Abstract

Marine calcifiers support ecosystem services, including shell fisheries and coral reefs. Constraining the saturation state of the calcification media of these organisms is essential to understand the response of biomineralisation to environmental change. Here we synthesise aragonite over variable pH, saturation state, temperature, and in the presence of simple biomolecules. We show that the lithium/magnesium distribution coefficient, relating aragonite and precipitation fluid compositions, is significantly affected by precipitation rate but not by temperature or pH. Precipitation rate reflects saturation state and temperature, so lithium/magnesium of biogenic aragonite can be used to calculate mineral precipitation rate and, if the precipitation temperature is known, to reconstruct calcification medium saturation state. Applying the distribution coefficients to a published calcifier dataset indicates that calcification media saturation state is ca. 9 to 13 at 18–30 °C and ca. 6 to 10 at 10–18 °C. Coral calcification media saturation state varies between ocean sites, species, and reef zones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Calcification is the production of CaCO3 structures, e.g., shells, plates, and skeletons, by organisms including corals, molluscs, and foraminifera. This process provides organisms with tissue support and protection from predators and the environment, constructs habitat spaces for other organisms (e.g., coral reefs), and plays an important role in carbon and calcium biogeochemical cycles1. Inorganic precipitation rates of CaCO3 reflect seawater CaCO3 saturation state, Ω, which is a function of seawater [Ca2+] and [CO32-]2 and the presence of other ions, e.g., Mg2+, SO42-, and PO43-3. Biogenic CaCO3 structures are formed from calcification media hosted intracellularly4,5,6 and extracellularly6,7. The calcification media are typically sourced from seawater4,8, but many organisms elevate media pH7,9,10, shifting the dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) equilibrium in favour of CO32- and promoting the formation of CaCO3. Therefore, fully characterising calcification media Ω (ΩCM) is essential to understand biomineralisation processes and to predict the effects of future environmental change on marine ecosystem services. Aragonite B/Ca has been used to infer calcification media [CO32-]11 in combination with aragonite δ11B used to indicate calcification media pH12. However, a recent study indicates that aragonite B/Ca is not influenced by precipitating fluid [CO32-] at the pH and DIC conditions of tropical coral calcification sites13, while δ11B estimates of coral calcification media pH are substantially higher than estimates from the pH-sensitive dye SNARF-1 in the extracellular calcification site14.

Here, we determine how ΩAr (aragonite saturation state), temperature, pH, and mineral growth rate (R) influence Mg and Li partitioning in aragonite, and we explore Li/Mg as a proxy of aragonite growth rate and ΩAr. We precipitate aragonite in vitro from artificial seawater over a range of pH and aragonite saturation states (ΩAr), including those inferred to occur in coral calcification media13. We combine a pH stat titrator, a Ca2+ dosing system, and a gas control apparatus to ensure that pH, Ω, and [Ca2+] remain essentially constant within each precipitation. [CO32-] and pH covary between precipitations at atmospheric CO213, so we conduct experiments under different CO2 atmospheres to deconvolve the influences of pH and [CO32-] on Mg and Li partitioning. Calcification is affected by organic matrices at the calcification site, which influence mineral deposition15, so we also test the effect of common biomineral amino acids on aragonite Li and Mg incorporation.

Results and Discussion

pH and growth rate influences on DLi/Mg

Firstly, we analyse a suite of aragonite samples precipitated at 25 °C, salinity = 35 in experiments which deconvolved the influences of pH, [CO32-], and [HCO3-] on aragonite precipitation rate16. We analyse a subset of the precipitations previously reported16 and supplement these with a small number of additional precipitations. The DIC conditions and aragonite precipitation rates of these experiments are summarised in Fig. 1a and b, respectively.

a solution conditions and b aragonite precipitation rates (R) in 25 °C experiments, and c solution conditions and d aragonite precipitation rates at variable temperature. Typical errors in pH. ΩAr, temperature within each precipitation is estimated to be 0.003 pH units, 0.04 to 0.16 ΩAr, and 0.04 °C, while the error in precipitation rate is estimated to be ~3% (see methods). In all cases, these errors are smaller than the symbols used.

Seawater and aragonite geochemistry are determined by ICP-OES and ICP-MS, respectively. Aragonite distribution coefficients are calculated as:

where Me/Ca and Li/Mg are measured in mol mol-1.

DMg/Ca, DLi/Ca, and DLi/Mg are significantly related to aragonite precipitation rate (Fig. 2a-c, Table 1, equations 3 to 5, respectively), and, thereby to ΩAr (Fig. 1b). DMg/Ca and DLi/Ca, are positively related to growth, as reported previously in aragonite17,18,19 and calcite20,21,22. DMg/Ca, DLi/Ca, and DLi/Mg show no dependence on seawater pH (Fig. 2a-c, equations 3 to 5 in Table 1). The incorporation of trace elements in CaCO3 and the CaCO3 crystallisation process itself are poorly understood23. CaCO3 trace element chemistry is influenced by the attachment/detachment rates of trace element ions to the mineral compared to the behaviour of host ions24, by the diffusion rates of ions through the mineral: fluid boundary2,3 and by the formation of precursor phases e.g. amorphous calcium carbonate25.

