Abstract

Green space cooling is a nature-based solution to alleviate urban heat risk. However, the relationship between its cooling and urban development, particularly in the context of global economic differences, is poorly understood. Here, we examined the effect of the built-up environment on improving the cooling efficiency of green spaces in 1113 built-up areas. The average cooling efficiency of green spaces in the high-income countries globally is 1.64 times that in the low-income countries. In high-income countries, reducing built-up density and increasing building height can enhance the cooling efficiency of green spaces. Notably, maintaining built-up density below 20% enables relatively high cooling efficiency, regardless of variations in building height. In contrast, in most zones of low-income countries, controlling the low building height tends to achieve better cooling efficiency of green spaces. Our findings provide a scientific basis for optimizing green space layouts tailored to urban climate adaptation across different socio-economic regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The urbanization has led to changes in the properties of the underlying surface, especially as impermeable surfaces replace vegetation. Such a phenomenon has driven an increase in land surface temperature (LST) across urban areas, exerting adverse impacts on both urban social systems and ecosystems1,2,3,4. Different regions and countries are seeking scientifical strategies to mitigate rising temperatures. Nature-based solutions are considered as the effective means to enhance thermal comfort and alleviate heat stress5,6. As a key natural element, the positive impact of improving green spaces on regulating urban heat has been verified in multiple regions7,8,9.

Green spaces are areas of land covered by trees, grass, or other vegetation, which primarily reflect the characteristics of greenness10,11,12. The relationship between green space and LST is generally negative, indicating that LST decreases as urban vegetation coverage increases13,14. Extant research has revealed that green spaces worldwide provide substantial yet uneven urban cooling. The cooling effect depends on vegetation transpiration and the absorption and shading of solar radiation by tree canopies15. At the economic level, the unevenness of green space cooling is also affected by the level of urban development, with the cooling capacity of green spaces in the Global North confirmed to be 1.5-fold higher than in the Global South16. A study of 384 parks in five U.S. cities yielded average cooling intensities ranging from 2.93 to 6.84 °C, while a survey of 262 green spaces in Bangalore, India, yielded only 2.23 °C17,18. Urban socio-economic development determines the scale and structure of the built-up environment, thereby potentially influencing the surface energy balance within green spaces, indirectly altering the intensity and efficiency of vegetation cooling19. In cities with healthy development, economically mediated pathways could regulate the cooling capacity of green spaces, with interventions such as enhanced irrigation infrastructure to offset soil moisture deficits20, strategic selection of highevapotranspiration vegetation21, and rigorous maintenance to sustain canopy health11. Such advantages, which benefit from economic development, are magnified in climate-vulnerable areas where technological interventions contribute to the services from green spaces22. Therefore, even under similar climatic conditions, performance differences in green space cooling may exist between high-income and low-income countries. Consequently, exploring the heterogeneity of the cooling effect of green spaces in different economic groups is beneficial for the rational allocation of ecological spaces under limited budgets, thereby maximizing their effectiveness in regulating the urban thermal environment.

Built-up characteristics are important morphological descriptors of urban spatial development. Extensive research has demonstrated that variations in density and height of built-up environment are significantly correlated with LST patterns and the cooling capacity of green spaces across diverse urban contexts. For instance, studies conducted in three high-income Italian cities (Mediterranean climate) found that higher building density generally leads to elevated temperatures, while taller buildings enhance the cooling effect of vegetation23. While in the well-developed city of Guangzhou, China (humid subtropical climate), moderate building height combined with lower density significantly increases LST24. Another study in Xi’an, China demonstrated that building coverage ratio exerts a pronounced influence on LST, with high coverage masking the cooling benefits of green spaces25. These findings highlight the context-dependent relationships among the urban built-up environment and heat regulation of green spaces. However, considerable heterogeneity persists across different climatic and socio-economic settings, underscoring the lack of a comprehensive global analysis quantifying how the built-up environment jointly influences the cooling effect of green spaces.

Cooling efficiency (CE) is widely used to measure the positive impact of green spaces on urban LST12,15. CE is quantified as the reduced intensity of LST (°C) achieved by increasing the proportion of green space by one unit15. In this study, we focus on 1113 urban built-up areas worldwide, aiming to investigate how built-up density (BD) and building height (BH) influence the CE of green spaces across cities at different economic development levels. Specifically, we demonstrated: (1) nonlinear relationships of BD and BH with CE of green spaces, (2) optimal BD-BH thresholds for keeping higher CE of green spaces, and (3) underlying mechanisms of the effect of built-up environment on CE of green spaces.

