Abstract

The shallow portion of megathrusts can exhibit various modes of failure: interseismic creep, triggered afterslip, or rupture during a tsunami(genic) earthquake, resulting in a potential hidden danger to onshore communities. However, determining which mode is likely for a given portion remains challenging due to a lack of near-trench observations and limited resolution in inversion models. Here, we present a new two-step hybrid postseismic modelling approach that integrates the advantages of conventional forward and inverse methods, greatly improving our resolution of afterslip on the fault, viscous strain in the mantle, and the associated mechanical properties of both regions. We apply this approach to image the fault properties and slip evolution of the region surrounding the 2007 Mw 8.4 Bengkulu earthquake, and show how it promoted the subsequent 2010 Mw 7.8 Mentawai tsunami earthquake. Our results indicate that the deeper portion of the 2010 coseismic rupture area is velocity-strengthening, and slipped aseismically following the 2007 event. Upward propagation of this afterslip then loaded the shallow velocity-weakening area of the 2010 rupture, which generated a large tsunami in the Pagai Islands. Our approach affords a powerful tool for assessing the future possibility of tsunami(genic) and other triggered earthquakes in seismic gaps near recent large events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tsunami earthquakes rupture the shallowest portion of global subduction zones with a low rupture velocity1, but excite larger tsunamis than expected from their routine 20-s (Ms) or 1-s (mb) seismic magnitude2,3. These events often rupture a small area on the megathrust with a lower magnitude, which contrast with larger megaquakes that also generate large tsunamis but with a much greater total slip over a large area4,5. Small rupture area with low magnitude ranks tsunami earthquakes as the most efficient tsunamigenic events among all earthquake categories3,6,7.

Tsunami earthquakes spatially inhabit the shallowest part of the megathrust beneath the frontal accretionary prism at the trench1. Such events are rare, until now there are 13 events reported at global subduction zones including 2010 & 2022 Mentawai, 1907 Nias, 2006 Java, 1994 Java, 1947 Hikurangi-Poverty, 1947 Hikurangi-Tokomaru, 1896 Sanriku, 1963 & 1975 Kuril, 1946 Aleutian, 1992 Nicaragua and 1996 Peru3,8,9; but they represent a significant danger to coastal communities as they generate only weak shaking and may not trigger an evacuation as a result10,11,12. Consequently, understanding the seismic and tsunamigenic potential of the shallow megathrust is crucial for accurate hazard assessment and timely early warning in densely populated coastal communities located near global subduction zones3,13. This is particularly the case if the shallow megathrust is progressively loaded by postseismic stress following a large neighboring-downdip earthquake14,15.

Unfortunately, quantifying where and by how much the shallow megathrust is stressed by postseismic processes induced by large downdip earthquakes remains challenging for several reasons. First, the shallow megathrust is often far offshore and thus its motion is poorly sensed by the conventional land-based geodetic-monitoring networks at most subduction zones10,16. Second, the postseismic process is complex due to multiple mechanisms acting in concert that can generate similar displacements at the surface; thus, it is not always possible to uniquely attribute deformation to a particular source17,18,19.

Finally, the observed displacements are traditionally analyzed separately by forward and/or inverse models, both of which have important limitations. In the case of a forward model, an assumed earthquake source geometry is used to predict the postseismic process given a set of assumed mechanisms and mechanical properties of the fault and lithosphere20,21,22. The usefulness of the recovered model is fundamentally limited by the fidelity of these assumptions. In the case of inverse models, seismic and geodetic observations are used to directly infer strain at depth in a kinematic fashion, requiring fewer a priori assumptions but also providing less insight into the physical processes at work15,19,23,24. An effective approach that integrates the merits of these two techniques while avoiding their limitations is therefore needed.

Here, we present a new two-step hybrid method for reconciling geodetic observations with models that combines the forward and inverse methods to take advantage of their relative strengths while minimizing their defects. We demonstrate the method’s application by imaging the postseismic processes following the 2007 Mw 8.4 Bengkulu megathrust event, Sumatra (Fig. 1) in unprecedented detail, and show how a specific pattern of velocity-strengthening (VS) and velocity-weakening (VW) material on the shallow fault likely contributed to the subsequent 2010 Mw 7.8 Mentawai tsunami earthquake10,25,26.

a Coseismic deformation measured by the Sumatran GPS Array (SuGAr) with black vectors showing horizontal and gray vectors showing vertical28. Black contours show the coseismic rupture patch of the 2007 Bengkulu earthquake sequence from ref. 15, dark-reddish contour presents the rupture patch of the 2010 Mw 7.8 Mentawai tsunami earthquake from ref. 37. The red, orange and light-orange stars indicate the hypocenter of the 2007 event, 2010 event and 2008 Mw 7.2 South Pagai earthquake, respectively. Gray dashed line and solid lines show the rupture patch of the 1797 and 1833 earthquake, respectively67. Orange circles show the seismicity following the 2007 event until the 2010 event; the yellow circles show the seismicity between 2005 and 2007. b Postseismic deformation measured by the SuGAr following the 2007 earthquake until the 2010 event. The black, blue and gray horizontal vectors show cumulative displacements in 1 month, 1 year and 3 years, respectively. Red vectors show vertical cumulative postseismic displacements within 3 years. Orange circles are the same aftershocks in (a). QQ’ in (a) is the location of the cross-section view for depth-dependent initial viscosity and strain rate shown in Fig. 5. Seismicity (Mw >2.5) spans from 2000 to 2014 and is retrieved from the USGS catalog. This seismicity is also shown in Figs. 2, 4–6.

Results and discussion

Merging two perspectives

To uncover how and why the postseismic stress changes from the 2007 Bengkulu earthquake might have promoted occurrence of the 2010 Mentawai event, we developed a new method that combines the advantages of the forward and inverse approaches conventionally used in postseismic studies15,20,21,22,23 through a Kalman filter approach27. The method is composed of two steps: we first use coseismic stress changes to generate an initial forward model prediction of afterslip and viscous strain that assumes simple and uniform mechanical parameters for the fault and lithosphere. The initial forward model is governed by simple velocity-strengthening friction on the fault and a Burgers body viscoelastic flow law in the mantle (Methods).

