Abstract

Ammonia (NH3) emissions from agricultural lands represent a major environmental concern, with current emission models heavily relying on inherent soil pH as a key determinant based on chemical equilibrium principles. Here, analyzing 1792 field measurements across global croplands, we demonstrate that soils with inherently higher pH generally have lower NH3 emissions. We identify enhanced nitrification as the key mechanism, where higher pH promotes rapid NH3 oxidation, thereby reducing substrate availability for NH3 volatilization. This biological process can reduce NH3 emissions by 11% per unit increase in inherent soil pH. In paddy rice, nitrification is inhibited due to the flooded environment, leading to higher emission factors (EF) than upland crops, with EF positively correlating with pH above approximately 7.5. Our findings highlight that current emission inventories may substantially misestimate NH3 emissions by oversimplifying pH effects and overlooking biological processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ammonia (NH3) represents one of the major air pollutants1, and its deposition into ecosystems can lead to acidification, eutrophication2, biodiversity loss3, and increased nitrous oxide emissions4. According to global estimates of NH3 emissions, croplands are the largest source, contributing about 14.4 Tg N yr−1 or over 50% of anthropogenic emissions5. Accurate NH3 emission factors (EF) are essential for precisely estimating NH3 emissions from croplands, assessing their environmental impacts, and evaluating the potential of emission reduction measures.

Current NH3 emission inventories rely heavily on soil pH as a key determinant6,7, based on the chemical equilibrium principle that higher pH shifts \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) towards NH38,9. This principle underpins EF calculations and mitigation strategies worldwide. However, recent evidence challenges this established paradigm. In an empirical model on NH3 EF from Chinese croplands, soil pH was excluded in stepwise regression, indicating its influence might be less important than previously thought10. Another study using nonlinear models showed that the coefficient for the pH term had an uncertainty interval including zero, suggesting that pH seems not to be a significant factor11. Moreover, a more recent work, which used machine learning to determine global EF, did not identify a strong influence of pH11. Conversely, the trend in the latest integrated datasets suggests that average EFs are lower at higher pH values11,12, thus contradicting previous understanding9. These discrepancies suggest critical gaps in our mechanistic understanding of soil NH3 dynamics and challenge the validity of the current emission inventories.

Here, using a global dataset of 1792 NH3 emission measurements, combined with statistical analysis and machine learning, we provide evidence that elevated soil pH consistently reduces rather than increases NH3 emissions across diverse agricultural systems. We identify enhanced nitrification as the key mechanism, where higher pH promotes rapid \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) oxidation, thereby reducing substrate availability for NH3 volatilization. This finding reveals the overlooked importance of biological processes in controlling NH3 emissions and suggests the need for a fundamental reconsideration of current emission models.

Results

Inherently higher soil pH significantly reduces NH3 emission

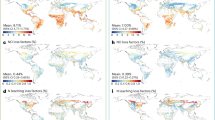

We conducted an analysis of 1792 empirical EF measurements from global agricultural fields and identified significant differences in both inherent soil pH (unless otherwise stated, soil pH in this article represents inherent soil pH) and EFs of wheat, maize, and paddy rice (Fig. 1a–c). Paddy rice exhibited a notably higher average EF (16.0%) compared to maize (9.2%) and wheat (8.2%). The average soil pH for paddy rice was the lowest among the three crops (pH = 6.5), likely caused by flooded and anaerobic conditions. Overall, the ranking of pH values across the three crops was inversely correlated with their average EF, suggesting that higher inherent soil pH did not necessarily exhibit a uniformly higher EF. Otherwise, maize would have exhibited the highest average EF. To minimize the influence of inter-crop variability, we conducted separate regression analyses of pH and EF for each crop. The results consistently revealed negative correlations, although statistical significance (p < 0.05) was not achieved for maize and paddy rice (Fig. 1d–f).

a Geographical distribution of the sample sites; boxplots of average emission factor (EF) (b) and soil pH (c) for paddy rice, wheat and maize in the dataset; The boxplots show the median (line inside the box), mean (cross in the box), 25th and 75th percentile (top and bottom edges of the box), and 5th and 95th percentile (whiskers) value. Linear regression between soil pH and EF for paddy rice (d), maize (e), and wheat (f). The dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals.

