Abstract

Most volcanic eruptions occur in high-relief terrains, however the impact of mountainous topography on lava emplacement is poorly constrained. Here we use analogue materials (syrup, glycerol) to investigate lava effusion where changes in channel width form constrictions, leading to fluid/lava backup. Backup magnitude positively correlates with high volumetric fluid/lava fluxes, high fluid/lava viscosities, and narrow constrictions. Viscosity modulates the impacts of slope: steep slopes produce the largest backups when viscosity is high ( ~ 50 Pa s), while shallow slopes produce the largest backups at low viscosities ( ~ 1.5 Pa s). Scaling experimental results to natural systems, we propose lava backup occurs due to three primary reasons: (i) obstacle-flow interaction, (ii) constriction-induced flux imbalance and (iii) choked flow caused by critical flow transition. Lavas inundating constrictive topographies are highly susceptible to backup, causing excess upstream lava inundation and prolonged downstream effusion, increasing the inundation area and extending the time that communities are at risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The majority of volcanic eruptions feature an effusive component—the outpouring, emission, or extrusion of lava1,2. As they propagate downslope, these lavas pose a significant risk to populations and infrastructure3,4,5. As such, predicting the lava flow paths and associated lava inundation depths is critical for community and government planning6,7. Impacts of recent lava effusion include: destroyed or damaged structures (e.g., 2021 La Palma8, 2023–2024 Grindavik9); destroyed or damaged transport, communication, and utility infrastructure (e.g., 2018 Kīlauea10); destruction of agricultural land and natural habitats (e.g., 2015–2016 Fogo11; 2002–2003 Etna12); fires and explosions from lava-fuel interactions (e.g., 2002 Nyiragongo13); and phreatomagmatic events and damming or rerouting of fluvial systems (e.g., 2014–2015 Holuhraun14,15,; 1783–1784 Laki16).

In light of these social, economic, and human safety implications, it is imperative to be able to predict and understand where lava will flow. Conceptual, analogue, and numerical models have made significant advances in understanding the time scales, distributions, and consequences of lava inundation: substantive work has gone into understanding the flow of lava on unconfined slopes, where lava flow paths are largely dictated by topography, and lavas propagate toward and follow or pond in topographic lows17,18,19. This has been investigated using field observations20,21,22,23, laboratory experimentation24,25,26,27,28,29,30 and numerical modelling18,31,32,33. For comprehensive reviews of lava flow modelling, the reader is referred to the work of Tarquini et al.31 and Favalli et al.34.

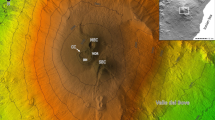

Approximately 12% of the Earth’s surface is covered in mountainous terrain35 defined as areas of high mean elevation and high topographic ruggedness where the maximal elevation difference between the neighbouring cells (250 m2 in size) in a digital elevation model exceeds a variably defined threshold (i.e., ~200–500 m)36,37,38. The most recent global mountain inventories39 show that over 75% of all Holocene volcanic activity has occurred within regions that classify as mountainous terrain. This clear spatial overlap is shown in Fig. 1 and illustrates the global co-existence of volcanoes and mountainous terrain; they are not limited to a single tectonic setting, volcanic landform, or magma type. In such environments, population centres, key transport corridors, and infrastructure commonly occupy valley floors40, where the risk of hazards posed by lava inundation is greatest. Mountainous terrains feature complex drainage patterns, including highly variable valley widths resulting from a range of processes. Changes in slope, river bedload supply, rock strength, structure, and lithology can impact valley widths41,42. Erosion can create landslides and alluvial fans, which impact the shapes of valley floors, creating scenarios where the relatively wide upstream valleys transition abruptly to anomalously narrow downstream valleys43. These topographic complexities (i.e., sharp transitions in valley widths), pose an additional, unaddressed challenge for forecasting lava flow behaviour44.

Holocene volcanoes are represented by triangles, while mountainous terrain is shaded in grey. 78% of all Holocene volcanoes are found within mountainous terrain (orange and red triangles); of that, 56% (red triangles) are located within high mountain terrain. Geospatial mountain data sourced from the K3 Global Mountains resource39, based on the four mountain classes in the 250 m global Hammond Landforms data layer. Holocene volcanic data is sourced from the Volcanoes of the World Database distributed by Smithsonian Institution89. Multidirectional hillshade sourced from Airbus, USGS, NGA, NASA, CGIAR, NLS, OS, NMA, Geodatastyrelsen, GSA, GSI, and the GIS User Community.

Topographic confinement of lava through valley constriction has been observed during the historical eruption of lava flows in Hawai’i (e.g., July and December 1974 Kīlauea20,45,46) and Iceland (e.g., 2021–2022 Fagradaslfjall47). In both instances dynamic ponding behind constrictions or lava inundation through valley ‘fill and spill’ was observed. Furthermore, valley constriction is documented in multiple studies of solidified Holocene and Pleistocene lavas. These include lavas in Argentina (Pampas Onduladas lavas48,49), Australia (Barambah basalt flow and Deep Creek flow field50), France (Tiretaine lavas51), Saudi Arabia (Harrat Rahat lavas52), and Canada (Cheakamus basalts53). The flow of lava through constrictive topography thus represents a key knowledge gap in our understanding of lava effusion and propagation dynamics44,51.

Here, we present a set of scaled analogue experiments that explore the consequences of channel width constrictions on the dynamics of downslope lava propagation. The experiments use analogue fluids, having a range of viscosity and density, flowing down a ramp with various slopes before entering constrictions of fixed width (Fig. 2, Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). These experiments and our associated analysis establish the specific conditions under which lava backup and excess inundation occur and relate the magnitude of backup to intrinsic (e.g., fluid properties) and extrinsic (e.g., slope and channel width) parameters. These insights provide a basis for recognising and mitigating the potential hazards and risks posed by effusive eruptions in mountainous terrains worldwide.

A hose measuring 2.5 cm in diameter (1 and 2) connects to a pump (not drawn). The hose was first placed above a measuring jug (position 1) into which fluid is pumped. The balance recorded the mass fluid within the jug at 1 s intervals, and using a known density, was used to calculate the flux of the fluid entering the channel (Qi). The hose was then attached to the experimental tank (position 2) for the experiment. The slope angle (β) was adjusted between 5, 10, 20, and 45 degrees. Additional plexiglass inserts were clamped inside the channel, reducing the channel width to 9, 7, 5, and 1 cm, respectively. At the down-slope end of the tank, a jug positioned on top a balance collects the outflowing fluid, and the outgoing flux (Qo) was calculated. Two cameras (A and B) capture video footage of the entire length of the experimental tank. The cameras were positioned at 90 degrees to the plexiglass wall of the tank, including the experiment timer and LED lights used for syncing imagery between cameras.

Results

Density and viscosity of the experimental fluids

Three experimental fluids were used: 100% Lyles’ brand golden syrup, 98% golden syrup diluted with 2 wt% water, and 100% vegetable glycerol. The fluids were chosen to scale to the general viscosities and densities of naturally occurring lavas capable of travelling far distances (i.e., high-temperature basalts to andesites) and have previously been used extensively in analogue flow models29,30,54. On the basis of the following viscosity and density results and characteristic thicknesses, timescale and densities of naturally occurring lavas, our experimental fluids scale to naturally occurring lavas55 with viscosities ranging from 104 to 107 Pa s.

