Abstract

East Antarctic coastal polynyas—semi-permanent areas of ice-free ocean—are vital for sea ice production, Antarctic Bottom Water formation, and global heat redistribution. The Dibble Polynya has pronounced sea-ice production, yet the shelf water properties there and its offshore influence have been unclear. Here we show Dense Shelf Water outflow from the polynya that ventilates a lighter variety of local bottom water. Hydrographic records suggest Dense Shelf Water formation has persisted for 50 years, consistent with satellite-derived sea-ice production since the 1990s. Since the 2010s, the downstream cross-slope salinity gradient within bottom water has weakened and the Antarctic Slope Front has been modified, following a sharp decline in sea-ice production in the neighbouring Mertz Polynya after 2010 icescape changes. We infer that reduced denser Antarctic Bottom Water formation upstream weakens the slope current barrier, promoting outflow of not-so-dense shelf water from the Dibble Polynya that efficiently ventilates the abyssal basin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

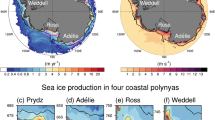

Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) is a key component of the global meridional overturning circulation, playing a crucial role in ventilating the abyssal ocean and redistributing heat and carbon within the climate system. AABW forms when Dense Shelf Water (DSW) in Antarctic coastal polynyas, where sea ice production drives brine rejection, cascades down the continental slope and mixes with surrounding water masses1,2. The East Antarctic margin hosts several coastal polynyas sustained by vigorous offshore winds, some of which significantly contribute to AABW formation3,4,5,6. Figure 1a summarises the East Antarctic coastal polynyas, based on annual sea ice production derived from satellite remote sensing7. The Dibble Polynya, located around 134°E off the Wilkes Land, has sustained substantial sea ice production of more than 5×1010 m3 yr−18,9. This amount is comparable to the Terra Nova Bay Polynya in the Ross Sea, which produces high salinity shelf water sufficiently dense to form AABW10. However, the Dibble Polynya’s specific role in local AABW formation has remained unexplored.

a Annual sea ice production (m year−1) along the East Antarctic coast. Major coastal polynyas are labelled. b Annual mean bottom temperature (°C) and the extent of DSW defined as annual mean σθ of 27.79 kg m−3 for water colder than −1.5 °C (green contour; see Methods for the rationale of using potential density), derived from the Southern Ocean Monthly Climatology21. White arrows depict generalised pathways of Cape Darnley Bottom Water (CDBW), Adélie Land Bottom Water (ALBW), and Ross Sea Bottom Water (RSBW). Not-so-dense shelf water is found near the Shackleton, Vincennes, and Dibble Polynyas. c The Dibble Polynya region. Black rectangle delineates the “area of interest” for hydrographic sampling. Coloured markers represent station locations, with colours corresponding to the legend in (d). In (a)–(c), ice shelves and landfast sea ice62 and the 1000, 2000, and 3000 m isobaths (white contours)63 are shown. d Neutral density–dissolved oxygen (µmol kg−1) plot for hydrographic data collected within the area of interest. Data points are coloured according to the survey year and cruise identifier: 2024 (IN2024V01, blue), 2019 (KY1804, orange), 2018 (IN2018V01, green), 1996 (AR9604, red), 2015 (NBP1503, purple), 1980s (Soviet Union, brown), 1960s-70s (Eltanin, pink), and 1950s (Soviet Union, dark grey). Lines connect sequential profiles of bottle data. Light grey markers are the CCHDO (CLIVAR and Carbon Hydrographic Data Office) data from the ALBW source region with bottom depth deeper than 1500 m, presenting oxygenated water generally denser than 28.30 kg m−3.

In the Australian-Antarctic Basin, where water exported from the Dibble Polynya accumulates, AABW is typically classified into two distinct volumetric modes11,12,13,14: (1) Adélie Land Bottom Water (ALBW), which originates from the Adélie Coast (143–148°E), and (2) Ross Sea Bottom Water (RSBW), sourced from the Ross Sea continental shelf (Fig. 1b). ALBW is exported from the Mertz Polynya4,15,16, forming a fresh and oxygen-rich variety of local AABW. In contrast, RSBW is saltier and less oxygenated, reflecting its more distant formation site to the east17. Exported AABW from the formation sites is advected westward by the Antarctic Slope Current (ASC)18,19,20. In addition to ALBW and RSBW, the presence of “not-so-dense shelf water” ventilating a lighter variety of AABW has been reported21. This not-so-dense shelf water (with potential density σθ slightly higher than 27.79 kg m−3) is observed near the Shackleton, Vincennes, and Dibble Polynyas (Fig. 1b) in an observation-based annual climatology22. In recent years, DSW formation in Vincennes and Shackleton—two of the three mid-sized polynyas—has been suppressed by the onshore intrusion of warm deep water6,23,24.

Globally, AABW is warming and shrinking25,26. In the Australian-Antarctic Basin, previous studies have revealed that the volume of AABW has significantly reduced over the past several decades20,27,28,29,30. This change might be related to the reduction in upstream RSBW formation due to the West Antarctic melt31, the reduction in ALBW due to the collapse of Mertz Glacier Tongue bounded to the Mertz Polynya32,33,34, and frontal shifts of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current20,29,35,36. Understanding the impacts of the observed AABW changes on the global meridional overturning circulation—beyond changes in the volume transport of the densest waters30—requires investigating the role of less-dense AABW formation (with neutral density γn lighter than ~28.30 kg m−3), which is not necessarily constrained by the conventional definition of AABW (γn > 28.27 kg m−3).

