlantic and the onset of glaciations (Figs. 5, S6 and S7). Sediment core data partly confirms this behavior, as strong millennial-scale climate variability has almost always occurred after the end of each interglacial stage65. A potential role of AMOC weakening for the last glaciation has also been suggested by different modeling studies66,67,68,69. AMOC variability is likely to play a more prominent role in facilitating a future glacial inception than it did for many past glacial inceptions. This is because summer insolation minima in the coming ~150 kyrs are comparatively weak (Fig. 2c), and low CO2 concentrations will be required to trigger glacial inception, which in turn implies a more unstable AMOC52.

Although simulated atmospheric CO2 concentrations in the PIeq experiment fall below the inception threshold at the 170 kyr AP insolation minimum (<325 ppm, Table S1), millennial-scale variability in AMOC still requires a lower CO2 concentration to occur52. If such variability plays an important role in triggering glacial inception, then it is still possible that elevated CO2, by inhibiting this variability, can continue to delay inception. This is especially relevant for PIeq experiments with interactive ice sheets, where glacial inception does not occur when expected based on the critical insolation–CO2 relation, due to the lack of such millennial-scale variability (Fig. S8). While the critical-insolation CO2 relation is valid for present-day conditions with respect to temperature and ice volume, future research should extend this framework to account for different states of the Greenland ice sheet and examine when millennial-scale AMOC variability (shaped by atmospheric CO2, insolation, and the configuration of the Greenland ice sheet) leads to glacial inception.

The timing of the next glacial inception strongly depends on the long-term trends in atmospheric CO2 that can result from imbalances between geological sources and sinks of carbon, which remain uncertain. For example, present-day values for silicate weathering and volcanic outgassing, and the response of weathering to climate change, remain poorly constrained45,46,47. Although our model represents global silicate weathering in a way that it acts like a global thermostat, this is an assumption that is still debated42 and alternative hypotheses for stabilizing the long-term climate (e.g., continental uplift) cannot be tested at this time with Earth system models. While it is still uncertain whether the global silicate weathering rate during glacial times was lower than the pre-industrial time37,70,71, we have some confidence that glacial rates were lower due to advancements in Earth system modeling since those early estimates. Though silicate weathering is still considered to be the primary regulator of Earth’s climate on long timescales, it is still not clear if other processes like phosphorus weathering fluxes and organic carbon burial could comparably influence the long-term carbon cycle33,72. As uncertainties in climate sensitivity and in the representation of other carbon cycle processes will also affect the long-term evolution of atmospheric CO2 and the climate34, so too are they expected to influence the timing of the next glaciation.

Methods

Model

We use CLIMBER-X v1.3.073, a fast Earth system model with a comprehensive representation of the global carbon cycle38 and interactive ice sheets74. CLIMBER-X includes the statistical-dynamical semi-empirical atmosphere model SESAM73, the 3D frictional-geostrophic ocean model GOLDSTEIN75,76, the dynamic-thermodynamic sea ice model SISIM73, the land surface and dynamic vegetation model PALADYN77, the biogeochemistry and marine sediments model HAMOCC78,79,80, the ice sheet model SICOPOLIS81, the surface mass balance model SEMIX73, and the viscoelastic solid Earth model VILMA49,82,83. With the exception of SICOPOLIS, SEMIX, and VILMA, all components share a common horizontal grid at 5° × 5° resolution. CLIMBER-X is a fast model and allows to simulate many realizations on long timescales. Currently, it is capable of running up to 10,000 simulation years within a single day, making it highly suitable for deep-past and deep-future Earth system modeling. The detailed carbon cycle representation allows the model to interactively simulate the atmospheric CO2 concentration, and has already been applied to study the climate evolution over the next millennium84, and to assess the sensitivity of the long-term carbon cycle under different cumulative emissions34.

In experiments where we seek to describe NH ice sheets and glacial inception, we enable SICOPOLIS v5.1, VILMA, and SEMIX. SICOPOLIS uses a shallow-ice/shallow-shelf approximation for grounded and floating ice and is used to simulate NH ice sheets with a horizontal resolution of 32 km. The surface mass balance of the ice sheets is computed using the physically-based surface energy and mass balance interface SEMIX, as described in detail in Willeit et al.74. The viscoelastic solid Earth model VILMA accounts for changes via GIA, controlling surface displacement and sea-level. All experiments are run using the 3D mantle viscosity structure described in Bagge et al.49. With interactive ice sheets, CLIMBER-X has been applied to study the future evolution of the Greenland ice sheet64,85 and glacial inceptions31, demonstrating that the model effectively replicates the last glacial inception, whilst simulating no inception during the Holocene74 (see also Fig. S9).