Result

Global patterns on the CE of green spaces

We initially assessed the CE of green spaces in 1113 built-up areas worldwide (see Methods). The average CE across these global built-up areas is 0.117 °C (Supplementary Fig. S1), with high CE primarily concentrated in regions such as the eastern United States, central Europe, East Asia, and the coastal areas of eastern South America (Fig. 1a). In contrast, built-up areas with relatively low CE of green spaces are widely scattered across Africa and South Asia. The highest CE is observed in Asahikawa shi, Japan, reaching 0.379 °C, while the lowest CE (i.e., 0.008 °C) is found in Antananarivo, Madagascar.

CE of green spaces in 1113 built-up areas (a). Average CE in different zones, which are divided by four income groups and four Köppen-Geiger climate classifications (b). HIC, UMIC, LMIC, and LIC are indicated as countries in high income, upper-middle income, lower-middle income, and low income, respectively. A, B, C, and D are represented as the tropical, arid, temperate, and cold climates, respectively. Average CE and sample count of different sizes of built-up areas with latitude changes (c).

Based on national income levels and Köppen-Geiger climate classifications, we categorized all built-up areas into 16 groups to elucidate the relationship between economic development and CE of green spaces under similar climatic conditions (Supplementary Fig. S2, Table S1). At the global scale, the average CE of green spaces in the high-income countries (HICs) was 0.136 °C, which was about 1.64 times that in the low-income countries (LICs) (0.083 °C) (Fig. 1b). The disparity in green space cooling induced by economic development was even more pronounced in temperate zones. In the temperate climate, the average CE of green spaces in the HICs were about 1.81 times that in the LICs (0.141 °C and 0.078 °C, respectively). In tropical and cold climates, built-up areas with high average CE of green spaces consistently tended to be located in the upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) and the HICs (with average CEs of 0.123 °C and 0.142 °C in such two climate zones, respectively).

Moreover, urban agglomerations composed of multiple adjacent built-up areas typically exhibited higher CE of green spaces (Fig. 1c). For example, in the urban agglomeration of the Atlantic coast in the eastern United States, the Yangtze River Delta in China, the Pacific coast in Japan, and the Nile Delta in Egypt, the average CEs of green spaces all exceeded 0.15 °C. Notably, the Nile Delta, a typical arid region in the lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) (classified as LMIC-B), had an average CE of 0.178 °C in the built-up area. Meanwhile, urban agglomerations in other climatic conditions further confirmed the relationship between high levels of economic development and high CE of green spaces. The potential relationship may be caused by a more rational allocation of green spaces in well-developed cities or the larger scale of built-up areas where intensified human activities lead to a more substantial urban heat island effect, which indirectly enhances the CE of green spaces.

Nonlinear effects of the built-up environment on the CE of green spaces

Among all income groups, the HICs showed the lowest average BD and BH, at 24.19% and 6.75 m, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S3, Fig. S4). The average BH in the LICs reached 7.82 m, significantly higher than in the HICs. In comparison, the UMICs displayed the highest values for both average BH (8.48 m) and BD (27.40%). Furthermore, we employed generalized additive models (GAM) to fit the nonlinear effects of BD and BH on the CE of green spaces in different zones (see Methods).

The influence intensity of BD and BH on the CE of green spaces was significantly associated with regional economic development. CE of green spaces in the HICs, represented by the HIC-A, HIC-C, and HIC-D, was predominantly influenced by BD (Fig. 2). Conversely, in the LICs, the impact of BH dominated in most intervals of CE, in which the LIC-B showed such trend particularly clearly. However, it remains challenging to identify the thresholds of built-up environments that can be applied to either promote high CE or mitigate low CE of green spaces. Especially when BD and BH are at extreme values, even if the green spaces may exhibit higher or lower CE, the estimates were not strongly confident (Supplementary Fig. S5).