Relationships between DMg/Ca, DLi/Ca and DLi/Mg and aragonite precipitation rate (R) or ΩAr as a function of a–c pH at 25 °C, d–f variable temperature and g–i in the presence of amino acids at 25 °C. j–l Relationships between ΩAr and DMg/Ca, DLi/Ca, and DLi/Mg in the presence of amino acids. Best fit linear relationships are fitted to data at 10, 20, and 30 °C in d–f. No AA = no amino acid, Asp = aspartic acid, Glu = glutamic acid, Gly = glycine in g–l. Errors in DMg/Ca, DLi/Ca and DLi/Mg (1.4%, 2.6% and 3.1%, respectively), precipitation rate and ΩAr are smaller than the symbols used (see methods).

Solid-state diffusion in the newly formed mineral surface26 is likely to be too slow in carbonates to be significant at environmental temperatures24. In seawater, alkali and alkaline earth metals predominantly exist as hydrated cations27. Li+ may also complex with OH- or CO32- to form hydrated complexes28, the abundance of which is pH dependent29. Both Mg2+ and Li+ have smaller ionic radii that Ca2+ 30. Incorporation of Mg2+ in aragonite either occurs by substitution (for Ca2+) and relaxation of the lattice structure or by accommodation of nanodomains31. Li+ is incorporated in aragonite at adjacent substitutional and interstitial sites i.e., two Li+ ions occupy one Ca2+ site32. Although there is evidence of LiHCO3 incorporation in calcite21,22, we observe no effect of pH (Table 1) or fluid [HCO3-] (Fig. S2) on DLi/Ca to support this hypothesis in aragonite. Relatively large variations occur in DLi/Ca between different pH treatments at high aragonite growth rates (Fig. 2b) which warrant future investigation. However, fluid ΩAr in these fast growth rate experiments (ΩAr ≥17) is considerably higher than observed in the calcification media of tropical corals cultured at ambient [CO2] where ΩAr ≈ 1210, suggesting this observation is not relevant to marine calcifiers. DLi/Ca and DMg/Ca are «1 (Fig. 2a,b), indicating that both Li+ and Mg2+ are much less likely to be incorporated in the lattice than Ca2+.

Temperature influences on DMe/Ca and DLi/Mg

Secondly, we analyse aragonite synthesised over varying ΩAr and temperature (Fig. 1c), also at salinity = 35. Both ΩAr and temperature affect aragonite precipitation rate significantly (Fig. 1d, equation 6 in Table 1). These precipitations were conducted at ambient CO2 and we observe a broad positive relationship between seawater pH and ΩAr, over the sample suite (Fig. S1). As we have already determined that pH does not affect DMg/Ca, DLi/Ca, and DLi/Mg, we combine the data from these temperature precipitations with those reported in the previous section to analyse the effects of temperature and growth rate on DMg/Ca, DLi/Ca, and DLi/Mg.

DMg/Ca and DLi/Ca are significantly affected by both temperature and aragonite precipitation rate (Fig. 2d,e, equations 7 and 8 in Table 1), however DLi/Mg reflects precipitation rate only (Fig. 2f, equations 9 and 10 in Table 1). DLi/Mg is independent of temperature as DLi/Ca and DMg/Ca exhibit similar sensitivity to temperature but not to growth rate. As an example, increasing the temperature from 25 to 30°C increases DMg/Ca and DLi/Ca by 15 and 18%, respectively, at a log precipitation rate of 3.2. In contrast, increasing the log precipitation rate from 2.4 to 3.4 at 25 °C increases DMg/Ca by 180% and DLi/Ca by only 20%.

Although log precipitation rate and temperature generated similar trends in both DMg/Ca and DLi/Ca in previous aragonite precipitation studies17,19, DMg/Ca and DLi/Ca in the present study are considerably higher than in these previous reports (Fig. S3a, b). We observe an inverse relationship between precipitation rate and DLi/Mg, in contrast to the positive relationship reported by Brazier et al.17 (Fig. S3c). This previous study used simple solutions (270 mM NaCl, 25 mM MgCl2), with [Li] more than x500, that used in our experiments. This generated aragonite [Li] ~x100 higher17 than observed in the present study or in marine biominerals33. Trace element ions, which either substitute for Ca2+ in the CaCO3 lattice, or are hosted as interstitial ions between crystal lattice sites, create lattice distortions31,34 and the attachment/detachment of trace elements is influenced by the presence of other non-host ions on the crystal surface24,35. Further work is required to identify how aragonite [Li] influences further Li incorporation. However, we observe good agreement in DLi/Ca and DLi/Mg (Fig. 2e and f) between experiments conducted from 2 different batches of seawater with [Li] approximately equal to that of seawater or with [Li] approximately half of this (Table S1 and Table S2). This suggests that minor variations in seawater [Li] have a limited effect on Li partitioning in aragonite.

Amino acid effects on DMe/Ca and DLi/Mg

Finally, we analyse aragonite samples precipitated at 25°C over a range of pH and ΩAr (as in Fig. 1a) and in the presence of 2 mM of 3 amino acids (aspartic acid, glutamic acid and glycine), which are abundant in coral skeletons36,37,38 and mollusc shells39,40,41. Precipitation rates of these samples16, show that all amino acids inhibit aragonite precipitation, with aspartic acid and glycine the most and least effective inhibitors, respectively.