The density of all fluids between 10 and 40 °C shows a linear relationship with temperature and can be described by

The values of constants A and B are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Between 10 and 40 °C the density of 100% golden syrup (100GS) ranges between 1440.8 and 1422.6 kg m−3. Reused 100% golden syrup (100GS-B) has a comparable range (1440.6 to 1422.3 kg m−3). Golden syrup diluted with 2 wt% water (98GS) is less dense and ranges from 1427.9 to 1409.9 kg m−3 over the 10 to 40 °C temperature range. 100% glycerol (100GLY) has the lowest density of all the fluids used in this study and, again, between 10 and 40 °C, ranges from 1267.1 to 1248.5 kg m−3 (Fig. 3a).

a The density of all experimental fluids as a function of temperature. Dashed lines are empirical fits following Equation 1. Note that the 100GS (light pink) and the 100GS-B datasets overlap. In both panels, error bars represent 1 standard deviation, and when not visible, they are smaller than the data point symbol. b The Newtonian viscosity of all experimental fluids as a function of temperature. Dashed lines are empirical fits following Eq. 2.

The viscosity of the experimental fluids varies as a function of temperature following

Specific values of the constants C and D for the temperature range (12.5 to 25 °C) are listed in Supplementary Table 2. For 100GS, the viscosity ranged from 136.8 to 22.2 Pa s (Fig. 3b). For 100GS-B, the viscosity ranged from 162.3 to 24.9 Pa s. Golden syrup diluted with water (98GS) is less viscous (52.1 to 12.5 Pa s), and 100GLY had the lowest viscosities of all fluids used and ranged from 3.0 to 0.9 Pa s (Fig. 3b).

Experimental and theoretical velocity and thickness of fluid flows

To evaluate our experimental approach against known theory, we compared measured velocities (vm) and thicknesses (xm) upslope of any constriction to theoretical values (vj, xj) determined using the Jeffreys’ equation56:

where \(\beta\) is the slope angle (in degrees), \(g\) is acceleration due to gravity and \(\mu\) is the fluid viscosity (in Pa s). To calculate the flow velocity vj, we substituted the measured flow thickness xm into Eq. (3). To calculate a theoretical thickness, xj we rearranged Eq. (3) and used the measured velocity vm as the flow velocity. We calculated maximum and minimum values using the range of densities and viscosities based on the measured fluid temperatures; these ranges are plotted as error bars on Fig. 4. Most velocities (Fig. 4a) and all thicknesses (Fig. 4b), plot within 10% of a 1:1 line. This informs us that, before the influence of any channel constriction, our experimental set-up, fluids, and data acquisition strategy follow the Jeffery’s relationship. As such, or experiments provide a robust means of quantitatively capturing the downslope propagation of viscous fluids.

Theoretical values are calculated using the Jeffreys’ equation (Eq. 3); theoretical (a) velocities and (b) thicknesses are calculated using viscosity (μ) and density (ρ) values for the mean temperature of each experiment. Mean measured thicknesses (xm) are used to calculate theoretical velocities (vj) and mean measured velocities (vm) are used to calculate theoretical thicknesses (xj). Solid line indicates a 1:1 match between measured and theoretical values; dashed lines indicate a 10% deviation. Horizontal error bars represent the range of measured velocity or thickness during the experiment. Vertical error bars represent the range of theoretical velocities or thicknesses, controlled by the maximum and minimum temperatures (and therefore maximum and minimum ρ and μ of each experiment).

Flow back-up development over time

For experiments with channel constrictions, we plotted (i) the thickness of fluid backup (xc) over time (Fig. 5a–c) and (ii) volume behind constriction (Vc) over time (Fig. 5d–f). The experiments show a power-law relationship between backup thickness (xc) and time (Fig. 5a–c). For all fluids, the backup thickness shows an initial rapid increase before gradually approaching a ‘plateau’ value of maximum excess thickness.

The excess flow thickness behind the constriction for (a) 100GS and 100GSB, b 98GS and c 100GLY, as a function of time since reaching the constriction, tc. In all cases, the backup thickness (xc) initially increases rapidly and then approaches a plateau value. The largest excess xc occurs in experiments with narrower constrictions (high R values) and higher flux (Qi) controlled by high pump speeds and steeper slopes. Also plotted is the excess flow volume (Vc) behind the constriction for (d) 100GS and 100GSB, (e) 98GS, and (f) 100GLY, as a function of time since reaching the constriction, tc. The largest excess Vc occurs in experiments with the highest R values.

We interpret this plateau in xc as a ‘steady state’ condition between the flow approaching the constriction and the flow within the constriction. Most experiments approached or achieved a ‘steady state’ as indicated when: (i) thickness of fluid behind the constriction ceases to increase (cf. plateaus in Fig. 5a–c), (ii) volume of fluid behind the constriction ceases to increase, (cf. plateaus in Fig. 5d–f), and (iii) a balance of fluxes is achieved where the influx from the pump (Qi) matches the outflow (Qo) from the constricted channel. A list of experiments which achieved steady state can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Of the 54 experiments performed, 77% reached steady state, ~12% of experiments reached an approximate steady state, and 11% did not reach steady state. We contend that all experiments can achieve steady state given sufficient time and space, and that those that did not were impacted by physical experimental constraints. For example, all experiments that did not achieve steady state were those with the narrowest constrictions (i.e. 1 cm). Within these highly constricted experiments, some long duration or high flux experiments did not reach steady state because the fluid backup threatened to overtop the tank walls, the backup inundated the hose input location and the upstream limit of the tank, or the upstream fluid reservoir was exhausted.

Experiments with higher viscosity fluids (100GS/100GS-B) took longer to achieve steady state and achieved higher maximum xc compared to low viscosity fluids (e.g. 100GLY). Experiments with narrower constrictions achieved higher maximum xc and took longer to reach steady state. Experiments with a faster fluid supply to the constriction (controlled by greater Qi and/or β) showed a more rapid initial growth rate of xc and achieved higher maximum xc than comparable experiments with a lower supply rate. For experiments with a high rate of fluid supply (high Qi and high β), decreasing the constriction width resulted in a more pronounced impact on maximum xc compared to experiments with relatively slow supply. Reducing the constriction width from 5 cm to 1 cm resulted in a far greater change in maximum xc than reducing the width from 9 cm to 5 cm, thus, the impact of narrowing the constriction was not linear.

Impact of constriction width on flow back-up magnitude

We have compared the measured backup thicknesses to a dimensionless channel width, R, defined as

where w1 and w2 are the channel widths before, and within the constriction, respectively. Thus, greater R values are indicative of greater channel width constrictions. For all fluids, slope angles, and Qi values, the larger the R value (i.e. the narrower the constriction), the greater the backup upstream of the constriction (Figs. 6 and 7). We also find that higher viscosity fluids cause higher backups (Fig. 7). For example, at R = 10, a ~50-fold increase in viscosity between 100GLY and 100GS/100GS-B (~1 Pa s versus ~50 Pa s at experimental temperatures) resulted in a 5-fold increase in backup thickness. Additionally, all other parameters being equal, experiments with larger Qi values resulted in higher backups. For example, equivalent experiments but at faster pump speeds (120 rpm vs 10 rpm) resulted in at least a 3-fold increase in backup volumes and thicknesses across all fluids. Lastly, we observed that the larger the R value, the greater the effect of viscosity and Qi on modulating backup.

