Abstract

While dam-based regulation modifies the natural transport rhythm of riverine materials, the effects of artificial flooding on river mouth dissolved organic matter (DOM) dynamics remain poorly constrained. The Water-Sediment Regulation Scheme in the Yellow River provides a unique snapshot. Distinct organic matter signatures were observed between the water release and sediment flushing phases using optical and molecular techniques. Here we show that during water release phase, rapid discharge of upper-layer water from Xiaolangdi Reservoir increased the proportion of bio-labile DOM in the Yellow River mouth. Conversely, during sediment flushing phase, resuspension and then release of bottom sediments from the reservoir enhanced aromatic DOM components. Although the relative abundance and composition of particulate organic matter remained unchanged during water release phase, it increased during sediment flushing phase. These findings demonstrate that reservoir operations reconfigure river-ocean carbon flows, emphasizing the need to integrate dam management strategies into global carbon cycling models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Riverine dissolved organic matter (DOM) serves as a critical nexus in the global carbon cycle, transporting ~250–260 Tg C annually from terrestrial ecosystems to coastal oceans1. In recent years, with intensifying human activities, 63% of the world’s rivers have been fragmented by dams, significantly altering their natural material transport rhythms2,3. While reservoirs exhibit stratification patterns similar to natural lakes, their ecological environments differ markedly due to artificial discharge regulation4,5,6. Reservoirs exhibit stronger terrestrial signatures in DOM compared to non-reservoir water bodies7. These enhanced terrestrial DOM signatures, characterized by higher aromaticity and refractivity, promote organic carbon burial efficiency in reservoirs8,9. During the impoundment period, the properties and composition of reservoir DOM exhibit distinct vertical stratification due to the intrusion of mainstream water10. Surface layers are dominated by photodegradation and autochthonous production, yielding labile, low-molecular-weight compounds; intermediate depths show terrestrial DOM enrichment with high aromaticity; while benthic zones accumulate microbially transformed refractory DOM. The vertical stratification in reservoirs combined with dam interception effects has modified riverine material transport and transformation processes in downstream areas8,11,12. However, the specific impacts of reservoir discharges on organic matter dynamics at the river mouth remain poorly understood.

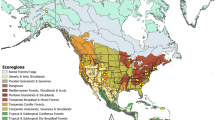

The Yellow River, recognized as the world’s most sediment-laden river, delivers ~1.6 Gt of sediment annually to the Bohai Sea13. Its lower reaches form a characteristic elevated channel with minimal tributary input, providing an ideal setting to directly observe the impacts of reservoir discharges on the composition and properties of DOM in downstream (Fig. 1). Since 2002, the Yellow River Conservancy Committee has implemented the Water-Sediment Regulation Scheme (WSRS), an artificial flood event jointly operated by the Xiaolangdi, Sanmenxia, and Wanjiazhai reservoirs to mitigate sedimentation and flooding risks by releasing reservoir clear water and flushing deposited sediments13. During WSRS, the river’s discharge surges from ~500 to 3000 m³ s–1, while suspended sediment concentration (SSC) increases by 60-fold (from 0.5 to 30 kg m–³), drastically reshaping hydrodynamic conditions14. Consequently, the particulate organic carbon (POC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) fluxes during WSRS were 50–80% and ~30% of the annual flux, respectively15,16. After that, because of the release of sediment deposited in the Xiaolangdi Reservoir (XR), the content of black carbon and ancient organic carbon components significantly increased compared to non-WSRS periods17. Previous investigations have documented WSRS-induced changes in sediment morphology, nutrient fluxes, and pollutant transport18,19,20, yet the concurrent impacts on DOM chemistry, particularly its molecular composition and reactivity, remain poorly understood. This knowledge gap limits our ability to predict how anthropogenic hydrological interventions may perturb the river-ocean carbon continuum21, especially in the context of increasing dam construction globally22.

a Locations of Yellow River Basin in China and the sampling site (★) in YRM. The basin relief dataset is provided by National Cryosphere Desert Data Center, available at http://www.ncdc.ac.cn. b Daily water flow (WF) and suspended sediment concentration (SSC) at Xiaolangdi and Lijin station, separately. Real-time data is available at http://www.yrcc.gov.cn/zxfw/sqsz/.

To bridge this gap, we employed a multi-technique framework integrating optical spectroscopy, stable carbon isotopes (δ¹³C), and ultrahigh-resolution Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR MS). While excitation-emission matrix fluorescence spectroscopy with parallel factor analysis (EEM-PARAFAC) provides rapid insights into DOM sources (e.g., humic-like vs. protein-like components)23, FT-ICR MS resolves thousands of molecular formulae, enabling unprecedented characterization of polyaromatic hydrocarbons and other key groups that govern DOM reactivity24. This multi-proxy approach offers unprecedented resolution to decode how artificial flood events reshape DOM chemistry in turbid river systems.

This study aims to address how the WSRS regulates the composition and properties of DOM at the Yellow River mouth. By coupling reservoir management strategies with estuarine carbon dynamics, our findings not only advance mechanistic insights into DOM transformations in reservoir-dominated systems, but also provide insights for explore the linkage between reservoir-induced DOM dynamics and carbon sequestration.

Results

Variations of POC and DOC concentrations during WSRS

During WSRS, distinct temporal patterns were observed in POC and DOC dynamics. POC exhibited a moderate increase during water release phase (WRP), followed by a sharp rise in sediment flushing phase (SFP), whereas DOC concentrations showed irregular fluctuations without discernible trends (Fig. 2b). Pre-WSRS baseline measurements show average values of 363 m³ s–1 for water flow (WF), 0.69 kg m–³ for SSC (Fig. 2a), 4.18 mg L–1 for POC, and 20.33 mg L–1 for DOC (Fig. 2b). On June 23rd, at the initiation of WSRS, WF surges from 340 to 1310 m³ s–1, culminating in the peak discharge of 3970 m³ s–1 by July 02nd. Concurrently, SSC and POC displayed slight increases (4.49 ± 1.03 kg m–³ and 14.96 ± 3.79 mg L–1, respectively) during WRP (June 23rd–July 09th). On July 10th, a marked hydrological shift occurred, characterized by a rapid WF decline from 3935 to 2500 m³ s–1 and a dramatic SSC escalation from 4.69 to 31 kg m–³ at Lijin station, demarcating the onset of sediment transport from XR. This transition coincided with a substantial POC amplification, reaching a maximum concentration of 146.21 mg L–1. Strong positive correlations were identified between SSC and POC throughout the observation period (p < 0.001), whereas DOC exhibited no statistically significant relationships with either SSC or POC (p > 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Further, the lack of correlation between temporal changes in DOC concentration and chromophoric DOM (CDOM) and fluorescent DOM (FDOM) abundance (Supplementary Fig. S2), optical indices, and FT-ICR-MS parameters suggests that fluctuations in DOC concentration reflect contributions from fractions of dam-regulated DOM that are non-chromophoric, non-fluorescent, or undetectable by FT-ICR-MS. This further highlights the critical importance of research into the composition and characteristics of DOM.

