Abstract

Reaching carbon neutrality requires innovative and scalable carbon sequestration technologies. Here, we present an enhanced ex-situ mineral carbonation method using South China Sea seawater and calcium-rich additives for carbon dioxide storage. We conducted high-pressure (50-500 atm) laboratory experiments using calcium oxide, calcium hydroxide, and wollastonite, and performed numerical geochemical simulations. Our key finding is that calcium oxide in seawater achieves the highest carbonate yield, with geochemical models indicating that the complex ionic composition of seawater significantly enhances precipitation compared to simple brines. Additionally, an analytical Monte Carlo economic analysis projects that such efficiency could reduce sequestration costs by 15%. We conclude that seawater-based carbonation is a viable strategy for permanent carbon dioxide storage, offering a practical path for scaling carbon management in coastal regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China is recognized as one of the world’s largest emitters of carbon dioxide (CO₂), with over 12,466 Mt of emissions generated annually across its energy and industrial sectors. In response to the mounting environmental and climate concerns associated with these emissions, the Chinese government has adopted an ambitious dual-carbon strategy: to reach peak emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Achieving these goals requires deploying large-scale carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies. Due to its extensive coastline and proximity to surrounding seas, China is particularly well-positioned to explore and implement ocean-based CCUS strategies1,2,3,4,5,6.

Marine-based sequestration solutions, including direct CO₂ injection into deep-sea reservoirs and hydrate formation beneath the seafloor, have attracted increasing attention as feasible options for long-term CO₂ storage. For further details, see Supplementary Text 1.

Globally, there is a growing consensus on the urgency of removing atmospheric CO₂ to stabilize climate systems. Marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR) technologies, including ocean alkalinity enhancement (OAE), direct ocean injection, and accelerated mineral carbonation, are gaining traction due to the ocean’s vast buffering capacity, long-term sequestration potential, and its ability to absorb CO₂ with comparatively minimal ecological disruption. Among mCDR approaches, strategies that leverage calcium- and magnesium-rich minerals to promote stable carbonate formation have shown considerable promise in theoretical frameworks and early-stage experimental validations7,8,9,10,11,12.

Ocean alkalinity enhancement using alkaline materials like CaO and olivine has been proposed as a viable route for atmospheric CO₂ removal and mitigation of ocean acidification. For instance, an experimental work demonstrated that coastal ocean alkalinization using olivine dissolution could reduce sea surface pCO₂, thereby enhancing CO₂ drawdown and offering ancillary benefits to vulnerable ecosystems such as coral reefs. However, scalability challenges remain, including the need for large quantities of material, secondary mineral precipitation, and ecological risks related to chemical perturbations in seawater13.

Other studies have examined the physical and biological pathways influencing ocean carbon storage. Briggs et al. (2020)14 identified particle fragmentation as a key mechanism driving carbon loss in the mesopelagic zone, underscoring the need to integrate particle disaggregation dynamics into carbon flux models. Similarly, Fuhr et al. (2022)15 provided kinetic insights into olivine weathering in seawater, revealing that while olivine dissolution enhances alkalinity and calcium carbonate formation, it is also constrained by secondary mineral formation that limits long-term sequestration potential. These findings highlight both the promise and complexity of mineral-based ocean CDR approaches. Tagliabue et al. (2023)16 examined ocean iron fertilization (OIF) and its impact on marine ecosystems. While OIF initially promotes phytoplankton growth and enhances carbon export, it may intensify ecosystem pressures and lead to trade-offs in marine biodiversity. These observations emphasize the need for integrated environmental assessments of mCDR strategies.

Despite encouraging progress, several critical knowledge gaps remain. Existing experimental studies often employ synthetic brines that lack the ionic complexity of real seawater, thereby failing to capture key geochemical interactions, especially those involving ions like Mg²⁺ and SO₄²− that strongly influence carbonate precipitation. Moreover, many studies focus narrowly on idealized reaction kinetics or equilibrium assumptions without addressing the influence of high-pressure CO₂ dissolution, real-world salinity variations, and dynamic temperature conditions17,18,19,20,21,22,23. These oversights limit current findings’ generalizability and practical relevance, particularly for implementation in coastal regions with high emission intensities.

This study aims to address these gaps by proposing an ex-situ mineral carbonation strategy that integrates experimental validation with thermodynamic modelling and economic analysis. Using real seawater from the South China Sea and industrially accessible calcium-rich materials, namely CaO, Ca(OH)₂, and wollastonite, the research investigates carbonate precipitation under elevated CO₂ pressures (ranging from 50 to 500 atm) and varying salinities. The work systematically compares natural seawater with synthetic NaCl solutions, highlighting seawater’s superior performance in facilitating carbonate formation due to its intrinsic buffering capacity and multivalent ion content. PHREEQC-based geochemical simulations complement these experiments to reveal the effects of CO₂ partial pressure, temperature, and solution chemistry on carbonate mineral stability. In addition to the scientific findings, the study incorporates a Monte Carlo-based economic sensitivity analysis to assess the viability and scalability of the proposed approach. This analysis provides a holistic framework often missing in previous works by examining cost drivers such as CO₂ capture, calcium additive procurement, and operational energy use. The results offer practical insights into the economic and technical barriers to deployment, focusing on regions such as the South China Sea that align with China’s dual-carbon agenda.

In this study, a comprehensive integration of experimental and thermodynamic modelling methods was conducted, focusing on high-pressure (50-500 atm) ex-situ carbonation using South China Sea and contrasting the efficacy of CaO, Ca(OH)₂, and wollastonite. Moreover, cost evaluation analysis, a multidisciplinary approach rarely encountered in existing mCDR literature, was also conducted to further shed light on the practical application of the proposed technology. The findings enhance our understanding of ocean-based CO₂ sequestration pathways and offer a scalable and environmentally responsible framework for implementation in high-emission coastal areas. By bridging the gaps between scientific feasibility, geochemical mechanisms, and economic viability, this work contributes to the practical deployment of marine carbon dioxide removal technologies, supporting national and global carbon neutrality objectives.

Results and discussions

pH changes with pressure, temperature, and salinity

The effects of different parameters on solution pH were investigated using variable operating conditions, including pressure (1−500 atm), temperature (274−198 K), and water salinity (Distilled water- 19000 ppm). Figure 1a presents solution pH versus different pressures at a constant temperature of 298 K and two different solutions, including 19000 ppm NaCl and SW with a salinity of 19000 ppm. As shown in this figure, increasing pressure directly impacts pH, where the higher the pressure, the lower the solution pH, regardless of the solution type. The minimum pH is achieved at 500 atm, and the highest at the lowest pressure of 1 atm. Another observation from this figure is that solution type impacts solution pH, where solutions prepared in DW resulted in lower pH than those prepared in SW. Considering 1 atm as the lowest pressure, the solution pH of 3.81 and 3.56 was achieved in SW and DW, respectively. The pH values decrease to 2.52 and 2.34 by increasing pressure to 500 atm using SW and DW. Overall, it can be seen that the difference between pH values of the DW and SW is between 7%-14% in the pressure range of the experiments.

The observed reduction in pH when pressure is increased from 1-500 atm at a constant temperature of 298 K can be attributed to several interrelated parameters. As the CO2 solubility increases with increasing pressure, it forms more carbonic acid, dissociating into hydrogen ions and lowering the pH. In addition, changes in water structure, ion activity, and acid-base equilibria under high pressure contribute to the enhanced dissociation of acids and an increased concentration of H⁺ ions. Consequently, these processes explain the decrease in pH with growing pressure because of the synergistic influence of these components24,25,26.

Figure 1b presents the changes in solution pH at variable temperatures and constant pressure of 100 atm using two different solutions of SW and DW. As shown in this figure, temperature increment results in a lower pH for both solutions, where the minimum pH is achieved at the highest temperature of 298 K and the highest pH is achieved at the lowest temperature of 274 K. In addition, using SW instead of DW resulted in a higher pH regardless of the temperature. Considering the minimum temperature of 274 K, the solution pH is 4.95 and 4.47 while using SW and DW, respectively. On the other hand, increasing the temperature to its maximum value of 298 K resulted in a solution pH of 3.47 and 3.01 while using SW and DW, respectively.

The observed pH decline with increasing temperature is likely due to the reduction in CO₂ solubility, which causes a relative increase in the dissolved CO₂(aq) concentration and shifts the carbonate equilibrium toward more acidic species. While solubility decreases with temperature, the dissociation constants (K₁, K₂) also move, which may result in enhanced dissociation of CO₂ once dissolved, particularly in a closed high-pressure system. This balance between solubility and speciation can explain the non-linear temperature effect on pH, as reported in high-pressure CO₂-water systems27,28,29.