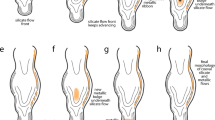

This is shown for a 100% glycerol, b 98% golden syrup with 2% water, and c 100% golden syrup. Higher viscosity fluids result in thicker backups. For all fluids, slopes, and Qi, larger R values result in greater backup thicknesses (xc). The effect of slope is modulated by viscosity; at high viscosity (100GS/100GS-B, ~50 Pa s, c the steepest slopes result in the thickest backup, while at low viscosities (100GLY, ~1.5 Pa s), a the inverse relationship is observed. Intermediate viscosities (98GS, ~15 Pa s, b show largest backups at 20°, 45°, and 10° sequentially. Slashed symbols indicate the experiment did not achieve steady state; thicknesses for these experiments are significantly smaller than thicknesses expected at steady state. Symbols with small arrows indicate the experiment achieved approximate steady state.

The effect of slope on backup thickness varies between the different experimental fluids (Fig. 7). At high viscosities (i.e., the 100GS and 100GS-B fluids at ~ 50 Pa s), all else being equal, steeper slopes result in the greatest backup (Fig. 6c). At low viscosities (100GLY at ~1.5 Pa s), the inverse relationship is observed, where shallower channel slopes lead to greater backup (Fig. 6a). At intermediate viscosities (98GS at ~15 Pa s), experiments at 20° slopes result in the greatest backups, 45° slopes with the second greatest, and 10° slopes with the lowest backups (Fig. 6b).

Discussion

Conceptually, fluid/lava back-up can result from at least three mechanisms: (i) backup behind an obstruction; (ii) backup generated to achieve a balance in volumetric flux; or (iii) backup caused by choked flow. These three different mechanisms are now explored and evaluated with respect to natural lava effusion.

The backup of lava upstream of obstacles is commonly observed during active lava effusion57. For example, lava tree moulds are indicative of a small-scale backup where lava is thicker on the upstream side of the tree58,59,60; this thickening is ascribed to the formation of a bow wave around the obstacle61. Bow waves have also been observed to form at barriers constructed to divert lavas from infrastructure62,63. In many cases, the excess build-up of lava is high enough to overtop barriers, complicating or undermining attempts at hazard mitigation17. Bow waves forming upstream of obstacles have also been demonstrated experimentally for both sugar syrup and molten basalt flowing down a slope29. Higher velocities (controlled by flux or by slope angle) and higher angles of incidence between the flow and the obstacle result in larger bow waves, and thus locally, greater excess lava inundation.

In general, when a viscous fluid such as lava meets an obstacle, flow is diverted around the obstacle along a path that has a shallower effective slope, thereby decreasing the local flow velocity. However, the velocity remains unaffected upstream, resulting in excess inundation around the obstacle. In addition, lava quenches and cools against obstacles, and the resulting change in fluid properties can also locally thicken the flow.

In our experiments, the constriction itself acts as an obstacle to flow. The upstream-facing walls of the constriction are orthogonal to the flow direction, and as such have an incidence angle of 90°. As the flow diverts around this obstacle (into the narrower width portion of the channel), it travels down an effective slope of 0°. The flow slows dramatically, and its advance is driven solely by gravitational collapse of the fluid28. Greater constrictions (i.e. higher R values) exacerbate this effect, as the flow must traverse a farther distance before reaching the constriction opening and continuing to flow downslope. This effect is also greater for higher viscosity fluids, as a higher internal fluid friction more effectively resists gravitational collapse and results in a longer timescale for drainage and flow around the obstacle. In nature, valley wall constrictions will take a variety of forms, and unlike the experiments will not always be 90° to flow. We expect that backup generated by valley constrictions acting as obstacles will be reduced for the following cases: (i) for lower viscosity lavas; (ii) for constrictions where traversal distances across a shallower effective slope are short (i.e. wider constrictions/small R values); (iii) for constrictions with low angles of incidence relative to the direction of flow.

Many of our experiments approach steady state defined by an equality of volumetric fluxes entering and exiting the experimental apparatus, sometimes described as dynamic ponding45. This implies that

where Qi is the flux approaching the constriction, and Qo is the flux within the constriction (Fig. 2). This can be expressed in terms of the fluid velocity and channel geometry as:

where the subscript 1 indicates measurements within the main upstream channel and 2 indicates within the constricted channel. To conserve the flux in Eq. (5), when w2 < w1 a change in flow thickness and/or velocity is required in the constricted channel as per Eq. (6). We compare our experimental data, including measured thicknesses and velocities within the constriction, to the values required for steady-state behaviour and the conservation of flux (i.e., \({Q}_{i}={Q}_{o}\)). For a given Qi and constriction width (w2), we calculate a model thickness (xpc) from the measured constriction velocity (vmc), and similarly, we calculate a model velocity (vpc) from the measured thickness (xmc).

Experiments with significant deviations between modelled and measured thicknesses (xpc and xmc) are those that did not achieve steady state (Supplementary Fig. 1). All of these experiments are those where R = 10. In these outlying experiments, vmc and xmc are significantly higher than modelled values, indicating that, at the time of measurement, the fluid had not reached the critical thickness and/or velocity needed to meet the condition Qi = Qo.. Across the remainder of the experiments, which did reach a steady-state, there is good agreement (<10% difference) between the modelled and observed thickness and velocity values (Supplementary Fig. 1). This indicates that the flow conditions within the channel (i.e. thickness and velocity) are consistent with Qi = Qo..

In a constricted channel, the reservoir of excess volume behind the constriction, Vc, is a proxy for the time required for the system to establish an equality of fluxes. As the fluid thickness upstream of the constriction increases, the pressure head created by fluid backup increases until a critical thickness (xc) is reached, providing the pressure needed to increase the within-constriction flux to equal the approach flux. Vc is thus a geometric consequence of xc and is strongly modulated by the substrate slope. Steep slopes require less volume to achieve a given xc compared to shallow slopes. As an extreme end-member example (e.g., at very low slopes), the volume required to reach a given xc approaches infinity. Thus, slope modulates the volume/time required to achieve a threshold pressure head needed to obtain Qi = Qo..

Our experimental data show that the smallest backup volumes (Vc’s) are associated with low viscosity fluids, low R values, and steep slopes (Fig. 7). For example, at constant slope and R, lower viscosity fluids (100GLY) achieve the smallest Vc and xc, whilst high viscosity fluids (100GS/100GS-B) have the largest. At constant viscosity, Qi and R, the backup volume Vc systematically decreases for an increase in slope (Fig. 5). The 100GS/100GS-B experiments are an apparent exception to this trend; the 100GS experiment at 20° achieved greater Vc than comparable experiments at 10°, although neither experiment reached steady-state. Extrapolating the power function of both experiments in Fig. 5 indicates 10° would produce a greater volume back-up at equilibrium conditions, thereby agreeing with the aforementioned trend.

