Abstract

Airborne micro- and nano-plastics represent an underestimated threat to urban environments and human health. We characterized their concentrations and polymer composition in size-fractionated particulate matter collected in Leipzig, Germany, using pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectrometry. Total concentrations of plastic particles <10 µm averaged 0.6 ± 0.2 µg/m3, with fine and coarse fractions contributing equally. Tire wear particles dominated, accounting for about 65% total plastics, followed by polyvinyl chloride, polyethylene, and polyethylene terephthalate. These polymers correlated strongly with carbonaceous aerosol markers, indicating co-emission and atmospheric mixing. Exposure and risk assessment suggest that inhalation of approximately 2.1 µg of these airborne plastic particles per day may increase cardiopulmonary mortality by 9% and lung cancer mortality by 13% in humans. By integrating exposure, risk assessment, and analytical data, these findings highlight the need for global policy action, emphasizing the value of region-specific research for air quality and public health initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Airborne plastic particles have emerged as a concerning component of particulate matter (PM) air pollution. These materials, defined as nanoplastics (≤1 μm) and microplastics (1 µm-1 mm), or together as MNPs1, have the potential to intervene in ecological processes and impact human health2. MNPs have been detected in remote geographic regions such as the North Pole3, South Pole4 and high altitude sites5,6, highlighting their omnipresence and long-range atmospheric transport7. Airborne MNPs are suspected to be released from a variety of anthropogenic sources, including tire wear particles (TWPs) and brake wear particles (BWPs)8, incineration bottom ash residues9, textile fibers10, resuspended road and soil dust11,12,13, and urban surfaces14. In addition to that, oceanic microplastics can re-enter the atmosphere via sea spray15,16, further contributing to the global plastic cycle. In spite of the increased prevalence in the environment, the potential health risks associated with inhalable MNPs remain understudied.

Since 2015, research interest in airborne MNPs has accelerated17,18,19,20,21,22,23 as concerns mount regarding the inhalation of airborne MNPs with PM2.5 and PM102,24,25. Inhalable MNPs can be taken into the deep lung26 where they are suspected of causing oxidative stress, cytotoxicity, and chronic inflammation, and potentially contributing to respiratory diseases, including interstitial lung disease and fibrosis27. These MNPs, once airborne, have the ability to act as carriers for co-contaminants such as heavy metals28, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons29, pharmaceuticals30 and carbonaceous parameters31, which can amplify their toxicity. No clear regulatory thresholds for emissions and inhalation of MNPs exist, prompting the World Health Organization (WHO)32 and European Environment Agency33 to call for standardized exposure assessments that support their relevance to human health within the framework of Sustainable Development Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-Being). As part of the ongoing negotiations under the Global Plastics Treaty, marine plastic pollution has now received considerable attention, but airborne MNPs are under-represented in global policy dialogues, regardless of their ubiquitous distribution and potential direct human exposure34.

There are several techniques available for analyzing airborne MNPs, including vibrational spectroscopy methods such as µ-Raman35 and µ-FTIR36, which provide information on particle size, number, and polymer composition. However, their detection limits (≥1 μm for µ-Raman, ≥10 μm for µ-FTIR) and susceptibility to fluorescence or organic matter interference restrict their applicability, particularly for nanoplastics. The pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Py-GC-MS) approach, on the other hand, provides polymer-resolved, mass-based quantification with high sensitivity and comparable less pretreatment. Thus, Py-GC-MS is particularly suitable for samples in complex environments such as airborne MNPs.

Within the present study, we address the aforementioned uncertainties by applying Py-GC-MS for detailed polymer-specific characterization of size-segregated airborne MNPs in PM10 (PM10MNPs), PM2.5 (Fine microplastics; FMPs) and PM10-2.5 (Coarse microplastics; CMPs). The concentration data generated through this analysis served as the foundation for the subsequent interpretation of their secondary interactions in the atmosphere by investigating how they are related to carbon sum parameters. Additionally, by integrating size-resolved exposure estimates with a polymer-specific hazard index, the present study deduces the relative risk potential associated with MNP inhalation and highlights the substantial health burden posed by airborne MNPs. We believe that this integration of polymer-specific quantification with health risk modeling represents a key advance in the field and provides urgently needed evidence for policy and regulatory discussions. The findings are therefore relevant not only for air quality guidelines but also for international policy frameworks aimed at reducing plastic pollution and protecting public health.

Results and discussions

Concentration and distribution of airborne MNPs

Currently, there is no standardized method for qualitative and quantitative analysis of polymers via their pyrolysates37. Therefore, the present study identified and quantified polymer clusters (prefix-C is added to every analyzed polymer) such as polyethylene (C-PE), polypropylene (C-PP), polyvinyl chloride (C-PVC), polyethylene terephthalate (C-PET), polystyrene (C-PS), polymethyl methacrylate (C-PMMA), polycarbonate (C-PC), polyamide-6 (C-PA6), polyurethane (MDI-PUR), car tire tread (CTT) and truck tire tread (TTT) based on the quantifiers listed in Goßmann et al.19,38,39, with cluster-associated compounds detailed in supplementary information (Supplementary Table 1). A cluster definition is necessary because in environmental samples, polymers are not only used as homopolymers but often as co-polymers, block polymers or composite polymers. They are also used as resins and coatings. Consequently, all detected indicator signals after thermal decomposition are mixed signals from these different sources, which can be assigned to the proportion of the respective polymer. Therefore, the respective polymer concentration is quantified as a homopolymer but indicated as a cluster19. To address potential overlaps with black carbon (BC), all the data related to the C-PVC cluster are labeled with an asterisk (*), which shows its mixed origin as recently shown by Goßmann et al. (manuscript accepted40 and ref. 38). Since thermal trace analysis of C-PVC* and related polymers only generates non-specific, aromatic indicator products, unavoidable interferences occur in complex environmental samples. In this study, Naphthalene was used as an indicator (Supplementary Table 1) for C-PVC*, despite its low specificity, due to the lack of a more selective alternative. As a result, C-PVC* is a mixed cluster with unknown proportions of chlorinated polymers on the one hand and, in particular, BC from various sources on the other. Since both PVC and BC are of high (toxicological) relevance with regard to air pollutants in the urban environment, which comes almost exclusively from anthropogenic sources41,42, this cluster is both included in the overall MNPs calculations and discussed in detail. This study does not quantify C-PA6 and MDI-PUR due to undetectable signals (<LOD) in the analyzed samples, as their contribution is supposed to be very low, which may contribute to a potential underestimation of total MNP mass. This limitation is likely related to the relatively short sampling duration; therefore, a longer sampling duration is required to enhance detection sensitivity for such polymers.

In the present study, concentrations of MNPs in PM10MNPs, FMPs and CMPs are reported, where CMPs were calculated by subtracting the concentration of FMPs from PM10MNPs. This data representation approach has been applied to observe the distribution and behavior of MNPs in different size fractions of airborne polymeric particles. The total MNPs (∑MNPs) concentration is the collective summation of all the polymers that have been quantified for their size fraction in this study. The FMPs/PM10MNPs and CMPs/PM10 MNPs ratios represent the respective proportions of FMPs and CMPs within the total PM10MNPs.

The concentration and distribution of airborne MNPs showed considerable variation across particle size fractions during the sampling days (Fig. 1a). The variability in daily concentrations of MNPs agrees with previous studies20,31,43,44, suggesting contributions of multiple influencing factors such as emission sources45, atmospheric conditions, meteorological parameters46, and secondary formation processes47. Our observations also showed these variations, and a summary of the weather conditions during the study period is given in Supplementary Section S1.

a Daily mass concentrations of Polystyrene (C-PS; dark yellow), polycarbonate (C-PC; green color), polypropylene (C-PP; pink color), polymethyl methacrylate (C-PMMA; yellow color), polyethylene terephthalate (C-PET; blue color), polyethylene (C-PE; orange color), polyvinyl chloride (C-PVC*; olive color), Truck tire tread (TTT; dark gray color), Car tire tread (CTT; light gray color) in total PM10MNPs (solid color bar), fine microplastics (FMPs; diagonal shaded bar), and coarse microplastics (CMPs; cross shaded bar) over the two-week sampling period. Error bars represent standard deviation, indicating variability in measured concentrations. b Box plot for each quantified polymer contains minimum, maximum, and mean values with individual data points in circles representing relative contributions of FMPs and CMPs to PM10MNPs, expressed as FMPs/PM10MNPs (Pink color) and CMPs/PM10MNPs (Dark Gray color) ratios, respectively. Data show an approximately equal partitioning of MNPs mass between FMPs and CMPs with noticeable temporal variability.