Our study strongly relies on the silicate weathering scheme implemented in CLIMBER-X, which is dependent on both temperature and runoff, and has been shown to realistically reproduce the present-day global silicate weathering rate38. It incorporates 14 lithological classes from the GLiM lithological map (the highest resolution map available), represented as fractional areas within a given grid cell, each characterized by its own activation energy and weathering rate84,86. The formulation implicitly assumes a silicate weathering “thermostat,” as the weathering rate follows an Arrhenius-style equation which takes the form \({F}_{sil}\propto {e}^{\frac{(T-{T}_{0})}{T\cdot {T}_{0}}}{R}_{off}\), where Fsil is silicate weathering rate (TmolC yr−1), T is temperature (K), T0 is the reference (i.e., pre-industrial) temperature, and Roff is annual runoff (kg m−2 yr−1). In CLIMBER-X, silicate weathering increases with rising temperature and runoff (proportional to precipitation through soil infiltration and drainage, which increases with temperature34). Likewise, under colder and drier climates, such as those during the last glacial maximum, the model produces lower silicate weathering rates (Figs. S10 and S11). Therefore, our silicate weathering formulation is based on the assumption that both temperature and runoff influence weathering rates, with runoff increases in a warming climate contributing comparably to temperature to the total weathering increase, see Fig. E6 in ref. 34. Although it is unclear how exactly silicate weathering depends on these factors (and potentially others, such as soil erosion and primary production), the silicate weathering thermostat remains the leading assumption for Earth system models. The relationship between silicate weathering and temperature in CLIMBER-X is similar to those used in other studies (see Kaufhold et al.34 for a comparison).

Not only is the silicate weathering scheme in CLIMBER-X considerably more advanced than that used in previous studies on this topic (e.g., with CLIMBER-2), but CLIMBER-X is a substantial advancement in terms of model complexity. Beyond its higher spatial resolution and spatially explicit weathering scheme, it has a much more detailed representation of the climate and carbon cycle. Further information can be found in refs. 38,73. In contrast to previous studies on the long-term future evolution and timing of the next glacial cycle, this study specifically explores a wider range of cumulative emission scenarios and employs a fully coupled model. This coupling is especially important, as it accounts for potential feedback between the carbon cycle and ice sheets from present day until glacial inception. This work is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to present the spatial extent and size of future ice sheets, discuss the long-term balance of geological sources and sinks, and focus on how millennial-scale AMOC variability can influence the timing of glacial inception.

Initialization of the carbon cycle

Since the carbon fluxes due to weathering are interactively computed in CLIMBER-X, a proper value of volcanic outgassing can be chosen to guarantee a balance of the carbon cycle with atmospheric CO2 under any boundary conditions. The balance of the long-term carbon cycle necessitates volcanic outgassing to compensate for one-half the consumption of atmospheric CO2 via silicate weathering (see section S1.1 for further details). In one experimental configuration, we assume that the pre-industrial (PI) carbon cycle is balanced, and therefore, volcanic outgassing was set to half the global silicate weathering rate at pre-industrial. This value, taken from the 100,000-year spin-up procedure as described in Willeit et al.38, corresponds to 0.0706 PgC yr−1 (Fig. S10), and ensures that the atmospheric CO2 is in equilibrium under pre-industrial conditions37,38. The estimated pre-industrial silicate weathering rate (0.1413 PgC yr−1) falls within observational estimates71,87,88,89, but is notably higher than those found in previous studies on the long-term evolution of CO233,61. While this choice of model initialization is important to “close” the carbon cycle and is commonly adopted in studies examining the long-term climate-carbon cycle response to anthropogenic emissions, it may not be appropriate for modeling of carbon cycle (or glacial cycles) on orbital timescales.

Since no considerable long-term climate drift was observed during the past ~1 million years, we postulate that volcanic outgassing must offset half the average CO2 consumption rate by silicate weathering during the last glacial cycle (LGC). This was determined by using the simulated silicate weathering rates at the pre-industrial, described above, and determining the silicate weathering rate at the last glacial maximum (LGM) (Fig. S10). By running an equilibrium experiment under LGM conditions for 10 kyr, we determined that a rate of 0.0402 PgC yr−1 (corresponding to half the global silicate weathering rate calculated by CLIMBER-X at LGM, Fig. S10) would maintain atmospheric CO2 in equilibrium at that time. This value is subject to considerable uncertainty, however, as global weathering rates during the LGM are poorly constrained, and empirical data do not offer a definitive answer as to whether or not weathering was weaker during glacial times45,47. Some evidence suggests that the physical weathering from glaciers and the exposure of continental shelves may have increased weathering71,90,91, but these effects on the global silicate weathering rate are still poorly quantified. Therefore, we proceed with the current understanding that silicate weathering functions as a global thermostat, and that colder and drier conditions (as reported during the LGM) are expected to reduce the global weathering rates45,92.