This relationship between R, viscosity, and slope has implications for eruptions of lava, where timescale and reservoir volume affect cooling rate and, consequently, flow behaviour. In an eruption scenario where lava flows down a valley and meets a topographic constriction (Fig. 8), the area downstream of the constriction will eventually experience the same eruptive flux as observed at the vent. However, there will be a time-lag dictated by slope, viscosity, and R value, with the backup reservoir acting as a ‘buffer’ between the vent flux and the downstream flux. If the valley has low slope angles (e.g. 1–10°), the time-lag will be protracted and backup will be more voluminous and will be felt further upstream, where it may inundate valley slopes and tributary valleys that would otherwise remain unimpacted by lava flows (Fig. 8). The phenomenon of upstream lava flow advancement into tributary valleys has been documented upstream of constrictions in channel-confined lavas in the Grand Canyon, USA, Coulstone Lakes Volcanic Field in Australia, and in the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, in Canada50,53,64. These locations constitute natural examples of lava backup and additional inundation upstream. A further consequence is that the backup behind the constriction can result in an insulated reservoir of lava, retarding cooling, prolonging the time period in which lava flows are active and potentially increasing the distance that lava reaches downslope45,48.

A viscosity threshold for obstacle vs flux imbalance-induced backup

In our experiments, we have provided evidence for backup occurring due to (i) flow impedance due to obstacles and (ii) increases in flow thickness required to achieve a balance between the upstream and downstream volumetric flux (i.e. ‘dynamic ponding’). In all our experiments, both processes operate. However, their relative impact varies depending on the fluid viscosity. This control is illustrated in the relationships presented in Fig. 6. For the 100GLY experiments with a viscosity of ~1.5 Pa s, greater R values and shallower slopes generate greater backup thicknesses (xc). The viscosity of glycerol is low enough such that the inertial fluid friction does not significantly supress the increase in fluid flow velocity within the constriction following the Bernoulli principle to achieve \({Q}_{i}={Q}_{o}\). Thus, flow impedance due to the constriction acting as an obstacle dominates and is primarily responsible for backup.

In contrast, the 100GS/100GS-B experiments, with a viscosity of ~50 Pa s, show an opposite relationship between xc, R, and slope (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Fig. 1). For example, when R = 10, steeper slopes correspond to a higher xc. In these experiments, high viscosities prevent the fluid from attaining the velocity required within the constriction to support a flux balance (i.e. Qi = Qo). To achieve such a flux balance between Qi and Qo, the velocity within the constriction is increased. Velocity increase occurs by flow thickening immediately upstream of the constriction, providing a greater pressure head that drives flow and thus increases the velocity within the constriction. As fluid velocities increase with steepness of slope, the effect is amplified at high slope angles. Although the effects of an obstacle are still present, we contend that for the 100GS/100GS-B experiments, the effects of a velocity, and thus flux imbalance within the channel, dominate. The intermediate fluid (98GS) with viscosity of ~15 Pa s produces the highest xc values at substrate slopes of 20°, capturing a transition between these two regimes.

Based on the parameter space investigated here, we suggest that a viscosity of ~101 Pa s for natural lavas represents a division between backup primarily driven by: (i) obstacles impeding flow (<101 Pa s) vs. (ii) increased lava thickness required by a volumetric flux balance ( > 101 Pa s). Naturally occurring lavas with viscosities <101 Pa s are relatively rare and generally comprise ultramafic lavas and carbonatites65,66. Basalt lavas at eruption temperatures commonly have viscosities of 102–103 Pa s and increase to ~105–106 Pa s as they cool and crystallise. Intermediate to silicic lavas erupt with viscosities67 >106 Pa s. On that basis, we suggest that constriction induced backup of naturally occurring lavas is mainly driven by a flux imbalance within the channel (i.e. the second mechanism).

A third possible mechanism for generating lava backup is by choked flow. Transitions in flow behaviour are commonly encapsulated by the dimensionless Froude number, defined as

where

Fr therefore represents the ratio of inertial forces to gravitational forces acting on a fluid, and when balanced, at Fr = 1, the flow is in a critical state. At Fr < 1 the flow can be described as subcritical, and supercritical for Fr > 1. In volcanology, this analysis is typically used in the context of hydraulic jumps wherein channelised lavas abruptly transition from supercritical to subcritical flow conditions, commonly triggered by a change in the channel slope. A hydraulic jump occurs because the channel cannot sustain supercritical flow; in response, the flow changes depth (h) in order to stabilise flow in a subcritical state. Vent proximal, high-temperature basaltic lavas with low Newtonian viscosities68 (10–1000 Pa s) can achieve Fr > 1 due to high velocities (~10 m s−1) and thicknesses (>1 m). Standing waves are one manifestation of supercritical flow that have been described in active lava channels with high velocities and breaks in slope near eruptive vents20,69,70,71.

Changes in flow conditions can also occur due to a reduction in channel width. As a channel narrows, the flux per unit width, q (i.e., q = Q/w), increases, which can be supported up to a limiting flux per unit width, qmax, corresponding to Fr = 1. However, if qmax is exceeded, then the flow becomes choked and the upstream flow depth needs to increase (i.e., backup occurs) to provide the additional energy required72. In these cases, critical conditions (i.e. Fr = 1) are maintained within the constriction itself.

For our analogue experiments we compare flow velocities and thicknesses to the critical condition Fr = 1. We find that all experimental fluids were in a subcritical flow state in both the approach and constricted portions of the channel (Fig. 9a). Reaching critical flow conditions for our given experimental parameters requires an increase in velocity, and therefore flux, of more than an order of magnitude. Thus, fluid backup observed in our experiments cannot be attributed to a thickness increase resulting from choked flow. However, channel constrictions can induce choked flow conditions in natural lavas. One instance of constricted flow is the July 1974 Kīlauea eruption, which transitioned from an unconfined flow field (~300 m wide) to a constricted channel when lava entered a preexisting gully feature (5–10 m wide)20. For lava with comparable flux and thickness to those observed during the 1974 eruption, Fig. 9b indicates how decreasing channel width from 300 m to 5–10 m can meet and exceed Fr = 1, thus leading to upstream lava backup.

a Fluid thickness vs channel width for our analogue experiments. Blue box indicates the range of fluid thicknesses and channel widths of our experiments. The solid line indicates Fr = 1 at the maximum volumetric flux recorded (1.2 × 10−5 m3 s−1) at 0° (lower bound) and 45° (upper bound) channel slopes. All our experiments fall within the subcritical flow domain. Hypothetical data point A displays a flow in subcritical flow conditions. Sufficiently decreasing channel width (dashed blue arrow) will bring A into a critical state. b Volumetric flux vs flow thickness for a natural example22 of constricted flow that displayed supercritical flow features (July Kīlauea eruption, 1974). Solid lines indicate Fr = 1 at unconstrained channel width (~300 m) and constricted widths (5 and 10 m) at 0° (lower bound) and 45° (upper bound) channel slopes. Blue box indicates range of estimated volumetric flux and flow thickness for the eruption. Hypothetical data point B is subcritical at unconfined, 300 m channel widths, but achieves critical conditions when channel is sufficiently constricted (dashed grey arrow).

