Abstract

Polar Lows are intense weather systems that drive strong exchanges of momentum, heat, and moisture between the atmosphere and ocean, potentially affecting ocean conditions. However, their small scale and short duration make them poorly represented in climate numerical models. Here, we use sensitivity experiments to assess the impacts of Polar Lows on the global ocean. Their effects vary regionally, depending on both Polar Low frequency and ocean structure. In the Northeast Atlantic, wind associated with Polar Lows enhances oceanic heat loss and vertical mixing, while precipitation has a minor opposing effect. In the Labrador and Irminger Seas, both wind and precipitation contribute similarly to horizontal heat transport, and their opposing effects largely cancel, reducing the net impact. In the Southern Hemisphere, despite frequent Polar Lows, strong background winds minimize their influence. These findings highlight regional variability in Polar Low impacts and offer insights for improving their representation in climate models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polar lows (PLs) are mesoscale cyclones, ranging from 200 to 1000 km in diameter, that form over the subpolar seas during the winter months1,2. They are often accompanied by severe weather, such as gale-force winds, heavy snow showers, and intense blizzard events, posing a serious threat to the coastal communities and offshore activities in the polar region. Due to the large air-sea temperature difference and strong wind, the air-sea heat flux associated with PLs can be up to 1000 Wm−2, significantly impacting the underlying ocean as well as the large-scale circulations3,4,5.

Three of the Earth’s major ocean circulations–the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), the Kuroshio/Oyashio current system, and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC)6,7,8–are significantly affected by the air-sea energy and mass fluxes in subpolar seas, including the North Atlantic, North Pacific, and Southern Ocean. For instance, strong air-sea temperature gradients in the North Atlantic Ocean in winter drive the warm northward flow sink to form the deep southward return flow of AMOC9,10,11. In the Kuroshio-Oyashio current system, in addition to deep ocean convection driven by air-sea temperature gradients, diapycnal mixing in the Kuroshio-Oyashio confluence region also contributes to the ventilation of the abyssal ocean12,13. In contrast to thermohaline-driven ventilation in the Northern Hemisphere, the ACC ventilates the ocean through a wind-driven upwelling process sustained by Ekman divergence under the influence of the Southern Hemisphere’s prevailing westerly winds14. Consequently, accurately describing the air-sea turbulent fluxes in subpolar seas is critical for climate simulations, as these abyssal ocean ventilations play a fundamental role in sustaining ocean circulation and regulating Earth’s climate system15,16. However, due to their small scale and short lifetime, the energy and mass fluxes associated with PLs in these regions are significantly underrepresented in current climate models, potentially resulting in biases in climate predictions. More importantly, these regions are the main breeding grounds for PLs17 due to their pronounced baroclinicity arising from substantial zonal contrasts in surface temperatures5,18,19.

Given that the gale-force winds and heat losses associated with PLs can enhance ocean ventilation—and that PL activity coincides temporally and spatially with ventilation processes—a naturally arising question for the PL community:

-

To what extent do PL-associated perturbations influence deep ocean ventilation and, potentially, large-scale ocean circulation?

-

How does the deficiency of PL-associated energy and mass fluxes in climate models limit confidence in their predictions?

To address this question, a pioneering study examined the impact of PLs in the Northeast Atlantic by parameterizing the PL-associated wind, i.e., compensating for the underestimated wind speed associated with PLs5. The results show that PLs enhance the simulated depth and frequency of deep convection in the Nordic Seas. This, in turn, increases northward heat transport into the region and southward deep-water export through the Denmark Strait. To shed light on this scientific question, we quantify the influence of PLs on oceanic circulation through sensitivity experiments. Differing from5, in this study, (1) we use the high-resolution ERA5 data with ~31 km horizontal resolution to force the ocean model, instead of ERA40 with lower resolution, which is reported to reproduce >80% of the PLs20, (2) instead of parameterizing the PL-associated wind, we filter the PL-associated energy and mass fluxes (see Method section) to purely quantify the PL influences, considering the good quality of the ERA5 data, (3) we quantify the influence of PL-associated turbulent fluxes and precipitation separately (see Method section), where the influence of PL-associated precipitation was not considered in ref. 5, and (4) we focus on the global ocean, instead of only the Nordic Seas.

