Abstract

Large predators are returning to landscapes where they have been absent for centuries, but human preferences complicate their recovery. Communities often resist predator recovery because of perceived risks, limiting what managers call social carrying capacity, or the level of human tolerance for coexisting with wildlife. Yet practical methods for measuring and integrating social carrying capacity into management decisions remain limited. To address this, we combine geospatial and survey data to model individual tolerance for the frequency and severity of grizzly bear encounters. The resulting estimates predict and map zip code-level tolerance across the region. Findings show that people tend to overestimate management’s tolerance of encounters than current federal guidelines. This approach provides a pragmatic tool to incorporate social carrying capacity into decisions about predator recovery and reintroduction, helping balance ecological goals with public acceptance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global trophic rewilding has accelerated since the late 20th century, returning many keystone predators to human-occupied landscapes1. Successful2,3, ongoing4,5,6, and proposed reintroduction and recolonization7,8 programs of large predators have faced local push-back despite ecological incentives9,10. Promoting human-predator coexistence has been a longstanding priority of wildlife managers11,12; an increasingly difficult task with the growth in outdoor recreation and residential development in the wildland-urban interface (WUI)13,14,15.

Despite this, current management plans and wildlife reintroduction often have little consideration for human tolerance for wildlife risk. Instead, manager responses to predator conflict typically follow top-down federal guidelines that support recovery, developed during periods of strong conservation16. The management plans usually rely on a species being listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA), which may shift priorities from mitigating conflicts to species recovery. Yet as wildlife populations recover, the potential for human-predator conflict increases17.

Social tolerance of human-wildlife risks plays an important role in the success of reintroduction and recovery efforts18. Social tolerance reflects the willingness to accept the risks associated with wildlife encounters and is a multidimensional concept that includes attitudes and perceptions that vary across many dimensions, including beliefs, lifestyle, experience, and location19. While incorporating aspects of social tolerance can be complicated20, wildlife managers can improve long-term outcomes for wildlife by understanding how different stakeholders perceive and respond to wildlife-related risks21. While managers adapt guidelines to account for context-specific factors, management decisions would benefit from a systematic assessment of local risk tolerance22. This is particularly apt in rural communities where property damages, livestock losses, and threats to human safety heavily influence wildlife outcomes.

While they impose risks to humans, predators benefit landscapes by providing critical ecosystem services and functioning, such as disease mitigation, agricultural production through pest management, and waste disposal23. Further, public discourse and the spread of information related to predators create opportunities to educate the public about ecosystem health and human-wildlife relationships24. Complications arise because there are heterogeneous preferences for predator conservation within and across local communities, which makes the implementation of uniform management guidelines challenging. As predator populations recover, humans and predators can better coexist with an understanding of the local community’s tolerance for predators25,26,27. There are a few empirical studies documenting public attitudes toward predator management. The ‘acceptance capacity” for grizzlies across the grizzly-inhabited landscape of Montana and Idaho has been used to identify hot spots of low tolerance where public policy might have the greatest effect28. Building on this result, regionally specific investigations have used only Montana residents’ personal opinions on grizzly abundance and how this aligns with current management29. Finding thresholds in abundance, under which grizzlies are locally acceptable and a problem if the threshold is exceeded, highlighting that there may be mismatches between the acceptance threshold and management objectives29. While concerns of local stakeholders, and the interplay between predator tolerance and management policy, can shape active management strategies, effective management can alleviate concerns and thereby increase tolerance30. In addition, for charismatic predators that live on federal public lands or have national appeal, such as grizzly bears, non-local stakeholder interests may be an important consideration in the development of management goals. In such cases, traditional active management strategies, like hunting and culling, can shift population targets to reflect preferences for a healthier, more stable species population, which may not be popular with certain stakeholders. This tradeoff highlights the need for inclusive approaches to balance heterogeneous beliefs in stakeholder values for predator management.