The initial model poorly explains the observed postseismic deformation, so we feed the predicted fault slip and mantle strain as an initial guess to a Kalman filter. The filter adjusts these predictions to better explain the geodetic observations while considering uncertainties in both data and model parameters27 (Methods). The result is a model that explains the data and sidesteps the resolution and smoothing issues faced by a conventional inversion; furthermore, the final model can be used to directly investigate the mechanical properties of the fault and upper mantle19,23.

Synthetic tests of this method with a dense observing network demonstrate that it enables us to reconstruct the patterns of afterslip and viscous strain following a large earthquake far more accurately than conventional methods, even in the case of a highly spatially variable rheologic structure (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 3). Tests using the Sumatran GPS Array (SuGAr) network geometry show that the amplitude of afterslip and strain are recovered best in areas with moderate or good geodetic coverage (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d). The amplitudes of shallow afterslip and viscous strain in the mantle wedge are slightly underestimated due to low data resolution in these areas, but their overall patterns are well determined even with the coarse network (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d). Consequently, the method accurately delineates the afterslip boundary on the fault and locates strain within the mantle, providing a new window into investigations of the physical properties of fault zones.

Imaging afterslip process following the 2007 Bengkulu earthquake sequence

The Mw 8.4 Bengkulu earthquake and its Mw 7.9 & 7.0 aftershocks occurred on 12-13 September, 2007 in West Sumatra, Indonesia (Fig. 1a, b). Within the earthquake rupture region, coral microatolls captured the coseismic offset and the SuGAr recorded both the coseismic and postseismic deformation26,28. The coseismic slip produced seaward motion and uplift of the forearc islands, and subsidence along the Sumatran west coast (Fig. 1a). The postseismic deformation is significantly different, with the majority of the vertical motions reversed (Fig. 1b). Horizontally, the postseismic azimuths are different from those of the coseismic offsets, and also vary significantly with time. The coseismic slip is consistently estimated at depths of ~20–50 km15,25,26,29,30, while postseismic slip may partially overlap the coseismic slip area14,15.

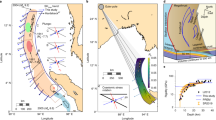

We use a published coseismic slip model15 to provide our initial guess of the Coulomb stress changes on the megathrust due to following reasons (Fig. 2a). First, the coseismic GNSS offsets were retrieved from the catalog that was derived through a self-consistent and comprehensive analysis framework, which assures a higher accuracy in offsets estimates28; second, the model was built assuming a 3D geometry based on the Slab 1.0 model31. In this framework, the joint inversion with the coral microatoll data likely estimates a coseismic slip model that should be closer to the actual slip that occurred during the earthquake. While this model as with others15,25,26,32 suffers the loose constraints in the southern portion of rupture patch due to lack of forearc island chain, which could introduce some uncertainties in the slip, resulting in inaccuracy in stress changes that predict poorly fits with the postseismic time series by using forward models. These uncertainties, in fact, offer a great opportunity to test our new approach. The slip model yields a stress increase surrounding the rupture patch and stress decrease within the rupture area, with high-amplitude stress concentrations west of Pagai, mostly updip and downdip of the high slip zones. These high stress regions correlate with most of the early aftershocks on the fault. From 2007 to 2010, the aftershocks migrate in space and time with some penetrating into the coseismic rupture area (Fig. 2a, b). A notable feature is that a group of aftershocks located in the stress concentration area west of Pagai migrate up-dip toward the hypocenter of the 2010 Mentawai earthquake (i.e., dark green to dark purple), illuminating how the pattern of stress-driven afterslip33,34 propagated following the 2007 Bengkulu event (Fig. 2a, b).

a The coseismic stress changes induced by the 2007 Mw 8.4 Bengkulu earthquake15. b The estimated 3-year cumulative afterslip on the megathrust with small gray vectors indicating the direction. White vectors show the 3-year cumulative horizontal displacements measured by the SuGAr, and black vectors show the model predictions. Colored circles show seismicity between 2007 and 2011 from the USGS catalog. Rest of rupture patches, vertical vectors in (a) and hypocenter of earthquakes (stars) are the same as in Fig. 1.

We apply our two-step method to analyze the postseismic deformation following the 2007 Bengkulu earthquake leading up to the 2010 Mentawai event. We first conducted a series of model runs to fit the postseismic time series as well as possible through model parameters tuning (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5) to derive a forward model solution for time-dependent fault slip and strain driven by the coseismic stress changes from our input coseismic model15 (Fig. 2a). Although it still poorly fits with the rapid deformation at the early stage and amplitudes at many stations, it offers a sufficient solution for next step (best model in Supplementary Figs. 4, 5). We then use these solutions as an initial guess for the Kalman filter, which adjusts the slip and strain patterns to better fit with the SuGAr time series, while considering the data and model uncertainties (Methods).

To gain a comprehensive understanding about how coseismic slip uncertainties affect the resultant afterslip and frictional properties on the megathrust, we further conducted series of experimental tests. There are some available coseismic slip models for the 2007 Bengkulu event. We selected several typical well-established slip models that are constrained by both geodetic and seismic data26, geodetic data15 and geodetic joint with tsunami waveforms32, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6). The tests demonstrate that the afterslip and its associated frictional-property estimates are largely similar both in amplitude and pattern except for some local detailed differences that are due to stress changes as the result of geometry differences and lack of sufficient GNSS sites (Supplementary Figs. 6–8). In summary, we conclude that the similar afterslip and frictional property pattern are robust feature, and we select the coseismic model from ref. 15 for the postseismic modelling due to its good fits with data, and its compatible 3D fault geometry with ours (Supplementary Figs. 6, 7a, 9 and 10).

Our final afterslip estimates are shown in Fig. 2b. In general, the afterslip surrounds the rupture patch in response to the coseismic stress changes. The afterslip distribution is broadly consistent with previous studies but differs in certain details of the spatial pattern14,15,23. We attribute such differences to the higher fidelity of our approach since we use the same SuGAr data and similar fault geometry. Unlike most previous models, our results match the SuGAr time series well for the whole postseismic period considered (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Figs. 9, 10), while forwards do not adequately fit with the time series (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5).

