Abstract

Regional thermochronology provides an important record of crustal exhumation through deep time. However, untangling the myriad of geodynamic, tectonic, climatic and surface processes responsible for long-term upper crustal cooling is often hindered by thermochronology data being conventionally interpreted in a static geographic framework. Here, we present a workflow for interpreting thermochronology data and thermal history models via integration with numerical plate tectonic, mantle convection, and paleoclimate reconstructions. Using a compilation of inverse thermal history models from Central Asia, based on fission-track and (U-Th)/He data, we demonstrate the power of placing thermochronology data in their paleogeographic context to untangle the geodynamic, tectonic and climate drivers of exhumation. This shows that the diachronous Mesozoic-to-recent (230-0 Ma) exhumation history of Central Asia was primarily controlled by reactivation of pre-Mesozoic crustal-scale shear zones in response to plate kinematics and Tethyan subduction dynamics, while dynamic topography and changes in paleoprecipitation played relatively insignificant roles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low-temperature thermochronology provides a powerful tool for constraining the thermal evolution of upper crustal materials over geological time. These radiometric dating methods are widely used to determine the timing and rate of geological processes that influence crustal thermal states. In some cases, thermal histories recorded by thermochronology can reflect conductive processes, such as geothermal gradient changes due to deep-seated batholith emplacement1, localised heating from intrusions2, or small-scale perturbations from lava flows and wildfires3,4. In other rare cases, they record convective hydrothermal fluid or groundwater flow5,6,7. However, in most cases, thermochronology data primarily document advective heat and mass transport driven by exhumation and burial from tectonic and surface processes2,8.

In active deformation zones where geological context is well preserved, spatiotemporal patterns in thermal histories can be interpreted more readily. Jumps in apparent cooling ages across faults9,10 and along-strike trends in thermal histories11,12,13,14,15,16 can provide 4D exhumation chronologies diagnostic of different strain regimes and fault system evolutions. However, in older, highly deformed regions where the geological record is fragmented, determining exhumation drivers is challenging. In these cases, interpretations often rely on speculative links to broader-scale processes, including far-field tectonic stresses17, dynamic topography18,19, and climate-driven erosion20,21,22.

In reality, long-term denudational cooling histories recorded by thermochronology data likely often reflect a combination of concurrently operating short wavelength tectonism (i.e., fault driven exhumation) and long wavelength geological processes (e.g., plate kinematics, dynamic topography, paleoclimate). To separate out the potential influence of long wavelength exhumation drivers, therefore, requires regional-scale spatiotemporal analysis to assess whether the distribution of detected periods of denudational cooling match what would be expected of these broad scale mechanisms.

The recent expansion of open-source geoscience modeling tools, notably the GPlates plate tectonic software23, offers new opportunities to integrate thermochronology with global Earth system models. Numerical plate tectonic reconstructions capture the time-dependent evolution of lithospheric plates and their boundaries, in a global context, and can be tied to mantle flow24, paleoclimate25, paleogeography26 and landscape evolution models27 to simulate the dynamic Earth system. Yet, besides some rare exceptions28, low-temperature thermochronology data are still routinely interpreted at the sub-regional scale in a static, present-day plate configuration. A key limitation has been the absence of open access thermochronology databases and integrated modeling workflows.

With the advent of the first geospatial relational thermochronology database29,30, a shift toward global-scale thermochronology modeling is now feasible. Here, we introduce an integrated workflow combining regional thermochronology with plate reconstructions, mantle convection models, and paleoclimate simulations, using the EarthBank platform (previously AusGeochem29,30,31) and GPlates23. This methodology enables thermochronology datasets to be analysed in their tectonic, geodynamic, and climatic contexts through deep time, and can be extended to incorporate additional datasets such as fault databases and paleotopography models.

To demonstrate this approach, we analyse a compiled dataset of 381 published thermal history models from Central Asia32, based on apatite, zircon and titanite fission-track analyses and (U-Th)/He dating of apatite and zircon (Fig. 1). We define the Central Asia study area by the density of published thermochronology data and thermal history models north of the Pamirs, stretching from Central Uzbekistan, Siberia and Mongolia to the west, north and east. There, at the heart of Central Asia, the Tian Shan and Altai mountains formed diachronously through multi-stage tectonism since the Mesozoic, yet debate persists over the precise timing and geodynamic drivers of their evolution20,33. While exhumation has been linked to distant Eurasian margin collisions, culminating in India-Eurasia convergence17, other factors such as tectonic inheritance8,34,35,36, subduction dynamics20, dynamic topography37,38, and paleoclimate variations21,22,39 have also been proposed. However, isolating these superimposed processes remains a challenge.

a Generalised tectonic map of Central Asia, showing distribution of major terranes, basins, locations of digitised thermal history models32, and fault systems88. The distribution of (b) apatite fission-track (AFT) apparent ages and (c) mean confined track lengths (MTL), a proxy for the rate of cooling whereby longer MTLs record faster cooling through ~120–60 °C56,57, are illustrated by inverse distance weighted interpolations. Note, that these interpolations are for illustrative purposes only and are not used in any subsequent analyses. Rather, all correlation analysis between cooling rates, dynamic topography, plate kinematics and paleoprecipitation rates are performed only at the exact sample localities of the thermochronology-derived thermal history models. Below, four-dimensional plots illustrate spatiotemporal trends in Central Asian upper crustal cooling histories recorded by thermal history modelling of thermochronology data viewed from the southeast (d) and northwest (e). B Basin, F Fault, FB Fergana Basin, STSS South Tian Shan Suture, MTSZ Main Tian Shan Suture Zone, TFF Talas Fergana Fault, CTUSS Charysh-Terekta-Ulagan-Sayan Suture.

The tectonic framework of Central Asia was established in the Late Paleozoic with the formation of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt40,41, which subsequently influenced Meso-Cenozoic deformation and topographic evolution17,20 (Fig. 2). By the Early Permian, northward subduction of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean began along the southern Eurasian margin as the Cimmerian blocks (e.g., Qiangtang, Lhasa) rifted off Gondwana and migrated northwards, opening the Meso-Tethys Ocean42. The Late Triassic–Early Jurassic Cimmerian Orogeny marked the accretion of these blocks and the closure of the Paleo-Tethys (Fig. 2c), reactivating Paleozoic structures and driving Central Asian crustal exhumation, particularly in the Tian Shan33,43. A prolonged tectonic quiescence followed from the Early-Middle Jurassic into the Cretaceous, characterised by widespread erosion and planation, though the precise timing remains uncertain20.

In the Early Cretaceous, the Meso-Tethys Ocean was closed with the accretion of the Lhasa Block44 (Fig. 2d), though this had minimal impact on the nearby Tian Shan, where deformation was subdued20. Meanwhile, the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean separating Siberia and Mongolia was gradually closing, with paleomagnetic and sedimentary evidence suggesting final closure in the Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous20,24,45 (Fig. 2e). This was followed by localised Late Cretaceous denudational cooling, interpreted as the onset of extension in the proto-Baikal Rift46. While orogenic collapse of the Mongol-Okhotsk Orogen has been proposed as a driver, the lack of Jurassic-Cretaceous metamorphism and coarse clastic sediments suggests minimal deformation and uplift associated with ocean closure20. Alternative mechanisms include slab rollback of the Paleo-Pacific plate47, Mongol-Okhotsk slab break-off48, and mantle upwelling49. Major Baikal Rift development did not begin until the Oligocene-Miocene, with a subsequent rapid rifting phase and relief building in the Late Pliocene46.

During the Cretaceous (~80–70 Ma), Neo-Tethys subduction along the southern Eurasian margin led to the accretion of the Karakoram Block to the Pamir region50 (Fig. 2). The Neo-Tethys ultimately closed in the Paleogene with India-Eurasia collision, though its exact timing remains debated. Some propose an early-mid Paleogene onset or ‘soft’ collision, citing a sudden convergence slowdown (Fig. S1) linked to the accretion of intra-oceanic arc systems51 (Fig. 2f). Others argue for a later ~35–34 Ma ‘hard’ collision based on the age of the youngest marine sediments, cessation of subduction-related magmatism, and thrust development52 (Fig. 2g).