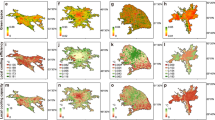

To clarify the potential thresholds of BD and BH that affect the CE of green spaces, we extracted the peak intervals (above 90th percentiles of CE) and valley intervals (below 10th percentiles of CE) for each zone (Fig. 3). Firstly, we examined the combined thresholds of built-up environments associated with high CE of green spaces. It could still be observed that in the HICs, high CE of green spaces occurred predominantly at low BD values (with the peak interval extending along the BH axis). This implied that in the HICs, building height over a broader range could always secure higher cooling effects in improving the proportions of green spaces when the built-up density is fixed. Specifically, when the average BD was maintained below 20%, higher CE of green spaces was achieved by permitting a more flexible BH (especially with the average BH thresholds being approximately 4–18 m and 0–20 m for the HIC-A and HIC-B zones, respectively). In contrast, in the LICs, high CE occurred predominantly at specific BH ranges (with the peak interval extending along the BD axis). In the LICs, except in cold areas, achieving better CE of green spaces tended to require controlling the average BH to be below 6 m.

The peak interval is the 90–100% quartile of CE of green spaces, and the valley interval is the 0–10% quartile of CE of green spaces. HIC, UMIC, LMIC, and LIC are indicated as countries in high income, upper-middle income, lower-middle income, and low income, respectively. A, B, C, and D are represented as the tropical, arid, temperate, and cold climates, respectively. In order to characterize the distribution of the intervals more prominently, the intervals are divided into four categories by 95–100%, 90–95%, 0–5%, and 5–10%.

The valley interval of CE of green spaces exhibited an opposite trend to that of the peak interval within the same regions. In the built-up areas in the HICs, low CE of green spaces is mainly associated with average BD concentrated between 20 and 40%. In most zones of the UMICs (especially in arid and temperate climates), a typical phenomenon was that higher average BH led to the deterioration of the cooling efficiency of green spaces. In the LMICs, the combined thresholds of built-up environments associated with low CE of green spaces are scattered. In zones such as the LIC-A and LIC-C, urban layouts featuring moderate BH coupled with moderate or low BD (an average BD of less than approximately 50%) may be unfavorable for green spaces to deliver a more effective cooling effect.

Potential mechanism for the effects of built-up environment on the CE of green spaces

We further analyzed how BD and BH contribute to achieving high CE of green spaces through processes-related variables involving soil moisture (SOI), wind speed (WS), near-surface air temperature (TA), and surface albedo (ALB) (Table 1). Given that the differences in green space cooling associated with economic development were more pronounced in temperate regions (Fig. 1), we focused on built-up areas with extremely high CE (i.e., the peak intervals shown in Fig. 3) under a temperate climate. WS emerged as the key variable regulating high CE of green spaces, with its influence being significant across all four income groups (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S6). In economically advanced the HICs and UMICs, the reduction in WS promotes high CE of green spaces, but the roles of BD and BH diverge. In the HICs, increasing BH enhances the CE of green spaces, whereas in the UMICs, reducing BD is the primary mechanism by which WS regulates the CE of green spaces. Furthermore, both the HICs and UMICs show significant contributions from TA—that is, an increase in regional TA can enhance the CE of green spaces. Notably, in the HICs, the driving mechanisms of BD and BH are consistent, where reducing BD and increasing BH invariably lead to improved CE under the influence of WS and TA.

In contrast to economically developed regions, the impact path of WS in the LICs is reversed, where an increase in regional WS can promote high CE of green spaces. Two different impact mechanisms of WS depend on the strengths of sensible heat exchange versus latent heat exchange of vegetation26. Moreover, the regulation mechanism of TA in the LICs and LMICs is not significant. Unlike the synergistic driving mechanisms of BD and BH observed in the HICs, in the LICs and LMICs, there is a distinct trade-off between the effects of BD and BH on the high CE of green spaces. When BD is reduced and BH is increased, the resulting changes in regional WS weakens the CE of green spaces, while the associated reduction in regional ALB enhances the CE of green spaces. Therefore, in cities with lower income, the potential mechanisms by which the built-up environment regulates green space cooling are considerably more complex.

Discussion and conclusions

The CE of green spaces related to socio-economic development

Enhancing CE of green spaces is vital for combating the escalating urban heat island effect which exacerbates energy demand and heat-related mortality. Higher coverage of green spaces improves thermal comfort in public spaces, promoting outdoor activities and social cohesion. Furthermore, effective cooling approaches mitigate heat stress on vulnerable populations, reducing health risks during extreme heat events. Optimizing CE of green spaces thus represents a nature-based solution for sustainable urban climate adaptation.