0623 is the first day of water release phase (WRP) and 0710 is the first day of sediment flushing phase (SFP) at Lijin station during observation. The blue line in (e), (f), (g), and (h) represents WF at Lijin station, and the gray line indicates SSC in the water body. The different colors in (e), (f), and (h) represent pre-WSRS (June 21st and June 22nd), the first half of the water diversion stage (June 23rd–July 1st), the second half of the water diversion stage (July 2nd–July 9th) and the sediment regulation stage (July 10th–July 12th) respectively. a The data of water flow (WF) and suspended sediment concentration (SSC) from Lijin station; b particulate organic carbon (POC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations during WSRS; c the a350 value of POM, a350-P; d the fluorescence intensity of POM, F-POM; e the a350 value of DOM, a350-D f the spectral slope of DOM, SR-D; g the fluorescence intensity of DOM, FDOM; h the humification index of DOM, HIX-D.

DOM content and composition during WSRS

Contrasting dynamics of organic matter fractions were observed between WRP and SFP. Specifically, the molecular composition and optical properties of DOM underwent significant transformations (Figs. 2 and 3). EEMs-PARAFAC identified three fluorescent components in DOM: two humic-like substances (C1 and C2) and a protein-like component (C3) (Supplementary Fig. S2; Table S2), all showing temporal trends consistent with total FDOM intensity (Fig. 2g). C1 dominated the DOM pool (52.9 ± 1.6%), followed by C2 (29.6 ± 2.2%) and C3 (17.5 ± 3.0%). Notably, the relative abundances of CDOM and FDOM were significantly elevated in SFP compared to WRP (p < 0.05, Fig. 2e–g).

The blue line represents water flow (WF) at Lijin station, and the gray line indicates suspended sediment concentration (SSC) in the water body. a formulae; b m/z; c H/C; d O/C; e Aromaticity index, AI; f Double bound equivalent, DBE; g CHO%; h CHOS%; i (Saturated compounds + unsaturated aliphatic compounds) %, (SAT+UAC) %; j Highly unsaturated compounds%, HUC%; k (Polyphenols+polycyclic aromatics)%, (Poly+PCAs) %; l Carboxylic-rich alicyclic molecules%, CRAM%.

FT-ICR MS resolved an average of 7722, 7442, and 8394 molecular formulae in DOM during pre-WSRS, WRP, and SFP, respectively, with molecular complexity peaking on July 10th (8418 formulae) during maximal SSC (Fig. 3a). CHO compounds constituted the dominant molecular class (61.48 ± 5.76%, 2395 ± 110 formulae), followed by CHOS (21.58 ± 5.94%, 1,653 ± 256 formulae), a proportion markedly exceeding global riverine averages (~10%)25 and regional counterparts like the Pearl River (8.9%)26 and Yangtze River (5–15%)27. This high CHOS abundance strongly implicates anthropogenic influences, likely linked to industrial or agricultural sulfur inputs24. Conversely, nitrogen-containing compounds (CHON) accounted for only 13.29 ± 1.61% (2703 ± 142 formulae), a proportion significantly lower than that in the Yangtze River (20–25%)28 and the Pearl River (~20%)26. This might be due to the low nutritional status29 consistent with the Yellow River’s limited autochthonous production (Supplementary Fig. S6a).

POM content and composition during WSRS

Three fluorescent components were identified in POM through EEMs-PARAFAC analysis: two humic-like substances (C4 and C5) and one protein-like component (C6) (Supplementary Fig. S3). Components C4 (41.15 ± 8.78%) and C5 (34.54 ± 8.24%) exhibited spectral similarities to DOM-derived C2 and C1, respectively, but with blue-shifted excitation/emission maxima, a pattern indicative of photodegradation-induced molecular modification30. The protein-like component C6 accounts for 24.31 ± 16.14% of total fluorescence (Fig. 2d). Chromophoric POM (C-POM) and fluorescent POM (F-POM) abundances were stable during WRP but rose sharply in SFP, corresponding with SSC trends (Fig. 2c, d). Notably, C-POM and F-POM intensities were approximately one order of magnitude lower than CDOM and FDOM (Fig. 2e–g), respectively, a phenomenon consistent with previous studies31.

Principal component analysis of DOM during WSRS

Principal component analysis (PCA) of 22 DOM parameters (including optical and molecular parameters) was employed to elucidate the temporal variations in DOM composition during the WSRS. The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) collectively accounted for 66.9% of the total variance (Fig. 4). PC1 (47.8%) exhibited strong positive loadings for aromaticity index (AI), humification degree (HIX), and oxygen-rich compounds (O/C), aromatic compounds (polyphenols+polycyclic aromatics, Polys+PCAs), but negative loadings for hydrogen-rich aliphatics (H/C), freshness indices (biological index (BIX), fluorescence index (FI)), and labile compounds (saturated compounds+unsaturated aliphatic compounds, SAT+UAC). Critically, samples segregated along the PC1 axis: WRP samples (623, 627, 702, 704) clustered in the negative PC1 domain with higher H/C, CHO, highly unsaturated compounds (HUC), and SAT+UAC, whereas SFP samples (710, 711) occupied the positive PC1 domain with elevated O/C, Poly + PCAs, HIX, AI, double bound equivalent (DBE), and CHOS. This demonstrates that DOM in WRP is characterized by autochthonous features and high hydrogen saturation, while DOM in SFP displays stronger terrestrial signatures with enhanced humification and aromaticity.