Across all basaltic lavas we expect that channel constrictions can induce critical conditions. For typical volumetric fluxes (10−1 to 103 m3 s−1) and flow thicknesses (1 to 10 m), it is apparent that many channel widths on the order \(\lesssim\) 10’s m can push the system into a critical state (Fig. 9b). When achieved, choked flow and backup will occur, causing excess inundation upstream. These conditions are heavily reliant on low viscosities and high volumetric fluxes. We would expect critical flow conditions to occur proximal to eruptive vents, where lava temperatures are high, and crystallinity, and therefore viscosities, are often lowest. Additionally, as (super)critical flow requires extreme narrowing in channel widths (<10 m), we would expect this phenomenon to occur at specific, limited topographic and eruptive conditions.

All fluids used in this study were found to be Newtonian. Lavas in nature can exhibit non-Newtonian properties, including thixotrophy and viscoplasticity, depending on vesicle content, crystal concentrations, and temperature73,74,75,76,77. Furthermore, mechanical and thermal boundary layers develop during cooling that can cause differences in rheology within flows23,78. Analogue fluids used in these experiments represent a rheological end-member, relative to the natural fluids, most appropriate to lavas close to their liquidus temperatures (i.e. low crystallinity (<10%), low vesicularity)79,80,81. However, experiments using Newtonian fluids offer the advantage that, because the fluid properties are simple, the physical mechanisms controlling the results are more apparent, and cause and effect can be more definitively linked.

We contend that natural lavas met with constrictive conditions likely have non-Newtonian properties due to myriad processes (crystallisation, crust formation, etc.) which occur between eruption and solidification. Here, we speculate on the impact of non-Newtonian fluid characteristics on the phenomenon of flow backup due to constrictions in confining channels. Bingham fluids generally result in thicker flows in comparison to Newtonian fluids; the added effects of quenching and crust formation against obstacles result in local thickening as well29. Greater initial flow thicknesses may require less excess thickness backup in order to reach flux equilibrium, resulting in backups of lesser magnitude. In open channel flow, fluids with yield stresses form regions of stagnant flow (solid ‘plugs’) reflecting decreasing gradients in shear stress away from the channel wall82. Such plugs encourage and stabilise crust formation and thus rheological stratification, however, experiments on wax analogue models83 found that crust formation had little impact on fluid-obstacle interaction. Plugs in the corners of open channels cool, solidify, and eventually change the perimeter shape of the channel; this effect would likely also occur at the constriction, resulting in a change in constriction geometry (i.e. a shallower angle of incidence) over time and a lessening of related impacts on flow backup. Yield strength may also have an impact on the effects of pressure head. In our experiments, pressure head provided by overthickening of the flow allows the fluid entering the constricted channel to attain equal flux with the approaching flow. The initial efficacy of this pressure head may decrease for non-Newtonian fluids, as a yield strength will have to be overcome in order to initiate flow.

Conclusion

Our experiments indicate that, given sufficient time and a constant upstream flux, fluid flow in a constricted channel system will reach a steady-state where the flux within the constriction will equal the source flux. Minor fluid backup occurs upstream of the constriction due to the obstacle of the constriction walls, creating a ‘bow wave’ in the flow. Larger magnitude backup occurs during dynamic ponding as the flow changes velocity and thickness in order to maintain an equilibrium of fluxes. High internal flow resistance prevents high viscosity fluids (>101 Pa s) from attaining sufficient velocities required to achieve flux equilibrium. Flux equilibrium is instead eventually achieved by the additional pressure head provided by increased flow thickness. In our experiments, backup is not caused by choked flow conditions; however, given the correct conditions, could theoretically occur in natural eruptions.

In nature, constriction-related backup can pose additional eruption hazards in volcanically active valley systems (Fig. 8). The resulting reservoirs of lava inundate upstream areas, pose the risk of ephemeral vent opening due to obstruction collapse, and act as zones that modulate the effect of effusion rate on flow advance. These factors can increase the longevity and distance of lava flow fields and extend the area and time that communities are at risk. This phenomenon and its associated hazards are of high importance given the large spatial overlap between constrictive mountainous terrain and volcanic activity globally.

Methods

Measurement of fluid properties

We measured the liquid density (ρ) of all the analogue fluids using an Anton Paar DMA4101 density metre. An aliquot of fluid was loaded into the density metre and increased the temperature from 10 °C to 40 °C with a fluid density measurement taken every 2.5 °C. This process was repeated three times for each fluid and the reported values and associated error are the mean and standard deviation of the three measurements, respectively.

We also determined the dynamic viscosity (μ) of the analogue fluids with an Anton Paar ViscoQC 300 rotational viscometer equipped with Peltier temperature device that enabled the sample temperature to be set for each viscosity determination. For each measurement, approximately 0.5 ml of bubble-free fluid was loaded onto the base, temperature-controlled Peltier plate and an upper cone measuring geometry was lowered into the sample. For all golden syrups, a 3° cone measuring 24 mm in diameter was used and for the glycerol a 0.8° cone measuring 48 mm in diameter was used. The temperature of the Peltier plate was set and left to thermally equilibrate with the fluid. Following this, the measuring geometry was rotated to provide twenty different shear rates (i.e., a shear-rate sweep). Any erroneous data at the start (due to start-up flow) or end (due to viscous heating) of the shear-rate sweeps was discarded. For each fluid, this process was repeated for a series of temperatures between 12.5 °C and 25 °C, with 2.5 °C intervals. Then, for each temperature, the viscosity was calculated as the mean of all viscosity values measured during a shear-rate sweep, as the fluids used are known to be strictly Newtonian84,85,86. The standard deviation on the fluid viscosity measurements was also calculated for each shear-rate sweep.

Analogue experiments

Three fluids, each with a different viscosity, were used for our analogue experiments. These include: (i) 100% Lyle’s golden syrup (ii) 98 wt % Lyle’s golden syrup diluted with 2 wt % water and (iii) 100% vegetable glycerol dyed with 0.55 wt % food colouring (Wilton violet icing) to support visual observations and subsequent image analysis. The syrup was diluted by incrementally adding water while thoroughly mixing using an electric drill with a paddle attachment (a Daniatech MixMaster). The diluted syrup was left standing for 48 h, allowing any air bubbles generated by the mixing process to rise out. The dye was added to the glycerol using this same approach. Any fluids recycled between experiments were also left standing for a minimum of three hours to minimise the presence of air bubbles.

The channel used in our experiments is made from plexiglass and is 10 cm wide, 25 cm high, and 160 cm long (Fig. 2). The upper 100 cm of the channel has a fixed width (10 cm), while the width of the lower portion of the channel can be changed by adding a pair of rectangular plexiglass inserts which reduce the downstream width to 9, 7, 5, or 1 cm, respectively (Fig. 2). The channel slope is also adjustable and for these experiments was set at 5°, 10°, 20°, or 45°. The base of the channel (i.e., the analogue substrate) is lined with fine-grit sandpaper to avoid any basal slip. The fluid enters the upper part of the channel from a 2.5 cm diameter hose attached to a 2 cm wide inlet hole located in the middle of the channel tank base. The fluid is pumped and introduced into the channel using a high-viscosity cavity-style pump and in our experiments, two pump speeds of 10 rpm and 120 rpm were used. A list of all the experiments performed in this study is included in Table S1.