In this study, we modeled the CE of green spaces in 1113 built-up areas worldwide and compared them in different income groups. Overall, the average CE of green spaces in the HICs was 1.64 times that in the LICs (Fig. 1). Especially in a temperate climate, the ratio of average CE of green spaces between the HICs and LICs reached 1.78, indicating that built-up areas with better socio-economic development have more substantial cooling effects of green spaces. It was also found that higher CE in green spaces tended to be shown in the larger built-up areas. Urban agglomerations consisting of several adjacent built-up areas generally had a higher CE of green spaces.

In large cities or urban agglomerations, high-intensity human activities lead to a significant heat island effect and higher ambient temperatures in built-up areas27,28,29. The cooling process of green spaces relies on the transpiration of vegetation, and higher ambient temperatures increase the vapor pressure deficit between vegetation and the atmosphere, thereby increasing the transpiration capacity30,31. The increased temperature differences also enhance sensible heat exchange32,33. The above processes potentially result in higher CE of green spaces in highly developed cities or urban agglomerations. In addition, relatively mature development enables urban areas to secure greater investment and adopt advanced management for green infrastructure. High-income and upper-middle-income countries typically do not pursue unlimited expansion of construction land or industrial production; instead, they balance the proportions of various landscapes to fully leverage the ecosystem services of green spaces in mitigating adverse climate effects34,35. Moreover, high-income and upper-middle-income countries possess more comprehensive urban planning systems—particularly in terms of ecosystem planning—which play a pivotal role in optimizing urban spatial configurations30,36. These insights further underscore the importance of investigating how built-up environments in regions with varying socio-economic development levels influence the cooling effect of green spaces.

Improve the built-up patterns to regulate the CE of green spaces

We employed BD and BH to characterize built-up features, revealing disparities in factors influencing the CE of green spaces between low-income and high-income countries. To identify the threshold combinations of BD and BH that modulate the CE of green spaces, we extracted the peak and valley intervals across various economic regions. Generally, the HICs are predominantly influenced by BD, whereas the LICs are mainly affected by BH. Notably, in the most zones of HICs, maintaining urban average BD below 20% allowed for a broader range of BH to achieve a relatively high CE of green spaces. Conversely, in the LIC-A and LIC-C zones, urban layouts featuring moderate BH coupled with moderate or low BD may impede the effectiveness of green spaces’ cooling functions.

The built-up environment critically influences the CE of green spaces through multidimensional interactions. Urban morphology directly alters microclimatic conditions. The density influences landscape patterns and heat storage capacity, and the height also modifies shadow distribution and heat exchange. Through the processes that urban built-up environment affects LST, socio-economic factors shape urban forms differently across development levels. High-income countries often optimize ratios of BD and BH for better thermal regulation, whereas low-income areas face constraints in balancing high-quality development. Importantly, these effects show strong climate-context dependency, where similar built-up environment configurations may produce opposite CE outcomes in different climate backgrounds due to differences of feedback of green spaces on urban thermal environment.

We analyzed several regulatory variables to deepen our understanding of how BD and BH influence the CE of green spaces. In the HICs, reducing WS and increasing near-surface TA could enhance the CE of green spaces. BH primarily governed the impact of WS. WS influences air circulation and heat exchange, whereas BH alters urban surface roughness and creates canyon effects37. In the LICs, a decrease in regional average WS led to a reduction in CE of green spaces, contrasting with the patterns observed in the HICs. This discrepancy arises because WS affects both latent and sensible heat exchanges in vegetation cooling. Generally, the positive effect of WS in the HICs is due to increased WS enhancing convection between vegetation and the ambient air, thereby strengthening the capacity of green spaces to dissipate heat38,39,40. Therefore, we recommend enhancing the CE of green spaces in the HICs by increasing BH and reducing BD. Urban planning should consider differentiated BD and BH strategies based on various climate types, guided by the combined thresholds.

In urban renewal and expansion, it is crucial to be vigilant about the potential diminishing effects of overdevelopment on the CE of green spaces. By judiciously controlling BD and BH, the effective CE of green spaces can be maintained. Optimizing urban spatial structures by increasing the proportion of green spaces is a pivotal strategy to improve urban thermal comfort41. Moreover, implementing technologies such as green roofs and vertical greening can effectively mitigate the heat storage and heat dissipation of building surfaces42. Additionally, the ecological design of green spaces warrants deeper attention. Selecting plant species adapted to local climates and enhancing vegetation stratification can further amplify the cooling effects of green spaces43. The heterogeneity of economic conditions underscores the necessity for context-specific urban planning strategies. It is significant to find a balance between green space planning and built-up area management, promoting systemic improvements in urban thermal environment.

