Abstract

In the Arctic, substantial amounts of methane are stored in marine sediments. Yet, the distribution and stability of methane reservoirs is poorly understood, especially offshore Greenland. As Arctic warming accelerates, understanding natural methane seepage is crucial for assessing its role in the carbon cycle and climate impact. Here, we present a unique interdisciplinary geoscientific data set that spans the ice-covered Northeast Greenland shelf and captures entire fluid flow systems from source to sink. Our data documents widespread natural seepage of oil and gas from the seafloor through the water column, locally reaching the sea surface. The released hydrocarbons are sourced from deep petroleum systems and primarily migrate along permeable beds towards the seafloor. Glacial erosion during the Quaternary has effectively removed the sealing units, creating geologic windows that allow widespread natural seepage. Our first-order estimates suggest that minimum 677–1460 Mt of thermogenic gas ( ~ 0.5–1.1 Gt of carbon) has been released into the ocean since grounded ice retreated from the shelf around ~15 ka BP. These findings provide new insight into the impact of active natural seepage in a rapidly changing climate and have substantial implications for the Arctic Ocean’s carbon cycle and marine ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Methane is the second most abundant greenhouse gas in our atmosphere and has a 28-times higher warming potential than carbon dioxide on a 100-year time horizon1,2. Atmospheric concentrations of methane are currently increasing at a scale and rate (up to 18 parts per billion/yr) comparable to past glacial terminations3. In the Arctic, substantial amounts of methane are likely stored as free gas, dissolved in pore waters, or frozen as gas hydrates in marine sediments and shallow sedimentary bedrock4,5,6. However, fundamental knowledge on the distribution and stability of methane reservoirs in the Arctic is missing, especially around Greenland. This results in a poorly constrained methane budget with only three data points (Svalbard, Alaska-Canada Beaufort Sea, Russia East Siberian Arctic Shelf) for the entire Arctic Ocean7,8.

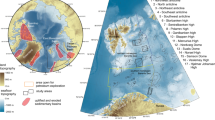

The Northeast (NE) Greenland shelf spans 350 km in width and over 800 km in length (Fig. 1) and holds an exceptionally high hydrocarbon potential (estimated as 6675 million barrels of oil equivalent9), and is conjugate to the hydrocarbon-rich Norwegian continental shelf10. Data acquisition in the extreme conditions of the NE Greenland shelf has been largely driven by the hydrocarbon industry. Sea ice prevents water-atmosphere exchange for nine months of the year, icebergs form a major hazard for marine infrastructure, polar nights blanket the area in darkness, and no cities or settlements exist for logistical support. Reduced oil prices, costly exploration and environmental considerations halted industry efforts and have now allowed academia access to unique data sets for frontier research on the shelf11. On the conjugate hydrocarbon-rich Norwegian margin similar data sets continuously reveal new natural seepage sites on the seafloor12, many related to oil and gas release from uplifted sedimentary basins where extensive erosion from Quaternary glaciations has effectively removed cap rocks6,13. Provided an active petroleum system is driving the generation and migration of hydrocarbons on the NE Greenland shelf, a similar widespread natural seepage of hydrocarbons (including methane) across the entire shelf is highly likely6,14. However, whether this is in fact the case is hitherto unknown as the NE Greenland shelf remains uncharted for methane reservoirs and fluid flow, creating a critical knowledge gap that may lead to substantial miscalculations in the Arctic carbon budget1.

A Bathymetric map with all presented data (all available data shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). Bathymetry from Version 5.0 of the International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean (IBCAO) Grid105. Red lines highlight seismic profiles shown in Figs. 4 and 5, sediment cores are shown as black crosses (biomarker data shown in Supplementary Fig. 2) and multibeam echosounder (MBES) coverage is indicated in orange. Inter-trough areas (IT) are labelled IT-A. IT-B, IT-C after19. SKT Store Koldewey Trough, DBT Dove Bugt Trough, EGS East Greenland Survey by TGS & VBER. B Tectonic structure of the NE Greenland margin. The structural map is modified from15. Main structural elements such as Danmarkshavn Basin, Danmarkshavn Ridge, and Thetis Basin, as well as the Wandel Sea Basin are indicated. Label abbreviations are given in the legend. Yellow lines indicate the approximate location of the lithostratigraphic profiles across the NE Greenland Shelf shown in Fig. 2 and the red lines highlight seismic profiles shown in Figs. 4 and 5.

In this study, we use ~120,000 km of industry multichannel seismic reflection and 164 sediment cores together with newly acquired scientific ~1050 km² multibeam echosounder data and deep-learning based investigations of remote sensing data to investigate and document natural seepage of fluids (hydrocarbons such as oil and methane gas) from the seafloor of the NE Greenland shelf (Supplementary Fig. 1). Our data demonstrate the migration of fluids from deep subsurface reservoirs, their release at the seafloor and transmission through the water column. We further observe sea surface oil slicks in the temporarily ice-free region, consistent with ongoing hydrocarbon seepage ongoing at the seafloor. This dataset allows us to determine the processes of fluid migration and estimate the amount of methane released from this Arctic shelf region.

Regional Setting

The NE Greenland margin is bounded by the continent-ocean transition zone to the east and north, a sedimentary pinch out against crystalline basement to the west, and Paleocene-Eocene basalts to the south10,15 (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Fig. 1). It contains five major structural elements: (1) the Koldewey Platform, a 30–70 km wide structural high stretching from the island of Store Koldewey and northwards to at least 80°N; (2) the Danmarkshavn Basin, an at least 400 km long and several kilometer deep Paleozoic–Mesozoic sedimentary basin; (3) the Danmarkshavn Ridge, an up to 60 km–wide series of westerly dipping tilted fault blocks, which form a platform area that separates the Danmarkshavn Basin from the (4) Thetis Basin, a 200 km long and 60 km wide sedimentary basin with thick Cretaceous and Cenozoic sequences; and (5) the Wandel Sea Basin, a transtensional sedimentary basin forming the northeasternmost Greenland margin between ca. 79°N and 81°N (see Fig. 1B). Below the remnants of Pleistocene sediments, the shelf shows tilted subcropping strata and a transition from sediments of Late Jurassic age on the inner shelf to Quaternary age on the outer shelf (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 1). Similar to the conjugate Norwegian Margin, probable source rocks are found in the Upper Paleozoic and Mesozoic and include the oil-prone Oxfordian–Ryazanian interval as well as the Devonian–Carboniferous lacustrine mudstones and coals, Upper Permian carbonaceous marls/shales, Middle Triassic basinal shales, Upper Triassic–Lower Jurassic lacustrine mudstones, Lower–Middle Jurassic restricted marine shales, Middle Jurassic humic coals, and possibly intra-Cretaceous organic shales16. The Upper Jurassic to Lowermost Cretaceous source rocks (Fig. 2) have the highest potential for oil and gas in the eastern Danmarkshavn Basin, the western (outer) Thetis Basin, and along the edges of the Danmarkshavn Ridge15. Potential reservoirs are sandstones along the margin (Fig. 2), which include shallow-marine/fluvial sandstones of the Triassic, shallow-marine/fluvial sandstones in the Lower and Middle Jurassic, coarse-grained gravity-flow deposits in the uppermost Jurassic–lowermost Cretaceous, shallow-marine and local turbidite sandstones within the Cretaceous, shallow-marine and turbidite sandstones latest Cretaceous–lower Paleocene in the Danmarkshavn and the Thetis basins, as well as synrift gravity-flow sandstones in the Paleogene in the Wandel Sea Basin15.

A West to East transect from the Koldewey Platform to the outer marginal highs. B South to North transect from the Koldewey Platform to the Wandel Sea Basin. Lithostratigraphy modified from15. SKP= Southern Koldewey Platform, DR Danmarkshavn Ridge, R Reservoir, S Source, T Trap, DB Danmarkshavn Basin, WSB Wandel Sea Basin. For location of the transects see Fig. 1.