Anatomy of surface deformation contributed by afterslip and viscous flow mechanisms

Our method allows us to disentangle the contributions to postseismic deformation arising from fault slip and viscous strain in the oceanic and continental mantle (Fig. 3). In general, the filtered slip and strain predict a similar surface deformation pattern to that predicted by the forward model (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 11). Yet, the amplitude of surface deformation from the afterslip is larger than that predicted by the forward model, while that from the continental mantle is smaller (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 11c, d). Overall, the deformation caused by afterslip surpasses that caused by viscous flow in the mantle, but both are required to generate the observed postseismic deformation (Figs. 2b and 3e and Supplementary Figs. 9, 10, 11e).

a Slip and strain in view of 3D geometry of the fault and oceanic and continental mantle. Colors on the fault show the estimated 3-year cumulative afterslip, and on the strain volumes show the estimated 3-year cumulative strain amplitude. Stars indicate the hypocenter of the 2007 and 2010 event as shown in Fig. 1a, b. b–d The 3-year cumulative postseismic surface deformation that was caused by the oceanic mantle, continental mantle and afterslip, respectively. White vectors show the 3-year horizontal cumulative postseismic displacements measured by the SuGAr, and black vectors present the model predictions. Colored circles present the 3-year cumulative vertical postseismic displacements measured by the SuGAr with the background image showing the model predictions. e The predicted total surface deformation from afterslip and viscous flow in the mantle.

Deciphering the fault frictional properties and viscosity of the mantle

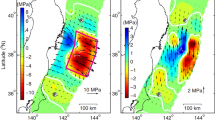

Following ref. 19, we use our modeled afterslip to estimate the frictional properties of the fault assuming it obeys a rate- and state-dependent frictional law20,35 (Methods). Our results indicate that the fault is characterized by a heterogeneous distribution of frictional properties (Fig. 4a) similar to those that controlled the 2010 Mw 8.8 Maule earthquake in Chile19. Although highly variable, the derived frictional properties explain independent observations remarkably well. Almost all the precisely-relocated aftershocks36 and aftershocks from USGS occurred in velocity-weakening regions, with only a small portion in velocity-strengthening or velocity-neutral areas, which may be driven by propagation of the afterslip around small velocity-weakening patches that are too small to image (Fig. 4a). Further, we note that large coseismic slip tends to occur in strongly velocity-weakening areas while moderate coseismic slip tends to occur in velocity-neutral or nearly velocity-neutral areas (Fig. 4a, b). Related to this observation, the southern deep portion of the 2010 rupture is characterized by velocity-strengthening friction and slipped moderately (~2–4 m) during the 2010 earthquake, whereas the shallow portion that slipped heavily (>5 m) and excited large tsunamis at Pagai37 is characterized by velocity-weakening friction (Fig. 4a). The shallow velocity-weakening region extends further north along the trench until the southern tip of Siberut but does not extend south toward Enggano, where the shallow portion of the megathrust is velocity-strengthening. A patchy distribution of frictional properties along a fault, as observed here, results in mutual compensation of coseismic and postseismic slip and suggests potential locations of future seismicity (Fig. 4a). This finding is the quantitative manifestation of the depth-dependent rupture model5,38, and indicates that the shallow megathrust has along-strike variations in frictional properties that could be used to anticipate future slip modes along megathrusts globally.

a Estimated velocity-weakening (blue) and velocity-strengthening (red) frictional properties on the megathrust. Colored circles with black outlines present the seismicity (Mw > 2.5) as shown in Fig. 2. Colored circles with white outlines represent the relocated seismicity (Mw ≥ 5.0) spanning from 1990 to 2017 studied by ref. 36. Black and dark-reddish contours show the 2007 and 2010 earthquake rupture patches, respectively, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Colored stars indicate the hypocenter of these two earthquakes as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Light-gray contours and numbers present the slab depths from Slab 268. Siberut, Sipora and Pagai are forearc islands. b Depth-averaged afterslip, coseismic slip and frictional properties on the megathrust. The pink shaded area indicates the range of frictional properties at each depth. The range of frictional properties explains well the seismicity profile along depth as shown in (c). Seismicity is shown in (a). The VS and VW represents velocity-weakening and velocity-strengthening friction, respectively. The SW and UW stands for stable-weakening and unstable-weakening friction, respectively. See UW and SW definitions in frictional properties section in Methods.

We also use our derived volumetric strain rates to estimate the initial viscosity for the oceanic and continental mantle (Methods). Figure 5 shows depth-dependent features along a cross-section through the maximum slip region of the 2007 earthquake. We obtain localized strain rates and thus viscosity variations that are significantly different from the uniform values often assumed in forward models, a surprising result that is well resolved by our data assimilation procedure (Supplementary Figs. 1–3). For instance, along the forearc island chain and coastal region, the deformation is primarily driven by afterslip and strain within the oceanic mantle (Fig. 5a). Meanwhile, strain rates within the continental mantle wedge are high, but contribute a much broader pattern of deformation with lower amplitude (Figs. 3c and 5b). Still, a weak and deformable mantle wedge is needed to compensate for the oceanic mantle and afterslip to explain the small uplift along the coastal area (Figs. 3b–e and 5a). In general, we find that the continental mantle is at least one order of magnitude weaker than the oceanic mantle, with the highest strain rates corresponding to the mantle wedge where slab dehydration and fluid release are observed at global subduction zones19,39 (Fig. 5).

a White vectors show 3-year cumulative postseismic displacements, red vectors show the afterslip contribution and blue vectors show the viscous flow contribution. Gray upright triangles mark the location of SuGAr network. Colored blocks present the estimated initial viscosity in the oceanic and continental mantle. A similar setup shown in (b) but presents the estimated initial strain rate in the mantle. Light-gray contours show coseismic stress (MPa) with a 0.02 interval in the continental mantle and a 0.05 interval in the oceanic mantle. The light-white dashed lines indicate the resolution value of each block with a 0.02 interval in the continental mantle and a 0.1 interval in the oceanic mantle. Colored circles show seismicity (Mw > 2.5) as those shown in Figs. 2 and 4. Location of QQ’ is shown in Fig. 1a.