Limitations and further research

This study has several issues that need to be explored in the future. Although it covers 1113 built-up areas worldwide, the sample size is relatively small in specific geographic regions, which is partly influenced by the quality of the source data. Future research could integrate multi-source remote sensing, in-situ observations, and administrative statistical data to expand the urban samples and refine the classification of economic development levels. Additionally, while CE is a useful metric, it focuses solely on the reduction of LST in this study, neglecting other features of thermal comfort. In the future, wet-bulb temperature or universal thermal comfort index could be introduced to demonstrate more comprehensive cooling effect of green spaces. Besides, it may oversimplify spatial variability by averaging effects across heterogeneous urban landscapes, and short-term CE assessments may not reflect long-term vegetation growth impacts.

Methods

Extracting and classifying built-up areas

We applied the GHS Urban Centre Database (GHS-UCDB R2019A)44,45 to delineate the boundaries of built-up areas globally. To ensure the reliability of the analytical sample size, we selected urban built-up areas with a surface area greater than 30 km246. It is noted that some of extracted areas, due to urbanization, may encompass multiple administrative cities, reflecting the complexity of interactions between spatial scales and the built-up environment.

The urban built-up environment was characterized using two key indicators: BD and BH. BD and BH were derived from the GHS built-up surface grid (R2023) and the GHS built-up height (R2023) datasets, respectively, both with a spatial resolution of 100 m and a temporal reference of 2018. BD refers to the built-up density (i.e., the proportion of built-up surface) and BH is the building height (i.e., the ratio of volume to area)44,47.

To compare differences in built-up areas with varying levels of economic development, we adopted the income-based country classification of World Bank, categorizing all built-up areas into four groups: HIC, UMIC, LMIC, and LIC. Considering the sensitivity of cooling effect of green spaces to climate conditions, built-up areas were further classified according to the Köppen-Geiger climate classification48 into tropical (A), arid (B), temperate (C), and cold (D) zones. Among these categories, built-up areas in the lower-middle-income countries under the temperate climate (LMIC-C) and the high-income countries under the temperate climate (HIC-C) had the largest sample sizes.

Assessing the CE of green spaces

We calculated the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and LST for the study areas based on Landsat 8 remote sensing imagery. NDVI is widely used to assess greenness and identify the spatial extents of green spaces49,50. Selected images had a cloud cover of less than 5%. To avoid potential biases caused by climate anomalies associated with El Niño and the reduction in urban human activities during the COVID-19 pandemic26. The study period was restricted to the hottest summer months from 2017 to 2019 on clear-sky days. Each built-up area contained more than 10,000 effective image elements. Then the NDVI was converted into fractional vegetation cover (FVC). The least-squares linear regression model was further applied to fit the relationship between FVC and LST within the urban built-up areas15. Finally, the negative values of the regression coefficients were defined as the CE of green spaces51. The CE of green spaces quantifies the LST reduction capacity per unit increase in the coverage of green spaces. Eventually, 1113 independent built-up areas were included in the analysis.

Analysis on the nonlinear impact of the built-up environment

As this study aimed to analyze the impact of the built-up environment on the CE of green spaces, we stratified vegetation coverage to minimize the interference of vegetation characteristics in the fitting. Each urban built-up area was divided into 40 intervals based on vegetation coverage (ranging from 0 to 100% in 2.5% increments). For each stratification, we calculated the CE of green spaces, the average BD, and the average BH. Additionally, only spatial units containing buildings and green spaces were retained to quantify the relationship between built-up characteristics and green space cooling.

The GAM was applied to capture the nonlinear relationships between BD, BH, and the CE of green spaces. GAM combines the advantages of generalized linear models and non-parametric regression26. By allowing each variable’s effect to be represented in a nonlinear manner, GAM provides greater modeling flexibility, which can significantly improve model fitting for complex data. Moreover, the additive structure of GAM enables the separation of the independent effects of each variable while also incorporating interaction effects, ensuring both the scientific validity and interpretability of the model results.

We further identified the combined thresholds of BD and BH for the extreme CE of green spaces to determine how spatial configurations of urban built-up areas should be optimized to maximize cooling efficiency in different income groups. GAM-fitted ranges, which hold 90–100% percentile and 0–10% percentile of CE, were selected as the peak and valley intervals, respectively. It is noted that to avoid result uncertainty caused by excessive smoothing, we excluded CE ranges where BD and BH were in the extremely high (≥95%) and extremely low (≤5%) values.