Discussion

DOM source dynamics and chemical evolution under WSRS

As the terminal segment of rivers before entering the sea, estuaries typically contain organic matter from multiple sources including terrestrial, autochthonous, and anthropogenic inputs32. The δ13C values of SPE-DOM ranged from –27.2‰ to –26.5‰ (Supplementary Fig. S5b), indicating the main resources are metabolism or residue of aquatic macrophytes and C3 plants33. Optical parameters provided preliminary evidence for multiple sources of DOM in Yellow River Mouth (YRM). The FI range (1.26–1.71) in YRM suggests mixed allochthonous and autochthonous DOM inputs (Supplementary Fig. S5c). This classification follows established thresholds: FI > 1.9 indicates autochthonous (microbial or algal), FI < 1.4 indicates allochthonous (terrestrial), and FI 1.4-1.9 indicates mixed sources34. SR (Fig. 2f, 0.29-1.40) and HIX (Fig. 2h, 1.09–3.17) values further revealed that DOM in YRM originated from sources exhibiting a wide range of aromaticity and humification degree35,36. Consistent with established molecular metrics37, the wide AI (Fig. 3e, 0.25–0.29) and DBE (Fig. 3f, 8.10–8.91) ranges, reflecting aromaticity and unsaturation, support diverse DOM sources in YRM.

Humic-like component C1 and C2 are widely distributed in rivers, estuaries and coastal zones, showing high spatial variability38,39. In this study, these two compounds are primarily derived from terrestrial sources according to the comparison with Open Fluor (Supplementary Table S2), correlation with other parameters and the characteristics of YRM (Supplementary Fig. S2) and the implementation process of WSRS (Supplementary Fig. S1). A detailed account of the reasoning is available in Supplementary Information Section 2, Supplementary Discussion. Further, FT-ICR MS detection of lignin and tannins, associated with vascular plant-derived organic matter and lignin degradation products, provides additional evidence for terrestrial organic matter input (Supplementary Fig. S6f, g)40. In parallel, the BIX (Supplementary Fig. S5d, 0.88–1.07), an autotrophic productivity indicator, confirms autochthonous DOM in the YRM41. The protein-like component C3 is associated with autochthonous production, such as the degradation of microalgae (Supplementary Table S2)42,43. The detection of SAT and UAC by FT-ICR MS indicated that bacterial and algal-derived OM contributed to DOM in YRM as well (Fig. 3i)44,45. Notably, anthropogenic influence was marked by O3S and O5S compounds (Supplementary Table S4). O3S compounds are associated with linear alkylbenzene-sulfonates (LAS), a major surfactant group46. O5S compounds are further linked to sulfophenyl carboxylic acids, aerobic degradation products of LAS47. Both compound classes, previously documented in anthropogenically impacted waters48,49, serve as indicators of anthropogenic influence.

The WSRS induced a phased transformation in the sources and chemical composition of DOM within the YRM. During WRP, elevated BIX (Supplementary Fig. S5d) and decreased HIX (Fig. 2h) values coupled with increased SAT+UAC abundance (Fig. 3i) provided complementary evidence for enhanced autochthonous DOM production50. PCA further revealed that the WRP samples contained DOM richer in hydrogen and more microbially labile (Fig. 4). Furthermore, van Krevelen (VK) diagrams of unique molecular formulas for each stage showed that the WRP water contained a greater number of unique CHON formulas compared to pre-WSRS periods (Fig. 5). Collectively, these results demonstrate the mediated of DOM by autotrophic plankton and heterotrophic bacterioplankton51,52. In contrast, during SFP, the system exhibited reversed trends. Specifically, terrestrial contributions were observed to be higher than those during WRP. Rebound in humic-like components (C1, C2; Fig. 1g) and plant-derived markers (lignin and tannins: Supplementary Fig. S6f, g) demonstrated the terrestrial dominance39,53, while declining BIX (Supplementary Fig. S5d) and the relative intensity of SAT+UAC (Fig. 3i) corroborated diminished autochthonous contributions41,50,54. After that, HIX increased and reached the highest value during the entire observation process, indicating the raising humification degree (Fig. 2h). Moreover, both DBE (p < 0.01; in WRP, 8.32 ± 0.16; in SFP, 8.77 ± 0.19) and AI (p < 0.01; in WRP, 0.26 ± 0.01; in SFP, 0.28 ± 0.01) exhibited similar patterns of change and displayed higher values in SFP (Fig. 3e, f), indicating a higher aromaticity degree of DOM55,56. Furthermore, O3S and O5S levels remained stable during WSRS (Supplementary Table S4), indicating consistent anthropogenic DOM contributions.

a Unique CHO compounds, b unique CHON compounds, c unique CHOS compounds, and d unique CHONS compounds in pre-WSRS, respectively; e unique CHO compounds, f unique CHON compounds, g unique CHOS compounds, and h unique CHONS compounds in WRP, respectively; i unique CHO compounds, j unique CHON compounds, k unique CHOS compounds, and l unique CHONS compounds in SFP, respectively.

Hydraulic management control DOM chemistry and carbon remobilization

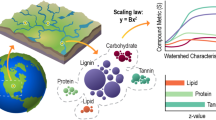

Following the initiation of WSRS, clear water was released from the XR, with discharge rapidly increasing from 340 m³ s–1 on June 23rd to 1465 m³ s–1, and subsequently peaking at 3990 m³ s–1 by July 2nd. The regulation lasted 17 days (June 23rd–July 9th). The clear water flow scoured the downstream riverbed, transporting coarse-grained sediments to the sea (Supplementary Fig. S1). During the SFP, although discharge decreased from 3935 m³ s–1 to 2500 m³ s–1 by July 10th, sediment concentration surged from 4.69 kg m-³ to 31 kg m-³ (Fig. 2a), forming a high-density turbidity current57. Notably, the median sediment grain size during this phase was reduced compared to the WPR (Supplementary Fig. S8). Numerous reservoir studies have demonstrated that mid- and deep-layer DOM is predominantly terrestrial-derived and refractory, while surface-layer DOM is primarily autochthonous and labile8,10. During reservoir impoundment periods, vertical DOM differentiation is mainly controlled by: primary production and photodegradation in surface waters, density current-driven intrusion of mainstream waters into intermediate layers, and microbial degradation in bottom waters58,59. By integrating these mechanisms with WSRS operational phases, we hypothesize that DOM composition and properties in the Yellow River mouth were primarily influenced by the release of distinct water layers from XR. Our observational data strongly support this hypothesis and we developed a conceptual model to elucidate the mechanistic impacts of the WSRS on DOM dynamics in YRM (Fig. 6).