Mean and standard deviation cooling rates recorded by low-temperature thermochronology in the greater Tian Shan (a) and Altai (b) regions (see Fig. 1 for sample locations), with highlighted approximate periods of major tectonism documented in the two areas and discussed in the text. Plate tectonic reconstructions24 of wider Eurasia at 220 Ma (c), 160 Ma (d), 100 Ma (e), 45 Ma (f) and 20 Ma (g) showing the evolution of seafloor age and thermochronology-derived crustal cooling rates in an orthographic projection centred on 73 °E, 37 °N. Thick black lines indicate mid-oceanic ridge, transform, or orogenic plate boundaries, while toothed purple lines indicate subduction and the subduction polarity. Arrows indicate plate velocities in the mantle reference frame. EU Eurasia, MO Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean, F Farallon Plate, IZA Izanagi Plate, PT Paleo-Tethys Ocean, MT Meso-Tethys Ocean, SB Siberia, MB Mongolian Block, LH Lhasa Block, QI Qiangtang Block, T Tarim Block, P Pamir, K Karakoram, NT Neo-Tethys Ocean, PO Pacific Plate, I Indian Plate, BR Baikal Rift, TFF Talas Fergana Fault, SF Sayan Fault.

Low-temperature thermochronology has been widely used to reconstruct Central Asia’s complex Mesozoic-to-Recent geodynamic and exhumation history20,33,53,54. These temperature-sensitive radiometric techniques rely on the retention of radiogenic daughter products as a function of time, temperature, cooling rate, and crystal chemistry55,56. The most commonly applied thermochronometers—apatite fission-track and (U-Th)/He systems—are sensitive to temperatures of ~120–60 °C and ~80–40 °C, respectively57,58, typically recording exhumation through the upper 1–5 km of the crust. The time-temperature histories these data record are then often quantified via thermal history modeling59,60.

However, interpreting Central Asian exhumation histories remains challenging due to the spatial variability of cooling rates (Fig. 1) and the limited sensitivity of thermochronology to short-wavelength topographic relief61,62. Thermal history models capturing rapid cooling (>0.5 °C/Ma, see Methods; Fig. S2) over the last 230 Ma show no clear spatial trends (Figs. S3, Videos S1–S4) and are highly localised (Fig. 1), interspersed with slower-cooling samples. The wide range in AFT ages (3–360 Ma) suggests some areas have undergone less than ~4 km of exhumation since the Late Paleozoic, with Tertiary exhumation concentrated near major faults20,33,53,54.

Consequently, various processes have been proposed to explain Central Asia’s diachronous exhumation since the Triassic, including prolonged subduction and collision along the Eurasian margin17, back-arc extension20,33,63, mantle dynamics37,38, shear zone reactivation8,33,34,35,64,65, and paleoclimate-driven denudation20,21,22,39.

In this study, we integrate thermochronology-derived cooling histories with global plate reconstructions, mantle convection models, and paleoclimate simulations, to disentangle the geodynamic and climatic drivers of key Mesozoic-Cenozoic exhumation events in Central Asia, providing new insights into the long-term evolution of continental interiors.

Results and discussion

Did dynamic topography contribute to long-term exhumation in Central Asia?

Earth’s surface topography reflects both isostatic and dynamic contributions. Isostatic topography arises from lateral variations in crustal thickness and density, while dynamic topography results from vertical stresses exerted by mantle convection66. Dynamic topography operates on longer wavelengths (500–10,000 km) and can drive transient uplift and subsidence over timescales as short as ~3 Myr67. Its amplitude scales with wavelength, typically ranging from ±1 km68 to ±2 km69 for wavelengths of 103 - 104 km.

Despite its low amplitude-to-wavelength ratio, dynamic topography can drive fluvial erosion of several kilometers to reset low-temperature thermochronology systems like apatite (U-Th)/He and fission-track70. Thermochronological studies have linked denudational cooling to dynamic topography in select regions, such as the Colorado Plateau70,71 and Patagonia72. However, this signature is absent in areas like Cenozoic East Africa, where uplift has been attributed to mantle dynamics73,74,75. This suggests that factors such as antecedent topography, uplift rate, precipitation, substrate erodibility, and isostatic effects may modulate the denudational response to dynamic topography. Regional paleogeothermal gradients further influence whether thermochronology records past mantle-driven uplift.

In Eurasia, dynamic topography has shaped surface dynamics since the Mesozoic. While episodic dynamic uplift has been proposed for Anatolia18 and eastern China19, much of Central and Eastern Asia has experienced prolonged negative dynamic topography since at least the Triassic due to sustained subduction of cold, dense oceanic slabs along the circum-Pacific and southern Eurasia margins24,38,76,77 (Fig. 3a). Today, remnants of these downwellings persist in the mid-mantle beneath southern and eastern Eurasia, linked to the subduction of the former Tethys, Izanagi, and Proto-Pacific plates77 (Fig. 2).

Spatiotemporal analysis (see Methods) of absolute and changes in dynamic topography (Fig. 3b and c and Video S5) reveals no correlation with denudational cooling trends in Central Asia. While negative dynamic topography may have contributed to localized subsidence, as proposed for some eastern Eurasian basins37,38, it does not appear to have driven Mesozoic-Cenozoic regional-scale denudation trends.

Central Asia, shown here at four key time periods (a), has remained above a long wavelength region of negative dynamic topography for the last 230 Ma. Reconstructions are shown in an orthographic projection centred on 73 °E, 37 °N. Changes in denudational cooling rates recorded by thermochronology data across Central Asia do not correlate with either dynamic topography amplitudes, which have remained negative since the Triassic (b), or changes in dynamic topography (c). Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between cooling rate and both dynamic topography (b) and change in dynamic topography (c) are 0.000 across the full dataset. Even at each individual million-year time step (d, e), r values have remained close to zero. An animation of Central Asian crustal cooling rates in relation to predicted dynamic topography and change in dynamic topography for the full 230 Ma modelling period can be found in the Supplementary Video S5.

Possible links between paleoprecipitation rates and long-term denudation?

The Permian-Triassic boundary marked the onset of widespread aridification in Central Asia25,78. While short-lived humid phases occurred locally due to topographic effects20,79,80,81, semi-arid to arid conditions have prevailed regionally to the present day25,39 (Fig. 4a). This long-term aridity reflects incremental tectonic growth of Asia, which progressively isolated Central Asia from marine moisture sources20. Further drying was amplified by Cenozoic uplift of the Himalaya, Tibetan Plateau, and Central Asian ranges (e.g., Tian Shan, Altai, Sayan, Hangay), which created extensive rain shadows82.

Despite this climatic stability since the Late Triassic (Video S6), thermochronology data reveal a highly variable, diachronous denudational cooling history (Fig. 4b). Correlation analysis dismisses paleoprecipitation changes as a primary regional-scale driver of denudational cooling over the last 230 Myr (Fig. 4c). Instead, prolonged aridity likely contributed to the preservation of late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic apatite fission-track ages, indicating low regional erosion rates despite Central Asia’s complex tectonic history21,22. While some studies have linked increased exhumation to periods of glaciation elsewhere83,84, our model does not capture glacial activity. It therefore remains feasible that in discrete areas of Central Asia glaciers contributed to denudational cooling in Central Asia as recorded by low-temperature thermochronology, particularly during Pliocene–Pleistocene Northern Hemisphere glaciation.

Paleoprecipitation rates have remained low across Central Asia since the Triassic (a), and (b) show no correlation with regional denudational cooling rates as recorded by thermochronology data (Pearson correlation coefficient [r] of 0.000 across the entire modelling space). Even when evaluated at each million year time step (c) r hovers around zero, indicating denudational cooling in Central Asia has been independent of paleoprecipitation rates for the last 230 Ma. Reconstructions in (a) are shown in an orthographic projection centred on 73 °E, 37 °N. An animation of Central Asian crustal cooling rates in relation to predicted paleoprecipitation rates for the full 230 Ma modelling period can be found in the Supplementary Material Video S6.