Analysis on the potential mechanism of the built-up environment impact

Built-up density and building height, as two- and three-dimensional expressions of the urban spaces52, significantly correlate with the cooling effects of green spaces through several biophysical processes. For example, high-density buildings can affect the urban albedo, altering the local thermal environment53,54. Building height can change the urban wind environment, which in turn affects the cooling effect of vegetation19,38. In addition, building height alters the shaded areas of structures, which affects the energy exchange within green spaces55. Therefore, this study analyzed the complex relationships between BD, BH, and cooling-related mediators. Mediators (i.e., SOI, WS, TA, and ALB) were selected based on empirical evidence of their control on surface energy balance in vegetated areas. For human activity variables, we have analyzed the correlation between common indicators (nighttime light intensity and population density) and the built-up environment, and found highly positive correlations (Supplementary Table S2). Therefore, we emphasized the importance of human activity characteristics in explaining the formation of the built-up environment, rather than directly connecting the cooling process of green spaces as the mediators in this study.

We applied the structural equation model (SEM) to reveal the pathways about how BD and BH influence the CE of green spaces regulated by mediating variables. SEM is a statistical approach used to describe and estimate causal relationships among multiple variables56. It effectively handles latent variables and multicollinearity issues, allowing for the quantification of path coefficients to clarify both direct and indirect effects. SEM enables the quantification of both direct and indirect effects of the built-up environment on the CE of green spaces through different pathways.

The ALB was obtained from the MODIS daily land surface albedo dataset (MCD43A4) with a spatial resolution of 500 m. The near-surface TA was sourced from NOAA’s “global-summary-of-the-day” dataset, which has a spatial resolution of 1 km. WS and SOI were obtained from TerraClimate57, which provides monthly-resolution datasets with a spatial resolution of about 4 km. The WS and SOI data were resampled to a 500 m resolution. Finally, we calculated the average ALB, TA, WS, and SOI for the built-up areas within each stratification.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All datasets are publicly available. Landsat 8 data are available at https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/. GHS Urban Centre Database (GHS-UCDB R2019A) and GHS built-up surface grid (R2023), GHS built-up height (R2023) are available at https://human-settlement.emergency.copernicus.eu/index.php. MCD43A4 can be downloaded from https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mcd43a4v061/. The NOAA’s “global-summary-of-the-day” dataset are from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/data/global-summary-of-the-day/. TerraClimate data are available at https://www.climatologylab.org/terraclimate.html.

References

Huang, K. et al. Persistent increases in nighttime heat stress from urban expansion despite heat island mitigation. JGR Atmos. 126, e2020JD033831 (2021).

Santamouris, M., Cartalis, C., Synnefa, A. & Kolokotsa, D. On the impact of urban heat island and global warming on the power demand and electricity consumption of buildings—A review. Energy Build. 98, 119–124 (2015).

Dong, J. et al. Trends of the intra-annual onset and end of humid heatwaves in the northern hemisphere. Earth’s. Future 12, e2024EF005163 (2024).

Dong, J., Hu, T., Liu, Y. & Peng, J. Urban-rural differences in the local human exposure to humid heatwaves in the Northern Hemisphere. Sustain. Cities Soc. 107, 105415 (2024).

Cousins, J. J. Just nature-based solutions and the pursuit of climate resilient urban development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 247, 105054 (2024).

Hayes, A. et al. Nature-Based Solutions (NBSs) to Mitigate Urban Heat Island (UHI) Effects in Canadian Cities. Buildings 12, 925 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Regulation of humid heat by urban green space across a climate wetness gradient. Nat. Cities 1, 9 (2024).

Gunawardena, K. R., Wells, M. J. & Kershaw, T. Utilising green and bluespace to mitigate urban heat island intensity. Sci. Total Environ. 584–585, 1040–1055 (2017).

Suárez, M. et al. Urban resilience through green infrastructure: a framework for policy analysis applied to Madrid, Spain. Landsc. Urban Plan. 241, 104923 (2024).

Taylor, L. & Hochuli, D. F. Defining greenspace: multiple uses across multiple disciplines. Landsc. Urban Plan. 158, 25–38 (2017).

Aram, F., García, E. H., Solgi, E. & Mansournia, S. Urban green space cooling effect in cities. Heliyon 5, e01339 (2019).

