Abstract

Deforestation is an important driver of regional climate change in the Amazon; thus, assessments of climate impacts from deforestation can provide key insights to climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in the region. Using satellite-based observational data, here we investigated how accumulated deforestation in the Amazon may have contributed to shifting climate away from reference conditions in highly forested regions. We assessed differences in several essential climate variables between 0.5° deforested cells grouped by their extent of remaining forest cover and their highly forested neighboring cells. Our findings show compelling evidence that forest loss has contributed to shift climate toward higher land surface temperatures, lower evapotranspiration, lower dry season rainfall, and fewer rainy days, especially in regions with forest cover <60%. Highly deforested regions share some climatic similarities with transitional regions between the moist forest and savanna biomes, which was generally not observed in highly forested regions. Our findings underscore the importance of deforestation control and forest restoration to improve climate resilience of Amazonian ecosystems and climate-dependent economic activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The climate crisis is unequivocal and has been leading to uneven impacts among different regions of the globe. The Amazon, which contains the largest tropical forest area in the world, is projected to experience some of the highest increases in heat extremes and decreases in soil moisture1. The region also faces some of the world’s highest projected risks regarding species losses driven by surface warming, as well as threats to human health driven by heat-humidity-related illnesses1. Regional changes in the Amazon climate can be driven not only by the global increase of atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases but also by extensive and ongoing deforestation2,3. Since 1985, the Amazon rainforest has lost approximately 11% (~59 Mha) of its forest cover to anthropogenic land uses (based on data from MapBiomas Amazonia Collection 6), with more than 0.5 Mha cleared annually over more recent years4.

The conversion of extensive forest areas to pasturelands or croplands in the Amazon, which is also common in many other tropical regions, alters land surface properties such as reducing leaf area index (LAI), rooting depth, and surface roughness5. The long-lasting modification of these land surface properties due to forest loss at the regional level affects land-atmosphere interactions over time, contributing to regional changes in climate5. Land surface warming and changes in rainfall regimes stand out as major climate impacts of deforestation6,7,8,9,10 that can amplify ongoing impacts caused by global climate change11.

However, deforestation-induced effects on climate may depend on several factors that remain open for investigation, including the scale of observation, seasonality, and the intensity of forest loss in terms of extent or rate. For instance, studies point to different effects of deforestation on rainfall at the mesoscale (~200 × 200 km or less). Increased rainfall over small-scale deforested areas is suggested to occur due to changes in mesoscale circulations, such as the vegetation breeze process12,13,14. This effect has been identified for all seasons, and while most studies imply more pronounced deforestation-induced rainfall increases in the dry season and dry-to-wet season transition14,15,16, a predominant effect in the wet season has been recently suggested at spatial resolutions of up to 60 km17. As the extent of the deforested area increases, rainfall can be redistributed to decrease in the interior of deforested regions and increase over the nonforest side near forest edges in the prevailing wind direction15,18. However, rainfall reductions due to deforestation have also been detected with resolutions ranging from 0.05°(~5.5 km) to 1000 km at all seasonal periods, with greater reductions as spatial resolution decreases up to a certain threshold10,17. Results, however, still diverge on the seasonal impacts and the spatial resolution in which rainfall changes are more pronouncedly detected8,10,11,17,19,20. Even non-significant relationships between deforestation and rainfall have been found for resolutions of 50 km or smaller6,21. Moreover, deforestation has been suggested to negatively impact rainfall seasonality, such as by delaying wet season onset and increasing the occurrence of long dry spells22,23.

Most of the science about Amazon deforestation's impacts on climate comes from modeling studies, and their importance is unquestionable24,25. However, large-scale observational studies remain limited in number, despite their key contribution to the representation of land-atmosphere interactions in models, a process that still holds substantial uncertainties. The idea of tipping points or ecosystem transitions in the Amazon26 is another highly debated scientific topic based mainly on modeling studies27,28,29,30,31, with fewer contributions focusing on observations32,33,34. With recent substantial advancements in remote sensing-based products and data availability, observational studies currently have a strong potential to provide robust assessments on deforestation-driven shifts in the climate of forest systems, considering that many areas in the Amazon have already experienced extensive forest loss. The few studies of this type that examined the Amazon using remote sensing-derived products used variable approaches, including different spatial resolutions and climate variables, as well as distinct methods to assess deforestation-climate relationships. This stresses the importance of additional observational evidence on the impacts of deforestation on climate, which can help to assess the consistency of previous evidence and provide additional insights that can guide effective forest-based solutions for climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Here, we use a comprehensive observational approach that analyzes the potential impact of Amazon deforestation on regional climate shifts by integrating different essential climate variables, seasonal periods, and extent of accumulated deforestation. We divided the Amazon territory into grid cells of 0.5° spatial resolution, a scale at which additional evidence is needed for deforestation-induced effects on rainfall, land surface temperature (LST), and evapotranspiration (ET). For each grid cell, we calculated descriptive statistics of satellite-based LST, ET, and rainfall in three time periods: annual, wet season (three consecutive wettest months in each cell), and dry season (three consecutive driest months in each cell), plus two climate variables related to rainfall seasonality: maximum dry spell duration (consecutive days with rainfall <1 mm) and number of rainy days (rainfall ≥1 mm), totaling eleven climate variables. To the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive set of variables tested for the impact of deforestation on the Amazon climate.

Our approach compares the climate averages during 2013–2021 across a gradient of deforested cells against their highly forested neighboring cells (>80% forest cover), which served as our reference for climate conditions minimally affected by accumulated deforestation. In contrast, other observational studies have usually assessed how changes in climate between two time intervals diverge between deforested cells and control neighbors6,10. By comparing deforested and forested neighbors by their climate averages in the same time interval, we aim to evaluate whether accumulated deforestation in the long-term shifts the climate away from the reference condition of highly forested regions. Furthermore, by comparing climate differences between deforested and forested neighboring cells against those from forested cells neighboring each other, we assess if climate differences related to deforestation are larger than those potentially related to confounding factors. The comparison of climate averages also allows us to evaluate if climate characteristics in deforested regions have shifted to a point that could support ecosystem transitions. To do so, we compared climate envelopes (the distribution of climate averages among our samples) of highly deforested regions against the envelope of highly forested regions, savannas, and forest-savanna transitions within the Amazon.

Results

The impact of accumulated deforestation in the Amazon on the regional climate

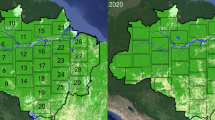

The selection of deforested cells to be compared against reference neighbors comprised areas within the moist forest biome domain with a remaining forest cover in 2021 <80%, whereas forest cover in reference cells was >80%. We grouped deforested cells by their extent of remaining forest cover in 2021, as follows: ≤40%, 40–60%, and 60–80% remaining forest cover. Our sample selection contained only deforested cells that were touching boundaries with reference cells within a 3 × 3 window and vice versa, assuming these geographically close areas share similar climate backgrounds. Additionally, we ensured deforested and reference cells had nearly unaltered forest cover during the 2013–2021 period, to highlight the role of historic deforestation, and also pairs of deforested and reference neighboring cells shared the same Köppen climate zone. The final selection of grid cells for this analysis is shown on the map of Fig. 1.

All these grid cells are entirely within the moist forest biome, had negligible forest loss over 2013–2021, and were grouped by their percentage of remaining forest cover in 2021 (≤40%, 40–60%, or 60–80% for deforested cells, and forest cover >80% for reference cells). The distribution of climate differences between deforested cells from each deforestation group versus reference neighboring cells was compared against the distribution of climate differences between reference versus reference neighboring cells, as also exemplified in the right panel. Reference cells in faded green were additionally used in a second assessment to generate, over the entire study region, 1000 random samples of 150 pairs of climate differences between reference versus reference neighbors. The original distribution of climate differences between deforested and reference neighbors was then compared against each of the 1000 distributions of random reference versus reference neighbors to assess the consistency of patterns from statistical tests. Ocean and terrain basemaps were obtained from Natural Earth.