Results

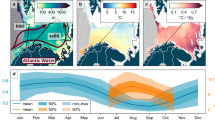

Spatial distribution of polar lows

PLs are observed across all ocean basins at high latitudes (Fig. 1a). In the Southern Hemisphere, most PLs develop between 50° and 60°S, primarily over the ACC, clustering in the Southeast Pacific and the Southern Indian Ocean. The Northern Hemisphere has three main PL breeding grounds: the Labrador and Irminger Seas, the Northeast Atlantic Ocean, and the Northwest Pacific. PLs form across a wide latitude range, from 80°N in the Northeast Atlantic to 40°N in the Northwest Pacific. The highest density of PL activities (amount of PL time steps within 1° × 1° grid) occurs in the Northeast Atlantic and the Northwest Pacific, where their average annual occurrence exceeds 85 days. In contrast, PLs occur for an average of 30 days per year in the Irminger Sea and 70 days per year in the Labrador Sea.

a The spatial distribution of PL activity density: number of PL occurrence hours within a 1° × 1° grid from 2000–2020. The PLs dataset is taken from Stoll18. b The mean of PL-induced anomalies in 10-m wind speed during winter (DJF in the Northern Hemisphere and JJA in the Southern Hemisphere). c Anomalies in precipitation induced by PLs during winter (DJF in the Northern Hemisphere and JJA in the Southern Hemisphere).

The average wind speed anomaly induced by PLs (see the Supplementary Methods for the definition of PL-associated wind and precipitation anomaly) differs significantly between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres (Fig. 1b). In the Northern Hemisphere, PL contributes to the mean wind speed increase by up to 0.5 ms−1 in PLs clusters’ regions, whereas the impact of PLs in the Southern Hemisphere is minimal. One possible explanation is that PLs are more scattered in the Southern Hemisphere. Additionally, since PLs primarily occur within the Antarctic westerlies, where strong winds are prevalent, their impact may be less pronounced.

The average precipitation anomaly induced by PLs is also more pronounced in the PLs cluster regions of the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 1c). The largest PL-associated precipitation is observed in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean, where average precipitation increases by 17%. In the Labrador and Irminger Seas and the Northwest Pacific, PLs contribute to a 10 and 13% rise in precipitation, respectively. In contrast, in the Southern Hemisphere, PLs lead to a more modest 5% increase in average precipitation.

Impact of PLs on global ocean

To assess the cumulative influence of PLs, the diagnostic analysis focuses on the final five years of the simulations, comprising four experiments: CTRL (baseline), noPL (PLs removed), PLwater (PL-related wind forcing suppressed), and PLwind (PL-related precipitation suppressed), as detailed in the section “Methods”. Comparison of our simulated sea ice fraction, sea surface temperature (SST), and ocean heat content with previous studies21,22,23 shows broad agreement, supporting the reliability of our simulations. Notably, the most pronounced effects of PLs are observed in the North Atlantic, with detailed figures provided in the Supplementary Information.

Mixed-layer depth

The mixed-layer depth serves as a key indicator of open-ocean convection24. In our simulation, the climatological distribution of mixed-layer depth is broadly consistent with previous studies25,26,27,28, but the absolute values are systematically shallower. This discrepancy arises because the mixed-layer depth in this study is defined as the depth where the density increases by 0.01 kgm−3 relative to that at 10 m. In contrast, other studies use a threshold of ~0.03 kgm−3. Variations in mixed-layer depth reflect the extent to which localized PLs influence the underlying ocean. For example, the strong winds generated by PLs enhance air-sea heat flux exchange and vertical mixing, leading to ocean cooling and increased instability in the water column, which deepens the mixed layer. Conversely, precipitation from PLs stabilizes the water column and shoals the mixed layer by reducing the density of surface waters.

The impact of PLs on the depth of the ocean mixed layer is primarily concentrated in their breeding grounds, with some extension toward lower latitudes (Figs. 1 and 2). The winter mixed-layer depth in the Labrador and Irminger Seas is most affected by PLs. In this area, PL-associated precipitation (PLwater) shoals the mixed layer depth by up to 52 m (Fig. 2c). In contrast, PL-associated wind (PLwind) deepens the mixed layer depth by up to 76 m (Fig. 2d). These opposing impacts result from distinct underlying mechanisms, as detailed above. By comparing the magnitude of the differences caused by PL-associated precipitation (PLwater) and winds (PLwind), it is evident that PL-associated wind plays a dominant role in affecting the mixed-layer depth in the Labrador and Irminger Seas. When both PL-associated turbulent fluxes and precipitation are taken into account (CTRL, Fig. 2b), the maximum increase of mixed layer depth is 47 m compared to that from experiment noPL. It is worth noting that although the maximum intensity of PL-associated impacts does not occur in this region (Fig. 1b, c), the mixed-layer depth is most significantly affected here. This is primarily because vertical mixing in this area is largely driven by high winter surface heat losses, rendering it particularly sensitive to PL forcing29.

a Climatological winter (DJF) mixed-layer depth of the Northern Hemisphere from 2016 to 2020 in the CTRL simulation. Climatological winter difference between b CTRL and noPL (CTRL-noPL); c PLwater and noPL (PLwater-noPL); d PLwind and noPL (PLwind-noPL). Sea ice edge is indicated by a purple contour.