Rahman, M. A. et al. More than a canopy cover metric: influence of canopy quality, water-use strategies and site climate on urban forest cooling potential. Landsc. Urban Plan. 248, 105089 (2024).

Paschalis, A., Chakraborty, T., Fatichi, S., Meili, N. & Manoli, G. Urban forests as main regulator of the evaporative cooling effect in cities. AGU Adv. 2, e2020AV000303 (2021).

Yu, Z. et al. Quantifying seasonal and diurnal contributions of urban landscapes to heat energy dynamics. Appl. Energy 264, 114724 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Significant effects of ecological context on urban trees’ cooling efficiency. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 159, 78–89 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Green spaces provide substantial but unequal urban cooling globally. Nat. Commun. 15, 7108 (2024).

Gao, Z., Zaitchik, B. F., Hou, Y. & Chen, W. Toward park design optimization to mitigate the urban heat Island: Assessment of the cooling effect in five U.S. cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 81, 103870 (2022).

Shah, A., Garg, A. & Mishra, V. Quantifying the local cooling effects of urban green spaces: evidence from Bengaluru, India. Landsc. Urban Plan. 209, 104043 (2021).

Huang, Q. et al. Heterogeneous effects of the availability and spatial configuration of urban green spaces on their cooling effects in China. Environ. Int. 183, 108385 (2024).

Cheng, X., Liu, Y., Dong, J., Corcoran, J. & Peng, J. Opposite climate impacts on urban green spaces’ cooling efficiency around their coverage change thresholds in major African cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 88, 104254 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Efficient cooling of cities at global scale using urban green space to mitigate urban heat island effects in different climatic regions. Urban For. Urban Green. 74, 127635 (2022).

Wu, W., Guo, F., Elze, S., Knopp, J. & Banzhaf, E. Deciphering the effects of 2D/3D urban morphology on diurnal cooling efficiency of urban green space. Build. Environ. 266, 112047 (2024).

Perini, K. & Magliocco, A. Effects of vegetation, urban density, building height, and atmospheric conditions on local temperatures and thermal comfort. Urban For. Urban Green. 13, 495–506 (2014).

Guo, G., Zhou, X., Wu, Z., Xiao, R. & Chen, Y. Characterizing the impact of urban morphology heterogeneity on land surface temperature in Guangzhou, China. Environ. Model. Softw. 84, 427–439 (2016).

Yuan, B. et al. Separate and combined effects of 3D building features and urban green space on land surface temperature. J. Environ. Manag. 295, 113116 (2021).

Cheng, X., Peng, J., Dong, J., Liu, Y. & Wang, Y. Non-linear effects of meteorological variables on cooling efficiency of African urban trees. Environ. Int. 169, 107489 (2022).

Jamei, Y., Rajagopalan, P. & Sun, Q. C. Spatial structure of surface urban heat island and its relationship with vegetation and built-up areas in Melbourne, Australia. Sci. Total Environ. 659, 1335–1351 (2019).

Meng, Q. et al. Characterizing spatial and temporal trends of surface urban heat island effect in an urban main built-up area: a 12-year case study in Beijing, China. Remote Sens. Environ. 204, 826–837 (2018).

Zhou, X. & Chen, H. Impact of urbanization-related land use land cover changes and urban morphology changes on the urban heat island phenomenon. Sci. Total Environ. 635, 1467–1476 (2018).

Piao, S. et al. Characteristics, drivers and feedbacks of global greening. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 14–27 (2020).

Hu, L. & Li, Q. Greenspace, bluespace, and their interactive influence on urban thermal environments. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 034041 (2020).

Skelhorn, C., Lindley, S. & Levermore, G. The impact of vegetation types on air and surface temperatures in a temperate city: a fine scale assessment in Manchester, UK. Landsc. Urban Plan. 121, 129–140 (2014).

Yang, J. et al. Characterizing the thermal effects of vegetation on urban surface temperature. Urban Clim. 44, 101204 (2022).

Amini Parsa, V., Salehi, E., Yavari, A. R. & Van Bodegom, P. M. Evaluating the potential contribution of urban ecosystem service to climate change mitigation. Urban Ecosyst. 22, 989–1006 (2019).

Massaro, E. et al. Spatially-optimized urban greening for reduction of population exposure to land surface temperature extremes. Nat. Commun. 14, 2903 (2023).

