Abstract

Many subsurface processes involve transitions in granular material states, from arrested to creeping to flowing. Experiments and frameworks for idealized systems reveal that granular fabrics develop during shearing, co-evolve with applied stress, and govern such transitions. We use microtomography to test whether fabrics at two San Andreas fault sites reflect slip history and whether idealized frameworks extend to nature. Near-surface sediments within the fault zone transition between deformation patterns over the seismic cycle, including bulk/localized grain re-arrangements, individual grain fracturing, and localized zones of fracturing. Aseismic and co-seismic shearing produce distinct preferred grain orientations. Co-seismic fabrics can be preserved after centuries of aseismic strain, aseismic fabrics may be overprinted, and grain size and coordination number influence the fabrics. Idealized frameworks, namely anisotropic critical state theory, frictional jamming, and material memory, can explain our observations, and fault zone sediments likely undergo cycles of memory creation and erasure that influence rigidity spatiotemporally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sediments cover ~50% of Earth’s land surface area1. These granular Earth materials mostly exist in jammed solid-like states that support non-zero shear stresses induced by natural and anthropogenic forcings2,3,4,5. Sediments locally yield under everyday background forcings smaller than their bulk critical yield strengths2,4. These sub-critical yielding processes, which include creep and compaction, are marked by local grain re-arrangements within fragile sub-volumes in sediments2,6. Creep and compaction transform Earth’s surface geomorphology and evolve the porosity, permeability, and shear strength of buried sediments over diurnal to millennial timescales2,7,8. Prolonged creep and/or large external stresses can induce global unjamming, whereby the entire material fails, transitioning from a solid-like to a fluid-like state9,10,11,12. Global unjamming can lead to several geohazards [e.g., landslides, dam collapses, liquefaction, and lateral spreading] that cause loss of life and damage infrastructure. Understanding what controls if, when, and how global unjamming occurs in natural sediments remains a scientific challenge with societal relevance.

Decades of lab and theoretical research suggest that unjamming in granular materials directly relates to how shearing induces strains on the granular fabric13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. When sediments shear, finite volumetric strain causes dilatation or contraction, and the microstructural fabric inherited from deposition and diagenesis controls deformational response13,14,15,16,17,18. The inherited depositional fabric evolves throughout shear deformation, and can be quantified and tracked as it approaches the critical state, where the scalar anisotropy value is unity21,22. In the absence of finite volumetric strain, jammed frictional granular packings still develop anisotropic fabrics if sheared from an initially unjammed isotropic state23,24,25,26,27. These shear-jammed and fragile fabrics are characterized by whether the distribution of contact forces or contact normals leads to directional dependence on the fabric’s ability to resist deformation24,25,26,27,28, and are considered examples of material memory related to past forcings26,27,28,29,30,31. Observations from these existing lab and simulation studies have been used to develop the frictional jamming framework and anisotropic critical state theory [ACST], which respectively describe the volume-preserving and non-volume-preserving shearing scenarios24,25,26,27,28,30.

Two-dimensional microstructural analyses of sediments sheared by faults suggest that the fabric of granular Earth materials also encodes information about past forcings. Studies document differences in [1] preferred grain orientations [i.e., a fabric] and [2] the amount of grain breakage as a function of co-seismic versus aseismic forcings32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Grains within co-seismically sheared sediments have stronger preferred grain orientations oblique to the fault than grains within aseismically sheared sediments37. Comminution was not evident in sediments sheared during aseismic forcings, but was extensive during co-seismic forcings37. These findings qualitatively suggest that, despite increased disorder, naturally sheared sediments exhibit some of the deformation features described by the existing lab-derived frameworks and theories.

Our study quantitatively examines three-dimensional fabrics and jamming phenomena in tectonically sheared granular sediments. We hypothesize that shallow fault zones impart sufficient shear strain to produce jammed rigid states with distinct fabrics in natural sediments. We anticipate that the distinct fabrics relate to the history of the sediments and, hence, represent a form of material memory. We test our hypotheses at two study sites, Pallett Creek and Ferrum, within the southern San Andreas fault [SAF], California, where exposures of layers of interbedded silt, sand, and gravel show no visible field-scale evidence of anisotropic grain fabric [Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1]. We examine samples that have been sheared co-seismically only, co-seismically with subsequent aseismic slip, and aseismically only [Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1]. We use 40 mm long by 10 mm diameter aluminum tubes to collect 19 samples from depths <4 m, and obtain three-dimensional images with X-ray microtomography [XRCT] [Figs. 2 and 3]. Our sampling method preserves grain positions in the inner ~90% of the sampling tube40,41, and our reported grain property results rely on analyses from six samples that capture ~76,000 grains. Our analyses indicate that comminution occurs in both co-seismically and aseismically sheared sediments, and the magnitude and/or rate of cumulative tectonic strain imparts differences in the microstructural fabric of shallow subsurface sediments that distinguish past geological forcings. Aseismic slip evolves the depositional fabric, creating a memory that can be erased and overprinted by co-seismic slip. Tectonically induced deformation and memory can be preserved for at least three centuries, and grain fracturing along a fault strand produces a rigid granular fabric. We discuss our findings in the context of the frictional jamming framework and ACST.

a Location of study sites along the San Andreas fault [SAF] [red line]. Thin gray lines show other faults. b A regional lidar hillshade map of the Pallett Creek sites within [Main PC site] and outside [P_OFZ control samples] the fault zone [blue stars] and c the geologic interpretations showing sedimentary units [layer shading], fault strands, and sample locations [blue circles] from the exposure at the main Pallett Creek site and d at the Ferrum north-facing trench wall modified from Rockwell et al.47. We collect F_C_6.9 from the south-facing trench wall but show its relative location on the north-facing wall for illustrative purposes [see Supplementary Fig. 1].

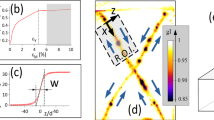

Samples (a–c) have experienced aseismic slip only, d–f co-seismic slip from one earthquake ≥Mw6 and subsequent aseismic slip, and g–i co-seismic slip from seven earthquakes ≥Mw6. The images highlight deformation features magnified in (j–o). The four digits after the sample name correspond to the slice number at the top of each rendered image.

(Top) Number of completely fractured [filled bars] and partially fractured [open bars] grains. “Locked samples” (blue) are from Pallett Creek, “Creeping samples” (orange) are from Ferrum, and “Control samples” include aseismic samples from Ferrum and no co-seismic slip from Pallett Creek inside the fault zone, and samples outside the fault zone at Pallett Creek [~650 m away]. Each bar provides counts for a single sample. EQ earthquakes, FZ fault zone. (Bottom) Check mark indicates grain deformation observed.