The Water Release Phase (WRP) involved discharging water from the Xiaolangdi Reservoir to lower its water level and erode the riverbed in the lower reaches, which led to a rapid increase in the flow rate (WF). Subsequently, during the Sediment Flushing Phase (SFP), floodwater was released from upstream to scour previously deposited sediment from the reservoir. This process transported the highly concentrated sediment downstream, resulting in a sharp rise in the suspended sediment concentration (SSC).

During WRP, XR discharged large volumes of clear water reaching YRM within 3 days (Fig. 1b). Elevated proportions of SAT and UAC appeared immediately after release (Fig. 3i), despite significantly lower chlorophyll a (Chl a) concentrations in YRM versus non-WSRS periods (Supplementary Fig. S5a) indicating reduced primary productivity. This indicated the source of DOM originated from XR rather than local production. From April to October, XR developed thermal stratification, with the maximum temperature difference between surface and bottom water layers reaching 12 °C60,61. Prior to the WSRS initiation, prolonged water impoundment in XR resulted in vertical differentiation of DOM. DOM in YRM exhibited an increase in bio-labile compounds (such as lipids and proteins) (Supplementary Fig. S6) and decreases in humification degree (evidences by HIX, AI, and DBE) (Figs. 2 and 3)55,56,62. The rapid short-term transport mechanism suppressed in-transit degradation (e.g., photochemical and microbial processes), enabling direct delivery of bioreactive DOM from the surface of XR to the YRM. Li63 also found that DOM in the surface waters of XR was influenced by microbial processing and photodegradation, and contained a higher proportion of bio-labile components with lower humification levels.

In the later stage of WRP, the relative abundance of DOM increased (Fig. 2e–g), accompanied by a rise in HIX (Fig. 2h), which indicated higher humification degree. The increase of SR (Fig. 2f) and decrease of m/z (Fig. 3b) indicated the photo-degradation of DOM64,65. Prior to WSRS implementation, the impoundment period facilitated the vertical stratification of organic matter, with bio- and photo-degradation products accumulating preferentially in intermediate water layers, while deep-layer DOM became increasingly dominated by refractory biodegradation derivatives. Consequently, as reservoir waters were discharged, YRM DOM progressively exhibited higher humification indices and lower biological reactivity (Fig. 2h; Supplementary Fig. S5d).

Further, during WRP, the channel erosion downstream the XR mostly derived coarser sediment. The increased SSC could promote the exchange from DOM to POM66,67. Mcknight et al.68 found that 40% of the DOM is removed by adsorption onto minerals in the Snake River in Colorado (USA). Zhang et al.69 found a negative correlation between POC and DOC during WRP, which indicated that the decrease in DOC content was influenced by the adsorption of coarse sediment on DOC at this time. We also found a negative correlation between POC and DOC although have no significance (Supplementary Fig. S2). This might because of the influence by the sample size.

Transitioning to the SFP, fine-grained sediments deposited in XR were resuspended, releasing organic matter previously sequestered in the reservoir bottom63,70. This release corresponded with an increased relative abundance of aromatic compounds and sulfur-containing compounds (Fig. 3h–k; Supplementary Fig. S6h). Anaerobic environments (e.g., wetlands, sediments, and hypoxic water bodies) serve as critical sites for sulfur-containing compound formation71. During the SFP, resuspension processes mobilize dissolved sulfur-containing organics, produced via early diagenesis in sediment pore waters, into the overlying water column, driving a significant increase in the proportion of sulfur-containing compounds (Fig. 3h). Notably, while total sulfur-containing compounds increased, the relative abundances of O3S and O5S showed no rise (Supplementary Table S4). This paradox indicates an emergent source of sulfur compounds. As highly oxidized sulfonates typically derived from detergent and paper manufacturing byproducts, O3S and O5S are established tracers of anthropogenic DOM inputs24. Here, the significant decline in the O3S+O5S/CHOS ratio during SFP (Supplementary Table S4) confirms that the sulfur increase originated not from industrial sources but from sediment resuspension, where disturbance of fine-grained sediments in reservoir bottoms released pore-water sulfur compounds into the water column, transporting them to the YRM. VK diagrams further revealed that sediment flushing samples exhibited lower H/C and higher O/C ratios (Fig. 3c, d), indicative of DOM dominated by more oxidized, mineralized organic material72. While DOM released from the reservoir would typically undergo photodegradation and biodegradation during downstream transport, these processes were likely suppressed during WSRS. High turbidity from suspended sediments reduced light penetration (inhibiting photodegradation) and limited microbial activity (inhibiting biodegradation)27,73. Consequently, during SFP, DOM exhibited synchronous decreases in BIX, H/C, SAT+UAC, alongside increases in HIX, O/C, m/z, AI, DBE and Poly+PCAs (Figs. 2 and 3). These shifts collectively indicate enhanced terrestrial inputs and reduced autochthonous DOM contributions.

To further verify that the properties of DOM in the YRM are primarily influenced by water released from different depth layers of XR, we conducted a comparative study on the vertical differentiation of DOM molecular characteristics in various global aquatic ecosystems (rivers, lakes, and reservoirs) (Supplementary Fig. S9). The results suggest a significant positive correlation between DBE and m/z, with all ecosystems (lakes, rivers, and reservoirs) showing an increasing DBE trend from surface to bottom layers. These findings further demonstrate that the release of water from distinct reservoir layers during WSRS directly drives the observed variations in DOM composition and properties in YRM.

Implications for the global carbon cycle on the estuary

As the dominant form of reactive carbon, DOM plays a crucial role in regional carbon cycling74. The phased operational dynamics of WSRS drive significant shifts in the composition of DOM in the YRM, which will have cascading implications for ecosystem stability and global carbon cycling. During the WRP, surface water discharges transport bioavailable organic matter to the YRM. These compositional shifts disrupt riverine ecosystem equilibrium, as labile DOM inputs during WRP may exacerbate estuarine eutrophication through microbial mineralization of substrates like amino acids and carbohydrates75 a phenomenon corroborated by post-WSRS algal bloom events76. Labile organic compounds in aquatic systems could play an important role in controlling the transport of carbon from water to the air77. Bio-degradation will finally generate labile organic carbon in to inorganic carbon78. The utilization of DOM by microorganisms could release CO2, which promotes the emission of carbon from the water to the atmosphere79.