For each selected pair of deforested versus reference neighboring cells, we computed their differences in the average of climate variables during 2013–2021. Subsequently, we compared the distribution of these differences with that of reference versus reference neighboring cells. While the distribution of climate differences between deforested versus reference neighbors is assumed to have a major influence of accumulated forest loss, the distribution of climate differences between reference versus reference neighbors is assumed to have a major influence of background factors other than deforestation. We only selected pairs of reference versus reference neighbors in which the difference in their forest cover was negative or equal to zero, since forest cover differences between deforested versus reference neighbors were necessarily negative (lower forest cover in the deforested cell). The average difference in forest cover between reference versus reference neighbors was −7 percentage points (pp), and reached an average of −62 pp for our most deforested group (forest cover ≤40%) versus reference.

Differences in land surface temperature (LST) between reference versus reference neighboring cells had a balanced distribution of positive and negative values (Fig. 2), with a median difference of +0.27 °C in the dry season. The distribution of differences between deforested versus reference cells, however, shows a larger proportion of positive values (higher LST in the deforested cells), with a median of +1.14 °C in the dry season, reaching values of +4 °C or greater for the most deforested group (≤40% forest cover). Likewise, evapotranspiration (ET) in all periods showed more negative differences as the remaining forest decreased, indicating lower ET in deforested regions compared to the reference. The median difference of ET in the dry season for comparisons between deforested cells with forest cover ≤40% versus reference was −45 mm, in contrast to −4.7 mm for the reference versus reference comparisons.

Deforested grid cells are grouped by the percentage of remaining forest cover in 2021: ≤40%, 40–60%, or 60–80% forest cover. Forest cover in reference cells is >80%. The comparison of reference versus reference neighboring cells (in dark green) is also displayed to represent climate differences mainly influenced by factors other than deforestation. Negative (positive) differences indicate lower (greater) climate averages compared to reference neighboring cells. LST stands for land surface temperature, ET for evapotranspiration, and Max. for maximum. Vertical lines from left to right indicate, respectively, the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentile values. Number of pairwise comparisons: 17 for ≤40% forest cover versus reference, 30 for 40–60% forest cover versus reference, 163 for 60–80% forest cover versus reference, and 148 for reference versus reference.

For the dry season rainfall, a higher frequency of negative differences (lower rainfall) was found for deforested versus reference comparisons, especially for the deforestation groups with ≤40% or 40–60% forest cover. For instance, the proportion of comparisons with negative differences in dry season rainfall gradually increased from 53% in reference versus reference, to 59% in deforested cells with 60–80% forest cover versus reference, 63% in cells with 40–60% forest cover versus reference, and 82% in cells with forest cover ≤40% versus reference. Additionally, a higher frequency of negative differences in the number of rainy days (i.e., fewer rainy days) was found for deforested cells with forest cover ≤40% or 40–60% versus reference. The median difference for these deforestation groups against reference ranged from −8 to −11 days, in contrast to −1 day for reference versus reference comparisons.

We tested if the distribution of climate differences between deforested versus reference neighbors showed significant differences against the distribution observed between reference versus reference neighbors, based on the Two-Sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test at the 0.05 level. We found significant differences for most climate variables and deforestation groups against reference (Supplementary Table 1), except for the annual and wet season rainfall, in which all or most deforestation groups showed non-significant differences. For the wet season ET, dry season ET, maximum dry spell duration, and the number of rainy days, significant differences were only found for the deforested groups with ≤40% or 40–60% forest cover. Similar patterns were found with the Welch’s t-test for differences in the mean of distributions (Supplementary Table 1), including significant differences at the 0.05 level in all deforestation groups for the dry season rainfall and the number of rainy days, and non-significant differences in all groups for the maximum dry spell duration.

To further evaluate the consistency of our statistical comparisons, we extended our spatial representation of climate differences related to factors other than deforestation by resampling reference versus reference comparisons across the whole study area. We selected reference cells that were neighboring each other but not necessarily neighboring deforested cells (the set of dark green and faded green cells in Fig. 1), deriving one thousand random subsamples of 150 pairwise comparisons between reference versus reference neighbors. We then reapplied the statistical tests to compare the distribution of climate differences between deforested versus reference neighbors against the distribution of each reference versus reference subsample, computing the 95% confidence interval of p-values for these one thousand comparisons. Statistical tests with this approach were mostly in line with the significant differences found in previous comparisons (Supplementary Table 1), but diverged mainly by indicating significant differences in dry season rainfall only for the most deforested group (forest cover ≤40%), and additional significant differences in dry season ET for the group with 60–80% forest cover.

Differences between deforested versus reference neighboring cells for LST and ET significantly increased in intensity according to the accumulated deforested area, considering both absolute (Supplementary Fig. 1) and relative climate differences (Fig. 3). Absolute climate differences for dry season rainfall were not significantly different among deforestation groups, based on the Welch’s t-test at the 0.05 level, but the deforestation group with 60–80% forest cover was significantly different from the others when considering relative differences. Differences for ET, rainfall, and the number of rainy days had a larger dispersion from the mean for deforested cells with 60–80% forest cover versus reference neighbors (Fig. 3), showing more extreme positive and negative differences against reference neighbors.

Values indicate the percentage difference in climate averages during 2013–2021 between deforested cells against their reference neighboring cells. Deforested cells were grouped by their remaining forest cover in 2021. Forest cover in reference cells was >80%. Upper and lower boundaries of each box indicate the third and first quartiles of the distributions. Horizontal lines indicate the median, and cross marks the mean. Points show values beyond the first and third quartiles. Letters at the bottom represent the comparison among deforestation groups based on pairwise Welch’s t-test at the 0.05 level. LST stands for land surface temperature, ET for evapotranspiration, and Max. for maximum. Number of pairwise differences: 17 for ≤40% forest cover versus reference, 30 for 40–60% forest cover versus reference, and 163 for 60–80% forest cover versus reference.

The time series from which climate averages were computed (2013–2021) includes two years with extreme drought conditions in the Amazon, 2015 and 2016, mainly driven by the El Niño and anomalous warming in the North Atlantic Ocean35,36,37. To ensure that larger climate differences between deforested versus reference cells, compared to reference versus reference cells, were not biased by interannual climate variability, we reapplied the original comparisons of climate differences for two additional time intervals: the average of extreme drought years (2015 and 2016) and non-drought years (2013 and 2018). The years of 2013 and 2018 were chosen as a control against drought years for presenting some of the lowest proportions of water deficit anomalies in the Amazon since 201336.

Results from KS and Welch’s t-tests for extreme drought and non-drought years showed very similar patterns when these two intervals are compared against each other, or compared with the whole time series (Supplementary Table 2), including significant differences at the 0.05 level in dry season rainfall and the number of rainy days for most deforestation groups. Extreme drought years most remarkably diverged from the other periods by presenting non-significant differences in dry season rainfall in the deforestation group with 60–80% forest cover. We also compared these different time intervals in terms of the magnitude of climate differences in the same deforestation group versus reference comparisons (Supplementary Fig. 2). Non-significant differences at the 0.01 level were found with this method within all deforestation groups and for all climate variables based on Welch’s t-test, indicating similarities in the mean intensity of climate differences between deforested versus reference neighbors. Altogether, these findings converge to indicate that climate differences between deforested and reference regions, including those related to dry season rainfall and the number of rainy days, show a consistent link to deforestation and not a bias associated with extreme drought periods included in our dataset.