Temporal trends and size-segregated mass concentration

During the two-week sampling period, the average mass concentration of total (∑) PM10MNPs was 0.6 ± 0.2 µg/m³ (0.4–0.9 µg/m³). ∑FMPs and ∑CMPs each averaged 0.3 ± 0.1 µg/m³, with ranges of 0.1–0.5 µg/m³ and 0.1–0.6 µg/m³, respectively. Both contributed equally to ∑PM10MNPs at 0.5 ± 0.2, indicating a balanced distribution in ambient air (Fig. 1a, b; Supplementary Table 2). The observed concentration aligns with findings from an urban study in Graz, Austria31, which reported 0.238 µg/m³ of MNPs in PM2.5 but is lower than the concentrations of 1.2 µg/m³ found in size-segregated aerosols (0.45-11 µm) in Kyoto, Japan21 and 5.6 µg/m³ in PM2.5 samples from Shanghai, China43. It should be noted that discrepancies in reported MNP concentrations across sites are partly due to differences in quantification strategies, particularly the choice of marker compounds/quantifiers, which limits the direct comparability of absolute values in addition to variations in local emission sources. Airborne MNPs emitted in urban areas have a long-distance travel potential and can be deposited at high alpine site44, over the north-south Atlantic Ocean48 and in the northern Atlantic Ocean19 contributing to their detection in remote regions6,7,49,50.

In this study, polymers from clusters like C-PVC*, C-PMMA, C-PE, C-PET, and TTT indicated their dominance in FMPs with 0.6 FMPs/PM10MNPs compared to CMPs (Supplementary Table 2). On the contrary, clusters from C-PP, C-PS and C-PE have shown their predominant existence in CMPs with 0.7 CMPs/PM10MNPs (Supplementary Table 2). C-PC has a unique characteristic, which appears to be entirely in FMPs, which can be attributed to its brittle nature and susceptibility to environmental degradation (e.g., UV exposure, abrasion), resulting in preferential fragmentation into smaller airborne particles51,52. Additionally, binders of epoxide-based coatings are included in the C-PC. Abrasion of respective surfaces is supposed to be of a very low particle size as well. Typically, ratio (PM2.5/PM10) values below 0.6 suggest that PM may originate from re-suspended soil dust, long-distance dust transport, processing industries, and other mechanical activities53,54,55. Interestingly, CTT and total TWPs (CTT + TTT) exhibited equal contributions in FMPs and CMPs (Supplementary Table 2), consistent with findings from a road simulator laboratory analysis56 having PM2.5/PM10 ratio of 0.5. The ambient concentrations of each quantified polymer are given in the supplementary information (Supplementary Fig. 1a–j; Supplementary Table 2). CTT has the highest concentration among all the polymers in each PM size fraction, and TTT makes a lower but significant contribution to TWPs. The high concentration of TWPs highlights the important contribution of vehicular traffic to airborne MNPs (Supplementary Table 2), attributing their prevalence to tire abrasion influenced by traffic density, driving patterns, and road conditions8. Following TWPs, polymers such as C-PVC*, C-PE, and C-PET were consistently dominant across PM size fractions (Supplementary Table 2). Compared to the current study, Chen et al.43 observed elevated levels of PVC (0.5 µg/m³) and PE (4.2 µg/m³) in PM2.5 at urban sites in Shanghai, China. Similarly, higher levels of PE (230 ng/m3), PET (39 ng/m3) in particle size of 0.43–2.1 µm and PS (4 ng/m3) in particle size of 7.0 to 11.0 µm were reported in Kyoto, Japan21. There was a moderate median PM2.5 concentrations of PET (up to 180 ng/m³), PP (up to 40.5 ng/m³), and PE (up to 33.3 ng/m³) in different classes of region observed in Graz, Austria31, while at high alpine sites, Kau et al.44 reported variable PET concentrations (4.1–29.5 ng/m³ in PM1; 0.53–35.6 ng/m³ in PM10). In another urban study in China, Luo et al.20 noted significantly lower PE levels (5.0-10.2 pg/m³). Such differences in the concentrations most plausibly arise from methodological variability, including the choice of quantifier20, instrumentation31, size segregation sampling21 and extraction procedures57 applied for MNP analysis. These variations can be due to difference in A study at Tokushima University, Japan, Mizuguchi et al.58 detected lower PP (<LOD to 3.5 ng/m³) and PS (0.25–0.76 ng/m³) concentrations in PM10 samples. A comparative overview of reported mass concentrations of MNPs in different PM size fractions across various global locations is given in supplementary information (Supplementary Table 3), emphasizing the variability in urban airborne MNPs pollution and the urgent necessity of standardized analytical methods for consistent and meaningful data and derived health risk evaluation.

Size-fraction dependent polymer composition

Within the present study, TWPs accounted for 60-65% in each PM size fraction (Fig. 2), which aligns with European reports59, attributing 64% of microplastic emissions to tire wear. According to Kraftfahrt Bundesamt60, in 2022, Saxony had 2,185,262 cars and 223,906 registered trucks and buses, reflecting on our findings that CTT emissions are over ten times higher than TTT (Supplementary Table 2). TWPs in the air are not limited to urban areas38,61,62 but can also transported via wind to the open ocean19,49 and high alpine sites44,63, highlighting their widespread dominance among polymers. Our study results observed that following TWPs, C-PE (12-17%), C-PVC* (12-14%) and C-PET (4-7%) are the most prominent polymers existing in all size fractions (Fig. 2a–c). These polymers were also generally reported in a variety of environmental matrices due to their significant production in Europe64 and consumption65,66. An urban area study in Oldenburg, Germany, Goßmann et al.38, also observed a similar trend in polymer composition from roadside spider web samples. Although C-PS, C-PP, and C-PC have significantly less contribution (0.1–0.6%) in all size fractions (Fig. 2a–c), aligning with the previous polymer analysis studies38,50,67, their presence is still important for studying the dynamics of MNPs. Moreover, our study revealed the predominance of C-PVC*, C-PC, C-PMMA, and TTT in FMPs, while C-PP, C-PE, C-PET, and C-PS are more prevalent in CMPs. This distinction forms two different polymer groups based on size fractions, which is consistent with the discussion in previous section. In order to confirm it statistically, pairwise statistical comparisons (Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, n = 14) were performed, which revealed that C-PC and C-PMMA were significantly enriched in FMPs, while C-PP and C-PS were significantly enriched in CMPs. Directional trends also suggested enrichment of C-PVC and TTT in FMPs and C-PE and C-PET in CMPs (Supplementary Table 4). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) further confirmed size-fraction driven differences in polymer composition (Supplementary Fig. 2). FMPs clustered with C-PC, C-PMMA, C-PVC*, and TTT, whereas CMPs clustered with C-PE, C-PP, C-PET, and C-PS along the first two principal components (explaining ~48% of variance). This clear segregation supports our hypothesis that FMPs and CMPs are compositionally distinct, with different polymer drivers dominating each size class.

Percentage contribution of dominant and minor polymers in (a) PM10MNPs, (b) Fine microplastics (FMPs), and (c) Coarse microplastics (CMPs). Tire wear particles [TWPs: Car tire tread (CTT; light gray color) + Truck tire tread (TTT; dark gray color)] contributed the highest fraction across all size classes, followed by polyethylene (C-PE; orange color), polyvinyl chloride (C-PVC*; olive color), and polyethylene terephthalate (C-PET; blue color). Polystyrene (C-PS; dark yellow), Polypropylene (C-PP; pink color), polymethyl methacrylate (C-PMMA; yellow color), and polycarbonate (C-PC; green color) were found at lower levels.