To control for the influence of other factors, we considered both environmental and management variables and conducted multiple linear regression analyses for each of the three crops (Supplementary Fig. 1). The results indicated a significant negative correlation between inherent soil pH and EF across all crops (Supplementary Table 1), with the strength of this relationship for paddy rice being slightly smaller. On average, a one-unit higher inherent pH was associated with a 2.3% reduction in EF for maize, a 2.4% reduction for wheat, and a 1.5% reduction for paddy rice.

Another intriguing finding was that the difference in EF between paddy rice and upland crops could not be fully attributed to variation in growth temperature and precipitation. We coded crop type with two dummy variables for rice and wheat, using maize as the reference group (i.e., both dummy variables equal to zero when the crop is maize), and conducted a multiple linear regression including these crop-type variables together with environmental and management factors. The results showed that paddy rice had a significant coefficient of 5.98 (p < 0.001), indicating an EF difference of about 6.0% compared with maize. This difference could not be explained by environmental and management factors. In contrast, wheat showed no significant difference relative to maize (Supplementary Table 2). This difference between paddy rice and upland crops has been attributed to daytime algal photosynthesis in the irrigation water of rice paddies, which increases pH and enhances ammonia volatilization13. However, diel pH fluctuations in rice paddies typically diminish after the crop establishment period14, and experiments using algal inhibitors demonstrated that algal activity accounts for only about half of the observed EF difference between paddy rice and upland crops15. This suggests that there are still other unknown mechanisms for the high EF of paddy rice.

Heterogeneity in the effects of inherent soil pH on EF

The effect of inherent soil pH on EF may vary across different crops, management practices, and environmental conditions. To explore this variability, we conducted heterogeneity analyses across the three crops. Specifically, we grouped the data based on fertilizer type, organic amendments, fertilizer placement method, control-release fertilizers (CRFs), soil cation exchange capacity (CEC), and N application rate, and performed multiple linear regressions within each subgroup.

Soil pH exhibited a comparatively smaller effect on the EF of paddy rice than on maize and wheat, with several subgroups showing different patterns with upland crops (Fig. 2). For instance, soil pH showed a significant influence on paddy rice EF under deep fertilizer placement. By contrast, for maize and wheat, pH exerted a more pronounced effect on EF when fertilizers were surface applied.

Estimates of linear regression on the subgroups for paddy rice (a), maize (b), and wheat (c). Levels of N application rates (N rate) and cation exchange capacity (CEC) were divided by median value for each crop. Detailed information for each subgroup can be found in Supplementary Table 3. The asterisks indicate the statistical significance level based on p values: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. The error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

The negative impact of pH on EF was particularly evident with urea application compared with other fertilizers, such as compound fertilizers or ammonium nitrate. Similarly, manure application amplified the negative effect of pH on EF for maize and wheat, whereas no significant effect was observed for paddy rice. Following CRFs-mediated modulation of \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) release, the influence of pH on EF was not statistically significant in wheat but was considerably reduced in maize. However, in paddy rice, CRFs resulted in a slight increase in the pH effect on EF. These results suggest that the proportion of \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) in fertilizers influences the magnitude of pH effects on EF, with higher \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) proportions amplifying the negative impact of pH. Soil CEC further modulated this relationship. In low-CEC soils, the effect of pH on EF was more pronounced, whereas in high-CEC soils, the impact became non-significant for both paddy rice and maize, likely due to greater \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) adsorption reducing \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) availability for NH3 volatilization9.

However, at high N application rates, the influence of pH on EF diminished. This could potentially be attributed to high N application rates exceeding the soil’s CEC adsorption capacity and the utilization capacity of microorganisms, thereby disrupting the mechanisms through which pH influences EF. However, this hypothesis warrants further investigation.

Enhanced nitrification in inherently higher pH soils

The negative impact of pH on EF contradicts the principles of chemical equilibrium16, which may be influenced by biological processes. Specifically, this counterintuitive effect of pH on EF may be related to soil nitrification processes. If \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) is rapidly converted to \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{O}}}_{3}^{-}\), NH3 volatilization is reduced.