Geologic setting

The Pallett Creek site [34.4557°N, 117.8872°W] offers a location where ground-rupturing earthquakes greater than moment magnitude Mw 6 have repeatedly faulted, folded, and sheared the macroscopic deformation zone that extends ~15 m surrounding the main fault strand42,43,44,45,46. We focus on an exposure where fluvial sediments are offset by a single fault strand and analyze samples from layers that have experienced seven, five, and no earthquakes [Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1]. Two additional control samples are from 4 m depth at an exposure ~650 m from the main fault trace [34.4536°N, 117.8978°W] [Fig. 1]. There are no documented aseismic slip events on the SAF near Pallett Creek.

The Ferrum samples are from a trench [33.4587°N, 115.8559°W] located within a ~50 m wide releasing step-over along an otherwise relatively straight portion of the SAF47,48 [Figs. 1 and 3]. The trench exposes an aeolian dune complex, sandy lacustrine deposits, and a wide fracture and fault zone [Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 3]. The main fault strand folded, offset, and sheared the lacustrine deposits during a ~Mw 7.2 large ground rupturing earthquake circa [ca.] 172647,49,50. This section of the SAF also undergoes repeated aseismic creep events, documented in satellite imagery and creep meter data51,52.

At Ferrum, we sample along the fault strand, a dune deposit that has experienced aseismic slip only, and lacustrine deposits that have experienced co-seismic slip and aseismic slip [Fig. 1]. We use the term “aseismic” to refer to samples sheared only by aseismic slip and “co-seismic” to refer to all samples sheared by at least one ≥Mw 6 earthquake. The “control” samples include both the distal samples from Pallett Creek and no co-seismic slip samples. Our sample naming convention reflects the study site [F for Ferrum; P for Pallett Creek; OFZ for outside the fault zone], fault slip history [C for co-seismic; A for aseismic; noEQ for no earthquake], and the horizontal distance of the sample from the main fault strand [in meters]. For example, sample “F_A_2.7” is a Ferrum aseismic sample collected 2.7 m from the main fault strand [Fig. 1], whereas P_OFZ_650 and P_noEQ_1.2 are “control” samples.

Direct observation of recent earthquakes paired with seismological models provides general constraints on the relative shear strain and stresses experienced by the near-surface sediments. Earthquake slip rates within low cohesion fault zone materials, such as those we sampled, are orders of magnitude greater for co-seismic [km/s] than slow slip events [km/day] or long-term creep [mm/yr]51,53,54,55. Peak ground motions in the near field vary similarly, with faster velocities [cm/s] expected from pulse-type co-seismic events characteristic of large ruptures and slower velocities [mm/s] from aseismic and triggered slip events56. Ground motion velocities for a recent triggered event near the Ferrum site were up to 5 mm/s51. Accordingly, damage from large accelerations and dynamic shear stresses is expected to be significantly larger for co-seismic events, where near-field measurements of 0.3 to over 1 g are expected57,58.

Results

We observe distinct grain orientation and fracturing patterns between most co-seismic and aseismic samples. Distributed fault damage, segregation, deformation bands, and in situ grain fracturing exist in both sample types but are scarce in the control samples. Our observations lead us to conclude that tectonic slip is the main driver of sediment deformation at both sites.

Deformation bands, distributed damage, and segregation

Co-seismic and aseismic samples contain ~0.12–2.6 mm long deformation bands, defined as relatively narrow, elongated zones characterized by apparently higher volume fraction of smaller fractured grains59. These deformation bands are planar, a few grain diameters wide, and oriented sub-parallel to bedding. The termini of some deformation bands are adjacent to sub-volumes comprising relatively larger grains. The existence and geometries of the deformation bands suggest that the sediments’ pre-shear states—that is, the geometric relationships between grains and pores after deposition but before tectonic-induced shearing—have been modified.

Six otherwise sand-rich co-seismic samples at Pallett Creek contain concentrated sub-volumes of fines [Fig. 3]. The sub-volumes of fines in samples P_C_0.14, P_C_0.85, P_C_0.1, and P_C_0.2 have an irregular boundary shape with a sub-vertical contact plane that separates them from the sands [see Fig. 2g]. The sub-vertical contact implies these features are unrelated to bedding, which we expect would cause a sub-horizontal contact plane. The fines extend the length of the sample tube [>40 mm] into the outcrop wall and are within 0.85 m of a fault strand with at least one earthquake since the sediments were deposited [Figs. 1c and 3]. These volumes of fines are consistent with distributed damage during co-seismic slip33,36,37,38. Two samples, P_C_0.2 and P_C_0.3, close to the fault strand contain relatively narrow, planar, and irregular volumes of fines [Figs. 1c and 3]. In sample P_C_0.2, the fines extend the length of the sample tube [>40 mm] while in P_C_0.3 they form an “L shape” near a relatively large grain, having both sub-horizontal and sub-vertical components [Fig. 2i].

Two co-seismic samples at Ferrum, F_C_0 and F_C_6.5, contain sub-volumes of finer sand separated from coarser sands. One sample is along the fault strand [F_C_0; Fig. 1d]. The other is 6.5 m from the fault strand [F_C_6.5; Fig. 1d]. The finer sand volume in sample F_C_6.5 extends the length of the sample tube [>40 mm] and orients vertically, indicating that they are unrelated to bedding [Fig. 2e]. Instead, we interpret that they record shear-induced grain size segregation often seen in granular experiments, granular earth flows, and industrial settings60,61,62. Segregation further supports the idea that shearing-induced grain re-arrangement has occurred at Ferrum. Importantly, distributed fault damage, deformation bands, and segregation are absent from the Pallett Creek control samples, and Ferrum aseismic samples do not show evidence of grain size segregation or comminuted volumes of fines.

Grain fracturing

We observe in situ grain chipping, splitting, and fragmentation in all co-seismic and some aseismic slip samples [Figs. 2 and 3]. No completely fractured and <5 partially fractured grains exist in the Pallett Creek control samples and the aseismic slip samples at Ferrum [Fig. 3]. The number of ground-rupturing earthquakes positively correlates with the number of completely and partially fractured grains [Fig. 3]. We only observe cushioning in samples that have experienced seven ground-rupturing earthquakes. A good example is sample P_C_0.3, which hosts two large [>600 μm] fractured grains cushioned by smaller [<200 μm] grains [Fig. 2V–VI]. Analysis of grain sphericity and convexity [Supplementary Fig. 3] supports the conclusion that grain fracturing occurred by at least the chipping mode of breakage63. Regardless of the mode of breakage, local grain re-arrangements must have preceded grain fracturing since the latter requires higher energies64,65. The increase in grain damage with the number of earthquakes indicates that tectonic shearing is the primary cause of deformation within the samples.