In contrast, the subsequent SFP mobilizes intermediate-depth turbid plumes enriched with aromatic DOM. The aromatic DOM introduced during SFP exhibits pronounced photo-lability. After arriving at the river mouth, aromatic compounds in freshwater will be further transported to the sea. Due to the decrease in water turbidity in this process, the aromatic compounds could be removed by photo-bleaching80. The oxidative degradation process of organic matter induced by light is irreversible and ultimately leads to the formation of CO281. Photodegradation of these compounds generates CO₂ emissions while yielding refractory residues10,77,82, creating a dual carbon fate: short-term atmospheric release and long-term sequestration of photo-resistant macromolecules. This duality complicates carbon budgeting in coastal zones, where both CO₂ outgassing and recalcitrant carbon burial must be quantified.

The modern river-to-estuary carbon flux is 0.78 ± 0.41 Pg C yr⁻¹, with 0.65 ± 0.30 Pg C yr⁻¹ of this flux outgassed back to the atmosphere through estuarine processes83. However, their estimates did not account for the quantitative impacts of anthropogenic interventions, such as hydraulic engineering projects. Globally, over 60,000 large dams (International Commission on Large Dams, ICOLD, 2022) likely exert analogous carbon-climate feedbacks through reservoir drawdowns. The WSRS case study demonstrates that such operations mobilize aged terrestrial carbon into fluvial networks16,69, a process hitherto underrepresented in land-ocean carbon models5. The remobilization of ancient organic matter underscores the need to integrate reservoir management impacts into global CO₂ flux assessments. Future strategies must reconcile hydraulic objectives (e.g., flood control, sediment scouring) with carbon legacy mitigation, particularly in sediment-laden systems like the Yellow River. Proactive measures, such as timing SFP to avoid peak sunlight periods or optimizing sediment grain size thresholds, could minimize unintended carbon emissions while maintaining ecological resilience in downstream and estuarine habitats.

While this study provides insights into reservoir-regulated DOM dynamics, certain limitations warrant attention in future work. Specifically, incorporating in situ degradation assays in subsequent research will establish a more robust foundation for understanding how WSRS operations alter DOM composition in the YRM. Additionally, concurrent sampling of XR during WSRS implementation would further illuminate its role in shaping estuarine DOM characteristics.

Conclusions

Based on the bulk, optical and molecular parameters, obviously changing trend in organic matter chemistry can be revealed during the implementation of WSRS. The concentration of POC and POM keep stabile in WRP, but increased significantly in SFP. Although DOC fluctuate greatly during WSRS, the composition and properties of DOM responds to different stages of WSRS at the spectral and mass spectrometry levels. In WRP, relative more labile compounds of DOM, with lower aromaticity and humification degree were observed than pre-WSRS and SFP. The significant variation of DOM chemistry was mainly caused by the release of fresh water from the surface of XR. The increased proportion of labile compounds in the river mouth might promote the growth of heterotrophs in the Yellow River estuary, thereby facilitating the conversion of organic matter to inorganic carbon. In SFP, relatively more sedimentary organic matter with higher aromaticity and humification degree DOM were observed. These variations mainly resulted from the re-suspension and release of sediments from XR. WSRS promoted the release of aromatic compounds which vulnerable to be photo-degraded, directly increased the relative abundance of organic matter in the river mouth. After reaching the estuary, because of the decrease of water turbidity, aromatic compounds may be further utilized and induce the proliferation of biological communities or the release of CO2. This study deepens our understanding of the environmental behavior of DOM during WSRS and provides valuable insights for engineering improvement and protection of estuarine ecosystems. Given that over 63% of global rivers are dam-regulated, this work serves as a model for assessing the cascading impacts of hydraulic engineering on coastal carbon cycles.

Methods

Sample collection

Surface water samples were collected twice daily (07:00 and 17:00) from June 21st to July 12th, 2022 (n = 43), at a fixed station downstream of Lijin station (37°45′42.57″N, 118°59′9.14″E), located in the YRM (Fig. 1a). The WSRS comprises two sequential phases13: (1) the WRP, during which high-velocity discharges from XR scour coarse sediment (0.035–0.040 mm) from the riverbed, and (2) the SFP, where controlled releases from Sanmenxia reservoir mobilize fine-grained sediments (0.006–0.010 mm) deposited at the XR bottom to increase reservoir storage capacity (Fig. 1b). Detailed operational parameters for the 2022 WSRS are provided in Supplementary Information.

Surface water (0–0.5 m depth) was collected from a bridge-mounted platform using precleaned stainless-steel buckets rinsed three times with in situ water. Immediately after collection (<20 min transport time), samples were filtered sequentially through pre-combusted (450 °C, 4 h) 0.7 μm glass fiber filters (Whatman GF/F) and 0.2 μm membrane filters (Millipore) to separate particulate and dissolved fractions. Filtered aliquots for DOM analysis were stored in acid-washed (5%, 24 h) amber glass bottles at 4 °C until further processing. Another 800 mL filtered water samples were extracted by solid phase extraction (SPE) cartridge (Agilent Bond Elut PPL, 500 mg, 6 mL) for SPE-DOM mass spectrum analysis37. Samples were stored at –20 °C in the dark until laboratory analysis. Detailed methodological descriptions of the sampling procedures are provided in Supplementary Information.

Physicochemical parameters (including water temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen (DO), and pH) were measured on-site using a calibrated multi-parameter water quality sonde (YSI ProQuatro, USA). Chl a concentration was determined by filtering 500 mL of water onto GF/F filters, followed by cold acetone extraction (24 h, 4 °C) and quantification using a Trilogy fluorometer (Turner Designs, USA) calibrated in the laboratory.

DOM analysis

Both chromophoric DOM (CDOM) and fluorescent DOM (FDOM) were analyzed via a synchronous absorption-fluorescence spectrometer (Aqualog-UV-800-C, Horiba Aqualog, Japan). PARAFAC was used to decompose the EEM dataset into individual fluorescent components84. Various optical parameters, including the absorption coefficient a35035, fluorescence index (FI)34, biological index (BIX)41, and humification index (HIX)41 were calculated.