Concurrently with the reduction of the densest waters, an increase in dissolved oxygen in local AABW has been reported20,27,33. This increase is particularly evident in a lighter variety of AABW (γn < 28.3 kg m−3), suggesting a shoaling of the ventilated layer29. Shallower ventilation can make newly formed AABW more readily available for vertical mixing into warmer deep waters37, potentially shortening the turnover time of AABW in the global abyss38. However, the cause of the oxygen increase remains unclear. One possibility is continued ventilation at the formation site with reduced shelf water density27,33,34. Another possibility is an overlooked source of AABW outside the four major formation sites (Weddell, Ross, Adélie, and Cape Darnley), which may have supplied the oxygen in the lighter density class as the fraction of denser AABW has declined. Within this context, the Dibble Polynya emerges as a potential candidate.

This study provides observational evidence of DSW outflow from the Dibble Polynya, which ventilates a lighter variety of local AABW. We present direct evidence from highest accuracy ship-based hydrography during the 2024 austral summer (Fig. 1d) of unprecedented highly oxygenated water in the upper AABW density class (28.20–28.35 kg m−3 γn) with an accuracy of 1% (see Methods). The main purpose of the analysis is to unravel: “Why was the prominent signal of local AABW formation observed off the Dibble Polynya in 2024?” Historical ocean records suggest that DSW formation in the Dibble Polynya has persisted for more than 50 years, supported by the steady satellite-derived sea ice production—although a clear signal of its outflow has only been recorded in recent years. In seeking the cause of the prominent DSW outflow observed in the 2024 summer, potential influences of the Mertz Glacier Tongue calving in 201032,34,39 are discussed, where reduction in denser AABW upstream and subsequent weakening of the ASC’s barrier appearing to have advantaged recent DSW outflows from the Dibble Polynya.

Results

Dense Shelf Water outflow from the Dibble polynya

Previous studies did not report any DSW outflow from the Dibble Polynya18,20 due to the absence of a newly ventilated signal in nearby hydrographic data. In contrast, a section made in January 2024 captured significantly oxygen-rich water (240–270 μmol kg−1) near the bottom, with a bottom density of 28.36 kg m−3 γn observed at the southernmost station around the 1000 m seafloor depth (Fig. 1d), a value that stands out among historical observations within the “area of interest” near the polynya (Fig. 1c; see Methods for the box definition). The 2024 observation is also prominently fresh, as seen in the salinity–temperature space (Fig. 2a) and the cross-slope salinity section (Fig. 2c). Although its relation to local AABW thickness is not immediately clear, the isopycnal of 28.27 kg m⁻³ γn shoals to ~500 m around the 1500 m slope depth in 2024, noticeably shallower than in 1996, 2018, and 2019 summers (Fig. 2c). In addition, the local signature of DSW outflow in salinity and oxygen is stronger than in the ALBW source region near the eastern Mertz Polynya (along 140°E) during the same 2024 cruise (Supplementary Fig. 1) and found in a lighter density class than typical ALBW sourced from the Mertz Polynya (Fig. 1d). These observations suggest that the signature of DSW outflow observed in 2024 originates from the Dibble Polynya.

a Absolute Salinity–Conservative Temperature plot for bottom-100m averaged historical data. Colours distinguish data sources: CCHDO (blue circles), Ship (orange circles), Argo (magenta circles), MEOP (green diamonds), data from 2011 to 2024 (black edge colour), and historical data from the Mertz region (light grey markers). Solid curves are neutral density (γn; 28.27, 28.30 kg m⁻³) and dashed curves are potential density (σ₀; 27.79, 27.83, 27.87 kg m⁻³) isopycnal, and dotted line is surface freezing temperature. b Map of station locations for data shown in (a), with symbols and colours corresponding to the data type. Isobaths, the area of interest, and sea ice production are shown as in Fig. 1c. c Cross-slope sections of Absolute Salinity (g kg−1; colour shading) for CCHDO repeated years: 1996, 2019 (in 128 °E), 2018, and 2024 (in 132 °E). White and black lines are neutral density contours (28.27 γn is labelled in white). The red line highlights 240 µmol kg−1 dissolved oxygen (DO). The DSW outflow in 2024 is annotated. Locations of CTD cast and sampling depths are indicated by markers.

We define DSW as water dense enough to reach the AABW density threshold of 28.27 kg m⁻³ γⁿ (Orsi et al., 1999). For water colder than −1.5°C, this corresponds to potential density (σθ; referenced to 0 dbar) of 27.79 kg m⁻³ (see Methods for the rationale behind using potential density). This value represents the minimum density required for DSW to contribute to local AABW formation15. Within the area of interest, various historical observations including ship and biologging (see Methods for the platform type specification) support the presence of DSW and modified shelf water between DSW and local AABW along the 28.27–28.30 kg m⁻³ γn isopycnals in salinity–temperature space (Fig. 2a). DSW observed in the Dibble Polynya is fresher than Mertz-sourced water by 0.02–0.05 g kg⁻1. The fresh property of Dibble-sourced water results in its contribution to a lighter variety of local AABW, making the isopycnal salinity fresher around the Dibble Polynya (Supplementary Fig. 2). This water property is consistent with the ventilation layer lighter than upstream AABW inferred by the oxygenated density class (Fig. 1d).