Immediately preceding each experiment, the fluid was pumped into a measuring jug, the fluid temperature measured, and the mass within the jug was recorded as a function of time. During this measurement, the pump hose was positioned at the same elevation as the channel/tank input. The volumetric flux of the fluid entering the measuring jug, Qi, was calculated by converting the fluid mass to volume using our density-temperature relationship described in the results section. Qi, therefore, represents the volumetric flux that enters the channel during the experiment.

The hose was then attached to the base of the channel and the pump was set to Qi. Two video cameras (Fig. 2) positioned ~ 1.5 m from the experimental channel tank, captured the entire experiment in their field of view (Fig. 2). Specifically, the two cameras were (A) Fujifilm X-T200 Mirrorless camera with a 15–45 mm lens and (B) an Olympus OM-D E-M10 Mark IV camera with a 14–42 mm lens. Both cameras recorded at 2160 × 3840 pixels resolution at 30 frames per second (Supplementary Video. 1). The pump remained on and the experiment continued until (a) the flow thickness reached a steady state or (b) the fluid reached the top of the experimental channel and could overspill. During the experiment, the fluid temperature was constantly measured at the fluid entry point/inlet and at the channel outflow. The outflowing fluid was collected in a measuring jug and the outgoing flux Qo was calculated using the same method used to calculate Qi.

Dynamic similarity

Our analogue experiments investigate the fundamental processes responsible for flow backup in channels that feature a width reduction (or constriction). Supplementary Table 3 lists the key parameters of our experiments and mafic lava flows and relevant dimensionless numbers. The dimensions covered by our experiments and natural mafic lava flows overlap, illustrating dynamic similarity (Supplementary Table 3). Thus, processes and relationships observed in our experiments are possible and likely to occur in the natural system55,87,88.

Image analysis methods

For all experiments, quantitative data were extracted using the image analysis software ImageJ. Images of a ruler were used as a scale to convert distances from pixels to m. Images from the two cameras were synced using a physical timer placed within the field of view of both cameras. Further checks using manually controlled LED lights that were switched on at key moments (e.g. initiation of flow into channel) also ensured that the cameras were synced. To measure the fluid velocity, videos from the experiments were imported as stacks of images captured at 3 fps (golden syrup at low Qi), 5 fps (golden syrup at high Qi), and 10 fps (dyed glycerol). The channel was divided into twenty distance intervals of equal length (Supplementary Fig. 2a). For experiments with high fluid velocities (i.e. high slope angle and low viscosity), we further divided the channel into 30 intervals. The time taken for the fluid flow front to travel from d1 to d2, d2 to d3, and so forth, was recorded and the mean measured velocity, vm, was calculated. The same method was used to calculate the velocity of the flow front within the constriction, vcm, but using ten distance intervals due to its shorter length.

The flow thickness (xm) was measured perpendicular to the channel base, and was measured when the flow front reached each distance interval (i.e. dn). We also measured thickness at two to three intervals behind the flow front to check that the flow thickness was uniform. The series of thicknesses was then averaged to produce a mean fluid flow thickness for the experiment, xm. Additional measurements were taken for the experiments that used a constriction. The thickness of fluid back-up behind the constriction (xc) was measured over time (Supplementary Fig. 2b) and the cross-sectional area of the fluid back-up (Supplementary Fig. 2c) was concurrently measured using the same time intervals and multiplied by the experimental channel width (10 cm) to calculate the fluid volume behind the constriction. A similar method was used to measure the thickness of fluid within the constriction (xcm); however, measurements were taken at three distinct moments of time after steady state had been reached and subsequently averaged.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and Supplementary Materials.

References

Cassidy, M., Manga, M., Cashman, K. & Bachmann, O. Controls on explosive-effusive volcanic eruption styles. Nat. Commun. 9, 2839 (2018).

Delgado Granados, H., Dingwell, D. B. & Hidalgo, S. Editorial: volcanoes’ change of mood and their impact: effusive—explosive eruptions and vice versa. Front. Earth Sci. 12, 1485511 (2024).

Sparks, R. S., Aspinall, W. P., Crosweller, H. S. & Hincks, T. K. Risk and uncertainty assessment of volcanic hazards. in Risk and Uncertainty Assessment for Natural Hazards vol. 1 364–397 (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Brown, S. K. et al. Global volcanic hazard and risk. in Global Volcanic Hazards and Risk 81–172 (Cambridge University Press, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316276273.004.

Tsang, S. W. R. & Lindsay, J. M. Lava flow crises in inhabited areas part I: Lessons learned and research gaps related to effusive, basaltic eruptions. J. Appl. Volcanol. 9, 1–26 (2020).

Negro, C. Del et al. Lava flow hazards at Mount Etna: constraints imposed by eruptive history and numerical simulations. Sci. Rep. 3, 3493 (2013).

Houghton, B. F. et al. The birth of a Hawaiian fissure eruption. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2020JB020903 (2021).

Carracedo, J. C. et al. The 2021 eruption of the Cumbre Vieja volcanic ridge on La Palma, Canary Islands. Geol. Today 38, 94–107 (2022).

Parks, M. et al. 2023–2024 inflation-deflation cycles at Svartsengi and repeated dike injections and eruptions at the Sundhnúkur crater row, Reykjanes Peninsula, Iceland. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 658, 119324 (2025).

Meredith, E. S. et al. Damage assessment for the 2018 lower East Rift Zone lava flows of Kīlauea volcano, Hawaiʻi. Bull Volcanol. 84, 65 (2022).

Jenkins, S. F., Day, S. J., Faria, B. V. E. & Fonseca, J. F. B. D. Damage from lava flows: insights from the 2014–2015 eruption of Fogo, Cape Verde. J. Appl. Volcanol. 6, 6 (2017).

Harris, A. et al. Forest destruction by’a’ā lava flow during Etna’s 2002-03 eruption: mechanical, thermal, and environmental interactions. J. Volcanol. Geothermal Res. 429, (2022).

Tedesco, D. et al. January 2002 volcano-tectonic eruption of Nyiragongo volcano, Democratic Republic of Congo. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 112, 1–12 (2007).

Pedersen, G. B. M. et al. Lava field evolution and emplacement dynamics of the 2014–2015 basaltic fissure eruption at Holuhraun, Iceland. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 340, 155–169 (2017).

Dundas, C. M. et al. Lava–water interaction and hydrothermal activity within the 2014–2015 Holuhraun Lava Flow Field, Iceland. J. Volcanol. Geothermal Res. 408, 107100 (2020).

Boreham, F., Cashman, K. & Rust, A. Hazards from lava–river interactions during the 1783–1784 Laki fissure eruption. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 132, 2651–2668 (2020).

Dietterich, H. R. & Cashman, K. V. Channel networks within lava flows: Formation, evolution, and implications for flow behavior. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 119, 1704–1724 (2014).