Stress-driven and frictional-property-shaped aftershock behaviors

The postseismic stress map (Fig. 6a) indicates that a majority of aftershocks, especially those within or surrounding the 2007 rupture patch, likely occurred in response to stress loading imparted by propagation of afterslip on the fault (Figs. 2a and 6). Surprisingly, much of the deep portion of the 2010 rupture patch close to its hypocenter experienced a net stress release from afterslip (blue areas in Fig. 6), though this area experienced coseismic stress loading from the 2007 event (red areas in Fig. 2a). Our results suggest that afterslip in this region propagated progressively up-dip to load the shallow patch at the trench, accompanied by a migration of seismicity (Fig. 6).

Postseismic Coulomb stress characteristics on the megathrust. Black and pink stars show the 2007 Mw 8.4 Bengkulu and 2010 Mw 7.8 Mentawai earthquake, respectively. The orange contour presents the rupture patch of the 2007 event as shown in Figs. 1 and 2; the pinkish contours show the coseismic slip with a 2-m interval of the 2010 event as shown in Fig. 4a. Circles show aftershocks (Mw > 2.5) color-coded by time as shown in Figs. 1, 2 and 4, previously. Circles with light-pink outlines show relocated aftershocks after the 2007 event from ref. 36. Inset shows postseismic Coulomb stress at the large coseismic slip area of the 2010 event (two markers).

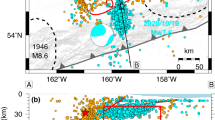

The occurrence of deep slip and aftershocks following the 2010 event (blue dots in Fig. 6) within the velocity-strengthening area inferred by our model (Fig. 4a) is more difficult to explain40. The rate-and-state friction model predicts seismic events can nucleate only on faults with velocity-weakening friction, while in velocity-strengthening regions the fault should creep aseismically41,42. However, in addition to hosting aftershocks, this area experienced afterslip from 2007 to 2010, and then slipped coseismically during the 2010 event. This behavior is similar to what was observed in the Nias segment where a large portion of the shallow megathrust slipped both during the 1907 Mw 7.8 tsunami earthquake43 and during afterslip following the downdip 2005 Mw 8.6 earthquake34,44 (Fig. 7). If the rate-and-state frictional model still applies in these places, we hypothesize that there may exist a distribution of smaller velocity-weakening asperities within this zone that are not resolvable by the geodetic data, but which could cause the apparent overlap between the two modes of slip. In this case, the region could undergo interseismic or postseismic creep but would remain partly kinematically coupled, with some slip deficit available for release during the 2010 event16.

Black stars with white outlines show Mw >7 seismicity after the 2007 event until May of 2023 from USGS catalog. White stars with black outlines show the same relocated aftershocks in Figs. 4 and 6 from ref. 36. The shaded-black area in the north in Nias section shows the shallow megathrust area that slipped coseismically in 1907 Mw 8.2 tsunami earthquake43 and experienced afterslip following the 2005 Mw 8.6 Nias-Simeulue earthquake34,44.

Frictional property implications for future shallow tsunami(genic) earthquakes

In the area of the 2010 Mentawai tsunami earthquake, our results contrast with the widely accepted notion that the shallow megathrust is velocity-strengthening45,46. We observe regions of both stable and unstable frictional properties within the rupture area (Figs. 4a and 7). The deeper velocity-strengthening region allowed up-dip propagation of afterslip which progressively stressed the shallow velocity-weakening area and promoted its ultimate rupture. This pattern of paired velocity-weakening and velocity-strengthening friction likely made the Mentawai tsunami earthquake possible.

A similar pattern of alternating frictional properties exists near Sipora island in our model (Figs. 4a and 7) just up-dip of the famous Mentawai seismic gap47. In comparison between this patch and that holds the 2010 Mentawai tsunami earthquake, the surface geomorphology, fault structure, fluid content and low friction are very similar3,48,49. As a result, this patch holds the ingredients and now is stressed for a potential future afterslip-triggered tsunami earthquake similar to the 2010 event (Fig. 6). On the other hand, it could also potentially rupture together with the deeper locked patches in a great earthquake, which would likely be tsunamigenic as well3,48. The question of which type is more likely may be addressable via dynamic modelling50,51 using our map of fault friction (Fig. 7) as an input. In either case, our results suggest this area could pose a large tsunami potential48 to the populous city of Padang (Figs. 4a and 6).

South of the 2010 slip patch and updip of the 2007 main rupture at the shallow trench, we obtain VS frictional properties that contrast to the patch that was slipped heavily during the 2010 Mentawai event (Figs. 4a and 7). The VS patch primarily conveys the afterslip following the 2007 Bengkulu earthquake as the response of the stress changes (Fig. 2a). Unfortunately, there are no GNSS stations offshore to constrain both the afterslip amplitude and pattern, and thus the likely mechanical properties. Future seafloor geodetic measurements will provide key constraints to resolve this uncertainty. Structurally, on the other hand, the data demonstrate that the faults & folds system in the accretionary wedge are quite similar to that of the shallow megathrust that held the 2010 Mentawai tsunami earthquake3,52, consequently, it has a possibility to rupture similarly as a tsunami earthquake52. Indeed, a tsunami earthquake with Mw 7.3 recently occurred within this segment in 20228, suggesting that a small patch with VW frictional property here is highly possible and a waking of follow up ruptures in the remaining shallow megathrust may have started.

More broadly, in following work, our hybrid forward-inverse method provides a blueprint for mapping the shallow frictional properties of a megathrust, and the underlying viscous properties of the mantle, and is ready to be applied to recent large earthquakes such as the 2014 Mw 8.3 Iquique earthquake in northern Chile, the 2020 Mw 7.6, 7.8, and 2021 Mw 8.2 rupture sequence in Alaska53,54,55,56, and the 2022 Mw 7.6 Michoacan earthquake in Mexico57 subduction zones. The stress changes induced by these earthquakes provide a unique opportunity to probe the shallow properties of the megathrust and to assess the likelihood of future tsunami(genic) earthquakes nearby.