In the Northeast Atlantic Ocean, PLs also have a pronounced impact on the mixed-layer depth, which closely corresponds to variations in surface heat fluxes (Fig. 3). Under the influence of PLs, the mixed-layer depth increases by up to 18 m in the open ocean, while it decreases by as much as 15 m near the sea ice edge (Fig. 2b). These changes are associated with enhanced heat losses (13 Wm−2) in the open ocean and reduced heat losses (8 Wm−2) near the sea ice edge (Fig. 3b). A similar pattern is observed in the PLwind simulation but with pronounced reductions in heat losses (11 Wm−2) near the sea ice edge (Figs. 2d and 3d). In contrast, the PL-associated precipitation (PLwater) increases the mixed-layer depth near the ice cover edge (Fig. 2c), coinciding with increased heat losses (5 Wm−2) in that region (Fig. 3c). The changes in surface heat fluxes are likely driven by the growth or melting of sea ice along the edge (Supplementary Fig. S4), which is closely linked to changes in ocean heat content, as detailed in section “Ocean heat content and heat transport”. In the CTRL and PLwind simulations, sea ice expands near the ice edge, while it melts in the PLwater simulation. The growth of sea ice hinders heat losses from the ocean, leading to a shallower mixed-layer, whereas the melting of sea ice has the opposite effect, deepening the mixed-layer. Generally, the impact of PL-associated wind on the ocean is consistent with earlier studies5,30, which demonstrate that intense winds exert a stronger influence on mixed-layer depth by modulating heat fluxes, vertical mixing, and, consequently, enhancing deep convection. The impact of PLs on the Northwest Pacific and Southern Oceans is minimal, with changes in mixed-layer depth generally less than 5 m (Supplementary Fig. S5).

a Climatological winter (DJF) surface heat fluxes of the Northern Hemisphere from 2016 to 2020 in the CTRL simulation. Climatological winter difference between b CTRL and noPL (CTRL-noPL); c PLwater and noPL (PLwater-noPL); d PLwind and noPL (PLwind-noPL). Sea ice edge is indicated by a purple contour.

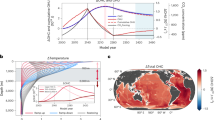

Potential temperature and Brunt–Väisälä frequency

PL-associated wind and precipitation exert opposing influences on ocean density and, consequently, on stratification (Supplementary Fig. S6). PL-associated wind enhances surface evaporation, increasing density, whereas PL-associated precipitation freshens the surface layer, reducing both salinity and density. The effects of PLs on ocean salinity are further redistributed by vertical mixing. The salinity response is most pronounced in the Northeast Atlantic and the Labrador–Irminger Seas, where PL events are strong and frequent. In other ocean basins, these impacts are weaker. The thermal effects of PLs are also strongest in the Northeast Atlantic and the Labrador–Irminger Seas. In these regions, the thermal response is influenced by both convection and advection, providing a clearer signal of PL-induced deep ocean changes. The most pronounced impact of PLs on ocean potential temperature is observed in the Northeast Atlantic, extending to depths of 800 m (the navy line in Fig. 4a). In this region, the presence of PLs leads to a cooling of ~0.1 °C in the upper 800 m of the ocean during the winter months. The second most pronounced effect is observed in the Labrador and Irminger Seas, where PLs cause a slight cooling of around 0.03 °C in the upper 600 m of the ocean (Fig. 4b). PLs have a weaker effect on ocean potential temperature in the Northeast Pacific and Southern Ocean, consistent with their minimal influence on mixed-layer depth (Fig. 4c–e).

