Abstract

Cosmic-ray muons are naturally abundant, high-energy particles that can probe geological structures. Muography exploits muon attenuation or scattering to infer density variations, offering a non-invasive and cost-effective method for subsurface studies. We present laboratory and Monte Carlo simulation evidence for density estimation of porous media with varying fluid saturation, measured by coincident muon flux using plastic scintillator detectors. Muon flux was recorded after transmission through acrylic and sand samples of known density and thickness, and the results were validated against simulations that tracked attenuation as a function of density. Muon flux attenuation systematically reflected changes in material density and fluid saturation. Using a Gaussian-filtered dataset and an exponential model, the estimated bulk density of acrylic closely matched the known value (1.19 g cm⁻³), with relative errors decreasing from 11.1% at 20 cm to 0.34% at 80 cm. For variably saturated sands, densities ranged from 1.01 ± 0.12 g cm⁻³ (0% saturation) to 1.54 ± 0.13 g cm⁻³ (100% saturation), with relative errors improving from 21.1% to 10.8%. Numerical simulations reproduced the same attenuation trends, with errors of less than 1%. These findings demonstrate muography’s sensitivity to subtle density variations, highlighting its potential for reservoir monitoring and imaging density-linked fluid dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cosmic-ray muons are high-energy secondary subatomic particles produced by interactions between primary cosmic-rays and atmospheric nuclei in the Earth’s upper atmosphere. The primary cosmic-rays consist of protons and heavy nuclei of extraterrestrial origin1. Muons share fundamental properties with electrons, such as carrying an electric charge and possessing a spin of ½ intrinsic angular momentum2. Muons, with a mass of about 105.7 MeV c-², are approximately 207 times heavier than electrons, making them less responsive to acceleration by electromagnetic fields3,4. Due to their higher energy, greater mass, and longer lifetime compared to conventional radiographic probes such as electrons, X-rays, and γ-rays, muons possess strong penetrating capabilities, enabling them to reach the Earth’s surface and propagate through thick and dense materials5,6. Charged particles such as muons interact with electrons in matter primarily through ionization as they traverse a medium. The material’s thickness and density directly influence the extent of their energy loss (absorption) or deflection (scattering angle)7,8,9. Two main muography techniques have been developed based on these interactions: one focusing on muon scattering and the other on muon absorption10. By examining the extent of energy loss and changes in trajectory, it is possible to estimate the material’s density11,12,13. This makes cosmic-ray muons a valuable natural probe for non-invasive imaging of geological structures2,14. The principle behind absorption muography is based on its function as a density-length (\(\rho \cdot x\); also referred to as opacity), where the integrated density along the trajectory of cosmic-ray muons is measured as they pass through a material15. Denser or thicker materials cause more interactions, leading to greater attenuation. Consequently, a reduction in the number of muons that reach the detector16. Scattering muography reconstructs angular deflections that are primarily governed by the radiation length\(.\) These deflections are relatively smaller in low-atomic-number (low-Z) materials and larger in high-Z targets. Accurate use of this technique requires precise tracking of both incident and emergent trajectories, as well as consideration of the muon momentum spectrum7,17,18. Given the centimeter-scale low-Z samples used in this study and the configuration of vertical coincidence detectors without incident-angle tracking, absorption-based muography represents a suitable approach for achieving reliable density-length estimations.

Following the discovery of cosmic-rays19,20,21,22,23,24 and muons25, there was a growing interest in utilizing muons for imaging for different applications. The initial investigations into muon imaging were prompted by the need to assess the geological overburden above a road tunnel within a mountainous terrain using particle detectors19. Following this, solid muography involving the visualization of the interiors of large and dense structures, such as pyramids, mountains, and volcanoes, was first introduced by Alvarez et al.26. Since then, muography has been used for different applications, including volcanic structures27,28,29,30,31, mineral explorations32,33,34,35, underground structures imaging36,37,38, manmade objects39,40,41, magnetic field studies42, imaging and monitoring of nuclear plants43,44,45,46,47 and small-scale controlled experiments48,49,50. Moreover, previous work discussed joint inversion of muography with other geophysical methods, such as gravity51,52,53,54 and seismic50, to enhance density estimation by directly leveraging the sensitivity of muography to density.

Geophysical methods, such as seismic and gravity, have been widely employed to estimate subsurface densities. Although these methods have been extensively applied and significantly advanced, they still encounter challenges that impact the accuracy and spatial resolution of density estimations55,56,57,58. Moreover, accurate estimation of fluid saturation remains inherently more challenging than bulk density due to its dependence on subtle contrasts in fluid composition, distribution, and pore structure59. Conventional geophysical methods typically lack direct sensitivity to saturation, often relying on indirect or assumption-laden interpretations60,61. This complexity underscores the need for techniques capable of capturing both density and saturation degree.

Subsurface characterization is traditionally conducted using geophysical techniques such as seismic, electromagnetic, magnetic, and gravity surveys62,63,64. Among these, seismic methods are most commonly employed for subsurface structural imaging due to their depth penetration and ability to delineate lateral and vertical variations in elastic properties65. Yet, these approaches often suffer limitations related to incomplete spatial coverage, high operational costs, and inherent non-uniqueness in data interpretation. In particular, seismic methods face challenges in accurately quantifying fluid saturation, as their sensitivity to pore-scale variations, especially the presence of small amounts of gas, is limited and highly nonlinear61,66. Precise density models are essential for applications such as mineral exploration, reservoir characterization, and environmental monitoring. Hence, muography offers several potential advantages, including its non-invasive nature, wide field of view, reliance on naturally occurring particle flux, and the potential for improved model uniqueness, making it a promising alternative or complement to conventional approaches. Moreover, muography may provide better spatial resolution than traditional geophysical methods, such as gravity or magnetic methods2,9,67,68. Muography resolving capabilities are highly dependent on factors such as detector configuration, exposure time, and the distance to the target, which should be considered in practical applications2,9. Despite its many advantages, muography faces limitations such as reduced flux at large depths (>1000 m), resolution constraints dictated by detector design, sensitivity to environmental factors, and density estimation due to the inverse problem69. Although some studies have examined muography’s applicability to porous media and fluid variation using simulation approaches70,71,72,73,74, there is a lack of laboratory-scale experiments focusing on small density variations and density estimation in porous materials. Moreover, translating geophysical measurements into accurate density estimates in porous materials remains a challenge, especially when fluid saturation levels vary. Dynamic fluid content can alter the overall density in ways that are difficult to quantify with conventional geophysical methods. Subsurface density anomalies typically arise from contrasts between localized bodies and the surrounding host rock, such as ore deposits, voids, water- or fluid-filled reservoirs, or compact rock formations. However, the influence of saturation degree on density has not been adequately addressed despite its critical role in controlling bulk density in such media. Identifying and characterizing these anomalies is crucial for ensuring the accuracy of imaging and monitoring the subsurface, as they are essential for various subsurface applications.

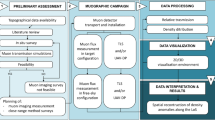

In this study, we investigated the applicability of using muon detection as a primary method for estimating material density length variations for homogeneous and dynamic fluid changes in a porous medium. We conducted laboratory experiments and validated them using a numerical simulation approach to establish a robust muon-based approach for density estimation (Fig. 1). We systematically measured the muon flux through objects of known density and thickness, including acrylic and sand samples with varying degrees of fluid saturation. We obtained a muography attenuation model using known density length and measured muon counts, which we applied to obtain the water density in a porous medium. Results from both approaches demonstrate consistency in muography reliability and sensitivity potential for detecting small-scale changes in bulk density associated with degree of fluid saturation variations and subtle delineation of estimated densities. This work contributes to the advancement of geophysical subsurface imaging by demonstrating the effectiveness of muography in estimating density in porous media.