Grain fabric

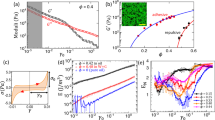

Analyses of ~76,000 grains within six segmentable samples reveal distinct fabrics in aseismic versus co-seismic slip samples. The fabrics are identifiable as dense clusters on Lambert azimuthal equal-area projection plots [see red-pink zones in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 3 for isotropic orientations]. We further fit a von Mises-Fisher probability distribution [\(f({{\boldsymbol{x}}};{{\boldsymbol{\mu }}},\kappa )\propto {e}^{\kappa {{{\boldsymbol{\mu }}}}^{T}{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}\)] to the orientation unit vectors x and perform a χ2 test to assess the statistical significance of the results. The parameters μazi,inc are the mean direction vector with azimuthal and inclinational components, and κ represents a direction vector’s concentration. Uniformly distributed directional data have undefined μazi and κ = 0. The grains generally incline close to horizontal [μinc = 61–89°] with the exception of sample F_C_6.9, where grains incline closer to vertical [μinc = 15]. Though the vertically inclined grains are thought to be geologically uncommon, we consider this result to be robust since we collected, handled, processed, and imaged all samples similarly and have no other independent evidence to suggest that the orientations in this sample are not a result of natural processes at Ferrum. The 95% confidence cone for μ spans 0.5–2.0°, indicating that uncertainties in μazi and μinc are likely small, though they cannot be separated because the uncertainty is defined jointly on the sphere. Hereafter, we focus on μazi because it captures the dominant directional trends within the samples. The grains in both aseismic samples [F_A_2.5/2.7] and one co-seismic sample [F_C_6.9] orient within geographic northeast and southwest [NE-SW] quadrants at all inclinations on Lambert’s plots [Fig. 4d–f and Supplementary Fig. 4]. Conversely, the grains in the other co-seismic samples [F_C_0/6.5] do not show distinct azimuthal orientations at all inclinations. Instead, they show distinct inclinations less than 45° from horizontal at all azimuths [Fig. 4a–c]. The μazi for all Ferrum samples is within 10–69° of the local fault strike [315°] [Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4; Supplementary Table 1]. At Pallett Creek, μazi is 20° greater than the local fault strike [295°]. The range of κ [1.8–1.9] indicates a preferred long-axis orientation. The supplement contains a video [Supplementary Movie 3] showing the centroids of preferentially oriented grains, highlighting that their orientations are not due to shear deformation localized to sub-volumes within the packing.

Samples sheared during a co-seismic slip at the Pallett Creek exposure 0.3 m from a fault strand, b co-seismic slip at Ferrum 6.5 m from a fault strand, c directly on a fault strand active during co-seismic slip at Ferrum, d co-seismic slip at Ferrum 6.9 m from a fault strand, e, f aseismic slip at Ferrum 2.7 and 2.5 m from a fault strand. The radial direction within the plots shows inclination [center is vertical and perimeter is horizontal]. The big Lambert plots represent all grains. The small Lambert plots represent rattlers [Z < 4] and non-rattlers [Z ≥ 4]. The gray arrow represents the strike of the San Andreas fault at each study site. The angular bin width decreases with higher inclinational rings, from 90° per bin in the first ring [0–15°] to ~8° per bin in the last ring [75–90°].

Standardized scalar measures of fabric anisotropy based on the grain long-axes Fg, and contact normals Fc, also indicate preferred orientations in our samples. Hostun sand is a popular geotechnical engineering reference granular material that achieves Fg ≈ 1.2, Fc ≈ 0.90 at large axial strains [>12%] corresponding to their critical state66. The Fg values for all samples except the co-seismic sample F_C_6.5 are consistent with low [28th percentile] to moderate [54th percentile] relative anisotropy when compared to the anisotropy of Hostun sand at its critical state [Fig. 4]. Fg results for all our samples are greater than grain–grain contact fabric anisotropies Fc. Our Fg and Fc observations can not be easily attributed to grain shape or size differences since these properties are comparable across samples [Supplementary Fig. 3].

Preserved fabrics and Fg differ as a function of coordination number Z [Fig. 4]. Grains with Z ≥ 4 [non-rattlers] have comparable fabrics with the bulk packing and have Fg greater than or equal to the bulk packing [Fig. 4]. The opposite is true for the rattlers [Z ≤ 4], which do not have comparable fabrics with the bulk packing and have Fg less than or roughly equal to the bulk packing [Fig. 4]. These observations indicate that the non-rattlers control the observed bulk fabrics and that, during shearing, the rattlers are more likely to be randomly rearranged. Overall, these and the other fabric characteristics described above are unlikely to reflect transport direction at the site since the emplacement mechanisms between the aseismic [dune] and co-seismic [fluvial] samples differ, while some of the current fabrics are similar. Tectonic slip is, thus, the most likely cause for the observed fabrics.

Discussion

Our primary interpretation is that cumulative shear strain, grain size, and coordination number primarily control sediment deformation in the fault zones. We discuss how past tectonic forcings have created a form of material memory that fits within the soft matter frictional jamming framework, albeit with expressions different from those of idealized systems.

Shear stress controls on deformation and resulting fabric

We have shown that co-seismic shearing generally leads to more deformation [comminution, size segregation, deformation bands] and that, in two out of the three samples at Ferrum, it imposes a grain fabric that is distinct from the one that develops due to aseismic slip. Further examination of the fault slip histories, fault geometry, and distances from the fault strand provides insight into why one of the three co-seismic samples, F_C_6.9, shows the distinct NE-SW aseismic fabric. Key observations are that (1) based on stratigraphic position, the Ferrum co-seismic samples have undergone more aseismic slip than the aseismic samples; (2) non-rattler grains within the co-seismic samples, F_C_0 and F_C_6.5, have some vestiges of a NE-SW aseismic fabric [Fig. 4b, c and Supplementary Fig. 4]; and (3) the co-seismic sample F_C_6.5 has a more uniform fabric than the co-seismic sample F_C_0. Based on these observations, the fabric of the two co-seismic samples that do not show distinct NE-SW preferred orientations may be explained in two ways. Either the duration or magnitude of stresses imparted by aseismic slip between sediment deposition and the ca. 1726 earthquake was insufficient to produce stronger azimuthal orientations. Or, the azimuthal orientations were initially present but were mechanically erased during the ca. 1726 earthquake.

We cannot determine if the azimuthal fabric existed in the co-seismic samples before the ca. 1726 earthquake. However, different fabrics in these samples suggest that strain or response to the strain is spatially variable, and some samples have not been rearranged by three centuries of aseismic slip. We calculate bulk friction of the samples from Fc, following Lee et al.67, who showed that Fc-derived bulk friction can sensitively distinguish between granular systems with higher and lower friction, despite its tendency to slightly under-predict the true friction values. Our Fc-derived bulk friction values are in the range of friction for unconsolidated granular Earth materials68,69,70, with the fault strand sample, F_C_0, having the highest value [1.1] compared to all other samples [0.2–0.8]. We thus interpret the relatively greater frictional resistance in the fault strand sample as the likely cause of the lack of a distinct NE-SW aseismic bulk fabric. This resistance likely occurred because the 1726 earthquake that created the Ferrum fault localized strain within the sediments surrounding the newly created slip surface, which occurs even under low confining pressures71. These observations lead us to prefer the interpretation that pre-earthquake fabric was mechanically erased by the ca. 1726 earthquake.