We then computed an average silicate weathering rate over the LGC from the simulated PI and LGM weathering rates using the Spratt and Lisiecki sea-level stack as scaling factor93 (Fig. S11). We assume that global mean sea-level can be used as a proxy for the broader Earth system state, given that it reflects ice sheet extent, and therefore, varies with key climate variables which drive silicate weathering over glacial–interglacial timescales. In a way, this scaling factor also implicitly accounts for weathering differences from the exposure of continental shelves. This approach allowed us to derive a value that represents the average volcanic outgassing over the LGC (0.0559 PgC yr−1). This value is reasonably close to the corresponding values used by Brovkin et al.43 to simulate the last glacial cycle (0.0660 PgC yr−1), and Ganopolski and Brovkin3 to simulate the last four glacial cycles without a long-term drift (0.0636 PgC yr−1). Furthermore, a ±10% change in prescribed volcanic outgassing has been previously shown to cause nearly a 30 ppm drift in atmospheric CO2 concentration over 100 kyr3 (a pattern also seen in these experiments, Fig. 1). To further validate our choice of volcanic outgassing during the LGC, we conducted an additional transient experiment from −120 kyr BP (before present) to present-day, with prescribed GHGs (from refs. 94,95,96,97) and NH ice sheets (from Ganopolski and Brovkin3). Antarctica was held constant at its present-day state, as it contributed minimally (less than 10%) to sea-level variations during the last glacial cycle98,99,100. This method yielded an average silicate weathering rate over the LGC of 0.1119 PgC yr−1, requiring an average volcanic outgassing over the LGC of 0.5595 PgC yr−1; close to the value derived using sea-level as a scaling factor.

Experiments

Simulations begin from a pre-industrial equilibrium state achieved through a 100,000-year spin-up of the carbon cycle model, detailed by Willeit et al.38. The experimental setup here is largely inherited from Kaufhold et al.34, but now includes evolving orbital parameters (and ice sheets, in select experiments). To investigate the effect of anthropogenic CO2 emissions on the long-term evolution of the climate, we introduce a set of idealized CO2 emission scenarios to create an ensemble with cumulative CO2 emissions ranging from 500 to 5000 PgC. This is done through a Gaussian function over the course of ~200 years (Fig. S12). The upper limit of 5000 PgC has been used in many studies as it broadly represents our maximum estimated fossil fuel reserves101,102. In addition to this, we provide a run with no anthropogenic emissions (0 PgC), which we refer to as the “natural evolution,” i.e., climate evolution without anthropogenic influence.

Experiments were conducted using both the PIeq and LGCeq initializations (with the climate and carbon cycle components enabled) for different emission scenarios. As CLIMBER-X does not resolve synoptic-scale and inter-annual variability in the atmosphere and ocean, we apply Gaussian white noise in the surface ocean freshwater flux (0.50 kg m−2 day−1 amplitude) in the Atlantic (latitudinal belt between 50–80°N) to represent the impact of such variability on the AMOC, as it was shown that this is important to properly represent millennial-scale AMOC variability in the model52,103. Recognizing the critical role of temperature biases in glacial inception modeling, we introduced a 2m temperature bias correction over northern North America in the surface mass balance calculation following the method described in Ganopolski et al.104. The spatial distribution of this bias correction is detailed in Willeit et al.74 (in Fig. B1). As we use the critical insolation–CO2 relation determined in Talento et al.31, we similarly apply a globally uniform temperature offset of −0.5 °C in the surface mass balance scheme. We make the simplification that Antarctica is prescribed by its present-day state in all simulations, assuming that its dynamics will have a negligible impact on summer temperatures over NH land (and therefore, glacial inception).