Social tolerance for predators and wildlife in general has been considered with concepts of cultural and social carrying capacities. These concepts were introduced to understand how human attitudes and beliefs could complicate management that is largely based on the theory of competition for scarce resources. Notably, pressures from “animal lovers” could lead to mismanagement, overpopulation of game animals, and eventual population declines due to a decline in the supportive capacity of the surrounding environment31,32. With a focus more on the sustainability of humans, the concept was not pushed at the time to the human acceptability of wildlife populations or population dynamics of human-wildlife interactions. Additionally, these studies lack a reflection of human tolerance to coexist with wildlife. As a result, the practical integration of “social carrying capacity” or risk tolerance in active wildlife management and legislative decisions has been limited.

In this paper, we develop a method to estimate spatially specific measures of risk preferences for predator encounters, specifically grizzly bears. Risk preferences represent tolerance and are measured by the acceptable number of encounters (i.e., thresholds) before the grizzly bear is removed (i.e., euthanized). We compare our estimates of overall and location-specific tolerance with the thresholds defined in current management guidelines. Results provide additional insights on the spatial variation of the local social carrying capacity of grizzly bears. More broadly, this study illustrates a potential pathway to measure and incorporate social carrying capacity into predator management, which may lead to more aligned community and management preferences and consequently more successful predator recovery33.

Results

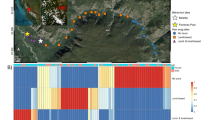

Our overarching finding is that respondents prefer a more tolerant approach than current grizzly bear management dictates (the current guidelines are outlined in Supplementary Table 1). At the time of writing, managers indicated that, depending on the overall population in an area, the number of allowed encounters could be increased or decreased above and below the written guidelines. Still, managers were confident that the stated guidelines were generally upheld. This administrative discretion is common in wildlife management and has been shown to reduce the number of conflicts in other predators10,34. National respondents, relative to the actual guidelines, are willing to accept a greater number of encounters before the bear is removed (Fig. 1). This finding emerges for all types of encounters—property, threat, and injury. Specifically, respondents indicated the preferred number of encounters to trigger removal is 3.8 for property, 3.1 for threat, and 2.6 for injury, which is significantly greater than the actual thresholds of 3, 2, and 1 (p < 0.001).

For each type of encounter, respondents overestimate the level of tolerance defined by the management guidelines (Fig. 1). For property and threat encounters, respondents correctly identified a misalignment between their preferred and actual tolerance levels, though their beliefs about the actual level reveal they underestimate the magnitude of these misalignments. For injury encounters, preferred and believed tolerance levels are statistically equivalent, which indicates that respondents mistakenly believe the tolerance of managers closely aligns with their preferred tolerance.

Results were similar when only considering the respondents from the states that are most affected by grizzly bear encounters and management—Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming (Fig. 2). As with the national sample, the respondents in states with grizzly bear habitat indicated significantly greater tolerance levels than those outlined in the guidelines. Also similar to the national results, respondents correctly identified the misalignment between preferred and actual tolerance for property and threat encounters, but not for injury encounters. We further refine the regional analysis by stratifying respondents by those located within 50 miles of grizzly bear habitat and those outside 50 miles, and the results are similar across the two groups (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7).

Overall, the aggregate numbers offer three key findings. First, results indicate that people prefer a level of tolerance significantly greater than the actual tolerance defined in the guidelines. Second, though people are largely aware of this misalignment (injury encounters being the exception), they underestimate the magnitude of the misalignment. Finally, these general findings emerged nationally and in states most affected by the presence and management of grizzly bears.

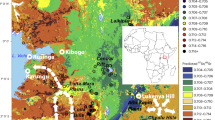

We use the zip code level predictions to create three national maps that offer a spatial representation of our findings. We start with Fig. 3, which illustrates the difference between the local social tolerance (preferred) and the overall management tolerance set by the national guidelines (actual). Thus, the map shows the spatial variation of the misalignment between the social and management tolerances for the risk of grizzly bear encounters. Across all zip codes, estimates indicate that social tolerance is larger than current management, but the extent of this misalignment varies across space. The greatest misalignment is found in the Midwest, Northeast, and West Coast (darker blue). Of particular interest are the areas in and around grizzly habitat, and while estimates suggest social tolerance exceeds management tolerance in these areas, the magnitude is smaller than in other areas (lighter green).

We now consider two additional maps that offer further insights into the gap between social and management tolerance. Figure 4 illustrates the difference between believed and actual management tolerance, which speaks to the respondents’ local knowledge of management policy. And Fig. 5, by mapping the difference between preferred and believed tolerance, reflects the local awareness of any misalignment between social and management tolerance.