Although CO₂ solubility in water generally decreases with increasing temperature, the observed reduction in pH between 274 K and 298 K is attributed to the nature of the system used in this study. The setup maintained a constant CO₂ pressure of 100 atm, allowing the solution to remain in equilibrium with the gas phase during heating. Under these conditions, the temperature rise promotes greater reactivity of dissolved CO₂, including its conversion to carbonic acid and subsequent dissociation into hydrogen and bicarbonate ions. At the same time, the natural buffering capacity of seawater, mainly from carbonate and bicarbonate species, becomes less effective at higher temperatures, allowing additional free H⁺ ions to accumulate. These combined effects result in a measurable decrease in pH, even though CO₂ solubility decreases with temperature. Importantly, all vessels were sealed during the process, and no degassing occurred. The same trends were observed at continuous pressures of 50 and 200 atm30,31,32.

It is important to clarify that although CO₂ solubility generally decreases with increasing temperature in closed systems, our experimental setup maintained a constant CO₂ partial pressure (100 atm) throughout the temperature variation experiments. This operational mode is thermodynamically distinct from a strictly closed CO₂–H₂O system, allowing for re-equilibration between the gas and aqueous phases at each temperature step. Under such conditions, rising temperature reduces the physical solubility of CO₂ but simultaneously enhances the kinetics of CO₂ hydration and the dissociation of carbonic acid (H₂CO₃ → H⁺ + HCO₃−). Moreover, the buffering capacity of seawater weakens at elevated temperatures due to reduced stability of carbonate and bicarbonate species. As a result, more protons (H⁺) accumulate in solution with limited neutralization, contributing to a net decrease in pH. These coupled thermodynamic and chemical effects explain the observed pH drop from 4.95 at 274 K to 3.47 at 298 K, despite the lower CO₂ solubility at higher temperatures. This trend is consistent with previous studies conducted under constant-pressure or open-system conditions where CO₂ is supplied continuously or maintained in excess27,30,32.

Figure 1c presents the changes in solution pH versus salinity at a constant pressure of 100 atm and temperature of 298 K. As shown in this figure, increasing salinity increases solution pH using both SW and NaCl. The highest pH value is achieved at a maximum salinity of 19000 ppm, and the lowest is achieved at the lowest salinity of 1000 ppm for both brines. Considering solutions prepared by SW, the lowest and the highest pH values of 2.35 and 3.47 are achieved in salinities of 1000 and 19000 ppm, respectively. The values are reduced to 2.08 and 3.11, respectively, using NaCl as the solution medium. It is worth mentioning that the solution pH while using DW is 2.17.

The observed increase in solution pH with salinity can be explained through both physical and chemical mechanisms supported by the carbonate system theory. At higher salinities, the solubility of CO₂ in water decreases due to a salting-out effect, which limits the amount of dissolved CO₂ available to form carbonic acid, thereby reducing proton generation and pH reduction31,33. Moreover, natural seawater contains a complex mixture of ions, such as HCO₃−, CO₃²−, Mg²⁺, B(OH)₄−, and SO₄²−, that contribute to its substantial buffering capacity. This buffering system resists pH changes by stabilizing the carbonate equilibrium, unlike DI water-based NaCl solutions, which lack these components and are more prone to pH fluctuations from CO₂ uptake or base addition19,21,27,29,34. Furthermore, the presence of divalent cations like Mg²⁺ and the borate system in seawater can influence the dissociation extent of added alkaline materials such as Ca(OH)₂, reducing the effective release of OH− ions and modulating pH rise. In contrast, the absence of these competing equilibria in NaCl solutions allows for more complete dissociation and a stronger pH shift. These compositional differences explain why seawater typically maintains a higher and more stable pH (~8.1) than DI-based NaCl solutions under similar conditions. A detailed examination of carbonate speciation and alkalinity reinforces this interpretation21,23,29.

pH changes with base addition

The effects of different calcium sources on pH changes were investigated by adding variable amounts of wollastonite, CaO, and Ca(OH)2 to the solution. In this part, experiments were conducted at a pressure of 100 atm and a temperature of 298 K using two solutions of SW and NaCl with TDS of 19000 ppm. Figure 2a presents changes in pH with different loading of wollastonite to the solutions. This figure shows that increasing wollastonite dosage increases solution pH in both SW and NaCl solutions. The minimum pH is achieved when the minimum dosage of wollastonite is used, and the maximum pH is achieved when the maximum dosage of wollastonite is added to the solution. Another point to consider is that solutions prepared with NaCl always resulted in lower pH than those prepared with SW. Considering the wollastonite dosage of 0.01 g L−1 as the minimum dosage, pH was 3.51 and 3.48 when SW and NaCl were used. The values were increased to 10.11 and 8.88 when wollastonite dosage increased to 10 g L−1 in the presence of SW and NaCl.

Changes in solution pH with Ca(OH)2 concentration to the solution are shown in Fig. 2b. As shown in this figure, solution pH increases with increasing Ca(OH)2 dosage, where the highest pH is achieved at a maximum dosage of 10 g L−1 and the lowest pH is achieved at the lowest Ca(OH)2 dosage. A minimum Ca(OH)2 concentration of 0.01 (g L−1) has resulted in the lowest pH of 3.59 and 3.49 while using SW and NaCl as the solution. On the other hand, increasing Ca(OH)2 to 10 resulted in a maximum solution pH of 11.25 and 10.04 when using SW and NaCl.

Figure 2c presents pH changes with variable dosages of CaO with different solutions prepared by NaCl and SW. This figure shows that increasing CaO loading positively impacts solution pH, where maximum pH is achieved at a maximum CaO dosage of 10 g L−1 and minimum pH at a minimum dosage of 0.01 g L−1. For all the solutions tested, pH values were consistently higher with SW than NaCl, regardless of the dosage amount. At the minimum dosage of 0.01 g L−1, the minimum pH of 3.64 and 3.52 were achieved with SW and NaCl, and the values were increased to 12.21 and 11.63 by increasing the CaO dosage to 10 g L−1.

Ca(OH)₂ (calcium hydroxide) is highly soluble in water, dissociating almost completely into Ca²⁺ and OH− ions according to Eq. 1. The immediate release of hydroxide ions (OH−) increases the alkalinity of the solution, driving the pH upwards significantly. Due to its strong base behaviour, Ca(OH)₂ has the most pronounced impact on pH when added to NaCl and seawater solutions. The direct dissociation and high solubility enable a rapid increase in pH, even in buffered environments like seawater, as the hydroxide ions dominate the solution chemistry. CaO (calcium oxide) is highly reactive with water, forming Ca(OH)₂ through an exothermic hydration process, as shown in Eq. 2. Once hydrated, CaO effectively behaves like Ca(OH)₂, dissociating into Ca²⁺ and OH− ions, significantly increasing the pH. The conversion from CaO to Ca(OH)₂ is rapid, making it an excellent material for applications that require immediate alkalinity adjustments. The primary difference between CaO and Ca(OH)₂ is that CaO first undergoes hydration before dissociation into OH−. Still, its overall impact on pH is as substantial as Ca(OH)₂ once the hydration reaction is complete35,36,37.

The reactivity of CaO, Ca(OH)₂, and wollastonite in seawater–CO₂ systems differs due to their distinct dissolution behaviours and response to pH conditions. CaO reacts rapidly in aqueous solutions, producing Ca²⁺ and OH−, sharply raising the pH. Ca(OH)₂ behaves similarly, though its dissolution is more moderate. In contrast, wollastonite (CaSiO₃) dissolves more gradually, and its reactivity depends strongly on the surrounding pH. Under more acidic conditions, the dissolution of wollastonite is often represented by a proton-promoted reaction as shown in Eq. 3. However, in our experiments, the pH values typically ranged from 3.4−5.5, depending on additive type and CO₂ pressure. While these values are above the strongly acidic range, they still allow for some H-driven dissolution, especially early in the reaction when local proton concentrations may be higher. This pathway may not fully capture the complexity of wollastonite’s behaviour at these pH levels. Other mechanisms, such as hydrolysis or weak ligand-promoted reactions, likely contribute, especially in buffered systems like seawater. For this reason, Eq. 4 is used here as a simplified reference, and we acknowledge that multiple parallel pathways are likely active under our conditions38,39,40,41.

The dissolution of wollastonite (CaSiO₃) under CO₂-rich conditions is commonly described by the proton-promoted reaction pathway (Eq. 3), where H⁺ ions attack the silicate lattice to release Ca²⁺ and silicic acid. While this reaction is typically dominant in strongly acidic environments (pH < 3), our experiments recorded pH values between ~3.4 and 5.5, depending on CO₂ pressure and additive dosage. Although not strongly acidic, this range still supports appreciable H⁺ concentrations (10−³ to 10−⁴ mol/L), which are sufficient to initiate partial acid-driven dissolution, particularly in early stages of the reaction or in systems with limited buffering capacity, such as the NaCl solutions. However, it is important to recognize that under these mildly acidic conditions, additional mechanisms likely contribute to wollastonite dissolution. These include hydrolysis reactions facilitated by water molecules and ligand-promoted pathways involving bicarbonate or other aqueous species. Therefore, Eq. 4 should be interpreted as a representative but not exclusive mechanism of wollastonite reactivity under our conditions2,42,43,44,45,46.