All experiments in this study run for 200,000 years, although we do not display the evolution of the LGCeq_ice experiment (e.g., in Fig. 3) more than 5 kyr beyond inception, as we are not yet fully confident that the complex carbon cycle response to large-scale glaciation is sufficiently well represented in CLIMBER-X. This will be evaluated in future studies investigating the CO2 response to changes in ice sheets over the last glacial cycle. Some additional experiments were performed to assess the model drift in our experiment, the effect of different noise amplitudes in the surface ocean freshwater flux, and the effect of different noise realizations in the surface ocean freshwater flux (by recalling “random_seed" in FORTRAN). These experiments are shown in the Supplementary (Figs. S6 and S7). To evaluate the sensitivity of the prescribed LGCeq volcanic outgassing and its impact on atmospheric CO2 concentrations on long timescales, we ran a set of experiments that were ±5% and ±10% the LGCeq value only for the natural evolution. A summary of all main and sensitivity experiments is listed in Table S3.

In addition to the suite of long-term future climate simulations, we also performed additional experiments for Marine Isotope Stages 11, 5, and 1 (Holocene) to validate that we can reasonably predict when glacial inception will begin, and demonstrate the model’s ability to simulate past glacial inceptions. As Marine Isotope Stage 11 has a similar orbital configuration to the present-day, and is close to the threshold in the critical insolation–CO2 relation (identified in Fig. 3b in Ganopolski et al.28), it specifically provides a useful test of the model’s capability to replicate past climate behavior and simulate glacial inception. These experiments were run with prescribed GHGs from refs. 94,95,96,97, transient orbital forcing, and interactive ice sheets. The same model configuration as described above was used here. These additional simulations show that the model can successfully reproduce glacial inceptions during Marine Isotope Stages 11 and 5, while not simulating glacial inception under Holocene boundary conditions (Fig. S9). Like in the LGCeq_ice experiments, we find that the timing of rapid ice sheet expansion is ultimately controlled by millennial-scale variability in AMOC. These results demonstrate that the model is able to reproduce the key processes driving past glacial inceptions.

Definition of glacial inception

Studies generally agree that glacial inception is marked by the rapid growth of ice sheets in North America55,57,105,106 and is considered a bifurcation in the climate system6. This latter point is important, as it implies that there is a potential “irreversibility” of glacial inception7. However, this is not easily quantifiable, and only a few studies have attempted to precisely define the onset of glacial inception. In Talento et al.31, they define it as the point at which ice volume exceeds 15 m sle, roughly equivalent to twice the current ice volume of the Greenland ice sheet. Similarly, Bahadory et al.56 use ice volume to define glacial inception, but with a threshold of 24 m sle. Here, we define glacial inception as (1) the rapid expansion of ice sheets, and (2) a doubling of present-day NH ice area (~4.26 × 106 km2). Although we do not simulate the evolution of these ice sheets through a full glacial cycle here, the simulated ice sheets should generally persist through periods of higher insolation, showing the irreversibility from an interglacial to a glacial state. In Fig. 3, ice area and volume are shown in dashed lines for a brief period following inception to highlight this persistence.

Data availability

Data used in this study are archived on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14861208).

Code availability

The CLIMBER-X model is available at https://github.com/cxesmc/climber-x/releases/tag/v1.3.0. For this study, we used the tagged v1.3.0 of the model (last accessed: 27 September 2024).

References

Ganopolski, A. & Calov, R. The role of orbital forcing, carbon dioxide and regolith in 100 kyr glacial cycles. Clim. Past 7, 1415–1425 (2011).

Abe-Ouchi, A. et al. Insolation-driven 100,000-year glacial cycles and hysteresis of ice-sheet volume. Nature 500, 190–193 (2013).

Ganopolski, A. & Brovkin, V. Simulation of climate, ice sheets and CO2 evolution during the last four glacial cycles with an Earth system model of intermediate complexity. Clim. Past 13, 1695–1716 (2017).

Milankovitch, M. Kanon der Erdbestrahlung und seine Anwendung auf das Eiszeitenproblem Vol. 33 (Special Publication 132, Royal Serbian Academy, 1941).

Raymo, M. E. & Huybers, P. Unlocking the mysteries of the Ice Ages. Nature 451, 284–285 (2008).

Calov, R., Ganopolski, A., Claussen, M., Petoukhov, V. & Greve, R. Transient simulation of the last glacial inception. Part I: glacial inception as a bifurcation in the climate system. Clim. Dyn. 24, 545–561 (2005).

Ganopolski, A. Toward generalized Milankovitch theory (GMT). Clim. Past 20, 151–185 (2024).

Ruddiman, W. F. The Anthropogenic greenhouse era began thousands of years ago. Clim. Change 61, 261–293 (2003).

Broecker, W. S. The end of the present interglacial: How and when? Quat. Sci. Rev. 17, 689–694 (1998).

Müller, U. C. & Pross, J. Lesson from the past: present insolation minimum holds potential for glacial inception. Quat. Sci. Rev. 26, 3025–3029 (2007).