Reactivation of inherited crustal-scale heterogeneities

Central Asia’s Paleozoic tectonic framework strongly influenced its Mesozoic-to-recent evolution, yet constraining the timing of past fault formation and reactivation remains challenging. Fault movement is typically dated using (i) displaced strata of known age, (ii) mineral growth on fault planes, or (iii) thermochronometer resetting by frictional heating85. However, prolonged deformation often obscures evidence of older fault activity. Such is the case for Central Asia, for which much of the region’s structural history is poorly constrained86.

An alternative approach infers fault activity from 4D exhumation histories recorded by thermochronometers in fault-bounded blocks10,15,16,87. While such an approach is generally applied as case studies on individual fault systems, here we extend this method to a continental scale. Using the GEM fault database88, long faults (>10 km) near rapidly cooled basement blocks (>0.5 °C/Ma) were identified that may have accommodated differential crustal exhumation (see Methods).

Faults highlighted by this analysis align well with documented cases of Mesozoic reactivation of Paleozoic structures, such as for the Talas-Fergana, Altyn Tagh, and South Tian Shan Shear Zone8,20,33,34,64,89,90,91 (Fig. 5a). Reconstructed paleogeographic positions show these faults remained sub-parallel to the southern Eurasian margin for most of the past 230 Myr (Fig. 5 and Video S7). This favourable orientation meant that these faults could have accommodated the strain field produced by the progressive closure of the Tethys Ocean, supporting the idea that prolonged subduction and collision along the southern Eurasian margin provided the paleostress driver of Central Asian deformation for much of the Meso-Cenozoic17,20,33,92,93,94. These same structures were also sub-perpendicular to the East Asian Arc since the Early Jurassic (Fig. S4) and could therefore theoretically have also accommodated strike slip or oblique slip displacement in response to Pacific subduction dynamics. However, given its greater distance and fewer accretionary events over the last 190 Myr, the East Asian Arc likely played a minor role in Central Asian deformation compared to the dynamic and proximal Tethyan margin.

a Distribution of faults in proximity to quickly denuding crustal blocks as indicated by rapidly cooling thermochronology data, and thus potentially (re)activated at that time to accommodate differential exhumation. Rose diagrams illustrate the paleo-azimuths of those fault traces. b Mean fault azimuths of potentially (re)activated faults remain sub-parallel to the southern Eurasian arc since at least 220 Ma, indicating these brittle systems remained in a kinematically favourable orientation to enable them to intermittently accommodate significant subduction-induced strain that led to Central Asia’s secular exhumation cooling history (c). Fault traces were reconstructed to their paleogeographic position following the plate tectonic model of Zahirovic et al.24, and Tethyan arc kinematics were extracted following the approach of East et al.112 (see Methods). ATF Altyn Tagh Fault, TFF Talas Fergana Fault, BF Bolnai Fault, CTUSS Charysh-Terekta-Ulagan-Sayan Suture, STSS South Tian Shan Suture. An animation of the full 230 Ma fault paleoactivation analysis can be found in the Supplementary Material (Video S7).

Tethyan subduction dynamics controlled meso-cenozoic Central Asian exhumation

Central Asia’s long-term exhumation is often linked to Tethyan subduction along the southern Eurasian margin17,20,33. However, thermochronology data do not consistently record rapid denudational cooling coeval with major contractional events (Fig. 2). For example, the Tian Shan records little denudation during the Early Cretaceous accretion of the Lhasa Block20,44 (Fig. 1). Nor are there any apparent relationships between denudational cooling and either plate velocities or plate motion azimuths (Fig. S5), which might be expected if lithosphere-asthenosphere coupling were imparting stresses in the upper crust.

Similarly, closure of the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean in the Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous20 (Fig. 2 and Videos S8 and S9) did not trigger increased denudational cooling in Central Asia, even in the nearby Altai region (Figs. 1 & S6), consistent with the lack of regional metamorphism or crustal thickening associated with Siberia-Mongolia collision95. Instead, plate tectonic modelling reveals a complex interplay of subduction dynamics and hinterland exhumation, with rapid cooling linked to a mix of collisional events (Fig. S1 and Videos S10) and trench retreat (Fig. 6 and Video S11) along the Tethyan margin.

a Orthogonal trench retreat rates at 200, 115 and 20 Ma, showing periods of slab roll back and trench advance (negative trench retreat). Late Triassic (~230-210 Ma) and Late Jurassic-Early Cretaceous (~160-110 Ma) periods of increased upper crustal denudational cooling (b) appear to correspond to periods of trench retreat and slab roll back (red bars) (c). No apparent relationship between crustal exhumation and trench migration obliquity are apparent (d). NC North China, SC South China, PT Paleo-Tethys, MT Meso-Tethys, QI Qiangtang Block, LH Lhasa Block. An animation showing the relationship between Central Asian crustal cooling rates and southern Eurasian trench migration for the full 230 Ma model can be found in the Supplementary Material (Video S11).

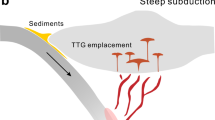

Late Triassic–Early Jurassic denudational cooling in the Tian Shan and Altai coincides with the accretion of the Qiangtang Block and the Cimmerian Orogeny along the southern Eurasian margin (Fig. 2). Some attribute this to far-field compressional stress propagation rejuvenating antecedent topography20,33,96. However, an alternative model proposes that Late Triassic back-arc basins formed in Central Asia due to Palaeo-Tethys slab rollback after collision of North and South China97 (Fig. 6a and Video S11). In either case, exhumation was likely accommodated along inherited structures17,64 (Fig. 5a). Supporting evidence for Jurassic extension accommodated by normal reactivation of preexisting faults has been documented in the Tian Shan, including in the Turfan, Tarim, and Junggar Basins20. Similar back-arc extension from Neo-Tethys rollback is also linked to the Early-Middle Jurassic formation of the Great Caucasus Trough and South Caspian Sea further afield20,98.

The subsequent Cretaceous period of rapid cooling, particularly pronounced in the Altai, also does not align with a documented period of collisional tectonics (Fig. 2). Instead, plate tectonic modelling shows the spike in hinterland denudation corresponded with prolonged slab rollback along the southern Eurasian arc (Fig. 6a), which may have resulted in back arc extension and basin margin exhumation. While contemporaneous East Asian Arc subduction (Video S12) and rollback is thought to have driven back-arc extension in eastern China99,100 (Video S13), the contrast between relatively constant trench retreat rates over the last ~100 Myr and Central Asian denudation rates which declined in the Paleogene (Fig. S7) indicate these processes were likely unrelated.

Whether Tethyan slab rollback induced sufficient deviatoric stresses to extend cold, thick lithosphere remains uncertain. However, these stresses could have reactivated well-oriented faults20,33. 4D fault analysis (Fig. 5) confirms that these structures were subparallel to the Tethyan margin, making their reactivation kinematically feasible101,102.

In the Cenozoic between 60 and 40 Ma, mean denudational cooling rates recorded by thermal history models in the Tian Shan increased to between 2 to 4.8 °C/Ma, reaching rates faster than at any point during the preceding 200 million years (Fig. 2). This coincided with a drastic slowdown in convergence rates (Fig. S1) attributed to the accretion of intra-oceanic arc systems during the onset of ‘soft’ India-Eurasia collision51. This contradicts the findings of Wang et al.54 who asserted, based on synthetic age-elevation relationships generated from spatial interpolations of regional thermochronology data, that the Tian Shan was unaffected by early India-Eurasia collision during this period. Tian Shan exhumation accelerated further after the ~35–34 Ma, a time which some argue as the onset of ‘hard’ collision between India and Eurasia52, with mean cooling rates reaching up to ~3.5 °C/Ma in the Oligocene and jumping again to nearly 5 °C/Ma by the Plio-Pleistocene. In the Altai region, by contrast, Cenozoic denudational cooling rates did not accelerate significantly until the Miocene (Fig. 2), coeval with rapid rifting and topographic growth in the Baikal Rift region46.