Solid-phase extracted DOM (SPE-DOM) was analyzed via a 7 Tesla FT-ICR MS (SolariX 2XR, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) in negative electrospray ionization (ESI) mode. Prior to analysis, methanol extracts of SPE-DOM were diluted to a final DOC concentration of 50–100 mg C L–1 to optimize ionization efficiency. The extraction efficiency of the PPL cartridges ranged from 50% to 70%, as determined by DOC recovery72. Samples were infused at a flow rate of 220 μL h-1, and mass spectra were acquired over a range of m/z 150–1000 with 256 accumulated scans per run85. Peaks were retained only if they met the following criteria: signal-to-noise ratio >8, mass measurement error < ±0.1 ppm. Double bond equivalent (DBE=C-0.5H+O.5N+1) and modified aromaticity index (AI, (1+C-0.5O-S-0.5H)/(C-0.5O-S-N))55,56 were calculated to indicate the aromaticity of DOM compounds. Assigned molecular formulae were classified into distinct biochemical categories (e.g., lipids, proteins, carbohydrates) based on their elemental ratios and functional group signatures, as detailed in Supplementary Table S3.

The bulk δ13C of SPE-DOM was determined using a Finnigan MAT 253 isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). δ13C values were reported relative to Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) with a precision of ±0.2‰. Detailed protocols for parameters calculation methods and molecular formula assignment are provided in Supplementary Information.

POM analysis

Particulate organic matter (POM) was alkali extraction from the filtered 0.7-μm glass fiber according to the procedures described in Osburn et al.31. Chromophoric POM (C-POM) and fluorescent POM (F-POM) were quantified using a synchronized absorption-fluorescence spectrometer (Aqualog-UV-800-C, Horiba Aqualog, Japan). Absorbance spectra and excitation-emission matrices were acquired under identical instrumental settings to those used for DOM analysis. Detailed protocols for POM extraction, spectral processing, and quality control are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Data analysis

Temporal variations in DOM characteristics were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s test (α = 0.05). PCA was performed on z-score normalized optical and molecular parameters to visualize DOM compositional differences across operational phases (pre-WSRS, WRP and SFP). The figures and diagrams were prepared in ArcGIS10.2 and R4.1.2, and the ± notation represents the standard deviation if not otherwise mentioned. Details about the instrument calibration and data quality control can be found in Supplementary Information.

Data availability

The data used in this study are in Microsoft Excel format and are accessible via Figshare at DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.30121969. The basin relief dataset (Fig. 1) was obtained from the National Cryosphere Desert Data Center and is available at http://www.ncdc.ac.cn. Real-time data of daily water flow and suspended sediment concentration at Xiaolangdi and Lijin stations are available at http://www.yrcc.gov.cn/zxfw/sqsz/.

References

Hansell, D. A. & Orellana, M. Dissolved organic matter in the global ocean: a primer. Gels 7, 128 (2021).

Best, J. Anthropogenic stresses on the world’s big rivers. Nat. Geosci. 12, 7–21 (2019).

Grill, G. et al. Mapping the world’s free-flowing rivers. Nature 569, 215–221 (2019).

Tranvik, L. J. et al. Lakes and reservoirs as regulators of carbon cycling and climate. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 2298–2314 (2009).

Bianchi, T. S. et al. Anthropogenic impacts on mud and organic carbon cycling. Nat. Geosci. 17, 287–297 (2024).

Maavara, T. et al. River dam impacts on biogeochemical cycling. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 103–116 (2020).

Wang, K. et al. Three Gorges Reservoir construction induced dissolved organic matter chemistry variation between the reservoir and non-reservoir areas along the Xiangxi tributary. Sci. Total Environ. 784, 147095 (2021).

Yi, Y. B. et al. Assessing the impacts of reservoirs on riverine dissolved organic matter: insights from the largest reservoir in the Pearl River. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 129, 8 (2024).

Cole, J. J. et al. Plumbing the global carbon cycle: integrating inland waters into the terrestrial carbon budget. Ecosystems 10, 172–185 (2007).

Wang, K., Li, P. H., He, C., Shi, Q. & He, D. Density currents affect the vertical evolution of dissolved organic matter chemistry in a large tributary of the Three Gorges Reservoir during the water-level rising period. Water Res. 204, 117609 (2021).

Acharya, S. et al. Relevance of tributary inflows for driving molecular composition of dissolved organic matter (DOM) in a regulated river system. Water Res. 237, 119975 (2023).

Chen, M. et al. Unique characteristics and spatiotemporal variations of dissolved organic matter along the Yeongsan River estuary impacted by an estuary dam. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 313, 109081 (2025).

Wang, H. J. et al. Impacts of the dam-orientated water-sediment regulation scheme on the lower reaches and delta of the Yellow River (Huanghe): a review. Glob. Planet Change 157, 93–113 (2017).

Bi, N. S. et al. Response of channel scouring and deposition to the regulation of large reservoirs: a case study of the lower reaches of the Yellow River (Huanghe). J. Hydrol. 568, 972–984 (2019).

Xia, X. H. et al. Effect of water-sediment regulation of the Xiaolangdi reservoir on the concentrations, characteristics, and fluxes of suspended sediment and organic carbon in the Yellow River. Sci. Total Environ. 571, 487–497 (2016).

Yu, M. et al. Impacts of natural and human-induced hydrological variability on particulate organic carbon dynamics in the Yellow River. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 1119–1129 (2019).

Tao, S. Q. et al. Temporal variability in composition and fluxes of Yellow River particulate organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr. 63, S119–S141 (2018).

Li, X., Chen, H., Jiang, X., Yu, Z. & Yao, Q. Impacts of human activities on nutrient transport in the Yellow River: the role of the Water-Sediment Regulation Scheme. Sci. Total Environ. 592, 161–170 (2017).

Dong, J. W. et al. Effect of water-sediment regulation of the Xiaolangdi Reservoir on the concentrations, bioavailability, and fluxes of PAHs in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River. J. Hydrol. 527, 101–112 (2015).

Wang, Y. J. et al. Impact of water-sediment regulation scheme on seasonal and spatial variations of biogeochemical factors in the Yellow River estuary. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 198, 92–105 (2017).