In seawater, buffering species such as bicarbonates (HCO₃−) and sulphates (SO₄²−) help stabilize the pH, which moderates the impact of the added materials. However, with their strong basicity, CaO and Ca(OH)₂ can still overcome this buffering effect more effectively than wollastonite due to their rapid and complete dissociation. The results demonstrate that CaO and Ca(OH)₂ have the most substantial impact on pH due to their high reactivity, solubility, and the rapid release of hydroxide ions, significantly increasing alkalinity. Conversely, Wollastonite has the lowest impact because of its slower dissolution rate and lower reactivity in neutral to slightly alkaline solutions. These differences highlight the distinct chemical behaviours of these calcium-containing compounds when interacting with seawater and NaCl solutions43,44,47,48.

Carbonate precipitation

The effect of wollastonite loading on calcium carbonate precipitation was investigated by loading different dosages of wollastonite into the solution at constant CO2 pressure and temperatures of 100 atm and 298 K, respectively. Two different solutions, including SW and NaCl, with a TDS of 19000 ppm, were used in these experiments. Figure 3a presents the changes in carbonate precipitation versus wollastonite dosage. As shown in this figure, increasing wollastonite dosage increases CaCO3 precipitation, where the highest amount of carbonate is achieved at the highest amount of wollastonite dosage of 10 g L−1, and the lowest amount of carbonate is achieved at the lowest amount of wollastonite dosage of 0.01 g L−1. In addition, utilizing SW instead of NaCl also resulted in higher carbonate precipitation, regardless of the dosage amount. Considering SW as the solution medium, the minimum and maximum amounts of carbonate precipitation are 0.003 and 0.025 g L−1; these values are 0.001 and 0.018 g L−1 while using NaCl after 24 h of static reaction at 298 K under 100 atm CO₂ pressure. Although these quantities are relatively small, they represent the early-stage formation of solid carbonate under limited reaction time and fixed calcium input. This corresponds to <1% of the theoretical maximum based on the added Ca-source, suggesting that only a small portion of the available calcium participated in precipitation during the initial 24 h period. These values were primarily used to compare reactivity between media and highlight the influence of solution composition on carbonate formation efficiency under otherwise identical conditions.

Figure 3b presents carbonate precipitation versus Ca(OH)2 dosage at constant CO2 pressure and temperatures of 100 atm and 298 K, respectively. In this part, increasing Ca(OH)2 dosage also resulted in higher carbonate precipitation, where the maximum value was achieved when Ca(OH)2 dosage was at its highest value of 10 g L−1. In addition, using SW instead of NaCl was also influential in increasing the carbonate precipitation, which was evident in all the dosage amounts. Considering the minimum dosage of 0.01 g L−1, the minimum dosage resulted in minimum carbonate precipitation of 0.006 and 0.002 g L−1 while using SW and NaCl, respectively. These values were increased to their maximum values of 0.039 and 0.024 g L−1 by increasing the Ca(OH)2 dosage to 10 g L−1.

Figure 3c presents changes in carbonate precipitation versus different CaO loading with two different SW and NaCl solution mediums with 19000 ppm TDS. As shown in this figure, increasing CaO dosage resulted in increased carbonate precipitation with both solutions of SW and NaCl. The minimum amount of carbonate was produced with the minimum dosage of CaO of 0.01 g L−1, and the maximum amount of carbonate was precipitated with the maximum amount of calcium carbonate (10 g L−1). While using SW as the solution medium, the minimum and maximum carbonate precipitation of 0.009 and 0.072 g L−1 were achieved, and these values were 0.003 and 0.059 g L−1 while using NaCl.

The higher carbonate precipitation observed with CaO compared to Ca(OH)₂ and wollastonite is primarily due to its rapid hydration and subsequent release of Ca²⁺ ions. When CaO is added to water, it quickly reacts with H₂O to form Ca(OH)₂ in an exothermic reaction, immediately increasing Ca²⁺ and OH− ions in solution. Under high CO₂ pressure (100 atm) and moderate temperature (298 K), the Ca²⁺ ions readily react with the dissolved CO₂, forming CO₃²− ions, precipitating as CaCO₃. The high solubility and reactivity of CaO, particularly under these conditions, provide a rapid and ample source of Ca²⁺ ions, making it the most efficient material for carbonate precipitation. On the other hand, Ca(OH)₂, while still highly reactive and soluble, does not undergo the additional hydration step that CaO does and thus releases Ca²⁺ ions at a slower rate than CaO. This leads to slightly lower carbonate precipitation, though still considerable due to the availability of Ca²⁺ ions. Wollastonite, by contrast, is much less reactive in neutral or slightly alkaline solutions. It dissolves slowly, releasing Ca²⁺ ions over a longer period. This slower dissolution limits the amount of Ca²⁺ available to react with CO₂ during the experiment, resulting in the least carbonate precipitation. Thus, the trend reflects the differing solubility and reactivity of the materials, with CaO showing the highest precipitation due to its fast and complete reaction, followed by Ca(OH)₂, and finally, wollastonite, which reacts far more gradually49,50,51,52.

Although the data in Fig. 3b, c are presented in grams to align with experimental dosing and cost analysis, we recognize the importance of evaluating the results on a molar basis to compare the stoichiometry between calcium input and carbonate precipitation more accurately. Future work should explore this molar-based perspective, which could help identify scenarios with net-positive CO₂ mineralization, particularly under low-dosage conditions. Such an approach may provide deeper insights into the overall carbon efficiency of each additive.

Effects of CO2 pressure on carbonate precipitation

The effect of CO2 pressure on carbonate precipitation was investigated by increasing CO2 pressure from 100−500 atm at a constant temperature of 298 K and solid dosage (wollastonite, Ca(OH)2, and CaO) of 6 g L−1. Figure 4a presents changes in carbonate precipitation with different CO2 pressures while adding 6 g L−1 of wollastonite. As shown in this figure, increasing CO2 pressure directly affects carbonate precipitation; as the pressure rises, the carbonate precipitation increases. Moreover, utilizing SW instead of NaCl also resulted in higher carbonate precipitation, regardless of the pressure. Considering a CO2 pressure of 500 atm as the maximum pressure, carbonate precipitates of 0.049 and 0.034 g L−1 were achieved using SW and NaCl, respectively. The values were reduced to 0.017 and 0.011 g L−1 using CO2 at 50 atm pressure.

Figure 4b presents carbonate content with variable CO2 pressure in the presence of 6 g L−1 of Ca(OH)2 at a constant temperature of 298 K. This figure shows that the maximum amount of carbonate is achieved at 500 atm CO2 pressure, and the minimum carbonate precipitation is achieved at a minimum CO2 pressure of 50 atm. Considering 50 atm as the minimum CO2 pressure resulted in carbonate precipitation of 0.026 and 0.015 g L−1, using SW and NaCl, respectively. Accordingly, the results of carbonate precipitation with 6 g L−1 of CaO addition to the solutions of NaCl and SW are shown in Fig. 4c. This figure shows that the maximum carbonate precipitation is achieved at the highest CO2 pressure of 500, while the lowest amount is achieved at 50 atm CO2 pressure. These results also suggest that CO2 pressure directly impacts carbonate precipitation, where the higher the CO2 pressure, the higher the carbonate precipitation. Considering CO2 pressure of 50 atm as the lowest CO2 pressure, carbonate precipitation of 0.039 and 0.026 is achieved with SW and NaCl, respectively. In comparison, the values are increased to 0.148 and 0.093 g L−1 by increasing CO2 pressure to 500 atm. The presence of CaCO3 in the final product is confirmed by TGA, FESEM, XRD, and FT-IR analysis as shown in Supplementary Figs. 1–4. For further details, see Supplementary Text 2.

The effect of increasing CO₂ pressure on carbonate precipitation involves both positive and negative factors due to its dual impact on pH and solubility. As CO₂ pressure rises, the solubility of CO₂ in the solution also increases, leading to more dissolved carbonic acid (H₂CO₃) in the system. This higher concentration of dissolved CO₂ enhances the availability of CO₃²− ions once the carbonic acid dissociates, which is critical for forming carbonate precipitates such as CaCO₃. This increase in CO₂ solubility can accelerate the rate of carbonate precipitation, as more CO₃²− ions are available to interact with Ca²⁺ ions from CaO, Ca(OH)₂, or wollastonite, promoting carbonate formation. However, as CO₂ pressure rises, the formation of carbonic acid increases, leading to a reduction in pH. This more acidic environment can slow carbonate precipitation, as CO₃²− ions become protonated to form HCO₃−, reducing the concentration of free carbonate ions available for rainfall. In this acidic environment, the dissolution of Ca²-containing compounds like Ca(OH)₂ and CaO may be affected, and the balance between carbonate formation and dissolution becomes more complex53,54,55,56.