Aspartic and glutamic acids significantly increase DLi/Ca as a function of both precipitation rate and ΩAr (Fig. 2h, k, Table 2). Aspartic acid increases DMg/Ca as a function of precipitation rate but not ΩAr (Fig. 2g, j) and increases DLi/Mg as a function of ΩAr but not precipitation rate (Fig. 2i, l). Amino acids complex Mg2+ and Ca2+ in solution42 and create lattice distortions when incorporated into calcite43. Both processes could alter the relative rates of trace element and Ca2+ adsorption to the mineral surface. Although our study shows that amino acids influence the Li/Mg versus ΩAr relationship, we note that the seawater [amino acid] tested here (2 mM) far exceeds that likely to occur at organism calcification sites. Intra-crystalline [aspartic acid] is 0.5 to 1.5 nmol mg−1 in coral skeletons37 and ≤1 nmol mg−1 in mollusc shells44, but is >13 nmol mg-1 in synthetic aragonite precipitated under the conditions used here45. In vitro precipitations with 100 μM aspartic acid produce aragonite which has a comparable [aspartic acid] i.e., 0.8 nmol mg−145, to biominerals. Aragonite precipitation rates are reduced by ~12% by 100 μM aspartic acid46 and any influence of this on aragonite Li/Mg will be small (Fig. 2i).

Applications to biogenic aragonite

Although aragonite Li/Mg has been identified as a palaeothermometer47,48, our study shows that DLi/Mg is not significantly affected by temperature but is inversely related to aragonite precipitation rate. Aragonite precipitation rates in vitro reflect temperature and ΩAr2,13 (Fig. 1f) and the presence of biomolecules16,37,45,46. We consider that biomolecules are unlikely to significantly affect the precipitation rate versus aragonite Li/Mg relationship in marine calcifiers (Fig. 2i). We conclude that biogenic aragonite Li/Mg is a proxy for mineral precipitation rate. If the precipitation temperature is known i.e., in cultured organisms or those collected from known temperature environments, then aragonite Li/Mg can be used to reconstruct calcification media ΩAr.

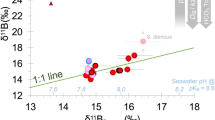

To demonstrate these applications, we utilise a composite dataset of Li/Mg in modern corals and the aragonitic foraminifera, Hoeglundina elegans, that were collected from known temperature environments, reproduced in Fig. 3a33. We rewrite equation 10 (Table 1) as:

a Reproduction of a composite Li/Mg dataset from aragonitic corals and foraminifera as a function of precipitation temperature33, b estimates of aragonite precipitation rates (R) from Li/Mg in the composite dataset for samples from temperatures 10 to 30 °C using Eq. 10, Table 1. Contours show aragonite precipitation rates observed in synthetic aragonite in this study (Eq. 6, Table 1), and the red dot indicates the measured ΩAr in the extracellular calcification media of the branching coral Stylophora pistillata, cultured at 25 °C10. Estimated ΩCM as a function of known environment temperature and published Li/Mg (using Eq. 10, Table 1) in c massive Porites spp., d other Symbiodinicaea hosting corals and e branching corals.

We calculate DLi/Mg from Li/Mgaragonite and Li/Mgcalcification media. We consider that Rayleigh fractionation, caused by changes in the relative proportions of different solutes in a fluid reservoir as precipitation occurs49, has no significant effect on calcification media Li/Mg, as DLi/Mg is very close to 1 (reflecting the similarity of DMg/Ca and DLi/Ca). We assume that calcification media Li/Mg is the same as seawater, i.e. 0.491 mmol mol−1 50. We use aragonite Li/Mg to calculate precipitation rates (Fig. 3b) from specimens that inhabited environments spanning from 10 to 30 °C (the temperature range studied in the synthetic aragonite experiments). We overlay the plot with contours of precipitation rates at variable ΩAr and temperature, calculated from our synthetic aragonite observations (equation 6, Table 1). The estimated biogenic precipitation rates are comparable to those observed in synthetic aragonites precipitated from seawaters with ΩAr of ~9 to 13 in organisms growing at 18 to 30 °C, and from seawaters with ΩAr of ~6 to 10 in organisms growing at <18 °C. Measurements of [CO32-], [Ca2+] and pH, in the extracellular calcification media of the branching coral Stylophora pistillata, cultured at 25 °C, yield ΩAr = 1210, which is in good agreement with our estimates of calcification media ΩAr based on Li/Mg resolved aragonite growth rates (Fig. 3b). This supports our contention that aragonite Li/Mg reflects aragonite growth rate and ΩAr, assuming that calcification media Li/Mg approximates that of seawater.

We rearrange equation 6 (Table 1) to:

and use Li/Mg estimates of log precipitation rates (R) combined with known precipitation temperature to reconstruct ΩCM in the specimens or sites with more than 2 analyses (Fig. 3c–e). Our analysis shows that ΩCM varies in massive Porites spp. corals47,51,52 and is higher in the specimen collected from SE Polynesia47 compared to the specimen from the NW Pacific47 at comparable temperatures (Fig. 3c). ΩCM also varies between other coral species48,51,53,54 and is considerably higher in a Siderastrea siderea coral collected from a fore reef environment compared to an analogue colony collected from the backreef at the same site (Fig. 3d). Both observations are consistent with changes in the ΩAr of the seawater sourced for the calcification media. Surface seawater ΩAr is higher in the tropical southeastern Pacific compared to the tropical northwestern Pacific55 and typically higher at the reef front compared to the backreef56. Although corals may upregulate the pH of the calcification media more under increased seawater pCO2 (low ΩAr), they do not attain the same media pH as observed in corals cultured under ambient CO2 conditions57 so they cannot completely offset the effects of low seawater ΩAr. Finally, ΩCM in Acropora spp. are relatively low compared to other branching coral species (Fig. 3e). Calcification in Acropora pulchra is less resilient to ocean acidification than in Pocillopora spp58. and the low ΩCM may contribute to this sensitivity.