From these maps, a few interesting results emerge. First, while we might expect residents in grizzly bear-occupying areas to be most familiar with actual management practices, estimates indicate these areas tend to have larger overestimates of management tolerance (darker shades in Fig. 4). This translates to grizzly areas being relatively unaware that management tolerance does not align with local social tolerance (lighter and red shades in Fig. 5). The story differs for the West Coast and Pacific Northwest regions. Estimates suggest these areas have relatively more knowledge of current grizzly management with perceptions about current practice closely aligning with actual management (lighter shades in Fig. 4). Consequently, the West Coast and Pacific Northwest regions are more aware that management tolerance does not align with their preference for greater tolerance (darker shades in Fig. 5).

We repeat this exercise for the more severe and less common threat and injury encounters. For succinctness, we provide the estimates and maps in Supplementary Tables 4–9; Supplementary Figs. 1–3. However, we note some findings that differ from the property encounter results. As with property encounters, local social tolerance for the risk of threat and injury encounters is universally greater than management practice (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 4). But unlike property encounters, the misalignment is smallest in the Rocky Mountain and Great Lakes regions, and largest in the coastal areas. Also, estimates indicate that grizzly-occupying areas are relatively more knowledgeable about management tolerance for the risk of threat and injury encounters (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 5), which contrasts with these areas being relatively less knowledgeable about property encounters. For both threat and injury encounters, estimates suggest that grizzly areas mistakenly believe the locally desired social tolerance towards grizzly bears is closely reflected by management policy (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 6), a result that is common to the property damage setting.

Discussion

The success of predator recovery hinges on effectively managing human-wildlife conflict in communities reoccupied by native species. Social tolerance or social carrying capacity plays an important role in managing human-wildlife conflicts. By 2070, human-wildlife overlap is expected to increase in over 55% of terrestrial lands, increasing the chances for human-wildlife conflict15; despite this, and arguments made in the human dimensions of wildlife literature29, modern approaches to wildlife management often overlook systematic measurement and integration of social tolerance, favoring top-down, one size fits all, guidelines applied to diverse local contexts. Herein, to the best of our knowledge, we undertake a novel approach to measure social tolerance of human-wildlife encounters and illustrate how it can inform local adaptive wildlife management.

Focusing on grizzly bears, our study finds that the social tolerance of the risks associated with human-grizzly encounters is generally much larger than the tolerance outlined by the top-down, federal management guidelines. Further, results show significant variation in social tolerance across local and regional areas, which highlights the potential benefits of locally tailored approaches to wildlife management. Equipped with this type of information, wildlife managers can better navigate the competing interests that affect recovery and management efforts. For example, a better understanding of local carrying capacity can allow more effective communications about current actions as well as more appropriate and intentional adjustments to management policies.

For the grizzly-occupying states of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, we find that residents believe that agency actions mirror their preferences when the local community is more tolerant of potential human-grizzly interactions. To illustrate, public petitions demanded relocation, not removal, in three recent cases: the well-known Yellowstone grizzly “Blaze” in 2015, grizzly 1057 (offspring of the famous grizzly 399) in 2022, and a West Yellowstone female with a cub in 2023. Yet, all three bears were euthanized35,36,37. These episodes demonstrate the potential for conflict when there is a gap between local risk tolerance and management action. Incorporating quantitative estimates of social tolerance would allow managers to select non-lethal responses (or justify lethal ones) with improved community expectation alignment.

Grizzly bears are charismatic, threatened, and reside on federal public lands, which makes them relevant beyond areas inside and nearby grizzly habitat areas. For such species, management may consider the tolerance of all people (local and non-local) who benefit from wildlife conservation. Current practices, such as public comments and town halls, are often biased towards the loudest voices, potentially overlooking important local and non-local perspectives. Such practices operate in tandem with the human dimensions of wildlife literature that offer managers tools for decision-making22,38,39. Our work contributes to this toolkit. While local and non-local preferences may not be weighted equally, both may be relevant. Incorporating broader views could improve the overall alignment of management actions with public sentiment.