Holistic Earth systems approach to interpreting long-term exhumation histories

Through an integrated global modelling approach, several previously proposed geological drivers of Central Asian exhumation since the Mesozoic were tested. Results suggest that dynamic topography and paleoclimate had minimal influence on Central Asian denudation over the last 230 Myr. Instead, the Mesozoic-Cenozoic exhumation history of Central Asia was predominantly governed by alternating compression and extension linked to far-field accretion and slab rollback along the southern Eurasian margin. The resulting diachronous denudational cooling history is best preserved along inherited crustal-scale structures that accommodated differential exhumation in response to Tethyan subduction dynamics.

The open-access workflow presented here enables geoscientists, for the first time, to readily test hypotheses about the potential role of long wavelength drivers of deep time exhumation histories recorded by thermochronology. The modularity of the workflow means that users can easily test multiple plate tectonic, mantle dynamics, paleoclimate, paleotopography and fault models of their choosing, or extend the approach to other relevant data types. For instance, future studies might consider integrating source-to-sink histories (e.g., denudation, fluid and sediment flux, transport pathways, and sedimentation) predicted by landscape evolution models27 into this approach to account for potential time lags between geodynamic drivers of landscape dynamics and exhumation. While demonstrated here at a continental scale for Central Asia, the workflow is designed for global applications enabling holistic Earth system analysis of deep time surface evolution.

The paleo-fault activation analysis technique developed here also provides a novel means of using differential exhumation histories recorded by regional thermochronology datasets to identify geological structures which may have been active at particular periods in the deep past. Such an approach is of course reliant on assumptions about the validity of the thermal history models and fault database used. However, provided those assumptions hold true, this technique is one of the only ways to currently ascertain regional fault activation chronologies in deep time, and examine their spatiotemporal relationship to evolving plate margins and subduction kinematics.

Methods

Thermochronology data mining

Conducting regional to continental scale numerical interrogation of thermochronological data in conjunction with plate tectonic, dynamic topography, and paleoclimate models requires access to standardised, high-quality data and metadata stored in a machine-readable relational database. In particular, such a workflow requires a dataset that includes regional upper crustal cooling rates predicted by numerical inversions of thermochronology data over the time period of interest (230-0 Ma, in this case).

Here, we used the open access Central Asian thermochronology data compilation of Nixon et al.32, the only relational database of published thermochronology analyses from Central Asia of this kind to date. Though comprehensive, some data gaps in the compilation exist. Nevertheless, the compilation, which was completed in 2023, includes detailed geosample metadata, apatite, zircon and titanite fission-track data, apatite and zircon (U-Th)/He data, as well as best-fit and maximum and minimum 95% confidence interval time-temperature paths from thermal history models of 372 surface rock samples from across Central Asia.

Thermochronology data included in the compilation were sourced from publications (see Table S1 for full list of references) which included per-sample inverse time-temperature reconstructions that passed three criteria: (1) that the underlying thermochronology (meta-)data and inverse thermal history model parameters and results were reported and made available in line with published international data reporting best practices56 and in enough detail to extract the requisite information needed for the numerical 4D analysis described below, (2) studies with anomalous AFT dates that are not reproducible and thus contested by subsequent studies were excluded, and (3) that the published thermal history models were shown to reproduce the observed data indicating statistical robustness.

To ensure a high-quality dataset with sufficiently detailed (meta-)data for use in qualitative models undertaken here, the Nixon et al. compilation32 only includes data from peer-reviewed publications which report secondary standard results for objective assessment of data accuracy, and that ideally include single-grain results consistent with best-practice reporting standards30,55,56. Published inversely modelled best-fit and upper and lower 95% confidence interval time-temperature paths produced by the QTQt, HeFTy and AFTSolve modelling software were digitised using WebPlotDigitizer. Where available in supplementary information from data sources, model reliability metrics including goodness of fit (HeFTy) and age, length and kinetic parameter model residuals (QTQt) were also recorded. In addition to data quality requirements described above, models were only included in this compilation when modelling conditions were reported, including software, data types used, and rationale for applied constraints were reported, to prevent inclusion of thermochronologically or geologically unsupported time-temperature histories.

Non-reproducibility in fission track thermochronology can arise due to the subjective nature of the track identification process and the high degree of training required to produce reliable data103,104,105. Fission track analysis involves the manual detection of tracks in mineral grains, typically using optical microscopy, which inherently introduces variability due to observer bias, interpretation skills, and the complexity of track morphologies in natural samples. The reliability of manually acquired (rather than through computer automation) fission track data is therefore highly dependent on the operator’s experience and expertise. Instances of such discrepancies have been noted in different parts of Central Asia, where certain studies report anomalous apatite fission-track ages that are significantly younger and incompatible with those reported by the majority of studies from the same areas and, in some cases, are even younger than ages from the lower-temperature apatite (U-Th)/He system reported in the same basement blocks (see Discussions in Gillespie et al.106 and He et al.107). In these cases, the studies which reported suspect data were therefore omitted from the compilation32.

Quantifying thermal histories recorded by thermochronology data via numerical inversion has become routine practice in applied thermochronology studies. Yet, large variations exist in the manner and degree of reporting of thermal history modeling (meta-)data. To ensure statistical robustness of the compilation of inverse thermal history models that underpin the integrated continental-scale analysis, published international thermal history modelling data reporting best practices108,109 require that thermochronology studies include information to enable readers to independently judge numerical simulation quality and validity. In line with these guidelines, the compilation32 therefore only includes published time-temperature simulations from Central Asia which were shown to reproduce the underlying thermochronology data.

Cooling rates stored in the Nixon et al. data compilation32 were calculated by taking the slope of best-fit time-temperature paths from published thermal history models on a per million year basis. Only periods of cooling recorded by thermal history models, as a proxy for exhumation, were considered. Rare phases of reheating in published thermal history models from the study area were instead considered as recording 0 °C/Ma of cooling during the corresponding time periods. Extracted thermal histories for any given sample extend only as far back as the period of time constrained by their underlying thermochronology data, with cooling rates for earlier periods recorded in the database as NaN and ignored during analysis. The Nixon et al. data compilation32 is stored in the structured relational thermochronology data model of Boone et al.30 and made publicly accessible in the geospatial EarthBank platform (previously AusGeochem29). Best-fit thermal histories were then exported from EarthBank as shapefiles for ingestion into the GPlates plate tectonic modelling software23. A complete list of thermochronology data sources from the Nixon et al. compilation32 is presented in the Supplementary Information (Table S1) and accompanies the open access data compilation in EarthBank.

Of the per-million-year cooling rates extracted from best-fit thermal history models included in the Nixon et al. database32, nearly 50% are below 0.5 °C/Ma for the last 230 Ma. Approximately 30% of cooling rates are above 1.0 °C/Ma, while only ~20% are above 1.5 °C/Ma (Fig. S2). A cooling rate of 0.5 °C/Ma was determined to be the most appropriate cut-off for defining what is considered slow versus fast cooling rates for the study area. This decision was made to optimise the extraction of meaningful cooling peaks and troughs from regional thermochronology data, while minimising the obscuring effect of the more abundant background cooling (Fig. S8). It also preserves a sufficient number of fast-cooling samples to prevent increased noise from reduced analytical representation in subsequent calculations.

Nevertheless, the selection of cooling rate cut-off does not make a large difference in the spatial distribution of “fast cooling” samples through time, as seen in animations of cooling rates through time in present-day coordinates for the Tian Shan (Vid. S1), Altai (Vid. S2) and for all Central Asia (Vid. S3).