To test our hypothesis, we extracted data from two published meta-analyses17,18 and conducted a re-analysis. We found that an increase in inherent soil pH significantly enhanced nitrification intensity, with an average inherent pH rise of one unit leading to approximately a 38% increase in nitrification (Fig. 3a). This is mainly because the concentration of free NH3 is higher under elevated pH, which is generally considered the substrate for ammonia-oxidizing microorganism19. For the surface 10 cm of the soil, we estimated net nitrification rates of ~5 kg N ha−1 d−1 under high pH conditions (close to pH = 9.0). Thus, the rate of nitrification is sufficient to have a considerable effect.

a Impact of pH on net nitrification rate; b Effect of nitrification inhibitor (NI) on soil \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) concentration at different soil pH; c Effect of NI on soil NH3 emission at different soil pH. Relative concentration and emission indicate the ratio of \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) concentration or NH3 emission when NI is applied compared to when no NI applied. The bubble size in a represents the sample size. The dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals.

To further assess whether nitrification significantly impacts NH3 emissions, we analyzed the effects of nitrification inhibitor (NI) on soil exchangeable \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) concentration and NH3 emissions in relation to inherent soil pH (Fig. 3b, c). The efficiency of NI increased significantly with higher pH. The increase in NH3 emissions when NI is applied is attributable to the suppression of nitrification in soil. By comparing results from scenarios with and without NI, the specific contribution of nitrification can be isolated. This comparison revealed that for each unit increase in inherent soil pH, enhanced nitrification reduced soil \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) concentration by 27% and NH3 emissions by 11%. This indicated that the effect of inherently higher soil pH promoting the conversion of \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) to NH3 was offset by nitrification, resulting in a slight overall decrease in EF with higher pH. It is important to acknowledge that NI cannot completely suppress nitrification, potentially leading to an underestimation of nitrification’s impact.

Based on the above analysis, we can summarize the mechanism by which inherent soil pH affects NH3 emissions. In unfertilized soils, the availability of NH3 as a substrate is limited. Therefore, higher pH increases the availability of NH3 and enhances the activity of nitrification-related microorganisms17,20. After nitrogen fertilization, soil pH changes rapidly in the short term (e.g., hydrolysis of the commonly used urea leads to a rise in pH). Under these conditions, soil NH3 availability and the initial pH are no longer the determining factors. Instead, the initial nitrification capacity becomes the dominant factor. A rapid initial nitrification process consumes NH3 more quickly and generates H+, which reduces NH3 emissions. Previous studies have shown that in nitrogen-limited forests, nitrification shows a lag after disturbance, whereas in nitrogen-rich forests, disturbance leads to an immediate loss of \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{O}}}_{3}^{-}\)21. It has also been demonstrated that NH3 emission decreases significantly following application of a small amount of urea in advance, thus initiating nitrification22. These support the mechanism that elevated initial nitrification in inherently higher pH soils will lead to decreased NH3 emissions after fertilization.

The significant negative impact of nitrification on NH3 emissions also explained the previously contradictory observations. Firstly, nitrification requires oxygen; flooded conditions of rice paddies are therefore unfavorable for nitrification, which may be one of the reasons for the relatively high NH3 emissions. This also explains why the effect of pH on paddy rice was minimal, as nitrification is strongly suppressed over the full pH range. Furthermore, the heterogeneity analysis revealed that the impact of pH was more pronounced when \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) concentrations were high, likely because the under high \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) availability accelerates the rate of nitrification. At high N-fertilizer application rates (e.g., often exceeding 150 kg N ha−1 yr−1 in China), N inputs far surpass the capacity of nitrification. Therefore, although higher pH accelerates nitrification rates, its effect on NH3 emissions becomes limited relative to N inputs, making the influence of pH less significant compared to lower N application rates. In the case of deep fertilizer placement, \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) tended to remain within the soil over an extended period, rendering the nitrification rates less impactful. Consequently, the effect of pH was less pronounced compared to surface fertilizer application.