This research explores element partitioning in aragonite precipitated from seawater-based solutions. Further work is required to identify if amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) occurs as a precursor phase during these experiments and to resolve how ACC transformation affects element partitioning. To broadly compare element partitioning between the synthetic aragonite samples produced here and biogenic aragonite, we calculate DMg/Ca, DLi/Ca and DLi/Mg for the Porites spp. coral skeletons illustrated in Fig. 3c. We use the skeletal Mg/Ca and Li/Mg data summarised in Williams et al33. and assume that calcification media [Mg], [Li] and [Ca] approximate that of seawater i.e. 52.7 mmol kg−1, 25.9 µmol kg−1 and 10.3 mmol kg−1 50. This yields coral skeletal DMg/Ca = 0.79 ± 0.08 × 10−3 (n = 38), DLi/Ca = 2.6 ± 0.2 × 10−3 (n = 38) and DLi/Mg = 3.1 ± 0.4 (n = 211). These values are comparable to the distribution coefficients observed in the synthetic aragonite precipitations reported here (Fig. 2), although we note that the synthetic experiments span a broad range of precipitation rates. We know of no independent estimates of aragonite precipitation rate in coral skeletons. Coral calcification rates are usually reported normalised to the surface area of the coral colony, but aragonite deposition occurs over the existing skeleton in contact with the coral tissue and this represents a much larger surface area59. Coral biomineralisation can also be measured as skeletal extension, but this is highly variable within individual skeletons60. At this time, a more detailed comparison of distribution coefficients between biogenic and synthetic aragonite is not possible.

Our study shows that aragonite Li/Mg is a robust indicator of aragonite growth rate. The Li/Mg paleothermometer relationship reported previously47,48 reflects the role of temperature in driving aragonite precipitation rate2 (and Fig. 1f). Aragonite Li/Mg offers great potential in reconstructing ΩCM in coral specimens when environmental temperature is known. The discovery of this proxy will better enable the identification of the response of marine calcifiers ΩCM to environmental changes, such as rising seawater temperature and/or pCO2.

Methods

2 sets of experiments were conducted using 3 batches of seawater. In the first set of experiments, aragonite was precipitated over variable pH and ΩAr at 25 °C, with and without amino acids (Table S1). These aragonite precipitation rates are published16. In the second set of experiments, aragonite was precipitated over variable temperature and ΩAr (Table S2). For full details of the apparatus and methods used, see Castillo-Alvarez et al., 202416. In all experiments synthetic aragonite was precipitated from artificial seawater50 with salinity 35. The seawater was bubbled with atmospheric air to reach equilibrium and then adjusted to the required DIC/pH conditions by the addition of 0.6 M Na2CO3 (to increase DIC) and by 2 M HCl or NaOH (to control pH). The reaction vessel was supplied either with an airstream with the [CO2] adjusted to be in equilibrium with the manipulated seawater i.e. either with atmospheric air or enriched or depleted in CO2 to give a composition in equilibrium with the treatment.

Seawater [DIC] was measured at the start and end of each experiment using a CO2 differential, non-dispersive, infrared gas analyser (Apollo SciTech; AS-C3) calibrated with a certified reference material (CRM 194, Scripps Institution of Oceanography). Seawater [DIC] error was calculated from the standard deviation of 3 to 8 replicate measurements of the sample and was 0.22% on average and always <0.7%. Between the start and end of the titration, seawater DIC varied by <5% over the first set of precipitations16 and by ~3%, on average, over the precipitations conducted at different temperatures (Table S2). ~200 mg of an aragonite seed was added to each titration to provide a surface for aragonite growth. For the experiments over variable pH, with and without amino acids, the seed was made from a coral skeleton16, while for the variable temperature experiments, the seed was a synthetic aragonite38. The coral and synthetic seed had Brunauer Emmett Teller technique surface areas of 4.27 ± 0.11 (n = 3) and 7.00 ± 0.20 (n = 3) m2 g−,1 respectively.