Cheung, P. K., Nice, K. A. & Livesley, S. J. Irrigating urban green space for cooling benefits: the mechanisms and management considerations. Environ. Res. Clim. 1, 015001 (2022).

Lu, J. et al. A micro-climatic study on cooling effect of an urban park in a hot and humid climate. Sustain. Cities Soc. 32, 513–522 (2017).

Qiao, Z. et al. Urbanization accelerates urban warming by changing wind speed: Evidence from China based on 2421 meteorological stations from 1978 to 2017. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 102, 107189 (2023).

Ngarambe, J., Oh, J. W., Su, M. A., Santamouris, M. & Yun, G. Y. Influences of wind speed, sky conditions, land use and land cover characteristics on the magnitude of the urban heat island in Seoul: An exploratory analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 71, 102953 (2021).

Yang, S., Wang, L. L., Stathopoulos, T. & Marey, A. M. Urban microclimate and its impact on built environment–a review. Build. Environ. 238, 110334 (2023).

Liao, W. et al. Linking urban park cool island effects to the landscape patterns inside and outside the park: a simultaneous equation modeling approach. Landsc. Urban Plan. 232, 104681 (2023).

Li, Y., Ren, C., Ho, J. Y. & Shi, Y. Landscape metrics in assessing how the configuration of urban green spaces affects their cooling effect: a systematic review of empirical studies. Landsc. Urban Plan. 239, 104842 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. How small green spaces cool urban neighbourhoods: Optimising distribution, size and shape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 253, 105224 (2025).

Pesaresi, M. & Politis, P. GHS-BUILT-S R2023A - GHS built-up surface grid, derived from Sentinel2 composite and Landsat, multitemporal 1975-2030. https://doi.org/10.2905/9F06F36F-4B11-47EC-ABB0-4F8B7B1D72EA (2023).

The Multi-temporal and Multi-dimensional Global Urban Centre Database to Delineate and Analyse World Cities | Scientific Data. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-023-02691-1.

Zhou, B., Rybski, D. & Kropp, J. P. The role of city size and urban form in the surface urban heat island. Sci. Rep. 7, 4791 (2017).

Full article: Advances on the Global Human Settlement Layer by joint assessment of Earth Observation and population survey data. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17538947.2024.2390454.

Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution | Scientific Data. https://www.nature.com/articles/sdata2018214.

Rotem-Mindali, O., Michael, Y., Helman, D. & Lensky, I. M. The role of local land-use on the urban heat island effect of Tel Aviv as assessed from satellite remote sensing. Appl. Geogr. 56, 145–153 (2015).

Wang, A., Dai, Y., Zhang, M. & Chen, E. Exploring the cooling intensity of green cover on urban heat island: a case study of nine main urban districts in Chongqing. Sustain. Cities Soc. 124, 106299 (2025).

Wang, J., Zhou, W., Pickett, S. T. A. & Qian, Y. A scaling law for predicting urban trees canopy cooling efficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2401210121 (2024).

Li, Y., Schubert, S., Kropp, J. P. & Rybski, D. On the influence of density and morphology on the Urban Heat Island intensity. Nat. Commun. 11, 2647 (2020).

Alexander, C. Influence of the proportion, height and proximity of vegetation and buildings on urban land surface temperature. Int. J. Appl. Earth Observ. Geoinf. 95, 102265 (2021).

Yang, X. & Li, Y. The impact of building density and building height heterogeneity on average urban albedo and street surface temperature. Build. Environ. 90, 146–156 (2015).

Sun, T., Chen, L. & Sun, R. Cooling effects in urban communities: parsing green spaces and building shadows. Urban For. Urban Green. 94, 128264 (2024).

Aalto, J., Scherrer, D., Lenoir, J., Guisan, A. & Luoto, M. Biogeophysical controls on soil-atmosphere thermal differences: implications on warming Arctic ecosystems. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 074003 (2018).

TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015 | Scientific Data. https://www.nature.com/articles/sdata2017191.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42401108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.C. contributed to conceptualization, data curation, methodology, visualization and draft writing. J.Y., Y.L., and T.H. contributed to validation, draft review and editing. J.D. secured funding and was responsible for designing the research, draft writing, review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Pui Kwan Cheung and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Nandita Basu. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Ye, J., Liu, Y. et al. Global assessment in the effect of urban built-up environment on cooling efficiency of green spaces. Commun Earth Environ 6, 968 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02925-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02925-7