Relative polymer contribution

In the present study, the total PM10 mass load ranged from 10.9 to 24.3 µg/m³, with a mean of 16.7 ± 3.8 µg/m³. On average, 3.6% by mass of the total PM10 mass was contributed by MNPs. The PM2.5 mass load ranged from 6.9 to 16.1 µg/m³ (mean: 11.1 ± 2.9 µg/m³), with FMPs contributing 2.8% by mass. For PM10-2.5, the mass load varied between 3.4 and 8.2 µg/m³ (mean: 5.7 ± 1.5 µg/m³), with CMPs accounting for 5.2% by mass of the total mass load. (Fig. 3a-c). A few urban environmental studies reported 13.2% in Shanghai, China43, 0.67% in Graz, Austria31 and 0.2% in Taiwan68 contributions as FMPs in total PM2.5 mass load. The German Environment Agency (UBA) report69 indicated that TWPs contributed 3.1% and 4.6% of total PM10 and PM2.5 mass load, respectively. A study in Hamburg, Germany, Samland et al.70 reported that 12% of PM10 and PM2.5 mass on major roads consists of TWPs and BWPs. In another study from Stockholm, Sweden, TWPs accounted for approximately 4% to 6% of total PM10 concentrations71. In this study, TWPs accounted for 2.3% of PM10 and 1.9% of PM2.5 mass loads, respectively. Despite the variability in absolute values, a clear trend emerges. MNPs, and especially TWPs, consistently form a measurable part of urban PM. The somewhat lower contributions observed in our study compared with locations such as Shanghai or Hamburg are likely related to differences in traffic density, sampling duration, and analytical methods. Our results fall within the range reported elsewhere and add to the evidence that MNPs are a recurring feature of urban air pollution. Even though the contribution of MNPs to the total PM mass is below 10% compared to other chemical constituents (such as organic and inorganic)72, their abundance reflects the presence of an omnipresent and relevant pollutant class in the atmospheric environment. The consistent presence of MNPs, together with the known toxicity of some polymer types, indicates that their health impacts may be more significant than their mass contribution. Understanding these contributions is essential for developing mitigation strategies and assessing potential health risks of MNPs.

a Average mass proportion (black dashed line) of PM10MNPs within total PM10 mass load, where blue bars and black circles represent the PM10 mass load and percentage contribution of PM10MNPs for each day, respectively. b Average mass proportion (black dashed line) of fine microplastics (FMPs) relative to PM2.5 mass load, where orange bars and black triangles represent the PM2.5 mass load and percentage contribution of FMPs for each day, respectively. c Average mass proportion (black dashed line) of coarse microplastics (CMPs) to PM10-2.5 mass load, where yellow bars and black squares represent the PM10-2.5 mass load and percentage contribution of CMPs for each day, respectively. All data reflect the integrated contribution of total polymer mass to urban ambient aerosol burdens.

Inter-polymer and carbon sum parameters associations

Understanding interrelations between carbonaceous parameters and polymers is crucial for identifying sources and transformations in the atmosphere. Limited studies have explored inter-relationships among polymers and their association with other urban pollutants, significantly influencing their environmental fate and transport mechanisms73. This highlights the need for further research and data dissemination on the extent of MNPs pollution74. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R) was calculated (Supplementary Table 5a–c) with p value < 0.05 to check the interaction between the detected polymers and carbon sum parameters in their respective size fractions.

Inter-polymer associations

In the present study, C-PMMA showed better correlations with C-PE (R = 0.76) and C-PP (R = 0.56) in FMPs (Supplementary Table 5b), suggesting common sources such as cosmetics and personal care products75, with TTT (R = 0.61) and C-PS (R = 0.57) indicating emissions associated with TWPs and construction materials, respectively51,67,76. C-PVC*/C-PP (R = 0.60) and C-PP/C-PE (R = 0.61) (Supplementary Table 5b) indicated a similar fragmentation process77. Other correlating polymers, such as C-PE, C-PET and C-PS (R = 0.55), reflect their widespread use in single-use plastic bags, containers, construction materials, textiles, and other common sources51,67. Their concurrent application in packaging and consumer products, combined with similar fragmentation properties and resuspension pathways, likely explains their co-occurrence in the atmosphere. A study from China43 reported significant correlations between PS, PVC, and PE (R = 0.68–0.82), suggesting a shared emission source and such relationships were not observed in our study (Supplementary Table 5b) except for PM10MNPs C-PVC*/C-PE (R = 0.81) (Supplementary Table 5a). This underlines that the composition and emissions of MNPs can vary depending on study location, population density, and topography, even in urban areas. In this study, overall CMPs show weaker correlations than FMPs (Supplementary Table 5c), likely due to differences in degradation, transport, or sources78, with a notable CTT/C-PS correlation (R = 0.60) suggesting co-emissions from tire wear and road markings79. This pattern suggests that fine fractions capture stronger source-related signals, whereas coarse fractions might be influenced by more complex atmospheric mixing and processing. TWPs have strong correlations (R = 0.95, 0.93, and 0.96 in ∑PM10MNPs, ∑FMPs, and ∑CMPs, respectively). This finding highlights their substantial contribution to atmospheric MNPs loading, primarily from tire wear, representing primary MNPs80 generated through road surface abrasion54,81. The observed co-occurrence of road marking particles and TWPs is consistent with traffic-related sources, which dominate at the sampling site, as also reported in earlier studies. Our observations showed meteorology-related variations, and a summary of the weather conditions during the study period is provided in Supplementary Section S1. However, because meteorological variability during the sampling window was relatively limited (Supplementary Fig. 3a–d and Supplementary Fig. 4), it is unlikely to explain the inter-polymer correlations observed fully. Instead, the associations are more plausibly linked to shared usage patterns and traffic-related sources. Taken together, these findings suggest that meteorology may influence variability in overall concentrations, but polymer co-occurrence in our dataset is primarily driven by source. Therefore, further source-specific analysis would help refine this conclusion.

Relationship between MNPs and carbon sum parameters

Individual concentrations of all the carbon sum parameters and their relative PM ratios, are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Although MNPs constitute only a small fraction of the total PM and carbon load, their high surface-area-to-volume ratio, particularly in the fine fraction, enables them to act as potential carriers for organic compounds, as shown in previous studies31,44,82. This suggests that FMPs, despite their low abundance, may contribute to the adsorption and transport of carbonaceous material within the atmosphere. Similar to inter-polymer associations, correlations in FMPs with carbon sum parameters are stronger compared to PM10MNPs and CMPs (Supplementary Table 5a–c), reflecting that fine particles offer a clearer representation of MNPs associations and possess greater sorption capacity for organic contaminants82. A strong correlation (R = 1.0) between Total Carbon (TC) and Organic Carbon (OC) in all PM size fractions indicated that the organic fraction of carbon is dominant over the total. Additionally, the correlation value of OC and Primary Organic Carbon (POC) (R = 0.72), OC and Secondary Organic Carbon (SOC) (R = 0.91) in FMPs showed a significant existence of primary and secondary carbon in the organic fraction. In contrast, CMPs only observed their dominance as secondary carbon rather than primary carbon (Supplementary Table 5a–c), suggesting their potential role in interacting with secondary formation processes in the atmosphere. Similarly, the correlation between POC and Elemental Carbon (EC) (R = 1.0) across all PM size fractions suggested a common origin, likely from incomplete combustion sources, such as diesel exhaust and biomass burning83. In our study, only C-PMMA, C-PVC*, and C-PE within PM10 MNPs showed strong correlations with all carbon parameters (R = 0.53–0.94), demonstrating their strong association with particulate organic matter (POM) and indicating that they occur as particle-bound species embedded in organic matrices while coexisting within both primary (POC) and secondary (SOC) carbonaceous fractions (Supplementary Table 5a). The correlation of C-PET with POM (R = 0.40) and EC (R = 0.44), which is lower than the correlations observed at a high alpine site in Sonnblick, Austria44, is attributed to differences in source contributions and atmospheric processes. Except for SOC, ∑FMPs are strongly correlated with EC, OC, TC, POC, and POM (R = 0.67–0.80), suggesting that a significant portion of these MNPs likely originate as POM from primary sources like TWPs (Supplementary Table 5b). In comparison to our study, a weaker correlation was observed in Austria31 between ∑MNPs and OM (R = 0.46) and EC (R = 0.51). Notably, individual polymers such as C-PET, C-PS, and C-PE showed strong correlations with OC, SOC, and POM (R = 0.51–0.80) (Supplementary Table 5b), which are in agreement with the previous results in urban samples31. These polymers can release volatile organic compounds (VOCs), e.g. monomers, oligomers and additives during their degradation or processing, which may undergo atmospheric reactions leading to the formation of SOA84. However, polymers like C-PC, CTT, TTT, and TWPs correlated strongly with EC and POC (R = 0.59-0.79), indicating their primary origin from traffic emissions such as vehicle components, tire treads and surface abrasion (Supplementary Table 5b). Since refractory polymeric carbon such as BC, but also PVC, is part of the C-PVC* cluster, its correlation with the various carbon parameters is not very conclusive. Contrary to ∑FMPs, ∑CMPs correlated poorly with OC but significantly with SOC rather than POC, suggesting SOA formation during secondary processes, particularly in C-PS and TWPs (Supplementary Table 5c). The observed correlations between MNPs and carbon fractions suggest co-occurrence in the aerosol phase, likely driven by common emission sources or atmospheric transport processes. Although the small mass fraction of MNPs in this study makes direct adsorption difficult to establish, previous studies82 have documented the ability of microplastics to adsorb carbonaceous material. Therefore, it remains plausible that FMPs in our samples also adsorbed organic carbon from the surrounding environment, contributing to the observed correlations.