Integrating thermochronology with global Earth system models

The open-access workflow and code developed here enables analysts to integrate thermochronology datasets into existing global-scale plate tectonic, mantle dynamics and paleoclimate models for the purposes of holistically interpreting crustal cooling histories in a holistic Earth systems context. The code is designed to be flexible — applicable to user-defined time ranges and from the meso-to-global scale — and modular — with users able to apply the workflow to the plate reconstructions, mantle dynamic simulations, and paleoclimate models of their choosing, as well as incorporate other regional-to-global scale datasets, such as paleotopography models (Video S14) or fault databases (Fig. 5) (see below).

Written as a series of shell scripts and utilising the Generic Mapping Tool version 6 command library110, the workflow requires an input.csv file with the longitude and latitude of thermochronology samples and their per-million-year cooling rates recorded by thermal history modelling. Depending on the purposes of the study, additional information, such as paleotemperatures, the regions and sub-regions of samples can also be included in the input file. The workflow and scripts are publicly available via the GitHub page (see Code Availability).

Plate tectonic reconstruction of thermochronology data

The paleogeographic distribution of Central Asian thermochronology data were reconstructed back through time to 230 Ma in GPlates23 using the plate tectonic model of Zahirovic et al.24 in a mantle reference frame. These were then coupled with a global mantle dynamics model24.

Plate kinematics and subduction dynamics

To explore the potential role of plate tectonics on the long-term exhumation history of Central Asia, spatiotemporal correlation analysis was conducted on numerical time-temperature histories recorded by thermochronology data and plate-subduction kinematics extracted from the Zahirovic et al. plate reconstruction24. The plate reconstructions in Zahirovic et al.24 were focused on the eastern Tethyan region, making them the most appropriate model to use in this analysis. While slight differences in the exact reconstructed positions for certain terranes exist between the plate tectonic model used here24 and others available for the region26,111, the general plate motion motions and evolution in the wider study area predicted by each model over the last 230 Ma are largely consistent (Fig. S9).

The velocities and azimuths of plate motion, subduction, and subduction zone migration were extracted using the GPlates23 plate tectonic modelling software following the plate kinematics analysis workflow of East et al.112.

Dynamic topography

To explore the potential role of mantle dynamics in the Triassic-to-recent exhumation history of Central Asia, spatiotemporal relationships between cooling histories recorded by thermochronology data and predicted dynamic topography and changes in dynamic topography from Braz et al.76 (preferred model D10) were compared in their palinspastic context through space and time.

While a range of global dynamic topography models exist, all published dynamic topography models suggest Central Asia was experiencing a prolonged period of negative dynamic topography since 230 Ma (Fig. S10). The preferred dynamic topography model from Braz et al.76 was run using the boundary conditions of the Zahirovic et al. plate reconstruction24, making the analysis self-consistent. The Braz et al.76 work also identified a model that fit more of the geological constraints for Australia, and similar model setups (pseudo-compressible mantle flow using CitcomS) were shown to have a favourable global consistency with present-day constraints113. Instead, the range of dynamic topography models largely differ in their amplitude of dynamic topography, rather than the trends (Fig. S10) - and the trends are more important as they indicate the dynamic uplift or subsidence through time.

Paleoprecipitation

Four-dimensional relationships between exhumation cooling recorded by the reconstructed thermochronology data and paleoprecipitation rates were calculated using the global paleoclimate model of Valdes et al.25, extracted from a high complexity atmosphere-ocean Hadley Centre general circulation model (HadCM3114). The Valdes et al.25 model uses the Scotese26 PaleoMAP paleotopography as a boundary condition, capturing the effects of changing land-ocean distribution and orographic precipitation.

Structural analysis

The structural analysis conducted in this study aimed to utilise crustal exhumation cooling histories recorded by low-temperature thermochronology data to identify faults which may have been active in past geological time. To do this, faults in regional- to global-scale databases in proximity to areas that experienced cooling rates above a certain threshold were identified for every million-year model time step. The distribution and azimuths of those filtered fault traces were then analysed with respect to tectonic plate and subduction kinematics in greater Asia to assess the potential links between subduction and accretionary tectonics along the Tethyan margin and the paleostrain field of the continental interior.

Two different regional- to global-scale fault databases were used during structural analysis. The GEM global fault database of Styron and Pagani88 is a comprehensive dataset of active fault traces of seismogenic risk. The data coverage is relatively coarse and comprises very long faults. In contrast, the Active Faults of Eurasia Database86 (AFEAD) is a higher-detail continental-scale geodatabase comprising more numerous, but predominantly much shorter and more disconnected faults. Both fault databases record very similar fault trace geometries across Central Asia, predominantly trending WSW, WNW and NW (Figs. S11–S13). While both represent extremely useful datasets, the faults are limited to two-dimensional polylines, with no information about the three-dimensional geometries of these faults at depth. Nor is there information about the ages of these brittle structures. Therefore, due to limitations in available regional-scale fault databases, the structural analysis conducted here is best considered as exploratory. Faults identified as potentially active in the past would warrant further detailed structural and geochronological analyses to confirm if and when these faults may have accommodated strain in the past. Nevertheless, the close geometric relationship between potentially active faults and the northern Tethyan subduction zones throughout the last 230 Ma is notable and suggests a genetic link between subduction dynamics and strain history.

Parameterisation analysis (Figs. S11–13) shows that neither the selection of proximity buffer (5, 10 or 25 km) of fault database (GEM88 or AFEAD86) makes significant difference in the resulting mean azimuths or regional spatial distribution of filtered faults deemed close to fast cooling thermochronology samples. Similarly, the choice in “fast cooling” rate cut-off (0.5, 1.0 or 1.5 °C/Ma) does not significantly affect the orientations of filtered faults from either fault database (Figs. S14–S19).

Given the continental-scale nature of the study and its focus on potential long-wavelength drivers of deep-time exhumation histories, the GEM database88 was preferred and used for all subsequent analysis and interpretation discussed in the text. This is because it comprises generally larger crustal-scale faults, more likely to be long-lived and pre-existing during a greater proportion of the modelling time frame. Given the enormous sizes (tens-to-hundreds of kms) of many of the Paleozoic-early Mesozoic structures that have been documented to play a critical role in accommodating subsequent strain and exhumation20,33,34,64,90 and that three-dimensional strain envelopes of faults scales with fault length115, a proximity buffer of 10 km was chosen for the fault analysis. This was to ensure the capture of both moderate (tens of kms in length) and very large ( > 100 km long) fault systems capable of producing multiple kilometres of exhumation of footwalls and hanging walls during normal and reverse displacement, respectively.

Data availability

All thermochronology data and thermal history models used in this study32 are publicly available via the geospatial EarthBank platform29,30,31 https://doi.org/10.58024/AGUA6E7B32B9.

Code availability

The computational codes used for the plate-tectonic modelling and thermochronology analysis can be freely accessed by the ThermoPlates GitHub repository: https://github.com/samuelcboone/ThermoPlates.

References

Murray, K. E., Braun, J. & Reiners, P. W. Toward robust interpretation of low-temperature thermochronometers in magmatic terranes. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 3739–3763 (2018).

Ehlers, T. A. Crustal thermal processes and the interpretation of thermochronometer data. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 58, 315–350 (2005).

Gunnell, Y., Gallagher, K., Carter, A., Widdowson, M. & Hurford, A. J. Denudation history of the continental margin of western peninsular India since the early Mesozoic - reconciling apatite fission-track data with geomorphology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 215, 187–201 (2003).

Reiners, P. W., Thomson, S. N., McPhillips, D., Donelick, R. A. & Roering, J. J. Wildfire thermochronology and the fate and transport of apatite in hillslope and fluvial environments. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JF000759 (2007).

Whipp, D. M. Jr. & Ehlers, T. A. Influence of groundwater flow on thermochronometer-derived exhumation rates in the central Nepalese Himalaya. Geology 35, 851–854 (2007).

Seiler, C., Gleadow, A. J. W., Fletcher, J. M. & Kohn, B. P. Thermal evolution of a sheared continental margin: insights from the Ballenas transform in Baja California, Mexico. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 285, 61–74 (2009).