Tzedakis, P. C., Channell, J. E. T., Hodell, D. A., Kleiven, H. F. & Skinner, L. C. Determining the natural length of the current interglacial. Nat. Geosci. 5, 138–141 (2012).

Paillard, D. The timing of Pleistocene glaciations from a simple multiple-state climate model. Nature 391, 378–381 (1998).

Berger, A. & Loutre, M. F. An exceptionally long interglacial ahead? Science 297, 1287–1288 (2002).

Berger, A., Loutre, M. F. & Crucifix, M. The Earth’s climate in the next hundred thousand years (100 kyr). Surv. Geophys. 24, 117–138 (2003).

Loutre, M. F. & Berger, A. Marine Isotope Stage 11 as an analogue for the present interglacial. Glob. Planet. Change 36, 209–217 (2003).

Yin, Q. & Berger, A. Interglacial analogues of the Holocene and its natural near future. Quat. Sci. Rev. 120, 28–46 (2015).

Vettoretti, G. & Peltier, W. The impact of insolation, greenhouse gas forcing and ocean circulation changes on glacial inception. Holocene 21, 803–817 (2011).

Barker, S., Lisiecki, L. E., Knorr, G., Nuber, S. & Tzedakis, P. C. Distinct roles for precession, obliquity, and eccentricity in Pleistocene 100-kyr glacial cycles. Science 387, eadp3491 (2025).

Mörner, N.-A. When will the present interglacial end? Quat. Res. 2, 341–349 (1972).

Loutre, M. F. & Berger, A. Future climatic changes: Are we entering an exceptionally long interglacial? Clim. Change 46, 61–90 (2000).

Paillard, D. Glacial cycles: toward a new paradigm. Rev. Geophys. 39, 325–346 (2001).

Archer, D. & Ganopolski, A. A movable trigger: fossil fuel CO2 and the onset of the next glaciation. Geochem. Geophys Geosyst. 6, 1–7 (2005).

Cochelin, A.-S. B., Mysak, L. A. & Wang, Z. Simulation of long-term future climate changes with the green McGill paleoclimate model: the next glacial inception. Clim. Change 79, 381–401 (2006).

Mysak, L. A. Glacial inceptions: past and future. Atmos. Ocean 46, 317–341 (2008).

Crucifix, M. & Rougier, J. On the use of simple dynamical systems for climate predictions. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 174, 11–31 (2009).

Herrero, C., García-Olivares, A. & Pelegrí, J. L. Impact of anthropogenic CO2 on the next glacial cycle. Clim. Change 122, 283–298 (2013).

Haqq-Misra, J. Damping of glacial-interglacial cycles from anthropogenic forcing. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 6, 950–955 (2014).

Ganopolski, A., Winkelmann, R. & Schellnhuber, H. J. Critical insolation–CO2 relation for diagnosing past and future glacial inception. Nature 534, S19–S20 (2016).

Talento, S. & Ganopolski, A. Reduced-complexity model for the impact of anthropogenic CO2 emissions on future glacial cycles. Earth Syst. Dyn. 12, 1275–1293 (2021).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2024. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 17, 965–1039 (2025).

Talento, S., Willeit, M. & Ganopolski, A. New estimation of critical insolation–CO2 relationship for triggering glacial inception. Clim. Past 20, 1349–1364 (2024).

Laskar, J. et al. A long-term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the Earth. Astron. Astrophys. 428, 261–285 (2004).

Lord, N. S., Ridgwell, A., Thorne, M. C. & Lunt, D. J. An impulse response function for the “long tail” of excess atmospheric CO2 in an Earth system model. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 30, 1–17 (2015).

Kaufhold, C., Willeit, M., Liu, B. & Ganopolski, A. Assessing the lifetime of anthropogenic CO2 and its sensitivity to different carbon cycle processes. Biogeosciences 22, 2767–2801 (2025).

Lord, N. S., Lunt, D. & Thorne, M. Modelling changes in climate over the next 1 million years. Technical Report. SKB-TR-19-09. https://www.skb.com/publication/2494175/ (Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB (SKB), 2019).

Liakka, J. et al. Assessing future ice-sheet variability for long-term safety of deep geological repositories. Adv. Geosci. 65, 71–81 (2024).

Munhoven, G. & François, L. M. Glacial-interglacial changes in continental weathering: Possible implications for atmospheric CO2. in Carbon Cycling in the Glacial Ocean: Constraints on the Ocean’s Role in Global Change (eds Zahn, R., Pedersen, T. F., Kaminski, M. A. & Labeyrie, L.) Vol. 17 of NATO ASI Series I: Global Environmental Change, 39–58 (Springer-Verlag, 1994).