A Metrohm Titrando 902 pH stat titrator dosed equal volumes of 0.45 M CaCl2 and Na2CO3 to maintain constant pH (and Ω) in the reaction vessel during each titration. The pH of the reaction solution was monitored using a combined pH/temperature sensor (Metrohm Aquatrode PT1000). The sensor was calibrated weekly with fresh NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) buffers. pH was measured on the NBS (National Bureau of Standards) scale but was converted to the total scale for comparison to previous reports in the literature. pHtotal is 0.136–0.137 units lower than pHNBS over the pH range used here. pH drift between weeks was ≤0.003 pH units. Temperature was maintained by placing the reaction vessel in a water bath equipped with a chiller. The precipitating solution temperature was monitored at 5 s intervals within each titration using the combined pH/temperature sensor. Variations in temperature were small (±0.04 °C (1 s), on average and ±0.11°C (1 s) at most (Table S2). The titration finished when 300 mg of aragonite precipitated onto the seed and the final solid was collected by vacuum filtration onto a 0.2 μm polyether sulfone filter, rinsed with trace element grade ethanol, dried and stored in a desiccator. Each set of conditions were replicated 3 or 4 times and 1 to 3 of these replicates were analysed for geochemistry. Samples for solution [Li+], [Mg2+] and [Ca2+] were collected at the start and end of each of the titrations collected over different temperatures. For the remaining titrations, elements were measured for each batch of seawater, at the start of select experiments (to confirm that seawater Me/Ca was not significantly affected by the addition of reagents (e.g., HCl, NaOH or amino acids) and at the end of all precipitations. Aragonite precipitation rates were calculated by normalising the rate of titrant addition to the surface area of the seed. All precipitates were confirmed as aragonite by Raman spectroscopy46.

Solution and solid elements were determined using a Varian ICP-OES and an Agilent 7500ce ICP-MS, respectively at GEOMAR, accordingly to previous methods13. Seawater samples were analysed in 3 runs and details of the accuracy and precision of repeat analyses of IAPSO seawater are shown in Table S3. Procedural blanks, consisting of type 1 water filtered, stored and acidified as for seawater samples, had [Ca], [Mg] and [Li] of 0.013 mM, 0.18 mM and 0.00 μM, respectively, which, in each case, were <1 % of IAPSO seawater values. Between the start and end of each titration, seawater [Ca], [Mg] and [Li] decreased by 5, 3 and 2% respectively, on average and by 16% for all elements, at most. Mg/Ca, Li/Ca and Li/Mg changed by 3, 4 and 1% over a titration on average and by a maximum of 12, 14 and 2% respectively. The precipitates and seeds were analysed in 3 runs. The mean values for 2 reference materials, JCP-161 and NIST RM 830162, are presented in Table S4. The geochemistry of the synthetic aragonite formed in the precipitations was calculated by correcting for the seed composition, assuming the seed comprised 40% of the total solid mass.

Solution [CO32-] was calculated from measurements of [DIC] and pH at the start and end of each titration using CO2SYS v263 with the equilibrium constants for carbonic acid64 and KHSO465 and using [B] seawater66. Solution ΩAr was calculated from [CO32-] and [Ca2+] coupled with the solubility product (Ksp) of aragonite at 1 atmosphere and the precipitation temperature67.

We use multiple linear regression analysis to identify significant influences on DMg/Ca, DLi/Ca and DLi/Mg and one-way ANCOVA to test for equality of means and equality of slopes in the DMe/Me versus log precipitation rate or ΩAr relationships between experiments conducted with and without amino acid. To identify the origin of significant differences, we conducted individual ANCOVA tests between each amino acid and the control, applying a Bonferroni correction to avoid type 1 errors. We undertook 6 ANCOVA tests (3 amino acids versus the controls for precipitation rate and ΩAr) and we calculated an adjusted α value of 0.020 (i.e., the original α value, 0.05, divided by the square root of the total number of tests). We conclude that relationships are significantly different in mean (after adjusting for rate or ΩAr) or slope if p ≤ 0.02.

Details of experiment conditions, seawater chemistry, aragonite chemistry and calculated distribution coefficients are in Table S1 (variable pH experiments with and without amino acids) and Table S2 (variable temperature experiments). Equations describing DMe/Me as a function of aragonite growth rate and pH in precipitations conducted at 25 °C in the presence of 2 mM aspartic acid, glutamic acid or glycine are summarised in Table S5.

Estimating experimental errors

We considered the errors likely to influence our experiments. In the titrations, pH uncertainty is estimated from the maximum drift in sensor pH observed over a week (as ±0.003 units). Temperature error reflects the average temperature variation (1 s) within each precipitation (±0.04 °C). ΩAr error for each precipitation is estimated by compounding the effects of errors in measurement of [DIC], [Ca2+], pH and temperature on ΩAr.

The pH error of 0.003 affects estimated [CO32-], and thereby ΩAr, by 0.6%. The average error in individual [DIC] measurements (0.22%) affects estimated [CO32-], and thereby ΩAr, by 0.22%. The average error in seawater [Ca2+] measurement (0.3%, Table S3) affects ΩAr, by 0.3%. A temperature change of 0.04°C influences the CO2 acidity constants (K*1 and K*2), used to calculate [CO32-], by ~0.08% and 0.15% respectively64, in combination generating a variation in [CO32-], and thereby ΩAr, of ~0.15%. Temperature changes of 0.04 °C influence the aragonite solubility product (Ksp) used to calculate ΩAr by <0.02%67 and we consider this effect to be insignificant.

We calculate the ΩAr error for each precipitation by compounding the errors in [DIC] and [Ca2+] at the start and end of each titration with the pH drift error (0.6%) and the impact of changes in CO2 acidity constants (0.15%) as:

This is equivalent to an error in ΩAr of ~0.04 at ΩAr = 5 and of ~0.16 at ΩAr = 20.