The overall effect of increasing CO₂ pressure is generally positive for carbonate precipitation because the increased solubility of CO₂ tends to outweigh the impact of reduced pH, especially in systems with a strong buffering capacity or high availability of Ca²⁺ ions. However, there is a trade-off: in systems with low buffering capacity, extreme pressure increments could lead to pH levels that are too low, potentially inhibiting carbonate formation. Therefore, the effectiveness of pressure increases will depend on how well the system balances the increased solubility of CO₂ with the pH-driven changes in carbonate chemistry. In addition, Calcium oxide (CaO) outperforms alternatives like wollastonite (CaSiO₃) and calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂) due to its high reactivity, rapid hydration, and favourable dissolution kinetics. When CaO reacts exothermically with water, it forms Ca(OH)₂, dissociating quickly into Ca²⁺ and OH− ions, increasing ion availability and solution alkalinity to promote carbonate precipitation. Its hydration and dissociation rapidly elevate pH, driving carbonate-bicarbonate equilibrium toward CO₃²− formation. In contrast, wollastonite dissolves slowly, and Ca(OH)₂ lacks the additional hydration step, making its ion release less effective. Furthermore, CaO’s performance under moderate temperatures and high pressure aligns well with carbonate precipitation kinetics, unlike wollastonite, which often requires acidic conditions50,57,58.

Effects of carbonate precipitation on total alkalinity and environmental considerations

In interpreting the results of carbonate precipitation, it is important to distinguish between two CO₂ sequestration pathways: dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and solid carbonate formation. While elevated DIC levels reflect the system’s capacity to absorb and buffer CO₂ in solution, forming solid carbonates such as calcite or aragonite represents a more stable and permanent sequestration route. Early precipitation may sometimes reduce the aqueous CO₂ carrying capacity, but mineral formation enhances overall sequestration permanence under appropriate conditions. This study considers both mechanisms when evaluating system performance.

The effect of carbonate precipitation on total alkalinity was investigated by measuring the total alkalinity with different materials used during carbonation experiments. In this part, the constant concentration of 6 g L−1 of wollastonite, Ca(OH)2, and CaO was subjected to carbonation experiments in the presence of SW. Figure 5 presents the values of total alkalinity with variable CO2 pressure. This figure shows that increasing CO2 pressure has decreased the total alkalinity values for all three tested materials. Another observation from this figure is that total alkalinity with CaO is consistently lower than that of Ca(OH)2 and wollastonite, regardless of the CO2 pressure. The total alkalinity at 50 atm CO2 pressure is 3485, 4073, and 3594 µmol/L for wollastonite, Ca(OH)2 and CaO, respectively, and the values are further reduced to 2855, 2104, and 1196 µmol/L at 500 atm CO2 pressure.

These observations suggest that total alkalinity is in a reverse relationship with CO2 pressure and carbonate precipitation. Carbonate precipitation is increased with increasing CO2 pressure while reducing the total alkalinity. The reason is that precipitation of carbonate minerals reduces the efficiency of the alkalinization process and the sequestration/storage capacity of CO2, hence reducing total alkalinity. The relationship between CO2 pressure, carbonate precipitation, and total alkalinity is interconnected. As CO2 pressure increases, more CO2 dissolves in the solution, leading to higher concentrations of carbonate ions, which promotes the precipitation of carbonate minerals like CaCO₃. This precipitation removes carbonate ions from the solution, reducing total alkalinity. Since alkalinity represents the water’s ability to neutralize acids, its reduction diminishes the system’s capacity to buffer against further CO2 absorption. Consequently, the efficiency of the alkalinization process and the sequestration capacity for CO2 are reduced because fewer carbonate and bicarbonate ions remain in the solution to neutralize additional CO2. Thus, carbonate precipitation limits total alkalinity and CO2 sequestration potential59,60,61.

Despite the crucial role played by pH, the increased carbonate precipitation within SW is brought about by its better buffer capability, ionic interaction complexity, and CO₂ dissolution dynamics rather than just the pH. The naturally occurring carbonate-bicarbonate buffer within SW stabilizes the pH and provides a higher amount of HCO₃− and CO₃²− ions, which enhance the efficient precipitation of CaCO₃ upon the introduction of Ca²⁺. The presence of Mg²⁺ and SO₄²− ions also influence carbonate nucleation and phase stability and may enhance aragonite precipitation relative to calcite. Furthermore, the unique CO₂ solubility behaviour and high total dissolved solids (TDS) within SW reduce CO₂ escape, drive carbonate equilibria toward precipitation, and enhance sequestration efficiency. Our experimental results confirm that despite the pH adjustment to equivalence, SW still provides superior carbonate formation compared with NaCl solutions, which indicates these other factors are also critical. To illustrate this point further, we will present the carbonate speciation model results and discuss the role of the chemistry of seawater in mineral carbonation efficiency59,60,62,63. This clarification validates the fact that superior precipitation is not merely the effect of a high-pH medium but results from the inherent chemical advantages of SW.

While precipitation of CaCO₃ reduces the pool of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), thereby limiting the ocean’s capacity to absorb additional atmospheric CO₂, it simultaneously promotes long-term carbon sequestration by stabilizing CO₂ in mineral form. This distinction is critical: DIC-based sequestration favours keeping CO₂ in dissolved forms (HCO₃−, CO₃²−) to maximize oceanic uptake potential, while solid carbonate precipitation enhances storage permanence by removing CO₂ from the aqueous phase. Thus, the observed decline in DIC during CaCO₃ formation is not necessarily detrimental but reflects a shift in sequestration pathway, from transient dissolved forms to stable mineralized carbon49,58,59.

The environmental impact assessment of potential modification of ocean alkalinity and its ecological consequences is crucial for any future accelerated mineral carbonation CO₂ sequestration. The addition of calcium-rich compounds like CaO and Ca(OH)₂ has been proposed to increase the local alkalinity, disturbing the marine carbonate equilibria, which may affect calcifying organisms such as corals and shell-forming species sensitive to pH. In addition, carbonate precipitation may induce local sedimentation with associated changes in the benthic habitat and affect the marine food chain. Trace impurities in natural additives may introduce small concentrations of heavy metals or other elements into the ocean, forming an additional risk. These effects can be mitigated by strategies that include high-purity materials to reduce contaminants in the water, dilution, and hence controlled dispersion of additives to reduce localized impacts, along with regular and robust monitoring of relevant environmental variables around application locations, such as changes in pH and alkalinity. Even considering these factors, the process offers considerable advantages over direct CO₂ injection because it stabilizes CO₂ in a solid carbonate form that effectively avoids acidification by leveraging the ocean’s natural buffering capacity to mitigate adverse effects. This will approach a viable, environmentally sustainable option for long-term CO₂ sequestration14,58,64,65.

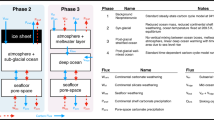

Geochemical Simulation

Geochemical simulations were conducted using PHREEQC (version 3.7) with the phreeqc.dat thermodynamic database to complement the experimental results and assess the thermodynamic feasibility of carbonate precipitation. These simulations aimed to evaluate how variations in CO₂ pressure, temperature, salinity, and calcium source (CaO, Ca(OH)₂, wollastonite) influence carbonate mineral saturation, aqueous speciation, pH, and alkalinity in seawater and NaCl media (19,000 ppm TDS). Simulations were performed under equilibrium conditions at 298 K and 100 atm CO₂ pressure, consistent with the experimental design, using measured seawater composition and NaCl solutions prepared with deionized water. While kinetic factors were not modelled, the use of finely ground solids (≤75 µm), elevated CO₂ pressures, and mildly acidic pH (4.5–6.5) in both lab and model settings justified the equilibrium assumption. The goal was not to capture reaction rates, but to understand whether carbonate precipitation was thermodynamically favourable. The simulation’s saturation indices and pH behaviour trends aligned with the experimental results, suggesting that the systems approached partial equilibrium.