Historical observations along the continental slope (1000–3000 m bottom depth) show that deep water near the Dibble Polynya is as fresh and cold as that near the Mertz Polynya and is notably fresher than water located between the two locations (Fig. 3; this is the case even if the sampled data are limited to the 2000–3000 m bottom depth). The fresh and cold condition off the Dibble and Mertz Polynyas results from frequent interleaving of shelf water into offshore water over the depths (Fig. 3e and f), indicative of shelf water outflow insufficiently dense to reach the bottom40. This along-slope salinity and temperature variation suggests that any signature of DSW outflow observed within the area of interest is attributable to DSW sourced from the Dibble Polynya rather than water exported from the upstream Mertz Polynya, further underpinning the Dibble’s contribution to local AABW. Shelf water exported from the Mertz region (Fig. 3) might descend the offshore slope locally over the 3000 m isobath, instead of flowing westward over the upper slope (as suggested by deep float profiles13).

Mean vertical profiles of (a) Conservative Temperature (°C) and b absolute Salinity (g kg−1) for three regions: “off Dibble” (magenta), “off Mertz” (blue), and “in-between” (orange). Solid lines are averaged for the 1000–3000 m slope bottom depth (shading indicates standard error), while dotted lines are averaged for the 2000–3000 m. Mean profiles on the neutral density coordinate (kg m−³) are shown in (c) and (d). e, f Are the same as (c) and (d) but only shown for “off Dibble” with original measurements to indicate frequent interleaving of cold, fresh shelf water, which has more dispersed (less homogenized) properties than offshore water. Data sourced from CCHDO (black edge), Ship, and Argo (grey edge). g Map showing the locations of hydrographic stations used to generate the mean profiles, coloured by region: magenta for “off Dibble” (128–134 °E), blue for “off Mertz” (141–145 °E), and orange for “in-between.” Black rectangle outlines the area of interest. Annual sea ice production (SIP, m yr−1) is shown with the Dibble and Mertz Polynyas labelled.

The analysis period is divided into before and after 2011 to investigate potential impacts of the Mertz Glacier Tongue calving in 2010. The presence of DSW within the area of interest before and after the calving event during both the melting and freezing seasons is supported by ship-based and biologging measurements (Supplementary Fig. 3). Further, DSW is detected by ship measurements from the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s (as γn > 28.27 kg m⁻³ and σ₀ > 27.79 kg m⁻³; Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting that the formation of DSW in the Dibble Polynya has persisted for more than 50 years. These historical measurements might be consistent with dissolved oxygen observations from 2018, 2015, 1996, the 1980s, and the early-1970s (Fig. 1d), which show oxygen-rich water (>240 μmol kg⁻¹; although not as evident as in 2024) within a density class of 28.20–28.27 kg m⁻³ γn, slightly lighter than the conventional AABW range.

Oceanic changes after the Mertz Glacier Tongue calving in 2010

The collapse of the Mertz Glacier Tongue in 2010 resulted in a sharp decline in sea ice production in the Mertz Polynya32, the calved iceberg B9B grounded in the downstream Adélie Sill—a major outlet for Mertz DSW15,16, and the subsequent reduction of ALBW34,39. No significant change in DSW is detected within the Dibble Polynya itself due to the lack of high-accuracy salinity measurements on the shelf, although observed maximum DSW salinity from ship-based measurements decreased from 34.75 to 34.72 g kg−1 (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). However, following the Mertz Glacier calving event in 2010, it is possible that DSW formed on the western side of iceberg B9B (Supplementary Fig. 2b), is transported to the Dibble Polynya by the westward coastal current39. Historical observations indicate that the distribution of DSW around the iceberg B9B changed after 2011 (Supplementary Fig. 2c and d), corresponding to the recent pattern of peak sea ice production occurring downstream of the Adélie Sill and the B9B.

A key observed change after 2011 is the abundance of modified shelf water that connects DSW and AABW along the 28.27–28.30 kg m⁻³ γn isopycnals (Fig. 4). While spatial data coverage is comparable between the two periods, modified shelf water denser than 28.27 kg m⁻³ γn is detected more frequently after 2011 (see also Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). A large part of this post-2011 modified shelf water is derived from biologging data of four individually instrumented seals. However, potential salinity errors in the biologging sensors, as inferred from differences with high-quality ship-based measurements at subsurface temperature maxima, cannot account for the observed change (Supplementary Fig. 5), and four ship-based profiles (including the 2024 CCHDO data) also support its presence. The abundance of modified shelf water after 2011 manifests a reduced gradient in cross-slope water properties near the bottom, indicating an ocean structure more favourable for DSW outflow in recent years.

a Absolute Salinity–Conservative Temperature plot within the area of interest (a) before and (b) after 2011. Markers are coloured by data platform type, whereas the 2024 CCHDO data is indicated by the black edge colour. Gray scatters in the background are CCHDO data from the Mertz region. Locations of corresponding hydrographic stations are plotted in (c) and (d) for before and after 2011, respectively. MEOP data south of 65 °S is removed for ease of comparison with the similar spatial coverage.

Satellite-based sea ice production in the Dibble and Mertz Polynyas is shown in Fig. 5a and b (see Methods). Following the major calving of Mertz Glacier Tongue in 2010, sea ice production in the Mertz Polynya is generally halved to 0.5×1011 m3 yr−1 41, dropping even below the level estimated in the Dibble Polynya. This substantial reduction led to decreased ALBW formation after the calving event34,39. Since 2012, the iceberg B9B has been grounded on the southern flank of the Adélie Sill and now supports sea ice production west of 143°E (i.e., in the iceberg’s lee against easterlies; Fig. 5c and d), facilitating the DSW formation there (Supplementary Fig. 2). In contrast, sea ice production in the Dibble Polynya remained relatively stable from 1991 to 2024 (Fig. 5a). This observation is consistent with the persistent DSW formation in the Dibble Polynya for the past several decades suggested earlier.