Estimated MNPs intake, exposure and their toxicity on humans

Inhalation of airborne MNPs is increasingly recognized as a potential exposure pathway, though their health impacts are not fully understood. According to the WHO, mass concentration is a crucial parameter for evaluating air pollution exposure and its health effects, along with developing legislation to address public exposure to MNPs85. This section presents exposure estimates based on measured concentrations; however, where potential effects are discussed, they remain largely hypothetical. Targeted studies are needed to address current knowledge gaps and verify these assumptions. In order to observe outdoor inhalation exposure, from measured ∑MNPs concentration in ambient air, we have calculated the amount of MNPs that can enter the body (ages 20-59) through outdoor inhalation (refer to Materials and methodology section and Eq. 7 for more details). The study estimated a daily inhalation exposure of 2.1 µg of PM10MNPs, including 1.1 µg of FMPs and 0.94 µg of CMPs (Fig. 4a). Upscaling these inhalation exposure estimates to annual intakes of 0.7 mg, 0.4 mg, and 0.3 mg, respectively, is essential for evaluating long-term health risks and ensuring that laboratory findings reflect real-world exposure for meaningful dose-response assessments. These annual intakes are comparable to those reported in an Australian indoor house dust study in Sydney86 (0.2 mg/kg-body weight/year). An additional study in Taiyuan, China20, estimated the daily intake of PE bound to PM2.5 at 34 pg/day. In contrast, a broader range of MNPs intake, from 61.85 to 102.59 µg/day, was observed in Mumbai87, India. However, as the analytical methods used in these studies are neither standardized nor consistent, evaluating these differences remains challenging, as highlighted in earlier section. Using model approaches24,25, reported estimations of daily MNPs intake via air, reported 8.23 × 10-6 µg/day and 1.07 ×10-7 mg/capita/day, respectively. Based on the modeling approach findings, it appears that airborne MNPs intake may be higher in the present than previously estimated, emphasizing the value of analytical measurements to complement model-based exposure assessments.

a Daily inhalation estimates of PM10MNPs (Blue color), including fine microplastics (FMPs; orange color) and coarse microplastics (CMPs; green color), for adults under average urban exposure. Solid lines of each color represent the average daily intake of MNPs in the respective size fractions. b Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) plot depicting probabilistic distribution of MNPs intake, highlighting peak exposures of FMPs (orange curve) as compared to PM10MNPs (blue curve) and CMPs (green curve). c Relative Risk (RR) values for lung cancer (red color) and cardiopulmonary mortality (black color) linked to FMPs exposure across sampling days. Blue dashed line marks the RR = 1 threshold; error bars indicate variability in the measurements.

Moreover, a statistical analysis by Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test24 assessed the probabilistic density of MNPs intake across different particle sizes. The test shows that a peak in FMPs intake highlights a consistent and widespread exposure level across the population (Fig. 4b) compared to PM10MNPs and CMPs. Due to the small size of FMPs, they can penetrate deeper into the respiratory tract, highlighting a higher potential for long-term retention and systemic exposure88. Based on this assumption and to explore potential health impacts, this study calculated relative risk (RR) and attributable fraction (AF) for FMPs exposure (Eqs. 8 and 9) on the basis of existing epidemiological models to estimate environmental burden of disease68,89 (Supplementary Table 6). This study found indications for potential increased mortality risks of 5–9% for cardiopulmonary (RR: 1.08 ± 0.01; CI: 1.06–1.10) and 8–13% for lung cancer (RR: 1.12 ± 0.02; CI: 1.09–1.15) compared to the threshold level (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Table 6). Although RR remained consistently higher than the threshold throughout the study period, it is closely aligned with findings from Colombia’s northern Caribbean region90, which reported RR values of 1.00 ± 0.001 for cardiopulmonary disease and 1.11 ± 0.06 for lung cancer. However, the risks observed in the present study are lower than those reported for Taiwan68 (AF: 26.4 ± 12.6% for cardiopulmonary and 26.7 ± 12.9% for lung cancer) and Romania89 (AF: 17.5–24.6% for cardiopulmonary and 25.0–34.4% for lung cancer) but notably higher than those reported in a European meta-analysis, which found PM2.5-associated RR of 1.03 for lung cancer incidence and 1.05 for mortality91. These observations suggest that, despite their small mass, prolonged exposure to airborne MNPs may pose health risks over time. The elevated RR for lung and cardiopulmonary mortality, which could be derived from the comparative assessments of this study, may be influenced by a possible polymer-specific toxicity of PM92. Studies suspect this is in connection with lung deposition of PE, PET, PP93, which have also been detected in placental94 and liver95 tissue, and are possibly related to respiratory, fetal development and hepatic function issues. To incorporate polymer-specific considerations, we calculated the Polymer Hazard Index (PHI) according to Lithner et al.42, which is based on monomer hazard classifications. This approach, combined with PM2.5 risk models, serves as a first-order approximation in the absence of polymer-specific dose-response data, while underscoring the need for further toxicological research on MNPs. Polymers like C-PE, C-PET, and C-PP have been categorized as IV, III, and I, respectively, with PHI shown in Supplementary Table 7 indicating C-PE is more hazardous compared to the other polymers (C-PET and C-PP) and can cross the blood-brain barrier, potentially leading to neurotoxic effects and neurodegenerative diseases96,97. We detected substantial TWPs (Hazard Category V for CTT and TTT), which are known to carry a cocktail of harmful chemicals such as benzothiazoles and 6-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline quinone (6-PPDQ), contributing to acute toxicity, oxidative stress, and chronic respiratory and cardiovascular issues98,99. C-PVC*, notably abundant in fine particles and having the highest PHI after TWPs are categorized as the most hazardous (Hazard Category V) polymer that can induce arterial plaque formation and systemic inflammation, increasing cardiovascular risks100. PVC as part of C-PVC* is produced from vinyl chloride monomer compound classified as a Group 1 carcinogen, and was assigned one of the highest hazard scores due to its strong associations with carcinogenicity and mutagenicity42. Complementing this, it was found that PVC is dominant in human lung tissue101 but also and accounts as C-PVC* for over 97% of the total PHI, indicating its overwhelming contribution to health risks from inhaled microplastics. These calculations are based on the C-PVC* data, which do not allow any analytical differentiation between PVC and soot/BC. Since BC is also a highly toxicologically relevant polymer, the derived data remain highly relevant. C-PS, although less abundant, falls under Hazard Category II (Supplementary Table 7) and, according to previous experimental studies, it has the potential to induce cellular apoptosis, disrupt cellular integrity, and has been linked to reproductive toxicity and hormonal disruptions, including impacts on testicular functions102. C-PC exposure (Hazard Category IV) is associated with tissue damage, redox homeostasis in the liver and imbalance of various metabolic pathways in the human body103. To improve clarity and focus on the key findings, we have consolidated the hazard categories, associated chemicals, and potential human health impacts into Supplementary Table 7, facilitating a direct comparison of toxicity data. The consistency between our risk estimates (RR, AF and PHI) and an increasingly evident polymer-specific toxicity strengthens the case that MNPs inhalation represents a genuine public health concern. It is important to emphasize that while these risk values provide insight into potential health concerns, they are based on associations and modeled estimates rather than direct causality.

Conclusions

The present study offers a detailed characterization of airborne MNPs in an urban environment, revealing their significant presence across PM size fractions and highlighting TWPs as the dominant source, followed by C-PVC*, C-PE, and C-PET. FMPs enriched with hazardous polymers, such as C-PVC* and TWPs, pose greater inhalation risks due to their potential for deep lung deposition and interaction with carbon sum parameters. Our findings estimated a daily as well as annual inhalation intake of MNPs and identified elevated mortality risks for cardiopulmonary and lung cancer outcomes, which underscores the need for regulatory attention. Importantly, while this study is geographically localized, the implications are far-reaching as regional studies like this are essential to inform global exposure baselines and guide science-driven policy. Addressing MNPs pollution is critical to achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 (Good Health and Well-being) by reducing human exposure, SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) by integrating air quality management into urban planning, and SDG 13 (Climate Action) by mitigating the atmospheric impact of MNPs emissions. In this context, actionable measures include regulating tire wear emissions, establishing standardized monitoring protocols for airborne MNPs, and integrating polymer-specific indicators into existing air quality regulations. In summary, while current evidence increasingly suggests that inhalation of MNPs, particularly FMPs, could have health implications, more longitudinal and mechanistic studies are required to confirm polymer-specific toxicities, establish safe exposure thresholds, and inform regulatory standards. Until then, our findings underscore the importance of monitoring airborne MNPs as emerging pollutants and continuing to refine health risk assessment methods.