Soil pH is not enough for predicting EF

Although multiple linear regressions show a significant effect of inherent soil pH on EF, they can only indicate the overall direction of the effect (positive or negative) and cannot reveal the specific pattern of influence, such as a parabolic or nonlinear relationship. To address this issue, we developed a machine learning model and utilized the interpretability framework of SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values to elucidate the influence of various factors on EF (Supplementary Fig. 2)23.

For both wheat and maize, EF exhibited a downward trend with increasing pH, whereas for paddy rice, EF increased at higher pH levels (pH > 7) (Fig. 4a–c). This phenomenon is likely attributed to the weak nitrification process in rice paddies, where higher pH conditions predominantly facilitate the conversion of \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) into NH3, thus increasing NH3 emission. This observation aligns well with our proposed hypothesis. The effect of pH on EF was within 5%, indicating that EF does not exhibit pronounced fluctuations with changes in inherent soil pH. This may be because the promoting effect of inherently higher soil pH on NH3 emissions and its promoting effect on nitrification, which in turn inhibits NH3 emissions, counteract each other. As a result, although soils with inherently higher pH generally have lower EF, the impact is not large.

By averaging the absolute SHAP values of each variable to represent their relative importance, and simultaneously considering the feature importance derived from the random forest model, we found that environmental factors, such as climate and soil are even more important than soil pH in predicting EF, as these factors also have important impacts on soil NH3 emission-related processes (Fig. 4d). Temperature (Fig. 4e) and water input (Fig. 4i) increase EF, as more water can enhance \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) hydrolysis, and higher temperatures reduce NH3 solubility24,25,26. Particularly, EF increased sharply beyond 25 °C in paddy rice, likely due to the increasing biological oxygen demand and thus weaker nitrification under excessively high temperatures27. However, extremely low temperature and water input markedly raised EF, because extreme dryness limits substrate diffusion and inhibit nitrification28, and low temperature slows nitrogen utilization rate of soil microbes29. Clay content exhibited a negative impact on EF (Fig. 4g), as higher clay content could adsorb more \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\)9. Soil organic carbon (SOC) is also a key contributor to CEC, and both CEC (Fig. 4h) and SOC (Fig. 4f) showed a U-shaped contribution to EF. Low CEC results in weak \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) adsorption, while high CEC, associated with high SOC and total soil nitrogen, also leads to increased EF30.

It should be noted that the importance ranking in Fig. 4d only represents the overall impact of each variable on the prediction of EF and does not fully reflect the influence on EF. It also does not imply that soil pH is not important for NH3 emissions. For example, although temperature show high importance for the prediction, its effect on EF is minimal within a wide range (e.g., 10–20 °C) as shown in Fig.4e. However, it can be concluded that pH and other environmental factors are of significant importance in predicting EF. Besides, management factors such as placement and type of nitrogen fertilizer also have significant impacts on NH3 emission11. These imply that accurate prediction of EF necessitates the integration of multiple environmental and management factors.

Discussion

Many studies have reported a significant positive correlation between pH and EF31,32,33,34. However, these studies typically used the pH measured after fertilization rather than the inherent soil pH. This seemingly reverses the causality because changes in pH after fertilization are a consequence of fertilization, not a cause of the differences in NH3 emissions. Laboratory experiments or studies that altered the original soil pH must be interpreted with caution35, as the composition of the native soil microbiome may have been disrupted. By contrast, our study used field measurements, providing a more accurate reflection of real-world conditions.

Some studies that examined the relationship between inherent soil pH and EF did not identify a significant positive correlation. As a result, many researchers have attributed the observed relationship to soil pH buffering capacity36,37, arguing that significant pH changes occur after fertilization and thereby driving a positive correlation between post-fertilization pH and EF. However, this explanation does not adequately account for the fact that soils with inherently high pH still exhibit lower EF compared to those with lower pH. In contrast, our explanation offers a plausible interpretation that aligns with the experimental evidence and helps reconcile these observations.

Spatial scale may also play an important role. Previous research found that within a range of 50 m, pH shows a weak positive correlation with NH3 volatilization, whereas on larger scales, a significant negative correlation is observed38. In single-site studies, the overall soil properties are similar, so that local pH variations have a pronounced effect on the chemical equilibrium between \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) and NH3. However, when comparing studies across multiple sites, inherent soil differences become dominant. Modeling across different scales requires accounting for these varying effects. There has been a tendency to overemphasize micro-scale chemical processes, while overlooking the differences and complexities of soils and soil microbiota at macro scales.