Mapping local and non-local wildlife management preferences emphasizes the importance of representing social tolerance in a comparable fashion to the current management variables, such as ecological or biological carrying capacity. Understanding preferences for wildlife management can also help target predator recovery efforts more intentionally. While habitat suitability is often well-understood, social acceptance may be less predictable. Using social tolerance, as measured by the method employed in our paper, managers can compare biological carrying capacity more directly with social tolerance rather than relying on indirect inferences. For example, informally discussed recovery efforts in the Sierra Nevada (California) may require more management tolerance than similar efforts around the Mogollon Rim (Arizona) due to differing levels of local support. This information is important when prioritizing conservation projects, as it impacts management costs and the likelihood of success. By evaluating these trade-offs, managers can improve the outcomes of species restoration programs and resource allocation.

Introducing social carrying capacity and our preference elicitation technique provides a management tool with broader applicability beyond wildlife decisions. By measuring national preferences and understanding current management strategies, adaptations to management strategies can be better informed with the locally dependent social carrying capacity. For example, some areas where a belief and preference of policy may prove useful are wildfire mitigation, pipeline approvals, or environmental crises like the Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone and Great Lakes Algal Blooms. By incorporating human risk perceptions and social preferences into environmental policymaking, our technique makes nature-based solutions ecologically effective and socially acceptable. Thus leading to more successful implementation and greater overall impact in various environmental initiatives39. While local preferences remain valuable and are perhaps the most important for successful recovery40, incorporating the views of national constituents can enhance decision-making, especially when managing a wildlife population or alternative resource on federal lands. Our proposed social tolerance measurement should be seen as an additional tool for managers, complementing existing practices like town halls and online forums, to measure public opinion directly.

Methods

To facilitate grizzly bear recovery, federal and state agencies collaborated to formulate and approve “Interagency Grizzly Bear Guidelines” that established standard management responses for conflicts of varying severity41. While the guidelines are dated, they remain the authoritative source governing management responses to “nuisance” grizzly bears. Summarized in Supplementary Table 1, the guidelines are organized around the severity and frequency of grizzly bear encounters, which determine the appropriate response by management. In our survey, we only asked about individual preferences for adult female grizzly bears due to their critical role in population growth and expansion. Grizzly bear encounters are classified into one of three types, with human injury having the greatest degree of severity:

-

Property: The bear depredates livestock or accesses secured unnatural food materials (human and livestock foods, garbage, gardens, and game meat).

-

Threat: The bear has displayed aggressive (not defensive) behavior toward humans and/or caused minor human injury.

-

Injury: The bear has caused substantial human injury or loss of human life.

Depending on the type and frequency of the encounter, the guidelines of direct management are to take one of the following two responses:

-

Relocation: The bear is captured and moved away, typically 40−90 miles from the encounter location.

-

Removal: The bear is captured and euthanized (i.e., killed).

An important element for management (and this study) is that, for each type of encounter, the number of accumulated encounters by a specific bear determines the appropriate response. For example, one property encounter by an adult female grizzly bear leads to relocation, while the third property encounter will lead to removal.

Using this framework, we designed a survey to measure individual tolerance for the risk of grizzly bear encounters, which can be aggregated to reflect social tolerance or carrying capacity. The survey has four sections—warm-up, background, management, and demographic. After receiving informed consent, the warm-up section elicited knowledge and attitudes towards national parks and wildlife management. Next, a background section provided baseline information about the framework used for grizzly bear management. This section describes the types of encounters, and an incident count (threshold) of each type would trigger relocation or removal. The current threshold in the guidelines was not shared, just that thresholds exist.

The management section elicited respondents’ preferred level of tolerance and their beliefs about the actual tolerance of management for adult female bears. We follow a larger literature that elicits stated preferences to estimate social preferences42, such as preferences for environmental health risks43, recovery of threatened species44, forest management45, and water quality46. In our survey, we frame tolerance within the grizzly bear management guidelines. We elicit the respondent’s preferred tolerance by asking “For each type of encounter, give your preferred removal threshold (if any) in an ideal policy. In other words, what do you think should be the number of encounters that cause a bear to be removed?” Similarly, to elicit the respondent’s beliefs about actual tolerance by management, we ask “For each type of encounter, give your best guess of the current policy’s removal threshold. In other words, what do you think is the current number of encounters that cause a bear to be removed?” Therefore, this section provides data on individual beliefs about preferred and actual management tolerance, with higher (lower) thresholds revealing greater (lower) tolerance for the risk of grizzly bear encounters. We compare respondent beliefs about preferred and actual tolerance to the objective tolerance defined by the thresholds outlined in the Interagency Grizzly Bear Guidelines.