Bilotta, G., Cappello, A., Hérault, A. & Del Negro, C. Influence of topographic data uncertainties and model resolution on the numerical simulation of lava flows. Environ. Model. Softw. 112, 1–15 (2019).

Jones, T. J., Llewellin, E. W., Houghton, B. F., Brown, R. J. & Vye-Brown, C. Proximal lava drainage controls on basaltic fissure eruption dynamics. Bull. Volcano. 79, 1–15 (2017).

Heslop, S. E., Wilson, L., Pinkerton, H. & Head III, J. W. Dynamics of a confined lava flow on Kilauea volcano, Hawaii. Bull. Volcano. 51, 415–432 (1989).

Solana, M. C. Development of unconfined historic lava flow fields in Tenerife: Implications for the mitigation of risk from a future eruption. Bull. Volcano. 74, 2397–2413 (2012).

Hamilton, C. W., Glaze, L. S., James, M. R. & Baloga, S. M. Topographic and stochastic influences on pāhoehoe lava lobe emplacement. Bull. Volcano. 75, 1–16 (2013).

Lev, E., Spiegelman, M., Wysocki, R. J. & Karson, J. A. Investigating lava flow rheology using video analysis and numerical flow models. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 247–248, 62–73 (2012).

Fink, J. H. & Griffiths, R. W. Radial spreading of viscous-gravity currents with solidifying crust. J. Fluid Mech. 221, 485–509 (1990).

Blake, S. & Bruno, B. C. Modelling the emplacement of compound lava fows. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 184, 181–197 (2000).

Sakimoto, S. E. H. & Gregg, T. K. P. Channeled flow: analytic solutions, laboratory experiments, and applications to lava flows. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 106, 8629–8644 (2001).

Balmforth, N. J., Craster, R. V., Rust, A. C. & Sassi, R. Viscoplastic flow over an inclined surface. J. Nonnewton Fluid Mech. 139, 103–127 (2006).

Kerr, R. C., Griffiths, R. W. & Cashman, K. V. Formation of channelized lava flows on an unconfined slope. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 111, B10 (2006).

Dietterich, H. R., Cashman, K. V., Rust, A. C. & Lev, E. Diverting lava flows in the lab. Nat. Geosci. 8, 494–496 (2015).

Rumpf, M. E., Lev, E. & Wysocki, R. The influence of topographic roughness on lava flow emplacement. Bull Volcanol. 80, 63 (2018).

Tarquini, S. et al. Modeling lava flow propagation over a flat landscape by using MRLAVALOBA: The case of the 2014-2015 eruption at Holuhraun. Iceland 62, 228 (2019).

Saville, J. M., Hinton, E. M. & Huppert, H. E. Predicting safe regions within lava flows over topography. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 127, e2022JB024167 (2022).

Hyman, D. M. R., Dietterich, H. R. & Patrick, M. R. Toward next-generation lava flow forecasting: development of a fast, physics-based lava propagation model. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 127, e2022JB024998 (2022).

Favalli, M., Pareschi, M. T., Neri, A. & Isola, I. Forecasting lava flow paths by a stochastic approach. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, 1–4 (2005).

Körner, C., Paulsen, J. & Spehn, E. M. A definition of mountains and their bioclimatic belts for global comparisons of biodiversity data. Alp. Bot. 121, 73–78 (2011).

John Gerrard. Mountain Environments: An Examination of the Physical Geography of Mountains (MIT Press, 1990).

Meybeck, M., Green, P. & Vörösmarty, C. A new typology for mountains and other relief classes. Mt Res. Dev. 21, 3445 (2001).

Snethlage, M. A. et al. A hierarchical inventory of the world’s mountains for global comparative mountain science. Sci. Data 9, (2022).

Sayre, R. Global Mountains K3 (Geological Survey, 2023).

Karagulle, D. et al. Modeling global Hammond landform regions from 250-m elevation data. Trans. GIS. 21, 1040–1060 (2017).

Grant, G. E. & Swanson, F. J. Morphology and Processes of Valley Floors in Mountain Streams, Western Cascades, Oregon. In Natural and Anthropogenic Influences in Fluvial Geomorphology (eds. Costa, J. E., Miller, A. J., Potter, K. W. & Wilcock, P. R.) 83–101 (American Geophysical Union, 1995).

Brocard, G. Y. & Van Der Beek, P. A. Influence of incision rate, rock strength, and bedload supply on bedrock river gradients and valley-flat widths: Field-based evidence and calibrations from western Alpine rivers (southeast France). Spec. Pap. Geol. Soc. Am. 398, 101–126 (2006).

Sweeney, K. E. & Roering, J. J. Rapid fluvial incision of a late Holocene lava flow: insights from LiDAR, alluvial stratigraphy, and numerical modeling. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 129, 500–512 (2017).

Dietterich, H. R., Lev, E., Chen, J., Richardson, J. A. & Cashman, K. V. Benchmarking computational fluid dynamics models of lava flow simulation for hazard assessment, forecasting, and risk management. J. Appl. Volcanol. 6, 9 (2017).

Biass, S. et al. Complex staged emplacement of a basaltic lava: The example of the July 1974 flow of Kīlauea. Bull Volcanol. 87, 30 (2025).

Soule, S. A., Cashman, K. V. & Kauahikaua, J. P. Examining flow emplacement through the surface morphology of three rapidly emplaced, solidified lava flows, Kîlauea Volcano, Hawai’i. Bull. Volcanol. 66, 1–14 (2004).

Pedersen, G. B. M. et al. Lava flow hazard modeling during the 2021 Fagradalsfjall eruption, Iceland: applications of MrLavaLoba. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 3147–3168 (2023).

Espanon, V. R., Chivas, A. R., Phillips, D., Matchan, E. L. & Dosseto, A. Geochronological, morphometric and geochemical constraints on the Pampas Onduladas long basaltic flow (Payún Matrú Volcanic Field, Mendoza, Argentina). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 289, 114–129 (2014).

Pasquarè, G. et al. Very long pahoehoe inflated basaltic lava flows in the Payenia volcanic province (Mendoza and La Pampa, Argentina). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 293, 46–56 (2015).

Brown, C., Bryan, S. E., Gust, D. A. & Dalton, H. Insights into the development of small-volume long lava flows: a case study of the Coalstoun Lakes volcanic field, southeast Queensland, Australia. J. Volcanol. Geothermal Res. 451, 108115 (2024).

Latutrie, B., Harris, A., Van Wyk de Vries, B., Gurioli, L. & Médard, E. Emplacement of lava flows on eroded terrain, part I: the case of the Tiretaine valley (Chaîne des Puys, France). J. Volcanol. Geothermal Res. 438, 107808 (2023).

Dietterich, H. R., Downs, D. T., Stelten, M. E. & Zahran, H. Reconstructing lava flow emplacement histories with rheological and morphological analyses: the Harrat Rahat volcanic field, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Bull Volcanol. 80, 85 (2018).

Borch, A., Russell, J. K. & Barendregt, R. W. Cheakamus basalt lavas, British Columbia: a Pleistocene record of rapid, continuous eruption within a mountainous drainage system. Can. J. Earth Sci. 60, 1544–1572 (2023).