Boone, S. C., Seiler, C., Reid, A. J., Kohn, B. & Gleadow, A. An Upper Cretaceous paleo-aquifer system in the Eromanga Basin of the central Gawler Craton, South Australia: evidence from apatite fission track thermochronology. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 63, 315–331 (2016).

Glorie, S. et al. Tectonic history of the Kyrgyz South Tien Shan (Atbashi-Inylchek) suture zone: the role of inherited structures during deformation-propagation. Tectonics, 30 (2011).

Stockli, D. F. Application of low-temperature thermochronometry to extensional tectonic settings. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 58, 411–448 (2005).

Foster, D. A. Fission-track thermochronology in structural geology and tectonic studies. In: Fission-Track Thermochronology and its Application to Geology. pp. 211–220 (Springer, 2019).

Jolivet, M. et al. Mesozoic and Cenozoic tectonics of the northern edge of the Tibetan plateau: fission-track constraints. Tectonophysics 343, 111–134 (2001).

Brichau, S. et al. Constraining the long-term evolution of the slip rate for a major extensional fault system in the central Aegean, Greece, using thermochronology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 241, 293–306 (2006).

Sobel, E. R., Oskin, M., Burbank, D. & Mikolaichuk, A. Exhumation of basement-cored uplifts: Example of the Kyrgyz Range quantified with apatite fission track thermochronology. Tectonics, 25 (2006).

Curry, M. A., Barnes, J. B. & Colgan, J. P. Testing fault growth models with low-temperature thermochronology in the northwest Basin and Range, USA. Tectonics 35, 2467–2492 (2016).

Boone, S. C. et al. Tectonothermal evolution of the broadly rifted zone, Ethiopian Rift. Tectonics 38, 1070–1100 (2019).

McMillan, M., Boone, S. C., Chindandali, P., Kohn, B. & Gleadow, A. 4D fault evolution revealed by footwall exhumation modelling: A natural experiment in the Malawi rift. J. Struct. Geol. 187, 105196 (2024).

De Grave, J., Buslov, M. M. & Van den haute, P. Distant effects of India-Eurasia convergence and Mesozoic intracontinental deformation in Central Asia: constraints from apatite fission-track thermochronology. J. Asian Earth Sci. 29, 188–204 (2007).

Komut, T. High surface topography related to upper mantle flow beneath Eastern Anatolia. Geophys. J. Int. 203, 1263–1273 (2015).

Brown, H., Colli, L. & Bunge, H. P. Asthenospheric flow through the Izanagi-Pacific slab window and its influence on dynamic topography and intraplate volcanism in East Asia. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 889907 (2022).

Jolivet, M. Mesozoic tectonic and topographic evolution of Central Asia and Tibet: a preliminary synthesis. In: Brunet, M., McCann, T., and Sobel, E. (Eds.) Geological Evolution of Central Asian Basins and the Western Tien Shan Range. (Geological Society, 2017).

Pullen, A., Banaszynski, M., Kapp, P., Thomson, S. N. & Cai, F. A mid-Cretaceous change from fast to slow Exhumation of the Western Chinese Altai mountains: A climate driven Exhumation signal?. J. Asian Earth Sci. 197, 104387 (2020).

Jepson, G. et al. Climate as the great equalizer of continental-scale erosion. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL095008 (2021).

Müller, R. D. et al. GPlates: building a virtual earth through deep time. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 2243–2261 (2018a).

Zahirovic, S. et al. Tectonic evolution and deep mantle structure of the eastern Tethys since the latest Jurassic. Earth-Sci. Rev., 293–337 (2016).

Valdes, P. J., Scotese, C. R. & Lunt, D. J. Deep ocean temperatures through time. Climate v. 17, 1483–1506 (2021).

Scotese, C. R. PALEOMAP PaleoAtlas for GPlates and the PaleoData Plotter Program. P. Project. http://www.earthbyte.org/paleomap-paleoatlas-for-gplates/ (2016).

Salles, T. et al. Hundred million years of landscape dynamics from catchment to global scale. Science 379, 918–923 (2023).

Boone, S. C., Balestrieri, M. L. & Kohn, B. Thermo-tectonic imaging of the Gulf of Aden-Red Sea rift systems and Afro-Arabian hinterland. Earth-Sci. Rev. 222, 103824 (2021).

Boone, S. C. et al. AusGeochem: an open platform for geochemical data preservation, dissemination and synthesis. Geostand. Geoanal Res. 46, 245–259 (2022).

Boone, S. C. et al. A geospatial platform for the tectonic interpretation of low-temperature thermochronology Big Data. Sci. Rep. 13, 8581 (2023).

Nixon, A. L. et al. Volcanoes to vugs: Demonstrating a FAIR geochemistry framework with a diverse application of major and trace element data through the AuScope EarthBank platform. Chem. Geol. 696, 123092 (2025).

Nixon, A., Boone, S., Meeuws, F., Kohlmann, F. & Glorie, S. Central Asia thermochronology compilation. [Dataset]. AuScope EarthBank Platf. https://doi.org/10.58024/AGUA6E7B32B9 (2025).

Glorie, S. & De Grave, J. Exhuming the Meso–Cenozoic Kyrgyz Tianshan and Siberian Altai-Sayan: a review based on low-temperature thermochronology. Geosci. Front. 7, 155–170 (2016).

Sobel, E. R., Arnaud, N. O., Jolivet, M., Ritts, B. D. & Brunel, M. Jurassic to Cenozoic exhumation history of the Altyn Tagh range, NW China, constrained by 40Ar/39Ar and apatite fission track thermochronology. In: Hendrix, M. S. & Davis, G. A. (eds) Paleozoic and Mesozoic Tectonic Evolution of Central Asia: From Continental Assembly to Intracontinental Deformation. (Geological Society of America, 2001).

Glorie, S. et al. Structural control on Meso-Cenozoic tectonic reactivation and denudation in the Siberian Altai: insights from multi-method thermochronometry. Tectonophysics 544, 75–92 (2012).

Glorie, S. et al. Meso-cenozoic tectonic history of the Altai: new insights from apatite U-Pb and fission track thermochronology for the Fuyun area (Xinjiang, China). Tectonics 42, e2022TC007692 (2023).

Xie, X., Müller, R. D., Li, S., Gong, Z. & Steinberger, B. Origin of anomalous subsidence along the Northern South China Sea margin and its relationship to dynamic topography. Mar. Pet. Geol. 23, 745–765 (2006).

Cao, X., Flament, N., Müller, D. & Li, S. The dynamic topography of eastern China since the latest Jurassic Period. Tectonics 37, 1274–1291 (2018).

Jiang, X. et al. Late Cretaceous aeolian dunes and reconstruction of paleo-wind belts of the Xinjiang Basin, Jiangxi Province, China. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 257, 58–66 (2008).

Windley, B. F., Alexeiev, D., Xiao, W., Kröner, A. & Badarch, G. Tectonic models for accretion of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Geol. Soc. 164, 31–47 (2007).

Wilhem, C., Windley, B. F. & Stampfli, G. M. The Altaids of Central Asia: a tectonic and evolutionary innovative review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 113, 303–341 (2012).

Roger, F., Jolivet, M. & Malavieille, J. The tectonic evolution of the Songpan Garzeˆ (North Tibet) and adjacent areas from Proterozoic to Present: a synthesis. J. Asian Earth Sci. 39, 254–269 (2010).

De Grave, J. et al. Thermo-tectonic history of the Issyk-Kul basement (Kyrgyz northern Tien Shan, central Asia). Gondwana Res. 23, 998–1020 (2013).

Coward, M. P., Kidd, W. S. F., Pan, Y., Shackleton, R. M. & Zhang, H. The structure of the 1985 Tibet Geotraverse, Lhasa to Golmud. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., Lond., Ser. A: Math. Phys. Sci. 327, 307–336 (1988).

Metelkin, D. V., Gordienko, I. V. & Klimuk, V. S. Paleomagnetism of Upper Jurassic basalts from Transbaikalia: new data on the time of closure of the Mongol–Okhotsk Ocean and Mesozoic intraplate tectonics of Central Asia. Russian Geol. Geophys. 48, 825–834 (2007).