The modelling results showed trends that closely matched those observed experimentally. It is worth noting that the saturation indices of calcite, aragonite, and wollastonite increased noticeably with rising CO₂ pressure, as shown in Fig. 6a. Among the additives tested, CaO and Ca(OH)₂ produced the most notable increases in SI, particularly at pressures above 300 atm, suggesting their strong potential to shift the system toward supersaturation and drive rapid carbonate precipitation. In contrast, wollastonite exhibited a comparatively modest SI increase over the same range due to its lower solubility and slower reaction kinetics. These patterns are consistent with the experimental findings, where CaO demonstrated the highest efficiency in promoting carbonate formation.

Interestingly, temperature changes between 274 K and 298 K caused a slight but systematic decline in the calcite saturation index, particularly in systems containing CaO, as shown in Fig. 6b. This behaviour is expected, as higher temperatures reduce the solubility of CO₂ in water and, consequently, the availability of carbonate ions. Nevertheless, CaO’s high reactivity and rapid hydration offset this thermodynamic limitation, allowing effective carbonation even at elevated temperatures.

Salinity was also found to notably influence SI values, as shown in Fig. 6c. Simulations comparing synthetic NaCl solutions to natural seawater indicated that seawater consistently achieved higher saturation indices. This can be attributed to its intrinsic buffering capacity and the presence of multivalent ions, such as Mg²⁺ and SO₄²−, which enhance ionic strength and stabilize carbonate minerals. Overall, the simulation results provide a strong thermodynamic basis for understanding the superior performance of seawater-based systems in carbonate precipitation experiments29,66,67.

The results presented in Fig. 7 were generated using PHREEQC (v3.7) to explore equilibrium conditions in systems containing seawater or synthetic saline solutions with added calcium-bearing materials. These simulations focused on how different salinities, additive types (CaO, Ca(OH)₂, wollastonite), and CO₂ pressures affect the chemical environment, particularly the pH, calcium concentrations, and saturation indices of common carbonate minerals. Simulations were carried out at 298 K and included fixed CO₂ partial pressures ranging from 100 to 500 atm. Rather than attempting to replicate reaction rates, the goal was to better understand the conditions under which precipitation becomes thermodynamically favourable. The seawater composition used in the model was based on experimental measurements, while the NaCl solution was defined at 19,000 ppm to match laboratory conditions. Calcium sources were treated as reactive solids that dissolved into the aqueous phase until equilibrium was reached. Through these calculations, the model provided insight into the relationship between solution chemistry and carbonate mineral formation potential across various realistic environmental conditions. These insights complement the experimental findings and help validate the trends observed in precipitation behaviour under different scenarios.

As CO₂ pressure increased, the solution pH dropped from 3.8 to 2.5, while total alkalinity decreased from 4000−2000 µmol/L, as shown in Fig. 7a. This inverse relationship highlights the acidifying effect of CO₂ dissolution, which leads to the formation of carbonic acid and drives the carbonate equilibrium toward lower pH values. The reduction in alkalinity can be explained by the progressive removal of carbonate and bicarbonate ions from solution through the precipitation of CaCO₃, as reflected by changes in carbonate speciation in the simulations.

Interestingly, the saturation indices of both calcite and aragonite exhibited a strong positive correlation with increasing CO₂ pressure as shown in Fig. 7b, supporting the view that elevated CO₂ partial pressures favour supersaturation of carbonate minerals. This shift in thermodynamic conditions promotes nucleation and crystal growth, especially under high-pressure environments where CO₂ solubility and, by extension, enhanced carbonate availability. Furthermore, an analysis of dissolved carbon speciation revealed how aqueous CO₂ transforms into bicarbonate and carbonate ions as pressure rises, as shown in Fig. 7c.

The simulations showed a clear decrease in CO₃²− and HCO₃− concentrations, suggesting their effective removal from the aqueous phase through carbonate precipitation. HCO₃− remained the predominant species at intermediate pressures, while CO₃²− concentrations declined sharply under more acidic conditions at higher pressures. Together, these simulation outcomes strengthen the experimental findings and provide a detailed thermodynamic rationale for the observed trends in pH, precipitation yield, and alkalinity. They further demonstrate that CaO performs exceptionally well as a carbonation agent in seawater systems, particularly under elevated CO₂ pressures, thanks to its ability to quickly increase saturation indices and drive mineral formation, even in the chemically complex environment of natural seawater.

To better understand how solution composition affects carbonate formation, we modelled the distribution of dissolved carbonate species in seawater and NaCl solution (19,000 ppm) under identical conditions: 298 K, 100 atm CO₂, and pH around 5. The results, shown in Fig. 8, highlight meaningful differences in the chemical behaviour of the two systems. In the seawater model, a larger share of the total dissolved carbon existed in the form of bicarbonate ions (HCO₃−), about 60%, with a smaller portion (30%) as dissolved CO₂ (CO₂(aq)). On the other hand, the NaCl solution showed a more balanced split between these two forms, each accounting for roughly 45%. As expected at this pH level, the amount of carbonate ion (CO₃²−) remained low in both cases. This difference helps explain why more carbonate precipitate was observed in the seawater system during experiments. The higher bicarbonate level in seawater indicates stronger natural buffering, which helps keep the pH stable even as reactions progress. That stability creates better conditions for carbonate to form and grow. In contrast, the NaCl solution has fewer natural buffers, so more CO₂ stays in its molecular form, which slows the buildup of solid carbonates18,19,23,24. Altogether, this speciation model supports the experimental trend and shows that seawater isn’t just beneficial because of its pH but has a built-in capacity to manage CO₂ reactivity more effectively.

Thermodynamic observations of carbonate precipitation under variable conditions

Increased CO₂ pressure enhances its solubility in seawater, leading to the greater formation of carbonic acid (H₂CO₃), which then dissociates into bicarbonate (HCO₃−) and carbonate (CO₃²−) ions, promoting CaCO₃ precipitation. Higher pressures significantly boost precipitation rates, with optimal results at 500 atm. Temperature also plays a key role, with calcite dominating at lower temperatures and aragonite becoming more favourable above 298 K due to differences in Gibbs free energy stability. The ionic strength of seawater (TDS ~ 19,000 ppm) reduces CO₂ solubility but enhances alkalinity, shifting the equilibrium toward carbonate precipitation, explaining why seawater outperforms NaCl solutions.

Although initial CO₂ pressurization notably reduces pH (e.g., to ~2.5 at 500 atm), this value does not represent the final pH during carbonate formation. The system’s alkalinity increases by introducing calcium-bearing additives such as Ca(OH)₂ and CaO, enabling the pH to rise toward a more favourable range for carbonate precipitation. This buffering effect is particularly pronounced in seawater due to its natural ionic composition. Thus, the optimal conditions (pH 8.0–8.5) refer to the pH range at which maximum carbonate precipitation occurs, based on equilibrium modelling and supported by experimental trends. In addition, maintaining an optimal pH of 8.0-8.5 is crucial, as excessive OH− levels can lead to impurity formation, such as dolomite (CaMg(CO₃)₂) and huntite (Mg₃Ca(CO₃)₄) in Mg²⁺-rich environments, or CaSO₄·2H₂O (gypsum) in the presence of SO₄²− ions, which is thermodynamically more stable than CaCO₃. Controlling supersaturation is essential to prevent unwanted phases and ensure high-purity carbonate formation, particularly in industrial applications where Mg²⁺/Ca²⁺ ratios must be carefully managed to avoid contamination. These findings highlight that seawater, with its natural buffering capacity and ionic complexity, provides a highly effective medium for CO₂ sequestration, provided key reaction conditions such as pressure, temperature, and salinity are properly maintained62,68,69,70. Table 1 summarizes key findings of rate analysis and thermodynamic observations.

Economic analysis and practical applications of the mineral carbonation

The economic viability of the proposed accelerated mineral carbonation method is a critical factor to consider when assessing scalability and large-scale implementation. Considering that the process involves the addition of CO₂ through calcium-rich materials such as CaO, Ca(OH)₂, and wollastonite into seawater, several economic factors must be considered, including the cost of CO₂ capture, material availability, operational costs, and the potential for revenue generation through carbon credits.

One of the most substantial contributors to the total cost is the CO₂ capture expense. Current industrial capture costs range between US$ 40–80 per tonne of CO₂, while Direct Air Capture (DAC) is still significantly more expensive at $ 100–600 per tonne. As carbon capture technologies mature and benefit from learning curves and scaling effects, these costs are expected to decline. Sensitivity analysis highlights CO₂ capture as the single most impactful cost driver, with even modest cost reductions translating into notable overall savings63,71,72. For example, Metz and coworkers73 Estimate that a 10% reduction in capture costs could reduce the total sequestration cost by ~15%. To rigorously quantify economic uncertainty and parameter sensitivity, a Monte Carlo simulation was performed using @Risk (Palisade Corp.) in Excel with 10,000 iterations. This method allowed us to assess the impact of input variability on the projected cost of CO₂ sequestration and generate statistically robust estimates. Each economic parameter was assigned a probabilistic distribution based on market reports, literature values, and operational assumptions73,74,75,76:

-

CaO cost: Triangular distribution ($ 80 minimum, $ 110 most likely, $ 150 maximum per tonne)

-

Electricity price: Normal distribution (mean = $ 0.10/kWh, SD = $ 0.02)

-

CO₂ delivery, transport, and separation: Uniform distribution ($ 10–$ 30 per tonne)

-

Carbon credit value: Uniform distribution ($7.6–$50 per tonne, based on current and projected market prices)

-

Labour and process costs: Triangular or uniform distributions based on available engineering estimates

The model outputs include P10, P50 (median), and P90 values for the cost per tonne of CO₂ removed. Results showed a median price of $ 136 per tonne, with a 90% confidence interval between $ 118 and $ 162. This range includes all major cost components, such as reagents, energy, labour, and equipment.