The follow-up section asks respondents to indicate their experience with grizzly bear habitat, grizzly bear encounters, and any risk reduction actions taken to mitigate the risk of grizzly bear encounters. The survey concluded with a demographic section that collected socioeconomic information about age, income, sex, political affiliation, education, and state of residence. The full survey instrument, including specific question wording, is provided in Section C in the SI.

The sample, protocols, and instrument were reviewed and determined exempt by the University of Wyoming’s Institutional Review Board (#20230425TC03550). Respondents (N = 1157) were recruited online by Qualtrics with quotas to achieve a more representative sample. Qualtrics maintains a nationally representative database of respondents and employs quality control measures, including attention check questions and automated detection methods (e.g., straight-lining patterns, completion time) to filter responses. Participation in our survey was restricted to adults (18+) in the United States. Qualtrics estimated distributions of 30% 18−34 years old, 32% 35−54 years old, and 38% 55+ years old for age, and 48% male and 52% female for sex. To facilitate habitat-specific analysis, we follow the literature [e.g. ref. 47] and oversample the states most affected by grizzly bear encounters and grizzly bear management—Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. The disproportionately large sample (N = 307) better ensures statistical power for the location-specific analysis of grizzly-habitat states. A comparison of sample and population characteristics is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

To consider the spatial distribution of tolerance, we merge the primary data from the survey with secondary data from multiple sources, including the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Land Cover Database. A complete list of variables and sources for secondary data is given in Supplementary Table 2. We estimate a model of individual preferences and beliefs for the number of encounters that trigger removal. Estimated coefficients are used to conduct out-of-sample zip code-level predictions of beliefs and desires, which are mapped for the contiguous United States.

Specifically, we use an empirical model to generate out-of-sample zip-code-level predictions for believed and preferred tolerance for grizzly bear encounters with a more refined spatial characterization. To do so, we use the following model:

in which Di,j is respondent i’s stated belief/preference for the number of encounters that trigger management action, Xi.j is a vector of individual-specific characteristics (e.g., age, income, education, etc.), Zi,j is a vector of location-specific characteristics (e.g., distance to grizzly habitat, region, percentage of total land designated cropland, pastureland, grassland, developed land, etc.) associated with respondent i’s zip-code j, α is the constant term, and εi,j, is an idiosyncratic error term.

There are two important things to note about Equation (1). First, we employ a censored Poisson model because Di,j captures count data that is censored from above and shows no overdispersion; thus, the Poisson model is preferred to the Negative Binomial model. Second, we estimate two models— preferred tolerance for removal (model 1) and believed (model 2) tolerance for removal. Specific coefficient estimates are reported in Supplementary Tables 4–9 for model 1 and Supplementary Tables 10–15 for model 2.

Using zip-code-level social and demographic (\({\bar{X}}_{j}\)), geographic and landscape characteristics (\({\bar{Z}}_{j}\)) outlined above, we expand our results from the in-sample estimation to conduct an out-of-sample prediction (\({\hat{D}}_{i,j}\)) of stated beliefs/preferences for each zip code j in the contiguous United States. Note, if zip-code specific data in aggregated form are missing (either \({\bar{X}}_{j}\) or \({\bar{Z}}_{j}\)), we exclude the zip-code from predictive maps. Also, given that property encounters account for most encounters, we presented the results for the tolerance for property counters (Figs. 3–5). The results for human threat are provided in Supplementary Figs. 1–3 and injury encounters in Supplementary Figs. 4–6.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The cleaned data and all replication materials generated by and used for analysis in the current study are at: https://osf.io/fqmhp.

References

Svenning, J.-C. et al. Science for a wilder anthropocene: synthesis and future directions for trophic rewilding research. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 898–906 (2016).

Smith, D. W., Peterson, R. O. & Houston, D. B. Yellowstone after wolves. BioScience 53, 330–340 (2003).