Methods

GNSS data

The Sumatran subduction zone has developed a forearc-island chain over the seismogenic zone, on which the Sumatran GPS Array (SuGAr) is located. The unique island chain enables geodetic observations very close to the megathrust and allows us to clearly see how the fault slips throughout the seismic cycle23,58,59. These GNSS daily solutions were processed and modeled with technique details given in ref. 28. The modeled coseismic offsets, interseismic trend, annual and semi-annual seasonal signals were removed from the original GNSS time series, isolating the postseismic deformation time series. Such postseismic time series have been used to study postseismic deformation processes following great earthquakes throughout the Sumatran subduction zone15,20,23. Here, we use the same postseismic time series to study the detailed postseismic-deformation processes of the 2007 Mw 8.4 Bengkulu earthquake (Fig. 1).

Two-step hybrid postseismic modelling: a new approach

We desire to combine the merits of both stress-driven forward model and inversion approaches while suppressing their defects to efficiently and accurately model postseismic deformation. In our previous work, we find that Kalman filter is powerful to invert the postseismic deformation time series for afterslip on the megathrust and viscous strain in the mantle wedge of the Sumatran subduction zone23. We therefore developed a new Kalman filter-based method composed of two steps. First, we run a friction-based postseismic forward model that is driven by coseismic stress changes. This forward model provides a coarse prediction of kinematic model parameters (i.e., fault slip and mantle viscous strain) that poorly fits with postseismic time series. We then use this forward solution as an initial guess for the predictions in a Kalman filter (Eq. (4), ref. 27). The filter modifies these predictions to better explain the observation while simultaneously considering uncertainties of the data and model parameters (Eqs. (3) and (5))23,60. In doing so, the forward solution is adjusted as needed to fit the data without being heavily limited by the resolution and smoothing issues faced by a conventional inversion, enabling us to better resolve the spatially heterogeneous nature of the physical properties in the fault zone.

This method sidesteps the most difficult problem in forward models of postseismic deformation, namely the need to specify the initial stress conditions which contain unknown coseismic and background stress components. The coseismic stress changes may be relatively well-determined by coseismic slip studies but still contain moderate uncertainties. In contrast, the background stress is usually poorly known or completely unknown, yet is very important especially when modelling spatiotemporally clustered events35. Such unknown initial stresses together with uncertainties in the background rheology structure typically result in forward models poorly fitting the data35. This limitation is neatly avoided in our approach by the second filtering step, which modulates the forward prediction to better explain the data while simultaneously deriving a more accurate model of the initial conditions and rheologic properties of the fault zone. Of course, the more data sets we have in the fault zone, the better these model parameters are constrained. At global subduction zones, majority of places are lack of forearc islands chain, therefore, the hybrid method has limits to resolve the afterslip updip of the seismogenic zone. However, in places where the seafloor geodetic observational system is well established at the shallow trench e.g., Japan, Cascadia and also on continents where land-based measurements are made available, the method has a large potential to gain useful insights into the mechanical properties of rocks in the fault zone.

The Kalman filter is defined as follows:

Where \(k\) is the current time epoch, \({x}_{k}\) is the model parameters (i.e., slip and viscous strain), \({F}_{k-1}\) is the system or transition matrix; \({\omega }_{k-1}\) and \({\gamma }_{k-1}\) are white noise processes, zero-mean, uncorrelated, and have known covariance matrix \({Q}_{k}\), \({R}_{k}\), respectively. \({H}_{k}\) represents the measurement matrix, \({y}_{k}\) represents the available measurements (i.e., GNSS, InSAR or other postseismic displacements) at time epoch \(k\). \({P}_{k-1}^{+}\) represents the measurement-updated covariance matrix of the model parameters at time step \(k-1\), \({P}_{k}^{-1}\) is the covariance matrix prediction for time step \(k\), \({x}_{k-1}^{+}\) is the filtered model parameters at time step \(k-1\), \({x}_{k}^{-}\) is the predicted model parameters at time step k, \({x}_{k}^{+}\) is the measurement-updated model parameter estimates at time step \(k\). During the update step, we regularize the strain similarly as in previous studies19,23.

Synthetic tests

We conducted a series of synthetic experiments to validate this method. Instead of using a simplified setting that fails to represent the complex nature of typical subduction zones, we used the setting of the 2007 Mw 8.4 Bengkulu rupture segment in the Sumatran subduction zone for all the synthetic tests. We created synthetic surface displacements predicted by forward models using spatially variable rate-strengthening frictional properties, defined as follows:

Where \(v\) represents slip rate on the fault; \({v}_{0}\) is the reference slip rate; \(\Delta \tau\) presents the stress perturbation due to the earthquake, which is slowly relaxed during postseismic process; \(\left(a-b\right)\) is the frictional properties of the fault; \(\sigma\) is the effective normal stress20,21. The mantle lithosphere obeys a viscoelastic Burgers rheology below the elastic layer22,61.

The synthetic displacements, slip and strain are used for filtering and comparison in the following experimental tests. The first test involves a dense synthetic network that contains 113 GNSS stations (~120 km interval). The results show that the method excellently reconciles the postseismic deformation pattern (e.g., directions and amplitudes), afterslip on the fault and viscous strain in the mantle (Supplementary Fig. 1). In contrast, a typical forward model fails to reconcile the afterslip on the megathrust, resulting in underestimates of slip amplitudes and thus moment magnitude (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In the second test, we used the actual SuGAr network, including 18 stations along the 2007 Bengkulu rupture segment (Supplementary Fig. 2). In general, our model reconciles the displacements, slip and strain remarkably well at places where the displacements are large and the GNSS stations are relatively dense. At other places with limited station density, the shallow afterslip and viscous strains near the trench and deep in the lithosphere are slightly underestimated in amplitude (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d). These underestimated signals are either too far or too deep to be felt by the SuGAr stations, but could be captured by the filter with the noise model, thus producing limited and minor opposite displacements due to viscous flow in the oceanic mantle. In addition, the boundary effect of the strain volume mesh at the trench (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figs. 1a–3a) also contributes some opposite motions due to viscous flow in the oceanic mantle (Supplementary Fig. 11a). But fortunately, they produce tiny surface displacements that only introduce minor trade-offs between afterslip and viscous flow by increasing subtle levels of slip magnitude at the bottom of the fault in between Sipora and Pagai (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d). Consequently, except for such minor underestimates, the spatial location of the afterslip and viscous strain are well delineated on the megathrust and placed in the mantle, respectively. In contrast, the conventional forward model can estimate the spatial pattern fairly well, but largely underestimates of the afterslip magnitude, resulting in poor fits to data and a lower moment magnitude (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b, e, f).