Figure 9a presents a tornado chart that visually summarizes the sensitivity analysis results. Each horizontal bar represents the influence of a ± 20% variation in a single parameter on the total cost of CO₂ removal. The length of the bar indicates how much impact that parameter has on the final cost. The parameters are ranked from most to least influential. The chart demonstrates that CO₂ capture cost is the most sensitive parameter, followed by material cost (especially CaO), electricity prices, and carbon credit values. For instance:

-

A 10% reduction in CO₂ capture cost leads to a 15% decrease in total sequestration cost.

-

A 20% increase in CaO cost results in a $ 10–$ 25 per tonne rise in total removal cost, depending on other parameters.

-

An increase in carbon credit value by $ 10 per tonne can reduce net sequestration cost by around 15%, improving financial feasibility.

Fig. 9: Economical analysis of CO2 mineralization in the South China Sea.

Operational and energy costs also influence the overall economics, but to a lesser extent. Labour costs were included but showed minimal impact, confirming that labour-intensive processes are not a major cost driver in this model. This figure helps identify the most impactful levers for cost optimization. If efforts are focused on reducing capture costs and sourcing cheaper CaO or renewable electricity, the overall system could become cost-competitive with other carbon removal strategies. Figure 9a extends the analysis by depicting a scenario-based tornado diagram that models ±20% changes in economic input variables and shows their direct effect on the cost per tonne of CO₂ removed. This chart complements the probabilistic sensitivity analysis by offering deterministic insights into how individual variables influence the final cost when varied in isolation. Among all inputs, the CaO price again showed the highest leverage. A 20% increase in CaO cost leads to an estimated $ 25 per tonne increase in CO₂ removal cost. This is followed by the electricity price, where a 20% increase adds ~$ 10–15 per tonne, and CO₂ capture and delivery costs contribute substantially to the cost structure. Other parameters, such as carbonate precipitation efficiency and solid-liquid separation costs, had moderate effects, while labour and minor reagents had limited influence.

Figure 9b provide a comprehensive picture of uncertainty-driven and scenario-driven cost sensitivities. These analyses are crucial for identifying optimization pathways and prioritizing future investments, particularly in materials sourcing, renewable energy integration, and CO₂ supply chain logistics. Material cost assumptions for CaO, Ca(OH)₂, and wollastonite were $ 80–160 per tonne, consistent with bulk industrial pricing. These are generally stable but could be affected by regional supply chains. Sensitivity analysis indicates that a 20% increase in reagent cost leads to only a 5–10% increase in the final CO₂ removal cost, confirming that capture and energy costs remain the more influential factors. On the revenue side, carbon pricing represents an important economic lever. Carbon credit markets currently offer between $ 7.6 and $ 20 per tonne, with projections of $ 30–50 per tonne by 2030. A $ 10 increase in carbon credit value reduces the net CO₂ removal cost by ~15%, significantly enhancing viability in regulated markets. Operational costs for pressurizing CO₂, running high-pressure reactors, and preparing the calcium reagents are estimated at $ 10–30 per tonne of CO₂. Process efficiency improvements, such as better reactor insulation or renewable energy input, could yield 10–20% energy and operational cost savings. While initial investment for this technology may be 2–5 times higher than traditional geological CO₂ storage, long-term benefits include permanent carbon fixation, minimal leakage risk, and compatibility with local resource use (e.g., seawater and industrial minerals). Standardization, process optimization, and scale-up are expected to further reduce costs over time74,75,76,77,78.

Conclusions

This study introduced an integrated experimental and modelling framework to evaluate ex-situ mineral carbonation using natural seawater from the South China Sea and calcium-based additives, CaO, Ca(OH)₂, and wollastonite, under controlled high-pressure CO₂ conditions ranging from 50−500 atm. The results revealed that carbonate precipitation efficiency varied significantly with additive type, CO₂ pressure, and salinity. Among the additives tested, CaO achieved the highest carbonate yield, precipitating up to 1.82 g of CaCO₃ per litre under 500 atm and 298 K, followed by Ca(OH)₂ (1.65 g L−1) and wollastonite (1.08 g L−1). Seawater consistently outperformed synthetic NaCl solutions in promoting carbonate formation, primarily due to its complex ionic composition. The presence of Mg²⁺ and SO₄²− improved buffering capacity and stabilized pH between 4.5 and 6.5, favouring carbonate saturation. This was validated through PHREEQC simulations, which showed saturation indices (SI) for calcite and aragonite exceeding 1.5 under optimal conditions. The simulations provided thermodynamic upper-bound estimates for carbonate precipitation and speciation behaviour across various conditions. While this study assumed equilibrium to highlight potential limits, future work will incorporate kinetic constraints to more accurately model time-dependent behaviours. Although CaO and Ca(OH)₂ showed strong potential in enhancing carbonate precipitation, it’s important to recognize that their conventional production, through limestone calcination, can release substantial amounts of CO₂. This raises valid concerns about the overall carbon balance of the process. To ensure real net removal, future efforts should focus on sourcing calcium from low-emission or recycled materials, such as industrial by-products or methods that minimize associated CO₂ emissions. Life-cycle assessments will be essential in guiding the selection of materials that support both environmental and economic goals. Economic assessment using a Monte Carlo approach indicated that the minimum estimated sequestration cost could reach $ 58–72 per ton of CO₂, depending on the additive and CO₂ pressure applied. This suggests the approach is economically competitive, especially in regions with local calcium-rich materials and existing CO₂ point sources.

In conclusion, this work provides a scalable, experimentally validated, and economically informed pathway for marine-based CO₂ sequestration. By leveraging natural seawater and accessible mineral additives, it aligns with China’s dual-carbon goals and contributes to global carbon neutrality initiatives through a practical and environmentally sustainable approach. Future work should also move toward pilot-scale testing and longer-term environmental assessments to evaluate field performance, ecological safety, and regulatory feasibility. Expanding the geochemical model to include reaction kinetics would further improve understanding of system behaviour under practical operating timescales and enhance predictions of CO₂ uptake efficiency at scale.

Materials and methods

This study comprises two experimental parts. The solution pH is first measured with variable pressure, temperature, and water salinity. The impact of carbon-absorbing components such as wollastonite, Ca(OH)2, and CaO on the solution pH is also investigated in different operating conditions. The main reason for choosing these compounds is that China has vast natural wollastonite resources that can be used efficiently for mineral carbonation techniques. Moreover, the technical attractiveness of Ca(OH)2 and CaO as the most reactive forms of calcium is another reason for choosing these compounds for mitigating CO2 through ocean sequestration.

In the second part, calcium carbonate precipitation with the addition of the aforementioned additives was also investigated at different operating conditions. Two different aqueous phases were used: a solution with the composition resembling a sample taken from the South China Sea Water (SW) with TDS of 19000 ppm (1.9 wt%) and various concentrations of NaCl with a salinity of up to 19000 ppm. All aqueous solutions were prepared using Deionized water (DW). The flow chart of experimental procedure used in this study is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. For further details, see Supplementary Text 3.

Materials

The seawater used in the experiments was sourced from a coastal area in the South China Sea. Supplementary Table 1 presents the measured ion composition of the sea water used in this study. In addition, additives (CaO, Ca(OH)₂, and wollastonite) were prepared and used for the carbonation experiments. The physical properties of the additives are shown in Supplementary Table 2. For further details, see Supplementary Text 4.

pH measurement

This study prepared a series of solutions using natural seawater (SW) and deionized water (DW), with salinities adjusted up to 19,000 ppm. Each solution was subjected to varying operational conditions, including CO₂ pressures ranging from 1−500 atm and temperatures between 274 and 298 K. To assess the influence of calcium sources on solution chemistry, different doses (0.01−10 g L−1) of wollastonite, Ca(OH)₂, and CaO were added. The primary objective was to monitor changes in solution pH under these conditions.

pH measurements were carried out using a high-pressure pH probe (Mettler Toledo InPro 4260i), equipped with an Ag/AgCl reference electrode. The electrometric method was employed, where the potential difference (electromotive force, EMF) between the electrodes was recorded using a digital multimeter (Mettler ToledoTM). A back-pressure regulator ensured electrode safety and pressure stability throughout the tests. All pH values reported in this section correspond to post-CO₂ pressurization conditions; measurements were taken after the system had been pressurized with CO₂ and allowed to equilibrate. CO₂ was continuously injected for ~15 min before each test to eliminate residual gases and ensure complete saturation. A Brooks Instrument SLA Series CO₂ flow meter was used to deliver CO₂ at the desired rate.