On the NE Greenland Shelf, the Danmarkshavn Basin has by far the highest hydrocarbon potential9. It is flanked by structural highs developed as footwall blocks during Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous rifting15 (Fig. 2). Cretaceous strata are intruded by Late Paleocene-Early Eocene magmatic complexes17 related to continental break-up. Neogene glaciation and uplift of the onshore areas have tilted the basin and eroded most of the post-Paleocene deposits (Fig. 2). On the northern part of the Danmarkshavn Basin (co-located with IT-A), abundant salt diapirs are close to or reach the seafloor and deform the otherwise very regular sedimentary strata (Fig. 1). Diapirism of Carboniferous-Permian salt is evident across the entire Danmarkshavn Basin but more pronounced towards the north. This diapirism peaked during the Cretaceous and early Cenozoic due to extensive sediment loading, and seems mostly inactive at present10,15. In the north and towards the Wandel Sea Basin, the Cenozoic was dominated by right-lateral transtensional deformation, which drove stepwise continental separation during the Eocene to Miocene, culminating in the current configuration of the margin18.

The continental shelf stretches 75°–81°N and extends up to 350 km east of the coastline (see Fig. 1A). It is characterized by three over-deepened troughs that terminate at the shelf edge: Westwind Trough, Norske-Belgica Trough, and Store Koldewey Trough. These troughs are separated by intermediate shallow banks (IT-A, B, C)19. Westwind Trough and Norske-Belgica Trough are 300–430 km long, 40–200 km wide, and 200–500 m deep. They merge on the innermost shelf near the outlets of the contemporary NE Greenland Ice Stream, forming a horseshoe-shaped trough encircling the large inter-trough area IT-A (Fig. 1). The seafloor of IT-A is hummocky, comprising a complex of shallow banks and smaller depressions (water depths 2–400 m). This has been attributed to salt tectonics causing folding and doming of overlying strata and locally salt diapirs sub-crop the seafloor19,20,21. Store Koldewey Trough is 250–400 m deep, 200 km long and 30–50 km wide, bounded to the by the shallow IT-B bank (150–250 m deep) and to the south by IT-C bank (50–150 m deep).

Due to its bathymetric configuration19, the NE Greenland continental shelf hosts a distinct hydrographic structure shaped by the interplay of two principal water masses22,23: a surface layer of cold (−1.7–0 °C), low-salinity (30–34 PSU) Polar Water (PW) transported southward by the East Greenland Current (EGC), underlain by relatively warm (1–3 °C) and saline (34.8–35 PSU) Atlantic-derived waters that enter via Fram Strait and are funneled onto the shelf through deep troughs24. In recent decades, the system has experienced pronounced “Atlantification”, marked by warming and shoaling of Atlantic water layers alongside thinning and freshening of PW, fundamentally altering vertical stratification and enhancing heat fluxes onto the shelf22,25.

Results and discussion

Seismic mapping of fluid flow indicators

The regional 2D seismic grid covers large parts of the NE Greenland shelf, albeit with sparser data coverage in the northern part (Supplementary Fig. 1). The complete data set has been acquired over a long time period (1991–2016) and especially surveys on the inner and northern shelf are of lower quality and resolution, hindering the interpretation of fluid flow in marine sediments (Supplementary Fig. 1, Table 1). Seismic data are highly sensitive to fluids such as gas or oil in pore space26. We use the available seismic data to map seismic fluid indicators across the shelf and thereby visualize fluid migration pathways27.

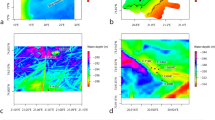

Our mapping includes three categories of seismic anomalies (Fig. 3). Type I anomalies are shallow (<75 mbsf) with high amplitudes and occasionally of reversed polarity compared to the seafloor reflection. Polarity reversals usually indicate the existence of free gas in pore space26,28. Type I anomalies typically occur at or close to the seafloor but can also be observed beneath the thin veneer of glacial (Miocene to Pleistocene) sediments that overlie the subcropping older strata (Fig. 3A; Fig. 4B, C; Fig. 5A, B). Especially where the subcropping geology pinches out, Type I anomalies are observed as an increase in amplitude towards the seafloor (Fig. 5B, D, E; Supplementary Fig. 1).

A Examples of Type I (shallow high-amplitude, blue dots), Type II (deep high-amplitude, red dots) and Type III (sub-horizontal high-amplitude, yellow dots) seismic anomalies. The data shows offset in meter on x-axis and two-way travel time in seconds on y-axis. BSR Bottom-Simulating Reflector (B) Mapped anomalies with respect to the seafloor morphology and (C) draped conventional hydrocarbon reservoirs from the Greenland Resource Assessment (blue= lead reservoirs, orange = concept reservoirs)9. Inter-trough areas (IT) are labelled IT-A. IT-B, IT-C after19. SKT Store Koldewey Trough, SKI=Store Koldewey Island.

A Vertical seismic display shows offset in meters on the x-axis and two-way travel time in seconds on the y-axis. Red arrows indicate flow direction of fluids. Observed flares are shown as a green star and sediment cores as black crosses. The location of zoom-ins (B–D) are indicated by white boxes. The location of the seismic line is shown in (E). B–D Insets show Type I and Type II anomalies associated with permeable beds (B), deep-rooted faults (C) and stratigraphic traps, here below Eocene sediments (D). E Bathymetric map showing the location of the seismic profile (E, red line), the multibeam echosounder data, and mapped flares (green stars). The upper limit of gas hydrate stability for Polar water is shown as blue dashed line. Seismic data is shown as white lines with Type I anomalies as blue dots and Type II anomalies as red dots. Sediment cores are indicated with black crosses. Seismic data courtesy of TGS.

A Seismic profile crossing the basin with red arrows showing the direction of fluid migration. Profile shows offset in meters on the x-axis and two-way travel time in seconds on the y-axis. S=magmatic sill intrusions. Details on (B) outcropping tilted beds with Type I and Type II seismic anomalies and (C) faults in the outer Danmarkshavn Basin associated with Type II and Type III seismic anomalies. Seismic anomalies are (D) Type I (blue dots), (E) Type II (red dots) and (F) Type III (yellow dots). (G) The map shows the location of the profile (red line); for a larger overview see Fig. 1). Dashed lines show the upper limit of the gas hydrate stability (GHS) for Atlantic Water (red dashed line) and Polar water (blue dashed line). Available seismic data is shown as white lines. Sediment cores are indicated as black crosses. Seismic data courtesy of TGS.

In the shallow subsurface, a bottom-simulating reflector parallel to the seafloor, with high amplitudes and reversed polarity, could indicate the presence of free gas that accumulates beneath stable gas hydrates. We find only a few patchy observations of a potential bottom-simulating reflector (Fig. 3A, Fig. 5E), none of which can be related with confidence to gas hydrates.

Type II anomalies are high-amplitude reflections of reversed polarity, and at greater depths (>75 mbsf). They tend to be distributed over several stratigraphic levels along individual faults (Fig. 5C), bound to or surrounding the salt domes or confined to stratigraphic-type traps, i.e., beneath Cenozoic (impermeable) marine shales (Fig. 2; Fig. 4D; Supplementary Fig. 1).

Type III anomalies are (sub-) horizontal high-amplitude reflections that often appear cut across strata, regardless of the surrounding geological structures, and can indicate a fluid contact between oil/gas, gas/water, or oil/water29. We find Type III anomalies in the sedimentary succession south of Belgica Trough, where they appear below flagged Type II anomalies in structural traps bound to faults or within pinch-out type stratigraphic traps (Fig. 5F). Structural traps are most common along northeast–southwest trending faults at the eastern boundary of Danmarkshavn Ridge (Fig. 2). Stratigraphic-type traps are found both in the northern and southern Danmarkshavn Basin (Fig. 5C, F), where they reflect the erosional contact between Jurassic to Cretaceous or the transition from Paleocene to Eocene strata20 (Fig. 2).

Fluid flow systems

In the northern Danmarkshavn Basin, seismic anomalies group along the flanks of the abundant salt diapirs (Fig. 3B/C and Fig. 4). The diapirs uplift the surrounding sedimentary succession and form effective traps that allow hydrocarbons to accumulate9 (Fig. 2). Here, Type III anomalies are associated with these traps along the edges of the salt diapirs, while Type II anomalies are distributed along the migration pathways (faults) leading out of the potential reservoirs at depth. Type I anomalies are associated with outcropping (pinch-out type) Jurassic to Cretaceous strata (Fig. 4). The seismic anomalies observed are in good agreement with the predicted conventional hydrocarbon reservoirs from the latest resource assessment9 (Fig. 3C). This resource assessment evaluates the yet-to-find potential of conventional hydrocarbons on the Greenland continental shelf and integrates seismic and gravity surveys, well data, scientific publications, and analogues from the Wandel Sea Basin and Norwegian Barents Sea shelf9.