Takagi, D. & Huppert, H. E. The effect of confining boundaries on viscous gravity currents. J. Fluid Mech. 577, 495–505 (2007).

Merle, O. The scaling of experiments on volcanic systems. Frontiers in Earth Sci. 3, 26 (2015).

Jeffreys, H. LXXXIV. The flow of water in an inclined channel of rectangular section. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 49, 793–807 (1925).

Macdonald, G. A. The 1959 and 1960 eruptions of Kilauea volcano, Hawaii, and the construction of walls to restrict the spread of the lava flows. Bull. Volcanol. 24, 249–294 (1962).

Brigham, W. T. Notes on the volcanic phenomena of the Hawaiian Islands, with a description of modern eruptions. Mem. Read. Boston Soc. Nat. Hist. 1, 341–472 (1868).

Nichols, R. L. Velocity of basaltic flows indicated by lava trees. Eos. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 21, 357 (1940).

Moore, J. & Richter, D. Lava tree molds of the September 1961 eruption, Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 73, 1153–1158 (1962).

Lockwood, J. P. & Williams, I. S. Lava Trees and Tree Moulds as Indicators of Lava Flow Direction. http://journals.cambridge.org (2015).

Richter, D. H. Chronological Narrative of the 1959-60 Eruption of Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii: A Detailed and Pictorial Account of an Eruptive Sequence Consisting of a Summit Eruption, a Flank Eruption, and a Summit Collapse (United States Government Printing Office, 1970).

Barberi, F. & Carapezza, M. L. The control of lava flows at Mt. Etna, in Geophysical Monograph Series vol. 143 (Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004).

Crow, R., Karlstrom, K. E., McIntosh, W., Peter, L. & Dunbar, N. History of Quaternary volcanism and lava dams in western Grand Canyon based on lidar analysis, 40Ar/39Ar dating, and field studies: implications for flow stratigraphy, timing of volcanic events, and lava dams. Geosphere 4, 183–206 (2008).

Dawson, J. B., Pinkerton, H., Norton, G. E. & Pyle, D. M. Physicochemical properties of alkali carbonatite lavas: data from the 1988 eruption of Oldoinyo Lengai, Tanzania. Geology 18, 260–263 (1990).

Cas, R., Giordano, G. & Wright, J. V. Volcanology (Springer Nature, 2024).

Harris, A. J. L. & Rowland, S. K. Lava Flows and Rheology. The Encyclopedia of Volcanoes https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385938-9.00017-1 (Elsevier Inc., 2015).

Le Moigne, Y. et al. Standing waves in high speed lava channels: a tool for constraining lava dynamics and eruptive parameters. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 401, 106944 (2020).

Wolfe, E. W. The Puu Oo eruption of Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii: episodes 1 through 20, January 3, 1983, through June 8, 1984. USGS Prof. Pap. 1350, 471–508 (1988).

Geist, D. J. et al. The 2005 eruption of Sierra Negra volcano, Galápagos, Ecuador. Bull. Volcano. 70, 655–673 (2008).

Dietterich, H. R., Grant, G. E., Fasth, B., Major, J. J. & Cashman, K. V. Can lava flow like water? Assessing applications of critical flow theory to channelized basaltic lava flows. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 127, 9 (2022).

James, C. S. Hydraulic Structures. Hydraulic Structures (Springer International Publishing, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34086-5.

Spera, F. J., Borgia, A., Strimple, J. & Feigenson, M. Rheology of melts and magmatic suspensions. 1. Design and calibration of concentric cylinder viscometer with application to rhyolitic magma. J. Geophys. Res. 93, 10273–10294 (1988).

Bagdassarov, N. & Pinkerton, H. Transient phenomena in vesicular lava flows based on laboratory experiments with analogue materials. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 132, 115–136 (2004).

Pinkerton, H. & Stevenson, R. J. Methods of determining the rheological properties of magmas at sub-liquidus temperatures. J. Volcanol. Geothermal Res. 53, 47–66 (1992).

Shaw, H. R., Wright, T. L., Peck, D. L. & Okamura, R. The viscosity of basaltic magma: an analysis of field measurements in Makaopuhi lava lake, Hawai’i. Am. J. Sci. 266, 225–264 (1968).

Smith, J. V. Textural evidence for dilatant (shear thickening) rheology of magma at high crystal concentrations. J. Volcanol. Geothermal Res. 9, 1–7 (2000).

Kolzenburg, S., Giordano, D., Cimarelli, C. & Dingwell, D. B. In situ thermal characterization of cooling/crystallizing lavas during rheology measurements and implications for lava flow emplacement. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 195, 244–258 (2016).

Lejeune, A. M. & Richet, P. Rheology of crystal-bearing silicate melts: an experimental study at high viscosities. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 4215–4229 (1995).

Sakimoto, S. E. H. & Zuber, M. T. Flow and convective cooling in lava tubes. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 103, 27465–27487 (1998).

Pinkerton, H. & Norton, G. Rheological properties of basaltic lavas at sub-liquidus temperatures: laboratory and field measurements on lavas from Mount Etna. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 68, 307–323 (1995).

Robertson, J. C. & Kerr, R. C. Solidification dynamics in channeled viscoplastic lava flows. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 117, B7 (2012).

Lev, E., Rumpf, E. & Dietterich, H. Analog experiments of lava flow emplacement. Ann. Geophys. 62, 61 (2019).

Jones, T. J. & Llewellin, E. W. Convective tipping point initiates localization of basaltic fissure eruptions. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 553, 116637 (2021).

Jones, T. J., Reynolds, C. D. & Boothroyd, S. C. Fluid dynamic induced break-up during volcanic eruptions. Nat. Commun. 10, 3828 (2019).

Llewellin, E. W., Mader, H. M. & Wilson, S. D. R. The rheology of a bubbly liquid. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 458, 987–1016 (2002).

Buckingham, E. On physically similar systems: illustrations of the use of dimensional equations. Phys. Rev. 4, 345–376 (1914).

Jones, T. J. & Ehlers, T. A. Using benchtop experiments to teach dimensional analysis and analogue modeling to graduate geoscience students. J. Geosci. Educ. 69, 313–322 (2021).

Global Volcanism Program & Venzke, E. Volcanoes of the world (v. 5.2.7; 21 Feb 2025). Smithsonian Institute. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.VOTW5-2024.5.2 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The senior author (AB) was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) through a Doctoral Post-Graduate Scholarship (PGS D). We also acknowledge funding via the UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship programme (TJJ, MR/W009781/1) and the NSERC Discovery Grants programme (JKR, RGPIN-2018-03841). Laboratory assistance was kindly provided by Pier Paolo Comida and Marie Hagenbourger.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceived by JKR and TJJ. Experimental design and experimentation were executed by AB and TJJ. All authors were involved in the interpretation and implications of the datasets, as well as the generation of figures and the writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks William Moreland and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Domenico Doronzo, Carolina Ortiz Guerrero and Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borch, A., Jones, T.J. & Russell, J.K. Lava effusion in mountainous terrain generates flow backup and excess inundation. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1039 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02991-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02991-x