Willeit, M. et al. The Earth system model CLIMBER-X v1.0 – Part 2: The global carbon cycle. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 3501–3534 (2023).

Walker, J. C. G., Hays, P. B. & Kasting, J. F. A negative feedback mechanism for the long-term stabilization of Earth’s surface temperature. J. Geophys. Res. 86, 9776–9782 (1981).

Penman, D., Caves Rugenstein, J., Ibarra, D. & Winnick, M. Silicate weathering as a feedback and forcing in Earth’s climate and carbon cycle. Earth Sci. Rev. 209, 1–16 (2020).

Hilton, R. G. Earth’s persistent thermostat. Science 379, 329–330 (2023).

Zeebe, R. E. & Caldeira, K. Close mass balance of long-term carbon fluxes from ice-core CO2 and ocean chemistry records. Nat. Geosci. 1, 312–315 (2008).

Brovkin, V., Ganopolski, A., Archer, D. & Munhoven, G. Glacial CO2 cycle as a succession of key physical and biogeochemical processes. Clim. Past 8, 251–264 (2012).

Willeit, M., Ganopolski, A., Calov, R. & Brovkin, V. Mid-Pleistocene transition in glacial cycles explained by declining CO2 and regolith removal. Sci. Adv. 5, 1–8 (2019).

Foster, G. L. & Vance, D. Negligible glacial–interglacial variation in continental chemical weathering rates. Nature 444, 918–921 (2006).

Hilton, R. & West, A. Mountains, erosion and the carbon cycle. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 284–299 (2020).

Zuo, H. et al. A revised model of global silicate weathering considering the influence of vegetation cover on erosion rate. Geosci. Model Dev. 17, 3949–3974 (2024).

Vavrus, S. J., He, F., Kutzbach, J. E., Ruddiman, W. F. & Tzedakis, P. C. Glacial inception in Marine Isotope Stage 19: an orbital analog for a natural Holocene climate. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–12 (2018).

Bagge, M., Klemann, V., Steinberger, B., Latinović, M. & Thomas, M. Glacial-isostatic adjustment models using geodynamically constrained 3D Earth structures. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 22, 1–21 (2021).

Dansgaard, W. et al. Evidence for general instability of past climate from a 250-kyr ice-core record. Nature 364, 218–220 (1993).

Ganopolski, A. & Rahmstorf, S. Rapid changes of glacial climate simulated in a coupled climate model. Nature 409, 153–158 (2001).

Willeit, M., Ganopolski, A., Edwards, N. R. & Rahmstorf, S. Surface buoyancy control of millennial-scale variations in the Atlantic meridional ocean circulation. Clim. Past 20, 2719–2739 (2024).

Svendsen, J. I. et al. Late Quaternary ice sheet history of northern Eurasia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 1229–1271 (2004).

Lambeck, K. et al. Constraints on the Late Saalian to early Middle Weichselian ice sheet of Eurasia from field data and rebound modelling. Boreas 35, 539–575 (2006).

Batchelor, C. L. et al. The configuration of Northern Hemisphere ice sheets through the Quaternary. Nat. Commun. 10, 3713 (2019).

Bahadory, T., Tarasov, L. & Andres, H. Last glacial inception trajectories for the Northern Hemisphere from coupled ice and climate modelling. Clim. Past 17, 397–418 (2021).

Dalton, A. S., Stokes, C. R. & Batchelor, C. L. Evolution of the Laurentide and Innuitian ice sheets prior to the last glacial maximum (115 ka to 25 ka). Earth Sci. Rev. 224, 103875 (2022).

Archer, D., Kheshgi, H. & Maier-Reimer, E. Multiple timescales for neutralization of fossil fuel CO2. Geophys. Res. Lett. 24, 405–408 (1997).

Archer, D. et al. Atmospheric lifetime of fossil fuel carbon dioxide. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 37, 117–134 (2009).

Andernach, M., Kapsch, M.-L. & Mikolajewicz, U. Impact of Greenland ice sheet disintegration on atmosphere and ocean disentangled. Earth Syst. Dyn. 16, 451–474 (2025).

Uchikawa, J. & Zeebe, R. E. Influence of terrestrial weathering on ocean acidification and the next glacial inception. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, 1–5 (2008).

Robinson, A., Calov, R. & Ganopolski, A. Multistability and critical thresholds of the Greenland ice sheet. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 429–432 (2012).