Vertical profiles of (Top) mean potential temperature (purple dashed line) and (Bottom) mean Brunt–Väisälä frequency (purple dashed line) over the last 5 years of simulation (2016–2020) for different regions (see Fig. 1): a, f Northeast Atlantic Ocean; b, g Labrador and Irminger Sea; c, h Northwest Pacific; d, i Southeast Pacific; e, j South Indian Ocean. Differences among experiments in potential temperature and Brunt–Väisälä frequency are shown for CTRL minus noPL (navy line), PLwind minus noPL (orange line), and PLwater minus noPL (sky blue line).

Despite their opposing effects on the ocean, PL-associated wind and precipitation do not always leave a uniform imprint on the ocean. In the Northeast Atlantic, the average potential temperature increases to ~5.2 °C at 200 m from the surface (3.9 °C) and then gradually decreases to 1 °C between 200 and 800 m (the dashed line in Fig. 4a). PL-associated wind (PLwind) cools the upper 700 m of the ocean, while increasing the potential temperature of the sea water at depths of 700–900 m (the orange line in Fig. 4a). This pattern is mainly driven by enhanced vertical mixing, which can be shown from the variation of the Brunt–Väisälä frequency. The changes in ocean stratification induced by the PL-associated wind (PLwind) extend to 800 m (Fig. 4f ), closely aligning with the depth of potential temperature variations (Fig. 4a). The pronounced heat losses associated with PL-induced winds lead to surface cooling and destabilization of the upper ocean. At the same time, strong winds enhance vertical mixing, deepening the mixed layer. As a result, the upper 600 m of the ocean cool, while the 600–1000 m layer experiences slight warming compared to the noPL simulation. In contrast, when the PL-associated freshwater is introduced at the surface (PLwater), it stabilizes the upper ocean, suppressing vertical mixing. As a result, the upper 600 m warms slightly due to the accumulation of surface heat transported horizontally (discussed in section “Ocean heat content and heat transport”), while the 600–1000 m layer cools relative to the noPL simulation, due to the reduced vertical mixing. When both PL-associated wind and precipitation are included, the overall impact is largely driven by the turbulent fluxes. However, PL-induced precipitation slightly reduces the magnitude of this impact compared to the experiment that considers only PL-associated wind.

In the Labrador and Irminger Seas, the ocean potential temperature increases when only the PL-associated wind effects are considered (PLwind), but decreases when only the PL-associated precipitation effects are accounted for (PLwater; Fig. 4b). The impact of PL-associated wind (PLwind) on ocean stratification extends down to approximately 400 m, whereas variations in potential temperature reach depths of around 1800 m. Similarly, the impact of PL-associated precipitation (PLwater) extends to more than 1400 m. This suggests that, in addition to the vertical mixing driven by PL, oceanic horizontal advection also plays an important role. This also helps explain why the ocean becomes unexpectedly warmer in the PLwind simulation but cooler in the PLwater simulation. When the full impact of PLs is considered, the overall effect results in slightly cooler ocean temperatures.

The impact of PLs in the Northwest Pacific is less pronounced (Fig. 4c, h) compared to the Atlantic Ocean, despite the distinct cluster of PLs in this region (Fig. 1). A likely explanation is that PL-induced heat losses represent only a small fraction of the annual average heat losses (Fig. 3a), which results in a minimal sensitivity of vertical mixing to PLs in this region. Additionally, vertical mixing in the Northwest Pacific is also influenced by the Oyashio Current, which transports cold Arctic waters to the region, replenishing it during ocean convection. As a result, PL-associated effects on the ocean are weaker in this region. The most negligible impact of PLs is observed in the Southern Ocean, where the annual average wind speed exceeds 10 ms−1. In this high-wind environment, the influence of PLs is largely diminished.

Ocean heat content and heat transport

The modulation of PLs on SST ranges from −0.7 to 0.7 °C (see Supplementary Fig. S7), exhibiting distinct regional patterns. The most extensive effects occur in the subpolar gyre region (50°N–65°N, 40°W–10°W), where the effects reach magnitudes comparable to those induced by global warming31. Specifically, in experiments considering only PL-associated wind (PLwind), the averaged SST increases by 0.25 °C in the subpolar gyre region, whereas in experiments considering only PL-associated precipitation (PLwater), it decreases by 0.1 °C.