In the final test, we introduce a challenge by adding a localized weak zone with low viscosity downdip of the fault in the mantle wedge. Our results show that the new method fits the data well and can remarkably reconcile both the amplitude and spatial pattern of slip and strain with minor underestimates in amplitude at places where the data are relatively sparse (Supplementary Fig. 3a–d). Conversely, the forward model again fails to reconstruct the heterogenous pattern in both slip and strain, with significant underestimates of both slip and strain, resulting in poor fits to the data (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b, e, f). In summary, we conclude that the new method is powerful and able to accurately delineate both the afterslip boundaries on the fault and place the strain in the mantle at the right locations. This approach provides a new window into previously unresolvable patterns of spatiotemporal postseismic deformation and the frictional properties, stress evolution, and heterogeneous material properties of the crust and lithosphere.

Application to observed GNSS data

Following the synthetic tests, we apply the method to the observed SuGAr postseismic deformation time series to uncover the nature of the afterslip on the megathrust and viscous strain in the mantle at the Mentawai segment of the Sumatran subduction zone following the 2007 Mw 8.4 Bengkulu earthquake. We used a well-defined coseismic slip model constrained by joint inversion of GNSS and coral microatoll data15 to calculate the initial stress changes (Fig. 2a) for driving the postseismic process using Unicycle17,62. The afterslip is assumed to obey a rate-strengthening frictional law (Eq. (6))20,21,63,64, and the viscous flow in the mantle is assumed to obey a flow law with the Burgers rheology22,61, using uniform parameters as in the synthetic case. During model runs, we first fixed the frictional properties (Supplementary Figs. S4, S5, model 1), and then tuned the viscosity of the Burgers body to fit with the postseismic time series measured by the far-field JMBI and NTUS stations, as they were mainly affected by the viscoelastic deformation; we then fixed the Burgers body, and tuned the frictional properties to fit with all the time series as well as possible; we stopped tuning the frictional properties (Supplementary Figs. S4, S5, best model) if further tune on frictional properties will overestimate the displacements field (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5, model 2). We then used the final-tuned forward-model solution (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5, best model) as the initial guess in the Kalman filter prediction step. The filter updates these solutions to fit the SuGAr postseismic time series. Our filtered afterslip model is shown in Figs. 2b and 3a, and viscous strain is shown in Fig. 3a, respectively. The method results in a reasonable model solution which matches the SuGAr time series very well for the whole time period considered in the modelling (Supplementary Figs. 9, 10). The results indicate that the edges of the region which slipped coseismically in 2007 continue to slip moderately (Fig. 2b), indicating that the typical assumption that the coseismic slip region should not be allowed to undergo afterslip fails in this case. Further test shows that if the coseismic slipped region is fixed to not slip postseismically, the afterslip amplitude is overestimated to poorly fits with the postseismic time series (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Frictional properties

We estimate the frictional properties on the megathrust fault following ref. 19. In this case, the afterslip obeys the rate-and-sate frictional law under steady state as follows.

Where \(\Delta {CFS}\) stands for the Coulomb stress changes on the creeping fault element; \(V\) presents the steady-state sliding rate; \({\sigma }_{n}\) is the effective normal stress; \(\left(a-b\right)\) is the rate-and-state frictional properties on the fault and defines the fault behavior. If \(\left(a-b\right) > 0\), the fault material is velocity-strengthening and slides stably and aseismically (i.e., creep and afterslip). Conversely, if \(\left(a-b\right) < 0\), the fault is characterized by velocity-weakening friction (VW) and potentially seismic (i.e., frictional instabilities may nucleate). A VW condition on the fault is necessary for earthquake nucleation; however, it is insufficient to fully predict slip behaviors because a VW material can slip stably (i.e., no earthquake nucleation) under certain circumstances, instead demonstrating complex characteristics i.e., low-frequency earthquakes, slow-slip events and participation in coseismic slip that initiates elsewhere65. We refer to such material as stable weakening (SW) and for material that is both VW and unstable as unstable weakening (UW)19.

Initial viscosity

The new method allows the model to match the data well for the whole time period of the SuGAr data (Supplementary Figs. 9, 10). In particular, the early rapid deformation curvature is well captured by our model, which allows a precise estimation of the large strain rate immediately after the earthquake. We use the coseismic stress (\(\Delta \tau\)) (Fig. 2a) divided by the initial strain rate (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\)) (Fig. 5b) for calculating the initial viscosity \(\eta =\frac{\Delta \tau }{\dot{\varepsilon }}\) and show the depth-dependent viscosity in cross-section through the slip maximum of the 2007 Bengkulu event in Fig. 5a.

Data availability

All the daily RINEX files of SuGAr network analyzed in this paper are included and can be downloaded from ftp://eos.ntu.edu.sg/SugarData.

Code availability

Unicycle software used for forward prediction of the fault slip and strain is available at https://bitbucket.org/sbarbot/unicycle. All figures were prepared using version 6.3.0 of Generic Mapping Tools66, available at https://docs.generic-mapping-tools.org.

Change history

24 January 2026

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03133-z

References

Kanamori, H. Mechanism of tsunami earthquakes. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 6, 346–359 (1972).

Kanamori, H. & Kikuchi, M. The 1992 Nicaragua earthquake: a slow tsunami earthquake associated with subducted sediments. Nature 361, 714–716 (1993).

Qiu, Q. & Barbot, S. Tsunami excitation in the outer wedge of global subduction zones. Earth Sci. Rev. 230, 104054 (2022).

Ye, L., Kanamori, H. & Lay, T. Global variations of large megathrust earthquake rupture characteristics. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao4915 (2018).

Lay, T. The surge of great earthquakes from 2004 to 2014. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 409, 133–146 (2015).

Riquelme, S. & Fuentes, M. Tsunami efficiency due to very slow earthquakes. Seismological Res. Lett. 92, 2998–3006 (2021).

Kajiura, K. Leading Wave of a Tsunami. Bulletin Earth- quake Research Institute, Tokyo University, Vol.41, 535–571. References (Scientific Research Publishing, 1963). https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=36910.