Schematic flowchart representation of the experimental and analytical framework of experimental data. Muography experiments were conducted on sand cubes with varying densities associated with fluid content variations, as well as on acrylic boxes with changing lengths. Hourly muon flux data from the acrylic experiment were fitted to develop an absorption model, which enables the estimation of density and fluid saturation. Laboratory Gaussian pulse filtering and environmental corrections were investigated to improve measurement reliability. The same workflow was adopted for the numerical simulation data; however, no filtering methods were used, as simulations focused exclusively on positively and negatively charged muons. Simulation outputs supported model validation and interpretation.

Results

Laboratory experiment

A detailed description of the experimental target configurations, detector geometry, coincidence trigger, and acquisition settings is provided in the methodology section. We measured muon fluxes in homogeneous acrylic and variably saturated sands (Fig. 2). The results show a steady decline in muon flux with increasing density length for both materials. For the acrylic series (Fig. 2a), the mean hourly muon flux (\({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\)) decreases with the addition of acrylic cubes. The flux drops from 326.97 muons in the empty configuration to 309.02 muons with one 20 cm acrylic cube, 306.62 muons with two 40 cm cubes, 301.44 muons with three 60 cm cubes, and further to 298.41 muons with four 80 cm thick four acrylic cubes. An exponential fit yields an R2 of 0.85 and \({{{{{\rm{\chi }}}}}^{2}}_{{red}}\) of 2.714. Meanwhile, an exponential model with a constant, resulting in an R2 of 0.976 and \({{{{{\rm{\chi }}}}}^{2}}_{{red}}\) of 0.0490, having a better fit to the muography measurements. The one sigma (1σ) error bars are well separated across thicknesses, except for 20-40 cm, where they overlap. Standard deviation (SD) bars across repeated measurements of each object (Fig. 2a) show high deviation from the mean. For the sands (Fig. 2b), the mean flux decreased from 302.31 muons at 0% saturation (four dry sand cubes) to 296.4 muons at ~25% saturation, 295.54 muons at ~50%, 293.87 muons at ~75%, and to 292.55 muons at 100% saturation (four saturated sand cubes). An exponential model gives an R2 of 0.863, \({{{{{\rm{\chi }}}}}^{2}}_{{red}}\) of 0.538. However, the exponential model with a constant has achieved a better fit, similar to the acrylic objects, with R2 = 0.973, \({{{{{\rm{\chi }}}}}^{2}}_{{red}}\) = 0.392. The ±1σ error envelope overlaps across all saturation levels, and the SD (Fig. 2b) ranges from ±1.5 to ±4, overlapping in the 25-100% saturation experiment.

Regression fitting analysis using two functions (exponential and exponential with a constant c), where the mean flux decreases as the density-length increases. a The relationship between the measured mean raw hourly muon flux (\({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\)) and b changing acrylic length and the relationship between measured mean raw hourly muon flux (\({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\)) and changing fluid saturation changing sand. The error bars represent 1σ (blue) and the SD of the three measurements per object, showing the statistical spread of the data.

The raw muon flux data were filtered using a Gaussian filter to isolate the muon signal from background noise and other unwanted particles (Fig. 3), as this approach dynamically centers on the muon peak, suppresses random coincidences and low-energy background events (e.g., γ-rays, electrons), and provides a statistically robust window compared to other filters, which are more vulnerable to noise and detector response asymmetries. The filtered muography measurements show the same monotonic attenuation as the raw data, but at a lower absolute flux level. For the acrylic series (Fig. 3a, c), the mean hourly muon flux \({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) decreases from 231.98 muons in the empty configuration to 219.25 muons at 20 cm, 217.11 muons at 40 cm, 213.0 muons at 60 cm, and to 210.20 muons with 80 cm thick acrylic cubes. The largest difference is between the background and the 20 cm of acrylic. An exponential model yields an R2 of 0.876 with \({{{{{\rm{\chi }}}}}^{2}}_{{red}}\) = 1.235. The fitting increases by adding a constant, achieving R2 = 0.976 and \({{{{{\rm{\chi }}}}}^{2}}_{{red}}\) = 0.048. The 1σ error bars are separate except for between 20 and 40 cm, while SD bars (Fig. 3a) range from ±1.62 to ±5.75 across thicknesses. For variably saturated sand (Fig. 3b, d), \({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) decreases from 212.48 muons at 0% saturated sands (fully dry four sand cubes), to 210.5 muons at ~25%, 209.4 muons at ~50%, 208.86 muons at ~75%, and to 207.48 muons at ~100% saturated sands (four fully saturated sand cubes). The exponential fit yields an R2 of 0.964 and \({{{{{\rm{\chi }}}}}^{2}}_{{red}}\) of 0.538. An exponential model with a constant achieved a better fit with an R2 of 0.981 and \({{{{{\rm{\chi }}}}}^{2}}_{{red}}\) of 0.084. The \(1\sigma\) envelopes overlap across all saturation levels, while the SD error bars range from ±1.6 to ±3.3 (Fig. 3b).

a, b regression fitting analysis using two functions (exponential and exponential with a constant c), where the mean flux decreases with the density-length increase. a The relationship between the measured mean hourly muon flux (\({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\)) and changing acrylic length. b The relationship between the measured mean hourly muon flux (\({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\)) and changing fluid saturation changing sand. The error bars represent 1σ (blue) and the SD of the three measurements per object, showing the statistical spread of the data. c, d The cumulative muon flux difference over time for varying material thickness and saturation levels was obtained from the measured results. c Cumulative flux difference for varying acrylic thicknesses (20−80 cm) to background (empty) measurements and the obtained change in muon flux as a function of time. d Cumulative flux difference for different sand saturation levels to dry (0%) measurements, ranging from partially saturated (25%) to fully saturated (100%). The dashed lines represent linear trends, while solid lines depict recorded measurements, showing a strong correlation between material properties and the number of muons attenuated as a function of density length. The slopes (Φλ) in (c, d) correspond to attenuation rates and correlate with the attenuation fits shown in (a, b). Thus, steeper slopes correspond to greater opacity (density–length) values and higher cumulative loss of flux, providing a temporal configuration to the attenuation trends.

The cumulative difference (attenuation rate) is a time-integrated approach that highlights the total change in the muon flux difference between two conditions (e.g., between dry and partially saturated sands), accumulated over time (Fig. 3c and d). The linear fits were constrained to pass through the origin point (D (0) = 0), consistent with the physical requirement that no deficit exists at the initial measurement time. The slope parameter (Φλ) represents the rate of cumulative muon deficit relative to the reference condition (background for acrylic, dry for sand). This slope provides a time-integrated measure of attenuation that scales with the density–length of the target, thereby linking the linear trends in the cumulative plots to the exponential attenuation coefficients obtained in Fig. 3a–b. The linear regression curves show the impact of thickness and density variability over time. Relative to the empty background, acrylic cubes produce linear deficits with slopes increasing systematically with thickness: 14.31, 16.41, 20.83, and 24.12 muons for 20, 40, 60, and 80 cm acrylic thickness, respectively (Fig. 3c). Similarly, the cumulative difference relative to fully dry sand cubes increases with saturation: 0.86, 3.23, 4.37, and 5.74 muons for ~25%, ~50%, ~75%, and ~100%, respectively (Fig. 3d). Both cumulative muon flux differences from acrylic and sand samples show significant deviations from a linear model, especially for sand samples.