Jolivet, M. et al. How old is the Baikal Rift Zone? Insight from apatite fission track thermochronology. Tectonics 28, TC3008 (2009).

Traynor, J. J. & Sladen, C. Tectonic and stratigraphic evolution of the Mongolian People’s Republic and its influence on hydrocarbon geology and potential. Mar. Pet. Geol. 12, 35–52 (1995).

Meng, Q.-R. What drove late Mesozoic extension of the northern China–Mongolia tract?. Tectonophysics 369, 155–174 (2003).

Wang, B. et al. Late Paleozoic tectonic evolution of the northern West Tian Shan, NW China. Geodyn Acta 19, 237–247 (2006).

Schwab, M. et al. Assembly of the Pamirs: Age and origin of magmatic belts from the southern Tien Shan to the southern Pamirs and their relation to Tibet. Tectonics 23 (2004).

van Hinsbergen, D. J. et al. Greater India Basin hypothesis and a two-stage Cenozoic collision between India and Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 7659–7664 (2012).

Aitchison, J. C., Ali, J. R. & Davis, A. M. When and where did India and Asia collide? J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth, 112 (2007).

Jolivet, M. Application of low-temperature thermochronology to the dating and quantification of tectonic movements: The example of Asia. Chapter 5 in Jolivet, M. (Eds.) Fission-track Thermochronology: Methodology and Applications to Geology. (John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2024).

Wang, Y., Zhang, J., Huang, X. & Wang, Z. Cenozoic exhumation of the Tianshan as constrained by regional low-temperature thermochronology. Earth-Sci. Rev. 237, 104325 (2023).

Flowers, R. M. et al. U-Th)/He chronology: Part 1. Data, uncertainty, and reporting. Bulletin 135, 104–136 (2023).

Kohn, B. P. et al. Interpreting and reporting fission-track chronological data. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 136, 3891–3920 (2024).

Gleadow, A. J. W. & Duddy, I. R. A natural long-term track annealing experiment for apatite. Nucl. Tracks 5, 169–174 (1981).

Wolf, R. A., Farley, K. A. & Kass, D. M. Modeling of the temperature sensitivity of the apatite (U–Th)/He thermochronometer. Chem. Geol. 148, 105–114 (1998).

Gallagher, K. Transdimensional inverse thermal history modeling for quantitative thermochronology. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth, 117 (2012).

Ketcham, R. A. Thermal history inversion from thermochronometric data and complementary information: New methods and recommended practices. Chem. Geol. 653, 122042 (2024).

Braun, J., Van der Beek, P. & Batt, G. Quantitative Thermochronology: Numerical Methods for the Interpretation of Thermochronological Data (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Fox, M., Herman, F., Willett, S. D. & May, D. A. A linear inversion method to infer exhumation rates in space and time from thermochronometric data. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2, 47–65 (2014).

Glorie, S. et al. Thermo-tectonic history of the Junggar Alatau within the Central Asian Orogenic Belt (SE Kazakhstan, NW China): Insights from integrated apatite U/Pb, fission track and (U–Th)/He thermochronology. Geosci. Front. 10, 2153–2166 (2019).

Jolivet, M. et al. Mesozoic and Cenozoic tectonic history of the Central Chinese Tian Shan: reactivated tectonic structures and active deformation. Tectonics 29, TC6019 (2010).

Gillespie, J. et al. Mesozoic reactivation of the Beishan, southern Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Insights from low-temperature thermochronology. Gondwana Res. 43, 107–122 (2017).

Forte, A. M. & Rowley, D. B. Earth’s isostatic and dynamic topography—A critical perspective. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 23, e2021GC009740 (2022).

Hoggard, M., Austermann, J., Randel, C. & Stephenson, S. Observational estimates of dynamic topography through space and time. In: Mantle Convection and Surface Expressions (American Geophysical Union, 2021).

Gvirtzman, Z., Faccenna, C. & Becker, T. W. Isostasy, flexure, and dynamic topography. Tectonophysics 683, 255–271 (2016).

Hoggard, M. J., White, N. & Al-Attar, D. Global dynamic topography observations reveal limited influence of large-scale mantle flow. Nat. Geosci. 9, 456–463 (2016).

Braun, J., Robert, X. & Simon-Labric, T. Eroding dynamic topography. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1494–1499 (2013).

Liu, L. The ups and downs of North America: Evaluating the role of mantle dynamic topography since the Mesozoic. Rev. Geophys. 53, 1022–1049 (2015).

Guillaume, B. et al. Dynamic topography control on Patagonian relief evolution as inferred from low temperature thermochronology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 364, 157–167 (2013).

Moucha, R. & Forte, A. M. Changes in African topography driven by mantle convection. Nat. Geosci. 4, 707–712 (2011).

Pik, R. East Africa on the rise. Nat. Geosci. 4, 660–661 (2011).

Boone, S. C. et al. 2025. Phanerozoic thermochronology record of Afro-Arabia through space and time. Sci. Data 12, 444 (2025).

Braz, C. et al. Modelling the role of dynamic topography and eustasy in the evolution of the Great Artesian Basin. Basin Res. 33, 3378–3405 (2021).

Rubey, M. et al. Global patterns in Earth’s dynamic topography since the Jurassic: The role of subducted slabs. Solid Earth 8, 899–919 (2017).

Davies, C., Allen, M. B., Buslov, M. M. & Safonova, I. Deposition in the Kuznetsk basin, Siberia: insights into the Permian–Triassic transition and the Mesozoic evolution of Central Asia. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 295, 307–322 (2010).

Tang, F. et al. Biostratigraphy and palaeoenvironment of the dinosaur-bearing sediments in Lower Cretaceous of Mazongshan area, Gansu Province, China. Cretac. Res. 22, 115–129 (2001).

Saiki, K. & Okubo, A. Lower Cretaceous flora of the Choyr Basin, Mongolia. Cretac. Res. 27, 252–261 (2006).

Li, X. et al. Climatic and environmental indications of carbon and oxygen isotopes from the Lower Cretaceous calcrete and lacustrine carbonates in Southeast and Northwest China. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 385, 171–189 (2013).

Caves, J. K., Sjostrom, D. J., Mix, H. T., Winnick, M. J. & Chamberlain, C. P. Aridification of Central Asia and uplift of the Altai and Hangay Mountains, Mongolia: Stable isotope evidence. Am. J. Sci. 31, 1171–1201 (2014).

Herman, F. et al. Worldwide acceleration of mountain erosion under a cooling climate. Nature 504, 423–426 (2013).

Herman, F., De Doncker, F., Delaney, I., Prasicek, G. & Koppes, M. The impact of glaciers on mountain erosion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 422–435 (2021).

Tsukamoto, S., Tagami, T. & Zwingmann, H. Direct dating of fault movement. In Understanding Faults 257–282. (Elsevier, 2020).

Zelenin, E., Bachmanov, D., Garipova, S., Trifonov, V. & Kozhurin, A. The database of the active faults of Eurasia (AFEAD): Ontology and design behind the continental-scale dataset. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2021, 1–20 (2021).

Hall, J. W. et al. An apatite U–Pb thermal history map for the northern Gawler Craton, South Australia. Geosci. Front. 9, 1293–1308 (2018).

Styron, R. & Pagani, M. The GEM global active faults database. Earthq. Spectra 36, 160–180 (2020).

De Grave, J. et al. Late Palaeozoic and Meso-Cenozoic tectonic evolution of the southern Kyrgyz Tien Shan: Constraints from multi-method thermochronology in the Trans-Alai, Turkestan-Alai segment and the southeastern Ferghana Basin. J. Asian Earth Sci. 44, 149–168 (2012).

Cheng, F. et al. Lateral extrusion along the Altyn Tagh Fault, Qilian Shan (NE Tibet): insight from a 3D crustal budget. Terra Nova 27, 416–425 (2015).