Among our samples, there is a wide amplitude of differences in forest cover between deforested and reference neighboring cells, which contributes to the observed variation of magnitude in climate differences (as illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3). To normalize estimates of deforestation impacts on climate among our samples, we divided each climate difference between deforested versus reference neighbors by their corresponding difference in forest cover. Additionally, to further minimize the influence of factors other than deforestation in these estimates, we removed outliers, averaged climate differences from the same deforested cell versus its reference neighbors, and averaged climate differences among our samples (see “Methods” section for additional detail). We assumed this central value is more likely linked to deforestation, while values dispersed from the mean have a greater influence of background factors. We did not estimate the impacts on annual and wet season rainfall, in addition to maximum dry spell duration, due to the unclear evidence of deforestation contribution to changes in these variables.

Our normalized estimates for deforestation impacts on climate (Table 1) represent the likely shift in the average of climate variables from the climate conditions of reference regions, for every 1 percentage point (pp) loss in forest cover. Deforestation impacts in the dry season indicate a mean LST increase of +0.05 °C (95% CI 0.04–0.06) per pp reduction in forest cover, while ET shows a mean reduction of −0.14 mm month−1 ([95% CI −0.23 to −0.06 mm] or −0.15% [−0.25 to −0.06%]), and rainfall show a mean reduction −0.37 mm month−1 ([95% CI −0.56 to −0.18 mm] or −0.41% [−0.59 −to −0.23%]) per pp reduction in forest cover (Table 1). Moreover, our findings indicate a mean reduction of −0.23 rainy days ([95% CI −0.31 to −0.14 days] or −0.18% [−0.24 to −0.11%]) per pp reduction in forest cover. The 95% confidence interval of our estimates shows a large variation in the range of values that would represent the actual mean deforestation impacts on ET and rainfall. Nonetheless, the range of values for annual and dry season ET, dry season rainfall, and the number of rainy days agree in their negative sign, emphasizing that deforestation is associated with reductions in these variables.

Similarities in climate patterns between highly deforested regions and forest-savanna transitional regions

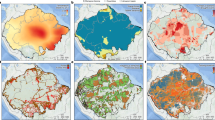

In light of the observed significant impact of accumulated deforestation on climate in the Amazon, we evaluated whether the distribution of climate averages in highly deforested regions has shifted towards climatic characteristics of savannas or forest-savanna transitional regions. From our original selection of deforested grid cells, all within the moist forest biome, we selected for this current analysis the cells with forest cover <60% to be considered as our highly deforested regions. In addition, all their immediate reference neighbors were selected as our highly forested regions (forest cover >80%), representative of the climate characteristics of the moist forest biome under minimal influence of deforestation. Different biome types, such as open grasslands and wooded savannas, also occur within the Amazon boundaries38,39. We selected grid cells from the savanna biome and grid cells in transitional regions between savannas and moist forests to compare their 2013–2021 climate averages with those of highly deforested and forested cells.

Regions from the moist forest biome that are highly forested show very distinct climate characteristics from savannas within the Amazon, with significantly different distributions at the 0.05 level for all climate variables, based on the Two-Sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, except for wet season ET and maximum dry spell duration. They also show significant differences from the distributions in forest-savanna transitional regions. However, in highly deforested regions, distributions for LST variables and annual ET are significantly similar to transitional regions (Table 2). Additionally, highly deforested regions have non-significant differences for dry season ET and rainfall compared to both highly forested regions and transitional regions, showing mean values in between these two biome categories.

Although the annual rainfall and the number of rainy days in highly deforested regions are not significantly different from highly forested regions, there is a notable shift towards lower values (Fig. 4). During the dry season, LST in highly deforested regions is on average 3 °C higher than in highly forested regions but 3 °C lower than in savannas. In addition, the average dry season ET is 12% lower (−40 mm) than in highly forested regions, but 44% greater (+92 mm) than in savannas, whereas dry season rainfall is 25% (−50 mm) lower than in highly forested regions but 60% greater (+56 mm) than in savannas. Moreover, the number of rainy days in highly deforested regions is, on average, about 11 days lower than in highly forested regions, but 24 days greater than in savannas.

The x-axis shows the range of climate averages in the Amazon for each biome category, and the y-axis indicates the proportion of samples whose climate average is less than or equal to a given value on the x-axis. Horizontal dashed lines mark the value on the x-axis at which 50% of samples in each biome category fall below. Both highly forested and deforested regions represent grid cells from the moist forest biome but diverge by having, respectively, >80% and <60% remaining forest cover in 2021. LST stands for land surface temperature, ET for evapotranspiration, and Max. for maximum. The map on the bottom right shows all grid cells selected for the analysis. The number of selected cells for each biome category was 27 for highly deforested regions, 38 for highly forested regions, 126 for forest-savanna transitional regions, and 41 for savannas.

To further evaluate deforestation-related shifts in climate envelopes, we compared the selected highly deforested and forested cells in terms of their conformance with the climate envelope of savannas. We identified the climate envelope in which most savannas in the Amazon are found based on the observed 5th and 95th percentiles of climate averages from the selected cells of this biome (Table 2). For instance, most Amazonian savannas occur where the dry season LST is ≥31 °C, dry season ET is ≤309 mm, and dry season rainfall is ≤192 mm (Table 2). For each climate variable, we then assessed the proportion (%) of cells from highly deforested and forested regions that are within the savanna envelope. This analysis revealed that about 93% of our highly deforested cells were in the savanna envelope for dry season LST (Supplementary Table 3); however, a large proportion of highly forested cells (68%) were also under this envelope. More remarkably, about 67% of highly deforested cells were under the envelope for annual LST, in contrast to only 16% in highly forested cells. The vast majority of highly deforested regions are also in the savanna envelope for annual ET (78% of cells against 45% in highly forested cells) and dry season rainfall (70% against 55%), while the dry season ET and wet season rainfall also showed substantial contrasts between deforested and forested cells.

We also mapped the spatial distribution of areas across the Amazon from the moist forest biome whose climate is under the envelope for savannas. This analysis was performed for four variables (annual LST, annual ET, wet and dry season rainfall) and by distinguishing moist forest areas by their forest cover extent (Fig. 5). Areas in which the four variables are in the savanna envelope, thus showing the largest similarity to the savanna climate, are found in the Brazilian states of Rondônia and mid-eastern Pará. The vast majority of these areas are highly deforested (<60% forest cover), contrasting with the highly forested areas in their surroundings that show less similarity with the savanna envelope. Other regions in which deforested areas show a greater climate similarity to savannas are found in northern Mato Grosso state in Brazil, southern Pará, and in the western Colombian Amazon. When each climate variable is analyzed separately (right panel in Fig. 5), we observed that most of the southern Amazon is under the savanna envelope for dry season rainfall, and a large portion of the western Amazon is under the envelope for annual ET and wet season rainfall. Conversely, annual LST and ET show greater spatial distinctions between highly deforested and forest areas, especially in the eastern and southern Amazon.

All cells in gray are entirely within the moist forest biome in the Amazon. The darker the shade of gray in a given cell, the more climate variables whose values are within thresholds found in Amazonian savannas (varying from zero to four variables). Climate average thresholds for which savannas in the Amazon are found were defined as follows: annual land surface temperature (LST) ≥ 32 °C, annual evapotranspiration (ET) ≤ 1189 mm, wet season rainfall ≤972 mm, and dry season rainfall ≤192 mm. Wet and dry seasons are considered, respectively, the three consecutive wettest and driest months based on rainfall climatology. Contoured deforested grid cells were grouped by their remaining forest cover in 2021 (≤40%, 40–60%, and 60–80%), whereas uncountoured gray cells had a remaining forest cover of >80%. In the right panel, areas in dark gray show moist forest regions within savanna thresholds for each climate variable. The names of Amazon countries appear abbreviated, and the names of some Brazilian states are also shown.