Precipitation rate is estimated by normalising the rate of titrant addition to the surface area of the seed. Replicate BET measurements of the ground coral seed used for experiments over variable pH, with and without amino acids, yield a surface area error of 2.6% (1 s13). Replicating BET measurements of the synthetic aragonite seed used for experiments conducted at different temperatures yields a surface area error of 2.9% (1 s). The mass of the starting seed was 200 ± 1 mg (an error of 0.5%). Compounding errors in seed mass and surface area yields an error in the estimated aragonite precipitation rate of ≤2.9%.

In calculating DMe/Me, aragonite Me/Me is calculated by assuming that the aragonite is composed of 60% synthetic aragonite deposited during the titration and 40% seed. For the experiments over variable pH with and without amino acids, the seed was made from a coral skeleton, while for the variable temperature experiments, the seed was a synthetic aragonite. Typical errors in measurement (1 s) of aragonite Mg/Ca, Li/Ca and Li/Mg are ±0.060 mmol mol−1, ±0.12 µmol mol−1 and ±0.026 mmol mol−1, respectively, based on repeat analysis of reference materials (Table S4), equivalent to 1.5%, 2.2% and 1.8%. The mass of the starting seed was 200 ± 1 mg (an error of 0.5% which we consider insignificant). Repeat analyses of replicate samples of the coral skeleton seed yield errors (1 s) in Mg/Ca, Li/Ca and Li/Mg of 0.0064 mmol mol−1, 0.11 µmol mol−1 and 0.023 mmol mol−1 respectively (Table S1). Repeat analyses of the synthetic seed yield errors (1 s) in Mg/Ca, Li/Ca and Li/Mg of 0.097 mmol mol−1, 0.12 µmol mol−1 and 0.060 mmol mol−1 respectively (Table S2). The seed contributes 40% of the mass of the solid collected at the end of the precipitation so variations in seed geochemistry of this magnitude could influence the final Me/Me by 40% of these values. Assuming that errors are random we estimate a total error for aragonite Mg/Ca of 0.072 mmol mol−1 by compounding the precision of Mg/Ca of the solid (±0.060 mmol mol−1) with the error associated with variation in Mg/Ca of the starting seed (up to ±0.039 mmol mol−1). Similarly, we estimate errors for aragonite Li/Ca and Li/Mg of 0.13 µmol mol−1 and 0.035 mmol mol−1 respectively. These are equivalent to total error in aragonite Mg/Ca, Li/Ca and Li/Mg of ~1.4%, 2.4% and 3.0%, at the synthetic aragonite concentrtaions observed here (i.e., Mg/Ca, Li/Ca and Li/Mg of ~5 mmol mol-1, ~5.5 µmol mol−1 and ~ 1.2 mmol mol−1 respectively, Tables S4 and S5).

Typical errors in measurement (1 s) of seawater Mg/Ca, Li/Ca and Li/Mg are <0.016 mol mol−1, <0.025 mmol mol−1 and <0.050 mmol mol−1 or 0.3%, 1.0% and 1.0%, respectively. Compounding errors in seawater and aragonite Me/Me yields error on DMg/Ca, DLi/Ca and DLi/Mg of 1.4%, 2.6% and 3.1%.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Details of experiment conditions, seawater chemistry, aragonite chemistry and calculated distribution coefficients for this study are available in “Aragonite Li/Mg as an indicator of calcification media saturation state in marine calcifiers”, Mendeley Data, https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/3dfzkxy7zm/1.

References

van Cappellen, P., Biomineralization and Global Biogeochemical Cycles. Rev. Min. Geochem. 54 https://doi.org/10.2113/0540357 (2003).

Burton, E. A. & Walter, L. The effects of pCO2 and temperature on Mg incorporation in calcite in seawater and MgCl2-CaCl2 solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 55, 777–785 (1991).

Morse, J. W., Arvidson, R. S. & Lüttge, A. Calcium carbonate formation and dissolution. Chem. Rev. 107, 342–381 (2007).

Bentov, S., Brownlee, C. & Erez, J. The role of seawater endocytosis in the biomineralization process in calcareous foraminifera. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21500–21504 (2009).

Mass, T. et al. Amorphous calcium carbonate particles form coral skeletons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E7670–E7678 (2017).

Sun, C. Y. et al. From particle attachment to space-filling coral skeletons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 30159–30170 (2020).

Venn, A. A. et al. Imaging intracellular pH in a reef coral and symbiotic anemone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 16574 (2009).

Tambutté, E. et al. Calcein labelling and electrophysiology: insights on coral tissue permeability and calcification. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 279, 19–27 (2012).

de Nooijer, L. J., Toyofuku, T. & Kitazato, H. Foraminifera promote calcification by elevating their intracellular pH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15374–15378 (2009).

Sevilgen, D. S. et al. Full in vivo characterization of carbonate chemistry at the site of calcification in corals. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau7447 (2019).

Allison, N., Cohen, I., Finch, A. A., Erez, J. & Tudhope, A. W. Corals concentrate dissolved inorganic carbon to facilitate calcification. Nat. Comm. 5, 5741 (2014).

Rollion-Bard, C., Chaussidon, M. & France-Lanord, C. pH control on oxygen isotopic composition of symbiotic corals. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 215, 275–288 (2003).

Alvarez, C. C. et al. B(OH)4− and CO32− do not compete for incorporation into aragonite in synthetic precipitations at pHtotal 8.20 and 8.41 but do compete at pHtotal 8.59. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 379, 39–52 (2024).