In southern Danmarkshavn Basin, Type I and Type II anomalies are substantially shifted by up to 60 km landwards of the predicted hydrocarbon reservoirs (Fig. 3C). We interpret this shift to be caused by the migration of fluids along tilted permeable beds towards the inner shelf. This migration is accommodated by intercalated higher permeability sandy beds of the Mesozoic strata15. The overlying Cenozoic sediments provide the necessary seal to constrain the fluids along the tilted layers towards the heavily eroded formation subcrops6,15 (Fig. 2). An example of this is seen in the center of the South Danmarkshavn Basin where we can trace the migration of fluids over tens of kilometers (up to 50 km) towards the shoreline of Store Koldewey and Germania Land (Fig. 5A).

Secondary migration pathways exist related to crustal faulting, as documented by Type III seismic anomalies along the base of faulting and Type II anomalies at different levels along fault planes (Fig. 3). Major crustal faulting occurs in a N-S direction, paralleling the dominant major structural element15 (Fig. 1B). Faults display abundant seismic anomalies, especially along the edges of Danmarkshavn Ridge: Type III at depth, Type II along the fault planes at different depth intervals and Type I associated with fault tops. The tiers of seismic anomalies along fault planes document intermittent fluid transmission behavior30,31,32,33.

Natural seepage

N-alkane distributions from sediment samples retrieved from surface sediment cores above Type I seismic anomalies show an evident hump in the gas chromatograms, indicating the presence and seepage of (biodegraded) hydrocarbons (Supplementary Figs. 2 & 3). In particular, the gas chromatograms from extracted organic matter of sediment cores display odd/even n-alkane dominance in the n-C23 to n-C33 range and the presence of unresolved complex mixture (UCM), both of which indicate fresh seepage of petrogenic hydrocarbons to the seafloor. The relatively high concentration of iso-alkanes relative to n-alkanes in the front end of the chromatograms and the UCM further indicate ongoing biodegradation (Supplementary Fig. 3). From these sediment cores, certain biomarker parameters can indicate the age of the source rock based on the evolution of kerogen-forming organisms. According to sterane-based proxies (see Methods), the observed hydrocarbons originate from a Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous source rock (Supplementary Fig. 3), making in-situ seepage from the respective outcropping strata highly likely. This matches onshore findings of relict biodegraded crude oil in rock samples from Germania Land, which have been linked to long-distance migration of fluids from an unknown marine source of Jurassic-Cretaceous age34. Together, the seismic data and the sediment samples define a spatial and temporal geologic window across the NE Greenland shelf with a high seepage potential over the subcropping Mesozoic, i.e., Jurassic to Cretaceous strata (Fig. 2, Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. 1B).

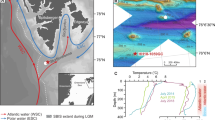

This scenario is consistent with the multibeam water column data that show acoustic flares in the water column over this ‘geologic’ window (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 1). We interpret these acoustic flares as indicators of active seepage of fluids in the form of bubbles released from the seafloor into the water column35. The multibeam survey covered 1050 km² of seafloor and imaged a total of 58 flares, of which 43 were heavily clustered within subcropping Upper Cretaceous strata south of Store Koldewey Island (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). These 43 flares were observed in 312 m ± 9 m water depth and reached heights of up to 230 m (average: 140 m ± 50 m), with six flares exceeding the multibeam swath. 11 flares occurred around the salt domes on IT-A, where we find flares in water depths between 157 and 318 m, reaching heights of up to 170 m, with five flares exceeding the multibeam swath. Flare heights are comparable to those observed in the Barents Sea, where thermogenic gas escapes5. Bubbles typically exchange their methane content with nitrogen and oxygen from the water column, resulting in low direct bubble transport of methane to the atmosphere36. Our bathymetric data show that the gas release is not linked to pockmarks (Fig. 6), likely reflecting a seafloor lithology that is not prone to pockmark formation37. Instead, seepage primarily originates from iceberg scours where there is a reduction in the thickness of the sedimentary cover and sealing unit38,39.

A Main map documenting natural seepage from sediment cores (APT ranking probable, possible, tentative, and outlier), water column imaging showing flares (green stars), onshore outcrops showing bitumen stains (blue dots), and oil slick mapping from Sentinel-1 satellite data. The upper limit of gas hydrate stability is shown for Atlantic water (dashed red line) and Polar water (dashed blue line). White dots indicate CTD stations (TUNU-VIII CTD0213, CAGE-KH-HACON21 CTD0515) used for gas hydrate stability calculations. Red lines indicate seismic profiles. Inter-trough areas (IT) are labelled IT-A. IT-B, IT-C after19. SKT Store Koldewey Trough, SKI=Store Koldewey Island. Locations and water column images from the multibeam echosounder (swath images) of (B, C) flare cluster observed during CAGE-KH-HACON21 occurring in between iceberg scours; (D, E) Subtle flare from CAGE-KH-HACON21cruise from inside an iceberg scour mark; (F, G) seepage clusters in the southern Danmarkshavn Basins offshore Store Koldewey Island recorded during TUNU-VIII. Note that flares appear close to the upper limit of the gas hydrate stability zone for Atlantic water (dashed red line).

A Histogram of flare observations plotted against water depth. B Polar Water (blue) and Atlantic Water (red) have distinct temperature and salinity characteristics that define the window of theoretical gas hydrate stability47. Numbers give the pinch-out depths, defined as the intersection of the base of gas hydrate stability with the seafloor.

The influence of gas hydrates

Cold water temperatures and high pressure are favorable conditions for gas hydrate formation. Only one seismic study from the NE Greenland continental slope has so far identified a bottom simulating reflector, possibly indicating gas hydrates40. The present-day hydrate stability is dictated by the hydrography of the shelf. While the inter-trough areas are dominated by cold and less saline Polar water resulting in shallow pinch-out depths, the deeper troughs host warm and saline Atlantic water (see Fig. 7). Since the shelf was almost fully glaciated during the last glacial maximum41,42,43,44 and gas hydrates respond slowly to increases in temperature45, remnants of (paleo-) gas hydrates may still exist in parts of the shelf as meta-stable reservoirs46.

We use bottom water temperatures and salinities typical for Polar and Atlantic water23 to calculate the phase boundary for dry (pure methane) gas47 and estimate the pinch-out (feather edge) depth, where the base of gas hydrate stability intersects the seafloor (Fig. 7). In the northern Danmarkshavn Basin, flares are observed to have shallower water depths (mean ~203 m) and seem independent of the gas hydrate stability zone (CTD0515: 34.6 PSU, 0.4 °C = 309 m). This area is dominated by Polar water, where pinch-out depths range between 249 and 294 m. Flares in the southern Danmarkshavn Basin cluster around 312 m ± 9 m water depth. This depth interval is dominated by Atlantic water, resulting in pinch-out depths between 326 m and 395 m (Fig. 7). Based on field measurements of water temperatures and salinities during the multibeam surveys, we find that the pinch-out depth is around 336 m (CTD0213: 1.3 °C, 34.9 PSU). Many of the flares are observed just above that upper limit of gas hydrate stability (Fig. 7), suggesting that hydrates are present in the shallow subsurface and may actively modulate natural seepage in the southern Danmarkshavn Basin.

Sea surface observations linked to natural seepage

At the sea surface, we have mapped several areas of suppressed sea surface roughness using SAR data collected between 2014 and 2025 across the entire NE Greenland shelf (Fig. 8). In the absence of ship traffic and other marine infrastructure, the sharp well-defined boundaries and the proximity to observed flares and seismic anomalies, we interpret these areas to be oil slicks caused by the release of natural oil from the seafloor. We observe slick anomalies both in the southern Danmarkshavn Basin and in the northern Danmarkshavn Basin above the centers of individual salt domes, where the water depth ranges from 140-305 m (Fig. 8). The slick anomalies appear consistent with the position of the observed seismic anomalies at depth and close to flares observed in water column (Fig. 8). Some oil slicks range in size between 4 and 77 km². Assuming 3.7 barrels of oil per day for a 1 km² oil slick this would equate to 14–285 barrels of oil per day48,49.