Xia, T. et al. The 2022 MW 7.3 Southern Sumatra Tsunami earthquake: rupture up-dip of the 2007 MW 8.4 Bengkulu event. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 129, e2024JB030284 (2024).

Geersen, J. Sediment-starved trenches and rough subducting plates are conducive to tsunami earthquakes. Tectonophysics 762, 28–44 (2019).

Hill, E. M. et al. The 2010 M w 7.8 Mentawai earthquake: very shallow source of a rare tsunami earthquake determined from tsunami field survey and near-field GPS data. J. Geophys. Res. 117, B06402 (2012).

Nye, T., Sahakian, V. & Melgar, D. Modeling ground motions and crustal deformation from tsunami earthquakes: Rupture parameter constraints from the 2010 Mentawai event. Seismica 3, 1152 (2024).

Sahakian, V. J., Melgar, D. & Muzli, M. Weak near-field behavior of a tsunami earthquake: toward real-time identification for local warning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 9519–9528 (2019).

Mori, N. et al. Giant tsunami monitoring, early warning and hazard assessment. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00327-3 (2022).

Lubis, A. M., Hashima, A. & Sato, T. Analysis of afterslip distribution following the 2007 September 12 southern Sumatra earthquake using poroelastic and viscoelastic media. Geophys. J. Int. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggs020 (2012).

Tsang, L. L. H. et al. Afterslip following the 2007 Mw 8.4 Bengkulu earthquake in Sumatra loaded the 2010 Mw 7.8 Mentawai tsunami earthquake rupture zone. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 121, 9034–9049 (2016).

Lindsey, E. O. et al. Slip rate deficit and earthquake potential on shallow megathrusts. Nat. Geosci. 14, 321–326 (2021).

Shi, Q. et al. Structural control and system-level behavior of the seismic cycle at the Nankai Trough. Earth Planets Space 72, 343–353 (2020).

Barbot, S. Asthenosphere flow modulated by megathrust earthquake cycles. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL078197 (2018).

Weiss, J. R. et al. Illuminating subduction zone rheological properties in the wake of a giant earthquake. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax6720 (2019).

Masuti, S., Barbot, S. D., Karato, S., Feng, L. & Banerjee, P. Upper-mantle water stratification inferred from observations of the 2012 Indian Ocean earthquake. Nature 538, 373–377 (2016).

Barbot, S., Lapusta, N. & Avouac, J.-P. Under the hood of the earthquake machine: toward predictive modeling of the seismic cycle. Science 336, 707–710 (2012).

Hu, Y. et al. Asthenosphere rheology inferred from observations of the 2012 Indian Ocean earthquake. Nature 538, 368–372 (2016).

Qiu, Q. et al. Transient rheology of the Sumatran mantle wedge revealed by a decade of great earthquakes. Nat. Commun. 9, 995 (2018).

Tang, C.-H., Hsu, Y.-J., Barbot, S., Moore, J. D. P. & Chang, W.-L. Lower-crustal rheology and thermal gradient in the Taiwan orogenic belt illuminated by the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav3287 (2019).

Zheng, Z., Jin, S. & Fan, L. Co-seismic deformation following the 2007 Bengkulu earthquake constrained by GRACE and GPS observations. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 280, 20–31 (2018).

Konca, A. O. et al. Partial rupture of a locked patch of the Sumatra megathrust during the 2007 earthquake sequence. Nature 456, 631–635 (2008).

Kalman, R. E. A new approach to linear filtering and prediction problems. J. Basic Eng. 82, 35–45 (1960).

Feng, L. et al. A unified GPS-based earthquake catalog for the Sumatran plate boundary between 2002 and 2013. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 3566–3598 (2015).

Fujii, Y. & Satake, K. Tsunami waveform inversion of the 2007 Bengkulu, southern Sumatra, earthquake. Earth Planets Space 60, 993–998 (2008).

Lorito, S., Romano, F., Piatanesi, A. & Boschi, E. Source process of the September 12, 2007, MW 8.4 southern Sumatra earthquake from tsunami tide gauge record inversion. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L02310 (2008).

Hayes, G. P., Wald, D. J. & Johnson, R. L. Slab1.0: A three-dimensional model of global subduction zone geometries. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 117, B01302 (2012).

Gusman, A. R., Tanioka, Y., Kobayashi, T., Latief, H. & Pandoe, W. Slip distribution of the 2007 Bengkulu earthquake inferred from tsunami waveforms and InSAR data. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 115, B12316 (2010).

Peng, Z. & Zhao, P. Migration of early aftershocks following the 2004 Parkfield earthquake. Nat. Geosci. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo697 (2009).

Hsu, Y.-J. et al. Frictional afterslip following the 2005 Nias-Simeulue earthquake, Sumatra. Science 312, 1921–1926 (2006).

Feng, L. et al. Footprints of past earthquakes revealed in the afterslip of the 2010 Mw 7.8 Mentawai tsunami earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 9518–9526 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Plate interface geometry complexity and persistent heterogenous coupling revealed by a high-resolution earthquake focal mechanism catalog in Mentawai, Sumatra. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 637, 118726 (2024).

Yue, H. et al. Validation of linearity assumptions for using tsunami waveforms in joint inversion of kinematic rupture models: application to the 2010 Mentawai Mw 7.8 tsunami earthquake. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 1728–1747 (2015).

Lay, T. et al. Depth-varying rupture properties of subduction zone megathrust faults. J. Geophys. Res. 117, B04311 (2012).

Luo, H. & Wang, K. Postseismic geodetic signature of cold forearc mantle in subduction zones. Nat. Geosci. 14, 104–109 (2021).

Johnson, K. M., Fukuda, J. & Segall, P. Challenging the rate-state asperity model: afterslip following the 2011 M9 Tohoku-oki, Japan, earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L20302 (2012).

Dieterich, J. H. Modeling of rock friction: 1. Experimental results and constitutive equations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 84, 2161–2168 (1979).

Ruina, A. Slip instability and state variable friction law. J. Geophys. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB088iB12p10359 (1983).