Analyzing the non-rattler fabric provides additional insights into how sediments at Ferrum accommodated aseismic shearing. The non-rattler fabrics for samples F_A_2.5/2.7 and F_C_6.9 are similar to their respective bulk fabrics, with grains at all inclinations preferentially aligning NE-SW, sub-perpendicular to the mean SAF strike [Fig. 4d–f]. In contrast, the horizontally inclined non-rattler grains [i.e, those with inclinations 75°–90°] in F_C_0/6.5 align NW-SE, sub-parallel to the mean SAF strike [Fig. 4b, c]. In the case where a simple shear model applies to the site, the NE-SW non-rattler fabric in samples F_A_2.5/2.7 and F_C_6.9 would be akin to conjugate Riedel structures that form ~75° from the principal slip direction [Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4]. And, the NW-SE non-rattler fabric in the horizontally inclined grains of samples F_C_0/6.5 would be akin to Riedel shear structures that form ~10° from the principal slip direction [Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4]. These observations imply that co-seismic samples F_C_0/6.5 are shear hardened in the fault parallel direction [NW-SE], while being fragile and accommodating aseismic deformation in the sub-perpendicular direction [NE-SW]. Further, the existence of some NE-SW fabric within all Ferrum samples implies that the stresses associated with aseismic slip are below some critical threshold to induce bulk re-arrangements in the directions of the mean SAF strike.

The preferred orientations and interpreted simple shear structures in our samples are similar to those observed in other field studies and lab experiments. Microfractures and ductile deformed grains within exhumed rocks primarily align in the slip direction of shear zones, demonstrating preferred orientation72. Laboratory experiments on powdered calcite gouge sheared at seismogenic pressures and examined with thin sections likewise show crystallographic preferred orientations within shear bands that develop at relatively low temperatures [20 °C]73. Conjugate deformation patterns, such as the conjugate-like structures we see in the non-rattlers of the Ferrum samples, are evident at the kilometer scale in the orientations of fractures and faults in crystalline rocks74, at the field-scale in the form of deformation bands within near-surface sediments38 and sandstones75 sheared by active faults, and at the grain-scale revealed by thin sections analyses of near-surface sediments adjacent to an active fault37. Conjugate-like shear bands also emerge during molecular dynamic simulations of metallic glasses under tensile deformation76, revealing these features even at the microscale. Our study extends these findings by demonstrating that tectonic shearing leads to conjugate deformation patterns in the long-axis orientation of non-rattlers that are broadly distributed within the fault zone sediments at Ferrum.

Material memory and frictional jamming

Our observations and interpretations are reminiscent of the expressions of frictional jamming, material memory, and ACST seen in lab and numerical simulations. We observe and interpret that (1) greater cumulative strain leads to more yielding processes, an observation also seen in decades of shearing studies13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20; (2) consistent with features of shear-jammed and fragile states24,26,77, anisotropic fabrics develop and lead to shear hardening in one direction versus relatively more fragility in antithetical directions—this also includes the observation that aseismic forcings are not sufficient to rearrange co-seismically sheared grains closest to the fault strand in the fault strike direction; and (3) the fabrics that develop differ as a function of the magnitudes of past tectonic forcing [material memory]29,31. A detailed comparison of our fabric results with lab and simulation studies is challenging, partly because there has not been, to our knowledge, 3D quantification of the fabrics that develop during the shearing of granular materials with grain shape and size disorder comparable to our natural system. Some features of fault zone fabrics are similar to lab and simulation studies, whereas others differ and shed light on the influence of disorder on frictionally jammed granular materials26,27,77. For example, Cunez et al.77 used similar observations of shear hardening in the direction of shear to identify shear jammed states in the absence of access to contact force networks within a lab assemblage of spheres. Simulations done on packings of spheres also show that shearing induces cooperative re-arrangements of the grain–grain contact geometries and positions of non-rattlers in the direction of the mean global shear field, whereas rattlers exhibit higher kinetic energies, intermittent dynamics, and velocity fluctuations, which makes them more free to move within and outside their cages78,79,80,81. These simulation results provide a theoretical explanation for why we observe a difference in the fabric anisotropies and grain orientations of rattlers versus non-rattlers. Extending these studies, our results further demonstrate that the non-rattlers and their long-axis orientations exhibit greater control on the fabric anisotropy and that the re-arrangement of the non-rattlers likely occurs in competition with other granular phenomenologies in a disordered natural system.

Despite the anticipated net dilation at our field site, it is interesting that we still observed fabrics similar to those that develop in the volume-preserving framework of frictional jamming. This can be explained by existing observations that net constant volume shearing still leads to sub-regions where local volume dilation occurs versus others where it does not82. The differences in local dilation at Ferrum are the likely cause for grain fracturing and re-arrangement in close proximity; here, we propose that fracturing occurs in sub-regions of low dilation, whereas re-arrangements occur in sub-regions of higher relative dilation, consistent with existing lab studies83,84. Our results, thus, point to a possible unification of the frictional jamming and ACST into a single framework where the fabric is studied with both scalar anisotropic fabric measurements and concepts from material memory. A connection between frictional jamming and ACST was suggested by Wen and Zhang27, who acknowledge that the distinction between unjammed and jammed states in the frictional jamming framework is equivalent to the critical state in soil mechanics. Their results also suggest the existence of another frictionally jammed state in the pressure-volume fraction jamming space that was not observed in the simulations but might occur when shearing induces changes in particle size and shape distribution27. This state space might be a place where some natural fabrics lie, considering that we observe grain fracturing and size segregation in our samples.

Though the effects of grain fracturing need further studies, our results suggest that grain size and coordination number influence how fault zone sediment fabrics develop and get preserved. The preferential cushioning of large grains [Fig. 2o] and the folding of an off-fault sediment smear tip near a large grain [Fig. 2i] point to some degree of grain size control on how material memory is preserved. The observations that non-rattler grains are the major contributor to the bulk fabric and have a more anisotropic fabric than the rattlers also support the interpretation that coordination numbers influence the preservation of material memory. Further, phenomenological mesostructures resulting from bulk granular shearing—segregation, shear bands, and grain fracturing—occur within sub-volumes of the samples and sometimes do not spatially extend across the entire volume. This implies centimeter-scale competitions between granular flow phenomena that impede a larger expression of certain mesostructures in this natural system.