Reduced sea surface roughness is shown as black. Sea ice is visible in bright white. A White arrows indicate interpreted oil slicks (23.09.2023) outside of Shannon Island that follow the geological boundary between Paleocene/Cretaceous sediments. B Interpreted oil slick (20.09.2018) close to the seismic profile shown in Fig. 5 and above a Type I seismic anomaly in the subsurface. C Interpreted oil slick (24.09.2017) above the center of a salt dome in the northern part of the shelf. D Map of the subcropping strata beneath the Quaternary sediments15 showing the locations of (A–C) as white squares, observed seismic anomalies (blue, red, and yellow dots), mapped acoustic flares (green stars), and onshore seep indications (purple dot).

Natural hydrocarbon seepage at the Northeast Greenland continental shelf

We combine industry seismic, newly acquired multibeam bathymetry, and water column imaging from multibeam echosounder, organic geochemistry and sedimentology from sediment cores, and remote sensing data to provide the first evidence of fluid migration and natural seepage of hydrocarbons driven by a large and active petroleum system on the NE Greenland continental shelf (Figs. 3– 8). This area has a high hydrocarbon potential9,50 and a history of intense glacial erosion across the shelf during the glacial cycles since the late Miocene51 that effectively removed up to 2 km of uplifted sediments52, including cap rocks19,53,54 (Fig. 2). Organic geochemistry analyses on sediment cores show clear indications of fresh seepage of petrogenic hydrocarbons at the seafloor (Supplementary Fig. 2) supporting a Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous9,15 main source rocks, while abundant seismic anomalies in Eocene and younger strata indicate another potentially younger (Cenozoic) source rock55,56,57.

Based on seismic anomaly mapping, we can show that fluids migrate predominantly along the tilted sedimentary strata (Figs. 4, 5). This is because horizontal permeability in layered sedimentary rocks is usually higher than vertical permeability58. The migration of fluids along the landward tilting sedimentary strata of the study area (here ~2°) means that they are released at much shallower water depths and closer to shore, potentially increasing the amount of hydrocarbons that can reach the sea surface and atmosphere59.

A secondary fraction of fluid migration is accommodated by vertical movement along faults or focused along uplifted strata surrounding the salt domes (Fig. 4). Major crustal faulting has a N-S orientation, paralleling the dominant major structural elements15 (Fig. 1B). Faults are typically the most widespread and common structure with respect to focused fluid flow systems60. Their role in a hydrodynamic system depends permeability contrasts between the fault rock, its surrounding damage zone, and the adjacent strata61. Faults may function as conduits when their damage zone is more permeable than their host sequence, irrespective of their absolute displacement and rupture history. Fluid flow along the fault can be semi-permanent60,62. Fault activity, and therefore also fault permeability, is linked to pore-pressure. Increasing pore pressure, acting against an initially sealed fault, reduces the strength of the fault and may ultimately result in fault rupture and a (temporal) increase in permeability, permitting leakage of fluids from depth30,31,32,33. Thus, faults play an active role in controlling the expulsion of fluids at the seafloor by releasing subsurface overpressure63 or through reactivation due to an increase in shear stress along the fault64. Our data support this periodic behavior by showing tiers of seismic anomalies along the fault planes. However, this intermittent release of fluids from faults is less effective than the migration out of permeable beds, and we therefore consider these as secondary pathways.

Our study provides clear documentation of ongoing seafloor natural seepage of oil and gas offshore NE Greenland. This seepage is detected as flares through the water column (Fig. 6, Fig. 8). Considering that only a small fraction of the shelf has been surveyed, we expect that natural seepage is far more widespread. We also find indicators that at least a proportion of this natural seepage is locally reaching the sea surface (Figs. 6–8). Observed flares are exceptionally high (>200 m), sometimes exceeding the bathymetric swath, documenting a long lifetime of individual bubbles that ascend through the water column. The exceptional height of flares can be caused by larger bubble sizes, admixture of higher order hydrocarbons or coating bubbles with oil or gas hydrates65,66,67. Oil slick indications from SAR data throughout the past 10 years in the vicinity of the flares and above seismic anomalies (Fig. 8) are consistent with active seafloor seepage of oil reaching the sea surface. The combined seepage of oil and gas usually shows a more mature composition of escaping hydrocarbons and may result in oil-coated gas bubbles, which are less susceptible to dissolution68,69, both resulting in a longer lifespan of ascending bubbles and increasing the flux towards the sea surface and atmosphere.

Observations of natural seepage are highly dependent on the timing of data surveys. Seepage varies on small to large scales (seconds to millions of years) due to its sensitivity to changes in pressure, temperature, and salinity. For instance, ROV observations show intermittent trains of bubbles discontinuously (seconds to minutes) leaving the seafloor70, tides influence the seepage intensity over hours71, changing seasonal conditions result in varying fluxes from winter to summer72 and glacial/interglacial cycles73 or tectonic deformation74 change environmental parameters and thereby seepage over geologic time scales. Given the limited area surveyed (c.f. Fig. 6), we have likely only captured a small fraction of the natural seepage on the shelf, and more surveys are required to understand the natural variability of seepage in the area.

In the southern Danmarkshavn Basin, natural seepage correlates with the upper boundary of the gas hydrate stability zone (pinch out; Fig. 7), thereby confirming the presence of gas hydrates. The absence of clear BSRs in the seismic data either relates to the deep frequency of the data that poorly resolves the shallowest geology, to low gas (hydrate) concentrations in pore space28 or a gas hydrate stability zone in a transient state75. Methane hydrates are destabilized by increases in temperatures and decrease in pressure, which may occur at different climate change settings and processes76. Global warming leads to higher average ocean and air temperatures, leading to the melting of polar ice masses (lowering of pressure) but also increased sea level (higher pressure)77. While pressure perturbations are transmitted instantly into the subsurface, temperature changes may be delayed by thousands of years4. This contrast of environmental impacts challenges the assessment of the sensitivity of gas hydrates to rising temperatures and depressurization by thawing ice at high latitudes. For NE Greenland, postglacial rebound has uplifted the area by ~50–150 m during the past 20 kyr but is quiescent at present78, causing no further destabilization of gas hydrates. Given that the Atlantification of the NE Greenland shelf results in constantly increasing bottom water temperatures22, we expect temperature to be the main controlling factor influencing gas hydrate dissociation on the shelf over the coming decades.

Comparison of conjugate margins

The seepage offshore NE Greenland from an eroded uplifted sedimentary basin resembles the gas and oil seepage systems in the Barents Sea. The Barents Sea presents a distinct geological setting: extensive Cenozoic uplift and repeated Quaternary glaciations have eroded 1–2.5 km of sedimentary overburden, exhuming and partially uncapping hydrocarbon accumulations6. Consequently, roughly 21,700 seeps over ∼5000 km² have been documented, linked to faulted, variably eroded structural highs hosting Mesozoic reservoir formations12. This setting is analogous to our study area, where natural seepage is closely tied to erosion of uplifted sedimentary basins and resulting exhumed Jurassic to Cretaceous (Mesozoic) strata (Figs. 2, 6, 8, Supplementary Fig. 1). In the Barents Sea, gas hydrate occurrences are inferred from small, isolated patches with BSRs and so far, no methane hydrates have been retrieved from sea floor samples79. This setting would also be a feasible explanation for the missing BSRs on the NE Greenland Shelf. Given these commonalities, we expect a similar intense seepage to be observed if more scientific focus is put on the NE Greenland shelf and its natural seepage.

In contrast, along the western Svalbard continental margin, extensive natural seepage fueled by microbial (biogenic) sources has been documented35,70,80,81. Here, seepage is influenced by structural controls (i.e., Hornsund Fault Zone), which facilitate subseafloor fluid migration. In this area, seasonal fluctuations in bottom water temperatures seem to drive periodic variability of gas hydrate stability, modulating seabed release72,80. A similar sensitivity to gas hydrates is observed on the northern US Atlantic margin ( ~ 35–40°N), where extensive seepage ( > 1000 unique seeps) has been documented in 65–2160 m water depths, with more than 50% of all seeps near the upper limit of the gas hydrate stability zone ( ~ 500–575 mbsl)82. Seepage on this passive continental margin relates to a variety of processes driven from above the seafloor, such as erosion or mass wasting, and below the seafloor, such as migration along permeable strata and faults, as well as seepage above diapirs and pre-existing structures. The atmospheric contribution of both the Svalbard, and the US Atlantic margin is estimated to be negligible81,83.