Park, J. H. et al. Reviews and syntheses: Anthropogenic perturbations to carbon fluxes in Asian river systems - concepts, emerging trends, and research challenges. Biogeosciences 15, 3049–3069 (2018).

Maavara, T., Lauerwald, R., Regnier, P. & Van Cappellen, P. Global perturbation of organic carbon cycling by river damming. Nat. Commun. 8, 15347 (2017).

D’Andrilli, J., Silverman, V., Buckley, S. & Rosario-Ortiz, F. L. Inferring ecosystem function from dissolved organic matter optical properties: a critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 11146–11161 (2022).

Shi, W. X., Zhuang, W. E., Hur, J. & Yang, L. Y. Monitoring dissolved organic matter in wastewater and drinking water treatments using spectroscopic analysis and ultra-high resolution mass spectrometry. Water Res. 188, 116406 (2021).

Zark, M. & Dittmar, T. Universal molecular structures in natural dissolved organic matter. Nat. Commun. 9, 3178 (2018).

He, C. et al. Molecular composition and spatial distribution of dissolved organic matter (DOM) in the Pearl River Estuary, China. Environ. Chem. 17, 240–251 (2020).

Zhou, Y. P. et al. Spatial changes in molecular composition of dissolved organic matter in the Yangtze River Estuary: implications for the seaward transport of estuarine DOM. Sci. Total Environ. 759, 143531 (2021).

Zhou, Y. P. et al. Characterization of dissolved organic matter processing between surface sediment porewater and overlying bottom water in the Yangtze River Estuary. Water Res. 215, 118260 (2022).

Zhao, C. et al. Unraveling the photochemical reactivity of dissolved organic matter in the Yangtze river estuary: Integrating incubations with field observations. Water Res. 245, 120638 (2023).

Zhao, C. et al. Exploring the complexities of dissolved organic matter photochemistry from the molecular level by using machine learning approaches. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 17889–17899 (2023).

Osburn, C. L., Handsel, L. T., Mikan, M. P., Paerl, H. W. & Montgomery, M. T. Fluorescence tracking of dissolved and particulate organic matter quality in a river-dominated estuary. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 8628–8636 (2012).

Canuel, E. A. & Hardison, A. K. Sources, ages, and alteration of organic matter in estuaries. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 8, 409–434 (2016).

Jaffé, R. et al. Dissolved organic matter in headwater streams: compositional variability across climatic regions of North America. Geochim Cosmochim. Acta 94, 95–108 (2012).

McKnight, D. M. et al. Spectrofluorometric characterization of dissolved organic matter for indication of precursor organic material and aromaticity. Limnol. Oceanogr. 46, 38–48 (2001).

Stedmon, C. A. & Markager, S. Behaviour of the optical properties of coloured dissolved organic matter under conservative mixing. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 57, 973–979 (2003).

Ohno, T. Fluorescence inner-filtering correction for determining the humification index of dissolved organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 742–746 (2002).

Dittmar, T., Koch, B., Hertkorn, N. & Kattner, G. A simple and efficient method for the solid-phase extraction of dissolved organic matter (SPE-DOM) from seawater. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 6, 230–235 (2008).

Ohno, T. & Bro, R. Dissolved organic matter characterization using multiway spectral decomposition of fluorescence landscapes. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 70, 2028–2037 (2006).

Ishii, S. K. L. & Boyer, T. H. Behavior of reoccurring PARAFAC components in fluorescent dissolved organic matter in natural and engineered systems: a critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 2006–2017 (2012).

Medeiros, P. M. et al. A novel molecular approach for tracing terrigenous dissolved organic matter into the deep ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 30, 689–699 (2016).

Huguet, A. et al. Properties of fluorescent dissolved organic matter in the Gironde Estuary. Org. Geochem. 40, 706–719 (2009).

Stedmon, C. A. et al. Dissolved organic matter (DOM) export to a temperate estuary: seasonal variations and implications of land use. Estuaries Coasts 29, 388–400 (2006).

Korak, J. A. & McKay, G. Meta-analysis of optical surrogates for the characterization of dissolved organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 7380–7392 (2024).

Seidel, M. et al. Molecular-level changes of dissolved organic matter along the Amazon River-to-ocean continuum. Mar. Chem. 177, 218–231 (2015).

Kellerman, A. M. et al. Unifying concepts linking dissolved organic matter composition to persistence in aquatic ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 2538–2548 (2018).

Gonsior, M. et al. Molecular characterization of effluent organic matter identified by ultrahigh resolution mass spectrometry. Water Res. 45, 2943–2953 (2011).

Chen S. et al. Elucidating dissolved organic sulfur in the coastal environment by improved online liquid chromatography coupled to FT-ICR mass spectrometry. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 129, 2 (2024).

Yao, W. et al. Seasonal variation and dissolved organic matter influence on the distribution, transformation, and environmental risk of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in coastal zone: a case study of Tianjin, China. Water Res. 249, 120881 (2024).

Niu, D. et al. The impact of water-sediment regulation scheme (WSRS) on the chemistry of dissolved organic matter in the Yellow River estuary and adjacent waters. Water Res. 282, 123669 (2025).

Zhao C. et al. Machine learning models for evaluating biological reactivity within molecular fingerprints of dissolved organic matter over time. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, 11 (2024).

Bronk, D. A., See, J. H., Bradley, P. & Killberg, L. DON as a source of bioavailable nitrogen for phytoplankton. Biogeosciences 4, 283–296 (2007).

Letscher, R. T. & Aluwihare, L. I. A simple method for the quantification of amidic bioavailable dissolved organic nitrogen in seawater. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 22, 451–463 (2024).

An, S. L. et al. Long-term photochemical and microbial alterations lead to the compositional convergence of algal and terrestrial dissolved organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 18765–18776 (2024).

D’Andrilli, J., Cooper, W. T., Foreman, C. M. & Marshall, A. G. An ultrahigh-resolution mass spectrometry index to estimate natural organic matter lability. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 29, 2385–2401 (2015).

Koch, B. P. & Dittmar, T. From mass to structure: an aromaticity index for high-resolution mass data of natural organic matter. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 20, 926–932 (2006).

Koch, B. P. & Dittmar, T. From mass to structure: an aromaticity index for high-resolution mass data of natural organic matter (vol 20, pg 926, 2006). Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 30, 250–250 (2016).