Discussion

The multiple evidence from our findings indicate that historic deforestation in the Amazon has contributed to a shift in regional climate towards higher temperatures, lower evapotranspiration, lower rainfall in the dry season, and fewer rainy days, compared to climate conditions in highly forested areas. We investigated climate impacts of deforestation by comparing climate averages of deforested cells, grouped by different extents of accumulated deforestation, against their reference neighboring cells (forest cover >80%). Our analysis took into account confounding factors such as spatial variations and internal climate variability, and our findings consistently suggest negative impacts of deforestation on the indicated variables. The observed climate differences between deforested cells and their reference neighbors showed significantly larger magnitudes when compared to reference cells neighboring each other, which we used to indicate the influence of background factors. Overall, climate impacts were more significant for regions that are highly deforested (<60% forest cover), with greater intensity for land surface temperature (LST) and evapotranspiration (ET) as the extent of accumulated deforestation increased.

Our assessment indicates that highly forested regions (>80% forest cover) have distinct climate envelopes from Amazon savannas or transitional regions (in between the moist forest and savanna biome). In contrast, regions that are highly deforested share significant similarities with both highly forested and transitional regions in terms of dry season rainfall and ET, while LST is significantly more similar to savannas or transitional regions. This finding, when linked to our observed impacts of historic deforestation on climate, suggests that deforestation tends to increase the exposure of less tolerant forest species to hotter and drier conditions and might favor the establishment of non-forest vegetation.

It is important to stress, however, that climate shifts alone are not sufficient to explain ecosystem transitions, since this process involves multiple drivers and feedbacks26; for instance, fire activity, soil properties, and ecological networks are also important factors for the establishment of natural savannas40,41,42. More broadly, the deforestation-related climate shifts observed in this study may increase the susceptibility of remaining forests in deforested regions to stressors such as extreme droughts and wildfires, favoring alternative ecosystem trajectories such as degraded forests or open-canopy ecosystems26,32. Moreover, since the climate state in highly deforested regions shows similarities to forest-savanna transitional regions, positive or negative ecological trajectories are possible, depending on human interventions.

The periodic occurrence of extreme droughts in the Amazon36,43 is usually concomitant with heatwaves44. In combination with human-driven wildfires, these events can contribute to reducing the ecological integrity of forests26. This risk becomes especially higher in extensively deforested regions, as deforestation-driven increases in land surface temperature and reductions in rainfall in the dry season, as observed here, can increase vapor pressure deficit and amplify water and heat stress in the remaining forests under extreme drought events45,46. As a result, these forests can face higher drought-induced degradation, leading to increased tree mortality47, and wildfire susceptibility, consequently favoring the dominance of opportunistic native species, alien grasses, or possibly savanna species if the region borders savanna biomes32.

Conversely, large-scale forest restoration can possibly reestablish regional climate resilience by reducing LST48,49 and increasing ET and recycled rainfall50. Despite these potential benefits, secondary forests in the Amazon have their long-term permanence compromised by fire, severe deforestation rates, and the lack of legal protection and law enforcement51,52,53. Properties in the Brazilian Amazon are required by Brazil’s Forest Code (Law No. 12,651/2012) to keep 80% of their area covered by forests. A substantial portion of these properties, however, has vegetation cover debts that amount to about 10 Mha available for forest restoration in the Amazon52. Many of the farmlands with restoration deficits are located in the southern Pará and northern Mato Grosso states54, regions that were identified in our study with climate moving towards savanna-like patterns. We stress the importance of advancing large-scale restoration efforts in these regions to reduce the risk of ecosystem transitions and better safeguard forests more into the interior of the Amazon from facing the same risks.

Recent legislation has been proposed in Brazil (PL No. 3334/2023 at the federal level and PLC No. 18/2024 from Mato Grosso State) with the potential to reduce the 80% forest cover threshold to 50% or even 35% in some regions of the Amazon. We showed that deforestation impacts on climate are already evident in regions with 60–80% of forest cover, especially for LST and ET. Still, these impacts increase in intensity as the remaining forest cover decreases. Thus, legally maintaining the 80% threshold of forest cover is crucial to sustain climate benefits from forests at the regional level. In regions that are highly deforested, climate-based economic activities such as agriculture can face higher climate risks due to the regional reduction of climate regulation services by forests, which can compromise agricultural yield and revenue8,55. By the end of this century, most of the Amazon is expected to be warmer and drier due to global climate change56, which makes the planning for climate-smart landscapes a key strategy for climate change adaptation57. Our results emphasize the importance of maintaining large patches of forests alongside other anthropic land uses for more sustainable climatic conditions in the Amazon.

Previous studies have reported LST and ET differences between deforested and forested areas at fine scales (1 km or greater spatial resolution), indicating local increases in LST during the dry season of 3–4 °C and ET reductions of up to 35–48%7,20,58. Our estimates at 0.5° (~55 km) resolution differ in showing the contribution of deforestation to regional changes in climate, rather than local. We observed that dry season LST is on average 3 °C higher in highly deforested regions, compared with highly forested regions, in line with the local-scale estimates, while dry season ET is 12% lower. At the regional scale, the reduced ET in deforested areas can be compensated by the high ET of remaining forests within the same grid cell, which may partially explain the differences between local and regional estimates.

Our findings indicate clear evidence for deforestation impacts on reduced rainfall during the dry season, while evidence for the annual and wet season periods was not clear. In contrast, findings from other studies at similar scales have indicated deforestation-induced rainfall reductions in the annual and all seasonal periods, or even increases during the wet season10,17. Our average estimate for the deforestation-related reductions in dry season rainfall was -0.37 mm month−1 (95% CI −0.56 to −0.18 mm) per percentage point (pp) reduction in forest cover, while other studies found estimates, at similar scales, of −1.5 mm month−1 and −0.09 mm month−1 10,17. This large variation of magnitude among estimates highlights that, while studies have been agreeing on evidence for deforestation-induced reductions in dry season rainfall, the quantification of these reductions still holds substantial uncertainties. Although our findings also indicate deforestation-related reductions in the number of rainy days, we did not explore the specific periods of the year in which this reduction occurred. Previous studies have linked deforestation to delays in wet season onset and decreases in wet season length9,19,22,23, which may suggest that reductions in rainy days can occur at the dry-to-wet season transition or wet season. Future studies will be important to clarify these knowledge gaps.

Our analyses provided robust assessments of climate shifts in deforested regions by rigorously controlling for confounding factors, but at the expense of reduced sample sizes, mainly for our most deforested cells. Therefore, our estimates for the normalized deforestation impacts on climate should be interpreted with caution due to our small sample size. The wide range of the 95% confidence interval for normalized impacts on ET and rainfall demonstrates the uncertainty of these estimates. The quantification of deforestation impacts on climate with remote sensing observations is still an incipient field, so future studies will be essential to weigh the consistency of observational estimates provided in the scientific literature so far. We also stress that our assessments were based on regions with 0.5° spatial resolution (~55 km), and different patterns or magnitudes for deforestation-climate relationships can emerge at different resolutions, as other studies have been demonstrating8,10,17,19,24.