Table 1 reports the estimated densities using laboratory Gaussian pulse-filtered data for acrylic cubes and variably saturated sand samples, using exponential and exponential with constant models. For homogeneous acrylic cubes, density estimations improve with length, from 20 to 80 cm, across all models. The approach used to convert measured flux attenuation into bulk density estimates is described in detail in the methodology section. The exponential with constant model shows the highest accuracy, with relative errors decreasing from 11.1% at 20 cm to 0.34% at 80 cm, outperforming exponential models. For variably saturated sands, the exponential with constant model consistently yields lower relative errors, which are closest to the known densities. Relative errors range from 21% for dry sands (0% saturation) to 10.8% at full saturation (100%), indicating improved accuracy with increasing saturation and density-length. In comparison and exponential models have higher relative errors, generally 20% to 25% across the saturation spectrum, with similar performance.

Numerical simulations

Numerical simulations show the expected monotonic attenuation of cosmic ray muons as the density length increases (Fig. 4). For homogeneous acrylic boxes (Fig. 4a and c), the mean hourly \({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) decreases from 151.1 muons for the empty configuration, to 147.12 muons at 20 cm, 143.52 muons at 40 cm, 140.43 muons at 60 cm, and 137.71 muons at 80 cm. An exponential model gives R2 = 0.996 and \({{{{{\rm{\chi }}}}}^{2}}_{{red}}\) = 0.2901. An exponential model with a constant improves the fit to R2 = 0.999 and \({{{{{\rm{\chi }}}}}^{2}}_{{red}}\) = 0.094. The 1σ uncertainties contract to around ±1.02, with error bars remaining separate across the thickness range, indicating that, under the chosen integration time, the statistical uncertainty is negligible compared to the systematic variation of detected muons with density length or saturation (Fig. 4a). SD error bars show small deviations from the mean due to the simulation nature. The cumulative difference relative to the empty configuration increases linearly over 144 h (Fig. 4c). Slopes increase with thickness: 9.97 muons for 80 cm, 7.6 muons for 60 cm, 6.12 muons for 40 cm, and 4.01 muons for 20 cm, showing that thicker acrylic removes a larger fraction of the muon flux hourly.

a, b regression fitting analysis using two functions (exponential and exponential with a constant c), where the mean flux decreases with the density-length increase. a The relationship between the measured mean hourly muon flux (\({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\)) and changing acrylic length. b The relationship between the measured mean hourly muon flux (\({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\)) and changing fluid saturation changing sand. The error bars represent 1σ (blue) and the SD of the three measurements per object, showing the statistical spread of the data. c, d The cumulative muon flux difference over time for varying material thickness and saturation levels was obtained from the measured results. c Cumulative flux difference for varying acrylic thicknesses (20−80 cm) to background (empty) measurements and the obtained change in muon flux as a function of time. d Cumulative flux difference for different sand saturation levels to dry (0%) measurements, ranging from partially saturated (25%) to fully saturated (100%). The dashed lines represent linear trends, while solid lines depict recorded measurements, showing a strong correlation between material properties and the number of muons attenuated as a function of density length. The linear slopes (Φλ) in (c, d) correspond to attenuation rates and correlate with the attenuation fits shown in (a, b). Thus, steeper slopes correspond to greater opacity (density–length) values and higher cumulative loss of flux, providing a temporal configuration to the attenuation trends.

Similar to the acrylic simulations, \({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) decreases as the fluid saturation degree of sands increases (Fig. 4b, d). The mean hourly flux \({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) ranges from 138.36 muons at ~0% saturation (four dry cubes), to 137.24 muons at ~25%, 135.83 muons at ~50%, 134.45 muons at ~75%, and 133.65 muons at ~100% saturation (four saturated cubes). The exponential model yields R2 = 0.993 and \({{{{{\rm{\chi }}}}}^{2}}_{{red}}\) = 0.03. An exponential model with a constant improves the fitting to R2 = 0.995 and \({{{{{\rm{\chi }}}}}^{2}}_{{red}}\) = 0.01. \(1\sigma\) uncertainties overlap with different experiments due to the experiment’s scale, which examines small density changes ( ~ 0.1 g cm-3). This indicates that, under the chosen integration time, the error bars reflect sensitivity to density variations at the ~1σ level. This implies that while flux reductions track increasing saturation, the density values are statistically compatible within one standard deviation, limiting the level of confidence at which distinct saturation states can be resolved. Longer integration times would reduce the relative uncertainty, improving discrimination, but at the cost of temporal resolution. In this work, the density estimates are therefore reported at the 1σ confidence level, which defines the sensitivity bounds of the experiment. Averaging across repeated measurements reduces variance, with SD ranging from 1.01 to 0.61. Integrated cumulative flux differences relative to dry sand cubes accumulate linearly (Fig. 4d). Slopes increase with saturation: 1.33 (~25%), 2.08 (~50%), 3.57 (~75%), and 5.17 (~100%) muons, demonstrating sensitivity to bulk density increments as small as ~0.11 g cm-³.

Simulation results show a direct reduction in \({\Phi }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) with increased length and changes in pore space fluid, correlating with experimental results. Both cumulative muon flux differences from acrylic and sand samples show minimal deviations from a linear model, indicating a steady increase. Figure 4a, b validates the exponential absorption framework for both homogeneous and porous media, confirming that cumulative deficits provide a time progression metric proportional to density length variations. The simulated data exhibit reduced stochastic variability, resulting in more robust empirical models with higher goodness-of-fit metrics due to the controlled simulation environment, which limits noise.

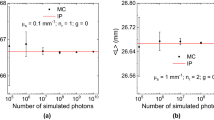

Table 2 illustrates density estimation outcomes from simulations for acrylic cubes and variably saturated sand samples, comparing exponential and exponential with constant models. The simulation results show low errors in known densities across all models. The exponential with constant model performs best, with relative errors of less than 1% for acrylic cubes across all thicknesses. The exponential model has higher relative errors, decreasing from around 11.2% and 5% at 20 cm to 3.45% and 2.83% at higher thicknesses. For simulated sand samples with varying saturations, the exponential with constant model significantly outperforms others, with relative errors dropping from 12.86% at 0% saturation to 0.29% at 100% saturation. The exponential model exhibits higher relative errors, ranging from 9% to 14%, which improve as saturation increases. Overall, density estimates from simulations show reduced errors with increased acrylic thickness and sand saturation.

Discussion

Density estimation remains one of the most persistent challenges in geophysics, particularly when addressing variations in pore space content and fluid saturation. These parameters directly influence bulk density but are difficult to resolve accurately using conventional geophysical techniques due to the density’s indirect relationship to most geophysical methods75,76, limitations in sensitivity to fluids77,78,79, and spatial and vertical resolutions55,56,80. The ability to detect and quantify such variations non-invasively is essential for reliable subsurface characterization applications.