In polluted rivers or wastewater, high \({\mbox{N}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{4}^{+}\) concentrations can inhibit nitrification39. However, considering the intensity of mineralization in agricultural soils, unfertilized soils seldom reach concentrations sufficient to inhibit nitrification40. In fact, inhibition of nitrification due to low NH3 is more common in unfertilized soils19. Additionally, previous studies show that nitrification can be inhibited at pH values above 8.541,42. However, this inhibition primarily affects the nitrite oxidation process, with ammonia oxidation being less impacted. The latter is a critical process for reducing NH3 emissions. Furthermore, agricultural soil pH typically ranges from 4.5 to 8.5, and within this range, the trend of increasing nitrification with higher inherent soil pH is reliable17.

The conclusions of this study are robust against collinearity issues. While natural soils with higher precipitation tend to have lower pH, complicating the separation of the effects of precipitation and pH, our dataset revealed no significant collinearity among the variables (Supplementary Table 4). This can be largely attributed to the fact that the cropland is under human management and that we based our analysis on temperature and precipitation averages for the crop growing season, rather than on annual values. Another source of uncertainty is the potential mismatch between the two independent meta-analysis datasets and our EF dataset. Because studies simultaneously reporting ammonia emissions, nitrification, and NI effects are very limited, this integration was a necessary but imperfect approach. Spatially, the EF and meta-analysis datasets are generally consistent, covering major regions such as Asia, North America, and Europe (Supplementary Fig. 3). Comparisons of key climate and soil variables showed that the NI dataset did not differ significantly from the EF dataset in temperature, precipitation, soil pH, or clay content (Mann–Whitney U test, p > 0.05), whereas the nitrification dataset differed significantly in soil properties but not in temperature. Due to data limitations, management practices could not be compared across datasets. Such partial mismatches may influence the estimated strength and heterogeneity of pH and nitrification effects to some extent, but are not expected to substantially affect the overall validity of our conclusions, as the observed patterns are consistent and mutually supported across the three independent datasets.

We applied the widely used models from previous studies8,9 to the dataset used in this study and found that neither could effectively reproduce the observed data trends (Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore, improving existing methods that overly emphasize pH is critical for air quality and nitrogen deposition modeling, and developing NH3 emission control strategies. By contrast, the random forest model we developed demonstrated strong predictive performance during cross-validation. Soil pH, as a straightforward and commonly available metric, is frequently employed in models of biogeochemical processes, particularly at macro scales, where pH serves as a high-resolution indicator with relatively high accuracy. However, pH plays a complex role in biogeochemical processes, and current modeling approaches often oversimplify this complexity43. Given the nonlinear effects and interactions of environmental factors, we recommend the use of data-driven models, such as random forest models, in practical applications. However, it is important to carefully consider the model’s interpretability in relation to underlying mechanisms, rather than focusing solely on predictive performance, as this could lead to overfitting and incorrect predictions.

Methods

Data sources and compilation

We compiled a global dataset of NH3 EF through an extensive literature review. Using keywords including “ammonia emission”, “maize”, “wheat”, and “rice”, we conducted searches on the Web of Science and CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) databases. Additionally, we integrated data provided by the most recent dataset11. After screening, we obtained 2402 EF observations from 264 publications, including 610 data points involving the use of CRFs. Our dataset is slightly smaller than previous compilations because we excluded all experiments lacking a blank control, whereas the earlier study included data from locations where blank controls were reported in other studies. We did not collect data for crops, such as vegetables and fruits, as the three major cereal crops (maize, paddy rice, and wheat) account for over half of global NH3 emissions44, and studies on other crops are comparatively sparse. Furthermore, the data from the three major cereals are sufficient for the mechanistic exploration targeted in this research.

The EF values were calculated using Eq. 1:

where \({E}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}}\) represents the NH3 emission at a nitrogen application rate of N, and \({E}_{0}\) represents the emission from the blank control.