Conclusion

We examine the fabrics of sheared fault zone sediments collected at Pallett Creek and Ferrum along the southern SAF. We also assess whether frictional jamming and material memory exist within these near-surface granular materials and determine if these conceptual frameworks can provide insights into the earthquake cycle and shallow strain gradients. Analyses of 19 samples from layers with known paleoseismic histories demonstrate that frictional jamming remains a promising framework for understanding solid-to-fluid-like state transitions if extended to natural sediments, where particle breakage occurs and disorder is greater. These natural granular systems preserve a material memory that can be examined in three dimensions. This memory may help decipher the paleoseismic slip histories of faults that have produced ground-rupturing earthquakes and creep. Our analyses indicate that fault zone sediments likely experience cycles of shear-induced material memory creation and erasure wherein aseismic slip produces a distinct fabric that can then be erased and replaced during co-seismic slip [Fig. 5]. In this conceptual model, each stage of the seismic cycle creates new grain-pore relationships that govern the system’s strength as the seismic cycle progresses. We predict that this cycle repeats across multiple shallow fault zones where the overburden pressure does not inhibit grain re-arrangements before fracturing. Our results suggest a broad range of friction values within the same or adjacent sedimentary units, further supporting the idea that co-seismic slip leads to off-fault deformation that spatially varies in near-surface granular materials. Our findings have implications for modeling rigidity loss, the earthquake energy budget, and rupture propagation within the shallow subsurface. Finally, our work demonstrates that the near-surface shear stresses during ground-rupturing earthquakes and aseismic slip are sufficient to break grains away from the fault slip surface.

During the interseismic period, aseismic slip induces a fabric within unconsolidated sediments. During ground-rupturing events, the aseismic fabric is erased because net dilation and vibrations due to the release of stored energy rearrange the grains, leading to the creation of a new fabric. We refer to this new fabric as a co-seismic fabric, and both fabrics overprint the depositional fabric. During the subsequent interseismic period, the preservation of the co-seismic fabric depends on the distance from the slip surface. Near the slip surface, the fabric is preserved, but begins to fade away from the slip surface and is eventually overprinted by the aseismic slip fabric.

Methods

Sample collection

We collect the samples using 40 mm long by 10 mm diameter aluminum tubes and with a method that minimizes grain disturbance during sampling40,41. First, we insert the tubes perpendicular to the outcrop wall with one end of the tube taped. We then remove grains immediately surrounding the tubes and extract and tape the tubes’ other end. We wrap cheesecloth around the tubes and then dip the ends in melted candle wax. We enclose the tubes in moist paper towels, store them in a closed-lid container with bubble wrap, and then transport the samples to the lab. Samples remain untouched until we transport them for X-ray computed tomography [XRCT] image acquisition.

XRCT image acquisition and processing

We acquire XRCT images of all nineteen samples on beamline 8.3.2 at the Advanced Light Source [ALS], Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. ALS imaging equipment includes a 50 mm LuAG scintillator, a Pioneers in Cameras and Optoelectronics Edge camera, and a 2X Nikon lens. We image with white light X-rays, 13 ms exposure times, and 2625 projections through 180° continuous sample rotations. These parameters result in 1280 to 1296 two-dimensional image slices with voxel linear dimensions of 3.24 μm. Some image sets thus capture the middle 4.1–4.2 mm of the sample tubes. We reconstruct images and perform ring/outlier removals and center of rotation optimizations using TomoPy85. We re-scanned samples FT_10_1 and FT_10_2 at the High-Resolution X-ray CT Facility at the University of Texas, Austin [UTCT] to improve the signal-to-noise ratios within the images. We reconstructed 1330 two-dimensional slices from these samples with the Xradia Reconstructor, and their resulting voxel sizes are 4.15 μm. Our images are from the middle 5.5 mm of the sample tube.

We filter, binarize, and segment the reconstructed images in Fiji40,41,86. We denoise the ALS images by applying a 3D Gaussian blur [sigma = 2] and a 3D mean [radius = 2] filter. We apply a non-local means filter87 to denoise the UTCT images. We binarize six of the 19 image sets from the ALS using the Trainable Weka Segmentation machine learning algorithm88. Grain sizes in the other samples scanned at the ALS were too small to reliably binarize. Our Weka training classifiers contain >10 cross sections of grains and pores that we manually outline on every 35th image slice. We use the eigenvalues of Hessian tensors [smoothing scale = 1–8 voxels] and the means [number of neighboring voxels = 1–8] to classify edge-detection and textural image features that aid Weka. We binarize the two UTCT-scanned image sets with a global Otsu threshold. Post binarization, we identify voxels representing individual grains in each sample using the 3D Distance Transform Watershed algorithm [distance map = Borgefors, dynamic parameter = 5, connectivity = 26]. When uniquely labeling each grain, the algorithm removes a voxel-wide gap between touching grains, so we use a cube structuring element [radius = 1] to re-establish the voxel-wide gap.

Physical property calculation and analyses

We use functions within the Software for Practical Analyses of Materials89 to calculate grain physical properties. We calculate true sphericity \({S}_{t}=\frac{{S}_{n}}{S}\)90,91, where Sn is the surface area of an equivalent sphere and S is the actual particle surface area. We calculate convexity \(C=\frac{V}{{V}_{{{\rm{CH}}}}},\)92, where V is the particle volume and VCH is the volume of the particle’s convex hull. We use the grain sphericity and convexity data to support evidence of grain fracturing associated with attrition—higher sphericity and convexity are often associated with grains that experience greater magnitudes of attrition from the chipping mode of fracturing63. We also calculate the assemblages’ volume fraction and grain coordination numbers Z, following the procedure described by Wiebicke et al.93. Compared to the suggested local threshold for collections of spheres, 0.71, we chose a lower one due to the angular nature of our grains and because we lost visually apparent contacts at/near the suggested threshold. The chosen local threshold is 0.5 after normalizing all samples’ intensity range to [0,1] and mapping the void and grain intensity peaks to ~0.25 and ~0.75, respectively. We use the coordination number to calculate the fraction of non-rattler grains fNR, defining a rattler as grains with fewer than four contacts as established by the theoretical upper frictional limit [when μ → ∞] for isostasy in frictional assemblages, \({Z}_{c}^{\infty }=D+1\)23,80,94. We show examples of the segmentation results in the supplement [Supplementary Fig. 2].

We define and calculate grain orientation using two angles: inclination [i.e., the angle that the grains’ long axis forms with the vertical] and azimuth [i.e., the angle of the grains’ long axis relative to the long axis of the sample tube, projected onto a horizontal plane]. We use Lambert azimuthal equal-area projection maps to compare the relative grain orientations between samples. We fit the grain orientation data to a von Mises-Fisher distribution to estimate the mean direction and assess whether they are uniform or exhibit directional preferences. von Mises-Fisher distributions are defined on the entire sphere for directional data. We ensure that our calculations are consistent with this definition by concatenating each grain’s long axis vector with its inverse, computing the principal orientation vector, and then aligning all principal vectors to a single hemisphere before data fitting. We calculate fabric tensors \({{\bf{F}}}=\frac{1}{N}\mathop{\sum }_{k = 1}^{N}{{{\bf{v}}}}^{(k)}\otimes {{{\bf{v}}}}^{(k)}\)95, where v represents the kth orientation of grain–grain contact or grain long axis, and N is the total number of orientations. We use Fc and Fg to denote fabric tensors that are based on grain contacts versus long-axis orientation, respectively. We calculate the fabric anisotropy, F, from the deviatoric component of the fabric tensors, \({{\bf{D}}}=\frac{15}{2}({{\bf{F}}}-\frac{1}{3}{{\bf{I}}});\,F=\sqrt{\frac{3}{2}{{\bf{D}}}:{{\bf{D}}}}\)27,66,96, where I is the identity tensor. F quantifies the degree of anisotropy from the fabric tensors and ranges from 0, a completely isotropic fabric, to 7.5, a completely anisotropic fabric. We similarly denote Fc as the contact fabric anisotropy and Fg as the grain long axis fabric anisotropy. Triaxial compression experiments on angular Hostun sands observe Fg ≈ 1.2 and Fc ≈ 0.90 at large axial strains [>12%] corresponding to their critical state66.