Implications

With these original insights, we can provide first-order estimates of natural seepage on the NE Greenland shelf to the ocean and potentially the atmosphere. We estimate that around 3.1–6.7 Mt of thermogenic gas (mainly methane) from a single source have been released into seawater. The average size of conventional gas reservoir estimated by the Greenland Resource Assessment (c.f. Fig. 3C) is 100 million barrels of oil equivalent (mean derisked recoverable gas) or 12.5 million tons (Mt)9. Assuming a 20–35% leakage from these reservoirs since the Last Glacial Maximum (~ 20 kyr ago), consistent with observations from the conjugate margin in the Barents Sea84. For the 214 potential conventional hydrocarbon reservoirs (derisked gas mean: 2710 Mt methane) identified on the inner NE Greenland shelf9 (Fig. 3C), this would sum up to a 677–1460 Mt of methane (~ 0.5–1.1 Gt of carbon) since grounded ice retreated from the shelf around ~15 ka BP53,78,85,86. Much of the release would have been accommodated directly after the glacial retreat84. But, because of the considerable depths across the shelf (>200 m) and the near-continuous sea ice cover throughout the year, a substantial portion of the released methane would have dissolved in the water column36, oxidized to carbon dioxide, or be consumed by methanogenic microbes6,87.

Modelling work from the Norwegian continental shelf shows that biodegradation (consumption by microbes) substantially reduces the amount of methane that reaches the atmosphere88. For an average methane retention time of 9–16 days, about 32–43% reaches the atmosphere from 65 m water depth while for >300 m all methane would be consumed. However, retention times vary from days to years81,89, changing the atmospheric contributions substantially. During ice-free conditions and in the shallow water depths of the inter-trough areas (<200 m, Fig. 6), a comprehensive study from the US continental margin suggests that 25-70% of the released gas (equals 170-1021 Mt of methane) could have reached the surface waters and be exchanged with the atmosphere83. With a global warming potential of 28 times as much as CO2 over 100 years2, this would result in 4.7–28.6 Gt of CO2-equivalent emissions. For comparison, the production and use of fossil fuels emits 120 (117–125) Mt of methane into the atmosphere annually90.

The potential release of such substantial amounts of hydrocarbons at the seafloor may impact on the overall functioning of the marine ecosystem and shift involved biogeochemical cycles. Implications would involve enhanced oxygen depletion91 and increased ocean acidification92. In turn, the release of fluids with dissolved nutrients at natural cold seeps can enhance primary production93,94,95,96. As a result, natural seepage sites on the NE Greenland shelf have the potential to be ‘oases of life beneath the ice’, which will use the sustained release of fluids as the base for the food web and thereby act as ‘benthic filter’97,98. However, our knowledge of the impact of fluid seepage on the biosphere in NE Greenland Shelf remains poorly constrained. Our new discoveries of widespread natural seepage and the underlying fluid flow systems in NE Greenland represent a substantial advance in our understanding of natural seepage across the Arctic. Given the high seepage potential, however, our findings further highlight the substantial gaps that remain in our ability to better constraint Arctic methane budgets and assess their sensitivity to ongoing environmental and climatic change.

Methods

Water column and sea-floor imaging

All multibeam data have been acquired using the hull-mounted Kongsberg EM302 multibeam system onboard R/V Kronprins Haakon during two surveys (15.−18.10.2021: CAGE-KH-HACON21, 26.−31.08.2022: TUNU-VIII). The EM302 multibeam system registers not only the sea floor but also the amplitude of each beam reflection as well as a sidescan signal for each beam (so-called snippets). It also allows recording the entire water column. The amplitude signals correspond to the intensity of the echo received at each beam. It is registered as the logarithm of the ratio between the intensity of the received signal and the intensity of the output signal, which results in negative decibel values. The water column data correspond to the intensity of the echoes recorded from the instant the output signal is produced.

Data from the water column can be used for flare detection as gas bubbles create a strong backscatter in the acoustic signal, called flares. Acoustic flares indicate a wide range of gas emission strengths as documented by comparative studies on the Svalbard margin, where strong flares correspond to an average of six clustered streams of bubbles, while weak flare typically represent only a single bubble stream35. We conducted data post-processing with QPS Fledermaus FM Midwater to image and pick flares in the water column across the cruise tracks. The location of acoustic anomalies associated with flares was picked as close to the base of the flare column as the data would allow. Data acquired during ice breaking is particularly noisy, making the identification of some flares difficult in parts of the dataset. Here, we only show flares that are picked within multibeam data of good enough quality to avoid misinterpretation of flares. Noise caused by ice breaking creates beam-parallel anomalies in the water column (i.e., vertical only underneath the ship (nadir zone), while anomalies from fluid seepage (e.g., gas) are identified by near-vertical to along-ocean current deflected anomalies that cross several beams within each ping and are recorded in at least two consecutive pings.

Satellite image analysis

Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) is a reliable and well-established technique to detect and map oil slicks at the sea surface. The Sentinel-1 mission provides data from a dual-polarization SAR instrument at 5.405 GHz99. The vertical polarization of Sentinel-1 SAR data is usually used to detect oil slicks, but in polar regions, only the horizontal component is available. However, recent publications have shown that horizontally polarized Sentinel-1 data can be successfully used to detect natural oil slicks in Arctic waters6,49. Areas of suppressed sea surface roughness can be caused by oil slicks, but also result from biological slicks or low-wind areas48. These observations are limited to the short period of ice-free conditions on the NE Greenland shelf100, which usually only occurs between August to October. Criteria for identifying oil slicks in Sentinel-1 SAR images include low backscatter intensity, elongated shape, persistence over time, proximity to known sources (oil rigs, ships), and wind speed conditions48. Sentinel-1 SAR satellite images with extra-wide-angle horizontal polarization (EW-HH) from 2014-2025 are available through the Copernicus Open Access Hub (www.scihub.copernicus.eu). Here, we use deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) with a U-Net architecture, specifically utilizing ResNet-101 as the encoder backbone, to process SAR data obtained from the Sentinel-1 satellite and to identify potential oil slicks. All oil slick detections were manually checked, and we interpreted the oil slick outline manually in ArcGIS based on low backscatter areas with an oil slick appearance.

Seismic data analysis

Here, we use a large industry seismic data set acquired over the past 20 years on the NE Greenland shelf by various companies and institutions (Table 1). The resulting regional 2D seismic grid covers the entire NE Greenland shelf from North to South (800 km) and from the coast in the West (~100 m water depth) to the base of the slope in the East (~3500 m water depth). The density of the seismic grid reduces from 79°N because of the heavily ice infested waters. All data are available as post-stack time-migrated 2D seismic profiles from Greenland National Petroleum Data Repository (greenpetrodata.gl).

Seismic reflectivity is sensitive to fluid in the pore space of marine sediments, especially gas, as it has a strong influence on seismic velocities and energy absorption of seismic waves26,28. Thus, seismic amplitude anomalies can be used to map fluid accumulations and entire fluid flow systems in the subsurface27. The following seismic anomalies are used to identify fluids: (1) Acoustic blanking, which describes the energy absorption of a seismic wave due to the presence of free gas and the subsequent amplitude dimming of underlying reflectors, i.e. dim spots26,29; (2) Velocity pushdown is an apparent depression of seismic reflectors (in the time domain) due to the decrease of seismic velocities in the accumulated gas phase above the reflectors26,28; (3) Type I (close to the seafloor) and Type II (at greater depth) anomalies are high amplitude seismic reflections. In the case of a polarity reversal (with respect to the seafloor) they indicate the existence of free gas in the pore space26,101, (4) Type III anomalies, which manifest themselves in seismic data as horizontal (high-amplitude) reflections that cut dipping strata, likely indicate a fluid contact (oil/gas, gas/water, oil/water) inside a potential reservoir29.