Simon, M. A. et al. Reverse of the decline of the endangered Iberian lynx. Conserv. Biol. 26, 731–736 (2012).

Wilting, A. et al. Planning tiger recovery: understanding intraspecific variation for effective conservation. Sci. Adv. 1, e1400175 (2015).

Coogan, S. C. et al. Towards grizzly bear population recovery in a modern landscape. J. Appl. Ecol. 56, 93–99 (2018).

Ditmer, M. A. et al. Predicting dispersal and conflict risk for wolf recolonization in Colorado. J. Appl. Ecol. 60, 2327–2339 (2023).

Connolly, E. & Nelson, H. Jaguars in the borderlands: multinatural conservation for coexistence in the anthropocene. Front. Conserv. Sci. 4, 851254 (2023).

Tordiffe, A. S. et al. The case for the reintroduction of cheetahs to India. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 480–481 (2023).

Ripple, W. J. et al. Status and ecological effects of the world’s largest carnivores. Science 343, 1241484 (2014).

Stier, A. C. et al. Ecosystem context and historical contingency in apex predator recoveries. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501769 (2016).

Dickman, A. J., Macdonald, E. A. & Macdonald, D. W. A review of financial instruments to pay for predator conservation and encourage human–carnivore coexistence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13937–13944 (2011).

Nyhus, P. J. Human–wildlife conflict and coexistence. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 41, 143–171 (2016).

Abrahms, B. Human-wildlife conflict under climate change. Science 373, 484–485 (2021).

Abrahms, B. et al. Climate change as a global amplifier of human–wildlife conflict. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 224–234 (2023).

Ma, D. et al. Global expansion of human-wildlife overlap in the 21st century. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp7706 (2024).

Can, Ö. E., D’Cruze, N., Garshelis, D. L., Beecham, J. & Macdonald, D. W. Resolving human-bear conflict: a global survey of countries, experts, and key factors. Conserv. Lett. 7, 501–513 (2014).

Schwartz, C. C., Haroldson, M. A. & White, G. C. Hazards affecting grizzly bear survival in the greater Yellowstone ecosystem. J. Wildlife Manag. 74, 654–667 (2010).

Benson, J. F. et al. The ecology of human-caused mortality for a protected large carnivore. Proceed. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2220030120 (2023).

Brenner, L. J. & Metcalf, E. C. Beyond the tolerance/intolerance dichotomy: incorporating attitudes and acceptability into a robust definition of social tolerance of wildlife. Hum. Dimens. Wildlife 25, 259–267 (2020).

Carlson, S. C., Dietsch, A. M., Slagle, K. M. & Bruskotter, J. T. Effect of semantics in the study of tolerance for wolves. Conserv. Biol. 37, e14003 (2023).

Gore, M. L. & Kahler, J. S. Gendered risk perceptions associated with human-wildlife conflict: Implications for participatory conservation. PLoS ONE 7, e32901 (2012).

Bruskotter, J. T. & Wilson, R. S. Determining where the wild things will be: using psychological theory to find tolerance for large carnivores. Conserv. Lett. 7, 158–165 (2014).

O’Bryan, C. J. et al. The contribution of predators and scavengers to human well-being. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 229–236 (2018).

Soga, M. & Gaston, K. J. Towards a unified understanding of human–nature interactions. Nat. Sustain. 5, 374–383 (2022).

Carter, N. H., Shrestha, B. K., Karki, J. B., Pradhan, N. M. B. & Liu, J. Coexistence between wildlife and humans at fine spatial scales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 15360–15365 (2012).

Prugh, L. R. et al. Fear of large carnivores amplifies human-caused mortality for mesopredators. Science 380, 754–758 (2023).

Leighton, G. R., Froneman, W., Serieys, L. E. & Bishop, J. M. Trophic downgrading of an adaptable carnivore in an urbanising landscape. Sci. Rep. 13, 21582 (2023).

Sage, A. H., Hillis, V., Graves, R. A., Burnham, M. & Carter, N. H. Paths of coexistence: Spatially predicting acceptance of grizzly bears along key movement corridors. Biol. Conserv. 266, 109468 (2022).