We visually examine all nineteen XRCT image sets to identify deformation features such as shear bands, comminuted grains, grain size segregation, and in situ fractured grains. Five individuals independently identified and counted the number of in situ broken grains. Following Zhao et al.97 and Zhang et al.92, we determine that grains have been fractured in situ if [1] they are offset by ≤10 μm, [2] closing the offset would cause grain boundaries to fit together like puzzle pieces, and [3] the grain boundaries have the same grayscale values. Cushioning, wherein smaller grains distribute around the surface of larger grains rather than being rattlers that prevent larger grains from being in contact, is another well-established feature that we use to identify in situ grain fracturing98,99,100. We determine that grains have an internal fracture if [1] there is a group of connected voxels with fracture-like geometries within a grain and [2] the connected voxels’ grayscale values are similar to the grayscale values of the pores surrounding the grains92,97,100. Our analyses are not sensitive to broken grain fragments transported sufficiently far away from their parent grains.

Data availability

All data [i.e., processed XRCT greyscale and watershed images] used in this study can be found at two Zenodo repositories, Dasent et al.101 and Dasent et al.102. The authors separate the data between two repositories101,102 due to file size limitations [max 50 GB]. Each greyscale image is ~3–7 GB, and each watershed image is ~12–15 GB. The repositories may be accessed by searching their record numbers, 15178688 and 15192537, at https://zenodo.org.

Code availability

Readers can find the two, restriction-free, Python scripts used for data analysis and plotting in this study at the Zenodo repository, Dasent et al.101.

References

Börker, J., Hartmann, J., Amann, T. & Romero-Mujalli, G. Terrestrial sediments of the earth: development of a global unconsolidated sediments map database (gum). Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 997–1024 (2018).

Roering, J. J. Soil creep and convex-upward velocity profiles: theoretical and experimental investigation of disturbance-driven sediment transport on hillslopes. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms: J. Br. Geomorphol. Res. Group 29, 1597–1612 (2004).

Vriend, N. M. et al. Solving the mystery of booming sand dunes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L16306 (2007).

Jerolmack, D. J. & Daniels, K. E. Viewing Earth’s surface as a soft-matter landscape. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 716–730 (2019).

Glade, R. C., Fratkin, M. M., Pouragha, M., Seiphoori, A. & Rowland, J. C. Arctic soil patterns analogous to fluid instabilities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2101255118 (2021).

Deshpande, N. S., Furbish, D. J., Arratia, P. E. & Jerolmack, D. J. The perpetual fragility of creeping hillslopes. Nat. Commun. 12, 3909 (2021).

Ferrier, K. L., Kirchner, J. W. & Finkel, R. C. Erosion rates over millennial and decadal timescales at Caspar Creek and Redwood Creek, Northern California Coast Ranges. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 30, 1025–1038 (2005).

Wright, V. & Hornbach, M. The effects of 180 years of aging on the physical and seismic properties of partially saturated sands. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2020JB021341 (2021).

Drucker, D. C. & Prager, W. Soil mechanics and plastic analysis or limit design. Q. Appl. Math. 10, 157–165 (1952).

Roscoe, K. H., Schofield, A. N. & Wroth, C. P. On The Yielding of Soils. Géotechnique 8, 22–53 (1958).

Schofield, A. N. & Wroth, P. Critical State Soil Mechanics Vol. 310 (McGraw-Hill London, 1968).

Roscoe, K. H. The influence of strains in soil mechanics. Géotechnique 20, 129–170 (1970).

Casagrande, A. Shear failure of anisotropic materials. Proc. Boston Soc. Civ. Eng. 31, 74–87 (1944).

Oda, M. Initial fabrics and their relations to mechanical properties of granular material. Soils Found. 12, 17–36 (1972).

Oda, M. The mechanism of fabric changes during compressional deformation of sand. Soils Found. 12, 1–18 (1972).

Oda, M. et al. Stress-induced anisotropy in granular masses. Soils Found. 25, 85–97 (1985).

Mehrabadi, M. M., Nemat-Nasser, S. & Oda, M. On statistical description of stress and fabric in granular materials. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 6, 95–108 (1982).

Rothenburg, L. & Bathurst, R. J. Analytical study of induced anisotropy in idealized granular materials. Géotechnique 39, 601–614 (1989).

Mehrabadi, M. M., Loret, B., Nemat-Nasser, S. & Oda, M. Incremental constitutive relations for granular materials based on micromechanics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 441, 433–463 (1993).

Kruyt, N. P. & Rothenburg, L. Micromechanical definition of the strain tensor for granular materials. J. Appl. Mech. 63, 706–711 (1996).

Fu, P. & Dafalias, Y. F. Fabric evolution within shear bands of granular materials and its relation to critical state theory. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 35, 1918–1948 (2011).

Li, X. S. & Dafalias, Y. F. Anisotropic critical state theory: role of fabric. J. Eng. Mech. 138, 263–275 (2012).

Silbert, L. E. Jamming of frictional spheres and random loose packing. Soft Matter 6, 2918–2924 (2010).

Bi, D., Zhang, J., Chakraborty, B. & Behringer, R. P. Jamming by shear. Nature 480, 355–358 (2011).

Behringer, R. P. & Chakraborty, B. The physics of jamming for granular materials: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 82, 012601 (2019).

Pan, D., Wang, Y., Yoshino, H., Zhang, J. & Jin, Y. A review on shear jamming. Phys. Rep. 1038, 1–18 (2023).

Wen, Y. & Zhang, Y. Fabric-based jamming phase diagram for frictional granular materials. Soft Matter 20, 3175–3190 (2024).

Paulsen, J. D. & Keim, N. C. Mechanical memories in solids, from disorder to design. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 16, 61–81 (2025).

Keim, N. C. & Nagel, S. R. Generic transient memory formation in disordered systems with noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 010603 (2011).

Kumar, N. & Luding, S. Memory of jamming–multiscale models for soft and granular matter. Granul. Matter 18, 58 (2016).