a Timeseries of annual sea ice production (m³ yr−1) in the Dibble Polynya (66.3–64.8°S, 132.0–135.0 °E), derived from SSM/I (solid), AMSR-E (dashed), and AMSR-2 (dotted) satellite data. b Time series of annual sea ice production (m³/yr) in the Mertz Polynya (67.3–65.7°S, 141.0–147.4 °E). Black lines represent the eastern area (143–147.4 °E) and blue lines represent the western area (141–143 °E). c Mean annual sea ice production in the Mertz Polynya derived from AMSR-E (2003–2010). Labels indicate Adélie Sill (AS), Adélie Depression (AD), and Mertz Glacier Tongue (MGT). d Same as (c) but derived from AMSR-2 (2013–2021), showing the location of the B9B iceberg calved from the MGT grounded near the AS. Timeseries of (e) Absolute Salinity (g kg−1) within the upper AABW 28.27–28.30 γn, f thickness (m) by the depth of 28.27 γn, and (g) Conservative Temperature (°C) at 300 dbar (as the Antarctic Slope Front proxy) in the area of interest are plotted against slope bottom depth (m). CCHDO data is shown by large circle with black edge colour (MEOP data are used only in (g)). Dashed lines represent the linear regression of the labelled values calculated using the surface data, which is first regressed as a function of depth for each year, and then linearly interpolated across the years. These panels are projected onto the bottom depth–property space in (h), (i) and (j) to reveal changes in the cross-slope gradient between 1996–2010 (blue) and 2011–2024 (red). Linear regressions are calculated for the 500–3000 m (solid), 500–2000 m (dashed), and 750–3000 m (dotted) depth ranges.

To explore the cause of the cross-slope bottom water properties shown in Fig. 4, time series of water properties within the area of interest are shown relative to bottom depth (Fig. 5e–g). After 2011, salinity in upper AABW (28.27–28.30 kg m⁻³ γn) shows a decline in cross-slope gradients, largely due to an offshore shift of the 34.84 g kg⁻¹ isohaline (Fig. 5e) and a reduction in fresher inshore water between the 500–750 m depth range (Fig. 5h). At the same time, the thickness of offshore AABW has decreased as revealed by the offshore migration of the 1000 m thickness isopleth, likely contributing to the observed reduction in thickness gradients (Fig. 5f; although the change in thickness gradient might not be as significant as the salinity gradient as detailed in Methods). These changes are consistent with previously reported trends of AABW freshening and volume contraction over recent decades20,27,28,29,30.

In addition to the reduction of ALBW, the multidecadal freshening trend of RSBW—driven by ongoing glacial meltwater discharge from West Antarctica28,30,31—suggests that declines in both ALBW and RSBW formation may have contributed to local AABW freshening and contraction, and subsequently to the reduced salinity and thickness gradients observed within the area of interest. The observed changes in the cross-slope property gradients imply that upstream AABW reduction may be influencing the structure of the westward ASC near the Dibble Polynya, which has been considered as a barrier to cross-slope water exchange20,42.

Discussion

Effect of reduced upstream bottom water on Dibble outflows

As DSW descends downslope and is deflected by the Coriolis force, it imparts westward momentum and bottom-intensifies the ASC42. This provides the physical basis for hypothesising that the upstream AABW reduction can lead to a decrease in the westward momentum of the ASC. A compilation of historical shipboard acoustic velocity measurements is not inconsistent with this hypothesis (Supplementary Fig. 6), although the dataset is substantially limited by spatial sparsity and a shallow depth range only to 400 m. Dynamic height derived from hydrography does not show any systematic feature (not shown). The most appropriate analysis given the data limitations is cross-slope temperature gradient associated with the ASC’s frontal structure (Fig. 5g). The −0.3°C and −0.7°C isotherms at 300 dbar are characteristic of the ASC, encircling most of the Antarctic margin22,43. The historical temperature records within the area of interest shows shoreward shifts of the 1.0, −0.3 and −1.4°C isotherms, consistent with the multidecadal poleward shift of warm deep water35,36. In contrast, the −0.7°C isotherm has shifted offshore. Although an implication of these changes for the strength of ASC’s barrier requires further investigation, the presented results reflect observed changes in its structure near the Dibble Polynya over the past 30 years.

A previous comparison of hydrographic data from 1996 and 201920 revealed a decrease in westward ASC transport of over 10 Sv (=10⁶ m³ s⁻¹) across all five cross-slope repeated transects (along 113°, 120°, 128°, 140°, and 150°E). In this comparison, an isotherm characteristic of the ASC shifted offshore along 128°E, despite the overall poleward migration of offshore warm water—an observation similar to Fig. 5g. At the same time, bottom water temperatures near the shelf break increased across all five sections. These changes suggested a weakening of the ASC’s barrier effect. Furthermore, a previous modelling study44 showed that upstream freshening weakens both the westward ASC and its capacity to restrict cross-slope fluxes, highlighting the substantial impact of glacial meltwater on ocean circulation as well as on DSW formation45,46. While this discussion assumes the ASC is generally depth-independent, a recent study showed that correlations between surface and near-bottom components of the ASC can be weak or non-significant47, emphasising the need for more velocity measurements to validate the proposed mechanism.