Yang, H. et al. Episodic reservoir flooding transforming sediment sinks to sources and the potential global implications. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 658 (2025).

Wang, K. et al. Response of dissolved organic matter chemistry to flood control of a large river reservoir during an extreme storm event. Water Res. 230, 119565 (2023).

Yi, Y. et al. The influence of the deep subtropical reservoir on the karstic riverine carbon cycle and its regulatory factors: Insights from the seasonal and hydrological changes. Water Res. 226, 119267 (2022).

Yi-hui, Z. & Yong, P. Study on water temperature of Xiaolangdi reservoir based on EFDC Model. Sichuan Environ. 36, 24–31 (2017).

Xin-Ying, H. et al. Controls on Spatial-temporal variation of hydrological features in the Xiaolangdi Reservoir. Period. Ocean Univ. China 50, 111–120 (2020).

Xu, H. & Guo, L. Intriguing changes in molecular size and composition of dissolved organic matter induced by microbial degradation and self-assembly. Water Res. 135, 187–194 (2018).

Li, W. et al. Influence of water-sediment regulation on dissolved organic matter in Xiaolangdi Reservoir of the Yellow River. Acta Sci. Circumst. 43, 216–225 (2022).

Helms, J. R. et al. Absorption spectral slopes and slope ratios as indicators of molecular weight, source, and photobleaching of chromophoric dissolved organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr. 53, 955–969 (2008).

Zhang, M. Z. et al. Dynamic distribution and photochemical-microbial coupling degradation of dissolved organic matter in a large river-influenced Bay. Mar. Chem. 260, 104366 (2024).

Moreira-Turcq, P. F., Seyler, P., Guyot, J. L. & Etcheber, H. Characteristics of organic matter in the mixing zone of the Rio Negro and Rio Solimoes of the Amazon River. Hydrol. Process 17, 1393–1404 (2003).

Remington, S. M., Strahm, B. D., Neu, V., Richey, J. E. & da Cunha, H. B. The role of sorption in control of riverine dissolved organic carbon concentrations by riparian zone soils in the Amazon basin. Soil Sci. 172, 279–291 (2007).

Mcknight, D. M. et al. Sorption of dissolved organic-carbon by hydrous aluminum and iron-oxides occurring at the confluence of deer creek with the Snake River, Summit County, Colorado. Environ. Sci. Technol. 26, 1388–1396 (1992).

Zhang, L. J., Wang, L., Cai, W. J., Liu, D. M. & Yu, Z. G. Impact of human activities on organic carbon transport in the Yellow River. Biogeosciences 10, 2513–2524 (2013).

Li, W., Sen, L., Jia-zhi, Y., Meng-yuan, L. & Miao, C. Study on the adsorption characteristics of dissolved organic matter by suspended sediment in Xiaolangdi Reservoir. J. Sediment. Res. 50, 37–43 (2025).

Ibrahim, H. & Tremblay, L. Origin of dissolved organic sulfur in marine waters and the impact of abiotic sulfurization on its composition and fate. Mar. Chem. 254, 104273 (2023).

Ge, J. F. et al. Fluorescence and molecular signatures of dissolved organic matter to monitor and assess its multiple sources from a polluted river in the farming-pastoral ecotone of northern China. Sci. Total Environ. 837, 154575 (2022).

Cloern, J. E. Turbidity as a control on phytoplankton biomass and productivity in estuaries. Cont. Shelf Res. 7, 1367–1381 (1987).

Stukel, M. R. et al. Carbon sequestration by multiple biological pump pathways in a coastal upwelling biome. Nat. Commun. 14, 2024 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Labile dissolved organic matter (DOM) and nitrogen inputs modified greenhouse gas dynamics: A source-to-estuary study of the Yangtze River. Water Res. 253, 121318 (2024).

Zhang, J. J. et al. Impact of the Water-Sediment Regulation Scheme on the phytoplankton community in the Yellow River estuary. J. Clean. Prod. 294, 126291 (2021).

He, D. et al. Hydrological management constraints on the chemistry of dissolved organic matter in the Three Gorges Reservoir. Water Res. 187, 116413 (2020).

Yuan, Z. et al. Molecular insights into the transformation of dissolved organic matter in landfill leachate concentrate during biodegradation and coagulation processes using ESI FT-ICR MS. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 8110–8118 (2017).

Yang, M. et al. Stepwise degradation of organic matters driven by microbial interactions in China΄s coastal wetlands: Evidence from carbon isotope analysis. Water Res. 250, 121062 (2024).

Fu, X., Du, H. & Xu, H. Comparison in UV-induced photodegradation properties of dissolved organic matters with different origins. Chemosphere 280, 130633 (2021).

Qu, L. et al. Hypolimnetic deoxygenation enhanced production and export of recalcitrant dissolved organic matter in a large stratified reservoir. Water Res. 219, 118537 (2022).

Kteeba, S. M. & Guo, L. Photodegradation Processes and Weathering Products of Microfibers in Aquatic Environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 16535–16546 (2024).

Regnier, P., Resplandy, L., Najjar, R. G. & Ciais, P. The land-to-ocean loops of the global carbon cycle. Nature 603, 401–410 (2022).

Murphy, K. R., Stedmon, C. A., Graeber, D. & Bro, R. Fluorescence spectroscopy and multi-way techniques PARAFAC. Anal. Methods 5, 6557–6566 (2013).

Qi, Y. L. & O’Connor, P. B. Data processing in Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 33, 333–352 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) Shiptime Sharing Project (42149301) and NSFC project (U22A20607), and Technology Fundamental Resources Investigation Program of China (Grant No. 2022FY100300). We thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Donglei Niu and Jianhui Tang conceived and designed the research; Donglei Niu performed sampling, analyzed the sample data and wrote the original draft of the manuscript; Jianhui Tang acquired funding; Yang Tan, Yanan Li, Yanfang Li, Chao Ma, and Yulin Qi provided analytical infrastructure and protocols; all authors reviewed and commented on the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Maofei Ni and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Somaparna Ghosh [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, D., Tan, Y., Ma, C. et al. Reservoir artificial flood discharge is a critical driver for the compositional and functional shifts of dissolved organic matter in river mouth. Commun Earth Environ 6, 996 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02920-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02920-y