Keim, N. C., Paulsen, J. D., Zeravcic, Z., Sastry, S. & Nagel, S. R. Memory formation in matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 035002 (2019).

Lucas, S. E. & Moore, J. C. Cataclastic deformation in accretionary wedges: Deep Sea Drilling Project Leg 66, southern Mexico, and on-land examples from Barbados and Kodiak Islands. Geol. Soc. Am. Mem. 166, 89–104 (1986).

Cashman, S. & Cashman, K. Cataclasis and deformation-band formation in unconsolidated marine terrace sand, Humboldt County, California. Geology 28, 111–114 (2000).

Du Bernard, X., Eichhubl, P. & Aydin, A. Dilation bands: a new form of localized failure in granular media. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 1–4 (2002).

Baldwin, J. N., Barren, A. D., Kelson, K. I., Harris, J. B. & Cashman, S. Preliminary paleoseismic and geophysical investigation of the North Farrenburg Lineament: primary tectonic deformation associated with the New Madrid North Fault? Seismol. Res. Lett. 73, 393–413 (2002).

Rawling, G. C. & Goodwin, L. B. Cataclasis and particulate flow in faulted, poorly lithified sediments. J. Struct. Geol. 25, 317–331 (2003).

Cashman, S., Baldwin, J. N., Cashman, K., Swanson, K. & Crawford, R. Microstructures developed by coseismic and aseismic faulting in near-surface sediments, San Andreas fault, California. Geology 35, 611–614 (2007).

Kaproth, B. M., Cashman, S. M. & Marone, C. Deformation band formation and strength evolution in unlithified sand: The role of grain breakage. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 115 (2010).

Balsamo, F. & Storti, F. Size-dependent comminution, tectonic mixing, and sealing behavior of a “structurally oversimplified" fault zone in poorly lithified sands: evidence for a coseismic rupture? Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 123, 601–619 (2011).

Ferrick, A., Wright, V., Manga, M. & Sitar, N. Microstructural differences between naturally-deposited and laboratory beach sands. Granul. Matter 24, 9 (2022).

Wright, V., Ferrick, A., Manga, M. & Sitar, N. Coordination numbers in natural beach sand. EPJ Web Conf. 249, 11008 (2021).

Sieh, K. E. Prehistoric large earthquakes produced by slip on the San Andreas Fault at Pallett Creek, California. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 83, 3907–3939 (1978).

Sieh, K. E. Lateral offsets and revised dates of large prehistoric earthquakes at Pallett Creek, Southern California. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 89, 7641–7670 (1984).

Sieh, K., Stuiver, M. & Brillinger, D. A more precise chronology of earthquakes produced by the San Andreas fault in southern California. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 94, 603–623 (1989).

Sieh, K. E. & Williams, P. L. Behavior of the southernmost San Andreas Fault during the past 300 years. J. Geophys. Res. 95, 6629 (1990).

Scharer, K. M., Biasi, G. P. & Weldon II, R. J. A reevaluation of the Pallett Creek earthquake chronology based on new AMS radiocarbon dates, San Andreas fault, California. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 116, B12111 (2011).

Rockwell, T., Buckley, W., Williams, P., Gontz, A. & Scharer, K. Testing Recurrence Models for the Southernmost San Andreas Fault by Developing a New Paleoseismic Site at Durmid, Salton Trough: Collaborative Research with SDSU and USGS Final Technical Report https://earthquake.usgs.gov/cfusion/external_grants/reports/G21AP10005.pdf (2022).

U.S. Geological Survey and California Geological Survey. Quaternary Fault and Fold Database for the United States. https://www.usgs.gov/natural-hazards/earthquake-hazards/faults (2003).

Rockwell, T. K., Meltzner, A. J., Haaker, E. C. & Madugo, D. The late Holocene history of Lake Cahuilla: two thousand years of repeated fillings within the Salton Trough, Imperial Valley, California. Quat. Sci. Rev. 282, 107456 (2022).

Scharer, K. M. & Yule, D. A Maximum Rupture Model for the Southern San Andreas and San Jacinto Faults, California, Derived From Paleoseismic Earthquake Ages: Observations and Limitations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088532 (2020).

Tymofyeyeva, E. et al. Slow slip event on the Southern San Andreas Fault triggered by the 2017 Mw 8.2 Chiapas (Mexico) Earthquake. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 124, 9956–9975 (2019).

Parker, J. et al. Buried Aseismic Slip and Off-Fault Deformation on the Southernmost San Andreas Fault Triggered by the 2010 El Mayor Cucapah Earthquake Revealed by UAVSAR. Earth Space Sci. 8, e2021EA001682 (2021).

Nevitt, J. M. et al. Mechanics of near-field deformation during co-and post-seismic shallow fault slip. Sci. Rep. 10, 5031 (2020).

Blanton, C. M., Rockwell, T. K., Gontz, A. & Kelly, J. T. Refining the spatial and temporal signatures of creep and co-seismic slip along the southern San Andreas Fault using very high resolution UAS imagery and SfM-derived topography, Coachella Valley, California. Geomorphology 357, 107064 (2020).

Materna, K. et al. Shallow slow slip events in the Imperial Valley with along-strike propagation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL108089 (2024).

Kwiatek, G. & Ben-Zion, Y. Detection limits and near-field ground motions of fast and slow earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125, e2019JB018935 (2020).

Ma, S. A physical model for widespread near-surface and fault zone damage induced by earthquakes. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, 2008GC002231 (2008).

Roten, D., Olsen, K. & Day, S. Off-fault deformations and shallow slip deficit from dynamic rupture simulations with fault zone plasticity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 7733–7742 (2017).

Fossen, H., Schultz, R. A., Shipton, Z. K. & Mair, K. Deformation bands in sandstone: a review. J. Geol. Soc. 164, 755–769 (2007).

Hill, K. M., Bereket, Y., Dietrich, W. E. & Hsu, L. Discrete element modeling and large scale experimental studies of bouldery debris flows. Ital. J. Eng. Geol. Environ. 435–447 https://doi.org/10.4408/IJEGE.2011-03.B-049 (2011).

Edwards, A. N. & Vriend, N. M. Size segregation in a granular bore. Phys. Rev. Fluids 1, 064201 (2016).

Ferdowsi, B., Ortiz, C. P., Houssais, M. & Jerolmack, D. J. River-bed armouring as a granular segregation phenomenon. Nat. Commun. 8, 1363 (2017).

Bodek, S. & Jerolmack, D. J. Breaking down chipping and fragmentation in sediment transport: the control of material strength. Earth Surf. Dyn. 9, 1531–1543 (2021).

Wang, W.-J. & Zhu, Z.-G. Two kinds of dissipation in sheared granular materials. Europhys. Lett. 82, 24004 (2008).

Ord, A., Hobbs, B. & Regenauer-Lieb, K. Shear band emergence in granular materials—a numerical study. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 31, 373–393 (2007).