This study validates the effectiveness of muography, an inherently non-invasive technique, for estimating density and saturation variations in porous media through controlled laboratory experiments and numerical simulations. Both data sets show a monotonic decrease in muon flux with increasing acrylic length and pore space fluid (density-length), confirming theoretical expectations15,81. A data-driven Gaussian pulse-height window isolates the muon peak and suppresses noise, with the results insensitive to modest changes of this window82,83,84. In this study, a 60-minute integration window was selected as an optimal compromise between temporal resolution and statistical stability. This interval effectively reduces stochastic noise associated with muon counting, which follows Poisson statistics, while preserving sensitivity to hourly-scale flux variations. Shorter integration times amplify statistical fluctuations, whereas longer durations can obscure transient or stage-specific flux trends85,86. The dominant sources of measurement uncertainty arise from the inherent Poisson distribution of muon arrivals and instrumental variability in detector response, as quantified by the standard deviation across repeated measurements of each object. The experimental setup’s limitations include muon path irregularities and scattering interactions, which affect precision7,18,87. Environmental factors (temperature and pressure) have a minimal impact on the muon flux88, but should be reassessed in prolonged experiments. Extending measurement durations improves the signal-to-noise ratio, making it a critical strategy for real-world applications. Although the experiment was designed to suppress most of the noise, residual external noise influenced the hourly flux. The noise sources included atmospheric pressure and temperature variability, electric signal noise, and accidental coincidences within the trigger window. We mitigated these through a fourfold coincidence trigger with a short gate, a Lead plate placed between Channels 1 and 2, light-tight housings, Gaussian pulse-height filtering to reject non-muon events, with a 60-minute integration window to reduce counting variance. Most unwanted arrivals were removed by the filtering process; however, atmospheric modulations remained unremoved, leading to noise contributions over the short experiment period, which limited the alignment and accuracy of trends across stages (Supplementary Figs. 1–2). Accurate material density estimation relies on precisely characterizing and fitting muon flux attenuation as a function of density-length. This relationship is crucial for understanding muon absorption in varying media and estimating density. The exponential with constant model outperforms others by accurately accounting for residual background, muon path deviations, material density errors, and scattered muon flux (Figs. 3a, d and 4a, d). Exponential models oversimplify the process by not considering the geometrical, environmental, and scattering effects. The exponential with constant model more accurately represents real-world conditions, yielding higher accuracy and a better fit. The minor performance enhancement in simulations compared to experiments is due to the controlled simulation environment, which lacks external noise and variability.

For homogeneous acrylic samples, simulation and experimental attenuation patterns align closely, except for the background measurement, which deviates from the exponential trend (Fig. 2a). This confirms that both datasets accurately capture the relationship between material thickness and muon flux reduction. The background anomaly is enhanced but not fully removed after filtering (Fig. 3a), likely due to overlapping noises. The exponential trend persists with increasing acrylic length (Figs. 3a, 4a). Simulation data show lower density estimation errors (less than 1%) compared to experimental scenarios (10–1%) due to controlled conditions that reduce detector noise and muon path variability. Increasing the density length improves density estimation, consistent with Matsushima et al.50. Overall, the exponential with constant model excels in accurately estimating densities, especially for higher thicknesses and saturation levels. These results demonstrate the model’s performance in describing attenuation in laboratory conditions for raw and filtered muon flux data, highlighting sensitivity to small bulk density changes and establishing empirical relationships for converting flux deficits into density estimates.

In porous sand scenarios, the reduction in muon flux with increasing fluid saturation is due to the replacement of low-density air with higher-density water in pore spaces (Figs. 3b, 4b). This increases bulk density, similar to the acrylic experiment, enhancing density estimation at high-density lengths. Experimental measurements showed relative errors of approximately 10.84% at full saturation using an exponential model with a constant, compared to 25% for an exponential model, highlighting limitations such as muography resolution and variations in sand pore space density. Simulations showed much lower relative errors (0.29% at full saturation). These observations underscore muography’s sensitivity to density changes as small as ≈ 0.1 g cm-³ and its ability to measure attenuation processes with reduced noise. Longer measurement times improve accuracy, making it crucial to account for environmental variables and extend measurement durations to obtain more accurate density estimates. The cumulative flux difference analysis validated the method’s effectiveness (Figs. 3c, d, 4c, d). The slopes (attenuation rate) values (Φλ) represent the physical attenuation rates associated with each experimental stage. These slopes illustrate changes in muon counts relative to a baseline over time. The correlation between Φλ and regression slopes demonstrates consistency, with longer acrylic lengths or higher sand saturation yielding systematically steeper slopes. The deviations from linearity observed in the cumulative muon flux deficit (Fig. 3c, d) are most pronounced in the sand experiments. Two main factors account for this behavior. First, the experimental scale and environmental drift exert a stronger influence in the porous media tests. In the acrylic series, stepwise increases in opacity (by doubling, tripling, or quadrupling thickness) yield large flux reductions that effectively suppress barometric noises. By contrast, the sand experiments involve only minor opacity increments linked to pore-space fluid content, rendering them far more sensitive to residual environmental fluctuations. Second, scattering and path-length heterogeneity within the detector’s acceptance introduce additional variability. Since muons do not propagate strictly vertically, oblique trajectories extend the effective travel distance through the medium. Collectively, these results highlight the scale dependence of muography measurements and the inherent vulnerability of small-opacity changes in granular systems to environmental and geometric noise. Both experimental and simulated datasets demonstrated that cumulative muon attenuation increased systematically with acrylic thickness and sand saturation, providing a time-integrated metric that reflects the attenuation path length. Linear trends fitted to the cumulative deficit curves confirm that muon attenuation can serve as a reliable proxy for bulk density over prolonged measurement periods. Experimental data exhibited greater fluctuation around the linear model compared to simulation data, primarily due to fluctuations in the noise-to-signal ratio and variations in environmental parameters. This effect is more pronounced in the experimental sand experiment due to its sensitivity to minor changes in fluid distribution within the pore space and external environmental noise. By integrating over time, the cumulative flux metric smooths random noise and amplifies the signal associated with material attenuation, providing a stable basis for long-term monitoring.

The results of this study demonstrate that absorption muography can provide a sensitive and non-invasive method for monitoring subtle changes in pore space bulk density and, indirectly, saturation in porous media. While the current investigation is conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, the implications extend well beyond small-scale testing. By resolving density variations associated with fluid saturation in porous sand, the methodology establishes a foundation for applying muography to a range of real-world geoscientific challenges. This includes reservoir monitoring, where detecting temporal changes in fluid content is critical for assessing production performance and enhanced recovery strategies. Similarly, fluid migration studies, such as leakage detection from CO₂ or hydrogen storage sites, can benefit from muography’s ability to identify minor density anomalies over time89,90,91,92. Muography offers continuous, passive monitoring of density redistribution capability not afforded by conventional geophysical methods. Thus, this work not only validates a methodological framework for using muography in laboratory-controlled porous media but also provides a scalable model for addressing key challenges in geophysical monitoring and exploration, environmental geoscience, and geoengineering. Future developments may include field-scale adaptation of this approach.

Conclusions

This study establishes a validated muography-based approach for estimating bulk density and identifying saturation levels in porous media. We demonstrate that muon attenuation reliably reflects changes in density length associated with changes in fluid content within the pore space, consistent with the exponential absorption model. Simulations exhibit lower uncertainties compared to experimental data, as they are conducted under controlled conditions, thereby eliminating external variables such as detector noise and environmental fluctuations. The exponential with constant fitting approach delivers the highest accuracy, with errors below 1% in simulations and within ~10% in experimental conditions. Our findings confirm muography’s sensitivity to detect small density changes ( < 0.1 g cm-³) and highlight its potential for non-invasive, high-resolution monitoring of porous systems. This study provides a critical step toward scaling muography for field-scale applications in reservoir monitoring and subsurface applications. Future studies should focus on mitigating environmental fluctuations, optimizing detector response, and isolating the attenuation signal to refine density estimations. This can be achieved by employing simultaneous dual-detector configurations for differential muography, where one detector stack views the target and a co-located reference stack records the background signal. The synchronized ratio of fluxes suppresses common-mode environmental and instrumental variations, isolating the true attenuation signal. Furthermore, incorporating directional muon tracking will allow reconstruction of angular-dependent flux variations, providing the basis for 2D cross-sectional or even 3D tomographic images.