Bochow, N. et al. Overshooting the critical threshold for the Greenland ice sheet. Nature 622, 528–536 (2023).

Höning, D. et al. Multistability and transient response of the Greenland ice sheet to anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, 1–11 (2023).

Hodell, D. A. et al. A 1.5-million-year record of orbital and millennial climate variability in the North Atlantic. Clim. Past 19, 607–636 (2023).

Timmermann, A., Knies, J., Timm, O. E., Abe-Ouchi, A. & Friedrich, T. Promotion of glacial ice sheet buildup 60-115 kyr B.P. by precessionally paced Northern Hemispheric meltwater pulses. Paleoceanography 25, 1–9 (2010).

Khodri, M. et al. Modelling the climate evolution from the last interglacial to the start of the last glaciation: the role of Arctic ocean freshwater budget. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1–4 (2003).

Yin, Q. Z., Wu, Z. P., Berger, A., Goosse, H. & Hodell, D. Insolation triggered abrupt weakening of Atlantic circulation at the end of interglacials. Science 373, 1035–1040 (2021).

Lofverstrom, M., Thompson, D. M., Otto-Bliesner, B. L. & Brady, E. C. The importance of Canadian Arctic Archipelago gateways for glacial expansion in Scandinavia. Nat. Geosci. 15, 482–488 (2022).

Munhoven, G. & François, L. M. Glacial-interglacial variability of atmospheric CO2 due to changing continental silicate rock weathering: a model study. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 101, 21423–21437 (1996).

Munhoven, G. Glacial–interglacial changes of continental weathering: estimates of the related CO2 and \({{{\rm{HCO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) flux variations and their uncertainties. Glob. Planet. Change 33, 155–176 (2002).

Hülse, D. & Ridgwell, A. Instability in the geological regulation of Earth’s climate. Science 389, eadh7730 (2025).

Willeit, M., Ganopolski, A., Robinson, A. & Edwards, N. R. The Earth system model CLIMBER-X v1.0 – Part 1: Climate model description and validation. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 5905–5948 (2022).

Willeit, M. et al. Glacial inception through rapid ice area increase driven by albedo and vegetation feedbacks. Clim. Past 20, 597–623 (2024).

Edwards, N. R., Willmott, A. J. & Killworth, P. D. On the role of topography and wind stress on the stability of the thermohaline circulation. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 28, 756–778 (1998).

Edwards, N. R. & Marsh, R. Uncertainties due to transport-parameter sensitivity in an efficient 3-D ocean-climate model. Clim. Dyn. 24, 415–433 (2005).

Willeit, M. & Ganopolski, A. PALADYN v1.0, a comprehensive land surface–vegetation–carbon cycle model of intermediate complexity. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3817–3857 (2016).

Heinze, C. & Maier-Reimer, E. The Hamburg oceanic carbon cycle circulation model version “HAMOCC2s" for long time integrations. Technical Report 20 (Deutsches Klimarechenzentrum, Modellbetreuungsgruppe, 1999).

Ilyina, T. et al. The global ocean biogeochemistry model HAMOCC: model architecture and performance as component of the MPI-Earth system model in different CMIP5 experimental realizations. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 5, 287–315 (2013).

Mauritsen, T. et al. Developments in the MPI-M Earth system model version 1.2 (MPI-ESM1.2) and its response to increasing CO2. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 998–1038 (2019).

Greve, R. Application of a polythermal three-dimensional ice sheet model to the Greenland ice sheet: response to steady-state and transient climate scenarios. J. Clim. 10, 901–918 (1997).

Klemann, V., Martinec, Z. & Ivins, E. R. Glacial isostasy and plate motion. J. Geodyn. 46, 95–103 (2008).

Martinec, Z. et al. A benchmark study of numerical implementations of the sea level equation in GIA modelling. Geophys. J. Int. 215, 389–414 (2018).

Kaufhold, C., Willeit, M., Talento, S., Ganopolski, A. & Rockström, J. Interplay between climate and carbon cycle feedbacks could substantially enhance future warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 20, 044027 (2025).

Höning, D., Willeit, M. & Ganopolski, A. Reversibility of Greenland ice sheet mass loss under artificial carbon dioxide removal scenarios. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 1–9 (2024).

Hartmann, J. & Moosdorf, N. The new global lithological map database GLiM: a representation of rock properties at the Earth surface. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 13 (2012).

Meybeck, M. Global chemical weathering of surficial rocks estimated from river dissolved loads. Am. J. Sci. 287, 401–428 (1987).