Nesbitt, H. K. et al. Human dimensions of grizzly bear conservation: the social factors underlying satisfaction and coexistence beliefs in Montana, USA. Conserv. Sci. Practice 5, e12885 (2023).

Olson, E. R. & Goethlich, J. Changing the tolerance of the intolerant: does large carnivore policy matter? Animals 14, 2358 (2024).

Hardin, G. Cultural carrying capacity: a biological approach to human problems. Carrying Capacity Netw. Focus 2, 16–23 (1992).

Seidl, I. & Tisdell, C. A. Carrying capacity reconsidered: from Malthus’ population theory to cultural carrying capacity. Ecol. Econ. 31, 395–408 (1999).

Slagle, K., Bruskotter, J. T., Singh, A. S. & Schmidt, R. H. Attitudes toward predator control in the United States: 1995 and 2014. J. Mammal. 98, 7–16 (2017).

Young, J. K., Hammill, E. & Breck, S. W. Interactions with humans shape coyote responses to hazing. Sci. Rep. 9, 20046 (2019).

Zuckerman, L. Euthanization Of Mother Grizzly At Yellowstone Prompts Outrage. https://www.reuters.com/article/business/environment/euthanization-of-mother-grizzly-at-yellowstone-prompts-outrage-idUSKCN0QJ26Z/. (2015).

Bella, T. Grizzly Bear That Had Killed A Woman Is Euthanized After Breaking Into A House. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2023/09/07/grizzly-bear-home-attack-euthanized-yellowstone/ (2023).

Baitinger, B. Headless, Pawless Grizzly Left in River by Montana Wildlife Officials Stirs Outrage. https://www.eastidahonews.com/2024/07/headless-pawless-grizzly-left-in-river-by-montana-wildlife-officials-stirs-outrage/ (2024).

Pooley, S., Bhatia, S. & Vasava, A. Rethinking the study of human–wildlife coexistence. Conserv. Biol. 35, 784–793 (2021).

Bockarjova, M., Botzen, W. W., Bulkeley, H. A. & Toxopeus, H. Estimating the social value of nature-based solutions in European cities. Sci. Rep. 12, 19833 (2022).

Ingeman, K. E. et al. Glimmers of hope in large carnivore recoveries. Sci. Rep. 12, 10005 (2022).

Mealey, S. P. Interagency Grizzly Bear Guidelines. Tech. Rep., Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee. https://npshistory.com/publications/wildlife/interagency-grizzly-bear-guidelines.pdf (1986).

Johnston, R. J. et al. Contemporary guidance for stated preference studies. J. Assoc. Environ. Resource Econ. 4, 319–405 (2017).

Adamowicz, W., Dickie, M., Gerking, S., Veronesi, M. & Zinner, D. Household decision making and valuation of environmental health risks to parents and their children. J. Assoc. Environ. Resource Econ. 1, 481–519 (2014).

Boxall, P., Adamowicz, W. L. V. & Moon, A. Complexity in choice experiments: choice of the status quo alternative and implications for welfare measurement*. Australian J. Agric. Resource Econ. 53, 503–519 (2009).

Horne, P., Boxall, P. C. & Adamowicz, W. L. Multiple-use management of forest recreation sites: a spatially explicit choice experiment. Forest Ecol. Manag. 207, 189–199 (2005).

Bateman, I. J., Keeler, B., Olmstead, S. M. & Whitehead, J. Perspectives on valuing water quality improvements using stated preference methods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2217456120 (2023).

Kalton, G. Methods for oversampling rare subpopulations in social surveys. Survey Methodology 35, 125–141 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Frank van Manen and Yuta Masuda for helpful comments during the writing process. This project received partial support under the National Science Foundation’s Establish Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR NSF Award #2149105) award and the Lowham fund at the University of Wyoming.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (Chandler Hubbard, Ian M. Fletcher, Todd L. Cherry, David Finnoff, and Jacob Hochard) designed and performed research; analyzed, collected, and assembled the data; and contributed to writing the paper in an equal manner.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Ida Djenontin and Martina Grecequet. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hubbard, C., Fletcher, I.M., Cherry, T.L. et al. The public overestimates and prefers greater tolerance for grizzly bear encounters than defined by the United States management guidelines. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1022 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02969-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02969-9