Methodology

Attenuation muography

We employ a muon absorption-based technique to estimate material density by analyzing the attenuation of cosmic-ray muons. As muons traverse matter, their flux diminishes through interactions with atomic electrons. This energy loss depends exponentially on the density-length product (\(\rho \cdot x\)), forming the basis for muon absorption-based density estimation. The intensity of transmitted muons through a medium follows the Beer-Lambert law93:

where \(I\) is the measured muon flux after attenuation, \({I}_{0}\) is the background (empty) flux without obstruction, \(\mu\) is the attenuation coefficient, and \(x\) is the material thickness. The attenuation coefficient12 \(\mu\) (m−1) is expressed as:

where \({\mu }_{m}\) is the mass attenuation coefficient (m2 g-1) and \(\rho\) is the bulk density of the material (g cm-3). This assumes muons travel in straight trajectories with negligible multiple scattering, an approximation valid for high-energy muons and for both vertical and non-vertical incidence angles, knowing that the traversed object has a limited linear density.

Laboratory experiment materials

The muography experiment used a vertically aligned coincidence detection system to measure muon flux variations across materials with different densities and fluid saturation levels. The Cosmic-ray detection system consists of four 2 cm thick plastic scintillator units (Channels 1–4), each optically coupled to a photomultiplier tube (PMT) via an acrylic light guide (Fig. 5a). Each scintillator has a square geometry with a side length of 20 cm and a surface detection area of 400 cm2. These detectors are arranged in two pairs, stacked vertically. The vertical spacing is 17 cm between the upper detectors (Channels 1 and 2) and 13 cm between the lower detectors (Channels 3 and 4), resulting in a total detector height of 166 cm. A 3 cm thick lead plate placed between Channels 1 and 2 to suppress background noise by attenuating the majority of unwanted events, such as electrons and gamma rays particles, which attenuate much more rapidly than muons (Fig. 5a). Target materials are placed between Channels 2 and 3 (136 cm spaced), ensuring interaction with all recorded events (Fig. 5).

a Schematic diagram of the muon detection system for coincidence analysis. b A single acrylic cube (20 cm). c three acrylic cubes (60 cm). d Four dry sand cubes representing 0% fluid saturation. e A combination of two fully dry and two fully saturated sand cubes corresponds to 50% fluid saturation. f Four fully saturated sand cubes (100% fluid saturation) illustrate the detection of coinciding muon events (red dashed lines) traversing the medium. The setup enables precise measurement of muon flux variations across different material lengths and compositions while ensuring that only coincident events passing through the medium are recorded for analysis.

Signals from each PMT are converted to digital outputs and monitored for simultaneous hits. An event is registered if all four detectors are triggered within a predefined time window, confirming a muon has passed through the detector stack and the test material. This configuration captures only muons that are almost vertically aligned, minimizing contributions from oblique trajectories. To avoid bias in the measurements, all geometrical and electronic parameters remained the same throughout all measurements. The measurement setup used the same fourfold-coincidence scintillator detectors with identical spacing, PMT high-voltage (HV) bias settings, and acquisition thresholds. Detector efficiency was verified to remain constant across repeated runs and over the duration of the experiments.

Muon flux measurements were conducted over 48-hour intervals for each experimental stage and target configuration. To ensure statistical robustness, each setup was replicated three times, resulting in a cumulative acquisition period of 144 h per configuration. Measurements included an empty background and various target configurations to evaluate muon flux attenuation across different material thicknesses and saturation states. Acrylic boxes of 20 cm height were stacked to total thicknesses of 20 cm, 40 cm, 60 cm, and 80 cm (Fig. 5b, c).

Sand experiments assessed muography sensitivity to changes in bulk density due to fluid content. Four sand cubes (19.5 cm × 19.5 cm × 19.2 cm) were arranged with varying proportions of dry and saturated conditions to simulate different saturation levels: 0% (all dry), ~25%, ~50%, ~75%, and ~100% (all saturated) (Fig. 5d, f). Homogeneous Toyoura sand samples94 were used, with careful preparation to ensure consistent packing and minimal trapped air. The water was added incrementally, cube by cube, from the bottom upward. Although the distribution of dry and saturated cubes is stratified in this design, the principle of muography is based on the integrated density-length along the muon path. Thus, the measured transmission depends only on the column’s mean bulk density, not on the vertical order of dry and saturated layers. The chosen bottom-to-top filling replicates the typical reservoir scenario in which buoyancy drives gas to the top of the pore column, while also allowing systematic division into ~25% steps of saturation for testing muography’s sensitivity to small increments in bulk density. Porosity and bulk density of the sand samples were determined experimentally. The porosity was calculated as the ratio of pore volume to total volume, yielding 43.74%. Bulk density was 1.28 g cm-³ for dry sand and 1.723 g cm-³ for saturated sand. Densities at ~25%, ~50%, and ~75% saturation were 1.391, 1.5, and 1.612 g cm-³, respectively. These parameters were used to evaluate muon attenuation as a function of sand saturation and as input for simulations.

Numerical simulations

We employed Monte Carlo simulations using the PHITS (Particle and Heavy Ion Transport System) software to replicate the laboratory setup and validate our experimental results. A detailed 3-D model was constructed, mimicking the experimental geometry from the concrete roof to the laboratory floor (Fig. 6a). The simulation geometry precisely matched the vertical arrangement of scintillator detectors, lead bars, and target objects (Fig. 6b, c). or consistency and simplification in the simulation environment, both acrylic and sand targets were modeled with fixed dimensions of 20 cm × 20 cm × 20 cm, slightly larger than the experimental sand objects. Material densities and compositions were derived from experimental values (Fig. 6).

a Conceptual illustration of the experimental setup, where muons originating from a hemisphere source traverse a changing target object before being detected across the detector array. Dashed red lines are coinciding events, while brown dashed lines are unrecorded events. b Simulation model of homogeneous acrylic boxes configurations, demonstrating increasing material thickness. c Simulation model of porous sand cubes configuration, showing variations in saturation levels: 0% saturation (dry sand), ~50% saturation (partially saturated sand), and ~100% saturation (fully saturated sand). The figures are not to scale; however, all simulation components strictly conform to the laboratory’s positional and geometric specifications.

Cosmic-ray muons were modeled using a hemisphere source emitting muons with energies from 10-4 to 10 GeV. The emitted muon flux was adjusted to match the experiment period, assuming a uniform incident flux of 1 muon·cm−2·min−195,96. Energy and angular distributions were generated using the PHITS-based Analytical Radiation Model in the Atmosphere (PARMA)97,98, accurately characterizing the secondary cosmic-ray muon spectrum, including altitude variations.

Two simulation series were conducted: one with empty (background) and homogeneous acrylic cubes, incrementally increasing material thickness (Fig. 6b), and another with porous media (sand), modeling different fluid saturation scenarios (Fig. 6c). Simulated detector responses captured coinciding muon events traversing vertically through the target objects, excluding deviating trajectories, thus reproducing the experimental detection criteria.