Gaillardet, J., Dupré, B., Louvat, P. & Allègre, C. Global silicate weathering and CO2 consumption rates deduced from the chemistry of large rivers. Chem. Geol. 159, 3–30 (1999).

Amiotte Suchet, P., Probst, J.-L. & Ludwig, W. Worldwide distribution of continental rock lithology: Implications for the atmospheric/soil CO2 uptake by continental weathering and alkalinity river transport to the oceans. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 17, 1–13 (2003).

Ludwig, W., Amiotte-Suchet, P. & Probst, J.-L. Enhanced chemical weathering of rocks during the last glacial maximum: a sink for atmospheric CO2? Chem. Geol. 159, 147–161 (1999).

Wan, S. et al. Enhanced silicate weathering of tropical shelf sediments exposed during glacial lowstands: a sink for atmospheric CO2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 200, 123–144 (2017).

Goudie, A. S. & Viles, H. A. Weathering and the global carbon cycle: geomorphological perspectives. Earth Sci. Rev. 113, 59–71 (2012).

Spratt, R. M. & Lisiecki, L. E. A late Pleistocene sea level stack. Clim. Past 12, 1079–1092 (2016).

Köhler, P., Nehrbass-Ahles, C., Schmitt, J., Stocker, T. F. & Fischer, H. A 156 kyr smoothed history of the atmospheric greenhouse gases CO2, CH4, and N2O and their radiative forcing. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 363–387 (2017).

Schilt, A. et al. Glacial–interglacial and millennial-scale variations in the atmospheric nitrous oxide concentration during the last 800,000 years. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 182–192 (2010).

Loulergue, L. et al. Orbital and millennial-scale features of atmospheric CH4 over the past 800,000 years. Nature 453, 383–386 (2008).

Lüthi, D. et al. High-resolution carbon dioxide concentration record 650,000–800,000 years before present. Nature 453, 379–382 (2008).

Budd, W. F., Coutts, B. & Warner, R. C. Modelling the Antarctic and Northern Hemisphere ice-sheet changes with global climate through the glacial cycle. Ann. Glaciol. 27, 153–160 (1998).

Albrecht, T., Winkelmann, R. & Levermann, A. Glacial-cycle simulations of the Antarctic ice sheet with the Parallel Ice Sheet Model (PISM) – Part 1: boundary conditions and climatic forcing. Cryosphere 14, 599–632 (2020).

Albrecht, T., Bagge, M. & Klemann, V. Feedback mechanisms controlling Antarctic glacial-cycle dynamics simulated with a coupled ice sheet–solid Earth model. Cryosphere 18, 4233–4255 (2024).

Lal, R. Carbon sequestration. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 363, 815–830 (2008).

McGlade, C. & Ekins, P. The geographical distribution of fossil fuels unused when limiting global warming to 2°C. Nature 517, 187–190 (2015).

Sinet, S., Ashwin, P., von der Heydt, A. S. & Dijkstra, H. A. AMOC stability amid tipping ice sheets: the crucial role of rate and noise. Earth Syst. Dyn. 15, 859–873 (2024).

Ganopolski, A., Calov, R. & Claussen, M. Simulation of the last glacial cycle with a coupled climate ice-sheet model of intermediate complexity. Clim. Past 6, 229–244 (2010).

Lambeck, K. & Chappell, J. Sea level change through the last glacial cycle. Science 292, 679–686 (2001).

Stokes, C. R., Tarasov, L. & Dyke, A. S. Dynamics of the North American Ice Sheet Complex during its inception and build-up to the last glacial maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 50, 86–104 (2012).

Acknowledgements

C.K. is funded by the Bundesgesellschaft für Endlagerung through the URS project (research project no. STAFuE-21-4-Klei). M.W. is supported by the German paleoclimate modeling initiative PalMod (grant nos. 01LP1920B, 01LP1917D, 01LP2305B). G.M. is a Research Associate with the Belgian Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique–FNRS. V.K. is supported by the German paleoclimate modeling initiative PalMod (grant no. 01LP2305A). PalMod is part of the Research for Sustainable Development initiative (FONA) funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). The authors gratefully acknowledge the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, and the Land Brandenburg for supporting this project by providing resources on the high-performance computer system at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.K., M.W., and A.G. conceived the research. C.K. performed the research and prepared the figures. M.W., A.G., G.M., and V.K. supported the interpretation and analysis of the results. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaufhold, C., Willeit, M., Munhoven, G. et al. Timing of a future glaciation in view of anthropogenic climate change. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1016 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02867-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02867-0