Materials and methodology

Reference standards and chemicals

Commercially available raw polymers were used as standards to quantify MNPs in air. A total of eleven polymers were selected, including PE, PP, PVC, PET, PS, PMMA, PC, PA6, MDI-PUR, CTT, and TTT. Detailed information on these polymer standards used for identification and quantification of the respective clusters including suppliers, is provided in Supplementary Table 8. Ethanol and Dichloromethane (DCM) was taken from Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg laboratory supply store, partly further distilled to residue grade, Hexafluoro isopropanol (HFIP) (Sigma Aldrich, Germany), Acetone, Tetrahydrofuran (THF) and Tetra methyl ammonium hydroxide (TMAH, 25% in methanol (MeOH), Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), deuterated polystyrene (d8-PS, Sigma Aldrich, Germany). All solvents were filtered through glass fiber filter of 0.3 µm pore size (Whatman, Altmann Analytical, Germany; pretreated at 500 °C/4 h).

Instrumentation and calibration

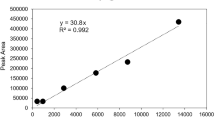

MNPs analysis was performed as outlined in published literature19,38,39,66,104 by using Py-GC-MS. The instrument set-up consisted of a micro furnace pyrolyzer (EGA/Py-3030D; FrontierLabs, Japan) with an auto-shot sampler (AS1020E; FrontierLabs, Japan), which was coupled with a GC-MS (6890N-5973MSD; Agilent Technologies). All the quantifiers have been chosen by taking into consideration the secondary reactions that may happen during the pyrolysis process105,106, but these reactions are largely irrelevant in highly diluted, complex environmental samples. Such reactions are reported mainly in artificial experimental setups where selected compounds are present at relatively high concentrations. In natural samples, the much higher dilution and the presence of multiple reactants for potential pyrolysis products (e.g., HCl) suggest that these reactions occur only to a negligible extent, if at all. Our analyses showed no evidence of such effects, although they cannot be completely excluded. Moreover, the measurement was performed in Single Ion Monitoring (SIM) mode, which enhances the sensitivity of the target compound by focusing on characteristic ions of target polymers (Supplementary Table 1). This also reduces background noise from complex airborne matrices and allows reliable quantification of polymers at trace levels, providing lower detection limits and improved accuracy compared with full scan analysis. A detailed description of the instrument settings and procedural parameters can be found in the supplementary information (Supplementary Table 9). The external calibration of the device was carried out using both liquid and solid standards. For calibration, individual polymer standards were dissolved and diluted in appropriate organic solvents prior to pyrolysis, including DCM used for C-PA6, C-PC, C-PS, HFIP for C-PET, acetone for C-PMMA, and a mixture of THF with DCM for C-PVC, according to their solubility107 and C-PE, C-PP, CTT, TTT and MDI-PUR were weighed as solid standards (1.0-16 µg) in pyrolysis cups. For C-PE and C-PP, conventional solvent dissolution was not feasible due to their non-polar, crystalline nature. Following Goßmann et al.19, we therefore employed a one-point calibration based on the lowest calibration point, which provides only semi-quantitative estimates. Alternative approaches, such as dilution in inert matrices, were considered but not applied, as they can introduce variability in recovery. Reported concentrations for C-PE and C-PP should thus be interpreted as semi-quantitative values. The current study used d8-PS in DCM as an internal standard with 20 µL of 125 µg mL-1 of solution injected (equivalent to 2.5 µg per cup) into pyrolysis cups along with analytes. For quantification, the ratio of peak areas of the respective selected marker compounds (Supplementary Table 1) to the peak areas of the internal standard (here m/z 98 from styrene trimer) was plotted against the mass of polymer used to get the calibration curve104. Each curve was plotted with 95% confidence and prediction bands, and the calibration linearity for each polymer was calculated as the determination coefficient (r2) value using OriginPro 2023 (Supplementary Fig. 5). 20 µL of TMAH solution (12.5% in methanol, Sigma Aldrich, Germany) was added to each pyrolysis cup for online derivatization and thermochemolysis to enhance the signal sensitivity for C-PET and C-PC39,66. The marker compounds for C-PP, C-PE, C-PVC*, CTT and TTT were not affected by TMAH addition to the pyrolysis cups66,104. A summary of marker compounds, quantifier ions, linear equation, R2 value, Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) is highlighted in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table 1).

MNPs collection and analysis

PM samples (PM10 and PM2.5 fractions simultaneously) were collected at Torgauer Straße, Leipzig, Germany (51.35° N, 12.42° E) using two separate DIGITEL (DHA-80) high-volume samplers (Supplementary Fig. 6). The roadside site, located within the urban area, represents an upper-limit exposure scenario due to its high traffic density. Sampling was conducted over a two-week period (01 to 14 September 2022), which provides a focused and detailed snapshot of MNPs composition under conditions of strong traffic influence. This setup offers the advantage of capturing peak urban exposure levels at fine size resolution of PM and generating high-quality baseline data for health risk estimation. At the same time, the restricted spatial and temporal scope limits the representativeness of our findings for other environments (e.g., suburban or rural) and prevents assessment of seasonal or long-term variability. A more representative picture could be obtained in future research by including diverse sites (urban and rural background) and conducting longer-term sampling to reflect broader variability in MNPs concentrations. The sampler was operated at a flow rate of 500 L min-1 for 24 hours, following Ambient air- European Standards108,109. For the collection of airborne particles, the samplers were equipped with quartz fiber filters (Munktell MK 360; Ø=150 mm). There are fine and coarse fractions of PM in PM10 samples, but PM2.5 samples only contain fine fractions. We calculated the PM10-2.5, a coarse fraction of PM, by subtracting the PM2.5 concentration from the PM10 concentration. The total mass load of collected PM samples were determined gravimetrically by weighing filters before and after sampling under controlled laboratory conditions (temperature and humidity).

An 18 mm punch (~254 mm2 of area) from the sampled filter was placed into a pyrolytic cup along with an internal standard and TMAH for analysis. The direct sample introduction without any pretreatment, as used in previous studies20,37,43,58,110,111 is ideal for saving time and avoiding sample manipulations.

Analysis of carbonaceous constituents in PM samples

The carbonaceous aerosol fractions, EC and OC, were analyzed using a thermo-optical instrument (EC/OC analyzer: Sunset Laboratory Inc., USA) in accordance with EUSAAR2112. A filter punch (1.41 cm2) from the sampled filter area was taken and analyzed for carbon parameters using an EC/OC analyzer.

Calculations and statistical analysis

Detection and Quantification limits of the instrument

The LOD and LOQ in absolute mass (µg) for each polymer as absolute mass were calculated using:

where σ denotes the standard deviation of the peak area of the lowest standard concentration, and s denotes the slope of the calibration curve113.

Carbon sum parameters

Calculated carbon sum parameters are mentioned below using the following equations:

The term (OC/EC) min is the minimum OC/EC ratio, and 1.6 is the factor which is used to calculate the particulate fraction of organic matter from OC in urban aerosol samples.114,115

MNPs inhalation

In the present study, we calculated the amount of MNPs that have the potential to enter the human body (Age group = 20 to 59 years) through inhalation in the outdoor environment with the following equation:

Where IR represents the average inhalation rate (0.83 m3/hour), T represents outdoor exposure time (4 hours/day), and C represents the daily average concentration of ∑MNPs20,32,116. However, as detailed time-activity data were not available for this study, future assessments should incorporate local activity surveys or sensitivity analyses to capture variability in exposure better.

Health risk assessments and polymer-specific toxicity

The Relative Risk (RR) associated with exposure to FMPs was estimated using a log-linear exposure-response model widely utilized in environmental epidemiology to quantify the health burden attributable to air pollutants. The following equation was applied:

Where X is the measured FMPs concentration, X₀ is the background concentration of PM₂.₅ (set at 3 µg/m³)68, β is the risk coefficient, taken as 0.15 for cardiopulmonary mortality and 0.23 for lung cancer mortality, following WHO guidelines68,117.