Data analysis

Filtering of the laboratory data

The obtained Pulse-height spectra are MCA histograms in ADC channels (Fig. 7). To isolate the muon peak from background noise (electronic fluctuations and secondary cosmic-ray particles), we used a dynamic filter range for each channel. This range was determined using a Gaussian function:

Where, a is the amplitude, μ is the mean (center of the muon peak), and σ is the standard deviation (width of the peak). We apply a symmetric window centered on the modal region of the muon peak as an operational selector to remove the pedestal and accidentals. We do not assume a Gaussian peak shape or a 95 % capture fraction of the muon signal. This dynamic window filter effectively reduces noise while preserving the muon signal (Fig. 7). The raw amplitude spectra were fitted with Gaussian models to locate the central peak. The acceptance window was defined as μ ± 2σ for each channel, with thresholds applied to ensure accuracy. The resulting pulse height bounds were used to create band-pass filtered datasets, ensuring only valid muon events were retained for further analysis. Furthermore, we validated that varying the dynamic window within reasonable bounds does not change the reported flux deficits within their uncertainties. Moreover, the choice of a Gaussian filter was made after experimenting with different filtering techniques (Supplementary Fig. 3) to utilize the most efficient approach, one that adapts to the dataset’s characteristics.

Shown are PMT pulse amplitudes from each detector channel for events passing the fourfold coincidence condition; these represent signal amplitudes rather than deposited energy. The figure shows the counts of detected events for each amplitude signal (pulse height). A Gaussian fit (red curve) is applied to estimate the central muon peak, with upper and lower bounds (μ ± 2σ) indicated by vertical dashed lines. The estimated minimum and maximum pulse height ranges are specified for each channel filtering, corresponding to the valid signal window.

The raw muon flux measurements and filtered fluxes from all four channels were first evaluated individually and then aggregated to form a composite flux signal (Φ), which was averaged across all channels. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4a, filtered fluxes demonstrated consistent trends across all channels, indicating successful noise suppression. The averaged muon flux was computed as a function of the integration time window (15–120 min) to evaluate statistical convergence and minimize temporal fluctuations (Supplementary Fig. 4b). A 60-minute integration window was selected as the optimal temporal resolution for all measurement configurations, balancing statistical noise reduction and temporal fidelity.

Muon flux measurements contain high-frequency noise due to atmospheric cosmic-ray interactions99, and shorter intervals (15 or 30 min) amplify uncertainties due to lower event counts, resulting in higher SD and reduced statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Increasing the integration time improves statistical precision by increasing muon counts, reducing relative uncertainty in flux measurements. The 60-minute window offers significantly lower error amplitudes compared to 90- and 120-minute intervals, indicating reduced statistical noise, while preserving sufficient temporal granularity to resolve diurnal muon flux fluctuations, which typically evolve on hourly timescales. Although 15- and 30-minute windows further suppress noise, they also smooth out short-term flux variations and reduce the number of data points available for resolving attenuation trends (Supplementary Fig. 4b). The 60-minute interval ensures statistical convergence while maintaining the temporal responsiveness necessary for atmospheric correction and density-dependent attenuation analysis.

Environmental corrections

Muon counts were investigated to remove environmental variations100, including barometric and temperature effects, thereby isolating attenuation due to material density. Ground temperature and atmospheric pressure data were collected from Shimoufusa Ab station, Nagayama, via the Meteostat database101 for each experiment’s duration. Environmental dependencies were quantified by correlating normalized flux variations with deviations from baseline temperatures (20 °C) and pressures (1013.2 hPa) (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Linear regression yielded correction coefficients of 0.0006 °C⁻¹ for temperature and −0.002 hPa⁻¹ for pressure (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). However, the muon data showed significant scatter and no meaningful correlation with temperature or pressure (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Given the lack of correlation and low system sensitivity within the observed range, these correction factors were not applied in this analysis.

Muon flux averaging and uncertainty of the measurements

The final hourly muon flux counts, averaged across all detectors and repetitions, are subject to statistical uncertainty governed by the Poisson distribution. The SD (σ) of the number of counts (N) is given by:

Uncertainties in muon flux measurements are reported using SD-based confidence intervals. A 1σ interval corresponds to a 68.27% confidence level, indicating the true value lies within one standard deviation of the mean about 68% of the time. The counting rate (R) is the number of counts (N) divided by the measurement time (T):

The uncertainty in the counting rate \({\sigma }_{R}\) is derived from the uncertainty in the total counts:

For multiple detector channels, the combined uncertainty in the total muon count (S = A + B +…) is given by:

where A, B, etc., represent the total muon counts recorded by each detector channel, and \({\sigma }_{A}\), \({\sigma }_{B}\), etc., are their corresponding standard deviations. This assumes statistical independence between channels. When averaging over multiple detectors, the uncertainty in the mean count is reduced as:

This framework accounts for both random fluctuations and systematic contributions in estimating density-dependent muon attenuation parameters. To propagate uncertainties from \({{{{\rm{I}}}}}_{0}\) and \({{{{\rm{I}}}}}_{{{{\rm{x}}}}}\) into \(\mu\), we apply standard error propagation rules. The relative uncertainty in the \(\frac{{{{{\rm{I}}}}}_{{{{\rm{x}}}}}}{{{{{\rm{I}}}}}_{0}}\) is described as:

Empirical fitting and attenuation model

To estimate the muography attenuation model in laboratory conditions and quantify muon flux sensitivity to material density length, we calibrated the model using acrylic cubes of known density and thickness, then applied it to estimate the bulk density of both acrylic and sand cubes. We tested two empirical fitting models: (1) an exponential decay model of the form \(y(x)=a\cdot {e}^{{bx}}\), (2) an exponential model with a constant in form \(y\left(x\right)=a\cdot {e}^{{bx}}+c\).

Fitting for the exponential models was performed using nonlinear least squares optimization, with coefficients a, b, and c determined by minimizing the residual sum of squares between observed and predicted muon counts. In all models, the independent variable x represents the density-length product (\(\rho \cdot x\)), and the dependent variable y(x) corresponds to the measured muon flux (muons per hour). The exponent coefficient b in the exponential models is related to the attenuation coefficient μ, with a more negative b implying stronger attenuation. The constant c in the shifted exponential model accounts for a non-zero flux baseline due to scattered muons, muon path deviations, or electronic background. The estimated attenuation model serves as a basis to estimate material densities; we used an indirect inversion approach based on exponential muon attenuation. For acrylic, the known parameters include cube thicknesses, measured muon count rates, and total measurement duration. Using an assumed bulk density (1.19 g cm-³), we computed corresponding density lengths (ρ·x) and fitted these against the measured muon fluxes using the absorption model. Then, we inverted the model to estimate the density length for each measurement and retrieved the acrylic density by dividing the inferred density length by the known physical thickness. Once validated on the homogeneous acrylic samples, the fitted model was applied to estimate the bulk densities of variably saturated sand cubes (Fig. 1). In this case, the same attenuation parameters were used, and the measured muon fluxes for each saturation level were input into the model to calculate corresponding density lengths. These were then divided by the known total thickness of the sand column to retrieve the effective bulk density under each saturation condition.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The muography experimental and simulation data used in the present work are made available at [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15542006].

References

Atri, D. & Melott, A. L. Cosmic rays and terrestrial life: a brief review. Astropart. Phys. 53, 186–190 (2014).

Tanaka, H. K. et al. Muography. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 3, 88 (2023).

Tanaka, H. K. Subsurface density mapping of the earth with cosmic ray muons. Nucl. Phys. B Proc. Suppl. 243, 239–248 (2013).

Kenyon, I. R. Elementary particle physics. (Springer Science & Business Media, 1987).

Measday, D. F. The nuclear physics of muon capture. Phys. Rep. 354, 243–409 (2001).

Rhodes, C. J. Muon tomography: looking inside dangerous places. Sci. Prog. 98, 291–299 (2015).

Drees, J. & Montgomery, H. Muon scattering. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 33, 383–452 (1983).

Gaisser, T. K., Engel, R. & Resconi, E. Cosmic rays and particle physics. (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Procureur, S. Muon imaging: Principles, technologies and applications. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 878, 169–179 (2018).