In the Northeast Atlantic Ocean, when the full impact of PLs is considered (CTRL), the average upper ocean heat content decreases by 4 × 108 GJ (Fig. 5b). This corresponds to roughly a 1% change, which, although modest in magnitude, is statistically significant. Consequently, the basin-scale SST response is weak. However, localized cooling of up to 0.3 °C occurs along the sea ice edge (see Fig. S7a). Furthermore, the isolated impact of PL-associated wind (PLwind) leads to a 4.25 × 108 GJ decrease (Fig. 5d), while PL-associated precipitation (PLwater) causes an increase of 0.5 ×108 GJ (Fig. 5c). In total, the effect of PL-associated wind on ocean heat content far outweighs that of PL-associated precipitation in this region. The decrease in ocean heat content in the PLwind simulation is attributed to enhanced heat losses from the ocean due to PL-associated wind. In contrast, the increase in ocean heat content in the PLwater simulation is associated with enhanced horizontal heat transport (Table 1) across the Iceland-Scotland Ridge (cross-section 1 in Fig. 5), which serves as the primary gateway for heat entering the Northeast Atlantic Ocean.

a Climatological winter (DJF) upper ocean heat content (700 m) of the Northern Hemisphere from 2016 to 2020 in the CTRL simulation. Climatological winter difference between b CTRL and noPL (CTRL-noPL); c PLwater and noPL (PLwater-noPL); d PLwind and noPL (PLwind-noPL). Differences significant at the 95% confidence level (T-test) are indicated by a green contour. Sea ice edge is indicated by a purple contour. The black line is cross-section 1, and the gray line is cross-section 2.

In the Labrador and Irminger Seas, the average upper ocean heat content decreases by 1.25 × 108 GJ in the CTRL simulation (Fig. 5b) and by 2 × 108 GJ in the PLwater simulation (Fig. 5c). However, in the PLwind simulation, the heat content increases by 2.5 × 108 GJ (Fig. 5d). The unexpected ocean heat content increase in the PLwind simulation is attributed to changes in internal ocean heat transport. An additional 0.07 PW (28% more) of heat is advected into the Labrador and Irminger Seas through cross-section 2, whereas in the PLwater simulation, a reduction of 0.03 PW of heat crosses the same section. When considering the full impact of PLs, an additional 0.03 PW of heat (12% more) is transported into the Labrador and Irminger Seas. While this heat is not sufficient to offset the direct heat losses caused by PLs, it largely replenishes the heat lost in the region. This enhanced heat transport induced by the PLs simulation highlights the broader role of small-scale atmospheric forcing in modulating ocean heat content and large-scale circulation. Our results are consistent with previous studies that emphasize the sensitivity of oceanic heat transport to atmospheric resolution. For instance, ref. 32 used a coarse-graining approach to filter mesoscale weather systems, and ref. 33 analyzed coupled model simulations with varying atmospheric resolutions; both found that better-resolved atmospheric forcing strengthens northward heat transport in the Atlantic.

Discussion and conclusion remarks

In this study, we investigated the impact of PLs on the underlying ocean through a series of sensitivity experiments. Unlike the previous study5, which parameterized PL-associated wind, our approach is to directly remove PL-associated effects—including both wind and precipitation—to more accurately quantify their impact on the ocean. PL-associated wind or PL-associated precipitation influences the ocean differently: PL-associated wind enhances heat losses and upper-ocean mixing, destabilizing the water column, while PL-associated precipitation introduces fresh water at the surface, reinforcing stratification and promoting stability. To isolate these effects, we conducted two additional simulations in which the influence of PL-associated wind and precipitation were selectively removed. This allowed us to quantify the individual contributions of each component and assess the potential biases that may arise when only PL-associated wind is considered. The following conclusions are drawn from the sensitivity simulations:

-

The Northeast Atlantic Ocean exhibits the most pronounced response to PLs among all ocean basins. The primary impact of PLs on this region arises from enhanced heat losses caused by PL-associated wind, which deepens the mixed layer and increases vertical mixing, resulting in pronounced cooling of the upper ocean. In contrast, the influence of PL-associated precipitation in this region is relatively minor compared to that of the winds. Consequently, the oceanic response to PLs in this region can be mainly attributed to PL-associated wind forcing.

-

In the Labrador and Irminger Seas, the impact of PLs on the region is influenced by both vertical mixing and horizontal advection. The role of horizontal advection becomes more pronounced when considering the isolated effects of PL-associated wind or precipitation. In the PLwind simulation, an increase in horizontal heat transport leads to ocean warming, whereas in the PLwater simulation, a reduction in heat transport causes cooling. However, the opposing effects of PL-associated wind and precipitation on horizontal heat transport largely counterbalance each other when the full impact of PLs is considered (CTRL). This highlights that focusing solely on PL-associated wind can lead to a substantial misestimation of PLs’ impact in this area.