Bottom water changes between the 1990s–2000s and 2010s–2020s

The observed changes presented in this study are summarised schematically in Fig. 6. While DSW formation in the Dibble Polynya has persisted throughout both periods, the reduction in upstream AABW formation has altered the ocean structure. During the 1990s–2000s (Fig. 6a), relatively active formation of ALBW and RSBW maintained a strong westward ASC, which may have acted as a dynamic barrier, limiting outflow of not-so-dense shelf water from the Dibble Polynya. In recent years (2010s–2020s; Fig. 6b), DSW formed in the Dibble Polynya is exported to the ocean abyssal basin more readily, potentially advantaged by the reduction in upstream AABW formation and its subsequent weakening of the ASC’s barrier effect. Although no significant change in shelf water properties has been detected, it is possible that the westward-flowing coastal current upstream of the Dibble Polynya has transported DSW formed on the western flank of the grounded iceberg B9B, potentially augmenting DSW in the Dibble Polynya, as well as glacial meltwater that can affect shelf water property there. Our analysis indicates a change in the DSW pathway near the B9B after 2011, consistent with the increased sea ice production in its western flank (Supplementary Fig. 2). In this context, significantly abundant glacial meltwater was reported48 over the continental slope of 128°E in 2019, which may have originated from the Adélie Coast and affected shelf water in the Dibble Polynya.

a Conditions in the 1990s–2000s: The formation of Adélie Land Bottom Water (ALBW, light blue) and Ross Sea Bottom Water (RSBW, red) was relatively active during this period, resulting in a thick AABW layer (purple) and a strong Antarctic Slope Current that acts as a barrier to DSW outflow from the Dibble Polynya (magenta). b Conditions during the 2010s–2020s: A reduction in upstream AABW appears to have affected the ocean structure, making it more favourable for DSW outflow from the Dibble Polynya. This may be due to the weakening of the ASC barrier (grey ellipse). Sea ice production in the Dibble Polynya has remained stable throughout the two periods, contrasting to the sharp decline of sea ice production in the Mertz Polynya due to the major icescape changes. The potential DSW/glacial meltwater pathway by the coastal current from the Mertz region to the Dibble Polynya is indicated by the blue dashed arrow. After 2011, sea ice production in the west of B9B increased significantly, which might have changed the DSW pathway nearby as indicated by Supplementary Fig. 2.

We conclude that the Dibble Polynya has continuously produced DSW over the past 50 years, contributing to a lighter variety of local AABW. Emerging outflow from the polynya ventilates AABW even as the densest varieties contract, partly offsetting regional declines in AABW volume. This study suggest that, in light of the ongoing and projected decline of the densest layer of AABW26,27,29,30,49,50 and the weakening of stratification along AABW pathways51, it is increasingly important to monitor not only the major AABW formation sites, but also not-so-dense shelf water varieties6,21. Particularly in the context of the anticipated impacts of Antarctic glacial and sea-ice melt on the ocean circulation and AABW formation45,46,52, shifts toward lighter ventilation pathways could have outsized consequences for the Southern Ocean’s capacity to store heat and carbon, global sea level, and multidecadal-to-centennial climate feedbacks, underscoring the need for extensive bottom water monitoring.

Methods

Hydrographic measurements

We integrate the most comprehensive dataset combining all available observational sources to analyse AABW and shelf water properties around the Dibble Polynya. The CLIVAR and Carbon Hydrographic Data Office (CCHDO; https://cchdo.ucsd.edu/) provides high-quality, full-depth Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) profiles with dissolved oxygen measurements calibrated using bottle samples. These data follow the Global Ocean Ship-based Hydrographic Investigations Program (GO-SHIP) standard. The CCHDO data include observations from the Multidisciplinary Investigation of Southern Ocean (MISO) conducted by RV Investigator in the 2024 austral summer (IN2024_V01), offering the most direct evidence of the DSW outflow from the Dibble Polynya. Within the area of interest, the CCHDO data were available from in 1996 (AR9604 by RSV Aurora-Australis), 2018 (IN2018_V01 by RV Investigator), 2019 (KY1804 by RV Kaiyo-maru), and 2024. Measurements of temperature, practical salinity, and dissolved oxygen are accurate to within ±0.002 °C, ±0.002 practical salinity units (psu) and 1%, respectively.

Ship-based observations outside the CCHDO data are referred to as “Ship data”. This category includes CTD and oxygen profiles from NBP1503 by RVIB Nathaniel B. Palmer in 2015, as well as CTD profiles from the World Ocean Database (WOD), including those collected by USNS Eltanin and Soviet Union ships during the 1970s and 1980s. While the accuracy of pre-1990s data is unknown, other cruise data during the same period suggest ±0.005 °C, ±0.003–0.01 psu53, and ~10% for dissolved oxygen54. Additionally, the Ship data include eXpendable CTD (XCTD) profiles from the WOD and the Japanese Institute for Cetacean Research, spanning the 2000s to the early 2010s. XCTD data are likely accurate to ±0.02°C and ~0.05 psu55. Outliers and spikes in the XCTD data are removed following the WOD 2018 User’s Manual. These datasets provide the baseline for evaluating long-term changes in water properties and the evolution of DSW and AABW over recent decades (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Complementary to the Ship data, Argo float profiles56 and biologging data from the Marine Mammals Exploring the Oceans Pole-to-Pole (MEOP)57 are also used. The accuracy of Argo data is ±0.002°C and ±0.01 psu, and that of high-resolution MEOP data is ±0.02°C and ±0.03 psu58. Although the accuracies of MEOP and XCTD data are relatively low, DSW in the Dibble Polynya derived from these measurements is supported by its consistency with bottle-sampled data from USNS Eltanin and Soviet Union ships. The presence of modified shelf water after 2011 is supported by MEOP, but this is unlikely attributable to its potential bias (see Supplementary Notes).