Scheck, F. Muon physics. Phys. Rep. 44, 187–248 (1978).

Yang, G. et al. Novel muon imaging techniques. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180062 (2019).

Lechmann, A. et al. The effect of rock composition on muon tomography measurements. Solid Earth 9, 1517–1533 (2018).

Eleslambouly, A. et al. (International Exchange and Innovation Conference on Engineering & Sciences).

Kaiser, R. Muography: overview and future directions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180049 (2019).

Cheng, Y.-P. et al. Imaging internal density structure of the Laoheishan volcanic cone with cosmic ray muon radiography. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 88 (2022).

Anghel, V. et al. A plastic scintillator-based muon tomography system with an integrated muon spectrometer. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers, Detect. Assoc. Equip. 798, 12–23 (2015).

Priedhorsky, W. C. et al. Detection of high-Z objects using multiple scattering of cosmic ray muons. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74, 4294–4297 (2003).

Vanini, S. et al. Muography of different structures using muon scattering and absorption algorithms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180051 (2019).

George, E. Cosmic rays measure overburden of tunnel. Commonwealth Eng. 455 (1955).

Auger, P. Rayons cosmiques (Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 1941).

Leprince-Ringuet, L. Les rayons cosmiques: les mésons (Albin Michel, Paris, 1948).

Gaisser, T. K. Cosmic Rays and Particle Physics (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1990).

Crozon, M. Quand le ciel nous bombarde: qu’est-ce que les rayons cosmiques? (Vuibert, Paris, 2005).

Neddermeyer, S. H. & Anderson, C. D. Note on the nature of cosmic-ray particles. Phys. Rev. 51, 884 (1937).

Neddermeyer, S. H. & Anderson, C. D. Cosmic-ray particles of intermediate mass. Phys. Rev. 54, 88 (1938).

Alvarez, L. W. et al. Search for hidden chambers in the pyramids: the structure of the second pyramid of Giza is determined by cosmic-ray absorption. Science 167, 832–839 (1970).

Tanaka, H. K., Uchida, T., Tanaka, M., Shinohara, H. & Taira, H. Cosmic-ray muon imaging of magma in a conduit: Degassing process of Satsuma-Iwojima Volcano, Japan. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36 (2009).

Nagamine, K., Iwasaki, M., Shimomura, K. & Ishida, K. Method of probing inner-structure of geophysical substance with the horizontal cosmic-ray muons and possible application to volcanic eruption prediction. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 356, 585–595 (1995).

Tanaka, H. K. et al. High resolution imaging in the inhomogeneous crust with cosmic-ray muon radiography: The density structure below the volcanic crater floor of Mt. Asama, Japan. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 263, 104–113 (2007).

Okubo, S. & Tanaka, H. Imaging the density profile of a volcano interior with cosmic-ray muon radiography combined with classical gravimetry. Meas. Sci. Technol. 23, 042001 (2012).

Ambrosino, F. et al. Joint measurement of the atmospheric muon flux through the Puy de Dôme volcano with plastic scintillators and Resistive Plate Chambers detectors. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 120, 7290–7307 (2015).

Liu, G. et al. Deep investigation of muography in discovering geological structures in mineral exploration: a case study of Zaozigou gold mine. Geophys. J. Int. 237, 588–603 (2024).

Teixeira, P. et al. in International Conference on Mediterranean Geosciences Union. 173-177 (Springer).

Schouten, D. Muon geotomography: selected case studies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180061 (2019).

Borselli, D. et al. Three-dimensional muon imaging of cavities inside the Temperino mine (Italy). Sci. Rep. 12, 22329 (2022).

Bonneville, A. et al. Borehole muography of subsurface reservoirs. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180060 (2019).

Saracino, G. et al. Applications of muon absorption radiography to the fields of archaeology and civil engineering. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180057 (2019).

Balázs, L. et al. 3-D muographic inversion in the exploration of cavities and low-density fractured zones. Geophys. J. Int. 236, 700–710 (2024).

Basset, M. et al. MGR: An innovative, low-cost and compact cosmic-ray detector. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers, Detect. Assoc. Equip. 567, 298–301 (2006).

Menichelli, M. et al. A scintillating fibres tracker detector for archaeological applications. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 572, 262–265 (2007).

Morishima, K. et al. Discovery of a big void in Khufu’s Pyramid by observation of cosmic-ray muons. Nature 552, 386–390 (2017).

Basiri, H., Kin, T., Okamoto, N., Giammanco, A. & Gil, E. C. Simulation of a First Case Study for Magnetic Field Imaging with the Magic-µ Technique. J. Adv. Instrum. Sci. (2022).

Miyadera, H. et al. Imaging Fukushima Daiichi reactors with muons. Aip Advances 3 (2013).

Jonkmans, G., Anghel, V., Jewett, C. & Thompson, M. Nuclear waste imaging and spent fuel verification by muon tomography. Ann. Nucl. Energy 53, 267–273 (2013).

Procureur, S. et al. 3D imaging of a nuclear reactor using muography measurements. Sci. Adv. 9, eabq8431 (2023).

Fujii, H. et al. Investigation of the Unit-1 nuclear reactor of Fukushima Daiichi by cosmic muon radiography. Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2020, 043C002 (2020).

Lefevre, B. et al. 3D Reconstruction of a Nuclear Reactor by Muon Tomography: Structure Validation and Anomaly Detection. PRX Energy 4, 013002 (2025).

Matsushima, J. et al. Combined measurement of cosmic ray muons and elastic waves on a laboratory scale: a follow-up report. Proc. SEGJ Conf. 148, 113–115 (2023).

Pang, J. et al. Accurate in situ rock density measurement with cosmic ray muon radiography. J. Appl. Phys. 135 (2024).

Matsushima, J. et al. Joint measurement of cosmic-ray muons and seismic waves at laboratory scale. Geophys. J. Int. 239, 1821–1832 (2024).

Lelièvre, P. G. et al. Joint inversion methods with relative density offset correction for muon tomography and gravity data, with application to volcano imaging. Geophys. J. Int. 218, 1685–1701 (2019).

Barnoud, A. et al. Bayesian joint muographic and gravimetric inversion applied to volcanoes. Geophys. J. Int. 218, 2179–2194 (2019).

Barnoud, A. et al. Robust Bayesian joint inversion of gravimetric and muographic data for the density imaging of the Puy de Dôme Volcano (France). Front. Earth Sci. 8, 575842 (2021).

Nishiyama, R. Joint inversion of muography and gravity data for 3D density imaging of volcanoes. Muography: Exploring Earth’s Subsurface with Elementary Particles, 33-42 (2022).

Eiken, O., Zumberge, M. & Sasagawa, G. in SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 2000 431-434 (Society of Exploration Geophysicists, 2000).

Zumberge, M., Alnes, H., Eiken, O., Sasagawa, G. & Stenvold, T. Precision of seafloor gravity and pressure measurements for reservoir monitoring. Geophysics 73, WA133–WA141 (2008).

Kolesov, V. & Gareev, K. in SPE Russian Petroleum Technology Conference. (OnePetro).

Jenkins, C., Chadwick, A. & Hovorka, S. D. The state of the art in monitoring and verification—ten years on. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 40, 312–349 (2015).

Avseth, P., Mukerji, T. & Mavko, G. Quantitative seismic interpretation: Applying rock physics tools to reduce interpretation risk. (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Pride, S. R. & Berryman, J. G. Linear dynamics of double-porosity dual-permeability materials. I. Governing equations and acoustic attenuation. Phys. Rev. E 68, 036603 (2003).