In addition to emissions and nitrogen application rates, we compiled ancillary data for each study, including soil characteristics (SOC content, clay content, CEC, and pH), climatic conditions (growing season temperature and precipitation), crop types (maize, paddy rice, and wheat), fertilizer types (e.g., urea, compound fertilizer, organic fertilizer, straw, and CRFs), fertilization methods (deep placement, surface broadcasting, and mixing), tillage practices (no-tillage, and conventional tillage), and irrigation amounts. For missing soil data, we extracted values based on the study’s geographical coordinates from the SoilGrids database45, while climate data were obtained from WorldClim46. To facilitate statistical analysis, all categorical variables were one-hot encoded, converting them into binary (0–1) variables.

Statistical analysis

First, we assessed multicollinearity among variables using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and found no significant multicollinearity (Supplementary Table 4). VIF quantifies how much the variance of an estimated regression coefficient is inflated due to multicollinearity among predictors. It is calculated by regressing each predictor on all other predictors in the model, yielding an R2 value for this auxiliary regression. The VIF for that predictor is then 1/(1-R2), indicating the degree to which it is explained by its counterparts. Subsequently, we employed multiple linear regression to examine the relationship between pH and EF. The crop types were completely collinear, so we retained wheat and paddy rice as variables, with their regression coefficients representing the differences in EF relative to maize. To facilitate comparison among coefficients, all continuous variables were standardized to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, allowing the magnitude of regression coefficients to directly reflect the influence of each variable on EF. Observations involving the use of CRFs were excluded from the regression analysis, and they were utilized only in the heterogeneity analysis specific to CRFs.

For the heterogeneity analysis, we considered factors including the use of urea, use of organic fertilizers, surface application versus deep placement of nitrogen fertilizers, use of CRFs, and variations in CEC and nitrogen application rates. The classification of CEC and nitrogen application rates into high and low categories was determined relative to the median value for each crop. Variables such as temperature and precipitation were not included, as they exhibited significant differences across crop types and also within the same crop type (e.g., early season and late season rice) (Supplementary Fig. 5). Both the heterogeneity analysis and the multiple linear regression were conducted using R version 4.2.3.

Re-analysis of soil pH and nitrification

To investigate the relationship between soil pH and soil nitrification, we reanalyzed data from two meta-analyses17,18. Given the relatively abundant measurements for nitrification, the data were grouped into intervals of 0.1 pH units. For each pH value, the mean was calculated across all data points, and the square root of the sample size was used as the weight in regression analyses. This approach prevents overrepresentation of data from pH ranges with disproportionately high numbers of measurements. To explore the relationship between NIs and ammonia emissions, we calculated the ratios of \({{\mbox{NH}}}_{4}^{+}\) concentrations and NH3 emissions with and without NIs for each study and performed regression analyses against pH.

Model development of machine learning

To characterize the complex, nonlinear relationships between EF, pH, and other variables, we developed a random forest model. The dataset was split into training and testing subsets at an 8:2 ratio, and the model achieved an R2 of 0.67 on the testing set. Subsequently, SHAP values (SHapley additive exPlanations) were computed for the entire dataset using the trained model23. Compared with linear regression, machine learning models not only better capture the nonlinear interactions between pH and EF but also, through SHAP values, reveal how each variable influences EF beyond simply indicating positive or negative effects.

The mean absolute SHAP value for each factor was used to assess its relative importance, as this metric quantifies the magnitude of each factor’s impact on EF. To ensure robustness, we also employed the feature importance metric inherent to the random forest model. If the relative importance rankings derived from these two methods were consistent, the results were considered reliable.

Data availability

The ammonia emission dataset used in the analysis and all the source data for the figures can be found at Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30172645)47.

Code availability

The code for machine learning can be found at Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28607021)48. The model was run on Python 3.11.

References

Wang, S. et al. Impact assessment of ammonia emissions on inorganic aerosols in East China using response surface modeling technique. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 9293–9300 (2011).

Yu, Q. et al. A probe into the acid deposition mitigation path in China over the last four decades and beyond. Natl. Sci. Rev. 11, nwae007 (2024).