In the comparison of rainfall between deforested and reference (forest cover >80%) neighboring regions, part of the variation of responses among our samples can come from processes such as landscape configuration and wind direction. For instance, the amount of forested areas surrounding the deforested area and how deforested areas are distributed across the landscape (e.g., large and continuous or small and fragmented patches) are suggested to be important factors for the deforestation-induced changes in mesoscale circulation and rainfall7,12,18,59. Additionally, because rainfall in the deforested area can be influenced by the redistribution or recycling of moisture from the surrounding forested areas18,60, rainfall comparisons between deforested versus reference neighbors can possibly generate different outcomes depending on whether the reference cells are upwind, paralleled, or downwind from deforested cells. Our analysis partially addressed spatial heterogeneity by comparing deforested and reference neighbors across the entire Amazon, and, despite spatial variations, our findings indicate a consistent pattern among our samples for deforestation-induced reductions in dry season rainfall. Future studies are needed to explicitly evaluate how spatial heterogeneity influences assessments of deforestation-induced changes in rainfall by observational approaches.

Amazon forests play an important role in dry season rainfall through evapotranspiration recycling17,61. However, less than 10% of local evapotranspiration is suggested to return as rainfall within a distance of approximately 0.5° from its source62. Because moisture transpired by vegetation in the Amazon can travel, on average, 600 km before precipitating61, rainfall in a given deforested cell can thus also be impacted by deforested regions that are a few hundred kilometers away. Despite not explicitly tracing moisture sources from our deforested cells, we compared deforested and reference forested cells that are immediate neighbors and have a relatively small size, so we assumed these cells share similar external moisture sources and dynamics. Moreover, differences in external moisture sources would appear both in our comparison of deforested versus reference neighbors and reference versus reference neighbors, generating similar biases for these two kinds of comparisons. Because differences in dry season rainfall were more negative (lower rainfall) in deforested versus reference neighbors, compared to reference versus reference neighbors, it is very likely that different external moisture sources are not the main factor contributing to the lower rainfall in deforested cells.

Alternatively, it is also plausible that deforested cells may be experiencing greater rainfall inhibition mechanisms than surrounding forested cells. For instance, a warmer and drier lower troposphere during the dry season was found in deforested regions at the 0.5° resolution, which can enhance hot-dry updrafts and reduce the inflow of external moisture sources that contribute to rainfall in that region63. Considering the scientific understanding of mechanisms behind deforestation-induced rainfall reductions is still limited, further studies linking changes in atmospheric moisture flow and rainfall will be important to help elucidate some of the current uncertainties.

Methods

Study region

Our study region consists of the Amazonia sensu lato, which covers the entire biogeographical limits of the Amazon lowland rainforest biome64. These limits span across eight countries (Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Suriname, Guyana) and one overseas department (French Guiana), including some regions of other biomes such as savannas and grasslands.

We divided this region into grid cells to use them as samples in our comparisons of climate variables according to different extents of remaining forest cover and biome types. We worked with grid cells of 0.5° (~55 km) spatial resolution, a size that allows for a good number of samples considering the several criteria we applied to select grid cells and control the role of deforestation from other drivers. Part of our analysis consists of comparing deforested cells against their highly forested neighboring grid cells, assuming they share a similar climatic background by being geographically close. In this sense, neighboring grid cells are more likely to share similar climatic backgrounds in a smaller grid size, such as 0.5°, compared to 1° or 2°. Moreover, according to Cohn et al.65, non-local forest loss can influence temperature in areas within 50 km of distance, most likely through heat advection. By using the 0.5° resolution, we therefore minimize the influence of deforestation from a given grid cell on land surface temperature in another neighboring grid cell. In addition, previous studies have found diverging impacts of deforestation on rainfall at the 0.5° resolution8,10,17,21,63, which reinforces the importance of additional studies for land-atmosphere interactions for grid sizes within this range.

Climate variables

We analyzed the following climate variables: land surface temperature, evapotranspiration, rainfall, maximum dry spell duration, and number of rainy days.

For land surface temperature (LST), we used daily daytime data from the MYD11A1 v061 product, based on the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensor on board the Aqua satellite. Aqua crosses the equator around 1:30 pm in its daytime passage, so MYD11A1 estimates are close to the maximum temperature of the day. LST from MYD11A1 has a 1 km spatial resolution and is based on emissivity from thermal infrared bands according to MODIS land cover data for pixels under clear-sky conditions. We only selected pixels with the highest accuracy according to the product quality control, which are those with LST error ≤1 K and emissivity error ≤0.01.

For evapotranspiration (ET), we used the recently developed geeSEBAL-MODIS data66. This product provides daily average estimates of ET for every 8 days with a 500 m spatial resolution. The computation is based on the residual of the energy balance equation and uses LST and vegetation indices from MODIS Aqua as inputs, in addition to land cover from MODIS MCD12Q1. According to an assessment of ET products against flux tower data and water balance of river basins in the Amazon66, geeSEBAL-MODIS yielded the highest accuracies, outperforming commonly used ET products such as MOD16 and ERA5.

To derive all rainfall-related variables, we used daily rainfall estimates from the Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station (CHIRPS) v2 product. CHIRPS blends rainfall estimates from thermal infrared observations of cold cloud duration and rain gauge to provide data with 0.05° of spatial resolution67. CHIRPS has been shown to have a higher performance in the Amazon when compared to several other satellite-based rainfall datasets68,69. To derive the variable number of rainy days, we considered the total number of days with rainfall ≥1 mm on a yearly basis. In contrast, the maximum dry spell duration variable was derived by the maximum number of consecutive days with rainfall <1 mm.

Forest cover data

We used yearly maps of forest classification from 2013 to 2021 from MapBiomas Amazonia Collection 4 to derive the forested area in 0.5° grid cells by summing the area of all forest pixels inside each grid cell. MapBiomas uses a supervised random forest classification with spectral metrics of the Landsat program as inputs. The mapping process also uses post-classification spatial and temporal filters to reduce misclassifications and inconsistent land cover/land-use transitions. We computed the annual percentage of forest cover in each grid cell by dividing the total forest area by the cell’s area. For the grid cells on the borders, whose area is not entirely within the Amazon boundaries, the percentage of forest cover was relative only to the cell’s area inside the Amazon. We computed the corresponding forest loss from 2013 to 2021 in 0.5° grid cells by the difference between the percentage forest cover in 2013 and 2021.

Time series and grid cell aggregation

We computed climate data for each year from 2013 to 2021. The analysis covered three different periods: annual (total 12 months of the calendar year), wet season (three consecutive months with the largest rainfall), and dry season (three consecutive months with the lowest rainfall). Wet and dry seasons were computed according to the corresponding rainfall climatology from 1990 to 2020, derived from CHIRPS for each 0.5° grid cell. We first computed the monthly mean rainfall over 1990-2020 in each grid cell and then identified their three consecutive wettest and driest months. Supplementary Fig. 3 shows the spatial variation in wet and dry seasons across the Amazon. Although the actual three consecutive driest and wettest months can vary year to year, our definition based on fixed wettest and driest periods according to rainfall climatology shows a good correspondence with year-to-year variations during 2013–2021 for the majority of grid cells (Supplementary Fig. 4), providing a good representation of wettest and driest periods in general.

We computed on a pixel basis the monthly averages of land surface temperature (LST) and monthly sums of evapotranspiration (ET) and rainfall, in addition to yearly values of maximum dry spell duration and the annual number of rainy days. Subsequently, we summarized the values per 0.5° grid cell by taking the mean of all pixels within each grid cell. For each year from 2013 to 2021, we aggregated the monthly values of LST, rainfall, and ET to the annual, wet and dry seasons by taking the average in each period for LST and the total sum for ET and rainfall.