The solution pH was calculated using the Nernst equation79,80. (Eq. 4), E is the measured EMF, E₀ is the standard electrode potential, R is the gas constant, F is Faraday’s constant, and T is the absolute temperature. The calibration method described by Mohammadian and coworkers24 was followed, involving calibration at three temperatures (283 K, 288 K, and 298 K) to determine accuracy and uncertainty. For further details, see Supplementary Text 5.

Carbonate precipitation

In addition to pH measurements, the experimental setup illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 9 was employed for carbonate precipitation experiments. The integrated high-pressure reactor system, equipped with syringes and ISCO pumps for precise CO₂ injection, temperature and pressure regulation instruments, and sampling ports, enabled controlled delivery of calcium-bearing additives (CaO, Ca(OH)₂, or wollastonite) into seawater or synthetic brine under CO₂-enriched conditions. Using the same reactor configuration for pH monitoring and carbonate precipitation ensures consistency across all experiments and enables direct correlation between solution chemistry and observed mineral formation. For further details, see Supplementary Text 5.

This study employed two distinct experimental protocols to quantify calcium carbonate precipitation resulting from the dissolution of calcium-rich additives into saline media under CO₂ pressure. The first set of experiments aimed to evaluate the effect of additive dosage on carbonate precipitation. Two base solutions were prepared: seawater (SW) and a synthetic NaCl (TDS 19,000 ppm) pre-equilibrated at room temperature. A range of additive dosages (0.01–10 g L−1) of wollastonite, Ca(OH)₂, and CaO were added to 1 L of each solution in high-pressure batch reactors. Each reactor was sealed and injected with CO₂ to achieve a constant pressure of 100 atm, and the system was maintained at 298 K. The mixture was stirred continuously for 24 h to allow sufficient time for dissolution, reaction, and carbonate precipitation. CO₂ pressure was held constant during the experiment via a regulator and monitored throughout. After reaction completion, the system was depressurized slowly to avoid degassing losses, and the contents were immediately filtered to collect solid precipitates using a 0.45 µm cellulose nitrate membrane. The solids were washed, dried at 60 °C, and weighed. pH was recorded at the start and end of each experiment, and the final calcium carbonate yield was calculated accordingly.

The second experimental setup focused on determining the influence of CO₂ partial pressure on calcium carbonate formation. The same two base solutions (SW and 19,000 ppm NaCl) were used for this series. Each solution was mixed with a fixed dosage (6 g L−1) of one of the three additives (wollastonite, CaO, or Ca(OH)₂). The system temperature was maintained at 298 K, while the CO₂ pressure was varied across a range of 50 to 500 atm. Once the target pressure was stabilized, the reactors were held under isothermal, isobaric conditions for 24 h with continuous stirring. The rest of the protocol, filtration, drying, and measurement of solids, was identical to the previous setup.

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the average values are reported. Blank tests (no additive) were also conducted under identical conditions to confirm negligible background precipitation. Solution pH and temperature were monitored before and after the experiment, and no notable air exposure occurred before CO₂ pressurization, thus minimizing atmospheric interference with carbonate chemistry.

Finally, the produced carbonate solids were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier-transform infra-red spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis, and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). XRD was performed using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation source in a 2θ range of 5°–70° at a scanning rate of 1°/min. Thermogravimetric (TGA) analysis was carried out using a Q600 (TA Instruments, USA) device in an air atmosphere with a heating rate of 10 °C/min up to 1000 °C. FT-IR analysis was performed using a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer after drying the carbonate samples at 105 °C overnight. The mid-infra-red region of 500 to 4000 cm−1 was used. Before analysis, all FTIR spectra were baseline-corrected using the built-in software tool (Bruker OPUS). Peak assignments were made by comparing observed bands to reference spectra reported in prior studies. In addition, the carbonation product samples were also analyzed using FESEM analysis. These procedures were followed from the previously published data in the literature51,56,57,81,82.

Geochemical simulation using PHREEQC

Geochemical simulations were performed using PHREEQC (version 3.7) and the phreeqc.dat thermodynamic database to comprehensively understand the system’s thermodynamic behaviour. These simulations complement the experimental findings by estimating the upper bounds of carbonate precipitation under controlled conditions. Two types of aqueous media were modelled: (1) natural seawater, with its composition based on detailed ionic measurements from our lab (Supplementary Table 1), and (2) a synthetic NaCl solution with a total dissolved solid (TDS) content of 19,000 ppm to simulate brine behaviour.

In all scenarios, CO2 was introduced as a fixed gas phase using the GAS_PHASE block, with pressures ranging from 50 to 500 atm, while temperatures varied between 274 and 298 K, mirroring the experimental setup. Each system was modelled under thermodynamic equilibrium assumptions, justified by the use of finely ground calcium-bearing solids (≤75 μm), elevated CO₂ pressures, and slightly acidic conditions (pH 4.5–6.5). These parameters enhance dissolution kinetics and facilitate near-equilibrium conditions, particularly in batch reactor systems.

The primary calcium sources considered in the simulations were CaO, Ca(OH)₂, and wollastonite, introduced via the EQUILIBRIUM_PHASES keyword. Their dissolution was allowed until the system reached saturation concerning carbonate phases. Although PHREEQC supports kinetic modelling via RATES blocks, no rate expressions were applied in this study. This is because the aim was not to capture time-dependent reaction pathways but to determine carbonate formation’s thermodynamic feasibility and upper-limit potential under favourable geochemical conditions.

-

Key simulation outputs included:

-

Saturation indices (SI) of calcite, aragonite, and dolomite,

-

Aqueous speciation of carbon (CO₂(aq), HCO₃−, CO₃²−) and calcium (Ca²⁺),

-

pH response to CO₂ pressure, temperature, and salinity variations,

-

Total alkalinity (µmol/L), and

-

Estimated mass of carbonate precipitation for each scenario.

Special attention was paid to supersaturation indices, which were calculated after CO₂ dissolution to reflect the chemical state of the solution during mineral precipitation. This approach aligns with the experimental setup, where CO₂ was injected at defined pressures and allowed to equilibrate before any precipitation was measured. The results were visualized regarding SI trends versus pressure and temperature, speciation shifts across pH ranges, and comparative charts between seawater and NaCl-based solutions. While equilibrium-based models do not capture kinetic constraints, they provide valuable insights into the thermodynamic favorability of mineral carbonation processes and seawater alkalinity enhancement under high-pressure CO₂ conditions. Importantly, these simulations help identify optimal conditions for maximizing carbonate precipitation, which can inform future kinetic modelling and practical implementation. For further details, see Supplementary Text 6.

Sensitivity analysis and economic assessment

Deterministic and probabilistic cost analyses were conducted to assess the economic feasibility of the mineral carbonation process under study. The cost model aimed to estimate the total expense of CO₂ removal per tonne, incorporating the main contributors to operational costs: reagent procurement, energy consumption, CO₂ capture and delivery, labour, and solid-liquid separation.

The base-case input values were derived from regional market conditions (e.g., bulk industrial-grade prices in North America and Asia), experimental process data, and published cost estimates from prior techno-economic studies on mineral carbonation. For example, the CaO price was assumed to fall within $80–150 per tonne, representing raw industrial quicklime excluding modification or transport. In North America, electricity was modelled based on prevailing grid power rates, with a typical range of $ 0.08–0.12/kWh. The CO₂ capture and delivery cost, a major component of the system, was assumed to lie between $ 60–100 per tonne, in line with reported costs for point-source capture from flue gas or natural gas reforming83,84.

A Monte Carlo simulation was performed using @Risk (Palisade Corp.) in Excel to capture input uncertainty and evaluate system sensitivity. The model was run for 10,000 iterations. An appropriate probability distribution was assigned for each variable based on the following data extracted from the literature83,84,85,86:

-

CaO price: Triangular distribution (Min = $ 80, Mode = $ 110, Max = $ 150/t),

-

Electricity cost: Normal distribution (Mean = $ 0.10/kWh, SD = $ 0.02),

-

CO₂ delivery: Uniform distribution ($60–100/t),

-

Labour and separation: Uniform distribution ($ 8–15/t and $ 10–20/t, respectively),

-

Carbon credit value: Uniform ($ 0–50/t), included as a potential offset.