Allison, N. et al. A comparison of SNARF-1 and skeletal δ11B estimates of calcification media pH in tropical coral. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 355, 184–194 (2023).

Falini, G., Fermani, S. & Goffredo, S. Coral biomineralization: A focus on intra-skeletal organic matrix and calcification. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 46, 17–26 (2014).

Castillo Alvarez, M. C. et al. Insights into the response of coral biomineralisation to environmental change from aragonite precipitations in vitro. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2023.10.032 (2024).

Brazier, J. M., Harrison, A. L., Rollion-Bard, C. & Mavromatis, V. Controls of temperature and mineral growth rate on lithium and sodium incorporation in abiotic aragonite. Chem. Geol. 654, 122057 (2024).

Gabitov R. I. et al. In situ δ7Li, Li/Ca, and Mg/Ca analyses of synthetic aragonites. Geochem. Geophy. Geosyst. 12, Q03001 (2013).

Mavromatis, V., Brazier, J. M. & Goetschl, K. E. Controls of temperature and mineral growth rate on Mg incorporation in aragonite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 317, 53–64 (2022).

Mavromatis et al., Kinetics of Mg partition and Mg stable isotope fractionation during its incorporation in calcite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2013.03.024 (2013).

Füger, A., Konrad, F., Leis, A., Dietzel, M. & Mavromatis, V. Effect of growth rate and pH on lithium incorporation in calcite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 248, 14–24 (2019).

Branson, O., Uchikawa, J., Bohlin, M. S. & Misra, S. Controls on Li partitioning and isotopic fractionation in inorganic calcite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 382, 91–102 (2024).

Branson, O. Boron incorporation into marine CaCO3. In Boron Isotopes: The Fifth Element, pp. 71–105. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2018).

DePaolo, D. J. Surface kinetic model for isotopic and trace element fractionation during precipitation of calcite from aqueous solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 1039–1056 (2011).

Evans, D. et al. Trace and major element incorporation into amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) precipitated from seawater. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 290, 293–311 (2020).

Watson, E. A conceptual model for near-surface kinetic controls on the trace-element and stable isotope composition of abiogenic calcite crystals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 68, 1473–1488 (2004).

Chester, R. Marine geochemistry. John Wiley & Sons (2009).

Moskovits, M. & Michaelian, K. H. Alkali hydroxide ion pairs. A Raman study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 2209–2215 (1980).

Millero, F. J., Woosley, R., DiTrolio, B. & Waters, J. Effect of ocean acidification on the speciation of metals in seawater. Oceanography 22, 72–85 (2009).

Shannon, R. D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Cryst. A 32, 751–767 (1976).

Finch, A. A. & Allison, N. Coordination of Sr and Mg in calcite and aragonite. Min. Mag. 71, 539–552 (2007).

Zhadan, A., Montouillout, V., Aufort, J., Mavromatis, V. & Balan, E. High-resolution solid-state 7Li NMR study of lithium incorporation in calcite and aragonite. Chem. Geol. 122842 (2025).

Williams, T. J. et al. A global database of measured values of Li/Mg, Mg/Ca, Sr/Ca, Ba/Ca, U/Ca and Sr-U for coral and coralline algae paleoenvironment calibrations [dataset bundled publication]. PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.962897 (2023).

Meldrum, F. C. Calcium carbonate in biomineralisation and biomimetic chemistry. Int. Mater. Rev. 48, 187–224 (2003).

Henehan, M. J. et al. No ion is an island: Multiple ions influence boron incorporation into CaCO3. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 318, 510–530 (2022).

Cuif, J.-P., Dauphin, Y. & Gautret, P. Compositional diversity of soluble mineralizing matrices in some recent coral skeletons compared to fine-scale growth structures of fibres: discussion of consequences for biomineralization and diagenesis. Int. J. Earth Sci. 88, 582–592 (1999).

Kellock, C. et al. The role of aspartic acid in reducing coral calcification under ocean acidification conditions. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–6 (2020).

Allison, N. et al. The influence of seawater pCO2 and temperature on the amino acid composition and aragonite CO3 disorder of coral skeletons. Coral Reefs 43, 1317–1329 (2024).

Weiner, S. Aspartic acid-rich proteins: major components of the soluble organic matrix of mollusk shells. Calcif. Tissue Int. 29, 163–167 (1979).

Bédouet, L. et al. Soluble proteins of the nacre of the giant oyster pinctada maxima and of the abalone Haliotis tuberculata. extraction and partial analysis of nacre proteins. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 128, 389–400 (2001).

Suzuki, M. et al. An acidic matrix protein, Pif, is a key macromolecule for nacre formation. Science 325, 1388–1390 (2009).

De Stefano, C., Foti, C., Gianguzza, A., Rigano, C. & Sammartano, S. Chemical speciation of amino acids in electrolyte solutions containing major components of natural fluids. Chem. Speciat. Bioavailab. 7, 1–8 (1995).

Kim, Y. Y. et al. Tuning hardness in calcite by incorporation of amino acids. Nat. Mater. 15, 903–910 (2016).

Penkman, K. E. H., Kaufman, D. S., Maddy, D. & Collins, M. J. Closed-system behaviour of the intra-crystalline fraction of amino acids in mollusc shells. Quat. Geochronol. 3, 2–25 (2008).