Mavko, G., Mukerji, T. & Dvorkin, J. The rock physics handbook. (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Takahashi, T. ISRM suggested methods for land geophysics in rock engineering. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 41, 885–914 (2004).

Forsberg, R. A study of terrain reductions, density anomalies and geophysical inversion methods in gravity field modelling. (Ohio State University. Division of Geodetic Science, 1984).

Gasperikova, E. & Hoversten, G. M. A feasibility study of nonseismic geophysical methods for monitoring geologic CO2 sequestration. Lead. Edge 25, 1282–1288 (2006).

Yilmaz, Ö. Seismic data analysis: Processing, inversion, and interpretation of seismic data. (Society of Exploration Geophysicists, 2001).

Batzle, M. & Wang, Z. Seismic properties of pore fluids. Geophysics 57, 1396–1408 (1992).

Tanaka, H. K. & Oláh, L. Overview of muographers. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180143 (2019).

Leone, G. et al. Muography as a new complementary tool in monitoring volcanic hazard: implications for early warning systems. Proc. R. Soc. A 477, 20210320 (2021).

Lesparre, N. et al. Geophysical muon imaging: feasibility and limits. Geophys. J. Int. 183, 1348–1361 (2010).

Flygare, J., Bonneville, A., Kouzes, R., Yamaoka, J. & Lintereur, A. Muon borehole detector design for use in 4-D density overburden monitoring. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 65, 2724–2731 (2018).

Kudryavtsev, V. A., Spooner, N. J., Gluyas, J., Fung, C. & Coleman, M. Monitoring subsurface CO2 emplacement and security of storage using muon tomography. Int. J. Greenh. gas. control 11, 21–24 (2012).

Zhong, J., Yi, J., Xie, Q. & Jiang, X. A feasibility study of using cosmic ray muons to monitor supercritical CO2 migration in geological formations. Energy Procedia 75, 2299–2304 (2015).

Klinger, J. et al. Simulation of muon radiography for monitoring CO2 stored in a geological reservoir. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 42, 644–654 (2015).

Jiang, X., Hassan, W. A. A. & Gluyas, J. Modelling and monitoring of geological carbon storage: A perspective on cross-validation. Appl. Energy 112, 784–792 (2013).

Li, K. et al. Non-invasive geophysical methods for monitoring the shallow aquifer based on time-lapse electrical resistivity tomography, magnetic resonance sounding, and spontaneous potential methods. Sci. Rep. 14, 7320 (2024).

Sentenac, P., Benes, V. & Keenan, H. Reservoir assessment using non-invasive geophysical techniques. Environ. Earth Sci. 77, 1–14 (2018).

Berryman, J. G., Berge, P. A. & Bonner, B. P. Estimating rock porosity and fluid saturation using only seismic velocities. Geophysics 67, 391–404 (2002).

Han, D. -h & Batzle, M. L. Gassmann’s equation and fluid-saturation effects on seismic velocities. Geophysics 69, 398–405 (2004).

Fawad, M., Hansen, J. A. & Mondol, N. H. Seismic-fluid detection-a review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 210, 103347 (2020).

Nabighian, M. N. et al. Historical development of the gravity method in exploration. Geophysics 70, 63ND–89ND (2005).

Zhang, J. et al. Muon Absorption Imaging for the Density Structure of Metro Tunnel Overburden. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment, 170307 (2025).

Albanese, R. et al. Measurement of the muon flux at the SND@ LHC experiment. Eur. Phys. J. C. 84, 90 (2024).

Benettoni, M. et al. Noise reduction in muon tomography for detecting high density objects. J. Instrum. 8, P12007 (2013).

Bravar, U. et al. Design and testing of a position-sensitive plastic scintillator detector for fast neutron imaging. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 53, 3894–3903 (2006).

Seo, J. et al. Real-time portable muography with Hankuk Atmospheric-muon Wide Landscaping: HAWL. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 225, 112117 (2024).

Tanaka, H. K. et al. First results of undersea muography with the Tokyo-Bay seafloor hyper-kilometric submarine deep detector. Sci. Rep. 11, 19485 (2021).

Sogarwal, H. & Shukla, P. Measurement of atmospheric muon angular distribution using a portable setup of liquid scintillator bars. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2022, 011 (2022).

Mubashir, A. et al. Muon flux variations measured by low-cost portable cosmic ray detectors and their correlation with space weather activity. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 128, e2023JA031943 (2023).

Thiyagarajan, S. R., Emadi, H., Hussain, A., Patange, P. & Watson, M. A comprehensive review of the mechanisms and efficiency of underground hydrogen storage. J. Energy Storage 51, 104490 (2022).

Gluyas, J. et al. Passive, continuous monitoring of carbon dioxide geostorage using muon tomography. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180059 (2019).

Bonneville, A. et al. A novel muon detector for borehole density tomography. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers, Detect. Assoc. Equip. 851, 108–117 (2017).

Winthaegen, P., Arts, R. & Schroot, B. Monitoring subsurface CO2 storage. Oil gas. Sci. Technol. 60, 573–582 (2005).

Knoll, G. F. Radiation detection and measurement. (John & Wiley Sons Inc, 2010).

Zhang, F., Jin, Y. & Ye, B. A try to give a unified description of Toyoura sand. Soils Found. 50, 679–693 (2010).

Olive, K. A. Review of particle physics. Chin. Phys. C. 38, 090001 (2014).

Ramesh, N., Hawron, M., Martin, C. & Bachri, A. Flux Variation of Cosmic Muons. J. Ark. Acad. Sci. 65, 1 (2011).

Sato, T. Analytical model for estimating the zenith angle dependence of terrestrial cosmic ray fluxes. PloS one 11, e0160390 (2016).

Sato, T. Analytical model for estimating terrestrial cosmic ray fluxes nearly anytime and anywhere in the world: extension of PARMA/EXPACS. PloS one 10, e0144679 (2015).

Taricco, C. et al. Exploration of the stratosphere with cosmic-ray muons detected underground. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 023226 (2022).

Berkova, M., Grigoryev, V., Preobrazhensky, M., Zverev, A. & Yanke, V. Temperature effect observed for the muon component in the Yakutsk cosmic-ray spectrograph. Phys. At. Nucl. 81, 776–785 (2018).

Meteostat. Nagareyama, Japan - Daily weather data. Meteostat. https://meteostat.net/en/place/jp/nagareyama. (Accessed 16 November 2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Khalifa University (Grant No. 8474000599), the Mohammed bin Salman Center for Future Science and Technology for Saudi Arabia–Japan Vision 2030 at the University of Tokyo (MbSC2030), and the Earthquake Research Institute of the University of Tokyo (ERI JURP Grant No. 2025-H-03). The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of Khalifa University’s high-performance computing and research computing facilities to the results of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.E. M.Y.A. and J.M. designed the study, conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, and led the initial manuscript preparation. A.E., H.B., M.K. and J.M. supervised the experimental setup and contributed to data interpretation and manuscript editing. A.E., M.Y.A. and F.B. generated the figures. M.Y.A. J.M. and F.B. provided scientific guidance, coordinated project activities, and supported data analysis and interpretation. A.E. and H.B. contributed to the development of the simulation framework. M.Y.A., J.M., H.B., F.B., M.K. and T.Y. validated the results and reviewed the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the final manuscript. M.Y.A. and J.M. obtained the funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Hector Gomez and Luigi Cimmino for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Gareth Roberts and Nandita Basu. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eleslambouly, A., Basiri, H., Ali, M.Y. et al. Laboratory-scale muography experiments to estimate density and saturation in porous media. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1038 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03010-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03010-9