Martin, S. S. et al. Reassessment of the 1907 Sumatra “Tsunami Earthquake” based on macroseismic, seismological, and Tsunami observations, and modeling. Pure Appl. Geophys. 176, 2831–2868 (2019).

Qiu, Q., Feng, L., Hermawan, I. & Hill, E. M. Coseismic and postseismic slip of the 2005 M w 8.6 Nias-Simeulue Earthquake: spatial overlap and localized viscoelastic flow. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 124, 7445–7460 (2019).

Byrne, D. E., Sykes, L. R. & Davis, D. M. Great thrust earthquakes and aseismic slip along the plate boundary of the Makran subduction zone. J. Geophys. Res. 97, 449–478 (1992).

Wang, K. & Hu, Y. Accretionary prisms in subduction earthquake cycles: the theory of dynamic Coulomb wedge. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 111, B06410 (2006).

Sieh, K. et al. Earthquake supercycles inferred from sea-level changes recorded in the corals of west Sumatra. Science 322, 1674–1678 (2008).

Qin, Y. & Singh, S. C. Insight into frontal seismogenic zone in the mentawai locked region from seismic full waveform inversion of ultralong offset streamer data. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 4342–4365 (2018).

Bradley, K. et al. Stratigraphic control of frontal décollement level and structural vergence and implications for tsunamigenic earthquake hazard in Sumatra, Indonesia. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 1646–1664 (2019).

Qiu, Q. et al. The mechanism of partial rupture of a locked megathrust: the role of fault morphology. Geology 44, 875–878 (2016).

Noda, H. & Lapusta, N. Stable creeping fault segments can become destructive as a result of dynamic weakening. Nature 493, 518–521 (2013).

Qin, Y. et al. Assessing the risk of potential tsunamigenic earthquakes in the Mentawai region by seismic imaging, central Sumatra. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 25, e2023GC011149 (2024).

Zhao, B. et al. Aseismic slip and recent ruptures of persistent asperities along the Alaska-Aleutian subduction zone. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–12 (2022).

Crowell, B. W. & Melgar, D. Slipping the Shumagin gap: a kinematic coseismic and early afterslip model of the Mw 7.8 Simeonof Island, Alaska, earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090308 (2020).

Liu, C., Lay, T. & Xiong, X. The 29 July 2021 MW 8.2 Chignik, Alaska Peninsula earthquake rupture inferred from seismic and geodetic observations: re-rupture of the Western 2/3 of the 1938 rupture zone. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL096004 (2022).

Qiu, Q., Li, L., Yang, X., Lin, J. & Chua, C. T. Morphological differences across the Shumagin-Semidi fault segments control slip behaviors and tsunami genesis in the Aleutian-Alaska subduction zone. Quaternary Sci. Adv. 15, 100215 (2024).

Liu, C., Lay, T., Bai, Y., He, P. & Xiong, X. Coseismic slip model of the 19 September 2022 Mw 7.6 Michoacán, Mexico, earthquake: a quasi-repeat of the 1973 Mw 7.6 rupture. Seismic Rec. 3, 57–68 (2023).

Chlieh, M., Avouac, J. P., Sieh, K., Natawidjaja, D. H. & Galetzka, J. Heterogeneous coupling of the Sumatran megathrust constrained by geodetic and paleogeodetic measurements. J. Geophys. Res. 113, 1–31 (2008).

Konca, A. O. et al. Rupture kinematics of the 2005 Mw 8.6 Nias? Simeulue Earthquake from the joint inversion of seismic and geodetic data. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 97, S307–S322 (2007).

Segall, P. & Matthews, M. Time dependent inversion of geodetic data. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 102, 22391–22409 (1997).

Pollitz, F. F., Bürgmann, R. & Banerjee, P. Post-seismic relaxation following the great 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake on a compressible self-gravitating Earth. Geophys. J. Int 167, 397–420 (2006).

Barbot, S. Frictional and structural controls of seismic super-cycles at the Japan trench. Earth Planets Space 72, 1–25 (2020).

Kano, M., Miyazaki, S., Ishikawa, Y. & Hirahara, K. Adjoint-based direct data assimilation of GNSS time series for optimizing frictional parameters and predicting postseismic deformation following the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake. Earth Planets Space 72, 159 (2020).

Fukuda, J. & Johnson, K. M. Bayesian inversion for a stress-driven model of afterslip and viscoelastic relaxation: method and application to postseismic deformation following the 2011 MW 9.0 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2020JB021620 (2021).

Barbot, S. Slow-slip, slow earthquakes, period-two cycles, full and partial ruptures, and deterministic chaos in a single asperity fault. Tectonophysics 768, 228171 (2019).

Wessel, P., Smith, W. H. F., Scharroo, R., Luis, J. & Wobbe, F. Generic mapping tools: improved version released. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 94, 409–410 (2013).

Natawidjaja, D. H. et al. Source parameters of the great Sumatran megathrust earthquakes of 1797 and 1833 inferred from coral microatolls. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 111, B06403 (2006).

Hayes, G. P. et al. Slab2, a comprehensive subduction zone geometry model. Science 362, 58–61 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by China-Pakistan Joint Research Center on Earth Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences and by grants from the Key Talents Project of Guangdong Province (2024TX08A214), National Natural Science Foundation of China (42076059), Guangdong Province Introduced Innovative R&D Team of Big Data-Mathematical Earth Sciences and Extreme Geological Events Team (2021ZT09H399) and Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (No. SML2024SP031 and No. SML2024SP010) and Chinese Academy of Sciences (Y4SL021001). We are very grateful for the creative comments and suggestions from all the reviewers. We thank Editors Mara Monica Tiberti, Joe Aslin and Aliénor Lavergne for handling our manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Q. designed the study and developed the two-step postseismic modelling method for the study. L.F. processed the GPS data. Q.Q. conducted the data analysis and created the figures. Q.Q. wrote the initial manuscript and E.O.L., L.F., L.L., P.Z. and J.L. all revised and jointly wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Thorne Lay and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Mara Monica Tiberti, Joe Aslin and Aliénor Lavergne. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, Q., Lindsey, E., Feng, L. et al. Tsunamigenic earthquake at the Sunda trench promoted by aseismic slip after a previous megathrust event. Commun Earth Environ 6, 888 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02873-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02873-2