Payne, R. J. et al. Nitrogen deposition and plant biodiversity: past, present, and future. Front. Ecol. Environ. 15, 431–436 (2017).

Xie, D., Si, G., Zhang, T., Mulder, J. & Duan, L. Nitrogen deposition increases N2O emission from an N-saturated subtropical forest in southwest China. Environ. Pollut. 243, 1818–1824 (2018).

Monforti Ferrario, F. et al. in http://data.europa.eu/89h/df521e05-6a3b-461c-965a-b703fb62313e (European Commission, Joint Research Centre, 2022).

European Environment Agency. EMEP/EEA air pollutant emission inventory guidebook 2023 (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2023).

MOE. Technical Guidelines for the Preparation of Atmospheric Ammonia Source Emission Inventories https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/bgg/201408/W020140828351293771578.pdf (2014).

Huang, X. et al. A high-resolution ammonia emission inventory in China. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26, GB1030 (2012).

Bouwman, A. F., Boumans, L. J. M. & Batjes, N. H. Estimation of global NH3 volatilization loss from synthetic fertilizers and animal manure applied to arable lands and grasslands. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 16, 8-1–8-14 (2002).

Wang, C. et al. An empirical model to estimate ammonia emission from cropland fertilization in China. Environ. Pollut. 288, 117982 (2021).

Xu, P. et al. Fertilizer management for global ammonia emission reduction. Nature 626, 792–798 (2024).

Zhou, F. et al. Re-estimating NH3 emissions from Chinese cropland by a new nonlinear model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 564–572 (2016).

Bowmer, K. H. & Muirhead, W. A. Inhibition of algal photosynthesis to control pH and reduce ammonia volatilization from rice floodwater. Fertil. Res. 13, 13–29 (1987).

Ito, A. Changes of water temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, inorganic nitrogen, and phosphorus concentrations in flowing irrigation water on paddy surface. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 33, 449–459 (1987).

Freney, J. R., Keerthisinghe, D. G., Phongpan, S., Chaiwanakupt, P. & Harrington, K. J. Effect of urease, nitrification and algal inhibitors on ammonia loss and grain yield of flooded rice in Thailand. Fertil. Res. 40, 225–233 (1994).

Sommer, S. G., Schjoerring, J. K. & Denmead, O. T. in Advances in Agronomy 82, 557–622 (Academic Press, 2004).

Li, Z. et al. Global patterns and controlling factors of soil nitrification rate. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 4147–4157 (2020).

Wu, D. et al. The importance of ammonia volatilization in estimating the efficacy of nitrification inhibitors to reduce N2O emissions: a global meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 271, 116365 (2021).

Lu, L. et al. Nitrification of archaeal ammonia oxidizers in acid soils is supported by hydrolysis of urea. ISME J. 6, 1978–1984 (2012).

Ni, G. et al. Nitrification in acidic and alkaline environments. Essays Biochem. 67, 753–768 (2023).

Vitousek, P. M., Gosz, J. R., Grier, C. C., Melillo, J. M. & Reiners, W. A. A comparative analysis of potential nitrification and nitrate mobility in forest ecosystems. Ecol. Monogr. 52, 155–177 (1982).

Fleisher, Z. & Hagin, J. Lowering ammonia volatilization losses from urea application by activation of nitrification process. Fertil. Res. 2, 101–107 (1981).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

Ma, R. et al. Global soil-derived ammonia emissions from agricultural nitrogen fertilizer application: a refinement based on regional and crop-specific emission factors. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 855–867 (2021).

Cai, G. X. et al. Nitrogen losses from fertilizers applied to maize, wheat and rice in the North China plain. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 63, 187–195 (2002).

Smith, E., Gordon, R., Bourque, C. & Campbell, A. Management strategies to simultaneously reduce ammonia, nitrous oxide and odour emissions from surface-applied swine manure. Can. J. Soil Sci. 88, 571–584 (2008).

He, Z. L., Alva, A. K., Calvert, D. V. & Banks, D. J. Ammonia voltilization from different fertilizer sources and effects of temperature and soil pH. Soil Sci. 164, 750–758 (1999).

Norton, J. & Ouyang, Y. Controls and adaptive management of nitrification in agricultural soils. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1931 (2019).