To quantify the proportion of mortality attributable to FMPs exposure, the Attributable Fraction (AF) was calculated using68,117,118:

Where RR is calculated from Eq. (8). This helps to estimate the proportion of disease burden that could be prevented if PM2.5 concentrations were reduced to background levels, which refers to the concentration of PM2.5 that would exist in the absence of anthropogenic emissions, including microplastics.

The chemical toxicity associated with distinct polymer types is a key factor in assessing the ecological risks of MNPs. The potential hazards associated with each polymer were assessed since PM10MNPs represent the highest contribution of each polymer in this study. Based on this, the Polymer Hazard Index (PHI) was calculated specifically for PM10MNPs using the following equation42.

Where Sn is the hazard score assigned to each polymer type based on its toxicological properties42, Pn is the proportion of that polymer within the PM10MNPs.

Stastistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed to evaluate differences in polymer abundances between FMPs and CMPs. Pairwise comparisons for each polymer were conducted using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (two-sided), a non-parametric method suitable for small sample sizes and non-normally distributed environmental data. Results are reported as medians, test statistic Wilcoxon (W), and p-values, with significance considered at p < 0.05. Moreover, to assess the overall compositional divergence between the two size classes and identify key polymer drivers, we performed PCA on centered and standardized polymer abundance data. The first two principal components were used to visualize clustering of samples and the loadings of individual polymers.

In addition to that, in the present study, a probability density function test was performed as per Chen et al.24. From the daily intake of MNPs dataset, a statistical analysis from KDE was applied to analyze MNPs exposure distributions, providing a smooth probability density function without arbitrary binning. It helped to identify dominant inhalation exposure levels across PM10MNPs, FMPs, and CMPs. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate the data distribution and goodness of fit. By smoothing the data, KDE improves exposure risk characterization and supports daily intake estimates. This method enhances statistical reliability, enabling a more precise evaluation of high-risk exposure zones in urban air and strengthening the study’s microplastic inhalation risk assessment. All statistical analyses were conducted in OriginPro 2023, and graphical outputs were generated accordingly.

Quality control (QC) and quality assurance (QA)

QC and QA measures have been implemented during the whole sampling, preparation, and analysis to ensure the accuracy and reliability of data while minimizing contamination risks. All laboratory apparatus, including glassware and steel ware, was cleaned with ultrapure water and pure ethanol before use. The drying procedure was conducted within a Class II biological safety cabinet (Claire pro B-2-130, laminar flow hood, Berner, sample protection mode), which utilizes HEPA‑filtered downward laminar airflow to protect both the samples and the work area from airborne contamination. The chemicals used in this study were filtered with a 0.3 µm pore-sized glass fiber filter and stored in a pre-cleaned glass bottle. During all the analytical steps, no plastic material was used; a cotton laboratory coat and nitrile gloves were worn, and a clean laminar flow bench was used to process all the samples and standard preparation procedures. To ensure accurate measurements, solid standards were weighed in pyrolysis cups (Eco Cups 80 LF, Frontier Labs, Japan), which were pre-cleaned to avoid contamination with a precision microbalance (Sartorius Cubis MSE2.7S-000-DM). Variabilities in the preparation of calibrants, samples and with the instrument were corrected using internal standards119. Quartz fiber filters were heated at 850 °C for 3 hours before collecting the PM10 and PM2.5 samples. To preserve the integrity of the collected samples, they were stored at −20 °C until analysis. Additionally, field blanks were placed during sample collection procedures, which were processed similarly to routine laboratory sample preparation procedures. The final concentration of the samples in this study is reported after the blank subtraction. To avoid any overestimation of the results, all sample data were raw-corrected on a raw data basis (subtraction of peak area ratios) before quantification. To illustrate the order of magnitude, we have also calculated the blank concentration of each quantified polymer. The overall average value of blanks was found to be 3.9 ± 0.7 ng/m3 (Supplementary Fig. 7). During the analysis of samples by Py-GC-MS, blank cups were also placed to check any carryover signals and cross-contamination from the previous sample analyzed. The reproducibility of the instrument was thoroughly checked throughout the sequence by evaluating the d8-PS signals. During pyrolysis, the system is frequently cleaned by measuring multiple instrument blanks (GC runs without injections) to ensure accurate analysis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in Excel sheet format at Zonedo120 via: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17424212.

References

Hartmann, N. B. et al. Are We Speaking the Same Language? Recommendations for a definition and categorization framework for plastic debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 1039–1047 (2019).

Eberhard, T., Casillas, G., Zarus, G. M. & Barr, D. B. Systematic review of microplastics and nanoplastics in indoor and outdoor air: identifying a framework and data needs for quantifying human inhalation exposures. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 34, 185–196 (2024).

González-Pleiter, M. et al. Occurrence and transport of microplastics sampled within and above the planetary boundary layer. Sci. Total Environ. 761, 143213 (2021).

Aves, A. R. et al. First evidence of microplastics in Antarctic snow. Cryosphere 16, 2127–2145 (2022).

Napper, I. E. et al. Reaching new heights in plastic pollution—preliminary findings of microplastics on Mount Everest. One Earth 3, 621–630 (2020).

Allen, S. et al. Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment. Nat. Geosci. 12, 339–344 (2019).

Evangeliou, N. et al. Atmospheric transport is a major pathway of microplastics to remote regions. Nat. Commun. 11, 3381 (2020).

Kole, P. J., Löhr, A. J., Van Belleghem, F. & Ragas, A. Wear and tear of tyres: a stealthy source of microplastics in the environment. IJERPH 14, 1265 (2017).

Yang, Z. et al. Is incineration the terminator of plastics and microplastics?. J. Hazard. Mater. 401, 123429 (2021).

Perera, K., Ziajahromi, S., Bengtson Nash, S., Manage, P. M. & Leusch, F. D. L. Airborne microplastics in indoor and outdoor environments of a developing country in South Asia: abundance, distribution, morphology, and possible sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 16676–16685 (2022).

Narmadha, V. V. et al. Assessment of microplastics in roadside suspended dust from urban and rural environment of Nagpur, India. Int J. Environ. Res 14, 629–640 (2020).

Tian, X. et al. Plastic mulch film induced soil microplastic enrichment and its impact on wind-blown sand and dust. Sci. Total Environ. 813, 152490 (2022).

Evangelou, I., Tatsii, D., Bucci, S. & Stohl, A. Atmospheric Resuspension of microplastics from bare soil regions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 9741–9749 (2024).

Abbasi, S. Microplastics washout from the atmosphere during a monsoon rain event. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 4, 100035 (2021).

Allen, S. et al. Examination of the ocean as a source for atmospheric microplastics. PLoS ONE 15, e0232746 (2020).

Yang, S., Brasseur, G., Walters, S., Lichtig, P. & Li, C. W. Y. Global atmospheric distribution of microplastics with evidence of low oceanic emissions. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 81 (2025).

Dris, R. et al. Microplastic contamination in an urban area: a case study in Greater Paris. Environ. Chem. 12, 592–599 (2015).

Gasperi, J. et al. Microplastics in air: are we breathing it in? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 1, 1–5 (2018).

Goßmann, I. et al. Occurrence and backtracking of microplastic mass loads including tire wear particles in northern Atlantic air. Nat. Commun. 14, 3707 (2023).

Luo, P. et al. A novel strategy to directly quantify polyethylene microplastics in PM 2.5 based on pyrolysis-gas chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 95, 3556–3562 (2023).

Morioka, T., Tanaka, S., Kohama-Inoue, A. & Watanabe, A. The quantification of the airborne plastic particles of 0.43–11 μm: procedure development and application to atmospheric environment. Chemosphere 351, 141131 (2024).

Xu, L. et al. Characterization of atmospheric microplastics in Hangzhou, a megacity of the Yangtze river delta, China. Environ. Sci.: Atmos. 4, 1161–1169 (2024).

Kaushik, A. et al. Identification and physico-chemical characterization of microplastics in marine aerosols over the northeast Arabian Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 168705 (2024).

Chen, Y., Meng, Y., Liu, G., Huang, X. & Chai, G. Probabilistic estimation of airborne micro- and nanoplastic intake in humans. Environ. Sci. Technol. acs.est.3c09189. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c09189 (2024).

Mohamed Nor, N. H., Kooi, M., Diepens, N. J. & Koelmans, A. A. Lifetime accumulation of microplastic in children and adults. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 5084–5096 (2021).

Amato-Lourenço, L. F. et al. Presence of airborne microplastics in human lung tissue. J. Hazard. Mater. 416, 126124 (2021).