Climate differences between deforested and reference regions

To assess how climate differences vary according to the extent of accumulated deforestation, we grouped our 0.5° grid cells into the following ranges of remaining forest cover in 2021: ≤40%, 40–60%, 60–80%, >80%. According to MapBiomas statistics for land cover/land-use decadal transitions (1990–2000, 2000–2010, 2010–2020) in the Amazon70, more than 85% of the lost forest area transitioned into anthropogenic land uses, of which more than 97% were to pasture and croplands. Therefore, the extent of remaining forest cover in 2021 is inversely related to the accumulated deforested area used mainly for agriculture. To ensure this rationale is valid, we only selected grid cells entirely within the moist forest biome71, which indicates that these regions were not originally covered by non-forest vegetation. We also removed by visual inspection some grid cells whose area was substantially covered by extensive water surfaces, which occurred in the northern Brazilian Amazon along major rivers.

Our analysis was restricted to grid cells with negligible forest loss (≤1 percentage point difference between forest cover in 2013 and 2021) to guarantee that comparisons of climate averages among grid cells would be linked to the accumulated deforestation up to the beginning of our time series (historic deforestation), rather than influenced by land-use change during 2013–2021. We used cells with forest cover >80% as our reference for climate conditions of highly forested and conserved regions under minimal influence of historic deforestation. The remaining three groups (≤40%, 40–60%, 60–80%) were treated as our deforested cells from which their climate averages were compared against reference cells. To ensure deforested and reference cells shared similar geographic and climatic backgrounds, we selected for the main analyses only deforested regions that were neighboring reference regions within a 3 × 3 window and vice versa. This selection retrieved the following number of grid cells for each forest cover group: 12 for ≤40%, 15 for 40–60%, 45 for 60–80%, and 132 for the reference (as shown in Fig. 1).

We calculated pairwise differences between the 2013–2021 climate averages in deforested cells against their reference neighbors (as illustrated in Fig. 1). Likewise, we computed pairwise differences between reference cells that were neighboring each other. In deforested versus reference comparisons, forest cover in deforested cells was necessarily smaller than in reference cells (i.e., a negative difference in forest cover). On the other hand, a given reference cell can have a smaller, equal, or larger forest cover than its other reference neighbor. Thus, we only selected pairs of reference versus reference neighbors in which the forest cover difference was negative or equal to zero to ensure a similar principle of comparison with deforested versus reference neighbors. To further control similarities in the climate background of deforested versus reference or reference versus reference neighbors, we only selected pairs of differences for neighboring grid cells in the same Köppen climate zone, based on gridded climate classifications at 0.5° resolution for the 1976–2000 period72. Our final selection resulted in the following number of pairwise differences according to the forest cover group: 17 for ≤40% versus reference, 30 for 40–60% versus reference, 163 for 60–80% versus reference, and 148 for reference versus reference. We used the Two-Sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (two-tailed at the 0.05 level) to assess the significance of differences between the deforested versus reference and reference versus reference distributions, in addition to using Welch’s t-test (two-tailed at the 0.05 level) to assess differences in the mean.

To reinforce that climate differences related to deforestation are larger than those found by other climate drivers and spatial variability, we also reapplied our statistical tests by comparing the original deforested versus reference samples against random subsamples of reference versus reference neighbors across our entire study region. We randomly selected one thousand subsamples of 150 pairwise differences between reference neighbors pooled from a total of 4352 pairwise differences between 1156 reference cells (grid cells in dark and faded green in Fig. 1). We also considered only pairwise differences for reference cells sharing the same Köppen climate zone and whose forest cover difference was negative or equal to zero. The deforested (≤40%, 40–60%, and 60–80% forest cover) versus reference distributions of climate differences were tested against each of the one thousand distributions of reference versus reference subsamples. We then computed the 95% confidence interval of p-values from these tests (Supplementary Table 1).

We also tested if the average climate differences between deforested versus reference neighbors significantly vary in magnitude among our three groups of deforested cells (≤40%, 40–60%, and 60–80% forest cover), based on the two-tailed Welch’s t-test at the 0.05 level. This test was performed considering the absolute magnitude of climate differences, such as in the previous analyses, but also the relative climate differences, which indicate the percentage difference in climate averages between deforested and reference cells, as follows:

where the relative climate difference for a given climate variable i and pair j of deforested (DEF) versus reference (REF) neighboring cells is given by the difference in the average of climate variable i during 2013–2021 (X̄) between these two cells divided by the average in the reference cell.

Estimating the mean impact of deforestation on climate variables

Climate differences between the selected deforested versus reference neighboring cells vary in magnitude, considering the differences in forest cover between these cells and the different set of background factors for each pair of deforested versus reference neighbors, such as topography and wind direction. This analysis aimed to provide estimates of climate impacts more likely associated with deforestation by integrating and taking into account the variation of climate differences among our deforested versus reference comparisons.

From the original set of deforested cells used in the previous analyses, we selected only the ones with two or more reference neighbors (52 deforested cells). We then normalized absolute and relative climate differences between a given pair of deforested cell and reference neighboring cell by the corresponding difference in forest cover between these cells. For instance, the normalization of absolute climate differences was calculated as follows:

where the difference in the 2013–2021 average (X̄) of a given climate variable i between a pair j of deforested (DEF) and reference (REF) neighboring cells is divided by the absolute value of the difference in forest cover (FC) between these cells. Forest cover was calculated as the percentage of forest area relative to the cell’s area.

For each deforested cell, we then computed the mean normalized climate difference between that cell and all its reference neighbors, so each deforested cell has a single climate difference. Subsequently, for each climate variable, we removed the normalized climate differences considered as outliers by only keeping values above the 5th percentile and below the 95th percentile of the distribution among our samples. The mean deforestation impact on climate, and its 95% confidence interval, was then computed as the mean normalized climate difference among our samples. With this approach, we assume our final estimate, which is derived from the central value of the distribution, has a reduced influence of factors other than deforestation, since the contribution of these background factors would be larger in values dispersed from the mean and the most extreme values. We acknowledge that such approach, however, does not fully disentangle the contribution of deforestation from other factors. The total number of pairwise climate differences considered to compute these final estimates was 46, 4 from the deforestation group with forest cover ≤40%, 8 from the group with 40–60%, and 34 from the group with 60–80%. Absolute estimates of deforestation impacts on ET and rainfall during the wet and dry seasons were divided by 3 to indicate the mean impacts per month, since these variables were originally summed over the three consecutive wettest and driest months for the wet and dry seasons, respectively.

Climate characteristics of biomes

This analysis aimed to evaluate whether the climate envelope of highly deforested regions has shifted away from reference conditions in highly forested regions to become more similar to the climate envelope of other biomes. We used data for biome distribution in the Amazon provided by Dinerstein et al.71, based on the work of Olson et al.73, which provided a consistent evaluation and delimitation of biome boundaries. From this data, given the very small area of Mangroves and Flooded Grasslands biomes in the Amazon, we aggregated them respectively to the Tropical and Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forests and Tropical and Subtropical Savannas and Grasslands biomes, renaming these classes to Moist forests and to Savannas, respectively. We also created an additional class named Forest-savanna transitional regions to contemplate grid cells containing both tropical moist forests and savanna biomes. We assigned grid cells to this transitional class if more than 10% of their Amazon area was in one biome (Moist forests or Savannas) and less than 90% in the other. We also kept for the analysis only grid cells of the Savannas class with forest cover ≤40% in 2021, as they would provide a more loyal representation of this biome.

The Moist Forest biome class in this analysis was represented by the categories Highly deforested regions and Highly forested regions. Deforested cells with forest cover ≤40% and 40–60%, selected from the original sample used in previous analyses, were used here as our highly deforested regions, whereas their reference neighbors (forest cover>80%) within a 3 × 3 window from the same Köppen climate zone were used as our highly forested regions. The final number of grid cell samples used in the biome comparisons was as follows: 27 for highly deforested regions, 38 for highly forested regions, 126 for transitional (savannas & moist forests), and 41 for savannas. We compared the distribution of climate averages during 2013–2021 among our biome categories with the two-tailed Welch’s t-test and Two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test at the 0.05 level of significance. Additionally, we computed the 5th percentile, mean, and 95th percentile of climate averages in each biome category to represent their corresponding climate envelope in the Amazon.