Nachtergaele, S. et al. Meso-Cenozoic tectonic evolution of the Talas-Fergana region of the Kyrgyz Tien Shan revealed by low-temperature basement and detrital thermochronology. Geosci. Front. 9, 1495–1514 (2018).

Tapponnier, P., Peltzer, G. L. D. A. Y., Le Dain, A. Y., Armijo, R. & Cobbold, P. Propagating extrusion tectonics in Asia: New insights from simple experiments with plasticine. Geology 10, 611–616 (1982).

Allégre, C. O. et al. Structure and evolution of the Himalaya–Tibet orogenic belt. Nature 307, 17–22 (1984).

Peltzer, G. & Tapponnier, P. Formation and evolution of strike-slip faults, rifts, and basins during the India-Asia collision: An experimental approach. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 93, 15085–15117 (1988).

Jolivet, M. et al. Accommodating large-scale intracontinental extension and compression in a single stress-field: a key example from the Baikal Rift System. Gondwana Res. 24, 918–935 (2013b).

Dumitru, T. A., Zhou, D., Chang, E. Z. & Graham, S. A. Uplift, exhumation, and deformation in the Chinese Tian Shan, in Paleozoic and Mesozoic Tectonic Evolution of Central Asia: From Continental Assembly to Intracontinental Deformation. Mem. Geol. Soc. Am. 194, 71–99 (2001).

Pullen, A., Kapp, P., Gerhels, G., Vervoot, J. D. & Ding, L. Triassic continental subduction in central Tibet and Mediterranean-style closure of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean. Geology 36, 351–354 (2008).

Brunet, M.-F., Korotaev, M. V., Ershov, A. V. & Nishikin, A. M. The South Caspian Basin: a review of its evolution from subsidence modelling. Sediment. Geol. 156, 119–148 (2003).

Liu, L., Xu, X. & Xia, Y. Asynchronizing paleo-Pacific slab rollback beneath SE China: Insights from the episodic Late Mesozoic volcanism. Gondwana Res. 37, 397–407 (2016).

Liu, S. et al. Craton deformation from flat-slab subduction and rollback. Nat. Geosci. 17, 936–943 (2024).

Molnar, P. & Tapponnier, P. Cenozoic Tectonics of Asia: effects of a continental collision: features of recent continental tectonics in asia can be interpreted as results of the India-Eurasia collision. science 189, 419–426 (1975).

Tapponnier, P. & Molnar, P. Active faulting and Cenozoic tectonics of the Tien Shan, Mongolia, and Baykal regions. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 84, 3425–3459 (1979).

Miller, D. S., Eby, N., McCorkell, R., Rosenberg, P. E. & Suzuki, M. Results of interlaboratory comparison of fission track ages for the 1988 fission track workshop. Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instrum. Part D. Nucl. Tracks Radiat. Meas. 17, 237–245 (1990).

Tamer, M., Chung, L., Ketcham, R. & Gleadow, A. Inter-analyst comparison and reproducibility of apatite fission track analysis. Authorea Preprints, (2022).

Tamer, M. T., Chung, L., Ketcham, R. A. & Gleadow, A. J. The need for fission track data transparency. Geochronology 7, 45–58 (2025).

Gillespie, J., Glorie, S., Jepson, G., Xiao, W. & Collins, A. S. Late Paleozoic exhumation of the West Junggar Mountains, NW China. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 125, e2019JB018013 (2020).

He, Z. et al. A re-evaluation of the Meso-Cenozoic thermo-tectonic evolution of Bogda Shan (Tian Shan, NW China) based on new basement and detrital apatite fission track thermochronology. Int. Geol. Rev. 65, 2093–2112 (2023).

Flowers, R. M., Farley, K. A. & Ketcham, R. A. A reporting protocol for thermochronologic modeling illustrated with data from the Grand Canyon. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 432, 425–435 (2015).

Gallagher, K. Comment on’A reporting protocol for thermochronologic modeling illustrated with data from the Grand Canyon’by Flowers, Farley and Ketcham. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 441, 211–212 (2016).

Wessel, P. et al. The generic mapping tools version 6. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 5556–5564 (2019).

Torsvik, T. H., Müller, R. D., Van der Voo, R., Steinberger, B. & Gaina, C. Global plate motion frames: toward a unified model. Rev. Geophys. 46 (2008).

East, M., Müller, R. D., Williams, S. E., Zahirovic, S. & Heine, C. Subduction history reveals Cretaceous slab superflux as a possible cause for the mid-Cretaceous plume pulse and superswell events. Gondwana Res. v. 79, 125–139 (2020).

Müller, R. D., Hassan, R., Gurnis, M., Flament, N. & Williams, S. E. Dynamic topography of passive continental margins and their hinterlands since the Cretaceous. Gondwana Res. 53, 225–251 (2018). PagesISSN 1342-937X.

Valdes, P. J. et al. The BRIDGE HadCM3 family of climate models: HadCM3@Bristol v1.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 3715–3743 (2017).

Kim, Y. S. & Sanderson, D. J. The relationship between displacement and length of faults: a review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 68, 317–334 (2005).

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work, including the postdoctoral salary of SCB, was funded through the ARC Future Fellowship of SG (FT210100906). SZ was supported by Australian Research Council grant DE210100084 and a University of Sydney Robinson Fellowship. GPlates development is funded by the AuScope National Collaborative Research Infrastructure System (NCRIS) program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Samuel C Boone – Project design and conceptualization; programming; analysis; interpretation; manuscript writing; manuscript editing. Stijn Glorie – Project design and conceptualization; interpretation; manuscript editing. Sabin Zahirovic - Project design and conceptualization; programming; interpretation; manuscript editing. Angus Nixon - Data cleaning and compilation; interpretation; manuscript editing. Fun Meeuws – Data cleaning and compilation; manuscript editing. Fabian Kohlmann - Data cleaning and compilation; manuscript editing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Edward Sobel and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Maria Laura Balestrieri, Alireza Bahadori, and Aliénor Lavergne. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

43247_2025_3005_MOESM4_ESM.mp4

Video S1. Spatiotemporal trends in upper crustal cooling across Central Asia over the last 230 Ma as recorded by low-temperature thermochronology.

43247_2025_3005_MOESM8_ESM.mp4

Video S5. Animation of Central Asian cooling rates through time relative to predicted dynamic topography and change in dynamic topography from the mantle convection model of Braz et al. (2021).

43247_2025_3005_MOESM9_ESM.mp4

Video S6. Animation of Central Asian cooling rates through time relative to paleoprecipiation rates from the paleoclimate model of Valdes et al. (2021) over the last 230 Ma.

43247_2025_3005_MOESM10_ESM.mp4

Video S7. Animation of fault paleoactivation analysis for Central Asia for the last 230 Ma using the GEM global fault database (Styron and Pagani, 2020).

43247_2025_3005_MOESM11_ESM.mp4

Video S8. Animation showing the relationship between Central Asian crustal cooling rates and Mongol-Okhotsk convergence rates between 230 Ma and ocean closure at 130 Ma.

43247_2025_3005_MOESM12_ESM.mp4

Video S9. Animation showing the relationship between Central Asian crustal cooling rates and Mongol-Okhotsk trench migration between 230 Ma and ocean closure at 130 Ma.

43247_2025_3005_MOESM13_ESM.mp4

Video S10. Animation showing the relationship between Central Asian crustal cooling rates and southern Eurasian convergence rates since 230 Ma.

43247_2025_3005_MOESM14_ESM.mp4

Video S11. Animation showing the relationship between Central Asian crustal cooling rates and southern Eurasian trench migration since 230 Ma.

43247_2025_3005_MOESM17_ESM.mp4

Video S14. Animation showing the spatial relationship between Central Asian crustal cooling rates and the paleotopography model of Cao et al. (2017) since 230 Ma.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boone, S.C., Glorie, S., Zahirovic, S. et al. Deciphering mantle, tectonic and climatic drivers of exhumation. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1015 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03005-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03005-6