Hydrographic data analysis

All CTD and oxygen profiles used in this study are interpolated at 1 dbar intervals before analysis. The Thermodynamic Equation of Seawater 2010 (TEOS-10)59 and its translation into Python (https://github.com/TEOS-10/python-gsw) are used to derive Conservative Temperature and Absolute Salinity. Following the convention2, seawater with a neutral density60 γn greater than 28.27 kg m−3 is defined as AABW or DSW, with dense water located inshore of the 1,000 m isobath or colder than −1.5°C as DSW. Conservative Temperature is nearly equivalent to conventional potential temperature within the uncertainty of our measurements, while Absolute Salinity is typically about 0.02 parts per thousand higher than practical salinity in the study area. Potential density σθ is used to describe shelf water density since a neutral surface approximated by the scheme60 is highly uncertain on the continental shelf. The neutral density unit is also used over the continental slope since the thermobaricity of seawater makes potential density not suitable for tracking neutral surface over a wide range of depths. 14 profiles from Ship data and 4 seal-tagged instruments from MEOP data support the presence of DSW in the Dibble Polynya denser than 28.27 kg m−3 γn and 27.79 kg m−3 σθ.

Factors justifying the area of interest (Fig. 1c) are: 1) the eastern boundary downstream of the Dibble Polynya’s eastern edge, 2) the western boundary including two CCHDO campaigns conducted in 1996 and 2019, 3) the northern boundary covering the 3,000 m isobath of the continental slope, which is characteristic to the continental rise, 4) the southern boundary ensuring a sufficient number of observations on the shelf. The increased data coverage in the later period (Supplementary Fig. 2) is largely due to the prevalence of Argo float and biologging data. The MEOP and XCTD profiles are mostly limited to depths above 1,000 m, resulting in more points in Fig. 4 than in Fig. 2 (bottom 100 m average) within the area of interest. MEOP data are excluded from Fig. 5e and f due to its relatively low accuracy in salinity (see also Supplementary Notes). Meanwhile, XCTD data are included since the reliability of salinity can be confirmed by its consistency with the CCHDO data.

A limitation of our analysis is that it synthesizes observations with heterogeneous precision and sampling coverage. While recent CCHDO CTD and oxygen data are high-accuracy, older shipboard CTD-oxygen and XCTD profiles, as well as MEOP biologging data, have lower and more variable accuracies. These old data are still required to extend the analysis data coverage in space and time. Many MEOP/XCTD profiles are generally shallower than 1,000 m and the number of deep ship casts within the area of interest is very limited, so bottom-intensified signals can be under-sampled and inferred decadal changes are sensitive to evolving platform availability. The lack of velocity data is also the major limitation (Supplementary Fig. 6), and we emphasise the need for targeted observations over the slope to more rigorously test our hypothesis.

Satellite sea ice production

We used satellite passive microwave radiometer data to estimate sea ice production in coastal polynyas. The amount of sea ice production in coastal polynyas can be estimated from a heat budget analysis that considers the thickness distribution of thin ice8. In addition, the thin ice thickness distribution in coastal polynyas can be inferred from thin ice thickness algorithms based on satellite passive microwave radiometers. In this study, we define coastal polynyas as areas of thin ice with a thickness of 20 cm or less and estimate the sea ice production in coastal polynyas by combining the thin ice thickness algorithm with a heat budget analysis61. Further details are provided in Supplementary Information.

Data availability

The post-processed data presented in this study are open to the public via Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/15468508). The CCHDO hydrographic data are accessible via the CLIVAR and Carbon Hydro graphical Data Office websites (https://cchdo.ucsd.edu/). The Argo data were collected and made freely available by the International Argo Program (http://www.argo.ucsd.edu, https://www.euro-argo.eu). The biologging data were made freely available by the International MEOP Consortium and the AniBOS network (http://www.meop.net). Ship data from World Ocean Database and World Ocean Atlas are available from National Centers for Environmental Information, NOAA.

Code availability

The code presented in this study is open to the public via Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/15468508).

References

Gill, A. E. Circulation and bottom water production in the Weddell Sea. Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts 20, 111–140 (1973). February.

Orsi, A. H., Johnson, G. C. & Bullister, J. L. Circulation, mixing, and production of Antarctic Bottom Water. Progress in Oceanography 43, 55–109 (1999).

Foster, T. D. Abyssal water mass formation off the eastern Wilkes land coast of Antarctica. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 42, 501–522 (1995).

Rintoul, S. R. On the origin and influence of Adélie Land Bottom Water. Ocean, ice, and atmosphere: Interactions at the Antarctic continental margin 75, 151–171 (1998).

Ohshima, K. I. et al. Antarctic Bottom Water production by intense sea-ice formation in the Cape Darnley polynya. Nature Geoscience 6, 235–240 (2013).

Portela, E. et al. Controls on dense shelf water formation in four East Antarctic polynyas. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 127, e2022JC018804 (2022).

Nihashi, S., Ohshima, K. I. & Tamura, T. Reconstruct the AMSR-E/2 thin ice thickness algorithm to create a long-term time series of sea-ice production in Antarctic coastal polynyas. Polar Sci. 39, 100978 (2024).

Tamura, T., Ohshima, K. I. & Nihashi, S. Mapping of sea ice production for Antarctic coastal polynyas. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L07606 (2008).

Nihashi, S. & Ohshima, K. I. Circumpolar mapping of Antarctic coastal polynyas and landfast sea ice: Relationship and variability. J. clim. 28, 3650–3670 (2015).

Miller, U. K. et al. High Salinity Shelf Water production rates in Terra Nova Bay, Ross Sea from high-resolution salinity observations. Nature Communications 15, 373 (2024).

Whitworth, T. III Two modes of bottom water in the Australian-Antarctic Basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 17–1 (2002).

Thomas, G., Purkey, S. G., Roemmich, D., Foppert, A. & Rintoul, S. R. Spatial variability of Antarctic bottom water in the Australian Antarctic Basin from 2018–2020 captured by Deep Argo. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089467 (2020).