Core data

Since 2011, Volcanic Basin Energy Research AS (VBER) and TGS-NOPEC Geophysical Company ASA (TGS) have collectively acquired 190 m of sediment cores from 164 gravity core sampling stations that were selected based on TGS seismic data on the NE Greenland shelf. The gravity cores targeted truncated strata subcropping at the seabed for tying the stratigraphy to the seismic data and fault terminations for identification of macroseeps. The gravity corer has a lead weight of 800 kg attached to a three-meter-long carbon steel core barrel. A transparent liner was inserted into the core barrel and secured in place using a core catcher and cutting shoe (bit). The gravity corer was dropped in free fall from 50 m above the seafloor to maximize penetration into the seabed. Sediment samples were taken from the lowermost part of the gravity cores, placed in sealed tin cans, and stored in a conventional −20 °C freezer. Shore based analyses included headspace gas and gas chromatography on extracted organic matter (GC of EOM), as well as gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) were carried out by Applied Petroleum Technology (APT) laboratory, which follows the standard procedures from NIGOGA (Norwegian Industry Guide to Organic Geochemical Analysis) that defines analytical procedures, notation and reporting guidelines102.

Gas chromatography

Headspace gas was measured using a flame ionization detector (FID) for hydrocarbons, and two thermal conductivity detectors (TCD) for CH4, H2, CO2, N2 and O2/Ar. The GC of EOM was measured using a HP5890 II instrument, and the GC-MS with a Micromass ProSpec high-resolution instrument, both following standard temperature programs. Samples with gas chromatograms displaying a thermogenic signature were further analyzed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) on saturated and aromatic hydrocarbons.

The GC of the EOM typically shows acyclane distributions indicating bitumen from immature recent organic matter (OM), with a high odd-to-even predominance (OEP) of n-alkanes (C23-C33) from terrestrial sources. n-Alkane distributions help distinguish between immature organic matter (OM) and petrogenic hydrocarbons. Natural oil exhibits a broad n-alkane range, often with an unresolved complex mixture (UCM) due to biodegradation. Active seeps continuously supply fresh oil, forming a growing petrogenic UCM. A high odd or even C-number preference indicates immaturity, while a smooth distribution with a carbon preference index (CPI) near unity suggests petrogenic hydrocarbons.

Where the GC of EOM showed traces of hydrocarbons, APT conducted further analysis by GC-MS of both saturated biomarkers and aromatic hydrocarbon distributions. Certain biomarker parameters indicate the age of the source rock based on the evolution of kerogen-forming organisms. However, many are derived from marine oils and may be unreliable for terrestrial OM contributions. Since most require non-standard GC-MS analysis, only a few were evaluated in this study.

The C28/C29 sterane ratio in marine-sourced oils increases systematically from the Proterozoic, possibly due to the evolution of dinoflagellates, coccolithophores, silicoflagellates, and diatoms103. The extended tricyclic terpane ratio (ETR) distinguishes Triassic (≥ 0.67) from Jurassic oils (≤ 0.67), with a sharp drop at the Triassic-Jurassic extinction and further decline in the Toarcian due to reduced cheilanthane-producing organisms104. Sterane distributions suggest extracts originate from Triassic or Jurassic sources [28ββ/(28ββ + 29ββ) ~ 25−50%], aligning with the Jurassic NSO-1 reference oil (~ 46%). The ETR of shallow core samples ranges from 0.25 to 0.60 (NSO-1 ~ 0.37), supporting a Jurassic origin. A cross-plot of sterane ratios and ETR places most samples in the Jurassic range, with only one slightly within the Paleozoic zone, making a post-Paleozoic source most plausible.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Bathymetric data are accessible via The International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean Version 5.0 (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04278-w). All seismic data are available as post-stack time-migrated 2D seismic profiles from Greenland National Petroleum Data Repository (greenpetrodata.gl). Seismic and geologic data (Joint EGS: TGS & VBER) can be accessed via academic license agreement from TGS and VBER. Sentinel-1 SAR satellite images with extra-wide-angle horizontal polarization (EW-HH) from 2014-2025 are available through the Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem (www.dataspace.copernicus.eu).

References

Saunois, M. et al. The Global Methane Budget 2000-2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 1561–1623 (2020).

Shindell, D. T. et al. Improved Attribution of Climate Forcing to Emissions. Science 326, 716–718 (2009).

Nisbet, E. G. et al. Atmospheric Methane: Comparison Between Methane’s Record in 2006-2022 and During Glacial Terminations. Global Biogeochem. Cy 37, 1–33 (2023).

Ruppel, C. D. & Kessler, J. D. The interaction of climate change and methane hydrates. Rev. Geophysics 55, 126–168 (2017).

Andreassen, K. et al. Massive blow-out craters formed by hydrate-controlled methane expulsion from the Arctic seafloor. Science 356, 948–952 (2017).

Serov, P., Mattingsdal, R., Winsborrow, M., Patton, H. & Andreassen, K. Widespread natural methane and oil leakage from sub-marine Arctic reservoirs. Nat. Commun. 14, 1782 (2023).

James, R. H. et al. Effects of climate change on methane emissions from seafloor sediments in the Arctic Ocean: A review. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, 283–299 (2016).

Etiope, G. & Schwietzke, S. Global geological methane emissions: An update of top-down and bottom-up estimates. Elementa-Sci. Anthrop. 7, 1–9 (2019).

Dam, G. et al. Greenland Resource Assessment, Assessment Unit 4–North-East Greenland-Project Summary, 1–26 (Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Copenhagen, 2021).

Hamann, N., Whittaker, R. & Stemmerik, L. Geological development of the Northeast Greenland shelf, 1–16 (Geological Society, London, 2005).

Christiansen, F. G. Greenland petroleum exploration history: Rise and fall, learnings, and future perspectives. Resour. Policy 74, 1–21 (2021).

Serov, P., Andreassen, K., Winsborrow, M., Mattingsdal, R. & Patton, H. Geological and glaciological controls of 21,700 active methane seeps in the northern Norwegian Barents sea. Front. Earth Sc.-Switz. 12, 1–20 (2024).

Lasabuda, A. P. E. et al. Cenozoic uplift and erosion of the Norwegian Barents Shelf-A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 217, 1–35 (2021).

Meredith, M. et al. Polar regions. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, IPCC (eds Pörtner H.-O. et al.). Cambridge University Press (2019).

Fyhn, M. B. W. & Hopper, J. R. NE Greenland Composite Tectono-Sedimentary Element, northern Greenland Sea and Fram Strait. Geological Society, London, Memoirs 57, M57-2017-2012 (2024).

Christiansen, F., Dam, G., Piasecki, S., Stemmerik, L. & Spencer, A. A review of Upper Palaeozoic and Mesozoic source rocks from onshore East Greenland. Gener., Accumul. Prod. Eur.’s. hydrocarbons II Spec. Publ. Eur. Assoc. Pet. Geoscientists 2, 151–161 (1992).

Reynolds, P. et al. Hydrothermal vent complexes offshore Northeast Greenland: A potential role in driving the PETM. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 467, 72–78 (2017).

Piepjohn, K., von Gosen, W. & Tessensohn, F. The Eurekan deformation in the Arctic: an outline. J. Geol. Soc. 173, 1007–1024 (2016).

Arndt, J. E. et al. A new bathymetry of the Northeast Greenland continental shelf: Constraints on glacial and other processes. Geochem Geophy Geosy 16, 3733–3753 (2015).

Fyhn, M. B. W. et al. Three-phased latest Jurassic-Eocene rifting and mild mid-Cenozoic compression offshore NE Greenland. Tectonophysics 815, 228990 (2021).

Hamann, N. E., Whittaker, R. C. & Stemmerik, L. Geological development of the Northeast Greenland Shelf. In: Petroleum Geology: North-West Europe and Global Perspectives—Proceedings of the 6th Petroleum Geology Conference (eds Doré A. G., Vining B. A.). Geological Society of London (2005).

Gjelstrup, C. V. B. et al. Vertical redistribution of principle water masses on the Northeast Greenland Shelf. Nat. Commun. 13, 7660 (2022).

Willcox, E. W. et al. An Updated View of the Water Masses on the Northeast Greenland Shelf and Their Link to the Laptev Sea and Lena River. J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans 128, 1–16 (2023).

Schaffer, J. et al. Warm water pathways toward Nioghalvfjerdsfjorden Glacier, Northeast Greenland. J. Geophys Res-Oceans 122, 4004–4020 (2017).

Wekerle, C. et al. Atlantic Water warming increases melt below Northeast Greenland’s last floating ice tongue. Nat. Commun. 15, 1336 (2024).

White, J. E. Computed Seismic Speeds and Attenuation in Rocks with Partial Gas Saturation. Geophysics 40, 224–232 (1975).

Berndt, C. Focused fluid flow in passive continental margins. Philos. T R. Soc. A 363, 2855–2871 (2005).