Prata, J. C. Airborne microplastics: Consequences to human health? Environ. Pollut. 234, 115–126 (2018).

Wu, B., Wu, X., Liu, S., Wang, Z. & Chen, L. Size-dependent effects of polystyrene microplastics on cytotoxicity and efflux pump inhibition in human Caco-2 cells. Chemosphere 221, 333–341 (2019).

Ji, Y., Wang, Y., Shen, D., Kang, Q. & Chen, L. Mucin corona delays intracellular trafficking and alleviates cytotoxicity of nanoplastic-benzopyrene combined contaminant. J. Hazard. Mater. 406, 124306 (2021).

Yan, X. et al. The complex toxicity of tetracycline with polystyrene spheres on gastric cancer cells. IJERPH 17, 2808 (2020).

Kirchsteiger, B., Materić, D., Happenhofer, F., Holzinger, R. & Kasper-Giebl, A. Fine micro- and nanoplastics particles (PM2.5) in urban air and their relation to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Atmos. Environ. 301, 119670 (2023).

WHO. Dietary and Inhalation Exposure to Nano- and Microplastic Particles and Potential Implications for Human Health. (World Health Organization, 2022).

EEA. European Environment Agency (EEA, 2024). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9−2023-0233-AM-355-355_EN.pdf (2024).

IUCN. INC-5 - Plastic Pollution Treaty (IUCN, 2024).

Trainic, M. et al. Airborne microplastic particles detected in the remote marine atmosphere. Commun. Earth Environ. 1, 64 (2020).

Chen, Q. et al. Long-range atmospheric transport of microplastics across the southern hemisphere. Nat. Commun. 14, 7898 (2023).

Gregoris, E. et al. Microplastics analysis: can we carry out a polymeric characterisation of atmospheric aerosol using direct inlet Py-GC/MS? J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 170, 105903 (2023).

Goßmann, I., Süßmuth, R. & Scholz-Böttcher, B. M. Plastic in the air?! - Spider webs as spatial and temporal mirror for microplastics including tire wear particles in urban air. Sci. Total Environ. 832, 155008 (2022).

Goßmann, I. et al. Unraveling the Marine Microplastic Cycle: The First Simultaneous Data Set for Air, Sea Surface Microlayer, and Underlying Water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 16541–16551 (2023).

Goßmann, I., Wirth, C. & Scholz-Böttcher, B. M. Reliable thermal mass quantification of PVC – An ongoing challenge. Microplastics and Nanoplastics (2025, in press).

Niranjan, R. & Thakur, A. K. The toxicological mechanisms of environmental soot (black carbon) and carbon black: focus on oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways. Front. Immunol. 8, 763 (2017).

Lithner, D., Larsson, Å & Dave, G. Environmental and health hazard ranking and assessment of plastic polymers based on chemical composition. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 3309–3324 (2011).

Chen, Y. et al. Quantification and characterization of fine plastic particles as considerable components in atmospheric fine particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. acs.est.3c06832. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c06832 (2024).

Kau, D. et al. Fine micro- and nanoplastics concentrations in particulate matter samples from the high alpine site Sonnblick, Austria. Chemosphere 352, 141410 (2024).

Brahney, J., Hallerud, M., Heim, E., Hahnenberger, M. & Sukumaran, S. Plastic rain in protected areas of the United States. Science 368, 1257–1260 (2020).

Akhbarizadeh, R. et al. Suspended fine particulate matter (PM2.5), microplastics (MPs), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in air: Their possible relationships and health implications. Environ. Res. 192, 110339 (2021).

Revell, L. E., Kuma, P., Le Ru, E. C., Somerville, W. R. C. & Gaw, S. Direct radiative effects of airborne microplastics. Nature 598, 462–467 (2021).

Caracci, E. et al. Micro(nano)plastics in the atmosphere of the Atlantic Ocean. J. Hazard. Mater. 450, 131036 (2023).

Allen, D. et al. Microplastics and nanoplastics in the marine-atmosphere environment. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 393–405 (2022).

Bergmann, M. et al. White and wonderful? Microplastics prevail in snow from the Alps to the Arctic. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax1157 (2019).

Jahandari, A. Microplastics in the urban atmosphere: Sources, occurrences, distribution, and potential health implications. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 12, 100346 (2023).

Pomata, D. et al. Plastic breath: quantification of microplastics and polymer additives in airborne particles. Sci. Total Environ. 932, 173031 (2024).

Akyüz, M. & Çabuk, H. Meteorological variations of PM2.5/PM10 concentrations and particle-associated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the atmospheric environment of Zonguldak, Turkey. J. Hazard. Mater. 170, 13–21 (2009).

Panko, J., Hitchcock, K., Fuller, G. & Green, D. Evaluation of tire wear contribution to PM2.5 in urban environments. Atmosphere 10, 99 (2019).

Tolis, E. et al. Chemical characterization of particulate matter (PM) and source apportionment study during winter and summer period for the city of Kozani, Greece. Open Chem. 12, 643–651 (2014).

Grigoratos, T., Gustafsson, M., Eriksson, O. & Martini, G. Experimental investigation of tread wear and particle emission from tyres with different treadwear marking. Atmos. Environ. 182, 200–212 (2018).

Dierkes, G. et al. Quantification of microplastics in environmental samples via pressurized liquid extraction and pyrolysis-gas chromatography. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 411, 6959–6968 (2019).

Mizuguchi, H. et al. Direct analysis of airborne microplastics collected on quartz filters by pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 171, 105946 (2023).

Hann, S. et al. Investigating options for reducing releases in the aquatic environment of microplastics emitted by (but not intentionally added in) products Final Report (2018).

KBA. kraftfahrt-bundesamt-Stock by vehicle class 1960 to 2024. https://www.kba.de/DE/Statistik/Fahrzeuge/Fahrzeugarten/fahrzeugarten_node.html (2024).

Gao, Z. et al. On airborne tire wear particles along roads with different traffic characteristics using passive sampling and optical microscopy, single particle SEM/EDX, and µ-ATR-FTIR analyses. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1022697 (2022).

Goehler, L. O. et al. Relevance of tyre wear particles to the total content of microplastics transported by runoff in a high-imperviousness and intense vehicle traffic urban area. Environ. Pollut. 314, 120200 (2022).

Brahney, J. et al. Constraining the atmospheric limb of the plastic cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2020719118 (2021).

Plastic Europe. Plastics—the Fast Facts 2024. https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-fast-facts-2024/ (2024).

Fan, C., Huang, Y.-Z., Lin, J.-N. & Li, J. Microplastic constituent identification from admixtures by Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy: The use of polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and nylon (NY) as the model constituents. Environ. Technol. Innov. 23, 101798 (2021).

Fischer, M. & Scholz-Böttcher, B. M. Simultaneous trace identification and quantification of common types of microplastics in environmental samples by pyrolysis-gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 5052–5060 (2017).

Wright, S. L., Ulke, J., Font, A., Chan, K. L. A. & Kelly, F. J. Atmospheric microplastic deposition in an urban environment and an evaluation of transport. Environ. Int. 136, 105411 (2020).

Wu, C.-H. et al. Evaluation of PM2.5 bound microplastics and plastic additives in several cities in Taiwan: Spatial distribution and human health risk. Sci. Total Environ. 959, 178213 (2025).

UBA. Umweltbundesamtes (UBA) Schwerpunkt. Gesunde Luft (Healthy Air); UBA: Darmstadt, Germany, 2019. https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/schwerpunkt-1-2019-gesunde-luft (2019).

Samland, M., Badeke, R., Grawe, D. & Matthias, V. Variability of aerosol particle concentrations from tyre and brake wear emissions in an urban area. Atmos. Environ.: X 24, 100304 (2024).

Svensson, N., Engardt, M., Gustafsson, M. & Andersson-Sköld, Y. Modelled atmospheric concentration of tyre wear in an urban environment. Atmos. Environ.: X 20, 100225 (2023).

Pöschl, U. Atmospheric Aerosols: Composition, Transformation, Climate and Health Effects. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 44, 7520–7540 (2005).

Zhang, H. et al. In Microplastics in Terrestrial Environments (eds. He, D. & Luo, Y.) Vol. 95, 161–184 (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

Fox, S. et al. Physical characteristics of microplastic particles and potential for global atmospheric transport: a meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 342, 122938 (2024).

Irédon Adjama, I., Dave, H., Balarabe, B. Y. & Masiyambiri, V. & Marycleopha, M. et al. Microplastics in cosmetics and personal care products: impacts on aquatic life and rodents with potential alternatives. JSM 51, 2495–2506 (2021).