Foppert, A. et al. Deep Argo reveals Bottom Water properties and pathways in the Australian-Antarctic basin. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 126, e2021JC017935 (2021).

Sholeninova, P., Morrison, A. K., McC. Hogg, A. & Foppert, A. Quantification of Antarctic Bottom Water Pathways in the Australian - Antarctic Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 130, e2024JC022305 (2025).

Williams, G. D., Bindoff, N. L., Marsland, S. J. & Rintoul, S. R. Formation and export of dense shelf water from the Adélie Depression, East Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 113, C04039 (2008).

Williams, G. D. et al. Antarctic bottom water from the Adélie and George V Land coast, East Antarctica (140–149 E). J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 115, C04027 (2010).

Shimada, K., Aoki, S., Ohshima, K. I. & Rintoul, S. R. Influence of Ross Sea Bottom Water changes on the warming and freshening of the Antarctic Bottom Water in the Australian-Antarctic Basin. Ocean Sci. 8, 419-432 (2012).

Bindoff, N. L., Rosenberg, M. A. & Warner, M. J. On the circulation and water masses over the Antarctic continental slope and rise between 80 and 150 E. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 47, 2299–2326 (2000).

Yamazaki, K., Aoki, S., Shimada, K., Kobayashi, T. & Kitade, Y. Structure of the subpolar gyre in the Australian - Antarctic Basin derived from Argo floats. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 125, e2019JC015406 (2020).

Yamazaki, K. et al. Revisiting circulation and water masses over the East Antarctic margin (80–150° E). Progress in Oceanography, 103285 (2024).

Kitade, Y. et al. Antarctic bottom water production from the Vincennes Bay polynya, East Antarctica. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3528–3534 (2014).

Yamazaki, K. et al. Unlocking Southern Ocean Under-ice Seasonality with a New Monthly Climatology. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 130, e2024JC020920 (2025).

Ribeiro, N. et al. Warm modified circumpolar deep water intrusions drive ice shelf melt and inhibit dense shelf water formation in Vincennes Bay, East Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 126, e2020JC016998 (2021).

Ribeiro, N. et al. Oceanic regime shift to a warmer continental shelf adjacent to the Shackleton Ice Shelf, East Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 128, e2023JC019882 (2023).

Silvano, A. et al. Observing Antarctic bottom water in the Southern Ocean. Frontiers in Marine Science 10, 1221701 (2023).

Johnson, G. C. & Purkey, S. G. Refined estimates of global ocean deep and abyssal decadal warming trends. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL111229 (2024).

van Wijk, E. M. & Rintoul, S. R. Freshening drives contraction of Antarctic bottom water in the Australian Antarctic Basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1657–1664 (2014).

Aoki, S. et al. Reversal of freshening trend of Antarctic Bottom Water in the Australian-Antarctic Basin during 2010s. Scientific reports 10, 14415 (2020).

Shimada, K. et al. Shoaling of abyssal ventilation in the Eastern Indian Sector of the Southern Ocean. Communications earth & environment 3, 120 (2022).

Gunn, K. L., Rintoul, S. R., England, M. H. & Bowen, M. M. Recent reduced abyssal overturning and ventilation in the Australian Antarctic Basin. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 537–544 (2023).

Jacobs, S. S., Giulivi, C. F. & Dutrieux, P. Persistent Ross Sea freshening from imbalance West Antarctic ice shelf melting. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 127, e2021JC017808 (2022).

Tamura, T., Williams, G. D., Fraser, A. D. & Ohshima, K. I. Potential regime shift in decreased sea ice production after the Mertz Glacier calving. Nat. commun. 3, 826 (2012).

Katsumata, K., Nakano, H. & Kumamoto, Y. Dissolved oxygen change and freshening of Antarctic Bottom water along 62 S in the Australian-Antarctic Basin between 1995/1996 and 2012/2013. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 114, 27–38 (2015).

Snow, K., Rintoul, S. R., Sloyan, B. M. & Hogg, A. M. Change in dense shelf water and Adélie Land bottom water precipitated by iceberg calving. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 2380–2387 (2018).

Yamazaki, K., Aoki, S., Katsumata, K., Hirano, D. & Nakayama, Y. Multidecadal poleward shift of the southern boundary of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current off East Antarctica. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf8755 (2021).

Herraiz-Borreguero, L. & Naveira Garabato, A. C. Poleward shift of circumpolar deep water threatens the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 728–734 (2022).

Akhoudas, C. H. et al. Ventilation of the abyss in the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean. Scientific Reports 11, 6760 (2021).

Primeau, F. W. & Holzer, M. The ocean’s memory of the atmosphere: Residence-time and ventilation-rate distributions of water masses. Journal of physical oceanography 36, 1439–1456 (2006).

Kusahara, K. et al. Modeling ocean-cryosphere interactions off Adélie and George v land, east Antarctica. J. Clim 30, 163–188 (2017).

Carmack, E. C. & Killworth, P. D. Formation and interleaving of abyssal water masses off Wilkes Land. Antarctica. Deep sea research 25, 357–369 (1978).

Nihashi, S., Ohshima, K. I. & Tamura, T. Sea-ice production in Antarctic coastal polynyas estimated from AMSR2 data and its validation using AMSR-E and SSM/I-SSMIS data. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing Vol. 10, 3912–3922 (2017).

Thompson, A. F., Stewart, A. L., Spence, P. & Heywood, K. J. The Antarctic Slope Current in a changing climate. Rev. Geophys. 56, 741–770 (2018).