-

The influences of PLs on the Northwest Pacific Ocean and the Southern Ocean are minimal. In the Northwest Pacific Ocean, the high average surface heat fluxes make the ocean less sensitive to extreme events like PLs. In the Southern Ocean, the strong westerly winds make the ocean less responsive to the impacts of PLs.

-

Subpolar gyre region (50°N–65°N, 40°W–10°W) exhibits pronounced sensitivity to the presence of PLs. The occurrence of PLs leads to a notable accumulation of heat in this area, with water at the bottom of the mixed layer (around 200 m) warming by ~0.2 °C. The changes in potential temperature driven by PLs are of a similar magnitude to those caused by global warming in this region. This underscores the importance of explicitly resolving PLs in climate simulations to improve their reliability.

All simulations in this study were conducted at a relatively coarse resolution, which is known to underestimate ocean heat content [32]. Consequently, the actual contribution of PLs to the underlying ocean is likely greater than indicated by our results. In addition, the small spatial scale of PLs is not well captured in ERA5, where extreme wind speeds are systematically underestimated, further reducing the simulated PL impacts. Given the substantial cumulative influence of PLs on the ocean, their impact may be more pronounced in long-term climate simulations.

Uncertainties also arise from the PL detection method. Specifically, PLs are identified based on maximum relative vorticity at 850 hPa rather than on surface anomalies directly induced by PLs, which may lead to a misrepresentation of their oceanic impacts. Improved accuracy will require PL datasets derived more directly from observations, such as high-resolution satellite imagery.

Overall, the influence of PLs on the ocean exhibits pronounced regional variability, governed by the relative contributions of PL-associated wind and precipitation. This underscores the importance of accounting for the potential underrepresentation of PLs—particularly in regions such as the Northeast Atlantic—when performing climate simulations. While this study primarily focuses on the thermodynamic effects of PLs, their potential impacts on ocean circulation are only briefly addressed. In particular, their role in modulating the strength and interannual variability of boundary currents and the ACC warrants further investigation using higher-resolution and longer-term simulations. Moreover, employing high-resolution coupled atmosphere-ocean models would allow for better resolution of individual PL events and a more detailed assessment of their impacts on the ocean, representing a promising avenue for future research.

Methods

Model

The NEMO model (Nucleus for European Modeling of the Ocean; ref. 34) with ORCA05 configuration is employed in this study. In the model, the Sea Ice Modeling Integrated Initiative [SI3, ref. 35] is interactively coupled with the ocean component. The configuration is tri-polar Arakawa-C grids. The mean horizontal grid size in the Arctic Ocean (average length of the four horizontal edges of surface grid cells in the Arctic Ocean) is 29 km, with the highest horizontal resolution of 9 km. This resolution just partly resolves mesoscale eddies, so the eddy parameterization scheme36 was applied. The configuration has 46 z levels varying in layer thickness from 6 m at the surface to 250 m in the deepest layers, resolving the first baroclinic mode37, which is needed for the representation of the major baroclinic currents. The turbulent kinetic energy closure scheme was used to compute the vertical eddy viscosity and diffusivity coefficients34. The ECMWF bulk algorithm is utilized to calculate the air-sea turbulent fluxes, including sensible and latent heat fluxes38.

Experiments

Four sensitivity experiments were designed to quantify the role of PLs in ocean circulation:

-

CTRL: In the control experiment, the model is forced by ERA5 data39. ERA5 generally reproduces the locations and patterns of PLs well but tends to underestimate their intensity, both in terms of wind speed and precipitation40,41.

-

noPL: Different from CTRL, this experiment removes PL-associated anomalies in surface wind, sea surface pressure, and precipitation within a 600-km radius of the PL centers from ERA5 forcing data. The information of the PL tracks and centers are from ref. 18, which was created using a vortex identification technique42. This dataset includes the occurrence hours of PLs, totaling 180,798 h in the Northern Hemisphere and 187,201 h in the Southern Hemisphere during the period 2000–2020. Details of the PL detection method and the signal removal process are provided in Supplementary Methods and Figs. S1–S3.

-

PLwater: In this experiment, the PL-associated anomalies in surface wind and sea surface pressure are removed from the ERA5 data. The other settings are identical to the CTRL experiment.

-

PLwind: In this experiment, only the PL-associated precipitation is removed from the ERA5 data. The other settings are identical to the CTRL experiment.