The simulation produced a range of CO₂ removal costs, represented by P10, P50 (median), and P90 percentiles. In our case, the median (P50) cost was ~$ 136/t CO₂ removed. These values reflect uncertainty across the input ranges and indicate how the total cost could vary under different scenarios. A sensitivity analysis was also performed, displaying the results as a tornado chart. The chart identifies the most influential cost drivers. The top three parameters affecting cost variability were CaO price, electricity rate, and CO₂ delivery. Solid-liquid separation and precipitation efficiency had moderate effects, while labour had a comparatively lower impact. Combining deterministic estimation with stochastic analysis offers a realistic framework for understanding economic uncertainty and targeting future cost-reduction efforts through material sourcing and process optimization.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting data and the findings of this study are available within the paper and the Supplementary Information. Source data are deposited to Figshare, and can be found and accessed at https://figshare.com/s/d0cc663370c515527b61.

References

Zhou, K., Zhang, J. & Xu, M. How to incentive carbon capture and storage technology application in waste-to-energy industry: a facility-level integrated assessment of China. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol.14, 100364 (2025).

Norouzpour, M., Santos, R. M. & Chiang, Y. W. Activation methods for enhancing CO2 mineralization via mine tailings—a critical review. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 15, 100430 (2025).

Liang, W. et al. Exergoeconomic analysis and machine learning-based optimization for a near-zero CO2 emission multi-generation system with freshwater production. Desalination 601, 118595 (2025).

Zhou, J. et al. Carbon allowance allocation and CO2 flows analysis in CCUS under the carbon market. J. Clean Prod. 473, 143566 (2024).

Wang, X. & Du, L. Study on carbon capture and storage (CCS) investment decision-making based on real options for China’s coal-fired power plants. J. Clean Prod. 112, 4123–4131 (2016).

Ho, D. T. & Bopp, L. Marine carbon dioxide removal may be a future climate solution. Dialogues Clim. Change 1, 56–62 (2024).

Lee, S. et al. CO2 Hydrate Composite for Ocean Carbon Sequestration. Environ Sci Technol 37, 3701–3708 (2003).

Mayor, D. J., Gentleman, W. C. & Anderson, T. R. Ocean carbon sequestration: particle fragmentation by copepods as a significant unrecognised factor?. BioEssays 42, 2000149 (2020).

Moras, C. A., Bach, L. T., Cyronak, T., Joannes-Boyau, R. & Schulz, K. G. Ocean alkalinity enhancement – avoiding runaway CaCO_3 precipitation during quick and hydrated lime dissolution. Biogeosciences 19, 3537–3557 (2022).

Hartmann, J. et al. Stability of alkalinity in ocean alkalinity enhancement (OAE) approaches – consequences for durability of CO_2 storage. Biogeosciences 20, 781–802 (2023).

Snæbjörnsdóttir, S. Ó. et al. CO2 storage potential of basaltic rocks in Iceland and the oceanic ridges. Energy Procedia 63, 4585–4600 (2014).

Goldthorpe, S. Potential for very deep ocean storage of Co2 without ocean acidification: a discussion paper. Energy Procedia 114, 5417–5429 (2017).

Feng, E. Y., Koeve, W., Keller, D. P. & Oschlies, A. Model-based assessment of the Co2 sequestration potential of coastal ocean alkalinization. Earths Future 5, 1252–1266 (2017).

Briggs, N., Dall’Olmo, G. & Claustre, H. Major role of particle fragmentation in regulating biological sequestration of CO2 by the oceans. Science (1979) 367, 791–793 (2020).

Fuhr, M. et al. Kinetics of olivine weathering in seawater: an experimental study. Front. Clim. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.831587 (2022).

Tagliabue, A. et al. Ocean iron fertilization may amplify climate change pressures on marine animal biomass for limited climate benefit. Glob. Chang. Biol. 29, 5250–5260 (2023).

Miao, L., Feng, L. & Ma, Y. Comprehensive evaluation of CCUS technology: a case study of China’s first million-tonne CCUS-EOR project. Environ. Impact Assess Rev. 110, 107684 (2025).

Menad, N. A., Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Varamesh, A. & Shamshirband, S. Predicting solubility of CO2 in brine by advanced machine learning systems: application to carbon capture and sequestration. J. CO2 Util. 33, 83–95 (2019).

Jacob, R. & Saylor, B. Z. CO2 solubility in multi-component brines containing NaCl, KCl, CaCl2 and MgCl2 at 297K and 1–14MPa. Chem. Geol. 424, 86–95 (2016).

Choi, W. Y., Aravena, C., Park, J., Kang, D. & Yoo, Y. Performance prediction and evaluation of CO2 utilization with conjoined electrolysis and carbonation using desalinated rejected seawater brine. Desalination 509, 115068 (2021).

Mohammadian, E. et al. Measurement of CO2 Solubility in NaCl brine solutions at different temperatures and pressures using the potentiometric titration method. J. Chem. Eng. Data 60, 2042–2049 (2015).

Zhao, Y. et al. Trash to treasure: Seawater pretreatment by CO2 mineral carbonation using brine pretreatment waste of soda ash plant as alkali source. Desalination 407, 85–92 (2017).

Li, W., Nan, Y., You, Q. & Jin, Z. CO2 solubility in brine in silica nanopores in relation to geological CO2 sequestration in tight formations: Effect of salinity and pH. Chemical Engineering Journal 411, 127626 (2021).

Mohammadian, E. et al. Probing Solubility and pH of CO2 in aqueous solutions: implications for CO2 injection into oceans. J. CO2 Util. 71, 102463 (2023).

Chalk, T. B., Foster, G. L. & Wilson, P. A. Dynamic storage of glacial CO2 in the Atlantic Ocean revealed by boron [CO32−] and pH records. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 510, 1–11 (2019).

Meyssami, B., Balaban, M. O. & Teixeira, A. A. Prediction of pH in model systems pressurized with carbon dioxide. Biotechnol. Prog 8, 149–154 (1992).

Plummer, L. N. & Busenberg, E. The solubilities of calcite, aragonite and vaterite in CO2-H2O solutions between 0 and 90 °C, and an evaluation of the aqueous model for the system CaCO3-CO2-H2O. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 46, 1011–1040 (1982).

Baghban, A., Sasanipour, J. & Zhang, Z. A new chemical structure-based model to estimate solid compound solubility in supercritical CO2. J. CO2 Util. 26, 262–270 (2018).

Gilbert, K., Bennett, P. C., Wolfe, W., Zhang, T. & Romanak, K. D. CO2 solubility in aqueous solutions containing Na+, Ca2+, Cl−, SO42− and HCO3-: The effects of electrostricted water and ion hydration thermodynamics. Appl. Geochem. 67, 59–67 (2016).

Zacherl, L. & Baumann, T. Quantification of the effect of gas–water–equilibria on carbonate precipitation. Geothermal. Energy 11, 11 (2023).

Peng, C., Crawshaw, J. P., Maitland, G. C., Martin Trusler, J. P. & Vega-Maza, D. The pH of CO2-saturated water at temperatures between 308 K and 423 K at pressures up to 15MPa. J. Supercrit. Fluids 82, 129–137 (2013).

Truche, L. et al. Direct measurement of CO2 solubility and pH in NaCl hydrothermal solutions by combining in-situ potentiometry and Raman spectroscopy up to 280 °C and 150bar. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 177, 238–253 (2016).

Rosenqvist, J., Kilpatrick, A. D. & Yardley, B. W. D. Solubility of carbon dioxide in aqueous fluids and mineral suspensions at 294K and subcritical pressures. Appl. Geochem. 27, 1610–1614 (2012).

Haghi, R. K., Chapoy, A., Peirera, L. M. C., Yang, J. & Tohidi, B. pH of CO2 saturated water and CO2 saturated brines: experimental measurements and modelling. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 66, 190–203 (2017).

Lai, H. et al. Geochemistry, origin and accumulation of natural gas hydrates in the qiongdongnan basin, south china sea: implications from site GMGS5-W08. Mar. Pet. Geol. 123, 104774 (2021).

Buure, K., Kainiemi, L. & Levänen, J. Uncovering opinions on the unfamiliar: investigating the attitude atmosphere around CCUS through media discourses. J. Clean Prod. 447, 141558 (2024).

Fang, X., Zhan, B. & Poon, C. S. Enhancement of recycled aggregates and concrete by combined treatment of spraying Ca2+ rich wastewater and flow-through carbonation. Constr. Build Mater 277, 122202 (2021).

Gineika, A., Dambrauskas, T. & Baltakys, K. Synthesis and characterisation of wollastonite with aluminium and fluoride ions. Ceram Int. 47, 22900–22910 (2021).