Pauthenet, E., Sallée, J. B., Schmidtko, S. & Nerini, D. Seasonal variation of the Antarctic Slope Front occurrence and position estimated from an interpolated hydrographic climatology. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 51, 1539–1557 (2021).

Nakayama, Y. et al. Antarctic slope current modulates ocean heat intrusions towards Totten Glacier. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094149 (2021).

Silvano, A. et al. Freshening by glacial meltwater enhances melting of ice shelves and reduces formation of Antarctic Bottom Water. Science advances 4, eaap9467 (2018).

Aoki, S. et al. Warm surface waters increase Antarctic ice shelf melt and delay dense water formation. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 142 (2022).

Huneke, W. G., Morrison, A. K. & Hogg, A. M. Decoupling of the Surface and Bottom-Intensified Antarctic Slope Current in Regions of Dense Shelf Water Export. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104834 (2023).

Aoki, S., Yamazaki, K., Hirano, D., Nomura, D. & Murase, H. Distribution of stable oxygen isotope in seawater and implication on freshwater cycle off the coast from Wilkes to George V Land, East Antarctica. Prog. Oceanogr. 217, 103101 (2023).

Zhou, S. et al. Slowdown of Antarctic Bottom Water export driven by climatic wind and sea-ice changes. Nature climate change 13, 701–709 (2023).

Li, Q., England, M. H., Hogg, A. M., Rintoul, S. R. & Morrison, A. K. Abyssal ocean overturning slowdown and warming driven by Antarctic meltwater. Nature 615, 841–847 (2023).

Tan, S. & Thurnherr, A. M. On the global decrease in the deep and abyssal density stratification along the spreading pathways of Antarctic Bottom Water since the 1990s. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102422 (2023).

Doddridge, E. W. et al. Impacts of recent Antarctic Sea-Ice Extremes. PNAS Nexus 4, pgaf164 (2025).

Johnson, G. C. & Orsi, A. H. Southwest Pacific Ocean water-mass changes between 1968/69 and 1990/91. J. Clim 10, 306–316 (1997).

Gordon, A. L. Potential temperature, oxygen and circulation of bottom water in the Southern Ocean. Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts 13, 1125–1138 (1966).

Gille, S. T., Lombrozo, A., Sprintall, J., Stephenson, G. & Scarlet, R. Anomalous spiking in spectra of XCTD temperature profiles. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 26, 1157–1164 (2009).

Argo. Argo float data and metadata from Global Data Assembly Centre (Argo GDAC) [Data set]. SEANOE https://doi.org/10.17882/42182 (2000).

Treasure, A. M. et al. Marine mammals exploring the oceans pole to pole: A review of the MEOP consortium. Oceanography 30, 132–138 (2017).

Siegelman, L. et al. Correction and accuracy of high- and low-resolution CTD data from animal-borne instruments. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 36, 745–760 (2019).

McDougall, T. J. & Barker, P. M. Getting started with TEOS-10 and the Gibbs Seawater (GSW) Oceanographic Toolbox. SCOR/IAPSO WG 127, 1–28 (2011).

Jackett, D. R. & McDougall, T. J. A neutral density variable for the world's oceans. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 27, 237–263 (1997).

Kashiwase, H., Ohshima, K. I., Nakata, K. & Tamura, T. Improved SSM/I thin ice algorithm with ice type discrimination in coastal polynyas. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol. 38, 823–835 (2021).

Fraser, A.D. and Massom, R. (2020) Circum-Antarctic landfast sea ice extent, 2000-2018, Ver. 2.2, Australian Antarctic Data Centre - https://doi.org/10.26179/5d267d1ceb60c, Accessed: 2025-05-07

Dorschel, B. et al. The international bathymetric chart of the southern ocean version 2. Scientific Data 9, 275 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the use of the CSIRO Marine National Facility (https://ror.org/01mae9353) and grant of sea time on RV Investigator in undertaking this research. We are grateful to the R/V Investigator captain, crew members, technicians and participants for conducting the research cruise IN2024_V01 MISO. This research was supported by the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS) and the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership (AAPP), through grant funding from the Australian Government as part of the Antarctic Science Collaboration Initiative program. The Argo data were collected and made freely available by the International Argo Program and the national programs that contribute to it. (https://argo.ucsd.edu, https://www.ocean-ops.org). The MEOP data were collected and made freely available by the International MEOP Consortium and the national programs that contribute to it. (http://www.meop.net). The Argo Program and MEOP (under AniBOS; https://anibos.com/) are parts of the Global Ocean Observing System. The sea ice production data were generated with the support of JSPS KAKENHI Grants (22K18026, 25H02643). The authors thank Sohey Nihashi for providing the climatological sea ice production by the AMSR series. We also thank three peer reviewers whose comments and suggestions greatly improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Y. and S.R.R. conceived the study. A.F. and S.R.R. designed and led the IN2024_V01 hydrography. K.Y., A.F., K.L.G., J.N., S.B. and P.S. sampled the data during IN2024_V01. H.K. generated and processed the sea ice production data. T.I. and K.M. collected and processed the JARPA I/II XCTD data. K.Y. curated data, performed the formal analysis, created the figures and wrote the first draft. K.Y., A.F., K.L.G., S.R.R., J.N., E.M.W. and L.H.B. interpreted the results. K.Y., A.F., K.L.G., S.R.R., H.K., S.B., P.S., T.I., E.M.W. and L.H.B. revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Kay Ohshima and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Sreelekha Jarugula and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamazaki, K., Foppert, A., Gunn, K.L. et al. Emerging outflow of not-so-dense shelf water from an East Antarctic polynya. Commun Earth Environ 7, 38 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03006-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03006-5