Wiebicke, M., Herle, I., Andò, E. & Viggiani, G. Measuring the fabric evolution of sand—application and challenges. Geotechnik 44, 114–122 (2021).

Lee, C. L., Bililign, E., Azéma, E. & Daniels, K. E. Particle scale anisotropy controls bulk properties in sheared granular materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 108201 (2025).

Webster, A. G. On the angle of repose of wet sand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 5, 263–265 (1919).

Samadani, A. & Kudrolli, A. Angle of repose and segregation in cohesive granular matter. Phys. Rev. E 64, 051301 (2001).

Beakawi Al-Hashemi, H. M. & Baghabra Al-Amoudi, O. S. A review on the angle of repose of granular materials. Powder Technol. 330, 397–417 (2018).

Alshibli, K. A., Batiste, S. N. & Sture, S. Strain localization in sand: plane strain versus triaxial compression. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 129, 483–494 (2003).

Shigematsu, N. et al. Evolution of the Median Tectonic Line fault zone, SW Japan, during exhumation. Tectonophysics 696-697, 52–69 (2017).

Verberne, B. A., Niemeijer, A. R., De Bresser, J. H. P. & Spiers, C. J. Mechanical behavior and microstructure of simulated calcite fault gouge sheared at 20–600 °C: implications for natural faults in limestones. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 8169–8196 (2015).

Mitchell, T. & Faulkner, D. The nature and origin of off-fault damage surrounding strike-slip fault zones with a wide range of displacements: a field study from the Atacama fault system, Northern Chile. J. Struct. Geol. 31, 802–816 (2009).

Olsson, W. A., Lorenz, J. C. & Cooper, S. P. A mechanical model for multiply-oriented conjugate deformation bands. J. Struct. Geol. 26, 325–338 (2004).

Zhong, C. et al. Deformation behavior of metallic glasses with shear band like atomic structure: a molecular dynamics study. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–2 (2016).

Cúñez, F. D., Franklin, E. M., Houssais, M., Arratia, P. & Jerolmack, D. J. Strain hardening by sediment transport. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, L022055 (2022).

O’Hern, C. S., Silbert, L. E., Liu, A. J. & Nagel, S. R. Jamming at zero temperature and zero applied stress: the epitome of disorder. Phys. Rev. E 68, 011306 (2003).

Wyart, M. On the rigidity of amorphous solids. Ann. Phys. 300, 1–29 (2005).

Silbert, L. E., Ertaş, D., Grest, G. S., Halsey, T. C. & Levine, D. Geometry of frictionless and frictional sphere packings. Phys. Rev. E 65, 031304 (2002).

Radjai, F., Jean, M., Moreau, J.-J. & Roux, S. Bimodal character of stress transmission in granular packings. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 61–64 (1998).

Vatsa, G., Fazelpour, F., Gautam, R., Daniels, K. E. & Nott, P. R. Dilatancy and its coupling to the kinematics in sheared granular media. J. Fluid Mech. 1003, A11 (2025).

Alikarami, R., Andò, E., Gkiousas-Kapnisis, M., Torabi, A. & Viggiani, G. Strain localisation and grain breakage in sand under shearing at high mean stress: insights from in situ x-ray tomography. Acta Geotech. 10, 15–30 (2015).

Zhai, C. et al. Quantifying local rearrangements in three-dimensional granular materials: rearrangement measures, correlations, and relationship to stresses. Phys. Rev. E 105, 014904 (2022).

Gürsoy, D., De Carlo, F., Xiao, X. & Jacobsen, C. TomoPy: a framework for the analysis of synchrotron tomographic data. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 21, 1188–1193 (2014).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Buades, A., Coll, B. & Morel, J.-M. Non-local means denoising. Image Process. On Line 1, 208–212 (2011).

Arganda-Carreras, I. et al. Trainable Weka Segmentation: a machine learning tool for microscopy pixel classification. Bioinformatics 33, 2424–2426 (2017).

Stamati, O. et al. Spam: software for practical analysis of materials. J. Open Source Softw. 5, 2286 (2020).

Rorato, R., Arroyo, M., Andò, E. & Gens, A. Sphericity measures of sand grains. Eng. Geol. 254, 43–53 (2019).

Wadell, H. Volume, shape, and roundness of rock particles. J. Geol. 40, 443–451 (1932).

Zhang, T. et al. Breakage behavior of silica sands during high-pressure triaxial loading using X-ray microtomography. Acta Geotech. 18, 5195–5211 (2023).

Wiebicke, M., Andò, E., Herle, I. & Viggiani, G. On the metrology of interparticle contacts in sand from X-ray tomography images. Meas. Sci. Technol. 28, 124007 (2017).

Edwards, S. The equations of stress in a granular material. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 249, 226–231 (1998).

Ken-Ichi, K. Distribution of directional data and fabric tensors. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 22, 149–164 (1984).

Gu, X., Hu, J. & Huang, M. Anisotropy of elasticity and fabric of granular soils. Granul. Matter 19, 33 (2017).

Zhao, B., Wang, J., Andò, E., Viggiani, G. & Coop, M. R. Investigation of particle breakage under one-dimensional compression of sand using X-ray microtomography. Can. Geotech. J. 57, 754–762 (2020).

Sammis, C., King, G. & Biegel, R. The kinematics of gouge deformation. Pure Appl. Geophys. 125, 777–812 (1987).

Ogilvie, S. R. & Glover, P. W. The petrophysical properties of deformation bands in relation to their microstructure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 193, 129–142 (2001).

Zhu, H. et al. Grain-scale petrographic evidence for distinguishing detrital and authigenic quartz in shale: How much of a role do they play for reservoir property and mechanical characteristic? Energy 239, 122176 (2022).

Dasent, J. Datasets for “memory and jamming in fault zone sediments”. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15178688 (2025).

Dasent, J. Dataset for “memory and jamming in fault zone sediments”. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15192537 (2025).

Acknowledgements

J.D., R.K., and V.W. acknowledge support from National Science Foundation Grant 2136301. K.S. and J.D. acknowledge support from the U.S. Geological Survey Earthquake Hazards Program. M.M. and V.W. acknowledge support from the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research Earth4D program. The authors thank Dula Parkinson at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab and Jessie Maisano at the University of Texas, Austin, for help with acquiring XRCT images. Special thanks to Kenneth Su and Shipra Gudekar for helping to count broken grains. The authors likewise thank Bart Verberne, N. van der Elst, and one additional anonymous reviewer for constructive feedback and suggestions. No permissions were required for geological sample collection. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, review and editing, visualization. V.W.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, resources, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. K.S.: investigation, writing—review and editing, visualization, funding acquisition. M.M.: investigation, writing—review and editing. R.K.: investigation, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Berend Verberne and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Adriana Paluszny and Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dasent, J., Wright, V., Scharer, K. et al. Memory and jamming in fault zone sediments. Commun Earth Environ 6, 998 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02952-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02952-4