From the total number of cells in highly deforested and forested regions, we compared the percentage of cells whose climate average conforms with the climate envelope of savannas. We considered that land surface temperature (LST) averages were in the envelope of savannas if they were greater than or equal to the 5th percentile of the LST distribution in our savanna samples. Likewise, evapotranspiration (ET) and rainfall values were in the envelope of savannas if they were less than or equal to the 95th percentile of the distribution in our savanna samples. We did not consider the variables wet season ET and maximum dry spell duration in this analysis, since no significant distinction in the distribution of these variables was found between highly forested regions and savannas. We also visually assessed the spatial distribution of moist forest cells in the savanna envelope according to the deforestation extent of these areas. This analysis was applied to all moist forest cells across the Amazon, not just the selected highly forested and deforested samples. The analysis contemplated four variables that showed a good distinction between highly deforested and forest cells: annual ET, annual LST, wet season rainfall, and dry season rainfall. The more variables a given area in the Amazon has in the savanna envelope, the more similar the climate in that area is to the climate envelope of savannas.

Data availability

Data generated by this study for the main analyses and figures is archived in the following Zenodo repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17253537. MapBiomas forest cover data, geeSEBAL-MODIS ET, MODIS LST, and CHIRPS rainfall were collected through Google Earth Engine. Alternatively, MapBiomas Amazonia forest cover data is available on: https://amazonia.mapbiomas.org/en/, geeSEBAL-MODIS ET is available on: https://gee-community-catalog.org/projects/gee_sebal/ (see also Comini de Andrade et al.66), MODIS LST is available on: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-myd11a1-061, and CHIRPS rainfall is available on: https://www.chc.ucsb.edu/data/chirps. Data about Köppen-Geiger climate zones is available on: https://koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at/shifts.htm. Data about biome distributions is available on: https://ecoregions.appspot.com/ (see also Dinerstein et al.71).

Code availability

R codes to generate the main analyses and figures of this study are available in the following Zenodo repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17253537.

References

Calvin, K. et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Core Writing Team, Lee, H. & Romero, J.) (IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2023).

Bonan, G. B. Forests and climate change: forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 320, 1444–1449 (2008).

Artaxo, P. et al. Tropical and boreal forest – atmosphere interactions: a review. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 74, 24 (2022).

European Commission. Joint Research Centre. Deforestation and Forest Degradation in the Amazon: Update for Year 2023 and Assessment of Humid Forest Regrowth (Publications Office, LU, 2025).

Spracklen, D. V., Baker, J. C. A., Garcia-Carreras, L. & Marsham, J. H. The effects of tropical vegetation on rainfall. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 43, 193–218 (2018).

Baker, J. C. A. & Spracklen, D. V. Climate benefits of intact Amazon Forests and the biophysical consequences of disturbance. Front. Glob. Chang. 2, 47 (2019).

Maeda, E. E. et al. Large-scale commodity agriculture exacerbates the climatic impacts of Amazonian deforestation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2023787118 (2021).

Leite-Filho, A. T., Soares-Filho, B. S., Davis, J. L., Abrahão, G. M. & Börner, J. Deforestation reduces rainfall and agricultural revenues in the Brazilian Amazon. Nat. Commun. 12, 2591 (2021).

Leite-Filho, A. T., Costa, M. H. & Fu, R. The southern Amazon rainy season: the role of deforestation and its interactions with large-scale mechanisms. Int. J. Climatol. 40, 2328–2341 (2020).

Smith, C., Baker, J. C. A. & Spracklen, D. V. Tropical deforestation causes large reductions in observed precipitation. Nature 615, 270–275 (2023).

Franco, M. A. et al. How climate change and deforestation interact in the transformation of the Amazon rainforest. Nat. Commun. 16, 7944 (2025).

Roy, S. B. Mesoscale vegetation-atmosphere feedbacks in Amazonia. J. Geophys. Res. 114, 2009JD012001 (2009).

Khanna, J., Medvigy, D., Fueglistaler, S. & Walko, R. Regional dry-season climate changes due to three decades of Amazonian deforestation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 200–204 (2017).

Saad, S. I., Da Rocha, H. R., Silva Dias, M. A. F. & Rosolem, R. Can the deforestation breeze change the rainfall in Amazonia? A case study for the BR-163 highway region. Earth Interact. 14, 1–25 (2010).

Khanna, J., Medvigy, D., Fisch, G. & De Araújo Tiburtino Neves, T. T. Regional hydroclimatic variability due to contemporary deforestation in Southern Amazonia and associated boundary layer characteristics. JGR Atmos. 123, 3993–4014 (2018).

Negri, A. J., Adler, R. F., Xu, L. & Surratt, J. The impact of Amazonian deforestation on dry season rainfall. J. Clim. 17, 1306–1319 (2004).

Qin, Y., Wang, D., Ziegler, A. D., Fu, B. & Zeng, Z. Impact of Amazonian deforestation on precipitation reverses between seasons. Nature 639, 102–108 (2025).

Knox, R., Bisht, G., Wang, J. & Bras, R. Precipitation variability over the forest-to-nonforest transition in Southwestern Amazonia. J. Clim. 24, 2368–2377 (2011).

Leite-Filho, A. T., Soares-Filho, B. S. & De Oliveira, U. Climate risks to soy-maize double-cropping due to Amazon deforestation. Int. J. Climatol. 44, 1245–1261 (2024).

Reygadas, Y., Spera, S. A. & Salisbury, D. S. Effects of deforestation and forest degradation on ecosystem service indicators across the Southwestern Amazon. Ecol. Indic. 147, 109996 (2023).

Debortoli, N. S. et al. Detecting deforestation impacts in Southern Amazonia rainfall using rain gauges. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 2889–2900 (2017).

Leite-Filho, A. T., De Sousa Pontes, V. Y. & Costa, M. H. Effects of deforestation on the onset of the rainy season and the duration of dry spells in Southern Amazonia. JGR Atmos. 124, 5268–5281 (2019).

Wright, J. S. et al. Rainforest-initiated wet season onset over the southern Amazon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 8481–8486 (2017).

D’Almeida, C. et al. The effects of deforestation on the hydrological cycle in Amazonia: a review on scale and resolution. Int. J. Climatol. 27, 633–647 (2007).

Spracklen, D. V. & Garcia-Carreras, L. The impact of Amazonian deforestation on Amazon basin rainfall. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 9546–9552 (2015).

Brando, P. M. et al. Tipping points of Amazonian Forests: beyond myths and toward solutions. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 50 (2025).

Nobre, C. A., Sellers, P. J. & Shukla, J. Amazonian deforestation and regional climate change. J. Clim. 4, 957–988 (1991).

Lapola, D. M., Oyama, M. D. & Nobre, C. A. Exploring the range of climate biome projections for tropical South America: the role of CO2 fertilization and seasonality. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 23, 2008GB003357 (2009).

Nobre, C. A. & Borma, L. D. S. ‘Tipping points’ for the Amazon forest. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 1, 28–36 (2009).

Lyra, A. D. A., Chou, S. C. & Sampaio, G. D. O. Sensitivity of the Amazon biome to high resolution climate change projections. Acta Amazonica 46, 175–188 (2016).

Malhi, Y. et al. Exploring the likelihood and mechanism of a climate-change-induced dieback of the Amazon rainforest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 20610–20615 (2009).

Flores, B. M. et al. Critical transitions in the Amazon forest system. Nature 626, 555–564 (2024).