Haggam, A. et al. Improvement of asphalt properties using polymethyl methacrylate. OJOPM 04, 43–54 (2014).

Song, Y. K., Hong, S. H., Eo, S. & Shim, W. J. The fragmentation of nano- and microplastic particles from thermoplastics accelerated by simulated-sunlight-mediated photooxidation. Environ. Pollut. 311, 119847 (2022).

O’Brien, S. et al. There’s something in the air: A review of sources, prevalence and behaviour of microplastics in the atmosphere. Sci. Total Environ. 874, 162193 (2023).

Burghardt, T. E. et al. Microplastics and road markings: the role of glass beads and loss estimation. Transp. Res. D: Transp. Environ. 102, 103123 (2022).

Knight, L. J., Parker-Jurd, F. N. F., Al-Sid-Cheikh, M. & Thompson, R. C. Tyre wear particles: an abundant yet widely unreported microplastic?. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 27, 18345–18354 (2020).

Sommer, F. et al. Tire abrasion as a major source of microplastics in the environment. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 18, 2014–2028 (2018).

Rochman, C. M., Hoh, E., Hentschel, B. T. & Kaye, S. Long-term field measurement of sorption of organic contaminants to five types of plastic pellets: implications for plastic marine debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 130109073312009. https://doi.org/10.1021/es303700s (2013).

Bond, T. C. et al. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: A scientific assessment. JGR Atmos. 118, 5380–5552 (2013).

Nzimande, M. C., Mtibe, A., Tichapondwa, S. & John, M. J. A review of weathering studies in plastics and biocomposites—effects on mechanical properties and emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Polymers 16, 1103 (2024).

WHO. Ambient (outdoor) air pollution. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health (2024).

Soltani, N. S., Taylor, M. P. & Wilson, S. P. Quantification and exposure assessment of microplastics in Australian indoor house dust. Environ. Pollut. 283, 117064 (2021).

Yadav, H., Sethulekshmi, S. & Shriwastav, A. Estimation of microplastic exposure via the composite sampling of drinking water, respirable air, and cooked food from Mumbai, India. Environ. Res. 214, 113735 (2022).

Borgatta, M. & Breider, F. Inhalation of Microplastics—a Toxicological Complexity. Toxics 12, 358 (2024).

Bodor, K., Szép, R. & Bodor, Z. The human health risk assessment of particulate air pollution (PM2.5 and PM10) in Romania. Toxicol. Rep. 9, 556–562 (2022).

Arregocés, H. A., Rojano, R. & Restrepo, G. Health risk assessment for particulate matter: application of AirQ+ model in the northern Caribbean region of Colombia. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 16, 897–912 (2023).

Huang, F., Pan, B., Wu, J., Chen, E. & Chen, L. Relationship between exposure to PM2.5 and lung cancer incidence and mortality: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 8, 43322–43331 (2017).

Wagner, M. et al. State Sci. Plast. Chem. - Identifying Addressing Chem. Polym. Concern https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10701706 (2024).

Jenner, L. C. et al. Detection of microplastics in human lung tissue using μFTIR spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 831, 154907 (2022).

Ragusa, A. et al. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ. Int. 146, 106274 (2021).

Horvatits, T. et al. Microplastics detected in cirrhotic liver tissue. eBioMedicine 82, 104147 (2022).

Leslie, H. A. et al. Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environ. Int. 163, 107199 (2022).

Nihart, A. J. et al. Bioaccumulation of microplastics in decedent human brains. Nat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03453-1 (2025).

Kuntz, V., Zahn, D. & Reemtsma, T. Quantification and occurrence of 39 tire-related chemicals in urban and rural aerosol from Saxony, Germany. Environ. Int. 194, 109189 (2024).

Prokić, M. D., Radovanović, T. B., Gavrić, J. P. & Faggio, C. Ecotoxicological effects of microplastics: examination of biomarkers, current state and future perspectives. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 111, 37–46 (2019).

Marfella, R. et al. Microplastics and nanoplastics in atheromas and cardiovascular events. N. Engl. J. Med 390, 900–910 (2024).

Zhu, L. et al. Tissue accumulation of microplastics and potential health risks in human. Sci. Total Environ. 915, 170004 (2024).

Zurub, R. E., Cariaco, Y., Wade, M. G. & Bainbridge, S. A. Microplastics exposure: implications for human fertility, pregnancy and child health. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1330396 (2024).

Li, J., Li, J., Zhai, L. & Lu, K. Co-exposure of polycarbonate microplastics aggravated the toxic effects of imidacloprid on the liver and gut microbiota in mice. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 101, 104194 (2023).

Goßmann, I., Halbach, M. & Scholz-Böttcher, B. M. Car and truck tire wear particles in complex environmental samples – a quantitative comparison with “traditional” microplastic polymer mass loads. Sci. Total Environ. 773, 145667 (2021).

Li, B. et al. Co-pyrolysis of waste polyester enameled wires and polyvinyl chloride: Evolved products and pyrolysis mechanism analysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 169, 105816 (2023).

Coralli, I., Giorgi, V., Vassura, I., Rombolà, A. G. & Fabbri, D. Secondary reactions in the analysis of microplastics by analytical pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 161, 105377 (2022).

Bivens, A. Polymer-to-Solvent Reference Table for GPC/SEC. https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/technicaloverviews/public/5991-6802EN.pdf (2016).

EN 12341:2023 - Ambient air - Standard gravimetric measurement method for the determination of the PM10 or PM2,5 mass concentration of suspended particulate matter. iTeh Standards. https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/9e212b76-3171-40b4-9d69-07409bc6bf75/en-12341-2023.

EN 14907:2005 - Ambient air quality - Standard gravimetric measurement method for the determination of the PM2,5 mass fraction of suspended particulate matter. iTeh Standards https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/1291e744-10a4-4c9f-aecd-df4cc16a090d/en-14907-2005.

Jones, N., Wendt, J., Wright, S., Hartner, E. & Groeger, T. Analysis of microplastics in environmental samples by pyrolysis/thermal desorption-(GC)xGC-TOFMS. (2021).

Pipkin, W. et al. Into the nanograms─sensitive detection of microplastics in passively sampled indoor air using F-splitless pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectrometry. ACS EST Air acsestair.3c00035. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestair.3c00035 (2024).

Cavalli, F., Viana, M., Yttri, K. E. & Genberg, J. Toward a standardised thermal-optical protocol for measuring atmospheric organic and elemental carbon: the EUSAAR protocol. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 3, 79–89 (2010).

Ishimura, T. et al. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of mixtures of microplastics in the presence of calcium carbonate by pyrolysis-GC/MS. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 157, 105188 (2021).

Lim, H.-J. & Turpin, B. J. Origins of Primary and Secondary Organic Aerosol in Atlanta: Results of Time-Resolved Measurements during the Atlanta Supersite Experiment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 4489–4496 (2002).

Turpin, B. J. & Lim, H.-J. Species Contributions to PM2.5 Mass Concentrations: Revisiting Common Assumptions for Estimating Organic Mass. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 35, 602–610 (2001).

USEPA. Risk assessment guidance for superfund. human health evaluation manual (Part A). https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-09/documents/rags_a.pdf (1989).

Ostro, B. Assessing the environmental burden of disease at national and local levels. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42909/9241591463.pdf?sequence=1 (2004).

WHO. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide (WHO, 2021).

Seeley, M. E. & Lynch, J. M. Previous successes and untapped potential of pyrolysis–GC/MS for the analysis of plastic pollution. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-023-04671-1 (2023)

Kaushik, A. Composition, interactions and resulting inhalation risk of micro- and nano-plastics in urban air [Data set]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17424213 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Leibniz Association (Berlin, Germany) under the Leibniz Collaborative Excellence Programme, project ‘AirPlast’ (Grant: K389/2021).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H. and A.K. conceptualized the study. A.K. conducted sampling, Py-GC-MS measurements, data analysis, and wrote the main manuscript, including preparation of figures, tables, and supplementary material. A.E.P. and M.v.P. contributed to data interpretation, scientific guidance, and manuscript refinement. B.S.B. provided instrumentation, methodological support, and scientific input. H.H. supervised the project and provided critical feedback. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Joel D. Rindelaub and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Suryasarathi Bose and Nandita Basu. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaushik, A., Peter, A.E., van Pinxteren, M. et al. Composition, interactions and resulting inhalation risk of micro- and nano-plastics in urban air. Commun Earth Environ 6, 985 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02980-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02980-0