Black, A. S., Sherlock, R. R. & Smith, N. P. Effect of timing of simulated rainfall on ammonia volatilization from urea, applied to soil of varyingmoisture content. J. Soil Sci. 38, 679–687 (1987).

Xu, X. et al. Climate change may interact with nitrogen fertilizer management leading to different ammonia loss in China’s croplands. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 6525–6535 (2021).

Zhu, Z. L. et al. Processes of nitrogen loss from fertilizers applied to flooded rice fields on a calcareous soil in north-central China. Fertil. Res. 18, 101–115 (1988).

Fan, X. H., Song, Y. S., Lin, D. X., Yang, L. Z. & Zhou, J. M. Ammonia volatilization losses from urea applied to wheat on a paddy soil in Taihu region. China Pedosph. 15, 59–65 (2005).

Whitehead, D. C. & Raistrick, N. Ammonia volatilization from five nitrogen compounds used as fertilizers following surface application to soils. J. Soil Sci. 41, 387–394 (1990).

Das, P., Sa, J.-H., Kim, K.-H. & Jeon, E.-C. Effect of fertilizer application on ammonia emission and concentration levels of ammonium, nitrate, and nitrite ions in a rice field. Environ. Monit. Assess. 154, 275–282 (2009).

Nyord, T., Schelde, K. M., Søgaard, H. T., Jensen, L. S. & Sommer, S. G. A simple model for assessing ammonia emission from ammoniacal fertilisers as affected by pH and injection into soil. Atmos. Environ. 42, 4656–4664 (2008).

Ferguson, R. B., Kissel, D. E., Koelliker, J. K. & Basel, W. Ammonia volatilization from surface-applied urea: effect of hydrogen ion buffering capacity. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 48, 578–582 (1984).

Sunderlage, B. & Cook, R. L. Soil property and fertilizer additive effects on ammonia volatilization from urea. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 82, 253–259 (2018).

Corstanje, R., Kirk, G. J. D., Pawlett, M., Read, R. & Lark, R. M. Spatial variation of ammonia volatilization from soil and its scale-dependent correlation with soil properties. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 59, 1260–1270 (2008).

Yao, Q. et al. Effect of free ammonium and free nitrous acid on the activity, aggregate morphology and extracellular polymeric substance distribution of ammonium oxidizing bacteria in partial nitrification. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 124, 319–326 (2017).

Peng, X. U., Minghua, Z., Bo, Z. H. U. & Butterbach-Bahl, K. Regional assessment of soil nitrogen mineralization in diverse cropland of a representative intensive agricultural area. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 10, 530–540 (2023).

Le, T. T. H., Fettig, J. & Meon, G. Kinetics and simulation of nitrification at various pH values of a polluted river in the tropics. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 19, 54–65 (2019).

Shen, Q. R., Ran, W. & Cao, Z. H. Mechanisms of nitrite accumulation occurring in soil nitrification. Chemosphere 50, 747–753 (2003).

Ge, X., Xie, D., Mulder, J. & Duan, L. Reevaluating the drivers of fertilizer-induced N2O emission: insights from interpretable machine learning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 15672–15680 (2024).

Zhan, X. et al. Improved estimates of ammonia emissions from global croplands. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 1329–1338 (2020).

Poggio, L. et al. SoilGrids 2.0: producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty. SOIL 7, 217–240 (2021).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315 (2017).

Ge, X. et al. Dataset for: enhanced nitrification in higher pH soils moderates ammonia emissions in global croplands. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30172645 (2025).

Ge, X. et al. Code for: enhanced nitrification in higher pH soils moderates ammonia emissions in global croplands. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28607021 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project (2022YFC3700600 and 2023YFC3708500) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42277204).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.G. analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. D.X. and J.M. revised the paper and gave important suggestions. L.D. designed the study and improved the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the discussion and interpretation of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Guntur Venkata Subbarao, Wenchao Cao and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Somaparna Ghosh. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ge, X., Xie, D., Mulder, J. et al. Enhanced nitrification in higher pH soils moderates ammonia emissions in global croplands. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1020 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02997-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02997-5