Gardella, G. et al. Contrasting the effects of aspartic acid and glycine in free amino acid and peptide form on the growth rate, morphology, composition and structure of synthetic aragonites. Cryst. Growth Des. 24, 9379–9390 (2024).

Kellock, C. et al. Optimising a method for aragonite precipitation in simulated biogenic calcification media. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278627 (2022).

Hathorne, E. C., Felis, T., Suzuki, A., Kawahata, H. & Cabioch, G. Lithium in the aragonite skeletons of massive Porites corals: A new tool to reconstruct tropical sea surface temperatures. Paleoceanography 28, 143–152 (2013).

Montagna, P. et al. Li/Mg systematics in scleractinian corals: Calibration of the thermometer. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 132, 288–310 (2014).

Elderfield, H., Bertram, C. J. & Erez, J. A biomineralization model for the incorporation of trace elements into foraminiferal calcium carbonate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 142, 409–423 (1996).

Millero, F. J. Chemical Oceanography, 4th ed. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL (2013).

Cuny-Guirriec, K. et al. Coral Li/Mg thermometry: caveats and constraints. Chem. Geol. 523, 162–178 (2019).

Clarke, H., D’Olivo, J. P., Conde, M., Evans, R. D. & McCulloch, M. T. Coral records of variable stress impacts and possible acclimatization to recent marine heat wave events on the northwest shelf of Australia. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclim. 34, 1672–1688 (2019).

Fowell, S. E. et al. Intrareef variations in Li/Mg and Sr/Ca sea surface temperature proxies in the Caribbean reef-building coral Siderastrea siderea. Paleoceanography 31, 1315–1329 (2016).

Ross, C. L., DeCarlo, T. M. & McCulloch, M. T. Calibration of Sr/Ca, Li/Mg and Sr-U paleothermometry in branching and foliose corals. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclim. 34, 1271–1291 (2019).

Feely, R. A. et al. Decadal changes in the aragonite and calcite saturation state of the Pacific Ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26, GB3001 (2012).

Falter, J. L., Lowe, R. J., Zhang, Z. & McCulloch, M. Physical and biological controls on the carbonate chemistry of coral reef waters: effects of metabolism, wave forcing, sea level, and geomorphology. PloS One 8, e53303 (2013).

Venn, A. A. et al. Impact of seawater acidification on pH at the tissue–skeleton interface and calcification in reef corals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110, 1634–1639 (2013).

Comeau, S., Edmunds, P. J., Spindel, N. B. & Carpenter, R. C. Fast coral reef calcifiers are more sensitive to ocean acidification in short-term laboratory incubations. Limnol. Oceanogr. 59, 1081–1091 (2014).

Barnes, D. J., Taylor, R. B. & Lough, J. M. On the inclusion of trace materials into massive coral skeletons. Part II: Distortions in skeletal records of annual climate cycles due to growth processes. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 194, 251–275 (1995).

Brahmi, C. et al. Pulsed 86Sr-labeling and NanoSIMS imaging to study coral biomineralization at ultra-structural length scales. Coral Reefs 31, 741–752 (2012).

Hathorne, E. C. et al. Interlaboratory study for coral Sr/Ca and other element/Ca ratio measurements. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 14, 3730–3750 (2013).

Stewart, J. A. et al. NIST RM 8301 boron isotopes in marine carbonate (simulated coral and foraminifera solutions): inter-laboratory δ11B and trace element ratio value assignment. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 45, 77–96 (2021).

Pierrot, D., Lewis, E. D. & Wallace, W. R. MS Excel Program Developed for CO2 System Calculations, Oak Ridge National Laboratory (2006).

Lueker, T. J., Dickson, A. G. & Keeling, C. D. Ocean pCO2 Calculated from Dissolved Inorganic Carbon, Alkalinity, and Equations for K1 and K2: Validation Based on Laboratory Measurements of CO2 in Gas and Seawater at Equilibrium. Mar. Chem. 70, 105–119 (2000).

Dickson, A. G. Standard Potential of the Reaction: AgCl(s) + 12H2(g) = Ag(s) + HCl(aq), and the Standard Acidity Constant Of The Ion HSO4− in Synthetic Sea Water from 273.15 to 318.15 K. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 22, 113–127 (1999).

Lee, K. et al. The universal ratio of boron to chlorinity for the North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 74, 1801–1811 (2010).

Mucci, A. The solubility of calcite and aragonite in seawater at various salinities, temperatures, and one atmosphere total pressure. Am. J. Sci. 283, 780–799 (1983).

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NE/S001417/1). Raman analyses were supported by the EPSRC Light Element Analysis Facility Grant EP/T019298/1 and EPSRC Strategic Equipment Resource Grant EP/R023751/1 at the University of St. Andrews.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A., A.F., K.P., R.K. and M.C. designed the study. C.C.A., N.A. and E.H. conducted the study. N.A. and C.C.A. wrote the initial draft of the paper and all authors contributed to the interpretation and final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alice Drinkwater. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Castillo Alvarez, C., Hathorne, E., Clog, M. et al. Aragonite lithium/magnesium as an indicator of calcification media saturation state in marine calcifiers. Commun Earth Environ 6, 984 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02945-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02945-3