Domenico, S. N. Effect of Brine-Gas Mixture on Velocity in an Unconsolidated Sand Reservoir. Geophysics 41, 882–894 (1976).

Loseth, H., Gading, M. & Wensaas, L. Hydrocarbon leakage interpreted on seismic data. Mar. Pet. Geol. 26, 1304–1319 (2009).

Wiprut, D. & Zoback, M. D. Fault reactivation and fluid flow along a previously dormant normal fault in the northern North Sea. Geology 28, 595–598 (2000).

Grollimund, B. & Zoback, M. D. Impact of glacially induced stress changes on fault-seal integrity offshore Norway: Reply. Aapg Bull. 89, 275–279 (2005).

Abrams, M. A. Significance of hydrocarbon seepage relative to petroleum generation and entrapment. Mar. Pet. Geol. 22, 457–477 (2005).

Egholm, D. L., Clausen, O. R., Sandiford, M., Kristensen, M. B. & Korstgård, J. A. The mechanics of clay smearing along faults. Geology 36, 787–790 (2008).

Christiansen, F. G., Bojesen-Koefoed, J. A., Jensen, S. M. & Stemmerik, L. Oil seep in basement, Germania Land, North-East Greenland. Geological Survey of Greenland (1991).

Sahling, H. et al. Gas emissions at the continental margin west of Svalbard: mapping, sampling, and quantification. Biogeosciences 11, 6029–6046 (2014).

von Deimling, J. S. et al. Quantification of seep-related methane gas emissions at Tommeliten, North Sea (vol 31, pg 867, 2011). Cont. Shelf Res 31, 1943–1943 (2011).

Böttner, C. et al. The Enigmatic Pockmarks of the Sandy Southeastern North Sea. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 25, 1–20 (2024).

Winsborrow, M. et al. Regulation of ice stream flow through subglacial formation of gas hydrates. Nat. Geosci. 9, 370 (2016).

Brown, C. S., Newton, A. M. W., Huuse, M. & Buckley, F. Iceberg scours, pits, and pockmarks in the North Falkland Basin. Mar. Geol. 386, 140–152 (2017).

Geissler, W. H., Pulm, P. V., Jokat, W. & Gebhardt, A. C. Indications for the occurrence of gas hydrates in the Fram Strait from heat flow and multichannel seismic reflection data. J. Geol. Res. 2014, 582424 (2014). ID.

Cofaigh, C. O. et al. Shelf-edge glaciation offshore of northeast Greenland during the last glacial maximum and timing of initial ice-sheet retreat. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 359, 1–18 (2025).

Rasmussen, T. L., Pearce, C., Andresen, K. J., Nielsen, T. & Seidenkrantz, M. S. Northeast Greenland: ice-free shelf edge at 79.4° N around the Last Glacial Maximum 25.5–17.5 ka. Boreas 51, 759–775 (2022).

Laberg, J. S., Forwick, M. & Husum, K. New geophysical evidence for a revised maximum position of part of the NE sector of the Greenland ice sheet during the last glacial maximum. arktos 3, 3 (2017).

Olsen, I. L., Rydningen, T. A., Forwick, M., Laberg, J. S. & Husum, K. Last glacial ice sheet dynamics offshore NE Greenland - a case study from Store Koldewey Trough. Cryosphere 14, 4475–4494 (2020).

Ruppel, C. D. & Waite, W. F. Timescales and Processes of Methane Hydrate Formation and Breakdown, With Application to Geologic Systems. J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea. 125, e2018JB016459 (2020).

Gu, G. S. et al. Abundant Early Palaeogene marine gas hydrates despite warm deep-ocean temperatures. Nat. Geosci. 4, 848–851 (2011).

Tishchenko, P., Hensen, C., Wallmann, K. & Wong, C. S. Calculation of the stability and solubility of methane hydrate in seawater. Chem. Geol. 219, 37–52 (2005).

Garcia-Pineda, O., MacDonald, I. R., Li, X. F., Jackson, C. R. & Pichel, W. G. Oil Spill Mapping and Measurement in the Gulf of Mexico With Textural Classifier Neural Network Algorithm (TCNNA). Ieee J.-Stars 6, 2517–2525 (2013).

Panieri, G. et al. An Arctic natural oil seep investigated from space to the seafloor. Sci. Total Environ. 907, 167788 (2024).

Gautier, D. L. et al. Oil and gas resource potential north of the Arctic Circle. Geol. Soc. Mem. 35, 151–161 (2011).

Jakobsen, F. W. et al. Continental shelf glaciations off Northeast Greenland since the late Miocene. EGUsphere 2025, 1–30 (2025).

Japsen, P., Green, P. F., Bonow, J. M., Bjerager, M. & Hopper, J. R. Episodic burial and exhumation in North-East Greenland before and after opening of the North-East Atlantic. Geus B 45, 1–145 (2021).

López-Quirós, A. et al. Retreat patterns and dynamics of the former Norske Trough ice stream (NE Greenland): An integrated geomorphological and sedimentological approach. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 325, 1–24 (2024).

Arndt, J. E., Jokat, W. & Dorschel, B. The last glaciation and deglaciation of the Northeast Greenland continental shelf revealed by hydro-acoustic data. Quat. Sci. Rev. 160, 45–56 (2017).

Knies, J. & Mann, U. Depositional environment and source rock potential of Miocene strata from the central Fram Strait: introduction of a new computing tool for simulating organic facies variations. Mar. Pet. Geol. 19, 811–828 (2002).

Speelman, E. N. et al. The Eocene Arctic Azolla bloom: environmental conditions, productivity and carbon drawdown. Geobiology 7, 155–170 (2009).

Cox, D. R., Huuse, M., Newton, A. M. W., Gannon, P. & Clayburn, J. Slip sliding away: Enigma of large sandy blocks within a gas-bearing mass transport deposit, offshore northwestern Greenland. Aapg Bull. 104, 1011–1043 (2020).

Shedid, S. A. Vertical-horizontal permeability correlations using coring data. Egypt. J. Pet. 28, 97–101 (2019).

Davies, R. J. et al. Long-distance migration and venting of methane from the base of the hydrate stability zone. Nat. Geosci. 17, 32–37 (2024).

Cartwright, J. The impact of 3D seismic data on the understanding of compaction, fluid flow and diagenesis in sedimentary basins. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 164, 881–893 (2007).

Aydin, A. Fractures, faults, and hydrocarbon entrapment, migration and flow. Mar. Pet. Geol. 17, 797–814 (2000).

Hooper, E. C. D. Fluid Migration Along Growth Faults in Compacting Sediments. J. Pet. Geol. 14, 161–180 (1991).

Elger, J. et al. Submarine slope failures due to pipe structure formation. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–6 (2018).

Hornbach, M. J., Saffer, D. M. & Holbrook, W. S. Critically pressured free-gas reservoirs below gas-hydrate provinces. Nature 427, 142–144 (2004).

Solomon, E. A., Kastner, M., MacDonald, I. R. & Leifer, I. Considerable methane fluxes to the atmosphere from hydrocarbon seeps in the Gulf of Mexico. Nat. Geosci. 2, 561–565 (2009).

Rehder, G., Brewer, P. W., Peltzer, E. T. & Friederich, G. Enhanced lifetime of methane bubble streams within the deep ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 1–4 (2002).

Leifer, I., Clark, J. F. & Chen, R. F. Modifications of the local environment by natural marine hydrocarbon seeps. Geophys Res Lett. 27, 3711–3714 (2000).

Leifer, I. A Synthesis Review of Emissions and Fates for the Coal Oil Point Marine Hydrocarbon Seep Field and California Marine Seepage. Geofluids 2019, 1–49 (2019).

Leifer, I. & Judd, A. G. Oceanic methane layers: the hydrocarbon seep bubble deposition hypothesis. Terra Nova 14, 417–424 (2002).

Ferré, B. et al. Contrasting Methane Seepage Dynamics in the Hola Trough Offshore Norway: Insights From Two Different Summers. J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans 129, 1–16 (2024).

Sultan, N., Riboulot, V., Dupré, S., Garziglia, S. & Ker, S. The Role of Earth Tides in Reactivating Shallow Faults and Triggering Seafloor Methane Emissions. J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea. 129, 1–25 (2024).

Ferré, B. et al. Reduced methane seepage from Arctic sediments during cold bottom-water conditions. Nat. Geosci. 13, 144 (2020).