Based on the design of the four sensitivity experiments, any difference between CTRL and noPL can be attributed to the impact of PLs on the ocean. The difference between PLwater and noPL reflects the effect of PL-associated precipitation. Similarly, the influence of PL-associated wind on the ocean is shown by the difference between PLwind and noPL.

To save computational resources, the initial temperature and salinity fields of the simulations were derived from a millennium-long ORCA2 simulation. The spin-up process lasted 40 years, starting with 35 years of climatological atmospheric forcing43, followed by ERA5 data from 1996 to 1999. After spin-up, the four sensitivity experiments were conducted, covering 2000 to 2020.

Data availability

ERA5 data were available from (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.bd0915c6). PL lists are available from (10.18710/TVZDBF). The data used for generating the figures have been deposited in (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30405244).

Code availability

We use basic statistics packages and plotting methods in the Python software for the analysis. The NEMO model is available from (https://forge.nemo-ocean.eu/nemo/nemo/-/releases/4.2.2). The code used to filter out polar lows is available at (https://github.com/TingLin95/pre_NEMO). Interested readers can contact us for guidance on generating the noPL data.

References

Moreno-Ibáñez, M., Laprise, R. & Gachon, P. Recent advances in polar low research: current knowledge, challenges and future perspectives. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 73, 1–31 (2021).

Montgomery, M. T. & Farrell, B. F. Polar low dynamics. J. Atmos. Sci. 49, 2484–2505 (1992).

Condron, A., Bigg, G. R. & Renfrew, I. A. Modeling the impact of polar mesocyclones on ocean circulation. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 113, C10 (2008).

Kolstad, E. W. & Bracegirdle, T. Sensitivity of an apparently hurricane-like polar low to sea-surface temperature. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 143, 966–973 (2017).

Condron, A. & Renfrew, I. A. The impact of polar mesoscale storms on northeast Atlantic Ocean circulation. Nat. Geosci. 6, 34–37 (2013).

Buckley, M. W. & Marshall, J. Observations, inferences, and mechanisms of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation: a review. Rev. Geophys. 54, 5–63 (2016).

Qiu, B. Ocean Currents: A Derivative of Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences (Academic Press, 2001).

Rintoul, S. R., Hughes, C. W. & Olbers, D. The Antarctic circumpolar current system. Int. Geophys. 77, 271–302 (2001).

Marshall, J. & Schott, F. Open-ocean convection: observations, theory, and models. Rev. Geophys. 37, 1–64 (1999).

Mauritzen, C. Production of dense overflow waters feeding the North Atlantic across the Greenland-Scotland ridge. part 1: evidence for a revised circulation scheme. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 43, 769–806 (1996).

Tsubouchi, T. et al. Increased ocean heat transport into the Nordic seas and Arctic Ocean over the period 1993–2016. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 21–26 (2021).

Nagai, T., Inoue, R., Tandon, A. & Yamazaki, H. Evidence of enhanced double-diffusive convection below the main stream of the Kuroshio extension. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 120, 8402–8421 (2015).

D’asaro, E., Lee, C., Rainville, L., Harcourt, R. & Thomas, L. Enhanced turbulence and energy dissipation at ocean fronts. Science 332, 318–322 (2011).

Armour, K. C., Marshall, J., Scott, J. R., Donohoe, A. & Newsom, E. R. Southern ocean warming delayed by circumpolar upwelling and equatorward transport. Nat. Geosci. 9, 549–554 (2016).

Rhines, P., Häkkinen, S. & Josey, S. A. In Arctic–Subarctic Ocean Fluxes: Defining the Role of the Northern Seas in Climate (eds Dickson, R. R., Meincke, J. & Rhines, P.) Ch. 4 (Springer, 2008).

Jungclaus, J., Macrander, A. & Kase, R. in Arctic-Subarctic Ocean Fluxes: Defining the Role of the Northern Seas in Climate (eds Dickson, R. R., Meincke, J. & Rhines, P.), Ch. 22 (Springer, 2008).

Stoll, P. J., Graversen, R. G., Noer, G. & Hodges, K. An objective global climatology of polar lows based on reanalysis data. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 144, 2099–2117 (2018).

Stoll, P. J. A global climatology of polar lows investigated for local differences and wind-shear environments. Weather Clim. Dyn. 3, 483–504 (2022).

Lin, T., Spengler, T., Rutgersson, A. & Wu, L. Impact of sea spray-mediated heat fluxes on polar low development. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 150, 2976–2990 (2024).