Staver, A. C., Archibald, S. & Levin, S. A. The global extent and determinants of savanna and forest as alternative biome states. Science 334, 230–232 (2011).

Hirota, M., Holmgren, M., Van Nes, E. H. & Scheffer, M. Global resilience of tropical forest and savanna to critical transitions. Science 334, 232–235 (2011).

Aragão, L. E. O. C. et al. 21st Century drought-related fires counteract the decline of Amazon deforestation carbon emissions. Nat. Commun. 9, 536 (2018).

Silveira, M. V. F., Silva-Junior, C. H. L., Anderson, L. O. & Aragão, L. E. O. C. Amazon fires in the 21st century: the year of 2020 in evidence. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 31, 2026–2040 (2022).

Tian, K. et al. Drought events over the Amazon River Basin (1993–2019) as detected by the climate-driven total water storage change. Remote Sens. 13, 1124 (2021).

Adeney, J. M., Christensen, N. L., Vicentini, A. & Cohn-Haft, M. White-sand ecosystems in Amazonia. Biotropica 48, 7–23 (2016).

Messias, C. G. et al. Unaccounted for nonforest vegetation loss in the Brazilian Amazon. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 451 (2024).

Holmgren, M., Alba-Costas, P., Flores, B. M. & Van Der Sleen, P. Forest-savanna transitions self-reinforced by altered tree dispersal networks in burnt Amazonian floodplain forests. Environ. Res. Lett. 20, 031004 (2025).

Flores, B. M. & Holmgren, M. White-sand savannas expand at the core of the Amazon after forest wildfires. Ecosystems 24, 1624–1637 (2021).

Veldman, J. W. & Putz, F. E. Grass-dominated vegetation, not species-diverse natural savanna, replaces degraded tropical forests on the southern edge of the Amazon Basin. Biol. Conserv. 144, 1419–1429 (2011).

Espinoza, J.-C. et al. The new record of drought and warmth in the Amazon in 2023 related to regional and global climatic features. Sci. Rep. 14, 8107 (2024).

Libonati, R. et al. Drought–heatwave nexus in Brazil and related impacts on health and fires: a comprehensive review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1517, 44–62 (2022).

Mu, Y. et al. Increasing dry-season vapor pressure deficit in the Amazon Basin: historical trends, future projections, and links to deforestation. Environ. Res. Commun. 7 (2025).

Novick, K. A. et al. The impacts of rising vapour pressure deficit in natural and managed ecosystems. Plant Cell Environ. 47, 3561–3589 (2024).

Berenguer, E. et al. Tracking the impacts of El Niño drought and fire in human-modified Amazonian forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2019377118 (2021).

Prevedello, J. A., Winck, G. R., Weber, M. M., Nichols, E. & Sinervo, B. Impacts of forestation and deforestation on local temperature across the globe. PLoS ONE 14, e0213368 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Asymmetric impacts of forest gain and loss on tropical land surface temperature. Nat. Geosci. 17, 426–432 (2024).

Tuinenburg, O. A., Bosmans, J. H. C. & Staal, A. The global potential of forest restoration for drought mitigation. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 034045 (2022).

Baker, J. C. A. et al. Climate benefits of Amazon secondary forests—recent advances and research needs. Environ. Res. Lett. 20, 043001 (2025).

Dutra, D. J. et al. Challenges for reducing carbon emissions from land-use and land cover change in Brazil. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 22, 213–218 (2024).

Heinrich, V. H. A. et al. Large carbon sink potential of secondary forests in the Brazilian Amazon to mitigate climate change. Nat. Commun. 12, 1785 (2021).

Centre for Remote Sensing of UFMG. X-ray of the CAR (Brazil’s Environmental Registry). X-Ray of the CAR https://csr.ufmg.br/radiografia_do_car/ (n.d).

Flach, R. et al. Conserving the Cerrado and Amazon biomes of Brazil protects the soy economy from damaging warming. World Dev. 146, 105582 (2021).

Carvalho, S. et al. A changing Amazon rainforest: historical trends and future projections under post-Paris climate scenarios. Glob. Planet. Chang. 195, 103328 (2020).

Harvey, C. A. et al. Climate-smart landscapes: opportunities and challenges for integrating adaptation and mitigation in tropical agriculture. Conserv. Lett. 7, 77–90 (2014).

Oliveira, G. et al. Effects of land-cover changes on the partitioning of surface energy and water fluxes in Amazonia using high-resolution satellite imagery. Ecohydrology 12, e2126 (2019).

Lawrence, D. & Vandecar, K. Effects of tropical deforestation on climate and agriculture. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 27–36 (2015).

Spracklen, D. V., Arnold, S. R. & Taylor, C. M. Observations of increased tropical rainfall preceded by air passage over forests. Nature 489, 282–285 (2012).

Staal, A. et al. Forest-rainfall cascades buffer against drought across the Amazon. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 539–543 (2018).

Theeuwen, J. J. E., Staal, A., Tuinenburg, O. A., Hamelers, B. V. M. & Dekker, S. C. Local moisture recycling across the globe. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 27, 1457–1476 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. Deforestation triggering irreversible transition in Amazon hydrological cycle. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 034037 (2022).

Eva, H. & Huber, O. A proposal for defining the geographical boundaries of Amazonia. EUR 21808 EN. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC68635 (2005).

Cohn, A. S. et al. Forest loss in Brazil increases maximum temperatures within 50 km. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 084047 (2019).

Comini De Andrade, B. et al. geeSEBAL-MODIS: continental-scale evapotranspiration based on the surface energy balance for South America. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 207, 141–163 (2024).

Funk, C. et al. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations—a new environmental record for monitoring extremes. Sci. Data 2, 150066 (2015).

De Moraes Cordeiro, A. L. & Blanco, C. J. C. Assessment of satellite products for filling rainfall data gaps in the Amazon region. Nat. Resour. Model. 34, e12298 (2021).

Sapucci, C. R., Mayta, V. C. & Da Silva Dias, P. L. Evaluation of diverse-based precipitation data over the Amazon Region. Theor. Appl Climatol. 149, 1167–1193 (2022).

MapBiomas Amazonia. Land Cover and Transitions by Biome (Collection 6) https://amazonia.mapbiomas.org/en/statistics/ (2025).

Dinerstein, E. et al. An Ecoregion-based Approach To Protecting Half The Terrestrial Realm. BioScience 67, 534–545 (2017).

Rubel, F. & Kottek, M. Observed and projected climate shifts 1901-2100 depicted by world maps of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. metz 19, 135–141 (2010).

Olson, D. M. et al. Terrestrial Ecoregions of the world: a new map of Life on Earth. BioScience 51, 933 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This study was financed, in part, by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), Brazil (grant numbers 2022/11698−8, 2020/15230-5, and 2023/05733-8), and by the Brazilian Space Agency (AEB). The authors also thank the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) through the grant number 310652/2025-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.V.F.S. and L.E.O.C.A conceived and designed this study. M.V.F.S. collected and processed the data for formal analyses. A.R. provided the geeSEBAL-MODIS data. M.V.F.S. performed the formal analysis and data visualization. M.V.F.S. wrote the manuscript while L.E.O.C.A., P.W.K., P.A., M.H.C., L.O.A., M.A., A.R., and C.V.R. reviewed the manuscript and contributed with recommendations, edits, or suggestions to the final text. L.E.O.C.A. and P.W.K. supervised this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Alvaro Salazar and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Rodolfo Nóbrega and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Silveira, M.V.F., Keys, P.W., Ruhoff, A. et al. Observed shifts in regional climate linked to Amazon deforestation. Commun Earth Environ 6, 948 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02900-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02900-2