Serov, P. et al. Postglacial response of Arctic Ocean gas hydrates to climatic amelioration. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6215–6220 (2017).

Plaza-Faverola, A. et al. Role of tectonic stress in seepage evolution along the gas hydrate-charged Vestnesa Ridge, Fram Strait. Geophys Res Lett. 42, 733–742 (2015).

Colin, F., Ker, S., Riboulot, V. & Sultan, N. Irregular BSR: Evidence of an Ongoing Reequilibrium of a Gas Hydrate System. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, 1–10 (2020).

Nisbet, E. Climate Change and Methane. Nature 347, 23–23 (1990).

Mazzini, A. et al. A climatic trigger for the giant Troll pockmark field in the northern North Sea. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 464, 24–34 (2017).

Tabone, I., Robinson, A., Montoya, M. & Alvarez-Solas, J. Holocene thinning in central Greenland controlled by the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream. Nat. Commun. 15, 6434 (2024).

Minshull, T. A. et al. Hydrate occurrence in Europe: A review of available evidence. Mar. Pet. Geol. 111, 735–764 (2020).

Berndt, C. et al. Temporal Constraints on Hydrate-Controlled Methane Seepage off Svalbard. Science 343, 284–287 (2014).

Mau, S. et al. Widespread methane seepage along the continental margin off Svalbard - from Bjornoya to Kongsfjorden. Sci. Rep.-UK 7, 1–13 (2017).

Ruppel, C. D. et al. Methane seeps on the US Atlantic margin: An updated inventory and interpretative framework. Mar. Geol. 471, 107287 (2024).

Joung, D., Ruppel, C., Southon, J., Weber, T. S. & Kessler, J. D. Negligible atmospheric release of methane from decomposing hydrates in mid-latitude oceans. Nat. Geosci. 15, 885 (2022).

Kishankov, A. et al. Hydrocarbon leakage driven by Quaternary glaciations in the Barents Sea based on 2D basin and petroleum system modeling. Mar. Petrol Geol. 138, 105557 (2022).

Davies, J. et al. Linkages between ocean circulation and the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream in the Early Holocene. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 286, 1–19 (2022).

Hansen, K. E. et al. Deglacial to Mid Holocene environmental conditions on the northeastern Greenland shelf, western Fram Strait. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 293, 1–20 (2022).

Römer, M., Sahling, H., Pape, T., Bohrmann, G. & Spiess, V. Quantification of gas bubble emissions from submarine hydrocarbon seeps at the Makran continental margin (offshore Pakistan). J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans 117, 1–19 (2012).

Nordam, T. et al. Fate of Dissolved Methane from Ocean Floor Seeps. Environ. Sci. Technol. 59, 8516–8526 (2025).

Griffiths, R. P., Caldwell, B. A., Cline, J. D., Broich, W. A. & Morita, R. Y. Field Observations of Methane Concentrations and Oxidation Rates in the Southeastern Bering Sea. Appl Environ. Micro. 44, 435–446 (1982).

Saunois, M. et al. Global Methane Budget 2000–2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2024, 1–147 (2024).

Boetius, A. & Wenzhöfer, F. Seafloor oxygen consumption fuelled by methane from cold seeps. Nat. Geosci. 6, 725–734 (2013).

Biastoch, A. et al. Rising Arctic Ocean temperatures cause gas hydrate destabilization and ocean acidification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, 1–5 (2011).

Pohlman, J. W. et al. Enhanced CO2-uptake at a shallow Arctic Ocean seep field overwhelms the positive warming potential of emitted methane. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 5355–5360 (2017).

Åström, E. K. L., Sen, A., Carroll, M. L. & Carroll, J. Cold Seeps in a Warming Arctic: Insights for Benthic Ecology. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 1–25 (2020).

Sibuet, M. & Olu, K. Biogeography, biodiversity and fluid dependence of deep-sea cold-seep communities at active and passive margins. Deep-Sea Res Pt Ii 45, 517 (1998).

Panieri, G. et al. Sanctuary for vulnerable Arctic species at the Borealis Mud Volcano. Nat. Commun. 16, 504 (2025).

Steinle, L. et al. Water column methanotrophy controlled by a rapid oceanographic switch. Nat. Geosci. 8, 378 (2015).

Niemann, H. et al. Novel microbial communities of the Haakon Mosby mud volcano and their role as a methane sink. Nature 443, 854–858 (2006).

Torres, R. et al. GMES Sentinel-1 mission. Remote Sens Environ. 120, 9–24 (2012).

Millinge, O., Böttner, C. & Asif, M. Deep Learning based Identification of Oil-Slick Emissions in the Arctic Using Satellite SAR Data. In: NSG 2024 4th Conference on Airborne, Drone and Robotic Geophysics). European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers (2024).

Domenico, S. N. Elastic Properties of Unconsolidated Porous Sand Reservoirs. Geophysics 42, 1339–1368 (1977).

Weiss, H. et al. NIGOGA-the Norwegian industry guide to organic geochemical analyses. Norsk Hydro, Statoil, Geolab Nor, SINTEF Petroleum Research and the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate, 1-102 (2000).

Grantham, P. & Wakefield, L. Variations in the sterane carbon number distributions of marine source rock derived crude oils through geological time. Org. Geochem. 12, 61–73 (1988).

Peters, K. E., Walters, C. C. & Moldowan, J. M. The biomarker guide. Cambridge University Press (2005).

Jakobsson, M. et al. The International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean Version 5.0. Sci. Data 11, 1–22 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the captains, crews, and shipboard scientific parties of R/V Kronprins Haakon during expeditions CAGE-KH-HACON21 (chief scientist Stefan Bünz) and TUNU-VIII (chief scientist Arve Lynghammar). We acknowledge the work done during joint VBER/TGS campaigns EGS11, EGS12, and EGS16. Seismic Data courtesy of TGS. Seismic and geologic data (Joint EGS: TGS & VBER) kindly provided under academic license agreement NL1123-377. We are thankful to the academic licensing programs of IHS for providing the Kingdom Seismic Interpretation Software, ESRI for providing the ArcGIS/Pro Software, and QPS for providing Qimera Software. This work has been funded by the European Union under Horizon Europe grant agreement No 101060851 (GreenFlux). The contribution of MSS was supported from Horizon Europe grant agreement No. 101136480 (SEA-Quester). The contributions of FWJ and MW form part of iC3: Centre for ice, Cryosphere, Carbon, and Climate, and were supported by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme, project number 332635. MW also acknowledges support from ERC grant i2B, 101118519. StP and AM acknowledge funding from the National Centre for Sustainable Subsurface Utilization of The Norwegian Continental Shelf (Research Council of Norway project 331644) and the WELLFATE project 344447). JSL acknowledges support from the Research Council of Norway through the DYPOLE project (grant no. 325984). We thank Michael B. Fyhn and Rune Mattingsdal for their constructive discussions. Finally, we thank the editor Somaparna Ghosh and three anonymous reviewers for a constructive review process that improved the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: C.B., F.W.J., T.N., M.W., K.J.A., M.S.S.; Methodology: C.B., F.W.J., T.N., St.P., A.M., Sv.P., O.J.S.M., M.R.A., J.S.L., M.S.S.; Data Curation: Sv.P., J.H., R.M., M.S.S.; Formal Analysis: C.B., F.W.J., T.N., M.W., St.P., A.M., Sv.P., O.J.S.M., M.R.A., J.S.L., J.H., M.S.S.; Writing – Original Draft: C.B., F.W.J., T.N., M.W., K.J.A., M.S.S.; Writing – Review & Editing: C.B., F.W.J., T.N., M.W., St.P., A.M., Sv.P., K.J.A., O.J.S.M., M.R.A., J.S.L., J.H., R.M., M.S.S.; Supervision: T.N., M.W., J.S.L., K.J.A., M.S.S.; Funding Acquisition: C.B., T.N., M.W., St.P., A.M., Sv.P., K.J.A., J.S.L., R.M., M.S.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Dennis Darby and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Carlos Vargas, Somaparna Ghosh, Carolina Ortiz Guerrero [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Böttner, C., Jakobsen, F.W., Nielsen, T. et al. Natural hydrocarbon seepage at the Northeast Greenland continental shelf. Commun Earth Environ 6, 879 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02932-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02932-8