Terpstra, A., Renfrew, I. A. & Sergeev, D. E. Characteristics of cold-air outbreak events and associated polar mesoscale cyclogenesis over the North Atlantic region. J. Clim. 34, 4567–4584 (2021).

Zhang, P., Wu, Z. & Jin, R. How can the winter North Atlantic oscillation influence the early summer precipitation in northeast Asia: effect of the Arctic sea ice. Clim. Dyn. 56, 1989–2005 (2021).

Irrgang, C., Saynisch, J. & Thomas, M. Estimating global ocean heat content from tidal magnetic satellite observations. Sci. Rep. 9, 7893 (2019).

Tsujino, H. et al. Evaluation of global ocean–sea-ice model simulations based on the experimental protocols of the ocean model intercomparison project phase 2 (OMIP-2). Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 3643–3708 (2020).

Sohail, T., Gayen, B. & McC. Hogg, A. The dynamics of mixed layer deepening during open-ocean convection. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 50, 1625–1641 (2020).

Renfrew, I. A. et al. Coupled atmosphere–ocean observations of a cold-air outbreak and its impact on the Iceland Sea. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 149, 472–493 (2023).

Brakstad, A., Våge, K., Håvik, L. & Moore, G. Water mass transformation in the Greenland Sea during the period 1986–2016. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 49, 121–140 (2019).

Treguier, A. M. et al. The mixed-layer depth in the ocean model intercomparison project (OMIP): impact of resolving mesoscale eddies. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 3849–3872 (2023).

Chang, P. et al. An unprecedented set of high-resolution Earth system simulations for understanding multiscale interactions in climate variability and change. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2020MS002298 (2020).

Yashayaev, I. Intensification and shutdown of deep convection in the Labrador Sea were caused by changes in atmospheric and freshwater dynamics. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 156 (2024).

Holdsworth, A. M. & Myers, P. G. The influence of high-frequency atmospheric forcing on the circulation and deep convection of the Labrador Sea. J. Clim. 28, 4980–4996 (2015).

Swart, S. et al. State of the climate in 2017. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, Si–S310 (2018).

Jung, T., Serrar, S. & Wang, Q. The oceanic response to mesoscale atmospheric forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1255–1260 (2014).

Roberts, M. J. et al. Description of the resolution hierarchy of the global coupled HadGEM3-GC3.1 model as used in CMIP6 HighResMIP experiments. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 4999–5028 (2019).

Madec, G. et al. Nemo ocean engine reference manual. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/record/8167700 (2023).

Vancoppenolle, M. et al. Si3, the Nemo sea ice engine (4.2 release_doc1. 0). Zenodo (2023).

Gent, P. R. & Mcwilliams, J. C. Isopycnal mixing in ocean circulation models. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 20, 150–155 (1990).

Stewart, K. et al. Vertical resolution of baroclinic modes in global ocean models. Ocean Model. 113, 50–65 (2017).

Buizza, R. et al. New IFS cycle brings sea-ice coupling and higher ocean resolution. ECMWF Newsl. 150, 14–17 (2017).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Lavers, D. A., Simmons, A., Vamborg, F. & Rodwell, M. J. An evaluation of ERA5 precipitation for climate monitoring. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 148, 3152–3165 (2022).

Moreno-Ibáñez, M., Laprise, R. & Gachon, P. Assessment of simulations of a polar low with the Canadian regional climate model. PLos ONE 18, e0292250 (2023).

Shun-ichi, I. W., Niino, H. & Yanase, W. Climatology of polar mesocyclones over the Sea of Japan using a new objective tracking method. Mon. Weather Rev. 144, 2503–2515 (2016).

Large, W. G. & Yeager, S. G. Diurnal to Decadal Global Forcing for Ocean and Sea-Ice Models: The Data Sets and Flux Climatologies. Report No. TN-460+STR (National Center for Atmospheric Research, 2004).

Acknowledgements

Ting Lin and Lichuan Wu are supported by the Swedish Research Council (no.2020-03190; 2024-04209) and Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning (no. 2024-00375). The computations/data handling were enabled by resources provided by the National Academic Infrastructure for Supercomputing in Sweden (NAISS), partially funded by the Swedish Research Council through grant agreement no. 2022-06725.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.L. contributed to the conceptualization, generated the figures, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. L.W. contributed to the conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, and review and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Alan Condron and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Seung Ki Min and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, T., Wu, L. The impact of polar lows on the underlying ocean varies significantly by location. Commun Earth Environ 6, 943 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02972-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02972-0